Chronicle lists

The Laurentian Chronicle also influenced later chronicles - the Trinity Chronicle, the Novgorod-Sophia Code, etc.

News chronology

According to the calculations of N. G. Berezhkov, the Laurentian Chronicle for 1110-1304 contains 101 March years, 60 ultra-March, 4 years below March, 5 empty, 26 have not survived.

Groups 6619-6622 (1110-1113), 6626-6627 (1117-1118), 6642-6646 (1133-1137) are ultramartian. 6623-6678 (1115-1170) March in general. 6679-6714 (1170-1205) generally Ultramartian. But 6686 (1178), 6688 (1180) March.

The third group of years: from repeated 6714 to 6771 (1206-1263) March, but among them 6717 (1208), 6725-6726 (1216-1217), 6740 (1231) - ultra-March. Readable after the gap 6792-6793 (1284-1285) March, 6802-6813 (1293-1304) Ultra March.

Editions

- PSRL. T.1. 1846.

- Chronicle according to the Laurentian list. / Publication of the Archaeographic Commission. St. Petersburg, 1872. 2nd ed. St. Petersburg, 1897.

- PSRL. T.1. 2nd ed. / Ed. E. F. Karsky. Issue 1-3. L., 1926-1928. (reissues: M., 1961; M., 1997, with a new preface by B. M. Kloss; M., 2001).

- Laurentian Chronicle. (Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles. Volume One). Leningrad, 1926-1928

- Laurentian Chronicle (ukr.)

Key Research

- Berezhkov N. G. Chronology of Russian annals. M.: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1963.

Notes

see also

Links

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010 .

- Sandhurst

- Klimova, Ekaterina Alexandrovna

See what the "Laurentian Chronicle" is in other dictionaries:

LAVRENTIAN CHRONICLE- written by the monk Lavrenty and other scribes in 1377. Based on the Vladimir code of 1305. It begins with the Tale of Bygone Years (the oldest list) ... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

LAVRENTIAN CHRONICLE- LAVRENTIEVSKAYA CHRONICLE, written by the monk Lavrenty and other scribes in 1377. It begins with the Tale of Vsemenngh Years (the oldest list), includes the Vladimir code of 1305. Source: Encyclopedia Fatherland ... Russian History

LAVRENTIAN CHRONICLE- a parchment manuscript containing a copy of the chronicle of 1305, made in 1377 by a group of scribes under the hands of. Monk Lawrence on the instructions of the Suzdal Nizhny Novgorod Prince. Dmitry Konstantinovich from the list of early. 14th c. The text of the code begins with the Tale ... ... Soviet historical encyclopedia

Laurentian Chronicle- a parchment manuscript containing a copy of the annalistic code of 1305, made in 1377 by a group of scribes under the guidance of the monk Lavrenty on the instructions of the Suzdal Nizhny Novgorod prince Dmitry Konstantinovich from the list of the beginning of the 14th century. Text… … Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Laurentian Chronicle- written by the monk Lavrentiy and other scribes in 1377. Based on the Vladimir Code of 1305. It begins with The Tale of Bygone Years (the oldest copy). * * * LAVRENTIEVSKAYA CHRONICLE LAVRENTIEVSKAYA CHRONICLE, manuscript on parchment with a copy of the chronicle ... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

Laurentian Chronicle- Lavr entiev Chronicle ... Russian spelling dictionary

Annals of Lavrentievskaya- - chronicle of the XIV century, preserved in the only parchment copy (GPB, F.p.IV.2), rewritten in 1377 by the monk Lavrenty by order of the Grand Duke of Suzdal Nizhny Novgorod Dmitry Konstantinovich. The text of L. brought to 6813 (1305) in six ... ... Dictionary of scribes and bookishness of Ancient Russia

chronicle- This term has other meanings, see Chronicle (meanings). The Laurentian Chronicle Chronicle (or chronicler) is a historical genre of ancient Russian literature ... Wikipedia

CHRONICLE- In Russia * XI-XVII centuries. a type of historical narrative literature, which is a record of what happened on a yearly basis (weather records). The word chronicle is derived from the noun leto* meaning ‘year’. Chronicles are... ... Linguistic Dictionary

chronicle- - vault historical notes in the order of years and days of the month. The Russian Chronicle, begun by an unknown Kiev Cave monk (maybe Nestor), was continued by various people. These continuations are named or at the place mentioned in the annals ... ... Complete Orthodox Theological Encyclopedic Dictionary

Books

- Complete collection of Russian chronicles. T. 1. Laurentian Chronicle, A.F. Bychkov. First volume Complete collection Russian chronicles, published in 1846, has long disappeared from scientific use. The Archaeographic Commission tried twice to fill this gap, releasing the second and ... Buy for 1691 UAH (Ukraine only)

- Complete collection of Russian chronicles. Campaign and travel notes kept during the Polish campaign in 1831. 1832. T. 01. Chronicle according to the Laurentian list (Laurentian Chronicle). 2nd ed., Politkovsky V.G. The book is a reprint edition of 1872. Although serious work has been done to restore the original quality of the edition, some pages may…

On June 20, 2012, employees of the library system of Pskov (5 people) as part of a cultural delegation from the Pskov region visited the Presidential Library. B.N. Yeltsin in St. Petersburg (Senate Square, 3). The reason for the visit to the library was the annual Russian history and celebrating the 1150th anniversary of Russian statehood at the historical and educational conference “Laurentian Chronicle. Historical memory and continuity of generations.

You can get acquainted with the conference program.

During the conference, reports were made on the 1150th anniversary of statehood, the significance of the Laurentian Chronicle for the history of Russia and the formation of our historical memory, topical issues of preserving the historical and cultural heritage of our country as a whole were discussed.

The conference participants were leading specialists from the State Hermitage, the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow State University and St. Petersburg State University, heads and specialists of Russian national libraries, representatives of state power And public organizations, scientists and artists.

The central event of the conference was the presentation of the electronic version of the Laurentian Chronicle. Demonstrated on the plasma panel documentary how the manuscript was digitized.

