I.E. Repin. "Sadko" (1876), fragment

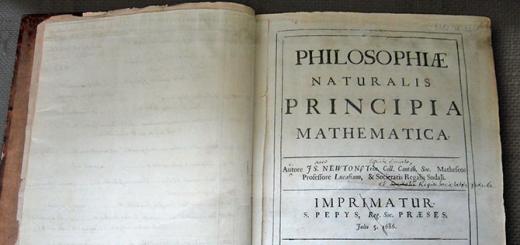

Two equally popular heroes of the Novgorod epic differ, in particular, in that they are connected in different ways with chronicle news about them. The degree of this correlation and the degree of reliability of one of such news were the subject of discussion not only among epic scholars, but also among historians. If about Vasily Buslaev there is, in essence, only one chronicle evidence, although repeated in several monuments, then there is quite a lot of information related directly or indirectly to the prototype of the epic Sadko. Chronicles reported that in 1167 Sotko Sytinich laid the stone church of Boris and Gleb in Novgorod Detinets, which existed until the end of the 17th century. Epics tell that Sadko built one or more churches in Novgorod. CM. Solovyov, who resolutely affirmed the historicity of Vasily Buslaev, spoke cautiously on the question of the historicity of Sadko; “The similarity of the song Sadok with the chronicle,” he writes, “is that in the song the rich guest is a hunter to build churches.” F.I. wrote about this even less definitely. Buslaev. Mentioning that the epic Sadko built churches, the researcher notes: “... this detail is consistent with the news of the Novgorod chronicles that nowhere in Russia were so many churches built by ordinary citizens as in Novgorod,” but does not mention the chronicle Sotko Sytinich.

A.N. Veselovsky had no doubt that the epic reflected, by the similarity of names, the real Sotko Sytinich, the builder of the church of Boris and Gleb. Of the churches built by Sadko, according to the epics, according to the researcher, “the primary is<...>church in honor of Nikola, who saved Sadka from the sea. According to A.N. Veselovsky, the real Sotko Sytinich, rescued during a storm by Boris and Gleb, built a church in their honor, which is noted in the annals. Folk tradition replaced Boris and Gleb with the more popular Nikola. V.F. Miller, who deduced the epic about Sadko mainly from the Finnish epic, on the question of his attitude to the chronicle Sotko Sytinich, in fact, adhered to the same view as Veselovsky. Identified Sotko Sytinich with the epic Sadko and A.V. Markov.

Subsequently, A.N. Robinson dated the epic about Sadko to the 11th century. - based on the fact that the Church of Boris and Gleb was founded by Sotko Sytinich in 1167. The same point of view was expressed by D.S. Likhachev. Talking about the church built by Sotko Sytinich, he writes: “It is natural that the name of its builder passed into the epic and around the construction of the church of Boris and Gleb<...>legends were created. This is exactly what later epics tell:

Shel Sadko, God's kram built

And in the name of Sophia the Wise,

and other versions of epics about Sadko attribute to him the construction of two more churches: Stepan the Archdeacon and Nikola Mozhaisky. Chronicles and Sadko epics are one and the same person. Thus, the emergence of legends about him is also dated. Without touching the essence of the question for the time being, let us eliminate the factual inaccuracies obscuring it. In the text of the epic cited by D. S. Likhachev, Sadko built a temple “in the name of Sophia the Wise”, the chronicle reports on the church of Boris and Gleb (which is not in any epic record), therefore, it is illogical to say that this version of the epic “tells exactly about it". It is not true that the text of the Sophia Time Book says "Satko is rich" - it simply says "Sotko".

2

Let's turn to chronicles. The construction of the Church of Boris and Gleb by Sotko Sytinich is reported in one context or another by 25 annalistic monuments. These are the Novgorod 1st chronicle of both versions, the Novgorod 2nd, Novgorod 3rd of both editions, the Novgorod 4th and Novgorod 5th chronicles, the Novgorod Karamzinskaya, the Novgorod chronicle according to the Dubrovsky list, the Novgorod Bolshakovskaya, the Novgorod Uvarovskaya, the Novgorod Zabeli some , Novgorod Pogodinskaya chronicle of all three editions, Chronicler of the Novgorod rulers, Novgorod chronicler according to the list of N.K. Nikolsky, Novgorod chronicler, discovered by A.N. Nasonov, Pskovskaya 1st Chronicle, Sofia 1st Chronicle of Abraham, Volgodek-Permskaya, Tverskaya, Typographical, Moscow chronicle end of the 15th century, Rogozhsky chronicler, Vladimir chronicler, Resurrection and Nikon chronicles.

14 chronicles contain the news of the very laying of the church by Sotko Sytinich in 1167. We quote it from the oldest of them - the Novgorod 1st chronicle of the senior version: under Archbishop Elijah. In other cases, the text either coincides with the one given, or is reduced or somewhat extended by introducing topographical clarifications (“in Kamenny Grad”, “in Okolotka”, “above the Volkhov at the end of Piskupli Street”). These clarifications are consistent with each other and correspond to the location of the church on the ancient plans of Novgorod. In the future, the church is repeatedly mentioned in chronicles and acts. In particular, it is reported that it was consecrated in 1173, that it was restored after a fire in 1441, and that it was dismantled due to dilapidation in 1682. One of these references (under 1350) says that the church was “built by Sotko Sytinich” .

Chronicle 21 mentions the church of Boris and Gleb, along with the name of its builder, in another connection. Reporting the death by fire in 1049 of the wooden church of St. Sophia (after which the stone St. Sophia Cathedral was built), these chronicles indicate that the wooden Sophia stood on the spot where Sotko Sytinich later built the Church of Boris and Gleb: “On March 4, on Saturday, St. Sophia was burned; beashe was honestly arranged and decorated, 13 the tops of the property, and that St. Sophia stood at the end of Peskuple Street, where now Sotka has erected the church of the stone of St. ; in other chronicles there are abbreviations and additions that are not essential for us now, similar to those that are present in the above news of 1167). These data undoubtedly testify that the builder of the Church of Boris and Gleb, erected in Novgorod in 1167, Sotko Sytinich, is a very real historical person.

In all chronicles, his name is read almost the same: Sotko (in the vast majority of cases), Sytko, Sodko, Sadko, Sotka, Sotka, Sotka; in one case it was obviously corrupted: Sitkomo (Tver Chronicle). The middle name also varies slightly: Sytinich (in most cases), Sytinich, Sytinits, Sytenich, Sygnich, Sytnichi, Stanich, Sotich; in one case spoiled: Sochnik (Novgorod 2nd Chronicle). In epics, the forms of the name are essentially the same: Sadko, Sadke, Sotko, Sadka, Sadok. The epics did not preserve the patronymic of their hero, but they remembered the construction of the temple by him firmly. The very name of the builder and the name of his father are not unique: in similar forms and in various modifications, sometimes in the form of a patronymic or nickname, they are relatively often found in chronicles and ancient Russian acts, for example, the Novgorod ambassador Semyon Sudokov (under 1353), chief guard detachment Grigory Sudok (under 1380), Prince Sytko (under 1400), governor Sudok (under 1445), patrimony Ivan Fedorovich Sudok Monastyrev (under 1464 and 1473), Sudok Ivanov son Esipov (under 1503 g.), Metropolitan clerk Sudok (under 1504), peasant Sotko (under 1565), Kargopol patrimony Sotko Grigoriev son of Dvoryaninov (XVI century). In addition to the name and patronymic, the chronicles, unfortunately, do not provide any information about the builder of the church of Boris and Gleb, in connection with which M.K. Karger even wrote that “the identification of this noble boyar, whose name is mentioned in the annals“ with the fatherland ”, with the epic guest Sadko, long accepted in historical and archaeological literature, still requires serious justification.”

D.S. Likhachev rather unsuccessfully tried to justify this by the size of the building. According to him, “the Church of Boris and Gleb, until its destruction in the 17th century, was the largest church in Novgorod, the only one that surpassed in its size the patronal church of Novgorod - Sophia” and therefore “around the construction of the Church of Boris and Gleb - so unusual in its size in Novgorod - legends were created. The erroneous opinion that the temple had such a huge size can be based on only one circumstance. Image of the Novgorod Detinets on the Khutyn Icon of the 16th-17th Centuries. shows the Church of Boris and Gleb larger than St. Sophia Cathedral. However, in the same image, Sofia is also surpassed by the belfry, which has survived without significant alterations to this day and whose real dimensions cannot be compared with the St. Sophia Cathedral. It has long been known that the ratio of the size of individual images on ancient Russian icons and miniatures is completely arbitrary. On another image of the Novgorod Detinets, approximately the same time (XVII century), the temple of Boris and Gleb looks several times smaller than Sophia. Other images of the church of Boris and Gleb, except for these two, have not been preserved.

