Boyar children, as a class, formed at the beginning of the 15th century, were initially not very large estate owners. They were "assigned" to this or that city and began to be attracted by the princes for military service. Later, the boyar children were divided into two categories. Yard children of the boyars - initially served as part of the Sovereign (grand princely) court or transferred to it from the courts of specific princes. Boyar city children, who initially served the specific princes, were assigned to a particular city. A clear difference between these categories took shape by the 30-40s of the 16th century. Yard children of the boyars received higher salaries. In the second half of the 16th century, they occupied an intermediate position between city and elected boyar children. The urban children of the boyars made up the majority. At the beginning of the 16th century, cities belonged to the Moscow and Novgorod categories, and in the second half, such groups of cities as Smolensk, Seversk, Tula and Ryazan stood out from Moscow.

The nobles were formed from the servants of the princely court and at first played the role of the closest military servants of the Grand Duke. Like the children of the boyars, they received land plots for their service. In the first half of the 16th century, the nobles, together with the yard children of the boyars, made up a special Sovereign Regiment. At first, the nobles in the documents were lower than the children of the boyars, as a special group, they stand out only in the middle of the 16th century. There were also urban nobles. They were formed from servants of specific princes and boyars and were provided with estates far from Moscow.

Reforms of Ivan the Terrible

In 1552, the regiments of the local cavalry received a hundred structure. Hundreds were commanded by hundreds heads.

During the reign of Ivan the Terrible, elected nobles and boyar children appeared, who carried out both domestic and city service. The elected children of the boyars were replenished from among the courtyards, and the courtyards, in turn, from among the city.

In 1564-1567, Ivan the Terrible introduced the oprichnina. The service people were divided into oprichniki and zemstvos, and counties were divided in the same way. Oprichnina implemented the idea of "The Chosen Thousand". In 1584, the oprichny court was liquidated, which led to a change in the structure of the sovereign's court.

Residents, Moscow nobles, solicitors and stolniks belonged to the Moscow service people. Them total number in the 16th century it was 1-1.5 thousand people, by the end of the 17th century it increased to 6 thousand.

The most senior command positions were occupied by duma ranks - boyars, roundabouts and duma nobles. Their total number as a whole was no more than 50 people.

Time of Troubles

Time of Troubles led to the crisis of the local system. A significant part of the landlords became empty and could not receive support from the peasants. In this regard, the government took measures to restore the local system - paid salaries, introduced benefits. By the second half of the 1630s, the combat capability of the local troops was restored.

Romanov reforms

At the same time, during the reforms of the army, a duality arose in its structure, since initially the basis of the armed forces of the Kingdom of Russia was precisely the local army, and the rest of the formations were dependent on it. Now they received independence and autonomy as part of the armed forces, and the cavalry of the hundredth service became one with them. During the military district reform of 1680, the ranks (military districts) were reorganized and the structure of the Russian armed forces was finally changed - in accordance with these ranks, rank regiments were formed, which now included the local cavalry.

In 1681, a reform of the organization of Moscow service people was launched. It was decided to leave them in the regimental service, but reorganize from hundreds into companies (60 people each) led by captains; and regiments (6 companies per regiment). For this, localism had to be abolished in 1682.

Liquidation

local army was abolished under Peter I. At the initial stage of the Great Northern War, the noble cavalry, under the leadership of B.P. Sheremetev, inflicted a number of defeats on the Swedes, however, her flight was one of the reasons for the defeat in the Battle of Narva in 1700. AT early XVIII centuries, the old noble cavalry, along with the Cossacks, still figured among the regiments of the equestrian service and took part in various hostilities. 9 such regiments are known. In particular, the ertaul regiment of Ivan Nazimov was formed in 1701 from Moscow ranks and servicemen of the regimental and hundred service of the Novgorod category, then transformed into a Reiter regiment, and disbanded in 1705. The regiment of Stepan Petrovich Bakhmetyev was formed in 1701 from servicemen of the regimental and hundred service, as well as archers and Cossacks from lower cities, and was disbanded in 1705. The regiments of Lev Fedorovich Aristov and Sidor Fedorovich Aristov were formed in 1701 from servicemen of the regimental and hundred service of the Kazan category, disbanded by 1712. The regiment of Bogdan Semyonovich Korsak, formed from the Smolensk gentry, retained the organization of the hundred service regiments and the militia structure during the first quarter of the 18th century. As a result of the transformation of the army, a significant part of the aristocrats was transferred to the dragoon and guard regiments, many of them were officers.

Structure

In the second half of the 16th century, the following structure of service people in the fatherland, who made up the army, was formed:

- Duma ranks

- roundabout

- Moscow ranks

- Stolniki

- Solicitors

- City ranks

This structure was finally formed, probably, after the abolition of the oprichnina. As a rule, the most noble aristocrats could become stolniks. From this rank, the children of the boyars, okolnichy, Moscow nobles began their service, or they transferred to it after being in the rank of solicitor. Stolniki, at the end of their service, moved to the duma ranks or to the rank of Moscow nobles. In the rank of a solicitor, they either started the service, or transferred to it after being in the rank of a tenant. The tenants, as a rule, were the children of elected nobles, less often - Moscow nobles, clerks, streltsy heads, sometimes prominent palace figures, and also, perhaps, the best courtyard children of the boyars. At the end of the service, the tenants, as a rule, moved to the "choice of cities", but sometimes they could become solicitors or Moscow nobles. As a rule, representatives of the princely-boyar nobility served in the rank of Moscow nobles, and in some cases elected nobles rose to the rank; and served all their lives, except for those cases when they could move to the duma ranks or, due to disgrace, go down to "choice from the cities." In the rank of elected nobles, children of elected and Moscow nobles could begin their service. Before the "choice" often, after a long service, yard children of the boyars, and in exceptional cases - the city's children, could reach the rank. Residents who had served in the palace service, lowered as a result of disgrace, Moscow nobles, clerks, and solicitors were transferred to the “choice”. Elected nobles, most often, served in this rank for the entire service, but sometimes they could move to the Moscow ranks.

From representatives of the Duma ranks, large regimental and simply regimental governors were appointed, they were also sent as governors to border cities. The most honored boyars could be appointed commanders of the entire army. Part of the Moscow service people in war time was part of the Sovereign regiment, while others were sent to other regiments, where they, together with the elected nobles, held the positions of governor, their comrades, heads. When distributing posts, local seniority was taken into account. It is also characteristic that the main duties of the Duma and Moscow officials were considered service at court, and military appointments were considered additional "parcels". Localism also played a role among urban service people - it depended on the category (the cities of the Novgorod category followed the Zamoskovye cities, as well as the cities of southern Ukraine) and the order within the category.

population

It is impossible to establish the exact number of local troops in the 16th century. A. N. Lobin estimates the total number of the Russian army in the first third of the 16th century to 40,000 people, taking into account the fact that its main part was the local cavalry. By the middle of the century it increases, in the last quarter it decreases. In the Polotsk campaign of 1563, according to his estimate, 18,000 landowners took part, and together with combat serfs - up to 30,000 people. V.V. Penskoy considers these estimates to be underestimated and limits the upper limit of the number of local troops in the first half of the 16th century to 40,000 landowners and combat serfs, or 60,000, taking into account other servants. O. A. Kurbatov, pointing out the advantages and disadvantages of the work of A. N. Lobin, notes that such a calculation of the upper estimate of the number is incorrect due to too large an error. At the end of the 16th century, according to S. M. Seredonin, the number of nobles and boyar children did not exceed 25,000 people. The total number, together with serfs, according to A. V. Chernov, reached 50,000 people.

