On December 11, 1994, units of the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia entered the territory of Chechnya, fulfilling the decree of President Yeltsin signed two days earlier "On measures to suppress the activities of illegal armed groups on the territory of the Chechen Republic and in the zone of the Ossetian-Ingush conflict." This date is considered the beginning of the First Chechen campaign.

The war that Russia waged with the militants and the government of the self-proclaimed state of Ichkeria claimed tens of thousands of lives. The data varies, and no one can give exact numbers yet. The loss of federal troops killed and missing is just over 5,000 people. The militants, according to various sources, were liquidated and taken prisoner from 17,000 (estimation of the federals) or 3,800 killed (estimation of Chechen sources).

The civilian population suffered the greatest losses, especially if we count not only those who suffered on the territory of Chechnya itself, but also the inhabitants adjacent territories, including victims of attacks on Budyonnovsk, Kizlyar and the village of Pervomayskoye. According to various estimates, 25,000–40,000 people were killed, and this is only for the period from 1994 to 1996.

On the day of the 25th anniversary of the First Chechen campaign, we recall the chronology of events and talk with eyewitnesses about what we remember today about that war.

“Before the storming of Grozny, the military met a few hours before the battle”

Grozny. December 5, 1994 On the eve of the war. Air raids on Grozny have ceased, and rallies continue in front of the presidential palace. Division soldiers special purpose during prayer. Photo Babushkin A./TASS newsreel

The events in Chechnya have a long history. The independence of the republic was proclaimed even before the August coup, on July 8, 1991. In November of the same year, Boris Yeltsin introduced a state of emergency in Chechnya. At the end of the year, the process of withdrawal from the territory of the republic began. Russian troops, which was fully completed by June 1992.

At the same time, there was a looting of military depots left over from the Soviet Union. Some of the weapons were stolen, some were sold, about half of all the weapons the federals were forced to hand over to the Chechen side free of charge.

So in the hands of the militants and the local army, which was created by the President of the Republic Dzhokhar Dudayev, it turned out great amount weapons and military equipment. Robberies, murders, open confrontation between various political and criminal clans began, from which the local population suffered. It was under the pretext of protecting civilians that federal troops entered Chechnya in December 1994.

In less than a month, having taken several settlements, including Khankala, where the enemy's military airport was located, the federals moved to Grozny. The assault began on the night of December 31st. The attempt to take the city failed. Later, General Lev Rokhlin said: “The operation plan developed by Grachev and Kvashnin became in fact a plan for the death of troops. Today I can state with full confidence that it was not substantiated by any operational-tactical calculations. Such a plan has a well-defined name - an adventure. And given that hundreds of people died as a result of its implementation, this is a criminal adventure.”

Grozny. April 24, 1995. Residents of the city in the basement of a destroyed house. Photo by Vladimir Velengurin / ITAR-TASS

“For me, the First Chechen campaign began in January 1995: in Moscow in the hospital. Burdenko, I saw a tanker who was seriously wounded during the storming of Grozny on New Year's Eve. A young boy, a green lieutenant 1994 of the Kazan Tank School, who immediately fell into this terrible meat grinder. By that time, he had undergone several operations, and more interventions were to come.

His tank was shot down at the crossroads of Mayakovsky Street in the center of Grozny. The militants of the Russian military were already waiting: in all the houses the first floors were blocked, on the upper floors the interior partitions were broken to make it easier to move between firing positions. There were snipers and grenade launchers on the roofs. One of them hit the tank when the soldiers opened the top hatch for a while so as not to suffocate. All three miraculously survived, but were seriously injured.

A characteristic moment of how this operation was being prepared. In an interview, the tanker told me that he met those who would be in his crew just a few hours before the offensive. There was no question of any coherence - they were people from different military districts, a real hodgepodge. There was a catastrophic unpreparedness for combat in urban conditions. But once upon a time Soviet army there was a huge experience: this was taught in military universities, books were written about it, all the battles of the Great Patriotic War were dismantled, from Stalingrad to the battle for Berlin. And in 1994 all this was forgotten. How many guys we lost, how many prisoners were exchanged later.

I learned about the terrible consequences of the New Year's assault on Grozny later, having already been in Chechnya and had time to form my opinion about that war. In 1997, I came across a film taken by the fighters of the Moscow OMON for internal use. This is a service video that has never been published anywhere. In the frame - the fighters who in January 1995 entered the city after the assault to find at least someone alive, but saw only the burned skeletons of our equipment, and in the houses - unarmed soldiers shot by militants. I especially remember this scene: a fighter sees a cardboard box, pushes it, it opens, and cut off human heads roll out from there.

Yuri Kitten

Military observer, in 1994 - correspondent of the newspaper "Red Warrior" of the Moscow Military District

"A soldier's mother wanted to hear that her son was alive"

Grozny. Checkpoint. February 1996 Photo by Pavel Smertin

The federal troops managed to gain a foothold in Grozny later, after the Presidential Palace was taken on January 19, 1995. In February, Dzhokhar Dudayev left the capital with troops under his control and retreated to the south of Chechnya.

The beginning of 1995 was spent in battles for settlements Bamut, Gudermes, Shawls, Samashki, Achkhoy-Martan. At the end of April, President Yeltsin announced a temporary truce on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the victory in the Great patriotic war, but it was not strictly enforced.

Already on May 12, federal troops launched a massive offensive. In June 1995, the village of Vedeno was taken, which was considered Dudayev's stronghold, then the settlements of Nozhai-Yurt and Shatoi. However, after the terrorist act in Budyonnovsk on July 14-17, during which Shamil Basayev's gang took several thousand hostages, a ceasefire agreement was signed.

During such a lull, Russian and foreign journalists could come to Chechnya. They not only covered the negotiations of the warring parties, but also could move around the republic more freely than during periods of hostilities, visit remote mountainous regions, interview field commanders, and talk with various representatives of the Chechen side in order to find out their point of view on what was happening. .

“When my colleagues and I came in 1995 to cover the negotiations between the federals and representatives of Ichkeria, there were already quite a few soldier mothers in the republic who were looking for their captured sons. Absolutely frantically, fearing nothing, full of hope and at the same time despair, they walked along the Chechen roads.

