(Ivan Tikhonovich) - a famous Russian economist, one of those self-taught teachers of Moscow church literature who, while firmly adhering to the old national principles, nevertheless clearly understood that Russia must move forward and that salvation lies only in the full development of its forces. Biographical information regarding Pososhkov is extremely scarce. He was born in the village. Pokrovsky, near Moscow, around 1670. In documents, his name appears for the first time in the case of the builder of St. Andrew's monastery, Avramiy, who gave Peter “notebooks” about the causes of discontent among the people. In this case, among “long-time friends and bread-eaters,” among others, the peasants “Ivashka and Romashka Pososhkovs” were brought to justice. This time Pososhkov managed to extricate himself from the case. Then Pososhkov leads an active life as a pioneer of the emerging Russian industry, and sometimes occupies an official position (in vodka affairs). He tries to make inventions in the military field, generally works a lot, writes, manages to become a relatively wealthy man, but does not acquire a prominent position among Peter’s employees and dies under Catherine I, February 1, 1726, in Peter and Paul Fortress. The reason for the arrest has not been precisely clarified, but, apparently, Pososhkov’s death was caused precisely by his writing: “Books about poverty and wealth, this is an expression of what causes poverty, and from what gobzo wealth multiplies” - an essay that forms the main basis of his glory.

In terms of the strength of the language, the mass of issues raised, and the richness of thought, this work gives every right to call Pososhkov the first Russian economist. Much of what Pososhkov spoke about was the issue of the day and was discussed in one way or another by other contemporaries of Peter; but to compile a whole treatise about it, and, moreover, in the absence of acquaintance with at least the rudiments of Western European economic science, a remarkable talent was required, the power of which becomes even more obvious when comparing Pososhkov’s book with the poor in thought and language works of the so-called mercantile theorists, especially German ones. Pososhkov’s essay is not of a narrowly economic nature. This is a whole program for the reconstruction of the Russian state, including such measures that have not been implemented to this day. Pososhkov represents an original combination of mercantile ideas with the canonical ideas of the West - a combination that is all the more curious because it was created outside of any literary Western European influences. Pososhkov is first of all a seeker of Christian truth, and then a nationalist, a supporter of democratic centralization on the basis of absolute monarchy. principle. His belief in absolutism is so great that he even finds it possible to mint money without being in accordance with the real value of the metal. He also dreams that the state is able to set a “natural, fair price,” and recommends that the issue be resolved very simply: “If anyone takes a price that is not truly excessive, he will be fined and given a whipping or whipping so that he will not do so in the future.” He is aware that the main source of wealth is land, but is inclined to attach great importance abundance of money.

He understands that satisfaction with fiscal goals alone cannot serve as the basis for a reasonable public policy and that only through the development of industry is the prosperity of the state possible. The government's concern should be directed to the development of national productive forces. Russia has many untouched natural resources; when we develop independent production of daily necessities, foreigners will be “more kind to us, they will put aside all their former pride and begin to chase us.” Ways to encourage domestic industry: tariff, organization of warehouse trading places, development of the guild system, attraction of foreign craftsmen to train Russians, development of literacy among the people, etc. Pososhkov insists on regulating the relations of landowners to peasants, justifying his opinion by the fact that “landowners are not centuries old for peasants.” The owners, for this reason, do not take great care of them, but their direct owner is the All-Russian Autocrat." He mourns the poor cultivation of the land, the destruction of forests, the harm of partitions, insists on the need for land surveying, rebels against the poll tax: “In mental terms,” he says, “there is no point in being, since the soul is an intangible thing and cannot be comprehended by the mind, and not having a price; it is necessary to value things that are grounded,” and, moreover, “to collect the treasury so as not to ruin the kingdom.” He is an opponent of the plurality of taxes: “Many fictitious people, although they have invented taxes to replenish land, capitation, homutey, bathhouse, cool, from water vessels, planted, pavement, bee, leather, mowing and from the tenths of the carts and call that collection petty fees: neither of those The treasury cannot be filled with convict fees, only the people have a great trumpet: a petty fee is small.” In his opinion, it is necessary to establish a single “state truthful tax, established since the Incarnation of Christ, that is, a tithe,” and a single duty should be established on goods, “for even the same skin is flayed from an ox.” Regarding salt, Pososhkov is of the opinion that “it is best for it to be in free trade.” In addition, Pososhkov owns the "Paternal Testament" - a house-building of the 17th century. and “The Mirror of the Schismatic’s Superstition,” which examines the causes of the schism. Pososhkov’s works were published by Pogodin (vol. 1st, M., 1842; 2nd, M., 1863), “Paternal Testament” - E. Prilezhaev (St. Petersburg, 1893).

Economics, Statistics and Computer Science

Ivan Tikhonovich Pososhkov and his legacy

Completed:

student of group DKI-13

Kashirov Anatoly

Checked:

Kucheruk Irina Vladimirovna

Pososhkov about wealth and money

Ivan Tikhonovich Pososhkov (1652-1726) - Russian economist and publicist - is the author of the essay “The Book of Poverty and Wealth,” written in 1721-1724. In this work, I. T. Pososhkov put forward a project for improving economic life Russia, the development of its productive forces.

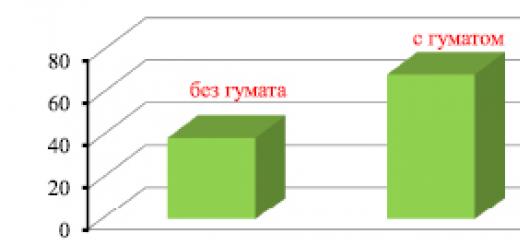

In contrast to the mercantile dogma, Pososhkov believed that the wealth of society is embodied not only in precious metals, but also in material goods. Pososhkov wrote: “It’s not that royal wealth, if there is a lot of treasury lying in the royal treasury, ... but that very royal wealth, if all the people, according to their own measures, were rich in their own inner wealth.” Pososhkov made a distinction between material wealth and immaterial wealth. He emphasized in every possible way the active role of immaterial wealth: the writer pointed out the direct connection between the production of material goods and the existing legal regime in Russia. “More than material wealth, we should all generally care about material wealth, that is, about true truth... Truth increases wealth and strength,... untruth not only makes one rich again, but also ancient wealth becomes thinner and leads to poverty.”

Pososhkov rose to the idea that the wealth of the state is unthinkable without the wealth of the people. “...In which kingdom people are rich, then the kingdom is rich, and in which kingdom there are poor people, then that kingdom cannot be considered rich.” Pososhkov emphasized that, in his opinion, “this is a small and very easy task, to fill the royal treasures with wealth... But that great and difficult task is to enrich the entire people.”

