In the twentieth century, a profession that seemed typical of the Middle Ages was revived and even flourished. Mercenaries took to the battlefields again. The Cold War marked a wild goose renaissance. These figures mainly participated in various campaigns in Africa. A huge unstable continent, many governments that need the services of professional soldiers, enormous wealth that an enterprising and successful soldier of fortune was able to amass - all this made Africa attractive to all kinds of adventurers. One of the most famous such characters was the German Siegfried Müller, who already received the nickname Congo on the Dark Continent.

Siegfried Müller during the Congo crisis.

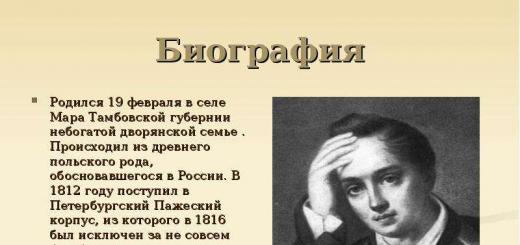

The future soldier of fortune was born in Brandenburg in the family of a career officer in 1920. Then young Müller went through the Hitler Youth and from 1939 he himself served in the Wehrmacht. Siegfried took part in the war against the USSR from the first day. He fought the campaign in the USSR against tank units. However, things did not work out for the Müller family on the Russian bloody fields. Siegfried's father, a Wehrmacht lieutenant colonel, died in 1942, but his son continued to fight. On April 20, 1945, Müller was promoted to officer. He managed to earn the Iron Cross, but this became his swan song. In the spring of 1945, in East Prussia, Müller was hit in the spine by a bullet, and the future mercenary was almost left paralyzed. However, this wound saved Müller from more severe retribution. The wounded man was taken by ship to the west, and he was captured already in the American occupation zone.

However, this man could no longer help but fight. Müller's thought took a peculiar route: “I fought for the National Socialist Reich, and today I am a warrior for the free West.” As a result, having recovered from his wounds, Muller decided to get a job at armed forces. He served in American auxiliary units for two years. Then in North Africa He served for some time as a sapper, removing German mines from Rommel’s campaigns in World War II, then worked as a hotel manager. However, such a life quickly became boring for the former anti-tank man. In 1955, Müller tried to get a job in the Bundeswehr, but was refused. And then Muller decided to become a mercenary.

In the 60s, the main hot spot in Africa was Congo. It was going on in the country Civil War. In the northeastern regions, an uprising of the Simba, the local tribes, broke out against the government of Moise Tshombe. The USSR supported Tshombe's opponents; the opposite side, accordingly, sided with the government. This war, according to local traditions, was waged with incredible cruelty, and firefights from Kalashnikov assault rifles and bomber raids were combined with belief in ancient magic and fighting with spears.

Siegfried Müller.

All sides of the conflict were drenched in blood, but Müller was not particularly concerned about the cleanliness of his vestments. To fight the rebels, Tshombe called in a detachment of white mercenaries. Led by Soldier of Fortune Mike Hoare from Ireland. This dog of war, a veteran of World War II, recruited comrades, primarily in accordance with their professional level. Thus, former opponents on the fronts of the war with Hitler also found themselves under his command. They looked for people among former military personnel in Britain, Belgium, Italy - in a word, everywhere, through old acquaintances. The detachment was assembled in South Africa and from there they were transported to the Congo. It was this group that Muller joined.

Irish mercenary soldier Mike Hoare with his personal bodyguard, Sergeant Donald Grant, 7 September 1964.

By the time the "wild geese" arrived at the front, a significant part of the Congo was already under rebel control. They themselves sincerely believed in the power of magic and went into battle, shouting the name of their leader Pierre Mulele: this cry was supposed to protect the screaming one from bullets. To make matters worse for the government, Congolese soldiers also believed in the power of this magic. Military units fled one after another, often going over to the Simba side.

In such conditions, a detachment of experienced soldiers who did not believe in amulets and spells turned out to be a crushing force. However, Hoar needed any soldiers, so he had to turn a blind eye to some not very pleasant things. Müller stunned him from the first days. The former Nazi showed up with an iron cross on his chest and later defiantly wore the award he received from Hitler everywhere. True, compared to some of his colleagues, he looked almost harmless. For example, one of the mercenaries quickly sold skulls with bullet holes to American aviators as souvenirs. He was too lazy to look for bodies with head wounds and simply shot prisoners to get material for crafts. Against this backdrop of the Congo, Muller with his swastika did not look so intimidating. He was immediately promoted to officer and received the rank of lieutenant.

Mike Hoare, 1964

The very first operations showed that the mercenaries were radically different from the local militias. The jungle rebels were confident in their invulnerability, but often did not even have firearms. Some mercenaries were wounded by spears and clubs during these battles. Another time, the soldiers of fortune shot a detachment just at the moment when the sorcerer was preparing it for battle.

Siegfried Müller.

The spells didn't really help the sorcerer. However, success did not always accompany the mercenaries. It was then that German participation in operations in the Congo became public knowledge. The fact is that two German “wild geese” died, and the corpses were captured by the rebels along with documents. A real storm arose in the press, especially since the attitude towards the German military was, in principle, not the warmest: the art of the Wehrmacht and SS in World War II was still well remembered. When it became clear that one of the mercenary officers was flaunting his Nazi past, Müller acquired scandalous fame.

The first successes brought Hoare's group widespread fame. Adventurers from all over the world flocked to Africa. Müller's infusion of fresh blood gave him the opportunity to distinguish himself as an independent commander at the head of an autonomous unit under Hoare's wing. He received a detachment of forty people under his command. This group fought a war over a vast territory, but, given its good preparation by any standards, remained a serious force. The German gathered all his compatriots into his detachment.

However, the reputation of German mercenaries was based not only on the events of the long-standing war in Europe. The Germans were considered undisciplined and cruel Landsknechts. Moreover, they took the habit of hanging cars with the heads of killed rebels, and in this form they were sometimes caught by journalists. However, they could not complain about the fighting qualities of this gang. Most often, government troops followed the mercenaries, like a thread following a needle, and occupied already recaptured lines. Well, as for claims about moral character, it was difficult to surprise the local population with cruelty. In this war, even ritual cannibalism was regularly encountered, and torture and murder were considered the norm, so by the standards of the African war, Müller’s people did not stand out for their cruelty.

Congolese soldiers search the streets during the Congo crisis in 1964.

But in Europe they looked at the adventures of the “wild geese” with wicked amazement. Congo Muller was hungry for glory and allowed journalists to roam freely around his fighters' positions. Therefore, all the unpleasant stories for the mercenaries (from drunken rampages and looting to the killing of prisoners and posing with their heads on pikes) eventually became public knowledge. Muller himself did not consider it necessary to hide the style of war and calmly talked, for example, about the harsh interrogations of prisoners practiced by his soldiers. Phrases like “If we captured the wounded, we shot them” and “Torture is normal,” spoken with a good-natured smile, evoked strong feelings in the audience, especially when followed by maxims about the war for Western ideals, freedom and brotherhood.

In addition, Crazy Mike Hoare, his immediate commander, was already accumulating complaints against Muller. They concerned the commander's talents themselves. At one point, Müller failed a major operation, and the Irishman, no longer short of people, began to wonder whether he really needed a subordinate whose talents were not always the best, and whose reputation, to put it politely, was peculiar.

