Based on an article by A. Volynets.

In 1907, according to statistics, in Russian imperial army per thousand recruits there were 617 illiterate, while in the army German Reich There was only one illiterate per 3 thousand conscripts. The difference is 1851 times.

The multimillion-dollar conscript armies that would move into multi-year battle in August 1914 required not only millions of privates, but also a huge number of officers, especially junior ones, who had to lead the soldiers.

In the Russian Empire, which during the First World War conscripted over 16 million people into the army, less than 10% of this huge mass could apply for positions of junior commanders with an education comparable to a German school education.

The combat losses of the officer corps of the Russian army in 1914-17 amounted to 71,298 people, of which 94% were junior officers - 67,722 dead. Moreover, most of the killed officers (62%) died on the battlefield in the first year and a half of the war. There was a huge shortage of commanders in the army, especially junior ones.

The poor training of the soldiery peasant masses was forced to be compensated by the activity of junior officers - such activity under enemy fire naturally entailed increased losses among company-level commanders, and the same low literacy of the rank and file, in turn, prevented the mass production of junior officers from them.

By September 1, 1915, when the so-called great retreat ended, during which the western provinces of Russia were abandoned, the shortage of officers in the Russian army units, according to the General Staff, amounted to 24,461 people.

In those days, the Commander-in-Chief of the North-Western Front, Infantry General Mikhail Alekseev, wrote in a report to the Minister of War: “The state must take the most persistent measures to provide the army with a continuous flow of new officers. Already at present, the shortage of officers in infantry units on average exceeds 50 %".

The lack of basic literacy had a catastrophic effect on the battlefield. During battles of an unprecedented scale, first of all, rifles were lost en masse, soldiers and junior officers died en masse.

But if rifles could still be bought urgently in Japan or the USA, and soldiers could be drafted from numerous villages, then officers could neither be bought nor drafted. Therefore, with the beginning of the war, anyone began to be appointed to officer positions, as long as they had sufficient education.

On the eve of the First World War, the most junior officer rank in the Russian Imperial Army in peacetime was second lieutenant - it was in this rank that most graduates of military schools entered the service.

However, in case of war, another military rank was provided for reserve officers, which occupied an intermediate position between second lieutenant and lower ranks - ensign.

In case of war, this title could be received by soldiers drafted into the army and distinguished themselves in battle with secondary and higher education - that is, those who graduated from universities, institutes, gymnasiums and real schools.

In 1914, the share of citizens with such education did not exceed 2% of the total population of Russia. For comparison, by the beginning of the Great War, only in Germany, with a population 2.5 times smaller than in the Russian Empire, the number of people with such an education was 3 times greater.

By July 1, 1914, there were 20,627 warrant officers in the reserves of the Russian Imperial Army. Theoretically, this should have been enough to cover the vacancies for company commanders that opened up with mass mobilization. However, such a number did not in any way compensate for the huge losses of junior officers that followed in the first months of the war.

While still developing plans for future military operations, the Russian General Staff in March 1912 proposed creating special schools for warrant officers in addition to the existing military schools for accelerated training of officers during the war.

And already on September 18, 1914, a decision was made to create six such schools - four were opened in reserve infantry brigades located on the outskirts of Petrograd in Oranienbaum, and one school each in Moscow and Kyiv.

Admission to these schools began on October 1, 1914, and they were initially considered as a temporary measure, designed for only one graduation of warrant officers.

However, the losses of junior commanders at the front increased and temporary schools quickly became permanent. Already in December, four new schools were created. Initially they were called "Schools for accelerated training of officers at reserve infantry brigades", and in June 1915 they began to be called "Schools for training warrant officers of the infantry".

It was in 1915 that the most severe military crisis occurred in Russia, when there was a catastrophic shortage of rifles, shells and junior officers at the front. Rifles then began to be bought en masse abroad, and warrant officers were trained in a hastily created network of officer schools.

If by the beginning of 1915 there were 10 such educational institutions, then by the end of the year there were already 32. At the beginning of 1916, 4 more new schools were created.

In total, as of 1917, 41 warrant officer schools were created in the Russian ground forces. The largest number of them were located in the capital and its environs - four in Petrograd itself, four in Peterhof and two in Oranienbaum. The second largest number of schools for warrant officers was Moscow, where seven such educational institutions were created.

Five schools of warrant officers each operated in Kyiv and Tiflis (Tbilisi). Georgia, by the way, had the largest number of schools of all the national borders - there were as many as eight of them; in addition to Tiflis, there were schools for warrant officers in the Georgian cities of Gori, Dusheti and Telavi.

Three schools of warrant officers were created in Irkutsk and Saratov, two each in Kazan and Omsk, one each in Vladikavkaz, Ekaterinodar and Tashkent.

The massive creation of officer schools made it possible by the beginning of 1917 to overcome the shortage of junior commanders at the front. If from July 1, 1914 to the beginning of 1917, all military schools of the Russian Empire graduated 74 thousand officers, then the ensign schools during that period trained 113 thousand junior commanders.

The peak of graduation occurred precisely in 1917: from January 1 to November 1, military schools trained 28,207 officers, and ensign schools - 40,230.

However, almost a quarter of a million warrant officers trained during all the years of the First World War only compensated for the loss of junior officers at the front. The scope and ferocity of the fighting on almost one and a half thousand kilometers of front were such that the ensign in the trenches did not survive for very long.

According to statistics from the First World War, a Russian ensign on the front line lived on average 10-15 days before being killed or wounded. Of the approximately 70 thousand killed and wounded in the Russian army in 1914-17, 40 thousand were warrant officers, who accounted for the highest percentage of combat losses among officers and privates.

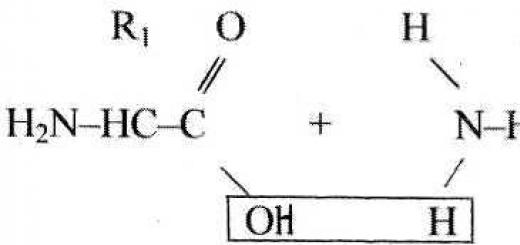

Ensign schools were staffed by persons with higher and secondary education, civilian officials of military age, students and, in general, any civilians who had an education at least above primary school.

The course of training was only 3-4 months. Future junior commanders of the active army were taught the basics of military science in accordance with the real experience of the world war: small arms, tactics, trench warfare, machine gunnery, topography, communications service. They also studied military regulations, the basics of army law and administrative law, and underwent combat and field training.

The usual daily routine at the warrant officer school looked like this:

at 6 a.m. rise, served by a trumpeter or bugler;

from 6 to 7 a.m. time for getting yourself in order, examining yourself and morning prayer;

at 7 o'clock morning tea;

from 8 a.m. to 12 noon, scheduled class classes;

breakfast at 12 o'clock;

from 12.30 to 16.30 scheduled drills;

16.30 lunch;

from 17.00 to 18.30 personal time;

from 18.30 to 20.00 preparing assignments and lectures for the next day;

at 20.00 evening tea;

at 20.30 evening agenda and roll call;

at 21.00 evening dawn and lights out.

Classes were not held on Sundays and during Orthodox holidays; on these days, cadets from ensign schools could be sent to the city.

The level of knowledge of students in schools was assessed not by points, but by a credit system - satisfactory or unsatisfactory. There were also no final exams. The general conclusion about the professional suitability of graduates was made by special commissions headed by school heads.

Those who graduated from the school of warrant officers in the 1st category received the right to this lowest officer rank. Graduates of the 2nd category were sent to the active army in ranks that correspond to the current sergeants, and they received the rank of warrant officer at the front after 3-4 months of successful service.

