Przhevalsky Nikolai Mikhailovich - famous Russian explorer Central Asia, was born on March 31, 1839 in the Kimborov estate, Smolensk region. His father was a descendant of the Cossack Kornila Parovalsky, who moved in the second half of the sixteenth century to serve him and took the surname Przhevalsky. After graduating from the military academy, Przhevalsky was sent to suppress the uprising in, where, after the suppression of the rebellion, he taught history at the school.

Przhevalsky sought a transfer to Siberia for a long time to study its immense nature. At the end of March 1867, Przhevalsky arrived in Irkutsk, where, while awaiting his appointment, he worked hard in the library of the Siberian Department of the Geographical Society, studying the Ussuri region in detail.

Seeing a serious attitude towards, the Chief of Staff, Major General Kukol, took an ardent part in it, who, together with the Siberian Department of the Geographical Society, arranged for Przhevalsky on a business trip to the Ussuri Territory. The business trip took place already in April 1867; its official purpose was statistical research, but this made it possible for Przhevalsky to simultaneously study the nature and people of a new, little explored region. The prospect for the traveler was the most enviable; he went to, then to Ussuri, Lake Khanka and to the shores of the Great Ocean to the borders of Korea.

The journey along the Ussuri in this order lasted 23 days, since Przhevalsky walked more along the coast, collecting plants and shooting birds. Having reached the village of Busse, Przhevalsky went to Lake Khanka, which was of great interest in botanical, and especially in zoological terms, since it served as a station for migratory birds and insects. Then he went to the coast, and from there, already in winter, he undertook a difficult expedition to the still unknown part of the South Ussuri Territory. Wandering along unknown paths, spending the night in the cold, the travelers endured many hardships and, despite this, they covered 1,060 km within three months. On January 7, 1868, the travelers returned to the village of Busse.

In the spring of 1868, Przhevalsky again went to Lake Khanka in order to study its ornithological fauna and observe the passage of birds - and achieved excellent results in this regard. Having replenished his research with new excursions during the spring and summer of 1869, the researcher went to Irkutsk, where he lectured on the Ussuri region, and from there to St. Petersburg, where he arrived in January 1870. The results of the journey were a major contribution to the available information about the nature of Asia, enriched the collections of plants and gave the Geographical Society a unique ornithological collection, to which, due to its completeness, later research could not add much. Przhevalsky delivered a lot interesting information about the life and customs of animals and birds, about the local population, Russian and foreign, explored the course of the Ussuri, the Khanka basin and the eastern slope of the Sikhote-Alin ridge, and finally collected thorough and detailed data on the Ussuri region.

Here he published his first Journey in the Ussuri Territory. The book was a huge success with the public and scientists, especially since it was accompanied by: tables of meteorological observations, statistical tables of the Cossack population on the banks of the Ussuri, the same table of the peasant population in the South Ussuri Territory, the same table of 3 Korean settlements in South Ussuri Territory, a list of 223 species of birds in the Ussuri Territory (of which many were first discovered by Przhevalsky), a table of spring migration of birds on Lake Khanka for two springs, a map of the Ussuri Territory by the author. In addition, Przhevalsky brought 310 specimens of different birds, 10 skins of mammals, several hundred eggs, 300 species of different plants in the amount of 2,000 specimens, 80 species of seeds.

On July 20, 1870, the Highest order was issued to send Przhevalsky and Pyltsov to Northern Tibet for three years and, and on October 10 he was already in Irkutsk, then arrived in Kyakhta, and from there on November 17 he went on an expedition. Through the Eastern part of the great Przhevalsky went to Beijing, where he had to stock up on a passport from the Chinese government and on January 2, 1871 arrived in the capital of the Heavenly Empire.

During the two months spent on this expedition, 100 versts were covered, the entire area was mapped, the latitudes were determined: Kalgan, Dolon-Nor and Dalai-Nor lakes; the heights of the traversed path were measured and significant zoological collections were collected. Having rested in Kalgan for several days, she set off on her way to the West.

This time the purpose of the expedition was to visit the capital of the Dalai Lama - Lhasa, where no European had yet penetrated. Przhevalsky outlined a path for himself through Kuku-Khoto to Ordos and further to Lake Kuku-Nor. On February 25, 1871, a small expedition set out from, and exactly a month later, the travelers arrived on the shores of Lake Dalai-Nor. The expedition moved slowly, making transitions of 20 - 25 kilometers, but the lack of reliable guides greatly hampered the matter.

The area explored by the expedition was so rich in botanical and zoological material that Przhevalsky stopped in some places for several days, such as in Suma-Khoda, Yin-Shan, which were first explored. However, most of the way ran through the waterless desert of the southern outskirts of the Gobi, where the foot of a European had not yet set foot, and where travelers endured unbearable torment from the scorching heat.

The study of the Yin Shan ridge finally destroyed the previous hypothesis about the connection of this ridge with, about which there were many disputes between scientists - Przhevalsky resolved this issue. For 430 kilometers, Przhevalsky explored the Yellow River, meandering among the hot sands of the Ordos, and determined that the Yellow River () does not represent branches, as the Europeans used to think about it.

On the way back, the expedition captured a vast unexplored area along the right bank of the Yellow River, partly went the old way; but now the cold pursued the travelers. On the eve of the new year, Przhevalsky arrived in Kalgan, and then went to Beijing. The ten-month journey was completed, and the result of it was the study of almost completely unknown places in the Ordos desert, Ala Shan, the Southern Gobi, the In Shan and Ala Shan ridges, the determination of the latitudes of many points, the collection of the richest collections of plants and animals, and abundant meteorological material. .Having written a report on the expedition, Przhevalsky left Beijing and already on March 5, 1872, set out in the same composition from Kalgan with the intention of making his way to Tibet and reaching Lhasa.

