Started in 1914, it engulfed the territory of almost all of Europe with a fire of battles and battles. More than thirty states with a population of more than a billion people participated in this war. The war became the most grandiose in terms of destruction and human casualties in the entire previous history of mankind. Before Europe was divided into two opposing camps: the Entente represented by Russia, France, and the smaller countries of Europe and represented by Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy, which in 1915 sided with the Entente, and also smaller European countries. The material and technical superiority was on the side of the Entente countries, but the German army was the best in terms of organization and weapons.

Under such conditions, the war began. It was the first that can be called positional. Opponents, possessing powerful artillery, rapid-fire small arms and defense in depth, were in no hurry to go on the attack, which foreshadowed huge losses for the attacking side. Nevertheless fighting with varying success without a strategic advantage took place in both main theaters of operations. First World War, in particular, played a significant role in the transition of the initiative to the Entente bloc. And for Russia, these events had rather unfavorable consequences. During the Brusilov breakthrough, all the reserves of the Russian Empire were mobilized. General Brusilov was appointed commander of the Southwestern Front and had at his disposal 534 thousand soldiers and officers, about 2 thousand guns. The Austro-German troops opposing him had 448 thousand soldiers and officers and about 1800 guns.

The main reason for the Brusilov breakthrough was the request of the Italian command to involve the Austrian and German units in order to avoid the complete defeat of the Italian army. The commanders of the Northern and Western Russian fronts, Generals Evert and Kuropatkin, refused to launch an offensive, considering it completely unsuccessful. Only General Brusilov saw the possibility of a positional strike. On May 15, 1916, the Italians suffered a severe defeat and were forced to request that the offensive be accelerated.

On June 4, the famous Brusilov breakthrough of 1916 begins, Russian artillery fired continuously at enemy positions for 45 hours in separate areas, it was then that the rule of artillery preparation before the offensive was laid down. After an artillery strike, infantry went into the gap, the Austrians and Germans did not have time to leave their shelters and were taken prisoner in masses. As a result of the Brusilov breakthrough, Russian troops wedged into the enemy defenses for 200-400 km. The 4th Austrian and German 7th armies were completely destroyed. Austria-Hungary was on the verge of complete defeat. However, without waiting for the help of the Northern and Western Fronts, whose commanders missed the tactical moment of advantage, the offensive soon stopped. Nevertheless, the result of the Brusilov breakthrough was salvation from the defeat of Italy, the preservation of Verdun for the French and the consolidation of the British on the Somme.

B.P. Utkin

"Brusilovsky breakthrough" 1916 May 22 (June 4) - July 31 (August 13). One of the largest military operations of the First World War, which ended with a significant loss of Russian troops.

Russian forces under the command of General A.A. Brusilov carried out a powerful breakthrough of the front in the direction of Lutsk and Kovel. The Austro-Hungarian troops were defeated and began a disorderly retreat. The rapid offensive of the Russian troops led to the fact that they occupied Bukovina in a short time and reached the mountain passes of the Carpathians. The losses of the enemy (together with the prisoners) amounted to about 1.5 million people. He also lost 581 guns, 448 bombers and mortars, 1795 machine guns. Austria-Hungary was on the verge of complete defeat and exit from the war. To save the situation, Germany withdrew 34 divisions from the French and Italian fronts. As a result, the French managed to keep Verdun, and Italy was saved from complete defeat.

Russian troops lost about 500 thousand people. The victory in Galicia changed the balance of power in the war in favor of the Entente. In the same year, Romania went over to its side (which, however, did not strengthen, but rather weakened the position of the Entente due to the military weakness of Romania and the need to protect it. The length of the front for Russia increased by about 600 km).

The military history of Russia is rich in events that have left an indelible mark on the military-historical consciousness of the people and are inscribed with golden pages in science, in the centuries-old experience of overcoming historical catastrophes while repelling foreign aggression. One of these pages is the offensive operation of the Southwestern Front (SWF) in 1916. It's about about the only battle of the First World War, which was named by contemporaries and descendants after the commander-in-chief of the armies of the South-Western Front, General of the Cavalry Alexei Alekseevich Brusilov, on whose initiative and under whose brilliant leadership it was prepared and carried out. This is the famous Brusilovsky breakthrough. In Western encyclopedias and numerous scientific works it entered as "Brussilow angritte", "The Brusilov offensive", "Offensive de Brussilov".

The 80th anniversary of the Brusilov breakthrough arouses great public interest in the personality of A.A. Brusilov, to the history of the idea, methods of preparation, implementation and results of this unique operation of the First World War in its success. Such an interest is all the more relevant because in Soviet historiography the experience of the First World War is extremely insufficiently covered, and many of its military leaders still remain unknown.

A.A. Brusilov was appointed to the post of Commander-in-Chief (GK) of the armies of the South-Western Front on March 16 (29), 1916. At that time, this front-line association represented an impressive force. It included four armies (7th, 8th, 9th and 11th), parts of the front set (artillery, cavalry, aviation, engineering troops, reserves). The Kyiv and Odessa military districts were also subordinate to the commander-in-chief (they were located on the territory of 12 provinces). In total, the front grouping consisted of more than 40 infantry (pd) and 15 cavalry (cd) divisions, 1770 guns (including 168 heavy ones); the total number of troops on the Southwestern Front exceeded 1 million people. The front line extended for 550 km, the rear border of the front was the river. Dnieper.

The choice of the GC YuZF A.A. Brusilov by the emperor and the Headquarters of the High Command had a deep foundation: the general was rightfully considered in the Russian army one of the most honored military leaders, whose experience, personal qualities and performance results were in harmonious unity and opened up prospects for achieving new successes in combat operations. He had 46 years of experience behind him military service, which happily combined participation in hostilities, leadership of units, higher educational institutions, command of formations and associations. He was marked by all the highest awards Russian state. From the beginning of the First World War, Brusilov commanded the troops of the 8th Army (8A). At the post of commander during the battles of the initial period of the war, and then in the Battle of Galicia (1914), in the 1915 campaign, talent and best qualities Brusilov - commander: originality of thinking, boldness of judgments, conclusions and decisions, independence and responsibility in the leadership of a large operational association, dissatisfaction with what has been achieved, activity and initiative. Perhaps the biggest discovery of Brusilov, the commander, made in the course of painful reflections during the twenty-two months of the war and finally decided by the spring of 1916, was the conclusion, or rather, the conviction that the war must be waged differently, that many front commanders , as well as the highest ranks of the Headquarters, for various reasons, are not able to turn the tide of events. He clearly saw the obvious vices of the military and government controlled country from top to bottom.

1916 is the culmination of the First World War: the opposing sides mobilized almost all of their human and material resources. The armies suffered enormous losses. Meanwhile, none of the parties achieved any serious successes, which at least to some extent opened up prospects for a successful (in their favor) end of the war. From the point of view of operational art, the beginning of 1916 resembled the starting position of the warring armies before the start of the war. IN military history the current situation is called a positional impasse. The opposing armies created a solid front of defense in depth. The presence of numerous artillery, the high density of the defending troops made the defense difficult to overcome. The absence of open flanks and vulnerable seams doomed attempts to break through, let alone maneuver, to failure. The extremely tangible losses during the breakthrough attempts were also proof that the operational art and tactics did not correspond to the real conditions of the war. But the war continued. Both the Entente (England, France, Russia and other countries) and the states of the German bloc (Austria-Hungary, Italy, Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, etc.) were determined to fight the war to a victorious end. Plans were put forward, there was a search for options for hostilities. However, one thing was clear to everyone: any offensive with decisive goals must begin with a breakthrough in defensive positions, to look for a way out of the positional impasse. But even in 1916 no one managed to find such a way out (Verdun, Somme, the failures of the Western Front 4A, the South-Western Front - 7A). The impasse within the SWF was overcome by A.A. Brusilov.