Warrant officers who completed school unsatisfactorily belonged to the 3rd category of graduates. They, as those who did not meet the criteria for officer rank, were sent to the troops to serve as lower ranks and could not subsequently enter military educational institutions.

Since February 1916, cadets in ensign schools were renamed from students to cadets, and in January 1917, military school uniforms were introduced for them; before that, future ensigns wore the uniform of infantry regiments.

Also, by decree of Emperor Nicholas II, special badges were introduced for graduates of ensign schools with the aim of uniting them “into one common family and to establish an external corporate connection.”

In fact, by these measures, the tsarist command equated graduates of ensign schools with cadets of military schools. However, unlike career officers, warrant officers, as wartime officers, had the right to promotion only to the rank of captain (captain in the cavalry), that is, they could at most reach the rank of battalion commander, and at the end of the war, upon demobilization of the army, they were subject to dismissal from the officer corps .

During the First World War, schools for warrant officers were opened not only in the infantry, but also in other branches of the military. Since June 1915, the Petrograd school for training warrant officers of the engineering troops operated; in December of the same year, a school for warrant officers for Cossack troops was opened in Yekaterinodar.

The duration of training in the Cossack school for warrant officers was 6 months; “natural Cossacks” from the Kuban, Terek, Don, Orenburg, Ural, Transbaikal, Siberian, Semirechensk and Ussuri Cossack troops were enrolled in the school. In June 1916, a school for training warrant officers for survey work was opened at the military topographic school in Petrograd.

Military schools occupied a special place in the newest branch of the military, which arose only in the 20th century - in aviation. Already the first year of hostilities revealed the problem of a shortage of flight personnel.

Therefore, on November 12, 1915, the military leadership of the Russian Empire even allowed private wartime aviation schools, in which officers and privates were trained in flying.

In total, during the First World War, there were three private military schools in Russia: the School of the All-Russian Imperial Aero Club in Petrograd, the School of the Moscow Aeronautics Society in Moscow, and the so-called School of Aviation of New Times, established at the airplane factory in Odessa.

True, all aviation schools in Tsarist Russia - both state-owned and private - were very small with the number of cadets being several dozen people.

Therefore, the Russian government entered into an agreement with England and France to train pilots in these countries, where about 250 people were trained during the war. In total, during the First World War, 453 pilots were trained in Russia.

For comparison, Germany lost an order of magnitude more pilots in 1914-18 alone - 4,878. In total, during the war years, the Germans trained about 20 thousand pilots. Russia, having by 1914 the largest air fleet in the world, during the war years fell sharply behind the leading European powers in the development of its air force.

The socio-economic backwardness of Russia affected the training of military specialists until the end of the war. For example, in all the warring powers of Western Europe, significant additions to the junior officer corps were provided by the relatively large student body.

In terms of the number of students per capita, Russia was noticeably inferior to these countries. Thus, in the German Second Reich in 1914, with a population of 68 million people, there were 139 thousand students; in the Russian Empire, with a population of 178 million, there were 123 thousand students.

In November 1914, when the Germans in the West tried to prevent the formation of a positional front with a decisive offensive, their attacking divisions in Flanders consisted of almost a third of German college and university students.

In Russia, the number of students per capita was 3 times smaller, the patriotic enthusiasm of the first months of the war quickly subsided, and until the beginning of 1916, compulsory conscription of students was not resorted to.

Due to the catastrophic shortage of educated personnel in the army, the first conscription of students in Russia was carried out in March 1916.

It covered first-year students who had reached the age of 21. The tsarist command intended to quickly turn all the students into officers.

For this purpose, it was planned to create Preparatory Training Battalions in the rear, in which students would undergo initial soldier training for three months, after which they would be sent to ensign schools.

It is curious that students were considered by the army command as a privileged class. Thus, in July 1916, the department for the organization and service of troops of the General Staff noted:

“Taking into account that the preparatory battalions will only include students from higher educational institutions, most of whom will subsequently be assigned to military schools and warrant officer schools, we believe that it would be more convenient to establish for these young people during their stay in the preparatory battalions appeal to you.

The commanders of these battalions must have the appropriate tact to successfully conduct the military education of intelligent student youth, which is why the proper choice of such seems very difficult."

However, not only the selection of teacher-officers for ordinary students turned out to be difficult, but also the conscription of university students itself.

Of the 3,566 students in Moscow and Petrograd who were subject to conscription in March 1916, less than a third showed up and turned out to be fit for military service - only 1,050. The rest evaded on one or another pretext of varying degrees of legality.

Moreover, at the height of the World War in the Russian Empire there was simply no criminal punishment of any kind for students evading military service.

When the War Ministry first became concerned with this issue in July 1916, proposing to punish students who evaded the spring draft, the Ministry of Internal Affairs suddenly opposed it, reminding that the law had no retroactive effect.

Note that all this bureaucratic game of legality took place in July 1916, in the midst of fierce and bloody battles.

This month only during Brusilovsky breakthrough in Galicia, the Russian army lost almost half a million people killed and wounded, and in Belarus, when trying to recapture the city of Baranovichi from the Germans, the Russian army paid 80 thousand people for the first line of German trenches alone.

Huge losses led to the fact that anyone with sufficient education, including the so-called unreliable ones, began to be appointed to the positions of junior officers.

For example, in Tsaritsyn, where in just 3 years Stalin’s political star would rise, a Preparatory Student Battalion was formed in June 1916, where all unreliable educated elements were sent, including people who were under secret police surveillance for belonging to the revolutionary underground.

As a result, several dozen active figures in the future revolution emerged from this battalion - from the leading ideologist of Stalinism, Andrei Zhdanov, to one of the leaders of Soviet foreign intelligence, Lev Feldbin, or the main Soviet specialist on Mayakovsky’s work, Viktor Pertsov.

As a result, by the beginning of 1917, four dozen ensign schools were able to cope with the shortage of command personnel at the front, but at the same time the social and political appearance of the Russian Imperial Army changed dramatically - the junior officers were no longer at all loyal to the authorities. All this had a decisive impact in February 1917.

In May 1917, the very next day after his appointment as Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky issued an order allowing all lower ranks in the ranks of non-commissioned officers, regardless of the level of education, but with at least four months of service experience in the front lines, to become ensigns. parts. The government was preparing a large summer offensive of the Russian army for June, which required a mass of junior commanders.

Kerensky's offensive failed and German troops on the Russian front began their counteroffensive. By the fall, the crisis of the Russian army began to turn into outright collapse.

The provisional government tried to improve the situation at the front by any feverish measures. For example, on September 28, 1917, even women who served in volunteer “shock” units, popularly nicknamed “death battalions,” were allowed to be admitted to the rank of ensign.

Badge of graduation from the school of warrant officers.

The year 1917 not only eliminated the shortage of junior commanders, but also created a surplus of them due to a decrease in the quality of training and selection of personnel.

If from 1914 to 1917 the army received about 160 thousand junior officers, then in the first 10 months of 1917 alone, over 70 thousand new wartime warrant officers appeared in the country. These new officers not only did not strengthen the front, but, on the contrary, only intensified the political chaos in the country and the army.

Therefore, as soon as they seized power, the Bolsheviks immediately tried to reduce the officer corps. Already on November 1, 1917, by order of the People's Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs Nikolai Krylenko, all officer graduations from military educational institutions were canceled and the organization of the recruitment of new cadets to military schools and warrant officer schools was prohibited.