It is not without interest that Pososhkov anticipated the French physiocrats in his statement: “Peasant wealth is royal wealth, and peasant poverty is royal impoverishment.” Pososhkov’s statements about wealth, the identification of the country’s wealth with the people’s wealth, with peasant wealth, were of a progressive nature; they went beyond mercantilist ideas about wealth. Pososhkov’s views on money were also original. Defending an exceptional role state power in the development of Russia's productive forces, Pososhkov was a supporter of the nominalistic theory of money. Pososhkov wrote: “We are not foreigners, we do not calculate the price of copper, but we magnify the name of our king, for this reason, copper is not dear to us, but his royal name is dear, for this reason we do not count the weight in them, but we calculate the mark on it.”

Pososhkov's theory of money was, of course, wrong. He did not understand the function of the measure of value and the connection between money and goods. However, in the struggle for the economic independence of Russia, he defended his theory of money, protecting the Russian merchants from foreign competition. Pososhkov’s theory of money theoretically generalized financial practice his time.

Pososhkov about trade

Pososhkov strongly insisted on the need to provide patronage to the merchant class. The merchants, according to Pososhkov, constitute the essential basis of the state building. He believed that all members of society, all its constituent social groups, all classes needed merchants. Pososhkov especially emphasized the existence of interdependence between the merchants and the army.

Pososhkov expressed dissatisfaction with the fact that various strata of Russian society are widely drawn to trade, regardless of class. Trade, according to Pososhkov, should only be a privilege of representatives of the merchant class. Being a principled opponent of peasants trading, at the same time he considered it possible for representatives of the wealthy peasantry to join the merchant class.

Pososhkov advocated for the Russian merchants to monopolize all trade in the country. He believed that not only “foreign” people should be closed to the class of merchants, but that there should also be no access to “free trade” for foreign merchants. All this will have a very beneficial effect on the collection of duties. Pososhkov is a supporter of righteous, “holy” “bargaining,” without deception. In order to eliminate competition between merchants, Pososhkov speaks out for a price regulated from above, not a free price, but a specified, “established” price.

In matters of foreign trade with foreigners, to which Pososhkov attached great importance, he promoted the organization of the Russian merchants in the form of a single trading company - a “company”. Trade with foreigners must be organized and carried out with the permission of the merchant “commander”. With the permission of the “commander”, with the consent of the entire “company”, goods should be exported abroad at predetermined prices, like trading with visiting foreigners at fairs.

Pososhkov was a supporter of competition with foreign merchants at prices for goods set by Russian merchants. He was filled with confidence that in this competitive struggle, Russian merchants would emerge victorious, due to the great interest of foreigners in Russian goods. Pososhkov insisted on strict selection of goods imported into the country. In his opinion, such goods should be of excellent quality; the country should really need them. And in this matter the organizing, regulating role of the “company” should have an impact.

Pososhkov lists those goods that Rus' does not need, and “wouldn’t buy any of those things from foreigners at half price.” Attaching the issue of the import of foreign goods of great national economic importance, Pososhkov emphasized the importance of control over the import of goods. Among the measures that should limit the consumption of luxury goods and reduce the import of foreign goods, Pososhkov also dwells on the “clothing arrangement.” Each “rank” must be assigned appropriate clothing.

Pososhkov considered the designed “clothing arrangement” as a “great” matter. “The first is that the rank from rank will be clear and everyone will know their own measure, the second is that every rank will not have excessive monetary expenses, the third is that the kingdom will receive considerable replenishment.” In the above statement about on the positive side“clothing arrangement” Pososhkov directly states that it will contribute to the accumulation of money in the country. Pososhkov approached various items of import and export with the goal of preventing the outflow of money from the country and increasing the country's monetary treasures through foreign trade. Pososhkov gives many examples indicating the abnormal state of Russian imports and exports.

It should be noted that Pososhkov is dissatisfied with the fact that raw materials, and not finished goods, are exported from Russia, which is a source of enrichment for foreign merchants. Pososhkov believed that material intended for further processing and manufacturing of the finished product should be processed in the appropriate raw materials areas. He argued that “this is very necessary; wherever materials are born, they will be used there.” Violation of this rule, according to Pososhkov, leads to the fact that Russia’s foreign trade, to the detriment of the interests of Russian industry and trade, becomes very profitable for foreigners. Thus, Pososhkov insisted on the need to export not flax and hemp, but finished products made from them. And for this it is necessary to process them in Russian factories.

Contrasting the high prices for raw materials and food supplies abroad with their relative cheapness in Russia, Pososhkov wrote: “I believe that it is possible for us to prepare linens for all of Europe and, given their current price, sell them to them at a much lower price.” Pososhkov sees in establishing low prices for finished industrial products sold abroad is a strong weapon in the competition to conquer the European market. Pososhkov associated the export of not raw materials, but finished goods, with the influx of precious metals into the country, to which he, in the spirit of mercantilistic theory, attached great economic importance.

Pososhkovabout craft

On the issue of craft, Pososhkov is a supporter of the introduction of a “civil charter” regulating strict state supervision of “art”, surveillance for the purpose of control, in the person of “overseers” and the “chief ruler”.

The state of craft production in Russia, according to Pososhkov, largely depends on the question of the state of apprenticeship. Referring to the experience of foreigners, Pososhkov argued that strict adherence to the fixed term of apprenticeship should be ensured by anxiety, fear of severe punishment for its violation. The further fate of the student - up to the granting of the right to become an independent master and acquire students - is determined by the decision of the masters and the commander. Pososhkov was convinced that in the presence of the “civil charter” he was projecting, the students “will inevitably be good teachers and, having completely learned and taking a leave of absence from the master, will show their skills and leave to the highest artistic commander, then how will that commander determine whether he still needs to finish his studies , or I’ll hire other artisans to work, or he can be a master himself, then so be it.”

Pososhkov considered it necessary to brand the goods produced as a sign of their good quality, and to punish the production of unsuitable products with a high fine. Pososhkov considered it an appropriate form of increasing the knowledge of Russian artisans to widely attract highly qualified foreign craftsmen to train Russian people. The activities of such foreigners should be surrounded by honor and covered with glory. In his statements about craft, Pososhkov also dwells on the question of invention. He refers to foreign statutes, which, when creating something new, previously unknown, guard the interests of the inventor, guaranteeing him the exclusive right to his work. Speaking about the spread of invention in Rus', following the example of foreigners, Pososhkov proceeds from the principle of material interest. “And if this is how it is arranged in Rus', then the foreigners will also have many fictitious people. Many sharp people would deliberately begin to try to invent something new, from which he could profit. And now we have a lot of property being lost for dishonest citizenship.” Pososhkov directly emphasizes that due to the disorders that prevail in the matter of invention in Rus', innovations are fraught with unprofitability.