Usually the women stayed in groups, but one day I saw this scene: several mothers are standing together, and one is at a distance, as if she had been boycotted. Then they explained to me: this woman had just found out that her son was alive and that he was about to be exchanged. And she was embarrassed to look into the eyes of her friends, because she was so happy, her son would be home soon, and there was no news about their children. You see, these mothers - they searched and hoped to the last.

On that trip, a woman approached me and my colleagues and found out that we were going to the mountains, to the Shatoi district, to see the militants. She gave us a photo of her son, they say, in last time he was seen somewhere there, and asked to ask if anyone knew about his fate. I complied with her request, and they answered me: "We remember this guy, he was shot." She asked again: right? The man hesitated, said, "Looks exactly right. Probably right." But I didn't get a definitive "yes".

Time has passed. This mother found me already in Moscow, called the editorial office: “Remember, I gave you a photo of my son, did you find out something?” And while I was thinking about how best to tell her (maybe I would have told it like it is), she added: "Is he alive?" And I answered: "Yes, I'm alive. But I can't say exactly where." I don't know if I did the right thing or not. But they never told us for sure that he was shot, they didn’t show his grave. And she so wanted to hear that her son was alive.

Maria Eismont

Lawyer, journalist, in 1995 - correspondent of the newspaper "Segodnya"

"What a joy it is to die for Christ"

Grozny. March 29, 1995. On the streets of the ruined city. Photo by Vladimir Velengurin / ITAR-TASS

Meanwhile, Grozny was occupied by units internal troops. They patrolled the city, carried guards at checkpoints. But it was only the appearance of "peaceful" time. There was a humanitarian crisis in the city: most of the houses were destroyed, hospitals and schools were damaged, there was no work, it was difficult to buy the simplest products.

Humanitarian aid was supplied to the republic by employees of the International Red Cross. Food rations were also available at the Church of the Archangel Michael. Archpriest Anatoly Chistousov became its rector since March 15, 1995. The church itself was badly damaged as a result of repeated attacks, services were held in the parish house on the territory of the temple.

Less than a year after the events described, Archpriest Anatoly Chistousov and Archpriest Sergei Zhigulin were captured by militants. The Chechens demanded that Anatoly's father renounce Christian faith, tortured and shot on February 14, 1996.

Priest Anatoly Chistousov. Photo by Sergey Velichkin / TASS newsreel

“We had bread brought to us in the evening. And so Father Anatoly offered to perform a fraternal Eucharistic rite over this bread, transforming it with our prayers into the body of Christ. Having performed this sacred act, we divided the bread equally, and from that moment each kept it as a shrine. The last baby I had the opportunity to actually take communion, probably in the fourth or even fifth month of captivity.

I remember Father Anatoly then said: "You'll see, you will be freed, but I won't." I looked at my fellow prisoner and froze: his face was transformed, it became so bright, his eyes shone inexpressibly. Then he said, "What a blessing it is to die for Christ." Realizing that something supernatural was happening at these moments, I nevertheless tried to “ground” the situation, noting: “Is it time to talk about this now? ..” But I immediately broke off: as Christians of the first centuries and as victims of post-revolutionary Russia, we really had the good fortune to suffer for our faith in Christ…”

Archpriest Sergei Zhigulin

Subsequently, he was released, became a monk with the name Philip and received the rank of archimandrite. The photo was taken immediately after the release.

“He had black hair and a completely gray face”

Grozny. February 1996 Photo by Pavel Smertin

At the very end of 1995, the militants managed to win back Argun and Gudermes. New 1996 began with a series of terrorist attacks. On January 9, 1996, a gang of field commander Salman Raduev attacked the city of Kizlyar in Dagestan, capturing over a hundred people in a local hospital.

Retreating to Chechnya, the detachment got involved in a battle near the village of Pervomaiskoye, taking 37 more people in addition to the 165 hostages they already had. On January 19, the militants managed to leave. As a result of this raid, 78 military personnel, employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and civilians of Dagestan were killed, several hundred people were injured of varying severity.

In early March 1996, militants led by Aslan Maskhadov made an attempt to recapture Grozny from the federals, calling this raid Operation Retribution.

“I ended up in Chechnya in February. Our group of journalists was sheltered by officers of the internal troops in the commandant's office of the Zavodskoy district. I could not walk freely around the city: we traveled in an armored personnel carrier, but it often happened that I could not get out of the car and start filming, my escorts did not allow me. So in fits and starts during the week I filmed "peaceful" life in the ruins, which more resembled the scenery of a film about Stalingrad.

One of my escorts was Sergei Nemasev, deputy commander for educational affairs. He walked all the time - I remember it very well then - in boots polished to a shine. All around is mud, mess, this spring-winter thawed earth, torn apart by tanks, and he has polished boots, despite the fact that no one has been watching their appearance there for a long time, people lived in war, realizing that they could be attacked at any minute. It somehow reassured me, inspired hope.

We became friends. Then I hurriedly left, and a few days later I learned that the militants had attacked Grozny. It was clear that, most likely, my acquaintances from the commandant's office of the Zavodskoy district had died. And in the photos that I took to the editorial office for publication, there were people who are no longer alive.

Three months later, we accidentally met Sergei in Vyatka, in a cafe. I did not immediately recognize him: he had a ... gray face. Completely bled. The hair is black and the face is grey. He survived miraculously. And he told how they were killed there. So I also came out of this cafe a different person.”

Pavel Smertin

Photographer, in 1996 - employee of the newspaper "Vyatsky Krai"

“We don’t need a traitor to the Motherland. Let him stay in Chechnya"

Grozny. The commandant's office of the Zavodskoy district. February 1996 Photo by Pavel Smertin

The first and later the second Chechen campaign revealed a serious problem - human trafficking. Not only captured soldiers fell into the slaves of the field commanders, they kidnapped the military, journalists, foreigners - for the sake of ransom. Young women - for the sake of sexual exploitation. Men - mainly for heavy physical labor. According to various estimates, only for one year 1995 into slavery to Chechen fighters more than a thousand people were involved.

“In the village of Vedeno, I and many other journalists often stayed at the house of one of the local residents. Of course, he fought on the “other” side, but we didn’t hear anything bad about him, there were no atrocities on him, he didn’t mock prisoners, didn’t torture or shoot anyone, like other militants.

A young guy lived with this man's neighbors, later we learned that he was Russian. A simple story: did not want to fight, got scared, ran away from the unit. I got to some terrible field commander who executed everyone, but this guy was miraculously lucky. Then he was handed over to another commander, he converted to Islam and ended up in this family. There he was not in the position of a slave, the guy was treated normally: he talked, calmly walked around the village, ate with the owners at the same table. Although sad, of course.

