Perhaps the greatest amount of information about the glorious past of the great Tartaria has come down to us thanks to such a bright personality as. Without a doubt, he was an outstanding man, one of the greatest rulers in world history. That is why so many medieval authors wrote about the period of his reign. And one of the most significant works, containing a great many amazing details about the socio-political and, as well as the customs and customs of its inhabitants, was left by the ambassador of the King of Castile, Ruy Gonzalez De Clavijo. But let's start in order.

. Christopher Del Altissimo. (1568)

. Christopher Del Altissimo. (1568) Quite a lot of information has been preserved about the identity of this person, and, as is usually the case when it comes to those whose deeds changed the course of history, the conjectures and fabrications contained in this information are much more than the truth. Take at least his name. In western Europe he is known as Tamerlane, in Russia he is called Timur. Reference literature usually contains both of these names:

“Tamerlane (Timur; April 9, 1336, the village of Khoja-Ilgar, modern Shakhrisabz, Uzbekistan - February 18, 1405, Otrar, modern Kazakhstan; Chagatai تیمور (Temür, Tēmōr) - “iron”) - a Central Asian conqueror who played a significant role in the history of Central, South and Western Asia, as well as the Caucasus, the Volga region and Russia. An outstanding commander, emir (since 1370). Founder of the Timurid Empire and Dynasty, with its capital in Samarkand. (Wikipedia)

However, from the Arabic-language sources left to us by the descendants of Tamerlane-Timur himself, it turns out that his real lifetime name and title sounded like Tamurbek-Khan Ruler of Turan, Turkestan, Khorassan and further on the list of lands that were part of Great Tartaria. Therefore, he was briefly called the Ruler of the Great Tartaria. The fact that today people with external features of the Mongoloid type live on these lands misleads not only the layman, but also orthodox historians.

Everyone is now convinced that Tamerlane looked like an average Uzbek. And the Uzbeks themselves have no doubt that Tamerlane is their distant ancestor and the founder of the nation. But this is not so either.

From the genealogy of the Great Khans, confirmed by chronicle sources, it is clear that the ancestor of the Uzbeks is another descendant of Genghis Khan, Uzbek Khan. And, of course, he is not the father of all living Uzbeks, who were so named according to the territorial principle.

Let's start from the end. Here is what is known from official sources about the death of the “Great Lame”: “As soon as the Egyptian sultan and John VII (later co-ruler of Manuel II Palaiologos) stopped resisting. Timur returned to Samarkand and immediately began to prepare for an expedition to China. He spoke at the end of December, but in Otrar on the Syrdarya River he fell ill and died on January 19, 1405 (other sources indicate a different date of death - 02/18/1405 - my comment.).

Tamerlane's body was embalmed and sent in an ebonite coffin to Samarkand, where he was buried in a magnificent mausoleum called Gur-Emir. Before his death, Timur divided his territories between his two surviving sons and grandsons. After many years of war and enmity over the left will, the descendants of Tamerlane were united by the younger son of the khan, Shahruk.

The first thing that raises doubts is the various dating of Tamerlane's death. When you try to find more reliable information, you inevitably stumble upon one single "true" source of all the myths about the "Uzbek" clone of Alexander the Great - the memoirs of Tamerlane himself, which he personally titled as follows: "Tamerlane, or Timur, the Great Emir." Sounds provocative, right? This contradicts the basic principles of the worldview inherent in the representatives of the Eastern civilization, which honors modesty as one of the highest virtues. Asian etiquette prescribes to praise your friends and even enemies in every possible way, but not yourself.

Immediately there is a suspicion that this "work" was titled by a person who has the most remote understanding of the culture, customs and traditions of the East. And the validity of this suspicion is confirmed as soon as you ask yourself the question of who became the publisher of Tamerlane's memoirs. This is one John Hern Sanders.

I believe that this fact is already enough to not take the "memoirs of the Great Emir" seriously. One gets the impression that everything in this world was created by British and French Freemasons, intelligence agents. This is no longer surprising, not even annoying. Egyptology was invented by Champillon, Sumerology by Layard, Tamerlanology by Sanders.

And if everything is very clear with the first two, then no one knows who Sanders is. There is fragmentary information that he was in the service of the King of Great Britain and regulated complex diplomatic issues in India and Persia. And so they refer to him as an authoritative specialist - "tamerlanologist".

Then it becomes clear that it is time to stop puzzling over the question of why suddenly the Uzbek leader unselfishly delivered the country of unfaithful Russian Christians, alien to him, from the yoke of the Golden Horde and crushed it (the horde) utterly.

Now is the time to remember the legendary opening of Tamerlane's tomb in June 1941. I will not go into a description of all the "mystical" signs and strange events, they are probably known to everyone. This is me about the prophecies on the tomb and in the old book, that if you disturb the ashes of Timur, then a terrible war will certainly break out. The tomb was opened on June 21, 1941, and on June 22, the next day, something happened that is known to every inhabitant of Russia and the republics of the former USSR.

Much more interesting is another "mystical" circumstance: the reasons that prompted Soviet scientists to open the tomb - that's where you need to start. On the one hand, everything is very clear, the goal was to study historical material. On the other hand, what if this was done to refute or, conversely, to confirm historical myths? I think that the main motive was just that - to prove to the whole world the greatness and antiquity of the great Uzbek people, which is part of the great Soviet people.

And this is where the magic begins. Something didn't go according to plan. First, clothes. The emir was dressed like a medieval Russian prince, the second - a light red beard and hair and fair skin. The famous anthropologist Gerasimov, a well-known specialist in the reconstruction of appearance from skulls, was amazed: Tamerlane did not at all resemble those of his rare images that have come down to us. The fact is that they can be called portraits with a very big stretch. They were written after the death of the "Iron Lame" by Persian masters who had never seen the conqueror.

So the later artists portrayed a typical representative of the Central Asian peoples, completely forgetting that Timur was not a Mongol. He was a descendant of a distant relative of Genghis Khan, who was from the kind of great Moghuls, or Mogulls, as Genghis Khan himself said. But the Moghuls have nothing to do with the Mongols, just as the province of Turana Katai has nothing to do with modern China.

Mogulls outwardly did not differ from the Slavs and Europeans. Everyone who has had time to live in the USSR knows that in every union republic, local artists painted portraits of Lenin, endowing him with the external features of their own people. So in Georgia, on large street posters, Lenin looked exactly like a Georgian, and in Kyrgyzstan, Lenin was portrayed, well, too “Mongolian”. So, it's all very clear. The history of the conclusion about the causes of death is not clear.

There are testimonies of contemporaries who claimed that Gerasimov repeatedly stated orally that his first reconstruction of the appearance of Tamerlane was not approved by the leadership, and he was "recommended" to bring the portrait to the generally accepted standard: Tamerlane is an Uzbek, a descendant of Genghis Khan. I had to make him a Mongoloid. Against a saber, a bare heel is a dubious argument.

Further, it is necessary to mention the undisguised facts of the study of the tomb. So, everyone knows that despite the advanced age of the deceased, he had excellent strong teeth, very strong smooth bones. That is, Timur was quite tall (172 cm), a strong, healthy man. The discovered injuries of the hand and patella could not play a fatal role. If so, then what was the cause of death? The answer may lie in the fact that someone for some reason separated Timur's head from the body. It is clear that the members of the expedition would not disassemble the body into "spare parts" without good reason.

The first probable reason for this barbarism, the desecration of the ashes, is the substitution of the head. Perhaps the original white head was replaced with a head of a representative of the Mongoloid race. The second version is that he was already decapitated in the coffin. Then the question arises about the possible murder of Timur. And now the time has come to recall the long-running "duck" about the causes of Timur's death.

I don’t even remember now the publication that published the “secret” confession of the pathologist who took part in the study of Tamerlane’s body. According to rumors, allegedly, Tamerlane was shot from a firearm! I would not like to replicate false sensations, but what if it's true? Then such secrecy of this “archaeological enterprise” becomes clear.

Tamerlane is a Mongol? In my opinion, a very European-looking man, with a rod symbolizing Rarog, who is also the Slavic god Khors. One of the incarnations of Ra is a sunny half-man half-falcon. Maybe the European artist did not know what "wild tartars" look like?