At the end of May, the expedition again arrived in Dyn-Yuan-In. The travelers spent more than two months in the mountainous area of Gan-su. Mountain ranges and peaks, still unknown to geographers, many new species of animals, birds and plants were identified by Przhevalsky. The rich vegetation of the surrounding mountains aroused in Przhevalsky a desire to get to know this area better, and he alone went to the Cheibsen shrine, where he arrived in the first days of July and stayed here until the 10th. Here he made a new botanical discovery - a red birch was found.

On October 12, the expedition reached Lake Kuku-Nora, on the shore of which they pitched their tents. Having explored the lake and its environs, Przhevalsky moved to Tibet. Having crossed several mountain ranges and passed through the eastern part of Tsaidam, a vast plateau abounding in salt lakes, the expedition entered Northern Tibet. Two and a half months (from November 23, 1872 to February 10, 1873) spent in this harsh desert were the most difficult period of travel. On January 10, 1873, the expedition reached the Blue River (), further than which this time Przhevalsky did not penetrate into Asia.

The results of this expedition, one of the most remarkable in Lately both in idea and in its implementation in practice, were colossal. Within three years (from November 17, 1870 to September 19, 1873) 11,000 kilometers were covered; collected 238 species of birds in the amount of 1,000 specimens; 42 species of mammals, including 130 skins, and many different types of fish, reptiles, insects and plants. In addition, the hydrography of the Kukunor basin, the ranges in the vicinity of this lake, the heights of the Tibetan plateau, and the least accessible parts of the Gobi were studied. At various points the magnetic declination and the tension of terrestrial magnetism are determined; meteorological observations, made four times a day, brought the most curious data about the climate of these remarkable areas.

In 1876-1877, during the Second Central Asian Expedition, Przhevalsky discovered the Altyn-Tag Range, proved that Lake Lobnor was fresh and not salty (as was previously believed), and made new observations of birds. In 1879-1880 Przhevalsky led the Third Central Asian Expedition. Together with a detachment of 13 people, he went down the Urungu River, passed through the Khali oasis, passed the Nan Shan ranges, went to Tibet and from there to the Mur-Usu valley.

Central Asia, discovered new ones, clarified the boundaries of the Tibetan Plateau. The extensive zoological, botanical and mineralogical collections he collected are the pride of many museums in Russia.

Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky (1839-1888)

The famous Russian traveler Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky was the first explorer of the nature of Central Asia. He possessed an amazing ability to observe, was able to collect a large and diverse geographical and natural-scientific material and linked it together using the comparative method. He was the largest representative of comparative physical geography, which originated in the first half of the 19th century.

Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky was born on April 12, 1839 in the village of Kimborovo, Smolensk province, into a poor family. He lost his father at the age of six. He was raised by his mother - a smart and strict woman. She gave her son wide freedom, allowed him to leave the house in any weather, wander through the forest and swamps. Her influence on her son was very great. To her, as well as to the nanny Olga Makarievna, Nikolai Mikhailovich forever retained a tender affection.

From childhood, N. M. Przhevalsky became addicted to hunting. He retained this passion for the rest of his life. Hunting hardened his already healthy body, developed in him a love for nature, observation, patience and endurance. His favorite books were descriptions of travels, stories about the customs of animals and birds, and various geographical books. He read a lot and memorized everything he read to the smallest detail. Often, comrades, testing his memory, took a book familiar to him, read one or two lines on any page, and then Przhevalsky spoke whole pages by heart.

After graduating from the Smolensk gymnasium, a sixteen-year-old boy during Crimean War joined the army as a private. In 1861, he began to study at the Military Academy, after which he was sent back to the Polotsk regiment, where he served earlier. At the Academy, N. M. Przhevalsky compiled the "Military Statistical Review of the Amur Territory", highly appreciated in the Russian Geographical Society and served as the basis for his election in 1864 as a member of the Society. All his life and activities were later connected with this Society.

From an early age, N. M. Przhevalsky dreamed of traveling. When he managed to escape from the regiment in Big city- Warsaw and become a teacher at a military school, he used all his strength and means to prepare for travel. For himself he established the most strict regime: worked a lot in the university zoological museum, botanical garden and in the library. Desk books his at that time were: the works of K. Ritter about Asia, "Pictures of Nature" by A. Humboldt, various descriptions of Russian travelers in Asia, publications of the Russian Geographical Society, books on zoology, especially on ornithology (about birds).

N. M. Przhevalsky took his teaching duties very seriously, prepared thoroughly for classes, and presented the subject in an interesting and exciting way. He wrote a textbook general geography. His book, scientifically and vividly written, at one time enjoyed great success in military and civilian educational institutions and appeared in several editions.

At the beginning of 1867, N. M. Przhevalsky moved from Warsaw to St. Petersburg and presented his travel plan to Central Asia to the Russian Geographical Society. The plan did not receive support. He was given only letters of recommendation to his superiors. Eastern Siberia. Here he managed to get a business trip to the Ussuri region, which was annexed to Russia shortly before. In the instruction, N. M. Przhevalsky was instructed to inspect the location of the troops, collect information on the number and condition of Russian, Manchurian and Korean settlements, explore the paths leading to the borders, correct and supplement the route map. In addition, it was allowed to "make any kind of scientific research." Going on this expedition in the spring of 1867, he wrote to his friend: "... I am going to the Amur, from there to the Ussuri River, Khanka Lake and to the shores of the Great Ocean, to the borders of Korea. Yes! I had an enviable share and it is a difficult duty to explore areas in most of which the foot of an educated European has not yet set foot in. Moreover, this will be my first statement about myself to the scientific world, therefore, you need to work hard."