In October 1964, Congo Muller nevertheless brought himself under the monastery with his pride and thirst for recognition from the press. Two Italian correspondents filmed the execution of the prisoner at close range. Ironically, the execution of a real murderer was captured on camera, but this detail was no longer included in any correspondence. Well, after Müller himself blurted out to journalists about “jaeger fun, hunting for blacks,” they wrote about him in the GDR, and in the USSR, and in Western Europe, in a word, everywhere. By chance, the scandal occurred at about the same time that the detachment under the command of Müller was ambushed and suffered serious losses. After this, the cup of patience ran out, and Muller forever left not only the Congo, but also the Federal Republic of Germany: for the local public his behavior was too provocative, and for the command he became a walking problem. The former mercenary went to South Africa, where he founded a small security company and died in 1983 in Johannesburg.

It cannot be said that Siegfried Müller was the most ferocious character in the wars of the twentieth century. However, this is the case when a person forges his own reputation. The combination of cruelty and a penchant for shocking made him one of the most odious participants cold war. The romantic myth of white mercenaries in Africa had some basis in reality, but it had its own dark underbelly.

Mercenaries participated in almost all major military campaigns: from Antiquity to the era of the Napoleonic Wars. In the 1960s, after a break of a century and a half, they returned to the stage. And since then, their role in military conflicts has only increased. Photo: ELI REED/MAGNUM PHOTOS/AGENCY.POTOGRAHER.RU

International law does not recognize them as full-fledged combatants, they are deprived of the security guarantees that prisoners of war have, and in some countries they are even outlawed. But the governments of major states, heads of transnational corporations and non-governmental organizations do not hesitate to enter into contracts with them, and in Ireland an entire museum has been created to perpetuate their glory. These people became the heroes of numerous books, from the ancient Anabasis of Xenophon to the modern novels of Frederick Forsyth, and they were given considerable space in the reflections on the ideal state of such outstanding social philosophers of the Middle Ages as Thomas More and Niccolò Machiavelli.

Their name is mercenaries. Condottieri, “wild geese”, soldiers of fortune - at different times they were called differently, but this did not change the essence. Who are they? Ordinary criminals, scum collected to do dirty deeds? Or noble adventurers, “brothers of hot and thick blood”, who for last years saved at least two African countries from bloody internecine wars?

To answer this question, we must first define the terms. Russian generals Those who cannot stand the very idea of a professional army contemptuously call every soldier who receives a salary a mercenary. Actually this is not true. The definition of a mercenary was formulated in the First Additional Protocol to the 1949 Geneva Conventions on the Laws of War. A mercenary is considered a person who, firstly, is specially recruited to fight in an armed conflict, secondly, actually takes direct part in hostilities, and thirdly (this is the main thing), takes part in hostilities, guided by the main Thus, the desire to receive personal benefit and the promised material reward, significantly exceeding the remuneration of military personnel of the same rank, performing the same functions, who are part of the armed forces of a given country, fourthly, is not a citizen of a country in conflict, and finally, fourthly, fifth, is not sent by a State that is not a party to the conflict to perform duties as a member of its armed forces.

Thus, a mercenary differs from a professional soldier (as well as, for example, a foreign volunteer) in that when he fights, he is guided primarily by selfish considerations. Neither the soldiers Foreign Legion French army, nor are members of the Nepalese Gurkha units of the British Armed Forces mercenaries. Yes, these units are not formed from citizens of the countries in whose armed forces they serve, but their salary corresponds to the salary of ordinary military personnel.

From "anabasis" to "wild geese"

For many centuries, military mercenaryism was considered highest degree worthy occupation. The first apology for mercenaries can be considered “Anabasis” by the ancient commander Xenophon (first half of the 4th century BC) - the story of a ten-thousand-strong Greek army who fought in the ranks of the army of the Persian king Cyrus the Younger. And at the end of ancient Greece, mercenary became an extremely respected and very widespread profession. Greeks from the same city-states fought in both the army of Darius and the army of Alexander.

A new rise in mercenary activity occurred in the Middle Ages. The Vikings were among the first to master this profession: they gladly hired themselves into the personal guard of the Byzantine emperors. The famous Norwegian king Harald III was proud to take the position of chief of the emperor's security. During his 10 years in Constantinople (1035-1045), Harald participated in 18 battles, and upon returning to his homeland, he fought in Europe for another 20 years. In Italy, at the end of the Middle Ages, mercenary condottieri, who always had a detachment of experienced soldiers at their disposal, became the main acting force endless wars between city-states. Professionalism reached such heights there that when confronted in battle, the opponents were primarily concerned with outmaneuvering each other through skillful formations of troops, and tried their best not to harm each other. There is a known case when, as a result of a stubborn battle for many hours, only one person was killed.

During the same era, a correspondence discussion took place between Niccolò Machiavelli and Thomas More. The latter, depicting an ideal state in his “Utopia,” argued that its protection should be provided by an army of barbarian mercenaries, since the life of a citizen is too valuable. Machiavelli, whose experience of dealing with mercenaries was not only theoretical, in his famous book “The Prince” argued the exact opposite: mercenaries, whose goal is to get money, are not at all eager to sacrifice their lives on the battlefield. The founder of political realism reasoned quite cynically: a mercenary who suffers defeats is bad, but a mercenary who wins victories is much worse. For obvious reasons, he wonders: is the sovereign who hired him really so strong, and if not, then why not take his place? It must be admitted that the most successful of the Italian condottieri followed exactly the script prescribed by Machiavelli. Most shining example- condottiere Muzio Attendolo, nicknamed Sforza (from sforzare - “to overcome by force”), a former peasant who laid the foundation for the dynasty of the Dukes of Milan.

In the 15th-17th centuries, a decisive role in European wars was played by landsknechts - independent detachments of mercenaries from different European countries. The organization of the Landsknecht detachments was maximally focused on ensuring efficiency. For example, for every four hundred fighters, a translator was assigned from several European languages, and the captain, the commander of the detachment, was obliged to speak these languages himself.

In the 17th century, the famous “flights of the wild geese” began—that’s what Irish mercenary groups called their way to continental Europe. The first such “flight” took place in 1607, and over the next three centuries the Irish, demonstrating desperate courage, fought in all known wars, and not only in the Old World. Irish mercenaries participated in the creation of several states in Chile, Peru and Mexico, four Irish were close aides of George Washington during the Revolutionary War, and the other four signed the Declaration of Independence.

Finally, the welfare of entire nations was based on mass service in foreign countries. A classic example is the Swiss, who offered their swords to all the monarchs of Europe. So, in 1474, the French king Louis XI entered into an agreement with several Swiss villages. The monarch obliged each of them, as long as he was alive, to pay 20,000 francs annually: for this money, the villages were supposed to supply him with armed men if the king was at war and required help. The salary of each mercenary was four and a half guilders per month, and each trip to the field was paid at triple the monthly rate.

"Anabasis" by Xenophon

This is a classic military narrative of Antiquity - the story of the exploits of 13,000 Greek soldiers who contracted to participate in the war of the Persian king Cyrus the Younger against his brother Artaxerxes, who ruled Babylon. In the decisive battle of Kunax (401 BC), a complete victory was won: the Greek mercenaries overthrew the troops of Artaxerxes. Thirsting for the death of his brother, Cyrus the Younger broke through to the tent of Artaxerxes, but was killed, and the Persian part of his army immediately surrendered. The Greeks also entered into negotiations, but were not going to give up: “It is not fitting for the winners to surrender their weapons,” they said. The Persians invited the straightforward Greek commanders to negotiate, promising immunity, but killed them in the hope that the leaderless mercenaries would turn into a herd. But at a general meeting the Greeks chose new commanders (among them was Xenophon, a student of Socrates), who led them home. It took eight months of hard travel from Babylon, along the Tigris, through the Armenian Highlands (here the Greeks saw snow for the first time), through the lands of foreign tribes, with whom they had to fight all the time, but thanks to their courage and training, the Greeks completed the unprecedented march and reached the Black Sea.

