This issue is made on the basis of the three-volume “ military history” Razin and the book “On the Seven Hills” by M.Yu. German, B.P. Seletsky, Yu.P. Suzdalsky. The issue is not a special historical study and is intended to help those involved in the manufacture of military miniatures.

Brief historical background

Ancient Rome is a state that conquered the peoples of Europe, Africa, Asia, Britain. Roman soldiers were famous all over the world for their iron discipline (but not always it was iron), brilliant victories. The Roman generals went from victory to victory (there were also cruel defeats), until all the peoples of the Mediterranean were under the weight of a soldier's boot.

The Roman army at different times had different numbers, the number of legions, various formations. With the improvement of military art, weapons, tactics and strategy changed.

In Rome, there was universal conscription. Young men began to serve in the army from the age of 17 and up to 45 in field units, after 45 to 60 they served in fortresses. Persons who participated in 20 campaigns in the infantry and 10 in the cavalry were exempted from service. Service life also changed over time.

At one time, due to the fact that everyone wanted to serve in light infantry (weapons were cheap, they were purchased at their own expense), the citizens of Rome were divided into ranks. This was done under Servius Tullius. The 1st category included people who possessed property, which was estimated at no less than 100,000 copper asses, the 2nd - at least 75,000 asses, the 3rd - 50,000 asses, the 4th - 25,000 asses, the 5 -mu - 11.500 ass. All the poor were included in the 6th category - proletarians, whose wealth was only offspring ( proles). Each property category exhibited a certain number of military units - centuries (hundreds): 1st category - 80 centuries of heavy infantry, which were the main fighting force, and 18 centuries of horsemen; a total of 98 centuries; 2nd - 22; 3rd - 20; 4th - 22; 5th - 30 centuries of lightly armed and 6th category - 1 century, a total of 193 centuries. Lightly armed warriors were used as convoy servants. Thanks to the division into ranks, there was no shortage of heavily armed, lightly armed foot soldiers and horsemen. Proletarians and slaves did not serve because they were not trusted.

Over time, the state took over not only the maintenance of the warrior, but also withheld from him from the salary for food, weapons and equipment.

After a severe defeat at Cannes and in a number of other places, after the Punic Wars, the army was reorganized. Salaries were sharply increased, and proletarians were allowed to serve in the army.

Continuous wars required many soldiers, changes in weapons, formation, training. The army became mercenary. Such an army could be led anywhere and against anyone. This is what happened when Lucius Cornellius Sulla (1st century BC) came to power.

Organization of the Roman army

After victorious wars IV-III centuries BC. All the peoples of Italy fell under the rule of Rome. To keep them in obedience, the Romans gave some nations more rights, others less, sowing mutual distrust and hatred between them. It was the Romans who formulated the law “divide and rule”.

And for this, numerous troops were needed. Thus, the Roman army consisted of:

a) legions in which the Romans themselves served, consisting of heavy and light infantry and cavalry attached to them;

b) Italian allies and allied cavalry (after granting citizenship rights to Italians who joined the legion);

c) auxiliary troops recruited from the inhabitants of the provinces.

The main tactical unit was the legion. At the time of Servius Tullius, the legion numbered 4,200 men and 900 cavalry, not counting the 1,200 lightly armed soldiers who were not part of the legion's line-up.

Consul Mark Claudius changed the order of the legion and weapons. This happened in the 4th century BC.

The legion was divided into maniples (in Latin - a handful), centuriae (hundreds) and decuria (tens), which resembled modern companies, platoons, squads.

Light infantry - velites (literally - fast, mobile) went ahead of the legion in a loose storyu and started a fight. In case of failure, she retreated to the rear and to the flanks of the legion. In total there were 1200 people.

Hastati (from the Latin "hasta" - spear) - spearmen, 120 people in a maniple. They formed the first line of the legion. Principles (first) - 120 people in the maniple. Second line. Triaria (third) - 60 people in the maniple. Third line. The triarii were the most experienced and experienced fighters. When the ancients wanted to say that the decisive moment had come, they said: "It came to the triarii."

Each maniple had two centuries. There were 60 people in the centurion of hastati or principes, and there were 30 people in the centurion of triarii.

The legion was given 300 horsemen, which amounted to 10 tours. The cavalry covered the flanks of the legion.

At the very beginning of the application of the manipulative order, the legion went into battle in three lines, and if an obstacle was encountered that the legionnaires were forced to flow around, this resulted in a break in the battle line, the maniple from the second line hurried to close the gap, and the place of the maniple from the second line was occupied by the maniple from the third line . During the fight with the enemy, the legion represented a monolithic phalanx.

Over time, the third line of the legion began to be used as a reserve, deciding the fate of the battle. But if the commander incorrectly determined the decisive moment of the battle, the legion was waiting for death. Therefore, over time, the Romans switched to the cohort system of the legion. Each cohort numbered 500-600 people and, with an attached cavalry detachment, acting separately, was a legion in miniature.

Commanding staff of the Roman army

AT tsarist time the king was in command. In the days of the republic, the consuls commanded, dividing the troops in half, but when it was necessary to unite, they commanded in turn. If there was a serious threat, then a dictator was chosen, to whom the head of the cavalry was subordinate, in contrast to the consuls. The dictator had unlimited rights. Each commander had assistants who were entrusted with individual parts of the army.

Individual legions were commanded by tribunes. There were six of them per legion. Each pair commanded for two months, replacing each other every day, then giving up their place to the second pair, and so on. The centurions were subordinate to the tribunes. Each centuria was commanded by a centurion. The commander of the first hundred was the commander of the maniple. The centurions had the right of a soldier for misdemeanors. They carried with them a vine - a Roman rod, this tool was rarely left idle. The Roman writer Tacitus spoke of one centurion, whom the whole army knew under the nickname: “Pass another!” After the reform of Marius, an associate of Sulla, the centurions of the triarii received big influence. They were invited to the military council.

As in our time, the Roman army had banners, drums, timpani, pipes, horns. The banners were a spear with a crossbar, on which a banner made of a single-color material hung. The maniples, and after the reform of Maria the cohorts, had banners. Above the crossbar there was an image of an animal (a wolf, an elephant, a horse, a boar…). If the unit performed a feat, then it was awarded - the award was attached to the flagpole; this custom has been preserved to this day.

The badge of the legion under Mary was a silver eagle or a bronze one. Under the emperors, it was made of gold. The loss of the banner was considered the greatest shame. Each legionnaire had to defend the banner to the last drop of blood. In a difficult moment, the commander threw the banner into the midst of enemies to encourage the soldiers to return it back and scatter the enemies.

The first thing the soldiers were taught was to relentlessly follow the badge, the banner. The standard-bearers were selected from strong and experienced soldiers and enjoyed great honor and respect.

According to the description of Titus Livius, the banners were a square cloth, laced to a horizontal bar, mounted on a pole. The color of the cloth was different. They were all monochromatic - purple, red, white, blue.

Until the allied infantry merged with the Romans, it was commanded by three prefects, chosen from among Roman citizens.

Great importance was attached to the quartermaster service. The head of the commissary service is the quaestor, who was in charge of fodder and food for the army. He oversaw the delivery of everything needed. In addition, each centuria had its own foragers. A special official, as a captain in modern army distributing food to the soldiers. At the headquarters there was a staff of scribes, bookkeepers, cashiers who gave out salaries to soldiers, priests-fortunetellers, military police officials, spies, signal trumpeters.

All signals were given by a pipe. The sound of the trumpet was rehearsed with curved horns. At the changing of the guard, they blew a fucina trumpet. The cavalry used a special long pipe, curved at the end. The signal to assemble the troops for the general meeting was given by all the trumpeters gathered in front of the commander's tent.

Training in the Roman army

The training of the fighters of the Roman manipulative legion, first of all, was to learn the soldiers to go forward on the orders of the centurion, to fill gaps in the battle line at the moment of collision with the enemy, to hasten to merge into the general mass. The execution of these maneuvers required more complex training than in the training of a warrior who fought in the phalanx.

The training also consisted in the fact that the Roman soldier was sure that he would not be left alone on the battlefield, that his comrades would rush to his aid.