The offensive operation of the South-Western Front (June 4-August 10, 1916) is an integral part of the military operations of the Russian army and its allies in the Entente, as well as a reflection of the prevailing strategic views, decisions taken by the parties and the balance of forces and means in 1916. The Entente (including and Russia) recognized the need to conduct an offensive against Germany coordinated in time and objectives. Superiority was on the side of the Entente: on the Western European front, 139 Anglo-French divisions were opposed by 105 German divisions. On the East European front, 128 Russian divisions operated against 87 Austro-German divisions. The German command decided to go on the defensive on the Eastern Front, and on the Western Front - to take France out of the war by offensive.

The strategic plan for the conduct of hostilities by the Russian army was discussed at Headquarters on April 1-2, 1916. Based on the tasks common and agreed with the allies, it was decided to the troops of the Western (ZF; GK - A.E. Evert) and Northern (SF; GK - A.N. Kuropatkin) fronts to prepare for mid-May and conduct offensive operations. The main blow (in the direction of Vilna) was to be delivered by the Western Front. According to the idea of the Stavka, the South-Western Front was assigned a passive auxiliary role, it was tasked to conduct defensive battles and tie down the enemy. The explanation was simple: the South-Western Front was incapable of attacking, it was weakened by the failures of 1915, and the Stavka had neither the strength, nor the means, nor the time to strengthen it. All cash reserves were given to the SF and SF. It can be seen that the idea was based on a quantitative approach to the capabilities of the troops.

But was it necessary to determine the role of each front, including the South-Western Front, only by quantitative indicators? It was this question that was posed by A.A. Brusilov, first before the emperor when he was appointed to the post, and then at a meeting at Headquarters. He spoke after the reports of M.V. Alekseeva, A.E. Evert and A.N. Kuropatkin. Wholly agreeing with the decision on the tasks of the Polar Front (the main direction) and the Northern Front, Brusilov, with all conviction, determination and faith in success, insisted on changing the task of the SWF. He knew that he was going against everyone:

the inability of the SWF to advance was defended by the chief of staff of the Stavka M.V. Alekseev (until 1915 - chief of staff of the South-Western Front), former commander of the South-Western Front N.I. Ivanov, even Kuropatkin, and he dissuaded Brusilov. However, Evert and Kuropatkin did not believe in the success of their fronts either. Brusilov managed to achieve a revision of the decision of the Headquarters - the South-Western Front was allowed to attack, however, with private, passive tasks and relying only on its own forces. But even this was a definite victory over the routine and distrust of the SWF. There are few examples in military history when a military leader with such perseverance, will, perseverance and arguments of reason sought to complicate his own task, staked his authority, his well-being, fought for the prestige of the troops entrusted to him. It seems that this largely determines the old question: what motivated Brusilov, what are the motives for his activities?

The successful solution of the task of the South-Western Front in the operation was initially associated not with quantitative superiority over the enemy in forces and means (i.e., not with the traditional approach), but with other categories of operational (generally - military) art: massing forces and means in selected areas , the achievement of surprise (deception of the enemy, operational camouflage, operational support measures, the use of previously unknown methods and methods of armed struggle), skillful maneuver of forces and means. It is absolutely clear that the fate of the operation to a greater extent depended on its initiator, organizer, and executor. Brusilov understood this, moreover, he was convinced that failure was excluded, the stake was placed only on victory, on success.

The offensive of the armies of the Russian Southwestern Front in May - June 1916 was the first successful front-line operation of the Entente coalition. Moreover, this was the first breakthrough of the enemy front on a strategic scale. The innovations applied by the command of the Russian South-Western Front in terms of organizing a breakthrough of the enemy fortified front became the first and relatively successful attempt to overcome the “positional impasse”, which became one of the priority characteristics of the hostilities during the First World War of 1914-1918.

Nevertheless, it was not possible to achieve victory in the struggle by withdrawing Austria-Hungary from the war. In the battles of July-October, the blinding victories of May-June were drowned in the blood of enormous losses, and the victorious strategic results of the war on the Eastern Front were wasted. And in this matter, not everything (although, undoubtedly, a lot) depended on the high command of the Southwestern Front, which owns the honor of organizing, preparing and carrying out a breakthrough of the enemy defense in 1916.

The operational and strategic planning of the Russian Headquarters of the Supreme High Command for the campaign of 1916 implied a strategic offensive on the Eastern Front by the combined efforts of the troops of all three Russian fronts - the Northern (commander - General A.N. Kuropatkin, from August 1 - General N.V. Ruzsky ), Western (commander - Gen. A.E. Evert) and South-Western (commander - Gen. A.A. Brusilov). Unfortunately, due to certain circumstances of a predominantly subjective nature, this planning could not be implemented. Due to a number of reasons, supposed by the Headquarters of the Supreme Command in the person of the Chief of Staff of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, Gen. M. V. Alekseev, the operation of a group of fronts resulted only in a separate front-line operation of the armies of the South-Western Front, which included from four to six armies.

German Minister of War and Chief of the Field General Staff Gen. E. von Falkenhayn

Positional struggle involves heavy losses. Especially - from the side of the coming. Especially - if it was not possible to break through the enemy's defenses and thereby compensate for their own losses incurred during the assault. In many respects, the persistence of the command of the South-Western Front in a once-given direction and the disregard of the higher headquarters for losses in the personnel of the active troops are explained by the internal logic of the positional struggle that unexpectedly confronted all sides and the resulting methods and methods of warfare.

As modern authors say, the “exchange” strategy developed by the Entente countries as a means of resolving the deadlock of a positional war could not but lead to the most disastrous results, since, first of all, “such a course of action is extremely negatively perceived by their own troops.” The defender suffers fewer losses, because he can use the advantages of technology to a greater extent. It was this approach that broke the German armies thrown at Verdun: the soldier always hopes to survive, but in that battle where he is surely destined to die, the soldier experiences only horror.

As for losses, this question very, very controversial. At the same time, not so much the number of losses in general, but their ratio between the warring parties. established in national historiography the figures for the ratio of losses are: one and a half million, including a third of prisoners of war, from the enemy against five hundred thousand from the Russians. Russian trophies amounted to 581 guns, 1795 machine guns, 448 bombers and mortars. These figures originate from an approximate calculation of official communications data, subsequently summarized in the “Strategic Outline of the War of 1914-1918”, M., 1923, part 5.

There are many controversial points here. First, it is the time frame. The Southwestern Front lost about half a million people only in May - mid-July. At the same time, the Austro-German losses of one and a half million people are calculated for the period up to October. Unfortunately, in a number of solid works, time frames are not indicated at all, which only makes it difficult to understand the truth. At the same time, the figures even in the same work may be different, which is explained by the inaccuracy of the sources. One might think that such silence can overshadow the feat of the Russian people, who did not have weapons equal to the enemy and therefore were forced to pay with their blood for the enemy's metal.

Secondly, this is the ratio of the number of "bloody losses", that is, those killed and wounded, with the number of prisoners. So, in June - July, the maximum number of wounded in the entire war was received from the armies of the Southwestern Front: 197,069 people. and 172,377 people. respectively. Even in August 1915, when the bloodless Russian armies rolled back to the east, the monthly influx of wounded was 146,635.

All this suggests that the bloody losses of the Russians in the 1916 campaign of the year were greater than even in the lost campaign of 1915. This conclusion is given to us by the outstanding domestic military scientist, General N. N. Golovin, who during the offensive of the armies of the Southwestern Front held the post of chief of staff of the 7th Army. N. N. Golovin says that in the summer campaign of 1915 the percentage of bloody losses was 59%, and in the summer campaign of 1916 - already 85%. At the same time, 976,000 Russian soldiers and officers were taken prisoner in 1915, and only 212,000 in 1916. The numbers of Austro-German prisoners of war taken as trophies by the troops of the Southwestern Front, in various works also vary from 420,000 to " more than 450,000”, or even “trim” to 500,000 people. Still, the difference of eighty thousand people is very significant!

