We are already somehow used to the fact that gold is found on sunken ships somewhere in the southern warm seas. But sometimes gold bars are raised in our northern seas. So, in 1981, more than 5 tons of gold bars were raised from the sunken cruiser Edinburgh in the Barents Sea. And the hallmarks on them were not of the Spanish or English kings, but of the Soviet Union. But first things first.

In 1939, the British Royal Navy received two new light cruisers. The displacement of each of them was 10.2 thousand tons, each was armed with a dozen six-inch guns, numerous anti-aircraft guns, developed top speed 32 knots. In general, the twins, and only. "Belfast" safely survived the Second world war and now stands on the Thames in London, turned into a memorial ship. The fate of Edinburgh was different.

On April 28, 1942, convoy QP-11 left Murmansk for the west: thirteen transports guarded by six destroyers, four guards and an armed trawler. Not far from the convoy, the cruiser Edinburgh was moving, writing out an anti-submarine zigzag, on which Rear Admiral Bonham-Carter held the flag. On board the Edinburgh were 93 wooden boxes containing 465 bars of gold - about 5.5 tons of the precious metal in total - partly payment for Soviet purchases in the UK and the USA made in excess of the Lend-Lease program (Lend-Lease deliveries were not subject to payment until the end of the war), partly - "reverse lend-lease": raw materials were supplied for the production of communications equipment for the USSR, which was used to gild the contacts of all telephone, radio and navigation equipment produced for Soviet army, aviation and navy.

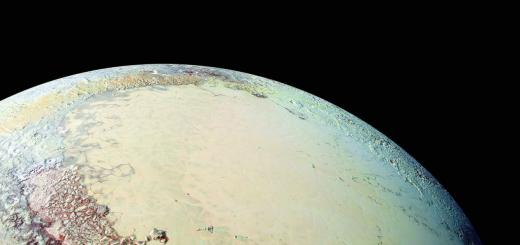

On April 30, 187 miles north of Murmansk, the Edinburgh was discovered by a German submarine - U-456. At 16 hours and 18 minutes, the cruiser's hull shuddered from a strong explosion on the starboard side under the stern tower - her entire crew died, and a few seconds later a second column of water and smoke rose above the stern. This hit decided the fate of the cruiser - he lost two propellers, a rudder and could only move at a speed of 3.5 knots, with difficulty driving machines. On May 2, she was finished off by German destroyers and sank in the Barents Sea.

The death of the Edinburgh caused mutual reproaches among the British and Soviet sailors. The British referred to the fact that those responsible for fighting the Soviet Union was on this stretch of the sea. They reproached that the Soviet destroyers allegedly left the battlefield and went to the base to celebrate May 1. Soviet sailors believed that the heroically fighting Edinburgh could still stand up for itself and was sunk by the British prematurely. The gold and personal effects of the crew could be reloaded onto other ships. All these accusations were largely unfair. The cruiser lost 57 people killed and 23 wounded in battle. Both sides did not mention the loss of gold, and it seemed that this secret was forever buried at the bottom of the sea.

But the "golden cruiser" was remembered a few years after the war, when several ship-lifting companies, including the Norwegian one, expressed their readiness to extract the precious cargo. However, the British declared the ship a military grave, therefore, none of the foreigners had the right to disturb the eternal sleep of fifty sailors who shared the fate of the Edinburgh.

But in the 70s of the last century, a man appeared who set as his goal to find "Edinburgh" and raise gold to the surface. This man was a tireless adventurer and excellent sailor Keith Jessop. He used to serve as a boatswain and went around the entire coast of the Scandinavian Peninsula in search of information about ships sunk during the war. From the Norwegian sailors, he managed to find out the approximate coordinates of the place of death of the Edinburgh. Jessop organized a company and began to seek permission from the USSR to conduct search operations.

Only in April 1981, a Soviet-British agreement was concluded and a contract was signed with the private firm Jessop Marine Recoveries. Jessup's firm entered into a contract with the British government, received permission to work in a war grave, and immediately set about organizing an expedition. The contract was concluded on generally accepted international terms: "Without salvation, there is no reward." According to him, Jessop's company received, if successful, 45% of the value of the salvaged cargo. Everything else was divided between the British and Soviet sides - 1:3.

Work began on May 9, 1981. On May 14, the rescue ship Dammator found the vessel at a depth of 250 meters, lying on the bottom on its left side. The second stage of work began in September 1981 with the use of the Stephaniturm vessel, which was more suitable for such an operation. In total, 431 bars of gold were raised with a total weight of 5129.3 kilograms. Due to the fatigue of the divers and the worsening weather on October 5, it was decided to interrupt the work on lifting the cargo. October 9 "Stefaniturm" with gold came to Murmansk.