Archaeological excavations unearthed its foundation. It turned out that the area of its foundation was half the area of the foundation of St. Sophia Cathedral. Thus, the real size of the Church of Boris and Gleb does not give reason to assume that its exceptional size caused the creation of legends about its construction, since no legends about the construction of the much larger St. Sophia Cathedral have been preserved. But still, according to archaeological data, the temple of Boris and Gleb was "an exceptionally monumental structure, not inferior in size to one of the most majestic buildings in Novgorod - the Cathedral of St. George in the princely Yuriev monastery." It is appropriate to recall that 40 years before Sotko Sytinich began to build the temple of Boris and Gleb, a revolution took place in the city. Novgorodians deprived of power and expelled their prince Vsevolod Mstislavich (grandson of Vladimir Monomakh). The Novgorod principality actually became a republic, often shaken by internecine clashes between city parties, although the Novgorodians later invited princes, however, greatly limiting their prerogatives. The struggle for power between the opposing factions, sometimes reaching crowded bloody battles, lasted 350 years: until the abolition of the republican system by Ivan III, who completed the unification of the Russian lands, annexing Novgorod to the Muscovite state. Soon he destroyed the Tatar-Mongol yoke, which lasted two and a half centuries, and was established due to the lack of unity among the then rulers of Russia used by the enemies.

As you know, the princes Boris and Gleb (sons of St. Vladimir), treacherously killed in 1117 by their brother, who sought sole power, were officially canonized by the Russian Church as saints already in 1171. Their killer, Svyatopolk, received the title of the Cursed, and Saints Boris and Gleb became a religious symbol of opposition to internecine strife, spiritual patrons princely family sanctifying the principle of the inviolability of hereditary rights. The erection in the center of medieval Novgorod, in its citadel, of an imposing temple dedicated to these saints (even before their official canonization) could not but have then an important symbolic meaning. This should have been perceived there as a condemnation of bloody strife, and perhaps as a manifestation of sympathy for the princely dynasty, whose members precisely here no longer had real power.

The epics speak differently about the reasons for building the church. The earliest record came in the famous Collection of Kirsha Danilov. As in a number of other variants, here Sadko competes in wealth with Novgorod: he undertakes to buy up all the goods of Novgorod merchants. In some versions of the epic he succeeds, in others he does not. According to the text of Kirsha Danilov, Sadko wins the match three times. Each time he gives thanks to heaven by building a temple. Bylina, thus, reports on the three churches that Sadko built. This indicates that he was well remembered as an outstanding temple builder, although the majestic church, actually built at his expense, had not existed for a long time already by the time the epics began to be written down. But popular memory attributed to Sadko the construction of the St. Sophia and St. Nicholas Cathedrals, erected in fact by the Novgorod princes at the time when they were still sovereign rulers of Novgorod. From Kirsha Danilov we read:

And God wetted him in a zealous heart:

Shed Sadko, built God's temple,

And in the name of Saphea the Wise,

Crosses, poppies gilded with gold,

Mestia adorned the icons,

He embellished icons, seated them with pure pearls,

He gilded the royal doors.

In the same expressions, the epic tells further about the construction of a temple in the name of St. Nicholas. It turns out that already more than 400 years ago, popular rumor began to attribute to the builder of a magnificent church in honor of the blessed princes-martyrs Boris and Gleb that he was involved in the construction of the oldest princely cathedral - St. Sophia, which became the state symbol of Novgorod. The chroniclers of the 12th-15th centuries correctly pointed out that the creator of this temple was the son of Yaroslav the Wise. But compiled at the end of the XVI century. The Novgorod 2nd chronicle reports under 1045: “Lay the foundation of Prince Volodnmer Yaroslavich and Vladyka Luke of St. Sophia of stone in Veliky Novgorod, Sotko Sytinich and Sytin.” The chronicler rewrote the main part of the text from his ancient source, and obviously made the addition on the basis of the epic. It is historically unreliable, since more than 120 years passed between the construction of the St. Sophia Cathedral and the temple of Boris and Gleb, but it shows how trusted the oral epic was in those days.

Another example is the addition of the church of Boris and Gleb in the news about the construction by Sotko Sytinich. In the Novgorod chronicler, discovered by A. N. Nasonov in a manuscript of the middle of the 16th century, it is said about this church that it was built by “Weaving the Rich”. We find the same replacement of “Sotko Sytinich” with “Sotko rich” in the Novgorod Uvarov chronicle, compiled at the end of the 16th century, and in all subsequent Novgorod chronicles dating back to it: in the Novgorod 3rd edition of both editions, the Novgorod Zabelinskaya, Novgorod Pogodinskaya all three editions (the original edition of this latter in one case out of two gives a “compromise” reading: “Sotko Sotich rich”). The alteration of "Sotko Sytinich" to "Sotko rich" was, obviously, a consequence of the chroniclers' confidence that Sotko Sytinich is the same "Sadko rich guest" that is sung in epics.

4

The epic stories about Sadko make up a small cycle of three works. In oral existence, they were performed by folk singers sometimes separately, but more often in different combinations two epics, combined into one, and occasionally - all together in one performance. Since most of the records contain contamination of plots about Sadko, the previous works on the Russian epic were, as a rule, talking about one epic dedicated to him, although transmitted by singers from varying degrees completeness and consistency. However, they noted the inconsistency in the plot composition of the available variants, the difference in time between the appearance of individual parts. Works by V.F. Miller, A.N. Veselovsky and other epic scholars clarified this even before the beginning of the last century. But the thesis itself independent origin each of the three plots was put forward quite clearly more than four decades ago in an article by B. Meridzhi A shortly after T.M. Akimova, having carefully examined all the records introduced by that time into science, convincingly proved that they represented not one epic dedicated to Sadko, but three.

The construction of the temple is not only in the center of the epic about the competition between Sadko and Novgorod. It also passed into another epic about him, dedicated to the journey to the bottom of the sea. In its variants, usually the hero, who went down to the water to propitiate the sea king, ends up in the underwater kingdom; it is possible to return from there thanks to the advice of St. Nicholas. To him, in gratitude, according to his promise, Sadko then builds a church. But again, attention should be paid to the oldest recording of Kirsha Danilov. There is no such promise here, and it is clear from the text that Sadko belonged to the parishioners of this church, which already stood in Novgorod before he set sail: having followed the advice of St. Nicholas from the sea king -

From sleep, Sadko tried to shrink.

He found himself under the New City,<...>

He recognized the church - the arrival of his own,

Tovo Nikola Mozhayskov,

He crossed himself with his cross.

The name of the Borisoglebskaya church was forgotten in the epics. One of the main researchers of epics about Sadko A.N. Veselovsky suggested that it was replaced by the name of the St. Nicholas Church because of the well-known proximity between St. Nicholas and St. Boris and Gleb, according to the time of their church honoring and according to some folk ideas about them. The name of St. Nicholas eventually became especially popular in Novgorod, where there was a “brother Nikolytsin” (where the epic Sadko enters) - a merchant community, whose heavenly patron was St. Nicholas. He was also the patron saint of seafarers, and Sadko, according to the most common of the epics about him, conducted overseas trade, and the caravan of his ships almost died from a storm, but Sadko escapes, following the advice of St. Nicholas. As the epic evolved, the idea appeared in it that “Sadko the Rich” erected a church specifically for St. Nicholas. According to A.N. Veselovsky, “at this stage of development, the legend was further complicated by the dark elements of a fairy tale, which are filled, with the exclusion of the episode about Nikola, bylinas that have come down to us.”

Epic stories about the sea king and his influence on the fate of Sadko, of course, are of fabulous origin. They acquired the most developed form with the advent of another epic about Sadko: a poor gusler on the banks of the Ilmen delighted the lord of the water element with his game and for that he received wealth from him. This became, as it were, a preamble to the main epic about the competition between the rich Sadko and Novgorod (although there are other epic variations a tsy l in explaining how Sadko got rich). The final one in the resulting cycle was the very epic where Sadko, forced to thank the sea king for his wealth, falls to the bottom, here he must entertain him with his game, then choose his bride, risking staying here forever, if not for the wise advice of the saint, allowed to return to Novgorod. Thoroughly studied the epic about Sadko V.F. Miller rightly considered the central plot, where Sadko competes with Novgorod, to be primordial: the narrative could be based on historical reality. Not only in Kirsha Danilov, but also in a number of other recordings, it is precisely this plot that depicts its hero as a temple builder. As V.F. Miller, "the chronicle does not call Sadko a trading guest, but it is easy to assume that the historical Sadko acquired his wealth, which gave him the means to build a stone temple, like other rich Novgorodians, through extensive foreign trade." The scientist believed that there was a "Novgorod tradition that formed the basis of the epic"; later, “fabulous motifs” were attached to the name of this historical person.