In Western historiography, quite monstrous figures are sometimes called. Thus, the Oxford Encyclopedia tells its general reader that during the Brusilov breakthrough, the Russian side lost a million people killed. It turns out that during the period of participation of the Russian Empire in the First World War (1914–1917) it was on the Southwestern Front in May–October 1916 that the Russian Army in the field suffered almost half of all irretrievable losses during the period of participation of the Russian Empire in the First World War.

A natural question arises: what did the Russians do before? This figure, without hesitation, is presented to the reader, despite the fact that even the British military representative at the Russian Headquarters A. Knox reported that about a million people were the total losses of the Southwestern Front. At the same time, A. Knox rightly pointed out that “the Brusilovsky breakthrough was the most outstanding military event of the year. It surpassed other Allied operations both in terms of the scale of the occupied territory, and in the number of enemy soldiers destroyed and captured, and in the number of enemy units involved.

The figure of 1,000,000 losses (this is a reliance on the official data of the Russian side) is given by such an authoritative researcher as B. Liddell-Gart. But! He clearly says: “The total losses of Brusilov, although terrible, amounted to 1 million people ...” That is, it is quite rightly said here about all the losses of the Russians - killed, wounded and captured. And according to the Oxford Encyclopedia, one might think that the armies of the Southwestern Front, following the usual ratio between irretrievable and other losses (1: 3), lost up to 4,000,000 people. Agree that a difference of more than four times is still a very significant thing. And just a single word "killed" was added - and the meaning changes in the most radical way.

It is not for nothing that in Western historiography almost no mention is made of the Russian struggle of 1915 on the Eastern Front - the very struggle that allowed the Allies to create their own armed forces (primarily Great Britain) and heavy artillery (France). That very struggle, when the Russian active army lost most of its sons, paying for the stability and rest of the French front with Russian blood.

Ambush in the forest

And here the losses are only those killed: a million people in 1916 and a million before the Brusilov breakthrough (a total figure of two million dead Russians is given in most Western historical works), and this is the logical conclusion that the Russians in the battles on the continent applied in 1915 no big efforts compared to the Anglo-French. And this at a time when a sluggish positional “reshoving” was going on in the West, and the whole East was on fire! And why? The answer is simple: the leading Western powers got in touch with backward Russia, and they didn’t even know how to fight properly.

There is no doubt that serious historical studies of Western historiography still adhere to objective figures and criteria. Just for some reason, in the most authoritative and publicly available Oxford Encyclopedia, the data is unrecognizably distorted. It seems that this is a consequence of the tendency to deliberately underestimate the significance of the Eastern Front and the contribution of the Russian army to achieving victory in the First World War in favor of the Entente bloc. After all, even the same relatively objective researcher B. Liddell-Hart also believes that “ true story of the 1915 war on the Eastern Front represents a bitter struggle between Ludendorff, who tried to achieve decisive results by applying a strategy that, at least geographically, was indirect action, and Falkengine, who believed that with a strategy of direct action he could reduce the losses of his troops and simultaneously undermine Russia's offensive power." Like this! The Russians, consider, did nothing, and if they were not knocked out of the war, it was only because the top military leaders of Germany could not come to an agreement among themselves about the most effective way to defeat the Russians.

The most objective are the data of N. N. Golovin, who calls the total number of Russian losses in the summer campaign of 1916 from May 1 to November 1 at 1,200,000 killed and wounded and 212,000 captured. It is clear that this should also include the losses of the armies of the Northern and Western fronts, as well as the Russian contingent in Romania since September. If we subtract from 1,412,000 the estimated losses of Russian troops in other sectors of the front, then no more than 1,200,000 losses will remain for the share of the Southwestern Front. However, these figures cannot be final, since N. N. Golovin could be wrong: his work “Russian Military Efforts in the World War” is extremely accurate, but with regard to the calculation of casualties in the personnel, the author himself stipulates that the data given are only the maximum approximate, according to the author's calculations.

To a certain extent, these figures are confirmed by the data of the Chief of Military Communications at the Headquarters of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, Gen. S. A. Ronzhin, who says that during the spring-summer of 1916, over a million wounded and sick were taken from the South-Western Front to the near and far rear.

It can also be noted here that the figure of Western researchers of 1,000,000 people lost by the Russian armies during the Brusilov breakthrough for the entire period of attacks by the Southwestern Front from May to October 1916 is not "taken from the ceiling." The figure of 980,000 men lost by the armies of Gen. A. A. Brusilova, was indicated by the French military representative at the Petrograd Conference in February 1917, General. N.-J. de Castelnau in a report to the French Ministry of War dated February 25, 1917. Obviously, this is the official figure that was given to the French by Russian colleagues of the highest level - first of all, by the Acting Chief of Staff of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief Gen. V. I. Gurko.

As for the Austro-German losses, even here you can find a variety of data, differing by almost a million people. So, the largest figures of enemy losses were named by the Glavkoyuz gene. A. A. Brusilov in his memoirs: over 450,000 prisoners and over 1,500,000 killed and wounded for the period from May 20 to November 1. These data, based on the official reports of the Russian headquarters, were supported by all subsequent domestic historiography.

At the same time, foreign data do not give such a huge ratio of losses between the parties. For example, Hungarian researchers, without giving, however, the time frame of the Brusilov breakthrough, call the loss of Russian troops in more than 800,000 people, while the losses of the Austro-Hungarians (without the Germans) are "approximately 600,000 people." This ratio is closer to the truth.

And in Russian historiography, there are rather cautious points of view on this issue, correcting both the number of Russian losses and the ratio of losses of the warring parties. So, S. G. Nelipovich, who specially studied this issue, rightly writes: “... The breakthrough at Lutsk and on the Dniester really shook the Austro-Hungarian army. However, by July 1916, she had recovered from the defeat and, with the help of German troops, she was able not only to repel further attacks, but also to defeat Romania ... The enemy guessed the direction of the main attack already in June and then repelled it with the help of mobile reserves at the key sectors of the front. Further, S. G. Nelipovich believes that the Austro-Germans lost "a little more than 1,000,000 people" on the Eastern Front by the end of 1916. And if thirty-five divisions were deployed against the armies of General Brusilov from other fronts, then Romania demanded forty-one divisions for its defeat.

Machine-gun point on the guard headquarters

Thus, the additional efforts of the Austro-Germans were directed not so much against the Russian Southwestern Front, but rather against the Romanians. True, it should be borne in mind that Russian troops also operated in Romania, which by the end of December 1916 constituted a new (Romanian) front in three armies, numbering fifteen army and three cavalry corps in their ranks. This is more than a million Russian bayonets and sabers, despite the fact that the actual Romanian troops at the front were already no more than fifty thousand people. There is no doubt that since November 1916, the lion's share of the allied troops in Romania were already Russians, against whom, in fact, the very forty-one Austro-German division fought, which suffered not so heavy in the fight against the Romanians in Transylvania and near Bucharest losses.

At the same time, S. G. Nelipovich also refers to the data on the losses of the Southwestern Front: “Only according to approximate estimates according to the statements of the Headquarters, Brusilov’s Southwestern Front lost 1.65 million people from May 22 to October 14, 1916.” , including 203,000 killed and 152,500 captured. “It was this circumstance that decided the fate of the offensive: thanks to the “Brusilov method”, the Russian troops choked on their own blood.” Also, S. G. Nelipovich rightly writes that “the operation did not have a clearly defined goal. The offensive was developed for the sake of the offensive itself, in which it was a priori assumed that the enemy would suffer heavy losses and involve more troops than the Russian side. The same thing could be observed in the battles near Verdun and on the Somme.

Recall that Gen. N. N. Golovin pointed out that from May 1 to November 1, all Russian troops on the Eastern Front lost 1,412,000 people. That is, it is on all three fronts of the Russian Active Army, plus the Caucasian Army, where three large-scale operations were carried out in 1916 - Erzerum and Trebizond offensive and Ognot defensive. Nevertheless, the reported figures of Russian losses in various sources differ significantly (more than 400,000!), and the whole problem obviously lies in calculating the losses of the enemy, which are given, first of all, according to references to official Austro-German sources, which are not reliable.

