expert opinion

Dmitry LeontievDoctor of Psychology

“It is resilience that determines our ability to withstand stress”

Head of the International Laboratory of Positive Psychology of Personality and Motivation, NRU " graduate School Economics”, professor of Moscow State University named after M.V. M.V. Lomonosov. He is the author of several books, among which is The Psychology of Meaning (Meaning, 2007).

“In modern psychology there is a very important concept - resilience. The term was first coined by Suzanne C. Kobasa, but the main hardiness research is by Salvatore Maddi. It is resilience that determines our ability to withstand stress. It is interesting that Maddy entered the study of resilience in a situation somewhat reminiscent of the current Russian one, in a situation of crisis.

In the 1970s, the University of Chicago, where Muddy was working at the time, was approached by managers from a large telecommunications company. We came up with a specific practical problem. In the United States, tough laws related to the regulation of the telecommunications sector were then adopted. And in order to meet them, all enterprises in the industry inevitably had to carry out large cuts. Until the moment when people would have to be fired, there was still almost a year left - the laws were adopted in advance. But all industry workers found themselves in a situation of severe stress - the sword of Damocles was raised over them. People knew that a quarter of all staff from the beginning of next year would be fired. Who will fall into this number, according to what principle they will choose - no one understood. Therefore, absolutely everyone experienced stress. And managers came for help to psychologists.

After conducting a number of studies, Muddy and colleagues came to the personality traits that are the main defense against stress and its negative consequences. Muddy identified three components of resilience that reinforce each other. And the more they are present in a person, the lower the likelihood that in a situation severe stress he will show negative somatic or psychological symptoms.

The first component is engagement.

Simply put, being in the middle of events is always more advantageous than watching them from the side. It is more beneficial in terms of stress resistance. A person who acts and is determined to act is better protected from stress than one who sits on the sidelines and waits ... You know, I went to opposition rallies from time to time recent years, and when asked why I do it, I always answered: "Scientists have proven that it is good for health." Meaning just the first component of resilience according to Muddy.

The second component is control.

Even in the conditions in which we find ourselves, even realizing that we are not able to control the main thing, the global, you can always find something that you can take into your own hands. Start taking control. Otherwise, by refusing to try to control anything, we give ourselves up to a very unpleasant effect, which is known in psychology as "learned helplessness." This is a complete gap between the actions of a person and what happens to him.

Muddy called the third component of resilience "challenge."

However, I preferred to designate it in the Russian translation as "risk taking". It is a willingness to act without a guarantee of success. Considering that even a negative experience is still useful, it is still an experience. And as you know, even an insurance policy cannot give you a full guarantee. People who are hesitant to act without full guarantees that everything will be fine are much more vulnerable to stress than those who are ready to take action, accepting uncertainty.

All of these traits are enduring personality traits. But this does not mean that people are already born with them, it is quite possible to train them, to influence them. There are appropriate psychodiagnostic methods, there are resilience trainings to identify these traits in yourself and strengthen them. Moreover, it is interesting that Maddy himself, conducting such trainings, received a paradoxical result. Usually, during trainings, measurements are taken: before the training, after it - and then after some time. To understand whether, firstly, the result was obtained, and secondly, whether it was preserved or turned out to be short-lived and everything “slid down” to its original values. Muddy measured participants' resilience levels before training, immediately after training, and six months after training. And I found that the data of delayed testing - after six months - were even higher than the data immediately after the training. That is, the development of resilience launches processes that then begin to work on their own. This is not just the formation of a trait: they imprisoned a person, formed something and released him. No, resilience in this sense - an attitude to the world, a system of attitudes - is some other way of life. If we talk about mental health, and not physical, then this is a healthy lifestyle. Psychologically healthy - and able to protect us in a situation of stress.

CONSISTENCY MODEL:

ACTIVATION OPTION

The cognitive dissonance variant of the consistency model considers consistency or inconsistency between cognitive elements, typically expectations and perceptions of events. On the contrary, the variant of the consistency model, which we will now consider here, describes the consistency or inconsistency between habitual and actual levels of activation or tension. As with all consistency theories, the content is comparatively unimportant. The theory of Fiske and Muddy is practically the only activation concept that has to do with personality. As you will see, it is more comprehensive than cognitive dissonance models.

POSITION OF FISCKE AND MUDDI

Donald W. Fiske was born in Massachusetts in 1916. After studying at Harvard, he received his PhD in psychology from the University of Michigan in 1948. While teaching and researching in a university setting, he has made his main interest the problem of measuring personality variables and understanding the conditions under which human behavior exhibits variability. At Harvard and the Office of Strategic Communications during World War II, he came under the influence of Murray, Allport, and White. Fiske was president of the Midwestern Psychological Association and is now co-chair of the Department of Psychology at the University of Chicago.