Possible sources of such motifs were indicated by Veselovsky, Miller and other researchers in the folklore of not only the Slavic peoples, and close parallels turned out, in particular, among the Karelians living in the same places where the epics about Sadko were especially intense. The game of the hero on the harp in the underwater kingdom, for example, was explained by the influence of the Karelian-Finnish runes. But the most interesting parallel, which drew the attention of A.N. Veselovsky, was found in a French medieval novel. His hero named Zadok, sailing in a storm on a ship, is forced by lot to throw himself into the sea (as the culprit of danger) so that his companions do not die; after that, the storm subsides, and Zadok himself is saved. This is the same scheme of the plot in the third epic about Sadko. As Veselovsky suggested, "both the novel and the epic, independently of each other, go back to the same source." This source has not yet been discovered. But it is quite obvious that the folk singer, who knew the epic about Sadko, naturally perceived such a work as a story about other adventures of the same hero. The intensive overseas trade of ancient Novgorod gave wide scope for the international exchange of folklore stories, V.F. Miller wrote that the mentioned episode about Zadok, due to the coincidence of names, influenced the epic that has come down to us. The scientist believed that the image of Sadko the merchant was later expanded by the idea of him as a harpist. The fact is that playing the harp is not mentioned in one of the two epics about him by Kirsha Danilov: Sadko receives wealth from Ilmen Lake, having served him not as a harpist. Miller knew another entry, where it is even about Sadko's stay with the sea king, offering the hero a bride, but there is no playing his harp. True, this text is without a beginning. However, after Miller's death, two more interesting versions of the epic about Sadko's stay with the sea king were recorded. Here's a good start:

Sadko also lived a merchant, a rich guest.

Not a few times Sadko ran a shaft across the sea,

The sea king did not give anything.

Here, too, we are talking about the bride, but there is also no question that the hero is a harper. It is not necessary to explain this by later oblivion: both versions were recorded in the Siberian polar village of Russkoe Ustye, where for centuries the old folklore tradition was preserved in isolation, which was brought by the Novgorodians who, according to their legends, moved here back in the time of Ivan the Terrible. There are Russian mythological stories recorded in different places about how the hero became rich thanks to the water man. Some of them are close to the story of getting rich without the help of playing the harp in the epic about Sadko. There are also stories where we are talking about an alleged marriage to the daughter of a vodnik, in contrast to the epic, where the hero managed to avoid this marriage.

The fabulous and mythological details in the epics about Sadko are the result of a complex and, probably, long interaction between ancient Russian and non-Russian folklore plots and the historical grain that underlay the oral narrative about the Novgorod builder of the famous temple of the XII century. In epics, he also became famous as a gusler - like another popular hero of our epic Dobrynya Nikitich, although the historical prototype of the epic Dobrynya was not a wealthy Novgorodian of the 12th century, but a statesman and military leader of the 10th-11th centuries, connected by his biography with Novgorod. But, unlike Dobrynya Nikitich or Stavr Godinovich, the epic Sadko is a professional gusler, which was also noted by V.F. Miller. He rightly wrote about the presence of "traces of buffoon processing" mainly in "epics-short stories" depicting "incidents of urban life." The trilogy about Sadko, which belongs to their number, is the most striking evidence of the contribution that, obviously, the Novgorod buffoons made in equipping the historical basis of epic songs with fabulous episodes from their heterogeneous repertoire of professional harpists.

5

The dispute about how the epics about Vasilin Buslaev correlate with chronicle news is of considerable length. More I.I. Grigorovich, in his “Experience on the Novgorod Posadniks,” had no doubt that the “posadnik Vaska Buslavich,” whose death the Nikon Chronicle reports in 1171, was a historical figure. N.M. Karamzin treated this chronicle news ironically. In contrast to him, S.M. Solovyov wrote, with reference to the Nikon chronicle, that “in ancient Russian poems from the faces of historical<...>is the acting Novgorodian Vasily Buslaev. I.N. argued this point of view. Zhdanov, pointing out that the Novgorod chronicles do not know such a posadnik, and "the lists of Novgorod posadniks do not mention him either." V.F. Miller and A.V. Markov (and later A.I. Nikiforov), on the contrary, saw no reason to doubt the authenticity of the Nikon chronicle. S.K. Shambinago, noting that “the Nikon Chronicle often uses song material for its inserts”, and in the oldest chronicle of Novgorod - Novgorod 1st - “there was no such posadnik” (in 1171, Zhiroslav was the posadnik, according to this chronicle), and ((Other chronicles do not mention Vaska at all,” concludes that this news from the Nikon Chronicle “does not match reality.”

A.N. Robinson not only did not doubt the authenticity of the annalistic news, but also dated, following V.F. Miller, on the basis of this news, the epics themselves: “The Nikon Chronicle,” he writes, “under 1171 marks the death of the “mayor Vaska Buslavich,” on the basis of which the epics about him can be attributed to the 12th century.” D.S. Likhachev , accepting this dating and repeating the main arguments of his predecessors in favor of the folklore origin of the chronicle news, he wrote: “The form of the mayor’s name (“Vaska”), unusual for the chronicle, but common for epics about him, also indicates that this news was taken from the latter” However, D.S. Likhachev's own argument is untenable: the same diminutive names of Novgorod posadniks (Ivanko Pavlovich, Mikhalko Stepanich, Miroshka Neznanich, Ivanko Dmitrievich, etc.) constantly appear in the annals. At present, there is an indication of Vasily Buslaev not in one, but in essence in three chronicles.This is, firstly, the Nikon Chronicle (under 1171): ik Vaska Buslavich"; The Novgorod Pogodinsky chronicle, in its original edition (under the same year): “The same year, the posadnik Vasily Buslaviev reposed in Veliky Novgorod”, and, finally, the abridged version of the same chronicle (also under 1171): “The same summer, the posadnik Vasily Buslaviev reposed posadnik Vaska Buslaviev in Novegrad.

Both editions of the Novgorod Pogodin Chronicle belong to the last quarter of the 17th century. None of the Novgorod chronicles that preceded it (and now there are eight of them, apart from short chroniclers, some of which came in several editions) contains such news, as well as any mention of Vasily Buslaev at all. There is also no information about him in any of the published Nenovgorod chronicles, except for Nikonovskaya, compiled in the middle of the 16th century. There is reason to believe that this news came to the Novgorod Pogodinskaya chronicle from Nikonovskaya (directly or indirectly), since there is no such news in the Novgorod sources of the Novgorod Pogodinskaya chronicle - in the Novgorod Zabelinskaya and Novgorod 3rd chronicles. In Nikonovskaya itself, it is placed immediately after the story about the victory of the Novgorodians over the Suzdalians, which goes back to the texts read in the Novgorod chronicles, which have come down to us and do not mention Buslaev. Carefully compiled lists of Novgorod posadniks, which have come down as part of the Novgorod 1st chronicle according to a 14th-century manuscript, do not contain the name of Vasily Buslaevich (or Boguslavovich). This applies not only to the time around 1171, but also to all the posadniks preceding this year, which is significant, since if the news of the death of "Vaska Buslavich" in 1171 was reliable, it would not necessarily mean the death of a sedate posadnik (t e. who sent his post in 1171), as S. K. Shambinago thought; Novgorod posadniks continued to bear this title even after they ceased to perform posadnik functions.

The lists of posadniks include several persons bearing the name of Vasily, but all of them date back to no earlier than the middle of the 14th century. Not a single posadnik was named at all, whose patronymic even remotely resembled "Buslaevich" or "Boguslavovich". The consideration of P.A. Bessonov that Vasily could "hide" in the early Novgorod chronicles under a pagan name: the news of the Nikon chronicle should have been traced back to one of these early chronicles. However, it has long been proven that it was the Nikon Chronicle that included information gleaned from folklore sources. This leads us to believe that the same source owes its origin to her mention of "Vaska Buslavich". I.N. Zhdanov assumed that there was a plot where Vaska becomes a posadnik. If such a plot really existed in it, as well as in a possible source of V.A. Levshin (see below), Sadko was mentioned, then there is nothing surprising if the chronicler familiar with this plot considered it best to place the news of the death of the "mayor Vaska Buslavich" in chronological proximity to the news of Sotko Sytinich, whom he naturally identified with folklore Sadko. The attention of the Nikon Chronicle to epic heroes and even to folklore characters that are absent in the works of oral tradition that have come down to us, but, obviously, appeared there before, is a fact that sufficiently justifies such an assumption (not excluding, of course, the possibility of a real basis).

