Peter I after the victory over Charles XII, who was considered the best commander in Europe at that time, apparently believed in the power of his army and in his abilities as a strategist. And not only he himself believed in it, but also his entire court, the government and even his generals. The frivolity in the preparation, organization and implementation of the campaign was simply incredible. As a result, only some miracle allowed him, his wife Catherine and members of Peter’s government, who for some reason were dragged along with the army, to remain alive. But Peter lost the army, the one that defeated the Swedes. The corpses of soldiers were lying all along the retreat route.

Prut campaign 1711.

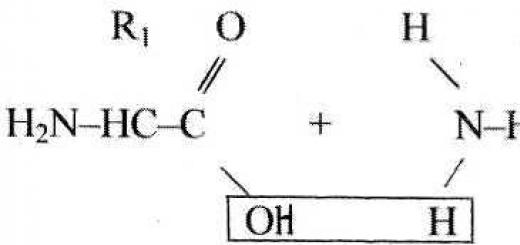

Peter I’s plan was specific - to cross the Danube a little higher from its confluence with the Black Sea and move across Bulgaria to the southwest until the second capital of the Sultan, Adrianople, was threatened. (The Turkish name of the city is Edirne. It was the capital of Turkey in 1365 - 1453). In Adrianople, Peter hoped for reinforcements from 30 thousand Vlachs and 10 thousand Moldovans. To justify his campaign in the Balkans, Peter used a proven ideological weapon - the Orthodox faith. In his address to the nations Balkan Peninsula Those who professed Christianity were told: “All good, pure and noble hearts must, despising fear and difficulties, not only fight for the Church and the Orthodox faith, but also shed their last blood.”

There were a lot of people who wanted to take part in the celebration of Moscow weapons. Everyone wanted to be present at the great victory over Turkey, and especially over the Crimean Khanate. After all, back in 1700, Peter and his Muscovite kingdom paid a humiliating tribute to the Crimean Tatars. The whole world knew about this humiliation and constantly reminded the Muscovites. So Dositheus, Orthodox Patriarch Jerusalem, wrote: “There are only a handful of Crimean Tatars... and yet they boast that they receive tribute from you. The Tatars are Turkish subjects, which means that you are Turkish subjects.” That is why the Chancellor of the State G.I. Golovkin, Vice-Chancellor P.P. Shafirov, clergyman Feofan Prokopovich, Catherine, about two dozen court ladies and many others ended up in Peter’s convoy. It was supposed to recapture Constantinople from the Turks and subjugate to Moscow the lands that were once part of Byzantine Empire. Our intentions were serious, but we were going on a picnic.

Having celebrated the two-year anniversary of the Poltava victory with his guards regiments on June 27 (July 8, 1711) in the steppes of Moldavia and drinking his favorite Magyar wine, Peter on the same day sent his cavalry, 7 thousand sabers, under the command of General Rene for capture Danube city Brailov, where the Turkish army, moving towards the Muscovites, concentrated its supplies. General Rene had to capture them, or, as a last resort, burn them. And three days later the infantry crossed the Prut and moved south along the western bank in three columns. The first was led by General Janus, the second by the Tsar, and the third by Repnin. On July 8, the vanguard units of General Janus met the Turkish troops and retreated to the royal column. The Tsar's orders to Repnin to urgently bring a third column to help the first two were in vain. Repnin's soldiers were pinned down by the Tatar cavalry in Stanilesti and could not move. The alarmed king ordered a retreat towards Stanileshti. The retreat began at night and continued all morning. It was a terrible transition. The Turks were hot on their heels and continuously attacked Peter's rearguard. Tatar detachments galloped back and forth between the carts of the convoy, and almost all of it perished. The exhausted infantry suffered from thirst. The Turks completely surrounded the defenders' camp on the banks of the Prut. Turkish artillery approached - the guns were deployed in a wide semicircle so that by nightfall 300 guns were looking at the camp with their muzzles. Thousands of Tatar cavalry controlled the opposite bank. There was nowhere to run. The soldiers were so exhausted from hunger and heat that many could no longer fight. It was not easy to even get water from the river - those sent for water came under heavy fire.

They dug a shallow hole in the middle of the camp, where they hid Catherine and the accompanying ladies. This shelter, fenced with carts, was a pitiful defense against Turkish cannonballs. The women cried and howled. The next morning a decisive Turkish offensive was expected. One can only imagine what thoughts overwhelmed Peter. The likelihood that he, the Moscow Tsar, the Poltava winner, would be defeated and transported in a cage through the streets of Constantinople was very high.

What did the king do? Here are the words of Peter's contemporary F.I. Soimonov: "... the Tsar's Majesty did not order to enter into the general battle... He ordered... to place a white flag among the trenches..." White flag meant surrender. Peter ordered his envoy, P.P. Shafirov, to agree to any conditions “except slavery,” but to insist on immediate signing, because the troops were dying of hunger. And here are the lines from P.P. Shafirov’s report to the tsar: “... the vizier ordered to be with him. And when we came to him, the Crimean Khan and a man with ten Kube-viziers and a pasha, including the Janissary aga, were sitting with him ... and the khan stood up and went out angry and said that he had told them before that we would fool them.”

To ensure the safety of signing the Act of Surrender, on the night of July 12, a dense corridor of Turkish guard soldiers was built between the surrounded camp and the vizier’s tent. That is, although negotiations with the vizier were conducted by Vice-Chancellor P.P. Shafirov, Peter I had to personally sign the Act of Surrender in the vizier’s tent. (The peace treaty between the kingdom of Moscow and the Ottoman Empire was signed in Adrianople in 1713).

If the Turkish commanders really received huge bribes - ransom for the tsar and his courtiers, then the Crimean Khan did not receive any ransom from Peter I. It was the Crimean Khan Davlet-Girey who spoke out so that “the Poltava winner in a cage would be taken through the streets of Constantinople.” Despite the fact that the Crimean Khan was very dissatisfied with the signed document, he still did not destroy the remains tsarist army during the retreat, although he could easily have done this. From an army of 54 thousand, Peter withdrew about 10 thousand people beyond the Dniester on August 1, completely demoralized. The Moscow army was destroyed not so much by the Turks and Tatars as by ordinary famine. This hunger haunted Peter's army from the first day of its crossing of the Dniester, for two whole months.

Petr Pavlovich Shafirov.

According to the testimony of "Sheets and papers...Peter the Great". From July 13 to August 1, 1711, the troops lost from 500 to 600 people every day who died of starvation. Why then did the Crimean Khan Davlet-Girey, having the opportunity, not destroy the Moscow army and the Tsar of Moscow? After all, in order for the Crimean Khan to release the Moscow Tsar, his tributary, from his hands, the power of the vizier Batalji Pasha was not enough. The Khan was a ruler on his territory and had enough strength and capabilities to destroy his eternal enemy after the Turkish army retreated to the south and the Moscow army to the north.

However, Davlet-Girey did not do this. Apparently the Moscow Tsar took some tactical steps, since the Crimean Khan let him out of his hands. What Peter I did to save himself, his wife and the remnants of his army is still being hidden most carefully. He signed a letter of oath confirming his vassal dependence on the Chingizid family. There is quite serious evidence that Prince Peter of Moscow (the Crimean khans never recognized the royal title of the Moscow Grand Dukes, which, in their opinion, was completely illegally appropriated by Ivan the Terrible), was forced to sign just such a shameful document.