The appearance of legions divided into cohorts, the complication of maneuver required more complex training. It is no coincidence that after the reform of Marius, one of his associates, Rutilius Rufus, introduced a new training system in the Roman army, reminiscent of the training system for gladiators in gladiatorial schools. Only well-trained soldiers (trained) could overcome fear and get close to the enemy, attack from the rear on a huge mass of the enemy, feeling only a cohort nearby. Only a disciplined soldier could fight like that. Under Mary, a cohort was introduced, which included three maniples. The legion had ten cohorts, not counting the light infantry, and between 300 and 900 cavalry.

|

|

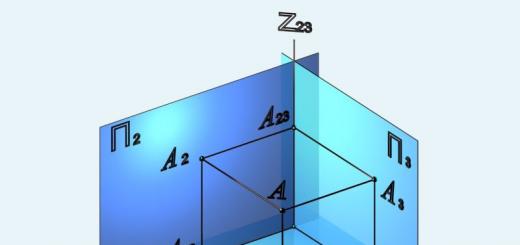

Fig. 3 - Cohort battle order. |

Discipline

The Roman army, famous for its discipline, unlike other armies of that time, was entirely in the power of the commander.

The slightest violation of discipline was punishable by death, as well as failure to comply with the order. So, in 340 BC. the son of the Roman consul Titus Manlius Torquata, during reconnaissance without the order of the commander-in-chief, entered into battle with the head of the enemy detachment and defeated him. He talked about this in the camp with enthusiasm. However, the consul condemned him to death. The sentence was carried out immediately, despite the pleas of the entire army for mercy.

Ten lictors always walked in front of the consul, carrying bundles of rods (fascia, fascines). AT war time an ax was inserted into them. The symbol of the consul's authority over his subordinates. First, the offender was flogged with rods, then they cut off their heads with an ax. If part or all of the army showed cowardice in battle, then decimation was carried out. Decem translated into Russian means ten. This is what Crassus did after the defeat of several legions by Spartacus. Several hundred soldiers were flogged and then executed.

If a soldier fell asleep at his post, he was put on trial and then beaten to death with stones and sticks. For minor infractions, they could be flogged, demoted, transferred to hard work, reduced salaries, deprived of citizenship, sold into slavery.

But there were also awards. They could be promoted in rank, increase salaries, rewarded with land or money, freed from camp work, awarded with insignia: silver and gold chains, bracelets. The award was given by the commander himself.

The usual awards were medals (falers) depicting the face of a god or a commander. Wreaths (crowns) were the highest insignia. Oak was given to a soldier who saved a comrade - a Roman citizen in battle. A crown with a battlement - to the one who first climbed the wall or rampart of an enemy fortress. A crown with two golden prows of ships, to the soldier who was the first to step onto the deck of an enemy ship. The siege wreath was given to the commander who lifted the siege from the city or fortress or liberated them. But the most high reward- a triumph - was given to the commander for an outstanding victory, while at least 5,000 enemies had to be killed.

The victor rode in a gilded chariot, robed in purple and embroidered with palm leaves. The chariot was drawn by four white horses. War booty was carried in front of the chariot and prisoners were led. Relatives and friends, songwriters, soldiers followed the victor. There were triumphal songs. Every now and then the cries of “Io!” and "Triumph!" (“Io!” corresponds to our “Hurrah!”). The slave standing behind the victor on the chariot reminded him that he was a mere mortal and that he should not be arrogant.

For example, the soldiers of Julius Caesar, who were in love with him, followed him, joking and laughing at his baldness.

Roman camp

The Roman camp was well thought out and fortified. The Roman army was said to drag the fortress behind them. As soon as a halt was made, the construction of the camp immediately began. If it was necessary to move on, the camp was abandoned unfinished. Even broken for a short time, it differed from the one-day one by more powerful fortifications. Sometimes the army stayed in the camp for the winter. Such a camp was called a winter camp; houses and barracks were built instead of tents. By the way, on the site of some Roman tagers, cities such as Lancaster, Rochester and others arose. Cologne (the Roman colony of Agripinna), Vienna (Vindobona) grew out of the Roman camps… Cities, at the end of which there is “…chester” or “…kastr”, arose on the site of Roman camps. "Castrum" - camp.

The place for the camp was chosen on the southern dry slope of the hill. Nearby there should have been water and pasture for cart cattle, fuel.

The camp was a square, later a rectangle, the length of which was one third longer than the width. First of all, the place of the praetorium was planned. This is a square area, the side of which was 50 meters. The commander's tents, altars, and a platform for addressing the commander's soldiers were set up here; it was here that the court and the gathering of troops took place. To the right was the quaestor's tent, to the left the legates' tent. On both sides were placed the tents of the tribunes. In front of the tents, a street 25 meters wide passed through the entire camp, the main street was crossed by another, 12 meters wide. There were gates and towers at the ends of the streets. They were equipped with ballistas and catapults. (the same throwing weapon, got its name from a projectile, a ballista, a metal core, a catapult - arrows). Legionnaires' tents stood in regular rows on either side. From the camp, the troops could set out on a campaign without hustle and disorder. Each centuria occupied ten tents, maniples twenty. The tents had a plank frame, a gable plank roof and were covered with leather or coarse linen. Tent area from 2.5 to 7 sq. m. The decuria lived in it - 6-10 people, two of whom were constantly on guard. The tents of the Praetorian Guard and the cavalry were large. The camp was surrounded by a palisade, a wide and deep ditch and a rampart 6 meters high. There was a distance of 50 meters between the ramparts and the tents of the legionnaires. This was done so that the enemy could not light the tents. An obstacle course was arranged in front of the camp from several countervailing lines and barriers from pointed stakes, wolf pits, trees with pointed branches and woven together, forming an almost impassable obstacle.

Greaves have been worn by Roman legionnaires since ancient times. Under the emperors they were abolished. But the centurions continued to wear them. Leggings had the color of the metal from which they were made, sometimes they were painted.

In the time of Marius the banners were silver, in the time of the empire they were gold. The cloths were multicolored: white, blue, red, purple.

|

|

Rice. 7 - Weapons. |

The cavalry sword is one and a half times longer than the infantry. The swords are single-edged, the handles were made of bone, wood, metal.

A pilum is a heavy spear with a metal tip and shaft. Serrated tip. Wooden tree. The middle part of the spear is wrapped tightly coil to coil with a cord. One or two tassels were made at the end of the cord. The tip of the spear and the rod were made of soft forged iron, up to iron - of bronze. The pilum was thrown at the enemy's shields. The spear that stuck into the shield pulled it to the bottom, and the warrior was forced to drop the shield, as the spear weighed 4-5 kg and dragged along the ground, as the tip and rod were bent.

|

|

Rice. 8 - Scutums (shields). |

Shields (scutums) acquired a semi-cylindrical shape after the war with the Gauls in the 4th century. BC e. Scutums were made from light, well-dried, aspen or poplar boards tightly fitted to each other, covered with linen, and on top with bull skin. Along the edge, the shields were bordered with a strip of metal (bronze or iron) and strips were placed in a cross through the center of the shield. In the center was placed a pointed plaque (umbon) - the pommel of the shield. Legionnaires kept in it (it was removable) a razor, money and other small things. On the inside there was a belt loop and a metal clip, the name of the owner and the number of the centurion or cohort were written. The skin could be dyed: red or black. The hand was pushed into the belt loop and taken by the bracket, thanks to which the shield hung tightly on the hand.

The helmet in the center is an earlier one, the one on the left is a later one. The helmet had three feathers 400 mm long; in ancient times, helmets were bronze, later iron. The helmet was sometimes decorated in the form of snakes on the sides, which at the top formed a place where feathers were inserted. In later times, the only decoration on the helmet was the crest. At the top of the Roman helmet was a ring through which a strap was threaded. The helmet was worn on the back or on the lower back, as a modern helmet is worn.