He told us: his mother drank, his grandmother brought him up - a strict, Soviet hardening, who for some reason took him to the draft board. He deserted for the first time, escaped and returned home, but his grandmother handed him over again, where he was beaten and sent to Chechnya, where he deserted again.

And in Moscow, this guy had an aunt, he remembered her from childhood and thought that the aunt would have accepted him. The family was ready to let him go, we began to plan this operation. Thinking about how to take it out. Photographed in front of a white sheet, then to make him a fake press ID. The legend was this: he lost his passport and he is with us, the same journalist.

It remains to find an aunt. We returned to Moscow, looked for her, found her, handed over his letter. She listened to us very politely, offered tea. And then she said: “It is unacceptable to betray the Motherland. God is his judge, but we don’t want to know him. We don’t need traitors.” And she wrote him a reply letter, saying that we are very glad that you are alive, but you are a deserter. It was your choice, we can't accept it, do what you want. We arrived there, gave the letter. They told him to leave anyway. But he cried and decided to stay. Said, "That's right, my home is here now."

The first Chechen campaign officially ended on 31 August 1996 with the signing of the Khasavyurt peace agreement by General Alexander Lebed and Aslan Maskhadov. In April of the same year, Dzhokhar Dudayev was killed. After negotiations between his successor Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev and President Yeltsin, a ceasefire agreement was signed, after which, leaving the Chechen delegation virtually hostage in Moscow, Yeltsin flew to Chechnya on a military plane, where, speaking to Russian troops, he declared: “The war is over. Victory is yours. You defeated the rebellious Dudaev regime."

Military operations and terrorist attacks in Russian cities continued throughout the summer of 1996, however, after the signing of the agreement in Khasavyurt, the federal authorities began to withdraw their forces from the republic in order to re-introduce them three years later, starting the Second Chechen campaign.

“When I came to Khasavyurt with a group of other journalists to cover the signing of the peace agreement, I had a completely opposite feeling: we did not win, this story will continue. On that trip, I had three important meetings, and each one was like a thread into the future.

Firstly, there I saw Khattab for the first time. Then we still did not know much about what kind of person he was, how bloodthirsty he was, and what forces were behind him. Round as a watermelon and rather good-natured face - ordinary, nothing particularly remarkable. All his major atrocities were ahead.

Secondly, on that trip, I met the Pskov paratroopers who were guarding the railway station in the Khankala region. With their commander Sergei Molodov, we communicated very warmly - it was amazing person and a great conversationalist. Absolutely not a paratrooper appearance, thin, rather strict, but very beloved by his fighters, it was clear how he cared about his subordinates, and how they respected him. Three and a half years later, I saw news about the battle near Ulus-Kert, when a company of Pskov paratroopers held back the onslaught of militants and died. The commander of this company was Sergei Molodov, he was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of Russia.

Finally, the third meeting is an acquaintance with Lyubov Rodionova, the mother of Evgeny Rodionov, who was killed by militants in May 1996 for refusing to remove the cross and convert to Islam. She was a small woman, quiet and modest as a mouse. I have a photo of her: a fragile figure in a headscarf against the background of the ruins of Grozny. She was looking for her son, lying at the feet of the field commanders - Basaev, Gelaev, Khattab. She was sent somewhere, sometimes to certain death - to minefields, swaggered over her grief. But by some miracle she came out alive from everywhere. At the time of our meeting, she had not yet found her son. It was only later that I learned that Zhenya’s remains were given to her in parts: first, the body was exhumed, then the head was returned, which the mother was taking home in an ordinary train, and she was kicked out of the car because of the terrible smell.

1. Yuri Kotenok, “ The rustle of flying armor" - memories of a participant in the battles in Grozny on November 26, 1994, which preceded the entry of troops into Chechnya.

2. Vitaly Noskov, " Chechen stories" - a look at events from the military

3. Polina Zherebtsova, "Ant in a glass jar" - the diary of a 9-year-old girl who lived in Grozny and saw the war through the eyes of a child

4. Madina Elmurzaeva, Diary 1994-1995 - notes of a Chechen nurse who lived and worked in Grozny. Died in the line of duty

5. Photo by Edward Opp, a correspondent for the Kommersant newspaper, an American who came to Russia and saw the war through the eyes of a foreigner

Currently, the development of new combat regulations for the Russian Armed Forces is in full swing. In this regard, I would like to bring up for discussion a rather interesting document that fell into my hands during a business trip to Chechen Republic. This is a letter from a mercenary who fought in Chechnya. He does not address anyone, but the general Russian Army. Of course, some of the thoughts expressed by a former member of illegal armed groups can be called into question. But in general he is right. We do not always take into account the experience of hostilities and continue to suffer losses. It's a pity. Perhaps this letter, while new combat regulations are not yet approved, will help some commanders avoid unnecessary bloodshed. The letter is published almost without editing. Only spelling errors have been corrected.

- Citizen General! I can say that I am a former militant. But above all, I am a former senior SA sergeant who was thrown onto the battlefield in the DRA a few weeks before (as I later learned) the withdrawal of our troops from Afghanistan.

So, with three broken limbs, ribs, a strong concussion, at the age of 27 I became a gray-haired Muslim. I was "sheltered" by a Khazarian who once lived in the USSR and knew a little Russian. He got me out. When I began to understand Pashto a little, I found out that the war in Afghanistan was over, the USSR was gone, and so on.

Soon I became a member of his family, but it did not last long. With the death of Najib, everything changed. At first, my father-in-law did not return from a trip to Pakistan. By that time we had moved from Kandahar to Kunduz. And when I returned with spare parts to my house at night, the neighbor boy told me in confidence that they asked and were looking for me. Two days later, the Taliban took me too. So I became a "volunteer" militant mercenary.

There was a war in Chechnya - the first. People like me, Arab Chechens, were being trained for jihad in Chechnya. Prepared in camps near Mazar-i-Sharif, then sent to Kandahar. There were Ukrainians, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, many Jordanians among us, and so on.

After preparation, the last instruction was given by NATO instructors. They transferred us to Turkey, where there are camps for the transfer, rest and treatment of "Chechens". It was said that highly qualified doctors were also from former Soviet citizens.