Allegations of the unreliability of the Austro-German sources have already been repeatedly raised in world historiography. At the same time, the figures and data of reputable monographs and generalizing works are based precisely on official data, in the absence of others. Comparison of various sources, as a rule, gives the same result, since all mainly come from the same data. For example, Russian data is also highly inaccurate. So, the last domestic work "World Wars of the XX century", based on the official data of the states participating in the war, names Germany's losses in the war: 3,861,300 people. total, including 1,796,000 dead. Considering that the Germans suffered most of their losses in France, and, in addition, they fought on all the fronts of the World War without exception, it is clear that large numbers of losses against the Russian Southwestern Front cannot be expected.

Indeed, in another publication of his, S. G. Nelipovich presented Austro-German data on the losses of the armies of the Central Powers on the Eastern Front. According to them, it turns out that during the 1916 campaign, the enemy lost 52,043 people in the East. killed, 383,668 missing, 243,655 wounded and 405,220 sick. These are the same "slightly more than 1,000,000 people." B. Liddell-Gart also points out that three hundred and fifty thousand prisoners were in the hands of the Russians, and not half a million. Though the nine-to-two ratio between wounded and killed appears to be an understatement of deadweight losses.

Still, the reports of Russian commanders in the zone of military operations of the armies of the Southwestern Front and the memories of Russian participants in the events give a largely different picture. Thus, the question of the ratio of the losses of the opposing sides remains open, since the data of both sides are likely to be inaccurate. Obviously, the truth, as always, lies somewhere in the middle. Thus, the Western historian D. Terrain gives somewhat different figures for the entire war, presented by the Germans themselves: 1,808,545 killed, 4,242,143 wounded and 617,922 prisoners. As you can see, the difference with the above figures is relatively small, but Terrain immediately stipulates that, according to Allied estimates, the Germans lost 924,000 prisoners. (difference by a third!), so that "it is very possible that the other two categories are underestimated to the same extent."

Also, A. A. Kersnovsky in his work “History of the Russian Army” constantly points out the fact that the Austro-Germans underestimated the actual number of their losses in battles and operations, sometimes three to four times, while overestimating the losses of their opponents, especially Russians. It is clear that such data of the Germans and Austrians, submitted during the war as a report, completely passed into official works. Suffice it to recall the figures of E. Ludendorff about the sixteen Russian divisions of the 1st Russian Army at the first stage of the East Prussian offensive operation of August 1914, wandering through all Western and even Russian research. Meanwhile, in the 1st Army at the beginning of the operation there were only six and a half infantry divisions, and there were no sixteen at all by the end.

For example, the defeat of the Russian 10th Army in the August operation of January 1915 and the capture of the 20th Army Corps by the Germans look like the Germans allegedly took 110,000 people prisoner. Meanwhile, according to domestic data, all the losses of the 10th Army (by the beginning of the operation - 125,000 bayonets and sabers) amounted to no more than 60,000 people, including most of them, undoubtedly, prisoners. But not the whole army! Not without reason, the Germans not only failed to build on their success by stopping in front of the Russian defensive lines on the Beaver and Neman rivers, but were also repulsed after the approach of Russian reserves. In our opinion, B. M. Shaposhnikov once rightly noted that “German historians have firmly mastered Moltke’s rule: in historical works “to write the truth, but not the whole truth.” With regard to the Great Patriotic War, about the same - deliberately false exaggeration of the enemy's forces by the Germans in the name of extolling their own efforts, - says S. B. Pereslegin. Tradition, however: “In general, this statement is a consequence of the ability of the Germans to create after the battle, by simple arithmetic manipulations, his alternative Reality, in which the enemy would always have superiority (in the case of a German defeat, multiple).”

Junkers of the Nikolaev Cavalry School in the Army

Here it is necessary to cite one more interesting piece of evidence, which, perhaps, at least to a small extent, can shed light on the principle of calculating losses in the Russian armies during the Brusilov breakthrough. S. G. Nelipovich, naming the losses of the South-Western Front at 1,650,000 people, indicates that these are data on the calculation of losses, according to the statements of the Stavka, that is, obviously, according to information, primarily provided by the headquarters of the South-Western Front to the highest instances. So, regarding such statements, interesting evidence can be obtained from the general on duty at the headquarters of the 8th Army, Count D.F. Heiden. It was this headquarters institute that was supposed to draw up the loss lists. Count Heiden reports that when Gen. A. A. Brusilov as Commander-8, General Brusilov deliberately overestimated the losses of the troops entrusted to him: “Brusilov himself often persecuted me because I too adhere to the truth and show the higher authorities, that is, the headquarters of the front, what is in reality, but I do not exaggerate the figures of losses and the necessary replenishments, as a result of which we were sent less than what we needed.

In other words, General Brusilov, trying to achieve the sending a large number replenishment, already in 1914, while still commander-8, he ordered to exaggerate the figures of losses in order to get more reserves at his disposal. Recall that by May 22, 1916, the reserves of the Southwestern Front, concentrated behind the 8th Army, amounted to only two infantry and one cavalry division. There were not enough reserves even to build on success: this circumstance, for example, forced the commander of the 9th gene. P. A. Lechitsky put in the trenches of the 3rd cavalry corps of the gene. Count F. A. Keller, since there was no one else to cover the front exposed as a result of the withdrawal of infantry corps to the areas planned for a breakthrough.

It is quite possible that in 1916, as Commander-in-Chief of the armies of the Southwestern Front, Gen. A. A. Brusilov continued the practice of deliberately exaggerating the losses of his troops in order to receive significant replenishment from the Headquarters. If we mention that the reserves of the Headquarters, concentrated on the Western Front, were never used for their intended purpose, then such actions of General Brusilov, whose armies had enormous successes compared to their neighbors, seem quite logical and at least deserving of sympathetic attention.

Thus, official data is not a panacea for accuracy, and therefore, probably, it is necessary to look for a middle ground, relying, among other things, on archival documents (which, by the way, also tend to lie, especially with regard to the enemy’s always deliberately exaggerated losses), and on the testimony of contemporaries. In any case, it seems that in such controversial issues one can only speak of the most accurate approximation to the truth, but not about it in any way.

Unfortunately, certain figures presented by scientists, shown in the archives and, undoubtedly, in need of clarification, are further distributed in the literature already as the only true and having far-reaching consequences. At the same time, each such “subsequent distributor” adopts those figures (and they can be very different from each other, as in the example with the same Brusilov breakthrough - by half a million losses), which are beneficial for his own concept. Thus, it is indisputable that the great losses of the 1916 campaign of the year broke the will of the personnel of the Active Army to continue the struggle, and also influenced the mood of the rear. However, until the fall of the monarchy, the troops were preparing for a new offensive, the rear continued its work, and it would be premature to say that the state was collapsing. Without certain political events arranged by the liberal opposition, the morally broken country would obviously have continued the struggle until victory.

Let's take a concrete example. So, B. V. Sokolov, seeking (largely rightly) to combine in his conclusions the practice of warfare by Russia/USSR in the 20th century in relation to human losses, tries to name the extreme highest figures for both the First World War and the Great Patriotic War. Just because this is his concept - the Russians are waging war, "filling up the enemy with mountains of corpses." And if in relation to the Great Patriotic War, which B.V. Sokolov, in fact, is studying, these conclusions in the works are confirmed by certain calculations of the author (it doesn’t matter if they are correct or not, the main thing is that the calculations are carried out), then for the First World War they just take the numbers that are most suitable for the concept. Hence the general results of the struggle: “... finally undermined the power of the Russian army and provoked a revolution from a formal point of view, the successful offensive of the Russian imperial army- the famous Brusilovsky breakthrough. Huge irretrievable losses, significantly exceeding the enemy's, demoralized the Russian troops and the public. Further, it turns out that “significantly exceeding losses” is two to three times.

