7. Sometimes what is lacking in proper flank support is made up for by an intricate lunge to the rear. This is dangerous, because troops making such a detour, stuck on the line, create a jam and the enemy can cause great damage by setting his artillery at the corner of two extended lines. A powerful retreat behind the flank in dense columns, guarded to avoid attack, seems to satisfy the necessary conditions better than an intricate maneuver, but the nature of the terrain always becomes a decisive factor in choosing between the two methods. All details on this issue are given in the description of the battle near Prague (Chapter II of the Seven Years' War).

8. We must try in a defensive position not only to cover the flanks, but, as often happens, there are difficult situations in other sectors of the front, for example, such as a forced attack by the enemy on the center. Such a position will always be one of the most advantageous for defense, as was demonstrated at Malplac (1709) (at Malplac in Belgium on September 11, 1709, during the War of the Spanish Succession, a battle took place between the French army of Marshal Villars (90 thousand) and the Anglo-Austro -Dutch army of Prince Eugene of Savoy and the Duke of Marlborough (117 thousand).The French repelled all attacks of the enemy, who lost 25-30 thousand killed and wounded (French losses 14 thousand).However, Villar, himself seriously wounded, was forced to retreat, therefore it is believed that the allies won (all the more so since Villard was unable to release Mons, taken in October). Ed.) and Waterloo (1814). Large obstacles are not essential for this purpose, since the slightest difficulty on the ground is enough: for example, the insignificant river Paplot forced Ney to attack the center of Wellington's position, and not the left flank, as he was ordered.

When the defense is carried out in such a position, care must be taken to prepare for the movement of units hitherto covered by the flanks, so that they can take part in the fighting, instead of remaining idle observers.

However, one cannot fail to see that all these means are nothing but half-measures; and for an army on the defensive, it is best know how to go on the offensive at the right time, and go on the offensive. Among the satisfactory conditions for a defensive position is mentioned that which allows a free and safe withdrawal; and this brings us to the study of the question posed by the Battle of Waterloo. Would it be dangerous to withdraw an army with its rear in the woods and with good roads behind the center and each of its flanks, as Napoleon imagined, if it lost the battle? My personal opinion is that such a position would be more favorable for a retreat than a completely open field; it is impossible for a defeated army to cross the field without being exposed to great danger. Undoubtedly, if the withdrawal turns into a disorderly flight, the part of the artillery left in the battery in front of the forest will, in all probability, be lost; however, the infantry and cavalry and most of the artillery will be able to withdraw as easily as they would across the plain. Indeed, there is no better cover for a routine retreat than a forest. This assertion is made on the assumption that there are at least two good roads behind the front line, that proper withdrawal measures are taken before the enemy has the opportunity to press too close, and finally that the enemy does not manage to get in front of retreating army at the exit from the forest, as was the case at Hohenlinden (here, in Bavaria, not far from Munich, on December 3, 1800, the French Army of the Rhine Moreau (56 thousand) defeated the Austrian Danube army of Archduke John (60 thousand). - Ed.). The retreat will be safer if, as at Waterloo, the forest forms a concave line behind the center, because this re-entry will become a bridgehead, which the troops will occupy and which will give them time to proceed in a given order along the main roads.

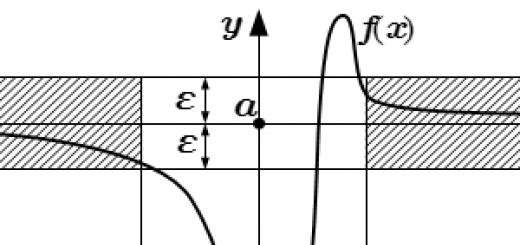

When discussing strategic operations, various possibilities were mentioned that open up two systems - defensive and offensive; and it was seen that, especially in strategy, an army that takes the initiative into its own hands has a great advantage in bringing up its troops and striking where it thinks it best to do so. At the same time, an army that operates on the defensive and expects an attack is ahead in any direction, is often taken by surprise and must always adapt to the actions of the enemy. We have also seen that in tactics these advantages are not so noticeable, because in this case the operations occupy a smaller area, and the side that takes the initiative in its hands cannot conceal its movements from the enemy, who, having reconnoitered and quickly assessed the situation, can immediately counterattack with good reserves. Moreover, the side advancing on the enemy shows him all the shortcomings of his position, arising from the difficulties of the terrain, which he must pass before reaching the enemy's front. And even if it be a flat area, there are always such uneven terrain as ravines, dense forest areas, fences, individual farm houses, villages, etc., which must either be occupied or must be passed by them. To these natural obstacles may also be added the enemy batteries, whose fire must be endured, and the disorder which always accompanies the greater or lesser extension of the troop formations, exposed to constant enemy rifle or artillery fire. Considering the issue in the light of all these factors, we agree that in tactical operations, the advantage as a result of taking the initiative into one's own hands balances on the verge of disadvantages.

However, however undoubted these truths may be, there is another, even greater manifestation of them, which was demonstrated by the greatest events of history. Every army that strictly adheres to the defensive concept must, if attacked, at least be driven out of its position. Meanwhile, using all the advantages of the defensive system and being ready to repel an attack, if one occurs, the army can count on the greatest success. A general who stays in place to meet the enemy, adhering strictly to defensive combat, may fight just as bravely, but he will have to yield to a well-placed attack. The situation is different with the general, who, of course, expects the enemy, but with the intention of attacking him at the right moment in an offensive action. He is ready to wrest from the enemy and transfer to his own troops the morale that is always present when moving forward and is doubled by the introduction of the main forces into battle at the most important moment. This is absolutely impossible if only defensive actions are strictly adhered to.

In fact, the general who takes up a well-chosen position, where his movements are free, has the advantage of watching the approach of the enemy. His forces, suitably arranged beforehand in position, supported by batteries placed so that their fire is most effective, can make the enemy pay dearly for his advance into the space between the two armies. And when the attacker, having suffered heavy losses, meets with a powerful attack at a moment when victory, it would seem, is already in his hands, in all likelihood, he will no longer have the advantage. For the morale of such a counterattack by the forces of the defending enemy, which is supposed to be almost defeated, is certainly sufficient to overwhelm the bravest troops.

Consequently, the general can use either the offensive or the defensive system with equal success in such battles. However, in the first place, far from being limited to passive defense, he must definitely know how to go on the offensive at a favorable moment. Secondly, his eye gauge must be faithful, and his composure is beyond doubt. Thirdly, he must be able to fully rely on his troops. Fourthly, in resuming the offensive, he should in no case neglect the application of the main principle that would regulate his battle schedule if he did so at the beginning of the battle. Fifth, he strikes at the decisive point. These truths are demonstrated by Napoleon's actions at Rivoli (1797) and Austerlitz (1805), as well as by Wellington at Talavera (1809), Salamanca (1812) and Waterloo (1815).

Section XXXI

Offensive battles and battle schedule

We understand by offensive battles those which an army wages by attacking another army in position. An army forced to resort to strategic defense often goes on the offensive by making an attack, and an army that meets an attack may go on the offensive in the course of the battle and gain the advantages associated with it. There are numerous examples of each of these types of battles in history. If in the previous paragraph defensive combat was discussed and the advantages of defense were pointed out, now we will move on to a discussion of offensive operations.

It must be admitted that the attacker as a whole has a moral advantage over the one who is attacked, and he almost always acts more intelligibly than the latter, who has to be in a state of greater or lesser uncertainty.

Once the decision has been made to attack the enemy, the order to attack must be given; and this is what I suppose it should be called combat schedule.