As a result of his Ussuri expedition, N. M. Przhevalsky gave good geographical description the edges. In the economy of Primorye, he emphasized the discrepancy between the richest natural resources and their insignificant use. He was especially attracted by the Khanka steppes with their fertile soils, extensive pastures and the enormous wealth of fish and poultry.

N. M. Przhevalsky colorfully, in all its charm and originality, showed geographical features Ussuri region. He remarked, among other things, feature nature Far East: "junction" of southern and northern plant and animal forms. N. M. Przhevalsky writes: “It is somehow strange for an unusual eye to see such a mixture of forms of north and south that collide here both in the plant and animal worlds. Especially striking is the view of a spruce entwined with grapes, or a cork tree and a walnut , growing next to cedar and fir. A hunting dog looks for you a bear or sable, but right next to you you can meet a tiger that is not inferior in size and strength to the inhabitant of the Bengal jungle.

N. M. Przhevalsky considered the Ussuri journey as a preliminary reconnaissance before his difficult expeditions to Central Asia. It cemented his reputation as an experienced traveler-explorer. Soon after that, he began to petition for permission to travel to the northern outskirts of China and to the eastern parts of southern Mongolia.

N. M. Przhevalsky defines the main tasks of his first trip through China - to Mongolia and the country of the Tanguts - as follows: "Physical-geographical, as well as special zoological studies on mammals and birds were the main subject of our studies; ethnographic research was carried out as far as possible." During this expedition (1870-1873) 11,800 kilometers were covered. Based on the visual survey of the path traveled, a map was compiled on 22 sheets on a scale of 1: 420,000. Meteorological and magnetic observations rich zoological and botanical collections. The diary of N. M. Przhevalsky contained valuable records of physical-geographical and ethnographic observations. Science for the first time received accurate information about the hydrographic system of Kuku-nor, the northern heights of the Tibetan Plateau. Based on the materials of N. M. Przhevalsky, it was possible to significantly refine the map of Asia.

At the end of the expedition, the famous traveler wrote: “Our journey is over! His success exceeded even the hopes that we had ... Being poor in terms of material means, we only ensured the success of our business with a series of constant successes. Many times it hung in the balance, but happy fate rescued us and gave us the opportunity to make a feasible study of the least known and most inaccessible countries of inner Asia.

This expedition strengthened the fame of N. M. Przhevalsky as a first-class researcher. The Russian, English and German editions of the book "Mongolia and the country of the Tanguts" scientific world, and this work received the most appreciated. Long before the completion of processing the materials of the Mongolian journey, N. M. Przhevalsky began to prepare for a new expedition. In May 1876, he left Moscow to go to Gulja, and from there to the Tien Shan, to Lop Nor and further to the Himalayas. Having reached the Tarim River, the expedition of 9 people headed down its course to Lob-nor. South of Lob-nor, N. M. Przhevalsky discovered the huge Altyn-Dag ridge and in difficult conditions examined him. He notes that the discovery of this ridge sheds light on many historical events, since the ancient road from Khotan to China went "along the wells" to Lop-nor. During a long stop at Lop-nor, astronomical determinations of the main points and a survey of the lake were made. In addition, ornithological observations were made. The discovery of Altyndag by N. M. Przhevalsky was recognized by all geographers of the world as the largest geographical discovery. It established exactly the northern border of the Tibetan Plateau. Tibet was 300 kilometers further north than previously thought.

The expedition failed to get into Tibet. This was prevented by the illness of the leader and a number of members of the expedition, and especially by the aggravation of Russian-Chinese relations. N. M. Przhevalsky compiled a very brief report on his second trip to Central Asia. Some of the materials of this expedition were subsequently included in the description of the fourth trip. IN Soviet time in the archives of the Russian Geographical Society, some previously unpublished materials related to the Lobnor journey were found.

At the beginning of 1879, N. M. Przhevalsky set off on a new, third, journey to Central Asia. The expedition went from Zaisan to the Khami oasis. From here, through the inhospitable desert and the ridges of Nan Shan, which lay along the way, the travelers climbed the Tibetan plateau. Nikolai Mikhailovich described his first impressions as follows: “We entered as if into a different world, in which, first of all, we were struck by the abundance of large animals, little or almost not afraid of humans. orongo males stood in a pose; like rubber balls, little antelopes jumped - hells. After the most difficult transitions, in November 1879, the travelers reached the pass through the Tan-la ridge. 250 kilometers from the capital of Tibet, Lhasa, near the village of Naichu, travelers were detained by Tibetan officials. After lengthy negotiations with representatives of the Tibetan authorities, N. M. Przhevalsky had to turn back. After that, the expedition until July 1880 explored the upper reaches of the Huang-he, Kuku-nor and the eastern Nan-shan.

"The success of my three previous travels in Central Asia, the vast areas that remained unknown there, the desire to continue, as far as I could, my cherished task, and finally, the temptation of a free wandering life - all this pushed me, at the end of the report on my third expedition, to embark on a new journey," writes N. M. Przhevalsky in a book about the fourth journey through Central Asia.