Pososhkov considered it expedient to “create a civil charter so that no one else is allowed to interfere with the invention of a new skill or craft, as long as that invention is alive.” Pososhkov was convinced that the development of crafts in Russia according to his project would lead not only to the fact that Russian craft production would reach foreign boundaries, but would also be able to surpass them. Pososhkov’s field of vision also included contemporary Russian manufacturing. Thus, on the issue of attracting labor to the manufactory, Pososhkov spoke out for the need to forcibly recruit vagabonds and beggars into the ownership of factory owners. Pososhkov was convinced that recruiting workers in this way would ensure the availability big army forced labor. According to Pososhkov, it is necessary to “make... a decree so that the beggars, those wandering the streets, the young and the middle-aged will be seized...”. Pososhkov suggested that “young men and women should be taught to spin, and older ones to weave, and others to bleach and polish, then, having learned, they would be masters.” “I believe,” Pososhkov assured, “that it is possible to recruit a thousand or ten more of those revelers and, by building workshop houses, teaching those parasite revelers, it is possible to manage a lot of things for them.”

According to Pososhkov, breeders who use forced, dependent forced labor of beggars and vagabonds will become their eternal owners, turning them into their serfs, regardless of who they belonged to before their capture. Pososhkov paints a bright, rosy picture future fate this enslaved people. “... Beggars, tramps and parasites will all be exhausted, and instead of street wandering, everyone will be industrialists. And when they learn completely and become rich, they themselves become masters, and the kingdom will be rich from their craft and expand in glory.”

Pososhkov advised the construction of factories to be confined to uninhabited areas with cheap food, at the expense of the treasury and with their subsequent transfer to quitrent. “And for the sake of royal enrichment, it is necessary to first build houses from the royal treasury for such things in large places in those cities where bread and grub are cheaper, in Zaotsky places, or where it is decent to do something, and impose a quitrent on them, so that people get rich, and the royal the treasury increased." Thus, Pososhkov declares that the development of industry in the country should have as its goal the enrichment of “the people,” i.e., factory owners and merchants. However, not the least place in the tasks that Pososhkov sets for the industry being established in the country is given to enriching the treasury and accumulating monetary treasures in the country. Pososhkov emphasized in every possible way the need to provide substantial financial assistance at the expense of the treasury to large, enterprising factory owners and manufacturers. According to Pososhkov, the treasury should also finance small industrialists who are not able to organize a large enterprise. Loans should be issued at 6% per annum, and for short-term loans - at 1% per month.

Pososhkov about the peasantquestion

In his statements on the peasant question, Pososhkov set the goal of protecting the peasantry “from ruin and from insults and not allowing them to remain in laziness, so that laziness does not lead them to ultimate poverty.” In Pososhkov’s view, the poverty of peasant life was explained by the presence of laziness of the peasants, lack of control by the authorities, landowner violence and neglect.

Characterizing the unlimited self-will, autocracy, and lack of legality in the relationship of landowners to peasants, Pososhkov wrote: “...Landowners impose burdens on their peasants that are unbearable, for there are such inhumane nobles that during working hours they do not give their peasants a single day to spare. something to work for yourself. And so they will lose the entire ploughing and haymaking season, or what was imposed on the peasants as a quitrent or table supplies and, having taken away that position, they also demand an excessive tax from them. And with this excess, the peasantry is driven into poverty, and if the peasant becomes less well-fed, he will increase taxes on him. And due to their current order, a peasant can never get rich from such a landowner, and many nobles say: “Don’t let the peasant get rich, but shear him like a sheep until he’s naked.” And doing this, they devastate the kingdom, they rob them so much that they don’t even leave some goats, and because of such needs they leave their houses and some flee to lower places, some to stolen places, and others to foreign countries, and so they inhabit foreign countries , but they leave theirs empty.”

Pososhkov does not limit himself to stating the difficult situation of the enslaved peasantry, languishing under the yoke of backbreaking, forced labor. He tries to reveal the roots of the enslavement of peasants and puts forward an original point of view on this issue. Pososhkov wrote: “The landowners are not centuries-old owners of the peasants, for this reason they do not take great care of them, but the direct ruler of the All-Russian autocrats, they own temporarily. And for this reason, the landowners should not ruin them, but should protect them by royal decree, so that the peasants are straight peasants, and not beggars, since peasant wealth is royal wealth.” Based on the idea of the temporary nature of landownership, Pososhkov considered it necessary for state intervention in the relationship between landowners and peasants, which should limit the arbitrariness of landowners, their unbridled desire to appropriate the entire product of the peasants’ labor, dooming them to poverty.

According to Pososhkov, the law should regulate, subordinate peasant labor to precisely established rules - whether it is expressed in corvee days or quitrent. At the same time, the landowner must ensure that the peasant does not deviate into “laziness,” so that he “doesn’t walk around for nothing, but works as hard as he can to support himself.”

Pososhkov entrusted the development of a law that should establish the size of peasant duties to the congress of nobles. This law is subject to approval by the king. Believing that peasant duties should be based on the peasant yard, Pososhkov at the same time demanded that the amount of land and crops be taken into account. He pointed out the need to “arrange peasant households according to the land they have been given, what they own and how much grain they sow for themselves from that land.” Pososhkov insisted that “according to common sense, the peasant yard should consider not the gates, nor the smoke from the huts, but the ownership of the land and the sowing of its property.”

As for the content that Pososhkov put into his understanding of the “whole yard”, by it he meant six acres of arable land - for sowing four quarters of rye, eight quarters of spring, mowing twenty knees of hay and land under the estate in 600-720 square fathoms. A peasant could not own a whole yard, but only a share of the yard. “And if some peasant is allotted land that cannot sow even a quarter of rye on it, then that yard should not be written as a quarter of the yard, but perhaps as a sixth share of the yard.”

A peasant could also own a plot of land larger than one yard. “And if any landowner, seeing a peasant family man and horse owner, gives him land with pleasure, so that he will sow ten quarters of rye for the summer, and twenty for spring, and will give him 50 kopecks for haymaking, then from such a peasant you can take both His Imperial Majesty and the landowner from the third half of the yard.” Thus, Pososhkov proceeded from the need to respect the difference in allocating land to peasants.

Of great interest are Pososhkov’s statements about introducing peasants to literacy. The spread of literacy among the peasants, according to Pososhkov, will play a big role in limiting autocracy, self-will and extortion, robbery, and the atrocities of the royal servants. The arbitrariness of the latter causes great losses to the peasantry. Pososhkov even spoke out in favor of forcing peasant children to learn to read and write. At the same time, Pososhkov does not ignore the interests of landowners and the needs state apparatus. “And when a teacher is taught to read and write, they will not only be more convenient for the landowners to manage their affairs, but they will also be more convenient for state affairs. Most of all, they will be suitable for the Sotsky and Fifty Velmi and no one will harm them and will not take anything from them in vain.”