And about some more events and legends associated with this campaign.

150 thousand rubles were allocated from the treasury to bribe the vizier; smaller amounts were intended for other Turkish commanders and even secretaries. The vizier was never able to receive the bribe promised to him by Peter. On the night of July 26, the money was brought to the Turkish camp, but the vizier did not accept it, fearing his ally, the Crimean Khan. Then he was afraid to take them because of the suspicions raised by Charles XII against the vizier. In November 1711, thanks to the intrigues of Charles XII through English and French diplomacy, Vizier Mehmed Pasha was removed by the Sultan and, according to rumors, was soon executed.

According to legend, Peter's wife Ekaterina Alekseevna donated all her jewelry for bribery, but the Danish envoy Just Yul, who was with the Russian army after it left the encirclement, does not report such an act of Catherine, but says that the queen distributed her jewelry to save the officers and then, after peace was concluded, she gathered them back.

----

And now let's fast forward 25 years, during the time of Anna Ioannovna, when, for a completely unknown reason, in 1736, the Russian army of 70 thousand soldiers and officers, together with the corps of Ukrainian Cossacks, under the command of Field Marshal Minich (the German Minich did a lot for the development Russian army, in particular, he introduced field hospitals for the first time) set out from the area of the present city of Tsarichanka, Dnepropetrovsk region, and by May 17 approached Perekop. On May 20, Perekop was taken and the field marshal’s army moved deep into the Crimea. In mid-June, Minikh approached the city of Kezlev (Evpatoria) and took it by storm. After this, Minich's army headed to the capital of the Crimean Khanate - Bakhchisarai and took it by storm on July 30. The main goal of the campaign was the state archive of the Crimean Khanate. Minikh removed many documents from the archive (possibly the charter of Peter I), and the remaining documents were burned along with the archive building. It is believed that Anna Ioannovna organized a raid on the Crimean archives in pursuance of the secret will of Peter I. Field Marshal Minich completed his main task (which very few knew about) - to seize the Khan’s archives, so already in early August he left Bakhchisarai, and on August 16 passed Perekop and with the remnants of the shabby army moved to Hetman Ukraine.

Minich lost more than half of his army, mainly due to epidemics, but the empress was pleased with the work done and generously rewarded the general with estates in different parts of the country.

Anna Ioannovna.

Apparently Anna Ioannovna did not receive all the documents she wanted. That is why in 1737 the army of Field Marshal Lassi made a second campaign to the Crimea. He no longer visited either Evpatoria or Bakhchisarai. He was interested in other ancient cities of Crimea, mainly Karasu-Bazar, where the Crimean Khan moved after the pogrom of Bakhchisarai. We were looking for something! By the way, the generals of his army, unaware of the true objectives of the campaign, offered many very practical ideas about the routes and methods of conducting this military campaign, but Lassi remained unshaken and even threatened to expel the generals from the army.

Field Marshal Minich

The march of Minich's army in 1736

The epic of classifying ancient Crimean documents did not end there. Since most of the archival materials of the Crimean Khanate were not found either during the campaigns of 1736-1737, or after the Russian occupation of Crimea in 1783 (here A.V. Suvorov was involved in the search), Russian the authorities sent one expedition after another to conduct searches. Many interesting documents were found, but all of them are still classified.During the Northern War in the Battle of Poltava in 1709, Russia inflicted a crushing defeat on the Swedish army of King Charles 12. The Swedish army was practically destroyed, and Charles 12 fled to Turkey. There he hid in the Bendery fortress (on the territory of modern Transnistria) and for 2 years persuaded the Sultan Ottoman Empire to war with Russia.

As a result, in 1711 the Sultan declared war on Russia. But military operations were inactive. The Turks did not want a large-scale war, and limited their participation only to sending their vassals - Crimean Tatars- in regular raids across the territory of modern Ukraine and Moldova. Peter the Great also did not want an active war, he simply wanted to raise a peasant uprising against the Ottomans.

Many historians argue that Peter himself is to blame for declaring war. Because after the Battle of Poltava, the Swedish army was almost completely destroyed, and the Russian Tsar did not pursue Charles 12, allowing him to freely leave the territory of the state.

The pursuit began only three days after the end of the battle, when precious time had already been lost and it was impossible to catch up with the enemy. This mistake was worth the fact that during the 2 years of his stay in Turkey, Charles 12 was able to turn the Turkish Sultan against Russia.

The Russian army, as well as the Moldovan corps, took part in this military campaign on the Russian side. The total number of troops was about 86,000 people and 120 guns.

On the part of the Ottoman Empire, the army of the Turks and the army of the Crimean Khanate took part in the war. The total strength of the enemy army was about 190,000 people and 440 guns.

For the Prut campaign, Peter the Great transferred his army through Kyiv to the territory of Poland. On June 27, 1711, the Russian army, under the leadership of Peter the Great, as well as his closest ally Sheremetev, crossed the Dniester River and began its movement towards the Prut River. This campaign lasted less than a week, but the poor quality of its organization led to the fact that this transition (during which there were no battles with the enemy) cost the lives of many Russian soldiers. The reason was lack of supplies. Soldiers died from basic dehydration.

On July 1, Sheremetev’s troops approached the eastern bank of the Prut and here they were suddenly attacked by the Crimean Tatar cavalry. After a short battle, 280 Russian soldiers died. The raid was repelled.

On July 6, Peter the Great ordered to cross the Prut River. After crossing the river, the Moldavian ruler Dmitry Cantemir joined the Russian army.

On July 14, the army united again. 9,000 soldiers remained in the city of Iasi to protect the garrison. The rest of the army continued to participate in the campaign.

On July 18, the first battle of this campaign began. At 14:00 the Turkish army attacked the rear of the Russian army. Despite their numerical superiority, the Turkish troops were forced to retreat, as their offensive was unorganized. They had no artillery and their infantry was poorly armed.

On July 19, the Turks began to encircle the Russian army. In the middle of the day, the Turkish cavalry completed a complete encirclement, but did not attack. Peter the Great decided to go upstream of the river to find a more convenient place for the battle. The movement began at night.

On July 20, during the movement, a significant gap opened up in the Russian army, which the Turks immediately took advantage of and attacked the convoy, which was left without cover. After this, the pursuit of the main forces began. Peter the Great took up defensive positions near the village of Stanilesti and prepared for battle. By evening, large forces of the Turkish army, Crimean Tatars and Zaporozhye Cossacks began to arrive here. The battle has begun. The Turks were unable to defeat the Russians; their attack was repulsed. The losses of the Russian army during this battle amounted to 750 people killed and more than a thousand wounded. Turkish losses were even more significant, amounting to about 8,000 killed and wounded.

On July 21, the army of the Ottoman Empire began a massive artillery shelling of the positions of the Russian army. In between shelling, Russian positions were attacked by cavalry and infantry. Despite the enormous superiority of their army, the Turks could not break the Russian resistance. Peter the Great, realizing the hopelessness of the position of his army, proposed at a military council to make peace with the Turks. As a result, Shafirov was sent to the Turks, who was given the broadest powers of the ambassador.

The wife of Peter the Great, Catherine, gave all her jewelry to hand them over to the Turkish Sultan, encouraging him to conclude peace. This once again proves that the position of the Russian army in this war was so difficult. Peter the Great himself, sending his ambassador, told him to agree to any peace conditions except one - the loss of St. Petersburg is unacceptable.

Negotiations between the parties to conclude peace lasted two days. As a result, on July 22, Peter’s ambassadors returned. The requirements were:

Russia undertakes to transfer the Azov fortress to Turkey;

the Taganrog fortress, built to protect the exit to the Black Sea, must be destroyed;

complete renunciation of political and military interference in the affairs of Poland and the Zaporozhye Cossacks;

free pass for King Charles 12th to Sweden.

General Russian army Sheremetyev, remained hostage to the Ottoman Empire until Charles 12 passed through Russian territory.

The Prut campaign was completed with the signing of a peace treaty on July 23, 1711. The signing of the agreement took place at 18:00, after which the Russian army retreated to the city of Iasi, and then returned to Moscow through Kyiv. As for Charles 12, he opposed this peace agreement and insisted that the Ottoman Empire continue the war.

“You fought with them. We also saw their valor. If you want to fight with Russia, fight on your own, and we will conclude a peace treaty” (Baltaji Mohmed Pasha)

The signing of peace between Russia and Turkey had a huge impact political significance, for the Russian Tsar, being threatened with the complete destruction of his army, was able to make peace through diplomatic persuasion. But one very significant amendment needs to be made - the signing of such a peace became permissible only because of Turkey’s interest. The Sultan understood that the destruction of the Russian army would contribute to the rise of Sweden, which was also unacceptable.

Russia lost everything it had conquered over the years in one day. The loss of the Black Sea Fleet was especially painful.

To the 305th anniversary of the Prut campaign of Peter the Great.

The Prut campaign of 1711 can safely be considered the greatest failure of Peter the commander. Rufin Gordin, a popular author, called the Prut campaign “a cruel embarrassment for Tsar Peter.” historical novels. The failure was aggravated by the fact that we were no longer talking about a young, inexperienced king, as Peter was during the period, but about a mature military leader who had many convincing victories behind him. And under his command was not pampered during the reign of Fyodor and Sophia Streltsy army, slightly diluted with “regiments of the new system”, “elected” regiments and “amusing” guards, but real regular troops and real guards, moreover, veterans tested in battles and campaigns. However, the campaign against the Turks ended in a military disaster for Peter, and the peace that followed ended in territorial concessions. The impression is compounded by the fact that this disaster happened exactly 2 years after the brilliant victory near Poltava, which Peter won over one of the best commanders of the then Western Europe. And what was finishing off was the fact that the Europeanized army of Peter was opposed on the Prut by poorly organized troops of the Turks, who did not have a regular army. There was something to raise the head of opponents of Peter’s reforms within Russia!

It was all the more unexpected for me to see on the book shelves the book “The Prut Campaign: Defeat on the Path to Victory?”, written by E.V. Belova. The author of the book has his own, very fresh and unexpected view of the events of 305 years ago, taken in the general context of Russian-Turkish, Ukrainian-Turkish and Russian-Ukrainian relations XVII- XVIII centuries. And also in the context of Russia’s ties with the oppressed Christian peoples of the Ottoman Empire.

So what happened in 1711? And something happened that Peter managed to safely avoid 16 years before. History sometimes plays bitter jokes on the winners. In fact, Peter repeated the mistake of his predecessor, Prince Vasily Golitsyn, who destroyed his army in the Crimean campaigns due to the fact that he moved through the deserted and waterless steppes.

The Prut campaign was not a political adventure. Peter can be reproached for anything, but not for adventurism. Waging a difficult long-term war with the Swedes for possession of the Baltic coast, he made every possible effort to maintain Turkey's neutrality. For the time being, he succeeded in this, but in 1711 Turkey broke off the diplomatic leash. The Russian ambassador to Constantinople, Count Pyotr Tolstoy, was arrested and thrown into the Seven Towers Castle. Why this happened - I had the honor to talk about this, but here I’m simply stating an undoubted fact: the blame for starting the war lies entirely on the Turkish side, while Russia was forced to defend itself.

Peter had a choice - not to go with the army to the Prut, but to wait for the Turks in Right Bank Ukraine. Here the Russian army could rely on the friendly Ukrainian population and the allied Polish army. However, this would mean leaving the oppressed Christian population of the Ottoman Empire to their own fate, in which the Poltava victory of Russia aroused hopes for a speedy liberation from the Turkish yoke - since an Orthodox great power was emerging in Europe. With the beginning of the Russian-Turkish War, these hopes began to take more or less concrete shape. Moreover, Peter did not drive away emissaries from the Balkan and Danube Christians; on the contrary, he welcomed them in every possible way. In European Turkey, national liberation uprisings began to break out one after another. Peter, understanding the benefits of this national liberation movement, tried to reassure the rebels in every possible way with his letters and sent out appeals to those who were wavering. Peter's refusal to support this movement would not have been understood by the Church - it would have looked like a direct betrayal. And Peter, with all his disdain for the representatives of the clergy, the meaning Orthodox Church excellent for Russian society. And the second consideration, which Peter could not discount: by waiting for the Turks in Ukraine, he exposed the Russian-friendly Ukrainian population to all the horrors foreign invasion, and possibly occupation. And relations with Poland could well deteriorate if the Turkish army entered the territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth because of Russia. Poland was Russia's ally against the Swedes, but - at least officially - not against the Turks. After Poltava, Peter did not doubt his abilities. The Turks as an enemy were already well known to him - he personally beat them near Azov. And the army set out on a campaign.

The rulers of the Danube principalities, vassals from Turkey - Moldavia and Wallachia - called Russian troops to their territory, promising all kinds of assistance. In general, Moldova has already asked for Russian citizenship several times, and only the absence common border prevented Peter and his predecessors - Alexei Mikhailovich and Fyodor Alekseevich - from satisfying their request. These petitions from the Moldovan ruler Dmitry Cantemir were renewed with the beginning of the Russian-Turkish War. Accordingly, Peter and his formal commander-in-chief Boris Sheremetev had a firm hope of replenishing the principalities with both food supplies and numerous volunteers.

Peter had to hurry. If the Turkish army (and, according to available information, it outnumbered the Russian) had managed to occupy the principalities before Peter, it would have taken advantage of all their resources, suppressing any resistance. And resources - and above all food - were vital to Peter. That’s why Peter urged his field marshal Sheremetev, demanding at all costs to reach the Danube before the end of spring, and, if necessary, to requisition horses and oxen for carts from ordinary people. " For God’s sake, do not delay to the appointed place,” Peter wrote to Sheremetev, “for even now we have received packs of letters from all Christians who ask God Himself to hurry before the Turks, which is of great benefit. And if we are slow, then it will be ten times harder or barely possible to fulfill our intentions, and so we will lose everything through delay."

