While analyzing Krusenstern's letters, I quite unexpectedly came across a message that N. P. Rumyantsev was going to equip an expedition to Novaya Zemlya in 1819 or 1820, in which Dr. I. I. Eshsholts, a naturalist who sailed on the Rurik, was to take part . The implementation of this plan was postponed only because the Naval Ministry had already sent an expedition to those parts under the command of Andrei Lazarev, sibling famous naval commander. The swim was unsuccessful. But still, Kruzenshtern wanted to get acquainted with the map and journal of this expedition. He conveyed his request to Lazarev through the future Decembrist Mikhail Karlovich Kuchelbeker, brother of Wilhelm Kuchelbeker, Pushkin's comrade at the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum. Lazarev himself wanted to show the modest results of his voyage to the famous Russian navigator, who "has already aroused the rivalry of all European powers, and the proudest British must agree in it."

Lazarev, in his letter, is trying to convince Kruzenshtern of the senselessness of exploring a distant island.

"Detailed knowledge of the New Earth cannot bring the slightest benefit," he writes. Firstly, because of the cessation of fisheries off the coast of this island due to small benefits. Secondly, Novaya Zemlya is “almost impregnable from ice” and cannot give shelter to sailors. Thirdly, the riches stored in its bowels will require great sacrifices and costs and are unlikely to enrich those who undertake their development "in such ferocious and unfavorable climates."

It was difficult for Kruzenshtern to be embarrassed by such arguments. If we agree with Lazarev, then why explore the Northwest Passage, why look for land north of the Kolyma? Why look for the southern mainland? .. The climate there is no less severe. But the study of these lands and waters can strengthen the political power of Russia. He understood this very well, and by advice and deed he supported the idea of sending a new sea expedition to explore Novaya Zemlya, the shores of which were mapped very approximately.

Despite Andrei Lazarev's skepticism and Gavrila Sarychev's uncertainty about the success of the new voyage, it was decided to send the Novaya Zemlya brig to the polar voyage. Its commander was 25-year-old Fyodor Petrovich Litke, who had recently completed a round-the-world voyage on the sloop Kamchatka.

The appointment of Litke as head of the Novaya Zemlya Expedition turned out to be the beginning of that rapid ascent, which ended several decades later with the election of his president. Russian Academy Sciences. According to one of Litke's close friends, from adolescence all his thoughts and feelings were captured by the dream "to devote himself to pure science", and he did not part with this dream until the end of his life.

Fyodor Petrovich grew up as an orphan. His birth cost his mother's life. The son and mother were together for a little over two hours, and then Fedor was left alone. His father, stepmother, relatives did not care about the baby. They sent him to a private boarding school, from which they only let him go home on Sundays. But even at home he found the same indifferent walls and no less indifferent father.

F. P. Litke.

Published for the first time.

“I don’t remember,” Litke recalled in his Autobiography, “that someone caressed me, even patted me on the cheek, but spanking of a different kind I happened to experience, mostly at the slander of my stepmother.

Soon Litke also lost his father. Neither he nor his sisters and brothers received a pension. Lonely children were dismantled by relatives. After four years of wandering in foreign corners, fate brought Fyodor Litke to the family of Ivan Savich Sulmenev. Sulmenev with a team of sailors made a land crossing from Trieste to St. Petersburg. Passing through Radzivilov, he turned out to be a guest at Uncle Litke's house, saw his sister Natalya Fedorovna, fell in love, got married and took her to Kronstadt. The family of the newlyweds and sheltered Litke. Sulmenev was a sailor of the old school, with a very mediocre education, but he had a very sympathetic soul and "almost female sensitivity."

“All my life,” Litke wrote, “I have not met kindest person more ready to serve and be useful to everyone with complete selflessness. From the very first minute of our acquaintance, he fell in love with me as a son and I him as a father.

They carried this feeling for each other throughout their lives.

Litka was fifteen years old when Napoleon's invasion of Russia began. In the formidable year of 1812, Fyodor Litke begged him to volunteer for the fleet, and a year later he fought the French near Danzig. The courage and courage of a 16-year-old boy did not go unnoticed. He was awarded the Order of Anna of the fourth degree.

The battles of the Patriotic War died down. Napoleon was overthrown. Peace reigned over Europe. But Fyodor Litke did not want to part with the fleet. Soon fate brought him aboard the sloop Kamchatka, commanded by the famous navigator Vasily Mikhailovich Golovnin.

On August 26, 1817, on the very day when everyone was celebrating the fifth anniversary of the “Battle of Borodino, eternally memorable for Russia”, “Kamchatka” dressed in sails and, having saluted Kronstadt, went towards dangers and trials. A month later she was in the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean. A tailwind was blowing it swiftly to the southwest.

Fyodor Litke has experienced storms and storms on three oceans and all latitudes from Cape Horn to the Bering Sea. He was at the helm, steered the sails, passed between the stone reefs, sailed in the fog. He was whipped by tropical downpours and cold rains, he was languishing from the heat and shivering from the icy wind. This life, full of dangers and hardships, fascinated him. He returned to Kronstadt as a real sailor. “... But a sailor of the Golovnin school, who in this, as in everything, was original,” Litke wrote. - His system was to think only about the essence of the matter, not paying any attention to appearance. I remember his answer to Muravyov, who was arming the Kamchatka and probably asked something about the spars. “Remember that we will not be judged by blocks and other trifles, but by what we do good or bad on the other side of the world.”

Contemporaries unanimously admit that Golovnin had a profound influence on Litke. This navigator, straightforward in his judgments and bold in his actions, "was distinguished by a bright mind and a broad, one might say, statesmanlike view." He so mercilessly criticized the policy of the autocracy in relation to the navy that Dmitry Zavalishin considered him a Decembrist. And although he was not a member secret society, but certainly knew of its existence and sympathized with the ideas professed by its members. Golovnin possessed deep knowledge not only in maritime affairs, but also in many areas of science, not to mention an outstanding literary talent. Among the navigators of the first half of the 19th century, only Kruzenshtern can be compared with him in terms of the breadth of education, energy and love for the science of the sea. It is no coincidence that these two luminaries often speak together on issues of polar and marine research.

Litke tried to take an example from his teacher. Apart from the sea, nothing existed for him.

To get acquainted with the Arctic Ocean, Litke asked to join the Arkhangelsk naval crew and made the transition to Kronstadt on a frigate. And a year later he was to test his strength in independent swimming.

His strict and demanding teacher never forgot about his pets. Ferdinand Wrangel, who was one of Litke's closest friends and sailed on the Kamchatka, he sent as the head of the Kolyma expedition, Matvey Ivanovich Muravyov, the main ruler of Russian America. Now it was Fyodor Petrovich's turn. On Golovnin's recommendation, he was appointed commander of the Novaya Zemlya brig.

V. M. Golovnin.

Without hesitation, Litke accepted this flattering offer. “And there was something to think about,” he recalled in his old age, believing that he lacked experience, knowledge, and the ability to lead people on a difficult polar expedition. Golovnin was well aware that he was dooming his pupil to a difficult test, and during all four voyages he helped him with advice, deed and intercession. Golovnin's letters have been preserved - vivid evidence of the sensitive concern of the famous navigator for the labors and fate of Fyodor Litke. He takes care of the appointment of capable officers on his ship, of providing the expedition with tools and supplies, reports naval news and comes to the rescue in difficult times.

Before Litke's departure from Petersburg, this stern man sends him a cordial letter in which he wishes him a good journey and good luck in his research. As soon as one of the midshipmen falls ill, Golovnin seeks the appointment of Nikolai Chizhov, a gifted officer, to the expedition. With Chizhov, he sends a letter to Litka, in which he reports on his efforts for the expedition, on the progress of the procurement of meat and other supplies. As a result of this care, during four voyages in the Arctic Ocean, the expedition did not lose a single person.

On July 14, 1821, the brig Novaya Zemlya leaves Arkhangelsk. Litke remembers by heart the mean lines of the order issued by the Minister of Marine:

“The purpose of the assignment made to you is not a detailed description of Novaya Zemlya, but only a review for the first time of its shores and knowledge of the size of this island by definition geographical location its main capes and the length of the strait, called Matochkin Shar, if ice and other important insanities do not prevent it.