In the 17th century, the number of troops can be accurately determined thanks to the surviving "Estimates". In 1632 there were 26,185 nobles and boyar children. According to the "Estimate of all service people" of 1650-1651, there were 37,763 nobles and boyar children in the Moscow state, and the estimated number of their people was 40-50 thousand. By this time, the local army was being forced out by the troops of the new system, a significant part of the local troops were transferred to the Reitar system, and by 1663 their number had decreased to 21,850 people, and in 1680 it was 16,097 people of the hundred service (of which 6385 were Moscow ranks) and 11 830 of their people.

Mobilization

In peacetime, the landowners were on their estates, and in case of war they had to gather, which took a lot of time. Sometimes it took more than a month to fully prepare the militia for hostilities. Nevertheless, according to Perkamota, at the end of the 15th century, it took no more than 15 days to raise an army. From the Discharge Order to the cities, voevodas and order clerks were sent tsar's letters, in which they indicated to the landowners that they were preparing for a campaign. From the cities, they, with collectors sent from Moscow, acted to the place of collection of troops. Each collector in the discharge order was given a list of service people who were supposed to participate in the campaign. They informed the collector of the number of their serfs. According to the Code of Service 1555-1556. a landowner from 100 quarters of the earth had to bring one armed person, including himself, and according to the Council's verdict of 1604 - from 200 quarters. Together with combat serfs, it was possible to take with them kosh, convoy people. The landlords and their people came to the service on horseback, often with two horses. Depending on the wealth of the landowners, they were divided into various articles, from which the requirements placed on them and the nature of the service depended. On mobilization, servicemen were distributed among the voivodship regiments, and then "signed in hundreds." When painting or later, selected units were formed.

They went on a hike with their food. Herberstein wrote about the reserves on the campaign: “Perhaps it will seem surprising to some that they support themselves and their people on such a meager salary, and, moreover, as I said above, for such a long time. Therefore, I will briefly speak about their thrift and temperance. He who has six horses, and sometimes more, uses only one of them as a lifting or pack horse, on which he carries the necessities of life. This is first of all millet powder in a bag two or three spans long, then eight or ten pounds of salted pork; he also has salt in his bag, and if he is rich, mixed with pepper. In addition, everyone carries with him an ax, flint, kettles or a copper vat on the back of his belt, and if he accidentally gets into a place where there are no fruits, no garlic, no onions, no game, then he makes a fire, fills the vat with water, throws a full spoonful of millet into it, add salt and cook; contented with such food, both the master and the slaves live. However, if the master gets too hungry, he destroys all this himself, so that the slaves sometimes have an excellent opportunity to fast for two or three whole days. If the master desires a luxurious feast, then he adds a small piece of pork. I'm not talking about the nobility, but about people of average means. The leaders of the army and other military commanders from time to time invite others who are poorer to their place, and, having had a good meal, these latter then abstain from food, sometimes for two or three days. If they have fruits, garlic or onions, then they can easily do without everything else.. Directly during the campaigns, expeditions were organized to obtain food in enemy territory - "pens". In addition, during the "corrals" sometimes captives were captured with the aim of sending them to the estates.

Service

Tactical formations

In the first half of the 16th century, a marching army could include many different governors, each of which commanded from several dozen to several hundred fighters. Under Ivan the Terrible in 1552, a hundred structure was introduced, which made it possible to streamline the combat command and control system.

The main tactical unit since the middle of the 16th century has been a hundred. Hundred heads represented the younger command staff. They were appointed governor of the regiment from elected nobles, and from the Time of Troubles - and simply from experienced boyar children. The number of hundreds was usually 50-100 people, occasionally more.

To perform specific tasks, a "light army" could be formed. It was reduced from hundreds, possibly selected ones, who stood out 1-2 from each regiment of the entire army. A connection of 1000-1500 boyar children in the first half of the 16th century, as a rule, was divided into 5 regiments, each of which had 2 governors. Since 1553, it began to be divided into 3 regiments - Big, Advanced and Watchdog, also 2 governors each. Each voivodship regiment had from 200 to 500 soldiers.

The entire army in the campaigns was originally divided into the Big, Front and Guard regiments, to which the regiments of the Right and Left hands could be added, and in the case of the Sovereign's campaign, the Sovereign's Regiment, Yertaul and the Big Outfit (siege artillery) could also be added. In each of them, several (2-3) voivodship regiments stood out. If at first the names of these regiments corresponded to their position on the battlefield, then during the 16th century only their numbers and the local seniority of the governors commanding them began to depend on them; Together, these regiments rarely gathered in a common battle formation, since the conduct of battles with the participation of a significant number of people did not correspond to the Moscow strategy. For example, in 1572, during the attack of the Tatars, the regiments of the Russian rati, hiding behind the gulyai-city, in turn, in order of seniority, made sorties from there. The number of regiments was different, according to available data, the Big Regiment was almost 1/3, right hand- a little less than 1/4, Advanced - about 1/5, Guard - about 1/6, Left hand - about 1/8 of the total number. The total number of rati in some campaigns is known from the bit paintings. In particular, in the campaign of I. P. Shuisky against Yuryev in 1558, it was 47 hundreds, the coastal army of M. I. Vorotynsky in 1572 was 10,249 people, and the army of F. I. Mstislavsky in the campaign against False Dmitry in 1604 - 13,121 people.

Service types

In the second half of the 16th century, the service was divided into city (siege) and regimental. Regimental, in turn, included long-range and short-range services.

The siege service was carried "from the ground" by small people. It was also transferred to those who could no longer, due to old age, illness, and injuries, carry out regimental service; in this case, part of the estate was taken from them. Monetary salaries were not supposed to be in the siege service. Small nobles and boyar children could be transferred to regimental service for good service, endowed with monetary and additional local salary. In some cases, veterans could be completely removed from service.

Distant, marching service meant direct participation in campaigns. Near (Ukrainian, coastal) was reduced to the protection of borders. Low-income nobles and boyar children could be involved in the security service. The middle locals, “who would people be horses, and young, and frisky, and proselyte,” carried out the stanitsa service; the wealthiest were appointed commanders and bore the main responsibility. The serif service consisted in the protection of serif features. The stanitsa service consisted in patrolling the cavalry detachments of the border territory, which, if enemy detachments were found, were supposed to notify the governor. The detachments served in shifts. The “Boyar verdict on the village and guard service” of 1571 for unauthorized leaving the post provided for the death penalty.

Supply

In the second half of the 15th century, the formed army was mainly supplied with estates in the recently annexed Novgorod lands, as well as in other annexed principalities. The landowners were supplied with lands confiscated from the disgraced specific princes and boyars, and partly from the free peasant communities. Yard children of the boyar and grand ducal nobles were located near Moscow. In addition, at the end of the 15th century, scribe books were compiled, which assigned part of the peasants to the landowners; and also introduced St. George's Day, limiting the right to transfer peasants from one landowner to another. Later, the Pomestny Prikaz was organized, which was responsible for the distribution of estates.