The distribution of gold was carried out in accordance with the agreement reached and the ownership of the cargo in accordance with the current rules as follows: 1/3 - Great Britain, 2/3 - the USSR. The rescuers received 45% of the salvaged gold as payment for the rescue.

The rest of the gold was raised five years later, in September 1986. The contract for the rescue of cargo was signed with the same firm "Jesson Marine Recoveries". The ship "Deepwater-2" was used for lifting. 29 ingots weighing 345.3 kilograms were lifted. Five bars of gold weighing 60 kilograms remained lying at the bottom of the Barents Sea.

HMS Edinburgh (C16) is a British Town-class light cruiser (subclass Belfast), one of 9 cruisers of this type in the Royal Navy. navy During the Second World War. Named (March 31, 1938) in honor of Edinburgh - the capital of Scotland.

IN last trip escorted convoy QP-11 (04/28/1942 Murmansk - 05/07/1942 Reykjavik).

He had about 5.5 tons of gold on board - partly payment for Soviet purchases in the UK and the USA made in excess of the Lend-Lease program (Lend-Lease deliveries were not payable until the end of the war), partly - "Reverse Lend-Lease": raw materials were supplied for the production of communications equipment for the USSR, which was used to gild the contacts of all telephone, radio and navigation equipment produced for the Soviet army, aviation and navy. Sunk on 2 May 1942 in the Barents Sea by submarine U-456 (Captain Max-Martin Teichert).

Main characteristics:

Maximum length 190.17 m, 187.88 m at the waterline, 179.65 m between perpendiculars.

Width 19.32 m.

Engines 4 Parsons turbo-gear units, 4 three-collector boilers of the Admiralty type.

Power 82 500 l. from. (60 MW) - design.

Speed 32.5 knots at standard displacement, 31 knots at full displacement.

Cruising range 10,100 nautical miles at 12 knots.

Crew 730 people.

Armament:

Artillery 4×3 - 152mm/50 Mk-XXIII guns in MK-XXIII turrets.

Anti-aircraft artillery 6 × 2 - 102 mm / 45 Mk-XIX, 2 × 8 - 40 mm "pom-poms".

Mine-torpedo armament 2 triple-tube 533-mm TR-4 torpedo tubes.

The last trip of "Edinburgh"

At the end of April 1942, the Edinburgh, at the head of a convoy of ships, left Murmansk for England. On board the cruiser in Murmansk, according to surviving documents, 93 wooden boxes were loaded, which contained 465 bars of gold weighing 5534603.9 grams (195548 ounces).

On April 30 (according to other sources, May 1), 187 miles north of Murmansk, the Edinburgh was torpedoed by the German submarine U-456 (commander Teichert). The cruiser received two torpedoes: one hit the port side, the second hit the stern. "Edinburgh" lost speed, but remained afloat. Two British destroyers came to the rescue and, under their escort, the cruiser tried to return to Murmansk, however, soon three German destroyers under the command of the frigate captain Schulze-Ginrix approached. They opened artillery fire on the Edinburgh and fired torpedoes. One of the torpedoes hit the stern of the cruiser, after which he tilted even more to the port side.

During the battle, the German destroyer Hermann Schomann was sunk. The remaining two German destroyers removed the crew from it and withdrew. Rear Admiral Carter, who led the operation, ordered the English destroyers to remove the crew from the Edinburgh and finish off the cruiser with torpedoes. A British destroyer torpedoed the cruiser Edinburgh with two torpedoes to port. The ship sank along with the gold at a depth of approximately 900 feet (about 260 m). All crew members - 750 people were taken to Murmansk.

The gold on board the Edinburgh was insured by the USSR State Insurance. 1/3 of the gold was reinsured by the British War Risk Insurance Committee.

Raising gold from the cruiser "Edinburgh"

The idea of raising gold from a sunken cruiser arose as soon as the technical possibilities for this operation appeared.

Attempts to raise gold were made repeatedly.

In 1979, the Norwegian firm Stolt-Nielsen Rederi applied to the Soviet embassy with a notification about the search for ships that disappeared during the Second World War in the Barents Sea.

Negotiations with this firm ended in vain, despite the fact that she spent about a million dollars to prepare the operation to raise the gold.

Later in 1981, an agreement was reached and a tripartite contract was signed to search for and raise sunken gold. The parties under the contract were the British Ministry of Trade, the USSR Ministry of Finance and the British company Jesson Marine Recoveries, which was supposed to carry out an operation to search for and raise gold.

Preparations for the operation to raise gold were also carried out on board the cruiser Belfast, similar to the Edinburgh, standing on the Thames in London, opposite the Tower.