The prescription does not really constrain his intentions. Apparently, the compiler of the instructions understood that in the Arctic Ocean the actions of the expedition leader would depend mainly on ice, storms and winds. But it is strictly forbidden to stay for the winter ...

Five days later, the brig reaches the entrance to the Arctic Ocean. Travelers have to pass several cans. Sailors know about their existence, but they are “shown differently on different maps”.

“On our brig,” wrote Litke, “there were two maps of the White Sea: one Mercator, printed, the writings of Lieutenant General Golenishchev-Kutuzov; the other is a flat handwritten, compiled in Arkhangelsk ... by the navigator Yadrovtsev on the basis of those maps that served as the basis for the first one. The printed map showed a two-sat jar, almost on the parallel of Orlov Nos, 19 miles from it, on the second, a long one and a half sazhen jar on the parallel of Konushin Nos, 20 miles from the coast.

Litke headed for the passage between these banks. A few hours later, the brig Novaya Zemlya was aground.

The tide had begun. The water quickly subsided, and the ship could easily capsize. They lowered the upper spars to make bases for the sides of the brig, but "the trees broke one after another into chips." “And finally, the ship tilted so much that I expected every minute that it would completely capsize,” Litke recalled this difficult hour. But the brig suddenly straightened up. Soon the jar dried up completely. It was possible, as in the dock, to repair the damage, but for now it was necessary to take care not to get them.

As soon as the tide reached full strength, the sailors leaned on deliveries, and soon the ship was "on free water."

Litke assumed that the expedition, having discovered the shoal, made a discovery. But a few months later, in Arkhangelsk, he received another “map of the White Sea, compiled in 1778 by Captain Grigorkov and Domazirov, on which two small banks are marked almost in the same place, drying up when the water is low.”

On the night of August 1, from the watch, they let me know that they were seeing the ship. Litke rushed to the bridge. No, the watchmen were deceived. It was ice, and behind them was a small island. A tiny patch of land called and beckoned sailors who were impatiently waiting for the shores of Novaya Zemlya to open. But the ice stood in their way as a continuous, insurmountable strip. We decided to descend to the south, hoping to find a passage closer to the mainland to the shores of Novaya Zemlya. Impatience seized the entire crew. Forty-three sailors peered intently at the eastern horizon. More and more often there was a cry: “Earth!” But it soon became clear that bizarre clouds were mistaken for the shore. Instead of solid ground, ice again rose in front of them on August 5. The ice was in the west, the ice was in the north, the ice was in the east, the ice hit the sides of the ship - it seemed that ice was everywhere. Then the brig was picked up by a strong current from the Kara Sea and carried to the place where the expedition was five days ago.

Day after day passed in fruitless attempts to reach the shores of Novaya Zemlya.

“So,” Litke said, “wherever we have hitherto turned, everywhere we have encountered obstacles insurmountable to our intentions, it was all the more regrettable for us that we had to miss, without the slightest benefit, several days of fine weather, which in these places must be so cherished. We were surrounded on all sides by ice giants flashing through the darkness, like ghosts. The dead silence was interrupted only by the lapping of waves on the ice, the distant roar of collapsing ice floes, and the occasional dull howl of walruses. All together it was something dull and terrible.

Calm and fog gave way to fresh winds. There was little hope for the success of the expedition, but the sailors did not lose their presence of mind. On August 11, for the first time, they saw the shores of Mezhdusharsky Island, but they could not get close.

A few more days were lost in fruitless attempts. We decided to make our way through the ice to the north. Only on August 22 did we manage to see the shores of Novaya Zemlya. In front of Litke and his companions rose a high stone mountain, in the cracks of which the snow that had not melted in summer sparkled; they called her the First Seen.

Off the coast of Novaya Zemlya.

For a whole week, sailors have been persistently looking for Matochkin Shar. But failure again haunts them. They inspect the unknown bays one by one, mistaking them for the entrance to the strait. The maps they have are more misleading than helpful. Litke knows that the position of prominent capes, mountains, and Matochkin Shar itself is probably shown inaccurately on them due to the "imperfection of marine science" in former times, but he has no reason to change their position yet.

Ice, driven by north winds, forces sailors to stop searching. The brig is heading for the southern tip of Novaya Zemlya. But here, too, ice and winds interfere with research work.

September 11, 1821 Litke returns to Arkhangelsk. He sends a report to the Naval Minister de Traverse and at the same time writes bitterly to Golovnin that his expedition had little better success than Andrei Lazarev's previous voyage.

“Although, after many efforts and dangers, we managed to approach the shore and survey it between the parallels of 72 ° and 75 °, our main purpose - measuring the length of Matochkin Shar - remained unfulfilled, despite the fact that, following along the coast to the north, and then back to the south, we had to pass it 2 times.

Litke is afraid that this failure will be attributed to his negligence, and asks for intercession. Golovnin uses his position and influence to protect his student from a big misfortune. He does not answer for a long time, trying to find out de Traversay's reaction to Litke's report. Finally, after a few weeks, he informs Fyodor Petrovich that the Minister of Marine "was very unhappy that you did not see Matochkin Shar." Golovnin presented de Traverse with an explanation in which he stated that the reason for the failure of the search for Matochkin Shar should be sought in the inaccuracy and inconsistency of the existing maps. So, on the map of Fyodor Rozmyslov, it is shown at 73 ° 40 "N, and on the latest English printed maps it is placed at 75 ° 30", and if the British are to be believed, then, therefore, Litke could not get through to the main goal of his journey due to heavy ice.

Golovnin not only succeeded in reassuring the minister. He was able to show Litke's voyage in such a favorable light that the head of the expedition was declared for his zeal and courage the gratitude that he really deserved. It was decided to continue searching for the entrance to Matochkin Shar and exploring the shores of Novaya Zemlya.

Meanwhile, Litke lived in Arkhangelsk for two and a half months, putting journals and maps in order. Putting on the map the points of Novaya Zemlya he described, he thought with anxiety about where Matochkin Shar was actually located. And at that time, fate brought him together with the navigator Pospelov, who in 1806 participated in an expedition to Novaya Zemlya, equipped by N.P. Rumyantsev. Pospelov kept handwritten maps and a sailing journal. They almost exactly matched the inventory of Litke, who made sure that, swimming near Mityushev, or Dry Cape, he was not far from Matochkin Shar. Then, comparing his maps with the maps of the coast-dwellers, he found on them the bays and bays he had explored and retained the old names for them.

In 1822, Litka again had to go to Novaya Zemlya. But since this island is freed from ice late, he was instructed to describe the Lapland coast from Svyatoy Nos to the Kola River. The travelers toured the islands of Nokuev, Bolshoi and Maly Oleniy, Kildin, Seven Islands and nearby parts of the Murmansk coast. The inventory was based on a network of astronomical points, but was not complete, since the expedition could not explore many bays and bays of the mother coast due to the short time.

August 4 Litke leaves the Kola Bay. Now he is heading for the shores of Novaya Zemlya. Four days later, in the gaps of fog, the very highest mountain that they first saw last year appears in front of the sailors. The expedition easily finds the Matochkin Shar Strait. Now that it has been found, Litke is in no hurry to start researching it. He heads on, in search of the northern tip of the island. The brig follows the unexplored shores. Dozens of new names appear on the map. He names one of the largest bays of Novaya Zemlya after Captain Sulmenev, in whom, after the death of his father, he found shelter and who taught him to love the sea.

Day after day, the brig sails along the picturesque rocky shores with blue glaciers. He is accompanied, like an honorary escort, by flocks of transparent icebergs. In each new cape, Litke is ready to see the northern tip of Novaya Zemlya. And when it seems to him that he is about to reach the goal, the eternal enemy of polar travelers again stands in his way - thick solid ice. A sailing ship cannot get through it. Meanwhile, from the mast, the “cape covered with snow” is already visible, behind which, as it seemed to the sailors, the sea stretched. Litke consoles himself with the hope that he has reached the northern tip of Novaya Zemlya, that he will succeed in penetrating the Kara Sea and charting its eastern shores. But the ice is getting closer and closer to the ship.

“The emptiness that surrounds us here,” writes Litke in his diary, “surpasses any description. Not a single animal, not a single bird broke the cemetery silence. In all fairness, the words of the poet can be attributed to this place:

And it seems that life in that country

It hasn't happened for a century.