Although, unlike the epic Sadko, the epic Vasily Buslaev has not yet been correlated with a well-defined historical prototype, there are fairly close historical parallels. Particularly interesting material of this kind was considered by B.M. Sokolov, commenting on the epics about Buslaev and Sadko in an anthology of 1918, rarely used due to the small circulation. Two epics about Vasily Buslaev - about his quarrel with the Novgorodians and about a trip to Jerusalem, known in a significant number of records, were sometimes combined by storytellers into one. There were no other works of epic epic about this hero, but it can be assumed that if not epics, then legends about Vasily Buslaevich, the content of which is not covered by surviving epics, existed. This is evidenced by the reflections of folklore about this hero in the Icelandic epic, to which the work of V.A. Brima. Comparing the Icelandic and Russian material, the author came to the conclusion that there must have been a legend about the campaign of Vasily Buslaev to the East. It was reflected in the Bosa-saga, the older version of which, represented by a significant number of manuscripts, appeared not earlier than the 14th century. and has similarities with both the first and the second epics. Another piece of evidence is The Tale of the Strong Bogatyr and the Old Slavonic Prince Vasily Boguslaevich, composed by V. A. Levshin in the second half of the 18th century. based on folklore. As I wrote

A.M. Astakhov, "for the history of the Russian epic epic" Levshin's Tale is of great interest as a reflection of one of the oral versions of the XVIII century epic about Vasily Buslaev. And although “the direct source of the Tale is unknown to us”, and she herself “is not a simple retelling of the epic”, but “ literary work based on epic material”, its text contains “details that are known in subsequent oral tradition”. It is impossible to attribute to the version that Levshin used, all the details of the Tale missing in it, but among them there were almost certainly those that reflected the features of this particular oral source. It is curious that in Levshin's text, "Sadko's rich guest" appears among the secondary characters, and Vasily himself eventually becomes the prince of Novgorod and the ruler of the entire Russian land.

Epics about Sadko and Vasily Buslaev provide useful illustrations of the results of studies of the socio-political structure of Novgorod, which in recent decades have been significantly enriched with the most valuable materials obtained as a result of unprecedented archaeological discoveries. Despite the changes that introduced a lot of fairy tales into the epics about Sadko and gave rise to several semantic ambiguities, dark places in the epics about Vasily Buslaevich, both here and there many character traits the social life of Novgorod in the 12th-15th centuries: mortgages, brotherhoods, the recruitment of a squad by a young boyar, the battle on the Volkhov bridge caused by the struggle for power, the huge scope of trade, pilgrimages to the Holy Land - all this, like many other things, reflected brighter and more fully the real life of ancient Novgorod than the sometimes somewhat schematized paintings ancient Kyiv in epics about the exploits of his heroes.

Outside the general cyclization around Prince Vladimir, only the epics of the Novgorod cycle remained, for which there were deep reasons both in the very history of the veche republic - and in the fact that the Novgorod Russ descended from the Baltic branch of the Pomeranian Slavs (Venedi). Apparently, it is in their mythology that the origins of the epics about Sadko go (the wife from the "other world", the magical ability to play the harp, etc. - evidence of the deep antiquity of the plot). In Novgorod the Great, the epic underwent significant processing, almost being created anew. Figurative details were found of extreme brightness, reproducing the greatness of the veche trading republic, even the one that the wealthy Sadko tries to buy up all Novgorod goods, but cannot buy up. The next day, the malls are again filled with piles of goods brought from all over the world: “But I can’t redeem goods from all over the world! - decides the hero. “May I not be rich, Sadko, a trading guest, but richer than me, Lord Veliky Novgorod!”

All this: both immoderate boasting, and the luxurious chambers of the former harpist Sadko, and this grandiose dispute - are also reproduced by means of epic exaggeration, that is, the style of the epic does not change, despite the absence of military heroism in this case.

Bylina about Vasily Buslaev (more precisely, two, as well as about Sadko), researchers usually attribute to the XIV-XV centuries, to the time of the Ushkuy campaigns, which in no way correlates with the data of the plot. The legendary Vaska Buslaev, who even got into the annals with the title of posadnik of Novgorod, according to the same legends, lived long before the Tatar invasion, and, according to the epic, he did not go on an ear campaign at all, but to the Jordan, adding at the same time: plundered, under old age it is necessary to save the soul! And the trips to the Holy Land, repeatedly undertaken by the Novgorodians, fall on the same pre-Mongolian XI-XII centuries. That is, the addition of the plot took place in the same "Kyiv" terms as the processing of epics about the heroes of Vladimirov's circle.

Novgorod the Great was founded at the beginning of the 8th century and arose as a union of three tribes: Sloven, who advanced from the south, from the Danube border (they led the union, bringing with them the tribal name "Rus" to the north); Krivichi and Pomeranian Slavs - these moved from the West, pressed by the Germans; and the local Chud tribe. Each tribe created its own center, which formed the city "end": Slavna - on the right bank of the Volkhov, where there was a princely residence and city bargaining; Prussian, or Lyudin, end - on the left, where Detinets later arose with the church of St. Sophia; and the Nerevsky (Chudskoy) end - also on the left bank, downstream of the Volkhov (later two more ends stood out: Zagorodye and Plotniki).

This origin of the city predetermined the protracted Konchan struggle, and Slavna more often relied on the “Nizovsky” princes, the “Prussians” - on the Lithuanian ones. And although the population was completely mixed over time, the strife of the city ends was torn apart Novgorod Republic until the very end of its existence. According to an oral legend, the overthrown Perun, sailing along the Volkhov, threw his staff on the bridge, bequeathing the Novgorodians to fight here forever with each other. During city troubles, two veche gatherings usually gathered on this and that side of the Volkhov and fought or “stand in arms” on the Volkhov bridge.

The development of the North and the Urals by the Novgorodians was carried out mainly by separate squads of "eager fellows", whom one or another successful leader (most often from the boyars) recruited by "sentence" of the veche, or even on his own, "without the word of Novgorod". These gangs seized new lands, collected tribute, hunted the beast, founded fortified towns, and traded. The collection of such a squad of "eager fellows" is vividly shown in the epic about Vaska Buslaev, where, apparently, the main epic heroes of Veliky Novgorod, the "freemen of Novgorod" were listed. (This list, unfortunately, was already forgotten by storytellers.)

The epic about Buslaev is expressive in the sense that instead of the military heroism common in any epic, fights with external enemies, repelling enemy armies and withdrawing beauties, it puts internal social conflicts veche republics, concentrated here - according to the laws of the epic genre - for many centuries. Here is the gathering of squads from "eager fellows", and the battles on the Volkhovsky bridge, and "hardened widows" - the owners of large properties (the figure of Martha Boretskaya is symptomatic specifically for Novgorod). Actually, the third Novgorod epic - “Khoten Bludovich” is dedicated to the dispute of two similar sovereign boyars.

Vasily Buslaev, in all his reckless and daring nature, is in this enthusiasm when he crushes opponents on the Volkhov Bridge, when he suddenly says repentantly: “From youth, a lot was beaten, robbed, in old age one must save one’s soul”; in the subsequent heroic trip - walking to Jerusalem, in mischievous behavior on the Jordan, in his last dispute with a dead head, a dispute-death (the stone through which Basil jumps is a probable exit to the afterlife, that is, the end, destruction, lurking in his hour and the strongest of the strong), - in all this, Buslaev developed into such a truly Russian hero, as if bequeathed to the future (were his features reflected in the explorers, conquerors of Siberia, leaders of Cossack campaigns and uprisings?), which is still the appearance, his image and fate excite him almost more than the images of ancient epic warriors, not excluding Ilya Muromets himself.

Novgorod epics did not develop military themes. They expressed something else: the merchant's ideal of wealth and luxury, the spirit of bold travel, enterprise, sweeping prowess, courage. In these epics, Novgorod is exalted, their heroes are merchants.

Purely Novgorod hero is Vasily Buslaev. According to V.I.

small "1. This is how the hero appears. Two epics are dedicated to him: "About Vasily Buslaev" (or "Vasily Buslaev and the Novgorodians") and "Vasily Buslaev's trip."

The first epic reflected the inner life of independent Novgorod in the 13th-14th centuries. It is assumed that it reproduced the struggle of the Novgorod political parties.