Work began on May 9, 1981. On May 14, 1981, the Dammator rescue vessel discovered the vessel at a depth of 250 m, lying on the bottom on the port side.

The second stage of work began in September 1981 with the use of the second vessel, the Stephaniturm, which was more suitable for such an operation.

Work on the rise of gold was carried out around the clock. boxes after long stay collapsed in the water, everything was covered with a thick layer of silt and fuel oil. Divers using a soil pump with difficulty, at times by touch, found gold ingots and loaded them into a grid, with the help of which the gold was lifted aboard the ship.

Representatives of INGOSSTRAKH were constantly on duty on board the ship, recording the number of ingots lifted. In total, 431 bars of gold were raised with a total weight of 5129.3 kg. Due to the fatigue of the divers and the worsening weather, on October 5, it was decided to interrupt work on lifting the cargo. On October 9, 1981, the ship "Stefaniturm" came to the port of Murmansk with raised gold.

The distribution of gold was carried out in accordance with the agreement reached and the ownership of the cargo in accordance with the current rules as follows: 1/3 - Great Britain, 2/3 - the USSR. The rescuers received 45% of the salvaged gold as payment for the rescue.

The rest of the gold was raised five years later, in September 1986. The contract for the rescue of cargo was signed with the same firm "Jesson Marine Recoveries". The ship Deepwater-2 was used to lift the gold. 29 ingots weighing 345.3 kg were lifted. Five bars of gold weighing 60 kg were left lying at the bottom of the Barents Sea.

Cruiser "Edinburgh", sunk with a cargo of Soviet gold.

In 1981, a unique operation was carried out in the Barents Sea to rescue a cargo of gold from the British cruiser Edinburgh, which sank to the bottom back in 1942. The exemplary professionalism shown by the rescue team during the search and recovery work, as well as the amount of recovered valuables, deserves special attention from specialists and people who are interested in underwater archeology and treasures.

The mentioned cargo of gold was loaded onto the Edinburgh on April 25, 1942 in Vaenga (near Murmansk). From that moment on, the cruiser of the British fleet became part of covert operation for the transfer to the allies of the next payment of the government of the USSR for deliveries under lend-lease. On that day, Edinburgh accepted into its cellars 93 boxes containing 465 gold bars, weighing just over 5.5 tons.

On April 28, the cruiser, escorted by the destroyers Forsythe and Forester, went to sea and the next day joined the QP-11 convoy. In guarding this caravan of ships en route from Murmansk to England, there were now 6 British and 2 Soviet destroyers, a cruiser, 4 corvettes, and British minesweepers.

On the same day, April 29, the convoy was discovered by German air reconnaissance. The first attack on the caravan took place the next morning. This forced Rear Admiral Bonham Carter of the Royal Navy, who was on the Edinburgh, to leave the caravan. This decision is explained by the fact that, being in a convoy, a modern high-speed cruiser was forced to move at the speed of other ships. So he lost one of his significant advantages and became vulnerable, which was unacceptable for warship with such valuable cargo on board.

The cruiser separated from the bulk of the ships and, without taking an escort, moved away from the head of the caravan by about 15-20 miles. Here a lonely ship was noticed by the captain of the German submarine U-456, Max Tihart. The submarine fired 3 torpedoes at the cruiser. Edinburgh could not avoid two of them. The explosions caused great damage, partly tearing off, and partly damaging the stern of the ship, depriving the ship of rudders and propellers, and, accordingly, the ability to move. The Soviet destroyers Thundering and Crushing and the British destroyers Foresight and Forester approached the damaged Edinburgh within 1.5-2 hours on a signal for help. They managed to prevent a second attack by the German submarine.

The crew of the Edinburgh, immediately after the torpedoing, began to fight for damage, however, despite the cessation of the flow of sea water into the compartments, there was now no question of continuing the transition to England. Rear Admiral Bonham Carter decided to return to Murmansk. It was not possible to tow the damaged cruiser, so by the night of May 1, the ship began to move back at low speed (about 3 miles per hour) with the help of bow turbines.

Accompanied by Edinburgh, both British destroyers remained on the way to Murmansk, and instead of the Soviet Thundering and Crushing, English minesweepers and the Soviet patrol ship Rubin approached.

British cruiser Edinburgh damaged by a torpedo explosion.

The German command, not wanting to let go of the badly damaged British cruiser, sent 3 destroyers to intercept. They overtook the Edinburgh and her escort on the morning of 2 May. During the battle, one of the German ships was badly damaged and subsequently flooded, but the Edinburgh also received another torpedo on board. The remaining German destroyers were superior in firepower to the escort of the British cruiser, therefore, in order to quickly get away from the battlefield, Bonham Carter orders the team to leave the ship. The crew was taken on board by the minesweepers Gossamer and Harrier. But the valuable cargo remained on the Edinburgh. There was no time to reload it, no opportunity - the bomb cellar with gold was flooded with outboard water even during the first torpedoing of the cruiser. Around 9 am on May 2, the abandoned Edinburgh was sunk to the bottom, finishing off with a torpedo from the destroyer Forsyth.

