75 years ago, from November 28 to 30, 1943, a conference of leaders of the countries of the anti-Hitler coalition took place

In 2017, the Eksmo publishing house published Susan Butler’s book “Stalin and Roosevelt. The Great Partnership." To date, it represents the most complete study of the history of the relationship between the two main figures of the Second World War. Two political giants, representing two opposing social worlds, but realizing the need for a trusting partnership not only in the fight against German fascism, but also in the post-war world without wars.

S. Butler’s book is valuable not only because it contains previously unknown details of the meetings between Stalin and Roosevelt, but, as we see it, primarily because of the author’s immersion into the distant past, which allows us to see what kind of reality the post-war world could have become if not for the sudden death of F. Roosevelt. Let's say what is generally known: history does not know the subjunctive mood, but this does not mean that it does not suggest an alternative to what has already happened. Will the modern course of history allow us to return to the lost possibility of a world without war - this question becomes inevitable when reading Susan Butler's book.

A path halfway around the world

The first meeting between Stalin and Roosevelt took place on November 28, 1943 in Tehran. It became possible after the victory of the Red Army in the grandiose Battle of Kursk. Prior to this, Stalin had rejected all proposals from the US President for a personal meeting, which, as the author of the book notes, he, Roosevelt, “tried to organize for two years and for which he made enormous efforts and traveled enormous distances.” For the US President, this required considerable stoicism and courage, considering that in 1921, at the age of 39, he fell ill with polio - infectious infantile paralysis. Roosevelt became crippled and was doomed to move in a special wheelchair with the help of people close to him. The meeting with Stalin in Tehran obliged him to cover a distance of 17,442 miles. In other words, to make a journey more than half the world across the waters of the Atlantic Ocean on the battleship Iowa (it was accompanied by nine destroyers and one aircraft carrier, constantly monitored by a group of fighters), as well as by air on an airplane.

Before Tehran, Roosevelt proposed to Stalin various options Possible meeting places: Iceland, southern Algeria, Khartoum, Bering Strait, Fairbanks in Alaska, Cairo and Basra. Stalin rejected all these proposals due to their great distance from Moscow, where he daily performed the duties of Supreme Commander-in-Chief. Finally he told Roosevelt: “For me, as Commander-in-Chief, the possibility of going beyond Tehran is excluded.” The US President rejected this meeting place - too far from Washington. But three days later he very reluctantly agreed.

Roosevelt, as S. Butler focuses on, sought a personal meeting with Stalin, as they say, face to face, without the participation of Churchill. We can say that he sought the location of his mission on the territory of the Soviet embassy in Tehran. In his message to Stalin, he directly posed to him a seemingly random but acute question: “Where, in your opinion, should we live”? As S. Butler writes, “he did not want the Prime Minister of Great Britain, the former Colonial Secretary of the largest colonial empire in the world, to hang as a burden around his neck. That is why, even at the conference in Cairo, he notified the British “that he wishes to have freedom of action in Tehran.”

Stalin was in no hurry to respond, but in the end made an offer to the American president to settle on Soviet territory. This "caused Churchill considerable mental pain." “Roosevelt made a long and dangerous journey to Tehran to meet Stalin,” says S. Butler. “And in order for his plan to be realized, it was necessary to distance himself from Churchill,” which is what he did in Tehran, which will be discussed further. Roosevelt sought Stalin's trust, lasting and complete trust. Why? This was in the interests of the United States of America, the imperialist interests that Franklin Delano Roosevelt served. He understood well, according to S. Butler: “The war unpredictably changed all countries. After the war there were only two superpowers left: America and Russia.”

The main reason for the personal meeting of the US President with the Soviet leader

Roosevelt was a far-sighted politician and could not accept the victories of the Red Army at Stalingrad and Kursk Bulge otherwise, as, first of all, the victory of the industrial Urals over the industrial Ruhr. About how powerful the military potential of Nazi Germany still was after Stalingrad, before and after Battle of Kursk, can be judged by the production of German aircraft and tanks in 1943-1944. In 1943, 25,527 combat aircraft and 5,995 tanks arrived at the front; in 1944, respectively, 39,807 aircraft and 8,344 tanks. The USSR surpassed Germany in tank production in 1943, convincing proof of which was the unprecedented tank battle near Prokhorovka: the Soviet T-34 prevailed over the German Tiger. In terms of the number of aircraft, Soviet aviation surpassed German aviation in 1944.

Before meeting with Stalin in Tehran, Roosevelt, with his practicality and strategic insight, was not difficult to guess that the Soviet power had the opportunity to defeat fascist Germany and on your own. Perhaps the first person to foresee such a very likely outcome of the war against the USSR was Hitler. This is precisely what can explain his decision to treacherously attack the Soviet country. No matter how paradoxical it may seem, given the adventurousness of his mind, it is Hitler who has priority in a realistic assessment of the growing industrial, and therefore military, power of the USSR. After the treacherous and initially successful invasion of the Soviet country, he admitted to his closest circle: “The more we learn about Soviet Russia, the more we rejoice that we delivered the decisive blow in time. After all, in the next ten years the Soviet Union would create many industrial centers of an unattainable level. It is impossible to imagine what kind of weapons the Soviets would have acquired while Europe continued to steadily degrade. Stalin, of course, should be treated with due respect. He's kind of a genius. His plans for economic development are so large-scale that only four-year (German - Yu.B.) plans can surpass them. The strength of the Russian people does not lie in its numbers or organization, but in its ability to produce personalities on the scale of Stalin.”

And as if giving characteristics to the main acting persons At the Tehran Conference, Hitler argued: “In his political and military qualities, Stalin surpasses both Churchill and Roosevelt. This is the only world politician worthy of respect.” As we see, objective and subjective factors were taken into account by our main opponent. Regarding taking into account the growing industrial and military power Soviet Union, then Roosevelt did this before Hitler, when he established diplomatic relations with our state.

Roosevelt was well aware of the enormous industrialization of the USSR: he authorized the largest Soviet orders of industrial equipment of the highest technological level during the years of depression in the American economy. He knew about the complex internal political struggle in Soviet Russia: about political repression, the difficulties and costs of collectivization... He knew everything, but this knowledge of his now, before meeting with Stalin in Tehran after the great victory of the Red Army at Kursk, had no meaning for him.

Yes, in 1930, adhering to bourgeois political stencils, he compared Stalin with Mussolini, and in 1940 he declared that he, Stalin, was guilty of “mass murders of thousands of innocent people.” All this was in a ritual anti-communist spirit. However, in front of Tehran, he did not want to remember this. Roosevelt was aware historical role Stalin in world politics, his unquestioned authority in Soviet society and his growing popularity in the world after Stalingrad and Kursk. He also knew that the moral and political unity of the people of the USSR, which has no analogues among other peoples of the world, served as the basis for unparalleled mass heroism at the front and in the rear, without which industrial power would have been only a potential force.

Roosevelt, as a realist politician, and he was one, could not help but take Stalin into account in resolving fateful issues of world politics. As for Churchill, Roosevelt the realist treated him as an ideologist and politician of the largest colonial empire that had become obsolete. The US President saw himself as the leader of the post-war world (it was no coincidence that in Tehran he spoke about a world government), the leader of the most powerful imperialist power.