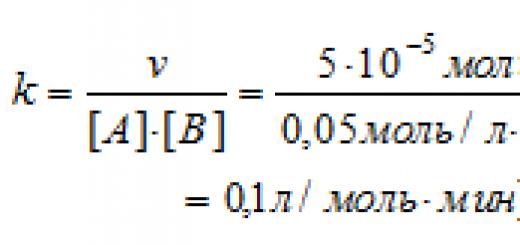

Since 1556, a system of reviews was organized, at which, among other things, children of landowners, novices, who were fit for it by age (from the age of 15), were registered for service. To do this, Duma people with clerks (in some cases, local governors performed their role) came from Moscow to the cities, who organized the election of salaries from local landowners. These salaries helped distribute newcomers to articles depending on their origin and property status. As a result, newcomers were enrolled in the service, assigned land and monetary salaries and recorded in verstal tithes. The salary of novices depended on the article and in the second half of the 16th century fluctuated, on average, from 100 to 300 quarters and from 4 to 7 rubles. People from the lower classes were not allowed to serve in the local army, however, on the southern borders, and later in the Siberian lands, exceptions sometimes had to be made. Since 1649, the layout has changed. According to the Code, children were now considered fit for service from the age of 18 and were enrolled in the boyar city children, and not in the rank of their father. In addition, relatively poor people could be recorded in new system. In some cases, data people were also allowed to be exhibited. The salaries of novices in the second half of the 17th century ranged from 40 to 350 quarters and from 3 to 12 rubles a year.

The Swedish diplomat Petrei reports the following about the parades: “The review is not the same with us and other peoples, when they review, all the colonels converge in one yard, sit in a hut by the window or in a tent and call the regiments to them one by one, a clerk stands next to them, calling each by name according to the list in his hands, where they are all written down, everyone should go out and introduce himself to the inspecting boyars. If there is no one available, the clerk carefully writes down his name until further notice; they do not ask if there are servants, horses, weapons and weapons with him, they only ask him himself. .

Information about service people was recorded in collapsible and distributing dozens. This information, determined at the reviews, included the number of combat servants of the landowner, weapons, cavalry, and salaries. Depending on this, money was paid. Dozens of reviews were sent to the Discharge Order, and lists from them - to the Local. The discharge order in tenths also recorded information about the participation of soldiers in hostilities, changes in salaries, noted capture and death.

The average salary in the second half of the 16th-17th centuries ranged from 20 to 700 quarters of land and from 4 to 14 rubles a year. The local salary of urban boyar children ranged from 20 to 500 quarters, yard children - from 350 to 500, elected - from 350 to 700. The salary of Moscow officials, for example, Moscow nobles, was up to 500-1000 quarters. and 20-100 rubles salary. Salary of Duma ranks: the boyars received from 1000 to 2000 quarters. and from 500 to 1200 rubles, roundabouts - 1000-2000 quarters. and 200-400 rubles, duma nobles - 800-1200 four. and 100-200 rubles. Estates for special merits, for example, for a siege seat, could be given out as a fiefdom. Among the Moscow service people, the number of votchinniks was quite large.

From the second half of the 60s of the 16th century, the lack of land suitable for use led to the redistribution of estates. Surplus estates and allotments of landowners who evaded service began to be confiscated and given to others. This resulted in estates sometimes having several parts. In connection with the flight of peasants and the increase in the number of wastelands, in some cases only one part of the estate salary was full-fledged land with peasant households, and the other was issued in the form of wastelands. Therefore, the landlords received the right to search for inhabited lands themselves. In the 17th century, due to the lack of suitable land, the real estate of many city people was less than the salary, which was especially evident on the southern borders. For example, according to the analysis of 1675 and review of 1677, 1078 nobles and children of the boyar southern cities had 849 peasant and bobyl households. The average estates there were 10-50 quarters.

Combat capability

In addition to the long collection, the local army had a number of other shortcomings. One of them was the lack of systematic military training, which negatively affected his combat capability. The armament of each person was at his discretion, although the government made recommendations in this regard. In peacetime, the landowners were engaged in agriculture and participated in regular reviews, which tested their weapons and combat readiness. Another important disadvantage was non-appearance and flight from the service - "absence", which was associated with the ruin of estates or with the unwillingness of people to participate in a particular war (for example, due to disagreement with government policy). It reached its peak in the Time of Troubles. So, from Kolomna in 1625, out of 70 people, only 54 arrived. For this, their estate and monetary salary was reduced (with the exception of good reasons for not appearing - illness and others), and in some cases the estate was completely confiscated. In the event of an unsuccessful turn of the battle, those hundreds who did not take any part in the battle sometimes turned to flight, as happened, for example, near Valki in 1657 or at Narva in 1700. Most of his defeats were associated with this property of the local cavalry. However, in general, despite the shortcomings, the local army showed high level combat capability. People learned the basic fighting techniques from childhood, because they were interested in the service and prepared for it; and their skill was reinforced by direct combat experience. Separate defeats, as a rule, were not associated with the weakness of the troops, but, except for cases of retreat without a fight, with the mistakes of the governor (as in the Battle of Orsha in 1514 or in the Battle of the Oka in 1521), the suddenness of the enemy attack (Battle on the Ule River (1564)) , the overwhelming numerical superiority of the enemy, the unwillingness of people to fight (as in the Klushinsky battle of 1610, in which the army, unwilling to fight for Tsar Vasily IV, dispersed without taking part in the battle). And the courage of warriors in battles was encouraged. For example, the Ryazan centurion head Mikhail Ivanov, who in the battle of 1633 "beat and wounded" many Tatars, and captured two and "smashed off a lot", and his horse was shot from a bow - 50 quarters were added to the former 150 and 2 rubles salary to the former 6, 5 rubles for commanding a hundred, "yes, two rubles from the tongue, and good cloth." Information about the participation of military people in each battle was entered in the track records.

Tactics

Local cavalry tactics were based on speed and formed under Asian influence in the middle of the 15th century. “Everything they do, whether they attack the enemy, pursue him or flee from him, they do suddenly and quickly. At the first collision, they attack the enemy very bravely, but they do not last long, as if adhering to the rule: Run or we will run.- wrote about the Russian cavalry Herberstein. Initially, its main purpose was to protect Orthodox population from raids, mainly by the Turkic peoples. In this regard, coastal service has become the most important task of military people and a kind of school for their combat training. In this regard, the main weapon of the cavalry was a bow, and melee weapons - spears and sabers - played a secondary role. Russian strategy was distinguished by the desire to avoid major clashes that could lead to losses; preference was given to various sabotage from fortified positions. To counter the Tatar raids, it was required high degree interaction and coordination of actions of reconnaissance and combat detachments. In the 16th century, the main forms of combat were: archery, "baiting", "attack" and "removable battle" or "great slash". Only the forward detachments took part in the "baiting". During it, an archery fight began, often in the form of a steppe “carousel” or “round dance”: detachments of Russian cavalry, rushing past the enemy, carried out his massive shelling. In the battle with the Turkic peoples, the mutual skirmish could last "for a long time." Archery was usually followed by a "push" - an attack using contact melee weapons; moreover, the beginning of the attack could be accompanied by archery. In the course of direct clashes, multiple "launches" of the detachments were made - they attacked, in case of the enemy's stamina, they retreated in order to lure him into pursuit or give room for the "launch" of other detachments. In the 17th century, the methods of combat of the local army changed under Western influence. During the Time of Troubles, it was rearmed with "driving squeakers", and after the Smolensk War of the 30s - with carbines. In this regard, "shooting combat" from firearms began to be used, although archery combat was also preserved. From the 1950s and 1960s, cavalry attacks were preceded by a volley of carbines.