As a result, it was this order that led to the mass struggle of offended cadets against the Bolsheviks - from the Moscow skirmishes in November 1917 to the first “ice campaign” in February of the following year.

Thus, Russia crawled from a world war into a civil war, on the fronts of which former graduates of ensign schools would actively fight with each other on all sides.

“Tank pogrom of 1941”, “The year 1942 is a training year”, “Ten Stalinist strikes” and “Leningrad Defense” - all these are books by historian Vladimir Beshanov, a guest of the “Price of Victory” program of the radio station “Echo of Moscow”. Together with presenters Vitaly Dymarsky and Dmitry Zakharovov, Vladimir Vasilyevich discusses the professional training of military personnel Soviet Union and Germany on the eve of the war.

The civil war left a big imprint on Soviet military doctrine, which was idealized and promoted at all levels. When there was a dispute about military doctrine back in the 1920s, Comrade Frunze wrote that future war will be a civil war, we will come to the aid of the proletarians of other countries, they will rise up in rebellion against the exploiters, and the future front of our actions will be the entire European continent.

From the statements of many Soviet military leaders, two contradictory ideas follow: on the one hand, they said that the upcoming war would be easy and quick, on the other, the idea of victory at any cost was propagated. For example, Deputy People's Commissar of Defense, Marshal Kulik said: “Where the forest is cut down, chips fly there. There’s no point in crying over the fact that someone was shot somewhere.” In general, human life in the Soviet country, especially in the 1930s, after the great turning point, collectivization, widespread famine, great purge, and so on, was valued cheaply. Accordingly, they did not invest much in the fighter’s individual training, which later played a dramatic role.

In the 1930s, the life of a Soviet soldier was cheaper than a spool of cable.

A few words about the preparation of the Wehrmacht. The basis of the basics is the infantry. In the Wehrmacht after 1935, the duration of training in infantry units was 16 hours a day. The soldiers shot almost every day, learned to run, dig trenches, navigate the terrain, establish communications, establish interaction between neighboring units, communications between branches of the military, and so on. That is, preparation took the entire daylight hours and even the evening part of the day. Therefore, as Dieter Noll wrote, the soldiers cursed the galvanized iron with cartridges that they carried to the shooting range every day, they ran endlessly, crawled endlessly, learned to dig into the ground, and this continued from 1935 to 1944.

As for our army, any conscript who served in it knew that the main weapon of a Soviet soldier was a shovel. Mostly soviet soldier He was engaged in household work (almost always), drill and political training. Here are some numbers on the quality of our middle and junior level command staff. On May 1, 1940, the infantry units lacked 20% (approximately one-fifth) of their commanding personnel. The quality of training of commanders of military schools was as follows: 68% of the command personnel at the platoon-company level had only a short-term five-month training course for junior lieutenant, higher military education by the beginning of the war with Germany, only 7% of officers had, 37% did not have a complete secondary education, approximately 75% of commanders and 70% of political workers worked in their positions for no more than one year.

As for the senior command staff, many military historians have the idea that if it were not for the repressions against the marshals (according to various estimates, approximately 40 thousand officers of various levels became victims of the Stalinist repressions of the late 1930s), then we would have had a combat-ready an army with excellent commanders. These repressions had moral consequences: they knocked out of the heads of the military leaders any unnecessary thought, independence, or initiative. And all this in the presence of a massive amount of equipment and weapons. The Germans also note this: “We had the impression that they ( Soviet commanders) will never learn to use this tool.”

Stalin's repressions of the late 1930s had moral consequences

A few words about pilot training. For the Germans, training a fighter pilot took three years. There were three schools “A-Shule”, “B-Shule” and “Ts-Shule”. In the first year, the pilot was taught to fly, stay in the air, and bring his training to the level of muscle memory. For the second year they learned to shoot. And if in our country shooting was a very rare entertainment for pilots, then from the moment all the training on the ground was completed (on simulators), almost daily shooting began: Messerschmitt pilots shot at balloons tied on ropes a few meters from the ground .

In the same year, terrain orientation and night flights were practiced. And the third year of training was already a combination of all the acquired skills and tactical preparation for air combat, which, after the start of the war, was carried out by the most effective pilots who came to the schools. It turns out that the German pilot had at least 200 hours of flight time during his years of study. In the pre-war years it often reached 600 hours.

Approximately the same situation was observed in the tank forces. For example, one figure: the standard, the number of shots fired by the crew of the Tiger tank, T-6, is 12 rounds per minute. If the crew did not fulfill this standard, they were simply not allowed to participate in combat operations.

In the USSR, 5 hours of driving were allotted for driver training, as they saved fuel. There was no time to master new technology. Here, of course, one more thing must be taken into account: after all, the country was illiterate. If we compare it with the Wehrmacht, then the basis of the army rank and file was made up of fairly highly qualified German workers who had undergone some training before the army. In our country, the majority were villagers who were actually transferred from a horse to a tank. Uborevich, who had not yet been executed, reported in 1937 that out of every hundred conscripts, 35 were illiterate.

It must be said that the top military leadership were not geniuses. The same Voroshilov, who was the People's Commissar of Defense for a very long time, his military skill, military art was limited to the civil war. And this is understandable, since after the revolution, civil war all the highest posts were shared by the winners, so most of our commanders have a 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th grade education. And everything else is courses. Here is Army Commander Dybenko. It is written in his biography that he graduated from two academies: the Soviet Academy and the Academy of the German General Staff. However, he did not know the American language. General Maslennikov came to the academy with 3-4 years of education...

Most Soviet commanders were illiterate

However, saving fuel, shells, and cartridges before the war did much more damage than the lack of education. Finding themselves face to face with the enemy, it turned out that Soviet tank crews did not know how to shoot, did not know how to repair own equipment. All of Ukraine and Belarus were littered with abandoned tanks. The officers recalled that during breaks between battles they taught their soldiers to shoot cannons, disassemble and assemble something.

The question arises: how did our poorly trained army emerge victorious and still break the necks of the trained Germans? As Viktor Astafiev wrote, “we overwhelmed the Germans with mountains of corpses and filled them with rivers of blood.” In 1941, we lost about 3 million 600 thousand people as prisoners alone. Another million or one and a half fled to the forests, deserted, settled in villages somewhere with widows, and some ended up joining the partisans. And combat losses amounted to about 400 thousand. At the same time, we lost almost all 23 thousand tanks and 6.5 million small arms.

At the time of the attack on the Soviet Union, the Luftwaffe had 5 and a half fighter divisions: 52nd Division (Crimea, Kuban), 54th (Leningrad Front), 5th (Murmansk, Arkhangelsk), 51st and 3rd (Central Front). Back in 1941, during the attack on Moscow, one training regiment was attached - the 27th division. The Germans had no more fighters on our front. So they shot down those thousands and thousands of planes in ’41, and in ’42, and in ’43, and beyond.

People say that winners are not judged. Yes, but if you think that these victors are several tens of millions who simply died due to the inability of our military leadership, military leadership, political leadership, due to the fact that they really just strewed the road to victory, then it is unknown, they are judging here - don't judge.