Defending the inviolability of peasant land, trying to guarantee it from any encroachment by landowners, Pososhkov demanded progressive measures - the separation or dissociation of peasant land from the landowners: “... From the land that will be allocated to peasant households, from that land the peasants will pay according to your yard salary... and for this reason, that land should not be considered by the landowners.” Pososhkov's project, beneficial to the peasantry, was in close connection with his views on land as the property of the king, the property of the state. Pososhkov left serfdom intact. Nominated by him practical suggestions on the peasant question they were advanced for their time.

I.T. Pososhkov was the greatest Russian economist early XVIII c., an outstanding and original representative of mercantilism. Pososhkov put forward a program for the development of Russia's productive forces that was progressive for its time. Pososhkov defended ideas that were advanced for his time regarding the development of trade, crafts, Agriculture. Pososhkov fought for the economic independence of Russia from the West. Being a supporter of the concept of a trade balance, Pososhkov stood above Western European mercantilists on a number of issues. The interpretation of the issue of wealth was deeper. Pososhkov compares favorably with the mercantilists of the West big interest to the peasant question. Pososhkov is an outstanding representative of world economic thought of his time.

Tutoring

Need help studying a topic?

Our specialists will advise or provide tutoring services on topics that interest you.

Submit your application indicating the topic right now to find out about the possibility of obtaining a consultation.

POSOSHKOV IVAN TIKHONOVICH

Pososhkov (Ivan Tikhonovich) is a famous Russian economist, one of those self-taught teachers of Moscow church literature who, while firmly adhering to the old national principles, nevertheless clearly understood that Russia must move forward and that salvation lies only in the full development of its forces. Biographical information regarding Pososhkov is extremely scarce. He was born in the village of Pokrovskoye, near Moscow, around 1670. His name appears in documents for the first time in the case of the builder of the St. Andrew's Monastery, Avramiya, who gave Peter notebooks about the causes of discontent among the people. In this case, the peasants “Ivashka and Romashka P.” were brought to justice, “among the longtime friends and bread-eaters,” among others. This time Pososhkov managed to extricate himself from the case. Then Pososhkov leads an active life as a pioneer of the emerging Russian industry, and sometimes occupies an official position (in vodka affairs). He tries to make inventions in the military field, generally works a lot, writes, manages to become a relatively wealthy man, but does not acquire a prominent position among Peter’s employees and dies under Catherine I on February 1, 1726, in the Peter and Paul Fortress. The reason for the arrest has not been precisely clarified, but, apparently, Pososhkov’s death was caused precisely by his writing - “Books on poverty and wealth, this is an expression of what causes poverty, and from which gobzo wealth multiplies” - a work that constitutes the main basis of his fame . In terms of the strength of the language, the mass of issues raised, and the richness of thought, this work gives every right to call Pososhkov the first Russian economist. Much of what Pososhkov spoke about was the issue of the day and was discussed in one way or another by other contemporaries of Peter; but to compile a whole treatise on this, and, moreover, in the absence of acquaintance with at least the rudiments of Western European economic science, remarkable talent was required, the power of which becomes even more obvious when comparing Pososhkov’s book with the works of so-called mercantile theorists, poor in thought and language, especially German ones. Pososhkov’s essay is not of a narrowly economic nature. This is a whole program for the reconstruction of the Russian state, including such measures that have not been implemented to this day. Pososhkov represents an original combination of mercantile ideas with the canonical ideas of the West - a combination that is all the more curious because it was created outside of any literary Western European influences. Pososhkov is first of all a seeker of Christian truth, and then a nationalist, a supporter of democratic centralization on the basis of the absolute monarchical principle. His belief in absolutism is so great that he even finds it possible to mint money without being in accordance with the real value of the metal. He also dreams that the state is able to set a “natural, fair price,” and recommends that the issue be resolved very simply: “if anyone takes a price that is not truly excessive, he will be fined and flogged with batogs or whips, so that he will not do so in the future.” He is aware that the main source of wealth is land, but is inclined to attach great importance to the abundance of money. He understands that satisfaction with fiscal goals alone cannot serve as the basis for a reasonable state policy and that only on the basis of industrial development is the prosperity of the state possible. The government's concern should be directed to the development of national productive forces. There are many untouched natural resources in Russia: when we develop independent production of daily necessities, foreigners will be “more kind to us, they will put aside all their former pride and begin to chase us.” Ways to encourage domestic industry - a tariff, the organization of warehouse trading places, the development of a guild system, the attraction of foreign craftsmen to train Russians, the development of literacy among the people, etc. Pososhkov insists on regulating the relations of landowners to peasants, justifying his opinion by the fact that “landowners are not centuries old for peasants.” The owners, for this reason, do not take very good care of them, and their direct owner is the All-Russian Autocrat." He mourns the poor cultivation of the land, the destruction of forests, the harm of partitions, insists on the need for land surveying, rebels against the poll tax: “in mental terms,” he says, “there is no point in being, since the soul is an intangible thing and incomprehensible to the mind, and prices poor; one must value grounded things,” and, moreover, “collect the treasury so as not to ruin the kingdom.” He is an opponent of the plurality of taxes: “many are fictitious, although they have invented taxes to replenish land, capitation, homutey, bathhouse, cool, from water vessels, planted, pavement, bee, leather, mowing, and from tenths of haulers and call that collection petty fees: both The treasury cannot be filled with those mercenary collections, except for the people; it is a great trumpet: a petty collection is small.” In his opinion, it is necessary to establish a single “state truthful tax, established since the Incarnation of Christ, that is, a tithe,” and a single duty should be established on goods, “for even the same skin is flayed from an ox.” Regarding Pososhkov’s salt, he is of the opinion that “it’s better for her to be in free trade.” In addition, Pososhkov owns the “Paternal Testament” - Domostroy of the 17th century. and “The Mirror of the Schismatic’s Superstition,” which examines the causes of the schism. Pososhkov’s works were published by Pogodin (vol. 1, Moscow, 1842; vol. 2, Moscow, 1863), “Paternal Testament” - E. Prilezhaev (St. Petersburg, 1893). See Brickner "Ivan Pososhkov" (St. Petersburg, 1876); Alexey Tsarevsky "Pososhkov and his works" (Moscow, 1883); N. Pavlov-Silvansky "Projects of reforms in the notes of contemporaries of Peter the Great" (St. Petersburg, 1897). A. Miklashevsky.