This is exactly how Susan Butler presents him to readers of her book. She categorically states: “Roosevelt needed Stalin, and, as Roosevelt assumed, Stalin also (perhaps even more) needed him.” And then even more categorically, without allowing the slightest objection: “For the first time since Lenin, Stalin met a person more influential than himself. Roosevelt was a president elected for a third term (an unprecedented case!), leading a country that at that time had the most efficient industry in the world, which was now the main support for the Soviet Union. This man, this cripple, who did not look or act like a cripple, whose clothes fit so well that sitting on the sofa he seemed not only physically normal but also elegant, had come thousands of miles to meet him . And now he was located, practically on his own initiative, in Stalin’s representative office. What, naturally, should Stalin have thought? This president was a man of strong character.”

From the pen of S. Butler, Roosevelt appears to us as a respectable master of the situation at the Tehran meeting. She admires and enjoys the image of Franklin Delano Roosevelt she created - FDR, as he was called in his inner circle. Of course, he was a great politician and deserves high recognition from history. But his desire to see America’s superiority in everything was not always justified and realistic. So, he had no doubt that the American soldier would be the first to enter Berlin. On November 19, 1943, Roosevelt declared: “Certainly there will be a race for Berlin... But Berlin must be taken by the United States.” However, this was not destined to come true.

Failure of Churchill's plans

But let us turn to the main thing for which Roosevelt sought a meeting with Stalin - to issues whose solution would determine the achievement of a speedy victory over Nazi Germany and a safe world structure. There were two of them: the landing of the Anglo-American troops in northern France (“second front” - Operation Overlord) and the creation of the influential United Nations Organization (UN). There could be no agreement with Churchill on these issues, since he was worried about saving the world's largest colonial empire, Great Britain.

Roosevelt defiantly sought to “present America as the main driving force in the world.” “He,” notes S. Butler, “did not want to preserve British Empire, he advocated that it be destroyed." Moreover, he was convinced that "former colonial possessions should be governed by a collective body such as the United Nations." American imperialism confidently declared its first role in the capitalist world and no longer took into account the weakened English lion. He recognized the strength of the new superpower and therefore intended to resolve the main issues of world politics only with it. This is precisely what must be seen behind the charm and charming smile with which Roosevelt greeted Stalin during their personal conversations in Tehran.

Following S. Butler, we also note that the US President’s sympathy for the leader of the Soviet people, his emphasized respect for him, were based on extremely highly appreciated intellectual and strong-willed qualities Stalin's personality. Here are just a few of Roosevelt’s statements about him, contained in the book: “Working with him is a pleasure. No extravagances. He clearly states the issue he wants to discuss and does not deviate anywhere”; “This man combines a huge, unyielding will and a healthy sense of humor. I think the soul and heart of Russia have their true representative in him”; "This is a man carved from granite."

What about Winston Churchill? This major bourgeois politician of the era of colonialism, who had a penetrating mind, talent as an orator and polemicist, a brilliant writer, a gifted painter, a man of great personal courage (in his youth he looked death in the face more than once), with enviable energy, despite his advanced age, in short - an outstanding personality (!), ended up playing a supporting role in Tehran. It is clear why: colonial England was living out its days. That is why his desire to delay Operation Overlord as long as possible, replacing it with an offensive in the Mediterranean theater of war (liberate Italy, take Rome), and withdraw Anglo-American troops through the Balkans to Eastern Europe, in order to prevent the Red Army there, was not supported by Roosevelt, not to mention Stalin. His attempt to replace the UN with organizations of regional unions, where England could still play a leading role, was also unsuccessful in Tehran.

England did not have the opportunity to lay claim to the role of a superpower, and Churchill had no choice but to agree with Stalin and Roosevelt to carry out Operation Overlord no later than May 1944. This was the main result of the Tehran Conference. As S. Butler writes: the British Prime Minister was despondent, Marshal Stalin was in an excellent mood.

Stalin's will and determination

It would be a mistake to believe that the agreement between Stalin and Roosevelt on the main issues of the conference predetermined the ease of their solution. First of all, Churchill stubbornly defended his positions, hoping for class solidarity with Roosevelt. Moreover, the latter did not expect from Stalin that ability that he himself did not possess - a military mentality. As General Brooke, an expert on military issues from England, noted in his diary: “Not once in any of his calculations did he (Stalin - Yu.B.) make any strategic mistakes.”

The US President, having made a fundamental decision on Operation Overlord, did not consider it possible to clarify such “details” as establishing the exact time of its start and the appointment of the commander-in-chief of the Anglo-American troops for the period of its implementation. This played into Churchill’s hands: the more uncertainty there is in the “details,” the more likely it is to delay the opening of the “second front.”

Let's give credit to S. Butler: she presented the decisive and leading role of Stalin in concretizing the decision on Operation Overlord. Let's look at the text of the book:

“Stalin entered the conversation. - Who will lead Operation Overlord? - he asked.

Roosevelt replied that the decision had not yet been made.

Then Stalin said rather sharply:

“Then nothing will come of this operation.”

“In the end, after a long argument with the Prime Minister of England, the US President had to give assurances that a decision on the leader of Operation Overlord and its start date would be made in the coming days.”

With all her adoration for US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, S. Butler presented the gigantic figure of Stalin at the Tehran Conference. She did this with the help of the then US Secretary of Defense Stimson, citing the following diary entry: “I thank the Lord that Stalin was there. In my opinion, he saved the situation. He was direct and decisive and energetically rejected all attempts by the Prime Minister to divert the negotiations, which made my heart happy. By the time he arrived, our side was at a disadvantage. Firstly, because the president had rather weak control over the situation and influenced it rather haphazardly, and secondly, because Marshall (Chief of Staff of the US Armed Forces - Yu.B.), who bears full responsibility, is persistently trying more or less stays away because he feels that he is an interested party. Therefore, the first meeting, held before Stalin’s arrival, as could be understood from the protocols, turned out to be quite discouraging, without results clearly coordinated by our representatives. But when Stalin appeared with his general Voroshilov, they were able to completely change the situation, since they went on the offensive, defending the need for Operation Overlord. They supported the idea of holding an auxiliary offensive operation in the south of France and spoke out categorically against diversionary actions in the eastern Mediterranean. Ultimately, Stalin emerged victorious that day, and I was delighted with this.”

Roosevelt admitted: in negotiations with Stalin, he did not expect strict pedantry from him. It's understandable. If the American president thought about the lives of American soldiers (after Stalin’s assurance that the USSR would enter the war with Japan at the end of the defeat of the Third Reich, the president said: “Now I am calm: two million Americans will be alive”), then the leader of the Soviet people thought about the lives of his compatriots with with even greater passion, knowing what a terrible grief of loss they had to endure.

The idea of the UN and US world domination

On the issue of the United Nations - Roosevelt's main idea at the Tehran conference - he received the support of Stalin, which irritated Churchill. The latter was aware that this organization, by the very fact of its existence, would contribute to the independence of colonially dependent countries and thereby strengthen the dominant role of the United States of America in the capitalist world, and contribute to the transformation of the USSR into an influential factor in world politics. England will have no choice but to follow the lead of US international policy.