As Deputy Director General for Information Resources of the Presidential Library E. D. Zhabko noted, the electronic version of the Laurentian Chronicle has taken a worthy place in the collection “At the Origins of Russian Statehood”, prepared for the 1150th anniversary of the birth of Russian statehood. She stressed that in the future this document may be included in the complete electronic collection of original Russian chronicles, which will be created by the Presidential Library together with partners.

The result of the meetings that lasted throughout the day was the conclusion about the unanimous understanding of the importance of creating (more precisely, recreating in electronic form) not just a historical document, but a document that contains the moral foundations of the ancestors, without which the existence and further promising development of Russian society is impossible.

We express our deep gratitude to the State Committee for Culture of the Pskov Region for the opportunity for the staff of the Central Library Library to visit the Presidential Library in St. Petersburg and participate in the historical and educational conference.

The rest of the photos, which give a more complete picture of the perfect trip to the Presidential Library, can be viewed in the album of our group in contact: http://vk.com/album-12518403_158881017.

Laurentian Chronicle. Information sheet

The Laurentian Chronicle, kept in the funds of the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg, is one of the most valuable and most famous monuments of the cultural and historical heritage of Russia. This handwritten book, created by the monk Lavrentiy in 1377, is the oldest dated Russian chronicle.

It contains the oldest list of The Tale of Bygone Years, the earliest ancient Russian chronicle, dedicated to the first centuries of the history of Russia and which became the basis of the historiographic concept of the emergence of Russian statehood. It is here that the ancient history of the Slavs is set forth and the story placed under the year 862 is read about the calling of the Varangians and about the arrival of Rurik in Russia in 862. This year is considered to be the year of the birth of Russian statehood.

The Laurentian Chronicle got its name from the name of the scribe - the monk Lavrenty, who did the main part of the work of copying the text. On the last sheets of the manuscript, Lavrenty left a note in which he said that the chronicle was created in 1377 with the blessing of the Bishop of Suzdal, Nizhny Novgorod and Gorodetsky Dionysius for the Nizhny Novgorod prince Dmitry Konstantinovich, and that it was rewritten "from an old chronicler."

The manuscript contains 173 parchment leaves. Parchment - animal skin dressed in a special way - served as the main writing material in Russia until the beginning of the 15th century, when parchment replaced paper. The material of the letter itself testifies to the venerable antiquity of the monument. Only three parchment Russian chronicles have survived to modern times. In addition to the Lavrentievskaya, the only one accurately dated, is the Synodal list of the Novgorod First Chronicle, which has significant text loss, and the Trinity Chronicle, which was burned in Moscow in 1812, stored in the State Historical Museum in Moscow.

The story of historical events in the Laurentian Chronicle brought to 1305, reflecting in its various parts the South Russian, Vladimir, Rostov and Tver chronicles. The monument is the main source on the history of North-Eastern Russia. The Laurentian Chronicle contains unique works of ancient Russian literature. Only in the Laurentian Chronicle is read (under the year 1096) the famous Instruction of Vladimir Monomakh, which has come down only in this single list.

During its long life, the Laurentian Chronicle has repeatedly changed owners. The book was kept in the Annunciation Monastery in Nizhny Novgorod, then it belonged to the Nativity Monastery in Vladimir. In the XVIII century. the manuscript ended up in the library of the St. Sophia Cathedral in Veliky Novgorod, from where in 1791, among other manuscripts, it was sent to Moscow and ended up with the chief prosecutor of the Synod, Count Alexei Ivanovich Musin-Pushkin (1744-1817). Since that time, the Laurentian Chronicle has been introduced into scientific circulation and soon becomes one of the main sources of all Russian historiography. N. M. Karamzin actively used the monument in his work on the History of the Russian State. It is the Laurentian Chronicle that opens the publication of the Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles (the first edition of the First Volume of the series was published in 1846). D.S. Likhachev chose the Laurentian Chronicle as the main source for the preparation of the academic edition of The Tale of Bygone Years (in the Literary Monuments series, M.-L., 1950).

The fate of the Laurentian Chronicle is truly unique. In 1811 A.I. Musin-Pushkin presented the most valuable manuscript as a gift to Emperor Alexander I, and this gift saved the monument from destruction in the Moscow fire of 1812. Alexander I transferred the Laurentian Chronicle to the Imperial Public Library (now the Russian National Library) for eternal storage on August 27, 1811. Since then, the Laurentian Chronicle has been in the Department of Manuscripts of the library in the mode of storage of especially valuable monuments.

Despite everything, the Laurentian Chronicle did not burn down and has come down to us, and this is also its uniqueness. The monument continues to live, influencing the modern life of society and each of us.

In 2012, in the year of the celebration of the 1150th anniversary of the birth of Russian statehood, on the initiative of the Center of National Glory and the National Library of Russia, digital copy Laurentian Chronicle and a project to present the monument on the Internet. After all, it is very important to “touch”, see the original source, the manuscript itself – and now everyone can do it. The accessibility of the Laurentian Chronicle was provided by modern technologies to every citizen of Russia.

On June 20, 2012, a new and really worthy Internet resource was opened, allowing everyone to familiarize themselves with and study the most valuable manuscript, which has preserved on its sheets a centuries-old historical memory people.

The digital version of the Laurentian Chronicle is available on the portals of two libraries.

Access mode to the Laurentian Chronicle of 1377:

Russian National Library (RNL) - http://expositions.nlr.ru/LaurentianCodex

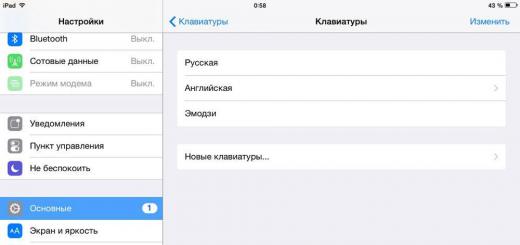

It is necessary to press the VIEW option at the bottom, install the Silverlight.exe viewer, return to the browser page and directly read the Laurentian Chronicle. The necessary set of options allows you to study the document as comfortably and usefully as possible.