But we translate the inscription from Latin into Russian:

"Tamerlane, the ruler of Tartaria, the lord of the wrath of God and the forces of the Universe and the blessed country, was killed in 1402." The main word here is "killed". It follows from the inscription that the author treats Tamerlane with the utmost respect, and for sure, when creating the engraving, he relied on the well-known lifetime images of Tamerlane, and not on his own fantasies. However, the number of well-known portraits painted in the Middle Ages does not even leave any doubt that this is exactly what the “Lord of God’s Wrath…” looked like.

This is the reason for the emergence of many of all myths. Discarding later fantasies about Timur, looking at this evidence with a clear eye, we come to the following conclusions:

- Tamerlane is the Ruler of the Great Tartaria, of which Russia was also a part, therefore the symbolism of the "Mongol" is quite understandable to the Russian people.

- Power was given to him by a higher power.

- In 402 AD (I.402) he was killed. Perhaps they were shot.

- Tamerlane, judging by the symbolism (Magendavid with a crescent), belonged to the same diaspora as Sultan Bayazid, who commanded the horde of Anatolia and owned Constantinople. But let's not forget that the vast majority of the Russian aristocracy, including the mother of Peter I, had the same symbols on the family emblems.

But that's not all. Noteworthy is the sign on the cap of Tamerlane. If he is the Ruler, then the version that this is an ordinary ornament does not stand up to criticism. On the headdresses of monarchs there is always a symbol of the state religion.

Distinctive signs on headdresses are not the most ancient tradition, but firmly entrenched even before the accession to the throne of Tamerlane. And it became law after the introduction of the uniform, which first appeared in the world in medieval Russia.

And guardsmen wore black uniforms:

On the sleeve they had almost this sign embroidered:

Why did the boyars cry out so much at the introduction of the oprichnina? I believe that everything that we are told about the "National Guard" of Ivan the Terrible is an analogue of the modern indignation of human rights activists and dishonest officials. Hence the myths about the cruelty of the monarch.

Previously, soldiers, tax collectors and other sovereign people dressed in the service, whatever they had to. Fashion, as such, appeared only after the emergence of manufacturing, so the attempts of modern scientists to study the "ancient fashion", which are trying to identify differences in the national costumes of the Middle Ages, look quite funny. There were no "national" costumes. Our ancestors treated clothing in a completely different way than we do, and therefore dressed almost the same in Persipolis, and in Tobolsk, and in Moscow.

Any item of clothing was strictly individual, sewn for a specific person, and wearing someone else's was simply suicide. This meant taking on all the ailments and ailments of the real owner of the clothes. In addition, people understood that they could harm the owner of the dress that they would like to try on. The clothes of each person were considered part of the spirit of its owner, which is why it was considered an honor to receive a fur coat from the royal shoulder. Thus, the recipient, as it were, was attached to the highest, royal, and therefore, to the divine. And vice versa. Convicted that he was trying on royal clothes, they were considered as encroaching on the health and life of the monarch, and, accordingly, they were executed at the frontal place.

And to imitate the clothes of others was considered the height of stupidity. Each nobleman tried to stand out with his clothes from both commoners and fellow classmates, so how many people existed, there were so many costumes. Of course, there were general trends, it is natural just like the fact that all cars have round wheels.

That is why I consider the surprised remarks of medieval travelers about the similarity of European and Russian costumes to be absurd. We live in approximately the same climatic conditions, we have approximately the same level of technology, it is absolutely normal that all people of the white race dressed in the same way. Except for the details, of course. Even on everyday clothes of peasants there were individual signs in the form of embroideries. Interestingly, the main thing in clothing was a belt. It had an individual ornament, and only the owner could touch it.

The belt was tied at the place where the chakra is located, called in Russia "hara" (hence the origin of the concept of "character"), which is responsible for a person's life. That is why, they used to say “Not sparing their belly”, which was synonymous with the expression “not sparing their lives”.

So maybe Tamerlane's headdress is just an ornament? It signified his own unique personality, and therefore was unique, and there was no point in looking for similar images? May be. Or maybe not. Here is an engraving from the book of Adam Olearius with views of Russia:

I don't know if you can even call it crosses? This does not fit in with the objects that we see on the modern domes of modern places of worship. Although in Western Ukraine there are still churches with such crosses. But the analogy with the "cockade" of Tamerlane is too obvious to be a mere coincidence.

It remains only to figure out what all this can mean.

By and large, there is absolutely nothing to be surprised at. The tradition of decorating royal headdresses with crosses is not new.

However, it may well be that the very meaning of this is not completely clear to us. Yes, we found out that Tamerlane was depicted with a symbol of royal power - a cross, and the shape of the cross on his hat corresponds to the era in which the crosses on the temples were of this form, but questions remain. Were they Christian crosses? Did they have any connection with religion at all? And why did such hats come to replace those that were used earlier?

A huge help in the reconstruction of genuine historical events are the most nondescript, at first glance, documents. From a cookbook, for example, you can learn more information than from a dozen scientific papers written by the most eminent historians. Cookbooks did not come to mind to destroy or forge. The same is true of various travel notes that have not become widely known. In our digital age, publications have come into open access that were not even considered as historical sources, but they often contain sensational information.

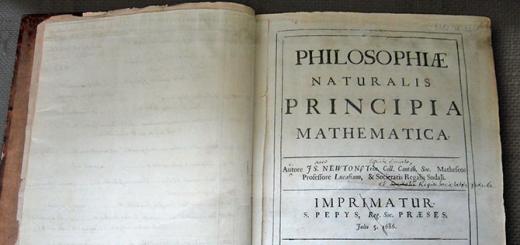

One of these, of course, is the report of Ruy Gonzalez De Clavijo, Ambassador of the King of Castile, about his journey to the court of the Ruler of the Great Tartary Tamerlane in Samarkand. 1403-1406 from the incarnation of God the Word.

A very curious report, which can be considered documentary, despite the fact that it was translated into Russian and published for the first time already at the end of the nineteenth century. Based on the well-known facts, about which today we already know with a high degree of certainty, in what exactly they were distorted, one can draw up a very realistic picture of the era in which the legendary Timur ruled Tartaria.

The original version of the reconstruction of Tamerlane's appearance based on his remains, produced by Academician M.M. Gerasimov in 1941, but who was rejected by the leadership of the USSR Academy of Sciences, after which the appearance of Timur was given typical facial features characteristic of modern Uzbeks.

The original version of the reconstruction of Tamerlane's appearance based on his remains, produced by Academician M.M. Gerasimov in 1941, but who was rejected by the leadership of the USSR Academy of Sciences, after which the appearance of Timur was given typical facial features characteristic of modern Uzbeks. The report contains a lot of truly amazing information that characterizes the features of the history of the medieval Mediterranean and Asia Minor. When I began to study this work, the first thing that surprised me was that the official document, in which all dates, geographical names, the names of not only nobles and priests, but even ship captains, are scrupulously recorded, is set out in a lively, vivid literary language. Therefore, the document is perceived as an adventurous novel in the spirit of R. Stevenson or J. Verne.

From the first pages, the reader plunges into the outlandish world of the Middle Ages with his head, and it is incredibly difficult to tear himself away from reading, while, unlike Treasure Island, de Clavijo's Diary leaves no doubt about the authenticity of the events described. In great detail, with all the details and reference to dates, he describes his journey in such a way that a person who knows the geography of Eurasia well enough can trace the entire route of the embassy from Seville to Samarkand and back, without resorting to reconciliation with geographical maps.

First, the royal ambassador describes a carrack journey through the Mediterranean. And unlike the officially accepted version of the properties of this type of ship, it becomes clear that Spanish historians greatly exaggerated the achievements of their ancestors in shipbuilding and navigation. It is clear from the descriptions that the carrack is no different from Russian plows or boats. Carrack was not adapted for traveling on the seas and oceans, it is exclusively a coaster capable of moving within sight of the coastline only if there is a fair wind, making “throws” from island to island.