This is how it happened and is still happening today, with the only difference that after the death of Winston Churchill, England never again had such a major politician as him. The same can be said about France, remembering de Gaulle, and about the United States after the death of Roosevelt: capitalism at the stage of imperialism became an increasingly reactionary force.

It is impossible not to note the progressive nature of the United Nations conceived by Roosevelt. With its creation, he affirmed the policy of peaceful coexistence of two opposing social worlds: capitalism and socialism. How long such a policy could actually last is a question to which we will return. But the attempt to declare the principle of peaceful coexistence, undoubtedly, was the historical merit of the last outstanding US president, who paved the way for the great partnership of the two superpowers. Nothing like this happened after his death. Today, the USA and the Russian Federation have the kind of leaders that their people deserve in their current state. Then there was a time of political giants, and now...

We dare to make one more assumption regarding Roosevelt’s idea of creating the UN. It seems to us that he intended international organization with the “four policemen” (USA, USSR, UK and China - the prototype of the UN Security Council) to prevent the danger of the revival of a fascist state in Germany. We believe that Roosevelt, who actively welcomed Munich Agreements, subsequently thought about a lot as a far-sighted politician of American imperialism.

The war provided the United States with the opportunity not only to restore its industry to the level of 1929, but also to far exceed it due to the dynamic development of the war economy. " New course"Roosevelt was a course of forced reforms that strengthened state-monopoly capitalism and partly satisfied the interests of workers: in 1935, a law confirming the right to a collective agreement came into force, as well as a social security law that introduced unemployment benefits and increased, albeit slightly , tax on the richest and inheritance. According to the "new course" limits were set working week and a minimum wage per working day is guaranteed.

But the foundations of the capitalist social system remained unchanged. The New Deal protected them, and therefore a crisis in the system was inevitable: in the spring of 1938, the decline in industrial production reached alarming proportions. There were 10 million unemployed in the country. By the summer of 1939, the United States ranked 17th among the major capitalist countries in restoring pre-crisis levels of industrial output. The war became the salvation of American imperialism. The rapid growth of the high-tech military industry has brought the country to the leaders of the capitalist world.

In this situation, Roosevelt, as a realist politician and pragmatist, could not help but realize that Germany, Japan and England could become potential competitors for the United States. That is why he sought the complete defeat of Germany and Japan, which was simply impossible without an alliance with the USSR. So the great partnership between Roosevelt and Stalin was opportunistic in nature, which does not devalue its significance for humanity. As for Great Britain, its demotion in the table of ranks of world powers was becoming a matter of time.

American imperialism, having overtaken European imperialism (German, English and French above all) and Asian imperialism (Japanese), rushed at full speed to establish its hegemony in the bourgeois world. The conference in Tehran was evidence of this: Roosevelt's condescension towards Churchill was eye-opening. The United States began to pass off its imperial hegemony as its national interests, which it continues to do to this day. It was in Tehran that an application was made for a policy that at the end of the twentieth century would be called the policy of globalism. Roosevelt, as already mentioned, came up with the idea of creating a world government, it is not difficult to guess under whose auspices. Stalin listened to this proposal from the US President with icy indifference - the idea failed. The still hidden claims of American imperialism for world domination fully manifested themselves in Roosevelt’s version of the solution to the German question.

German question

In essence, the US President was offering the prospect of eliminating Germany as a country. His plan called for the division of Germany into five autonomous parts: (1) Prussia; (2) Hanover and northwestern Germany; (3) Saxony and Leipzig; (4) Hesse-Darmstadt; (5) Baden, Bavaria and Württemberg.

Stalin was for the division of Germany. We emphasize this, since in Soviet historiography the thesis was established that the Soviet Union, and, accordingly, Stalin, always stood for the unity of the German nation and country. This was so from the point of view of the historical perspective of its far from near future. In the specific historical situation of 1943, in view of the inevitable defeat of Germany, Stalin thought like Roosevelt: first of all, it was necessary that the idea of the Reich be erased from the German consciousness. “It is necessary,” he said in Tehran, “the very concept of the Reich should become powerless to ever again plunge the world into the abyss of war... And until the victorious allies secure for themselves the strategic positions necessary to prevent a relapse of German militarism, they will not be able to solve this problem "

Stalin knew the lessons of history very well. He remembered that according to the Treaty of Versailles, defeated Germany was guaranteed the unity of the country and nation. But, as the outstanding Soviet writer-historian V. Pikul noted, “for the Germans, imperial concepts stood above national ones” and “Hitler came to power, promising to resurrect the “Third Reich - with colonies and slaves.” The idea of the Reich, nurtured by Prussian militarism, linked the latter with the class interest of German imperialism (the bet on world domination). In the figurative expression of V. Pikul, it was at the end of the era of Bismarck and Moltke that “future Hitler’s marshals came out of the swaddling clothes - Rundstedt, Paulus, Halder, Keitel, Manstein, Guderian and others.”

Stalin did not forget the lessons of history. In Tehran, he advocated the division of Germany also for the reason that he looked at the future of the Soviet zone of its control through the prism of its possible socialist reconstruction. Like Roosevelt, Stalin saw the hidden position of the British prime minister on the German question: “he wanted a strong Germany in order to ensure a balance of power with the Soviet Union in Europe.” This is at a minimum, and at a maximum - to again use the well-functioning German war machine against the USSR.

Let us give S. Butler her due: we can say that on the German issue (and not only) she was on Stalin’s side. This is evidenced by the following provisions of her book. We read: “Stalin knew firsthand how cruel the attitude of German soldiers was towards all Slavs. The war that Hitler waged against the Soviet Union and Poland (Aryans against Slavic peoples) was strikingly different from the war he waged in Western Europe (Aryans against Aryans). Hitler considered the Slavs an inferior race. After the successful completion of the war, he planned to turn Russia and Poland into enslaved countries” (just remember the “Ost” plan - Yu.B.); “Stalin did not believe that the Slavs were a master race destined to rule the world. He believed that communism was the economic model of the future and that communism would eventually be adopted in the West because it was a more efficient form of government. However, the immediate priority now was to win the war and secure the borders of the Soviet Union, which meant securing control of Germany.

Stalin was so concerned about the future of Germany that after returning to Moscow he carefully edited the Russian portion of the conversations in Tehran to reflect what he had said during them and to make the necessary corrections himself. The final version of the Soviet document read: “Comrade Stalin stated that in order to weaken Germany, the Soviet government prefers to divide it.”

Brief conclusion

If we try to give the most general assessment of Susan Butler's book, then we can say about it: this is a book by an author for whom the desire for objectivity and honesty in the research of epochal historical events comes first. She is imbued with a spirit of admiration for the heroism of the Soviet people and a feeling of deep sympathy for their sacrifices during the Second World War. Against the backdrop of the rabid Russophobia emanating from the “civilized” West today, this is a brave book that challenges those who denigrate the contributions of the Red Army and deny the price the Soviet Union paid for Great Victory for all humanity.