Born of elderly and pious parents, left without a father early, Vasily easily learned to read and write and became famous in church singing. However, he showed another quality: the unbridled riot of nature. Together with drunkards, he began to get drunk and mutilate people. Rich townspeople complained to his mother - mother widow Amelfa Timofeevna. Mother began to scold Vasily, but he did not like it. Buslaev recruited a squad of the same fine fellows as he was. Further, a massacre is depicted, which on a holiday was staged in Novgorod by the drunk squad of Buslaev. In this situation, Vasily offered to hit on a great pledge: if Novgorod beat him with a retinue, then every year he would pay tribute-outputs of three thousand; if he beats him, then the men of Novgorod will pay him the same tribute. The contract was signed, after which Vasily and his retinue beat ... many to death. Rich men of Novgorod rushed with expensive gifts to Amelfa Timofeevna and began to ask her to appease Vasily. With the help of a black-haired girl, Vaska was taken to a wide courtyard, planted in deep cellars and tightly locked. Meanwhile, the squad continued the battle that had begun, but could not resist the whole city and began to weaken. Then the black-haired girl undertook to help Vasily's squad - she beat a lot to death with a yoke. Then she released Buslaev. He grabbed the cart axle and ran along the wide Novgorod streets. Along the way, he came across an old pilgrim:

There is an old pilgrimish here,

He holds a bell on his mighty shoulders,

And that bell weighs three hundred pounds ...

But even he could not stop Vasily, who, having entered the fervor, hit the old man and killed him. Then Buslaev joined his squad: He fights and fights day and night. Buslaev defeated the Novgorodians. The peasant peasants submitted and reconciled, brought expensive gifts to his mother and pledged to pay for every

three thousand a year. [TO. D. - S. 48-54]. Vasily won a bet with Novgorod, like Sadko the merchant in one of the epics.

The epic "Vasily Buslaev's Journey" tells about the hero's journey to Jerusalem-city in order to atone for sins. However, here, too, his indomitability manifested itself ("And I, Vasyunka, do not believe in sleep or chokh, but I also believe in my scarlet elm"). On Mount Sorochinskaya, Vasily blasphemously kicked a human skull out of the way. In Jerusalem, despite the warning of a forest woman, he swam in the Yerdan River with his entire squad. On the way back, he again kicked a human skull, and also neglected the inscription on some mystical stone:

"And someone de at the stone will amuse himself,

And have fun, have fun

Jump along the stone, -

It will break a wild head."

Vasily jumped along the stone - and died. [TO. D. - S. 91-98]. Thus, he failed to fulfill pious intentions, remained true to himself, died a sinner.

Another type of hero is represented by Sadko. V. G. Belinsky wrote about him: “This is no longer a hero, not even a strong man and not a daring man in the sense of a bully and a man who gives no one and nothing a descent; this is not a boyar, not a nobleman: no, this is strength, prowess and money wealth, this is the aristocracy of wealth acquired by trade - this is a merchant, this is the apotheosis of the merchant class.<...>Sadko expresses his infinite prowess; but this strength and prowess are based on endless funds, the acquisition of which is possible only in a trading community" 1 .

Three stories are known about Sadko: a miraculous acquisition of wealth, a dispute with Novgorod, and being at the bottom of the sea king. Usually two or all three plots were performed in a contaminated form, like one epic (for example: "Sadko" [Gilf. - Vol. 1. - P. 640-657]).

The first story has two versions. One by one, the merchant Sadko came from the Volga and conveyed greetings from her to the lacrimal lake Ilmen. Ilmen gifted Sadko: he turned three cellars of the fish he caught into coins. According to another version, Sadko is a poor gusler. He was no longer invited to feasts. With grief, he plays the gusli of the spring on the shore of Lake Ilmen. The king of the water came out of the lake and in good

gratitude for the game taught Sadko how to get rich: Sadko must hit the great pledge, claiming that there are fish-golden feathers in Ilmen Lake. Ilmen gave three such fish in the net, and Sadko became a rich merchant.

The second story also has two versions. Enraged at the feast, Sadko wagers with Novgorod that he can redeem all Novgorod goods with his innumerable gold treasury. According to one version, this is exactly what happens: the hero buys even shards from broken pots. According to another version, more and more new goods arrive in Novgorod every day: either Moscow or overseas. Goods from all over the world cannot be redeemed; no matter how rich Sadko is, Novgorod is richer.

In the third plot, Sadko's ships are sailing on the sea. The wind blows, but the ships stop. Sadko guesses that the sea king demands tribute. The king does not need red gold, or pure silver, or small scat pearls - he requires a living head. Thrice cast lots convinces that the choice fell on Sadko. The hero takes with him the gooselets of the yarovchata and, once on the seabed, amuses the king with music. From the dance of the sea king, the whole blue sea shook, ships began to crash, people began to drown. The drowning people offered prayers to Nikola Mozhaisky, the patron saint of the waters. He came to Sadko, taught him how to break the harp to stop the dance of the sea king, and also suggested how Sadko could get out of the blue sea. According to some options, the rescued Sadko erects a cathedral church in honor of St. Nicholas.

It is difficult to see real historical features in the image of Sadko. At the same time, the epic emphasizes his prowess, which truly reflects the color of the era. The brave merchants who crossed the expanses of water were patronized by the deities of rivers and lakes, and the fantastic sea king sympathized.

The image of the Novgorod merchant shipbuilder naturally fits into the system of all Russian folklore. Nightingale Budimirovich sails to Kiev on his expensive ships. Ilya Muromets and Dobrynya Nikitich (Ilya Muromets on the Falcon-ship) are sailing on the Falcon-ship on the blue sea. The fairy tale "Wonderful Children" (SUS 707) in its original East Slavic version also created a vivid image of merchant shipbuilders and trade guests. This image is also found in other East Slavic fairy tales 1 .

Kievan Rus actively used water trade routes. M. V. Levchenko described the structure of the ships of the ancient Russian fleet. "Rooks until

tyye", accommodating from 40 to 60 people, were made from a dugout deck, sheathed with boards (later the Cossacks built their ships in the same way) 2.

VF Miller attributed to Novgorod - according to a number of everyday and geographical features - the epic "Volga and Mikula" 3 . The regional orientation of this work was reflected in the fact that the Novgorodian Mikula is depicted as stronger than the nephew of the Kiev prince Volga with his retinue.

Volga went to the three cities granted to him by the Kyiv prince to collect tribute. Having gone out into the field, he heard the work of the oratay: the oratay urges, the bipod creaks, the omeshiki scratches on the pebbles. But Volga managed to approach the plowman only two days later. Having learned that in the cities where he was going, peasants live ... robbers, the prince invited the yelling with him. He agreed: unharnessed the filly, sat on it and rode off. However, he soon remembered that he had left the bipod in the furrow - it must be pulled out, shaken off the land and thrown behind the willow bush. Volga sends warriors three times to remove the bipod, but neither five, nor ten good fellows, nor even the whole good fellow, can lift it. Plowman Mikula pulls out a bipod with one hand. The opposition also extends to horses: Volga's horse cannot keep up with Mikula Selyaninovich's filly.

The image of Volga was somewhat influenced by the image of the mythical Volkh: in the beginning it is reported that Volga can turn into a wolf, a falcon bird, a pike-fish. [Gilf. - T. 2. - S. 4-9]. This gave reason to build an archaic basis of the plot to a conflict between an ancient hunter and a more civilized farmer. However, the idea of the epic, first of all, is that the prince is opposed by a wonderful plowman, endowed with mighty strength.

Until now, the people in their songs recall the unbridled freemen of Novgorod, and folk fights, as well as the former glory and wealth of Novgorod.

In one Novgorod epic (Vasily Buslaevich) a violent daring freeman is depicted.

“In the glorious Veliky Novgorod, the epic says, old Buslai lived for ninety years, he lived with everyone in peace and harmony, got along with the rabble of Novgorod, did not say a word across her. He died and left behind him a great estate, his widow and a small child, Vasenka. The mother gave her son to teach reading and writing, writing and church singing. The teaching went well for him, and in all Novgorod there is no such singer as Vasenka; yes, unfortunately, he got into the habit of feasting with merry daring fellows. He drinks, he gets drunk, he walks the streets and jokes unkind jokes: he will take someone by the hand - he will dislocate his hand, he will grab someone by the leg - he will twist his leg ... Novgorod men go to complain to Vasya's mother. “Honest widow,” they say to her, “take your sweet child! He began to joke bad jokes! And then, after all, with such valiant luck, he should be in the Volkhov River! The mother began to scold her son. Vasenka did not like this: he got angry at the peasants who complained about him and threatened to drown him on the Volkhov. He decided to gather a brave squad for himself. He writes “labels (notes) are cursive”: “Whoever wants to drink and eat from ready-made, fell to Vaska on a wide yard - he drink and eat ready-made and wear a multi-colored dress.” He sends these labels through the streets and lanes of Novgorod. Daredevils from all over gather to him: Kostya Novotorzhenin came, Potanyushka Lame, Khomushka Humpbacked and others came. Vasenka Baslaevich tries their strength - he makes them drink a cup of green wine for one and a half buckets, beats each of them with a club of twelve pounds. If the fellow stands at the same time, does not move, Vasenka fraternizes with him and accepts him into "his brave squad." He scored thirty daredevils for himself.