Quite often it also happens that a battle has to be started without a detailed plan, because the enemy's position is completely unknown. On the other hand, it should be well understood that on every battlefield there is a decisive point, the possession of which, more than any other, helps to secure victory, enabling him who holds it to properly apply the principles of war - therefore, preparation must be made for delivering a decisive blow on this point.

The decisive point of the battlefield is determined, as has already been pointed out, by the character of the position, the relation of the various sections of the terrain to the intended strategic goal, and, finally, by the disposition of the contending forces. For example, suppose that the enemy's flank is placed on a high ground from which access to his entire front line is open, then the occupation of this dominant high ground is tactically more important, but it may turn out that access to this position is very difficult and it is located so that which is the least important strategically. In the Battle of Bautzen (Bautzen) (here in Saxony, 8–9 (20–21) May 1813, the Russian-Prussian army of Wittgenstein (96 thousand, 636 guns) fought with the troops of Napoleon (143 thousand, 350 guns). Napoleon could not encircle and defeat the allies, who nevertheless withdrew beyond the river Lebau.The French lost 18 thousand, the allies 12 thousand, Napoleon was forced to conclude a truce (23.05 (4.06) - 29.07 (10.08) 1813), which became his big strategic mistake, because Austria and Sweden joined the anti-French coalition. Ed.) the left flank of the allies (Russians and Prussians) was located on the rather steep slopes of the low mountains of the Bohemian Forest, near the border of Austria (Bohemia was part of it), which at that time was more neutral than hostile. It seems that tactically the slope of these mountains was a decisive point in order to hold it when it was quite the opposite. The fact is that the allies had only one direction of retreat - to Reichenbach and Görlitz, and the French, putting pressure on the right flank, which was located on the plain, could cut this direction of retreat (Ney, who had a great superiority in strength, could not do this succeeded) and drive the allies into the mountains, where they could lose all military equipment and a significant part of the army personnel.

This course of action was also easier for them, taking into account the differences in the nature of the terrain, led to more important results and would reduce obstacles in the future.

The following truths may, I think, sum up what has already been said: 1) the topographic key to the battlefield is not always its tactical key; 2) the decisive point of the battlefield is definitely one that combines strategic and tactical advantages; 3) when the difficulties of the terrain do not greatly threaten the strategic point of the battlefield, then this is the most important point on the whole; 4) nevertheless it is true that the definition of this point depends very much on the disposition of the opposing forces. Thus, in overly extended and divided battle positions, the center will always be a suitable place to attack. In well-covered and interconnected positions, the center will be the strongest place, since, regardless of the reserves stationed there, it is easy to support it from the flanks - the decisive point in this case, therefore, will be one of the edges of the front line. When the numerical superiority is significant, an attack can be carried out simultaneously on both sides, but not in the case when the forces of the attackers are equal or inferior to those of the enemy. It is therefore evident that all combinations in battle consist in such application of available forces as to secure the most effective action in respect of whichever of the three points mentioned has the greatest chance of success. This point is fairly easy to determine by applying the analysis just mentioned.

The purpose of an offensive engagement can only be to drive the enemy out of position or to cut his front line, unless the strategic maneuver involves the complete destruction of his army. The enemy can be driven out either by knocking him over somewhere in his front, or by going around his flank so as to attack him from the flank and rear, or by using both of these methods at the same time, that is, by attacking him in the forehead, while one flank is covered and his front line is bypassed.

In order to achieve these various goals, it becomes necessary to select the most appropriate battle formation for the method to be used.

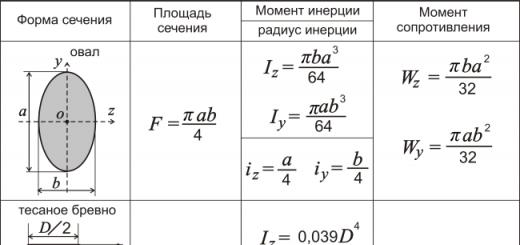

At least twelve battle formations can be listed, namely: 1) a simple linear order; 2) linear order with a defensive or offensive "hook"; 3) order with reinforced one or both flanks; 4) order with a reinforced center; 5) a simple oblique formation, or an oblique formation with a reinforced attacking wing; 6, 7) perpendicular order on one or both flanks; 8) concave order; 9) convex order;

10) echelon order on one or both flanks;

11) echelon order in the center; 12) order as a result of a powerful combined attack in the center and along the edges at the same time. (See Figure 5-16.)

Each of these formations can be used by itself or, as indicated, in connection with the maneuver of a strong column with the intention of outflanking the enemy's front line. In order to properly assess the merits of each of them, it becomes necessary to test each of these orders by applying the main principles already stated.

For example, it is quite obvious that the linear order (Fig. 5) is the worst of all, because it does not require the skill of fighting one front against another, here battalion fights against battalion with equal chances of success for each side - no tactical skill in such no battle needed.

Rice. 5

However, in one essential case this order is suitable. This occurs when the army, taking the initiative in its own hands in large strategic operations, succeeds in attacking enemy communications and, cutting off the enemy's line of retreat, at the same time covers its own. When a battle takes place between them, the army that has gone behind the other can use a linear order, because, having effectively applied a decisive maneuver before the battle, it can now direct all its efforts to frustrate the enemy's attempts to open a way for itself to withdraw . With the exception of this single case, the linear order is the worst. I do not mean to say that the battle cannot be won using this order, because one side or the other must win if the confrontation continues. Then the advantage will be on the side of the one who has the best troops who knows best when to bring them into battle, who manages his reserve better and who is more likely to be lucky.

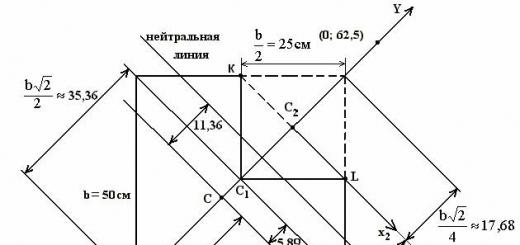

Linear formation with a hook to the flank (Fig. 6) is most often used in a defensive position. It can also be the result of an offensive combination, but the hook is directed to the front, while in the case of the defense it is directed to the rear. Battle near Prague (April 25 (May 6), 1757, here Frederick II defeated Brown's Austrians. - Ed.) is a very remarkable example of the danger to which such a hook is exposed if properly attacked.

A line formation with one flank reinforced (Fig. 7) or with a center (Fig. 8) to break through the corresponding sector of the enemy is much more favorable than the two previous ones, and even more so in accordance with the above fundamental principles. Despite this, if the opposing forces are approximately equal, then that part of the front line, which is weakened in order to strengthen its other part, will itself be threatened if it is located in one line parallel to the positions of the enemy.

Rice. 6

Rice. 7

Rice. eight

Rice. nine

Rice. ten

Rice. eleven

The oblique formation (Fig. 9) is best when weaker forces attack outnumbered troops, because in addition to the advantage of concentrating the main forces on one section of the enemy’s front line, he has two equally significant advantages. The fact is that the weakened flank is not only pulled back to avoid an attack by the enemy, but also plays a dual role, supporting the positions of the part of its front line that is not under attack, and being at hand as a reserve to support, if necessary, leading the battle. flank. This order was applied by the illustrious Epaminondas in the battles of Leuctra (371 BC) and Mantinea (in 362 BC; Epaminondas, having won the victory, was mortally wounded. - Ed.). The most brilliant example of its use in modern times was that given by Frederick II the Great at the Battle of Leuthen on November 24 (December 5), 1757. (See Chapter VII of the Treatise on the Great Operations.)