S. Butler does not directly pose the question: why was the great partnership of two superpowers belonging to opposite social worlds possible? But it comes up after reading the book. In a condensed form, we think the following answer can be given to it: it, this partnership, became possible thanks to the presence of powerful military and scientific-industrial forces on each of the parties, which is the first thing. Secondly, in the conditions of the social and political system of their countries, each of the leaders fulfilled their historical mission, to one degree or another, reflecting the interests of the working people: Stalin, as a proletarian politician, - to the fullest, Roosevelt, as a progressive, but bourgeois politician, - partially, but significantly compared to those who ruled America before him. In other words, both of them had authority among the people: Stalin - indisputable, Roosevelt - quite high and strong (in Tehran, as already noted, he was the President of the United States, elected for a third term, which no one has ever achieved, not to mention his election to a fourth presidential term after Tehran). Thirdly, both Stalin and Roosevelt were great politicians, people of large-scale state thinking, high erudition in matters of history, politics and culture.

Did the great partnership between the USSR and the USA have a long and stable historical perspective? We are sure that no, it did not. The reason for this is the uncontrollable desire of American imperialism for world domination. This opinion is strengthened when reading Susan Butler's book. Roosevelt, had he not died so suddenly, could have extended the peaceful existence of the two superpowers for some period, but he was unable to make it irreversible. American imperialism could not deny itself the opportunity to extract maximum profits without the export of capital, the militarization of the economy, and a reactionary foreign policy.

And yet, could Roosevelt, in his fourth presidential term, have prevented, say, a “cold war” between the USA and the USSR? Most likely, he could and would have tried to do this. But he was unable to stop this war in the future. It is no coincidence that US political “hawks” imposed their representative, Truman, on him as vice president.

But let’s dwell on the main conclusions arising from the content of Susan Butler’s book. Stalin and Roosevelt at the conference in Tehran laid, in our opinion, the foundations of a bipolar world, a world without a third world war. It existed until December 1991, until the collapse of the USSR. This is the life of two generations - 50 years. This is, first of all, the historical merit of the two great politicians of the 20th century.

Yuri Belov

On November 28, 1943, the Tehran Conference began its work. This was the first face-to-face meeting of the leaders of the countries participating in the Anti-Hitler Coalition during the entire war. It was there that agreements were reached on the opening of a second front in Europe against Germany. This meeting traditionally fascinates great attention researchers not only because of their historical significance, but also because the Nazis allegedly intended to turn the tide of the war by assassinating three leaders at once. And only the actions of Soviet intelligence prevented this.

Over the past 74 years, the story has turned into a legend and taken on a life of its own. However, in reality, most likely, there was no attempt. This whole story with the foiled assassination attempt was initially a cunning disinformation on the part of Stalin, which was supposed to serve Soviet interests. With the help of this story, the leader of the USSR hoped to put additional pressure on the allies in the anti-Hitler coalition and gain an additional trump card in difficult negotiations on the issue of the second front.

Preparation

After the start of the war, the leaders of the countries that fought with Nazi Germany conducted quite lively diplomatic affairs. Conferences of representatives of the USA, USSR and Britain were repeatedly held in various cities. But each time these were either meetings at the level of heads of foreign affairs agencies, or in a truncated format. For example, in August 1942, British leader Churchill came to a conference in Moscow, but the Americans were represented by Averell Harriman, Roosevelt’s personal representative.

Averell Harriman - Roosevelt's personal representative. Collage © L!FE Photo: © W ikipedia.org

During the first two and a half years of the war, the leaders of the three leading powers never met in in full force. Meanwhile, after the Battle of Kursk, a final turning point occurred in the war. From that moment it became clear that a meeting of the three leaders was inevitable and would take place in the near future. Since it was necessary to discuss not only questions about Lend-Lease supplies or the opening of a second front, but also to outline some contours of the post-war world.

However, choosing a location for the meeting was much more difficult than agreeing on its holding. All countries were quite far from each other, and no matter what option they chose, at least one of the leaders would have found it completely inconvenient to get there. In addition, war was raging in Europe, so routes had to be drawn up with this in mind.

If the issue of holding the conference was agreed upon quickly enough, back in early September 1943, the choice of its venue dragged on for several months and was decided literally at the last moment. It would have been convenient to hold the conference in London, where at that time the governments in exile of a good half of European countries were based. However, the path there was unsafe for Roosevelt and Stalin. Churchill suggested Cairo, where it was located a large number of British soldiers, but Stalin found it inconvenient to get there.

Roosevelt proposed organizing a meeting in Alaska, which would be the best option from a security point of view. However, Stalin did not agree to this. Firstly, he was afraid to fly on an airplane, and secondly, the journey there would have taken a very long time and in the event of some unforeseen changes on the fronts, the Soviet leader would have been cut off from Headquarters for a long time.

The meeting could have been organized in Moscow, but this was not the best option from a diplomatic point of view. Then it turned out that Stalin looked down on his allies so much that he did not even want to leave Moscow to meet with them.

As a result, it was decided to hold the meeting on neutral territory so that no one would be offended. The choice fell on Iran. It was not far for Stalin to get there, and Churchill was not too far from overseas British possessions either. And for Roosevelt, whether Cairo or Tehran is approximately the same, since both would have to be reached by sea in any case.

Iran's main advantage was its security. Formally, it was a neutral country. But in fact, back in 1941, Soviet and British troops, during a joint operation, preemptively occupied the country in case the Germans tried to break through to the oil fields.

There were Soviet and British army units in Iran. Their intelligence services were also active. So from a security point of view, Iran was an ideal option among neutral countries. Because the country was an important transit point for the supply of goods under Lend-Lease to the USSR, and in connection with this, all German agents in the country were cleared out long ago and thoroughly by both the British and Soviet intelligence services.

Conference

On November 8, 1943, 20 days before the opening of the conference, Roosevelt agreed to the proposal to hold it in Tehran. Active preparations for the event have begun. Each of the coalition leaders got to the appointed place along their own route. Stalin left for Baku on a special, highly guarded armored train. In the capital of the Azerbaijan SSR, he boarded a plane piloted by the chief Soviet civil aviation pilot Viktor Grachev, who was carrying high-ranking officials.

The American president traveled to Cairo on the largest American battleship, the Iowa, accompanied by a military escort of ships. In Cairo, he met with Churchill, who was waiting for him, and they flew to Tehran together.

For three days the allies discussed the opening of a second front, deciding on the timing. The front was planned to open in May 1944, but later the dates were pushed back by several weeks. In addition, issues of the post-war world order were discussed. The contours of a new international body - the UN - were agreed upon. The post-war fate of Germany was also discussed.

Tehran, Iran, December 1943. Front row: Marshal Stalin, President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill on the portico of the Russian Embassy; back row: General Arnold of the Army, Chief of the United States Air Force; General Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff; Admiral Cunningham, Lord of the First Sea; Admiral William Leahy, Chief of Staff to President Roosevelt - during the Tehran Conference. Collage © L!FE Photo: © Wikipedia.org

Unprecedented security measures were taken during the conference. In addition to the fact that Soviet and British troops were already in the country, additional NKVD units were introduced into Tehran to protect particularly important facilities. In addition, the entire country was entangled in a dense Soviet-British intelligence network. Soviet stations were located in almost every more or less large locality in the zone of Soviet occupation. A roughly similar situation was observed in the British zone of occupation. The buildings where meetings of the leaders of the anti-Hitler coalition took place, as well as their routes of movement, were cordoned off with three or four rings of armed guards. In addition, air defense units were stationed in the city. In a word, Tehran could withstand a real assault by an entire army, although it had nowhere to come from in the desert.