Extreme dampness and cold quite corresponded to such deadness of nature. The thermometer was below freezing, the wet mist seemed to penetrate to the bone. All this together made a particularly unpleasant impression on the body, as well as on the soul. Remaining for several days in a row in this position, we already began to imagine that we were forever separated from the entire inhabited world. Despite this, however, our people were all healthy and, with the carelessness characteristic of sailors, they sang and amused themselves as usual, as much as circumstances allowed.

Soon Litka had to give up the idea of penetrating further north. Escaping from ice captivity, he goes south. After a short stay at the mouth of the Matochkin Shara, the expedition continues its exploration of the western shores of the Southern Island of Novaya Zemlya.

Litke takes revenge for last year's failure.

On September 6, 1822, he returned to Arkhangelsk with a map of almost the entire western coast of Novaya Zemlya.

Both Golovnin and his friend Ferdinand Petrovich Wrangel rejoice at the success of the navigator, wandering on dogs over the ice of the icy sea north of the coast of Chukotka ... St. Petersburg magazines provide their pages for Litke's articles. Kruzenshtern asks to tell in more detail about the results of the voyage, about the position of the northern tip of Novaya Zemlya. Scientist Karl Baer, head of the department at the University of Königsberg, intends to take part in a polar expedition and would like to know what a rich harvest awaits him, a biologist, in the polar seas, on the shores of Lapland and on Novaya Zemlya. First, they correspond with the mediation of Kruzenshtern, then they write to each other personally and write before last day Baer's life...

In the summer of 1823, Litke sails again in the Arctic Ocean. As in the previous year, he is first taking inventory of the coast of Murman, this time to the west of the Kola Bay.

Litke described the Motovsky Bay, Rybachy Peninsula, determined the location of the Norwegian fortress Vardeguz, thus linking to this point the completed inventory, in which there were many omissions due to unfavorable weather and lack of time. Three years later, Litke's friend, Lieutenant Mikhail Frantsevich Reinecke, had to deal with its clarification.

In July 1823, Litke appeared off the coast of Novaya Zemlya for the third time. He hurries north and soon becomes convinced that the cape, at which he was stopped by ice a year ago, is not the northern tip of the island. That is not Cape Desire, but Cape Nassau. But he again fails to penetrate to the north. Ice blocks the expedition's path again. Litka follows to Matochkin Shar. He is engaged in an inventory of its shores, depth measurements, observations of currents, and astronomically determines the western and eastern mouths of the strait. He wants to go to the Kara Sea, but solid ice closes the exit from Matochkin Shar.

Having finished work in the strait, Litke descends to the south, on the way refining the inventory of the western coast of the South Island of Novaya Zemlya. Soon it reaches Kusov Nos at the southern tip of the island. Further, as far as the eye can see, the ice-free Kara Sea stretches. It seems that travelers had the opportunity to explore the eastern coast of Novaya Zemlya.

Litke is indecisive. He is aware that the cause of the icelessness was the steady westerly winds, and that with the first easterly wind the ice would again move towards the shores of Novaya Zemlya. Fedor Petrovich faces a choice - whether to go to the Kara Sea or return to Arkhangelsk. And then a catastrophe strikes, almost ending in the death of the expedition. Unexpectedly, the brig runs into pitfalls. First he hits the bow, then the stern. The blows follow one after the other. The rudder was knocked out, the stern was damaged. Fragments of a keel float on the surface of the sea. The ship is terribly cracking, and it seems that it is about to shatter into pieces. Litke orders to cut down the mast. The axes have already been raised, but at this time a huge wave lifts the brig and it is removed from the stones.

Although the expedition escaped destruction, its position was extremely dangerous. A strong wind blew and made a big wave. Night was approaching, and the ship, having lost its rudder, was unable to steer. Thanks to the dedication and ingenuity of the team, the steering wheel was hung. But he kept himself very unreliable, and Litke decided to abandon the continuation of work. The brig headed for Arkhangelsk.

At the end of August, the brig Novaya Zemlya entered the mouth of the Northern Dvina and anchored in Solombala. The ship was pulled ashore for inspection. It turned out that the damage was very serious: the iron fastenings in the stern were bent, the copper sheathing was broken, and almost nothing was left of the keel.

In St. Petersburg, they were very satisfied with the results of Litke's work and decided in 1824 to expand research in the north on a larger scale. Two new detachments were attached to the expedition: one of them, under the command of navigator Ivanov, was ordered to complete the description of the Pechora River, the other, under the command of Lieutenant Demidov, had the task of measuring depths in the White Sea.

Litka himself was asked to repeat his attempt to reach the northern tip of Novaya Zemlya and make an attempt to the north between these islands and Spitsbergen in order to search for unknown lands. This year the ice conditions turned out to be more difficult than in previous voyages. Litke was unable to rise north of Cape Nassau. Encountering here the edge of dense ice, he headed along it to the west, hoping to find a passage to the north. But soon the expedition was convinced that such a passage did not exist. The brig headed for Vaygach Island. An attempt by Litke to penetrate into the Kara Sea was not successful: the eastern mouth of the Kara Gate Strait turned out to be clogged with ice. Fulfilling the instructions, he went to the island of Kolguev and the Kaninsky coast and, having carried out research work there, returned to Arkhangelsk.

Litke was depressed by the failure of his fourth voyage. He wrote to Krusenstern:

“Verily, it rarely happens in any enterprise that everything is arranged to such an extent in spite of the beginners. From the very beginning, opposing, strong winds delayed us so much that we had to use a whole month to complete the work that could easily be completed in a week, I mean, the definition of various points of the White Sea prescribed by the department. Turning to the north after that, on a three-week painful, and partly dangerous voyage, we only learned that even now, like in the days of Captain Wood, there can exist ice continent across the entire sea between Novaya Zemlya and Svalbard. We had no more luck in the south. At first they found that the entire southern coast of Novaya Zemlya was surrounded by solid ice for a long distance, but when it was broken by a storm from the west and we reached Vaigach Island without hindrance, we began to hope that finally our efforts would be more successful, but we were mistaken, strong westerly winds could not to drive away ice from the very, so to speak, threshold of the Kara Sea, why it was possible to judge their number in the eastern and northern parts of it! Forced to finally leave the shores of Novaya Zemlya, I wanted at least to do something near Kolguev Island and Kaninskaya land, but, having cruised here until the end of August, I had to take the return trip to the city of Arkhangelsk with equally little success. ... We did everything in our power to bring success to our cause, but against physical obstacles, human efforts very often mean nothing.

On the same day, he sent a letter to Golovnin stating that his fourth voyage "had even less success" than the voyage in 1821.

The teacher reproached his student for being too strict with himself.

“According to my thoughts,” wrote Golovnin to Litke, “you are needlessly worried that the authorities might have reason to be dissatisfied with you for failure in such an enterprise, the success of which depends more on chance than on art and enterprise. At least that’s how I judge, it’s not always possible to cross the Neva, and you can’t swim on the ice.

As a result of four voyages, Litka managed to explore and reliably map a significant part of the western shores of Novaya Zemlya, which until that time were “signified in the most guesswork way.” According to the famous German traveler Adolf Ermann, “he so surpassed all his predecessors in scientific thoroughness and impartiality of his judgments that these works cannot be passed in silence either in the history of navigation or in the history of geography.”

Russian scientists compared the "Fourfold Journey" with Humboldt's "Pictures of Nature", seeing in this work Litke an invaluable contribution to science.

In addition to Litke, interesting remarks about Novaya Zemlya were made by one of his sailing companions, Nikolai Irinarkhovich Zavalishin, brother of the famous Decembrist Dmitry Zavalishin. He was gifted with the talent of a naturalist, which he first announced in the article "The latest news about Novaya Zemlya", published in the "Northern Archive" for 1824. He gave the first in Russian literature a deep and surprisingly vivid description of the nature of Novaya Zemlya, its climate, and expressed the bold idea that to the northeast and east of this island there should be lands still unknown to man.

“Overview of the Kara Sea,” Zavalishin wrote, “in all its vastness would be no less entertaining ...

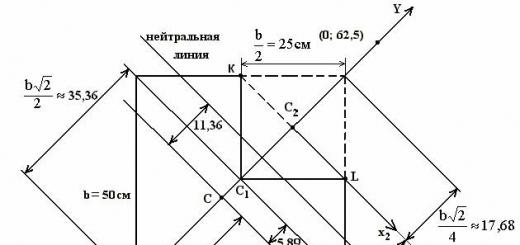

Navigation map of Litke, Pakhtusov and Baer.