Perpendicular order on one or two flanks, as seen in fig. 10 and 11 can only be considered as a formation to indicate the direction in which the first tactical movements in battle can be made. The two armies will never long occupy the relatively perpendicular positions shown in these figures, because if Army B were to take up its first position on a line perpendicular to one or both of the edges of Army A, the latter would at once change the front of its front line. Even if army B, as soon as it reaches edge A or beyond it, must, of necessity, turn its columns either to the right or to the left in order to draw them up to the enemy’s front line and thereby bypass it, as in point C, the result become two oblique lines, as shown in Fig. 10. The conclusion is that one division of the attacking army will take up a position perpendicular to the flank of the enemy, while the rest of the army will approach him from the front in order to commit harassing actions; and this always brings us back to one of the skew orders shown in fig. 9 and 16.

An attack on both flanks, whatever the type of attack being undertaken, can be very advantageous, but only if the attacker is clearly outnumbered. For if the fundamental principle is to bring the main body up to the decisive point, the weaker army will break it by directing an attack with divided forces against the superior forces of the enemy. This truth will be clearly illustrated below.

Rice. 12

Rice. 12a

The order, concave in the center (Fig. 12), found adherents from the day when Hannibal, using it, won the battle of Cannae. This order can indeed be very good when the course of the battle itself leads to it, that is, when the enemy attacks the center, which retreats in front of him, and the enemy himself finds himself flanked. But if this order is adopted before the battle begins, the enemy, instead of rushing to the center, will need to attack only the flanks, the edges of which protrude, and they will be relatively in exactly the same situation as if they were attacked in the flank. Therefore, such an order will hardly ever be used, except against an adversary who has adopted a convex order for fighting, as will be seen later.

The army rarely forms a semicircle, preferring a broken line with a retreating center (Fig. 12a.). According to some authors, such a formation ensured the victory of the British in the days of the famous battles of Crecy (Cressy) (1346) and Agincourt (1415). This formation is, of course, better than the semi-circle, as it does not open the flanks much to attack, while at the same time allowing advance in echelon and retaining all the advantages of concentrated fire. These advantages disappear if the enemy, instead of unwisely rushing to the retreating center, is content with observation from afar and throws all his forces on one flank. Esling in 1809 is an example of the advantageous use of a convex front, but it should not be concluded that Napoleon made a mistake in attacking the centre. After all, the fighting army, behind which was the Danube and which could not move without the cover of its bridges through which communications passed, cannot be judged as if it had complete freedom of maneuver.

A convex formation with a protruding center (Fig. 13) meets the requirements of the battle immediately after the crossing of the river, when the flanks must be withdrawn and left on the river to cover the bridges, and also when the defensive battle is fought with the river located in the rear, which needs to be forced, and cover the transition, like at Leipzig (1813). Finally, this formation can become a natural formation to resist an enemy forming a concave front line. If the enemy directs his efforts to the center or to one flank, this order can lead to the defeat of the entire army.

Rice. thirteen

The French tried it at Fleurus in 1794, and it was successful, because the Prince of Coburg, instead of making a powerful attack on the center or edge, divided his attack into five or six divergent lines, and even more so in relation to two flanks at once. Almost the same convex order was adopted at Esling (Aspern) (1809) and on the second and third days of the famous battle of Leipzig. In the latter case, the result was as expected.

Rice. fourteen

The order of the echelon attack on both flanks (Fig. 14) is the same kind as the perpendicular order (Fig. 11), but better than that, because the echelons are at the closest distance from each other in the direction of where the reserve. In this case, the enemy would be less able, both due to lack of space and time, to throw forces into the gap in the center and threaten this area with a counterattack.

Rice. fifteen

The echelon formation in the center (Fig. 15) can be used especially successfully against an army that is too dispersed and stretched out, because in this case its center is somewhat isolated from the flanks and can easily be overturned. Thus, an army split in two is likely to be destroyed. But from the point of view of the same fundamental principle, this order of attack will prove less promising for success against an army with a connected and unbroken front line. Because the reserve, mostly located close to the center, and the flanks, able to act, either by concentrating their fire or moving against the forward echelons, could well repulse their attack.

If this construction to a certain extent reflects the famous triangular wedge or “pig” of the ancients and Winkelried’s column (obviously, this is Winkelried, who ensured the victory of the Swiss at the Battle of Sempach (1386): taking several enemy spears of the defending Habsburg warriors in an armful, he plunged them into his own chest and fell, and his comrades broke into the enemy line. Ed.), it also differs significantly from them. Indeed, instead of forming one dense mass, which is impractical today, given the use of artillery, it assumed a large open space in the middle, which facilitated movement. This formation is suitable, as already stated, for driving into the center of an overextended front line, and can be just as successful against an inevitably fixed line. However, if the flanks of the attacked front are brought up in time against the flanks of the advanced echelons of the attacking wedge, the consequences can be disastrous. The line formation, greatly reinforced in the center, may perhaps turn out to be a much better formation (Fig. 8, 16), because the linear front in this case would have at least the advantage of deceiving the enemy as to the place of attack and would prevent the flanks from attacking the echeloned flank center. The echelon order was adopted by Laudon to attack the Bunzelwitz camp fortified with trenches (Treatise on Great Operations, chapter XXVIII). In this case, it is quite suitable, because then it is clear that the defending army is forced to remain on its fortifications, there is no danger of its echelons attacking the flank. But this formation has the disadvantage of indicating to the enemy the place of his front which one wishes to attack, in which case a feigned attack on the flanks should be made in order to mislead him as to the true place of the attack.

Rice. sixteen

The battle order of attack in columns in relation to the center and at the same time to the edge (Fig. 16) is better than the previous order, especially in attacking a tightly united and inseparable enemy front line. It can even be called the most expedient of all battle formations. The attack of the center, with the support of the flank while enveloping the enemy from the flank, does not allow the attacked side to fall on the attacker and strike him in the flank, as was done by Hannibal and Marshal Sachs. The flank of the enemy, which is pinned down by attacks from the center and edge and forced to resist almost all the forces of the opposing side, will be routed and probably destroyed. It was this maneuver that secured Napoleon's victories at Wagram in 1809 and Ligny in 1814. He wanted to try to carry it out at Borodino, where he had only partial success due to the heroic actions of the Russian left flank and, in particular, Paskevich's division (26th Infantry) on the famous central redoubt (Raevsky's battery. - Ed.), and also because of the arrival of Baggovut's corps on the flank, which Napoleon hoped to bypass.

He also used it at Bautzen (Bautzen) in 1813, where unprecedented success could have been achieved, but due to an accident as a result of a maneuver on the left flank with the intention of cutting off the allies from the road to Wurshen (this "accident" is the heroic defense of Barclay's troops -de Tolly and Lanskoy on the right flank of the position of the allied army, which did not allow Napoleon to carry out what was planned (with the overwhelming numerical superiority of Ney's French here). Ed.) all subsequent actions were based on this fact.

It should be noted that these various orders are not to be understood exactly in the same way as the geometrical figures which reflect them. The commander who thinks that he will build his front as smoothly as on paper or on the parade ground will make a big mistake and, most likely, will be defeated. This is especially true of the battles that are being waged now. In the time of Louis XIV or Frederick II it was possible to form a front line almost as level as geometric figures. The reason is that the armies set up tent camps, almost always closely adjacent to each other, and saw each other for several days, thus giving enough time for the roads to be opened and space cleared to allow the columns to be at a measured distance from each other. . But in our day, when armies bivouack, when their distribution among several corps gives much greater mobility, when they take up position close to each other, obeying orders given to them and at the same time out of sight of the commander, when there is often no time for careful study enemy positions, and finally, when different branches of the troops are mixed on the front line, in such circumstances any battle formations are inapplicable. These figures have never been anything but an indication of the approximate alignment of forces.