Nevertheless, Stalin immediately stunned the arriving Churchill and Roosevelt with the news that the Soviet secret services had just prevented an assassination attempt on them, thwarting the insidious plans of the Nazis. As if Soviet intelligence managed to capture several dozen German saboteurs who were planning a terrorist attack, but some may have managed to escape, so he cordially invites his colleagues to stay at the Soviet embassy under reliable guard.

Churchill only smiled slyly, pretending to believe. Iran was literally flooded with British agents; moreover, for the last half century, the country was in the British sphere of influence and the British felt as at ease there as at home. Even that German agents, which existed in the country before the war, has been cleared out in several stages over the past two years due to the importance of Iran for Lend-Lease routes.

But Roosevelt was much less aware of the situation in Iran. American intelligence in Iran did not have the same scope as the British or Soviet, so he listened more carefully to Stalin’s words. And when the Soviet leader suggested, under the pretext of safety, that everyone should move to the Soviet embassy, Churchill flatly refused, saying that this was not necessary. But Roosevelt agreed and moved to live in the Soviet mission.

However, one should not underestimate the gullibility of the American president. This move was influenced by two other significant factors. Firstly, unlike the British embassy, which was located next to the Soviet one, a few meters away, the American one was located in another part of the city. And Roosevelt would have to travel alone through the entire city every day, which was inconvenient for the guards.

Secondly, and this is the most important thing, Stalin and Roosevelt had long been looking for an opportunity to get closer, but it never presented itself. Unlike the staunch anti-communist Churchill, Roosevelt was more favorably disposed towards Stalin. There was even some sympathy between the two leaders. For this reason, Stalin hoped that by eliminating the influence of the British leader on Roosevelt, the American could be made much more accommodating. By housing the American president in the Soviet embassy, the Soviet leader could be in charge, feeling at home, had additional opportunities to “process” Roosevelt, and in addition, the president’s conversations could be monitored by Soviet intelligence. Thus, Stalin killed three birds with one stone.

But the American president could not just take up residence in the Soviet embassy under the pretext that he had to travel far for meetings. Such a step would be greeted with hostility in the United States, where the country's leader would have to justify himself for a long time. That is why the cunning with the imaginary assassination attempt was needed. Thus, Stalin gave Roosevelt a legitimate opportunity to move to the Soviet embassy and not be booed for it. This whole story was not intended for Churchill (Stalin knew perfectly well that he would not believe it), but for Roosevelt, who took advantage of a convenient pretext and later explained to the Americans that he accepted the Soviet proposal, since the USSR intelligence services had information about a possible assassination attempt and this was necessary with security point of view.

The fact that this whole story was nothing more than a diplomatic ploy is evidenced by the fact that the Soviet side did not even bother with a more or less plausible legend of the assassination attempt. When the British (perhaps on the initiative of the cunning Churchill, who figured out the maneuver) asked whether it was possible to see the detained German saboteurs, they were told that this was in no way possible. Attempts to find out the details of the uncovered conspiracy through Molotov were also unsuccessful. The Soviet People's Commissar stated that he did not know any details of this case.

From left to right: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin sit together at a dinner in the Victorian drawing room of the British Legation in Tehran in Iran, celebrating Winston Churchill's 69th birthday on November 30, 1943. Collage © L!FE Photo: © Wikipedia.org

It is quite possible that on the eve of the meeting, the Soviet special services could actually arrest several suspicious local residents, as they say, just in case. But do not think that these were selected thugs-saboteurs, armed to the teeth, sent personally by Hitler.

The legend of the assassination attempt

The classic legend of the assassination attempt is full of inconsistencies, which is not surprising. It began to be developed many years after the end of the war through the efforts of Soviet publicists.

So, according to the classic version, in the spring-summer (the time of year differs in different sources) of 1943 Soviet intelligence officer Nikolai Kuznetsov, under the name of Paul Siebert, who served in the German administration in Rovno, got the overly talkative SS Sturmbannführer Hans Ulrich von Ortel drunk, who told him that he would soon participate in a responsible mission in Tehran, which would even surpass Skorzeny’s operation to rescue Mussolini.

Kuznetsov immediately reported this to the appropriate place. Meanwhile, in the summer of 1943, a group of German paratroopers-radio operators landed in Iran, who were supposed to prepare the base for the arrival of Skorzeny’s main sabotage group. However, Soviet intelligence was well aware of this and all the agents were soon captured. Having learned about this, the Germans were forced to cancel the operation at the last moment. Regarding the specific method of the assassination attempt, versions vary depending on the imagination of publicists. Everything is like in the best spy novels: infiltration under the guise of waiters and execution at dinner, a tunnel through a cemetery, a plane with explosives piloted by a suicide bomber, etc. stories from spy action films.

Nikolai Kuznetsov in German uniform, 1942. Photo: © Wikipedia.org

It is quite obvious that even with the slightest attention to detail, the version looks extremely dubious. Firstly, Kuznetsov, even if he wanted to, could not report on the operation planned by the Germans in the summer of 1943, since then even the leaders of the countries themselves did not know when this conference would take place. Only at the beginning of September was an agreement reached on the meeting and only on November 8 was the location chosen. However, in Lately this discrepancy was noticed and now they are writing about the autumn of 1943, although in classical sources the extraction of valuable information dates back to the spring and summer.

Secondly, Ortel could not boast to Kuznetsov that a more dramatic operation was planned to rescue Mussolini, since this operation took place only in September 1943, while most sources claim that Kuznetsov conveyed information about this no later than the summer of 1943. Thirdly, it is highly doubtful that the details are so secret operation could have been dedicated to some ordinary SS man, Ortel from Rivne. Fourthly, the same Skorzeny, who is considered the leader of this operation, claimed after the war that no SS Sturmbannführer Hans Ulrich von Ortel, who was supposedly part of his group, never existed (in various Soviet sources he is called either Paul Ortel or Oster in general).

In addition, the assertion that the first group of saboteurs was sent to Iran in the summer of 1943 to prepare an assassination attempt looks very doubtful. How could the Germans know where the meeting would take place, when even the participants themselves, who had not yet agreed on it, did not know this.

But even if we imagine that someone simply mixed up the dates and names, and the Germans were actually preparing this operation, how could they get to Iran? The pre-war agents were completely destroyed, which meant that people would have to be transferred from Germany. But how to do that? For landing operations, the Germans typically used DFS 230 and Go 242 gliders, which were towed by Ju 52 or He-111 bombers. However, these bombers had a very limited flight range and for such an operation the Germans needed to have field airfields in the Middle East.

For obvious reasons, the Germans did not have such airfields in Iran itself. For the same reason, they did not have them in the USSR, which bordered Iran. Only Iraq, Türkiye and Saudi Arabia. Türkiye adhered to neutrality and did not have German airfields. Iraq and Arabia were in the sphere of influence of the British. The only airfields in the Middle East that the Germans had (Syrian airfields were used under an agreement with Vichy France) were lost by them in the summer of 1941, when de Gaulle’s “Fighting France”, with the active participation of British troops, took control of Syria.