I even dare to think whether there is a long chain of islands to the northeast from Cape Zhelaniya, which constitute the continuation of the chain of the Novaya Zemlya Mountains, and whether it extends to Kotelny Island ... ".

This bold guess about chains of islands in the Kara Sea was confirmed by brilliant discoveries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

After the end of the expedition, Litke asked N. Zavalishin to write notes about Novaya Zemlya. The researcher fulfilled this order. In 1830, he presented the manuscript of his book to the authorities of the naval headquarters. Prince Menshikov, who expelled science from navy, ordered to send the manuscript to the Scientific Committee, where it disappeared without a trace. Of course, the fact that Zavalishin was the brother of a state criminal sentenced to hard labor played a significant role in this.

Nikolai Chizhov, who participated in the voyage of 1821, devoted two articles to the nature and history of the exploration of Novaya Zemlya. He wrote in them about the need to revive the Novaya Zemlya and Svalbard industries, which had almost ceased recently. Unlike Andrei Lazarev, he believed that Novaya Zemlya and the waters surrounding it hold wealth that could lead to a revival of the economic life of the European North. Indeed, after the voyages of Litke, the Pomors again rush to Novaya Zemlya. It is known that in the thirties more than 130 ships sailed to this island annually.

Litke spent all of 1825 and part of 1826 in St. Petersburg. He and his friend Ferdinand Petrovich Wrangel often visited the Bestuzhevs' house, where heated literary, political and scientific disputes took place.

Title page of F. P. Litke's book "Four-fold Journey to the Arctic Ocean" with the author's dedication.

And in 1826, his dream of a new round-the-world voyage came true. He was appointed (again at the insistence of Golovnin) commander of the Senyavin sloop. He was supposed to deliver the cargo to Unalaska, and then take up the inventory of the northeastern coast of Russia. In particular, he had to explore all the bays of the "Land of the Chukchi and Koryaks", the Anadyr Sea and the Olyutorsky Bay, which had not been explored since Bering's voyage.

F. P. Wrangel.

Published for the first time From the collection of the Central Naval Museum.

He begged to give Nikolai Zavalishin as a companion. He sought to appoint his brother Alexander, but he was refused "under the pretext that he was involved with the crew in the story of December 14."

On June 11, 1827, the sloop Senyavin arrived in the inner harbor of Novo-Arkhangelsk. After handing over the cargo and repairing the damage, the travelers headed for Kamchatka, making an inventory of the Aleutian Islands along the way. In the winter of 1827/28, the expedition sailed in the tropical zone of the Pacific Ocean, studying the Caroline Archipelago.

Litka was to devote the summer of 1828 to exploring the shores of Kamchatka and Chukotka. First of all, he examined the island of Karaginsky. Near it, according to local residents, there was a harbor, to the shore of which whales allegedly approached. If it turned out to be suitable for laying the ship, then Litke could stay here until late autumn and explore the coast of Kamchatka.

“Clouds of mosquitoes made this work unusually difficult,” he wrote about the inventory of the island. - During astronomical observations, two people had to constantly whip branches over their faces and hands, and magnetic observations it was impossible to produce otherwise than by lighting a fire in a tent from brushwood and peat, the acrid smoke of which drove out not only mosquitoes, but often the observer himself: I recalled the suffering of Humboldt on the banks of the Orinoco.

The dimensions of Karaginsky Island turned out to be much larger than could be concluded from previous maps. The harbor that Litke was interested in was found, but it turned out to be shallow and could not serve as a shelter for his sloop.

Having explored the small island of Verkhoturovsky, where a kind of reserve for silver foxes was set up by local residents, the expedition headed for the Bering Strait. On July 14, the sailors reached Cape Vostochny (Dezhnev) and astronomically determined its coordinates. Litke was concerned that the mainmast had been damaged in a recent storm. Therefore, he decided to go to St. Lawrence Bay, where he also hoped to compare chronometers (according to the previous inventories of Kotzebue and Shishmarev) and perform magnetic observations. The Chukchi greeted the travelers very hospitably. He patted one of the inhabitants of Litke on the cheek as a sign of friendship and "in response received such a slap in the face, from which he almost fell off his feet."

“Recovering from surprise,” Fedor Petrovich recalled, “I see a Chukchi with a smiling face in front of me, expressing the complacency of a man who successfully showed his dexterity and friendliness, he also wanted to pat me, but with a hand that was used to patting some deer.”

The expedition made its next stop in the Mechigmen Bay, where they discovered the island of Arakamchechen. Travelers not only described it, but also visited the high mountain Aphos, from the top of which a view of the Bering Strait with islands and the majestic Vostochny Cape opened. Wrapped in a faint mist, it seemed like a mysterious medieval castle, jealously guarding the entrance to the Arctic Ocean.

The Senyavin Strait, Ittygran Island, Ratmanov and Glazenap Bays, Pekengey, Postels and Elpingin Mountains, Ledyanaya and Aboleshev Bays, Mertens and Chaplin Capes were put on the map.

Fishing in Kamchatka.

Meeting with the Chukchi.

The inventory is kept by Litke's companions, and he himself, together with the scientists Martens and Postels, travels around the environs of the Mechigmenskaya Bay, all the time communicating with the Chukchi, studying their life, customs and rituals. Meetings are warm and relaxed. The atmosphere of friendship and trust surrounds the sailors during the entire voyage off the coast of Chukotka. Litke does not find any traces of "ferocity" and "ruthlessness", about which travelers of the 18th century wrote a lot. Like his recent predecessors Kotzebue and Shishmarev, he sees the Chukchi as equal people, respects their human dignity and rejoices when he sees medals on the chest of many Chukchi, which were distributed to them by the sailors of the "Good-meaning", who came to these places to buy deer. The Chukchi, according to Litke, wear these medals so often that "the images on many of them have almost completely smoothed out." They told him: "We have nothing to fear from you, we have one sun, and you have nothing to harm us."

When travelers leave the Senyavin Strait, which separates the island of Arakamchechen from the mainland, the slopes of the mountains are covered with the first snow. But although the weather deteriorated sharply, for a whole month Litke was still exploring Chukotka, the northern shores of the Anadyr "sea" and the Gulf of the Cross. Only some of these places were visited a hundred years ago by Vitus Bering during his first voyage, and since then they have not been seen, and if they were seen, then from afar. The sailors correct the old maps and draw new points: Cape Century, in honor of Bering's first expedition, Cape Navarin, in honor of the famous naval battle, Cape Chirikov, in honor of Bering's assistant ...

On August 18, a blizzard falls on travelers. Wet snow dresses the ship in a fantastic dress. Then frost strikes, and ice freezes on the yards and topmasts.

“Protected by the shore, we stood calmly,” recalled Litke, “but in inaction, all the more boring because we were surrounded by the dullest picture in the world: occasionally bare, snow-covered cliffs appeared in front of us; behind the stern - a cat, also under the snow, washed by huge breakers ... This time proved to us that autumn is much closer here than we expected.

In order to quickly complete the inventory of the Gulf of the Cross, which was much larger than first thought, Litke divided the expedition into two detachments, which completed the work on September 5, 1828. Storms and blizzards fell to the lot of sailors, their lives were in danger more than once. Bad weather bothered the Chukchi. One of the shamans tried to speak to the raging elements. But the wind picked up even more. It seemed to Litka that he would carry the yurts into the sea along with their inhabitants, among whom, while doing pendulum observations, he spent more than a week.

In the Caroline Islands.

September 7, 1828 the sloop "Senyavin" left the parking lot in the Gulf of the Cross. Storms swooped in almost every day, driving the rolled ship farther and farther from the northern regions of Russia, the study of which was continued by Litke, which many researchers forget to mention.

On the other hand, some of them reproach him for losing interest in the North, for the fact that, through his fault, the notion of extremely difficult ice conditions in the Kara Sea has taken root in science, which even supposedly delayed "the practical resolution of the issue of the Northern Sea Route to Western Siberia."