So tragically ended the battle path of the light cruiser of the British fleet "Edinburgh". With 57 dead sailors on board, the British government declared the ship a war grave.

The cargo of gold was also lost for many years. The depth at the site of the ship's sinking turned out to be significant and technically unattainable. Yes, and the rights to the "underwater treasure" belonged to the State Insurance of the USSR and the British Government War Risk Insurance Bureau. Therefore, it was impossible for any private contractor to carry out rescue work at the crash site of the Edinburgh without the consent of both parties.

Immediately after the end of the war, information about the sunken gold appeared in the press, and there were plenty of people who wanted to start raising the values. The governments of the USSR and England have repeatedly shown interest in this issue.

By the beginning of the 80s, the countries came to mutual understanding. By that time, the British government had already lifted the ban on work at the site of the sinking of their warship. To raise the cargo of the cruiser from the bottom of the Barents Sea, something like a competition was held, where among the many applicants they chose the candidate who was best prepared to work on board the Edinburgh.

Keith Jessop is a diver and explorer who led the search and recovery of the Edinburgh's gold cargo.

The most suitable for this role was the company "Jessop Marine Recoveries". Keith Jessop, who headed the company, had considerable experience in underwater work. In addition, at the time of the competition, he turned out to be the most knowledgeable about the history of the Edinburgh and the alleged place of its flooding. Keith Jessop has been collecting information for a long time and even in 1979 conducted an expedition to mark the area where the cruiser sank. Well-known European companies have become partners of Jessop Marine Recoveries in the planned search and rescue operation, providing Jessop's team with a ship and modern equipment.

On May 5, 1981, an agreement was concluded between representatives of the Soviet and British governments and the Jessop Marine Recoveries company. According to this agreement, 45% of the gold cargo lifted went to a consortium of partner companies led by Keith Jessop. The remaining 55% were divided between the USSR and England in shares corresponding to the insurance obligations paid by them during the war years for the lost cargo. All costs and risks fell on Jessup's consortium.

Cruiser Belfast. Like the "Edinburgh" belonged to the "Town" class cruisers.

The preparatory phase of the operation began. To work on board the Edinburgh, a team of 16 top professional divers from around the world was recruited, who passed the most severe selection according to many criteria. We also studied the internal structure of the cruiser using the Belfast of the same type as an example. In order to further narrow the search area, we studied all available archives containing information about the last battle of the Edinburgh and correlated the data obtained with information from fishermen about the hooks of their trawls in that area of the Barents Sea about obstacles on the bottom. Thus, two relatively small areas for the upcoming searches were identified.

The Dammator ship entered the designated area, which already on May 14, using sonar, identified a large ship resting on the bottom at a depth of 250 meters, and the next day, the data received from the underwater remote-controlled vehicle confirmed that Edinburgh had been found.

For the next stage of the expedition - lifting the cargo, they connected a diving complex specially equipped for this, the vessel "Stefaniturm". The available equipment allowed divers to work at depths of up to 400 meters.

Ship "Stephaniturm".

On board this ship, which left for the work site on August 28, were representatives of the governments of the USSR and Great Britain. A week later, the divers were already making their first dive to the bottom of the Barents Sea at the site of the cruiser's sinking.

The very first descents showed that there was a lot of work to be done - the hole through which they planned to get to the compartment with gold was cluttered with broken, twisted iron, littered with ammunition. We decided to cut another "entrance" in the side of the vessel - it was less labor-intensive.

Throughout the underwater part of the operation, the divers lived in pressure chambers in the hold of the Stephaniturma, sinking daily to the bottom in pairs in a diving bell. This approach saved a lot of time, eliminating the cost of daily decompression procedures. Divers had to go through this procedure once after the completion of rescue operations. For breathing outside the diving bell at the bottom, a special breathing mixture was used.

After 10 days of work inside the cruiser's hull, which took place to clear the rubble and clear the passage, we managed to get to the artillery cellar, which stored the valuable cargo. It took a few more days to clean the cellar itself, and only then did the long-awaited ingots appear. The first bar of gold was found by diver John Rossier.

The result of a successful rescue expedition aboard the Edinburgh.

The extraction of the gold cargo was accompanied by the inevitable further clearing of the premises. This process took another 10 days, and by the beginning of October, 431 ingots had been raised to the surface, having made 67 dives to the cruiser Edinburgh during the expedition. Stormy weather prevented work from continuing. The rest of the cargo - 34 ingots, was planned to be delivered next year.