African adventures

The widespread use of mercenaries in the pre-industrial era is primarily due to the fact that military victory, due to the relative small number of armies, largely depended on the individual training of each warrior. Everything was determined by how deftly he handled a sling and javelin or a sword and musket, and whether he knew how to maintain formation in a phalanx or square. A trained professional warrior was on the battlefield worth a dozen, or even hundreds of peasant sons, herded into a feudal militia. But only the wealthiest of monarchs could afford to have a permanent professional army, which would have to be fed even in peacetime. Those who were poorer had to hire landsknechts just before the war. It is clear that they received money, at best, as long as it lasted fighting. And more often, the employer ran out of funds earlier, and the mercenaries could only count on victory and capturing trophies.

The advent of the industrial age reduced mercenary activity to almost nothing. The unified production of effective and at the same time easy-to-handle weapons made years of training unnecessary. The time has come for conscript armies. If military wisdom can be taught in just three or four years, if it can be quickly (the appearance of railways) gather people around the country, there is no need to maintain a large army in peacetime. Instead, all men in the country, after undergoing military training, became reservists in a mass mobilization army. Therefore, the First and Second World Wars, where millions took part in the battles, actually went without mercenaries. And they were in demand again in the 60s of the 20th century, when the decolonization of Africa began.

In countries where colonial administrative structures disintegrated, and there were no armies at all, an armed struggle for power immediately began. In this situation, a couple of hundred professional military men, familiar with guerrilla and counter-guerrilla tactics, made president and prime minister of any tribal leader or retired official of the old colonial administration who hired them.

In 1961, a long civil war engulfed one of the richest African states, Congo. Almost immediately after the country declared its independence, the province of Katanga, famous for its diamond mines and copper mines, announced its separation. Self-proclaimed Prime Minister Moise Tshombe began to recruit his own army, the backbone of which was French and British mercenaries, and the conflict instantly fit into the context of the Cold War: the USSR declared support for the central government, which was headed by Patrice Lumumba. Tribal clashes broke out in the Congo, killing tens of thousands of civilians.

In all this bloody whirlwind, in which several tribal groups, UN troops, and Belgian paratroopers took part, mercenaries played a decisive role. It was in the Congo that the stars of the most famous “soldiers of fortune” rose - the Frenchman Bob Denard and the British Michael Hoare, from whose biographies one can write the history of the most famous 20 years of mercenaryism. And the bloodiest: as a result of the events of the 1960-1970s, mercenaries began to be looked at as bandits. It was not for nothing that Denard’s team called themselves les affreux - “the terrible”: torture and murder were the norm in this unit. However, the cruelty of the European “soldiers of fortune” hardly overshadowed the inhumanity of other participants in conflicts in Africa. Michael Hoare recalled with some confusion that he witnessed how Chombov's men boiled a prisoner alive. And the constantly rebellious Simba tribe, which was supported by Cuban and Chinese instructors, was little inferior in cruelty to its fellow countrymen.

Bob Denard

One biographer called him "the last pirate." A sailor in the French navy, a colonial police officer in Morocco, and a professional mercenary, Denard managed to try himself in various roles. In addition to the Congo, the “soldiers of fortune” under his command fought in Yemen, Gabon, Benin, Nigeria and Angola. In the late 1970s, through the efforts of Denard, the Comoros became a promised land for mercenaries. In 1978, he returned to power the republic, which declared independence in 1975, its first president, Ahmed Abdallah, and headed the presidential guard for the next 10 years. At this time, Comoros turned into a real mercenary republic. Denard himself became the largest property owner in the Comoros, converted to Islam and started a harem. After an unsuccessful coup attempt in 1995, Denard, who was evacuated to France, unexpectedly became involved in several criminal cases, not only in his homeland, but also in Italy. Although one of the retired French intelligence chiefs confirmed that the mercenaries almost always acted “at the request” of the French intelligence services, Denard received four years in prison, but did not spend a single day there: during the process, the “last pirate” fell ill with Alzheimer’s disease and died in 2007.

Soldiers of Misfortune

The Renaissance did not last long, and already at the end of the 1970s the decline of traditional mercenaries began. It all started with the trial of white mercenaries captured by government forces in Angola. The authorities of this country, who seemed to have chosen the “path of socialist development,” supported the USSR and its satellites (in particular Cuba). And the process had an obvious political background - it was supposed to demonstrate that Angola had become a victim of aggression by Western intelligence services. The trial was well prepared: from the interrogations of the accused and witnesses, a far from romantic picture emerged of how clever recruiters seduce unemployed alcoholics with easy money. But the “seduced” did not receive leniency: three mercenaries were sentenced to death, and another two dozen went to prison for a long time.

And then off we go. The coup attempt organized by Michael Hoare in the Seychelles ended in shameful failure in 1981. When Hoar and his commandos arrived on the islands under the guise of members of a certain beer club that organizes entertainment tours once a year, a disassembled Kalashnikov assault rifle was found in their luggage at customs. The “tourists” were surrounded, and they barely managed to escape on an Indian Air plane hijacked right there at the airport. In South Africa, where the mercenaries flew, they were immediately arrested, and Hoar ended up in prison, after which he retired.

It turned out even worse with Bob Denard. In 1989, Ahmed Abdallah, his protege as President of Comoros, was killed, and he himself was evacuated by French paratroopers. In 1995, at the head of three dozen fighters, Denard landed in the Comoros, where another three hundred armed people were waiting for him, preparing a new military coup. But the President of Comoros turned for military assistance to France, the country whose assignments Denard had carried out for many years, and the legendary mercenary was betrayed. Paratroopers of the Foreign Legion, who had fought shoulder to shoulder with Bob so many times, surrounded his group and forced him to surrender, and then quietly took him to France.

By the end of the 20th century, mercenarism in its traditional form fell into decline. Just look at the farcical story of the attempted coup in Equatorial Guinea in 2004! The “mercenaries” who participated in it seem to have been recruited from among high-society slackers: for example, the son of the famous Iron Lady Mark Thatcher, Lord Archer and oil trader Eli Kalil were involved in the conspiracy (although among those detained there were also professionals - former South African special forces). The preparation of the plot was discovered by the Zimbabwean special services, the mercenaries were arrested, but they all got off with symbolic sentences, and Mark Thatcher, who lived in South Africa, received a suspended sentence and was sent to London under the supervision of his mother.

Michael Hoar

Nicknamed the Mad Irishman, Michael Hoare fought in British tank units in North Africa during World War II. After retiring, he organized safaris for tourists in South Africa. In 1961, Hoare appeared in the Congo at the head of Commando 4, which consisted of several dozen thugs.

Quite soon, under attacks from UN troops, he withdrew his group to Portuguese Angola and reappeared in the Congo in 1964: Tshombe, who had become prime minister by that time, hired him to suppress the uprising of the Simba tribe, which had previously supported Lumumba.

While carrying out this task, Hoar encountered another celebrity - Che Guevara, who went to Africa to stir up a world revolution. The Cuban commanders were unable to resist Hoar's mercenaries: Che Guevara was forced to flee Africa, and several dozen captured Cubans were hanged. Hoar's commandos, together with Cuban pilots hired by the CIA, also took part in the most famous operation of the Belgian army, as a result of which several hundred white hostages captured by the Simba were freed in the city of Stanleyville.

Just business, nothing personal

The decline of “traditional” mercenaryism was predetermined by a radical change in the international climate. The Cold War is over and the volume secret operations, in which mercenaries participated, fell noticeably. After the collapse of the apartheid regime, South Africa ceased to serve as the main employer, the most important base and source of personnel for mercenaries. The “front of work” has also decreased sharply. African states have at least created national armies, intelligence services and police and no longer felt an urgent need for the services of “soldiers of fortune.” And Western states, due to the all-conquering political correctness, began to hesitate to communicate with mercenaries.