If each army were a solid mass capable of moving under the influence of the will of one man, and as fast as thought, the art of winning battles would be reduced to choosing the most advantageous battle formation, and the general could rely on the success of a pre-planned maneuver. But the facts speak quite differently; the great difficulties with tactics in battles always force the unconditional simultaneous introduction into hostilities of many detachments, the efforts of which must be combined in such a way as to carry out a planned attack, since the will in the execution of the plan gives more opportunities to hope for victory. In other words, the main difficulty is to get these detachments to combine their efforts in carrying out a decisive maneuver, which, in accordance with the original plan of battle, is designed to lead to victory.

Inaccurate transmission of orders, how they will be understood and carried out by subordinates of the commander-in-chief, excessive activity among some, lack of it among others, incorrect assessment of the situation - all this can interfere with the simultaneous introduction into battle various parts not to mention unforeseen circumstances that may delay or disrupt the arrival of troops at their designated location.

From this we can deduce two undoubted truths: 1) the simpler the decisive maneuver, the greater the certainty of success; 2) unexpected maneuvers, timely made during the fighting, are more likely to lead to success than those determined in advance, unless the latter are linked to previous strategic movements that bring up columns designed to decide the outcome of the day in those places where they presence will provide the expected result. Evidence of this is Waterloo and Bautzen (Bautzen). From the moment that the Prussians of Blücher and Bülow reached the height of Fishemont at Waterloo, nothing could prevent the defeat of the French in the battle, and they only had to fight to make it not so crushing. Similarly, at Bautzen (Bautzen), as soon as Ney captured Clix (on the river Spree), only the withdrawal of the Allies on the night of May 21st could save their troops, because on the afternoon of the 21st it would have been too late. And if Ney had acted better and done what he was advised to do, a great victory would have been won.

As for maneuvers to break through the front line and calculations for the interaction of columns moving from the general front of the army, with the intention of carrying out large detour maneuvers into the enemy's flank, it can be argued that their result is always in doubt. The fact is that it depends on such exact execution of carefully drawn up plans, which is rare. This subject will be dealt with in paragraph XXXII.

In addition to the difficulties that depend on the exact application of the order of battle adopted in advance, it often happens that battles begin even without a sufficiently precise object of attack by the attacker, although a collision is quite expected. This uncertainty is the result either of the circumstances preceding the battle, the neglect of the position and plans of the enemy, or the fact that part of the army's forces are still expected to arrive on the battlefield.

From this, many conclude that it is not possible to escape to different systems of formations of battle formations, or that the adoption of any of the battle formations at all can affect the outcome of hostilities. In my opinion, this conclusion is erroneous, even in the above cases. Indeed, in battles begun according to some elaborate plan, there is a possibility that at the beginning of hostilities the armies will take up almost parallel and more or less fortified positions in some place. The side operating on the defensive, not knowing where the assault will fall on it, will keep a significant part of its forces in reserve, to be used if circumstances so require. The attacking side must make the same effort to ensure that its forces are always at hand. However, as soon as the object of attack is determined, a large mass of its troops will be directed against the center or one of the flanks of the enemy, or against both at once. Whatever the resulting construction, it will always reflect one of the figures presented above. Even in unexpected combat actions the same thing will happen, which will hopefully be sufficient proof of the fact that this classification of various systems of battle formations is neither fantastic nor useless.

There is nothing even in the Napoleonic Wars to disprove my assertion, although they can be represented less than any other as neatly laid out lines. However, we see that at Rivoli (1797), at Austerlitz (1805) and Regensburg (1809), Napoleon concentrated his forces towards the center in order to be ready to attack the enemy at an opportune moment. In the Battle of the Pyramids in Egypt in 1798, he formed an oblique square line in the echelon. Under Leipzig (1813), Esling (1809) and Brienne (1814) he applied a kind of very similar convex order (see Fig. 11). Under Wagram (1809) his order was very similar (see Fig. 16), pulling two masses of troops to the center and right edge, while at the same time pulling back the left flank. And he wanted to repeat the same thing at Borodino in 1812 and at Waterloo in 1815 (before the Prussians arrived to help Wellington). Although at Preussisch-Eylau (1807), the course of the battle was almost unpredictable, given the very unexpected return and offensive actions of the Russians. Here Napoleon flanked their left edge almost perpendicularly, while in another direction he sought to break through the center, but these attacks were not simultaneous. The attack on the center was repulsed at eleven o'clock, while Davout did not attack the Russian left flank vigorously enough until the center was attacked. At Dresden in 1813, Napoleon attacked with two flanks, perhaps for the first time in his life, because his center was covered by fortifications and a camp fortified with trenches. In addition, the attack on its left edge coincided with Vandam's attack on the direction of the enemy's withdrawal.

Under Marengo (1800), if we talk about the merit of Napoleon himself, his chosen oblique order, with the right flank located at Castelcheriole, saved him from an almost inevitable defeat. The battles of Ulm (1805) and Jena (1806) were battles won by strategy before they began, and tactics had little to do with it. At Ulm there was not even an ordinary battle.

I think that we can conclude from this that, even if it seems absurd to want to place battle formations on the ground in such regular lines with which they were indicated on the diagram, an experienced commander can nevertheless keep the above orders in mind and can place his troops in this way on the battlefield that their arrangement would be similar to one of these battle formations. He should strive in all his combinations, in an arbitrary or accepted arrangement along the way, to come to a sound conclusion regarding the key point of a particular battlefield. And this can only be done by carefully considering the direction of the enemy's battle formation and acting in the direction that the strategy requires of him. Then the general will turn his attention and efforts to that point, using a third of his strength to control the enemy or follow his movements, while at the same time throwing two-thirds of his strength on the point, the possession of which will ensure his victory. Acting in this way, he will be satisfied with all the conditions that the science of grand tactics places on him, and will apply the principles of the art of war in the most irreproachable manner. The method of determining the decisive point of the battlefield is described in the previous chapter (paragraph XIX).

After considering twelve formations of battle, it occurred to me that it would be appropriate to answer some of the statements in General Montolon's Memoirs of Napoleon. The famous military leader seems to regard the oblique order as a modern invention, an opinion which I do not at all share, because the oblique order is as old as Thebes and Sparta, and I myself have seen it used. This statement of Napoleon seems more remarkable, because Napoleon himself boasted that he used it under Marengo - the very order, the existence of which he now denies.

If we understand that the oblique order must be applied strictly and precisely, as General Rüchel suggested (crushed in 1806 near Jena. - Ed.) in the Berlin school, Napoleon was, of course, right in considering this an absurdity. But I repeat that the battle position has never been a regular geometric figure, and when such figures are used in the discussion of tactical combinations, this can only be done in order to express an idea in a certain way, using a known symbol. It is true, however, that every battle formation which is neither parallel nor perpendicular to the enemy must necessarily be oblique. If one army attacks the flank of another army, then the attacking flank is reinforced by a large mass of troops, while the weakened flank is kept drawn back, avoiding attack. The direction of the combat disposition, by necessity, must be somewhat oblique, since one end of it will be closer to the enemy than the other. The oblique formation is so far from a flight of fancy that we see that it is used in a layered battle formation on one flank (Fig. 14).

With regard to the other battle formations discussed above, it cannot be denied that at Esling (Aspern) in 1809 and Fleurus in 1794, a concave line corresponded to the general formation among the Austrians and that among the French it was convex. In these formations, parallel lines may be used in the case of straight lines, and they will be classified as belonging to a linear order of battle when neither section of the line is filled more than the other and is not closer to the enemy than the other.

Postponing for the time being further consideration of these geometric figures, it can be seen that for the purpose of conducting combat according to science, the following provisions cannot be avoided:

1. The offensive battle formation should have as its goal the expulsion of the enemy from his position by expedient means.