The Laurentian Chronicle, a parchment manuscript containing a copy of the annalistic code of 1305, made in 1377 by a group of scribes under the guidance of the monk Lavrenty on the instructions of the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod prince Dmitry Konstantinovich from the list of the beginning of 14 in the Tale of Bygone Years and brought to 1305. The manuscript lacks news for 898 -922, 1263-1283, 1288-94. Code 1305 was a grand princely Vladimir code compiled at a time when Prince Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tver was the grand prince of Vladimir. It was based on the code of 1281, supplemented (since 1282) with the Tver chronicle news. Lawrence's manuscript was written in the Annunciation Monastery in Nizhny Novgorod or in the Vladimir Nativity Monastery. In 1792, it was acquired by A. I. Musin-Pushkin and subsequently presented to Alexander I, who gave the manuscript to the Public Library (now named after M. E. Saltykov-Shchedrin), where it is kept. The complete edition was carried out in 1846 ("The Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles", vol. 1).

The name of the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod prince Dmitry Konstantinovich is associated with an annalistic code compiled for him in 1377 on behalf of Bishop Dionysius by Mnich Lavrenty and which is the oldest of all surviving and indisputably dated lists of the Russian chronicle.

Obtained by the research of acad. A. A. Shakhmatova and M. D. Priselkov’s indisputable conclusions boil down to the recognition of the monument rewritten by Lawrence as the Grand Duke Chronicler of 1305, identical with the protographer of the Trinity Chronicle, between the Laurentian copy of which and what Lawrence wrote off (i.e., this very code of 1305 d.), there were no intermediate stages of chronicle writing. Consequently, everything in the list of Lawrence that, for whatever reasons, it would be impossible to elevate to the code of 1305, must be attributed without hesitation to him. The work of Mnikh Lavrenty on his chronicle source is clearly characterized by the analysis of the story about the Tatar invasion of 1237.

The story of the Laurentian Chronicle under 1237-1239, starting with a description of the Ryazan events, touching on Kolomna and Moscow, then vividly and in detail draws the siege and capture of Vladimir, mentioning in passing the capture of Suzdal; then leads us to the Sit, where Yury Vsevolodovich and Vasilko of Rostov camped, and where they bring Yury the news of the death of Vladimir, which he mourns; then briefly talks about the victory of the Tatars and the murder of Yuri; with details of Rostov origin, the death of Vasilko is depicted further; it talks about the burial of Yuri, and everything ends with his praise.

The older version of the story about these events was read in the Trinity Chronicle, the text of which is restored according to the Resurrection. This older version was also contained in the chronicle source, which Lavrenty reworked. The whole story as a whole, as it looked in the Trinity Chronicle, is drawn in the following form.

More detailed than in the Laurentian Chronicle, the retelling of the Ryazan events and the events in Kolomna connected with them (and not with Yuri of Vladimir) was replaced, as in the Laurentian Chronicle, with a description of the siege and capture of Vladimir with minor but significant differences from it; after a general indication with the Lavrentievskaya of the outcome of 6745, the story directly went on to the episode with Dorozh, the ambassador of Prince Yuri, sent to reconnoiter the whereabouts of the Tatars, which was absent in the Laurentian Chronicle, to the picture of the battle on the City, sustained in the tone of military stories, with a brief mention of the murder of Yuri, and with a detailed depiction of Vasilko's death; the ecclesiastical element was limited to three prayers of Vasilko with the introduction of the style of lamentations into them; "Praise" Vasilko then listed his worldly virtues; There was no "praise" for Yuri; the story ended with a list of princes, headed by Yaroslav, who escaped from the Tatars, "with the prayers of the Holy Mother of God." The originality of this restored version of the story about Batu's army in the Trinity Chronicle, and, consequently, in the Chronicler of 1305, compared with the close to it, but more common version in the Lavrentievskaya, is beyond doubt. All extensions, reductions or replacements in the Lavrentievskaya in comparison with what was read about Batu's rati in the Chronicler of 1305 could only be made by the one who copied this Chronicler in 1377 with his own hand, i.e., the mnich Lawrence. His authorial contribution to the story of Batu's army can now, therefore, be easily discovered.

Lavrenty began his work on the text of the protographer imaginary by skipping that accusatory tirade about the non-brotherly love of the princes, which was undoubtedly read in the Chronicler of 1305 and, going back to the Ryazan vault, was directed against Prince Yuri Vsevolodovich.

In the Laurentian Chronicle, the entire Ryazan episode is abbreviated, but at the same time, neither the negotiations of the Ryazan people with Yuri Vsevolodovich, nor his refusal to help them are even mentioned; there is no formidable tirade caused by all this. There is, moreover, no mention of the Tatar ambassadors to Yuri in Vladimir; discarding it along with everything else in the introductory episode about Ryazan, Lavrenty took into account, however, this mention below: it begins that “praise” to Yuri, on which the whole story about Batu’s rati ends in the Laurentian Chronicle and which was not in Troitskaya and in the Chronicler 1305. This is his own afterword to the story as a whole, and Lavrenty begins with the detail of the protograph omitted at the beginning. “Byakhut bo before sent the ambassadors of their wickedness to the bloodsuckers, saying: be reconciled with us; he (Yuri) does not want to, like a prophet to say: battle is glorious, it is better to eat the world of the cold. The detail about the Tatar ambassadors from the context condemning for Yuri Vsevolodovich (in the protograph) was thus transferred by Lavrenty to his own laudatory context. Therefore, the entire “praise” as a whole is permeated with a polemic that is understandable only to contemporaries. It has long been the custom of Russian chroniclers to argue with what was issued from the protograph during correspondence. Let us recall the controversy of the Kiev chronicler about the place of Vladimir's baptism. In the same way, in this case, the “praise” to Yuri by the mnich Lavrenty polemicizes with the angry invective of the Ryazan that was omitted during the correspondence of the protographer. “Praise” from the very first words opposes the accusation of Prince Yuri of non-brotherly love from the very first words with something directly opposite: “because the wonderful Prince Yuri, rushing to keep God’s commandments ... remembering the word of the Lord, if he says: about seven you will know all the people, as you are my disciples, love one another." That "praise" to Yuri is not at all an obituary written immediately after his death, but a literary monument with a great perspective on the past, is immediately evident from his literary sources. It is all, as it were, woven from selections in the previous text of the same Laurentian Chronicle. The basis was the "praise" to Vladimir Monomakh read there under 1125, expanded with extracts from articles about Yuri's father, Prince Vsevolod, and his uncle, Andrei Bogolyubsky.