Ertauls (also called ertouly, yartauls), first mentioned in the middle of the XVI century. They were formed either from several hundreds of equestrians, or from the best fighters selected from different hundreds, and sometimes from the voivodship retinue. Ertauls went ahead of the whole rati and performed reconnaissance functions, usually they were the first to enter the battle, they were assigned the most responsible tasks, therefore, they required a speed of reaction and high combat capability. Sometimes ertaul made a false flight, leading the pursuing enemy into an ambush. In case of victory, as a rule, it was Ertaul who pursued the defeated enemy. However, even if the main part of the army went into pursuit, the governors and heads tried to keep control of hundreds under their control, since it might be necessary to conduct a new battle or take enemy fortifications. Pursuits were generally carried out with great discretion, as a retreating enemy could lead into an ambush, as happened at the Battle of Konotop.

In the second half of the 16th century, the practice developed in the event of a defeat to gather in field fortifications, however, the main part of the cavalry was dispersed over the area. Since the Time of Troubles, those who did not return to the fortifications began to be punished. It is possible that by the end of the Time of Troubles, the appearance of "withdrawal detachments" consisting of one or several hundred (although the term "withdrawal" itself has been known since the 16th century) dates back to the end of the Time of Troubles. The tasks of these detachments included, in case of defeat, to launch an attack on enemy units, which made it possible to disrupt the pursuit of our troops and ensure an organized retreat. Due to the important role of the withdrawal, it was formed from the elite of the local army, and from the 60s of the 17th century - sometimes from the cavalry of the new system. At the same time, since the 1950s, the need for withdrawal has been falling - the infantry began to play its role. At the same time, with the decrease in the role of the local army and due to its low ability for linear combat, it began to perform the tasks of an ertaul and withdrawal in the second line of the main formation. The local cavalry acted as a withdrawal, for example, in the battle on the river. Basho 1660, saving the pursued reiters with a counterattack.

In the 1570s-1630s, cavalry detachments of serving foreigners sometimes advanced ahead of the troops.

The plan of battle, as a rule, was developed by governors and heads at the council, where the battle order, the course of the battle and conditional signals were discussed. For this, intelligence data was used - "entrances" and "passing villages", which, as a rule, stood out from the ertaul or the entrance of a hundred. Based on the alleged plans of the enemy, the governors either attacked or went on the defensive. When attacking, they tried to attack unexpectedly, "unknown". In 1655, near Vitebsk, such an attack, organized by Matvey Sheremetyev, made it possible to break the numerically superior Lithuanian detachment. During the Tatar raids, the Russian cavalry tried to attack when they scattered across the territory in order to search for prey and captives. If the governors decided to attack the enemy, who was in a good position, then the forward detachments would start a fight until the main forces approached for a frontal attack; or until ways are found to attack from the rear or flank. However, attacks from the flanks were carried out mainly in defensive battles. The role of the base during field battles was often played by walking cities, covered by infantry and artillery. They were sometimes targeted by pursuing enemy troops with the help of a false flight, which fell into a fiery ambush.

The command and control system of troops was largely formed under the influence of the Timurid states. Voivodship orders were transmitted by special captains from young boyar children. The banners served to indicate the location of the voivode and the voivodeship headquarters, and horse hundreds. Hundreds of banners, at least in the 17th century, were sent to the voivodship regiments from the capital for each campaign and distributed in hundreds, and upon dissolution, the troops were sent back; therefore, the banner's ownership was unknown to the enemy. The standard-bearers followed the commander of a regiment or a hundred, and the entire detachment followed the banner. Conditional signals were also given by banners or bunchuks. Sound signals, called "yasaki", served to indicate the "launch", as well as the collection of troops at the end of the battle and for other purposes. Musical instruments were at the voivodship and royal camps, they included: tulumbas or tambourine, “big alarm” (drums); nakras, timpani; surnas. There were also "yasak calls". This system of government in the second half of the 17th century, under Western influence, is gradually falling into disuse.

Armament

Equipment of a Russian warrior of the middle of the 16th century. Engraving from the Basel edition of Herberstein, 1551.

The landlords armed themselves and armed their people at their own expense. Therefore, the complex of armor and weapons of the local army was very diverse, and, in general, in the 16th century it corresponded to the West Asian complex, although it had some differences, and in the 17th century it changed noticeably under Western influence. The government sometimes gave orders in this regard; and also checked the armament at the reviews.

Steel arms

The main bladed weapon was the saber. Mostly they were domestic, but imported ones were also used. West Asian damask and Damascus sabers were especially valued. According to the type of blade, they are divided into massive kilichi, with a bright yelman, and narrower sabers without yelman, which include both shamshirs, and, probably, local Eastern European types. During the Time of Troubles, Polish-Hungarian sabers became widespread. Occasionally konchars were used. In the 17th century, broadswords were distributed, although not widely. Additional weapons were knives and daggers, in particular, a sabot knife was specialized.

The noble cavalry, right up to the Time of Troubles, was widely armed with axes - they included axes-chasers, axes-maces and various light "axes". Clubs cease to be common by the middle of the 15th century, and by that time only beams are known. In the 17th century, pear-shaped maces, associated with Turkish influence, gained some distribution, however, like buzdykhans, they had a predominantly ceremonial significance. Throughout the entire period, warriors were armed with pernachs and shestoperami, however, it is difficult to call them widespread weapons. Tassels were often used. Coins and klevets were used, which became widespread under Polish and Hungarian influence in the 16th century (possibly in the second half), however, not very wide.

Bow with arrows

The main weapon of the local cavalry from the end of the 15th to the beginning of the 17th centuries was a bow with arrows, which was worn in a set - saadake. These were composite bows with highly profiled horns and a clear central handle. For the manufacture of bows, alder, birch, oak, juniper, aspen were used; they were supplied with bone overlays. Master archers specialized in the manufacture of bows, saadaks - sadachniks, arrows - archers. The length of the arrows ranged from 75 to 105 cm, the thickness of the shafts was 7-10 mm. Arrowheads were armor-piercing (13.6% of finds, more common in the northwest and losing their wide distribution in the middle of the 15th century), dissecting (8.4% of finds, more often in the area of "German Ukraine") and universal (78%, moreover , if in the XIV-XV centuries they accounted for 50%, then in the XVI-XVII - up to 85%).

Firearms

Defensive weapons

Notes

- Kirpichnikov A. N. Military affairs in Rus' in the XIII-XV centuries. - L.: Nauka, 1976.

- Chernov A.V. Armed forces of the Russian State in the XV-XVII centuries. (From the formation of a centralized state to the reforms under Peter I). - M .: Military Publishing House, 1954.

The process of unification of Russian lands, which began in the 14th century, was completed by the end of the 15th century. formation of a centralized state. Since that time in Rus' it has been developing local picking system troops. The system received this name because of the distribution of land (estates) to service people (nobles, boyar children, etc.), who were obliged to serve the sovereign for this.

The transition to this recruiting system was determined to a decisive extent by economic reasons. As the armed forces increased, the question of their maintenance arose. The resources of the country with subsistence farming were very limited, but the Russian state had a significant territory.

Unlike the boyar, patrimonial lands, which were inherited, the nobleman owned the estate (land) only during his service. He could neither sell it nor pass it on by inheritance. Having received the land, the nobleman, who usually lives on his estate, had to appear at the first request of the sovereign at the appointed time with a horse, weapons and people.

Another source of replenishment of the local army was the princes and boyars, who came to the service with their detachments. But their service to the Grand Duke in the XV century. lost its voluntary character, becoming mandatory under the threat of being accused of treason and deprivation of all lands.