Salvatore R. Maddi was born in New York in 1933 and received his PhD in psychology in 1960 from Harvard. When he was at Harvard, he had the good fortune to study with Allport, Beykan, McClelland, Murray, and White. Pursuing professional activity in a university setting, combining teaching and research, Muddy was primarily interested in the need for diversity and personal change. Muddy's collaboration with Fiske began in 1960 and resulted, after a number of years, in the position presented below. Muddy is currently Director of the Undergraduate Psychology Clinical Training Program at the Department of Psychology at the University of Chicago.

Activation theory is a modern trend in psychology, it has had a significant impact on many branches of this scientific discipline. It is quite understandable that the field of personality research, given its complexity, has been influenced by activation theory to the last and very small extent. But Fiske and Maddi (1963; Maddi and Propst, 1963) have proposed a variant of activation theory that not only surpasses most others in completeness and systematicity, but is also quite applicable to personality problems. In the cognitive dissonance variant of coherence theory, the emphasis is on the discrepancy or coincidence between two cognitive elements, usually an expectation or belief on the one hand, and the perception of an event on the other. In the activation theory proposed by Fiske and Muddy, divergence is also the most important determinant of behavior. However, the discrepancy is not considered between two cognitive elements, but between the level of activation to which a person is used to and the level that he is currently experiencing. The discrepancy between habitual and actual levels of activation always generates behavior aimed at reducing the discrepancy. Therefore, the position of Fiske and Muddy is an example of the consistency model in its purest form.

Let's start discussing this theory by immediately formulating the core trend: a person will strive to maintain his usual (characteristic) level of activation. To try to find in your personal experience basis for understanding the meaning of this core tendency, keep in mind that activation is the word for your level of arousal, or vivacity, or energy. Try to remember moments when what happened made you more or less excited than usual, or required more or less liveliness and energy than usual. If it seemed to you that the situation excites you too much or not enough, and you tried to change it somehow, or thought that the requirements for liveliness and energy were too great or insignificant, and tried to somehow fix it, then you found the basis for intuitive understanding of the aspiration of the core, proposed by Fiske and Muddy. It is quite possible that some of you find it difficult to understand the connection of this with your life experience without further, more detailed consideration of this position. I think this is because the concept is fairly new and unfamiliar, and also because the psychological borrowing of the concept of activation is not immediately obvious. Let us therefore hasten to a more detailed study of the position.

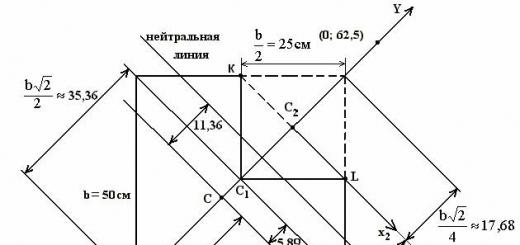

Habitual and actual activation levels

According to Fiske and Muddy (1961, p. 14), activation is a neuropsychological concept that psychologically describes such a common core of meanings as liveliness, attentiveness, tension, and subjective arousal; from the neurological side - the state of excitation of a certain brain center. Obviously, from the psychological side, Fiske and Muddy have in mind a general level of activation of the body, similar to what many other scientists we mentioned called tension. Fiske and Muddy try to make this view more plausible and convincing by examining the neural substratum behind it. On the neurological side, they suggest that the reticular formation - a large subcortical region of the brain - is the center of activation. In this they follow numerous predecessors (for example, Samuels, 1959; Jasper, 1958; O "Leary and Coben, 1958) and try to combine the psychological and physiological levels of theorizing.

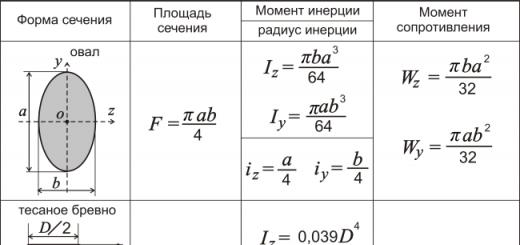

Having drawn up a preliminary definition of activation, Fiske and Muddy turned to the problem of the determinants of this state of excitation. They identified three directions of stimulation and three sources of stimulation, combining all these activation-influencing characteristics in one concept. impact. The three dimensions of stimulation are intensity, significance and diversity. Intensity, defined in terms of physical energy, is an explicit property of stimulation. This describes the kind of difference between loud sound and quiet. Significance needs more explanation. In a sense, everything that can be called a stimulus must have a meaning. If it didn't have a meaning, you wouldn't recognize it. In this sense, significance will be some common feature of stimulation that underlies all others, including intensity and variety. Fiske and Muddy offer a more limited definition of significance. They have in mind mainly the importance of the stimulus to the organism upon which the stimulus has an effect. For example, the word "farewell" for most people has less significance than the words "fire" or "love". Looking at diversity, Fiske and Muddy make a number of points. First of all, diversity describes the state in which the current stimulus is different from the previous one - different in intensity or significance, or both. So, one aspect of diversity is change. Another aspect of variety, novelty, that is, the state in which the current stimulus is unusual, is rare in the life experience of the whole person, whether or not it differs from the stimulus immediately preceding it. The last aspect of diversity is surprise, or a state in which the current stimulus deviates from what the person thought should happen, whether it brings change, or is unusual in a broader sense.

Talking about the dimensions of stimulation that can affect activation prompts us to discuss the sources of stimulation, if only for the sake of completeness. Fiske and Muddy discussed three types of sources: exteroceptive, interoceptive and cortical. Exteroceptive stimulation includes chemical, electrical, mechanical excitation of sensory organs susceptible to events. outside world. In contrast, interoceptive stimulation refers to the excitation of the sense organs that are receptive to events occurring within the body itself. These two sources of stimulation are already well known and need no further explanation. But it is unusual to consider cortical stimulation. Most psychologists who study psychological phenomena in the cerebral cortex tend to view them as a reflection of stimulation coming from other parts of the body or from the outside world. Fiske and Muddy propose to consider the cortex itself as one of the real sources of stimulation. Their point of view seems logically justified, since the brain's locus of activation is located in the subcortical region. Possible anatomical and physiological grounds can be the recent discovery that the cortex not only receives, but also sends nerve fibers towards the reticular formation, which, as you remember, is the very subcortical center. Hebb (1955) suggested that the nerve fibers that run from the cortex to the reticular formation may constitute the physiological substrate for understanding the "immediate driving force possessed by cognitive processes."

For Fiske and Muddy, the level of activation is a direct function of exposure. The impact, in turn, is a certain direct function of the intensity, significance and variety of stimulation coming from interoceptive, exteroceptive and cortical sources. Activation, influence, directions and sources of influence are common to all people and therefore are characteristics of the personality core. So far, Fiske and Muddy's theory may have seemed too complex and divorced from psychologically important phenomena to be of much use to the personologist. But be patient, and the psychological significance of this position will soon become apparent. In terms of complexity, you have to be aware of the possibility that the integrity that Fiske and Muddy were aiming for not only requires this level of complexity, but can also be very helpful in achieving understanding. You may have noticed, for example, that the discrepancy between expectation and reality so emphasized by McClelland and Kelly represents only one aspect of diversity in Fiske and Muddy. Other scholars make surprise the basic determinant of tension and anxiety, terms that differ little in meaning from what Fiske and Muddy have defined as "activation." But when you look at Fiske and Muddy's broad definition of the characteristics of stimuli that produce effects, you begin to wonder if other scientists have oversimplified their views on the determinants of stress.

Having considered the actual level of activation, which is set at any particular point in time by the total effect of stimulation, we can turn to normal level of activation. Fiske and Muddy believe that levels of activation experienced by a person over many days tend to be relatively similar to each other. After all, the patterns and sequences of life must translate into everyday similarities in the intensity, significance, and variety of stimulation from various sources. Over time, the individual should begin to experience a certain level of activation as normal for a certain period of the day. These normal, habitual, activation levels can be approximately measured by calculating the average of a person's actual activation curves over a period of several days. Such a measurement was made by Kleitman (1939), who discovered a pattern he called the cycle of existence. This cycle of existence is characterized by one major ups and downs during the waking period. Upon awakening, highly evolved organisms usually show an increasing degree of vivacity, then a gradual increase over a relatively long period, and later a gradual decline, and finally a sharp decline towards a state of rest and a return to a state of sleep. Some physiological indicators, such as heart rate and body temperature, behave in the same way (Kleitman and Ramsaroop, 1948; Sidis, 1908). Fiske and Muddy believe that the curve described as the cycle of existence is the curve of the habitual level of activation. Since everyone has a habitual level of activation, although different people the curve can take a different shape, it is a characteristic of the core of the personality, and, of course, also the current level of activation that we considered earlier.

Since you are postulating actual and habitual levels of activation, it is almost natural to consider their coincidence or non-coincidence as an important characteristic. This is exactly what Fiske and Muddy do. Their core tendency describes the desire of a person to maintain the level of activation that is familiar for a given time of day. If the actual activation deviates from the usual level, the impact-changing behavior. Two types of deviation are possible. If the current level of activation is higher than usual, there is impact-reducing behavior and if the current level of activation is lower than usual - impact-enhancing behavior. You should note that a behavior that reduces the impact should be an attempt to reduce the intensity, significance or variety of stimulation coming from interoceptive, exteroceptive and cortical sources, and the definition of behavior that increases the impact would be the opposite.

Fiske and Muddy are considered supporters of the theory of concordance, since they consider the desire for a match between actual and habitual levels of activation as the general direction of life. In explaining why people exhibit this core striving, Fiske and Muddy (1961) recognize that the coincidence of actual and habitual levels of activation is experienced as a state of well-being, while discrepancies between them lead to negative emotions, and their severity increases with increasing degree of discrepancy. . And, in order to avoid the uncomfortable experience of negative affect, people try to reduce the discrepancy between the actual and habitual levels of activation, and the success of these attempts is experienced as a positive affect.

The theory of Fiske and Muddy is undoubtedly a model of consistency, since the ideal state is the complete absence of discrepancies between the actual and habitual levels of activation. It does not consider, as in McClelland's theory, that a small degree of divergence is a positive phenomenon. But McClelland argued emphatically that positions like Kelly's were limited because they failed to capture the importance of the boredom of an attendant interest in unexpected events. This point of view is shared by Fiske and Muddy, which is manifested in the fact that, in their opinion, actual activation can not only exceed the usual level, but also fall short of it. When the level of actual activation is too low, the person will actively seek out stimulation with more variety, significance, or intensity. In particular, this means that it will look for unexpected events. This feature of Fiske's and Muddy's position is related to two others important enough to be worth mentioning. First of all, they do not consider stress relief the goal of all life activity, as other proponents of pure conformity models do. Although their point of view is undoubtedly one of the congruence theories, Fiske and Muddy agree with McClelland that sometimes a person may want to reduce tension or activation, and sometimes to increase them. The second feature to be mentioned is that Fiske and Muddy believe that ordinary, everyday life situations carry some variety (change, novelty, surprise) as well as some intensity and significance. In other words, a level of diversity slightly above the minimum is considered normal. This assumption is implicit in the proposition that the habitual level of activation is high enough throughout the day that the actual level of activation can actually lower it. For Fiske and Muddy, the assumption of other consistency theories that the ideal situation is the absence of surprise sounds somewhat ridiculous, since it obviously contradicts ordinary life. Fiske and Muddy agree with McClelland that a human being would be bored in a situation of complete certainty and predictability, and that such a situation would generate too little impact, not enough to raise activation to the usual level.

The theory of Fiske and Muddy is a good example of what is called the homeostatic position. In other words, whenever there is any deviation from the norm, in this case from the usual level of activation, an attempt is made to return to the normal state, which becomes stronger as the degree of deviation increases. There is a general tendency in psychology to view all stress relief theories as homeostatic in nature. Thus, the concepts of Freud, Sullivan, Angyal, Beykan, Rank, Kelly and Festinger, and perhaps some others, could be called homeostatic theories. What strikes me is that in fact these theories represent only half of the homeostatic model, since the norm adopted in them is a state of minimum. This means that the norm can only be exceeded, but it cannot be missed. The theory of Fiske and Muddy, compared to others, is really a homeostatic position in which the norm is something more than a minimum and less than a maximum. Having become acquainted with a theory like Fiske and Muddy, the partial inconsistency of other theories with the concept of homeostasis becomes apparent. Many concepts have been mentioned on the previous pages, and it may be useful to summarize them in terms of core personality terminology at the end of this subsection. The desire of a person to maintain a characteristic or habitual level of activation for him at each moment of time is a tendency of the core of the personality. This tendency is not different in different people, it permeates their whole existence. A number of characteristics of the personality core associated with this core tendency are singled out. These are the actual level of activation, the habitual level of activation, the discrepancy between them, the behavior that increases the impact and the behavior that reduces the impact. For all people, these concepts are in the same relationships. More specifically, there are many sources of individual differences, to name just a few: habitual levels of activation may differ, there may be many ways to increase or decrease exposure, but we will discuss all these issues in chapter 8 on the periphery of the personality.

Formation of a characteristic activation curve

Fiske and Muddy do not believe that a person is born with a habitual activation curve, perhaps it is formed as a result of life experience. More specifically, they do suggest that genetic features, not yet well understood, may predispose a person's habitual activation curve to a certain height and shape. But the accumulated experience of experiencing a certain level of activation at certain moments of the day will, as expected, have a decisive influence on the formation of a characteristic activation curve. So first of all Environment has a significant effect on the individual as a major determinant of the characteristic activation curve. This determination occurs sometime in childhood, although Fiske and Muddy do not say anything definitive about this. In a sense, their vagueness is not very surprising, since we have seen that the consistency model pays little attention to the content of life experience and innate nature. For Kelly and McClelland, behavior is influenced by the very fact that there is a discrepancy between expectation and reality, and not by the content of the discrepancy. For Fiske and Muddy, the impact of early stimulation, not its content, is the formative influence. Because you do not emphasize the importance of stimulus content and innate nature, you have little logical desire to develop a detailed theory of developmental stages in which the content of your desires and the content of the reactions of particularly significant others will be important.

But Fiske and Muddy believe that as experience accumulates, as the days go by one after the other, a characteristic activation curve begins to take on a stable shape. Once established, this curve does not change much under normal circumstances. This is due to the impact on the personality and experience of the desire to maintain activation at a characteristic level. Here it is important to distinguish correction discrepancies between the actual and characteristic levels of activation that actually occur, and anticipatory attempts prevent such discrepancies (Maddi and Propst, 1963). We will now consider anticipatory activity, since it is the basis for understanding why the characteristic activation curve does not change once it has formed, and corrective activity will be considered later. With the accumulation of experience, a person learns certain habitual ways of life, allowing to prevent the appearance of large discrepancies between the actual and characteristic levels of activation. These ways of influencing the present and future intensity, significance, and variety of stimuli from interoceptive, exteroceptive, and cortical sources form a large part of the periphery of the personality. If the periphery of the personality successfully expresses the tendency of the core, then the conditions under which the characteristic activation curve would change do not occur. The spectrum of experience and activities of a person is selected and maintained so that as a result it receives such an impact at different moments of the day, so that the actual levels of activation correspond to the characteristic ones. Perhaps the longer a person lives, the more stable his characteristic activation curve becomes. Only if he had to be exposed to unusual levels of exposure for a long time (an example would be a battlefield) would stimulation conditions be created that could change the characteristic activation curve.

Anticipatory and corrective attempts to maintain consistency

It might seem to you that Fiske and Muddy, like Freud, believe that the personality remains practically unchanged after childhood, but in fact this is not so. Although the habitual activation curve is thought to remain approximately the same under normal circumstances, the behavior and personality processes that express the predictive core tendency function must actually change in order for this curve to remain unchanged. It may seem paradoxical, but in reality everything is very simple and clear. One of the functions of anticipation processes is to protect future activation levels from falling below characteristic levels. But this statement must be understood in conjunction with the fact that any stimulation, regardless of its initial effect, will lose its effect over time. We adapt to stimulation if it lasts long enough. We stop noticing a sound that seemed loud at first if it continues long enough. Over time, something meaningful becomes commonplace. Variety has a particularly short lifespan, since any new or unexpected stimulus reduces its impact so much that it can become boring. A large body of experimental evidence supports the conclusion that the initial effect of stimulation diminishes as the time it is experienced lasts (see Fiske and Maddi, 1961).

This means that the longer a person lives, the more often he must change his anticipatory techniques, preventing future activation levels from falling to too low, uncomfortable levels. With regard to actions, he must constantly expand the range of his activities and interests. As far as thoughts and feelings are concerned, it must become more and more refined and differentiated, for that is how it can be ensured that future stimulation will actually generate a stronger effect than would be felt at the moment. If you look at a Jackson Pollack painting right now, it may have little effect on you, as it appears to be nothing more than a blot of paint, repetitive at best. But by increasing the subtlety of your cognitive and affective processes, you will become much more sensitive to the same picture when you see it in the future. Then, perhaps, it will make a huge impression, since you will be able to perceive the many turns of paint applied layer by layer, and the subtle differences between parts of the canvas. Whether or not we agree on Jackson Pollack's assessment, I think you understand what it means to continually increase cognitive and emotional differentiation as a basis for ensuring that activation doesn't fall too low in the future. Trying to get closer to the point where the universe can be seen in a grain of sand expresses a cognitive, affective refinement of the experience to compensate for its natural tendency to lose impact as it continues or repeats.

But in order to properly maintain the characteristic level of activation, a person must also master anticipatory techniques to protect future exposure from rising above the characteristic level. This is particularly necessary to counterbalance the possible, albeit incidental, side effects of anticipatory attempts to keep activation from falling below characteristic levels. When you try to ensure this by becoming more cognitively, affectively and activityally differentiated, you cannot predict with absolute certainty how it will all end. If you constantly increase your search for new and more meaningful and intense experiences, you increase the likelihood of a crisis coming in which your ability to keep things within acceptable limits is threatened. You may inadvertently be influenced by such powerful impact resulting in an uncomfortably high level of activation. To clarify: if this really happened, a person, according to this theory, would very actively correct a high level of activation. But it would be inefficient for a person to wait until the activation is already very high without taking any action, just as it would be inefficient to rely on the correction of an activation level that has fallen too low.

Progressive cognitive, affective, and activity differentiation is an anticipatory technique for keeping activation high, but how can you keep activation low enough? Muddy and Propet (1963) show that the way to protect yourself from becoming too high in the future is to progressively develop mechanisms and techniques for integrating elements of cognition, emotion, and action, differentiated to ensure that activation does not get too high. low. The essence of integration is the organization of differentiated elements into broad categories of function or importance. Integration processes allow you to see how individual experiences are similar in meaning and intensity to other experiences, no matter how different they may be on the basis of a more specific analysis that serves as a manifestation of processes of differentiation. There is no conflict between the processes of differentiation and integration. No matter how sensitive you have become to our Jackson Pollack canvas through processes of differentiation, you can also fit that canvas into the overall scheme of his work, contemporary work, and art history using processes of integration. The function of integrative processes is to prevent future levels of activation from becoming too high without depriving the individual of the capacity for sensitive experiences necessary to avoid distressing low levels activation.

In fact, as you can see, the proposed image of personality involves constant changes throughout life; these changes serve to maintain minimal discrepancies between actual and habitual levels of activation. Change involves progressive differentiation and integration, or what we used to call "psychological growth." This concept is present in the variants of actualization and perfection of the model of self-realization, although the accents can be placed in different ways. This concept is not characteristic of theories of psychosocial conflict, although it plays a certain role in theories of intrapsychic conflict. Fiske and Muddy are the only representatives of the consistency model to use the notion of psychological growth. In fact, their approach appears to be more fruitful than those of self-actualization or improvement theorists because Fiske and Muddy explain psychological growth in terms of expressing a core tendency, rather than simply seeing it as part of that trend itself.

Now we can return not to anticipatory, but to corrective processes in order to understand their special significance. First of all, it is obvious that the correction of the discrepancy between the actual and characteristic levels of activation is necessary only when the anticipatory processes have failed. In the adult, correction attempts are in the nature of emergency maneuvers (Maddi and Propst, 1963). Speaking plain language, Muddy and Propst suggest that impact-reducing behavior aimed at reducing current level activation, which has already exceeded the characteristic one, distorts reality in the sense that it makes it possible not to notice the impact of stimuli that actually takes place. They believe that exposure-enhancing behavior that aims to raise an actual activation level that is already below the characteristic level also distorts reality, but that this distortion adds something to the stimulation that is actually missing. These sensitizing and desensitizing aspects of corrective behavior come close to one aspect of the traditional understanding of the term "protection". But we must be careful to understand that Muddy and Propet do not mean the active exclusion from consciousness of the urges and desires that form an existing but dangerous part of the personality itself. They simply talk about the existence of a mechanism to exaggerate or underestimate the real impact of stimulation. In this, they come closer to the concept of protection than all other representatives of the consistency model.

Generally speaking, Fiske and Muddy's concept is a consistency theory that focuses on the discrepancy between actual and habitual activation rather than the accuracy of predictions. It is formulated broadly enough to include other correspondence theories that make the same emphasis. In the concept of Fiske and Muddy, behavior and personality are partly focused on reducing tension, and partly on increasing it. In this, this approach resembles McClelland's theory, although it is closer to the traditional correspondence model than to its variant. Fiske and Muddy, like other representatives of the correspondence model, are eclectic in their approach to content, their ideas about man and society contain few inevitable and unchanging characteristics. They believe that the most important features of the core personality remain constant, but the periphery of the personality constantly changes throughout life to satisfy the demands of the core tendency. Constant change occurs in the direction of a simultaneous increase in differentiation and integration or psychological growth.

Views: 2133Category: »

Salvatore R. Maddi is a professor at the School of Social Ecology at the University of California the University of California).

A student of Gordon Allport and Henry Murray, he absorbed their holistic approach to personality, borrowing from them the concept of “personology”, which seems somewhat old-fashioned today. In parallel, he was imbued with an existentialist way of thinking (which Allport predicted a great future) and already in the 1970s he gained fame as the author of the original concepts of needs, the desire for meaning, existential neurosis and existential psychotherapy.

For the last 15 years, the main direction of his work has been the study, diagnosis and facilitation of resilience - the core personality characteristic that underlies the "courage to be" according to P. Tillich and is largely responsible for the success of the individual in coping with adverse life circumstances.

Salvatore Maddi

Personality theories

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS

Translated by I. Avidon, A. Batustin and P. Rumyantseva

S.R.Maddi. Personality theories: a comparative analysis Homewood, Ill: Dorsey Press, 1968

Introductory article (V.M. Allahverdov)

Personality: from mythology to science (D.A.Leontiev)

Foreword

1. Personality and personology

What do personologists do?

What is personality

Three types of personologist knowledge

The core and periphery of personality

Selection of personality theories for inclusion in this book

2. The core of the personality: the conflict model

The Conflict Model: A Psychosocial Approach

Freud's position

Murray's position

Sullivan's position

Rank position

Position of Angyal and Beikan

3. The core of personality: a model of self-realization

Self-realization model: actualization

Rogers' position

Maslow's position

Self-Realization Model: Improvement

Adler's position

White's position

Allport's position

Fromm's position

4. The Core of Personality: Consistency Model

Kelly's position

McClelland's position

Fiske and Muddy's position

5. Theoretical and empirical analysis of ideas about the core of personality: features of three models

The most important features of the three models

Conflict Model

Self-realization model

Consistency Model

Some questions arising from the analysis of the three models

The first question is: is the concept of protection reliable?

The second question is: is all behavior defensive?

Third question: highest form life - is it transcending or adapting?

Fourth question: Is cognitive dissonance always unpleasant and avoidable?

Fifth question: Is all behavior aimed at reducing stress?

Sixth question: Does the personality change radically after the end of childhood?

Instead of a conclusion

6. Periphery of personality: conflict model

The Conflict Model: A Psychoanalytic Approach

Freud's position

Murray's position

Erickson's position

Sullivan's position

Conflict Model: An Intrapsychic Approach

Rank position

Angyal position

Beikan's position

7. Periphery of personality: a model of self-realization

Self-realization model: an update option

Rogers' position

Maslow's position

Self-realization model: an improvement option

Adler's position

White's position

Allport's position

Fromm's position

8. The Periphery of Personality: Consistency Model

Consistency model: a variant of cognitive dissonance

Kelly's position

McClelland's position

Consistency Model: Activation Option

Muddy's position

9. Theoretical analysis of approaches to the periphery of the personality

Different Kinds of Specific Peripheral Characteristics

Motives and Traits

In defense of the concept of motivation

The problem of the unconscious

Peripheral type concept

The problem of individuality

Conflict Model

Self-realization model

Consistency Model

10. Empirical analysis theoretical approaches to the periphery of the personality

Ideal Strategy

Step One: Measuring Specific Peripheral Characteristics

Step two: relationship between indicators

Step Three: Construct Validity of Theoretical Propositions Concerning the Periphery of the Personality

Practical note

Research using factor analysis

Cattell, Guildford and Eysenck

Number of factors

Factor types

Other studies of the periphery of the personality

Freud's position

Murray's position

Erickson's position

Sullivan's position

Rank position

Position of Angyal and Beikan

Rogers' position

Maslow's position

Adler's position

White's position

Allport's position

Fromm's position

Kelly's position

McClelland's position

Muddy's position

Final remarks

11. Formal and content characteristics of a good theory of personality

Formal characteristics

Components of personality theory

General criterion of formal adequacy

Final remarks

Appendix

Freud's theory

Murray's theory

Erickson's theory

Sullivan's theory

Rank's theory

Angyal theory

Beykan's theory

Rogers theory

Maslow's theory

Adler's theory

White's theory

Allport's theory

Fromm's theory

Kelly's theory

McClelland's theory

Fiske and Muddy's theory

Reading Muddi... (A.Yu.Agafonov)

Bibliography

List of additional literature in Russian

Introductory article

Psychology is a strange science. It is worth thinking about her problems, as soon everything becomes unclear. Well, really, does a person know why he thinks about something? Balzac accurately wrote in "Drama on the Seashore": "Thoughts sink into our heart or head without asking us." A person is able to give himself an account only of what he is aware of. But he cannot explain the transition from one of his thoughts to others. We do not know how to realize the creation of thought. Thought is always present in our minds in a ready-made form. Therefore, perhaps, in general, it is more correct to say not "I think", but "I think". But what then is this mysterious "I", which even, it seems, does not even think itself?

Nevertheless, each person thinks something about himself. But how can he be sure of the correctness of his thoughts about himself? Perhaps he should compare his idea of himself with himself. But a man only knows his thoughts, and not he by itself. With what to compare? Maybe you should ask other people and compare your own thoughts with their answers? But this idea does not unravel the puzzle. After all, if I don't know myself well enough, why do other people know me better? If a young man cannot figure out whether he really loves his beloved or only thinks that he loves, then how will those around him help him? Is anyone better than myself able to decide what I think in fact, What do I want, what do I like or not correct? And yet people are able to somehow correct their idea of themselves. They somehow succeed. How?

I hope that this is enough to understand what intricate puzzles theoretical psychologists have to solve. Especially theorists who build the idea of personality. Personality is, after all, such a majestic formation that embraces all the most valuable in us. But it's just not clear what, in fact, she does. Think about it: a person makes some decisions. But on what basis? If these decisions are predetermined by something (genetics, environment, upbringing, situation, past experience, etc.), then the person is not able to act purely at his own discretion. If the decisions of the individual are not predetermined by anything, then how can she make them? It is hardly surprising that there are dozens of personality theories, each of which clarified something very important, but at the same time left some other equally important things without any attention.

You have a wonderful book in front of you. True, she was late for the Russian reader for several decades. A holy place is never empty. During this time, numerous modern reviews of personality theories, proposed by various American psychologists, appeared on bookstores. However, the vast majority of the reviews are made in the style, as our author rightly calls it, "benevolent eclecticism." In them, one chapter talks about one theory, the next about another. And the poor reader can never connect the unconnected in his head. In addition, authors—especially those of American textbooks—often aim at oversimplification and therefore avoid any serious discussion of the issues.

S.Maddy chose a fundamentally different way of presenting the material. He found a more or less successful classification of different approaches (this is already a rare virtue in such books). But most importantly, he constantly compares different approaches and discusses how each theory is experimentally substantiated. That is why his book not only did not become outdated, but, on the contrary, through the prism of decades began to look like a classic. Even a good connoisseur of books on personality theories will find much unexpected and interesting in this work.

S. Maddy's book is intended more for specialists than for the general public. It will be especially useful for psychology students, who, unfortunately, are not always interested in the results of experimental studies, and if they get acquainted with anything from experimentation, they accept the data obtained without any criticism, as the ultimate truth. S. Maddi will teach them to be both attentive and critical. However, this book will also be useful to the largest circle of readers, whom personality problems do not leave indifferent.

Of course, S. Maddy, as befits an American psychologist, even when he overcomes his positivist-behavioristic and deterministic-psychoanalytic environment, avoids discussing the most fundamental problems. And yet the book encourages the reader to think and doubt. And today no one will give a convincing answer to all questions. But this is the true greatness of today's brilliant Science of Psychology, that everyone is given the opportunity to seek new original ideas. However, before starting the search, it is better to know what ideas have been developed by other seekers of truth. These ideas are the focus of this book.

V.M. Allakhverdov, Doctor of Psychology, Professor of the Faculty of Psychology, St. Petersburg State University

Salvatore R. Maddi is a professor at the School of Social Ecology at the University of California.