This expedition was more crowded and richer than all the previous ones. The expedition explored the sources of the Huang He and the watershed between the Huang He and the Yang Tzu. These areas, from a geographical point of view, were completely unknown at that time, not only in Europe, but also in China, and were indicated on maps only approximately. The achievement and study of the origins of the Huang-he N. M. Przhevalsky rightly considered the solution of an "important geographical problem." Then N. M. Przhevalsky discovered some ranges unknown to Europeans and not having local names. He gave them names: Columbus Ridge, Moscow Ridge, Russian Ridge. N. M. Przhevalsky gave the name "Kremlin" to the top of the Moskovsky Ridge. To the south of the Columbus and Russian ridges, N. M. Przhevalsky noticed a "vast snow ridge" and called it "Mysterious". Subsequently, this ridge was named after N. M. Przhevalsky by the decision of the Council of the Russian Geographical Society.

Having explored the northern part of the Tibetan plateau, the expedition came to Lop Nor and Tarim. Then the travelers went to Cherchen and further to Keriya, from here through Khotan and Aksu to Karakol to Lake Issyk-Kul. Geographically, this was Przhevalsky's most fruitful journey.

Neither honors, nor fame, nor well-known material security could keep the passionate traveler in place. In March 1888, he completed the description of the fourth trip, and the following month he already had permission and money for a new expedition to Lhasa. In October he arrived in Karakol. Here the entire composition of the expedition was completed and the caravan was prepared for the journey. But N. M. Przhevalsky did not have to go further: on November 1, 1888, in the hands of his employees, he died of typhus. Nikolai Mikhailovich demanded from his employees to spare "neither strength, nor health, nor life itself, if necessary, in order to fulfill ... a high-profile task and serve them both for science and for the glory of our dear fatherland." He himself has always served as an example of selfless devotion to duty. Before his death, Nikolai Mikhailovich said: "I ask you not to forget about one thing, so that they will certainly bury me on the shore of Issyk-Kul, in a marching expedition uniform ...".

His companions chose a flat, beautiful place for the grave on the shore of Issyk-Kul, on a cliff overlooking the lake and the surrounding area. A monument was later erected on the grave from large blocks of local marble with the inscription: "Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky, born on March 31, 1839, died on October 20, 1888. The first explorer of the nature of Central Asia" (dates are indicated according to the old style).

The space of Central Asia, in which N. M. Przhevalsky traveled, is located between 32 and 48 ° north latitude and 78 and 117 ° east longitude. It stretches more than 1000 kilometers from north to south and about 4000 kilometers from west to east. The directions of the routes of the Przhevalsky expedition in this vast space constitute a real network. His caravans traveled over 30,000 kilometers.

N. M. Przhevalsky considered the most important part of the program of all his travels to be physical and geographical descriptions and route-eye survey. He paved and mapped many thousands of kilometers of new, unknown routes to anyone before him. To do this, he made a survey, determined astronomically 63 points, made several hundred determinations of heights above sea level.

Shooting N. M. Przhevalsky produced himself. He always rode ahead of the caravan with a small notebook in his hands, where he entered everything he was interested in. Recorded, upon arrival at the bivouac, N. M. Przhevalsky transferred to a clean tablet.

He had a rare ability to accurately describe the terrain he passed. Thanks to him, the map of Central Asia has changed significantly in all its parts. Science has been enriched with concepts about the orography of Mongolia, northern Tibet, the region of the sources of the Huang-he, and Eastern Turkestan. After hypsometric observations by N. M. Przhevalsky, a relief began to emerge huge country. New mountain ranges have appeared on the map to replace the many mythical mountains marked on ancient Chinese maps.

N. M. Przhevalsky crossed the northern border of Tibet - Kuen-lun in three places. Before him, these mountains were shown on the maps in a straight line. He showed that these mountains are divided into a number of separate ranges. On the maps of Asia before the travels of N. M. Przhevalsky, there were no mountains that make up the southern fence of Tsaidam. These mountains were first explored by N. M. Przhevalsky. He gave names to individual ridges, for example, the Marco Polo ridge, the Columbus ridge. These names appear on all modern maps of Asia. In the western part of Tibet, he discovered and named individual ranges of the Nan Shan mountain system (Humboldt Range, Ritter Range). Geographic map firmly keeps the names associated with the activities of the first scientific researcher of Central Asia.

Before N. M. Przhevalsky’s travels to Central Asia, absolutely nothing was known about its climate. He was the first to give a lively and vivid description of the seasons and general characteristics the climate of the countries he visited. Day after day, carefully, for many years he made systematic meteorological observations. N. M. Przhevalsky gave valuable materials for judging the spread of the humid, rainy monsoon of Asia to the north and west and the border of its two main regions - Indian and Chinese, or East Asian. Based on his observations, the general average temperatures for Central Asia were established for the first time. They turned out to be 17.5° lower than expected.

N. M. Przhevalsky carried out his scientific research, starting with the first Ussuri and including the subsequent four large trips to Central Asia, according to a single program. “In the foreground,” he writes, “of course, there should be purely geographical research, then natural history and ethnography. The latter ... it is very difficult to collect in passing ... In addition, there was too much work for us in other areas scientific research, so that ethnographic observations for this reason could not be carried out with the desired completeness.

Academician V. L. Komarov, the greatest connoisseur of vegetation in Asia, emphasizes that there is no such branch of natural science to which N. M. Przhevalsky’s research would not have made an outstanding contribution. His expeditions opened completely new world animals and plants.

All the works of N. M. Przhevalsky bear the seal of exceptional scientific conscientiousness. He writes only about what he saw himself. His travel diaries are striking in their pedantry and accuracy of entries. On a fresh memory, regularly, according to a certain system, he writes down everything he sees. The travel diary of N. M. Przhevalsky includes: a general diary, meteorological observations, lists of collected birds, eggs, mammals, mollusks, plants, rocks, etc., general notes, ethnographic, zoological and astronomical observations.