Roman velites were armed with javelins and shields. The shields were round, made of wood or metal. Velites were dressed in tunics, later (after the war with the Gauls) all legionnaires began to wear trousers. Some of the velites were armed with slings. The slingers had bags for stones on their right side, over the left shoulder. Some velites may have had swords. Shields (wooden) were covered with leather. The color of the clothes could be anything except purple and its shades. Velites could wear sandals or go barefoot. Archers in the Roman army appeared after the defeat of the Romans in the war with Parthia, where the consul Crassus and his son died. The same Crassus who defeated the troops of Spartacus under Brundisium.

|

Fig 12 - Centurion. |

The centurions had silver-plated helmets, no shields, and the sword was worn on the right side. They had leggings and, as a distinctive sign on the armor, on the chest they had the image of a vine folded into a ring. During the manipulative and cohort construction of the legions, the centurions were on the right flank of the centuries, maniples, cohorts. The cloak is red, and all the legionnaires wore red cloaks. Only the dictator and high commanders were allowed to wear purple cloaks.

Animal skins served as saddles. The Romans did not know stirrups. The first stirrups were rope loops. The horses were not forged. Therefore, the horses were very taken care of.

References

1. Military history. Razin, 1-2 vols., Moscow, 1987

2. On the seven hills (Essays on the culture of ancient Rome). M.Yu. German, B.P. Seletsky, Yu.P. Suzdal; Leningrad, 1960.

3. Hannibal. Titus Livius; Moscow, 1947.

4. Spartacus. Raffaello Giovagnoli; Moscow, 1985.

5. Flags of the states of the world. K.I. Ivanov; Moscow, 1985.

6. History of ancient Rome, under the general editorship of V.I. Kuzishina; Moscow, 1981.

Publication:

Library of the Military History Commission - 44, 1989

Ancient Rome is a state that conquered the peoples of Europe, Africa, Asia, Britain. Roman soldiers were famous all over the world for their iron discipline (but not always it was iron), brilliant victories. The Roman generals went from victory to victory (there were also cruel defeats), until all the peoples of the Mediterranean were under the weight of a soldier's boot.

The Roman army at different times had different numbers, the number of legions, and different formations. With the improvement of military art, weapons, tactics and strategy changed.

In Rome, there was universal conscription. Young men began to serve in the army from the age of 17 and up to 45 in field units, after 45 to 60 they served in fortresses. Persons who participated in 20 campaigns in the infantry and 10 in the cavalry were exempted from service. Service life also changed over time.

At one time, due to the fact that everyone wanted to serve in light infantry (weapons were cheap, they were purchased at their own expense), the citizens of Rome were divided into ranks. This was done under Servius Tullius. The 1st category included people who possessed property, which was estimated at no less than 100,000 copper asses, the 2nd - at least 75,000 asses, the 3rd - 50,000 asses, the 4th - 25,000 asses, the 5 -mu - 11.500 ass. All the poor were included in the 6th category - the proletarians, whose wealth was only offspring (proles). Each property category exhibited a certain number of military units - centuries (hundreds): 1st category - 80 centuries of heavy infantry, which were the main fighting force, and 18 centuries of horsemen; a total of 98 centuries; 2nd - 22; 3rd - 20; 4th - 22; 5th - 30 lightly armed centuries and 6th category - 1 century, in total 193 centuries. Lightly armed warriors were used as convoy servants. Thanks to the division into ranks, there was no shortage of heavily armed, lightly armed foot soldiers and horsemen. Proletarians and slaves did not serve because they were not trusted.

Over time, the state took over not only the maintenance of the warrior, but also withheld from him from the salary for food, weapons and equipment.

After a severe defeat at Cannes and in a number of other places, after the Punic Wars, the army was reorganized. Salaries were sharply increased, and proletarians were allowed to serve in the army.

Continuous wars required many soldiers, changes in weapons, formation, training. The army became mercenary. Such an army could be led anywhere and against anyone. This is what happened when Lucius Cornellius Sulla (1st century BC) came to power.

Organization of the Roman army

After the victorious wars of the IV-III centuries. BC. All the peoples of Italy fell under the rule of Rome. To keep them in obedience, the Romans gave some nations more rights, others less, sowing mutual distrust and hatred between them. It was the Romans who formulated the law “divide and rule”.

And for this, numerous troops were needed. Thus, the Roman army consisted of:

a) legions in which the Romans themselves served, consisting of heavy and light infantry and cavalry attached to them;

b) Italian allies and allied cavalry (after granting citizenship rights to Italians who joined the legion);

c) auxiliary troops recruited from the inhabitants of the provinces.

The main tactical unit was the legion. At the time of Servius Tullius, the legion numbered 4,200 men and 900 cavalry, not counting the 1,200 lightly armed soldiers who were not part of the legion's line-up.

Consul Mark Claudius changed the order of the legion and weapons. This happened in the 4th century BC.

The legion was divided into maniples (in Latin - a handful), centuriae (hundreds) and decuria (tens), which resembled modern companies, platoons, squads.

Fig.1 - The structure of the legion.

Fig.2 - Manipulative construction.

Light infantry - velites (literally - fast, mobile) went ahead of the legion in a loose storyu and started a fight. In case of failure, she retreated to the rear and to the flanks of the legion. In total there were 1200 people.

Hastati (from the Latin “gasta” - spear) - spearmen, 120 people in a maniple. They formed the first line of the legion. Principles (first) - 120 people in the maniple. Second line. Triaria (third) - 60 people in the maniple. Third line. The triarii were the most experienced and experienced fighters. When the ancients wanted to say that the decisive moment had come, they said: "It came to the triarii."

Each maniple had two centuries. There were 60 people in the centurion of hastati or principes, and there were 30 people in the centurion of triarii.

The legion was given 300 horsemen, which amounted to 10 tours. The cavalry covered the flanks of the legion.

At the very beginning of the application of the manipulative order, the legion went into battle in three lines, and if an obstacle was encountered that the legionnaires were forced to flow around, this resulted in a break in the battle line, the maniple from the second line hurried to close the gap, and the place of the maniple from the second line was occupied by the maniple from the third line . During the fight with the enemy, the legion represented a monolithic phalanx.

Over time, the third line of the legion began to be used as a reserve, deciding the fate of the battle. But if the commander incorrectly determined the decisive moment of the battle, the legion was waiting for death. Therefore, over time, the Romans switched to the cohort system of the legion. Each cohort numbered 500-600 people and, with an attached cavalry detachment, acting separately, was a legion in miniature.

Commanding staff of the Roman army

In tsarist times, the king was the commander. In the days of the republic, the consuls commanded, dividing the troops in half, but when it was necessary to unite, they commanded in turn. If there was a serious threat, then a dictator was chosen, to whom the head of the cavalry was subordinate, in contrast to the consuls. The dictator had unlimited rights. Each commander had assistants who were entrusted with individual parts of the army.

Individual legions were commanded by tribunes. There were six of them per legion. Each pair commanded for two months, replacing each other every day, then giving up their place to the second pair, and so on. The centurions were subordinate to the tribunes. Each centuria was commanded by a centurion. The commander of the first hundred was the commander of the maniple. The centurions had the right of a soldier for misdemeanors. They carried with them a vine - a Roman rod, this tool was rarely left idle. The Roman writer Tacitus spoke of one centurion, whom the whole army knew under the nickname: “Pass another!” After the reform of Marius, an associate of Sulla, the centurions of the Triarii gained great influence. They were invited to the military council.

As in our time, the Roman army had banners, drums, timpani, pipes, horns. The banners were a spear with a crossbar, on which a banner made of a single-color material hung. The maniples, and after the reform of Maria the cohorts, had banners. Above the crossbar there was an image of an animal (a wolf, an elephant, a horse, a boar…). If the unit performed a feat, then it was awarded - the award was attached to the flagpole; this custom has been preserved to this day.

The badge of the legion under Mary was a silver eagle or a bronze one. Under the emperors, it was made of gold. The loss of the banner was considered the greatest shame. Each legionnaire had to defend the banner to the last drop of blood. In a difficult moment, the commander threw the banner into the midst of enemies to encourage the soldiers to return it back and scatter the enemies.

The first thing the soldiers were taught was to relentlessly follow the badge, the banner. The standard-bearers were selected from strong and experienced soldiers and enjoyed great honor and respect.