However, the point in the rise of gold from Edinburgh was set only after 5 years. By that time, the consortium headed by Jessop had broken up and the contract to continue the work went to Warlton-Williams. On August 28, 1986, their ship Deepwater 2 went to the place of the upcoming dives. Between September 4 and 10, they managed to extract another 29 ingots. The remaining 5 bars of gold in the artillery cellar were not found and their fate is still unknown.

Several books and a film have been written about the cruiser of the British fleet "Edinburgh" and the gold on board, as well as about the process of extracting the "underwater treasure". This story has long attracted great attention society. In addition to purely mercantile interest, this operation is also very indicative from a technical point of view. The organization of the process of prospecting and underwater work, as well as the technologies and equipment used, made it possible to carry out an advanced operation at that time in a very short time, proving the possibility of such an operation at depths unattainable until that time.

Light cruiser Belfast is a copy of Edinburgh. Now-ship-museum.

Belfast next to USS Bataan. Korea. 1952

Belfast-class light cruisers:

Enlarged variant of the Gloucester-class cruisers. At an early stage of design, it was planned to arm these ships with 16 152-mm guns in four-gun turrets. In the course of work on the installations, the designers encountered a number of intractable problems and therefore the ships began to be built with already worked out three-gun turrets, but with reinforced armor and anti-aircraft weapons.

The armor belt was extended to the bow and stern to the end towers of the main caliber (on its predecessors it did not even reach the inner towers), the armored deck became thicker. The number of 102-mm twin installations was increased to six (the most a large number of on English cruisers), and instead of four-barreled eight-barreled "pom-poms" were mounted. Otherwise, the new cruisers differed little from their earlier counterparts (Southampton and Gloucester), although due to the transfer of the transverse catapult from the space between the chimneys forward (between the first chimney and the superstructure), they acquired a rather peculiar silhouette.

One of the shortcomings of these cruisers was the unfortunate location of the anti-aircraft artillery ammunition magazines, located too far from the installations themselves, so when one pair of anti-aircraft guns was removed at the end of the war, this practically did not weaken the ship's armament.

Only 2 units were built, Belfast and Edinburgh.

On April 8, 1942, the allied convoy PQ-14 left Reykjavik - it included 25 transports. They were protected by British ships. The cruiser "Edinburgh" from the 18th squadron of the British led the convoy.

In the spring of 1942, the Soviet government began to pay the Allies for Lend-Lease supplies. Soviet gold (93 boxes - 471 ingots of the highest 999 standard, with a total weight of 5.5 tons) was intended for the Americans as payment. They decided to send a particularly valuable cargo with the QP-11 convoy, believing that the route through the North Atlantic was the fastest and safest. Ingots under great secrecy and impressive security were delivered to Murmansk, where they waited for "Edinburgh". English sailors transferred the gold to the most protected place of the cruiser - to the artillery cellars. The boxes were placed on racks next to the ammunition...

Convoy QP-11 was formed in Arkhangelsk and Murmansk. On April 25, the first group of ships with escort left the Dvina roadstead. The next day, when the Edinburgh was taking gold on board, ships from the Kola Bay also went to sea. The cruiser sailed already on the night of April 27-28. He quickly overtook the slow-moving transports and took his place in the marching order.

On the morning of April 30, the Edinburgh left the convoy and went ahead 20-30 miles. The cruiser moved in the so-called wide anti-submarine zigzag at a speed of 18-19 knots. And yet, he was ambushed by the fascist submarine U-456 - one of the best in the 6th German flotilla. Its commander, Lieutenant Commander Max Teichert, was considered a master of "non-periscope attacks", and the Edinburgh was moving at insufficient speed to avoid evasion, and at 16.18 both torpedoes hit the cruiser. The first one hit the side exactly in the area of the midship frame. The explosion was the strongest! The engine room, communications center, generators, and main battery systems were out of order. A second torpedo exploded aft, blowing off the rudder and two propellers. At the same time, the iron decking of the quarterdeck reared up so that it blocked the view of the gunners of the stern guns.

But the cruiser remained afloat. From the "neighboring" position, the U-209 submarine rushed towards him. Another danger to the seriously wounded ship was the German destroyers of the Arktika group, which had come out to intercept the convoy.

After the explosions, "Edinburgh" took great amount water and got a roll of 25 degrees. The British acted both competently and selflessly. In the icy water, in the twilight of the premises, they managed to get patches, strengthen the bulkheads, turn on the pumps, and reduce the roll. In the lower rooms, people frantically tried to launch at least one - the right surviving - shafting, and the sailors cleared the upper deck so that the towing lines could be taken aft. The flow of outboard water was stopped. Then they gave electricity to the guns of the main caliber. 250 miles from the Kola Bay, the cruiser was preparing for her last battle.