The only aircraft that could do this was the Ju 290 long-range maritime reconnaissance aircraft, capable of flying six thousand kilometers. However, the Germans had only a few such aircraft and almost all of them were used to search for sea convoys off the British coast. And for such a landing operation, taking into account the capacity of the aircraft, at least 5–10 such aircraft, which were piece goods, would be required (only about 50 of them were built during the entire war). According to Skorzeny’s memoirs, with great difficulty they managed to get one such plane to fly six agents to Iran in the summer of 1943. They were supposed to carry out sabotage on Lend-Lease routes in coordination with local rebel detachments. According to Skorzeny, the group was discovered almost immediately and made no progress.

Actually, it is this particular delivery that is very often confused with the imaginary delivery of saboteurs to Iran to assassinate the leaders of the anti-Hitler coalition. In reality, it has nothing to do with it; after this unsuccessful attempt, the Germans did not make similar landings again.

Finally, the Nazis simply did not have time to prepare it. The allies themselves only agreed on November 8 (20 days before its start) to hold a conference in Tehran. It must have taken German intelligence some time to obtain this information. Thus, the Germans would have had no more than 7–15 days to prepare a complex operation in the most difficult conditions. And this is in the context of completely destroyed local agents and total dominance in Iran of the Soviet-British intelligence services and army and unprecedented security measures. Obviously, in such conditions, preparing such a complex operation was simply impossible.

By the way, Skorzeny himself always denied that such an operation was being developed. He did not deny that he met with Hitler and the heads of the German intelligence services after information about the Tehran meeting became known to the Nazis. However, after Hitler asked if something could be done, the available scenarios were briefly described to him, and they were so unfavorable that it immediately became clear that this mission was impossible - and the issue was closed without much discussion. It is for this reason that both Skorzeny himself and his immediate superior Schellenberg ignored it in their memoirs, and it was also not possible to find any traces of the planning of this operation in the captured German archives.

Yuri Andropov and Nikolai Shchelokov. Collage © L!FE Photo: © RIA Novosti, Wi kipedia.org

In reality, the whole story of the assassination attempt was a cunning diplomatic ploy by Stalin, aimed primarily at the American leader. If Roosevelt had believed in it, he would have been very grateful to his Soviet colleague for his concern and felt a sense of duty towards him, becoming more accommodating. But even if he didn’t believe it, this story gave Roosevelt a “legal” opportunity to move to the Soviet embassy, which was beneficial to both. Ultimately, the ruse played into the hands of the Soviet side. At the Tehran Conference, Stalin and Roosevelt actually presented a united front against Churchill. The American president generally agreed with Stalin and supported his initiatives, while Churchill was left alone.

In fact, during the conference, Roosevelt went against Churchill, who insisted on an attack on the Balkans through Italy, and spoke in favor of opening a second front in northern France. Roosevelt supported Stalin on the issue of dividing defeated Germany, as well as on the issue of organizing the UN. De facto, at the Tehran Conference, an internal mini-coalition of Stalin - Roosevelt arose within the anti-Hitler coalition, since at that time there were no contradictions of interests between the USA and the USSR, whereas there had always been such conflicts between Britain and the USSR.

Evgeniy Antonyuk

In January 1943, at a meeting in Casablanca (Morocco), US President F.D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister W. Churchill declared that they would wage the war until unconditional surrender Nazi Germany. However, towards the end of the war, some politicians in the West began to cautiously speak out in the spirit that the demand for unconditional surrender would spur German resistance and prolong the war. In addition, it would be nice, they continued, not to bring the matter to the complete defeat of Germany, but to partially preserve the military power of this country as a barrier against the growing Soviet Union. Moreover, if we assume that Soviet troops enter Germany, the USSR will firmly establish itself in Central Europe.

For similar reasons, Stalin also doubted the practicality of the demand for unconditional surrender and believed that a weakened but not completely defeated Germany, no longer capable of threatening an aggressive war, was less dangerous for the USSR than the victorious Anglo-Saxon countries that had established themselves in the center of Europe. After all, in 1922-1933 and 1939-1941. The USSR and Germany were on friendly terms.

At the Tehran Conference of the Heads of Government of the Three Allied Powers (November 28 - December 1, 1943), Stalin, in a private conversation at a dinner with Roosevelt, proposed making specific demands for Germany to surrender, as was the case at the end of the First World War. It should have been announced how many weapons Germany should give up and what territories it should give up. The slogan of unconditional surrender, according to Stalin, forces the Germans to unite and fight until they become fierce and helps Hitler stay in power. Roosevelt remained silent and did not answer. On Stalin’s part, obviously, this was a “shooting” in order to find out the reaction of the allies. Later he did not return to this topic. At the Tehran Conference, the USSR officially joined the declaration demanding the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany.

There, at the Tehran Conference, the issue of the post-war territorial structure of Germany was discussed. Roosevelt proposed dividing Germany into five states. The US President, in addition, believed that the Kiel Canal, the Ruhr Basin and the Saarland should be internationalized, and Hamburg should be made a “free city”. Churchill believed it was necessary to separate the southern lands (Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden) from Germany and include them together with Austria, and probably also Hungary, in the “Danube Confederation”. The British prime minister proposed dividing the rest of Germany (minus the territories going to neighboring states) into two states. Stalin did not express his attitude towards the plans for the division of Germany, but achieved promises that East Prussia will be torn away from Germany and divided between the USSR and Poland. Poland, in addition, will receive significant increases at the expense of Germany in the west.

Plans for the post-war division of Germany into several independent states also captured Soviet diplomacy for some time. In January 1944 former ambassador USSR in London, Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs I.M. Maisky wrote a note in which he substantiated the need for the dismemberment of Germany. At the end of 1944, former People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs M.M. Litvinov also formulated a project in which he argued that Germany should be divided into a minimum of three and a maximum of seven states. These plans were studied by Stalin and the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs V.M. Molotov before the Yalta Conference of Great Powers in February 1945.

Stalin, however, was in no hurry to take advantage of these recommendations, but intended to first find out the position of England and the United States. Back in September 1944, at a meeting in Quebec, Roosevelt and Churchill discussed the plan of the American Treasury Secretary Morgenthau. According to it, it was supposed to deprive Germany of heavy industry in general and divide what was left of it (minus the lands going to Poland and France) into three states: northern, western and southern. This division of Germany into three was first envisaged back in 1942 in the plan of US Deputy Secretary of State (Minister of Foreign Affairs) S. Wells.

However, by that time the mood of influential circles in the West had changed significantly. As already mentioned, the Soviet Union was perceived in the post-war perspective as a greater threat than a united, defeated Germany. Therefore, Roosevelt and Churchill were in no hurry to discuss the post-war government structure Germany, except in the zones of its occupation by the great powers. Therefore, Stalin also did not make such proposals. The projects of Maisky and Litvinov were shelved. Obviously, Stalin did not sympathize with them in advance. For the same reason as his Western partners, he did not want Germany to be excessively weakened and fragmented.

On May 9, 1945, speaking on the radio on the occasion of Victory Day, Stalin, quite unexpectedly for the Western allies, announced that the USSR did not aim to dismember Germany or deprive it of statehood. This was a certain position the day before last meeting leaders of the three victorious powers, held from July 17 to August 2, 1945 in Potsdam. When at the Potsdam Conference the Allies raised the issue of internationalization of the Ruhr region, Stalin noted that his views on this issue “have now changed somewhat.” "Germany remains a single state“,” the Soviet leader firmly emphasized. This topic was not raised again.