A student of Gordon Allport and Henry Murray, he absorbed their holistic approach to personality, borrowing from them the concept of “personology”, which seems somewhat old-fashioned today. In parallel, he was imbued with an existentialist way of thinking (which Allport predicted a great future) and already in the 1970s he gained fame as the author of the original concepts of needs, the desire for meaning, existential neurosis and existential psychotherapy.

For the last 15 years, the main direction of his work has been the study, diagnosis and facilitation of resilience - the core personality characteristic that underlies the "courage to be" according to P. Tillich and is largely responsible for the success of the individual in coping with adverse life circumstances.

Books (1)

Personality theories - comparative analysis

Psychology is a strange science. It is worth thinking about her problems, as soon everything becomes unclear.

Well, really, does a person know why he thinks about something? Balzac accurately wrote in "Drama on the Seashore": "Thoughts sink into our heart or head without asking us." A person is able to give himself an account only of what he is aware of. But he cannot explain the transition from one of his thoughts to others.

We do not know how to realize the creation of thought. Thought is always present in our minds in a ready-made form. Therefore, perhaps, in general, it is more correct to say not “I think”, but “I think”. But what then is this mysterious "I", which even, it seems, does not think itself?

St. Petersburg: Rech Publishing House, 2002, 486 p.

.

One of the best works on personality theories.

Content:

Introductory article (V. M. Allahverdov).

Personality: from mythology to science (D. A. Leontiev).

Preface.

1. Personality and personology.

What do personologists do?

What is a personality.

Three types of personologist knowledge.

Core and periphery of personality.

Selection of personality theories for inclusion in this book.

2. The core of personality: a model of conflict.

The conflict model: a psychosocial approach.

Freud's position.

Murray's position.

Sullivan's position.

Rank's position.

Position of Angyal and Beykan.

3. The core of personality: a model of self-realization.

Model of self-realization: actualization.

Rogers position.

Maslow's position.

Model of self-realization: perfection.

Adler's position.

White's position.

Allport's position.

Fromm's position.

4. The core of personality: a model of consistency.

Kelly's position.

McClelland's position.

Position of Fiske and Muddy.

5. Theoretical and empirical analysis of ideas about the core of personality: features of three models.

The most important features of the three models.

conflict model.

self-realization model.

Consistency model.

Some questions arising from the analysis of the three models.

The first question is: is the concept of protection reliable? .

The second question is: is all behavior defensive? .

Third question: is the highest form of life transcending or adapting? .

Fourth question: is it true? the cognitive dissonance always unpleasant and avoided? .

Fifth question: Is all behavior aimed at reducing stress? .

Sixth question: Does the personality change radically after the end of childhood?

instead of a conclusion.

6. Personality periphery: conflict model.

The conflict model: a psychoanalytic approach.

Freud's position.

Murray's position.

Erickson's position.

Sullivan's position.

The conflict model: an intrapsychic approach.

Rank's position.

Angyal's position.

Beykan's position.

7. Personality periphery: model of self-realization.

Model of self-realization: a variant of actualization.

Rogers position.

Maslow's position.

Model of self-realization: a variant of improvement.

Adler's position.

White's position.

Allport's position.

Fromm's position.

8. Periphery of personality: a model of consistency.

Consistency model: A variant of cognitive dissonance.

Kelly's position.

McClelland's position.

Consistency Model: Activation Option.

Maddy's position.

9. Theoretical analysis of approaches to the periphery of the personality.

Various kinds of specific peripheral characteristics.

Motives and traits.

In defense of the concept of motivation.

The problem of the unconscious.

Scheme.

Peripheral type concept.

The problem of individuality.

The content of the periphery of the personality.

conflict model.

self-realization model.

Consistency model.

10. Empirical analysis of theoretical approaches to the periphery of the personality.

The perfect strategy.

Step one: measurement of specific peripheral characteristics.

Step two: the relationship between indicators.

Step three: construct validity of theoretical propositions concerning the periphery of the personality.

Practical note.

Research using factor analysis.

Cattell, Guildford and Eysenck.

Number of factors.

Types of factors.

The content of the factors.

Other studies of the periphery of personality.

Freud's position.

Murray's position.

Erickson's position.

Sullivan's position.

Rank's position.

Position of Angyal and Beykan.

Rogers position.

Maslow's position.

Adler's position.

White's position.

Allport's position.

Fromm's position.

Kelly's position.

McClelland's position.

Maddy's position.

Final remarks.

11. Formal and content characteristics of a good personality theory.

Formal characteristics.

Components of personality theory.

General criterion of formal adequacy.

content characteristics.

Final remarks.

Appendix.

Freud's theory.

Murray's theory.

Erickson's theory.

Sullivan's theory.

Rank's theory.

Angyal theory.

Beykan's theory.

Rogers theory.

Maslow's theory.

Adler's theory.

White's theory.

Allport's theory.

Fromm's theory.

Kelly's theory.

McClelland's theory.

Theory of Fiske and Muddy.

Reading Muddy. (A. Yu. Agafonov).

Bibliography.

List of additional literature in Russian.