Then he calls all the men of Novgorod to fight. They accept the challenge. A dump begins on the Volkhov bridge. It's bad for the Novgorod peasants - many of them are beaten, wounded; Vasiliev's squad overcomes them. They see - it's bad - they embark on tricks. They ran to Vasily’s mother, brought gifts and asked: “Accept our expensive gifts and take care of your dear child!” The mother appeases her son, puts him in a deep cellar; Vasenka submits to her - he does not dare to disobey his dear mother. The squad had a bad time without him; Novgorod men began to overcome her. Then Vasily is released from the cellar.

His heroic heart flared up, he grabbed the axle of the cart and rushes to his aid - the peasants are like a shaft and bring down. They again began to ask their mother to intercede for them. She sends Vasiliev the cross father to appease her son. The elder-pilgrim puts on a twenty-pound cap on his head, takes a stick in his hands, ten pounds, comes to the bridge to Vasily, looks straight into his clear eyes and says to him: “Ah, you, my godchild! Tame your heroic heart, leave the peasants at least a small part.

Vasenka's heart was breaking: I can't keep a lot of money on him. “Oh, you, my godfather, father! he says in response. “I didn’t give you an egg on Christ’s day, I will give you an egg on Peter’s day!” He clicked the father of the godfather with an iron axle, - here the glory of the godfather is sung. The mother herself comes to appease Vasenka, who was at odds; the old woman guessed, went behind him and fell on his mighty shoulders. “Ah, my dear child,” she says, “tame your heroic heart, leave the peasants at least a small part!”

Here Vasilyushka Buslaevich lowers his mighty hands to the damp earth, the iron axle falls out of his white hands. “Oh, you, the light-empress mother,” he says, “you knew how to appease my great strength, you guessed to go behind me, and if you had gone in front, you would not have let down the empress mother, you would have killed you instead of a Novgorod peasant” . Then Vassenka leaves the mortal massacre. He left a small part of the peasants, and stuffed them that it was impossible to get through.

Vasily Buslaevich did a lot of trouble and sins. “A lot has been beaten from youth, plundered, in old age it is necessary to save the soul,” he says and asks his sovereign mother for a great blessing “to go to Jerusalem city with your brave retinue, pray to the Lord God, venerate the holy shrine, in the Yerdan River bathe." “My dear child,” his mother answers him, “if you go to good deeds, I will give you a great blessing, and if you, child, go to robbery, and I won’t give you blessings, don’t wear Vasily the damp earth! .. » Vasily and his retinue set off on a long journey along rivers and seas. He finally arrives in Jerusalem, serves mass for his mother, for himself, serves a memorial service for the father, bathes in the Jordan. On the way back, Vasily dies. He saw a large stone on the mountain; it is written on it: "Whoever jumps across the stone across - nothing will happen to him, and whoever starts jumping along - break that violent head." Vasily's unreasonable heart caught fire, the daring boldness spoke, - he began to gallop along and killed himself to death.

Draw the Novgorod birch bark

Another epic about Sadka the Rich Guest shows that the people have preserved the memory of the wealth of old Novgorod. Pagan beliefs also affect this epic - belief in the "water god".

Lived in Novgorod Sadko. He was a harpist, went to merry feasts, entertained rich people with his skillful playing - that's how he lived. There were frequent feasts in rich Novgorod. But then it happened once - the day comes, another, third - Sadok is not invited to the honors feast. Sadko got bored, he went to Ilmen Lake, sat down on a coastal stone and began to play on his guselkas. Suddenly the water in the lake stirred; the king of the sea came out of the water and said: “Ah, you, Sadko of Novgorod, I don’t know how to welcome you for your great joys, for your tender game. You go to Novgorod and bet, lay your wild head, and turn out shops of red goods from merchants and argue that there is fish-gold feathers in Ilmen Lake. As soon as you bet, go tie a silk net and come to fish in Lake Ilmen. I will give you three fish-gold feathers; then you, Sadko, will be happy.” He did as the king of the sea commanded him. They called Sadko to a feast of honors. He amused the guests with his skillful game, the guests amused themselves with intoxicated wine. Here he began to boast that he knew a wonderful miracle in Lake Ilmen, that there was a fish-golden feathers in the lake. The merchants argued that there could not be such an outlandish fish in the lake. Then Sadko offers to bet. “I’ll lay down my wild head,” he says to the merchants, “and you lay down shops for red goods.” There were three merchants - they hit the mortgage. They tied a silk seine and went to fish on Lake Ilmen. They threw a thin one - and they got a golden feather fish, they threw it a second time - they got a second golden feather fish, they threw a third thin one - they got a third golden fish. There is nothing to do - the merchants gave Sadko their shops of red goods. From that time on, he began to trade, began to receive good profits; he amassed a great estate, built himself white-stone chambers, he himself began to set feasts for glory.

Once he invited guests to his feast - the abbots of Novgorod. Everyone ate at the feast, everyone got drunk at the feast, everyone boasted of boasting: some boast of countless golden treasury, some boast of valiant strength, some of a good horse, some of a glorious fatherland, some of young youth. But Sadko keeps silent. The guests began to say: “Why doesn’t our Sadko boast of anything?” He says in response: “What can I brag about? Whether my gold treasury is not thinning, the dress is not worn in color, the brave squad does not change. And to brag is not to brag about an innumerable gold treasury: with my gold treasury I will redeem all Novgorod goods, bad goods and good ones! Before he had time to utter a word, the abbots of Novgorod struck with him on a great mortgage - thirty thousand, that he could not redeem all the goods of Novgorod.

The next day, Sadko got up early in the morning, woke up his fellows, gave them gold treasuries without counting, sent them along all the trading streets, and he himself went to the living room - doubly brought goods, doubly stocked goods for the glory of Novgorod the Great. Sadko again bought up all the goods. On the third day, he again goes out with his retinue to buy goods - three times the goods brought in, three times stocked up; Moscow goods arrived. Here the rich Sadko became thoughtful - he boasted too much, apparently. “If I can’t buy goods from all over the world,” he says, “I’ll buy Moscow goods - overseas goods will arrive in time. It’s not me, apparently, the merchant of Novgorod is rich - the glorious Novgorod is richer than me! Sadko had to pay the mortgage.

He built thirty ships, loaded Novgorod goods on them; he sold them overseas, received great profits, poured barrels of red gold, pure silver. Sadko is going back to Novgorod. A marvelous marvel suddenly happened on the sea. A terrible storm arose, “it beats with a wave, tears the sails, breaks the scarlet ships, and the ships will not move from their place.” “For a century we traveled by sea,” says Sadko, “but we did not pay tribute to the sea king: it is clear that the king of the sea demands tribute from us. Orders Sadko to throw a barrel of pure silver into the sea, but the storm does not subside, and the ships all move. They throw a barrel of red gold - this does not help either. “It can be seen that the king of the sea demands a living head into the blue sea!” Sadko says. Foals are thrown twice, who will go to the blue sea. Both times the foal points to Sadko. He submits to his fate. He writes a spiritual testament: part of the estate he writes to God's churches, part to the poor brethren, part to his young wife, and the rest to his brave squad. He takes his goose with him. “Throw,” he says, “an oak board into the water—death will not be so terrible to me.” Sadko remained on the blue sea, and the ships flew like black crows - they flew to Novgorod the Great. Sadko fell asleep on an oak board, and woke up in the blue sea, at the very bottom. He saw a white-stone chamber at the bottom, went into the chamber, he sees - the king of the sea is sitting there. “Hey you, Sadko merchant, rich guest! says the sea king. - For a century you traveled by sea, you didn’t pay tribute to me, the king, and now you yourself have come to me as a present. Play your guselki yarovchata for me. Sadko began to play. How the king of the sea danced here! Sadko played for a day, played others, played third ones, and still the king of the sea danced! In the blue sea, the water stirred, it became confused with yellow sand, many ships began to be smashed on the blue sea, good things began to perish a lot, righteous people drowned a lot. In Novgorod, the people began to pray to Nicholas of Mozhaisky. Suddenly he hears Sadko - someone touched his right shoulder, and he hears a voice: “Enough for you, Sadko, to play guselki yarovchaty!” He turned around and saw: a gray-haired old man was standing. Sadko tells him: “I don’t have my own will in the blue sea - I was ordered to play.” The old man answers him: “And you pluck the strings, break the pegs, say: I didn’t have strings, but the pegs were not useful, the guselki were broken - there’s nothing else to play. The king will offer you to marry, choose the girl Chernavushka. You will be in Novgorod, with your countless gold treasury, build a church for St. Nicholas of Mozhaisky.