Across state border we were sent to railway. They drove us through all of Georgia without stopping. There we were given Russian passports. In Georgia, we were treated like heroes. We went through acclimatization, but then the first war in Chechnya ended.

We continued to prepare. Combat training began in the camp - mountain training. Then they carried weapons to Chechnya - through Azerbaijan, Dagestan, Argun Gorge, Pankisi Gorge and through Ingushetia.

Soon they started talking about a new war. Europe and the USA gave the go-ahead, political support was guaranteed. The Chechens should have started. The Ingush were ready to support them. The final preparations began - the study of the region, access to it, bases, warehouses (many of which we did ourselves), issued uniforms, satellite phones. The Chechen-NATO command wanted to forestall events. They were afraid that before the start of hostilities they would close the borders with Georgia, Azerbaijan, Ingushetia and Dagestan. A blow was expected along the Terek. Section of the plains. Destruction by envelopment along the outer ring and the inner stronghold - with a general seizure, a general search of buildings, farmsteads, etc. But no one did this. Then they expected that, having narrowed the outer ring along the Terek with captured crossings, dividing three directions along the ridges, the Russian Federation would move along the gorges to the already tightly closed border. But that didn't happen either. Apparently, our generals, sorry for the freethinking, neither in the DRA nor in Chechnya have ever learned how to fight in the mountains, especially not in open battle, but with gangs that know the area well, are well armed, and most importantly, are aware. Absolutely everyone conducts surveillance and reconnaissance - women, children, who are ready to die for the praise of a Wahhabi - he is a horseman!!!

Even on the way to Chechnya, I decided that at the slightest opportunity I would return home. I took almost all my savings out of Afghanistan and hoped that 11 thousand dollars would be enough for me.

Back in Georgia, I was appointed assistant field commander. With the beginning of the second war, our group was first thrown near Gudermes, then we entered Shali. Many in the gang were local. Received money for the fight and home. You are looking for, and he sits, waiting for a signal, and bargains for the money received in battle from the rear for food - dry rations, stew, and sometimes ammunition "for self-defense from bandits."

I was in battles, but I did not kill. Mostly endured the wounded and the dead. After one battle, they tried to pursue us, and then they slapped the Arab cashier, and before dawn he left through Harami to Shamilka. Then he sailed to Kazakhstan for 250 bucks, then moved to Bishkek. Called himself a refugee. Having worked a little, I got used to it and left for Alma-Ata. My colleagues lived there, and I hoped to find them. I even met Afghans, they helped me.

This is all good, but the main thing about the tactics of actions of both sides:

1. The bandits are well aware of the tactics of the Soviet army, starting with the Bendera. NATO analysts studied it, summarized it and gave us instructions back at the bases. They know and directly say that "the Russians do not study these issues and do not take them into account," which is a pity, very bad.

2. The bandits know that the RF Army is not prepared for night operations. Neither soldiers nor officers are trained to act at night, and there is no material support. In the first war, entire gangs of 200-300 people passed through the battle formations. They know that in the Russian Army there is no PSNR (ground reconnaissance radar), no night vision devices, no noiseless shooting devices. And if so, the bandits carry out all sorties and prepare at night - the Russians are sleeping. During the day, bandits conduct sorties only well-prepared and for sure, and so - imprisonment, rest, collection of information is carried out, I have already said, by children and women, especially from among the "victims", that is, who have already killed their husband, brother, son and etc.

The most intensive indoctrination of these children is carried out, after which they can even go to self-sacrifice (jihad, ghazavat). And ambushes come out at dawn. At the appointed time or on a signal - from the cache of weapons and forward. They put up "beacons" - they stand on the road or on a high-rise, from where everything is visible. As our troops appeared - left - this is a signal. Almost all field commanders have satellite radio stations. Satellite data received from NATO bases in Turkey is immediately transmitted to the field workers, and they know when which column went where, what is being done in the places of deployment. They indicate the direction of exit from the battle, etc. All movements are controlled. As the instructors said, the Russians do not carry out radio monitoring and direction finding, and Yeltsin "helped" them in this, destroying the KGB.

3. Why the huge losses of our troops on the march? Because you carry living corpses in a car, that is, under an awning. Remove awnings from vehicles in combat areas. Deploy the fighters to face the enemy. Have people sit facing the board with benches in the middle. Weapons at the ready, not like firewood, randomly. The tactics of the bandits is an ambush with an arrangement in two echelons: the 1st echelon opens fire first. In

2nd are snipers. Having killed the airborne, they blocked the exit, and no one will get out from under the awning, but if they try, they finish off the 1st echelon. Under the awning, people, as if in a bag, do not see who is shooting and from where. And they can't shoot themselves. By the time we've turned around, we're ready.

Further: they shoot the first echelon through one: one shoots, the second reloads - continuous fire and the effect of "many bandits" are created, etc. As a rule, this sows fear and panic. As soon as the ammunition, 2-3 magazines, is used up, the 1st echelon withdraws, takes out the dead and wounded, and the 2nd finishes off and covers the retreat. Therefore, it seems that there were many militants, and they did not have time to come to their senses, as there were no bandits, and if there were, then at 70-100 meters, and not a single corpse on the battlefield.

In each echelon, carriers are appointed, who do not so much shoot as follow the battle and immediately pull out the wounded and the dead. Appoint strong men. And if the gang had been pursued after the battle, then there would have been corpses, and the gang would not have left. But sometimes there is no one to pursue. Everything in the body rests under the awning. That's the whole tactic.

4. Capture of hostages and prisoners. There are instructions for this too. It says to watch out for "wet chicken." That's what they call lovers of bazaars. Since the rear does not work - take a negligent, careless slob with a weapon "by the back" - and back to the market, get lost in the crowd. And they were. It was the same in Afghanistan. Here is your experience, father commanders.

5. Mistake of command - and the bandits were afraid of this. It is necessary to immediately conduct a census with the "cleansing" of the population. They came to the village - they copied in each house how many people where, and along the way, through the remains of documents in the administrations and through neighbors, it would be necessary to clarify the actual situation in each yard. Control - they came from the police or the same troops to the village and checked - there were no peasants. Here is a list of the finished gang. New ones have come - who are you, "brothers", and where will you be from? Their inspection and search in the house - where did you hide the gun?!