According to the description of Titus Livius, the banners were a square cloth, laced to a horizontal bar, mounted on a pole. The color of the cloth was different. All of them were monophonic - purple, red, white, blue.

Until the allied infantry merged with the Romans, it was commanded by three prefects, chosen from among Roman citizens.

Great importance was attached to the quartermaster service. The head of the quartermaster service is the quaestor, who was in charge of fodder and food for the army. He oversaw the delivery of everything needed. In addition, each centuria had its own foragers. A special official, like a captain in the modern army, distributed food to the soldiers. At the headquarters there was a staff of scribes, bookkeepers, cashiers who gave out salaries to soldiers, priests-fortunetellers, military police officials, spies, signal trumpeters.

All signals were given by a pipe. The sound of the trumpet was rehearsed with curved horns. At the changing of the guard, they blew a fucina trumpet. The cavalry used a special long pipe, curved at the end. The signal to assemble the troops for the general meeting was given by all the trumpeters gathered in front of the commander's tent.

Training in the Roman army

The training of the fighters of the Roman manipulative legion, first of all, was to learn the soldiers to go forward on the orders of the centurion, to fill gaps in the battle line at the moment of collision with the enemy, to hasten to merge into the general mass. The execution of these maneuvers required more complex training than in the training of a warrior who fought in the phalanx.

The training also consisted in the fact that the Roman soldier was sure that he would not be left alone on the battlefield, that his comrades would rush to his aid.

The appearance of legions divided into cohorts, the complication of maneuver required more complex training. It is no coincidence that after the reform of Marius, one of his associates, Rutilius Rufus, introduced a new training system in the Roman army, reminiscent of the training system for gladiators in gladiatorial schools. Only well-trained soldiers (trained) could overcome fear and get close to the enemy, attack from the rear on a huge mass of the enemy, feeling only a cohort nearby. Only a disciplined soldier could fight like that. Under Mary, a cohort was introduced, which included three maniples. The legion had ten cohorts, not counting the light infantry, and between 300 and 900 cavalry.

Discipline

The Roman army, famous for its discipline, unlike other armies of that time, was entirely in the power of the commander.

The slightest violation of discipline was punishable by death, as well as failure to comply with the order. So, in 340 BC. the son of the Roman consul Titus Manlius Torquata, during reconnaissance without the order of the commander-in-chief, entered into battle with the head of the enemy detachment and defeated him. He talked about this in the camp with enthusiasm. However, the consul condemned him to death. The sentence was carried out immediately, despite the pleas of the entire army for mercy.

Ten lictors always walked in front of the consul, carrying bundles of rods (fascia, fascines). In wartime, an ax was inserted into them. The symbol of the consul's authority over his subordinates. First, the offender was flogged with rods, then they cut off their heads with an ax. If part or all of the army showed cowardice in battle, then decimation was carried out. Decem translated into Russian means ten. This is what Crassus did after the defeat of several legions by Spartacus. Several hundred soldiers were flogged and then executed.

If a soldier fell asleep at his post, he was put on trial and then beaten to death with stones and sticks. For minor infractions, they could be flogged, demoted, transferred to hard work, reduced salaries, deprived of citizenship, sold into slavery.

But there were also awards. They could be promoted in rank, increase salaries, rewarded with land or money, freed from camp work, awarded with insignia: silver and gold chains, bracelets. The award was given by the commander himself.

The usual awards were medals (falers) depicting the face of a god or a commander. Wreaths (crowns) were the highest insignia. Oak was given to a soldier who saved a comrade - a Roman citizen in battle. A crown with a battlement - to the one who first climbed the wall or rampart of an enemy fortress. A crown with two golden noses of ships - to the soldier who was the first to step on the deck of an enemy ship. The siege wreath was given to the commander who lifted the siege from the city or fortress or liberated them. But the highest award - a triumph - was given to the commander for an outstanding victory, while at least 5,000 enemies were to be killed.

The victor rode in a gilded chariot, robed in purple and embroidered with palm leaves. The chariot was drawn by four white horses. War booty was carried in front of the chariot and prisoners were led. Relatives and friends, songwriters, soldiers followed the victor. There were triumphal songs. Every now and then the cries of “Io!” and "Triumph!" (“Io!” corresponds to our “Hurrah!”). The slave standing behind the victor on the chariot reminded him that he was a mere mortal and that he should not be arrogant.

For example, the soldiers of Julius Caesar, who were in love with him, followed him, joking and laughing at his baldness.

Roman camp

The Roman camp was well thought out and fortified. The Roman army was said to drag the fortress behind them. As soon as a halt was made, the construction of the camp immediately began. If it was necessary to move on, the camp was abandoned unfinished. Even broken for a short time, it differed from the one-day one by more powerful fortifications. Sometimes the army stayed in the camp for the winter. Such a camp was called a winter camp; houses and barracks were built instead of tents. By the way, on the site of some Roman tagers, cities such as Lancaster, Rochester and others arose. Cologne (the Roman colony of Agripinna), Vienna (Vindobona) grew out of the Roman camps… Cities, at the end of which there is “…chester” or “…kastr”, arose on the site of Roman camps. "Castrum" - camp.

The place for the camp was chosen on the southern dry slope of the hill. Nearby there should have been water and pasture for cart cattle, fuel.

The camp was a square, later a rectangle, the length of which was one third longer than the width. First of all, the place of the praetorium was planned. This is a square area, the side of which was 50 meters. The commander's tents, altars, and a platform for addressing the commander's soldiers were set up here; it was here that the court and the gathering of troops took place. To the right was the quaestor's tent, to the left the legates' tent. On both sides were placed the tents of the tribunes. In front of the tents, a street 25 meters wide passed through the entire camp, the main street was crossed by another, 12 meters wide. There were gates and towers at the ends of the streets. They were equipped with ballistae and catapults (the same throwing weapon, got its name from the projectile, the ballista threw the cannonballs, the catapult - arrows). Legionnaires' tents stood in regular rows on either side. From the camp, the troops could set out on a campaign without hustle and disorder. Each centuria occupied ten tents, maniples - twenty. The tents had a plank frame, a gable plank roof and were covered with leather or coarse linen. Tent area from 2.5 to 7 sq. m. The decuria lived in it - 6-10 people, two of whom were constantly on guard. The tents of the Praetorian Guard and the cavalry were large. The camp was surrounded by a palisade, a wide and deep ditch and a rampart 6 meters high. There was a distance of 50 meters between the ramparts and the tents of the legionnaires. This was done so that the enemy could not light the tents. An obstacle course was arranged in front of the camp from several countervailing lines and barriers from pointed stakes, wolf pits, trees with pointed branches and woven together, forming an almost impassable obstacle.

There were no socks on sandals and boots (kaligas). The skin was red.

Greaves have been worn by Roman legionnaires since ancient times. Under the emperors they were abolished. But the centurions continued to wear them. Leggings had the color of the metal from which they were made, sometimes they were painted.

Rice. 6 - Banners.

1. Banner of the Legion

2. Banner of the cavalry

3. Cohort Banner

4. Banners of maniples

5. Standard bearer. On their heads, the standard-bearers wore the head of a cougar, a panther.

In the time of Marius the banners were silver, in the time of the empire they were gold. The cloths were multicolored: white, blue, red, purple.

The cavalry sword is one and a half times longer than the infantry. The swords are single-edged, the handles were made of bone, wood, metal.

A pilum is a heavy spear with a metal tip and shaft. Serrated tip. Wooden tree. The middle part of the spear is wrapped tightly coil to coil with a cord. One or two tassels were made at the end of the cord. The tip of the spear and the rod were made of soft forged iron, up to iron - of bronze. The pilum was thrown at the enemy's shields. The spear that stuck into the shield pulled it to the bottom, and the warrior was forced to drop the shield, as the spear weighed 4-5 kg and dragged along the ground, as the tip and rod were bent.