Brief biographical encyclopedia. 2012

See also interpretations, synonyms, meanings of the word and what POSOSHKOV IVAN TIKHONOVICH is in Russian in dictionaries, encyclopedias and reference books:

- POSOSHKOV IVAN TIKHONOVICH in big Soviet encyclopedia, TSB:

Ivan Tikhonovich (1652, Pokrovskoye village, now Moscow region, - February 1, 1726, St. Petersburg), Russian economist and publicist. Born into the family of a jeweler. Was engaged... - POSOSHKOV IVAN TIKHONOVICH

(1652-1726) Russian economist and publicist. A supporter of the reforms of Peter I, he advocated the development of industry and trade, proposed to strengthen the exploration of mineral deposits... - POSOSHKOV IVAN TIKHONOVICH

- POSOSHKOV IVAN TIKHONOVICH

(1652 - 1726), Russian economist and publicist. Supporter of the reforms of Peter I, advocated the development of industry and trade, more active research... - POSOSHKOV in the Pedagogical Encyclopedic Dictionary:

Ivan Tikhonovich (1652-1726), writer, economist. Supporter of the reforms of Peter I. However, contrary to his policy, he did not strive to focus on Western Europe; ... - IVAN in the Dictionary of Thieves' Slang:

- pseudonym of the leader of the criminal... - IVAN in the Dictionary of meanings of Gypsy names:

, Johann (borrowed, male) - “God’s grace” ... - TIKHONOVICH in 1000 biographies of famous people:

(1855 - 1884) - ensign, member military organization "Narodnaya Volya". On August 17, 1882, being the head of the guard of the Kyiv prison castle, ... - IVAN in the Big Encyclopedic Dictionary:

V (1666-96) Russian Tsar (from 1682), son of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. Sick and unable to government activities, proclaimed king along with... - POSOSHKOV

(Ivan Tikhonovich) - a famous Russian economist, one of those self-taught readers of Moscow church writing who, while firmly adhering to the old national principles,... - IVAN in the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Euphron:

cm. … - IVAN in the Modern Encyclopedic Dictionary:

- IVAN in the Encyclopedic Dictionary:

I Kalita (until 1296 - 1340), Prince of Moscow (from 1325) and Grand Duke Vladimir (1328 - 31, from 1332). Son … - IVAN in the Encyclopedic Dictionary:

-DA-MARYA, Ivan-da-Marya, w. Herbaceous plant with yellow flowers and purple leaves. -TEA, fireweed, m. Large herbaceous plant of the family. fireweed with... - POSOSHKOV

POSOSHOV Iv. Quiet. (1652-1726), grew up. economist and publicist. He was self-taught; practical He combined the activities of an entrepreneur with lit. classes. Supporter of Peter's reforms... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN CHERNY, scribe at the court of Ivan III, religious. freethinker, member F. Kuritsyn's mug. OK. 1490 ran for... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN FYODOROV (c. 1510-83), founder of book printing in Russia and Ukraine, educator. In 1564 in Moscow jointly. with Pyotr Timofeevich Mstislavets... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN PODKOVA (?-1578), Mold. Gospodar, one of the hands. Zaporozhye Cossacks. He declared himself the brother of Ivan Lyuty, in 1577 he captured Iasi and... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN LYUTY (Grozny) (?-1574), Mold. ruler since 1571. He pursued a policy of centralization and headed the liberation. war against the tour. yoke; as a result of betrayal... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN IVANOVICH YOUNG (1458-90), son of Ivan III, co-ruler of his father from 1471. Was one of the hands. rus. troops while "standing... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN IVANOVICH (1554-81), eldest son of Ivan IV the Terrible. Participant of the Livonian War and oprichnina. Killed by his father during an argument. This event … - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN IVANOVICH (1496 - ca. 1534), the last leader. Prince of Ryazan (from 1500, actually from 1516). In 1520 he was planted by Vasily III... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN ASEN II, Bulgarian king in 1218-41. Defeated the army of the Epirus despot at Klokotnitsa (1230). Significantly expanded the territory. Second Bolg. kingdoms... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN ALEXANDER, Bulgarian Tsar in 1331-71, from the Shishmanovich dynasty. With him is the Second Bolg. the kingdom split into 3 parts (Dobruja, Vidin... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN VI (1740-64), grew up. Emperor (1740-41), great-grandson of Ivan V, son of Duke Anton Ulrich of Brunswick. E.I. ruled for the baby. Biron, then... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN V (1666-96), Russian. Tsar since 1682, son of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. Sick and incapable of government. activities, proclaimed king... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN IV the Terrible (1530-84), leader. Prince of Moscow and "All Rus'" from 1533, the first Russian. Tsar since 1547, from the Rurik dynasty. ... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN III (1440-1505), leader. Prince of Vladimir and Moscow from 1462, “Sovereign of All Rus'” from 1478. Son of Vasily II. Married to... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN II the Red (1326-59), leader. Prince of Vladimir and Moscow from 1354. Son of Ivan I Kalita, brother of Semyon the Proud. In 1340-53... - IVAN in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

IVAN I Kalita (before 1296-1340), leader. Prince of Moscow from 1325, led. Prince of Vladimir in 1328-31 and from 1332. Son of Daniel ... - POSOSHKOV in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedia:

(Ivan Tikhonovich)? a famous Russian economist, one of those self-taught readers of Moscow church literature who, while firmly adhering to the old national principles,... - IVAN

The king changing profession in... - IVAN in the Dictionary for solving and composing scanwords:

Boyfriend... - IVAN in the Dictionary for solving and composing scanwords:

Fool, and in fairy tales it’s all about princesses... - IVAN in the Russian Synonyms dictionary:

Name, … - IVAN in Lopatin’s Dictionary of the Russian Language:

Iv'an, -a (name; about a Russian person; Iv'an, who do not remember ... - IVAN

Ivan Ivanovich, … - IVAN full spelling dictionary Russian language:

Ivan, -a (name; about a Russian person; Ivana, not remembering... - IVAN in Dahl's Dictionary:

the most common name we have (Ivanov, which means rotten mushrooms, altered from John (of which there are 62 in the year), throughout Asian and ... - POSOSHKOV in the Modern Explanatory Dictionary, TSB:

Ivan Tikhonovich (1652-1726), Russian economist and publicist. Supporter of the reforms of Peter I, advocated the development of industry and trade, proposed strengthening... - IVAN

- IVAN V Explanatory dictionary Russian language Ushakov:

Kupala and Ivan Kupala (I and K capitalized), Ivan Kupala (Kupala), pl. no, m. The Orthodox have a holiday on June 24... - YABLOCHKOV MIKHAIL TIKHONOVICH

Yablochkov (Mikhail Tikhonovich) - writer. Born 1848; completed a course at Moscow University at the Faculty of Law. He was the director of the people's... - SHCHEGLOV NIKOLAY TIKHONOVICH in Brief biographical encyclopedia:

Shcheglov (Nikolai Tikhonovich, 1800 - 1870) - author of textbooks on arithmetic, physics, etc.; was brought up in the Tula seminary, then in ... - TRAKHANIOTOV PETER TIKHONOVICH in the Brief Biographical Encyclopedia:

Trakhaniotov (Petr Tikhonovich) - okolnichy of the 17th century. At the beginning of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich, he was the head of the Pushkar order and was, apparently, one... - STEPANOV PAVEL TIKHONOVICH in the Brief Biographical Encyclopedia:

Stepanov (Pavel Tikhonovich) - zoologist, son of Tikhon Fedorovich Stepanov (see below), born in 1839, studied at Kharkov University in ...