Although summits similar to the Big Three conferences were no longer held, several post-war meetings of the foreign ministers of the victorious powers agreed that the future Germany should become a single democratic federal state. The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany, proclaimed in the western zones of occupation on May 23, 1949, was in accordance with these plans. The problem was that both the West and the USSR wanted to develop Germany in their own way. Ultimately, each side is " cold war"received the Germany she was striving for - united and under her control, but not all of it, but only part of it.

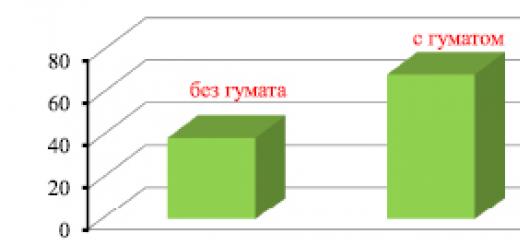

From the first days of the war, President Roosevelt linked American aid to the supply of weapons and supplies to the Soviet Union with an end to the persecution of the Church. The day after Hitler invaded the USSR in June 1941, he advised Stalin that American aid and religious freedom went hand in hand. Throughout 1942, he reminded Stalin that there would be no great help from the United States until the Russian Orthodox Church was restored in the USSR. Stalin surrendered to Roosevelt two months before the Tehran Conference.

How Roosevelt’s demand for an end to the persecution of religion and the Church in the USSR went is described in the book by the American historian Susan Butler “Stalin and Roosevelt: the Great Partnership” (Eksmo, 2017). For informational purposes, we present an excerpt from this book:

"Stalin took the most significant steps that received approval from Franklin D. Roosevelt in the religious sphere. Two months before the Tehran Conference, Stalin officially abandoned his anti-religious policy. He knew that the negative attitude of the Soviet Union towards religion was a constant problem for Roosevelt The President knew that this provided ample opportunity for enemies of the Soviet Union in the United States (especially the Catholic Church) to criticize the Soviet system, but it also offended him personally.Only those closest to Roosevelt were aware of his deep religiosity.

Rexford Tugwell, a close friend of Roosevelt and a member of the Columbia University Brain Trust, which developed the first recommendations for Roosevelt's presidential policies, recalled that when Roosevelt wanted to organize, create, or establish something, he asked everyone his colleagues to join him in his prayer as he sought divine blessing on what they were about to do. Presidential speechwriter Robert Sherwood believed that " his religious faith was the most powerful and most mysterious force that lived within him".

Roosevelt took every opportunity to emphasize the need for religious freedom in the Soviet Union. The day after Hitler invaded the USSR in June 1941, he advised Stalin that American aid and religious freedom went hand in hand: " Freedom to worship God as conscience dictates is the great and fundamental right of all peoples. For the United States, any principles and doctrines of the communist dictatorship are as intolerant and alien as the principles and doctrines of the Nazi dictatorship. No imposed domination can or will receive any support, any influence in the way of life or in the system of government from the American people".

In the autumn of 1941, when German army approached Moscow and Averell Harriman, along with Lord Beaverbrook, a newspaper magnate and British Minister of Supply, was about to fly to Moscow to coordinate a program of possible American-British supplies to the Soviet Union, Roosevelt took this opportunity to again speak out in defense of religious freedom in the USSR. Stalin was in hopeless situation, and Roosevelt knew that a more favorable moment might not present itself to him. " I believe that this is a real opportunity for Russia to recognize freedom of religion as a result of the conflict that has arisen.", Roosevelt wrote in early September 1941.

He took three steps. First, the President invited Konstantin Umansky, the Soviet ambassador in Washington, to the White House to tell him that it would be extremely difficult to pass Congressional aid to Russia, which he knew it desperately needed, due to Congress's intense hostility toward the USSR. . Then he suggested: " If in the next few days, without waiting for Harriman's arrival in Moscow, the Soviet leadership authorizes coverage in the media mass media issues relating to freedom of religion in the country, this could have a very positive educational effect before the Lend-Lease bill comes before Congress". Umansky agreed to provide assistance in this matter.

On September 30, 1941, Roosevelt held a press conference, during which he instructed journalists to familiarize themselves with Article 124 of the Soviet Constitution, which talked about guarantees of freedom of conscience and freedom of religion, and to publish this information. (After this information was duly released to the press, Roosevelt's nemesis, Hamilton Fish, a Republican congressman from Roosevelt's Hyde Park district, sarcastically suggested that the President invite Stalin to the White House "so he could perform the baptism in the swimming pool White House")

Roosevelt then instructed Harriman, already ready to leave for Moscow, to raise the issue of religious freedom with Stalin. As Harriman recalled, " the President wanted me to convince Stalin of the importance of loosening restrictions on religion. Roosevelt expressed concern about possible opposition from various religious groups. In addition, he sincerely wanted to use our cooperation during the war to influence the hostility of the Soviet regime towards religion"Harriman raised this issue in a conversation with Stalin in such a way that it became clear to him: the political situation and the negative public opinion of the United States regarding Russia will change for the better if" The Soviets will show their readiness to ensure freedom of religion not only in words, but also in deeds"As Harriman said when he explained it, Stalin" nodded his head, which meant, as I understood, his readiness to do something".

Harriman also raised this topic in a conversation with Molotov, who made it known that he did not believe in Roosevelt's sincerity. " Molotov frankly told me of the great respect he and others had for the President. At some point he asked me if the president, who was so smart, intelligent person Is it as religious as it seems, or is it being done for political purposes?"," Harriman recalled.

The reaction of the Soviet side was quite understandable. Umansky may have reported to Moscow that Roosevelt never attended Sunday services at the National Cathedral, an Episcopal church that presidents and the top Episcopalians in Washington traditionally attended during services (though he sometimes attended St. John's on Lafayette Square). Apparently Umansky did not know that Roosevelt avoided the National Council because he hated the presiding bishop in Washington, James Freeman.

Harriman managed to achieve the minimum. Solomon Lozovsky, Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs, waited 24 hours after Harriman's departure from Moscow, called a press conference and read out the following statement: " The public of the Soviet Union learned with great interest about President Roosevelt's statement at a press conference regarding religious freedom in the USSR. All citizens are granted freedom of religion and freedom of anti-religious propaganda.". Along with this, he noted that the Soviet state "does not interfere in matters of religion," religion is " personal matter"Lozovsky concluded his statement with a warning to the leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church, many of whom were still in prison: " Freedom of any religion presupposes that a religion, church or any community will not be used to overthrow the existing and recognized government in the country".

The only newspaper in Russia that covered the event was Moscow News, an English-language publication read only by Americans. The newspapers Pravda and Izvestia ignored Lozovsky's comments. Roosevelt was not pleased because he expected more. As Harriman recalled, " he let me know that this was not enough and reprimanded me. He criticized my inability to do better".

A few weeks later, having reviewed the State Department's latest draft of the Declaration of the United Nations, which all countries at war were required to sign on January 1, 1942, Roosevelt asked Hull to include a clause on religious freedom in the document: " I believe that Litvinov will be forced to agree with this". When Soviet ambassador Litvinov, who had just replaced Umansky, objected to the inclusion of a phrase concerning religion in the text; Roosevelt played with this expression, changing “freedom of religion” to “religious freedom.” This correction, essentially insignificant and unprincipled, allowed Litvinov, without distorting the truth, to report to Moscow that he was able to force Roosevelt to change the document and thereby satisfy Stalin.

In November 1942, the first changes appeared in the anti-religious position of the Soviet government: Metropolitan Nikolai of Kiev [and Galicia], one of the three metropolitans who led the Russian Orthodox Church, became a member of the Extraordinary State Commission for the Determination and Investigation of Atrocities Nazi invaders. Now, two months before the Tehran Conference, Roosevelt had achieved important results and strengthened his position. Stalin, who took part in the closing and/or destruction of many churches and monasteries in Russia, began to view religion not through the narrow prism of the doctrine of communism, but from the position of Roosevelt.

On September 4, 1943, in the afternoon, Stalin summoned G. Karpov, Chairman of the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church under the Council of Ministers of the USSR, Georgy Malenkov and Lavrenty Beria to his “near dacha” in Kuntsevo. Stalin announced that he had decided to immediately restore the patriarchate, a system of church government headed by a patriarch that had been abolished in 1925, and to open churches and seminaries throughout the Soviet Union. Later that evening, Metropolitans Sergius, Nicholas and Alexy were summoned to the Kremlin, and Stalin informed them of the fateful decisions that had been made.

P.S. Thus, the restoration of the Patriarchate and at least partial legalization of the Orthodox Church in the Soviet Union is due solely to the persistence of Franklin D. Roosevelt. How “Comrade Stalin” really treated the Russian church is perfectly shown by this picture:

Joseph Stalin visited the United States for the first time.

At the War Memorial in Bedford, Virginia, he met with his World War II allies - Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman and Winston Churchill.

The meeting was also attended by British Deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee, leader of Fighting France Charles de Gaulle and Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek. Of course, all these leaders are long dead, and we're talking about about their busts.

However, such fierce debates have flared up around this initiative, as if we were talking not about the past, but about the most current events.

Many were outraged by the proposal to erect a monument to the Soviet leader in the heart of America. Ukrainian nationalists, neoconservatives from the Heritage Foundation, and the New York Daily News, owned by Mort Zuckerman, expressed their outrage.

The director of the memorial complex, William McIntosh, responded that the installation of the bust was simply recognition of the role that Stalin played in World War II.

There is no point in getting involved in this eternal debate - Stalin is a hero or a villain. Let's instead turn to more entertaining topics.

Let's talk, for example, about how Americans like to remember only one side of events and completely forget about the other.

For example, did the Americans use the defoliant Agent Orange in Vietnam to deprive the Viet Cong of the ability to hide in the forests?

Certainly! That's what defoliants are used for! But due to the use of this drug, more than 500 thousand children in this region were born with pathologies. The US government maintains that causation has not been established in this case, and many Americans agree.

Did the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the orders of Harry Truman help end the war faster and avoid unnecessary casualties? May be. And even probably. But what about the fact that the dead were civilians?

Now let's return to Stalin.

The most interesting thing about the American perception of Stalin is the fact that the opinion of the people who knew him best is not taken into account. For example, the opinion of Franklin Roosevelt.

Franklin Roosevelt regularly ranks among the top three most popular US presidents, along with George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

They love him for his wise policies, they love him because he helped the country overcome the most difficult crises in its history. Therefore, his opinion must be taken into account, isn’t it?

But it was not there.

These same Americans do not listen to the opinions of their best president in the 20th century regarding the man who has unexpectedly become his ally.

Roosevelt and Stalin were leaders of their countries for so long that they got to know each other quite well - although their first personal meeting did not take place until 1943.

Roosevelt's first bold move was to establish diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in November 1933, despite loud protests from Congress.

In 1936, Roosevelt sent ambassador to Soviet Russia your close friend. Joseph Davis and “Mission to Moscow” - a book he wrote upon returning to his homeland. One of the most controversial politicians centuries and one of the most discussed books of its time. The essence of the book is that Stalin's repressions were directed against people who planned to remove Stalin. In other words, these were not innocent victims, but a fifth column. Numerous sources claim that Roosevelt read the book and that he liked it—so much so that he personally supported the idea of making it into a film.

Of course, Roosevelt was not naive. “There is a dictatorship in the Soviet Union that is not inferior in severity to other existing dictatorships,” he declared in 1940.

However, at the same time, Roosevelt was so confident in Stalin that even when the USSR was on the brink of an abyss, Roosevelt continued to firmly believe in his strength.

Six weeks after the German attack on Russia, Roosevelt sent his closest adviser, Harry Hopkins, to Moscow, instructing him to convey to the Soviet leadership that Roosevelt was confident in Stalin's ability to defeat Hitler, and that the United States would provide every possible assistance to the USSR in this war.

And this despite the fact that both in the State Department and in the military department everyone was sure: the Stalinist USSR was a colossus with feet of clay that would crumble under the onslaught of Hitler’s troops.

“Dear sir Stalin! This letter will be given to you by my friend Averell Harriman, whom I asked to head our delegation in Moscow.” Thus began the message that the Soviet leader received in the fall of 1941, when his soldiers were fighting heavy battles near the very walls of the capital.

Roosevelt was one of those thanks to whom the Soviet Union began to receive vital aid under Lend-Lease. The Red Army received tens of thousands of American trucks, planes and other equipment that were so necessary in the mortal battle with Hitler.

When People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov, who was the second most important man in the Soviet leadership and perceived as Stalin's future successor, was about to make his first visit to Washington in May 1942, Roosevelt insisted in a letter to Stalin: “When Molotov arrives in Washington, he may stay with us in the White House, or, if you like, we can prepare a separate house for him nearby.”

Stalin reciprocated Roosevelt's feelings. He dissolved the Comintern, an organization whose main goal was to spread the communist revolution to the rest of the world. This event occurred on the very day that Joseph Davis arrived in Moscow with a message from Roosevelt.

In February 1945, an ailing Roosevelt flew to Yalta to pay respects to the country that had defeated the fascist armies, and, at the same time, to discuss the future world order.

In Yalta, Roosevelt obtained from Stalin consent for the USSR to enter the war against Japan. While in Europe they were fighting, there was a neutrality pact between the Soviet Union and Japan, which allowed the Soviet Union to concentrate its resources on the fight against Hitler, and also made it possible to carry out Lend-Lease supplies through the Far East.

Stalin agreed to send his battle-hardened troops against Japan. Roosevelt believed that the participation of the Soviet Union in the war was Pacific Ocean will play an important role as it will cement the alliance of the four great powers.

Roosevelt's death shocked Stalin. “President Roosevelt has died, but his work must be continued. We will support President Truman with all our strength,” Stalin told Averell Harriman, who brought the sad news to Moscow.

Why is Roosevelt adored today, but Stalin hated?

We are left with this quote from Ambassador Joseph Davis: “No government leader in history has faced such misperceptions and distortions as the men who led the Soviet state during those harsh years.”

But Joseph Vissarionovich himself understood his position better than anyone. One day he said: “My name will be blasphemed and reviled. I will be accused of the most terrible crimes.”