Let's look at a short episode. General Katyshkin of the 59th Army recalled with admiration: “They brought two companies of marching reinforcements to the Volkhov Front - Uzbeks and Tajiks. (...) They don’t know anything in Russian, not a word, they brought it, they don’t know how to do anything. The political department agitator went. In an hour I taught them how to disassemble and assemble a rifle and shoot. And I ask this agitator: “What about you, how do you know the Uzbek language?” And he answers: “Yes, I don’t know.” “How did you communicate with them?” “What kind of communists will we be if we don’t find mutual language with people?" And these two companies went into battle that same day, right from this clearing.” Was it worth taking the guys two thousand kilometers to these Volkhov forests in order to mediocrely kill them right there? Moreover, according to the recollections of veterans of the Volkhov Front, these guys, they were from the steppes, they were afraid of the forest, they collected German grenades, threw them into the fire for warmth, that is, people were absolutely incompetently destroyed by their own command. There are many such examples. Will they be judged for this or not?..

Viktor Astafiev: “We overwhelmed the Germans with mountains of corpses and filled them with rivers of blood”

That's how we fought. It is known that when Eisenhower asked Zhukov: “How do you take into account losses when you need to overcome a minefield? We have great attention to this issue, death from mine clearance.” He answered: “Yes, we are advancing through minefields as if they were not there, and we are attributing the losses to enemy machine-gun fire.”

A few words about order 227 (“Not a step back”) and the barrage detachments that existed before this order, and not only in our army. If you read the memoirs of the chief of staff of the 4th Army Sandalov, he places barrage detachments behind his troops already on the third day of the war, June 25. And order 227 itself... Yes, it legalized penal battalions, penal companies. But even in September 1941, Zhukov shot his troops with machine guns near Leningrad without any order 227.

http://diletant.media/articles/28250965/

Larich 29-07-2011 14:11

Question

Many people know that at the beginning of the war, junior officers were trained at an accelerated pace - 3-6 month courses and that’s it.

But in my opinion, from 43-44, the previous training was restored - 2-3 years. Although I have heard many stories on this topic.

One of them (according to my fellow traveler, a front-line artillery officer)

He was drafted as a soldier, then they immediately sent him to school, he studied there for about a year, graduated, and then soon the war ended, and they didn’t allow him to demobilize - like he was drafted as a soldier and served for the same amount of time. He served until he was 53 or 54. It seems that senior officers were demobilized without problems at that time, but junior officers were not released.

And immediately the second question - if at that time during his service a soldier became an officer, then how long did he serve, as a soldier or as an officer?

petrp 29-07-2011 17:27

My father served and fought as a private from July 1942 to April 1943. In August 1944 he graduated from the Courses for Junior Lieutenants of the 2nd Ukrainian Front.

This means that at least in 1944 there was parallel training in schools and courses.

After the war, in July 1945, he was certified in a separate officer reserve regiment. The command's conclusion: "It is advisable to remain in the cadres of the Red Army. Use it as a platoon commander."

It follows that not all officers were left in the army. And besides, it seems that in 1954 there was a reduction in the army by 1.5 - 2 million people.

petrp 29-07-2011 17:54

Service life during the Great Patriotic War is a different story. Some served as conscripts even before the war, plus the war and after the war demobilization did not begin immediately. So, there were privates and sergeants who had to serve in general for up to 7 - 8 years.

Danishin 29-07-2011 18:59

I have heard more than once about those who were drafted in 1939, fought in Finland and then throughout the Great Patriotic War. Perhaps there were those who also fought in Mongolia as privates, and then throughout the entire Second World War.

spy der 29-07-2011 19:51

quote: Originally posted by petrp:

Service life during the Great Patriotic War is a different story. Some served as conscripts even before the war, plus the war and after the war demobilization did not begin immediately. So, there were privates and sergeants who had to serve in general for up to 7 - 8 years.

Exactly, the grandfather of the 40th year of conscription, demobilized in the 49th year as a sergeant major.

SanSanish 29-07-2011 21:02

quote: Originally posted by petrp:

So, there were privates and sergeants who had to serve in general for up to 7 - 8 years.

And not only pre-war conscription. My grandfather left to become a partisan at the age of 16, and in 1944, after the liberation of Belarus, he was drafted into the navy and sent to Leningrad. He served on the cruiser "Kirov" for another 8 years. I don’t know why they weren’t demobilized earlier; I didn’t ask because I was young. I remember from my grandmother’s stories that they didn’t let me go home for a very long time.

VladiT 30-07-2011 12:07

quote: And immediately the second question - if at that time during his service a soldier became an officer, then how long did he serve, as a soldier or as an officer?

Good answers to these questions are in voice recordings of conversations with veterans on this site -

http://www.iremember.ru/

Unlike the propaganda campaigns of the early perestroika times, in general, there is no impression that everyone was sent unprepared and not taught.

Which is logical. No matter how you say “halva” in the sense that “the regime is bloody and merciless” - nevertheless, then both the regime and the performers needed a RESULT, and not a party (like today).

And for the result, untrained meat does not give anything. A person who likes to “fight with meat” will simply not complete the task and will be shot for this by Mehlis or another “smersh” - that’s all.

Once upon a time Isaev seems to have successfully asked good question“How much meat do you need to throw on a tank to make it stop?”

Rosencrantz 30-07-2011 12:08

quote: Perhaps there were those who also fought in Mongolia as privates, and then throughout the entire Second World War.

Yes they were.

My grandfather Vasily Semyonovich served in the cavalry in Mongolia.

In 1941 he was sent for retraining, after which in 1942 he ended up at Stalingrad as a junior lieutenant of artillery. He ended the war in the city of Wittstock in the state of Brandenburg as the commander of a 45-mm anti-tank gun battery. Demobilized in October 1945

The second grandfather, Ivan Vasilyevich, served in aviation as a mechanic. He said that due to a lack of specialists, the service life was constantly being added - and so it lasted from 1937 until the start of the Second World War. He was demobilized, or rather went into exile in August 1945. Staff Sergeant.

Danishin 30-07-2011 01:16

quote: Originally posted by Rosencrantz:

The second grandfather, Ivan Vasilyevich, served in aviation as a mechanic. He said that due to a lack of specialists, the service life was constantly being added - and so it lasted from 1937 until the start of the Second World War. He was demobilized, or rather went into exile in August 1945. Staff Sergeant.

What kind of “interesting” demobilization is this??? Didn't please you with your nationality????

nicols 30-07-2011 02:24

A lot depends on the VUS.

political officers were prepared quickly (mouth closed - workplace removed), not very many specialists (infantry is a separate issue). The political officers quickly backed down, the specialists - not so much.

the war did not count towards length of service, even without taking into account ranks. remember how many times they served as conscripts on the royal battleships?

By the way, for example: ordinary soldiers of the assault battalions (after the 42nd) were trained for at least 3 months.

Rosencrantz 30-07-2011 06:11

quote: What kind of “interesting” demobilization is this??? Didn't please you with your nationality????

Origin class alien))

Popovich.

They made jokes about the arrangement, he, apparently alone, did not report, or rather did not report it - a fairly common story, as I did right there on the Hansa knowledgeable people explained.

The punishment, however, was also nonsense - he lived for two years in the city of Osh, Tajik SSR, his grandmother followed him there like the wife of a Decembrist, two children were born during this time, including my father.

The link worked for future use, I must say. It is characteristic that the grandfather considered snitching disgusting, but constantly, literally every day, he hammered into his children, and then his grandchildren, not to talk too much, watch your language and not get involved with talkers.