The description of these islands attracts attention. Many of them at the beginning of the century had the remains of ancient buildings and at the same time were uninhabited. The names of the islands are basically the same as modern ones, until travelers find themselves off the coast of Turkey. Further, all toponyms have to be restored in order to understand what city or island we are talking about.

And here we come across the first great discovery. It turns out that the existence of which is not considered unconditional by historians to this day, at the beginning of the fifteenth century did not raise any questions. To this day we are looking for the “legendary” Troy, and De Clavijo describes it simply and casually. She is as real to him as his native Seville.

Here is the place today:

By the way, not much has changed now. Between Tenio (now Bozcaada) and Ilion (Geyikli) there is a continuous ferry service. It is probable that even earlier large ships moored to the island, and between the port and Troy there was communication only by boats and small ships. The island was a natural fort that protected the city from the sea from the attack of the enemy fleet.

A natural question arises: where did the ruins go? There is only one answer: they were dismantled for building materials. Common practice for builders. The Ambassador himself mentions in the Diary that Constantinople is being built at a rapid pace, and ships with marble and granite flock to the moorings from many islands. Therefore, it is completely logical to assume that instead of cutting the material in a quarry, it was much easier to take it ready-made, especially since hundreds and thousands of finished products in the form of columns, blocks, and slabs disappear in vain in the open air.

So Schliemann “discovered” his Troy in the wrong place, and tourists in Turkey are taken to the wrong place. Well... Absolutely the same thing is happening here with the site of the Kulikovo battle. All scientists have already agreed that the Kulikovo field is a district of Moscow called Kulishki. There is the Donskoy Monastery, and Krasnaya Gorka, an oak forest in which the ambush regiment hid, but tourists are still taken to the Tula region, and in all textbooks no one is in a hurry to correct the mistake of historians of the 19th century.

The second question that needs to be resolved is how did the seaside Troy end up so far from the surf line? I suggest adding some water to the Mediterranean. Why? Yes, because its level is constantly falling. According to the frozen lines on the coastal land areas, it is clearly visible at what mark the sea level was in what period of time. Since the De Clavijo embassy, the sea level has dropped several meters. And if the Trojan War actually took place millennia ago, then you can safely add 25 meters, and this is the picture you get:

The hit is complete! Geyikli is ideally becoming a seaside town! And the mountains behind, exactly as described in the Diary, and a vast bay, like Homer's.

Agree, it is very easy to imagine the walls of the city on this hill. And the ditch in front of him was filled with water. It seems that you can no longer look for Troy. One thing is a pity: no traces have been preserved, because Turkish peasants have been plowing the land there for centuries, and even an arrowhead cannot be found in it.

Until the nineteenth century, there were no states in the modern sense. Relations were of a pronounced criminal nature on the basis of the principle "I cover you - you pay." Moreover, citizenship therefore has the root “tribute”, which is not related to origin or location. The mass of castles in Turkey belonged to Armenians, Greeks, Genoese and Venetians. But they paid tribute to Tamerlane, as did the court of the Turkish Sultan. Now it is clear why Tamerlane called the largest peninsula in the Sea of Marmara from Asia, "Turan". This is colonization. The large country of Turan, which stretched from the Bering Strait to the Urals, owned by Tamerlane, gave its name to the newly conquered land in Anatolia opposite the Marble Island, where there were quarries.

Further, the embassy passed Sinop, which at that time was called Sinopol. And they arrived in Trebizond, which is now called Trobzon. There they were met by Chakatai, the messenger of Tamurbek. De Clavijo explains that in fact “Tamerlane” is a contemptuous nickname meaning “crippled, lame-legged”, and the real name of the Tsar, by which his subjects called him, was TAMUR (iron) BEK (Tsar) - Tamurbek.

And all the warriors from the native tribe of Tamurbek-Khan were called chakatay. He himself was a chakotay and brought his fellow tribesmen to the Samarkand kingdom from the north. More precisely, from the coast of the Caspian Sea, where Chakatai and Arbals live to this day, tribesmen of Tamerlane, fair-haired, white-skinned and blue-eyed. True, they themselves do not remember that they are descendants of the Moguls. They are sure that they are Russians. There are no external differences.

But, by the way, after Tamurbek defeated Bayazet and conquered Turkey, the peoples of Kurdistan and southern Armenia breathed more freely, because in exchange for an acceptable tribute, they received freedom and the right to exist. If history develops in a spiral, then perhaps the Kurds again have hope for liberation from the Turkish yoke with the help of their neighbors from the east.

The next discovery for me was the description of the city of Bayazet. It would seem that more new things can be learned about this city of military Russian glory, but no. See:

At first I could not understand what it was about, but only after I converted the leagues into kilometers (6 leagues - 39 kilometers), I was finally convinced that Bayazet was called "Kalmarin" in the time of Tamurbek.

And here is the castle, which was visited during the embassy of Ruy Gonzalez De Clavijo. Today it is called Ishak Pash Palace.

The local knight tried to force the ambassadors to pay tribute, saying that the castle exists only at the expense of the taxes of passing merchants, to which the chakatay noted that they were guests himself ... The conflict was settled.

By the way, De Clavijo calls knights not only the owners of castles, but also Chakatays - officers of Tamurbek's army.

During the journey, the ambassadors visited many castles, and from their description it becomes clear their purpose and meaning. It is generally accepted that these are exclusively fortifications. In fact, their military importance is greatly exaggerated. First of all, this is a house that can withstand the efforts of any "safecracker". Therefore, "castle" and "castle" are the same root words. The castle is a storehouse of valuables, a reliable safe and a fortress for the owner. A very expensive pleasure, available to very wealthy people who had something to protect from robbers. Its main purpose is to hold out until the arrival of reinforcements, the squad of the one to whom tribute is paid.

A very curious fact: even at the time of the described embassy, wild wheat grew in abundance at the foot of Ararat, which, according to De Clavijo, was completely unsuitable, because it had no grains in the ears. Like it or not, this fact indicates that Noah's Ark, as a repository of DNA samples, could well exist in reality and contributed to the revival of life from Ararat.

And from Bayazet, the expedition went to Azerbaijan and to the north of Persia, where they were met by the messenger of Tamurbek, who ordered them to go south to meet with the royal mission. And travelers were forced to get acquainted with the sights of Syria. On the way, sometimes amazing events happened to them. What, for example, is this:

Did you understand? A hundred years before the discovery of America in Azerbaijan and Persia, people calmly ate corn, and did not even suspect that it had not yet been “discovered”. As they did not suspect that it was the Chinese who first invented silk and began to grow rice. The fact is that, according to the ambassadors, rice and barley were the main food products, both in Turkey and in Persia and Central Asia.

I immediately remembered that when I lived in a small seaside village not far from Baku, I was surprised that in every house of local residents one room was allocated for growing silkworms. Yes! In the same place, mulberry, or "here" as the Azerbaijanis call it, grows at every step! And the boys had such a duty around the house, every day to climb a tree, and tear the leaves for the silkworm caterpillars.

And what? Half an hour a day is not difficult. At the same time, eat plenty of berries. Then the leaves crumbled into newspapers, over the mesh of the armored bed, and hundreds of thousands of voracious green worms begin to actively chew this mass. Caterpillars are growing by leaps and bounds. A week or two, and silkworm pupae are ready. Then they were handed over to the sericulture state farm, and on this they had a significant extra income. Nothing changes. Azerbaijan was the world center for the production of silk fabrics, not Chin. Probably, until the very moment the oil fields were opened.

In parallel with the description of the journey to Shiraz, De Clavijo tells in detail the story of Tamurbek himself, and tells about all his exploits in a picturesque form. Some of the details are amazing. For example, I recalled an anecdote about how a boy in a Jewish family asks: “Grandfather, was it true that during the war there was nothing to eat”?

True granddaughter. There wasn't even a loaf. I had to spread butter directly on the sausage.

Ryuy writes about the same: “In times of famine, the inhabitants were forced to eat only meat and sour milk.” I'm so hungry!

Indeed, the description of the food of ordinary Tartar subjects is breathtaking. Rice, barley, corn, melons, grapes, flat cakes, mare's milk with sugar, sour milk (kefir, yogurt, cottage cheese, and cheese, as I understand it), wine, and just mountains of meat. Horse meat and lamb in huge quantities, in a variety of dishes. Boiled, fried, steamed, salted, dried. In general, the Castilian ambassadors, for the first time in their lives, ate like a human being during a business trip.

But then the travelers arrived in Shiraz, where a few days later they were joined by the mission of Tamurbek to accompany them to Samarkand. Here for the first time I had difficulties with identification with the geography of the campaign. Suppose Sultania and Orasania are parts of modern Iran and Syria. What then did he mean by "Little India"? And why is Hormuz a city if it is now an island?

Let us suppose that Hormuz broke away from the land. But what about India? According to all descriptions, India itself falls under this concept. Its capital is Delies. Tamurbek conquered it in a very original way: against the war elephants, he released a herd of camels with burning bales of straw on their backs, and the elephants, terribly afraid of fire by nature, trampled the Indian army in a panic, and ours won. But if so, what then is "Greater India"? Maybe the modern researcher I. Gusev is right, who claims that Greater India is America? Moreover, the presence of corn in this region makes us think about it again.

Then questions about the presence of traces of cocaine in the tissues of Egyptian mummies disappear by themselves. They did not fly on vimanas across the ocean. Cocaine was one of the spices, along with cinnamon and pepper, that merchants brought from Little India. Of course? will sadden fans of the work of Erich von Däniken, but what can you do if in fact everything is much simpler and without the participation of aliens.

OK. Let's go further. In parallel with the most detailed description of the route from Shiraz to Orasania, which bordered the Samarkand kingdom along the Amu Darya, De Clavijo continues to pay much attention to the description of the deeds of Tamurbek, which the envoys told him about. There is something to be horrified here. Perhaps this is part of the information war against Tamerlane, but hardly. Everything is described in too much detail.

For example, Timur's zeal for justice is striking. He himself, being a pagan, never touched either Christians or Muslims or Jews. For the time being. Until the Christians showed their lying greedy face.

During the war with Turkey, the Greeks from the European part of Constantinople promised help and support to Tamurbek's army in exchange for a loyal attitude towards them in the future. But instead, they supplied Bayazit's army with a fleet. Tamurbek Bayazit defeated simply brilliantly, in the best traditions of the Russian army, with low losses, defeating many times superior forces. And then he drove the captive Sultan together with his son in a golden cage mounted on a cart, like an animal in a zoo.

But he did not forgive the vile Greeks, and since then he has persecuted Christians mercilessly. Just as he did not forgive the tribe of White Tartars, who also betrayed him. In one of the castles, they were surrounded by Tamurbek's squad, and they, seeing that they could not get away from retribution, tried to pay off. Then the wise, just, but vindictive king, in order to save the lives of his soldiers, promised the traitors that if they themselves brought him money, he would not shed their blood. They left the castle.

Well? I promised you that I would not shed your blood?

- Promised! - White tartars began to sing in unison.

- And I, unlike you, keep my word. Your blood will not be shed. Bury them alive! - he ordered his "Commander-in-Chief of the Tartar Guards."

And then a decree was issued that every subject of Tamurbek was obliged to kill all the white tartars he met on the way. And if he does not kill, he will be killed himself. And the repressions of the Timurov reform began. Within a few years, this people was completely exterminated. Only about six hundred thousand.

Rui recalls how on the way they met four towers "so high that a stone cannot be dropped." Two were still standing, and two collapsed. They were built from the skulls of White Tartars, held together as mortar with mud. Such were the manners in the fifteenth century.

Another curious fact describes De Clavijo. This is what I described in detail in the previous chapter - the presence of a logistics service in Tartaria. Tamerlane significantly reformed it, and some details of this reform can serve as a clue to another mystery, what kind of mythical Mongols, together with the Tatars, “have been torturing unfortunate Russia for three hundred years”:

Thus, we are again convinced that "Tatar-Mongolia", in fact, is not Tataria at all and not Mongolia at all. - Yes. Mogulia - yes! Just an analogue of the modern Russian Post.

Next, we will talk about the "Iron Gates". This is where the author most likely got confused. He confuses Derbent with the "Iron Gates" on the way from Bukhara to Samarkand. But not the point. Using the example of this passage, I highlighted the key words in the text in Russian with markers of various colors, and I highlighted the same words in the original text. This clearly shows what sophistication historians went to to hide the truth about Tartaria:

It is possible that I am mistaken in the same way as the translator who translated the book from Spanish. And "Derbent" has nothing to do with it, but "Darbante" is something, the meaning of which has been lost, because there is no such word in the Spanish dictionary. And here are the original "Iron Gates", which, along with the Amu Darya, served as a natural defense of Samarkand from a sudden invasion from the west:

And now about the chakatas. My first thought was that this tribe could somehow be connected with Katai, who was in Siberian Tartaria. Moreover, it is known that Tamurbek paid tribute to Katai for quite a long time, until he took possession of it with the help of diplomacy.

But later another thought came. It is possible that the author simply did not know how to spell the name of the tribe, and wrote it down by ear. But in fact, not “chakatai”, but “chegodai”. After all, this is one of the Slavic pagan nicknames, such as chelubey, nogai, mother, run away, catch up, guess, etc. And Chegodai is, in other words, "The Beggar" (give me something?). Indirect confirmation that such a version has the right to life is the following find:

"Chegodaev is a Russian surname, derived from the male name Chegodai (in the Russian pronunciation Chaadai). The surname is based on a proper male name of Mongolian origin, but widely known among the Turkic peoples. It is also known as the historical name of Chagatai (Jagatai), the second son of Chingiz -Khana, meaning brave, honest, sincere. The same name is known as an ethnonym - the name of the Turkic-Mongolian tribe Jagatai-Chagatai, from which Tamerlane came. The surname sometimes changed into Chaadaev and Cheodaev. The surname Chegodaev is of the Russian princely family.

In general, the statement that Tamerlane is the founder of the Timurid dynasty is not true, because he himself was a representative of Genghisides, which means that all his descendants are also Genghisides.

It was interesting to understand the origin of the toponym "Samarkand". In my opinion, too many city names contain the root "samar". This is the biblical Samaria, and our metropolis on the Volga Samara, and before the revolution, Khanty-Mansiysk was called Samarov, and Samarkand itself, of course. We have forgotten the meaning of the word "Samar". But the ending "kand" fits perfectly into the system of formation of toponyms in Tartaria. These are Astrakh (k) an, and Tmu-cockroach, and many different "kans" and "vats" (Srednekan, Kadykchan) in the north-east of the country.

Perhaps all these endings are associated with the word "ham" or "khan". And we could have inherited from the Great Tartaria. Surely, in the east, the cities were called by the name of their founders. As Prince Sloven founded Slovensk, and Prince Rus - Russu (now Staraya Russa), so Belichan could be the city of Bilyk Khan, and Kadykchan - Sadyk Khan.

And further. Do not forget about how the Magi actually named the pagan Ivan the Terrible at birth:

"Ivan IV Vasilyevich, nicknamed the Terrible, by the direct name of Titus and Smaragd, in the tonsure of Ion (August 25, 1530, the village of Kolomenskoye near Moscow - March 18 (28), 1584, Moscow) - sovereign, Grand Duke of Moscow and All Russia from 1533, the first tsar of all Russia.

Yes. Smaragd is his name. Almost SAMARA-gd. And this may not be just a coincidence. Why? Yes, because when describing Samarkand, the word "emerald" is repeated dozens of times. There were huge emeralds (emeralds) on the cap of Tamurbek and on the diadem of his elder wife. Clothes and even numerous palaces of Tamurbek and his relatives were decorated with emeralds. Therefore, I would venture to suggest that "samara" and "smara" are one and the same. Then it turns out that the person in the title picture is the wizard of the Emerald City?

But this is a digression. Let's return to medieval Samarkand.

The description of the brilliance of this city is dizzying. For Europeans, it was a miracle of miracles. They did not even suspect that what they previously considered luxury is considered “jewelry” even among the poor in Samarkand.