But let's get to the facts. In the Central State Archive of Ancient Acts, where the bulk of the Litke archive is located, there are documents (correspondence with M.F. Reinecke and P.I. Klokov), from which it appears that Litke and Reinecke, his younger comrade, who continued to seas, were the organizers of the Northern Expedition of 1832, which consisted of two detachments: one was to explore the eastern coast of Novaya Zemlya, the second was to sail from Arkhangelsk to the mouth of the Yenisei by the same Kara Sea, which Litke supposedly considered always clogged with ice ... But on the pages In his "Fourfold Journey to the Arctic Ocean" he says something quite different.

Although his own attempts to penetrate the Kara Sea were unsuccessful, he believed that "several unsuccessful voyages can by no means serve as proof of the everlasting ice cover of the sea."

He analyzed previous voyages and made sure that in different years the ice coverage of the Kara Sea was different: in some years, travelers sailed on clear water, in others they encountered a lot of ice.

“The reason for this amazing difference is that,” wrote Litke, “that the amount of ice in any place depends not so much on its geographical latitude or average temperature of the year, but on the combination of many circumstances that we consider accidental, on a greater or lesser degree of cold, who reigned in the winter or spring months; from the greater or lesser severity of the winds that stood in these different seasons, from their direction and even from the sequence of the order in which they passed from one direction to another, and, finally, from the combined effect of all these causes.

Thus, almost a century and a half ago, Litke brilliantly formulated the idea of the influence of numerous natural phenomena on the ice coverage of the Arctic seas, the study of which is successfully continued by Soviet scientists. This idea contributed to the development of scientific ideas about the Arctic Ocean and in no way could adversely affect the study of the western section of the Northern Sea Route, especially since the only attempt to navigate the Kara Sea in the first half of the 19th century was organized with the participation of Litke.

On August 1, 1832, the Yenisei schooner, under the command of Lieutenant Krotov, left Arkhangelsk and headed for Matochkin Shar in order to further head to the mouth of the Yenisei. And it’s not Litke’s fault that this expedition disappeared without a trace, especially since the second detachment of the expedition under the command of Pakhtusov successfully completed its research, describing the eastern coast of the Southern Island of Novaya Zemlya, having traveled several hundred miles along the same Kara Sea. And finally, Litke's Novaya Zemlya expeditions served as an impetus for the activation of fisheries in the waters of this island, which, in turn, was a kind of preparatory step for sailing along the Kara Sea ... The delay in the practical development of the western section of the Northern Sea Route was caused not by someone's delusions, but deep economic and political reasons. As for Litke, he rendered more than one service to Russia in the exploration of the North. He chose to continue research in Lapland and the White Sea, Mikhail Frantsevich Reinecke, "this most worthy and capable worker of science."

The following essay of this book is devoted to his life and wanderings.

September 20, 1934 ice cutter “F. Litke returned to Murmansk, passing through the Northern Sea Route in one navigation. The famous steamship worked hard exploring the Arctic, like its namesake, Admiral...

September 20, 1934 ice cutter “F. Litke returned to Murmansk, passing through the Northern Sea Route in one navigation. The famous steamship worked hard exploring the Arctic, like its namesake, Admiral and scientist Fyodor Petrovich Litke.

Ice cutter "F. Litke" in Arkhangelsk, 1936.

In 1955, Soviet polar explorers set a world record. For the first time in the history of navigation, a surface vessel reached the coordinates of 83°21′ north latitude, 440 miles short of the North Pole. He remained unbeaten for many years - subsequently, such a campaign was only possible for icebreakers equipped with a nuclear power plant. The honor to set this record was awarded to the Litke ice cutter, a ship that served in the Russian and then Soviet fleet for more than 40 years. Although the Litke ice cutter is somewhat in the shadow of its older and more powerful counterpart in polar navigation, the Makarovsky Yermak, it worked hard for the needs of the vast Arctic economy, having survived three wars, many difficult polar expeditions and posting caravans.

Without exaggeration, this well-deserved ship was named after a man who devoted almost his entire life to the study of the seas and oceans, including the Arctic. Fedor Petrovich von Litke - an admiral, scientist and researcher - did a lot to ensure that the white spots framing Russian empire in the North, has become much less. The name of this outstanding navigator, the founder of the Russian Geographical Society, was named in 1921 by a Canadian-built icebreaker, which had been the "III International" for several months, and even earlier - "Canada".

Estonian roots

The ancestors of Fyodor Petrovich Litke, Estonian Germans, came to Russia in the first half of the 18th century. The grandfather of the future admiral Johann Philipp Litke, being a Lutheran pastor and learned theologian, arrived in St. Petersburg around 1735. He entered the position of director at the academic gymnasium, where, according to the contract, he had to work for 6 years. Johann Litke, along with very outstanding mental abilities, had a rather quarrelsome character, which caused conflicts with colleagues. Soon he had to leave his job and go to Sweden.

However, Russia still remained for him a convenient place to live and work, and in 1744 the theologian returned back to Moscow. His authority as a clergyman and scientist remains high, so Johann Litke is elected pastor in the new German community in Moscow. Interestingly, Johann Litke kept an academic school where he studied German none other than the young Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin. Johann Philipp lived in Russia for quite a long life and died in 1771 from the plague in Kaluga. Ivan Filippovich Litke, as he was called in the Russian manner, had a large family: four sons and a daughter. The father of the famous navigator and founder of the geographical society was the second son, Peter Ivanovich, who was born in 1750.

Like many children of foreigners, he is already completely Russified. Peter Litke received a decent education and in his younger years preferred a military uniform to a mantle of a scientist. He took part in Russian-Turkish war 1768-1774, where he distinguished himself in the battles of Larga and Cahule. Pyotr Ivanovich Litka happened to serve as an adjutant to Prince Nikolai Vasilyevich Repnin, a figure of impressive influence in the reign of Empress Catherine II. Subsequently, he happened to serve as a manager in numerous princely estates, then he moved to the Customs Department, holding quite significant positions there. Peter Litke died in 1808, being a member of the College of Commerce.

Like his father, Peter Ivanovich Litke also had numerous offspring, consisting of five children. The youngest of them was the son Fyodor Petrovich, who was born in 1797. Anna Ivanovna von Litke, nee Engel, the wife of Peter Ivanovich, died two hours after giving birth. Being still not at all an old widower and having five children in his arms, the baron expectedly decided to marry a second time. The attitude towards the offspring from the first marriage of the young wife, who added three more children, was very severe, therefore, when Fedor was seven years old, he was sent to study at a private boarding school of a certain Mayer. The quality of education and upbringing in this institution left much to be desired, and it is not known how the fate and interests of Fyodor Litke would have developed if he had not been taken away from the boarding school. His father died, and his stepmother, after the death of her husband, refused to pay for her stepson's education.

The boy was barely ten years old when his mother's brother Fyodor Ivanovich Engel took him home. Uncle was a high-ranking official, a member State Council and director of the Department of Polish Affairs. He was the owner of an impressive fortune and led an active social life, in which there was never enough time for a nephew taken into the house. The property of Fyodor Ivanovich Engel, among other things, was a decent library for those times. The books there were collected in in large numbers, but rather haphazardly. Fyodor Litke, being in early years an inquisitive personality, did not deny himself the pleasure of reading everything that came to hand. And not always, as the admiral himself later noted, what was read was of useful content.

So, actually left to himself, the boy lived in his uncle's house for two years. In 1810, his older sister Natalya Petrovna von Litke married Captain 2nd Rank Ivan Savvich Sulmenev and took her younger brother into her house. Only here Fedor finally felt himself in the family circle. In his sister's house, he could often see naval officers, listen to conversations on maritime topics, which gradually fascinated him more and more.

Perhaps close communication with the sister's husband largely determined the future life path future admiral. In 1812, when the Patriotic War began, a detachment of gunboats under the command of Sulmenev was on the roadstead of Sveaborg. His wife came to him, taking with her her younger brother. Having long noticed that the young man was “sick” by the sea, Sulmenev decided to develop this useful thrust from his young brother-in-law. At first, he hired teachers for him in various sciences, and then took him into the detachment as a midshipman. Fyodor Litke became a sailor and remained true to his choice for the rest of his life.

Sailor

Already in the next 1813, the newly minted midshipman distinguished himself at the siege of Danzig during the foreign campaign of the Russian army, serving on the biscuit (sailing and rowing vessel of small displacement) "Aglaya". For his courage and self-control, Litke was awarded the order St. Anne 4 degrees and promoted to midshipman.