VladiT 30-07-2011 11:27

Discussion by Isaev-Buntmann radio Echo of Moscow about the preparation of the armies of the USSR-Germany and the losses-

"...A.ISAEV - As for military training. Naturally, in the Red Army the training was quite long. If we talk about, for example, how the reserve armies that entered the battle at Stalingrad, they had training, duration: and them, how they say, it wasn’t just yesterday that they were pulled out from behind a school desk or torn from a machine and thrown into battle. The average training time was about three months. And people were taught for three months. But at the same time it was necessary to give some basic skills, at the level , there, the simplest “subordination”, “to the right”, “to the left”, etc., some kind of general cohesion of the unit, and this was not enough. The army could not make up for what: the given that it had to the state ". Because the army could not give a person in three months: from four classes of education to ten classes of education. This is objectively impossible. The Germans could take, there, the same three-month course and act better.

S.BUNTMAN - That is. completely different at the base.

A. ISAEV - Yes, again, we take 1945. Germans: I am quoting the history of the German division "Frunsberg", this is not a Soviet document. People were caught leaving the cinema and a few days later they were already going to advance in Operation Solstice. This is February 1945. Well, naturally, the people who were caught near the cinema had a different level of education, and it was easier for them to give some algorithms. Although what happened to the Germans in 1945 is a real nightmare, this is what they usually tell us about us in 1941, about one rifle for five people. Here is one rifle for five: I have not yet found a single unit of the Red Army - there, a division - that would have one rifle for five. And I can immediately name such a German division.

S.BUNTMAN - Well, maybe:

A. ISAEV - Yes, but nevertheless, this is a fact. Those. There is documentary evidence that the “Friedrich Ludwig Young” division, named as such, in April 1945 had one rifle for three..."

http://www.echo.msk.ru/programs/netak/514463-echo/

petrp 30-07-2011 13:24

quote: Unlike the propaganda campaigns of the early perestroika times, in general, there is no impression that everyone was sent unprepared and was not taught.

My father fought in the Airborne Forces. The preparation before being sent to the front was about 5 months. Including skydiving.

quote: But untrained meat does not give anything for the result. A person who likes to “fight with meat” will simply not complete the task and will be shot for this by Mehlis or another “smersh” - that’s all.

This also happened. My father recalled that one of their regiment commanders was arrested and then shot for heavy losses.

spy der 30-07-2011 14:12

VladiT, not for the sake of self-interest... but please don’t quote Isaev anymore...

VladiT 30-07-2011 15:03

quote: Originally posted by spy der:

VladiT, not for the sake of self-interest... but please don’t quote Isaev anymore...

Why on earth and why?

-- [Page 4] --

Combat training programs for formed military units and training of reserves in reserve rifle and special units were approved by the People's Commissar of Defense. By Order of the People's Commissar of Defense No. 0429 of October 14, 1943, in order to improve the matter of manning and the most expedient use of trained reserves, all issues of manning and creating trained reserves for all branches of the military were concentrated under the jurisdiction of the Head of the Red Army. Since the beginning of the war, the management of combat training, the organization and material support of reserve and training units of the armed forces was entrusted to the commanders and chiefs of the armed forces of the Red Army and military districts.

In the conditions of the outbreak of war, the attempts of the party and Komsomol bodies of Siberia to organize military training in Komsomol organizations and primary organizations of Osoaviakhim could not solve the problem of full-fledged military training of reserves for the active army. Due to insufficient educational and material support, the quality of military training of conscript youth in the units of the All-Union Educational Instruction Service did not fully meet the requirements of the front. Under these conditions, only the military method of training military-trained reserves ensured the continuous replenishment of the active army with trained human resources.

The dissertation examines the process of establishing a system for training reserves for the front, the organizational structure of reserve and training units and formations, the procedure for the formation and composition of marching units, the activities of the command of units and formations in carrying out established orders for the training and dispatch of trained reserves.

The dissertation author identified and analyzed the sources of manning combat, reserve and training units. During the formation of reserve formations of the second stage in August–September 1941, serious difficulties arose with their staffing with command and control personnel. Reserve officers, called up to the positions of company commanders - platoons, made up from 72% to 82% of the staff, most of them did not have military education or service experience. The appointment of ordinary soldiers to positions of junior commanders had a negative impact on the quality of training.

Senior conscripts (up to 50 years of age and above) and those of regular conscription age, military personnel after recovery in hospitals, conscripts previously reserved for the national economy, a variable composition of military educational institutions and reserve units, and women were sent to staff combat and rear military units and formations. Reservists under the age of 46 and front-line soldiers from hospitals with education up to 3 classes were sent to staff reserve rifle units and formations, and artillery reserve units - from 4 to 6 classes. Along with reserve servicemen, military personnel from reserve and training units, military transit points and women were sent to staff special units.

Mostly conscripts born in 1924 - 1927 were sent to staff training units for the training of junior commanders. and those liable for military service under the age of 35 with an education of at least 3 - 4 classes - for rifle training; with at least 5 years of education – tank training; in automotive training - up to 45 years old and communications training units - up to 47 years old. In the second half of 1942, older conscripts (up to 50 years old) with a training period of 2 months began to be sent to staff reserve artillery brigades.

One of the sources for staffing spare parts were conscripts from among the special contingent and repressed citizens. In the structure of replenishment, the number of such conscripts was 15–20% and remained unchanged throughout the war. Since 1943, reserve and training rifle and artillery units and formations were staffed primarily with conscripts, while older conscripts were sent to individual units and subunits. The trend of staffing these units primarily with resources from the Siberian regions continued throughout the war.

In 1943 – 1944 in the Siberian Military District and the Western Front, due to a significant withdrawal of human resources (up to 70% of the total mobilized) in the first period of the war, problems arose with the staffing of spare and training units. The main source of replenishment was the re-examination and release of military personnel and conscripts. The main task of local military authorities was the implementation of monthly plans for finding human resources to staff units and formations.

The problem of training reserves in reserve formations was aggravated by the large proportion of untrained reserve personnel in the structure of military personnel. As in other military districts, by the beginning of the war their share in the regions of the Siberian Military District was about 30% and tended to increase until 1943. Significantly complicating the preparation of reserves was the sending of military commissariats to staff reserve and training units of those liable for military service and conscripts unfit for service, inconsistency in the actions of various departments and services and the continuing shortage of educational and material resources.

The duration of training for military personnel in reserve units and formations changed during the war and ranged from 2 to 6 months. At the final stage of preparation, they were included in marching units according to military specialties, provided with uniforms, food, and sent to the active army as part of marching reinforcements.

Upon arrival at the front, marching reinforcements were distributed in parts and introduced into battle. In 1941, insufficient preparedness and ill-conceived procedures for entering into battle, combined with a shortage of weapons and ammunition, led to heavy and unjustified losses, devaluing the value of such reinforcements. Since January 1942, the procedure for receiving marching reinforcements by the active army was changed. March replacements began to be sent to the formed reserve army and front-line reserve units, where they received additional training.

The second section, “Organization of combat training in reserve and training rifle, artillery, cavalry formations and signal units,” examines the organization and features of combat training for soldiers of various military specialties, and summarizes the experience of training reserves for the active army. Combat training of Siberian soldiers in the formed combat, reserve and training units was carried out differentially, in several stages, and began already in the process of their recruitment. It was distinguished by: high intensity, maximum proximity to the requirements of the front.

In order to develop practical skills and knowledge of soldiers, training grounds, camps, special defensive areas, assault zones, and anti-tank areas were equipped in units and formations. Units and units were withdrawn for 7–10 days to the areas of training fields and shooting ranges. The main emphasis was on special tactical and fire training. In order to create a real environment and consolidate acquired skills, joint training of soldiers of various specialties was practiced. The personnel learned to overcome steep slopes and lower equipment. All marching units were necessarily trained in overcoming water obstacles and shooting in the mountains and the city. March endurance and physical training of soldiers were developed during long marches of units and units with full combat gear and standard weapons. In winter, marches were made on skis, and soldiers spent a significant part of their time in mobile winter camps.