Any departure and arrival - through registration at the Ministry of Internal Affairs. He went to the gang - atu him! Wait - came - slapped. To do this, it was necessary to assign settlements to each unit and establish control over any movement, especially at night with night vision devices, and systematic shooting of bandits coming out to collect. No one else will come out at night, no one will come from the gang.

At this expense, half of the bandits feed at home, so there are fewer problems with food. The rest is decided by our rear, selling products on the sly. And if there was a zone of responsibility, the army commander, explosives and an employee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs would control the situation by mutual efforts, and the appearance of any new one would be his (look for Khattab, Basayev and others at their wives, they are there in winter).

And again, don't disperse the gangs. It is you who plant them like seedlings in a vegetable garden. Example: in the gang where I was, we were once told to urgently go out and destroy the convoy. But the informants gave inaccurate information (the observer had a walkie-talkie about the exit of the first cars, he reported and left, the rest apparently lingered). So the battalion hit the gang, "scattered" and "won". Yeah! Each subgroup always has the task of retreating to where the common gathering area of the gang is. And if they chased us - almost "0" ammunition - they fired. You need to drag two wounded and a dead one. They would not have gone far - of course, they would have abandoned everyone and then, maybe, they would have left.

And so in Ingushetia, in a former sanatorium, the wounded were treated - and again in service. Here is the result of "scattering" - sowing - after 1 month the gang, rested, is assembled. That is why the living and elusive field commanders remain alive for so long. There would be groups rapid response, with dogs, by helicopter, and urgently to the collision area with the support of the "beaten" - that is, who was fired upon, and in pursuit. There are none.

Own correspondent of "Soldier of Fortune" Erkebek Abdulaev talks about how the Chechen militias fought and were going to fight.

After three days of meticulous checks by Chechens in one of the neighboring republics of Chechnya and at intermediate points, on January 18, I was finally taken to Chechnya by their "Ho Chi Minh trail", bypassing the posts of Russian troops. A few nervous hours later, at night with our headlights out, we drove into Grozny through the Southern Corridor.

My driver Aslanbek peered tensely into the darkness. Visibility was already almost zero, and then there was fog. However, in my opinion, it was only to our advantage.

There were often lonely passers-by on the road. There were also armed people, and a “peacekeeper” dragging cans of water on a sled. A small detachment in white camouflage suits stomped in formation.

“Two deaths cannot happen, but one cannot be avoided,” Aslanbek muttered and resolutely stepped on the gas. We drove onto the dam and hopped over potholes, weaving between sinkholes and the mangled remains of cars, some of which were still smoking.

The dam slipped safely and began to climb uphill. Ahead, the reflections of a major fire began to show through the fog: oil storage facilities, set on fire by Russian artillery a month ago, were burning.

Long winded through the streets. Finally we stopped at the gate. We went into a house where several armed bearded men were sitting. Aslanbek whispered something to them, and we set off again. Finally, in the next house we are accommodated for the night. As a guest, I was given a separate room with a luxurious double bed.

In the morning, instead of roosters, we were awakened by artillery preparation. Installations "Grad" thrashed from a nearby mountain. Rockets howled and rustled low over us and burst somewhere nearby in the city. A few minutes later, the shelling ended, and machine-gun bursts rattled in the city, explosions often swelled. Someone attacked someone. Chechen militants did not pay any attention to this. According to them, it is much worse when planes are bombed. And since there is dense cloud cover and thick fog, aircraft do not fly.

People flocked to our residence. The arrival of the correspondent did not go unnoticed. Our house turned out to be something like a small headquarters.

Two excited fighters ran in. Their detachment raided the positions of the Russians. Two installations "Grad" helped a lot. True, the operation was scheduled for five in the morning, and the rocket launchers were late and began shelling at eight (so that's who woke us up!). 18 tanks were destroyed, 12 armored vehicles were captured, including one T-80 tank. No one counted the killed Russian soldiers, there are many of them. Their losses: five killed and seven wounded.

As if to confirm their words, Russian artillery rumbled. It looked like volleys of a battery of self-propelled guns of the Gvozdika type. They hit from the city on the mountain, from where the Chechen "Grads" had recently worked. Shells fly over our house, and explode with sharp pops.

We go out into the street, but because of the fog, nothing is still visible. Aslanbek is concerned. He says that I should get official accreditation from Dudayev's Minister of Information. Russian spotters operate in the city under the guise of civilians and correspondents. The Chechens shoot them on the spot.

We're going to the city. A few blocks later, a Chechen post stops us. You can’t go further: Russian snipers are operating ahead. The Chechens are greatly annoyed by the silent sniper rifles of the Russians. “We can’t pinpoint where they are hitting from,” the militiaman spits in his hearts.

Have to return. At home, I show them the 12th issue of Soldier of Fortune with an article about a screw cutter. They read carefully. One of them, seeing the photo, exclaims: “I have already seen such weapons in our special forces!”

Apparently, these are trophies captured from Russian "colleagues".

Four fighters in white camouflage suits arrive. They are heavily armed: in addition to machine guns for each, they have one RPG-7 and three disposable RPG-26 grenade launchers. Dudaev special forces. The driver of a badly rumpled UAZ was left on the street. He's fiddling with the engine. The soldiers are fed.

Two militias enter. Their group had just returned from downtown. Lost five killed. They managed to pull out three, two remained on the street. Do not let Russian snipers.

Soldiers drink tea and eat fried meat from a frying pan. They discuss what could be done in such a situation. One of the commandos replies that a smoke screen should have been put up.

- And if there are no smoke bombs?

- You can set fire to car tires and roll a dozen into the street ...

The fighters look at each other and, without finishing their meal, hastily leave.

A tall guy comes with a machine gun, in a knitted helmet-mask. Homemade unloading vest bristles with horns with cartridges. Hello. He asks me stereotypical questions that I'm already tired of answering. Slowly pulls off the mask. The face is gray, haggard, a huge bruise on the left cheekbone. The look is cloudy, expressing nothing. Sluggishly eats meat and drinks tea for a long time.

The militia whisper to me that this guy left the battle three days ago. Since January 31, their detachment had been holding a house in the center of Grozny, which was constantly being hit by tanks and flamethrowers. It seems that this repeatedly shell-shocked fighter still has not yet come to his senses. Having eaten, he, as in a slow motion movie, slowly raises his machine gun and, slouching, leaves ...