The mosaic selection of chronicle data applicable to Yuri about his ancestors: father Vsevolod, uncle Andrei and great-grandfather Vladimir Monomakh, in response to the negative characterization of him from the rewritten protograph, omitted at the beginning, is a literary device, in any case, not a contemporary. The task of historical rehabilitation would have been fulfilled by a contemporary, of course, in a different way. Only a biographer from another era could have had so few true facts about the person being rehabilitated. Of all the “praise”, after all, only the insert about Yuri’s construction activities can be recognized as a specific sign of this historical person, and even then the words “set many cities” mean not so much facts as a legend far removed from them, in terms of the time of occurrence. And everything else is just abstract signs of other people's book characteristics transferred to Yuri. And it is remarkable that this reception by Lavrenty is not limited to “praise”; it extends to the entire previous story about the invasion itself. Something, however, was introduced into it from the same chronicle even before Lawrence by the previous editors of this story.

There is every reason to attribute most of the timing of selections from stories about Polovtsian raids to the events of 1237 to Lawrence himself; even the author’s afterword, which once ended the narrative of the raid of 1093 by the Primary Kiev Code (“Behold, I am a sinner and I anger God a lot and often and often sin every day”), Lavrenty repeated in full, with only a characteristic addition: “ But now we will rise to the predicted one. The entire subsequent passage is again saturated with similar previous borrowings. It is based on the annalistic article of 1015 about the death of Boris and Gleb; but there is a borrowing from the article of 1206. As we see, a new literary image is being built on a borrowed basis: Gleb's lamentation for his father and brother grows in Yuri into a rhetorical lamentation for the church, the bishop and "about people" who are sorry above themselves and their family. The lament itself is borrowed from the story of the death of Vsevolod's wife, Yuri's mother.

Further processing of the protograph under the pen of Lavrenty resulted in the transfer to Yuri, sparingly represented there, of the features and signs of the main (originally) actor, Rostov Vasilko, as well as Andrei Bogolyubsky and Vasilko's father, Konstantin (under 1175, 1206 and 1218). Lavrenty deliberately does not convey, however, the words of the protographer about the burial of Vasilko: “Do not be afraid to hear singing in a lot of weeping”; them, like the date, he dates lower to Yuri. And in place of these words taken from Vasilko - before his secular "praise" - Lavrenty again places something that refers not to Vasilko, but to Yuri: a detail about putting Yuri's head into the coffin, in the protograph, most likely, not read at all.

So, the entire literary work of Mnich Lavrenty, within the article about Batu's army, is focused on one image of Prince Yuri. In order to remove from him the shadow imposed by the previous chronicle writing, the imaginary Lawrence showed a lot of ingenuity and diligence. It was hardly so simple to select everything that could be useful from separate pages and lines of ten chronicle articles (under 1015, 1093, 1125, 1175, 1185, 1186, 1187, 1203, 1206, 1218) about six different people; transferred their features to Yuri, under the pen of Lawrence, St. Boris and Gleb, Vladimir Monomakh and Andrei Bogolyubsky, Vsevolod and his princess, and finally, even Vasilko, who was killed at the same time as Yuri. At the same time, it is immediately clear that the goal that guided Lawrence’s pen was inextricably linked with his title of “mniha”: to the semi-folklore style of military stories, which was inherent in the story in the protograph, Lavrenty with all decisiveness opposes the abstract rhetorical style of lives with prayers, “weeping” and "commendations". Not colloquial speech, but a book, not an echo of a song, but a quotation, characterize his taste and techniques. A quote from the previous content of the monument is, by the way, in Lavrenty's own afterword to the entire chronicle: the book writer also rejoices, having reached the end of books”; of the three likenesses of the “writer”, one, in any case, Lavrenty also found in the chronicle he was copying: under 1231, one of his predecessors of the chroniclers asks in prayer, “yes ... directing, I will bring the ship of words into a quiet haven ".

The time when Lawrence’s work was completed is known (from the same afterword) with accuracy: between January 14 and March 20, 6885 (1377). Gorodetsky". Lavrenty's addition to quotes from an article of 1125 in "praise" to Prince Yuri (about "great dirty tricks on the lands" from the evil bloodsuckers of the Polovtsians and Tatars - "even here a lot of evil has been done"), hinting at something quite specific and only recently what happened “here”, i.e., where Lavrenty worked, this postscript, dated, like the entire manuscript, from January - March 1377, shows that Lavrenty wrote the chronicle in Nizhny Novgorod: in a protracted strip of Tatar “dirty things to the lands "was around 1377 of the three cities of Bishop Dionysius, only Lower. In the same "praise" to Yuri, Lavrenty mentioned only the Nizhny Novgorod Annunciation Monastery. For such a preference, the reason could only be that Lavrenty himself belonged to the brethren of this monastery. The story about the beginning of the monastery where the chronicle was compiled, even if in a brief form of a simple mention, was, as you know, in the custom of Russian chroniclers for a long time.

It is known about the Nizhny Novgorod Annunciation Monastery that it was indeed founded by Yuri Vsevolodovich, simultaneously with the Nizhny, in 1221, but, having fallen into decay later, was restored anew, just shortly before 1377. Coinciding with the heyday of the newly renovated Konstantin Vasilyevich of the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod principality, this restoration of the oldest of the monasteries of the new capital of the principality did not go without the usual in such cases in ancient Russia literary undertaking: a chronicle started up in the monastery.

In the vaults that reflected our regional chronicle of the XIV-XV centuries. (in the annals of Simeonovskaya, Ermolinskaya, Rogozhskaya, Nikonovskaya, etc.), there is a number of news that indicate that, indeed, the Nizhny Novgorod Annunciation Monastery was the focus of the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod regional annals of the very era when one of its monks lived and worked, " writer" of the Laurentian Chronicle named after him.