Russian kingdom

Ivan Tikhonovich Pososhkov(, Pokrovskoye village, near Moscow - February 1, 1726, Peter and Paul Fortress, St. Petersburg) - an outstanding Russian economist, publicist, entrepreneur and inventor. The first Russian economist-theorist. The main work is the socio-economic treatise “The Book of Poverty and Wealth” (published in 1842).

Supporter of the military and economic reforms of Peter I. He adhered to mercantilist views. He advocated the development of industry and trade, reform of the tax system (reduction and streamlining of taxes) and money circulation(proposed to make it based on copper money, instead of silver and gold), rational use natural resources, increasing exploration of mineral deposits. For the first time he took the initiative to legislatively regulate the duties of serfs. Repressed (1725). He died in the Peter and Paul Prison.

Biography

Very little is known about Pososhkov. The first mention of him in documents is found in the case of the builder of the St. Andrew's Monastery, Avramiya, who submitted documents to Emperor Peter I that revealed the reasons for the discontent among the people. In this case, among others, the peasants “Ivashka and Romashka P.” were brought to justice. In subsequent years, Pososhkov worked a lot, managed to become a wealthy man, but he did not receive a high place among Peter’s associates. Pososhkov died in the Peter and Paul Fortress; the reason for his arrest was most likely the “Treatise on Poverty and Wealth” he wrote, which advocated limiting noble land ownership. In addition, Pososhkov owns “The Father’s Testament” and “The Mirror of the Schismatic’s Superstitious Wisdom.”

A book about poverty and wealth

The full title of this book is “The Book of Poverty and Wealth, this is an expression of what causes poverty, and from what gobzo wealth multiplies,” it belongs to the number of outstanding works not only of Russian, but also of world economic literature. The treatise raised very deeply problems that were discussed at a lower level in the circle of Peter I, and were also partially raised in the works of Western economists, although the treatise was created completely independently of them. The treatise is a combination of mercantilist theory with Western ideas. He demands a restriction of serfdom on the basis of absolutism: “the landowners are not centuries-old owners of the peasants, for this reason they do not take great care of them, but their direct owner is the All-Russian Autocrat.” Pososhkov proposed limiting prices by punishing those who inflate prices: “if anyone takes a price that is not truly excessive, he will be fined and flogged with batogs or whips, so that he does not do this in the future.” He is an opponent of multiple taxes; in his opinion, a single “state... tax..., that is, a tithe” should be established, and a single duty should be established on goods.

Without reducing wealth to money, Pososhkov distinguished between material and immaterial wealth. By material he meant the wealth of the state (treasury) and the wealth of the people. Which can currently be identified with the gross product. Under the insubstantial - “true truth”, i.e. legality, legal conditions, good governance of the country - those values that today we call “institutions”. Therefore, Pososhkov can be called the forerunner of Russian institutionalism. He called productive labor the source of wealth, and the reasons for poverty were the backwardness of agriculture, insufficient development of industry, and the unsatisfactory state of trade. To destroy poverty and achieve wealth, Pososhkov proposed two conditions: 1) destroy idleness and force all people to work diligently and productively; 2) resolutely combat unproductive costs and implement the strictest savings.

Being an ideologist of the merchant class, Pososhkov devoted a lot of space in his work to issues of internal trade. In an effort to make the merchants a monopolist in trade, he proposed banning nobles and peasants from engaging in trade and spoke out for a “set price” regulated from above by a system of supervision and control, i.e. this issue defended outdated views. Pososhkov was attentive to foreign trade, the organization of which was supposed to protect the Russian merchants from foreign competition and contribute to the increase of money in the country, considered it necessary to import only what was not produced in Russia. Restricting the import of luxury goods was, in his opinion, supposed to save money in the country. He proposed stopping the export of industrial raw materials from the country and exporting only finished products abroad. Pososhkov's views on money are original: he defended the nominalistic theory of money.

Contributions to economics

In the person of Pososhkov, Russian economic thought of the late 17th - early 18th centuries. stood firmly at the level of world economic thought of that time.

I. T. Pososhkov was the first consistent institutionalist in history economic studies. He writes about the intangible wealth of a country - a set of civic foundations - institutions that contribute to the healthy functioning of the economy and society.

For the first time, he raises the question of material wealth, as not about the money supply in the country, but about material wealth in the hands of the state and the people. Which can currently be identified with the gross product.

Especially great attention Pososhkov paid attention to the development of Russian industry, the problems of which are still relevant today. Among the measures aimed at its development, he proposed building factories at public expense and then transferring them to private hands.

While supporting the ideology of the merchants, Pososhkov at the same time expressed the interests of the peasantry. Without openly demanding the abolition of serfdom, he sought to limit the power of the landowners to certain limits. The merit of I. T. Pososhkov is that he was able to correctly, within the limits of his era, understand the main tasks of Russia.

The economist’s views, set out in the book “On Poverty and Wealth,” were innovative not only in Russia, but also in the international arena, which makes I. T. Pososhkov an outstanding economist even today, since he was the first to raise questions and explore processes and phenomena , which are relevant in modern society.

Notes

Literature

- Pogodin M.P. Preface // Works of Ivan Pososhkov. - M.: Printing house of Nikolai Stepanov, 1842.

- Kafengauz B. B. I. T. Pososhkov. Life and activity. - M.: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1951. - 204 p.

- Platonov D.N. Ivan Pososhkov. - M.: Economics, 1989. - 142 p.

- Pashkov A.I., Economic views of I.T. Pososhkova, “Izv. Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Department of Economics and Law", 1945, No. 4

- History of Russian economic thought, vol. 1, part 1, M., 1955; Mordukhovich L. M.

- Essays on the history of economic doctrines, M., 1957, ch. 6; Mordukhovich L. M.

- The main stages of the history of economic doctrines, vol. 1, M., 1970.

- Gukasyan G.M., Nintsieva G.V., History of economic thought, Publishing house "Peter", 2008, 168 p.