A noisy crowd pours in. They undress, put their weapons in the corner. Drink tea. They say that they just drove a T-72 tank and an infantry fighting vehicle down the street for an hour, which drove into their area. The fighters remembered how they removed a heavy-caliber KPVT machine gun from a wrecked armored personnel carrier, attached a home-made tripod and adapted some kind of trigger. We decided to test. They gave a turn. The machine gun overturned and crushed the shooter, holding it together with the trigger. The fighter screamed in pain, and the KPVT rumbled into the sky until the cartridges ran out. A couple of ribs would-be arrow broke and crushed the insides.

Another fighter recalled his duel with the SU-25 attack aircraft. He had the last shell left in the anti-aircraft gun cassette, and he had to urgently insert the next clip so as not to stop firing. And the whole calculation fled, because the attack aircraft, having made an anti-aircraft maneuver, dived directly into the position. For endlessly long seconds they held each other at gunpoint. I had to fire the last shell and the plane suddenly rolled to the side. Apparently, he also ran out of ammunition.

A lively conversation ensued about the fight against aviation. The Chechens complained that MANPADS "Strela" and "Igla" do not shoot at Russian aircraft, since they are equipped with electronic units of "friend or foe" identification systems. Therefore, there were even ideas to buy American Stinger missiles abroad.

One of the militias turned to me: “Do you know what Kozyrev and the American Secretary of State were recently talking about in private? What if the Americans gave the Russians the “friend or foe” code of the Stinger? In this case, millions of dollars for the purchase of missiles will go down the drain!

The bearded commando reassured them: “The world has not converged like a wedge on the Americans. We will buy from the British, the French or the Swedes.”

However, the militias were not entirely satisfied with this: “When else will the missiles arrive there? Find an experienced electronics engineer, turn off the identification systems of the Arrows and Eagles, they thought.

I recalled that the Chechens themselves burned six Tunguska missile and artillery systems from the Mozdok brigade, which stormed Grozny on the night of December 31. And they are more serious than the four-barreled Shilok.

The militias threw up their hands: “Who knew that everything would turn out like this. We didn't expect to last that long. Well, maybe a week or two. We had no illusions about this. We didn’t know how to fight: the majority served urgently in the “construction battalion”, and they kept machine guns only during the taking of the oath. Now we've learned a few things."

The Chechen trained regular divisions of the Russian parts were shattered even in the first battles. They were understaffed with militias who had undergone combat testing, mastered captured equipment under the guidance of captured Russian officers. But mostly non-professionals were involved in the battles in Grozny, who went to fight in schools from all the surrounding villages. Small groups, usually five people each, secretly made their way to the rear of the army, delivered a sudden blow and immediately “made their feet”. Sometimes they run into ambushes. Therefore, the number “five” often appeared in the reports of combat losses of the Chechens ...

The commandos answered that Chechen women who had lost their loved ones were also fighting among the militias. According to mountain customs, if all the men in the family die in battle, women take up arms. And it is impossible to refuse them. There are many blondes, both natural, blue-eyed, and dyed. Hence, apparently, the rumors about the Baltic biathletes.

I was also interested in the use of high-precision "smart" weapons. The Chechens remembered only one attempt to use a cruise missile. She flew at low altitude along the bed of the Sunzha River, avoiding obstacles, but her wing caught a tree branch, hit the shore and fell apart without an explosion. The wreckage was immediately filmed by Chechen and Western videographers, and some parts were taken abroad.

The Russians considered Dudayev's decision to withdraw their main forces from Grozny a victory. In fact, with the arrival of spring and warming, epidemics may begin in the city due to the decomposition of uncleaned corpses.

The Russian generals hoped to drive the Chechens out of the city blocks into open fields, but they miscalculated. Those just flowed into others big cities. Until May, when the forests are covered with foliage and reliably cover them from aircraft, the Chechens cannot fight the enemy in the open.

By autumn, all ground communications of the Russian expeditionary force (regardless of whether it will be the regular army or units of the Ministry of Internal Affairs) may be cut. If by that time the war has not been ended long ago by diplomatic means, its course may turn out to be deplorable for the Russian armed forces.

Erkebek Abdulaev. Soldier of Fortune #4 for 1995

The second Chechen war began.

“In early May, we were transferred to the mountains northwest of Gudermes, to the southern tip of the Baragun Range. From here we keep our sights on the railway bridge over the Sunzha, which is guarded by riot police. Before the riot police are cut out, they have time to cause fire on themselves. Every night they have a “war”. From evening to morning, riot police fire around without a break from all types of weapons. A few days later they are replaced by our 7th company. Night "wars" immediately stop: the infantry creeps along the "secrets" and calmly shoots the spirits.

In our “above” there is absolutely silence, no war. Despite this, observers are posted around the clock, streamers are put up. General prophylaxis. Further north along the ridge was the 1st Battalion. The tankers, as usual, were scattered around all the checkpoints.

Around - not a soul. Beauty and nature. The weather is wonderful: sometimes it's hot, sometimes it's raining, and sometimes it will snow at night. In the morning everything melts, and in the afternoon - again Africa. And far to the south you can see high mountains where the snow never melts. Someday we will get to them ... Thyme grows around, and we constantly brew it with tea. Nearby - Sunzha. If you throw a grenade at it, then the fish will get a full duffel bag"

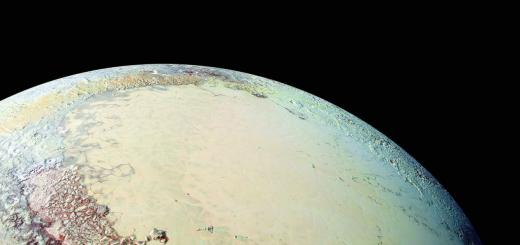

A Chechen prays in Grozny. Photo by Mikhail Evstafiev. (wikipedia.org)

“I saw a blown up car, it was lying on its torn off tower, in the bottom there was a hole about 3 square meters. m almost from side to side. The fighters lay around, they were assisted. The guys were badly broken, one had his eyes gouged out (they had already put on a bandage) and a machine gun was tied to his leg as a tire, he was shaking violently, the place around was a mixture of dirt, oil, blood, cartridges and some kind of garbage ... We just got into the trench how the BMP ammunition detonated. The explosion was so strong that one of the doors crashed into the barrels of the company's tank (they were empty), the turret, together with the top sheet of the hull, was crumpled and thrown a few meters, the sides parted slightly. Yes, and the gunner and I got it - we were sick all day. The hatches were ajar (dangling on the torsion bars), stood on the stopper. Then the MT-LB of mortars with mines caught fire, they pushed it with a BTS from a height, in that place there was a rather steep descent of 200 meters, it rolled to the very bottom, burned out, smoked and went out. Around the middle of the day, the fog began to dissipate, a couple of Mi-24 helicopters flew in, passed over us, and as soon as they were above the positions of the spirits, quite heavy fire was opened on them from small arms and grenade launchers (helicopters were flying at low altitude) "