In order to study the experience of the war and improve methodological skills, mainly front-line soldiers were appointed to the positions of command and control personnel; in units and formations, training and methodological gatherings, instructor-methodological classes and briefings of officers and non-commissioned personnel were practiced. 50% of the time in the commander training system was devoted to improving military knowledge and 50% to mastering teaching methods.

The improvement in the quality of the training was facilitated by combat competition, in which both individual soldiers and units and military units participated. The main indicators of the competition were: the results of combat training, the level of military discipline and physical training, the condition of training fields, shooting ranges, the conservation and condition of weapons, internal regulations, and the quality of the marching companies handed over. The winners of the competition were awarded cash prizes, badges “For Excellent Shooting”, military ranks were awarded and commendations were announced, units were awarded challenge Red Banners, and cultural and educational property.

The dissertation author also analyzes the training system for junior commanders in reserve and training units of the Siberian Military District and the Trans-Broad Front. To train junior commanders, training formations, regimental schools and schools for senior officers were created in reserve units, formations and military schools. They were staffed by the best trained fighters of variable composition and war participants. Since August 16, 1942, 2 separate training rifle brigades were deployed in the Siberian Military District to train junior command personnel. The training period for junior command personnel for emerging combat units was 3 months and 4 months for cadets of training units and units. In 1943, the training period for junior commanders was increased to 6 months.

The training process for junior commanders was characterized by consistency and thoughtfulness. Instructional, methodological and practical skills of commanding a squad in all types of combined arms combat, fire control in combat, studying the material part of weapons and preparing them for firing were acquired and improved during single training, which was allotted 1 month. The skills of marching and combat life were formed during tactical training and exercises. Assignment condition military ranks was the successful passing of final tests.

The detachment of variable personnel for various construction, defensive and economic work had a negative impact on the training of reserves. In 1941, there were cases of military personnel being sent to the front who had not completed the training program.

In the third section “Training reserves for armored and mechanized forces” The specifics of training specialists for tank crews in reserve and training tank regiments of the Siberian Military District and the Trans-Border Front are considered.

Since the beginning of the war, the training of tank reserves in the Western Military District was carried out by the 7th reserve tank and 4th separate training tank regiments. The increase in production of T-34 tanks in Omsk and tank diesel engines in Barnaul in 1942 contributed to the creation in the Siberian Military District of a single center for the production of combat vehicles and training of crew members. In June 1942, the 30th separate training tank battalion was formed at Omsk plant No. 174. On August 2, 1942, the 4th separate training tank regiment was redeployed to Omsk. The regiment consisted of 4 training tank battalions, which trained driver mechanics, turret gunners and radio telegraph operators. The 4th battalion carried out tasks to support the educational process. In the 30th separate training tank battalion, the training of formed tank crews was completed. In September 1944, the 9th reserve tank regiment was formed on the basis of the battalion. The training of tank and tank platoon commanders was carried out by the Kamyshin Tank School, which arrived in Omsk in August 1943.

Reservists from among former tank crews were recruited to staff spare and training tank units. From November 1, 1942, to staff the Kamyshin Tank School, and from February 1943 - to training tank units, privates and junior commanders of the active army, no older than 35 years of age, with at least 7 years of education for the school and 3 classes, were sent to staff the Kamyshin Tank School. – for training parts. The training time for tank crews depended on the level of military training of the variable composition and ranged from 4 to 6 months. At the beginning of the war, the training period for tank officers was 6 months, in 1942 - 8 months, from the second half of 1943 - 1 year.

Much attention in the training of tank crews was paid to fire and special training, for which up to 50% of the teaching time was allocated. During the implementation of tactical tasks, 35% of training time was devoted to night classes. After completing training and putting together tank crews during tactical exercises with live fire, marching companies were sent to the active army or to tank military camps of the Volga Military District.

In the initial period of the war, the level of training of tank reserves was negatively affected by poor educational and material support, large differences in age and theoretical and practical training of trainees. The improvement in the quality of training of tank crews was facilitated by: conducting practical training on constructing tanks directly in the factory, the participation of soldiers in assembling combat vehicles, consistent and differentiated training, conducting joint tactical exercises and exercises with rifle units, increasing the number of motor resources and shells, front-line internships and increasing the share of front-line soldiers in the structure of permanent staff and trainees.

Fourth section “Training of sniper personnel in training units and sniper schools” is devoted to the analysis of the sniper training system deployed in Siberia since the beginning of the war.

Training soldiers in the art of sniper shooting was widely developed in the units and formations being formed on the territory of the Siberian and Western Military Districts. It was carried out both during everyday combat training and during special events. In all regiments, sniper teams were created from among trained snipers, and a competition of marksmanship masters was organized. Sniper companies of units participated in district sniper competitions. For high examples of excellent use of weapons, soldiers were awarded the “Excellent Shooting” and “Sniper” badges.

To train commanders of sniper squads, excellent shooters, tank destroyers, machine gunners, submachine gunners and mortarmen, the 3rd and 5th separate training rifle brigades were formed in the Siberian Military District in August 1942. In December 1942, the formation of the 15th, 16th and 17th district sniper training schools began in the Siberian Military District, and the 25th and 26th district sniper training schools began in the Western Front. The dissertation author analyzed the organizational and staffing structure of formed formations and sniper schools. Their high material support is noted - the staff of schools and regiments had combat and training rifles, carbines, anti-tank rifles, light and heavy machine guns, etc. Training rifle formations and sniper schools were staffed mainly by conscripts from the Siberian regions with at least 5 classes of education, having completed sniper training in the special forces of Vsevobuch and passed the tests with “good” and “excellent”. The duration of training in sniper schools was 6 months.

The command of the Siberian Military District and the Western Front paid great attention to the selection and improvement of the educational and methodological skills of commanders of all levels. Mainly career officers, mainly front-line soldiers, were appointed to the positions of command and control staff of schools. The special and methodological knowledge of the commanding staff was improved during educational and methodological training sessions and classes.

In order to develop high moral and combat qualities of cadets in Siberian sniper schools, up to 80% of the training time was devoted to field training; front-line experience, including school graduates, was introduced into the learning process. Army newspapers have repeatedly taken the initiative to organize a movement of marksmanship masters. Graduates of sniper schools and training units were appointed to the positions of squad commanders in the active army, as well as in training and reserve rifle units and formations.

Fifth section “Training of flight technical personnel of the Air Force” dedicated to the preparation of aviation reserves. From the second half of July 1941, the formation of the 5th and 20th reserve fighter aviation regiments began in the SibVO, and the 23rd bomber and 24th fighter reserve aviation regiments in the ZabVO.

The reserve aviation regiments were staffed by flight personnel from combat units, reserve aviation schools of the Air Force, graduates of aviation schools and courses, and reserve specialists. In 1942, the 5th fighter and 9th reserve aviation brigades were formed in the Siberian Military District. The reserve aviation units of the Siberian Military District and the Western Front trained marching aviation regiments, single pilots and technical personnel for the Pe-2, LAGG-3, YAK-7 aircraft and its modifications. The main task of the 9th Reserve Aviation Brigade was to receive and send to the front aircraft supplied under Lend-Lease.