And since the glorification of the person who built the monastery where this chronicle was kept was also a custom among Russian chroniclers for a long time, this, however, partly explains increased attention Lawrence to Yuri Vsevolodovich. In the vault of Lawrence, the prince-builder, praised by him in 1377, belonged to the distant past. The very scope of "praise" to Yuri Vsevolodovich in the Laurentian Chronicle is too bold for the homegrown initiative of a simple "mnih". Prince Yuri, equated in the Ryazan vault with the "cursed" Svyatopolk, should be turned into a similar St. Gleb the Christ-lover and martyr; on the loser, who ruined both his princely “root” and his principality, to transfer for the first time in the northeast, long before similar experiments on the ancestors of the Moscow princes, the dynastic reflection of the name of Monomakh - a simple monk would hardly have thought and dared without appropriate directives from above. And that Lavrenty actually had such directives can be seen again from his afterword, where he twice, in solemn terms, named his direct literary customers: Prince Dmitry Konstantinovich and Bishop Dionysius. The initiative of the latter should, of course, be attributed to all the bold originality of the independent annalistic work done by Lawrence.

The Kiev-Pechersk monk, abbot of one of the Nizhny Novgorod monasteries, Dionysius in 1374 was appointed bishop of the bishopric restored in the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod principality, which was in charge of the three main cities of the principality - Suzdal, Nizhny Novgorod and Gorodets. In 1377, Dionysius achieved the establishment in the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod principality instead of a bishopric - an archdiocese, that is, he made the Suzdal church independent of the Moscow metropolitan. In order to substantiate his claims to this independence, Dionysius conceived the compilation of an annalistic code, entrusting this matter to the monk Lawrence. From the same plan of Dionysius, the whole work of Lawrence on the literary portrait of Yuri himself is explained.

Byzantium recognized the right to be allocated to an archdiocese autonomous from the metropolitan for areas and lands with a certain historical and cultural prestige, in the sense that this prestige was then understood: the strength of secular power had to correspond to the strength and antiquity of the Christian cult, which could best be externally confirmed , in the eyes of Byzantium, private cults of local saints. In search of such prestige for his Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod land - before trying to turn it into an archdiocese - Dionysius had to pay special attention to the ktitor of the main monasteries and temples in this land, the builder of one of its cities and the first of the princes who owned all three cities at once. It is not for nothing that in the features given by Lawrence to Prince Yuri there are so many things that could impress just the Greeks: as a dynast of the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod princes, he is presented to them as the second Monomakh, a relative of the Byzantine Basils; in his political failures, he is not only justified as a martyr, like St. Boris and Gleb, but also endowed with one specific virtue that they lacked: more devotion to the bishop than to his wife and children; and this is nothing more than a borrowing from the teachings of Patriarch Luke Chrysoverg to Andrei Bogolyubsky in that letter to him (1160), which was then constantly used in Russia as the norm of princely-episcopal relations. Finally, Lawrence gave Yuri a hagiographic tinge, even with a direct mention of Yuri's relics.

The compilation of the Laurentian Chronicle is inextricably linked, as we see, with the establishment in Russia at the initiative of Dionysius of the second archbishopric. And since the implementation of the project in 1382 was undoubtedly preceded by a relatively very long period of its reflection and comprehensive preparation, there is reason to recognize the compilation of the Laurentian Chronicle as one of the acts of this preparation. If, indeed, as one might think, the predecessor of Patriarch Nile, Patriarch Macarius, while negotiating with Dionysius between 1378 and 1379, invited him to Byzantium even then, then to collect him there just at the indicated time, in 1377 and the hasty production of the Chronicler, which could be needed as a document in negotiations with the patriarch, could have been timed. And since the trip of Dionysius did not take place at that moment, but two years later, when the hastily prepared list could be whitewashed and supplemented, our Laurentian Chronicle remained at home.

How, however, did the attempt of this brave Pecheryan connected with it to turn the then-forming all-Russian state from the Moscow road to the Nizhny Novgorod road ended?

The role of Moscow could not be clear to contemporaries until 1380. The year of the Kulikovo victory should have clarified a lot. Returning from his diplomatic trip only two years later, Dionysius could not immediately but fully appreciate what had happened in his absence. This must explain the obvious change in his political orientation, starting from 1383: he again goes to Constantinople, but not on business of the Suzdal archdiocese, but "on the administration of the Russian metropolis." This time, appointed to the metropolitanate himself, Dionysius, on his way back to Kyiv, is captured by Vladimir Olgerdovich and dies in 1384 in the “apprehension”, according to the chronicle, that is, in custody, having survived only a year of Dmitry Konstantinovich of Suzdal. The archbishopric he created died out by itself, as the political disintegration of the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod principality. In the same year, when one of those still resisting Suzdal princes, "fathers", the Moscow governors caught in the "Tatar places" and the wilds, in Suzdal they were accidentally found walled up in the wall taken out by Dionysius in 1382 from Tsargrad "The Passion of the Lord" - a silver kivot with images of several holidays and an inscription, in some ways reminiscent of final postscript of Lawrence. “The divine passions,” the inscription says, “transferred from Constantinople by the humble Archbishop Dionysius to the holy archbishopric of Suzdal, Novgorod, Gorodets... under the holy Patriarch Nile, under Grand Duke Dmitry Konstantinovich.” The same as Lavrenty's list of cities in the title of Dionysius, the same name of Prince Dmitry Konstantinovich "great", as if Moscow does not exist. The find was triumphantly transferred to Moscow like a trophy. A similar fate awaited the Chronicler Lavrenty: also intended, according to the plan of its compilers, to challenge Moscow for its primacy, it served, however, almost to strengthen its own Moscow chronicle tradition: at least Muscovites quickly adopted what was new in it in a purely literary attitude. Like the hagiographic revision of the article of 1239 by Lavrentiy from Suzdal, the compiler of one of the Moscow collections also makes his own hagiographic additions to it from the life of his Moscow princely patron, Alexander Nevsky. In the form of a kind of collection of his own princely lives, Tver begins at the same time to build its own chronicle. Abraham's Smolensk reference imitates Lawrence in the afterword. Finally, the entire Laurentian Chronicle as a source is used by the compilers of large all-Russian collections of Photius and his successors.