An important role in strengthening the Russian army was played by the reforms carried out in the 16th century. Ivan IV. During the military reforms in 1556. The Code of Service was adopted, which legally fixed the procedure for recruiting the noble local army. Each nobleman-landowner and boyar-patrimony exhibited one equestrian armed warrior from 100 quarters (150 acres) of land. For setting up extra people, the nobles received additional rewards, for shortfalls or evasion - punishment, up to the confiscation of the estate. In addition to the estate, they received a monetary salary before the campaign (from 4 to 7 rubles). The military service of the nobility was lifelong and hereditary from the age of 15. All nobles were required to serve. Registration of servicemen by counties was introduced, military reviews were periodically held.

However, it was impossible not to take into account that the local recruiting system destroyed the character of the ancient squad: instead of a permanent army, which was the squad with a military spirit, with an awareness of military duties, with the inducement of military honor, it created a class of peaceful citizens-owners who only by chance, for a while war, were already carrying out a heavy service for them.

The tsar could not keep the noble militia in constant combat readiness, since the army was recruited only in the event of an immediate threat of an enemy attack. It was necessary to create a state-supported army, constantly ready to start hostilities on the orders of the king, subordinate supreme power.

So in 1550 a permanent foot detachment of 3 thousand people was recruited, armed with firearms (squeakers). completed archery army by recruiting free people from the free population. Later, the children and relatives of the archers became a source of replenishment. Their service was lifelong, hereditary and permanent. Unlike the noble militia, which gathered only in case of war, the archers served both in wartime and in peacetime, being on state support, receiving monetary and grain salaries from the treasury. They had a single uniform, the same type of weapons, a single staff organization and training system. The archers lived in special settlements with families, had their own yard and garden plot, could engage in crafts and trade. The formation of the streltsy army laid the foundation for the formation of a standing army of the Russian state .

Under Ivan IV, another new type of troops was developed - city Cossacks. They were recruited, like archers, from free people and made up the garrisons of border cities and fortifications. The name "police" came from the place of recruitment in the cities.

A special group of military people began to be artillerymen - gunners. They were recruited from free craft people. Their service was lifelong, knowledge was inherited from father to son. They were granted various privileges and benefits in addition to salaries and land allotments.

The composition of the Russian army in the time of Ivan IV included field army (people's militia) from rural and urban populations. At various times, one person from 3, 5 and even 30 yards on horseback and on foot, aged 25 to 40 years, was exhibited in the field army. They had to be in good health, shoot well with bows and squeakers, and ski. The forces of the field army carried out military engineering work on the construction of fortifications, roads, bridges, the delivery of guns, ammunition and food.

Compared with the previous period, the recruiting system under Ivan IV has undergone significant changes. So from the former squad was born local - the first standing army The Russian state with elements of a regular device - archers, gunners and city Cossacks, designed to compensate for shortcomings with constant combat readiness noble cavalry collected only in case of war. The people's militia gradually lost its significance, turning into auxiliary troops.

Thus, the creation of a permanent army of the Russian state became an important part of the military reforms of Ivan IV. The significance of the reforms of Ivan the Terrible was highly appreciated by Peter I: “This sovereign is my predecessor and model; I have always imagined him as a model of my government in civil and military affairs, but I have not yet managed to go as far as he did.

Regiments of the "new system"

Early 17th century was one of the most difficult and dramatic periods in the history of Russia. Troubles, the peasant uprising of Ivan Bolotnikov, the Polish-Swedish intervention ruined the country, seriously undermining its military potential. There were not enough funds for the maintenance of the archers, the discipline of the "sovereign troops" fell. Russia was in dire need of recreating a trained army. In 1607, the Charter of military, cannon and other matters relating to military science was developed. This charter was used as a guide to the combat training of Russian troops and their actions in battle.

With the accession of Mikhail Romanov in 1613, the period of unrest and anarchy ended. AT difficult conditions gradually began to revive the armed forces. So in 1630, in the most major cities Russia began to form regiments of the "new order"(unlike the "old" - archery and city Cossacks).

In the second half of the XVII century. the regiments of the "new system" were finally established. Were formed soldier (infantry), reiter (cavalry) and dragoon (cavalry trained on foot) regiments. Unlike the countries of Western Europe (except Sweden), where mercenarism was widespread, in Russia for the first time there was a system of compulsory military service for all social strata of the indigenous population. This was a truly reformist step that predetermined the further course of building the Russian armed forces.

The regiments of the "new system" were completed mainly by forced set dependent people (soldier regiments) and forced entry petty and landless nobles and boyar children (reitar service). The Reiters received a monetary salary for their service, many received estates. Spearmen and hussars had the same rights as the Reiters. It was the noble cavalry of the "new system". In peacetime, they lived on their estates, but were obliged to gather for one month for training. For failure to appear, estates were taken away from the nobles and transferred to soldier regiments. Discipline was strict for everyone, and at that distant time it was considered one of the fundamental principles of military construction.

Soldiers were recruited for permanent life service according to the principle: from three brothers one by one, from four - two each, or from estates and estates - one each from 25-100 households (the sizes of the sets varied). They lived in state-owned houses and special soldier's settlements in cities on full state support. The soldiers kept land allotments for the maintenance of families. Part of this army was permanent, part was recruited for the duration of the war, being at home in peacetime, ready to appear at the first call to their regiments.

Thus, the complex, almost 50-year-old (30s - 70s of the 15th century) process of folding the troops of the "new system" showed their advantage over the troops formed by other methods. The source of recruitment was the forced involvement of ever larger masses of the population in military service, which became mandatory for all segments of the population. In Russia, the prototype of a regular army was taking shape. It was destined to finally bring this idea to life to the great reformer - Peter I.

In the wars of the XV - early XVII centuries. the internal structure of the armed forces of the Moscow state was determined. If necessary, almost the entire combat-ready population rose to defend the country, but the backbone of the Russian army was the so-called "service people", divided into "service people from the fatherland" and "service people according to the instrument." The first category included service princes and Tatar "princes", boyars, roundabouts, residents, nobles and boyar children. The category of "instrument service people" included archers, regimental and city Cossacks, gunners and other military personnel of the "Pushkar rank".

At first, the organization of the Moscow army was carried out in two ways. Firstly, by prohibiting the departure of service people from the Moscow princes to Lithuania and other sovereign princes and by attracting landowners to carry out military service from their estates. Secondly, by expanding the grand duke's "court" through the permanent military detachments of those specific princes whose possessions were included in the Muscovite state. Even then, the issue of material support for the service of the grand ducal soldiers was acute. To solve this problem, the government of Ivan III, which received a large fund of populated lands during the subordination of the Novgorod Veche Republic and the Principality of Tver, began mass distribution of part of them to service people. Thus, the foundations were laid for the organization of the local army, which was the core of the Moscow army, its main striking force throughout the entire period under study.

All other military people (pishchalniks, and later archers, detachments of serving foreigners, regimental Cossacks, gunners) and mobilized to help them land and data people in campaigns and battles were distributed among the regiments of the noble rati, strengthening its combat capabilities. Such a structure of the armed forces was reorganized only in mid-seventeenth century, when the Russian army was replenished with regiments of the "new system" (soldiers, reiters and dragoons), which acted quite autonomously as part of the field armies.