The training of flight personnel was complicated by the simultaneous mastering of new types of aircraft by permanent and variable personnel, short retraining periods, slow arrival of new equipment, difficult weather conditions, frequent fuel shortages, servicing operational flights of the Air Force and providing assistance to aircraft factories in refining and sending aircraft to the front. The training time for aviation regiments varied and was determined by the combat experience of arriving pilots, knowledge of new types of aircraft before arriving at the regiment, and the coherence of the flight crew. With the completion of the retraining program, the aviation regiments received new equipment and departed for the front.

Military innovators and inventors made a great contribution to the successful solution of the tasks facing the regiments. Thanks to their tireless work, visual images were created teaching aids from failed units, equipped classrooms, engine resources and fuel were saved, and training aircraft were improved.

In order to quickly master the new technology by permanent and variable flight personnel aviation technology various forms and methods of educational work were used: exchange of combat experience with pilots of regiments arriving from the front; technical conferences with the participation of aircraft designers. Front-line internships for command and instruction personnel, etc., contributed to improving the quality of aviation personnel training.

In the second chapter “Training of officers in military colleges and schools” the structure and effectiveness of the system for training command personnel in the Siberian Military District and the Western Front are analyzed on the eve and during the Great Patriotic War, the main problems and difficulties faced by the command of military districts, military units and institutions in solving the problems of training and retraining of command personnel are shown.

The first section of this chapter, “Organization of the training system for command personnel on the eve and during the initial period of the Great Patriotic War,” examines the main features of the activities of military educational institutions on the eve of and with the beginning of the war.

This material is in response to the article by Johnny Mnemonic

If we objectively consider the position of the army at the time of the death of the Russian Empire, a sad picture easily emerges. There is a myth about officers tsarist army. This will be somewhat surprising, but, in my opinion, it was created primarily by Soviet propaganda. In the heat of the class struggle, “gentlemen officers” were portrayed as rich, well-groomed and, as a rule, dangerous enemies, the antipodes of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army in general and its command staff in particular. This was especially evident in the film “Chapaev”, where instead of Kolchak’s rather poorly dressed and trained troops, Chapaev was confronted by the “Kappelites” in clean black and white uniforms, advancing in a “psychic” attack in a beautiful formation. According to high income, training was also assumed, and as a consequence, a high level of training and skills. All this was picked up and developed by fans of “The Russia We Lost” and the White Cause. Despite the fact that among them there are, of course, talented historians and simply amateurs military history Often the praise of officers reached the point of absurdity.

In fact, the situation with the combat training of officers was initially sad. And not the least role in this was played by the rather difficult financial situation of the officers. Roughly speaking, best students gymnasiums simply did not want to “pull the burden” in the service of an officer, when much simpler and more profitable career prospects in the civilian field opened up before them. It is no coincidence that the future Marshal of the Soviet Union, and at the beginning of the 20th century, cadet Boris Mikhailovich Shaposhnikov, wrote in his memoirs:

« Of course, it was difficult for my then comrades to understand my decision to go to military school. The fact is that I graduated from a real school, as noted above, with an average score of 4.3. With this score they usually entered higher technical educational institutions. In general, young people with weak theoretical training went to military schools. At the threshold of the 20th century, such an opinion about the command staff of the army was quite common."Boris Mikhailovich himself joined the army because" My parents lived very frugally, because my younger sister Yulia also started studying in Chelyabinsk at a girls’ gymnasium. I had to think more than once about the questions: how can I make life easier for my family? More than once the thought came to mind: “Should I go to military service? Secondary education would allow one to enter directly into a military school. I couldn’t even dream of studying at a higher technical institution for five years at my parents’ expense. Therefore, I have already, privately, firmly decided to go along the military line.»

Contrary to the cliche about officers as noble landowners, in fact, officers at the end of the Romanov era, although they came, as a rule, from nobles, financial situation were close to the commoners.

« Availability land ownership even among the generals and, oddly enough, the guards, this was far from a frequent occurrence. Let's look at the numbers. Of the 37 corps commanders (36 army and one guards), data regarding land ownership is available on 36. Of these, five had it. The largest landowner was the commander of the Guards Corps, General. V.M. Bezobrazov, who owned an estate of 6 thousand dessiatines and gold mines in Siberia. Of the remaining four, one had no indication of the size of his estate, and each of the three had about one thousand dessiatines. Thus, in the highest command category, with the rank of general, only 13.9% had land ownership.

Of the 70 heads of infantry divisions (67 army and 3 guards), as well as 17 cavalry divisions (15 army and two guards), i.e. 87 people, 6 people have no information about property. Of the remaining 81, only five have it (two guards generals, who were large landowners, and three army generals, two of whom had estates, and one had his own house). Consequently, 4 people, or 4.9%, had land ownership.

Let's turn to the regiment commanders. As mentioned above, we analyze all the grenadier and rifle regiments, and half of the infantry regiments that were part of the divisions. This amounted to 164 infantry regiments, or 61.1% of them total number. In addition, 48 cavalry (hussars, lancers and dragoons) regiments, which were part of 16 cavalry divisions, are considered.” If we compare these figures with similar ones for civil officials of the same classes, we get the following: “Let us turn to the list of civil ranks of the first three classes. In 1914, there were 98 second-class officials, of which 44 owned land property, which was 44.9%; third class - 697 people, of which 215 people owned property, which was 30.8%.

Let us compare data on the availability of land ownership among military and civilian officials of the corresponding classes. So, we have: second class ranks - military - 13.9%, civilians - 44.8%; third class - military - 4.9%, civilians - 30.8%. The difference is colossal.»

About the financial situation P.A. Zayonchkovsky writes: “ So, the officer corps, which included up to 80% of the nobles, consisted of the serving nobility and in terms of financial status was no different from the commoners"Quoting Protopresbyter Shavelsky, the same author writes:

« The officer was an outcast from the royal treasury. It is impossible to indicate a class in Tsarist Russia that was worse off than the officers. The officer received a meager salary that did not cover all his urgent expenses /.../. Especially if he had a family, eked out a miserable existence, was malnourished, entangled in debt, denying himself the most necessary things.»

As we have already seen, land holdings Even among the highest command staff there was no comparison with that among civilian officials. This was partly a consequence of the fact that the salaries of officials were significantly higher than that of generals: “ As mentioned above, the annual salary of the division chief was 6,000 rubles, and the governor’s salary was from 9,600 thousand to 12.6 thousand rubles per year, i.e. almost twice as much.“Only the guardsmen lived lavishly. General Ignatiev colorfully, although perhaps somewhat tendentiously, describes his service in perhaps the most elite regiment of the army Russian Empire- Life Guards Cavalry Regiment. He notes the enormous “cost” of serving in this regiment, which was associated with the cost of uniforms, two particularly expensive horses, etc. However, P.A. Zayonchkovsky believes that even this was not the most “expensive” regiment. He considers this to be the Life Guards Hussar Regiment, during service in which he had to spend 500 rubles a month - the salary of the division chief! In general, the Guard was a completely separate corporation, the existence of which brought great confusion to the career growth of officers.

On the one hand, the guard was staffed by the best graduates of schools. To do this, you had to get a “guards score” (more than 10 out of 12). Moreover, thanks to the system in which graduates chose their vacancies in order of average scores, the best cadets entered the guard. On the other hand, vacancies in the guard were available only in elite educational institutions. For example, it was almost impossible for a non-nobleman to get into the most elite Corps of Pages. Already fourth on the semi-official list of the most prestigious schools, Aleksandrovskoe always had a minimum of guards vacancies, and therefore Tukhachevsky was very lucky in that he was able to graduate as the best among the cadets. Thus, the already closed nature of the schools, which had a significant number of vacancies, greatly limited the entry of unborn cadets there.