As a result, the always drunk, weapon-laden “wild geese” were replaced by respectable gentlemen with laptops. And it was not clandestine “soldier of fortune” recruitment centers that began accepting orders, but private military companies (PMCs), providing the widest range of services in the field of security. According to experts, today more than two million people are employed in this area, and the total value of contracts exceeds $100 billion a year (that is, twice the Russian military budget).

The end of the 60s and the beginning of the 70s of the 20th century was the peak of success of the “soldiers of fortune” and their public popularity. During this period, Frederick Forsyth writes his famous novel “Dogs of War,” in which noble white warriors give the black inhabitants of the country they captured a platinum deposit. At the same time, the film “Wild Geese” was released, in which the famous Richard Burton (pictured) played the extremely romanticized image of the dignified Colonel Faulkner, whose prototype is said to be Hoare (he also acts as a consultant for the film). As a result, despite the efforts of UN lawyers and Soviet propagandists, mercenaries in the eyes of ordinary people acquired the image not of bloody killers, but of noble adventurers burdened with a burden white man. Photo: GETTY IMAGES/FOTOBANK.COM, EVERETT COLLECTION/RPG |

At first glance, the only difference between representatives of such a serious business and Hoare and Denard is that the former are officially registered and have given an official commitment not to participate in any illegal transactions. However, it is not a matter of legal formulas. In the 90s of the 20th century, it suddenly became clear that legal customers represented by states, transnational corporations and international non-governmental organizations are much more profitable than candidate dictators. And the most important element of military operations of the last 10-15 years has been the outsourcing of quite important public functions to private military companies.

The current flourishing of private military companies is caused both by a revolution in military affairs and by changes in the political and social situation. On the one hand, the technological revolution made the existence of mass mobilization armies meaningless. New means of warfare based on computer and information technology, again, as in the pre-industrial era, brought to the fore an individual fighter - an expert in the use of modern weapons. On the other hand, the public in developed countries is extremely sensitive to losses among the soldiers of their armies. The death of military personnel is expensive not only figuratively, but also literally: for example, the death of each American soldier costs the Pentagon at least half a million dollars: special payments (in addition to insurance) and special family benefits, including funding for medical care and education. And a mercenary, even though his salary is several times higher than that of a military man, costs much less. Firstly, he receives his big money not for several decades in a row, but within a short period of time. Secondly, the state does not pay for his death or injury - these risks in the form of insurance amounts are initially included in the cost of the contract with the PMC. And the losses of private military companies are sometimes comparable to those of the army. For example, in 2004, in the Iraqi city of Fallujah, as a result of an attack on a convoy guarded by Blackwater employees, four guards were captured by a crowd, killed and burned.

Private military companies made their presence felt already in the mid-1990s. Retired US military personnel hired by Military Professional Resources took part in preparing operations for Bosnian Muslims and Croats against Serbian military forces. However, these operations still fit into the old concept of military confrontation of the Cold War era: mercenaries were invited to operate in areas where the United States and Western European countries considered it inconvenient to participate directly. A true demonstration of the new face and new functions of mercenaries was the operation in Sierra Leone, where an extremely bloody civil war had been going on for several years.

A group called the Revolutionary United Front fought against the government of Sierra Leone, whose militants cut off the hands of civilians in order to intimidate them. Government troops suffered one defeat after another, the rebels were already 30 kilometers from the capital, and the UN could not form a peacekeeping force. And then the government hired a private military company, Executive Outcomes, created in South Africa mainly from former special forces soldiers, for $60 million. The company quickly formed a light infantry battalion, which was equipped with armored personnel carriers, recoilless rifles and mortars and was supported by several attack helicopters. And it took this battalion only a couple of weeks to defeat the anti-government forces.

The situation in the country has stabilized so much that it was possible to hold the first elections in 10 years. The nine-month contract with Executive Outcomes soon expired. The transnational mining companies that financed this operation from behind the scenes considered it a done deal. And they were wrong: the civil war began again. This time, UN peacekeeping forces, assembled mainly from units of African states, finally got involved. The peacekeeping operation, which cost about $500 million each year, ended in 2005 without significant results. An audit carried out by UN officials revealed the monstrous unpreparedness of the “blue helmets”: they operated without armored vehicles or air support and even almost without ammunition - there were only two cartridges for each rifle! And soon the government of Sierra Leone again turned to a private military company, which, among other things, began to rescue UN peacekeepers...

Far from being angels

Employees of one of the largest American private military firms, Blackwater, have become notorious. In 2007, they staged a shootout in the center of Baghdad, killing 17 civilians. After this scandal, Blackwater changed its name to Xe Service, which allowed the Pentagon to enter into a new contract with the company to train Iraqi troops worth half a billion dollars. Another high-profile scandal occurred with employees of the ArmourGroup company, who were guarding the American embassy in Kabul. In 2009, it turned out that they were organizing drunken orgies on the territory of the diplomatic mission.

Profitable business

According to experts from the American Brookings Institution, the market for PMC services is over $100 billion a year, and over two million people participate in their activities. Such “grands” as DynCorp and Xe Service employ tens of thousands of people. But PMCs with a staff of several hundred employees are much more common. Most PMCs are registered in offshore companies, but, as a rule, their leaders and personnel are Americans and British. These companies are happy to welcome veterans of Gurkha units, former soldiers of the Fijian peacekeeping battalion in Sinai, and retirees of the Philippine Marine Corps. And recently, private military companies from Serbia have been particularly successful in the market.

Changing of the guard

This story has become a textbook example of the ineffectiveness of UN peacekeeping and the effectiveness of PMCs. Experts pointed out that private military companies, firstly, do not waste time on political agreements within the Security Council and overcoming bureaucratic barriers. Secondly, unlike governments developing countries, whose troops participate in peacekeeping operations, they do not skimp on the maintenance and provision of their forces. And thirdly, contracting to carry out a specific military task for a certain amount, PMCs, unlike states that receive about a million dollars a year from the UN for each peacekeeping battalion, are not at all interested in delaying the operation.

But the real flowering of private military companies began after US and NATO troops entered Afghanistan and Iraq. It soon became clear that the alliance did not have enough personnel to conduct auxiliary and related operations: escorting convoys, protecting government and international organizations, security of all kinds of warehouses. These services were offered by mercenaries, contracts with which were no longer concluded by the governments of developing countries, but by the State Department and the US Department of Defense. The American military department even created a special department responsible for concluding contracts with private military companies.

In 2008, up to 20,000 PMC employees were already working in Iraq, while the size of the military group reached 130,000 soldiers and officers. As American troops withdraw, the Pentagon is handing over more functions to private military companies, including, for example, training Iraqi troops and police. Accordingly, the number of mercenaries is growing: according to experts, by 2012 it could reach 100,000 people. The same thing is happening in Afghanistan, where companies like DynCorp and Blackwater have become essentially private armies.

The sharply increased demand for mercenary services has even created a personnel shortage. To perform simple security functions, private military companies began to hire local residents en masse, something they had previously tried not to do. Too active recruitment of personnel in Afghanistan even led to a conflict with the country's leadership. The Afghan president issued an ultimatum demanding an end to the activities of PMCs luring military personnel from the regular army. And the growing shortage of specialists with combat experience (retirees from the USA and Great Britain are no longer enough) leads to completely unexpected results. According to rumors, South Africa's special forces forces have been reduced by almost half due to a sharp outflow of personnel into the private sector, where salaries can reach thousands of dollars a day.