At present, the opinion has been established in the historical literature that, by the nature of their service, all groups of military men belonged to four main categories: cavalry, infantry, artillery, and auxiliary (military engineering) detachments. The first category belonged to the noble militia, serving foreigners, horse archers and city Cossacks, horse data (combined) people, as a rule, from monastic volosts, who marched on horseback. The infantry units consisted of archers, city Cossacks, servicemen of soldier regiments (since the 17th century), subordinate people, and, in case of urgent need, dismounted nobles and their combat lackeys. Artillery crews were mainly gunners and gunners, although, if necessary, other instrument people also got to the guns. Otherwise, it is not clear how 45 Belgorod gunners and gunners could operate from fortress guns, when there were only squeakers in Belgorod142. In the Kola prison in 1608 there were 21 guns, and there were only 5 gunners; middle and second half of the 16th century. the number of guns in this fortress increased to 54, and the number of artillerymen - up to 9 people. Contrary to the popular belief that only people from the field were involved in engineering work, it should be noted that a number of documents confirm the participation of archers, including Moscow ones, in fortification work. So, in 1592, during the construction of Yelets, the village people assigned to the "city affairs" fled and the fortifications were built by the new Yelets archers and Cossacks. Under similar circumstances, in 1637, the Moscow archers "placed" the city of Yablonov, as reported to Moscow by A.V. Buturlin, who was in charge of construction: "And I, your serf,<…>ordered the Moscow archers under the Yablonov forest to set up a prison from the Yablonov forest to the river to Korocha.<…>And the prison was made and completely strengthened, and wells were dug and gouges were placed on April 30th. And I sent the standing sovereign of the guards, your serf, to set up for [the] foot of the Moscow archers before the arrival of military people. Where did you happen to put the spears on the same number. And how, sir, the standing guards of the organizer and completely strengthened, and about that to you, sir, I, your serf, will write off. And oskolenya, sir, do not go to the nadolbny business. And the gouges weren’t brought to the Khalansky forest of two versts ... ". Let's analyze the information given in this voivodeship formal reply. With Buturlin in 1637, under the Yablonov forest, there were 2000 archers and it was their hands that the main front of the work was completed, since they were appointed to help service people Oskolyane evaded burdensome duty.

Streltsy took an active part not only in the protection of work on the abuts that unfolded in the summer of 1638, but also in the construction of new defensive structures on the Line. They dug ditches, poured ramparts, put up gouges and other fortifications on Curl and Shcheglovskaya notch. On the ramparts erected here, Moscow and Tula archers made 3354 wicker shields-rounds.

A number of publications will consider not only the composition and structure of the Moscow army, its weapons, but also the organization of service (marching, city, security and stanitsa) by various categories of service people. And we start with a story about the local army.

***

In the first years of the reign of Ivan III, the core of the Moscow army remained the grand ducal "court", "courts" of specific princes and boyars, consisting of "free servants", "servants under the court" and boyar "servants". With the annexation of new territories to the Muscovite state, the number of squads that went into the service of the Grand Duke and replenished the ranks of his cavalry troops grew. The need to streamline this mass of military people, the establishment of uniform rules for service and material support forced the authorities to begin the reorganization of the armed forces, during which the petty princely and boyar vassalage turned into sovereign service people - landowners who received land dachas for their service in conditional holding.

Thus, the equestrian local army was created - the core and main striking force of the armed forces of the Moscow state. The bulk of the new troops were nobles and boyar children. Only some of them had the good fortune to serve under the Grand Duke as part of the Sovereign's Court, whose soldiers received more generous land and monetary salaries. Most of the boyar children, moving to the Moscow service, remained at their former place of residence or were moved by the government to other cities. Being ranked among the service people of a city, the landlord warriors were called city boyar children, organizing themselves into district corporations of Novgorod, Kostroma, Tver, Yaroslavl, Tula, Ryazan, Sviyazhsk and other boyar children. The main service of the nobility was held in the troops of the hundredth system.

Emerging in the 15th century the difference in the official and financial position of the two main divisions of the most numerous category of service people - the courtyard and city boyar children, was preserved in the 16th and first half of the 17th centuries. Even during the Smolensk War of 1632-1634. yard and city local warriors in discharge records were recorded as completely different service people. So, in the army of princes D.M. Cherkassky and D.M. Pozharsky, who was going to help the voivode M.B. Shein, there were not only “cities”, but also a “courtyard” sent on a campaign, with a list of “stewards and solicitors, and Moscow nobles, and tenants” included in it. Having gathered in Mozhaisk with these military people, the governors were to go to Smolensk. However, in the "Estimate of all service people" of 1650/1651, courtyard and city nobles and boyar children from different counties, pyatins and camps were indicated in one article. In this case, the reference to belonging to the "court" has turned into an honorary name for landowners who serve together with their "city". Only elected nobles and boyar children were singled out, who were really involved in the service in Moscow in order of priority.

In the middle of the XVI century. after the thousandth reform of 1550, noblemen stand out from among the service people of the Sovereign's court as a special category of troops. Prior to this, their official significance was not highly valued, although the nobles were always closely connected with the Moscow princely court, trace their origin from the court servants and even serfs. The nobles, along with the boyar children, received estates from the Grand Duke for temporary possession, and in wartime they went on campaigns with him or his governors, being his closest military servants. In an effort to preserve the cadres of the noble militia, the government limited their departure from service. First of all, the enslavement of servicemen was suppressed: Art. 81 of the Sudebnik of 1550 forbade accepting boyar children as slaves, except for those "whom the sovereign will set aside from service."

***

When organizing the local army, in addition to the grand ducal servants, servants from the Moscow boyar courts dissolved for various reasons (including serfs and yard servants) were taken into service. They were endowed with land that passed to them on the rights of conditional holding. Such settlements became widespread shortly after the annexation of the Novgorod land to the Moscow state and the withdrawal of local landowners from there. They, in turn, received estates in Vladimir, Murom, Nizhny Novgorod, Pereyaslavl, Yuryev-Polsky, Rostov, Kostroma "and in other cities." According to K.V. Bazilevich, out of 1310 people who received estates in the Novgorod pyatinas, at least 280 belonged to the boyar servants. Apparently, the government was satisfied with the results of this action, subsequently repeating it when conquering the counties that previously belonged to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. From the central regions of the country, service people were transferred there, who received estates on lands confiscated from the local nobility, who, as a rule, were deported from their possessions to other districts of the Muscovite state.

In Novgorod in the late 1470s - early 1480s. included in the local distribution of the fund of lands, made up of obezges confiscated from the Sophia house, monasteries and arrested Novgorod boyars. Even more Novgorod land went to the Grand Duke after a new wave of repressions that came in the winter of 1483/1484, when "the prince caught the great [o] big boyars of Novogorodsk and the boyars, and ordered their treasuries and the village to unsubscribe everything to himself, and he gave them estates in Moscow according to city, and other boyars, who roared from him, ordered those to be imprisoned in the city. The evictions of Novgorodians continued later. Their estates without fail unsubscribed to the sovereign. The confiscation measures of the authorities ended with the seizure in 1499 of a significant part of the sovereign and monastic patrimonies, which entered the local distribution. By the middle of the XVI century. In the Novgorod Pyatina, more than 90% of all arable land was in local holding.

S.B. Veselovsky, studying conducted in Novgorod in the early 80s. 15th century distribution of service people, came to the conclusion that already at the first stage, the persons in charge of land acquisition adhered to certain norms and rules. At that time, estate dachas "ranged from 20 to 60 obez", which at a later time amounted to 200-600 quarters (fours) of arable land. Similar norms, apparently, were in force in other counties, where the distribution of land to estates also began. Later, with an increase in the number of service people, local salaries were reduced.