Categories:

- Personalities in alphabetical order

- Scientists by alphabet

- Born in 1652

- Deaths on February 12

- Died in 1726

- Economists in alphabetical order

- Economists of Russia

- Entrepreneurs of Russia

- Inventors of Russia

- Repressed in the Russian Empire

- Prisoners of the Peter and Paul Fortress

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

See what “Pososhkov, Ivan Tikhonovich” is in other dictionaries:

Pososhkov (Ivan Tikhonovich) is a famous Russian economist, one of those self-taught teachers of Moscow church writing who, while firmly adhering to the old national principles, nevertheless clearly understood that Russia must move forward and that... ... Biographical Dictionary

Pososhkov Ivan Tikhonovich- . He belonged to a family of hereditary jewelers (silversmiths) who worked for the Armory Chamber; As a child I learned various crafts... Dictionary of the Russian language of the 18th century

- (1652 1726) Russian economist and publicist. A supporter of the reforms of Peter I, he advocated the development of industry and trade, and proposed strengthening the study of mineral deposits. Major works: Book on Poverty and Wealth (1724,... ... Big encyclopedic Dictionary

- (1652, Pokrovskoye village, now Moscow region, ‒ 1.2.1726, St. Petersburg), Russian economist and publicist. Born into the family of an artisan jeweler. He was engaged in various crafts, then became a merchant, entrepreneur, and owned land. P.’s main work is “The Book... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Pososhkov, Ivan Tikhonovich- POSOSHKOV Ivan Tikhonovich (1652 1726), Russian economist and publicist. A supporter of the reforms of Peter I, he advocated the development of industry and trade, and more active exploration of mineral deposits. Main works “Book about ... ... Illustrated Encyclopedic Dictionary

Writer of Peter's time, b. near Moscow in 1652 or 1653, died on February 1, 1726 in St. Petersburg. His father was a quitrent peasant of the palace village of Pokrovskoye near Moscow, which is now part of the city of Moscow. This village... ... Large biographical encyclopedia

- (1652 1726), Russian economist and publicist. He was self-taught; He combined the practical activities of an entrepreneur with literary studies. Supporter of the reforms of Peter I, advocated the development of industry and trade, proposed strengthening... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

POSOSHKOV Ivan Tikhonovich (1652-1726) was born in 1652 into the family of a silversmith in the village of Pokrovskoye near Moscow. His father was one of the peasants who were under the jurisdiction of the Armory Chamber and worked in various workshops of the Sovereign's court. He was engaged in various crafts and trade, and became a major industrialist and landowner. In 1694-1696. worked on a money machine as a gift to Peter I, and in 1697 demonstrated “fire slingshots” to the Tsar. He had a distillery, a sulfur mine, looked for oil, tried to start a playing card factory, worked as a fountain and vodka master. Towards the end of his life he bought houses, villages, and land in Novgorod and St. Petersburg. Along with entrepreneurship, he was engaged in journalism, responding to all the pressing issues of the era. In 1701, after the defeat of the Russian army near Narva, he composed a note for Peter I “On military behavior,” proposing measures to create a combat-ready army. Pososhkov outlined his views on issues of education, ethics, and church problems in 1703-1710 in notes addressed to Metropolitan Stefan Yavorsky; he proposed creating a patriarchal academy, teaching children of the clergy, printing textbooks refuting heresy, and considered it necessary to simplify the Church Slavonic alphabet.

Pososhkov combined his entrepreneurial and inventive activities with literary ones, leaving several projects and three polemical essays, in which he put forward a number of proposals for the development of the Russian national economy. Towards the end of his life, Pososhkov wrote the book “On Poverty and Wealth,” which summarizes what was stated in other works. It was completed in 1724 and was intended for Peter I. Perhaps this book caused the arrest of the author and led to tragedy in the life of I.T. Pososhkova. In the 18th century, such works were intended, as a rule, for one, the most important reader - the Tsar-Father, with the desire to convey to him all the “untruths” and “malfunctions” and to propose measures that could help eradicate evil. It is not for nothing that in the dedication the author asks the emperor not to reveal his name, fearing that the snitches and offenders “will not allow me to live even a short time in the world, and therefore I will be my own murderer.” The words turned out to be prophetic. It is unlikely that Peter I himself had time to read the book. Most likely, she fell into the hands of the tsar’s henchmen, who saw in her a threat to “the word and deed of the sovereign.” In August 1725, Pososhkov was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, where he died on February 1, 1726.

"The Book of Scarcity and Wealth" general description

Pososhkov's main work, which brought him great posthumous fame, was completed by him in 1724, when the author was already 72 years old. It is devoted primarily to economic problems, as its expressive title shows - “The Book of Poverty and Wealth, which is an expression of why vain poverty occurs, and from which godly (abundant) wealth multiplies.”

It contains many proposals or projects relating to various aspects of state and public life. The content of the book is broader than what is said in the title, since, along with economic topics, it discusses issues of administrative structure, court, legislation, education, and talks about the situation of the peasantry. The book is divided into 9 chapters, which deal with the clergy, military affairs, justice, merchants, art (that is, craft and industry), robbers, the peasantry, land affairs, and in the last chapter - about the royal interest or about public finances.

"The Book of Poverty and Wealth" was the result of all literary activity Pososhkova. He used his previous writings for her. From his first work, “Report on Military Conduct,” he transferred into it an indication of the fire slingshots he invented, the chapter “On Spirituality” in it is close in content to the author’s letters to Stefan Yavorsky, and the entire section on the trial was transferred from the “Paternal Testament” , here is his latest “Deportation on Money”. The book reflects the author’s rich life experience, excellent knowledge of legislation; he often refers to the Code of 1649 and Peter’s decrees and criticizes them. The author intended the “Book of Poverty and Wealth” to be presented to Peter I, as is clear from the concluding words: “Hidden from human sight, having written with painstaking labor, I offer it to your royal majesty.”

In the surviving copies of the “Book of Poverty and Wealth,” dating back to the middle of the 18th century, there are curious, lively notes made by an attentive reader and included by a subsequent copyist in the text of the book. Against Pososhkov’s words about legend death penalty for blasphemy stands: “Look around, old man, and take in this speech: there is no sin that conquers God’s love for mankind.” In another place where it is recommended to introduce a single specified price for goods, the following words probably belong to the same person: “Old man, you can’t set one price, give a product one name, but there is more than one kindness. Now it’s time for you to lie!”