Let me remind you that we were all told from childhood that the magnificent Tsaregrad was the pinnacle of civilization. But what a hitch... The author devoted several pages to the description of this Constantinople, of which only the church of John the Baptist is remembered. And in order to express the shock of what he saw in the "wild steppes", he needed fifty pages. Weird? It is obvious that historians are not telling us something.

There was absolutely everything in Samarkand. Powerful fortresses, castles, temples, canals, pools in the courtyards of houses, thousands of fountains, and much, much more.

Travelers were struck by the wealth of the city. The description of feasts and holidays merges into one continuous series of grandeur and splendor. So much wine and meat in one place in such a short period of time, the Castilians have not seen in their entire previous life. The description of the rituals, traditions and customs of the Tartars is noteworthy. One of them, at least, has come down to us in full. Drink until you drop. And mountains of meat and tons of wine from the palaces were taken out to the streets to distribute to ordinary citizens. And the Feast in the palace has always become a nationwide celebration.

Separately, I would like to say about the fight against corruption in the kingdom of Tamurbek. De Clavijo tells about one case when, during the absence of the Sovereign in the capital, an official who remained I.O. King, abused power and offended someone. As a result, I tried on a “hemp tie”. More precisely, paper, because in Samarkand everyone wore a natural cotton dress. Probably the ropes were also made of cotton.

Another official was also hanged, who was convicted of wasting horses from the giant herd of Tamurbek. Moreover, capital punishment was always accompanied by confiscation in favor of the state treasury under Timur.

People not of boyar origin were executed by beheading. It was worse than just death. By separating the head from the body, the executioner deprived the convict of something more important than just life. De Clavijo witnessed the trial and chopping off of the heads of a shoemaker and a merchant, who unreasonably raised the price during the absence of the Tsar in the city. That's what I understand, an effective fight against monopolies!

And here's another little discovery. For those who think that the Amazons were invented by Homer. Here it is, in black and white:

Witch? No, Queen! And that was the name of one of the eight wives of Timur. The youngest, and probably the most beautiful. That's how he was ... The Wizard of the Emerald City.

Modern archeological finds confirm that Samarkand was actually an emerald city during the time of Tamerlane. Today, these masterpieces are called so: “The Emeralds of the Great Moghuls. India".

The description of the ambassadors' way back through Georgia is interesting, of course, but only from the point of view of a novelist. Too many dangers and severe trials have fallen to the lot of travelers. I was especially struck by the description of how they ended up in snow captivity in the mountains of Georgia. Interestingly, today it happens that snow falls for several days and sweeps houses on the roof?

Pisconi is perhaps a profession, not a surname.

The exploits of Tamerlane, and not quite exploits

The story about the exploits of Tamurbek Khan would be incomplete if we did not turn to other sources that tell about the epochal events that occurred during his reign. One such source is a document known as Ivan Schiltberger's Travels in Europe, Asia and Africa from 1394 to 1427. I will omit descriptions of Europe and Africa, since within the framework of this topic, my goal was initially only to describe the past of our country in its most ancient period, when it was called Scythia, and then Tartaria.

Why does it make sense to dwell on this issue in more detail. The fact is that this is also our history. An attempt by historians to separate the history of Russia from the history of the Great Tartary has led to what we have today. And we have a huge number of fellow citizens who question even the very existence of such a country in the past, not to mention the fact that Russia was an integral part of it.

This is the strategy aimed at crushing a great country. Having broken it into pieces in the past, it is very easy to break it into pieces in the present. Therefore, it is vital for every inhabitant of all countries that were until recently a single state - the Soviet Union, to know their history in order not to repeat mistakes in the future.

Today you cannot find a person who would not know the name of Tamerlane. But try to ask a casual passer-by about what the great politician and commander became famous for, and in about ninety percent of cases, you will not hear anything beyond what was told in the commercial of one commercial bank. People will say that, they say, there was such a ferocious Mongol who only did what he conquered everyone, and at the same time did not spare either his own or others.

This is partly true. Timur was stern and merciless. But he was fair. He took care of his people, defended the peoples who submitted to him, and at the same time was not bloodthirsty. There was a time when the death penalty was the most effective tool of government. But Timur ruled not for the sake of his own ambitions, but for the benefit of the people, who considered him their father and protector. He even took the title of Khan shortly before his death.

Therefore, it is not enough to know that Tamerlane existed. You need to know exactly what he did and how. We must be fully aware that along with Ogus Khan, Genghis Khan, Batu Khan, Prophetic Oleg and Tsar Smaragd (Ivan the Terrible), Tamurbek Khan, we owe the existence of our modern country - Russia. So, let's turn to the facts presented by Ivan Shiltberger, which largely confirm and supplement the information provided by Abulgazi-Bayadur-Khan.

About the war of Tamerlane with the king-sultan

Upon his return from a happy campaign against Bayazit, Tamerlane began a war with the Sultan King, who occupies the first place among the pagan rulers. With an army of one million two hundred thousand people, he invaded the possessions of the Sultan and began the siege of the city of Galeb, in which there were up to four hundred thousand houses. It's hard to believe, but from somewhere Schiltberger took such figures.

The commander of the besieged garrison made a sortie with eighty thousand people, but was forced to return and lost many soldiers. Four days later, Tamerlane took possession of the suburb and ordered that its inhabitants be thrown into the city ditch, and logs and dung were thrown on them so that this ditch was filled up in four places, although it had twelve fathoms of depth. If this is true, and Tamerlane actually did this to innocent civilians, then undoubtedly he is one of the greatest villains of all times and peoples. However, one should not forget that the information war was not invented today or yesterday.

Fables are written about all the great rulers of Tartaria to this day, and this is normal. The more merit the ruler has, the more myths about his bloodthirstiness are added up. So the tales of the cruelty of Ivan the Terrible have long been exposed, but no one is still in a hurry to rewrite textbooks. The same, I think, is the case with the myths about Tamerlane.

Then Tamerlane proceeded to another city, called Urum-Kola, which offered no resistance, and to the inhabitants of which Tamerlane showed mercy. From there he went to the city of Aintab, the garrison of which refused to submit to the sovereign, and the city was taken after a nine-day siege. According to the customs of the war of those times, the unsubdued city was given to soldiers for plunder. After that, the army moved to the city of Begesna, which fell after a fifteen-day siege, and where the garrison was left.

The mentioned cities were considered the main ones in Syria after Damascus, where Tamerlane then went. Upon learning of this, the Sultan King ordered to ask him to spare this city, or at least the temple located in it, to which Tamerlane agreed. The temple in question was so large that it had forty gates on the outside. Inside, it was lit by twelve thousand lamps, which were lit on Fridays. On other days of the week, only nine thousand were lit. Among the lamps there were many gold and silver consecrated by king-sultans and nobles.

Tamerlane besieged Damascus, and the Sultan sent from his capital Cairo, where he was, an army of twelve thousand people. Tamerlane, of course, defeated this detachment and sent in pursuit of enemy soldiers who had fled from the battlefield. But after each overnight stay, they poisoned the water and the area before leaving, so because of the heavy losses, the chase had to be returned back. This seems to be one of the oldest descriptions of the use of chemical weapons.

After a few months of siege, Damascus fell. One of the cunning qadi fell on his face before the conqueror and asked to negotiate a pardon for himself and other nobles. Tamerlane pretended to believe the priest and allowed all those who, in the opinion of the Qadi, were better than other civilians, to take refuge in the temple. When they took refuge in the temple, Tamerlane ordered to lock the gates from the outside and burn the traitors of his people. Such is the natural selection. Cruel? - Yes! Fair? Again - Yes!

He also ordered his soldiers to each present him on the head of an enemy soldier and after three days, used to carry out this order, he ordered to erect three towers from these heads.

Then he went to another region, called Shurki, which did not have a military garrison. The inhabitants of the city, famous for its spices and spices, supplied the army with everything necessary, and Tamerlane, leaving garrisons in the conquered cities, returned to his lands.

Conquest of Babylon by Tamerlane

Upon returning from the possessions of the king-sultan, Tamerlane with a million troops set out against Babylon.

By the way, if you think that the ancient city of Babylon is mythical, then you are deeply mistaken. Saddam Hussein's palace is on the edge of this city.

Upon learning of his approach, the king left the city, leaving a garrison in it. After a siege that lasted a whole month, Tamerlane, who ordered to dig mines under the wall, took possession of it and set it on fire. He ordered barley to be sown on the ashes, for he swore that he would destroy the city completely, so that in the future no one could even find the place on which Babylon stood. However, the citadel of Babylon, located on a high hill and surrounded by a moat filled with water, remained impregnable. It also contained the treasury of the Sultan. Then Tamerlane ordered to divert water from the ditch, in which three lead chests were found, filled with gold and silver, each two fathoms in length and one fathom in width.

The kings hoped to save their treasures in this way if the city was taken. Commanding them to carry away these chests, Tamerlane also took possession of the castle, where there were no more than fifteen people who were hanged. However, four chests filled with gold were also found in the castle, which were taken away by Tamerlane. Then, having mastered three more cities, he, on the occasion of the onset of a sultry summer, had to retire from this region.

The conquest of India Minor by Tamerlane

Upon returning to Samarkand, Tamerlane ordered all his subjects to be ready for a trip to Little India, a four-month journey from his capital, after four months. Having set out on a campaign with a 400,000-strong army, he had to pass through a waterless desert, which took twenty days to cross. From there he arrived in a mountainous country, through which he made his way only in eight days with great difficulty, where he often had to tie camels and horses to boards in order to lower them from the mountains.

Further, Schiltberger describes the mysterious valley, "which was so dark that the warriors at noon could not see each other." As to what it was, one can now only guess. However, most likely the matter is not in the valley itself, but in some natural phenomenon, which coincided in time with the arrival of Tamerlane's troops in this area. Perhaps the reason for the long eclipse was a cloud of volcanic ash, or perhaps some more formidable natural phenomenon.

Then the army arrived in the mountainous country of a three-day stretch, and from there it got to the plain, where the capital of India Minor was located. Having set up his camp in this plain at the foot of a forest-covered mountain, Tamerlane ordered the messenger to tell the Ruler of the Indian capital: "Peace, Timur geldi", that is, "Surrender, sovereign Tamerlane has come."

The ruler preferred to oppose Tamerlane with four hundred thousand warriors and forty elephants trained for battle, carrying a tower with ten archers inside on his back. Tamerlane came out to meet him and would willingly start a battle, but the horses did not want to go forward, because they were afraid of the elephants placed in front of the formation. Tamerlane retreated and arranged a military council. Then one of his generals named Soliman Shah (a salty man, probably Suleiman, aka Solomon) advised to collect the required number of camels, load them with firewood, set them on fire and send them to the Indian war elephants.

Tamerlane, following this advice, ordered twenty thousand camels to be prepared and firewood laid on them. When they appeared to the sight of the enemy formation with elephants, the latter, frightened by fire and the cries of camels, fled and were partially killed by Tamerlane's soldiers, and partially captured as trophies.

Tamerlane besieged the city for ten days. Then the king began negotiations with him and promised to pay two hundredweights of Indian gold, which is better than Arabian. In addition, he gave him many more diamonds and promised to send thirty thousand auxiliary troops at his request. Upon the conclusion of peace on these terms, the king remained in his state, and Tamerlane returned home with a hundred war elephants and riches received from the king of India Minor.

How the governor steals great treasures from Tamerlane

Upon returning from the campaign, Tamerlane sent one of his nobles named Shebak with a corps of ten thousand to the city of Sultania to bring the five-year taxes stored there, collected in Persia and Armenia. Shebak, upon accepting this indemnity, imposed it on a thousand carts and wrote about this to his friend, the ruler of Mazanderan, who was not slow to come with a fifty-thousandth army, and together with his friend and with money returned to Mazanderan. Learning about this, Tamerlane sent a large army in pursuit of them, which, however, could not take Mazanderan because of the dense forests with which it is covered. Here we are once again convinced that the eastern part of the Caspian lowland was once covered with lush vegetation. Looking at these places today, it is hard to believe, but after all, several medieval authors could not be so cruelly mistaken at once.

Then Tamerlane sent another seventy thousand people with orders to make their way through the forests. Indeed, they cut down the forest for a mile, but they did not gain anything by this, so they were recalled by the sovereign back to Samarkand. For some reason, Schiltberger is silent about the further fate of the stolen treasures. It is hard to believe that embezzlement on such a scale could go unpunished. And most likely, the author simply did not know the end of this incident.

How Tamerlane ordered to kill 7,000 children.

Then Tamerlane bloodlessly annexed the kingdom of Ispahan with the capital of the same name to his state. He treated the people kindly and kindly. He left Ispahan, taking with him his king, Shahinshah, leaving a garrison of six thousand people in the city. But soon after the departure of Tamerlane's army, the inhabitants attacked his soldiers and killed everyone. Tamerlane had to return to Ispakhan and offer the inhabitants peace on the condition that they sent him twelve thousand archers. When these soldiers were sent to him, he ordered each of them to cut off the thumb on the hand and in this form sent them back to the city, which was soon taken by him by attack.

Gathering the inhabitants in the central square, he ordered to kill all those over the age of fourteen, thus sparing those who were younger. The heads of the dead were stacked in towers in the center of the city. Then he ordered the women and children to be taken to a field outside the city and children under seven years old to be placed separately. Then he ordered the cavalry to trample them with the hooves of horses. It is said that Tamerlane's own associates begged him on their knees not to do this. But he stood his ground and re-issued the order, which, however, none of the soldiers could dare to carry out. Angry, Tamerlane himself ran into the children and said that he would like to know who would dare not follow him. The warriors then were forced to imitate his example and trample the children with the hooves of their horses. There were about seven thousand of them in total.

Of course, this could be true, but in order to demonize a person, there is still no more effective method than accusing him of killing innocent children. The most famous of these legends entered the Bible as a chilling tale of the slaughter of infants by King Herod. However, now we already understand where the “ears grow” from this legend. Herod did not give the order to destroy all babies. He sent his archers in search of only one boy who, having become of age, could claim his throne, since he was his natural son from Mary, the wife of Herod, who was in exile before it turned out that she was pregnant by the monarch.

Tamerlane proposes to fight with the Great Ham

At about the same time, the ruler of Cathay sent envoys to the court of Tamerlane with a demand to pay tribute for five years. Tamerlane sent the envoy back to Karakurum with the answer that he considered the khan not the supreme ruler, but his tributary, and that he would personally visit him. Then he ordered to notify all his subjects so that they would prepare for a campaign in Turan, where he went with an army consisting of eight hundred thousand people. After a month's journey, he arrived at a desert that stretched for seventy days' journey, but after a ten-day journey, he had to return, having lost many soldiers and animals due to lack of water and the extremely cold climate of this country. Probably, Tamerlane planned to enter Katai through modern Tuva and Khakassia by the western route, along the Genghis Khan Road. But in the northern steppes of modern Kazakhstan, the campaign had to be interrupted and stopped in Otrar, where Tamerlane was killed by the conspirators, who, no doubt, were bribed by the people of the Great Ham.

On the death of Tamerlane

This part of the story is more like a script for a television series. Quoting the author:

“It can be seen that three troubles were the causes of Tamerlane's illness, which hastened his death. First, he was upset that his governor stole his tribute; then you need to know that the youngest of his three wives, whom he loved very much, in his absence, contacted one of his nobles. Having learned, upon his return, from the elder wife about the behavior of the younger, Tamerlane did not want to believe her words. Therefore, she told him to go to her and make her open the chest, where he would find a precious ring and a letter from her lover. Tamerlane did what she advised him, found a ring and a letter, and wanted to find out from his wife who she got them from. She then threw herself at his feet and begged him not to be angry, since these things were given to her by one of his close associates, but without malicious intent.

Tamerlane, however, came out of her room and ordered her to be beheaded; then he sent five thousand horsemen in pursuit of a dignitary suspected of treason; but this latter, warned in time by the head of the detachment sent after him, escaped with his wives and children, accompanied by five hundred people, to Mazanderan, where he was not persecuted by Tamerlane. The latter took to heart the death of his wife and the flight of his vassal to such an extent that he died. His funeral was celebrated throughout the region with great triumph; but it is remarkable that the priests who were in the temple heard his groans at night for a whole year.