Boris Petrovich Sheremetev - formal commander-in-chief

Russian troops in the Prut campaign

On May 24, the Russian army crossed the Dniester. At the same time, there was a clash with the Turks, which cost the Russians two killed, and the Turks - 20. It seemed that Peter’s calculations about the tactical superiority of the Russian army were beginning to come true. The army entered Moldova, whose residents began to sign up as volunteers. In response, Peter strictly forbade making requisitions from Orthodox population- food and horses were actively purchased at market prices. Looting was punishable by death.

On June 1, a military council was convened, at which it became known that the Turks were 7 marches from the Danube. General Allart proposed, having captured the Bendery fortress, to remain on the Dniester and wait for the enemy here. In this case, the Turks would have to face a transition through the deserted and waterless steppe, which would certainly tire out their army and destroy a significant part of it. However, Allart's plan deprived the Russians of the opportunity to use the resources of Wallachia - and in Moldova the army was well replenished with volunteers and just as well acquired supplies. And the refusal to support the Wallachian ruler Brynkovyan would have been interpreted far from in favor of Peter and would not have contributed to the continuation of the anti-Ottoman uprisings in the Balkans. Taking these considerations into account, Peter rejected Allart's reasonable proposal. The army marched to the Danube. Now all the inconveniences of a campaign across the waterless and deserted steppe fell on the shoulders of the Russian troops.

Dmitry Cantemir, Moldavian ruler

On June 5, Russian troops approached the Prut, where they united with Cantemir and the volunteers who were gathered and brought by the Moldavian ruler. And on June 7 it became known that the Turks had crossed the Danube and were moving towards the Russians.

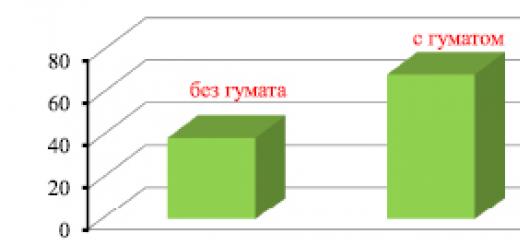

The further movement of the Russian army was greatly hampered by heat and drought. The horses died from thirst and lack of food, the mortality rate among soldiers reached 500 - 600 people a day. The situation was aggravated by the fact that Peter's Fast was in progress, and the grain was destroyed by an invasion of locusts. The Russian command was forced to issue a special order that the soldiers eat meat. But getting it turned out to be problematic due to the loss of livestock. Is it any wonder that the advanced detachment of the Russian cavalry, faced with the advanced forces of the Turkish army crossing the Prut, did not try to prevent them, but turned back?

Uniform of the Russian army during the Prut campaign.

Agree, this is not a very comfortable uniform for traveling in thirty-degree heat.

And then the following began. Early in the morning of July 8, 1711, the Turkish commander-in-chief (and also the grand vizier, i.e., the prime minister of Sultan Turkey) Baltaji Mehmet Pasha sent a “small” detachment of 3,700 cavalry men on a reconnaissance mission. This detachment squeezed into the gap between the advance detachment of Janus (to which Ensberg's division approached to help) and the main Russian forces. Sheremetev immediately lined up his troops and rolled out his cannons. It was ordered to shoot from an extremely short distance to ensure the maximum destructive power of the fire. One Turk, who came too close to the Russian battle formations, was immediately captured and interrogated. According to him, the strength of the Turkish army was 100 thousand cavalry and 50 thousand infantry.For comparison: the numberThe Russian army in the Prut campaign consisted of 38 thousand people plus 5-6 thousand people of poorly trained Moldavian militia. Despite such a huge advantage, Baltaji Mehmet Pasha did not dare to give battle - the glory of the Poltava winner became too loud, and the Turks themselves experienced the heavy hand of the Great Peter. In addition, two Swedish officers who defected from the Russian army to the Turks significantly overestimated the number of Russian troops (estimating it at 70 thousand).

So, the alignment before the battle did not look in favor of the Russians. Peter's army was exhausted long march and lack of food, the horses were brought to extreme exhaustion, while the Turkish cavalry had fresh horses and significantly outnumbered the entire Russian army. Peter's headquarters did not know about the indecisiveness of the Turkish commander-in-chief. Therefore, it was decided to retreat, fence off the site of the new camp with slingshots and form a square while the main forces of the Turkish army had not yet crossed the Prut. In order for the retreat to proceed as quickly as possible, Peter ordered the generals and officers to reduce the number of their carts with luggage, and to burn everything left behind.

At 11 pm on July 8th Russian troops began to retreat. At the same time, the guardsmen marching in the rearguard were delayed due to several overturned carts. The Turkish-Tatar cavalry poured into the resulting gap between the Preobrazhensky regiment and the rest of the army, trying to cut off the Preobrazhensky soldiers from the main forces and destroy them. The heroic guardsmen, as in 1700 near Narva, had to prove with deeds that Peter was not in vain calling them “Life Guards”, and that it was not in vain that he trusted his former “amusing” ones. The Preobrazhentsy stood against the enemy cavalry for 6 hours - and still managed to break through to their own.

Preobrazhentsy during the Prut campaign of 1711

Grenadier and drummer.

At 5 pm the next day, July 9, the Russian army stopped on the banks of the Prut near Stanilesti, where it built a fortified camp, set up slingshots, and then began to build a battle formation according to linear tactics. The Turks did not dare to attack for some time. The slow, insecure Baltaji Mehmet Pasha not only allowed the Russians to freely build a fortified camp, but also to erect a rampart half a man’s height against the positions of his army. The Turks, however, surrounded the Russian positions, occupying commanding heights. And, alas, there was nothing to oppose their multiple numerical superiority to Peter’s weakened army.

Peter convened a military council. At the same time, the vizier also convened a military council. Each side wanted to discuss their further actions, weighing the pros and cons. However, the Russian generals were not allowed to deliberate for a long time: having installed cannons on the dominant heights, the Turks began to fire at the Russian camp. And although the effect of the Turkish fire was small, Peter ordered his generals to take their place in the ranks. The Battle of Prut, which began with a skirmish between the Preobrazhensky regiment and the Tatars, resumed.

The first attack of the Janissaries on the Russian battle formations was spontaneous: Baltaji Mehmet Pasha at that time was still conferring with his deputy, and the army did not have time to focus on starting positions. But the Janissaries were impatient to cross arms with the “infidels,” and their commander Yusuf Agha, with an unfurled banner in his hands, led them into battle. The Turks ran to the slingshots, but seeing that the Russian camp was fortified and it would not be possible to take it on the move, they retreated back, taking cover behind one of the hills. 80 Russian grenadiers, on the orders of Sheremetev, launched a counterattack and pushed the Janissaries back another 30 steps. However, when they returned to their positions, the Turks gave chase.

In general, the battle was fierce. Peter himself, whose fearlessness is well known, paid tribute to his opponents: “The Turkish infantry, although disorganized, nevertheless fought very cruelly.” The Russians were able to repel the second attack of the Janissaries only with massive artillery fire, and they used both cannonballs and grapeshot. Despite the fact that the Turkish officers cut down the retreating sabers, the second attack of the Janissaries failed.