Convoy QP-11 was nearby. Destroyers Forester and Foresight rushed from his guard to the aid of Edinburgh. They also attacked the Nazi submarine U-209. The commander of the destroyer "Forester" Haddard decided to ram the boat. The forged stem of the destroyer demolished her periscope. The boat moved away and lay down on the ground. A few hours later, three Soviet ships approached the Edinburgh - the destroyers Thundering and Crushing and the P-18 messenger ship. The sea was stormy, "Edinburgh" with great difficulty managed to be taken in tow. But early in the morning of May 1, both Soviet destroyers went to the base to refuel. Subsequently, this hasty retreat was interpreted by the British in their own way and even had serious consequences. Around the same time, they were replaced by TFR-28 Rubin, rescue tug No. 29, and four minesweepers of the 6th British Flotilla from Murmansk.

The Nazi destroyers entered the convoy on May 1 at 12.45. At this point, the numerical superiority was on the side of the British - 4 destroyers, 4 corvettes, minesweepers. But the three latest German EMs of the Narvik series surpassed the British in terms of firepower and rate of fire of guns, as well as in speed. Soviet destroyers could really help, but they were not. The fight turned out to be hot and lasted 5 hours.

First, the Germans tried to break through to the transports. One of the torpedoes hit the ship "Tsiolkovsky" - the only Soviet ship in the convoy. The ship quickly sank. The fascists could not achieve more. The British fought desperately. On the destroyer "Amazon" of the officers, only the second lieutenant survived. The destroyer Bulldog was also seriously damaged. He had broken all the stern guns. But the Nazis were forced to retreat. The guarded convoy moved into the ice, and part of the warships continued to escort the Edinburgh.

Early on the morning of May 2, the Germans launched a second attack. Now their main target was the damaged cruiser. Towing ropes were cut off on the Edinburgh, and the ship, deprived of a rudder, began to “write out circulations” at an 8-knot course. All his surviving guns opened fire on the enemy.

This time the battle lasted no more than three hours, but it was even more fierce. "Forester" was hit by a shell in the wheelhouse, the commander and 10 other team members died. The Foresight was hit four times, but only nine were killed. And another, already the third, torpedo hit the Edinburgh, and again - on the left side! The Nazis lost the destroyer Herman Shoemann. They say that it was the shells of the main caliber of the English cruiser that hit him.

Edinburgh was doomed. By 9 o'clock, his crew moved in an organized manner to the escort ships. No one could rule out the possibility of the Nazis capturing the Edinburgh after the withdrawal, and the destroyer Foresight fired its last torpedo at it. The cruiser, flying the flags of St. George and the city of Edinburgh, plunged into the abyss of the Barents Sea. Five and a half tons of gold fell to the bottom from the Edinburgh.

In 1981 Operation Edinburgh Gold began.

The fact that there was gold on board the wrecked cruiser Edinburgh soon ceased to be a secret. Information about it appeared in the English press immediately after the war, and since the 50s, talk began about a possible search for a cruiser with treasures on its boat. But how to do that? The ship sank at a depth of a quarter of a kilometer. In addition, the British government, in order to stop the possible claims of all sorts of adventurers, declared Edinburgh a military grave (after all, 57 sailors rested on it), and, therefore, he received complete immunity.

Nevertheless, the development of gold lifting projects did not stop. The most successful in this Englishman Keith Jessop. As an experienced diver who serviced drilling platforms in the North Sea, he was well versed in underwater technology, and in addition, he had the abilities of a historian-researcher. For more than 10 years, Jessop has been collecting all sorts of (sometimes contradictory) information about the last campaign of Edinburgh, until in 1979 he decided to organize a search expedition. The Norwegian company Stolt-Nielsen became his partner. Although the expedition did not bring concrete results, the search area was quite clearly defined. Especially valuable was the testimony of the captain of one trawler: debris fell into his net - it seems that from Edinburgh.

The following year, Jessop, together with a diving company from the city of Aberdeen, created his own company, Jessop Marine Recoveries (Jasson Marine Recovers). Intrigued by a solid jackpot, well-known corporations agreed to participate in his project - the English Racal-Decca and the West German OSA. The first provided the expedition with electronic and hydroacoustic equipment, the second provided the search vessel "Damptor" ("Dammtor"). By that time, Jessop had competitors: in the summer, the Droxford ship of the Risdon-Beasley company worked in the area of \u200b\u200bthe death of Edinburgh, but the results of its search remained unknown.