Russian specialists have also found their place in the modern mercenary market. International Charters, registered in Oregon, hired both retired American paratroopers and former Soviet special forces in the 1990s, who worked together and effectively in Liberia, where a bloody civil war broke out, killing tens of thousands of people. And this is not surprising: in the mercenary international, former opponents get along well with each other. Perhaps this is a consequence of the personnel policy of the management of private military companies, which, as a rule, care little about the past of their subordinates and who fought on which side before. In the community of modern mercenaries, both former Serbian special forces soldiers are equally highly valued (human rights activists have repeatedly criticized the British company Hart Group for hiring large groups of Serbs who fought in Bosnia and may be involved in war crimes) and their colleagues from Croatia.

This “promiscuity” of private military companies can be explained simply: if you require a candidate to be a mercenary to have combat experience, then it is hardly possible to place high moral demands on him. And several high-profile scandals related to the personnel of various PMCs serve as confirmation of this. And yet, the demand for the services of modern mercenaries is growing. Despite all the ambiguity of the experience of private military companies, it should be recognized that they are becoming an important military force not because politicians change their moral guidelines, but because military technologies are rapidly changing.

Although, as is commonly believed, the twentieth century radically changed the methods of warfare, its goals, weapons and tactics, on the threshold of the new millennium, various types of companies suddenly appeared again, offering well-trained and experienced fighters to states and large international corporations at reasonable prices. This business has especially flourished in recent years in African countries.

Mercenaries offer their services quite openly - on the Internet. They are ready to work in any country in the world and perform tasks of any complexity. The composition of their troops is international: among them are people from Western Europe and the USA, and “soldiers of fortune” from Australia, Africa and Latin America.

Firms offering mercenary services today receive one profitable order after another. There are especially many clients in Africa. After all, after the end of the Cold War, neither the United States nor the former colonial powers see any point in actively supporting the governments of small African states. And therefore, the legal - or not so legal - regimes of those countries where political stability is still far away have to defend their right to power themselves. At the same time, the armies at their disposal are sometimes in a sorry state.

This is where the idea usually arises of using the services of some “private army,” as mercenaries are called.

The best known is the multinational corporation Executive Outcomes (EO). The emphatically inexpressive name can be translated from English as “effective execution.” The company was founded in 1989 in South Africa. Executive Outcomes became famous after operations in Angola and Sierra Leone. In the latter, the mercenaries, as they themselves claim, simply saved the legitimate government of the country.

In Sierra Leone, a civil war began in 1992, government troops suffered one defeat after another, and the rebels occupied more and more territories. Finally, the government turned to mercenaries for help. Executive Outcomes employees arrived at the scene of hostilities and quickly turned the tide of events.

The citizens of Sierra Leone were especially touched by the fact that the country's armed forces themselves were transformed under the influence of mercenaries. Previously, the undisciplined army terrorized and plundered the local population. The mercenaries introduced other procedures. Soldiers caught drunk or accused of “unworthy” behavior were simply beaten. Within a few months, the rebels fled. Democratic elections were held in early 1996, and at the end of that year the government and the rebels signed a Peace Treaty.

However, this whole story also has a downside. As Newsweek magazine wrote in 2002, for the successful military operation the government of a small African country paid the firm $15 million. In addition, there are suggestions that Executive Outcomes has acquired a stake in the trade of diamonds and other minerals in Sierra Leone.

But the problem is not only the high cost of mercenary services. According to a special UN report, among the clients of Executive Outcomes are not only legitimate governments of African states, as Executive Outcomes chief Iben Barlow assures journalists. Private companies engaged, for example, in mining in Sierra Leone, also turn to the company for help. And perhaps Georgetown University expert Genbert Howe is right when he says that the relationship of African governments with mercenaries is reminiscent of a Faustian bargain with the devil: you solve your current problems, but sacrifice sovereignty and raw materials for it. Many experts express themselves less poetically: in their opinion, it’s just newest look colonialism.

In 1998, the South African government passed the Foreign Military Assistance Act, prohibiting mercenarism. And on January 1, 1999, Executive Outcomes ceased to exist, at least under that brand name. However, it is known that in the summer of 1998, the ranks of the UNITA partisans were joined by about 300 foreign mercenaries, most of whom were former employees of the already dissolved EO.

Restoring order in African states, the EO used powerful weapons: armored personnel carriers equipped with 30-mm guns, BTR-50 amphibians, four-barreled 7.62 mm and 0-A-622 machine guns, Land Rovers with mounted machine guns and anti-aircraft weapons, radio interception systems, Soviet Mi helicopters -24, Mi-8 and Mi-17. To transport units, EO used two Boeing 727s purchased for $550,000 from American Airlines, and Soviet MiG-23s as attack aircraft.

The level of salaries in the EO was not uniform: for example, officers received 2-13 thousand dollars a month depending on experience and the region where they had to operate, instructors - 2.5 thousand dollars, pilots - 7 thousand. In addition, All employees were provided with insurance. The annual income of the SW, according to official data, ranged from 25 to 40 million dollars.

Opponents of the mercenary trade also point to the fact that firms like Executive Outcomes operate, if not completely illegally, then at least in a certain legal niche, without violating the relevant laws only because there are simply no such laws regulating their activities. And then, is there a limit to the omnivorousness of mercenaries - what tasks are they not ready to take on? Or does the principle apply here that whoever pays the money calls the tune, even if this music is more like the roar of shells?

It is also debatable whether governments themselves have the right to transfer the protection of the borders and population of the country, i.e. in fact, part of their powers, which the voters gave them, to a private company, which, moreover, must be paid from the state budget? Why then the army and the police? Finally, ethical considerations are cited as a decisive argument against mercenaries.

However, the “soldiers of fortune” themselves are least bothered by these considerations. "I'm a professional soldier. I have a job and I do it," Eban Barlow, chief of Executive Outcomes, responded evasively when asked by a Newsweek reporter whether he really doesn't care who he kills.

In addition to Sierra Leone, mercenaries actively participated in hostilities in Angola. But no peace and stability of this African country"soldiers of fortune" did not bring. Quite the opposite. Since the former Portuguese colony declared independence in 1975, there has been a civil war for 25 years. Mercenaries act either on the side of government forces or on the side of the rebels. And the state is sinking deeper and deeper into bloody chaos.

No one knows exactly how many lives the civil war has already claimed, but we are talking about millions of dead. The situation is complicated by difficult weather conditions: at the end of last week, representatives of Western humanitarian organizations issued a warning that due to severe drought in September, Angola will face another famine, which means that the number of victims will increase again.

And yet the warring parties are in no hurry to lay down their arms. Who is fighting in Angola?

These are former allies who fought three decades ago for the country's independence from Portugal: the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Union for the Total Liberation of Angola (UNITA), led by Jonas Savimbi. Both forces, having defeated the Portuguese, were unable to come to an agreement with each other and share power. As a result, the MPLA became the ruling party, and the opposition UNITA continued the armed struggle - this time against the MPLA government troops.

However, where did both sides get the money to wage war with each other for a quarter of a century and invite mercenaries? Experts have no doubt: both the country’s authorities and the rebels receive funds for combat operations from the sale of diamonds, deposits of which were discovered in Angola. So it is not surprising that the warring parties are showing such interest in precisely those Angolan provinces where the diamond mines are located.

The city of Saurimo, the capital of the Angolan province of Lunda Sul, knew better times. Rows of completely useless and no longer working street lamps stretch along wide and empty streets with chipped asphalt. And the Portuguese-style houses lined up along their sides are crumbling with faded paint and plaster.

Against the background of this picture, a high wall stands out, on which a huge diamond, sparkling with polished edges, is painted. Through a narrow door in the wall you can enter a strictly guarded room, in which there is nothing except a couple of chairs. Several diamond seekers usually languish here. They are waiting to be let into the next room. There they will offer the found stones for sale to Frederick Schroemaekers. The merchant does not care who brings him the diamonds and where they come from.