In vain did his friends hope to put an end to these cries by distributing much alms to the poor. Therefore, the priests, after consulting, asked his son to let go to his homeland the people taken by his father from different countries, especially to Samarkand, where they sent many artisans who were forced to work there for him. They were all, indeed, set free, and immediately the cries ceased. Everything I have described so far happened during my six years of service with Tamerlane.

Golubev Andrey Viktorovich (kadykchanskiy, Kadykchansky, notes of a Kolyma resident). Born July 29, 1969 in the village of Kadykchan, Susumansky district, Magadan region. Graduated from the Vyborg Aviation Technical School and the Russian Customs Academy. He worked in the 2nd Kuibyshev united air squadron. Served in the Pskov customs. Lawyer, writer, historian.

7 467

680 years ago, on April 8, 1336, Tamerlane was born. One of the most powerful world rulers, famous conquerors, brilliant commanders and cunning politicians. Tamerlane-Timur created one of the largest empires in the history of mankind. His empire stretched from the Volga River and the Caucasus Mountains in the west to India in the southwest. The center of the empire was in Central Asia, in Samarkand. His name is shrouded in legends, mystical events and still inspires interest.

"Iron Lame" (the right leg was struck in the area of the kneecap) was an interesting personality, in which cruelty was combined with great intelligence, love of art, literature and history. Timur was a very brave and restrained man. He was a real warrior - strong and physically developed (a real athlete). A sober mind, the ability to make the right decisions in difficult situations, foresight and talent as an organizer allowed him to become one of the greatest rulers of the Middle Ages.

Timur's full name was Timur ibn Taragai Barlas - Timur son of Taragai from Barlas. In the Mongolian tradition Temir means "iron". In medieval Russian chronicles, it was referred to as Temir Aksak (Temir - "iron", Aksak - "lame"), that is, Iron Lame. In various Persian sources, the Iranianized nickname Timur-e Liang - "Timur the Lame" is often found. It passed into Western languages as Tamerlane.

Tamerlane was born on April 8 (according to other sources - April 9 or March 11), 1336 in the city of Kesh (later called Shakhrisabz - "Green City"). This entire region was called Maverannahr (in translation - “what is beyond the river”) and was located between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. It has been part of the Mongol (Mughal) empire for a century now. The word "Mongols", in the original version "Moguls" comes from the root word "could, can" - "husband, mighty, mighty, powerful." From this root came the word "Moguls" - "great, powerful." The family of Timur was also a representative of the Turkified Mongols-Moguls.

It is worth noting that the then Mongols-Moguls were not Mongoloids, like the modern inhabitants of Mongolia. Tamerlane himself belonged to the so-called South Siberian (Turanian) race, that is, a mixture of Caucasians and Mongoloids. The mixing process then took place in the south of Siberia, in Kazakhstan, Central Asia and Mongolia. Caucasoids (Aryans-Indo-Europeans), who for many millennia inhabited these areas, and gave passionary impetuses to the development of India, China and other regions, mixed with the Mongoloids. They completely dissolve in the Mongoloid and Turkic ethnic arrays (the genes of the Mongoloids are dominant), passing on to them some of their characteristics (including militancy). However, in the XIV century the process was not yet completed. Therefore, Timur had blond (red) hair, a thick red beard, and anthropologically belonged to the South Siberian race.

Timur's father, the petty feudal lord Taragai (Turgai), came from the Barlas tribe, which at one time was among the first, united by Temuchin-Genghis Khan. However, he did not belong to the direct descendants of Temuchin, so later Tamerlane could not claim the khan's throne. The founder of the Barlas clan was considered a large feudal lord Karachar, who at one time was an assistant to the son of Genghis Khan Chagatai. According to other sources, Tamerlane's ancestor was Irdamcha-Barlas - allegedly the nephew of Khabul Khan, the great-grandfather of Genghis Khan.

Little is known about the childhood of the future great conqueror. Timur's childhood and youth were spent in the mountains of Kesh. In his youth, he loved hunting and equestrian competitions, javelin throwing and archery, and had a penchant for war games. There is a legend about how ten-year-old Timur once drove home sheep, and together with them managed to drive a hare, not allowing him to fight off the herd. At night, frightened by his too quick son, Taragai cut the tendons on his right leg. Allegedly, then Timur became lame. However, this is only a legend. In fact, Timur was wounded in one of the skirmishes during his turbulent youth. In the same fight, he lost two fingers on his hand, and all his life Tamerlane suffered from severe pain in his crippled leg. Perhaps this could be associated with outbursts of rage. Thus, it is known for sure that the boy and the youth were distinguished by great dexterity and physical strength, and from the age of 12 he took part in military skirmishes.

Start of political activity

The Mongol Empire was no longer a single state, it broke up into destinies-uluses, there were constant internecine wars that did not bypass Maverannahr, which was part of the Chagatai ulus. In 1224, Genghis Khan divided his state into four uluses, according to the number of sons. The second son Chagatai got Central Asia and nearby territories. The ulus of Chagatai covered, first of all, the former state of the Karakitays and the land of the Naimans, Maverannahr with the south of Khorezm, most of the Semirechye and East Turkestan. Here, since 1346, the power actually belonged not to the Mongol khans, but to the Turkic emirs. The first head of the Turkic emirs, that is, the ruler of the interfluve of the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, was Kazgan (1346–1358). After his death, serious unrest began in Maverannahr. The Mongol (Mogul) Khan Toglug-Timur invaded the region and captured the region in 1360. Soon after the invasion, his son Ilyas-Khodzhi was appointed governor of Mesopotamia. Part of the Central Asian nobles took refuge in Afghanistan, the other - voluntarily submitted to Toglug.

Among the latter was the leader of one of the detachments - Timur. He began his activity as the ataman of a small detachment (gang, gang), with which he supported one or the other side in civil strife, robbed, attacked small villages. The detachment gradually grew to 300 horsemen, with whom he entered the service of the ruler of Kesh, the head of the Barlas tribe, Haji. Personal courage, generosity, the ability to understand people and choose his assistants, and the pronounced qualities of a leader brought Timur wide popularity, especially among warriors. Later, he received the support of Muslim merchants, who began to see in the former bandit a protector from other gangs and a true Muslim (Timur was religious).

Timur was approved as the commander of the Kashkadarya tumen, the ruler of the Kesh region and one of the assistants to the Mogul prince. However, he soon quarreled with the prince, fled after the Amu Darya to the Badakhshan mountains and joined with his forces the ruler of Balkh and Samarkand, Emir Hussein, the grandson of Kazgan. He strengthened his alliance by marrying the emir's daughter. Timur with his warriors began to raid the lands of Khoja. In one of the fights, Timur was crippled, becoming the "Iron Lame" (Aksak-Timur or Timur-Leng). The fight against Ilyas-Khoja ended in 1364 with the defeat of the latter's troops. The uprising of the inhabitants of Maverannahr, which was dissatisfied with the cruel eradication of Islam by pagan warriors, helped. The Mughals were forced to retreat.

In 1365, the army of Ilyas-Khoja defeated the troops of Timur and Hussein. However, the people revolted again and expelled the Mughals. The uprising was led by the Serbedars (Persian “gallows”, “desperate”), supporters of the dervishes who preached equality. People's rule was established in Samarkand, the property of the rich sections of the population was confiscated. Then the rich turned to Hussein and Timur for help. In the spring of 1366, Timur and Hussein crushed the uprising by executing the Serbedar leaders.

"Great Emir"

Then there was a discord in the relationship between the two leaders. Hussein hatched plans to take the post of supreme emir of the Chagatai ulus, like his grandfather Kazagan, who seized this position by force during the time of Kazan Khan. Timur stood on the way to sole power. In turn, the local clergy took the side of Timur.

In 1366, Tamerlane rebelled against Hussein, in 1368 he made peace with him and again received Kesh. But in 1369 the struggle continued, and thanks to successful military operations, Timur fortified himself in Samarkand. In March 1370, Hussein was taken prisoner in Balkh and killed in the presence of Timur, although without his direct order. Hussein was ordered to be killed by one of the commanders (due to blood feud).