Sadko obeyed, did everything as the elder ordered. (Married the girl Chernavushka). There was a dining room at the bottom of the sea - a feast of honors. Sadko fell asleep on the blue sea, and woke up in Novgorod, on the steep bank of the Chernava River. He looks - his ships are running along the Volkhov. He meets his team. The squad marvels: “Sadko remained in the blue sea, he found himself ahead of us in Novgorod!” As Sadko unloaded his countless gold treasury from the ships, he built the cathedral church to Nikola Mozhaisky. Sadko no longer went to the blue sea, he began to live in Novgorod.

Thus, in the songs of the people, the old story, half and half with fiction, tells about Veliky Novgorod. The people remember the trade and wealth of old Novgorod, they remember the daring freemen, whose riots and robberies caused many troubles to the Russian land, they also remember the internal unrest in Novgorod, which ruined it ...

Selection from the database: MDK.03.02 Investments Lectures.docx, 1_Gaber_anatomy physiology and pathology of the hearing organs_Content, Weis_O.V_Physical culture and sports_abstract_1.docx, OGSE.05 FOS Russian language and culture of speech.doc, Physical culture.docx, RP Physical culture rus. docx , Organizational culture of the hotel.docx , Artamonova to treat and improve physical culture.docx , abstract of physical culture.doc , physical culture abstract.doc .Ticket number 7

Heroic epic in the history of culture. Epics of the Kyiv cycle. Plots and images

epics- works of folk heroic epic.

The heroic epic has developed among many peoples: the Finnish "Kalevala", the Scandinavian "Edda", the Caucasian "Narts", the Indian "Ramayana", the Sumerian "Gilgamesh".

The name "epic" suggests that this is a true story, a reality, they believed in it. The concept was introduced in the 19th century. the folklorist Sakharov, taking the word from the Tale of Igor's Campaign, among the people they were called old men. Bylina immediately clearly localizes the plot in time and space. Topic: the fate of the people, national identity, therefore, the epic was treated with respect. Bylina is artistic in its origin. Bylina draws not a real, but an ideological history, which the Russian people wanted to see. Bogatyrs are ideal heroes from the people's moral point of view, causing people's admiration. Zhirmunsky: "The historical past on the scale of Russian idealization".

Classical records were made in the 19th century. in the Onega region Rybnikov. Far from everyone could perform the epic (outstanding storytellers are the Ryabinins). Heroic epics - about the fight against invaders, monsters. The content of epics is more often associated with Kievan Rus. Epics date back to specific historical events: according to historical concepts - many weaknesses. Philological concept: epics should be understood in context with other works of literature. Epics are born on the basis of legends, transformed according to traditional epic models, the origins of which are in mythology. Archaic epic is deeply transformed in connection with new historical ideals. The formation of classical epics (about Vladimir) should be attributed to the 14-15 centuries - the process of centralization of the state (creation of statehood, isolation of the individual) (according to D. Likhachev). Most of the epics took shape in the Novgorod land.

Archaic epic

The archaic era is the era of the first ancestors, first creations. The cultural hero plays the role of God the creator. The epic as such arises when global historical events begin to be of interest. Archaic motifs are preserved, but their content begins to be rethought. Movement from the archaic to the history of the state. Volkh Vseslavievich (magical power - a gift of werewolf, a trip to the Indian kingdom), Svyatogor, Mikula Selyaninovich "Volga and Mikula" (Mikula wins because he is a farmer, and Volga is a hunter, agriculture was more important for the Russian people).

Plot groups:

Epics about senior heroes. Bogatyrs-magicians and giants, weighed down by their exorbitant, it is not clear why with applied force, heaviness. The idea of large-scale giants. The loneliness of the heroes, isolation from manpower (it is not clear where and where he is going). Doomed to aimless wandering and death. “Svyatogor and the Permet Handbag” (Svyatogor encroached on the universe), “Ilya Muromets and Svyatogor”, “Svyatogor and the Coffin”. Contrasting Ilya Muromets and Svyatogor. Folk fantasy creates an image of a purely external, immense, material force. Strength approaches the elements, while Ilya is endowed with strength of mind (he took from Svyatogor how much strength he needed). Without fortitude, physical strength would be offensive.

Epics about matchmaking:"Mikhailo Potyk", "Dobrynya and Marinka", "Danila Lovchanin". Bylina about Dobrynya and Marina (rethinking of the archaic poem about the search for a bride). "Ivan Godinovich", "Kozarin", "Danube". + "Russian Odyssey" - a story about Alyosha's marriage to Dobrynya's wife Nastasya Mikulichna, while he is away.

Epics about the fight against a snake or a monster

Classic epic

Plots:

Ilya Muromets and Kalin Tsar

Ilya and Idolishche

Ilya Muromets and the Nightingale the Robber

Ilya Muromets and son

Healing of Ilya Muromets

Dobrynya and the Serpent

Alyosha Popovich and Tugarin

Vasily Ignatievich and Batyga

The serpent most often lives near the river (River of Fire) or at the foot of the mountain and guards the natural elements. There was a historicization of the plot about snake fighting. Details, details lead to mythological representations, and the plots of the epic are turned in the sphere of public, history.

The epic does not become a chronicle plot about any event - it lives like a work of art.

Prince Vladimir is the Baptist of Russia. Bylina is interested in some ideal prince. In epic stories, Lithuania and the Golden Horde are equalized.

Bylina is not the embodiment of historical events (memory of the past), but the embodiment of topical issues for society. The time of the epic is the golden age. Bylina - the historical past of the people on the scale of idealization.

“The epic constructs history in its own way with characteristic spatio-temporal representations” (Putilov). Epic history opposes real history, corrects its imperfections, frees from tragic mistakes and injustice.

epic hero characteristic exclusivity.

Novichkova interprets heroic exclusivity, based on mythological culture (certain magical stories could have influenced Ilya Muromets)

"Healing of Ilya Muromets" - duality.

Heroic strength - from the pagan world. It's about about the epic, where the healing of Ilya Muromets takes place (such children were called "exchanges"). In the popular mind, you can get rid of this disease with the help of a miracle. Ilya Muromets had a real prototype.

Both pagan and Christian elements influenced the plots of epics.

Holiness (Christianity) + heroic strength (paganism) = Ilya Muromets.

The main traditions of the epic were formed in pagan motifs, but in the 15th - 16th centuries. a layer of Christian traditions begins to emerge.

Heroic service takes on the form of heroic asceticism - the word of the Christian tradition. The behavior of heroes is subject to certain ethical standards (Research of Likhachev). Kalin-tsar violates these norms.

Ilya Muromets and son. Christianization of stories. The archaic cult of strength, on which the phenomenon of heroism grows, begins to be accompanied by the idea of God's help. Bylina precedes ancient Russian lives.

“Dobrynya Nikitich and the Serpent”: Dobrynya comes across a “cap of Greek land” on the way, and with the help of this find he defeats the enemy.

The motive of twinning (the story of the murder of Danila).

Heroic epics = Kievan epics (Prince Vladimir). Bogatyrs defend Kyiv.

Ticket number 8

Epics of the Novgorod cycle. Plots and images. Novelistic epics

The action takes place in Novgorod. Novgorod is connected by the consolidated elements. Semantic inconsistencies, mystery can be explained by the clash of different worldview layers. There is more mystery in Novgorod epics than in Kyiv ones. Novgorod is the second center of Russia. He is in the north - he does not need to be protected (no heroic character, which many researchers agreed), but he trading city=> a new type of heroes => the main characters are merchants. However, the conflicts of the Novgorod epics are characteristic of the heroic epic.

V.G. Belinsky singled out the Kyiv and Novgorod cycle in Russian epics. From the second half of the 11th century Kievan state begins to disintegrate into a number of feudal principalities. In this regard, regional epic cycles begin to form. These epics reflected social contradictions, since the feuds of the princes were alien to the working people, and in response to oppression, the people rose up in revolts. So, a peculiar epic cycle arises in the Novgorod principality (epics about Sadko, about Vasily Buslaev, etc.) and in Galicia-Volynsky (epics about Duke Stepanovich, about Churil, etc.). The meaning of the epics about Sadko, as Belinsky wrote, is "the poetic apotheosis of Novgorod as a trading community." The image of Vasily Buslaev is one of the best creations of the Russian epic. In the conditions of the Russian Middle Ages, the image of a freethinker and courageous man, believing only in his own strength, could not but arouse popular sympathy.