“I’m simply not interested in this. The main thing is that they bring me diamonds. I never ask where sellers get them. And many of them won’t even want to answer this question. In our business, it’s not customary to ask questions. The main thing is to do your job well ".

Frederick Schroemaekers is about 30 years old. He is Belgian by nationality and works for the Leather Company International, which operates in Angola with the permission of the country's government.

Diamond trading in Angola is a very profitable business. After all, if, for example, buyers give only 2-3 dollars for an Australian diamond weighing one carat, then for an Angolan stone of the same weight they pay 300-400 dollars.

It was these diamonds that became a stumbling block on the path to peace in Angola. The leader of the UNITA group, Savimbi, finds more and more excuses, and does not want to transfer the diamond provinces he holds to the authority of the central government of the country. But he is obliged to do this according to the Peace Treaty between UNITA and the government. The rebels understand that otherwise they will not be able to resist the ruling MPLA party, which has a strong financial and economic basis, for long.

The latter, moreover, enjoys the support of the United States and the UN Security Council. However, the West provides assistance to former Marxists based on purely practical considerations. Developed industrial countries are showing big interest to the rich reserves of oil and other minerals in Angola.

The Angolans could not boast of their lives even in socialist times. But when the scale of capitalist entrepreneurship fell on Angola, the social situation in this African country worsened even more. The minimum salary for civil servants in Angola is $24. And this is exactly the amount an ordinary Angolan brings home every month, if, of course, he has a job.

24 dollars. With this money in the city of Saurimo in the province of Lunda Sul you can buy 20 kilograms of rice or 12 cans of beer. Almost all goods are brought here by plane from a thousand kilometers of coastline, since Saurimo is a small, government-held island in the middle of UNITA-controlled territories. Despite the dire poverty, only three international humanitarian organizations operate in the province. Local Catholic Bishop Doent Eugenio Alcorzo explains it this way: “It seems to me that there are two reasons for this. Firstly, everyone thinks that the province of Lunda is rich because it has diamond deposits. Although this is not entirely true. They, of course, there are, but they do not bring any benefit to ordinary people. Secondly, it seems to me that many foreign governments do not want to participate in the restoration of this region, since the province has a strategically important location, and foreign countries are afraid that they will be accused of persecuting some "selfish interests."

The deputy governor of the province for social affairs, Raul Junior, also believes that the local population has nothing from the wealth of the region. “The money that should have gone to the development of Lunda Sul ends up not only in the treasury of the central government. Diamonds are mined here by all and sundry: both individuals and well-organized and armed units of UNITA. As a result, chaos arises that does not allow we can take advantage of natural resources for the benefit of the local population."

Although foreign observers name not only the UNITA group among the illegal diamond seekers. Diamonds worth at least one billion US dollars are transported outside the province every year. Angolan state-owned gem trading firm receives only a tenth of this gigantic sum, according to official figures. The rest of the money through illegal means ends up in approximately equal shares in UNITA accounts and in the pockets of high-ranking functionaries from the ruling MPLA, as well as generals from the government army.

In 1977, the Organization of African Unity adopted a convention that attempted for the first time to provide a legal definition of mercenary activity. However, the main document is Additional Protocol 1 to the Geneva Convention of 1949, also adopted in 1977.

According to Article 47 of the protocol, a mercenary is any person recruited to participate in an armed conflict locally or abroad and who takes part in hostilities. A mercenary receives a material reward for service that is significantly higher than that paid to military personnel of the same rank who are members of the army of that country. The mercenary is not a citizen of a country involved in the conflict, and is not sent by another country to the conflict zone to perform official functions.

The Russian Criminal Code gives the following definition of a mercenary: a person who acts for the purpose of receiving material reward and is not a citizen of a state participating in an armed conflict, and is also not a person sent to perform official duties in the conflict zone (Article 359 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation).

In the Russian Federation, the participation of a mercenary in an armed conflict is punishable by imprisonment for up to 7 years; for recruiting mercenaries you can get up to 8 years, and if the recruitment is carried out by a person using his official position - up to 15. However, nothing is known about such sentences yet.

The concept of a mercenary, given in the footnote to this article, is based on the definition of this concept in Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 (see International protection of human rights and freedoms. Collection of documents. M., 1990, pp. 570 - 658) .

The prohibition of mercenarism is contained in the UN General Assembly Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among States in accordance with the 1970 UN Charter: “Each State has the obligation to refrain from organizing or encouraging the organization of irregular forces or armed bands, including mercenaries, for invasion of the territory of another state" (see International law in documents. M., 1982, p. 7). Mercenary as a phenomenon was characteristic of the Middle Ages, but it has become widespread in recent years, especially during the so-called local wars. Cases of mercenarism also occur during bloody conflicts in the territory of the former Soviet Union. In this regard, establishing criminal liability for this act and classifying it as a crime against the peace and security of mankind puts criminal legal means in the hands of justice in the fight against mercenarism. Military advisers who do not take direct part in hostilities and are sent to serve in a foreign army by agreement between states should be distinguished from mercenaries. Volunteers are not mercenaries, provided they are included in the personnel of the armed forces of the belligerent party (according to the V Hague Convention of 1907 “On the Rights and Obligations of Neutral Powers and Persons in a Land War”).

The subject of a crime from the point of view of Russian legislation is a person who has reached 16 years of age. The subjective side is characterized by direct intent. The person is aware that he is committing criminal acts and desires it.

Although all history textbooks say that an army consisting of mercenaries is worse than an army of selfless, patriotic citizens, at all times states still resorted to the services of “soldiers of fortune”, “wild geese” or “dogs of war”, as they are sometimes called mercenaries.

It all started back in Ancient Greece.

Rich Greek slave owner of the 4th-3rd centuries BC. e. he was pampered, cowardly, and did not want to go into battle. Physical Culture for him it became only fun, entertainment. At sports games, he preferred to be a spectator rather than a participant. Physical education is no longer given the same attention. As a result of continuous wars, the demand for mercenaries increased and their number increased. The militia army was gradually replaced by professional mercenary soldiers.

The way out of this situation was the formation of light and medium infantry from mercenaries. The Greeks already had extensive experience serving as mercenaries of eastern despotisms (Egypt, Persia, etc.). The contingents for this purpose were free farmers and artisans, devastated by wars and debt bondage. Payment for service gave them the opportunity to purchase weapons, equipment and food.

The next period of widespread use of military mercenaries occurred in the late Middle Ages in Europe.

Traditional military organization The feudal-knightly militia was losing effectiveness. It turned out to be impossible to organize a standing army in conditions of an undeveloped economy and state apparatus.

In the XIV century. The first type of mercenaryism is formed, conditionally, the “lowest” one. The main feature of the lower type was the preservation of the feudal-knightly structure by the army in the presence of indefinite hiring. The first variant of this type of mercenaryism is the condottiere variant. Relatively small, mostly cavalry detachments, fully provided by the condottiere, were hired to states that needed troops. The guarantee of fulfillment of obligations was only a personal agreement with their leader, who, being independent, often pursuing his political goals, violated it, sometimes seizing state power.

A more profitable option for the employer was the so-called captain's (typical for England and France). The military commander-captain could be appointed directly by the king and was subject to some control. But gradually (in France) the positions of captains were seized by the nobility who defended separatist aspirations. This type of mercenary work often did not serve the interests of the centralized state. In addition, the revolution in military affairs required fundamental changes: first of all, an increase in the role of the infantry, and therefore a significant increase in the army, which the condottieri were not able to provide. During this period, a new, “higher” type of mercenaryism appeared, characterized by the presence of troops built on new structural principles with temporary hiring. There are two main approaches to organizing hiring: the Swiss “state” option and the German “contractor” option. However, the common features of both options were mass participation and a greater connection with the state than before.