2. The maneuvers indicated in the art of war are those carried out with the intention of taking possession of only one flank, or the center and one flank at a time. The enemy can also be driven out by enveloping (flanking) maneuvers and bypassing his position.

3. These attempts have a high probability of success if they remain hidden from the enemy until the very last moment of the attack.

4. Attacking the center and both flanks at the same time, in the absence of a significant superiority of forces, will be completely contrary to the rules of the art of war, unless one of these attacks is very powerful, without too much weakening the front line elsewhere.

5. The oblique battle formation has no other purpose than to unite at least half of the forces of the army in an overwhelming attack on the flank of the enemy, while the rest of the forces are drawn back from the danger of attack, and are organized either in echeloned battle formation or deployed in a single oblique line.

6. Various battle formations: convex, concave, perpendicular or otherwise - they can all differ in the presence of positions of the same strength along their entire length or the concentration of troops in one place.

7. The purpose of the defense, which is to frustrate the plans of the attacking side, the organization of the corresponding defensive order should be such as to multiply the difficulties of approaching the defensive position and to keep a strong reserve at hand, well hidden and ready to fall at the decisive moment on the place where the enemy least expects this.

8. It is difficult to say with certainty what method is best used to force the enemy army to leave their positions. An impeccable order of battle will be one that combines the double advantage of firepower and the morale of an attack. A skillful combination of deployed battle formations and columns acting alternately, as circumstances require, will always be a good combination. In the practical application of this system, many variations may arise due to differences in the eye. (coup-d "oeil) commanders, the morale of officers and soldiers, their knowledge of the maneuvers carried out and the conduct of all types of fire, due to differences in the nature of the terrain, etc.

9. Since in offensive combat the main task is to dislodge the enemy from his position and cut him off as thoroughly as possible from the escape routes, the best way to accomplish this task is to concentrate as much manpower and equipment against him as possible. However, it sometimes happens that the benefit of the direct use of the main body is doubtful, and the best results can be obtained by maneuvers to envelop and bypass the flank closest to the enemy's line of retreat. He can, in the event of such a threat, retreat and fight stubbornly and successfully if attacked by the main body.

There are many examples in history of the successful implementation of such maneuvers, especially when they were used against weak generals, and although the victories achieved in this way are on the whole less significant, and the enemy army was not so much demoralized, such successful, although incomplete actions, are of no small importance. value and should not be neglected. The experienced general must know how to use the means at his disposal to achieve these victories when an opportunity arises for this; and especially he should combine envelopment and detours with the attacks of the main body.

10. A combination of these two methods - namely, an attack on the center with the main body and a flanking maneuver - will bring victory rather than using each of them separately. But in any case, too extended orders of movement should be avoided, even in the presence of an insignificant enemy.

11. The method of driving the enemy out of his position by the main forces is as follows: confusing his troops with strong and well-aimed artillery fire, intensifying his confusion with energetic cavalry actions and consolidating the advantage gained by moving forward large masses of infantry, well covered in front by arrows in the chain and cavalry from the flanks.

But while we can expect success following such an attack on the first enemy line, the second has yet to be overcome, and after that - the reserve. In this phase of hostilities, the attacking side usually encounters serious difficulties, the morale impact of defeating the enemy on the first line does not necessarily lead to his retreat from the second line, and as a result, the commander of the troops often loses his presence of mind. Indeed, the attacking troops usually advance somewhat erratically, however victoriously, and it is always very difficult to replace them with those who advance in the second echelon, because the second line usually follows the first at gunshot range. Therefore, in the heat of battle, difficulties always arise in replacing one division with another - at a time when the enemy is exerting all his strength to repel the attack.

These considerations lead to the belief that if the general and the troops of the defending army are equally active in their duty and keep their presence of mind, if there is no threat to their flanks and the direction of withdrawal, in the next phase of the battle the advantage will usually be on their side. However, in order to achieve and consolidate this result, the second echelon and the cavalry of the defenders must at the right moment be thrown against the successfully operating enemy battalions. After all, the loss of a few minutes can become an irreparable mistake, and the confusion of the first echelon that has been attacked can spread to the second echelon.

12. From the foregoing facts, the following indisputable conclusion can be drawn: "The most difficult to apply, as well as the surest of all means that an attacker can use to win, consists in the strong support of the first line by the troops of the second line, and this last - reserve. And also in the skillful use of cavalry detachments and artillery batteries to provide support in delivering a decisive blow to the enemy's second line. This is the greatest of all the problems of tactics in combat.

At this important turning point in battles, theory becomes a vague guide because it is no longer suited to the urgency of the situation and can never be compared in value to natural warfare talent. It will not be a full-fledged replacement for that intuitive, acquired in many battles. eye, which is characteristic of a commander distinguished by his courage and composure.

The simultaneous engagement of a large number of all branches of the armed forces, with the exception of a small reserve from each of them, which must always be at hand, will, therefore, at the critical moment of the battle, be a problem that every experienced general will try to solve and to which he should give his whole attention. . This critical moment usually comes when the front lines of both sides have entered the fray and the rivals are exerting all their efforts, on the one hand, to complete the matter with victory, and on the other, to take it away from the enemy. It hardly needs to be said that in order to strike the decisive blow most thoroughly and effectively, it is very advantageous to simultaneously attack the enemy's flank.

13. In defense, small arms fire can be used much more effectively than in an offensive. March to the defensive position of the enemy with simultaneous firing can be carried out only by arrows in a chain, but for the main masses of the advancing troops this is impossible.

Since the purpose of the defense is to break and confuse the attacking troops, the fire from rifles and artillery will be a natural defensive means of the first line, and if the enemy approaches too close, columns of the second line and part of the cavalry should be thrown against him. Then there will be a high probability that the attack will be repulsed.

Section XXXII

Flanking maneuvers and overextension when moving in battle

We have spoken in the previous paragraph of the maneuvers to envelop and outflank the front of the enemy on the battlefield, and of the advantages to be expected from them. It remains to say a few words about the wide detours into which these maneuvers sometimes turn, which lead to the failure of so many seemingly well-planned plans.

It can be deduced as a principle that any movement is dangerous, which is so extended as to give the enemy the opportunity, if it appears, to break the rest of the army into position. However, since the danger largely depends on the speed and decisiveness of the strike of the opposing commander with verified accuracy, as well as on the manner of fighting to which he is accustomed, it is not difficult to understand why so many maneuvers of this kind fail some commanders and succeed others. , and also why such a movement, which would be dangerous in the presence of Frederick II, Napoleon, or Wellington, could be completely successful against a general of limited ability who cannot launch an attack at the right moment, or who himself is in the habit of making movements in such a manner. It therefore seems difficult to lay down a rigid rule on the subject. The following instructions are all that can be given. Keep large masses of troops on hand and ready to act at the right moment, but be alert to avoid the danger of amassing troops in too large formations. A commander with these precautions in mind will always be ready for any eventuality. If the commander of the enemy side shows less skill and tends to be fond of extended movements, his opponent can be considered lucky.

A few examples from history will serve to convince the reader of the truth of my statements and show him how much the results of these extended movements depend on the character of the general and the armies involved in them.

AT Seven Years' War Frederick II won the Battle of Prague (1757) because the Austrians left a thinly defended gap of a thousand yards between the right flank and the rest of the army. The latter remained motionless while the right flank was attacked. This omission was all the more unusual since the Austrian left had a much shorter distance to support the right flank than Frederick, who was supposed to attack it. The fact is that the right flank of the Austrians had the shape of a hook, and Frederick had to move along the arc of a large semicircle in order to get to it. On the other hand, Frederick almost lost the Battle of Torgau (November 3, 1760) because he overstretched (almost six miles) his left flank, which was disunited in its movement, bypassing the right flank of Marshal Daun with few forces. Mollendorf drew up the right flank in a concentric movement towards the heights of Siplitz, where he joined up with the king, whose position was thus rearranged.