On April 10, Timur took the oath from all the military leaders of Maverannahr. Tamerlane declared that he was going to revive the power of the Mongol Empire, declared himself a descendant of the mythical progenitor of the Mongols, Alan-Koa, although, being a non-Chinghisid, he was content with the title of only "great emir." With him was "zits-khan" - the real Genghisid Suyurgatmysh (1370-1388), and then the son of the latter Mahmud (1388-1402). Both "khans" did not play any political role.

The city of Samarkand became the capital of the new ruler; Timur moved the center of his state here for political reasons, although he initially leaned towards the Shakhrisabz option. According to legend, choosing the city that was to become the new capital, the great emir ordered to slaughter three rams: one in Samarkand, another in Bukhara and the third in Tashkent. Three days later the meat in Tashkent and Bukhara was rotten. Samarkand became "the home of the saints, the birthplace of the purest Sufis and a gathering of scholars." The city has really turned into the largest cultural center of the vast region, the “Shining Star of the East”, the “Precious Pearl”. Here, as well as in Shakhrisabz, the best architects, builders, scientists, writers from all countries and regions conquered by the emir were brought. An inscription was made on the portal of the beautiful Ak-Saray palace in Shakhrisabz: “If you doubt my power, look what I built!” Ak-Saray was built for 24 years, almost until the death of the conqueror. The arch of the entrance portal of Ak-Saray was the largest in Central Asia.

In fact, architecture was the passion of the great statesman and commander. Among the outstanding works of art that were supposed to emphasize the power of the empire, the Bibi Khanum Mosque (aka Bibi-Khanym; built in honor of Tamerlane's wife) has survived to this day and amaze the imagination. The mosque was erected by order of Tamerlane after his victorious campaign in India. It was the largest mosque in Central Asia; 10,000 people could pray in the courtyard of the mosque at the same time. Also worth noting is the Gur-Emir Mausoleum - the family tomb of Timur and the heirs of the empire; the architectural ensemble of Shakhi-Zinda - an ensemble of mausoleums of the Samarkand nobility (all this in Samarkand); the mausoleum of Dorus-Siadat in Shakhrisabz is a memorial complex, first for the prince Jahongir (Timur loved him very much and prepared him to be the heir to the throne), later he began to act as a family crypt for part of the Timurid dynasty.

Bibi-Khanym Mosque

Mausoleum Gur-Emir

The great commander did not receive a school education, but he had a good memory and knew several languages. A contemporary and prisoner of Tamerlane, Ibn Arabshah, who knew Tamerlane personally since 1401, reports: "As for Persian, Turkic and Mongolian, he knew them better than anyone else." Timur liked to talk with scientists, especially to listen to the reading of historical works, at court there was even a position of "reader of books"; stories of brave heroes. The great emir showed respect to Muslim theologians and hermit dervishes, did not interfere in the management of the property of the clergy, ruthlessly fought against numerous heresies - he also included philosophy with logic, which he forbade to engage in. The Christians of the captured cities should have rejoiced if they remained alive.

During the reign of Timur, a special cult of the Sufi teacher Ahmed Yasawi was introduced in the territories subordinate to him (primarily Maverannakhr). The commander claimed that he introduced a special worship to this outstanding Sufi, who lived in the XII century, after a vision at his grave in Tashkent, in which the Teacher appeared to Timur. Yasawi allegedly appeared to him and ordered to memorize a poem from his collection, adding: “In difficult times, remember this poem:

You, who at will are free to turn the dark night into day.

You who can turn the whole earth into a fragrant flower garden.

Help me in the difficult task that lies ahead of me and make it easy.

You who make everything difficult easy."

Many years later, when during a fierce battle with the army of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid, Tamerlane's cavalry rushed to the attack, he repeated these lines seventy times, and the decisive battle was won.

Timur took care of the observance by his subjects of the prescriptions of religion. In particular, this led to the appearance of a decree on the closure of entertainment establishments in large trading cities, although they brought large income to the treasury. True, the great emir himself did not deny himself pleasures, and only before his death he ordered the destruction of the belongings of feasts. Timur found religious reasons for his campaigns. So, it was necessary to urgently teach heretics a lesson in Shiite Khorasan, then to avenge the Syrians for the insults inflicted on the family of the prophet in their time, then to punish the population of the Caucasus for drinking wine there. Vineyards and fruit trees were destroyed in the occupied lands. Interestingly, later (after the death of the great warrior), the mullahs refused to recognize him as an orthodox Muslim, since he "honored the laws of Genghis Khan above religious ones."

Tamerlane devoted all the 1370s to the fight against the khans of Dzhent and Khorezm, who did not recognize the power of Suyurgatmysh Khan and the great emir Timur. It was restless on the southern and northern borders of the border, where Mogolistan and the White Horde were causing concern. Moghulistan (Mughal ulus) is a state that was formed in the middle of the 14th century on the territory of South-Eastern Kazakhstan (south of Lake Balkhash) and Kyrgyzstan (the coast of Lake Issyk-Kul) as a result of the collapse of the Chagatai ulus. After the capture of Sygnak by Urus Khan and the transfer of the capital of the White Horde to it, the lands subject to Timur were in even greater danger.

Soon the power of Emir Timur was recognized by Balkh and Tashkent, but the Khorezm rulers continued to resist the Chagatai ulus, relying on the support of the rulers of the Golden Horde. In 1371, the ruler of Khorezm attempted to capture southern Khorezm, which was part of the Chagatai ulus. Timur made five trips to Khorezm. The capital of Khorezm, rich and glorious Urgench, fell in 1379. Timur waged a stubborn struggle with the rulers of Mogolistan. From 1371 to 1390, Emir Timur made seven campaigns against Mogolistan. In 1390, the Moghulistan ruler Kamar ad-din was finally defeated, and Mogolistan ceased to threaten the power of Timur.

Further conquests

Having established himself in Maverannahr, the Iron Lame proceeded to large-scale conquests in other parts of Asia. Timur's conquest of Persia in 1381 began with the capture of Herat. The unstable political and economic situation in Persia at the time favored the invader. The revival of the country, which began during the reign of the Ilkhans, again slowed down with the death of the last representative of the Abu Said clan (1335). In the absence of an heir, the throne was occupied in turn by rival dynasties. The situation was aggravated by the clash between the dynasties of the Mongolian Jalayrids, who ruled in Baghdad and Tabriz; the Perso-Arab family of the Muzafarids, who were in power in Fars and Isfahan; Harid Kurtami in Herat. In addition, local religious and tribal alliances, such as the Serbedars (who rebelled against the Mongol oppression) in Khorasan and the Afghans in Kerman, and petty princes in the border regions participated in the civil war. All these warring dynasties and principalities could not jointly and effectively resist Timur's army.

Khorasan and all of Eastern Persia fell under his onslaught in 1381-1385. The conqueror made three large campaigns in the western part of Persia and the regions adjacent to it - a three-year (from 1386), a five-year (from 1392) and a seven-year (from 1399). Fars, Iraq, Azerbaijan and Armenia were conquered in 1386–1387 and 1393–1394; Mesopotamia and Georgia came under the rule of Tamerlane in 1394, although Tiflis (Tbilisi) submitted as early as 1386. Sometimes vassal oaths were taken by local feudal lords, often close military leaders or relatives of the conqueror became the heads of the conquered regions. So, in the 80s, Timur's son Miranshah was appointed ruler of Khorasan (later Transcaucasia was transferred to him, and then the west of his father's power), Fars was ruled for a long time by another son - Omar, and finally, in 1397, Timur was the ruler of Khorasan, Seistan and Mazanderan appointed his youngest son - Shahrukh.

It is not known what prompted Timur to conquer. Many researchers tend to the psychological factor. Like, the emir was driven by irrepressible ambition, as well as mental problems, including those caused by a wound in his leg. Timur suffered from severe pains and they caused outbursts of rage. Timur himself said: "The whole space of the inhabited part of the world is not worth having two kings." In fact, this is a call for globalization, which is also relevant in the modern world. Alexander the Great and the rulers of the Roman Empire, Genghis Khan, also acted.