Fyodor Petrovich Litke, 1829

End of an era Napoleonic Wars, and Litke's naval service continued. To a young man the Baltic was already small - it was drawn to the wide expanses of the ocean. And soon he got the opportunity to meet them not only on the pages of books and atlases. Ivan Savvich Sulmenev, having learned that Captain 2nd Rank Vasily Golovnin, famous in the then naval circles, was preparing to depart for a round-the-world expedition on the sloop Kamchatka, recommended Fedor to him.

Golovnin was known for his voyage on the sloop "Diana", which took place in very difficult international conditions. Recent allies, Russia and England, after the conclusion of the Treaty of Tilsit by Alexander I with Napoleonic France, were actually in a state of war. "Diana", having arrived in South Africa, turned out to be an interned British squadron based in local waters. Golovnin managed to deceive his guards, and the sloop escaped safely. Subsequently, circumstances developed in such a way that Vasily Golovnin had a chance to spend almost two years in Japanese captivity. This outstanding officer described all his many adventures in the Notes, which were very popular. It was a great honor to be under the command of such an illustrious officer, and Fyodor Litke did not miss his chance to get on the expedition.

Round-the-world expeditions have not yet become commonplace in the Russian fleet, and each of them was an outstanding event. On August 26, 1817, the sloop Kamchatka set off on its two-year voyage. He crossed the Atlantic, rounded Cape Horn and, having overcome the water expanses of the Pacific Ocean, arrived in Kamchatka. After giving the crew a short rest, Golovnin continued to carry out the assigned task. "Kamchatka" visited Russian America, visited the Hawaiian, Moluccas and Mariana Islands. Then, after passing Indian Ocean reached the Cape of Good Hope. Next was the already familiar Atlantic. On September 5, 1819, two years later, the Kamchatka sloop returned safely to Kronstadt.

Such a long expedition had a tremendous impact on the formation of Fyodor Litke as a sailor. On Kamchatka, he held the responsible position of head of the hydrographic expedition. The young man had to deal with various measurements and research. During a long voyage, Litke intensively filled in the gaps in his own education: he studied English language and other sciences. He returned to Kronstadt from the expedition already as a lieutenant of the fleet.

A curious detail was the fact that during his trip around the world he met and became friends for life with Ferdinand Wrangel, an equally outstanding Russian navigator. Wrangel, having made another trip around the world, would rise to the rank of admiral, become the ruler of Russian America in 1830–1835, and devote a lot of time to exploring the coast of Siberia.

Vasily Golovnin was pleased with his subordinate and gave him a brilliant recommendation, in which he described Fyodor Litke as an excellent sailor, a diligent and disciplined officer and a reliable comrade. Thanks to the opinion of an authoritative sailor and outstanding personal qualities, Lieutenant Fyodor Litke received a responsible task in 1821: to lead an expedition to Novaya Zemlya, little explored at that time. He was then 24 years old.

Arctic explorer

Novaya Zemlya, despite the fact that it was known to Russian Pomors and Novgorod merchants in ancient times, has not yet been subjected to serious and systematic research. In 1553, this land was observed from the sides of their ships by the sailors of the tragically ended English expedition under the command of Hugh Willoughby. In 1596, the famous Dutch navigator Willem Barents, in an attempt to find the Northern Passage to the rich countries of the east, rounded the northern tip of Novaya Zemlya and wintered in the most difficult conditions on its eastern coast.

For many years, Russia itself did not get around to exploring this polar archipelago. Only in the reign of Catherine II, in 1768-1769, the expedition of the navigator Fyodor Rozmyslov compiled the first description of Novaya Zemlya, having received a lot of reliable information, supplemented by information from the local population. However, to early XIX century, this region was still little explored. There was no exact map of the coasts of Novaya Zemlya. To correct this omission, in 1819 an expedition was sent there under the command of Lieutenant Andrey Petrovich Lazarev, brother of MP Lazarev, the discoverer of Antarctica, Admiral and Chief Commander of the Black Sea Fleet. The tasks assigned to Lieutenant Lazarev were very extensive, while very limited time frames were set for their implementation. It was required to survey Novaya Zemlya and Vaygach Island in just one summer. Lazarev's mission ended in failure: most of the crew of his ship, upon returning to Arkhangelsk, were sick with scurvy, and three died during the voyage.

On September 28 (September 17, old style), 1797, Fyodor Petrovich Litke was born in St. Petersburg. Admiral, count - not by inheritance, but by merit. Navigator, geographer, politician. The man who proposed the idea of creating the Russian Geographical Society and largely determined its appearance.

Fyodor Petrovich is the first count in the Litke family. He received the title in 1866 "for long-term service, especially important assignments and scientific works that have gained European fame."

It was Fyodor Petrovich who instilled a love for navigation and geographical science in his pupil - Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich, son of Nicholas I and younger brother of Alexander ΙΙ. And without him, would the project of the Geographic and Statistical Society, created by a group of the best scientists and thinkers of the country, be highly approved?

Our fatherland, extending in longitude more than a semicircle of the Earth, is in itself a special part of the world with all the differences in climates, phenomena of organic nature, etc., inherent in such a huge stretch, and such completely special conditions indicate directly that the main subject of the Russian geographical Society should be cultivation of the geography of Russia.

(F.P. Litke, speech at the first meeting of the Council of the Russian Geographical Society, 1845)

When Konstantin Nikolaevich becomes chairman of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society (IRGO), his assistant, then vice-president - that is, the actual head of the Society - will be Litke. In this post, the navigator will receive both the admiral's rank, and the count's title, and the post of president of the Academy of Sciences.

But at first it was difficult - without a mother, and then without a father - childhood, in which only numerous books were an outlet. And youth dedicated to the sea: Fyodor Petrovich's elder friend and mentor was his sister's husband, captain (and then admiral) Ivan Sulmenev. It was Sulmenev who arranged for his nephew, who had already served (and was awarded the St. George Cross) under his command, to circumnavigate the world on the sloop Kamchatka.

The voyage lasted two years - from August 1817 to September 1819. The travelers crossed the Atlantic, rounded Cape Horn, walked along the entire coast of both Americas, reached Kamchatka and from there, across the Indian Ocean, around Africa, returned to Kronstadt. Fyodor Litke was responsible for hydrographic surveys on this expedition and returned home like a real sea dog. Note - and a fiery patriot.

Who would have thought that the first ship that we met upon leaving Rio Janeiro was Russian; so that in the southern reaches of the world they see their compatriots, hear their native language! I don’t know if Columbus was more happy when he found New World how we rejoiced at this meeting!

(from the diary of F.P. Litke during his voyage on the sloop "Kamchatka")

And then there was the North - from 1821 to 1824, on the sixteen-gun brig "Novaya Zemlya" Fyodor Litke explores the White Sea, Novaya Zemlya and the adjacent regions of the Arctic Ocean. It is here that Fyodor Petrovich gains fame not only as a navigator, but also as a serious scientist - the book "Four-fold trip to the Arctic Ocean on the Novaya Zemlya military brig" was published in 1828 and brought fame to Litka.

The patriotism of the traveler is also changing: the place of ardent youthful enthusiasm is occupied by fundamental evidence. In his writings, Litke convincingly proves the priority of the Russians in the development of the Arctic.

But to what time should the beginning of Russian navigation on the Northern Ocean be attributed? When exactly did Novaya Zemlya become known to them? - questions that are likely to remain forever unresolved, and for very natural reasons. Even today we cannot boast of the multitude of writers who have devoted themselves to the commendable work of passing on to posterity certain deeds and exploits of their compatriots. Could they exist in the unenlightened centuries preceding the 16th, when the art of writing was still known to a few? The history of the first attempts of the Russians in the Arctic Sea and the gradual discoveries of all the places washed by it would, of course, present no less surprise and curiosity than a similar history of the Normans; but all this is hidden from us by an impenetrable veil of obscurity.

(F.P. Litke, "Four trips to the Arctic Ocean on the military brig Novaya Zemlya")

The next voyage is even more ambitious: Litke leads a trip around the world on the sloop "Senyavin" lasting three years (1826 - 1829). The Bering Sea was explored and previously unknown islands were discovered, the coasts of Kamchatka were studied. Fyodor Petrovich returns from the voyage famous - the sloop is greeted in Kronstadt with a cannon salute - in the same year he receives the extraordinary rank of captain of the 1st rank and becomes a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences.

Shortly thereafter, in 1832, the 16-year history of his mentorship begins. Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich was only five years old when his father determined his fate - to be a sailor in command of the Russian fleet. With this sight, the most learned of the navigators was chosen as a teacher - in deed, and in word, who proved his devotion to the country.

It was during these years, together with friends and like-minded people - Ferdinand Wrangel, Karl Baer, Konstantin Arseniev - Litke thinks about creating a geographical and statistical society in Russia on the model of those that already existed at that time in Great Britain and France. In 1845, the highest permission was received: the Russian Geographical Society was created, five years later it acquired the status of the Imperial Society.

The main goal of the Russian Geographical Society in its first Charter was recognized as "the collection and dissemination of geographical information in general and, in particular, about Russia, as well as the dissemination of reliable information about our fatherland in other lands."

Further in the life of Fyodor Petrovich Litke were the successful defense of the Gulf of Finland in the Crimean War, and the governor-general in Revel (now Tallinn), and the leadership of the Academy of Sciences. The Geographical Society remained, however, the navigator's favorite brainchild: if only Litke was in St. Petersburg, he delved into projects for new research and travel, fussed about allocating funds and publishing scientific papers.

When in 1873 the IRGS saw Fyodor Petrovich off to rest, his colleagues prepared him an "eternal" gift - the honorary gold medal of the Society was named after Litke, which is still awarded for "new and important geographical discoveries in the oceans and polar countries".

Fedor Petrovich lived a long century, leaving our world only in 1882. Having raised two sons, one of them is also a traveler and a naval officer. Unfortunately, Konstantin Fedorovich Litke outlived his father by only 10 years. But another child of the great navigator - the Russian Geographical Society - turned out to be really durable and has been living for more than 170 years. So, his labors were not in vain.

“In the genealogy of Litke, one can notice only one moral trait that passes through three generations: an irresistible inclination towards mental activity and the sciences ... Also, to a certain extent, Count Litke's love for the sea and his desire for naval service can be considered inherited. In everything else, he owes himself to himself, the energy of his personal efforts and his innate talents.

V. P. Bezobrazov, Academician

On September 17 (28), 1797, the Russian navigator and geographer, Arctic explorer, Admiral, Count Fyodor Petrovich Litke was born in St. Petersburg.

Fedor Petrovich's childhood was difficult: his mother died at his birth, his father soon married a young woman who disliked her stepsons and stepdaughters. At the age of seven, Fedor was sent to the boarding school of the German Meyer. In 1808 Litke's father died, and Fyodor was taken in by his uncle Engel. The boy was left without any supervision, did not have a single teacher from 11 to 15 years old. Independently read many books on history, astronomy, philosophy, geography.

In 1810, Fyodor Petrovich's sister, Natalya, married naval officer I.S. Sulmenev, who fell in love with Fyodor like his own son. The boy listened with enthusiasm to stories about travel around the world, geographical discoveries and victories of the Russian navy.

In 1812, at the request of Sulmenev, Fyodor Litke was accepted as a volunteer in the rowing flotilla, and soon promoted to midshipmen. In 1813, Litke took part in battles against the French units hiding in Danzig three times. For resourcefulness and courage in a combat situation, a sixteen-year-old youth was promoted to midshipman and awarded the Order of St. Anna IV degree.

Four years later, in 1817, Litke was assigned to circumnavigate the world on the military sloop Kamchatka, under the command of Captain Vasily Mikhailovich Golovnin. The voyage continued from August 26, 1817 to September 5, 1819. Litke continued to educate himself on the sloop - he studied English, made astronomical observations and calculations.

Upon returning from a voyage, Golovnin, who highly appreciated Litke's abilities, recommended him for the post of head of a hydrographic expedition to describe the shores of Novaya Zemlya. On the brig Novaya Zemlya, Litke made four trips to the Arctic Ocean in 1821, 1822, 1823 and 1824. In addition to the inventory of the shores of Novaya Zemlya, Fedor Petrovich did a lot geographical definitions places along the coast of the White Sea, the depths of the fairway and dangerous shallows of this sea have been studied in detail. A description of this expedition appeared in 1828 under the title: "Four-fold trip to the Arctic Ocean in 1821-1824." In the introduction to this book, Litke gave a historical overview of all the explorations of Novaya Zemlya and its neighboring seas and countries undertaken before him. The book brought the author fame and recognition in the scientific world.

Shortly after this expedition, Litke was appointed commander of the Senyavin sloop, which was heading for a round-the-world voyage in order to carry out a number of works in the Bering Sea and in the Caroline Archipelago. This expedition took place in 1826-1829. The expedition collected extensive geographical, hydrographic and geophysical materials. The coordinates of important points on the coast of Kamchatka north of Avacha Bay were determined, a number of islands of the Kuril chain were described, as well as the coast of Chukotka from Cape Dezhnev to Anadyr.

A large amount of geographical work was carried out in the South Pacific, where the Caroline Islands were surveyed. 12 were rediscovered and 26 groups and individual islands were described, the Bonin Islands were found, the location of which was then not known exactly. For all these geographical objects, maps were compiled, inventories and drawings were made, and a separate atlas was compiled. The expedition collected extensive material on sea currents, water and air temperature, atmospheric pressure, etc.

An important part of the work was gravimetric and magnetic observations, which served as a valuable contribution to world science. The expedition collected significant material on zoology, botany, geology, ethnography, etc.

In 1832, Litke was appointed adjutant wing, and at the end of the year he became the tutor of the five-year-old Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich. At this time, Litke proposed the need to unite all geographers, researchers and travelers in a scientific society and obtained permission to create the Russian Geographical Society, which he led for over 20 years.

During the Crimean War, Fedor Petrovich was the military governor of Kronstadt, led the successful defense of the Gulf of Finland, for which he received the rank of admiral; in 1855 he was appointed a member of the State Council, in 1864 he took the post of President of the Academy of Sciences and, in parallel, until January 17, 1873, continued to lead the Geographical Society; in 1866, Fedor Petrovich was elevated to the dignity of a count, became a knight of the highest order of Russia - St. Andrew the First-Called.

22 geographical objects in the Arctic and the Pacific Ocean were named after Litke, including a cape, a peninsula, a mountain and a bay on Novaya Zemlya, islands in the Franz Josef Land archipelago, Nordenskiöld, the strait between Kamchatka and Karaginsky Island.

On August 8 (20), 1882, one of the prominent geographers and travelers of the 19th century, admiral of the Russian fleet, Fyodor Mikhailovich Litke, died and was buried in St. Petersburg at the family plot of the Volkovsky Lutheran cemetery.

Lit .: Alekseev A. I. Fedor Petrovich Litke, Moscow, 1970; Lazarev G.E. Fedor Petrovich Litke // Geography. 2001. No. 3; Orlov B. P. Fedor Petrovich Litke: His life and work // Litke F.P. Four trips to the Arctic Ocean on the military brig "Novaya Zemlya". M.;L., 1948. S. 6-25; Fedor Petrovich Litke [Electronic resource] // Lib. ru /Classic. 2004 URL: http:// az. lib. ru/ l/ litke_ f_ p/.

See also in the Presidential Library:

Wrangel F. F. Count Fyodor Petrovich Litke. 17 Sept. 1797 - 8 Aug. 1882: [Chit. in celebrations. coll. Imp. Rus. geogr. Islands 17 Sept. 1897]. SPb., 1897

;Litke F. P. A journey around the world, made by order of Emperor Nicholas I on the military sloop Senyavin in 1826, 1827, 1828 and 1829, the fleet captain Fyodor Litke: seaworthy department with an atlas. SPb., 1835

.September 20, 1934 ice cutter “F. Litke returned to Murmansk, passing through the Northern Sea Route in one navigation. The famous steamship worked hard exploring the Arctic, like its namesake, Admiral and scientist Fyodor Petrovich Litke.

Ice cutter "F. Litke" in Arkhangelsk, 1936.

In 1955, Soviet polar explorers set a world record. For the first time in navigation, a surface vessel reached the coordinates of 83 ° 21 "North latitude, not reaching the North Pole 440 miles. It remained unbeaten for many years - subsequently, only icebreakers equipped with a nuclear power plant could do such a trip. The icebreaker Litke was honored to set this record "- a ship that has served in the ranks of the Russian, and then the Soviet fleet for more than 40 years. Although the Litke ice cutter is somewhat in the shadow of its older and more powerful counterpart in polar navigation, the Makarov Yermak, it worked hard for the needs of the vast Arctic There are a lot of farms, having survived three wars, many difficult polar expeditions and posting caravans.

Without exaggeration, this well-deserved ship was named after a man who devoted almost his entire life to the study of the seas and oceans, including the Arctic. Fyodor Petrovich von Litke - an admiral, scientist and researcher - did a lot to make the white spots framing the Russian Empire in the North much smaller. The name of this outstanding navigator, the founder of the Russian Geographical Society, was named in 1921 by a Canadian-built icebreaker, which had been the "III International" for several months, and even earlier - "Canada".

Estonian roots

The ancestors of Fyodor Petrovich Litke, Estonian Germans, came to Russia in the first half of the 18th century. The grandfather of the future admiral Johann Philipp Litke, being a Lutheran pastor and learned theologian, arrived in St. Petersburg around 1735. He entered the position of director at the academic gymnasium, where, according to the contract, he had to work for 6 years. Johann Litke, along with very outstanding mental abilities, had a rather quarrelsome character, which caused conflicts with colleagues. Soon he had to leave his job and go to Sweden.

However, Russia still remained for him a convenient place to live and work, and in 1744 the theologian returned back to Moscow. His authority as a clergyman and scientist remains high, so Johann Litke is elected pastor in the new German community in Moscow. Interestingly, Johann Litke maintained an academic school where none other than the young Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin was trained in German. Johann Philipp lived in Russia for quite a long life and died in 1771 from the plague in Kaluga. Ivan Filippovich Litke, as he was called in the Russian manner, had a large family: four sons and a daughter. The father of the famous navigator and founder of the geographical society was the second son, Peter Ivanovich, who was born in 1750.

Like many children of foreigners, he is already completely Russified. Peter Litke received a decent education and in his younger years preferred a military uniform to a mantle of a scientist. He took part in the Russian-Turkish war of 1768-1774, where he distinguished himself in the battles near Larga and Cahul. Pyotr Ivanovich Litka happened to serve as an adjutant to Prince Nikolai Vasilyevich Repnin, a figure of impressive influence in the reign of Empress Catherine II. Subsequently, he happened to serve as a manager in numerous princely estates, then he moved to the Customs Department, holding quite significant positions there. Peter Litke died in 1808, being a member of the College of Commerce.

Like his father, Peter Ivanovich Litke also had numerous offspring, consisting of five children. The youngest of them was the son Fyodor Petrovich, who was born in 1797. Anna Ivanovna von Litke, nee Engel, the wife of Peter Ivanovich, died two hours after giving birth. Being still not at all an old widower and having five children in his arms, the baron expectedly decided to marry a second time. The attitude towards the offspring from the first marriage of the young wife, who added three more children, was very severe, therefore, when Fedor was seven years old, he was sent to study at a private boarding school of a certain Mayer. The quality of education and upbringing in this institution left much to be desired, and it is not known how the fate and interests of Fyodor Litke would have developed if he had not been taken away from the boarding school. His father died, and his stepmother, after the death of her husband, refused to pay for her stepson's education.

The boy was barely ten years old when his mother's brother Fyodor Ivanovich Engel took him home. Uncle was a high-ranking official, member of the State Council and director of the Department of Polish Affairs. He was the owner of an impressive fortune and led an active social life, in which there was never enough time for a nephew taken into the house. The property of Fyodor Ivanovich Engel, among other things, was a decent library for those times. The books there were collected in large numbers, but rather haphazardly. Fyodor Litke, being an inquisitive person in his youth, did not deny himself the pleasure of reading everything that came to hand. And not always, as the admiral himself later noted, what was read was of useful content.

So, actually left to himself, the boy lived in his uncle's house for two years. In 1810, his older sister Natalya Petrovna von Litke married Captain 2nd Rank Ivan Savvich Sulmenev and took her younger brother into her house. Only here Fedor finally felt himself in the family circle. In his sister's house, he could often see naval officers, listen to conversations on maritime topics, which gradually fascinated him more and more.

Perhaps close communication with her sister's husband largely determined the further life path of the future admiral. In 1812, when the Patriotic War began, a detachment of gunboats under the command of Sulmenev was on the roadstead of Sveaborg. His wife came to him, taking with her her younger brother. Having long noticed that the young man was “sick” by the sea, Sulmenev decided to develop this useful thrust from his young brother-in-law. At first, he hired teachers for him in various sciences, and then took him into the detachment as a midshipman. Fyodor Litke became a sailor and remained true to his choice for the rest of his life.

Sailor

Already in the next 1813, the newly minted midshipman distinguished himself at the siege of Danzig during the foreign campaign of the Russian army, serving on the biscuit (sailing and rowing vessel of small displacement) "Aglaya". For his courage and self-control, Litke was awarded the Order of St. Anne, 4th class, and promoted to midshipman.

Fyodor Petrovich Litke, 1829

The era of the Napoleonic wars ended, and Litke's naval service continued. The Baltic was already small for the young man - he was drawn to the wide expanses of the ocean. And soon he got the opportunity to meet them not only on the pages of books and atlases. Ivan Savvich Sulmenev, having learned that Captain 2nd Rank Vasily Golovnin, famous in the then naval circles, was preparing to depart for a round-the-world expedition on the sloop Kamchatka, recommended Fedor to him.

Golovnin was known for his voyage on the sloop "Diana", which took place in very difficult international conditions. Recent allies, Russia and England, after the conclusion of the Treaty of Tilsit by Alexander I with Napoleonic France, were actually in a state of war. "Diana", having arrived in South Africa, turned out to be an interned British squadron based in local waters. Golovnin managed to deceive his guards, and the sloop escaped safely. Subsequently, circumstances developed in such a way that Vasily Golovnin had a chance to spend almost two years in Japanese captivity. This outstanding officer described all his many adventures in the Notes, which were very popular. It was a great honor to be under the command of such an illustrious officer, and Fyodor Litke did not miss his chance to get on the expedition.

Round-the-world expeditions have not yet become commonplace in the Russian fleet, and each of them was an outstanding event. On August 26, 1817, the sloop Kamchatka set off on its two-year voyage. He crossed the Atlantic, rounded Cape Horn and, having overcome the water expanses of the Pacific Ocean, arrived in Kamchatka. After giving the crew a short rest, Golovnin continued to carry out the assigned task. "Kamchatka" visited Russian America, visited the Hawaiian, Moluccas and Mariana Islands. Then, having passed the Indian Ocean, she reached the Cape of Good Hope. Next was the already familiar Atlantic. On September 5, 1819, two years later, the Kamchatka sloop returned safely to Kronstadt.

Such a long expedition had a tremendous impact on the formation of Fyodor Litke as a sailor. On Kamchatka, he held the responsible position of head of the hydrographic expedition. The young man had to deal with various measurements and research. During the long voyage, Litke intensively filled in the gaps in his own education: he studied English and other sciences. He returned to Kronstadt from the expedition already as a lieutenant of the fleet.

A curious detail was the fact that during his trip around the world he met and became friends for life with Ferdinand Wrangel, an equally outstanding Russian navigator. Wrangel, having made another trip around the world, would rise to the rank of admiral, become the ruler of Russian America in 1830–1835, and devote a lot of time to exploring the coast of Siberia.

Vasily Golovnin was pleased with his subordinate and gave him a brilliant recommendation, in which he described Fyodor Litke as an excellent sailor, a diligent and disciplined officer and a reliable comrade. Thanks to the opinion of an authoritative sailor and outstanding personal qualities, Lieutenant Fyodor Litke received a responsible task in 1821: to lead an expedition to Novaya Zemlya, little explored at that time. He was then 24 years old.

Arctic explorer

Novaya Zemlya, despite the fact that it was known to Russian Pomors and Novgorod merchants in ancient times, has not yet been subjected to serious and systematic research. In 1553, this land was observed from the sides of their ships by the sailors of the tragically ended English expedition under the command of Hugh Willoughby. In 1596, the famous Dutch navigator Willem Barents, in an attempt to find the Northern Passage to the rich countries of the east, rounded the northern tip of Novaya Zemlya and wintered in the most difficult conditions on its eastern coast.