The Battle of Rivoli (1797) is a notable example in this regard. Everyone who is well acquainted with this battle knows that Alvintzi and his chief of staff, Weyrother, wanted to encircle Napoleon's small army, which was concentrated on the Rivoli plateau. Their center was destroyed, while the troops of their left flank massed in the ravines near the Adige, and Lusignan with his right flank made a wide detour to reach the rear of the French army, where he was immediately surrounded and taken prisoner.

No one will forget the day at Stockach in 1799, when Jourdan had the absurd idea of attacking a combined army of sixty thousand men with three small divisions of seven or eight thousand men, separated by several leagues. Meanwhile, Saint-Cyr, with a third of his army (thirteen thousand men), had to go twelve miles behind the right flank and go to the rear of this sixty thousandth army, which inevitably emerged victorious over these divided detachments, and of course with the capture of part of them in his rear. That Saint-Cyr managed to retreat was truly a miracle.

We may recall how the same General Weyrother, who wanted to encircle Napoleon at Rivoli, attempted the same maneuver in 1805 at Austerlitz, in spite of the harsh lesson he had learned. The left flank of the allied army, wishing to outflank Napoleon's right wing in order to cut it off from Vienna (where he was not eager to return), by a circular maneuver of almost six miles opened a gap of one and a half miles in his front line. Napoleon took advantage of this mistake, attacked the center and surrounded the left flank of the Russian-Austrian army, which was completely squeezed between the lakes Telnitz and Melnitz.

Wellington won the Battle of Salamanca (1812) in a maneuver very similar to that of Napoleon, because Marmont, who wanted to cut off his retreat to Portugal, opened a gap of a mile and a half in his line, seeing which the English general completely destroyed Marmont's unsupported left flank.

If Weyrother at Rivoli or Austerlitz had opposed not Napoleon but Jourdan, he could have destroyed the French army, instead of suffering a complete defeat in each case. For a general who, at Stockach, attacked a force of sixty thousand soldiers with his four military formations so scattered that they were unable to give each other mutual support, could not know how to gain sufficient advantage from the wide flanking maneuver carried out with his participation. . Similarly, Marmont was unlucky - he met an enemy at Salamanca, whose main advantage was quick to use and verified tactical eye gauge. With the Duke of York or Moore as opponents, Marmont would probably have emerged victorious.

Among the detours that have become successful in our day, the most brilliant in results were those made at Waterloo (1815) and Hohenlinden (1800). The first of these was almost entirely a strategic operation, and it was accompanied by a rare coincidence of favorable circumstances. As for Hohenlinden, we shall search in vain in military history another example of when a brigade alone ventured into the forest and found itself among the enemy’s fifty thousand troops, which did not prevent it from performing the same impressive feat as the French general Rishpans did in the Matenpoet Gorge, where, in all probability, one could expect that he will lay down his arms.

At Wagram, the corps under the command of Davout, covering the flank of the enemy, greatly contributed to the successful outcome of the day, but if the center of the Austrian troops under the command of MacDonald, Oudinot and Bernadotte did not provide timely support with an energetic attack, it is not at all necessary that a similar result would have been achieved in the end. success.

Such a multitude of contradictory results may lead to the conclusion that no rule can be deduced on the subject. However, this opinion is erroneous; it is obvious that by making it a rule to use a well-knit and well-coordinated order of battle, the general will be ready for any emergency and little is left to chance. But it is especially important for him to have a correct assessment of his opponent's character and his usual style of fighting - this will allow him to adapt his own actions to this style of fighting. In the case of superior numbers or superior discipline, maneuvers may be attempted which would be imprudent if the forces or abilities of the commanders were equal. The flank and flank maneuver should be combined with other attacks and the possibility of timely support that the rest of the army on the enemy front could try to provide, either against the flank and flank or against the center. Finally, strategic operations to cut off the enemy's line of communication before giving him battle, and an attack in his rear, the advance of an army covering his own line of retreat, are most likely to be successful and effective, and moreover, they do not require during the battle isolated maneuver.

Section XXXIII

Clash of two armies on the march

The accidental and unexpected meeting of two armies on the march gives rise to one of the most impressive episodes in the war.

In most battles, one side awaits its opponent in a pre-selected position, which is attacked after reconnaissance carried out as close to the enemy as possible and as carefully as possible. However, it often happens, especially when the war is already underway, that two armies approach each other, and each of them intends to suddenly attack the opponent. The clash follows unexpectedly for both armies, since each of them finds the other where it does not expect to meet it. One army can also be attacked by another that has prepared a surprise for it, as happened to the French at Rosbach (1757).

Accidents of this kind require from the general all his genius of an experienced commander and warrior capable of controlling events. It is always possible to win a battle with brave troops, even where the commander may not have great abilities, but victories like those won at Lützen (April 20 (May 2), 1813) Napoleon, having 150-160 thousand against 92 thousand of the Russian-Prussian army, won an inexpressive victory (losses of killed and wounded 15 thousand from Napoleon and 12 thousand from the allies).The allied army retreated under pressure from a numerically superior enemy, covering its flanks. Ed.), Luzzare (1802, where the French (Duke of Vendôme) managed to stop the Austrians. – Ed.), Preussisch-Eylau (in this battle in 1806, both sides called themselves winners. The Russians lost 26 thousand, Napoleon - 23 thousand. - Ed.), Abensberg (1809) can only be won by brilliant geniuses with great composure and using the smartest combinations.

The probability of such random battles is so great that it is not at all easy to state the exact rules corresponding to them. But this is the case when it is necessary to see clearly before one's eyes the fundamental principles of the art and the various methods of applying them in order to properly arrange a maneuver, the decision on which must be made instantly and amid the roar and clang of weapons.

Two armies, marching as usual with all their camp equipment, and suddenly meeting each other, at first can do nothing better than turn their vanguard to the right or left of the road they are passing through. In each of the armies, the forces must be concentrated in such a way that they can be thrown in a suitable direction, taking into account the purpose of the march. It would be a grave mistake to deploy the whole army behind the vanguard, because even if the deployment were made, the result would be nothing more than a badly organized parallel order. And if the enemy made a sufficiently energetic attack on the vanguard, the result could be a disorderly flight of the troops lining up (see the account of the battle of Rosbach, "Treatise on great military operations").

In the modern system, when armies move more easily, march along several roads, and are divided into groups of troops that can act independently, this disorderly flight is not to be especially feared, but the principles remain unchanged. The vanguard must always be stopped and brought into battle order, and then the bulk of the troops must concentrate in the direction that is best suited to achieve the goal of the march. Whatever maneuvers the enemy then tries to take, everyone will be on alert to meet him.

Section XXXIV

About surprises for armies

I shall not here speak of the surprises created by small detachments, which are among the main features in partisan and flying warfare to which the Russian and Turkish light cavalry are so accustomed. I will confine myself to considering surprises for entire armies.

Before the invention of firearms, the surprise factor was more easily effective than it is at present, because artillery and rifle shots are heard at such a great distance that it is almost impossible for an army to be surprised. Unless the primary duty, the combat protection of the main forces, is forgotten, and the enemy is among the army units before his presence is detected due to the lack of advanced posts that should sound the alarm.

The Seven Years' War provides an unforgettable example of the sudden action at Hochkirch (1758) (the Austrians defeated Frederick II, and had it not been for the subsequent slowness of their commander Daun, they could have completely destroyed his army. - Ed.). They show that surprise does not consist simply in attacking troops who are sleeping or poorly observing, but that it can be the result of a combination of surprise attack and encirclement of the edge of the army. Indeed, to take an army by surprise, it is not at all necessary that its troops should not even leave their tents unknowingly, it is important to attack it with a significant force in a certain place before preparations can be made to repel the attack.