For faithful service, part of the estate could be granted to a serving person as a fiefdom. D.F. Maslovsky believed that the patrimony complained only about the "siege seat". However, the surviving documents allow us to say that any proven difference in service could become the basis for such an award. The most famous case of the mass granting of estates to the estates of distinguished servicemen occurred after the successful end of the siege of Moscow by the Poles in 1618. Apparently, this misled D.F. Maslovsky, however, an interesting document has been preserved - the petition of Prince. A.M. Lvov with a request to welcome him for the "Astrakhan service", transferring part of the local salary to the patrimonial,. An interesting reference was attached to the petition indicating similar cases. As an example, I.V. Izmailov, who in 1624 received 200 quarters of land from 1000 quarters of the estate salary, "from one hundred four to twenty four<…>for the services that he was sent to Arzamas, and in Arzamas the city set up and made all sorts of fortresses. "It was this case that gave rise to the satisfaction of the petition of Prince Lvov and the allocation of 200 quarters of land to his patrimony from 1000 quarters of his local salary. However, he was dissatisfied and, referring to the example of other courtiers (I.F. Troekurov and L. Karpov), who had previously been awarded estates, he asked for an increase in the award.The government agreed with the arguments of Prince Lvov and he received 600 quarters of land in the estate.

Another case of granting to the patrimony of local estates is also indicative. On September 30, 1618, during the siege of Moscow by the army of Prince Vladislav, the serving foreigners "spiritors" Yu. Bessonov and Ya. Bez went over to the Russian side and revealed the enemy's plans. Thanks to this message, the night assault on the Arbat Gates of the White City was repulsed by the Poles. "Spitarschikov" were accepted into the service, given estates, but later, at their request, these salaries were transferred to the patrimony.

***

The formation of the local militia became an important milestone in the development of the armed forces of the Moscow State. Their numbers increased significantly, and the military structure of the state finally received a clear organization.

A.V. Chernov, one of the most authoritative specialists in Russian science on the history of the Russian armed forces, was inclined to exaggerate the shortcomings of the local militia, which, in his opinion, were inherent in the noble army from the moment of its inception. In particular, he noted that the local army, like any militia, gathered only when a military danger arose. The collection of troops, which was carried out by the entire central and local state apparatus, was extremely slow, and the militia had time to prepare for military operations only within a few months. With the elimination of the military danger, the regiments of the nobility dispersed to their homes, stopping service until a new gathering. The militia was not subjected to systematic military training. practiced self-training of each serviceman to go on a campaign, the weapons and equipment of the soldiers of the noble militia were very diverse, not always meeting the requirements of the command. In the above list of shortcomings in the organization of the local cavalry, there is much that is fair. However, the researcher does not project them onto the conditions for building a new (local) military system, under which the government needed to replace the existing combined army as quickly as possible, which was a poorly organized combination of princely squads, boyar detachments and city regiments, with a more effective military force. In this regard, one should agree with the conclusion of N.S. Borisov, who noted that "along with the widespread use of detachments of serving Tatar "princes", the creation of noble cavalry opened the way to hitherto unthinkable military enterprises." The combat capabilities of the local army were fully revealed in the wars of the 16th century. This allowed A.A. Strokov, familiar with the findings of A.V. Chernov, disagree with him on this issue. "The nobles who served in the cavalry," he wrote, "were interested in military service and prepared for it from childhood. The Russian cavalry in the 16th century had good weapons, was distinguished by quick actions and swift attacks on the battlefield."

Speaking about the advantages and disadvantages of the noble militia, it is impossible not to mention that at that time the main opponent of the Moscow state, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, had a similar system of organizing troops. In 1561, the Polish king and Grand Duke of Lithuania, Sigismund II Augustus, was forced, when gathering troops, to demand that "princes, nobles, boyars, gentry in all places and estates may take it upon themselves, whoever is able and capable of serving the Commonwealth should right sya and anyhow each one rode to the warrior in the same barve, the servants of the lighthouse and tall horses. It is significant that the list of weapons of military servants does not contain firearms. The Lithuanian Commonwealth was also forced to convene Stefan Batory, who was skeptical about the fighting qualities of the gentry militia, which, as a rule, gathered in small numbers, but with great delay. The opinion of the most militant of Polish kings wholly and completely shared A.M. Kurbsky, who became acquainted with the structure of the Lithuanian army during his life in exile in the Commonwealth. Let us quote his review full of sarcasm: “If they hear a barbarian presence, they will hide themselves in hard cities; and truly worthy of laughter: armed with armor, they will sit at a table with cups, let the plots with their drunken women go on, and you don’t want to get out of the gates of the city, even more and in front of the very place, but under the hail, slashing from the infidels to the Christians was. However, in the most difficult moments for the country, both in Russia and in the Commonwealth, the noble cavalry performed remarkable feats, which hired troops could not even think of. Thus, the Lithuanian cavalry, despised by Batory, during the period when the king unsuccessfully besieged Pskov, almost destroying his army under its walls, raided deep into Russian territory with a 3,000-strong detachment of H. Radziwill and F. Kmita. The Lithuanians reached the vicinity of Zubtsov and Staritsa, frightening Ivan the Terrible, who was in Staritsa. It was then that the tsar decided to abandon the cities and castles conquered in the Baltic states in order to end the war with the Commonwealth at any cost.

Page 1 - 1 of 3

Home | Previous | 1 | Track. | End | All

© All rights reserved

In the 15th century, a local system of manning troops was formed in Rus'. Ivan III, who proclaimed himself the sovereign of all Rus', began to widely practice the distribution of estates to the nobles. Having received the land, they were obliged, at the request of the sovereign, to appear on horseback, in combat equipment, with a supply of food and put up a certain number of armed people. Thus, the nobleman became the "serving" man of the king.

This method of manning the armed forces most corresponded to the historical conditions of the Russian centralized state in the period of its creation and strengthening. In this way, a large army was created, which was a strong support central government in the fight against recalcitrant big feudal lords and external enemies. The successors of Ivan III, Vasily III and Ivan IV, continued to distribute estates to service people.

The manorial recruitment system was further developed under Ivan IV (the Terrible), who in the 1550s. carried out a number of military reforms.

In 1555, the "Code of Service" was adopted, which actually completed the reorganization of the local service. By this code, the obligation to serve was extended to all owners of land, depending on its size. A land plot of 50 acres of arable land was taken as a unit. From this section, one person was exhibited with a horse and in full equipment, and in the case of a long hike with two horses. In addition to estates, service people were given monetary salaries, usually paid during campaigns. In this way, the local army increased significantly.

In order to eliminate the opposition and streamline the service of the nobles, the laws of 1550 and 1555. lands were confiscated from the large opposition boyars and transferred to the "oprichnina". Half of all the lands went there. In 1565, the oprichnina army was formed from the nobility, which included about 6 thousand people. It was the most reliable part of the noble cavalry. Thus, the progressive role of the oprichnina army consisted in the fact that it was the main means of defeating the internal reaction and, together with the archers, made up the strongest part of the entire army of Ivan IV.

The composition of the non-permanent armed forces included a militia of peasants and townspeople, convened during the war. The collection of the militia from the peasant population was carried out according to a certain calculation - "from the plow." The urban population put up people from a certain number of households in the militia. As a rule, the militia in wartime was a foot army. Militia infantry (pishchalniki), armed with firearms, were recruited exclusively for combat operations. Pishchalniks were also called gunners. They were not part of the militia, were on foot and on horseback, and were recruited from the urban population.