However, this was not the last obstacle to getting into the guard. According to an unspoken law, but firmly followed and noted by many researchers: joining the regiment must be approved by the officers of the regiment. This closeness and casteism could block the path up the career ladder for any “freethinker,” since loyal feelings were mandatory for service in the guard. Finally, we have already talked about the “property qualification”. Thus, first of all, rich, well-born officers ended up in the guard. True, they had to complete the school course with excellence, but most equally, if not more talented officers did not even have the opportunity to join the guards regiment. But the guard was the “forge of personnel” for the generals of the tsarist army! Moreover, promotion in the guard was, in principle, faster and easier. Not only did the guardsmen have a 2-rank advantage over army officers, but there was also no rank of lieutenant colonel, which further accelerated growth. We are no longer talking about connections and prestige! As a result, most of the generals came from the Guard; moreover, most of the generals who did not have an education at the General Staff Academy came from there.

Eg " in 1914, the army had 36 army corps and 1 guard corps. ... Let us turn to the data on education. Of the 37 corps commanders, 34 had higher military education. Of these, 29 people graduated from the General Staff Academy, 2 from the Artillery Academy, and 1 from the Engineering and Legal Academy. Thus, 90% had a higher education. The three who did not have higher education included the commander of the Guards Corps, General. V.M. Bezobrazov, 12th Army Corps General. A.A. Brusilov and the 2nd Caucasian Corps, General. G.E. Berkhman. Of the listed corps commanders, 25 people in the past, and one (General Bezobrazov) currently served in the guard.»

It is difficult to agree with the author that this was explained solely by the “ability” of the guards. After all, it was they who first of all got to the highest positions, without having an education from the Academy of the General Staff, which the author himself admits: “ According to the “Schedule” of 1914, the Russian army consisted of 70 infantry divisions: 3 guards, 4 grenadiers, 52 infantry and 11 Siberian rifle divisions. Their commanders were lieutenant generals... By education: 51 people had higher military education (46 of them graduated from the General Staff Academy, 41 graduated from the Military Engineering Academy, 1 from the Artillery Academy). Thus, 63.2% had higher education. Of the 70 commanders of infantry divisions, 38 were guardsmen (past or present). It is interesting to note that of the 19 people who did not have a higher military education, 15 were guards officers. The guards' advantage was already showing here.“As you can see, the “guards advantage” affects the level of division commanders. Where does it go when the same people are appointed to the slightly higher post of corps chief? Moreover, for some unknown reason, the author was mistaken about G.E. Berkhman’s lack of higher education, and the rest of the generals were precisely from the guard. Bezobrazov, who did not have a higher education, but was very rich, generally commanded the Guards Corps. Thus, the guard was a “supplier” of academically uneducated officers to the highest echelons of the army.

We can talk about such a serious problem as the lack of fairness in the distribution of ranks and positions: richer and more well-born officers, once in the guard, had a much better chance of making a career than those who pulled the burden and were sometimes more prepared (if only because of less ceremonial conditions of service) army colleagues. This could not but affect the quality of training of senior command staff or the psychological climate. It is known that division into “castes” reigned in the army. As already mentioned, guardsmen were allocated to a special group, having significant preferences among all officers. But it cannot be said that there were no frictions and differences within the guard and the rest of the army. Thus, the most educated officers traditionally served in the engineering troops and artillery. This was even reflected in jokes: “a handsome man serves in the cavalry, a smart man serves in the artillery, a drunkard serves in the navy, and a fool serves in the infantry.” The least prestigious was, of course, the infantry. And the “aristocratic” cavalry was considered the most prestigious. However, she also shared. So the hussars and lancers looked down on the dragoons. The 1st Heavy Brigade of the Guards Cavalry stood apart: the “courtiers” of the Cavalry Guards and the Life Guards Horse Regiment, “fought” for the title of the most elite regiment. In the foot guards, the so-called "Petrovskaya Brigade" - Preobrazhensky and Semenovsky regiments. But, as Minakov notes, even here there was no equality: Preobrazhensky was more well-born. In the artillery, the cavalry was considered the elite, but the serfs were traditionally considered “outcasts,” which came back to haunt them in 1915 during the defense of fortresses. Of course, it cannot be said that such differences do not exist in other armies, but there was nothing good in separating and isolating different types of troops from each other.

Almost the only opportunity to accelerate career growth for talented army officers was admission to the Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff. The selection there was very careful. To do this, it was necessary to pass preliminary exams, and then entrance exams. At the same time, the best officers of the regiments initially surrendered them. According to Shaposhnikov, in the year of his admission, 82.6% of those who passed the preliminary exams passed the competition. However, despite such a careful selection of applicants, applicants had serious problems with general education subjects. " 1) Very poor literacy, gross spelling errors. 2) Poor overall development. Bad style. Lack of clarity of thinking and general lack of mental discipline. 3) Extremely poor knowledge of history and geography. Insufficient literary education“However, one cannot say that this applied to all General Staff officers. Using the example of B.M. Shaposhnikov, it is easy to see that many of them did not have even a shadow of the problems mentioned above in the document. However, it should be noted that subsequent problems with education in the Red Army were radically different from similar ones in the tsarist army. The image of a well-educated tsarist officer is fairly idealized.

Training at the General Staff Academy lasted two years. In the first year, both military and general education subjects were covered, while military officers mastered disciplines related to the combat operations of units. In the second year, general education subjects were completed, and disciplines related to strategy were studied from the military. In addition, every day there were horse riding lessons in the arena. As Shaposhnikov notes, this was a consequence of experience Russian- Japanese war, when the division during the battles near the Yantai Mines, Orlov's division scattered, ending up in a high kaoliang, when the chief of staff's horse bolted and he could not stop it, leaving the division completely beheaded, since the division commander was wounded. Perhaps this was already unnecessary for the positional massacre of the First World War, but in response to the critical remark of Boris Mikhailovich himself about the archaic nature of the horse as a method of transportation compared to the automobile introduced in Europe, we note that Russian industry simply did not have the ability to supply the army with a sufficient amount of transport. Buying it abroad was expensive and quite reckless from the point of view of independence from foreign supplies.

The training itself also had significant shortcomings. For example, many authors note little attention to the development of initiative and practical skills in general. Classes consisted almost exclusively of lectures. The end result, instead of highly qualified staff workers, was theoreticians who did not always have an idea of how to act in a real situation. According to Ignatiev, only one teacher even focused on the will to win.

Another problem was the enormous amount of time spent on some completely outdated items, such as drawing the terrain in line drawings. In general, this art was such a memorable subject that many memoirists write unkind words about it. ,

Contrary to the well-known myth about the generals’ passion for the French school of Grandmaison, “élan vitale”6, Shaposhnikov testifies to his sympathy for German theories. True, he notes that the top generals were not familiar with German methods of war.

In general, the strengths of the career officers of the tsarist army were their fighting spirit and readiness for self-sacrifice. And there could be no talk of carelessness like conversations about absolutely secret things in a cafe, which Shaposhnikov describes in “The Brain of the Army” in relation to the Austrian army. The concept of an officer’s honor was worth a lot to career military personnel. Young officers of the General Staff, after the reforms carried out by Golovin, received a generally good education, despite many shortcomings. What was especially important was that the tactics of the German troops were no longer a revelation to them, as they were to more senior commanders. The problem of the latter was a weak interest in self-development, in innovations both in technology and in the art of war. As A.M. Zayonchkovsky notes, the disastrous situation with the training of senior command personnel was partly a consequence of the General Staff’s inattention to the problem: