Vodka “Russian Squadron” attracts consumers not so much with the quality of a good classic drink, but with original design solutions. Each bottle is a kind of “kinder surprise”, only with a toy for adult men. At the bottom of the vessel there is a miniature, skillfully made of silver highest quality model of a deep-sea mine, military aircraft, T-34 tank or cruiser. So vodka fans get not only their favorite drink, but also a souvenir. It is not surprising that many of them collect collections. The model is clearly visible through transparent glass, so when purchasing you can select the missing collectible item. The exclusive design is also emphasized by pictures of military battles on the label - in the air, at sea or on land.

About the manufacturer

Vodka company "Standard" was founded in 2003 in Nizhny Novgorod. Status - limited liability company. The total production capacity is one and a half million deciliters per year.

General Director Sergey Verkhovodov main reason considers the success of the enterprise high level product quality, which can be achieved thanks to our own laboratory, imported equipment, and fully automated bottling lines.

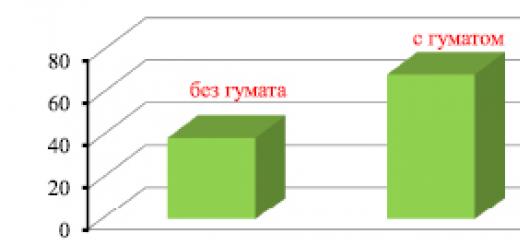

Vodka is produced according to classical canons, but polishing filtration is used - a multi-stage purification system with charcoal and silver.

The product is not bottled immediately: first, the vodka “rests” in a dimly lit basement for about two weeks. According to company experts, such aging improves the organoleptic properties of the drink and softens the taste.

The company has a team of six professional tasters who check products according to all indicators.

LLC "Standard" produces exclusive brands - with an individual logo and author's design. The design is coordinated with the consumer and created specifically for an anniversary, corporate event, wedding or other celebration.

The company's products are exported to China, South Korea, Vietnam, Ethiopia.

The design provides a multi-level level of protection against counterfeiting and counterfeiting: an original bottle in the shape of a lighthouse, a tamper-evident cap, a stylish holographic label, and a sticker with a code.

“The creation of the military-patriotic line “Russian Squadron” was a tribute to the heroism of the Russian military - pilots, sailors, tank crews. This is our symbol of admiration for military power Russia,” says the General Director of the enterprise.

The Russian Squadron brand received gold at the ProdExpo competition in Moscow in 2014, and in 2016 received the ProdExpo Star award.

Types of vodka “Russian Squadron”

“Russian Squadron” consists of three types: limited edition, GOLD and PREMIUM. The drinks do not differ in preparation technology, taste and olfactory characteristics. The only differences are in the design: limited edition - with weapon models, “Gold” - gold on the label and a deep-sea mine at the bottom, “Premium” - a deep-sea mine behind tinted bottle glass.

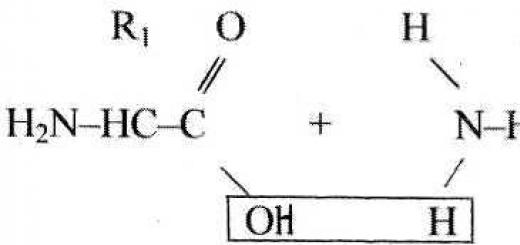

The main component of the drinks is luxury alcohol, water purified using charcoal, silver and nanofilters, and sprouted wheat flake extract. The subtle and light aroma is reminiscent of the smell of freshly baked bread. The full, velvety flavor has a slightly spicy, grainy undertone. Vodka is served chilled to 8-10 °C with traditional Russian dishes - pancakes with caviar, boiled pork, jellied meat, homemade pickles, pickled mushrooms. The drink enhances the taste and aroma of meat snacks, is combined with salted and smoked fish, and is used by bartenders in cocktails.

There are more than 30 brands of vodka on the Russian market. The range of strong alcoholic drinks is growing every year.

Russian Squadron vodka appeared on the market more than 10 years ago and quickly gained popularity among consumers (see also:).

The limited liability company “Standard” is engaged in the production of products. The company, led by Sergei Verkhovodov, was founded in 2003 in Nizhny Novgorod. Success in the alcohol products market ensures high quality products.

The result is due to the company having its own laboratory, modern equipment, and a fully automated production process. The technology includes a multi-stage cleaning system using charcoal and silver. The resulting product is aged for two weeks to improve taste.

The quality of vodka is checked by a staff of six specialists.

The company pays special attention appearance product. For each festive event, an individually designed bottle with the brand logo is created. In order to reduce the risk of creating counterfeits, each original copy of an alcoholic drink has a number of distinctive qualities:

- the shape of the bottle is a lighthouse;

- cap with dispenser and tamper controller;

- label with holographic image.

The company's products are represented on the Russian, Chinese, Korean, Ethiopian and Vietnamese alcohol markets. Confirmation of the quality of Russian Squadron vodka was first place at the Moscow ProdExpo competition in 2014 and the “ProdExpo Star” award.

Company assortment

All products are similar in composition - corrected drinking water, sugar syrup, Alfa alcohol, wheat infusion. The main difference factor was the design.

Customers are offered three types of Russian Squadron vodka:

- Limited edition. In the bottle the buyer will find a model of military weapons - a silver tank, an airplane, a submarine. The etiquette is designed accordingly - with a scene of tank battles, a water world and submarines, the sky and a soaring plane from the times of the Great Patriotic War.

- Gold. The label has a golden color; the contents of the bottle are complemented by a small figurine of a mine at the bottom.

- Premium The bottle is made of tinted glass, inside there is a model of a deep-sea mine.

The product is an original gift for special occasions - an anniversary or February 23rd. You can purchase the product with or without a leather case.

The manufacturer recommends serving the strong alcoholic drink chilled at a temperature of 7-9 degrees. Hot dishes, seafood, pickles, pancakes with boiled pork or caviar are suitable as appetizers. The choice depends on the taste preferences of the consumer.

Usage options

Vodka "Russian Squadron" is suitable for independent consumption and as a base for cocktails. The list of popular vodka-based alcoholic drinks includes:

- Cocktail " Russo-Japanese War» . The drink from bartender Alexander Kan is available for preparation at home. The bright drink contains 20 ml of Russian Squadron vodka and Japanese Midori liqueur, a drop of lemon juice and a cocktail cherry. To serve, use a tall stack. According to the author, the cocktail should symbolize the friendship of peoples.

- Cocktail “Voroshilov shooter”. The composition includes 15 ml of vodka and blueberry liqueur, 40 g. lemon juice and blueberries for decoration.

- Bloody Mary. A simple cocktail originally from the USA is widely known throughout the world. The author was bartender F. Putiot. The classic recipe includes tomato juice, vodka, lemon juice, Tobasco sauce, spices - salt, pepper and a sprig of celery. The ingredients of the drink vary depending on the place of preparation and the taste preferences of the consumer.

The number of vodka-based cocktails exceeds a hundred. The list includes alcoholic drinks of varying degrees of strength and volume - Shot drinks and Long Drinks.

Price

Not every alcohol supermarket offers the purchase of Russian Squadron products. The manufacturer states that in 2017, demand for the product exceeded supply. Many online stores offer products to choose from.

The price of the product depends on the volume, type and availability of gift packaging. The minimum cost for a strong alcoholic drink with a volume of 0.5 ml was 540 rubles. A product with a volume of 0.7 ml in a paper tube package costs from 1,200 rubles.

Water "Russian Squadron" is a high-quality product of domestic production. Original design solution made the product suitable as an occasion gift.

Evacuation of Crimea in 1920

On November 10, 1920, an order was issued to the fleet for the evacuation of Crimea, which ended the retreat of the Volunteer Army. Over the course of three days, 126 ships loaded troops, families of officers, and part of the civilian population of the Crimean ports of Sevastopol, Yalta, Feodosia and Kerch. 150 thousand people went into voluntary exile.

Of all the ships, only two did not reach Turkey. The destroyer "Zhivoy" sank in the depths of the Black Sea. Another loss was the boat Jason, which was towing the steamer Elpidifor. At night, the team, numbering 10-15 people, cut off the towing cables and returned to Sevastopol.

Organization of the Russian squadron

On November 21, 1920, the fleet was reorganized into the Russian squadron, consisting of four detachments. Rear Admiral Kedrov was appointed its commander, who was awarded the rank of vice admiral.

On December 1, 1920, the French Council of Ministers agreed to send the Russian squadron to the city of Bizerte in Tunisia.

Transition of the Russian squadron to Bizerte

As soon as Bizerte was designated by the French government as the final base, the ships put to sea. The squadron did not belong to any of the states and was under the patronage of France, sailing under the escort of French ships. St. Andrew's banners flew astern, but French flags were raised on the mainmasts. The transition took place at the most inclement time of the year.

At the end of 1920, having rounded the Peloponnese peninsula, one after another, Russian ships dropped anchor in the Tunisian port of Bizerte. On December 23, 1920, the passenger steamer Grand Duke Constantine was the first to enter the port of Bizerte. On board, in addition to the crew, there were many civilians, among whom was the historian Nikolai Knorring. The Russian squadron arrived in Bizerte with its ship churches and naval clergy. The squadron included 13 Orthodox priests. The Orthodox flock was proud of their spiritual mentors. The most famous was Archpriest Georgy (Spassky).

By mid-February 1921, the entire squadron arrived in the Tunisian port of Bizerte - 33 ships, including two battleships General Alekseev and Georgy Pobedonosets, the cruiser General Kornilov, the auxiliary cruiser Almaz, 10 destroyers, 3 submarines and more 14 ships of smaller displacement, as well as the hull of the unfinished tanker "Baku". There were about 5,400 refugees on the ships.

The arrival of the flagship old three-tube cruiser "General Kornilov" (formerly "Kahul", and even earlier - "Ochakov"), from which Lieutenant Schmidt led the Sevastopol revolutionary uprising back in 1905 and which carried a large combat load throughout the First World War, was especially solemnly celebrated. wars: hunted for German cruisers"Goeben" and "Breslau", shelled the Turkish coast, went on reconnaissance missions, covered mine laying and laid minefields himself, sank Turkish merchant ships.). The squadron commander, Admiral Kedrov, and his staff stood on the bridge of the cruiser and greeted every Russian ship already in the port. The headquarters of General Wrangel was located on the same ship.

The flagship of the squadron, the battleship General Alekseev, was one of the most modern ships of that time, the light cruiser Almaz was one of the first aircraft-carrying ships of the Russian fleet with a “flying boat” on board. Russian submarines of the latest designs arrived in Bizerte... There was also the Yakut transport, which came to Crimea from Vladivostok just before the evacuation. On it, cadets and midshipmen of the Naval Corps were evacuated to Bizerte. However, most of all the destroyers of the Novik type came to the port of Bizerte; this was the most modern class of ships. The destroyers "Bespokoiny", "Gnevny", "Daring", "Ardent", "Pospeshny" were the first serial turbine destroyers in the Russian fleet. These ships compensated for the lack of modern cruisers on the Black Sea. During the First World War, they actively participated in hostilities, were used in trade communications, and were engaged in mine laying on the coasts of Turkey. These destroyers have over 30 Turkish sailing ships, 5 transports, and a tugboat.

Many considered the Kronstadt transport workshop to be the most modern ship of the squadron. During the First World War, it competed in ship repairs with the Sevastopol port. In Bizerte he subsequently employed hundreds of skilled sailors.

But there were also “old galoshes”, such as the battleship “George the Victorious”, retrained into a battleship, which later became a floating hotel for Russian families. At first, Orthodox church services were held on its specially equipped deck.

Reduction of the composition of the Russian squadron and decommissioning in 1922

The composition of the refugee contingent consisted half of peasants, Cossacks and workers. The remaining half are young people (secondary students educational institutions and students), naval officers and persons of intelligent professions - doctors, lawyers, priests, officials and others.

The arriving Russians were supplied with food from warehouses French army. Some of the supplies were provided through the efforts of the American and French Red Cross. Over time, the number of rations and their sizes began to decline, and the assortment began to deteriorate.

The reduction hit the personnel of the squadron. It also had to be reduced. By January 1922 - up to 1500, and by the summer of the same year - up to 500 people. This meant transferring many sailors ashore and deteriorating supplies for officer families.

In October 1922, the naval prefect of Bizerte received orders to reduce the personnel of the Russian squadron to 200 people. It was tantamount to liquidation. Negotiations began, lasting several days, which ended with 348 people being allowed to remain. The commander had to agree, although he did not lose hope of increasing this number by petitioning through Paris. November 7th was scheduled for decommissioning, and the naval prefect insisted on this measure being carried out as soon as possible.

The decommissioning resulted in a housing shortage. This problem soon became more acute. Then the former battleship “George the Victorious” was quickly converted into a floating hostel, where family sailors were accommodated. As participants in the events recall, naval wits immediately dubbed the battleship “babanoser.” The rest were placed in camps set up near Bizerte and intended from the very beginning for civilian refugees.

The sailors who remained on the ships continued to carry out their, now doubly difficult, service. It was necessary to maintain weapons, mechanisms, and vehicles in order. Often officers had to do this, because there were not enough sailors. It was necessary to conduct combat training exercises and carry out routine and dock repairs.

The sailors in Bizerte were paid a symbolic salary. The salary ranged from 10 francs for an ordinary sailor, to 21 francs for a ship commander with the rank of captain of the 1st rank. From the sources of those years we learn: “The French Maritime Department issued to all members of the Squadron and Corps two sets of working canvas dresses and a pair of boots, which was a significant help to the cloth for an outer suit received in December 1920, upon arrival in Bizerte, linen, as well as American boots.” The Russian squadron managed to provide fairly high medical care not only for its colony, but also for the local population. Until the fall of 1922, there was an operating room at the Dobycha sea transport. To help those who were sick and temporarily unable to work, a health insurance fund was created.

Destruction of ships of the Russian squadron

Meanwhile, the attitude of the French authorities towards the squadron, its crews and commanders worsened. Not content with the reduction of personnel and the abolition of midshipman companies, they also took on the ships.

The French started with small ships. To make up for the recent losses of their fleet in the world war, back in July 1921 they took away from Bizerte the most modern ship of the squadron - the transport workshop "Kronstadt", giving it the name "Vulcan". During the First World War, it competed in ship repairs with the Sevastopol port. Here in Bizerte he provided employment to hundreds of skilled sailors. The icebreaker Ilya Muromets became the French minelayer Pollux. The Maritime Ministry also acquired the unfinished tanker Baku.

The fleet of the French Ministry of Merchant Shipping was replenished by 12 units. The Italian shipowners got the transports “Don” and “Dobycha”, the Maltese got the messenger ship “Yakut”. At the end of December 1924, a Soviet technical commission headed by the famous shipbuilder Academician Krylov arrived in Bizerte. After a thorough inspection of the squadron, the commission compiled a list of ships that were to be transferred to the USSR. It included the battleship General Alekseev, six destroyers, and four submarines. Since not all ships were in technically satisfactory condition, the commission demanded that the necessary repair work be carried out. France rejected these demands. Then Italy offered its services.

However, Moscow did not wait for the delivery of the promised ships. In Western Europe, a wave of protests arose against the implementation of the Franco-Soviet agreement to the extent of the transfer of the squadron. Most states feared that this would lead to excessive intensification of the Soviet foreign policy. The governments of the Black Sea and Baltic countries were especially alarmed. England also agreed with them.

A heated debate took place in the League of Nations. And in France itself, primarily in the Senate and colonial circles, they started talking loudly about the Soviet threat to French overseas possessions and sea communications. On behalf of Russian emigration Baron Wrangel made a sharp protest.

The campaign hostile to the Soviets had done its job. France avoided fulfilling the agreement on the fleet. The ships of the squadron remained in Bizerte, but their fate was unenviable. Deprived of the necessary daily care and over the years of major repairs, the ships, despite attempts to preserve the mechanisms, deteriorated and lost their seaworthiness and combat qualities. The French managed to sell some of them to one country or another. Others were doomed to be dismantled and sold for scrap. In both cases, the crews removed the ship's guns, disconnected the locks to them, and then dumped both of them into the sea.

In fact, most of the Russian ships were left to their fate. Two, three, four a year they were sold for scrap. Following this, the ships were sold for scrap. The agony of the Russian squadron, still stationed in the roadstead, began. This agony lasted for more than 11 years, while the ships were slowly dismantled piece by piece. Guns, mechanisms, copper and cabin trim were removed. Then the buildings themselves were dismantled. The last to go to the chopping block was the battleship General Alekseev. His quartering also began. But the giant’s agony lasted a long time: the army of hammermen did not soon cope with his mighty corps, and the sound of heavy hammers reverberated for a long time in the hearts of the sailors.

From “Russian Carthage” with love

For several years, a fragment of the Russian state lived in Tunisia in the form of a squadron of Black Sea ships that left Sevastopol at the end of 1920. The writer Saint-Exupéry called the colony of our compatriots in Bizerte (it was there that rogue ships and sailors with their families settled for many years) “Russian Carthage.” Today, only one person remains from the “Russian Carthage” - the daughter of the commander of the destroyer “Zharkiy” Anastasia Aleksandrovna Shirinskaya-Manshtein. She turns 95 this September. Writer Nikolai Cherkashin visited her.

Captain's daughter

"Madame Russian Squadron". This is not a beauty pageant title. This is the lifelong position of Anastasia Alexandrovna Shirinskaya, whose house in the Tunisian port of Bizerte is known to every passerby.

Once upon a time there was a girl. Her name was Nastya. Her dad was a captain, or rather, a ship commander in the Baltic Fleet. The girl rarely saw him, because she lived with her grandmother near Lisichansk in a small manor house with white columns. There was everything that makes childhood happy: grandmother, mother, friends, forest, river...

#comm#This fairy tale was cut short by the revolution, October revolution And Civil War. Then there was a flight to the south, to the Crimea, to Sevastopol, where by that time my father - senior lieutenant Alexander Sergeevich Manstein - commanded the destroyer "Zharky". #/comm#

On it, in November 1920, he took his family along with other refugees to Constantinople. And from there, 8-year-old Nastya, along with her sisters and mother, crossed the Mediterranean Sea to Bizerte on the overcrowded ship "Prince Konstantin". The father, as was initially believed, perished with his destroyer in a stormy sea. Fortunately, “Roast”, rather battered, nevertheless arrived in Bizerte after Christmas.

For several years, the old cruiser "George the Victorious" became their home. Until now, in the childhood memory of Anastasia Alexandrovna’s younger sister, Anna, “ native home"is depicted as an endless row of doors in a ship's corridor. Nastya was lucky: for her, her “home” is white columns among the same white birches... Longing for that forever-abandoned home, she came to Cape Blanc Cap, the White Cape , which, as the adults told her, is the northernmost tip of Africa, and therefore is closest to Russia from there, and shouted into the sea: “I love you, Russia!” And the most amazing thing is that her compatriots heard her! But more on that a little later. ..

"Russian Principality" in Africa

The sailors, Cossacks, and the remnants of the White Russian army did not escape from Crimea in November 1920, but retreated, went, as their grandfathers said, into retreat, with marching headquarters, with banners, banners and weapons. The French, yesterday's allies German war, gave Wrangel's Black Sea squadron shelter in their colonial base - Bizerte. A fragment of Russia stuck into North Africa and melted there for a long time, like an iceberg in the desert. Year after year, services were held on Sevastopol ships, St. Andrew's flags were raised and lowered at sunset, holidays of the disappeared state were celebrated, in the Alexander Nevsky Church, built by Russian sailors, the dead were buried and the Resurrection of Christ was glorified, plays were performed in the theater created by officers and their wives Gogol and Chekhov, in the naval school, evacuated from Sevastopol and located in the fort of the French fortress, young men in white uniforms studied navigation and astronomy, theoretical mechanics and the history of Russia...

Local chronicler Nestor Monastyrev published the magazine "Sea Collection". The editorial office and the hectograph machine were located in the compartments of the submarine "Duck". Nowadays, several copies of this ultra-rare publication are kept in main library countries...

As another naval recorder of Bizerte, Captain 1st Rank Vladimir Berg, noted in his book “The Last Midshipmen,” the Sevastopol people in Bizerte “made up a small independent Russian principality, controlled by its head, Vice Admiral Gerasimov, who held all power in his hands. To punish and pardon, to accept and expel from the principality was entirely in his power. And he's like old prince ancient Russian principality, ruled it wisely and powerfully, inflicting justice and reprisals, scattering favors and favors."

#comm#The squadron ceased to exist as a combat unit after France recognized the USSR. On the night of October 29, 1924, at sunset, St. Andrew's flags were lowered on Russian ships. Then it seemed forever. But it turned out - for the time being...#/comm#

Seven months later - on May 6, 1925 - in the midshipman camp Sfayat, the ship's bugle sounded the signal "Disperse!" They separated, but did not scatter, did not run away, did not disappear, did not forget who they were and where they came from. They wrote books, built a church, and minted a commemorative pectoral cross. In a word, they showed the world a feat of loyalty to the Flag, the oath, and the Fatherland. The USSR knew nothing about this. More precisely, they didn’t want to know...

In the Arab part of the city there was a Russian House, where sailors and their wives gathered. The officers came in immaculately white, ironed jackets, even with patches neatly applied by women's hands.

The Arabs knew that the Russians, despite their gold shoulder straps, were as poor as themselves. - Shirinskaya says. - This caused the natives to involuntarily warm up to the alien exiles. We were poor among the poor. But we were free! Do you understand? I say this without any pathos. After all, we, in fact, did not experience the fear that devoured our compatriots at night in our homeland. They, not us, were afraid that they would enter your house at night, rummage through your things, and take you to God knows where. We could talk about anything without fear of prying ears or denunciations to the secret police. We didn’t have to hide the icons - this is in a Muslim country, mind you. We were not starved for political purposes. I only learned the word “Gulag” from Solzhenitsyn’s books.

We were poor, sometimes destitute. My father made kayaks and furniture. Admiral Behrens, the hero of "Varyag", in his old age sewed handbags from scraps of leather. But no one commanded our thoughts. It is a great blessing to think and pray freely.

I will never forget the horror with which one Soviet citizen climbed out of my window when an employee of the Soviet embassy rang the doorbell. This was in 1983, and my guest was afraid of losing his visa if someone said that he was communicating with a white emigrant.

"I love you, Russia!"

In the fall of 1976, the submarine on which I served entered the military harbor of Bizerte. I looked around to see if I could see the submerged hull of a Russian destroyer somewhere, or if I could glimpse the rusty mast of a fellow ship. But the surface of Lake Bizerte was deserted, except for three buoys that protected the “area of underwater obstacles,” as it was written on the map. Neither the navigation guide nor the map specified what these obstacles were, so we could only assume that it was there, not far from the soil dump, that the iron remains of Russian ships rested in the bottom silt of the salt lake.

The Tunisians placed our floating base "Fedor Vidyaev" and a submarine in the military harbor of Sidi Abdallah, where our predecessors stood half a century ago.

In the mornings, cheerful Soviet songs and ancient Russian waltzes were played on the deck broadcast of the floating base. Russian old men, the same ones from the white squadron, gathered on the pier to listen to them. Despite the fact that the “special officers” did not recommend communicating with white emigrants, the ship’s radio operator, responding to the requests of the elderly, repeated “Danube Waves” and “On the Hills of Manchuria” several times. If only I knew then that such a person lives very close by - Anastasia Aleksandrovna Shirinskaya.

#comm#I've heard a lot about her. From Moscow it seemed: God’s dandelion was living out its life in silence and oblivion... When we met, I saw the elderly Shakespearean queen: dignity, wisdom and human greatness. #/comm#

All of Bizerte knows her. I spent a long time looking for the way to her house. No one could say where Pierre Curie Street was lost in the labyrinth of the port area. But when, in another vain attempt to clear the way, I accidentally said her name, the young Arab smiled and, exclaiming: “Ah, Madame Shirinsky!”, immediately led me to the right house. When she walks down the street, both young and old greet her. Why? Yes, because she worked all her life as a mathematics teacher at the Bizerte Lyceum. Even the grandchildren of her students studied with her. And the vice-mayor of Bizerte, and many high-ranking Tunisian officials who became ministers. Everyone remembers the kind and strict lessons of “Madame Shirinsky”; she never divided her students into rich and poor, she taught at home with everyone who had difficulty learning mathematical wisdom.

None of my students were embarrassed that the lessons were held under the icon of the Savior. One Mohammedan student even asked me to light a lamp on the day of the exam.

Most recently, the country's President Ben Ali presented the oldest teacher with the Order of Merit for Tunisia. She alone did more to strengthen the Arabs' trust in the Russians than a whole host of diplomats. Thank God, her name is now known in Russia.

#comm#I know a man who came from Sevastopol on a yacht to Bizerte, repeating the entire route of the Russian squadron with one goal: to raise the St. Andrew's flag in the city where it fluttered the longest, to raise it on the very day when it was sadly lowered - 29th of October. #/comm#

This was done by my comrade and colleague in the Northern Fleet, Captain 2nd Rank Reserve Vladimir Stefanovsky. He was in a great hurry to make sure that the symbolic lifting of the blue cross banner onto the mast took place in front of the eyes of that woman who, one of all the exiles who did not live to see that day, remembered how it was lowered and believed that one day it would be raised again. I believed for seventy years and three more years. And I waited!

It was truly a chivalrous gesture worthy of an officer of the Russian fleet.

Then Stefanovsky received her in Sevastopol. Of all those who left the city in 1920, only she managed to return there.

"I love you, Russia!" - A girl screamed from the African Cape Blanc Cap. And Russia heard her! And this is not a stylistic figure. I actually heard it! True, not immediately, after half a century. Little by little, compatriots began to come to the house on Pierre Curie Street near the port. They asked about the life of Russians in Bizerte, about the fate of the Black Sea ships... The first person to tell us about it publicly was TV publicist Farid Seyfulmulyukov. Then Sergei Zaitsev’s film about Shirinskaya was shown on blue screens. A Tunisian director made his film about her fate and the Russian squadron. In the “era of glasnost”, Bizerte and her “last Mohican” were discovered by many newspapers and magazines for themselves and their readers. In the year of the 300th anniversary of the Russian fleet, the President of Russia awarded Anastasia Shirinskaya anniversary medal. And two years ago, at the Russian embassy, she received her first (!) real passport in her life, almost the same as her mother’s - with a double-headed eagle on the cover. Before that, she relied on a refugee certificate, the so-called “Nansen” passport. It was written in it: “Exit to all countries of the world is allowed, except Russia.” She lived almost her entire life under this terrible spell, not accepting any other citizenship - neither Tunisian nor French - maintaining in her soul, like her father, like many sailors of the Squadron, her civic involvement in Russia. That is why the famous French magazine called Shirinskaya “the orphan of great Russia.”

#comm#Now she is not an orphan. With the echo of those old girlish exclamations from the White Cape, Shirinskaya returned her citizenship, and awards, and numerous invitations to her homeland, and a whole flock of letters that flew to Bizerte from all over Russia, even from Magadan. #/comm#

They wished her health, asked questions, invited her to visit... Our people are responsive. Recently, a flow of visitors to Pierre Curie Street has begun. Even during my short meetings with Shirinskaya, each time I met in her living room either a Russian naval attaché, or businessmen from St. Petersburg, or a historian from Moscow... She receives everyone in Russian - under the icon of the Savior with destroyer "Zharkiy", with tea and pies, which bakes itself, despite the years.

What else is she doing? She has an unemployed son in her care. She published a book of her memoirs, “Bizerte. The Last Stop,” in the Moscow Military Publishing House. In this day and age, it’s like publishing a book and even flying to Moscow for a presentation! She did it.

In addition to the usual household chores, she is preparing a Russian edition of her memoir book. Translates to French Russian romances. Looking for a sponsor to transfer a Tunisian video about the Russian squadron to a more durable film. He is busy restoring Russian graves at the municipal cemetery, paying ten dinars from his pension to the caretaker for his kind supervision. She is going to Ukraine in Lisichansk to visit her childhood friend Olya, who is now over ninety and who told her: “I won’t die until I see you.”

Shirinskaya has already been there. On the site of the family home with white columns there is a school.

But I feel much better now. After all, the house that I dreamed about so much no longer leaves me.

In the fall of 2001, the missile cruiser Moskva (Slava) arrived in Bizerte. It delivered a marble slab for the grave of the last commander of the Russian squadron, Rear Admiral Mikhail Behrens. The plate was placed on capital cemetery Borzhel. Then an honor guard in white uniforms, white jackets and gold shoulder straps walked past her to the “Farewell of the Slav” march. St. Andrew's flag fluttered over the sailors. Everything was as it should have been half a century ago.

It was Nastya Shirinskaya who waited, no, achieved with all her many years of life, so that Russia would give the highest military honors to her Squadron, our Squadron, the Russian Squadron.

Moscow - Bizerte

Special for the Centenary

From the editor: On February 28, an article “The Fate of the Russian Fleet” was posted on our website, telling about unique documents, stored in the Central Archive of the FSB of Russia. Today we present some of them dedicated to the Bizerte squadron, with the necessary notes and comments.

On November 3 (16), 1920, ships and vessels of the Black Sea Fleet, leaving the ports of Crimea, concentrated on the Constantinople roadstead. One of the most dramatic episodes in the history of the Russian fleet began - its stay in a foreign land. By order of the fleet commander No. 11 of November 21, 1920, the Black Sea Fleet was renamed the Russian squadron. Much has been written about the last years of the existence of the operational formation of ships under the St. Andrew's flag in the North African port of Bizerte over the past two decades. We remind readers that after recognition by France Soviet Russia the further existence of the squadron became impossible. October 29, 1924 St. Andrew's flags on the ships were lowered.

The Soviet government really hoped to increase the power Workers' and Peasants' the Red Fleet at the expense of the ships of the former Russian squadron. Demands for the return of the ships began to be put forward in August 1921, but at that moment there was no legal basis for such claims. Already in October 1924, the Marine Collection, published in Moscow, wrote: “We cannot doubt that the return of the ships is a matter of the near future, since by the very essence of the issue the fate of the squadron can in no way be the subject of future negotiations, especially on the economic plane. The return of the courts is the first step, arising from the logic of things, the logic of the moment, from the very essence of the fact of de jure recognition.<...>

We do not know their (the ships of the squadron - N.K.) actual technical condition, but, judging by the accurate data available, most of the ships were put into long-term storage, visited the docks and had their mechanisms repaired. And although the collapse of the squadron’s personnel was initially accompanied by thefts and attempts to sell off the ship’s property and inventory, one must think that the presence of some organization on the squadron (which appeared shortly after arriving in Bizerte) did not allow this phenomenon to develop.

In any case, long years of ownerless existence could not but affect the material part of the ships. This will have to be taken into account. But in the long series of works planned by the legal owner (discharge in the original - N.K.), there will be a place, strength and means in restoring the sea power of the Republic of workers and peasants to bring this part of the property of the people and the Red Fleet into proper combat shape"1.

As we see, representatives of the Red Fleet had very reliable information about the life of the squadron and even admitted the presence of “some kind of organization” on it. Most likely, such awareness can be associated with certain intelligence work, and with the fact that during this period there was still relatively free postal communication with foreign countries.

On December 20, 1924, the command of the Soviet Fleet appointed M.V. Viktorov “chief of a detachment of ships of the Black Sea Fleet located in Bizerte, leaving him in the post of head of the hydrographic department”, A.A. was appointed commissar of the detachment. Martynov. To tow ships in Odessa, a detachment was formed consisting of the icebreaker "S. Makarov" and the ice cutter "Fedor Litke".

At the end of 1924, a technical commission from Moscow arrived from Paris to Bizerte. It included the brother of Admiral M.A. Berensa E.A. Behrens - naval attache in England and France (captain 1st rank of the Imperial Navy), outstanding Russian shipbuilder A.N. Krylov, engineers A.A. Ikonnikov, P.Yu. Horace and Vedernikov.

Members of the commission initially feared that the ships of the squadron might be mined. However, back in July 1924, former naval agent in Paris V.I. Dmitriev told E.A. To Behrens: “I fully understand the need for a painless resolution of the Bizerte issue and share your view on the possibility of two options - for the personnel to remain on their ships or to leave peacefully, becoming refugees. I do not allow the possibility of a third, i.e. an attempt to destroy the ships - it is too "It's ridiculous and senseless. It seems to me personally that with the exception of certain individuals, everyone will leave the ships."

After the commission arrived in Bizerte, the French authorities confirmed Dmitriev’s words, saying: “Admiral Behrens gave his word of honor that none of his members did anything, and we trust him as an honest man.” The attitude of the French naval authorities towards the members of the Soviet commission generally seemed quite friendly. However, the French were very afraid of any Bolshevik propaganda from those arriving from the USSR and wanted to carry out all the supposed work on preparing ships for passage to Soviet ports only on their own (of course, on a paid basis). The Soviet sailors and engineers did not have any contact with the ranks of the Russian squadron who still remained in Bizerte, and the French tried to protect them from such. Moreover, the squadron commander, Admiral M.A. Behrens left the city for the entire duration of the commission's stay in Bizerte (from December 28, 1924 to January 6, 1925), not wanting to compromise his brother, who was to return to the country where the KGB terror was raging.

An inspection of ships and vessels showed that most of them were prepared by their crews for long-term storage. But in general the condition of the ships left much to be desired. E.A. Behrens wrote: “The impression from a superficial inspection is quite pessimistic. The ships are in terrible shape in terms of their appearance, everything that can rust and be easily damaged is rusted and broken, in the interior - in general, the same as for hulls and mechanisms, it is difficult to judge here after such a cursory inspection.Then the difference in condition, especially of small ships, is noticeable: three Novikas are in decent shape and even with serviceable artillery and apparatus, while the other two and the Tserigo under construction are poor , and they will have to be overhauled. The battleship, with the exception of the upper superstructures and boats, is apparently good, the artillery in the towers is closed after lubrication, and the French say that the cannons can be fired even now; in what form are the pipelines and wiring in general on ships, to say difficult, they require a more thorough examination, for which we have neither the people nor the funds." On some ships, even copies of the magazine "Red Fleet" were found, sent from Soviet Russia in exchange for the Bizerte "Marine Collection".

That, despite the rejection Soviet power, the majority of the sailors of the squadron were not only not inclined to destroy the ships, but with a certain understanding reacted to the fact that they would end up in Russia again, testified to a note from the former commander of the destroyer "Tserigo" with a list of books and ship documentation addressed to the "first red commander of the Tserigo" The commission worked in Bizerte from December 28, 1924 to January 6, 1925.

Members of the commission compiled a list of ships scheduled for return to the USSR: the battleship General Alekseev, the cruiser General Kornilov, 6 Novik-class destroyers and 4 submarines. The remaining ships and vessels, which were in a dilapidated condition, decided to sell for scrap.

However, the idea of transferring the ships to the Soviet side did not meet with the support of the French Senate and the public, who saw in this fact “a threat to French colonial possessions from the general plans of the Soviet government.” Also, many states (primarily the Baltic and Black Sea states), who did not want to strengthen the Red Fleet, opposed the transfer of the squadron. They were actively supported by the “mistress of the seas” Great Britain. A heated discussion on the issue of the return of the ships also unfolded in the League of Nations.

In addition, the mutual claims of the USSR and France regarding debt compensation also hampered a constructive solution to the issue. Russian Empire and damage from the intervention. The resolution of the issue was delayed, but in the first years the Soviet side still hoped to strengthen the fleet with the help of ships of the former Russian squadron. Thus, in the summary of information on the composition of the forces of the Workers' and Peasants' Red Fleet on April 1, 1926, it was stated: “The question of the need for the speedy return of the Bizerte squadron, the technical condition of which allows us to count on the possibility of putting ships into operation by repairing them, the cost of which is significantly less compared to the cost of new ships."2. By the end of the 1920s the situation had finally reached a dead end; The condition of the ships, which continued to sit at anchor without crews, became more and more deplorable. As a result, in 1930-1936. The Russian ships remaining in France were scrapped...

Two serious publications by the famous candidate naval historian are devoted to attempts to return the ships of the Russian squadron historical sciences N.Yu. Berezovsky (1949-1996). Both of them were prepared on the basis of materials from the Russian State Military Archive (RGVA)3.

The documents published below from the archives of the FSB of the Russian Federation are being introduced into scientific circulation for the first time. They are interesting because they show the view of state security agencies on the problem of the return of ships, and also highlight the position of foreign powers who are dissatisfied with the possible strengthening of the Red Fleet with the commissioning of ships of the Russian squadron. The letter from an unidentified person (a member of the technical commission for the return of ships, an employee of the OGPU) talks about the work of the commission and the attitude of representatives of the French authorities towards its activities. The intelligence report talks about surveillance conducted by representatives of the French intelligence services on members of the commission. Report of Major General S.N. Pototsky, a copy of which was obtained through intelligence, is dedicated to Sweden’s attitude towards the possible strengthening of the RKKF. Two other documents show the views of the Finnish and Romanian governments on this issue.

No. 1. Letter from an unidentified person to an unidentified addressee, dedicated to the stay of the Soviet technical commission in Bizerte

Dear comrade,

The inspection results are as follows:

a) Not a single ship can sail on its own, so only transportation by tow is possible.

b) Recognized as fit for further service: the battleship "[General] Alekseev"4, the cruiser "[General] Kornilov"5, 6 destroyers ("Novikov")6 and 4 submarines7.

c) The battleship "George the Victorious" (which is now a barracks for the whites), the cruiser "Almaz", the training ship "Seaman"8 and 4 old destroyers9 were declared unfit for further service and subject to sale for scrap. The cost of scrap is approximately equal: "George" - 25 thousand pounds sterling, "Almaz" - 8-9 thousand pounds sterling, "Seaman" - 500 pounds sterling and destroyers 700 pounds each10.

d) To bring the ships into a condition in which they can be towed from Bizerte to a port in the Black Sea, it is necessary to carry out special repairs on them, which would make them capable of sailing on the high seas. This repair will require about 50 thousand gold rubles of money and about three months of time. Small vessels can be ready to leave much earlier. To fix the steering gear of the battleship, the latter will have to be taken to one of the French ports, since the port of Bizerte is not able to cope with this task. The rest of the repairs of the battleship, as well as the repairs of small ships, are undertaken to be carried out by the Bizerte company "Vernis". Calculations of money and terms are given approximately, since an accurate calculation requires a more detailed examination and longer work by specialists than what our commission in Bizerte could carry out.

e) The cost of the battleship and 6 Novikov (the most valuable part of the flotilla) is estimated by Professor Krylov approximately: battleship - 35 million rubles in gold, 6 destroyers - 15 million rubles in gold. To bring these ships into full combat readiness (this is already the work of our Soviet ports) it will take from 10 to 15 million gold rubles.

f) The artillery11 available on the ships is, as far as a quick inspection can judge, in more or less satisfactory condition. As for military supplies, the question of them here, on the spot, became on a different plane than it was imagined in Moscow. The fact is that the shells located in the cellars of the battleship and cruiser, as well as on the shore in the French warehouse, are of very significant value, equal to approximately (roughly) 3 million rubles. The directive of Genrikh Grigoryevich12 - to throw all these shells into the sea so as not to expose the ships to the danger of explosion - in view of the value of the shells (especially 12-inch ones, of which there are about 13,100 thousand on the battleship14), makes it necessary to raise again the question of the final fate of such valuable artillery property. The commission itself, without raising this issue for Moscow's permission, does not dare to destroy the shells on board the ships. The question of projectiles can be resolved as follows:

1) or leave them in the cellars of the battleship and cruiser, having first carried out a thorough inspection of the ships themselves and their cellars in order to establish the degree of safety of storing ammunition on them, as well as examining the shells themselves - in order to establish the degree of their safety for transportation, and under the concept of safety we must understand both safety from a purely technical point of view, and from a specific point of view (the absence of infernal machines installed by whites on ships and in cellars, the laying of pyroxylin bombs with the inclusion of their fuses in the electrical wiring of ships, etc.);

2) or clear all ships of combat supplies, reloading the latter onto a ship specially designated for their transportation.

The second combination will require significant costs for reloading and packaging of projectiles, and these costs may exceed the cost of the projectiles themselves. This is all the more likely since the French are unlikely to agree to allow a significant number of our crew into Bizerte, and in this case all the work of reloading and packing the shells will have to be done by hired French labor.

In any case, it is necessary to find out from Morved what value the shells located in Bizerte have for the latter and what he plans to do with them, taking into account, on the one hand, the need to take comprehensive measures for the safety of the passage of the Bizerte flotilla, and on the other hand, the need to spend significant funds for the transportation of shells in the event of their evacuation from ships.

If Morved is inclined to retain these shells, let him accept one of the two options I have proposed and communicate his decision to the commission. In the event of shells being left on ships, the Marine must give comprehensive instructions to the responsible specialists sent by him to accept the artillery property regarding the sorting of this property, its storage and generally taking measures for the safety of transporting shells on ships.

g) The general condition of ships in terms of their safety from fires, explosions and other accidents is as follows.

The vessels are located in three locations:

a) a group consisting of a battleship and a cruiser is located in the roadstead of Bizerte Bay, far from the coast;

b) a group consisting of 15 destroyers, Almaz, Moryak and four submarines - near the coast, a few kilometers from the first group, next to the French ships;

c) “St. George the Victorious” stands completely separately near the shore, at the very outskirts of the city of Bizerte.

The ships of the first two groups are guarded by French sailors, under the supervision of “meters” (corresponding to our former ensigns). General supervision of these groups is entrusted to individual French naval officers.

"St. George the Victorious" is at the complete disposal of White.

"Alekseev", "Kornilov", "Noviki", yes, one might say, all the ships, are littered with various rubbish, among which, however, there is also valuable property (spare artillery parts, machine guns with machines for them, some measuring instruments, however, requiring repairs, Russian and foreign rifles, cables, etc.). There is a lot of dirt and rubbish everywhere. Most of the ships can be said to be dirty.

In terms of fire, all this rubbish poses an undoubted danger.

There is no gunpowder on any ship - this is what the French said. It is not possible to inspect all the ships, in the compartments of which gunpowder and other explosives may be lying around here and there, without first dismantling the trash on the ship.

Shells are available only on the Alekseev (battleship) and Kornilov (cruiser). If on the "Alekseev" they are put in some order (relative, of course), taken into account, and the cellars in which these shells are located are closed, and the keys to them are on "one bunch", if not with one French sailor, then on " Kornilov's storage of shells is in a disgraceful state: the cellars are open, and none of the French know anything, no one knows what is in these cellars and how much of what is in them.

In one of the cellars we found rifle cartridges scattered on the floor, which poses a direct fire hazard.

When we reported all these problems to the French, they first promised to take appropriate measures to eliminate some of them (close the lids of the cellars, clean the cellars themselves), but soon in practice they abandoned the promise due to the impossibility of carrying out the promised action without preliminary repairs.

Bizerta. Half-sunken destroyers of the former Russian squadron

At the last joint meeting with the French, we nevertheless made our wishes (we “did not have the right” to make demands as a purely technical commission, whose task is only to inspect ships and determine their suitability for further service) regarding improving the condition of the ships in terms of their security, which was recorded in the minutes of the meeting. But, of course, these reservations can do little to change the actual state of the courts, which, essentially speaking, is completely at the mercy of the French and all sorts of accidents. And if the French find it advantageous at one fine moment to sink our ships, then they can calmly do this, citing some accident.

The only way out of the situation, the only guarantee of the safety of our ships is to get the ships into our hands as soon as possible, to put our people on them, to clean the ships from “all filth” and then to properly maintain and protect them.

If the French delay the transfer of the flotilla to us, then it would be possible to recommend, as a palliative to guarantee the safety of our ships, sending the French a special note holding them responsible for the condition and safety of the ships of this flotilla. But this is a matter of high politics.

h) Upon arrival in Paris, I learned from Unylov that the resolution of the issue of transferring the flotilla was apparently being postponed by the French indefinitely. This is evidenced by the message from our sources regarding the pressure on the French from the Romanians, and the same is also evidenced by the unfavorable outcome of our Embassy’s requests to the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs to speed up the matter of transferring the flotilla to us. The fact is that, on behalf of Comrade. Krasina17 comrade Volin18 the next19 day [after] our departure from Bizerte was on a visit to Laroche, the head of the political department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs20, who responded to Volin’s request to begin negotiations on transferring the flotilla to us in view of the return of our commission from Bizerte and the completion of its inspection of our ships that, firstly, he had not yet read the report of the Ministry of the Navy, and secondly, the issue of transferring the flotilla, due to its complexity, would be submitted for preliminary consideration to a special legal commission. This answer clearly shows that the French will delay the transfer of the flotilla to us.

i) Our stay in Bizerte went extremely smoothly, without any incidents. From the French we met with assistance and official courtesy. True, we were completely isolated from outside world, we were not allowed to go to Tunisia, we were followed, but all this did not go beyond the usual framework. In the local press, as is French custom, they wrote all sorts of nonsense and tall tales about us, but due to our humble behavior and our abstinence from propaganda, we earned in the same press the unfortunate epithet “bon et pésiable bourgeois”21. According to rumors, the naval prefect of Bizerte22 sent a favorable report about us to Paris, which does not prevent him, however, from speaking out against allowing our team into Bizerte.

j) Due to the French delaying the moment of transferring the flotilla to us, our stay in Paris threatens to drag on indefinitely. In this regard, I expect orders from you regarding my future fate. I also ask you to give me an answer to some of my proposals with which I addressed you in my last letter.

Typescript with handwritten notes. On the first page of the document there is a stamp “Outside the INO-GPU. Entrance No. 580/item 16.1.1925”; on the last page there is a note from an unidentified person dated April 5, 1929.

No. 2. Agent report from Paris of the Foreign Department of the Trans-Cordonnay Unit of the OGPU about the work of French intelligence during the stay of the Soviet commission in Bizerte

Simultaneously with the Krylov commission, which traveled to Bizerte, French intelligence sent 6 people from Paris to spy on our delegation. Together with these French, at the request of the French, two Polish spies (the name of one of them was Kensik) went. The intelligence officers were instructed to monitor whether our commission was conducting propaganda in the colonies, and most importantly, whether our commission had contact with anyone in Marseilles and Bizerte. The other day, the intelligence officers returned to Paris and presented a detailed report. They gave our commission a complete “certificate of trustworthiness”; it was not involved in propaganda and had no connections anywhere.

Before our commission arrived in Bizerte, people from Paris were specially sent there in order to render our squadrons as unusable as possible. This was done so that the “Bolsheviks” would lose any desire to demand such rubbish.

Typescript. Copy. The document contains notes: “Top secret. 6 copies. 1 - to Comrade Chicherin, 2 - to Menzhinsky - Yagoda, 3 - “B”, 4 - to the affairs of the Bizerte Fleet.”

No. 3. Accompanying material and report from Major General S.N. Pototsky23, dedicated to Sweden’s attitude to the possible return of the USSR ships of the Russian squadron in Bizerte

Copenhagen

Attached is a secret report from the representative of [Grand] [Prince] Nikolai Nikolaevich24 in Denmark, General Pototsky, on the issue of Sweden’s concerns in connection with rumors that have arisen about the transfer of the so-called “Wrangel fleet” to the Baltic Sea.

Indeed, the reactionary Swedish press is sounding the alarm about this, and the influential Svenska Dagbladet recently issued a statement that Sweden needs to join the protest of the other Baltic countries against the strengthening of the Red Fleet.

The reference to the construction of new ships of the Swedish navy needs to be corrected: these ships began construction a long time ago, and about 5.4 million [Swedish crowns] are needed to complete the work, which is included in the Swedish budget for the current year along with the general allocation for the defense of the country.

Typescript. Copy. The document contains the following notes: “Top secret. 13.2.25 INO OGPU No. 2471/p dated 13.02 from Copenhagen 9.II.25 to Berzin, vol. b, to the case of the Bizerte Fleet.”

February 192525

Copenhagen

The question of the possible transfer of Russian military ships located in Bizerte to the Baltic Sea is extremely occupied by political circles in Sweden. The entire press, with the exception of only communist organs, openly declares that Sweden has a historical interest in the existence of the current Baltic republics and that the strengthening of the Red Fleet is an immediate threat to their existence.

According to Swedish data, the Soviet government not only restored the previous composition of the Baltic squadron, but also supplemented it with two new dreadnoughts, recently completed at the Kronstadt docks. If the ships from Bizerte are actually transferred to the North, then the Bolsheviks will turn out to be the strongest power in the Baltic Sea and the current status quo will soon be broken.

In parliamentary circles it is argued that England will in every possible way prevent the naval strengthening of the Bolsheviks in the Baltic states, and among the conservative party there is a strong desire to induce Sweden to speak out openly and declare its solidarity with Estonia, Latvia and other peripheral formations, which see the strengthening of the Red Fleet a direct threat to yourself. At the same time, right-wing political parties consider a naval military conflict with Russia to be inevitable sooner or later and are vigorously campaigning for an expansion of Sweden's naval construction program. Despite the fact that the current Social Democratic government of the country is a supporter of arms reduction, nevertheless, it has contributed to the estimate for the current year over five and a half million crowns necessary to complete the construction of two torpedo cruisers, two submarines and two motor torpedoes, with which the Swedish fleet will be replenished in the near future; at the same time, the issue of creating a voluntary fleet through popular donations is currently being seriously developed.

Sent to Paris, Sremski Karlovice, Belgrade, Berlin and Helsingfors.

Typescript. Copy.

No. 4. Letter from the British Ambassador to Finland26 to the British Foreign Office on Finland’s attitude to the possible return to the USSR of the ships of the Russian squadron in Bizerte

Helsingfors

My French colleague told me that a few days ago the Bolshevik representative brought to the attention of the Finnish government that the Wrangel fleet would under no circumstances be transferred to the Baltic Sea.

As you know, Finnish public opinion is always inclined to worry about Soviet naval forces in the Gulf of Finland: so, although these vessels cannot be a serious factor for a country that has some naval forces, this statement will to a certain extent reassure public opinion here.

Typescript. Copy. The document contains the following notes: “Top [top] secret. INO OGPU No. 3278/II dated 27/II 23/II-25 1) Chicherin, 2) M27, 3) Menzhinsky - Yagoda, 4) 7, 5) b, 6) to the case of the Bizerte fleet."

No. 5. Information on Romania's attitude to the possible return to the USSR of ships of the Russian squadron in Bizerte

Romania proposes the establishment of an allied naval base in Constanta.

On February 23, the Romanian ambassador visited the British ambassador in Paris. The purpose of the visit was to present the view of the Romanian government on the possibility of the appearance of the Bizerte fleet in the Black Sea. The Romanian ambassador expressed the hope from his government that if indeed the Soviet fleet ends up in the Black Sea, England and France will organize a Black Sea naval base, with Constanta considered the most suitable port for establishing a base for an allied squadron. The English ambassador replied to Diamandi28 that, according to his information, the Bizerte fleet was in such a state that, in any case, during the period of time that is usually taken into account when making plans, it would not be able to play a dangerous role. The Romanian ambassador insisted, however, that the very fact of the Soviet flag flying in the Black Sea waters was very unpleasant and inconvenient for both Romania and Bulgaria and that the Anglo-French squadron should be opposed to it. The British ambassador, promising to report this to his government, expressed the opinion that it is unlikely that any allied action in the Black Sea can be expected in the near future.

Typescript. Copy. The document contains the following notes: “Top [top] secret. Abstracted from English. The material is reliable. INO OGPU No. 5143/item dated 19.III, Comrade Berzin, Comrade Chicherin, Comrade Menzhinsky - Yagoda , Comrade Stalin, Comrade T., Comrade E., Comrade B., to business, Dzerzhinsky."

Notes

1) Bizerte squadron // Naval collection. 1924. No. 10.

2) RGVA. F.7. Op.10, d.106, l.12.

3) Russian squadron in Bizerte: RGVA documents on negotiations between representatives of the USSR and France on the return of ships of the Black Sea Fleet. 1924-1925 // Historical archive. 1996. No. 1. P.101-127. The tragedy of the Russian fleet (new documents about the fate of the Bizerte squadron) // Gangut. Issue 21. St. Petersburg, 1999. P.2-15.

4) Battleship"General Alekseev" is one of three Black Sea dreadnoughts of the "Empress Maria" class. Until April 16, 1917 - "Emperor Alexander III", until October 17, 1919 - "Will".

5 Cruiser "General Kornilov", until March 25, 1907 - "Ochakov", until March 31, 1917 - "Kahul", until June 18, 1919 - again "Ochakov".

6 “Bold”, “Wrathful”, “Restless”, “Hasty”, “Ardent”, “Tserigo”.

7 "Petrel", "Seal", "Duck", "AG-22".

8 Barquentine "Sailor" (formerly "Grand Duchess Ksenia Alexandrovna", in 1917 renamed "Freedom") was a training ship of the Naval Corps in Bizerte.

9 "Captain Saken", "Hot", "Vocal", "Zorky".

10 So in the text of the document. Most likely, we are talking about amounts of 5,000 and 7,000 pounds sterling.

12 Yagoda Genrikh Grigorievich (1891-1938), from September 1923 - second deputy chairman of the OGPU.

13 "about" is written by hand.

14 The figure given in the document has nothing to do with reality. The full ammunition load for one 12-inch gun consisted of 100 rounds, i.e. the maximum number of shells of a given caliber could not exceed 1200.

15 "consisting of" is written by hand.

16 “speaks of the same thing” is written by hand.

17 Krasin Leonid Borisovich (1870-1926). In 1920-1923 - Plenipotentiary and Trade Representative in Great Britain; simultaneously People's Commissar foreign trade. In March 1921 he signed the Anglo-Soviet trade agreement. In 1922 participant international conference in Genoa and The Hague. In 1924, plenipotentiary representative in France. Since 1925, plenipotentiary representative in Great Britain.

18 Most likely, we are talking about Lev Lazarevich Volin (1887-1926) - the head of the Special Unit under the Currency Administration of the People's Commissariat of Finance in 1923-1926.

19 Crossed out “on the very”, written in by hand “on the other”.

20 Crossed out “Eriot’s office”, handwritten “Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs”.

21 Fr. bonne et paisible bourgeois - kind and peaceful bourgeois.

22 From July 1922, this position was occupied by Rear Admiral A. Ekselmans, who in 1925 was dismissed because (according to one of his contemporaries) he refused to “surrender the remains of the Russian squadron... to the Bolsheviks.”

23 Pototsky Sergei Nikolaevich (1883-1954) - Russian military agent in Denmark during the First World War. In exile he lived there.

24 Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich (junior) (1856-1929). On November 16, 1924, he took over the general management of the largest military organization Russian abroad - Russian all-military union. Among the white emigration he was considered a contender for Russian throne as the eldest member of the dynasty, although he himself did not express any monarchical claims.

25 The exact date is not in the original document.

26 Ernest Amelius Rennie - British Ambassador to Finland 1921-1930.

27 Crossed out - "Berzin".

28 Ambassador of Romania to Russia since 1913. In 1918, he was arrested by the Bolsheviks, but was soon released.

Preparation for publication and comments by N. Kuznetsov