Shields (scutums) acquired a semi-cylindrical shape after the war with the Gauls in the 4th century. BC e. Scutums were made from light, well-dried, aspen or poplar boards tightly fitted to each other, covered with linen, and on top with bull skin. Along the edge, the shields were bordered with a strip of metal (bronze or iron) and strips were placed in a cross through the center of the shield. In the center was placed a pointed plaque (umbon) - the pommel of the shield. Legionnaires kept in it (it was removable) a razor, money and other small things. On the inside there was a belt loop and a metal clip, the name of the owner and the number of the centurion or cohort were written. The skin could be dyed: red or black. The hand was pushed into the belt loop and taken by the bracket, thanks to which the shield hung tightly on the hand.

The helmet in the center is an earlier one, the one on the left is a later one. The helmet had three feathers 400 mm long; in ancient times, helmets were bronze, later iron. The helmet was sometimes decorated in the form of snakes on the sides, which at the top formed a place where feathers were inserted. In later times, the only decoration on the helmet was the crest. At the top of the Roman helmet was a ring through which a strap was threaded. The helmet was worn on the back or on the lower back, as a modern helmet is worn.

1. Shell made of metal plates, in early times bronze, later iron, most common in the Roman army.

2. Leather shell (the leather was dyed) with metal plates sewn on it.

3. Scaled shell (made of metal). Consisted of two halves fastened with straps.

4. Carapace made of coarse quilted linen in several layers, soaked in salt. In terms of strength, it was not inferior to stone. It was cheaper than all the others.

Roman velites were armed with javelins and shields. The shields were round, made of wood or metal. Velites were dressed in tunics, later (after the war with the Gauls) all legionnaires began to wear trousers. Some of the velites were armed with slings. The slingers had bags for stones on their right side, over the left shoulder. Some velites may have had swords. Shields (wooden) were covered with leather. The color of the clothes could be anything except purple and its shades. Velites could wear sandals or go barefoot. Archers in the Roman army appeared after the defeat of the Romans in the war with Parthia, where the consul Crassus and his son died. The same Crassus who defeated the troops of Spartacus under Brundisium.

The centurions had silver-plated helmets, no shields, and the sword was worn on the right side. They had leggings and, as a distinctive sign on the armor, on the chest they had the image of a vine folded into a ring. During the manipulative and cohort construction of the legions, the centurions were on the right flank of the centuries, maniples, cohorts. The cloak is red, and all the legionnaires wore red cloaks. Only the dictator and high commanders were allowed to wear purple cloaks.

Hastati had a leather shell (it could have been linen), a shield, a sword and a pilum. The shell was sheathed (leather) with metal plates. The tunic is usually red, as is the cloak. Pants could be green, blue, gray.

The principes had exactly the same weapons as the hastati, only instead of a pilum they had ordinary spears.

The triarii were armed in the same way as the hastati and principes, but did not have a pilum, they had an ordinary spear. The shell was metal.

Animal skins served as saddles. The Romans did not know stirrups. The first stirrups were rope loops. The horses were not forged. Therefore, the horses were very taken care of.

2.

3.

4.

And the most durable, and the one for whom it is too early to die, lose exactly the same amount. For the present is the only thing they can lose, since this and only this they have. And what you don't have, you can't lose.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus "Alone with myself"

There is a civilization in the history of mankind that aroused admiration, envy and a desire to imitate in the descendants - and this is Rome. Almost all peoples tried to warm themselves in the reflections of the glory of the ancient empire, imitating Roman customs, government institutions Or at least architecture. The only thing that the Romans brought to perfection and that was very difficult for other states to copy was the army. The famous legions that created the largest and most famous state of the Ancient World.

Early Rome

Having arisen on the border of the Etruscan and Greek "spheres of influence" on the Apennine Peninsula, Rome initially represented a fortification in which the farmers of the three Latin tribes (tribes) took refuge during enemy invasions. In wartime, the union was ruled by a common leader, the Rex. In peacetime - a meeting of elders of individual clans - senators.

The army of early Rome was a militia of free citizens, organized according to the principle of property. The richest landowners were on horseback, the poorest peasants were armed only with slings. Poor residents - proletarians (mostly landless laborers who worked for stronger owners) - were freed from military service.

Legion swords

The tactics of the legion (at that time the Romans called their entire army “legion”) were very straightforward. All infantry lined up in 8 rows, quite far apart from one another. The strongest and most well-armed warriors, with strong shields, leather armor, helmets and, sometimes, leggings, stood in the first one or two rows. The last row was formed by triarii - experienced veterans who enjoyed great prestige. They performed the functions of a "detachment" and a reserve in case of emergency. In the middle remained poorly and variously armed fighters, who operated mainly with darts. Slingers and horsemen occupied the flanks.

But the Roman phalanx had only a superficial resemblance to the Greek. It was not intended to overturn the enemy with the pressure of the shields. The Romans tried to fight almost exclusively by throwing. The principes only covered the shooters, engaging in combat with enemy swordsmen if necessary. The only thing that saved the soldiers of the "eternal city" was that their enemies - the Etruscans, Samnites and Gauls - acted in exactly the same way.

At first, the campaigns of the Romans were rarely successful. The struggle with the Etruscan city of Wei for salt pans at the mouth of the Tiber (only 25 km from Rome) was carried out throughout the life of a whole generation. After a long series of unsuccessful attempts, the Romans nevertheless took the varnitsa ... Which gave them the opportunity to somewhat improve their financial affairs. At that time, salt mining brought the same income as gold mines. One could think of further conquests.

An unsuccessful attempt by modern reenactors to portray the Roman "tortoise".

What allowed an unremarkable, not numerous and poor tribe to overcome many other similar tribes? First of all, exceptional discipline, militancy and stubbornness. Rome resembled a military camp, the whole life of which was built according to the schedule: sowing - war with a neighboring village - harvesting - military exercises and home craft - sowing - war again ... The Romans suffered defeats, but always returned. Those who were not zealous enough were flogged, those who evaded military service were turned into slavery, those who fled from the battlefield were executed.

Since moisture could damage the shield glued from wood, a leather case was included with each scutum

However, cruel punishments were not often required. In those days, the Roman citizen did not separate personal interests from public ones. After all, only the city could protect his freedoms, rights and well-being. In the event of the defeat of everyone - both the rich horseman and the proletarian - only slavery awaited. Later, the emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius formulated the Roman national idea in the following way: “What is not good for the hive is not good for the bee either.”

Mule army

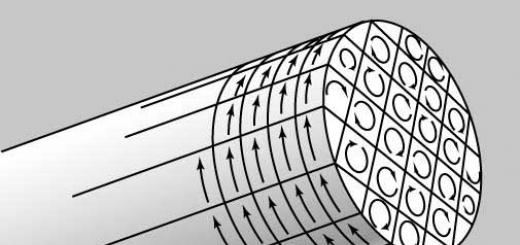

In the campaign, the legionnaire was practically invisible under the luggage

Legionnaires in Rome were sometimes called "mules" - because of the huge packs stuffed with supplies. There were no wheeled carts in the legion train, and for every 10 people there was only one real, four-legged mule. The shoulders of the soldiers were practically the only "transport".

The rejection of the wheeled convoy made the life of the legionnaires harsh. Each warrior had, in addition to his own weapons, to carry a load of 15-25 kg. All Romans, including centurions and horsemen, received only 800 grams of grain per day (from which it was possible to cook porridge or grind into flour and bake cakes) or crackers. Legionnaires drank vinegar-disinfected water.

But the Roman legion passed 25 kilometers a day in almost any terrain. If necessary, crossings could reach 45 and even 65 kilometers. The armies of the Macedonians or Carthaginians, burdened with many wagons with property and fodder for horses and elephants, on average passed only 10 kilometers per day.

Republican era

In the 4th century BC new era Rome was already a major trade and craft center. Albeit insignificant compared to such "megacities" as Carthage, Tarentum and Syracuse.

In order to continue their aggressive policy in the center of the peninsula, the Romans streamlined the organization of their troops. By this time there were already 4 legions. The basis of each of them was heavy infantry, built in three lines of 10 maniples (detachments of 120 or, in the case of triarii, 60 shieldmen). The hastati started a fight. Principles supported them. The triarii served as a general reserve. All three lines had heavy shields, helmets, iron-skin armor, and short swords. In addition, the legion had 1200 velites armed with javelins and 300 horsemen.