18th century Turkish infantry

After this, a very symptomatic dialogue took place in the Turkish camp between the deputy commander-in-chief and the Polish Count Poniatowski, a supporter of the pro-Swedish party and the head of the Polish detachment in Baltaji’s army. “My friend,” the Turkish commander told Poniatowski, “we risk being defeated.” This was said by a man whose army outnumbered the enemy six times. Let's remember this phrase: it will be useful to us later.

After this, the Turks launched an attack twice more and both times rolled back with heavy losses. By nightfall, despondency reigned in their camp. Russian generals, inspired by success, suggested that Peter gather the troops frustrated by the battle into a single fist and attack the Turkish camp. Peter, however, did not support this proposal. As we can now judge, this decision was wrong: the Turks themselves testified that if the Russians had launched a decisive counteroffensive, their army would certainly have wavered and fled, abandoning artillery, convoys and ammunition. But Peter knew nothing about the mood in the Turkish camp, and he could not risk the army - he still had to force Sweden, defeated at Poltava, but still far from accepting defeat, to peace. Peter himself subsequently pointed to the enormous numerical superiority of the Turks as the main reason that forced him to abandon the offensive. In addition, the Turkish army had large masses of cavalry (and therefore had greater maneuverability), while the Russian cavalry was exhausted by lack of food and a long march across the steppe. And Peter was not confident that after the entire army left the camp, this camp would not be captured by the Turkish cavalry, and his troops would be surrounded in the open.

As a result, a stalemate developed on the Prut. The Turks, repulsed four times, no longer risked attacking. But the Russians did not have enough strength to win. Under these conditions, Peter, after consulting with Sheremetev, decided to begin peace negotiations. As a parliamentarian authorized to sign peace on behalf of Russia, the famous diplomat Baron P.P., who was present with the army, went to the Turks. Shafirov. Peter understood that the Turks, although repulsed, and, it should be assumed, were quite demoralized, they had nowhere to rush. In addition, the Wallachian ruler Brincoveanu, with whom Peter set out on his ill-fated campaign, betrayed him, and all the resources prepared by the Volochs for Peter went to Baltaji and his army. Not by assault, but by starvation, the Turks could well have destroyed the small Russian army, whose soldiers had not eaten for three days. Therefore, Peter advised Shafirov to make concessions. The Tsar was ready to give Azov to the Turks, along with the newly built fortresses of Taganrog and Kamenny Zaton, recognize Stanislav Leshchinsky - the protege of the Swedes - as the king of Poland, and freely allow Charles XII into his possessions. Assuming that the Turks would work in favor of Charles, who had hidden in their possessions, Peter was ready to cede to the Swedes all the lands they had conquered, except St. Petersburg. In exchange for St. Petersburg, Peter agreed to give Pskov and surrounding territories to the Swedes - St. Petersburg was needed as an outlet to the Baltic Sea. Without him, the long-term war with the Swedes was completely worthless. The king probably expected to conquer other lands during further battles: There was no talk of peace with the Swedes. Moreover, Peter instructed Shafirov to cajole the pasha in every possible way so that he would not try too hard in favor of Karl. We see thus that Peter, even in such desperate circumstances, remained a far-sighted politician who understood that the root of his troubles was in the Turkish-Swedish alliance, that this alliance was a temporary and fragile phenomenon, and that it was entirely within his power to break it. Peter also knew very well about the level of corruption in the Ottoman Empire that went beyond all conceivable and inconceivable limits; he knew from his ambassador Count P.A. Tolstoy - and hoped to take advantage of this circumstance.

Baron P.P. Shafirov

In case the Turks did not want to make peace, Peter gave the order to prepare for a breakthrough. Weakened horses were ordered to be slaughtered, carts and papers were to be burned, and soldiers were to be properly fed by dividing the available food supplies. These measures, however, turned out to be unnecessary. Shafirov managed to make peace on much more favorable terms than Peter had expected. Baltaji did not demand any concessions in favor of the Swedes at all. Russia gave Azov to Turkey and pledged to raze the fortresses of Taganrog and Kamenny Zaton. All artillery, banners and ammunition of the Russian army were left untouched - instead, guns and ammunition from Kamenny Zaton were transferred to the Turks. Karl received complete freedom to return to Sweden whenever he wished and as he wished - it turned out that the Turks themselves were pretty tired of him, and they were waiting - they could not wait for an opportunity to send this restless guest out. Russia managed to defend the Moldavian ruler Dmitry Cantemir and his volunteers - they received the right to move to Russia. In addition, Russia pledged to withdraw its troops from Poland and not to persecute the Zaporozhye Cossacks-Mazepa, who had found shelter in the Sultan’s possessions. As guarantors that Russia would fulfill the conditions, the Turks kept Baron Shafirov and the son of the formal commander-in-chief of the Russian army, B.P., as hostages. Sheremetev - Mikhail. Peter ordered to immediately promote Mikhail Sheremetev from colonel to general and give him a salary for a year in advance, after which Sheremetev Jr. left for the Turks. I will add on my own behalf that this selfless young man, who willingly sacrificed his freedom for the interests of the Fatherland, undermined his health in the Yedikule dungeons and died on the way to Russia.

When Charles XII learned about the conclusion of the Prut Peace, he rushed headlong to the Turkish camp and began to shower Baltaji-Mehmet Pasha with reproaches, assuring him that victory was in their hands, and that he personally, with a detachment of loyal people, undertakes to bring Peter captive to the Turkish camp . Baltaji, who knew the value of this verbal diarrhea, allowed Karl to speak out, after which he melancholy remarked: “You have already tasted them (Russians - M.M.), and we have seen them too. And if you want, then attack, and I will make peace with them I will not violate what has been set." In general, as Shafirov later recalled, Baltaji did not hide his joy when he heard about the Russian proposal to cede Azov, after which the vizier immediately established a trusting relationship with the Russian envoy. In a conversation with Shafirov, Baltaji did not hide the fact that he considered Charles XII an intelligent man, but after a conversation with him he considered him a fool and a madman.

Peace was concluded on July 12, 1711. Immediately after this, the Janissaries, whom the stubbornness of the Russian defense had so recently brought into a state close to panic, began to approach the Russian camp, called the Russian soldiers "brothers" and began trading. Among the Russian officers there were people who spoke Turkish and Arabic languages, and soon the soldiers of Peter’s exhausted army could not deny themselves food - recent enemies generously supplied them with food. Baltaji himself ordered the donation of bread and rice to the Russian army for 11 days of travel.

The accommodating behavior of Baltaci Mehmet Pasha gave rise to rumors that the vizier had been bribed. They said, in particular, that Empress Catherine, who was present at the army, collected all the jewelry of the generals and officers' wives and, along with her own jewelry, sent them as a gift to the vizier. The figure of the bribe received by the vizier was even mentioned - 8 million rubles. It was also rumored that the queen personally came to the location of the Turks and gave herself to the vizier in order to negotiate more favorable conditions for her husband. This talk of bribery eventually cost Baltaji his life. However, upon mature reflection, one has to admit the groundlessness of such gossip. It is unlikely that Baltaji dared to accept a bribe from the Russians in the presence of a whole horde of Janissaries ready to revolt, who would certainly have torn him to pieces for treason. The reasons that caused the acquiescence of the Turks are much more prosaic. Let's list them.

First. Before the start of the Prut campaign, Peter sent a detachment of General Renne, consisting of 15 thousand cavalrymen, ahead of the main forces. Renne had orders to go behind the main Turkish forces, stir up an anti-Turkish uprising in Wallachia, and then cut off Baltaji's army from crossing the Danube. Just in the midst of negotiations between Baltaji and Shafirov, the vizier was informed that the Renne dragoons were storming Brailov. Baltaji was no fool and quickly realized what was going on. Yes, he managed to encircle Peter’s army, but (the vizier did not know the number of troops). As a result, the Turks themselves found themselves in a strategic environment and risked changing places with the Russians . If Peter had known about the actions of his general, his position would probably have become tougher, and the limit of possible concessions would have been disproportionately smaller. But Peter did not have information from Renne, but Baltaji received information about him.

Baltaci Mehmet Pasha

Second. The Janissaries were demoralized by the battle at Stanilesti and refused to go on the offensive again. The Englishman Sutton, whose friend was with the Turkish army, testified: " If the Russians knew about the horror and numbness that gripped the Turks, and were able to take advantage of their advantages by continuing the artillery shelling and making a sortie, the Turks, of course, would have been defeated." The Englishman is echoed by the leader of the Janissaries, Yusuf Agha: "If the Muscovites had camps had set out, then the Turks would have abandoned the guns and ammunition.". Let us also recall the words of the deputy Turkish commander-in-chief said to Poniatowski: “We risk being defeated.” But the Russians did not know about the moral state of the Janissaries, and in battle the Janissaries demonstrated extraordinary courage, as evidenced by Peter.

And third. Having destroyed the Russian army and captured Peter, the Turks simply did not have where to advance. Ahead were the same waterless steppes and villages depleted by locusts, the passage through which destroyed Peter’s army. Ahead was the transition through the territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and getting involved in the Polish- Turkish war Neither Baltaji nor the Sultan had any intentions. Then it was necessary to cross several large water barriers, such as the Dniester and Dnieper. And then - also to measure their strength with the Ukrainian Cossacks, most of whom remained loyal to Russia. The Turks have repeatedly experienced what Ukrainian Cossacks are like on their own skin and were not at all eager to fight with them. Thus, the peace signed by Baltaci fully met the national interests of Turkey, but fighting for the interests of the arrogant and arrogant Swedish king was not part of the Turkish plans. The Sultan understood this very well - that’s why he awarded his vizier (as well as the Crimean Khan who participated in the Battle of Prut) with expensive fur coats and sabers.

Battle of Stanilesti. Map.

So was there a “cruel embarrassment”? I think everyone who reads this article will be forced to admit: it wasn’t. Those who like to accuse Russia of “filling the enemy with corpses”, speaking about the campaign of 1711, could well exercise their wit... at the Turks: the losses of Russian troops in the battle of Stanilesti amounted to 3 thousand people versus 8 thousand for the Turks. Yes, Peter admitted his defeat in the Prut campaign, but this was caused not so much by military failures as by an incorrect assessment of the situation. From the beginning of the campaign until the conclusion of peace, the Russian Tsar had to make decisions in conditions close to complete uncertainty, while Baltaji had much more information. The army of the Poltava victors, nurtured by Peter, in 1711 withstood the blows of a many times superior enemy, avoided defeat and forced this enemy to eventually agree to peace, albeit unfavorable for Russia, but on much more favorable terms than Peter expected when starting negotiations. The enemies of Russia did not achieve a convincing victory, which gave rise to numerous rumors about bribes.

________________________________________ _______________

Notes

that is, for the return of historical Russian lands captured by the Swedes during the unsuccessful Livonian War and the Great Troubles of the early 17th century

The Turkish name is Yedikule. The castle was built in the 15th century; here the sultans kept their treasury. And here was the main political prison of the Ottoman Empire.

Afterwards, many in Europe generally realized that it was time to take Russia seriously, that the semi-barbaric “Muscovy” was a thing of the irrevocable past - in its place was a country leading an active foreign policy and capable of supporting its interests with force of arms. The fighting of the Great Northern War in 1710 - 1711 was already carried out on the territory of Western Europe itself, which further strengthened Russian Kingdom in this new status of his.

The Russian-Turkish War of 1711 - 1713 was quite officially declared by Peter as a liberation war, and its goal was proclaimed not so much to repel external aggression as to protect oppressed Christians. In 1711, Peter ordered the inscription on the banners of his army: “For the name of Jesus Christ and Christianity.” The banners turned red (the color of freedom!) and were decorated with images Orthodox cross. “We have the intention,” wrote Pyotr Alekseevich, “not only to be able to advance against the infidel enemy with an army, but also to enter into the middle of his reign with strong weapons, and to liberate the oppressed Orthodox Christians, if God allows, from his vile yoke.” In response, Metropolitan Stefan Yavorsky, who sharply criticized the everyday side of Peter's reforms and his own dissolute life, proclaimed Peter - no more, no less - the "second messiah." See Belova E.V. Prut campaign: defeat on the way to victory? - M.: Veche, 2011. - p. 145.

Quote by: Belova E.V. Decree. Op. - With. 154.

We, knowing how it all ended, find his proposal reasonable. But let’s put ourselves in the place of Peter, whose troops had already managed to win a number of tactical victories in the outbreak of the Russian-Turkish War and were so warmly received in Moldova. For him, Allart's advice looked, at best, like a manifestation of criminal indecision, and at worst, simply a betrayal.

However, the exhausted Russian dragoons on their half-dead horses still failed to evade the battle with the fresh Turkish-Tatar cavalry. So we have to agree with E.V. Belova is that if General Janus, the commander of the Russian dragoons, had acted more decisively, he might have been able to delay the crossing of the Turks for several days and capture several guns from them.

E.V. Belova gives an even smaller figure - according to her calculations, the Russian army did not exceed 15 thousand people.

“Life Guards” literally means “bodyguards,” that is, the personal security of the sovereign.

Stone Zaton Shafirov even tried to negotiate - they say, Russia needs the fortress for defense against Tatar raids.

Shefov N.A. The most famous wars and battles of Russia. - M.: Veche, 2000. - p. 200.

Right there.

Quote by: Belova E.V. Decree. Op. - With. 195.

Shefov N.A. Decree. Op. - With. 200.

Shefov N.A. Decree. Op. - With. 198. E.V. Belova cites an even lower figure for Russian losses.

Peter, exhausted by the long wait for news from Shafirov, sent him a note in which he advised: “If they truly talk about peace, bet with them for all

(emphasis mine - M.M.)

Prut campaign |

|

R. Prut, Moldova |

|

Defeat of Russia |

|

Opponents |

|

Commanders |

|

Tsar Peter I |

Vizier Baltaci Mehmed Pasha |

Marshal Sheremetev |

Khan Devlet-Girey II |

Strengths of the parties |

|

Up to 160 guns |

440 guns |

37 thousand soldiers, of which 5 thousand were killed in battle |

8 thousand killed in battle |

Prut campaign- a campaign in Moldavia in the summer of 1711 by the Russian army led by Peter I against the Ottoman Empire during the Russian-Turkish War of 1710-1713.

With the army led by Field Marshal Sheremetev, Tsar Peter I personally went to Moldova. On the Prut River, about 75 km south of Iasi, the 38,000-strong Russian army was pressed to the right bank by the allied 120,000-strong Turkish army and 70,000-strong cavalry Crimean Tatars. The determined resistance of the Russians forced the Turkish commander to conclude a peace agreement, according to which the Russian army broke out of a hopeless encirclement at the cost of ceding to Turkey Azov, previously conquered in 1696, and the coast of the Azov Sea.

Background

After the defeat in the Battle of Poltava, the Swedish king Charles XII took refuge in the possessions of the Ottoman Empire, the city of Bendery. French historian Georges Udard called the escape of Charles XII an "irreparable mistake" of Peter. Peter I concluded an agreement with Turkey on the expulsion of Charles XII from Turkish territory, but the mood at the Sultan’s court changed - the Swedish king was allowed to stay and create a threat to the southern border of Russia with the help of part of the Ukrainian Cossacks and Crimean Tatars. Seeking the expulsion of Charles XII, Peter I began to threaten war with Turkey, but in response, on November 20, 1710, the Sultan himself declared war on Russia. The real cause of the war was the capture of Azov by Russian troops in 1696 and the appearance of the Russian fleet in the Sea of Azov.

The war on Turkey's part was limited to the winter raid of the Crimean Tatars, vassals of the Ottoman Empire, on Ukraine. Peter I, relying on the help of the rulers of Wallachia and Moldavia, decided to make a deep campaign to the Danube, where he hoped to raise the Christian vassals of the Ottoman Empire to fight the Turks.

On March 6 (17), 1711, Peter I left Moscow to join the troops with his faithful friend Ekaterina Alekseevna, whom he ordered to be considered his wife and queen even before the official wedding, which took place in 1712. Even earlier, Prince Golitsyn with 10 dragoon regiments moved to the borders of Moldova; Field Marshal Sheremetev came from the north from Livonia to join him with 22 infantry regiments. The Russian plan was as follows: to reach the Danube in Wallachia, prevent the Turkish army from crossing, and then raise an uprising of the peoples subject to the Ottoman Empire beyond the Danube.

Allies of Peter in the Prut campaign

- On May 30, on his way to Moldova, Peter I entered into an agreement with the Polish king Augustus II on the conduct of military operations against the Swedish corps in Pomerania. The Tsar strengthened the Polish-Saxon army with 15 thousand Russian troops, and thus protected his rear from hostile actions from the Swedes. It was not possible to drag the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth into the Turkish war.

- According to the Romanian historian Armand Grossu, “delegations of Moldavian and Wallachian boyars knocked on the thresholds of St. Petersburg, asking the tsar to be swallowed up by the Orthodox empire...”

- The ruler of Wallachia, Constantin Brâncoveanu, sent a representative delegation to Russia back in 1709 and promised to allocate a 30,000-strong corps of soldiers to help Russia and pledged to provide the Russian army with food, and for this Wallachia was to become an independent principality under the protectorate of Russia. The Principality of Wallachia (modern part of Romania) was adjacent to the left (northern) bank of the Danube and was a vassal of the Ottoman Empire since 1476. In June 1711, when the Turkish army advanced to meet the Russian army, and the Russian army, with the exception of cavalry detachments, did not reach Wallachia, Brancoveanu did not dare to take the side of Peter, although his subjects continued to promise support in the event of the arrival of Russian troops.

- On April 13, 1711, Peter I concluded the secret Treaty of Lutsk with the Orthodox Moldavian ruler Dmitry Cantemir, who came to power with the assistance of the Crimean Khan. Cantemir brought his principality (a vassal of the Ottoman Empire from 1456) into vassalage of the Russian Tsar, receiving as a reward a privileged position in Moldova and the opportunity to pass on the throne by inheritance. Currently the Prut River is state border between Romania and Moldova, in the 17th-18th centuries. The Moldavian principality included lands on both banks of the Prut with its capital in Iasi. Cantemir added six thousand Moldavian light cavalry, armed with bows and pikes, to the Russian army. The Moldavian ruler did not have strong army, but with its help it was easier to provide provisions for the Russian army in arid regions.

- The Serbs and Montenegrins, upon learning of the approach of the Russian army, began to launch a rebel movement, but they were poorly armed and poorly organized and could not provide serious support without the arrival of Russian troops on their lands.

Hike

In his notes, Brigadier Moreau de Braze counted 79,800 in the Russian army before the start of the Prut campaign: 4 infantry divisions (generals Allart, Densberg, Repnin and Weide) with 11,200 soldiers each, 6 separate regiments (including 2 guards and artillerymen) with a total of 18 thousand, 2 cavalry divisions (generals Janus and Renne) 8 thousand dragoons each, a separate dragoon regiment (2 thousand). The staffing number of units is given, which, due to the transitions from Livonia to the Dniester, significantly decreased. The artillery consisted of 60 heavy guns (4-12 pounders) and up to a hundred regimental guns (2-3 pounders) in divisions. The irregular cavalry numbered approximately 10 thousand Cossacks, who were joined by up to 6 thousand Moldovans.

The route of the Russian troops was a line from Kyiv through the Soroki fortress (on the Dniester) to Moldavian Iasi through the territory of friendly Poland (part of modern Ukraine) with the crossing of the Prut.

Due to food difficulties, the Russian army concentrated on the Dniester - the border of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth with Moldova - during June 1711. Field Marshal Sheremetev with his cavalry was supposed to cross the Dniester in early June and then rush directly to the Danube to occupy possible crossing points for the Turks, create food stores to supply the main army, and also draw Wallachia into the uprising against the Ottoman Empire. However, the field marshal encountered problems in supplying the cavalry with forage and provisions, did not find sufficient military support locally and remained in Moldova, turning to Iasi.

After crossing the Dniester on June 27, 1711, the main army moved in 2 separate groups: in front were 2 infantry divisions of Generals von Allart and von Densberg with the Cossacks, followed by Peter I with the guards regiments, 2 infantry divisions of Prince Repnin and General Weide, as well as artillery under the command of Lieutenant General Bruce. During the 6-day march from the Dniester to the Prut through waterless places, with sweltering heat during the day and cold nights, many Russian recruits, weakened by lack of food, died from thirst and disease. Soldiers died after reaching for and drinking water; others, unable to withstand the hardships, committed suicide.

On July 1 (New Art.), the Crimean Tatar cavalry attacked Sheremetev’s camp on the eastern bank of the Prut. The Russians lost 280 dragoons killed, but repelled the attack.

On July 3, the divisions of Allart and Densberg approached the Prut opposite Iasi (Iasi is located beyond the Prut), then moved downstream.

On July 6, Peter I with 2 divisions, guards and heavy artillery crossed to the left (western) bank of the Prut, where the Moldavian ruler Dmitry Cantemir joined the king.

On July 7, the divisions of Allart and Densberg linked up with the corps of Commander-in-Chief Sheremetev on the right bank of the Prut. The Russian army was experiencing big problems with food, it was decided to cross to the left bank of the Prut, where they expected to find more food.