In a special eloquent report addressed to Peter, preserved only in drafts, separately from the book, Pososhkov expresses the main idea that permeates the “Book of Poverty and Wealth” and talks about the tasks that he had in mind. His “little book” should serve the prosperity and enrichment of the country, and in particular should contribute to the implementation of law and justice. He saw “in the ruling judges, the taxes in the subordinates, a lot of untruths and all sorts of malfunctions were happening” and decided to offer his book “before the eyes” of the king. The implementation of his proposals should increase state revenues, but he looks further, promises more than enriching the royal treasury, he means “the wealth of the whole people.” Along with national economic tasks, he promises the implementation of “truth” and the eradication of grievances and enmity, “high-ranking nobles can turn into meek sheep and will have love with the common people.” These lofty goals led him to develop an extensive program of transformation.

The roots of Pososhkov's economic views lie in the surrounding reality, which he perceived and assessed in accordance with his ideals. Pososhkov's views are original, economic proposals are full of vital and practical meaning.

According to their own political views Pososhkov was a supporter of the monarchy. At the same time, he was critical of the system and procedures of government in Russia, seeing them as an obstacle to eliminating poverty and increasing wealth in the country.

Pososhkov does not identify wealth with money, which is characteristic of representatives of mercantilism in Western Europe. He believed that the wealth of society is embodied not only in precious metals, but also in material goods. Pososhkov distinguishes between material and immaterial wealth. By material wealth he meant the wealth of the state (treasury) and the wealth of the people, by immaterial wealth - “true truth”, i.e. legality, legal conditions, good governance of the country.

Pososhkov set the goal of the state’s economic policy as “nationwide enrichment.” He wrote: “in which kingdom people are rich, then that kingdom is rich, but in which there are poor people, then that kingdom cannot be considered rich.” The growth of national wealth is beneficial to both the people and the state - this is Pososhkov’s main idea on this matter. His statements were progressive in nature and went beyond mercantilist ideas about wealth.

The purpose of the book, he said, was to show the reasons for the needless poverty of the state and the increase in wealth. Pososhkov was convinced that the plan of transformation he proposed would make it possible to transform Russia into a rich cultural and powerful power. He assured the tsar that if his recommendations were implemented, then “all our great Russia renovationist both in spirituality and in citizenship, and not only the royal treasures will be filled, the inhabitants of Russia will become rich and glorified." He hoped that with the improvement of life, enmity and grievances would disappear, and high-born nobles would treat the common people with love.

Pososhkov's economic views reflected the ideas of mercantilism, although he was not familiar with the works of Western economists of his time. Without any special education, Pososhkov independently came to the ideas of mercantilism, which then dominated the West. Therefore, he is rightfully considered an outstanding mercantilist in Russia. Pososhkov’s ideas reflect the specifics and characteristics of Russia, and therefore have many differences from Western ones.

Peter I was also a supporter of mercantilism, and his reforms were largely the implementation of this teaching, but in relation to a number of important issues management of economic life, Pososhkov’s views did not coincide with Peter’s ideas, and sometimes clearly contradicted them.

Pososhkov’s original ideas include the division of wealth into material and immaterial. By the first, he means the wealth of the state (treasury) and the people, and by the second, effective governance of the country and the presence of fair laws. Pososhkov’s reasoning about immaterial wealth was concretized by him in the demand for management reform, since it is reform that creates opportunities for eliminating the scarcity of the state and increasing wealth in the country. (Now that it is recognized that science is a direct productive force, it is not difficult to appreciate the progressiveness of similar views that took place almost 300 years ago.)

Pososhkov's principles on improving economic management were based on the decisive role of the state in managing economic processes. He was a strong supporter of strict regulation of economic life. The main lever of such regulation should be royal decrees, which he considered the most important means of implementing economic transformations. Among his many recommendations, we will name only two: to force all people to work, and to work diligently and productively, to destroy idleness in all its forms; resolutely combat unproductive costs, implement the strictest savings in everything; fight luxury and excesses in people's lives.

To eliminate poverty and achieve wealth in the country, the following two instructions of Pososhkov are of greatest importance: force all people to work, diligently and productively, destroy idleness in all its forms; resolutely combat unproductive costs and implement the strictest savings in everything.

The requirement for frugality in everything, economical spending of material goods and money runs like a red thread throughout Pososhkov’s entire book.

Based on national interests, he resolutely rebels against the predatory attitude towards the country’s natural resources and sets out the most appropriate, from his point of view, principles for their exploitation.

Pososhkov, like the future classics of bourgeois political economy A. Smith and D. Ricardo, connects the source of wealth with labor. His recommendations imply that work is the source of increasing wealth. In his opinion, no one has the right to live without work and eat bread for nothing. And it is necessary not only to work, but the work must be with “profit” (in modern language - with profit). Pososhkov establishes a clear connection between the growth of wealth and labor productivity, which once again emphasizes his perception of labor as an important source of wealth.

The non-economic form of coercion for Pososhkov, as well as for his contemporaries, and especially Russian ones, was a natural form of labor discipline. At the same time, he very convincingly substantiated the advantages of piecework wages compared to time-based wages. As an incentive to increase labor productivity, he recommended giving higher wages to workers at state-owned enterprises and criticized the petty behavior of managers who set workers extremely low wages (5 kopecks per day): “They think they will make a profit for the great sovereign by not feeding the artisans, and thus they make a great loss. And in all sorts of matters, our rulers die for a crumb, and where thousands of rubles are wasted, they supply them for nothing, and by not giving full food to the Russian people, they suppress the desire and diligence for mastery and do not allow good art to multiply ".

As for Pososhkov’s numerous recommendations about the strictest economy and the fight against luxury and excess, it must be especially emphasized that he did not limit these concepts to the sphere of everyday life, but considered them in a more in a broad sense from the standpoint of the interests of society. A striking example in this regard, his project is against the predatory attitude of the population towards natural resources. Figuratively speaking, he advocated for the preservation of the environment. He opposed the predatory destruction of young forests, young fish, the collection of unripe nuts and other similar measures that harm nature and society. The author of the project reasonably argued that the correct principles of using natural resources contribute to their multiplication, and harmful ones contribute to their destruction.

“The Book of Poverty and Wealth,” like Pososhkov’s previous works, is imbued with a deep patriotic feeling. The author is overwhelmed by a passionate desire to achieve the prosperity of our homeland, which is in no way inferior to other countries.

Pososhkov Russian economist book

Pososhkov’s book is imbued with an ardent love for the homeland and a desire to protect our country from all encroachments by foreigners, both in economic life and in military affairs. An independent, strong and prosperous country is Pososhkov’s ideal. However, he does not mean such changes that would destroy the social and political foundations of the feudal empire and in his specific projects remains within the framework of Peter’s state, in which “the rise of the class of landowners, the promotion of the emerging class of merchants and the strengthening of the national state of these classes occurred at the expense of the serfs.” the peasantry, from whom three skins were torn off."