Since armies these days seldom camp in tents when they march, prepared surprises are rare and difficult to carry out, because in order to plan such an attack, it becomes necessary to have accurate knowledge of the enemy camp. Under Marengo, Lützen and Preussisch-Eylau there was something of a surprise, but the term should only be applied to a completely unexpected attack. The only big surprise that can be cited as an example was the incident near Tarutin (on the Chernishna River on October 6 (18) in 1812, where Murat (26 thousand) was suddenly attacked and defeated by Bennigsen. To justify his carelessness, Murat pretended that there was a short truce, but in fact there was nothing of the kind, and he was taken by surprise because of his negligence (it could have been much worse if it were not for the inconsistency of the actions of the Russian columns that got lost in the forest. - Ed.).

Obviously, the most successful way to attack an army is to fall on its camp just before dawn, at a moment when nothing like this is expected. Confusion in the camp will certainly occur, and if the attacker has accurate knowledge of the locality and can give the right tactical and strategic direction to the masses of his troops, he can count on complete success, unless unforeseen events occur. This is the kind of operation that should by no means be neglected in war, though rare and less remarkable than the grand strategic combination that secures victory even before the battle has begun.

For the same reason that advantage must be gained from all possibilities of taking the enemy by surprise, the necessary precautions must be taken to prevent the same attacks. In the regulations for the management of a well-organized army, measures should be indicated to prevent them.

Section XXXV

On the attack by the main forces of places with fortifications, camps or positions fortified with trenches. About surprise attack in general

There are many places with fortifications, which, although not ordinary fortresses, are considered safe from surprise attacks, but nevertheless they can be taken by escalade (i.e., with the help of assault ladders), or by assault, or by making breaches. This is quite burdensome, since the fortifications are so steep that the use of ladders or some other means is required to reach the parapet. When attacking this kind of place, almost the same combinations appear as when attacking a camp fortified with trenches, because both of them belong to the class surprise attacks. This type of attack will differ depending on the circumstances: firstly, on the strength of the structures; secondly, from the nature of the area on which they are erected; thirdly, on how isolated they are from each other or communicate with each other; fourth, on the morale of the parties involved. History gives us examples of all their diversity.

Examples include the trenched camps of Kehl, Dresden and Warsaw, the positions of Turin and Mainz, the field fortifications of Feldkirch, Scharnitz and Assietta. Here I have mentioned several cases, each with different circumstances and results. At Kehl (1796) the field fortifications were better connected and better built than at Warsaw. There really was a bridgehead almost equal to a permanent fortification, because the Archduke considered that he must besiege it in accordance with all the rules and it was extremely dangerous for him to go on an open attack. Near Warsaw, the buildings were scattered, but quite impressive and had as a citadel Big City, surrounded by walls with loopholes, with appropriate weapons and protected by a detachment of desperate soldiers. In Dresden in 1813, a fortified fortress wall was used as a citadel, part of which, however, was dismantled and had no other parapet than that suitable for field structures. The camp itself was protected by simple redoubts at a considerable distance from each other. They were built very mediocre, with the expectation of the citadel as the only powerful fortification.

Mainz and Turin had solid circumvalence lines, but in the first case they were heavily fortified, and they were certainly not the same at Turin, where at one of the important points there was a slight parapet rising three feet, and a ditch of appropriate depth. . In the latter case, the defensive lines were caught between two fires, as they were attacked from the rear by a strong garrison at the moment when Prince Eugene of Savoy stormed them from the outside. At Mainz, the lines were attacked head-on, only a small detachment managed to bypass the right flank.

There are few tactical measures taken when attacking field fortifications. It seems probable that the defenders of the fortification could be taken by surprise if attacked shortly before daylight; it is entirely appropriate to try this. However, if this operation can be recommended in the event of an attack on an isolated fortification, it cannot be expected that a large army occupying a trenched camp will allow itself to be taken by surprise, considering that the regulations of all services require armies to be in combat readiness at dawn. Since an attack by the main body seems to be a possible method to be applied in such a case, the following simple and expedient guidelines are given:

1. Silence the cannons of the fortification with powerful artillery fire, which simultaneously has the effect of suppressing the strength of the defenders' morale.

2. Provide the troops with all the necessary equipment (such as fascines and short ladders) to enable them to cross the ditch and climb the parapet.

3. Direct three small columns towards the fortification to be taken, with skirmishers in line ahead of them, and with reserves at hand to support them.

4. Take advantage of every uneven ground to cover troops and keep troops under cover as long as possible.

5. Give detailed instructions to the leading columns as to their tasks, when the fortification will be taken, and how to attack the troops occupying the camp. Designate units of cavalry to support the attack of these troops, if the terrain permits. When all these organizational measures have been taken, there is nothing else left but to throw troops into the attack as vigorously as possible, while one detachment makes an attempt to break through at the gorge (rear part of the fortification. - Ed.). Hesitation and delay in such a case are worse than the most desperate vehemence.

Those gymnastic exercises are very useful, which prepare soldiers for escalades and overcoming obstacles; and military engineers may profitably devote their attention to providing means to facilitate crossing the ditches of field works and climbing their parapets.

Among the organizational measures in cases of this kind that I have studied, there was no better than those adopted for the assault on Warsaw and the fortified camp near Mainz. Tilke gives a description of Laudon's dispositions for attacking the Bunzelwitz camp. Although this attack was never carried out, the disposition provides an excellent model for instruction. The assault on Warsaw (September 6-8, 1831, according to a new style) can be cited as an example as one of the brilliant operations of this kind, and does honor to Field Marshal Paskevich and the troops who carried it out. As another example (not to follow) it is necessary to recall the organizational measures taken for the attack on Dresden in 1813 (leading to the defeat of the allied army. - Ed.).

Among the attacks of this type we can mention the unforgettable assaults or escalades of the port of Mahon on the island of Menorca in 1756 and Bergenop Zoom in 1747. Both were preceded by sieges, but still there was a brilliant surprise attack, for in neither case was the breach large enough for a conventional assault.

Continuous lines of trenches, though at first sight better communicated with each other than lines of divided fortifications, are much easier to take, because they can extend for several leagues, and it is almost impossible to prevent the attackers from breaking through them at any point. The capture of the defense lines of Mainz and Wissembourg, which is described in the History of the Wars of the Revolution (chapters XXI and XXII), and the defense lines of Turin by Eugene of Savoy in 1706, can be considered excellent lessons for study.

This famous case of Turin, which is so often referred to, is so familiar to all readers that it is not necessary to return to its details, but I cannot pass it by without noticing how easily the victory was bought and how little was to be expected from it. The strategic plan was, of course, admirable, and the march from the Adige through Piacenza to Asti on the left bank of the Po, leaving the French at the Mincio, was excellently prepared, but extremely slow in execution. If we turn to operations near Turin in 1706, we must recognize that the victors should rather thank luck than their wisdom. It did not take a great effort of genius from Prince Eugene of Savoy to prepare the order he gave to his army. The prince must have had a strong feeling of contempt for his opponents, marching with thirty-five thousand allied troops of ten different nations between eighty thousand French on one side and the Alps on the other, and passing around their camp for forty-eight hours in the most remarkable flanking march that has ever been attempted. The order to attack was so brief and so devoid of direction that any staff officer in our day would have made a better order. Directing formations of eight columns of infantry, brigade-by-brigade, into two lines, giving them the order to take the fortifications and make gaps in them for the cavalry to pass into the camp - all these actions constituted the whole set of art demonstrated by Eugene in order to carry out his hasty enterprise. It is true that he chose a weak point of fortification, where it was too low and covered only half the torso of his defenders. But I am getting away from my subject and must return to the measures most appropriate to take when attacking positions. If they (the defenders) have enough obstacles prepared to make it difficult to storm them, and if, on the other hand, they can be outflanked or outflanked by a strategic maneuver, it is much better to follow the above course of action than to try to make a dangerous assault. . If, however, there is any reason for preferring an assault, it must be made towards one of the flanks, because the center is the point most easily supported. There have been times when an attack on one flank was expected by the defenders, and they were misled by a feigned attack of that place, while the real attack was in the center and succeeded simply because it was unexpected. In such operations, the terrain and the nature of the fighting commanders must be of decisive importance in determining what course of action is to be followed.