Memoirs of Hussein Iskhanov (during the war he was Aslan Maskhadov's personal adjutant), journalist Dmitry Pashinsky spoke:

“We didn’t even have enough ammo. Two or three people with bare hands were running near the machine gunner, waiting for him to shoot someone. Fortunately, weapons were soon brought in bulk - if you want to get it in battle, if you want, buy it. AK-74 cost $100-300, the 120th grenade launcher - $700. It was possible to buy at least a tank ($3-5 thousand). The soldiers will spoil it a little, shoot it - like they lost it in battle. They have money in their pockets, we have a tank battalion of three tanks. Over time, the weapon changed to a bottle of vodka or a can of canned food. With this good I could drive through the whole of Chechnya. You drive up to the checkpoint. There are soldiers - grimy, hungry. Winter, and they are in rubber boots.

First Chechen war. (ridus.ru)

Russian troops began to storm Grozny from the outskirts. We tried to hold them back, but they kept coming at us - with infantry, tanks, helicopters, aircraft. They occupied the hills and the city lay at a glance - I don’t want to bomb! Maskhadov ordered to pull all the troops to the center and take up defense near the presidential palace, where the most fierce battles unfolded.

“After daily skirmishes, the militants began to make attempts to break into the railway building. station, and it became more and more difficult to restrain their onslaught, there were practically no cartridges left, the wounded and killed became more and more each time, strength and hopes for help were running out. We held on with all our might, and hoped that reinforcements with ammunition would soon arrive, but we did not wait for the long-awaited help. At that time, I received numerous shrapnel wounds: thighs, both arms, chest, right hand, and a ruptured eardrum in my right ear. I put on my tank helmet, and immediately my head felt calmer, lighter, the shots of machine guns and machine guns, as well as from grenade launchers that hit the crumbling walls of the station, did not reach my brain so clearly through the helmet. It was scary that you would be like a burden, as long as you are on your feet, you can fight.

Memories of a VeteranEvgenia Gornushkina about shelling by militants:

“It was impossible to calmly even go to the toilet. They started shooting at 23-00 to one in the morning. By this time we had not slept and were sitting in the trenches, equipping stores, and when militants appeared, we opened fire. The installations were dug in, covered with chain-link mesh in two rows so that shots from a grenade launcher did not reach the car. They had to fight back with conventional machine guns or mortars and AGS. Then, so that the enemies could not enter our positions, we began to mine the banks of the river, along which they made their way every time, and installed lighting rockets. Also, we were regularly fired upon by snipers, but we successfully answered them.”

S.Sivkov. "The capture of Bamut. From the memories of the Chechen war of 1994-1996”:

“For me, the battle on Bald Mountain was the most difficult of all that I saw in that war. We did not sleep long and got up at four o'clock in the morning, and by five o'clock all the columns were lined up - both ours and neighboring ones. In the center, the 324th regiment was advancing on Lysaya Gora, and to our right, the 133rd and 166th brigades stormed Angelica (I don’t know what names these mountains have on geographical map, but everyone called them that). From the left flank, the special forces of the internal troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs were supposed to attack Lysaya Gora, but in the morning they were not there yet, and we did not know where they were. Helicopters were the first to attack. They flew beautifully: one link quickly replaced another, destroying everything in its path. At the same time, tanks, self-propelled guns, Grad MLRS were connected - in a word, all the firepower was working. Under all this noise, our group drove to the right from Bamut to the checkpoint of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Leaving behind him on the field (about one and a half kilometers wide), we dismounted, lined up and moved forward. BMPs went ahead: they completely shot through a small spruce grove that stood in front of us. Having reached the forest, we regrouped, and then stretched out in one chain. Here we were told that the special forces would cover us from the left flank, and we would go to the right, along the field. The order was simple: "No sound, no squeak, no scream." In the forest, scouts and a sapper were the first to go, and we slowly moved after them and, as usual, looked in all directions (the closing of the column was back, and the middle was right and left). All the stories that the “feds” went to storm Bamut in several echelons, that they sent unfired conscripts ahead, are complete nonsense. We had few people, and everyone walked in the same chain: officers and sergeants, ensigns and soldiers, contractors and conscripts. They smoked together, they died together: when we went out to fight, even appearance it was hard to tell us apart.

It was hard to walk, before the ascent I had to linger for a rest for five minutes, no more. Very soon, intelligence reported that everything seemed to be calm in the middle of the mountain, but there were some fortifications at the top. The battalion commander ordered that they not climb into the fortifications yet, but wait for the rest. We continued to climb the slope, which was literally "plowed" by the fire of our tanks (the fortifications of the Chechens, however, remained intact). The slope, fifteen or twenty meters high, was almost sheer. The sweat poured down in hail, there was a terrible heat, and we had very little water - no one wanted to drag additional cargo uphill. At that moment, someone asked for the time, and I remember the answer well: "Half-past ten." Having overcome the slope, we found ourselves on a kind of balcony, and here we simply fell into the grass from fatigue. Almost at the same time, shooting began near our neighbors on the right.

Second Chechen war. (fototelegraf.ru)

A mortar soon joined the Chechen AGS. According to our battle formations, he managed to release four mines. True, one of them buried itself in the ground and did not explode, but the other hit exactly. In front of my eyes, two soldiers were literally blown to pieces, the blast wave threw me several meters and hit my head against a tree. For about twenty minutes I came to my senses from shell shock (at this time the company commander himself directed the artillery fire.). I remember the next one worse. When the batteries ran down, I had to work at another, large radio station, and I was sent as one of the wounded to the comat. Running out onto the slope, we almost fell under the bullets of a sniper. He didn't see us very well and missed. We hid behind some piece of wood, rested and ran again. The wounded were being sent downstairs. Having reached the pit where the battalion commander was sitting, I reported the situation. He also said that they could not get those Chechens who were crossing the river. He ordered me to take the Bumblebee grenade launcher (a hefty pipe weighing 12 kg), and I only had four machine guns (my own, one wounded and two dead). I didn’t really want to drag a grenade launcher after everything that had happened, and I ventured to say: “Comrade Major, when I went to war, my mother asked me not to run into trouble! It will be hard for me to run on an empty slope. The battalion commander answered simply: “Listen, son, if you don’t take him now, then consider that you have already found the first trouble!” I had to take. The return journey was not easy. Just in the sniper's line of sight, I tripped over a root and fell, pretending to be dead. However, the sniper began to shoot at the legs, tore off the heel with a bullet, and then I decided not to tempt fate anymore: I rushed as best I could - this saved me.