Pugio daggers were used by legionnaires along with swords

It is generally believed that the strength of the "classic" legion was 4500 people (1200 principes, 1200 hastati, 1200 velites, 600 triarii and 300 horsemen). But the legion at that time also included auxiliary troops: 5,000 allied infantry and 900 cavalry. Thus, in total, there were 10,400 warriors in the legion. The armament and tactics of the allies rather corresponded to the "standards" of early Rome. But the Italic cavalry even outnumbered the legion.

The tactics of the Legion of the Republican era had two original features. On the one hand, the Roman heavy infantry (with the exception of the triarii) still had not parted with throwing weapons, attempts to use which inevitably led to confusion.

On the other hand, the Romans were now ready for close combat as well. Moreover, unlike the Macedonian tagmas and Greek suckers, the maniples did not seek to merge with one another without gaps, which allowed them to move faster and better maneuver. In any case, the enemy hoplites could not, without breaking their own system, wedged between the Roman units. From the attacks of the light infantry, each of the maniples was covered by a detachment of 60 shooters. In addition, if necessary, the lines of hastati and principes, united, could form a solid front.

Nevertheless, the very first meeting with a serious enemy almost ended in disaster for the Romans. The Epirotians who landed in Italy, having 1.5 times the smaller army, defeated them twice. But after that, King Pyrrhus himself had to experience something like a culture shock. Refusing to conduct any negotiations, the Romans simply gathered a third army, having already achieved a two-fold advantage.

The triumph of Rome was ensured both by the Roman spirit, which recognized only war to a victorious end, and by the advantages of the republic's military organization. The Roman militia was very cheap to maintain, since all supplies were made at public expense. The state received food and weapons from manufacturers at cost. Like a tax in kind.

The connection between wealth and service in the army had disappeared by this point. The stocks of weapons in the arsenals allowed the Romans to call on impoverished proletarians (and, if necessary, freed slaves), which dramatically increased the country's mobilization capabilities.

Camp

Roman ten man leather tent

The Romans built field fortifications with amazing skill and speed. Suffice it to say that the enemy never risked attacking the legions in their camp. Not without reason, a fair share of legionary property was made up of tools: axes, shovels and spades (at that time shovels were made of wood and were only suitable for shoveling already loosened earth). There was also a supply of nails, ropes and bags.

In the simplest case, the Roman camp was a rectangular Earthworks surrounded by a moat. Along the crest of the shaft there was only a wattle fence, behind which it was possible to hide from arrows. But if the Romans planned to settle in the camp for a somewhat long period, the shaft was replaced by a palisade, and watchtowers were erected in the corners. During long operations (such as sieges) the camp was overgrown with real towers, wooden or stone. Leather tents gave way to thatched barracks.

Age of Empire

Gallic horseman's helmet

In the 2-3 centuries BC. e. The Romans had to fight Carthage and Macedonia. The wars were victorious, but in the first three battles with the Africans, Rome lost more than 100 thousand soldiers only killed. As in the case of Pyrrhus, the Romans did not flinch, formed new legions and, regardless of losses, crushed them by numbers. But they noticed that the combat effectiveness of the peasant militia no longer meets the requirements of the time.

In addition, the very nature of the war has changed. Gone are the days when the Romans left in the morning to conquer the varnitsa, and the next day they were already at home by dinner. Now the campaigns stretched out for years, and garrisons were required to be left on the conquered lands. Peasants also had to sow and harvest. Even in the first Punic War, the consul Regulus, who besieged Carthage, was forced to disband half of his army for the period of harvesting. Naturally, the Puns immediately made a sortie and killed the second half of the Romans.

In 107 BC, the consul Gaius Marius reformed the Roman army, transferring it to a permanent basis. Legionnaires began to receive not only a full content, but also a salary.

The soldiers were paid, by the way, pennies. About as much as an unskilled worker in Rome received. But the legionnaire could save money, count on awards, trophies, and after serving the prescribed 16 years, he received a large allotment of land and Roman citizenship (if he had not had it before). Through the army, a person from the lower social classes and not even a Roman got the opportunity to join the ranks of the middle class, becoming the owner of a shop or a small estate.

Original Roman inventions: "anatomical helmet" and half-helmet with eyecups

The organization of the legion has also changed completely. Marius abolished the division of the infantry into hastati, principes, triarii and velites. All legionnaires received uniform, somewhat lightweight weapons. From now on, the fight against enemy arrows was entirely entrusted to the cavalry.

Since the horsemen needed space, the Roman infantry from that time began to be built not by maniples, but by cohorts - 600 people each. The cohort, on the one hand, could be divided into smaller detachments, and on the other hand, it was able to act completely independently, since it had its own cavalry. On the battlefield, cohorts lined up in two or three lines.

The composition and strength of the "imperial" legion changed several times. Under Mary, he consisted of 10 cohorts of 600 people, 10 tours of 36 horsemen and auxiliary detachments of barbarians: 5000 light infantry and 640 cavalry. Only 12,000 people. Under Caesar, the size of the legion was reduced radically - to 2500-4500 fighters (4-8 cohorts and 500 hired Gallic horsemen). The reason for this was the nature of the war with the Gauls. Often, in order to defeat the enemy, one cohort with a cover of 60 horsemen was enough.

Later, Emperor Augustus reduced the number of legions from 75 to 25, but the number of each of them again exceeded 12 thousand. The organization of the legion was revised many more times, but it can be considered that during its heyday (not counting the auxiliary troops) there were 9 cohorts of 550 people each, one (right-flank) cohort of 1000-1100 selected soldiers and about 800 horsemen.

The Roman slinger wanted the enemy to know where he came from (the bullet says "Italy")

One of the strongest features of the Roman army is the well-organized training of command personnel. Each maniple had two centurions. One of them was usually a veteran who had risen from the soldiers. To others, a "trainee" from the class of horsemen. In the future, having successively passed all positions in the infantry and cavalry units of the legion, he could become a legate.

Praetorians

The game "Civilization" is already almost as old as Rome itself

In respectable and respected (the first of the games in this series appeared back in 1991!) Civilizations» Sid Meier's elite infantry of the Romans - Praetorians. Traditionally, praetorian cohorts are considered something like a Roman guard, but this is not entirely true.

At first, the "praetorian cohort" was called a detachment of nobility from among the tribes allied with Rome. In essence, these were hostages, whom the consuls sought to have on hand in case of disobedience of a foreign part of the army. During the Punic Wars, the staff cohort, which accompanied the commander and was not part of the usual staff of the legion, began to be called "praetorian". In addition to the detachment of bodyguards formed from the horsemen and the staff officers themselves, there were many scribes, orderlies and couriers in it.

Under Augustus, to maintain order in Italy, " internal troops": 9 Praetorian cohorts of 1,000 men each. Somewhat later, 5 more "city cohorts" that performed the tasks of the police and firefighters also began to be called Praetorian.

Strong center tactics

It may seem strange, but in the grand battle of Cannae, the Roman consul Varro and Hannibal seem to be acting according to a single plan. Hannibal builds troops on a wide front, clearly intending to cover the enemy's flanks with his cavalry. Varro, on the other hand, is trying in every possible way to make the task easier for the Africans. The Romans huddle together in a dense mass (in fact, they form a phalanx in 36 rows!) And rush straight into the "open arms" of the enemy.

Varro's actions seem incompetent only at first glance. In fact, he followed the usual tactics of the Romans, always placing the best troops and delivering the main attack in the center, not on the flanks. So did all the other "foot" peoples, from the Spartans and the Franks to the Swiss.

Roman armor: chain mail and "lorica segmentata"

Varro saw that the enemy had an overwhelming superiority in cavalry and understood that, no matter how he stretched the flanks, he could not avoid coverage. He deliberately went to battle surrounded, believing that the rear ranks of the legionnaires, turning around, would repel the onslaught of the cavalry that had broken through to the rear. In the meantime, the front ones will overturn the enemy’s front.

Hannibal outwitted the enemy by placing heavy infantry on the flanks, and the Gauls in the center. The crushing onslaught of the Romans actually fell into the void.

throwing machines

Light ballista on a tripod

One of the most exciting scenes in Ridley Scott's film Gladiator"- a massacre between the Romans and the Germans. Against the background of many other fantastic details in this battle scene, the actions of Roman catapults are also interesting. All this is too reminiscent of volleys of rocket artillery.