Various figures are given in Russian historiography, but no one says that Russian losses in the Brusilov breakthrough exceeded the losses of the Austro-Germans by two to three times. If, however, only B. V. Sokolov has in mind exclusively irretrievable losses, then the extreme figures he took are really present. Although, we repeat, one cannot count on the reliability of the Austro-German data, but meanwhile only they are presented almost as an ideal of military statistics.

Characteristic evidence: despite the mobilization during the Second World War of twenty percent of the population in the armed forces, irretrievable losses of troops Nazi Germany appear to be three to four million people. Even if we assume that the number of cripples is about the same, it is surprising to believe that in 1945 at least a ten million army could capitulate. With half the contingent after the Vyazemsky "cauldron", the Red Army overturned the Nazis in the Battle of Moscow in December 1941.

And these are the extreme figures of German statistics. Only in relation to Soviet losses are taken the highest extreme figures, and in relation to German - the lowest extreme figures. At the same time, Soviet losses are calculated by theoretical calculations based on the Books of Memory, where numerous overlays are inevitable, and German losses are simply based on official data. lower level counting. That's the whole difference - but how tempting is the conclusion about "filling up the enemy with corpses."

One thing is clear for sure: the Russian troops of the Southwestern Front in 1916 lost a lot of people, so many that this circumstance cast doubt on the possibility of achieving final victory in the war under the auspices of the regime of Nicholas II. According to the same Gen. N. N. Golovin, in 1916 the percentage of bloody losses was kept at the level of 85%, while in 1914-1915 it was only 60%. That is, without a doubt, the point is not so much in losses in general, but in the ratio of payment for the victory that beckoned. The replacement of the stunning successes of maneuvering battles with a stupid and utterly bloody frontal "meat grinder" could not but lower the morale of the soldiers and officers, who, unlike higher headquarters, understood everything perfectly. It was clear to the troops, but not to the headquarters, that a frontal offensive in the Kovel direction was doomed to failure.

In many ways, the heavy losses are explained by the fact that the Russian divisions were too "overloaded" with people compared to the enemy. Before the war, the Russian infantry division had sixteen battalions against twelve in the armies of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Then, during the Great Retreat of 1915, the regiments were reduced to a three-battalion structure. Thus, an optimal ratio was achieved between the human “content” of such a tactically independent unit as a division and the firepower of this tactical unit. But after the replenishment of the Active Army with recruits in the winter-spring of 1916, the fourth battalions of all regiments began to consist of recruits alone (in general, the Russian command could not refuse the fourth battalions, which only increased losses). The degree of supply of equipment remained at the same level. It is clear that the excess of infantry in frontal battles, which were also fought under the conditions of breaking through strong enemy defensive zones, only increased the number of unnecessary losses.

The essence of the problem here is that in Russia they did not spare human blood - the times of Rumyantsev and Suvorov, who beat the enemy "not by number, but by skill", have irrevocably passed. After these "Russian victorious" military "skill" of the commander inevitably provided for the proper "number". The commander-in-chief Gen. A. A. Brusilov said this about this: “I heard reproaches that I did not spare dear soldier's blood. I honestly cannot plead guilty to this. True, since the matter had begun, I urgently demanded that it be brought to a successful conclusion. As for the amount of blood spilled, it did not depend on me, but on the technical means that I was supplied from above, and it was not my fault that there were few cartridges and shells, there was a lack of heavy artillery, the air fleet was ridiculously small and of poor quality and etc. All such serious shortcomings, of course, influenced the increase in our losses in killed and wounded. But why am I here? There was no shortage of my urgent demands, and that was all I could do.”

It is unlikely that General Brusilov's references to the lack of technical means of combat can be put as an undoubted justification for huge losses. The stubbornness of the Russian attacks in the Kovel direction rather speaks of the lack of operational initiative at the headquarters of the Southwestern Front: having chosen a single object for strikes, the Russian side tried in vain to capture it even when it became clear that the prepared reserves would not be enough to attack Vistula and the Carpathians. How would it be necessary to develop a breakthrough to Brest-Litovsk and beyond, if those people who were trained during the period of positional calm had already died in these battles?

Nevertheless, such heavy losses, objectively, still have a justification. It was the First World War that became a conflict in which the means of defense immeasurably exceeded the means of attack in their power. Therefore, the advancing side suffered incomparably greater losses than the defending side, in the conditions of that "positional impasse" in which the Russian front froze from the end of 1915. In the event of a tactical breakthrough of defensive lines, the defender lost many people captured, but much less killed. The only way out was for the attacking side to achieve an operational breakthrough and deploy it into a strategic breakthrough. However, none of the sides managed to achieve this in the positional struggle.

An approximately similar ratio of losses was characteristic of the Western Front in the 1916 campaign of the year. So, in the Battle of the Somme, only on the first day of the offensive on July 1, according to the new style, the British troops lost fifty-seven thousand people, of which almost twenty thousand were killed. The British historian writes about this: "The British crown has not known a more severe defeat since the time of Hastings." The reason for these losses is the attack of the enemy defensive system that has been built and improved for more than one month.

The Battle of the Somme, an offensive operation by the Anglo-French on the Western Front to overcome the defense in depth of the Germans, took place at the same time as the offensive of the armies of the Russian Southwestern Front on the Eastern Front in the Kovel direction. During the four and a half months of the offensive, despite the high availability of technical means of combat (up to tanks in the second stage of the operation) and the prowess of the British soldiers and officers, the Anglo-French lost eight hundred thousand people. German losses - three hundred and fifty thousand, including one hundred thousand prisoners. Approximately the same loss ratio as in the troops of Gen. A. A. Brusilova.

Of course, we can say that the Russians still hit the Austrians, and not the Germans, whose qualitative potential of the troops was higher than that of the Austro-Hungarians. But after all, the Lutsk breakthrough stalled only when German units appeared on all the most important directions of the offensive of the Russian troops. At the same time, in the summer of 1916 alone, despite the fierce battles near Verdun and especially on the Somme, the Germans transferred at least ten divisions from France to the Eastern Front. And what are the results? If the Russian Southwestern Front moved forward 30-100 kilometers along a front 450 kilometers wide, then the British went deep into the territory held by the Germans only ten kilometers along a thirty-kilometer wide front.

We can say that the Austrian fortified positions were worse than the German ones in France. And this is also true. But the Anglo-French also had much more powerful technical support for their operation. In the number of heavy guns on the Somme and on the Southwestern Front, the difference was tenfold: 168 versus 1700. Again, the British did not feel the need for ammunition, like the Russians.

And, perhaps most importantly, no one questions the valor of British soldiers and officers. Here it is enough to recall that England gave her armed forces more than two million volunteers, that in 1916 there were almost exclusively volunteers at the front, and, finally, that the twelve and a half divisions that the British dominions gave to the Western Front also consisted of volunteers.

The essence of the problem is not at all in the inability of the generals of the Entente countries or the invincibility of the Germans, but in the very “positional impasse” that formed on all fronts of the First World War because the defense in combat terms turned out to be incomparably stronger than the offensive. It was this fact that forced the advancing side to pay for success with enormous blood, even with proper artillery support for the operation. As an English researcher absolutely rightly says, “in 1916, the German defense on the Western Front could not be overcome by any means at the disposal of the generals of the allied armies. Until some means are found to provide the infantry with closer fire escort, the scale of casualties will be enormous. Another solution to this problem would be to stop the war altogether.”

Siberian flying sanitary detachment

It remains only to add that the German defense was built just as irresistibly on the Eastern Front. That is why the Brusilovsky breakthrough stopped and the blow of the armies of the Western Front of Gen. A.E. Evert near Baranovichi. The only alternative, in our opinion, could only be "swinging" the enemy defense by permanently shifting the direction of the main attack, as soon as the previous such direction would be under the protection of a strong German grouping. This is the Lviv direction according to the directive of the Headquarters of May 27. This is the regrouping of forces in the 9th army of Gen. P. A. Lechitsky, against whom there was not enough German units. This is the timely use of Romania's entry into the war on the side of the Entente on August 14.