The Laurentian Chronicle is the most valuable monument of ancient Russian chronicle writing and culture. The latest and highest quality edition of her text is the publication of 1926-1928. , edited by Acad. E. F. Karsky. This work has long since become a bibliographic rarity, and even its phototype reproduction, undertaken in 1962 under the supervision of Acad. M. N. Tikhomirov (circulation 1600 copies), could not satisfy the needs of historians, linguists, cultural workers and ordinary readers interested in Russian history. The reprint of Volume I of the Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles, carried out by the publishing house "Languages of Russian Culture", is intended to fill this gap.

The manuscript is stored in the National Library of Russia under code number F. p. IV. 2. The parchment codex, in a small "ten", on 173 sheets, was written mainly by two scribes: the first scribe copied ll. 1 vol. - 40 about. (first 8 lines), the second - ll. 40 vol. (starting from the 9th line) - 173 vol. The only exceptions are ll. 157, 161 and 167: they are inserted, violate the natural order of the line and have spaces at the end, which indicates the inability of the scribe to proportionally distribute the text on the sheet area. Text on ll. 157-157 rev., 167-167 rev. rewrote the third scribe (however, his handwriting is very similar to the handwriting of the first scribe), and on ll. 161-161 rev. - the second scribe, but it was continued (from the end of the 14th line of the sheet turnover) by the third scribe. The first 40 sheets of the manuscript are written in one column, the next - in two columns.

The main (second) scribe named himself in a postscript to ll. 172 rev. - 173: it was the monk Lavrenty, who rewrote the chronicle in 1377 for the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod Grand Duke Dmitry Konstantinovich, with the blessing of the Bishop of Suzdal Dionysius. According to the name of the scribe, the chronicle received the name Lavrentievskaya in the scientific literature.

At present, omissions are found in the manuscript of the Laurentian Chronicle: between ll. 9 and 10 are missing 6 sheets with the text of 6406-6429, after l. 169-5 sheets with the text of 6771-6791, after l. 170-1 sheet with articles 6796-6802 The content of the lost sheets can be judged from the Radzivilovskaya and Troitskaya chronicles similar to those of Lavrentievskaya.

There is another opinion in the literature - not about the mechanical, but about the creative nature of the work of Lavrenty and his assistants on the chronicle in 1377. Some researchers suggest, in particular, that the story of the Batu invasion of Russia was revised as part of the Laurentian Chronicle. However, an appeal to the Trinity Chronicle, regardless of the Lavrentiev one transmitting them as a common source, does not confirm this opinion: Troitskaya in the story of the events of 1237-1239. coincides with the Laurentian. Moreover, all the specific features of the story about the Batu invasion as part of the Laurentian Chronicle (ideological orientation, literary methods of the compiler) organically fit into the historical and cultural background of the 13th century. and cannot be taken outside chronological framework this century. A careful study of the features of the text of the story about the Batu invasion of Russia as part of the Laurentian Chronicle leads to the conclusion that it was created in the early 80s. 13th century

Little is known about the fate of the Laurentian Chronicle manuscript itself. On the polluted 1, you can make out the entry “The Book of the Rozhesvensky Monastery of Volodimer Skago”, which is not very confidently dated to the end of the 16th - beginning of the 17th century. But in the XVIII century. the manuscript ended up in the collection of the Novgorod Sophia Cathedral, where a copy was made of it in 1765 in the Novgorod Seminary (stored in the BAN under the code 34.2.32). In 1791, among other manuscripts, the Laurentian Chronicle was sent from Novgorod to Moscow and came to the chief prosecutor of the Synod, gr. A. I. Musin-Pushkin. In 1793, A. I. Musin-Pushkin published Vladimir Monomakh’s Teachings based on this manuscript, and at the beginning of the 19th century, the count presented the manuscript as a gift to Emperor Alexander I, who transferred it to the Public Library. In any case, this happened before 1806, since on September 25, 1806, the director of the library, A.N. Olenin, presented a copy of the Laurentian Chronicle to Count S.S. 1 was made by the hand of A. N. Olenin, the manuscript itself was rewritten by the archaeographer A. I. Ermolaev - it should be noted that paper with the dates 1801 and 1802 was used).

The record that the manuscript of the Laurentian Chronicle belonged to the Vladimir Nativity Monastery served as the basis for the assumption that the monk Lavrenty wrote in Vladimir and that his work remained in the possession of the Nativity Monastery. Meanwhile, clear traces of finding the Laurentian Chronicle in the 17th century are found. in the Nizhny Novgorod Caves Monastery, where it was directly used in compiling a special Caves chronicler. The Caves chronicle is known to us in two lists: 1) RSL, f. 37 (collected by T. F. Bolshakov), No. 97, 70-80s. XVII century; 2) State Historical Museum, coll. Moscow Assumption Cathedral, No. 92, con. 17th century Considering that Dionysius, prior to his appointment as a bishop, was the archimandrite of precisely the Caves Monastery, and that the annals of Laurentius were preserved in this monastery until the 17th century, we can with good reason suggest that the Grand Duke's vault was rewritten in 1377 in the Nizhny Novgorod Pechersk Monastery by local monks.

When publishing the Laurentian Chronicle, the Radzi Vilov Chronicle was used in various interpretations.