Under Caesar, some legions did have fleets of throwing machines. Including 10 collapsible catapults, used only during the sieges of fortresses, and 55 carroballists - heavy torsion crossbows on a wheeled cart. Carroballista fired a lead bullet or 450 gram bolt at 900 meters. At a distance of 150 meters, this projectile pierced the shield and armor.

But the carroballists, each of whom had to divert 11 soldiers to serve, did not take root in the Roman army. They did not have a noticeable effect on the course of the battle (Caesar himself valued them only for the moral effect), but they greatly reduced the mobility of the legion.

era of decline

The Roman army was well organized to help the wounded. In the illustration - a military surgeon's tool

At the beginning of a new era in Rome, whose power, it would seem, nothing could threaten, an economic crisis erupted. The treasury is empty. Already in the 2nd century, Marcus Aurelius sold the palace utensils and his personal property in order to help the starving after the flood of the Tiber and equip the army for the campaign. But subsequent rulers of Rome were neither so rich nor so generous.

The Mediterranean civilization was dying. rapidly declining urban population, the economy again became natural, palaces collapsed, roads were overgrown with grass.

The causes of this crisis, which threw Europe back a thousand years, are interesting, but require separate consideration. As for its consequences for the Roman army, they are obvious. The empire could no longer maintain legions.

At first, the soldiers began to be poorly fed, deceived with pay, not released after seniority, which could not but affect the morale of the troops. Then, in an effort to cut costs, the legions began to "plant on the ground" along the Rhine, turning the cohorts into the likeness of the Cossack villages.

The formal size of the army even increased, reaching a record high of 800,000, but its combat effectiveness fell to almost zero. There were no more people willing to serve in Italy, and gradually the barbarians began to replace the Romans in the legions.

The tactics and weapons of the legion changed once again, largely returning to the traditions of early Rome. Less and less weapons were supplied to the troops, or the soldiers were obliged to purchase them at their own expense. This explained the “unwillingness” of the legionnaires to wear armor, which caused bewilderment among the Roman armchair strategists.

Again, as in the old days, the entire army was lined up in a phalanx in 8-10 rows, of which only one or two first (and sometimes even the last) were shieldmen. Most legionnaires were armed with bows or manuballistas (light crossbows). As money became scarcer, regular troops were replaced more and more often by mercenary units. They did not need to be trained and maintained in peacetime. And in the military (in case of victory), it was possible to pay them off at the expense of production.

But the mercenary must already have a weapon and the skills to use it. The Italian peasants, of course, had neither one nor the other. "The last of the great Romans" Aetius led an army against the Huns of Atilla, the main force in which were the Franks. The Franks won, but this did not save the Roman Empire.

* * *

Rome collapsed, but its glory continued to shine through the ages, naturally giving rise to many who wished to declare themselves her heirs. There were already three "Third Romes": Ottoman Turkey, Muscovite Russia and Nazi Germany. And the fourth Rome, after so many unsuccessful attempts, one must think, really will not happen. Although the US Senate and Capitol suggest some reflections.

- 1st class: offensive - gladius, gasta and darts ( body), protective - helmet ( galea), shell ( lorica), bronze shield ( clipeus) and leggings ( ocrea);

- 2nd class - the same, without shell and scutum instead clipeus;

- 3rd class - the same, without leggings;

- 4th class - gasta and peak ( verum).

- offensive - spanish sword ( gladius hispaniensis)

- offensive - pilum (special throwing spear);

- protective - iron mail ( lorica hamata).

- offensive - dagger ( pugio).

At the beginning of the Empire:

- protective - shell lorica segmentata (Lorica Segmentata, segmented lorica), late plate armor from individual steel segments. Comes into use from the 1st c. The origin of the plate cuirass is not entirely clear. Perhaps it was borrowed by the legionnaires from the armament of the crupellari gladiators who participated in the rebellion of Flor Sacrovir in Germany (21). Chain mail also appeared during this period ( lorica hamata) with double chain mail on the shoulders, especially popular with cavalrymen. Lightweight (up to 5-6 kg) and shorter chain mail are also used in auxiliary infantry units. Helmets of the so-called imperial type.

- offensive - "Pompeian" sword, weighted pilums.

- protective - scale armor ( lorica squamata)

A uniform

- paenula(a short woolen dark cloak with a hood).

- tunic with long sleeves, sagum ( sagum) - a cloak without a hood, previously incorrectly considered a classic Roman military.

build

Manipulative tactics

It is practically generally accepted that during the period of their rule, the Etruscans introduced the phalanx among the Romans, and subsequently the Romans deliberately changed their weapons and formation. This opinion is based on reports that the Romans once used round shields and built a phalanx like Macedonian, however, in the descriptions of the battles of the 6th-5th centuries. BC e. the dominant role of the cavalry and the auxiliary role of the infantry are clearly visible - the first was often even located and acted ahead of the infantry.

From about the time of the Latin War or earlier, the Romans began to adopt manipulative tactics. According to Livy and Polybius, it was carried out in a three-line formation at intervals (hastati, principes and triarii in the rear reserve), with the maniples of the principles standing against the intervals between the maniples of the hastati.

The legions were located next to each other, although in some battles of the Second Punic War they stood one behind the other.

To fill the too widened intervals when moving over rough terrain, a second line served, individual detachments of which could move into the first line, and if this was not enough, a third line was used. In a collision with the enemy, the small remaining intervals were filled by themselves, due to the freer location of the soldiers for the convenience of using weapons. The use of the second and third lines to bypass the enemy flanks, the Romans began to use at the end of the Second Punic War.

The opinion that the Romans threw pilums during the attack, after which they switched to swords and during the battle they changed the lines of battle order, was disputed by Delbrück, who showed that it was impossible to change lines during close combat with swords. This was explained by the fact that for a quick and organized retreat of the hastati behind the principles, the maniples should be placed at intervals equal to the width of the front of an individual maniple. At the same time, it would be extremely dangerous to engage in hand-to-hand combat with such intervals in the line, since this would allow the enemy to cover the maniples of the hastati from the flanks, which would lead to an early defeat of the first line. According to Delbrück, in reality, the line was not changed in battle - the intervals between the maniples were small and served only to facilitate maneuvering. However, at the same time, most of the infantry was intended only for plugging gaps in the first line. Later, relying in particular on the “Notes on the Gallic War” by Caesar, the opposite was again proved, although it was recognized that it was not well-coordinated maneuvers of slender units.

On the other hand, even the hastati maniple covered from all sides could not be quickly destroyed, and kept the enemy in place, simply surrounding itself with shields from all sides (the huge shield of the legionnaires, absolutely unsuitable for individual combat, reliably protected it in the ranks and the legionnaire was only vulnerable for piercing blows from above, or in response), and the enemy, who penetrated through the gaps, could simply be thrown with darts (tela) of the principles (which, apparently, were attached to the inside of the shield in the amount of seven pieces), independently climbing into the firing bag and having no protection from flanking fire. The change of lines could represent a retreat of the hastati during a throwing battle, or a simple advance of the principles forward, with the hastati remaining in place. But the breakthrough of a continuous front, followed by confusion and the massacre of the defenseless heavy infantry[remove template] , which lost formation, was much more dangerous and could lead to a general flight (the surrounded maniple simply has nowhere to run).

Cohort tactics

Since about the 80s. BC e. cohort tactics began to be used. The reason for the introduction of a new formation was the need to effectively resist the massive frontal onslaught, which was used by the union of the Celtic-Germanic tribes. The new tactics supposedly found its first application in the Allied War - 88 BC. e. By the time of Caesar, cohort tactics were commonplace.

The cohorts themselves were built in a checkerboard pattern ( quincunx), on the battlefield could be used in particular:

- triple aces- 3 lines of four cohorts in the 1st and three in the 2nd and 3rd at a distance of 150-200 feet (45-65 meters) from each other;

- duplex acies- 2 lines of 5 cohorts each;

- simplex acies- 1 line from 10 cohorts.

