An interjection is a special part of speech that expresses, but does not name, various feelings and motives. Interjections are not included in either independent or auxiliary parts of speech.

Examples of interjections: au, ah, oh, well, ah-ah, alas.

Interjections can express various feelings and moods: delight, joy, surprise, fear, etc. Examples: ah, ah, ba, o, oh, eh, alas, hurray, fu, fi, fie, etc. Interjections can express various motives: the desire to drive out, stop talking, encourage speech, action, etc. Examples: out, shh, tsits, well, well, well, hey, scat, etc. Interjections are widely used in conversational style. IN works of art Interjections are commonly found in dialogues. Do not confuse interjections with onomatopoeic words (meow, knock-knock, ha-ha-ha, ding-ding, etc.).

Morphological characteristics

Interjections can be derived or non-derivative. Derivatives were formed from independent parts speeches: Drop it! Sorry! Fathers! Horror! etc. Compare: Fathers! Oh my God! (interjection) - Fathers in service (noun). Non-derivative interjections - a, e, u, ah, eh, well, alas, fu, etc.

Interjections do not change.

Examples of interjections

Oh, my head is burning, all my blood is in excitement (A. Griboyedov).

Ay, guys, sing, just build the harp (M. Lermontov).

Bah! All familiar faces (A. Griboyedov).

Alas, he does not seek happiness and does not run from happiness (M. Lermontov).

Well, master,” the coachman shouted, “trouble: a snowstorm!” (A. Pushkin).

Hey, coachman, look: what’s that black thing there? (A. Pushkin).

Well, well, Savelich! That's enough, let's make peace, it's my fault (A. Pushkin).

And over there: this is a cloud (A. Pushkin).

Syntactic role

Interjections are not parts of sentences. However, sometimes interjections are used in the meaning of other parts of speech - they take a specific lexical meaning and become a member of the proposal:

Oh honey! (A. Pushkin) - the word “ah yes” in the meaning of the definition.

Then there was an “ay!” in the distance (N. Nekrasov) - the word “ay” in the meaning of the subject.

Morphological analysis

For a part of speech interjection morphological analysis not done.

Interjections are peculiar signs indicating certain feelings. What distinguishes them from significant parts of speech is that they express emotions and expressions of will, but do not name them.

“Bah! All the faces are familiar!” - Chatsky exclaims, seeing the whole society in in full force. Interjection “Bah!” expresses the surprise of the hero who, many years later, finds the same people with the same views on life and the same attitude.

Interjections - examples

Most often, interjections are morphologically unchangeable complexes of sounds, which are short cries (or screams) pronounced by a person involuntarily: ah! Ouch! O! eh! etc. It is the nature of these words that allows us to attribute their appearance in people’s speech to the earliest periods in the history of mankind, when our ancestors, having united in a certain group, decided to exchange opinions. Numerous studies by linguists indicate this.

So, Vinogradov V.V. in its fundamental work“Russian Language” claims that interjections, although they do not have the function of naming, have “a semantic content realized by the collective.” This means that each interjection in a given language community has a strictly defined meaning. Each interjection has its own lexical meaning and expresses a certain feeling or expression of will.

For example, the word “Tsyts!” expresses a prohibition, an order to stop something, and “wow!” - astonishment. In addition, the “antiquity” of the origin of interjections is indicated by the fact that they are not included in the system of parts of speech and there are no syntactic connections between them and other words in sentences.

Tatyana ah! And he roars. (Pushkin “Eugene Onegin”).

It is very interesting to trace the appearance of interjections in works of ancient Russian literature: in the “Teachings of Vladimir Monomakh” there is a “Letter to Oleg Svyatoslavich”, which begins with the words: “O I, long-suffering and sad!” But this is the 11th century! In “The Tale of the Murder of Andrei Bogolyubsky,” during the murder itself, Bogolyubsky, addressing his enemies, exclaims: “Oh, woe to you, dishonorable ones!...”. In “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign” (translation by D.S. Likhachev), both the author of the chronicle, Prince Igor, and Yaroslavna use the same interjection “Oh!” in various situations.

And Igor said to his squad:

“Oh my squad and brothers!

It’s better to be killed..."

O Boyan, nightingale of old!

O Russian land! You're already over the hill!..