In German mercenaryism, this connection was expressed: firstly, in the financial dependence of both the commander and the troops on revenues from the treasury; secondly, in legal dependence on state power. Thus, recruitment required the permission of the monarch, to whom all Landsknechts swore allegiance, without exception; a kind of military justice also had a state origin.

In the XVI - XVII centuries. there was no alternative to mercenaries. It fully complied with the basic requirements for the armed forces:

1) the nature and scale of wars, which grew significantly during that period;

2) the interests of the absolute monarchy at this stage, because the military leaders dependent on it, usually capable of only recruiting at their own expense, but not constantly maintaining an army, as a rule, did not encroach on political power. This was facilitated by their, often humble or foreign origin, separation from the restless community of imperial officials. Landsknechts served only those who paid them, having no other requirements than timely payment;

3) mercenaries, in contrast to the feudal militia, were fully provided with the necessary personnel, mainly representatives knocked out from their usual environment by the decomposition of the traditional economic structure

In the 14th and 15th centuries, Italy, like Africa today, was flooded with out-of-work veterans." great war"After the end of the Hundred Years' War, these were British troops, and in the twentieth century - veterans of the Second World War, and then the wars in Korea, Vietnam, etc. (the latest example is the participation of Serbian mercenaries in the war in Zaire).

As now, in those days mercenaries tried to spare each other in battle. Machiavelli describes a case when, in a battle that lasted a whole day, one man died, and even then by falling from his horse. Today, mercenaries also try not to shed their blood unnecessarily. This is how the rule was born that the “dogs of war” themselves try, if possible, not to take part in hostilities, limiting themselves to the role of instructors or, in extreme cases, officers directing the actions of local soldiers on the battlefield.

Victory of a mercenary over a legionnaire

This STARTED a long time ago. On the one hand, there have always been, are and will be people who wield weapons better than others and are ready to use them. Some are attracted by battle, danger, adrenaline, others by the desire to kill and rob. On the other hand, sometimes life itself forces a person to take up arms for money. Probably, in the end, a mercenary is worse than a warrior-defender of his homeland, but at all times there has been a demand for “soldiers of fortune,” “wild geese” or “dogs of war,” as mercenaries are also called. The first known case of their use was noted 3600 years ago. Army ancient egypt half consisted of hired foreigners; the Carthaginians and Persians had them; In the Battle of Gaugamela, 9,000 mercenary Greeks fought for Alexander the Great. In the 3rd century. BC e. The “Agreement with Hired Warriors” of the Pergamon king Eumenes I very clearly stated the terms of employment: pay, 2-month rest after 10 months of service, pension for orphans in the event of the death of a warrior-father; Those who served the contractual term (or to their relatives, or “to whom the warrior leaves”) were assigned a tax-free pension and duty-free removal of property from the country.

And then the Roman Empire entered the historical arena and brought things to the point of absurdity.

For many centuries, its army was one of the strongest in the world, maintaining combat effectiveness despite all the upheavals of the state. What was the secret of her superiority? Initially, it was staffed only by Roman citizens. The expansion of the empire, constant wars required more and more soldiers, the presence of approximately 50 legions (350,000 people) is documented. Roman legionaries were superior to any enemy thanks to the advantages of a standing army: strict discipline, regular excellent training, and tactical skill. But the needs exceeded the available human resources - and foreign mercenaries began to be recruited into the troops, initially to guard the borders. And then each legion was given several auxiliary cohorts of non-Romans (Cretian archers, Balearic slingers, etc.), who received only a third of the legionnaire’s salary. Romans from the guard were appointed as centurions, the command language was Latin, and in everyday life they spoke their own language. These cohorts were a transition to cavalry and infantry recruited exclusively from barbarians. Initially, each legion had 300 horsemen on staff - and then the Roman cavalry was replaced by Germans, Iberians, and Numidians; the number of riders increased to 800; Thus, in Caesar's army there were 5,000 hired horse Gauls. For the dominance of the Latin spirit, the legion was recruited in such a way that the legionnaires were in the majority; they, as a core, were always placed in the center, and the auxiliary parts were split into small groups, not united with each other.

But the great conquests were a thing of the past, the army was bored in remote provinces, occasionally participating in palace coups. There were only enough purebred Romans to fill the Praetorian Guard (12,000 people); a military career became unprestigious for people who preferred to be officials. And the pampered population had no desire to serve; they indulged in all conceivable and unimaginable pleasures.

A well-fed life beyond one's means, having hit the economy of Rome, had a heavy impact on the army. At the beginning of the 3rd century. n. e. full-fledged money disappeared - and the legionnaires were given rations, to increase their allowances they were allowed to have their own fields and farms, where they “plowed” instead of serving. The warrior who lived in the barracks and sent money to his family began to live at home, appearing only for classes; the war professional became a slack military settler with negligible combat value. He weakened, but the foreign mercenary grew stronger. The superiority of the aggressive barbarians with their semi-savage energy quickly became apparent: auxiliary cohorts became the core of the army (with better pay), and the legions became second class. The word “barbarian” became a synonym for warrior; the more of them there were in a unit, the more combat-ready it was. The Romans were also forced out from the command level, and the Germans began to gain an advantage.

They deserve special mention. These warlike tribes, having succumbed to the power of Rome, then took and destroyed 3 legions in the famous battle in the Teutoburg Forest (9 AD), which attracted the attention of the Roman “General Staff”, who began to recruit them as mercenaries. From the 3rd century, their mass migration to the empire began with the rights of federates; Economically bankrupt Rome no longer bought individual warriors, but a leader who fielded an agreed upon number of fighters. The Germans came to the empire as mercenaries, while maintaining the tribal system, moving with all their belongings and household members; The “Great Migration” was, in essence, the entry into Roman service of entire Germanic tribes. Over the course of three centuries, Rome lost the territory of what is now Western Europe due to the settlement of Germans there, who were either hired by the Romans or fought against them. The emperors, relying on strangers connected with them only by money, weakened more and more; in the struggle for the throne, the one who had more mercenaries won. To disguise his dependence on them, Emperor Probus scattered 16,000 Germans throughout all the legions, and they already imitated them, changing tactics, weapons, etc.

The German mercenary was a formidable force for centuries, but lacked the organization to seize power. Now she was. Tribes of strangers put an end to power that did not rely on national military force: the Germans captured Gaul, Italy, Spain and Africa, declaring themselves the kingdoms of the West and Ostrogoths, Burgundians, Franks, Vandals... And then they defeated the empire itself. Mighty Rome fell. The well-fed Romans played out the game, became dependent on the despicable barbarians and were ultimately destroyed by them. But the Roman soldier was not defeated by the mercenary - he was replaced by him. Does this remind you of anything that is happening in our time?

Varangians: migrant workers of the sword and ax

The “Dogs of War” left a very clear mark on history: on August 23, 476, Odoacer overthrew the leader of the German mercenaries in Rome last emperor Romulus Augustus and proclaimed himself king of Italy. This day is considered the end of antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages. And again, mercenaries were a tool for waging war and pacifying civil strife. Foreign squads of bodyguards are known almost everywhere: the Varangians of the Kyiv princes, the Scandinavian Huskerls in England, the Russians in the service of the German emperors. Slavic warriors were especially valued as guards for the Muslim rulers of Turkey, Syria, Egypt, and Arab Sicily, over time forming a privileged military nobility - the Janissaries and Mamluks, on whom the power of the sultans rested. Sakaliba - Slavs who fought for the Cordoba Caliphate in Islamic Spain, after the collapse of the Caliphate rose to become the legitimate rulers of Muslim principalities.