On the march, usually on enemy territory, they were built in four parallel columns in order to make it easier to rebuild in triple aces on an alarm signal, or formed the so-called orbis(“circle”), which facilitated the retreat under heavy fire.

Under Caesar, each legion deployed 4 cohorts in the first line, and 3 in the second and third. When the cohorts stood in close formation, the distance separating one cohort from another was equal to the length of the cohort along the front. This gap was destroyed as soon as the ranks of the cohort were deployed for battle. Then the cohort stretched along the front almost twice as compared with the usual system.

The interaction of cohorts, due to the larger size of a separate detachment and the simplification of maneuvering, did not place such high demands on the individual training of each legionnaire.

Evocati

Soldiers who served their term and were demobilized, but re-enlisted in the military for voluntary basis, in particular on the initiative of, for example, the consul, were called evocati- letters. “newly called” (under Domitian, this was the name given to the elite guards of the equestrian class guarding his sleeping quarters; presumably, such guards retained their name under some subsequent emperors, cf. Evocati Augusti at Gigin). Usually they were listed in almost every unit, and apparently, if the commander was popular enough among the soldiers, the number of veterans of this category in his army could increase. Along with the vexillarii, the evocati were exempted from a number of military duties - fortifying the camp, laying roads, etc., and were higher in rank than ordinary legionnaires, sometimes compared with horsemen, or even were candidates for centurions. For example, Gnaeus Pompey promised to promote his former evocati to centurions upon completion civil war, but in total all evocati could not be promoted to this rank. All contingent evocati usually commanded by a separate prefect ( praefectus evocatorum).

Combat awards ( dona militaria)

Officers:

- wreaths ( coronae);

- decorative spears ( hastae purae);

- checkboxes ( vexilla).

Soldier:

- necklaces ( torques);

- phalera ( phalerae);

- bracelets ( armillae).

Literature

- Maxfield, V. The Military Decorations of the Roman Army

Discipline

In addition to training drills, the maintenance of iron discipline ensured a generally high combat readiness and moral potential of the Roman army for more than a thousand years of its existence.

More or less frequently used:

- replacing wheat with barley in rations;

- monetary fine or partial confiscation of trophies obtained ( pecuniaria multa);

- temporary isolation from colleagues or temporary removal from the camp;

- temporary deprivation of weapons;

- military exercises with luggage;

- guarding without military attire or even without a kalig;

- famous spanking ( castigatio) centurions of legionnaires with a vine or, which was more severe and shameful, with rods;

- pay cut ( aere dirutus);

- corrective labor ( munerum indictio);

- public flogging in front of a centurion, cohort or whole legion ( animadversio fustium);

- dismissal by rank ( degree deiectio) or by type of troops ( militiae mutatio);

- dishonorable discharge from service missio ignominiosa, which sometimes comprehended entire detachments);

- 3 types of execution: for soldiers - futuary (according to Kolobov, this was the name of execution during decimation, while decimatio denoted the type of draw), for centurions - cutting with rods and decapitation, and executions by lot (decimation, vicesimation and centesis).

At the beginning of the III century. BC e. a law was passed on death penalty for those who dodge military service. Under Vegetia, executions were announced by a special trumpet signal - classicum.

Also, for poor night watchkeeping, theft, perjury and self-mutilation, soldiers could drive their comrades armed with clubs through the ranks and the fear of this caused an effective effect.

The dissolution of the legion was applied to the rebellious (for political reasons or due to lower salaries) troops, and even then very rarely (the legion created in the city by the rebellious procurator of Africa Lucius Clodius Macros is noteworthy I Macriana Liberatrix, in which Galba executed the entire command staff). However, the commanders-in-chief, even under the emperors, enjoyed unlimited punitive power, except for the highest officers, whom they could up to that time also condemn to death. By decree of Augustus, they were deprived of such a right.

Various penalties (a fine, confiscation of property, imprisonment, even in some cases sale into slavery) could also be imposed if, for example, young men and men from 17 to 46 years old did not enlist in the army during the mobilization.

On the other hand, unwritten punishments were often used. So, for example, during the Latin War in 340 BC. e. son of the consul Titus Manlius Torquat, Titus Manlius the Younger, for a duel out of order, despite numerous requests, was beheaded by order of his own father; nevertheless, later this forced the soldiers to be more attentive, in particular, even to day and night guards.

It has become traditional. The army lost in flexibility, but in the absence of serious external enemies, this did not become a problem: the Roman Empire sought to defeat the enemy in one decisive battle. Therefore, during the fighting, she moved in a dense army column. This arrangement simplified the task of deploying troops to form up before battle.

The traditional basis of the Roman battle order was the legions, which consisted of ten cohorts, up to about 500 people each. Since the reign of Octavian Augustus, the acies duplex system has been used - two lines of five cohorts. The depth of the formation of the cohort was equal to four soldiers, and the legion - eight. Such a formation provided good stability and effectiveness of troops in battle. The old, three-line system (aies triplex) fell into disuse, since during the years of the empire, Rome did not have an enemy with a highly organized army against which it could be needed. The formation of the legion could be closed or open - this made it possible, depending on the situation, to occupy more or less space on the battlefield.

An important aspect of the construction of the legion was the protection of the flank - traditionally the weak point of any army at all times. To make flank bypass difficult for the enemy, it was possible to stretch the formation or hide behind natural obstacles - a river, a forest, a ravine. Best Troops- both legions and auxiliary - the Roman generals put on the right flank. On this side, the warriors were not covered by shields, which means they became more vulnerable to enemy weapons. The defense of the flank, in addition to being practical, had a great moral effect: a soldier who knew that he was not in danger of being outflanked fought better.

The construction of the legion in the II century. AD

According to Roman law, only citizens of Rome could serve in the legion. Auxiliary units were recruited from among free people who wanted to obtain citizenship. In the eyes of the commander, they were of less value than the legionnaires, due to the difficulty of recruiting replacements, and therefore were used for cover, and were also the first to engage in battle with the enemy. Since they were lighter armed, their mobility was higher than that of the legionnaires. They could start a fight, and in the event of a threat of defeat, retreat under the cover of the legion and reorganize.

The Roman cavalry also belonged to the auxiliary troops, with the exception of the small (only 120 people) cavalrymen of the legion. They were recruited from a variety of peoples, so the construction of the cavalry could be different. The cavalry played the role of skirmishers of the battle, scouts, could be used as a strike unit. Moreover, all these roles were often assigned to the same unit. The most common type of Roman cavalry was the contarii, armed with a long lance and dressed in chain mail.

The Roman cavalry was well trained, but not numerous. This prevented her from being truly effective in battle. During I – In the 2nd century AD, the Romans constantly increased the number of cavalry units. In addition, new varieties of them appeared at this time. So, in the time of Augustus, horse archers appeared, and later, under the emperor Hadrian, cataphracts. The first detachments of cataphractaries were created on the basis of the experience of wars with the Sarmatians and Parthians and were shock units. It is difficult to say how effective they were, since there is little evidence of their participation in battles.

The general principles of preparing the army of the Roman Empire for battle could change. So, for example, if the enemy dispersed and avoided a general battle, then the Roman commander could send part of the legions and auxiliary troops to destroy enemy territory or capture fortified settlements. These actions could lead to the surrender of the enemy even before the big battle. In a similar way, even during the time of the Republic, Julius Caesar acted against the Gauls. More than 150 years later, Emperor Trajan chose a similar tactic when he captured and sacked the Dacian capital of Sarmizegetusa. The Romans, by the way, were one of the ancient peoples who made the process of robbery organized.

The structure of the Roman centurion

The structure of the Roman centurion

If the enemy did take the fight, then the Roman commander had another advantage: the temporary camps of the legions were an excellent defense, so the Roman commander himself chose when to start the battle. In addition, the camp made it possible to wear down the enemy. For example, the future emperor Tiberius, when conquering the region of Pannonia, seeing that the hordes of his opponents entered the battlefield at dawn, gave the order not to leave the camp. The Pannonians were forced to spend the day in the pouring rain. Then Tiberius attacked the weary barbarians and defeated them.