Oh, moan to the Russian Land,

Remembering the first times

And the first princes!..

Yaroslavna cries early in Putivl on her visor, saying:

“Oh wind, sail!..”

Consequently, we are dealing with quite ancient linguistic units when talking about interjections, as ancient as the first chronicles in which interjections were used. The following examples can be given.

1. By meaning, three main groups of interjections can be distinguished: emotional, imperative, interjections associated with the expression of etiquette norms in speech. Let's consider them in accordance with this classification.

Emotional interjections express the speaker’s emotional reaction to what is happening or to the speech of his interlocutors, his attitude to perceived impressions and their assessment. In the story “Men” by Chekhov A.P.: “My fathers!” - Olga was amazed when they both entered the hut.” This group of interjections is the most numerous; it is accessible even to the smallest (in height and age) native speakers. A child who has barely learned to pronounce sounds will say, “Ew!” if there is an unpleasant smell; when he feels pain, he will say: “Oh!” The hero of the famous comedy “The Diamond Arm” on a narrow street in the Turkish capital had to fall and say the password: “Damn it.” This is also an emotional interjection. How often do we use the following phrase: “Ugh, I wish I could jinx it!”, where the word “ugh” is an emotional interjection. This group of interjections represents the most primitive linguistic construction.

Imperative interjections express an expression of will, a call or encouragement to action. As a rule, this is an appeal to the interlocutor with a proposal to perform this or that action, used in the imperative mood:

Here, take this (hands him a cap and cane) - Khlestakov in N.V. Gogol’s comedy “The Inspector General.”

Tsits! - Grandfather Grishak knocked. (Sholokhov M.A. “Quiet Don”).

Only the call denotes the imperative interjection “Hey!” And the interjection “well” in combination with the accusative case of the pronoun you expresses disdain and the desire to get rid of something: “Come on!” This type of impulse is used in relation to animals: kitty-kiss, chick-chick, atu, which indicates the primitiveness and some kind of primitiveness of interjections.

The third group of interjections associated with the expression of etiquette norms in speech includes remarks containing generally accepted greetings, formulas of gratitude, apologies: thank you, hello, goodbye, sorry, etc.

"She ran to the gate

- Goodbye! - she shouted. (Chekhov “House with a Mezzanine”).

2. The last group of interjections is of particular interest in connection with compliance and non-compliance with norms speech etiquette. In everyday life, in the school environment, in virtual communication and when using mobile communications, the norms of speech etiquette are changing imperceptibly but surely.

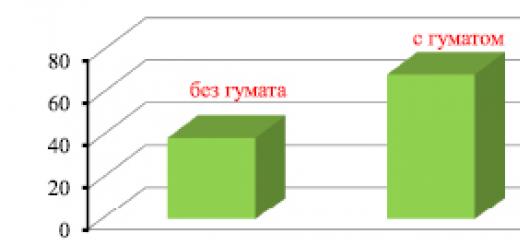

In order to prove this, I conducted a survey among my peers - ninth graders, in which 32 people participated.

To the first question of the questionnaire, “Do you often use interjections in your speech such as “oh”, “hey”, “Lord”, “fu”, “damn it” and others?” The absolute number of respondents answered: “Often” (18 people – 56%);

The use of emotional interjections in the speech of my peers is associated with various school situations. So, I invited the guys to play up the situation of getting a good grade - such a pleasant event! How do ninth graders react to it?

In first place in terms of frequency of use is the interjection “hurray!”, used by 11 people (34%);

In second place is the English “yes!”, this barbarism is very popular in expressing Russian emotions (4 people - 12%).

In third place is our native “wow!” (3 students - 9%).

But below the “prize pedestal” are the words “nice”, “wow!”, about which Mikhail Zadornov makes satirical remarks. Quite often you can hear these words from the lips of students. I asked the teacher in English, what they stand for turns out to be a statement with special agreement.

The words “cool”, “cool”, “super”, which are heard, including on TV screens, are also included in the vocabulary of my peers. But this is already a bias towards slang; I have a negative attitude towards such words.

But the answers to the next question smack of our local flavor; the typical Transbaikal word “but” sounds like a positive answer to any question.

Have you prepared your homework?

- But…

-Have you cleaned the room?

- But…

12 people answer this way, although they know that they should say “yes” in this case; both “yes” and “but” - 3 people; only “yes” - 16 people.