There were a lot of “knights out of work”, as well as interested clients. In 1028, Naples hired the Norman Rannulf for the war with Lombardy, and the Lombards were served by the Norman William Ironside, who later fought in Sicily for the Byzantines. The Italian Normans themselves used Muslim troops in their feuds, the Pope used Swabian regiments, and the Arab emirs hired Spanish knights. Very different people, served under different conditions: they were united by one thing - MONEY! It must be said that the attitude towards the mercenaries was bad even among those whom they protected. In all centuries, “dogs of war” were perceived as significantly worse than their warriors.

Mercenaries were also needed Ancient Rus': a large territory, dangerous neighbors, a war sometimes on several fronts at once required significant forces, primarily professional warriors. Sometimes this need was satisfied at the expense of foreigners, most often Scandinavians. Chronicles mention their use by princes Oleg, Igor and Vladimir in campaigns against Constantinople (907, 944 and 1043). Icelandic sagas report: “King Yaritsleif (Yaroslav) had many Norwegians and Swedes.” Here are the names of some: Eimund with a detachment of 600 people, expelled from Scandinavia, as well as Yakun, whose Varangians fought for the prince against Mstislav of Tmutarakan in 1024.

The history of the Crusades is interesting. Byzantium asked the West for troops to protect the Christian world from infidels; attracted to the service by an agreement between sovereigns, luring them through recruiters during the era of the crusading movement, which embraced the masses of men who knew how and wanted to fight. But the defenders were money-hungry mercenaries; The insolent behavior of the knights caused a shock in Constantinople: although they took the oath, they acted exclusively for their own personal purposes.

Among the Catholic crusaders who hated the Orthodox Byzantines, there was one community that sought to get to Byzantium and stay there quite legally, with the sanction of its kings. We are talking about the Scandinavian Varangians (varings, vaeringjar) - their goal was military recruitment in Byzantium. Some separated with their ships from the crusading fleet immediately after passing Gibraltar and went straight to Byzantium, others briefly fought in Palestine and were hired after that.

Why did they choose this particular method of “pilgrimage”? This was the mentality: they saw any journey as a way to both enrich themselves and demonstrate their prowess. The emergence of kingdoms in Scandinavia released a lot of daredevils who went to the edge of the world they knew for fame and money. Open marriages increased their mobility; many knights from other countries went on campaigns with their wives, but here everyone was fundamentally independent. Obviously, there was nothing unusual in the Scandinavian decision to use their king's crusade for recruitment. Now they lead the mercenary force of Europe, Crusades came in very handy, and the means of communication of the peoples of that time reported on demand and earnings. The targets of the “soldiers of fortune” were Rus', the Caucasus, Khazaria, Bulgaria, but above all the rich Byzantium, where there were many enemies and gold, and therefore a chance to become famous for good pay; they called it “crushing gold” (“gulli skifa”).

Many went to Byzantine service through Rus', where their troops were replenished with Russians and finally formed. Rus' has long been the main corridor for the Scandinavians; The conveyor belt worked smoothly, providing both the prince with hired force and its export to Byzantium. And the client was also satisfied: the local recruit was dependent on the family, the clan, and the foreign warriors were dependent only on the one who paid them money, on the emperor. A person who has received gifts and is unable to repay in equal measure is obliged to be faithful to the donor - such was the mentality of the northerners at that time. That is why these rude people, whom the Greeks did not like, were exclusively loyal to the one who hired them. It is clear that the Scandinavian crusaders and other mercenaries in the Byzantine army, having become part of the elite who were lucky enough to “break gold in Grickland,” were no longer too keen to return home. Their property rights in Greece were legally secured from the first years of their presence in the Byzantine army, when they came there under the guise of Russians along with the Kyivians.

The Germans, whom the Greeks called the Slavic word “Germans”, were also seen on the walls of Constantinople, but they did not compete: there was always a corps of warings in the city, and according to the texts Scandinavian sagas it is clear that about half of them did not intend to return to the North.

The Swiss: atrocities as a sign of quality work

Firearms reduced the knights to nothing, but there was already a new force that instilled fear in the Europeans - the Swiss mercenary infantry. Her strict discipline, tactical cohesion and irresistible square column strike quickly showed “who’s boss.” Now the Swiss are perceived as peaceful, “white and fluffy.” And initially they were warlike mountain people. Living in communities among the harsh mountains instilled in them fighting qualities: the courage of every fighter, a strong bond of military camaraderie, a penchant for murder and robbery. They have been practicing mercenaries for a long time; bored in their mountains, they were sold to foreign powers for war. The first deal took place in 1373: the Duke of Milan bought 3,000 mercenaries, who fought so bloodily in Italy that they aroused the indignation of Pope Gregory XI. The Diet of Bern forbade its members to fight abroad, but they ignored this and sold themselves to one or the other, depending only on who paid the most. They were often sold to both warring sides, and then they had to exterminate each other in battle. Thus, 2,000 soldiers were sold to King Charles V and the Pope, and 16,000 soldiers were sold to their French enemies.

Thinking only about profit, before each battle they swore an oath that they would plunder no earlier than the job was finished. One of the reasons for their continuous victories was the insane horror that they inspired in the Europeans with their cruelty. The fact is that Switzerland was inhabited by only half a million people, and the harsh nature very poorly rewarded their hard work. To keep 5% of the population under arms required an enormous amount of effort, unthinkable for a long time. The Swiss strategy of extermination is explained very simply: men capable of carrying weapons left their fields only for a short time and were forced to do the bloody work for which they were hired as quickly and thoroughly as possible. It was not enough to disperse the enemy; it was necessary to deprive him of the opportunity to gather again: the only sure way for this was death. And the mercenaries were strictly forbidden to take prisoners; all those who fell into their hands were destroyed. The Bernese were especially famous for their bloodiness: after the storming of the city, they had to be immediately removed from it, because they killed everything that moved. Machiavelli derived his principle of combat from the Swiss strategy of destruction. The microscopic country struck fear into all its neighbors.

They suffered defeat from a direction they did not expect: their military power distributed the money. Greed gave rise to reckless courage, ready for a price for any assault, regardless of where and when it is carried out. Discipline collapsed, as the mercenaries rebelled if payment was delayed, and this happened often in the then lack of money; if the campaign dragged on, they simply ran home. Finally, disputes over money (some received 10 times more than others) brought discord within their own ranks. And the Europeans sought to get rid of them by creating their own troops, and it was not only the decline of Swiss military prowess that prompted them to do this. If the Swiss were sold to someone (and they changed buyers every year), then the others could not remain defenseless. French, German, and Spanish infantry appeared, following the example of the Swiss. They, serving everyone, were teachers everywhere and themselves dug the grave of their monopoly. The fastest to catch up with them were the German landsknechts, who defeated their teachers in the battle of Milan in 1522. It was a defeat not due to any chance, courage or great numbers of the enemy, but due to the complete paralysis of the core of the invincible strength of the Swiss: discipline.

Landsknechts: war as business

The Germans returned to the European mercenary market. “Servants of their country” also preferred to fight for money under foreign banners. If Swiss mercenaryism was state-owned (the canton sold its soldiers), then German mercenaryism was private enterprise. Recruited only for the duration of the war, it was, in fact, a European form of business: the monarch gave a contract to recruit troops to the general, who gave a contract to the colonels, and the colonel to the captains who recruited soldiers. And at all levels of relations, Their Majesty Money played a decisive role. There was no alternative to the mercenary army; it fully met the requirements of that era. Impoverished Europe was full of “superfluous” people for whom there were only two options: famine or war. There were also many wars, and the soldier served whoever paid, subordinate only to his direct commander (captain), a lowly one, not claiming the throne, appointed by the king himself, so everyone had their own benefit.