In addition, perhaps the cavalry should have been used to the maximum extent not as a shock group, but as a means of developing a breakthrough in the enemy defenses in depth. The lack of development of the Lutsk breakthrough, along with the desire of the headquarters of the Southwestern Front and personally the Glavkoyuz gene. A. A. Brusilov’s attack on the Kovel direction led to the incompleteness of the operation and excessive losses. In any case, the Germans would not have had enough troops to “plug all the holes”. After all, fierce battles were going on on the Somme, and near Verdun, and in Italy, and near Baranovichi, and Romania was also about to enter the war. However, this advantage was not used on any of the fronts, although it was the Russian Southwestern Front, with its brilliant tactical breakthrough, that received the greatest opportunity to break the back of the armed forces of the Central Powers.

One way or another, the Russian casualties of the 1916 campaign of the year had a lot of important consequences for the further development of events. Firstly, the huge losses that bled the armies of the Southwestern Front did not significantly change the general strategic position of the Eastern Front, in connection with which V.N. November 1917". He is echoed by Gen. A. S. Lukomsky, head of the 32nd Infantry Division, which fought as part of the Southwestern Front: “The failure of the operation in the summer of 1916 had the consequence not only that the entire campaign was dragged out, but the bloody battles of this period had a bad effect on moral condition of the troops. In turn, the future Minister of War of the Provisional Government, Gen. A. I. Verkhovsky generally believed that “we could have ended the war this year, but we suffered “huge, incommensurable losses.”

Secondly, the death of soldiers and officers trained during the winter, drafted into the Armed Forces after the failed campaign of 1915, meant that the advance to the west would again, as in 1914, be fueled by hastily prepared reserves. It is unlikely that such a position was a way out of the situation, but for some reason in Russia they did not make a difference between first-line and second-line divisions, between personnel and militia regiments. They almost did not, believing that once the task was set, it must be completed at any cost, regardless of the cost of victory on a given sector of the front.

Undoubtedly, a successful breakthrough to Kovel should have formed a huge "hole" in the Austro-German defense. The armies of the Western Front, Gen. A. E. Evert. And in the event of a successful advance, the troops of the Northern Front, Gen. A. N. Kuropatkin (in August - N. V. Ruzsky). But after all, all this could have been achieved by a strike on a different sector of the Southwestern Front. On what was the least fortified, less saturated with German divisions, it would have a greater range of alternatives regarding the development of a breakthrough.

However, as if in mockery, the Russian command preferred to overcome the enemy's defenses along the line of greatest resistance. And this is after an outstanding victory! Approximately the same thing will happen in 1945, when, after the dazzling Vistula-Oder offensive operation, the Soviet command rushed to storm Berlin head-on, through the Seelow Heights, although the offensive of the armies of the 1st Ukrainian Front provided much greater success with much lower losses. True, in 1945, unlike in 1916, the matter ended in victory, and not in repelling the attacks of our side, but what was the price.

So, the blood price of the troops for the victory of the Brusilov breakthrough was inconsistent with anything, and in addition, the victories in the shock army actually ended in June, although the attacks continued for another three months. However, the lessons were taken into account: for example, at the Meeting of the senior command staff at Headquarters on December 17, 1916, it was recognized that unnecessary losses only undermine the mobilization capabilities of the Russian Empire, which were already close to exhaustion. It was recognized that it was necessary "to be extremely attentive to operations so that there are no unnecessary losses ... operations cannot be carried out where it is unprofitable in tactical and artillery terms ... no matter how advantageous the direction of the strike is in strategic terms."

The main consequence of the outcome of the 1916 campaign was the deliberately wrong and unfair thesis perceived by the Russian society about the decisive undermining of the prestige and authority of the existing state power in the sense of ensuring the final victory in the war. If in 1915 the defeats of the Army in the Field were due to shortcomings in equipment and ammunition, and the troops, who understood everything perfectly, nevertheless fought with complete faith in ultimate success, then in 1916 there was almost everything, and the victory again slipped out of hands. And here we are not talking about victory on the battlefield in general, but about the dialectical correlation of victory, the price for it, as well as the visible prospect of a final favorable outcome of the war. Distrust in commanders raised doubts about the possibility of achieving victory under the auspices of the existing supreme power, which in the period described was authoritarian-monarchical and headed by Emperor Nicholas II.

From the book In the fight with the "wolf packs". US Destroyers: War in the Atlantic the author Roscoe TheodoreSummary The influence of anarchonomics in your market will be established and strengthened in the future by several factors. The capacity and power of computers will increase. Mobile Internet connectivity will also become more widespread. As a result, more effective ways

From the book Another chronology of the disaster of 1941. The fall of the "Stalin's falcons" author Solonin Mark SemyonovichResults The significance of the Korean War was colossal. The United States became involved in the war on the Asian mainland. They fought in a conventional war with the Chinese, who had inexhaustible manpower, far exceeding the capabilities of the United States. Never before

From the book Wings of Sikorsky author Katyshev Gennady IvanovichResults of the operation 1. Losses in shipsARGENTINA Cruiser "General Belgrano" + submarine "Santa Fe" ++ Patr. boat "Islas Malvinas" ++ Patr. boat "Rio Iguazu" + Transport "Rio Carcarana" + Transport "Islas de los Estados" + Transport "Monsumen" washed ashore, raised, but decommissioned

From the book Live in Russia author Zaborov Alexander VladimirovichSome results By the end of the summer of 1944, the submarine war was practically over. The German boats were completely unable to cut the communications from America to the new front in Europe. Great amount transport, necessary for the normal supply

From the book Three Colors of the Banner. Generals and Commissars. 1914–1921 author Ikonnikov-Galitsky Andrzej1.6. Summary and Discussion At the very beginning of Chapter 4, we discussed some characteristics fighting in the Baltics. Now I want to draw the reader's attention to two remarkable features in the depiction and perception of the history of these events. In the summer of the 41st among

From the book In Search of Eldorado author Medvedev Ivan Anatolievich From the book Russian mafia 1991–2014. The latest history of gangster Russia author Karyshev Valery From the book The collapse of the Barbarossa plan. Volume II [Foiled Blitzkrieg] author Glantz David MResults Snesarev was placed at the head of the Academy just when Denikin's offensive against Moscow was unfolding. The offensive ended in disaster; White rolled back to Belgorod and Kharkov. In November 1919, Denikin appointed his enemy Wrangel commander

From the author's bookResults Lasting two years and ten months, the first English round the world expedition became the most profitable commercial venture in the history of navigation. Elizabeth I and other shareholders received a 4700% return on invested capital. Cost brought by Drake

From the author's bookResults in the Ministry of Internal Affairs Speaking at the board of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Moscow, dedicated to the results of the work of the police in 2013, the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Kolokoltsev, harshly criticized the actions of law enforcement officers. It turned out that, having achieved generally good results in their work, they were engaged in

From the author's bookCHAPTER 10 Summary When the German Wehrmacht rushed east into the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, embarking on the implementation of the Barbarossa plan, the German Chancellor Adolf Hitler, his generals, most Germans and a significant part of the population of the Western countries expected an ambulance

Brusilovsky breakthrough is an offensive operation of the troops of the Southwestern Front (SWF) of the Russian army on the territory of modern Western Ukraine during the First World War. Prepared and implemented, starting from June 4 (May 22, old style), 1916, under the leadership of the commander-in-chief of the armies of the South-Western Front, cavalry general Alexei Brusilov. The only battle of the war, in the name of which the name of a specific commander appears in the world military historical literature.

By the end of 1915, the countries of the German bloc - the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey) and the Entente alliance opposing them (England, France, Russia, etc.) found themselves in a positional impasse.

Both sides have mobilized almost all available human and material resources. Their armies suffered colossal losses, but did not achieve any serious success. Both in the western and in the eastern theater of the war a continuous front was formed. Any offensive with decisive goals inevitably presupposed a breakthrough in the enemy's defense in depth.