In early May 1981, the Damptor, equipped with the latest technology, set off for the Barents Sea. He was lucky: on the very first day of the search, the cruiser was discovered! Edinburgh lay on the port side at a depth of 250 m. With the help of video cameras, we even managed to shoot a short film.

The search ship returned to Kirkenes, from where Jessop urgently flew to Moscow, and from there to London. The result of the negotiations was the Soviet-British agreement, signed on May 5. The parties agreed that Jessop's firm bears all the costs of raising the gold itself and in case of failure, no compensation is due to it. If gold is raised, then, given that the work involves significant risk, Jessop Marin Recovery will receive 45% of the precious metal. The remaining 55% should be divided between the USSR and Great Britain in a ratio of approximately 2:1, since the Soviet Union received insurance in the amount of 32.32% of the value of gold paid by the British War Risk Insurance Bureau during the war years. Accordingly, this percentage of the precious cargo lying at the bottom automatically became the property of the British.

Responding to the protests of veterans of the "Russian convoys" who demanded not to disturb the remains of the dead sailors, Jessop said that the gold would be lifted through a torpedo hole in the starboard side and all other premises of the cruiser would remain intact.

During June, the second stage of the operation began - the training of super-aquanauts. First of all, the divers had to explore the "mazes" of the sunken cruiser, so as not to get lost in its many rooms and corridors. Of the Belfast-class cruisers, to which Edinburgh belonged, Belfast, an exact copy of Edinburgh, fortunately survived. The cruiser stood on the Thames as a museum ship of the history of the British Navy. Its premises have not undergone major reconstruction, and therefore the divers used them as "simulators". Classes were conducted very intensively, and they “learned by touch” their intended path from the side hole to the artillery cellars.

In August, the expedition received a new vessel, the Stephaniturm, purchased by OSA. Previously, it served drilling platforms in the North Sea, for which it was equipped with pressure chambers for 10 divers, a deep-water bell, powerful winches and other equipment.

The main work began in September. An attempt to penetrate the cellar with gold through a torpedo hole was unsuccessful - the path was blocked by twisted metal structures and a huge number of rusted shells. I had to cut through an additional hole and look for a way to the target through fuel tanks. The divers worked extremely difficult conditions; many of them complained of malaise, which is not surprising - work at such a depth was carried out for the first time in history.

Diver John Rossier, a native of Zimbabwe, was lucky to discover the first 11.5-kg gold bar. It happened on September 16th. The mood of the participants in the operation rose sharply, and they set to work with redoubled energy. Over the next three weeks, 431 ingots of gold with a total weight of about 5.13 tons (more precisely, 5,129,295.6 g) were raised to the surface. There were still 34 ingots left on the Edinburgh, but worsening weather and extreme fatigue of the divers forced Jessop to stop work on October 7th. A day later, Stephaniturm arrived in Murmansk. The total value of the extracted gold amounted to more than 40 million pounds. Art.

The remaining valuables were lifted from the bottom of the sea only after 5 years. Although there were still 375 kg of gold on board the cruiser, Jessop's consortium fell apart: his partners felt that the upcoming expenses might not pay off. In the end, the English businessman sold the Soviet-British contract to his competitors, Warlton-Williams.

On August 28, 1986, the new, well-equipped ship Deepwater 2 left the Scottish port of Peterhead and headed for the Barents Sea. Within two weeks, 29 ingots were found and raised to the surface. The last 5 were never found: probably, during the explosion or capsizing of the cruiser, they fell into the neighboring compartments of the left side, where it turned out to be unrealistic to find them among the ammunition scattered everywhere. On September 18, Deepwater 2 returned to its native shores, while the gold was divided between the USSR and Great Britain in the same proportion.

Who cares - the movie is here

A loud sensation that erupted in South Korea in connection with the discovery of the sunken Russian cruiser "Dmitry Donskoy", on board which is allegedly carrying a cargo of gold worth 135 billion dollars, apparently, will end in nothing. Russian experts involved in the history of the Russian navy agree that the “golden cargo” of the Dmitry Donskoy is a myth that has no basis.

Meanwhile, more than 30 years ago, the gold cargo, which is directly related to our country, was indeed raised from a sunken warship.

Secret cargo in payment for Lend-Lease

At the beginning of the Great Patriotic War northern sea convoys were transported to Murmansk from the UK as part of Lend-Lease deliveries military equipment, weapons and other goods needed by the USSR. Not everyone knows that there was also a “reverse lend-lease”: valuable raw materials and gold were brought from the Soviet Union to pay for military supplies.

On April 28, 1942, together with convoy QP-11, the British light cruiser Edinburgh left Murmansk for England. Only the senior officers of the cruiser knew about the special cargo taken on board in Murmansk: 93 wooden boxes containing 465 gold bars with a total weight of 5536 kg.