The attack can be carried out in such a way as it was described for camps fortified with trenches. However, sometimes it happens that these lines have barriers characteristic of permanent fortifications; and in this case the escalade would be very difficult, unless it is old earthen fortifications, the slopes of which have been flattened with time and made accessible to infantry with moderate activity. The ramparts of Ishmael and Prague are of this nature; so was the citadel of Smolensk, which Paskevich defended so brilliantly from Ney, because he preferred to take a position in the ravine ahead, and not take cover behind a parapet with a slope of barely thirty degrees.

If one edge of the front line is on the river, it seems absurd to think of penetrating its flank, because the enemy, gathering his forces, a large mass of which will be near the center, can crush the columns advancing between the center and the river, and completely destroy them. However, this ridiculous situation sometimes led to success, because the enemy, pushed behind his lines, rarely thinks of counterattacking the attacker, no matter how advantageous his position may seem. The general and the soldiers who seek shelter behind the lines are already half defeated, and the idea of going on the offensive does not occur to them when their fortifications are attacked. In spite of these facts, I cannot advise such a course of action, and a general who will take such a risk and share the fate of Marshal Talar at Höchstätt (Hochstädt) in 1704 will have no reason to complain about fate.

There are not so many options for defending trench-fortified camps and positions. First of all, you should make sure that there are strong reserves located between the center and each of the flanks, or, more precisely, to the right of the left flank and to the left of the right flank. With the adoption of these measures, support can be easily and quickly given to the threatened point, which could not be done if there were only one central reserve. It has been argued that three reserves will not be too many if the fortification is very extended, but I am strongly inclined to the view that two will suffice. One more recommendation can be given, which has great value. It consists in conveying to the troops that they should never despair at any place in a defensive position that may be under pressure, because if a good reserve is at hand, the attacker can be counterattacked with him and successfully driven out. him from a fortification he believed was under his control.

surprise attacks

These are bold undertakings undertaken by an army detachment with the aim of attacking the garrisons of disputed points of varying degrees of fortification or importance. Despite the fact that surprise attack as if it were an entirely tactical operation, its importance, of course, depends on the strategic importance of the strongholds being captured. It is therefore necessary to say a few words with reference to surprise attacks in paragraph XXXVI, speaking of detachments. However tedious such repetitions may seem, I am obliged to describe here the method of carrying out these operations, since it is obvious that this is part of the topic of attacking field fortifications.

I do not mean to say that the rules of tactics apply to these operations, because the name itself, sudden attack, suggests that the usual rules do not apply to them. I just wanted to draw attention to them and refer my readers to the various works, both historical and didactic, in which they are mentioned.

Before that, I noted that important results can often be the consequence of these enterprises. The capture of Sozopol by the Russians in 1828, the unsuccessful attack by General Petrash Kehl in 1796, the brilliant surprise operations at Cremona in 1702, at Gibraltar in 1704 and at Bergenop-Zom (Holland) in 1814, as well as the escalades at the port of Mahon (the island of Menorca) and Badajoz, give an idea of the various types surprise attack. Some of them give effect with their suddenness, others - with an open onslaught of forces. Skill, cunning, courage on the part of the attackers, and the fear that grips those who are attacked are some of the factors that influence the successful outcome. surprise attack.

Once the war is started, the capture of a fortified point, however strong, is no longer as important as before, unless it directly affects the results of a large strategic operation. The capture or destruction of a bridge protected by fortifications, a large convoy, a small fort blocking important passages, and finally, the capture of a point even without fortifications, but used as a large warehouse of food and ammunition, so necessary for the enemy - such are the enterprises that justify the risk that the detachment participating in them may be subjected. Examples are the two attacks made in 1799 against Fort Lucisteig in Grisen and the capture of Loisach and Scharnitz by Nehm in 1805; finally, the capture of a point, even without fortifications, but used as a large depot of food and ammunition, much needed by the enemy - such are the enterprises that justify the risks to which the detachment marching on them may expose itself.

The fortified points were captured with the ditches sometimes filled with fascines, sometimes with wool sacks; even manure was used for the same purpose. Ladders are basically necessary and should always be ready. The soldiers held in their hands and attached hooks to their boots, with the help of which they climbed onto the rocks that dominated the fortification. In Cremona, the troops of Prince Eugene of Savoy penetrated through sewer pipes.

In reading about this, we should draw lessons from these events, not rules, because what has already been done can be done again.

Topic: “Napoleon’s War Strategy and Defense Tactics of the Russian Troops.”

In Europe, from the end of the 18th century, there was a series of continuous wars. They began when a coalition of European powers led by England opposed republican France. In a bloody struggle, France defended its right to choose the form of government. The decrepit feudal-aristocratic regimes of continental Europe were defeated by the French army, born in the revolution and hardened in the struggle against the invaders. Unfortunately, this army did not notice the border, having crossed which, having suppressed the freedom of its own people, it turned into an instrument for the enslavement of neighboring countries. In France, General Napoleon Bonaparte came to power, proclaiming himself emperor. France was now essentially waging wars for world domination.

The fire of European wars captured more and more new countries. Russia was gradually involved in the struggle. In 1805 she entered into a military alliance with England and Austria against France. At the end of the same year, the Russian and Austrian troops suffered a heavy defeat from the Napoleonic army in the battle of Austerlitz.

After these events, the Turkish government, incited by French diplomacy, closed the Bosphorus to Russian ships. In 1906, a protracted Russian-Turkish war began. Moldavia, Wallachia and Bulgaria became the theater of military operations.

Meanwhile, a coalition was formed against France, consisting of England, Russia, Prussia, Saxony and Sweden. The main force of the coalition were the armies of Russia and Prussia. The allies acted inconsistently, and in 1806-1807. Napoleon dealt them a series of serious blows. In June 1807 the Russian army was defeated near Friedland. A few days later, in the town of Tilsit (on the territory of what was then East Prussia), a meeting took place between Alexander I and Napoleon. A peace treaty was also signed there.

Under this agreement, Russia did not suffer territorial losses, but was forced to join the continental blockade, i.e. break off trade relations with England. Napoleon demanded this from all the governments of the European powers with which he concluded agreements. In this way he hoped to upset the English economy. By the end of the first decade of the 19th century, almost all of continental Europe was under the control of the French emperor.

Joining the blockade put Russia in hostile relations with England. Sweden, on the other hand, refused to stop trading with England and break off the alliance with her. There was a threat of an attack on Petersburg. This circumstance, as well as pressure from Napoleon, forced Alexander I to go to war with Sweden. Hostilities continued from February 1808 to March 1809. Sweden was defeated and forced to cede Finland to Russia.

Alexander 1 granted autonomy to Finland (under the rule of the Swedish king, she did not use it). In addition, Vyborg, which had been in the possession of Russia since the time of Peter 1, was included in Finland. The Grand Duchy of Finland became a separate part of the Russian Empire. It minted its own coin and had a customs border with Russia.