In March 1916, the Entente countries at a conference in Chantilly (France) set the goal of crushing the Central Powers by coordinated strikes before the end of the year.

For the sake of achieving it, the Headquarters of Emperor Nicholas II in Mogilev prepared a plan for a summer campaign, based on the possibility of advancing only to the north of Polesie (swamps on the border of Ukraine and Belarus). The main blow in the direction of Vilna (Vilnius) was to be delivered by the Western Front (ZF) with the support of the Northern Front (SF). The South-Western Front, weakened by the failures of 1915, was instructed to tie down the enemy with defense. However, at the military council in Mogilev in April, Brusilov obtained permission to attack too, but with private tasks (from Rovno to Lutsk) and relying only on his own strength.

According to the plan, the Russian army acted on June 15 (June 2, old style), but due to increased pressure on the French near Verdun and the May defeat of the Italians in the Trentino region, the Allies asked the Headquarters to start earlier.

The SWF united four armies: the 8th (cavalry general Alexei Kaledin), the 11th (cavalry general Vladimir Sakharov), the 7th (infantry general Dmitry Shcherbachev) and the 9th (infantry general Platon Lechitsky). In total - 40 infantry (573 thousand bayonets) and 15 cavalry (60 thousand sabers) divisions, 1770 light and 168 heavy guns. There were two armored trains, armored cars and two Ilya Muromets bombers. The front occupied a strip about 500 kilometers wide south of Polissya to the Romanian border, the Dnieper served as a rear line.

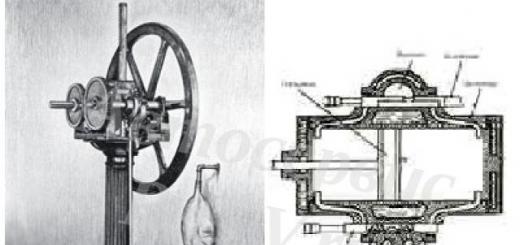

The opposing enemy group included the army groups of the German Colonel General Alexander von Linsingen, the Austrian Colonel Generals Eduard von Böhm-Ermoli and Karl von Plyantser-Baltin, as well as the Austro-Hungarian Southern Army under the command of the German Lieutenant General Felix von Bothmer. In total - 39 infantry (448 thousand bayonets) and 10 cavalry (30 thousand sabers) divisions, 1300 light and 545 heavy guns. The infantry formations had more than 700 mortars and about a hundred "new products" - flamethrowers. Over the previous nine months, the enemy had equipped two (in places - three) defensive zones three to five kilometers from one another. Each lane consisted of two or three lines of trenches and resistance units with concrete dugouts and had a depth of up to two kilometers.

Brusilov's plan provided for the main attack by the forces of the right-flank 8th Army on Lutsk with simultaneous auxiliary strikes with independent targets in the bands of all other armies of the front. This ensured operational camouflage of the main attack, excluding the maneuver of enemy reserves and their concentrated use. In 11 sectors of the breakthrough, a significant superiority in forces was ensured: for infantry - up to two and a half times, for artillery - one and a half times, and for heavy - two and a half times. Observance of camouflage measures ensured operational surprise.

Artillery preparation in different sectors of the front lasted from six to 45 hours. The infantry started the attack under cover of fire and moved in waves - three or four chains every 150-200 steps. The first wave, not lingering on the first line of enemy trenches, immediately attacked the second. The third line was attacked by the third and fourth waves, which rolled over the first two (this tactic was called the "roll attack" and was subsequently used by the Allies).

On the third day of the offensive, the troops of the 8th Army occupied Lutsk and advanced to a depth of up to 75 kilometers, but later ran into stubborn resistance from the enemy. Parts of the 11th and 7th armies broke through the front, but due to the lack of reserves they could not build on their success.

However, the Headquarters was unable to organize the interaction of the fronts. The offensive of the ZF (Infantry General Alexei Evert), planned for the beginning of June, began a month late, was carried out indecisively and ended in complete failure. The situation demanded the transfer of the main attack to the zone of the South-Western Front, but the decision on this was made only on July 9 (June 26, old style), when the enemy had already brought up large reserves from the western theater. Two attacks on Kovel in July (by the forces of the 8th and 3rd armies of the Polar Front and the strategic reserve of the Headquarters) resulted in protracted bloody battles on the Stokhid River. At the same time, the 11th Army occupied Brody, and the 9th Army cleared Bukovina and Southern Galicia from the enemy. By August, the front had stabilized on the line of the Stohod-Zolochev-Galych-Stanislav river.

Brusilov's frontal breakthrough played a big role in the overall course of the war, although operational successes did not lead to decisive strategic results. During the 70 days of the Russian offensive, the Austro-German troops lost up to one and a half million people killed, wounded and captured. The losses of the Russian armies amounted to about half a million.

The forces of Austria-Hungary were seriously undermined, Germany was forced to transfer more than 30 divisions from France, Italy and Greece, which alleviated the position of the French at Verdun and saved the Italian army from defeat. Romania decided to go over to the side of the Entente. Along with the battle on the Somme, the operation of the SWF marked the beginning of a turning point in the war. From the point of view of military art, the offensive marked the appearance new form breakthrough of the front (simultaneously in several sectors), put forward by Brusilov. The Allies used his experience, especially in the 1918 campaign in the western theater.

For the successful leadership of the troops in the summer of 1916, Brusilov was awarded the golden St. George weapon with diamonds.

In May-June 1917, Alexei Brusilov acted as commander-in-chief of the Russian armies, was a military adviser to the Provisional Government, and later voluntarily joined the Red Army and was appointed chairman of the Military Historical Commission for the study and use of the experience of the First World War, since 1922 - chief cavalry inspector of the Red Army. He died in 1926 and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

In December 2014, sculptural compositions dedicated to the First World War and the Great Patriotic wars. (The author is Mikhail Pereyaslavets, sculptor of the M. B. Grekov Studio of Military Artists). The composition, dedicated to the First World War, depicts the largest offensive operations of the Russian army - the Brusilovsky breakthrough, the siege of Przemysl and the assault on the Erzurum fortress.

The material was prepared on the basis of information from RIA Novosti and open sources

Brusilovsky breakthrough

Brusilovsky breakthrough- the offensive operation of the Southwestern Front of the Russian army under the command of General A. A. Brusilov during the First World War, carried out on May 21 (June 3) - August 9 (22), 1916, during which the Austro-Hungarian army was seriously defeated and Galicia and Bukovina are occupied.

Operation planning and preparation

The summer offensive of the Russian army was part of the general strategic plan of the Entente for 1916, which provided for the interaction of the allied armies in various theaters of war. As part of this plan, the Anglo-French troops were preparing an operation on the Somme. In accordance with the decision of the conference of the powers of the Entente in Chantilly (March 1916), the start of the offensive on the French front was scheduled for July 1, and on the Russian front - for June 15, 1916.

The directive of the Russian General Headquarters of April 11 (24), 1916 appointed the Russian offensive on all three fronts (Northern, Western and Southwestern). The balance of power, according to the Headquarters, was in favor of the Russians. At the end of March, the Northern and Western Fronts had 1,220,000 bayonets and cavalry against the Germans' 620,000; the Southwestern Front had 512,000 against the Austrians' 441,000. The double superiority of forces north of Polissya dictated the direction of the main attack. It was supposed to be delivered by the troops of the Western Front, and auxiliary strikes - by the Northern and South-Western Fronts. In order to increase the superiority in forces in April-May, the units were understaffed to full strength.

Russian infantry on the march |

The Headquarters was afraid that the armies of the Central Powers would go on the offensive in the event of the defeat of the French near Verdun and, wanting to seize the initiative, instructed the front commanders to be ready for the onset ahead of schedule. The directive of the Stavka did not reveal the purpose of the forthcoming operation, did not provide for the depth of the operation, did not indicate what the fronts were to achieve in the offensive. It was believed that after breaking through the first line of enemy defenses, a new operation was being prepared to overcome the second line. This was reflected in the planning of the operation by the fronts. Thus, the command of the Southwestern Front did not determine the actions of its armies in the development of a breakthrough and further goals.