On April 30, 1942, the Edinburgh, somewhat detached from the caravan ships, was attacked by the German submarine U-456. The cruiser received two torpedoes: one hit the port side, the second hit the stern. "Edinburgh" lost speed, but remained afloat.

Flooding so that the enemy does not get

The ship was 187 miles from Murmansk. After two British destroyers approached, it was decided to try to return to the Soviet port. However, German destroyers soon appeared, intending to finish off the Edinburgh.

In the ensuing battle, the German destroyer German Sheman was sunk. But the Edinburgh, which received new damage, finally lost its course. By order of the British command, the crew of the ship moved to other ships, and the cruiser itself was shot by British destroyers and went to the bottom. This decision was made so that the Nazis did not get the valuable cargo.

The gold aboard the Edinburgh was insured: 2/3 in the USSR State Insurance, 1/3 in the British War Risk Insurance Committee.

During the war years and the first decades after the war, there was no technology to lift gold from the Edinburgh. But the gold cargo became widely known, and the cruiser remained among the potential targets of treasure hunters.

Agreement with Mr. Jessop

The difficulty was that those wishing to lift the cargo had to negotiate with both the government of the USSR and the government of Great Britain, because, among other things, the place of death of the Edinburgh was declared a military burial place: 57 dead British sailors remained on board.

In 1979, a British diver and adventurer Keith Jessop conducted an expedition to more accurately determine the place of the death of the ship. Jessop had not previously been involved in underwater treasure hunting, but he collected almost all available information on the Edinburgh and was convinced that he would be able to raise a valuable cargo.

Keith Jessop was a sociable, open and good-natured person. He managed to win over the members of the Soviet delegation that arrived in Britain for negotiations. Moscow received a report: Jessop is not an adventurer or a spy, you can work with him.

In April 1981, representatives of the USSR and Great Britain entered into an agreement with the private firm Jessop Marine Recoveries. All expenses for the operation fell on Keith Jessop and his companions. If successful, the treasure hunt team received 45 percent of the raised gold. The remaining 55 percent was divided between the USSR and Great Britain: 2/3 - to Moscow, 1/3 - to London. This proportion was based on the amount of insurance payments of the parties.

"I found him! I found gold!

Work began on May 9, 1981. Five days later, the rescue ship Dammator found the cruiser at a depth of 250 m. It lay at the bottom on the port side. After establishing the exact location of the "Edinburgh", preparations began for the operation to raise the gold.

In August 1981, the ship "Stefaniturm" set off for the work area, equipped with equipment that allows divers to work at depths of up to 400 meters.

The most experienced divers involved in the operation lived in special pressure chambers in the hold and descended to the cruiser in pairs in a special diving bell. This approach saved a lot of time, eliminating the cost of daily decompression procedures.

The operation was difficult. At first it turned out that getting inside the vessel through holes in the board would not work: it turned out to be too dangerous for divers. I had to cut a special hole in the case. Then it took another ten days to clear the rubble on the way to the artillery cellar, where the boxes of gold were supposed to be.

Time passed, people got tired more and more, but there was no result. But one day a twenty-seven-year-old diver from Zimbabwe John Rossier shouted into the microphone: “I found it! I found gold! The first precious ingot was raised to the surface.

big jackpot

From the layers of silt and fuel oil, they began to get one ingot after another by touch. Over the next 19 days, 431 gold bars with a total weight of 5129.3 kg were lifted from the Edinburgh.

On October 5, 1981, work was suspended. The weather finally deteriorated, and the divers, despite their enthusiasm, were mortally tired. Keith Jessop reasoned that there was no point in risking further. Four days later, the ship "Stefaniturm" came to the port of Murmansk with raised gold.

It was a worldwide sensation. Jessup's team managed to carry out the most successful operation in the history of underwater treasure hunting. Gold raised from the bottom of the Barents Sea, "pulled" 81 million dollars. $35 million was paid to Keith Jessup's firm.

Unique exhibit

The treasure hunter intended to return for the remaining ingots in a year. However, soon the British decided to switch to searching for sunken Spanish galleons in the Caribbean.

The contract for further work was transferred to the English company Warlton-Williams. There was information that the "Edinburgh" could carry not 5, but 10 tons of gold. However, the 34 bars of gold that Keith Jessop's divers did not raise were also worth organizing a new operation.

Ultimately, the expedition to the "Edinburgh" was carried out in the autumn of 1986. Rumors of another five tons of gold were not confirmed. The divers got 29 ingots with a total weight of 345.3 kg. Finding five more ingots proved impossible. They remained somewhere at the bottom of the Barents Sea.

One of the ingots received Soviet Union, is now on display at the Diamond Fund of Russia, reminding of this unique history.