The composition of the Russian troops also included mounted and foot urban Cossacks, recruited at the beginning of the 15th century. from free people to carry out garrison and border service. Under Ivan the Terrible, they began to receive, in addition to salaries, land allotments and turned into service Cossacks.

The most important event of Ivan IV was the creation of a permanent archery army. It was completed by recruiting free people from free peasants and townspeople, who were not taxed and other duties. Later, their children and relatives became a constant source of replenishment of the archers. Their service was lifelong, hereditary and permanent. They served in both peacetime and wartime. The archers were on state support, received from the treasury a monetary and grain salary, lived in special settlements, had their own yard and personal plot, could engage in gardening, crafts and trade.

Introduction

Chapter I. The Armed Forces of the Muscovite State in the First Half of the 17th Century

§ I. Boyar and noble army

§II. Streltsy army

§ III. Cossack army

Chapter II. "Shelves of the new system" Alexei Mikhailovich

§ I. Recruitment in the "Shelves of the new system"

Conclusion

List of used literature

Introduction

In the 17th century, the Muscovite state practically did not lag behind and promptly responded to all the latest innovations in military technologies. The rapid development of military affairs was due to the widespread use of gunpowder and firearms.

The Muscovite state, located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, was influenced by both military schools. Since in the XV - XVI centuries. for him, the main opponents were nomads - at first, the experience of the eastern military tradition was taken. This tradition was subjected to significant processing, and its main idea was the dominance in the structure of the armed forces of light irregular local cavalry, supplemented by detachments of archers and Cossacks, who were partly self-sufficient, partly state-supported.

Early 30s. The 17th century, when the government of Mikhail Fedorovich and Patriarch Filaret began to prepare for a war for the return of Smolensk, became a starting point in the history of the new Russian army. The old structure of the armed forces did not meet the needs of the new government. And at active assistance foreign military specialists in the Moscow state, the formation of soldiers, reiters and other regiments of the “new system” trained and armed according to the latest European model began. From that moment on, the general line of Russian military construction in the remaining time until the end of the century was a steady increase in the share of the regular component and a decrease in the importance of the irregular.

The relevance of this work lies in the fact that at present the history of the Russian Armed Forces, in particular their reform, is of interest in society. Particular attention is drawn to the reform period of the 17th century. The range of problems that the Russian government faced at that time in the military sphere echoes those of today. This is the need for an optimal mobilization system to fight against powerful Western neighbors with limited financial and economic opportunities and human resources, as well as this desire to master the effective aspects of military organization, tactics and weapons.

The work is also relevant in that it does not focus only on questions of the regularity or irregularity of the troops, but shows its combat effectiveness during military battles.

Chronological framework the topics cover the period from the beginning of the 17th century to 1676 - the end of the reign of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich.

An independent study of the armed forces of the Russian state began at the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th century, when a certain stock of factual information accumulated in the general historical literature. The largest work of that time was the work of Viskovatov A.V. "Historical description of clothing and weapons of the Russian troops", issued in 1902. In his work, the author presents a unique, one of a kind, such a large-scale study in the field of the history of military ammunition. Viskovatov A.V. based on a wide range of written and material sources. Among them: royal letters (“nominal” and “boyar sentences”), orders and mandates in memory of archery heads, petitions, replies, as well as notes from Russian and foreign travelers.

The next significant contribution to science was the collective work of a group of generals and officers tsarist army and Navy, published in 1911 and called "History of the Russian Army and Navy". "History" shows the development of Russian military affairs and considers outstanding combat episodes. The authors of the book Grishinsky A.S., Nikolsky V.P., Klado N.L. describe in detail the organization, life, weapons and characterize the combat training of the troops.

In 1938, the monograph of Bogoyavlensky S.K. “Armament of Russian troops in the 16th-17th centuries” was published. . Historian based on a large number of archival data, describes in detail the weapons and equipment of the Russian troops. The achievement of the author is that after the revolution it was the only new work that later became a classic.

With the beginning of the Great Patriotic War release scientific papers is shrinking. In 1948, an article by Denisova M.M. was published. "Local cavalry". In this article, the author convincingly refuted one of the myths of the old historiography about the military-technical backwardness of the Russian army. In addition, Denisova M.M. based on archival data, gives a description of the real appearance and armament of the local cavalry in the 17th century.

Chapter I. The Armed Forces of the Muscovite State in the First Half of the 17th Century

Boyar and noble army

The basis of the armed forces of the Moscow state was the local army, which consisted of nobles and boyar children. During the war, they acted with the Grand Duke or with the governors, and in peacetime they were landowners and received land for conditional holding for service.

The prerequisites for the appearance of the local army appeared in the second half of the XIV century, when feudally organized groups began to replace the junior and senior combatants, headed by a boyar or a serving prince, and the group included boyar children and courtyard servants. In the 15th century, such an organization of detachments replaced the city regiments. As a result, the army consisted of: the grand ducal court, the courts of specific princes and boyars. Gradually, new appanage principalities were included in the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the courts of appanage princes and boyars were disbanded, and service people passed to the Grand Duke. As a result, the vassalage of princes and boyars was transformed into sovereign servants, who received estates for service in a conditional holding (less often - in an estate). Thus, a local army was formed, the bulk of which were nobles and boyar children, as well as their combat serfs.

Boyar children, as a class, formed at the beginning of the 15th century, were initially not very large estate owners. They were "assigned" to this or that city and began to be attracted by the princes for military service.

The nobles were formed from the servants of the princely court and at first played the role of the closest military servants of the Grand Duke. Like the children of the boyars, they received land plots for their service.

In the Time of Troubles, the local army, at first, could resist the troops of the interventionists. However, the situation was aggravated by the peasant uprisings of Khlopk and Bolotnikov. Tsars Boris Godunov and Vasily Shuisky were also not popular. In this regard, the landlords fled from the army to their estates, and some even went over to the side of the interventionists or the rebellious peasants. The local militia, headed by Lyapunov, acted as part of the First People's Militia in 1611, which did not take place. In the same year, nobles and boyar children became part of the Second People's Militia under the leadership of Prince Pozharsky, as its most combat-ready unit. For the purchase of horses and weapons, he was given a salary of 30 to 50 rubles, collected from public donations. The total number of service people in the militia was about 10 thousand, and the number of the entire militia - 20-30 thousand people. The following year, this militia liberated Moscow.

The Time of Troubles led to the crisis of the local system. A significant part of the landlords became empty and could not receive support from the peasants. In this regard, the government took measures to restore the local system - paid salaries, introduced benefits. By the second half of the 1630s, the combat capability of the local troops was restored.

The number of troops in the 17th century can be established thanks to the preserved "Estimates". In 1632 there were 26,185 nobles and boyar children. According to the "Estimate of all service people" of 1650-1651, there were 37,763 nobles and boyar children in the Moscow state, and the estimated number of their people was 40-50 thousand. By this time, the local army was being supplanted by the troops of the new system, a significant part of the local army was transferred to the Reitar system, and by 1663 their number had decreased to 21,850 people, and in 1680 it was 16,097 people of the hundred service (of which 6385 were Moscow ranks) and 11 830 of their people.

In peacetime, the landowners were on their estates, and in case of war they had to gather, which took a lot of time. Sometimes it took more than a month to fully prepare the militia for hostilities.

They went on a hike with their food.