The Radzivilov Chronicle is stored in the Library Russian Academy Sciences in St. Petersburg under the code 34.5.30. Manuscript in 1, on 251 + III sheets. The chronicle is located on ll. 1-245, the watermarks of this part of the manuscript - three views of the bull's head - are reproduced in N. P. Likhachev's album under Nos. 3893-3903 (but the reproduction is not entirely accurate). On ll. 246-250 rpm additional articles were rewritten in a different handwriting and on a different paper (“The Tale of Danilo the Humble Abbot, who walks like his feet and eyes”, “The Word of St. Dorotheus, Bishop of Tours, about the 12 apostle saints”, “The Word of St. Epiphanius, the legend of the prophets and prophetesses” ), filigree - two types of a bull's head under a cross - are reproduced in N. P. Likhachev's album under Nos. 3904-3906. “Judging by the paper, the time of writing the Radzivilov list should most likely be attributed to last decade XV century, ”N.P. Likhachev came to this conclusion. We believe that the date can be significantly refined. According to the observations of N.P. Likhachev, sign No. 3864 from the documents of 1486 is “completely similar in type to the signs of the annals.” If we talk about signs No. 3896-3898, then they literally coincide with the signs of the Book of 16 Prophets (RSL, f. 304 / I, No. 90) - according to our updated data (in N. P. Likhachev’s album, the signs of the Book of the Prophets are reproduced under No. No. 1218-1220 with distortions The book of the prophets was written by Stefan Tveritin from October 1, 1488 to February 9, 1489. Thus, the paleographic data make it possible to narrow the dating interval to 1486-1488. A. V. Chernetsov’s observations are characterized by the same linguistic features as the main text, and which can be attributed to 1487. 3 Taken together, these results make it possible to date the Radzivilov Chronicle around 1487. Additional articles on folio 246 -250 rev. (which, by the way, differ in the same linguistic features as the text of the chronicle) can be attributed to the 90s of the XV century.

The Radzivilov Chronicle is front (decorated with more than 600 miniatures), and this determines its outstanding significance in the history of Russian culture. At present, the version about the Western Russian origin of the Radzivilov Chronicle, in the zone of contact between the Belarusian and Great Russian dialects, most likely in Smolensk, seems to be the most reasonable (A. A. Shakhmatov, V. M. Gantsov). The analysis inclines to the same opinion stylistic features miniatures (which have experienced significant Western European influence) and their content.

The nature of the postscripts in the margins of the chronicle shows that the manuscript was created in an urban environment in which the veche orders of ancient Russian cities, their freedoms and privileges were approved. Later records of the late XVI - early XVII in. in the Old Belarusian language testify that the manuscript at that time belonged to representatives of the petty gentry, residents of the Grodno district. At the end of the manuscript there is an entry that the chronicle was donated by Stanislav Zenovevich to Prince Janusz Radziwill. Therefore, around mid-seventeenth in. the chronicle from small holders passed into the possession of the highest stratum of the Belarusian nobility. Through the mediation of Prince Boguslav Radziwill, who had close family ties with the Prussian magnates, in 1671 the chronicle entered the Königsberg Library. Here, in 1715, Peter I got acquainted with it and ordered to make a copy of it (now: BAN, 31.7.22). In 1761, when Russian troops occupied Koenigsberg, the chronicle was taken from the Koenigsberg library and transferred to the Library of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg.

The Radzivilov chronicle brings the presentation up to 6714, and due to the fact that the sheets were mixed up in the original, the events from the end of 6711 to 6714 turned out to be set out earlier than the news of 6711-6713. According to the study of N. G. Berezhkov, articles 6679-6714. in the Radzivilov Chronicle (as well as in the Lavrentiev Chronicle) they are designated according to the ultra March style, therefore, 6714 is translated as 1205.

A comparison of the Laurentian Chronicle with the Radzivilov Chronicle and the Chronicler of Perey glorifying Suzdal shows that a similar text of these chronicles continues right up to 1205 (6714 in ultra-March dating). Following the end of the common source in Lavrentievskaya, the date 6714 is repeated, but already in the March designation, and then follows a text that differs significantly from the Chronicler of Pereyaslavl of Suzdal; Radzivilovskaya, on the other hand, generally breaks off at the article of 1205. Therefore, it can be assumed that certain stage in the history of the Vladimir chronicle. At the same time, from the observations of A. A. Shakhmatov over articles for the 70s. 12th century it follows that the Lavrentievskaya was based on an earlier version of the code of 1205 (in the Radzivilovskaya and the Chronicler of Pereyaslavl of Suzdal, tendentious additions of the name of Vsevolod Big Nest to the news of his brother Mikhalka).

The possibility of reconstructing the Trinity Chronicle was substantiated by A. A. Shakhmatov, who discovered that the Simeon Chronicle from the very beginning (but it begins only from 1177) to 1390 is similar to the Trinity Chronicle (judging by the quotes of N. M. Karamzin). Capital work on the reconstruction of the Trinity Chronicle was undertaken by M. D. Priselkov, but in the light latest discoveries new ancient Russian chronicle monuments, the reconstruction of the Trinity Chronicle should be revised and refined.

The Trinity Chronicle, by the nature of its news, is obviously compiled at the Moscow Metropolitan See, but the chronicler's predilection for the inner life of the Trinity-Sergius Monastery identifies the hand of a monk of the Sergius Monastery. An analysis of the stylistic manner and ideological orientation of the work of the archer allows us to more accurately determine the personality of the compiler of the annals of 1408 - he turned out to be the outstanding writer of Medieval Russia, Epiphanius the Wise, who, being a monk of the Trinity-Sergius Monastery, served as secretary of Metropolitan Photius Simeonov Chronicle under 6909; the inscription was published by Acad. A. S. Orlov in "Bibliography of Russian inscriptions of the XI-XV centuries." Ed. Acad. Sciences of the USSR, 1936, pp. 81-82. Shakhmatov A. A. A note on the place of compilation of the Radzivilov (Kenigsberg) chronicle list. M., 1913; Gantsov V. M. Peculiarities of the language of the Radzivilov (Koenigsberg) chronicle list // IORYAS, 1927, v. 32, p. 177-242.

The Tale of Bygone Years according to the Laurentian List

Original name: The Tale of Bygone Years According to the Laurentian List

Publisher: Type. Imperial Academy of Sciences

Place of publication: St. Petersburg.

Publication year: 1872

Number of pages: 206 p.

The Tale of Bygone Years is the oldest chronicle that has actually come down to us, presumably created around 1113 by the monk of the Kiev-Pechersk monastery Nestor.