The thoroughness and accuracy of the travel records made it possible for their author to complete the complete processing of the materials in a short time.

The merits of N. M. Przhevalsky were recognized during his lifetime in Russia and abroad. Twenty-four scientific institutions in Russia and Western Europe have elected him as their honorary member. N. M. Przhevalsky was an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Moscow University awarded him an honorary doctorate in zoology. The city of Smolensk elected him an honorary citizen. Foreign geographical societies awarded N. M. Przhevalsky their awards: Swedish - the highest award - the Vega medal, Berlin - the Humboldt medal, Paris and London - gold medals, and the French Ministry of Education - the Academy Palm. The London Geographical Society, awarding him its highest award in 1879, noted that his journey surpasses everything that has taken place since the time of Marco Polo (XIII century). At the same time, it was noted that N. M. Przhevalsky was motivated to desperate and dangerous travels by his passion for nature, and to this passion he managed to instill all the virtues of a scientist-geographer and the happiest and most courageous explorer of unknown countries. N. M. Przhevalsky walked tens of thousands of kilometers in difficult conditions, did not undress or wash for weeks, and his life was repeatedly in direct danger. But all this never shook his vigorous state and efficiency. Persistently and persistently he went to his goal.

The personal qualities of N. M. Przhevalsky ensured the success of his expedition. He selected his employees from simple, inexhaustible, enterprising people and treated people of the "noble breed" with great distrust. He himself did not shy away from any menial work. Discipline during the expedition was severe, without pomp and nobility. His assistants - V. I. Roborovsky and P. K. Kozlov - later became famous independent travelers. Many satellites participated in two or three expeditions, and the Buryats Dondok Irinchinov conducted four expeditions together with N. M. Przhevalsky.

The scientific results of N. M. Przhevalsky's travels are enormous and versatile. With his travels, he covered vast areas, collected rich scientific collections, made extensive research and geographical discoveries, processed the results and summed up. He handed over the various scientific collections he had collected to the scientific institutions of Russia: the ornithological and zoological collections - the Academy of Sciences, the botanical - the Botanical Garden.

Fascinating descriptions of the travels of N. M. Przhevalsky are at the same time strictly scientific. His books are among the best geographical writings. These are the brilliant results of the great traveler. His works contain subtle artistic descriptions many birds and wild animals, plants, landscapes and natural phenomena of Asia. These descriptions became classics and were included in special works on zoology, botany, and geography.

N. M. Przhevalsky considered the compilation of a detailed report on the expedition carried out to be the most important thing. Returning from the expedition, he used every opportunity to work on the report, even at random stops. N. M. Przhevalsky began a new expedition only after the publication of a book about the previous one. He wrote over two thousand printed pages about his travels. All his works, upon their publication in Russian, immediately appeared in translations into foreign languages Abroad. It happened that editions of N. M. Przhevalsky's works abroad diverged faster than in Russia.

N. M. Przhevalsky had no rivals in enterprise, energy, determination, resourcefulness. He literally yearned for unknown countries. Central Asia attracted him with its unexplored nature. No difficulties frightened him. According to the general results of his work, N. M. Przhevalsky took one of the most honorable places among the famous travelers of all times and peoples. His work is an exceptional example of a steady pursuit of his goal and the talented fulfillment of his task.

Fearlessness, selfless love for science, fortitude, purposefulness and organization of Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky make him related to the people of our era.

The main works of N. M. Przhevalsky: Notes of General Geography, Warsaw, 1867 (2nd ed., 1870); Journey in the Ussuri region 1867-1869, St. Petersburg, 1870 (new ed., M., 1937); Mongolia and the country of the Tanguts; Three-year journey in East mountainous Asia, St. Petersburg, 1875 (vol. I), 1876 (vol. II); From Kulja to the Tien Shan and Lob Nor, Izvestia of the Russian Geographical Society, 1877, No. 5; Third trip to Central Asia, St. Petersburg, 1883; The fourth journey through Central Asia, St. Petersburg, 1888.

About N. M. Przhevalsky:Dubrovin N. F., Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky, Biographical sketch, St. Petersburg. 1890; Zelenin A.V., Travels of N. M. Przhevalsky, St. Petersburg, 1901 (parts 1 and 2); Kozlov P.K., The great Russian traveler N. M. Przhevalsky. Life and travel, L., 1929; Komarov V. L., Botanical routes of the most important Russian expeditions to Central Asia, no. one; Routes of N. M. Przhevalsky, "Proceedings of the Main Botanical Garden", Pg., 1920, v. 34, no. one; The great Russian geographer Przhevalsky. On the centenary of the birth of 1839-1939. Sat. articles. Editor M. G. Kadek, ed. Moscow state university, 1939; Berg L. S., Essays on the history of Russian geographical discoveries, M.-L., 1946; His own, All-Union Geographical Society for a hundred years, M.-L., 1946.

Nikolai Przhevalsky and the subspecies of the wild horse discovered by him

April 12 (old style - March 31) marks the 178th anniversary of the birth of the famous traveler, explorer, geographer Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky. What most people know about him is that he led expeditions to Central Asia and that a subspecies of wild horse was named after him. However, there were much more interesting facts in his biography. For example, the fact that he won money for the first expedition in cards, and military intelligence was another purpose of travel. Polish journalists even suggested that he was Stalin's real father.