Imperative interjection “Hello!” (meaning “speak, I’m listening to you”) is used in oral speech often, but many people don’t know how to write it: at my request, the guys had to write “hello”: 9 people made mistakes (that’s 28%). Therefore, you must be able not only to pronounce interjections, but also to write them correctly.

Of particular interest to me was the use by my peers of interjections associated with the use of etiquette norms in speech. These words, together with gestures, are like windows through which we can not only hear each other, but also see each other. It’s easy to see how difficult it is to vigorously stamp your foot on the floor and say a friendly “hello” or, waving your hand hopelessly, to say an enthusiastic “ah!”

Thus, gesture as a means of communication is of interest to the researcher. We can often determine a person’s mood by the intonation of a greeting.

So, coming to school in a good mood, our ninth-graders say “hello” - in 29 cases (out of 32), “where necessary, I always say” - 1 person, “rarely” - 2 people. In the same question, other interjections of this group were also mentioned: “thank you”, “goodbye”. As follows from our survey, the norms of speech etiquette are fully used by my peers.

And one more, in my opinion, interesting fact– along with observing etiquette standards, the guys use the interjection “hey!” — 4 people without explanation of the situation; 7 people do not speak or speak rarely; but the majority (21 people! 66%) readily describe situations when they use this interjection. “The interjection hey!, which we hear from a person who knows you, but does not want to call you by name, already sounds like an insult,” wrote theater theorist N.V. Kasatkin. This is exactly how this interjection is used when addressing their friends, relatives, acquaintances who did not catch their name, 14 people. (Therefore, after processing the questionnaires, I had to explain to the guys that they were doing the wrong thing). When addressing a stranger their age, 7 guys say “hey”.

Thus, when conducting such a survey, I was able to verify that it is impossible to imagine live speech without intonation. The role of intonation is especially enhanced in interjections, which are devoid of lexical meaning.

F. Delsarte argued that in terms of richness of intonation, interjection ranks first among all parts of speech. It is precisely the underestimation of the role of intonation that explains the fact that for a long time interjections were confused by some linguists with reflexive cries (reaction to pain, fear, surprise, etc.).

3. And the real treasury of interjections, in addition to living (everyday) speech, is, of course, literature. Works of fiction are replete with interjections, which are a fact of direct live communication and are therefore short and concentrated. They give the characters’ speech emotionality, naturalness and national flavor.

Even the great Cicero said: “Every movement of the soul has its natural expression in the voice...” The space of interjections in the works of Gogol N.V., Tolstoy L.N., Chekhov A.P., Ostrovsky A.I., Gorky A. is infinitely rich. M. - you can’t count them all.

I decided to analyze the use of interjections in a comedy that I recently studied and which I really liked - “The Minor” by D.I. Fonvizin.

The ambiguous interjection “ah” adorns almost every page of the comedy. Having learned that Mitrofan “languished” until the morning, Prostakova, blinded by maternal love, exclaims: “Ah, Mother of God!” And during the lesson, when Mitrofan insults Tsyfirkin, Prostakova remarks: “Oh, Lord, my God!” In the mouth of this “despicable fury”, a man without a soul and heart, these interjections sound blasphemous.

Having learned that the serf girl is sick and is lying down, the same Prostakova conveys her indignation with the same interjection: “Lying down! Oh, she’s a beast!” Having rushed at Mitrofan as a rival in the acquisition of Sophia’s capital, his uncle Skotinin growls: “Oh, you damn pig!” The interjection “ah,” as old as the world, in this context, conveying all of Skotinin’s indignation, gives his phrase a completely bestial connotation.

Interjection “Oh! Ouch! Ouch!" and “ah! ah! ah!” flashes in the speech of the foreigner Vralman, who is not strong in the Russian language.

The outdated interjection “ba” is pronounced by Skotinin quite often: “Bah! What does this one equal?”, “Bah! Bah! Bah! Don’t I have enough light rooms?” In the mouth of the arrogant and arrogant Skotinin, this word sounds denoting bewilderment, with a tinge of sarcasm on the part of the author.