Nestor introduces the history of Russia into the mainstream of world history. He begins his chronicle with a biblical legend about the division of the earth between the sons of Noah. Citing a lengthy list of the peoples of the whole world (extracted by him from the "Chronicle of Georgy Amartol"), Nestor inserts a mention of the Slavs into this list; elsewhere in the text, the Slavs are identified with the "Noriks" - the inhabitants of one of the provinces of the Roman Empire, located on the banks of the Danube. Nestor talks in detail about the ancient Slavs, about the territory occupied by individual Slavic tribes, but in particular detail about the tribes that lived on the territory of Russia, in particular about the “meek and quiet custom” glades, on whose land the city of Kyiv arose. Askold and Dir are declared here as the boyars of Rurik (besides, “not of his tribe”), and it is they who are credited with a campaign against Byzantium during the time of Emperor Michael. Having established from the documents (the texts of treaties with the Greeks) that Oleg was not Igor's governor, but an independent prince, Nestor sets out a version according to which Oleg is a relative of Rurik, who reigned during Igor's youth (not confirmed by later studies). In addition to brief weather records, the Tale includes texts of documents, retellings of folklore legends, plot stories, and excerpts from translated literature. Here you can find a theological treatise - "The Philosopher's Speech", and a hagiographical story about Boris and Gleb, and paterinic legends about the Kiev-Pechersk monks, and a church eulogy of Theodosius of the Caves, and a laid-back story about a Novgorodian who went to tell fortunes to a magician. Thanks to the state view, breadth of outlook and literary talent of Nestor, The Tale of Bygone Years was not just a collection of facts of Russian history, but an integral, literary history of Russia.

Scholars believe that the first edition of The Tale of Bygone Years has not come down to us. Its second edition, compiled in 1117 by the abbot of the Vydubitsky monastery (near Kiev) Sylvester, and the third edition, compiled in 1118 by order of Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich, have been preserved. In the second edition, only the final part of the Tale was revised. This edition has come down to us as part of the Laurentian Chronicle of 1377, as well as other later chronicles. The third edition, according to a number of researchers, is presented in the Ipatiev Chronicle, the oldest list of which - Ipatiev - dates from the first quarter of the 15th century.

The Laurentian Chronicle" is a parchment manuscript containing a copy of the annalistic code of 1305, made in 1377 by a group of scribes under the guidance of the monk Lavrenty on the instructions of the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod prince Dmitry Konstantinovich from the list of the beginning of the 14th century. The text begins with "The Tale of Bygone Years" and is brought up to 1305. The manuscript does not contain news for 898?922, 1263?1283, 1288?94. Code 1305 was the Grand Duke's "Vladimir Code", compiled during the period when the Grand Duke of Vladimir was Prince Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tver. It was based on code 1281, supplemented ( from 1282) Tver chronicle news. Lawrence's manuscript was written in the Annunciation Monastery in Nizhny Novgorod or in the Vladimir Nativity Monastery. In 1792 it was acquired by A.I. Musin-Pushkin and subsequently presented to Alexander I, who gave the manuscript to the Public Library (now named after M. .E.Saltykov-Shchedrin), where it is stored.

"Laurentian Chronicle" is one of the oldest Russian chronicles, which is an important historical and literary monument. Eastern Slavs. It received its name after the monk Lavrenty, who, by order of the Suzdal and Nizhny Novgorod Grand Duke Dmitry Konstantinovich, in 1377 rewrote it from the old? a chronicler who recounted events up to 1305.

The Laurentian Chronicle also includes entries from other chronicle sources, thanks to which the events of Russian history are described until 1377. The beginning of the publication of the chronicle dates back to 1804, but only in 1846 it was published in full in the 1st vol. PSRL (2nd reprint. 1872; 3rd reprint 1897). Historians of the 19th century made a great contribution to the study of the text of the Laurentian Chronicle, which is complex in its composition, and later? A.A. Shakhmatov, M.D. Priselkov, D.S. Likhachev.

"Laurentian Chronicle" is a valuable source of research into the events associated with the campaign against the Polovtsy of Novgorod-Seversky Prince Igor Svyatoslavich. In the entry under 1186 (erroneously, instead of 1185), a story is placed here, beginning as follows: "That same summer, when Olgovi's grandchildren were thought of as Polovtsy, they didn't go around that summer with all the princes, but they themselves went about themselves, saying: "We are not princes, but we will also get our own praises? And having taken off at Pereyaslavl, Igor with two sons from Novgorod Seversky, from Trubech Vsevolod brother him, Olgovich Svyatoslav from Rylsk, and Chernigov to help and go into the land of their [Polovtsy]."

The story of the "Laurentian Chronicle" is much shorter than the story of the "Ipatiev Chronicle" about the same campaign of Igor Svyatoslavich, nevertheless, in a number of places it gives details that are not in? The Lay on Igor's Campaign?.

The text of the chronicle, containing the story of the campaign of Igor Svyatoslavich in 1185, was again published in the 1st vol. PSRL (Moscow: Izd-vo AN SSSR, 1962, stb. 397?

Sources:

1804, 1824 -- partial edition of chronicle [not completed];

"Laurentian Chronicle", 1st ed., St. Petersburg, 1846 (? Complete collection of Russian chronicles?, Vol. 1);

"Laurentian Chronicle", 2nd ed., no. 1?3, L., 1926?28;

"Laurentian Chronicle", 2nd ed. (phototype reproduction), M., Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1962.

Literature:

Komarovich V.L., "Laurentian Chronicle" // "History of Russian Literature", vol. 2, part 1, M. ? L., 1945;

Nasonov A.N., "History of Russian Chronicle XI ? early XVIII v.", M., 1969, ch. 4;

Franchuk V.Yu., "On the Creator of the Version of Prince Igor's Campaign against the Polovtsy in 1185 in the Laurentian Chronicle" // "? A Tale of Igor's Campaign? and His Time", M., ? Nauka?, 1985, p. 154? 168;

Shakhmatov A.A., "Review of Russian chronicle codes of the XIV-XVI centuries", M., L., 1938, pp. 9-37;

Priselkov M.D., "The history of Russian chronicle writing in the 11th-15th centuries", M., 1996, pp. 57?113.

Topic tags:

Old Russian chronicles