Left: Nikolai Przhevalsky hunting in the vicinity of the Otradnoye estate. Right - Nikolai Przhevalsky, 1876

At one time, Nikolai Przhevalsky was fond of playing cards. A good visual memory often brought him success in the game, in addition, he had his own rules: never have more than 500 rubles with you and always leave the table having won more than 1000. That is how the “golden pheasant” (as the players called him for legendary luck) and received money for the first expedition to Central Asia - he was a novice for the Geographical Society, and it was not possible to get funds in another way. The win was big - 12,000. Przhevalsky knew how to stop in time and promised himself never to play for money again. Since then, he has not even touched the cards.

On this expedition in 1870-1873. Przhevalsky explored Mongolia, China and Tibet and found out that the Gobi is not a hill, as was previously thought, but a hollow with a hilly relief, and Nanshan is not a ridge, but a mountain system, and also discovered 7 large lakes and the Beishan highlands. This expedition brought him worldwide fame.

Central Asian researcher Nikolai Przhevalsky

At the age of 30, Przhevalsky was already a famous scientist and an enviable groom, but he called the marriage bond a “voluntary loop” and believed that in the desert “with absolute freedom and to his liking” he would be “a hundred times happier than in gilded salons that can be purchased marriage." Great Traveler and remained a bachelor until the end of his days.

Przewalski's horse

In addition to research tasks, Przhevalsky's expeditions supposedly had the purpose of military intelligence. And although science always remained in the foreground for the traveler himself, he was still an officer Russian army. Recently, many studies have appeared that prove the fact that Przhevalsky was an intelligence officer and collected information not only for science, but also for the General Staff.

Przewalski's horse

Przhevalsky spent 11 years of his life on expeditions, covering 31,000 km. A new subspecies of wild horses is not Przewalski's only discovery, but it is best known for being named after a traveler. In addition, he discovered dozens of new animal species, including a wild camel and a Tibetan bear (the researcher called it a "pischeater"), and also found 7 new genera and 218 plant species.

Tibetan bear discovered by Przhevalsky

The most incredible legend associated with the name of Nikolai Przewalski was born in 1939, when an article appeared in a Polish newspaper that famous traveler is actually the father of Stalin. Allegedly in 1878, Przhevalsky was in Georgia, where he met 22-year-old Ekaterina Dzhugashvili, and soon her son Joseph was born. Biographers immediately refuted these facts: at that time the researcher was in China. Nevertheless, this version had supporters who confirmed their guesses by the fact that during the years of Stalin's rule the glorification of the traveler began, a film was made about him and a medal was established in his name. But these facts cannot even serve as an indirect confirmation of the truth of the guesses of Polish journalists.

Polish journalists called Przhevalsky the father of Stalin, primarily on the basis of external resemblance

In 1888, Przhevalsky gathered the largest expedition, which was supposed to last 2 years. But after two weeks of serious illness, the traveler suddenly died. Until recently, the cause of death in all sources was called typhoid fever, and modern experts have established a different diagnosis - Hodgkin's disease.

Famous traveler Nikolai Przhevalsky

His last refuge was Karakol - a city named after Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky

Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky (1839-1888) is one of the greatest Russian geographers and travelers. Born in March 1839, in the village of Kimbolovo, in the Smolensk region. The parents of the future traveler were small landowners. Nikolai Przhevalsky studied at the Smolensk gymnasium, after which he entered the service in the Ryazan Infantry Regiment with the rank of non-commissioned officer. Having served and received basic military experience, Przhevalsky entered the Academy of the General Staff, where he wrote a number of sensible geographical works, for which he was accepted into the ranks of the Russian Geographical Society. The end of the Academy fell on the period of the rebellion, in the suppression of which Przhevalsky himself took part. Participation in suppression Polish uprising forced Nikolai Mikhailovich to stay in Poland. Przhevalsky also taught geography at the Polish cadet school. Free time the great geographer devoted gambling entertainment - hunting and playing cards. As Przhevalsky's contemporaries noted, he had a phenomenal memory, which is probably why he was so lucky in the cards.

Przhevalsky devoted 11 years of his life to long expeditions. In particular, he led a two-year expedition to the Ussuri region (1867-1869), and in the period from 1870 to 1885 he led four expeditions to Central Asia.

The first expedition in the region of Central Asia lasted three years from 1870 to 1873 and was devoted to the study of Mongolia, China and Tibet. Przhevalsky collected scientific evidence that the Gobi is not a plateau, but is a hollow with a hilly relief, that the Nanshan mountains are not a ridge, but mountain system. Przhevalsky owns the discovery of the Beishan Highlands, the Qaidam Basin, three ridges in the Kunlun, as well as seven large lakes. In the second expedition to the region (1876-1877), Przhevalsky discovered the Altyntag mountains, for the first time described the now dried-up Lobnor Lake and the Tarim and Konchedarya rivers that feed it. Thanks to Przhevalsky's research, the border of the Tibet highlands was revised and moved more than 300 km to the north. In the third expedition to Central Asia, which took place in 1879-1880. Przhevalsky singled out several ranges in Nanshan, Kunlun and Tibet, described Lake Kukunor, as well as the upper reaches of the great rivers of China, the Huang He and Yangtze. Despite his illness, Przhevalsky also organized the fourth expedition to Tibet in 1883-1885, during which he discovered a number of new lakes, ridges and basins.

Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky and his companions before the last expedition (www.nasledie-rus.ru)

The total length of Przhevalsky's expedition routes is 31,500 kilometers. Przhevalsky's expeditions also resulted in rich zoological collections, which included about 7,500 exhibits. Przhevalsky owns the discovery of several species of animals: a wild camel, a pika-eating bear, a wild horse, later named after the researcher himself (Przhevalsky's horse). The herbariums of the Przhevalsky expeditions contain about 16,000 flora samples (1,700 species, 218 of which were described by science for the first time). The mineralogical collections of Przhevalsky are also striking in their richness. An outstanding scientist was awarded top awards several geographical societies, became an honorary member of 24 scientific institutes of the world, as well as an honorary citizen of his native Smolensk and the capital St. Petersburg. In 1891, the Russian Geographical Society established a silver medal and the Przhevalsky Prize. Until recently, the city of Przhevalsk (Kyrgyzstan) bore the name of the great Russian scientist, who made a huge contribution to the study of Central Asia and world geographical science in general, but was renamed to please the ideological costs of the era of the parade of sovereignties in the CIS. Name N.M. Przhevalsky continues to wear the mountain range, the Altai glacier, as well as some species of animals and plants.

“It can be said with great probability that neither a year earlier nor a year later Lopnor's study would have succeeded. Earlier, Yakub-bek, who was not yet afraid of the Chinese and, as a result, did not curry favor with the Russians, would hardly have agreed to let us go further than the Tien Shan. Now there is nothing to think about such a journey in the midst of the turmoil that<…>began to disturb the whole of East Turkestan ”(N. M. Przhevalsky’s diary. Entry dated August 18, 1877).

In 1888, the great Russian traveler Przhevalsky was preparing for his next, already fifth, campaign in Central Asia. The main goal of the expedition was Lhasa, the heart of Tibet. In October, the participants of the campaign gathered in the city of Karakol to the east of Lake Issyk-Kul. However, a few days before the performance, Przhevalsky suddenly fell ill and died on October 20, 1888. The official cause of his death was typhoid fever.

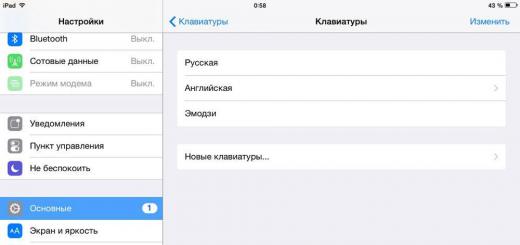

Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky (his Polish surname is correctly rendered as Przewalski) was born in 1839 in the village of Kimborovo, Smolensk province, into the family of an impoverished Belarusian landowner. In 1855, after the gymnasium, Nikolai entered the military service. In 1863 he graduated from the General Staff Academy. Then, for several years, Przhevalsky taught geography and history at the Warsaw Junker School. In 1866, he was assigned to the General Staff and assigned to the Siberian Military District.

In May 1867, the headquarters of the troops of the Amur Region sent Lieutenant Przhevalsky on his first trip - to the Ussuri River - with the assignment to explore the paths to the borders of Manchuria and Korea, and also to collect information about the indigenous inhabitants of the region. During the expedition, Przhevalsky had to participate in the defeat of an armed gang of hunghuz, for which he was promoted to captain and appointed adjutant of the headquarters of the troops. The results of the expedition, despite its small number, exceeded all expectations. Przhevalsky for the first time studied and mapped the Russian shores of Lake Khanka, twice crossed the Sikhote-Alin ridge, mapped large areas along the Amur and Ussuri, published materials on the nature of the region and its peoples.

In November 1870, Nikolai Mikhailovich went on an expedition to Central Asia. He left Kyakhta and moved south. The path ran through Urga (now Ulaanbaatar) and the Gobi Desert to Beijing, where Przhevalsky received permission to travel to Tibet. From there, through the Ordos sandstone plateau, the Alashan desert, the Nanshan mountains and the Tsaidam basin, the detachment went to the upper reaches of the Yellow River and the Yangtze, and then to Tibet. After that, the expedition once again crossed the Gobi, Central Mongolia and returned to Kyakhta. For almost three years, the detachment traveled 11,900 km. As a result, 23 ridges, 7 large and a dozen small lakes were plotted on the map of Asia, huge collections were collected, and Przhevalsky received a large gold medal from the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and a gold medal from the Paris Geographical Society. In addition, he was promoted to colonel.

IN recent decades 19th century to the south and eastern frontiers Russian Empire it was restless. The Russians continued to move further and further south in Central Asia, the British advanced towards them from India, and both of them explained their actions by the need to respond to the activity of the opposite side. The diplomatic and intelligence services of both empires worked hard, confusing the enemy, setting up ingenious traps for him. To strengthen the flanks, Russia and Britain sought to seize the initiative from each other in the Caucasus and Central Asia. This confrontation, which was very reminiscent of a game of chess, Rudyard Kipling called the "big game."

A special role in this game was assigned to Central Asia - a huge mountainous desert region, including the territories of modern Mongolia and Northwestern China (now the Xinjiang Uygur and Tibet Autonomous Regions of the PRC). In the second half of the XIX century. this area was still a blank spot on the map. Both Tibet and Xinjiang formally belonged to China, but in reality they were almost not controlled by the decrepit Qing dynasty. Relations between local peoples and the Chinese were tense, and uprisings often broke out. It was the territory of "geopolitical vacuum", and nature and politics do not tolerate emptiness. For all its isolation, Tibet occupies an extremely important strategic position between India and China, so that it should not be neglected in any case. Xinjiang was directly adjacent to Russia.