Mitrofan, as befits a darling to whom everything is allowed, often uses imperative interjections that contain the command: “Well! And then what?" - Mitrofan answers his mother, who asks him to learn “at least for show.” In the speech of Sophia, Starodum, Pravdin, Milon, the interjection “a” is often found in different meanings: "A! you are already here, my dear friend!” - says Starodum, seeing Sophia who is waiting for him. And the interjection expresses the joy of meeting. Having received a letter from Count Chestan, Starodum again pronounces the interjection “a” in the sense of “it’s interesting what he writes.” In a dialogue with Pravdin, he says: “Oh, how great a soul should be in the state...”, conveying with this interjection wisdom in understanding the role of the tsar to improve the lives of his subjects.

We managed to count 102 interjections in a comedy so small in volume. In general, in the Russian language, interjections constitute a large and very rich layer of words in terms of the range of sensations, experiences, volitional impulses, and moods they express.

According to the “Reverse Dictionary of the Russian Language”, in the modern Russian language there are 341 interjections - more than prepositions (141), conjunctions (110), particles (149). This intonation wealth must be used skillfully, because the interjection can not only be heard, but also... seen.

So, in the painting by Petrov V.G. “Hunters at a Rest”, an attentive person can hear the intonations of the drawn people, even guess the interjections they use, expressing the surprise of the young hunter; distrust, skepticism, irony of the mean; enthusiastic, boastful exclamations of a hunter - an old man.

In the same way they show us certain life situations paintings by Repin, Kramskoy, Surikov and other masters of the brush.

An amazing part of speech is the interjection, if you can even draw it. And even in the artificial language of the future Esperanto there are interjections - they are not superfluous in the lexicon well-mannered person: bonan tagon! (good afternoon!), bonan vesperon (good evening!), bonvenon! (welcome!), bonvolu (please!) All people at all times in everyday life, on the stage, at school and in the army, in a large audience and in private will use interjections. After all, they are part of our life. And it is impossible to exist without interjections.

Petrukhina Oksana Vladimirovna,

Priezhikh Tatyana Pavlovna

Literature:

1. Vartanyan E.A. "Journey into the Word", M., 1980.

2. Gvozdev A.N. "Modern Russian literary language", M., "Enlightenment", 1973.

3. Collection of “Tales” Ancient Rus'", M., " Fiction", 1986.

4. Sereda E.V. Article “Ah, intonation!”, Journal “Russian Literature” 6, 2006.

5. “Modern Russian literary language” edited by Lekant P.A., M., “ graduate School", 1982.

6. Shansky N.M., Tikhonov A.N. “Modern Russian language”, part 2, M., “Enlightenment”, 1987.

Interjection- a special part of speech that expresses, but does not name, various feelings, moods and motivations. Interjections are neither independent nor service units speech. Interjections are a feature of conversational style; in works of art they are used in dialogues.

Groups of interjections by meaning

There are interjections non-derivative (well, ah, ugh, eh etc.) and derivatives, derived from independent parts of speech ( Give it up! Fathers! Horror! Guard! and etc.).

Interjections do not change and are not members of the sentence . But sometimes an interjection is used as an independent part of speech. In this case, the interjection takes on a specific lexical meaning and becomes a member of the sentence. There was an “au” sound in the distance (N. Nekrasov) - “ay” is equal in meaning to the noun “cry” and is the subject. Tatyana ah! and he roars . (A. Pushkin) - the interjection “ah” is used in the meaning of the verb “gasp” and is a predicate.

We need to differentiate!

It should be distinguished from interjections onomatopoeic words. They convey various sounds of living and inanimate nature: humans ( hee hee, ha ha ), animals ( meow-meow, crow ), items ( tick-tock, ding-ding, clap, boom-boom ). Unlike interjections, onomatopoeic words do not express emotions, feelings, or motives. Onomatopoeic words usually consist of one syllable (bul, woof, drip) or repeated syllables (gul-bul, woof-woof, drip-drip - written with a hyphen).

From onomatopoeic words, words of other parts of speech are formed: meow, meow, gurgle, gurgle, giggle, giggle, etc. In a sentence, onomatopoeic words, like interjections, can be used in the meaning of independent parts of speech and be members of a sentence. The whole capital shook, and the girl hee-hee-hee yes ha-ha-ha (A. Pushkin) - “hee-hee-hee” and “ha-ha-ha” are equal in meaning to the verbs “laughed, laughed” and are predicates.