Contrary to the assumptions of the Headquarters, the Central Powers did not plan major offensive operations on the Russian front in the summer of 1916. At the same time, the Austrian command did not consider it possible for the Russian army to successfully advance south of Polesie without its significant reinforcement.

By the summer of 1916, the Russian army showed signs of fatigue of the soldier masses from the war, but in the Austro-Hungarian army the unwillingness to fight was much stronger, and in general the combat effectiveness of the Russian army was higher than that of the Austrian.

On May 2 (15), Austrian troops went on the offensive on the Italian front in the Trentino region and defeated the Italians. In this regard, Italy turned to Russia with a request to help the offensive of the armies of the Southwestern Front, which was opposed mainly by the Austrians. On May 18 (31), the Headquarters, by its directive, scheduled the offensive of the Southwestern Front for May 22 (June 4), and the Western Front - for May 28-29 (June 10-11). The main strike was still assigned to the Western Front (commander General A.E. Evert).

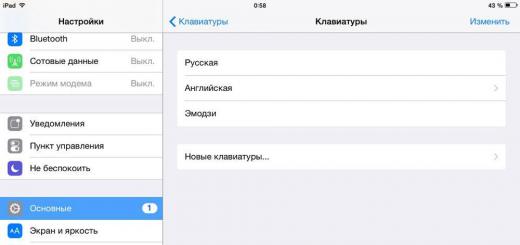

In preparation for the operation, the commander of the Southwestern Front, General A. A. Brusilov, decided to make one breakthrough on the front of each of his four armies. Although this scattered the Russian forces, the enemy also lost the opportunity to transfer reserves in a timely manner to the direction of the main attack. In accordance with the general plan of the Headquarters, the strong right-flank 8th Army delivered the main blow to Lutsk to assist the planned main blow of the Western Front. The army commanders were given the freedom to choose breakthrough sites. In the directions of the army strikes, superiority over the enemy in manpower (by 2-2.5 times) and in artillery (by 1.5-1.7 times) was created. The offensive was preceded by thorough reconnaissance, training of troops, equipment of engineering bridgeheads, which brought Russian positions closer to Austrian ones.

Operation progress

Artillery preparation continued from 03:00 on May 21 (June 3) to 09:00 on May 23 (June 5) and led to the severe destruction of the first line of defense and the partial neutralization of enemy artillery. The Russian 8th, 11th, 7th, and 9th Armies, which then went on the offensive (over 633,000 men and 1,938 guns), broke through the positional defenses of the Austro-Hungarian front, commanded by Archduke Friedrich. The breakthrough was carried out immediately in 13 areas with subsequent development towards the flanks and in depth.

The greatest success at the first stage was achieved by the 8th Army (commanded by General A. M. Kaledin), which, having broken through the front, occupied Lutsk on May 25 (June 7), and by June 2 (15) defeated the 4th Austro-Hungarian Army of the Archduke Joseph Ferdinand and advanced 65 km.

The 11th and 7th armies broke through the front, but the offensive was halted by enemy counterattacks. The 9th Army (commanded by General P. A. Lechitsky) broke through the front of the 7th Austro-Hungarian Army and occupied Chernivtsi on June 5 (18).

The threat of an offensive by the 8th Army on Kovel forced the Central Powers to transfer two German divisions from the Western European theater to this direction, two Austrian divisions from the Italian front, and a large number of units from other sectors of the Eastern Front. However, the counterattack of the Austro-German troops against the 8th Army launched on June 3 (16) was not successful.

At the same time, the Western Front was postponing the main attack prescribed for it by the Headquarters. With the consent of the Chief of the General Staff, General M.V. Alekseev, General Evert postponed the date of the offensive of the Western Front until June 4 (17). The private attack of the 1st Grenadier Corps on a wide sector of the front on June 2 (15) was unsuccessful, and Evert began a new regrouping of forces, due to which the offensive of the Western Front was postponed to the beginning of July. Applying to the changing timing of the offensive on the Western Front, Brusilov gave the 8th Army more and more new directives - either of an offensive or defensive nature, to develop a strike first on Kovel, then on Lvov.

By 12 (25) June, a relative calm had set in on the Southwestern Front. On June 24, the artillery preparation of the Anglo-French armies on the Somme began, which lasted 7 days, and on July 1 the Allies went on the offensive. The operation on the Somme required Germany to increase the number of its divisions in this direction from 8 to 30 in July alone.

The Russian Western Front finally went on the offensive on June 20 (July 3), and the Southwestern Front resumed the offensive on June 22 (July 5). Dealing the main blow to the large railway junction of Kovel, the 8th Army reached the line of the river. Stokhod, but in the absence of reserves, she was forced to stop the offensive for two weeks.

|

The attack on Baranovichi by the shock group of the Western Front, undertaken on June 20-25 (July 3-8) by superior forces (331 battalions and 128 hundreds against 82 battalions of the 9th German Army) was repulsed with heavy losses for the Russians. The offensive of the Northern Front from the Riga bridgehead also turned out to be unsuccessful, and the German command continued to transfer troops from areas north of Polesie to the south.

In July, the Stavka transferred the guards and the strategic reserve to the south, creating the Special Army of General Bezobrazov, and ordered the Southwestern Front to take Kovel. On July 15 (28), the SWF launched a new offensive. The attacks of the fortified marshy defile on Stohod against the German troops ended in failure. The 11th Army of the SWF took Brody, and the 7th Army took Galich. Significant success was achieved in July-August by the 9th Army of General N. A. Lechitsky, who occupied Bukovina and took Stanislav.

By the end of August, the offensive of the Russian armies stopped due to the increased resistance of the Austro-German troops, as well as heavy losses and fatigue of the personnel.

Results

As a result of the offensive operation, the Southwestern Front inflicted a serious defeat on the Austro-Hungarian troops in Galicia and Bukovina. The losses of the Central Powers, according to Russian estimates, amounted to about one and a half million people killed, wounded and captured. The high losses suffered by the Austrian troops further reduced their combat capability. To repel the Russian offensive, Germany transferred 11 infantry divisions from the French theater of operations, and Austria-Hungary from the Italian front - 6 infantry divisions, which became a tangible help to Russia's allies in the Entente. Under the influence of the Russian victory, Romania decided to enter the war on the side of the Entente, although the consequences of this decision are ambiguously assessed by historians.

The result of the offensive of the Southwestern Front and the operation on the Somme was the final transfer of the strategic initiative from the Central Powers to the Entente. The Allies managed to achieve such interaction in which for two months (July-August) Germany had to send its limited strategic reserves to both the Western and Eastern fronts.

At the same time, the summer campaign of the Russian army in 1916 demonstrated serious shortcomings in command and control. The headquarters was unable to implement the plan agreed with the allies for a general summer offensive of three fronts, and the auxiliary strike of the Southwestern Front turned out to be the main offensive operation. The offensive of the Southwestern Front was not promptly supported by other fronts. The headquarters did not show sufficient firmness in relation to General Evert, who repeatedly disrupted the scheduled dates for the offensive of the Western Front. As a result, a significant part of the German reinforcements against the South-Western Front came from other sectors of the Eastern Front.

The July offensive of the Western Front on Baranovichi revealed the inability of the commanding staff to cope with the task of breaking through the heavily fortified German position, even with a significant superiority in forces.

Since the Lutsk breakthrough of the 8th Army in June was not envisaged by the Stavka plan, it was not preceded by the concentration of powerful front-line reserves, so neither the 8th Army nor the South-Western Front could develop this breakthrough. Also, due to the fluctuations of the Headquarters and the command of the South-Western Front, during the July offensive, the 8th and 3rd armies reached the river by July 1 (14). Stokhod without sufficient reserves and were forced to stop and wait for the approach of the Special Army. Gave two weeks of respite German command time to transfer reinforcements, and subsequent attacks by Russian divisions were repulsed. "The impulse does not tolerate a break."