A special category of novelistic epics are epics of the Novgorod cycle. They differ from Kyiv themes that they do not have “epic time”, Prince Vladimir and a heroic theme, it is for this reason that some scientists do not recognize the heroic character in the heroes of the Novgorod epics. So, A.V. Markov(Alexey Vladimirovich) wrote that Novgorod did not develop a single typical hero. But the conflicts of the Novgorod epics are characteristic of the heroic epic.

D.S. Likhachev(Dmitry Sergeevich) noted that just as the time of Vladimir Svyatoslavovich in the Kyiv epics seemed to be a time of "epic opportunities" in the military sphere, so the time of veche orders in Novgorod epics seemed to be the same time of "epic opportunities" in the social sphere.

HeroesNovogorodskepics are Vasily Buslaev and Sadko.

At the heart of the epic about Sadko lies the ancient fairy-tale motif of courtship to the daughter of the sea king, but it is transformed by the addition of other epic motifs to it.

At first, Sadko is a poor harpist playing at feasts. Once he was not invited to the feast:

Sadka is not invited to an honorable feast,

Another is not called to an honorable feast,

And the third is not invited to an honorable feast.

and he goes to the shore of Lake Ilmen and plays there so expressively that the sea king offers Sadko a reward. Sadko has to argue with the Novgorod merchants that he will catch fish with golden feathers in Ilmen Lake. He wins the bet and becomes a rich merchant instead of a poor harpist.

This part of the epic has a fabulous-fantastic character, but Russian fairy tales did not know the motive of the wonderful gusler. V.F. Miller commented on this in such a way that, on the shores of Lake Ilmenya, we are standing on Finnish land, on which there were fairy tales about the sea king Ahti and the singer Veinemeinen.

In, and the merchant competes in wealth with Novgorod, builds ships, enrolls in the brotherhood of Nikolshchina, builds churches, chambers. Sadko boasts that he will buy all the goods in Novgorod (this has an epic scale). Sadko, however, is powerless before Novgorod as an epic whole. However, there is another ending, where Sadko manages to buy all the goods (this does not indicate the decline of Novgorod)

Do not redeem goods from all over the world;

I will also buy Moscow goods.

Overseas goods will arrive,

It’s not me, apparently, the Novgorod merchant is rich -

Glorious Novgorod is richer than me.

Then Sadko goes on a sea voyage, where trouble awaits him. The sea king demands a sacrifice. They cast lots - it falls out to Sadko. He is sent on a board to the sea and he falls asleep (motive: sleep as temporary death). Sadko takes the harp to the bottom. The choice turned out to be correct: the tsar calls Sadko to his place to listen to his game. Sadko plays a dance, the tsar has fun and a terrible storm rises on the sea. The shipbuilders pray to Nikola Mozhaisky for help, and the saint descends to the bottom of the sea. Invisible, he gives Sadko advice on how to proceed in the future. Sadko breaks the strings and the king, as a reward for the game, invites him to choose any bride. Sadko chooses Chernavushka. He seems to agree to the marriage, but does not touch his bride on their wedding night. Therefore, in the morning he wakes up on the banks of his native Volkhov River (Chernavushka was the personification of the banks of this river). Sadko did not succumb to underwater beauty and chose Novgorod. For help, he builds a church for Nikola Mozhatsky.

Mythologists say that the epic about Sadko is very ancient. And they compare the motive of Sadko's marriage to Chernavushka with the myth of the marriage union of the thunder god with a cloud nymph. Although there is some exaggeration in this, one cannot deny the magical ability of Sadko to influence the sea king with his music.

The fairy tale motif here is the motif of choosing a bride from many similar ones.

Other peoples have variants of this epic, for example, in Korea there is a legend about a young man who sailed on a ship and stopped for three days in the middle of the sea, he jumped into the abyss of the sea, and the ship sailed on. The young man rendered a service to the royal king and received his daughter as a reward. This motif came to Korea from India, from where it also got into Russian folklore (in some versions, Sadko is called an Indian guest)

A.N. Veselovsky draws a parallel with the French novel about Tristan from Leonoi, where the hero's name is Sadok. He kills his brother-in-law, as he encroached on the honor of his wife. He also sails on a ship, a storm rises (the punishment of the Lord for the sins of Zadok) and Zadok is thrown into the sea. The storm subsides, and Zadok repents of his sin and escapes to the island.

Sadko is a truly epic character who triumphs over merchants and the temptations of the underwater kingdom.

The most common stories about V. Buslaev

:

Vasily Buslaev in Novgorod (Vasily Buslaev with Novgorod men)

Vasily Buslaev's trip toJerusalem

Vasily Buslaev is endowed with incredible physical strength, but he does not know how to distribute it, he behaves defiantly

After all, Vaska Buslaevich got into the habit

From a drunkard, from a madman,

With young daring good fellows,

Drunk already began to get drunk.

And walking in the city disfigures:

Whom he will take by the hand

Take your hand out of your shoulder:

Whom will touch the leg,

That will break a leg out of the goose

In the epic about V. Buslaev with the Novgorodians they are looking for a reflection of specific historical realities (ritual battles, the beating of Novgorodians by Ivan the Terrible). In Soviet folkloristics, a tradition has developed to interpret V. Buslaev as a social rebel, a representative of the Novgorod freemen, challenging the rich, trading quarters and city authorities, but there are no sufficient grounds for this, since Vasily is the enemy of any social order. B.N. Putilov saw in this epic a parody of heroism, but it is unlikely that this is present here (a black-haired girl, brandishing a yoke like a club, is taken to pacify the fighting). A theme familiar to the epic: the revolt of the epic hero against any orders and restrictions.

This theme is also developed in another epic: "Vasily Buslaev went to pray." He goes to the holy land to save his soul. On the way, he meets outposts, but only one of them is fraught with a military clash: Vaska meets with robbers, Cossack chieftains. But they disperse peacefully, without a fight. This is not a heroic epic. She has more symbolic meaning(Christ was baptized in the Jordan River, and the stumbling block reminds us that death is not far off, but underfoot). All signs, reminders and signs have no price for him, for which he is punished by death. Vaska's rebelliousness is a legacy of the obstinacy of epic heroes.

And I do not believe, Vasenka, neither in a dream, nor in a choh,

And I believe in my scarlet elm!

Ticket number 9

historical songs. Historical background, heroes

DEFINITION OF HISTORICAL SONGS. THEIR ARTISTIC FEATURES

historical songs- these are folklore epic, lyrical-epic and lyrical songs, the content of which is dedicated to specific events and real persons of Russian history and expresses the national interests and ideals of the people. They arose about important events in the history of the people - those that made a deep impression on the participants and were preserved in the memory of subsequent generations. In the oral tradition, historical songs did not have a special designation and were simply called "songs" or, like epics, "old times". Not all researchers consider the historical song a genre. Propp: "genre presupposes the unity of poetic form, everyday use and performance." The historical song has no such unity. The volume, form of texts, aesthetic specificity differ significantly from each other.

Historical songs can be traced to specific events and situations, although they are based on fiction. Historical songs are not so much of an actual interest as of an ideological interest: in them, a judgment is being made on history. The subject of the historical song is modern history, and if it refers to the foreseeable past, it still gives an assessment from the standpoint of the present. Heroes historical songs - real people, a historical figure as such is interesting for a song. Narration based on real facts. The genre of the historical song was generated by the era of the formation of the centralized Russian state (the times of Ivan the Terrible => a cycle of songs about Ivan the Terrible: the capture of Kazan, a song about the wrath of Ivan the Terrible). AT song about Kostruk the traditional motifs of the heroic epic are frankly parodied. In all these 3 songs, the image of Ivan the Terrible is different from the image of epic rulers (Vladimir I), he has real qualities: suspicion, cruelty, anger, but justice, national honor and security. => a type of folklore "good" king is created. Song about Yermak => addition of a cycle of songs about Stepan Razin and robber songs. The songs steadily connect Yermak with the activities of Ivan the Terrible. B.N. Putilov said that the image of the song Yermak had significantly outgrown the scale of its historical prototype.

ATXVIIin. historical songs become lyrical and lyrical - the lyrical principle triumphs, the principles of depicting heroes become lyrical (Stepan Razin with falcon eyes, golden curls).

18th-19th centuries- songs-chronicles (military themes): a presentation of the course of military events.