In 1866-1867. first in East Turkestan, and then in almost all of Xinjiang, the power of the Qing dynasty was overthrown, and the Tajik Yakub-bek proclaimed the creation independent state Dzhetyshaar ("Seven Cities"). The British supported Yakub-bek in order to create a powerful Muslim state near Russia. Already in the late 1860s. unrest among the Uighurs and Dungans began to seriously affect the Kazakh and Kyrgyz nomadic population of Russia. Trade between Russia and China was almost paralyzed: the western trade route through Xinjiang was immediately blocked, and in 1869 another one was threatened - from Kyakhta to Beijing, now as a result of an uprising in Western Mongolia.

All this, but mainly a clear threat to the Central Asian possessions of Russia, forced the latter to take active steps in the Ili region. By mid-June 1871, Russian troops launched military operations against the Uighurs and soon occupied Gulja almost without a fight. The presence of Russian troops in the Ili region was considered temporary. According to the plan of the Russian Foreign Ministry, they were to leave the territory immediately after the restoration of power by the Qing administration. However, these actions of Russia in China were perceived ambiguously.

Three of Przewalski's four Central Asian expeditions took place during the Ili Crisis, the same decade that Russian troops annexed part of Xinjiang. The expeditions had several goals, among them scientific ones, namely the study of the nature of Central Asia. However, the main task was to obtain intelligence data (on the state Chinese army, about the penetration of intelligence officers of other countries into this region, about the passages in the mountains, the conditions of water supply, the nature of the local population, its attitude towards China and Russia) and in mapping the area.

In 1876, Przhevalsky drew up a plan for a new expedition, which was to go from Kulja to Lhasa, and also explore Lake Lop Nor. In February 1877, Przhevalsky, through the Tarim Valley, came to this mysterious lake, which at that time reached a length of 100 km and a width of 20-22 km. The traveler found it not where the old Chinese maps showed. In addition, the lake turned out to be fresh, not salty, as was then believed. The German geographer F. Richthofen suggested that the Russians discovered not Lop Nor, but another lake. Only half a century later the mystery was solved. It turned out that Lop Nor wanders, changing its position depending on the direction of the flow of two rivers - Tarim and Konchedarya. In addition, the Altyntag mountain range (up to 6161 m high) was discovered on the way, which is the northern ledge of the Tibetan Plateau. In July, the expedition returned to Ghulja. During this trip, Przhevalsky traveled more than 4 thousand km in Central Asia. The expedition failed to make the planned trip to Lhasa due to a sharp deterioration in Russian-Chinese relations.

In March 1879, Przhevalsky went on a journey, which he called the First Tibetan. A small detachment left Zaisan, moved southeast past Ulungur Lake and up the Urungu River, crossed the Dzhungar Plain and reached the Sa-Cheu oasis. After that, having crossed the Nanshan, in the western part of which two snow ridges were discovered, Humboldt (Ulan-Daban) and Ritter (Daken-Daban), Przhevalsky reached the village of Dzun on the Tsaidam Plain. Having overcome the chains of the Kunlun and having discovered the Marco Polo (Bokalyktag) ridge, the detachment approached Tibet itself. Already within its limits, Przhevalsky discovered the Tangla Range, which is the watershed of the Salween and the Yangtze. On the way to Lhasa, the detachment was attacked by nomads, but since excellent shooters were selected for it, both this and subsequent attacks were repelled. When about 300 km remained to Lhasa, the expedition was met by the envoys of the Dalai Lama, who handed Przhevalsky a written ban on visiting the capital of Buddhism: a rumor spread in Lhasa that the Russians were going to kidnap the Dalai Lama.

The squad had to turn back. After resting in Dzun, Przhevalsky went to Lake Kukunor, and then explored the upper reaches of the Yellow River for more than 250 km. Here he discovered several ridges. After that, the detachment again went to Dzun, and from there through the deserts of Alashan and Gobi returned to Kyakhta, having overcome 7700 km. The scientific results of the expedition are impressive: in addition to clarifying internal structure Nanshan and Kunlun, discovering several ridges and small lakes, exploring the upper reaches of the Yellow River, she discovered new species of plants and animals, including the famous wild horse, later called the Przewalski's horse.

In the autumn of 1883 Przhevalsky's Second Tibetan Journey began. From Kyakhta, by a well-studied route through Urga and Dzun, he went to the Tibetan Plateau, explored the sources of the Huang He in the Odontala basin, the watershed between the Huang He and the Yangtze (the Bayan-Khara-Ula ridge). To the east of Odontala, he discovered the Dzharin-Nur and Orin-Nur lakes, through which the Yellow River flows. Passing the Tsaidam plain to the west, Przhevalsky crossed the Altyntag ridge, then followed the southern edge of the Lobnor Lake basin and along the southern border of the Takla-Makan desert to Khotan, and from there reached Karakol. In two years, the detachment traveled almost 8 thousand km, discovered previously unknown ridges in the Kunlun system - Moscow, Columbus, Zagadochny (later Przhevalsky) and Russian, large lakes - Russian and Expeditions. The traveler received the rank of major general. In total, he was awarded eight gold medals and was an honorary member of 24 scientific institutions of the world.

NUMBERS AND FACTS

Main character

Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky, Russian military geographer

Other actors

Ferdinand Richthofen, German geologist and geographer

Time of action

Routes

From Kyakhta, Kulja and Zaisan through the Gobi or Dzungaria to Tibet

Goals

Studying the nature of Central Asia, collecting intelligence data

Meaning

The direction of the main mountain ranges has been established, new ranges have been discovered, the boundaries of the Tibetan Plateau have been clarified, Lake Lop Nor has been described, and extensive natural science collections have been collected.