There was still no help, only artillery supported us with constant fire. By the evening (about five or six o'clock - I don't remember exactly) we were completely exhausted. At this time, with shouts: "Hurrah, special forces, go ahead!" the long-awaited "specialists" appeared. But they themselves could not do anything, and it was impossible to help them. After a short exchange of fire, the special forces rolled back down, and we were left alone again. The Chechen-Ingush border passed not far, a few kilometers from Bamut. During the day, she was invisible, and no one even thought about it. And when it got dark and electric lights came on in the houses to the west, the border suddenly became tangible. Peaceful life, close and impossible for us, flowed nearby - where people were not afraid to turn on the light in the dark. Dying is still scary: more than once I remembered my mother and all the gods there. It is impossible to retreat, it is impossible to advance - we could only hang on the slope and wait. Cigarettes were fine, but by that time we had no water left. The dead lay not far from me, and I smelled the smell of decaying bodies, mixed with gunpowder. Someone already did not understand anything from thirst, and everyone could hardly resist the desire to run to the river. In the morning, the battalion commander asked to hold out for another two hours and promised that during this time they should bring water, but if they don’t, he will personally lead us to the river.

Chechens are a mountain people who are not afraid of death, who love their land and are ready to give their lives for it. Nevertheless, the deputy chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, Lavrenty Beria, ordered in March 1942 to stop the mobilization of soldiers from the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. But in August of the same year, this order was canceled because the Nazi troops invaded the Caucasus. In total, 18.5 thousand Chechens and Ingush were mobilized during the entire war, among which almost 70% were volunteers. Of these, only five were awarded the title of Hero. Soviet Union during the war and four more - in the 80-90s.

Khanpasha Nuradilovich Nuradilov alone was able to stop the German offensive near the village of Zakharovka. He captured 7 Nazis and killed 120. He was not awarded for this feat. And only after he was mortally wounded in the last battle, the reward found a hero. By that time, Nuradilov's account included 920 killed and, according to various sources, 12 or 14 captured Nazis. In addition, he captured 7 machine guns.

Senior Sergeant Abuhazhi Idrisov, who destroyed 349 Nazi soldiers, was also presented for the award only after he was wounded in the head. Moreover, this number of Nazis killed is very inaccurate, since only those whom he killed from his sniper rifle were counted. He also had other Wehrmacht soldiers killed by machine guns.

Another heroic son Chechen people, Magomed-Mirzoev Khavadzhi, was one of the first to cross on a raft to the right bank of the Dnieper, thereby ensuring the crossing of the river by soldiers of the 60th Guards Regiment. In his last battle, he, wounded three times, destroyed 144 Nazis with machine-gun fire. An ordinary school director, he understood what military honor was, and did not shame the proud name of a Chechen in the face of the enemy.

Beybulatov Irbaykhan Adelkhanovich commanded a rifle battalion during the liberation of Melitopol. In the most difficult conditions of warfare on the city streets, his unit destroyed more than 1000 German soldiers and 7 tanks. The officer himself killed 18 Nazis and knocked out one tank. His three brothers also participated in the battle with him. He became a Hero of the Soviet Union in 1943 posthumously.

Among the Chechens there were those who were first awarded, then repressed, deprived of all awards, which were then returned again. This happened to junior lieutenant Khansultan Chapaevich Dachiev. Having crossed the Dnieper at the end of September 1943, he obtained valuable information about the deployment German troops, which allowed the division to successfully cross the river two days later. The hero was repressed for a letter to Lavrenty Beria with a request for the rehabilitation of the Chechen people. Dachiev was allegedly convicted of embezzlement for 20 years, but was released at the request of another Hero of the Soviet Union, Movladi Visaitov. In 1985, Dachiev wrote a letter to Mikhail Gorbachev, after which he was returned all the awards and reinstated in the title of Hero of the USSR.

Movladi Visaitov's request could not be ignored for one simple reason - he was too prominent a person - the first Soviet officer, who personally shook hands with General Bolling at the famous meeting on the Elbe, a holder of the Order of the Legionnaires. Prior to that, he miraculously escaped repression in 1944, when he was in the ranks on Red Square, along with another hundred officers - Chechens and Ingush. The order-bearers came with one request - to be listened to and not deported. Already when they were being taken away from the square by the NKVD, they accidentally ran into Marshal Rokossovsky, who ordered the officers to be returned to their unit with their ranks and awards preserved. The dashing cavalryman received a magnificent horse as a gift from the writer Mikhail Sholokhov, which he presented to Bolling. He did not remain in debt and presented Movladi a jeep. In 1990, Visaitov was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, to which he did not live only a few months.

There were other heroes who received high award already during the perestroika and after it:

- Kanti Abdurakhmanov, who with direct fire destroyed a pillbox that stopped the advance of troops west of Vitebsk;

- Magomed Uzuev, who sacrificed his life in the battle for Brest fortress, tied with grenades and rushing into the crowd of Nazi soldiers;

- Umarov Movldi, who fell in battle near the village of Skucharevo. He, twice wounded, led the fighters to attack the enemy, outnumbered.

An interesting fact is that not only officers and soldiers from Chechnya, but also the Muslim clergy contributed to the victory over fascism. Yandarov Abdul-Hamid, the heir of Sheikh Solsa-Khadzhi, ordered his murids (disciples) to tie up the fascist saboteur and deliver him to the NKGB. Baudin Arsanov, the heir of Sheikh Deni Arsanov, helped to arrest the German colonel Osman Gube and participated in the liquidation of the gang of Gatsaraev Abdulkhas. Baudin's son, on the orders of his father, personally shot two fascist paratroopers-saboteurs.