On July 11, cavalry and a convoy from Sheremetev’s army began crossing to the left bank of the Prut, while the remaining troops remained on the eastern bank.

On July 12, General Renne with 8 dragoon regiments (5056 people) and 5 thousand Moldovans was sent to the city of Brailov (modern Braila in Romania) on the Danube, where the Turks made significant reserves of forage and provisions.

On July 14, Sheremetev’s entire army crossed to the western bank of the Prut, where troops with Peter I soon approached it. Up to 9 thousand soldiers were left in Iasi and on the Dniester to guard communications and keep the local population calm. After combining all forces, the Russian army moved down the Prut to the Danube. 20 thousand Tatars crossed the Prut by swimming with horses and began to attack the small rear units of the Russians.

On July 18, the Russian vanguard learned that a large Turkish army had begun crossing to the western bank of the Prut near the town of Falchi (modern Falchiu). At 2 o'clock in the afternoon, the Turkish cavalry attacked the vanguard of General Janus (6 thousand dragoons, 32 guns), who, having formed in a square and firing from guns, on foot, completely surrounded by the enemy, slowly retreated to the main army. The Russians were saved by the lack of artillery among the Turks and their weak weapons; many of the Turkish horsemen were armed only with bows. As the sun set, the Turkish cavalry withdrew, allowing the vanguard to join the army in an accelerated night march in the early morning of July 19.

Battle with the Turks. Environment

July 19, 1711

On July 19, the Turkish cavalry surrounded the Russian army, not approaching closer than 200-300 steps. The Russians did not have a clear plan of action. At 2 o'clock in the afternoon they decided to move out to attack the enemy, but the Turkish cavalry pulled back without accepting the battle. The army of Peter I was located in the lowlands along the Prut, all the surrounding hills were occupied by the Turks, who had not yet been approached by artillery.

At the military council, it was decided to retreat at night up the Prut in search of a more advantageous position for defense. At 11 o'clock in the evening, having destroyed the extra wagons, the army moved in the following battle formation: 6 parallel columns (4 infantry divisions, the guard and the dragoon division of Janus), with convoys and artillery in the intervals between the columns. Guards regiments covered the left flank; Repnin's division was moving on the right flank adjacent to the Prut. From dangerous sides, the troops covered themselves from the Turkish cavalry with slingshots, which the soldiers carried in their arms.

The losses of the Russian army in killed and wounded that day amounted to about 800 people.

By this time the army numbered 31,554 infantry and 6,692 cavalry, mostly unhorsed, 53 heavy guns and 69 light 3-pounder guns.

20 July 1711

By the morning of July 20, a gap had formed between the lagging far left guard column and the neighboring Allart division due to the uneven march of the columns over rough terrain. The Turks immediately attacked the convoy, which was left without cover, and before the flank was restored, many convoys and members of officers' families were killed. For several hours the army stood waiting for the restoration of the combat march formation. Due to the delay of the Turkish infantry, the Janissaries with artillery managed to catch up with the Russian army during the day.

At about 5 o'clock in the afternoon, the army rested its extreme right flank on the Prut River and stopped for defense near the town of Stanileşti (Romanian: Stănileşti, Stanileşti; about 75 km south of Iasi). On the opposite eastern steep bank of the Prut, the Tatar cavalry and the Zaporozhye Cossacks allied to them appeared. Light artillery approached the Turks and began shelling Russian positions. At 7 o'clock in the evening there followed an attack by the Janissaries on the location of the Allart and Janus divisions, which were moving forward somewhat due to the terrain conditions. The Turks, repulsed by rifle and cannon fire, lay down behind a small hill. Under the cover of gunpowder smoke, 80 grenadiers pelted them with grenades. The Turks counterattacked, but were stopped by gunfire at the slingshot line.

Polish General Poniatowski, a military adviser to the Turks, personally observed the battle:

Brigadier Moreau de Braze, who was not at all favored in Russian service, nevertheless left the following review of the behavior of Peter I at the critical moment of the battle:

At night the Turks made forays twice, but were repulsed. Russian losses as a result of the battles amounted to 2,680 people (750 killed, 1,200 wounded, 730 prisoners and missing); the Turks lost 7-8 thousand according to the report of the English ambassador in Constantinople and the testimony of brigadier Moro de Braze (the Turks themselves admitted to him the losses).

July 21, 1711

On July 21, the Turks surrounded the Russian army, pressed against the river, with a semicircle of field fortifications and artillery batteries. About 160 guns continuously fired at Russian positions. The Janissaries launched an attack, but were again repulsed with losses. The situation of the Russian army became desperate; there was still ammunition left, but the supply was limited. There was not enough food before, and if the siege dragged on, the troops would soon be in danger of starvation. There was no one to expect help from. In the camp, many officers’ wives cried and howled; Peter I himself at times fell into despair, “ ran back and forth in the camp, beat his chest and could not utter a word».

At the morning military council, Peter I and his generals decided to offer peace to the Turkish Sultan; in case of refusal, burn the convoy and break through " not to the stomach, but to death, not showing mercy to anyone and not asking for mercy from anyone" A trumpeter was sent to the Turks with a peace proposal. Vizier Baltaci Mehmed Pasha, without responding to the Russian proposal, ordered the Janissaries to resume attacks. However, they, having suffered great losses on this and the previous day, became agitated and began to murmur that the Sultan wanted peace, and the vizier, against his will, was sending the Janissaries to slaughter.

Sheremetev sent the vizier a second letter, which, in addition to a repeated proposal for peace, contained a threat to go into a decisive battle in a few hours if there was no response. The vizier, having discussed the situation with his military leaders, agreed to conclude a truce for 48 hours and enter into negotiations.

Vice-Chancellor Shafirov, endowed with broad powers, was appointed to the Turks from the besieged army with translators and assistants. Negotiations have begun.

Conclusion of the Prut Peace Treaty

The hopeless situation of the Russian army can be judged by the conditions to which Peter I agreed, and which he outlined to Shafirov in the instructions:

- Give Azov and all previously conquered cities on their lands to the Turks.

- Give the Swedes Livonia and other lands, except Ingria (where St. Petersburg was built). Give Pskov as compensation for Ingria.

- Agree to Leshchinsky, the protege of the Swedes, as the Polish king.

These conditions coincided with those put forward by the Sultan when declaring war on Russia. 150 thousand rubles were allocated from the treasury to bribe the vizier; smaller amounts were intended for other Turkish commanders and even secretaries. According to legend, Peter's wife Ekaterina Alekseevna donated all her jewelry for bribery, but the Danish envoy Just Yul, who was with the Russian army after it left the encirclement, does not report such an act of Catherine, but says that the queen distributed her jewelry to save the officers and then, after peace was concluded, she gathered them back.

On July 22, Shafirov returned from the Turkish camp with peace terms. They turned out to be much lighter than those that Peter was ready for:

- Return of Azov to the Turks in its previous state.

- The devastation of Taganrog and other cities in the lands conquered by the Russians around the Sea of Azov.

- Refusal to interfere in Polish and Cossack (Zaporozhye) affairs.

- Free passage of the Swedish king to Sweden and a number of non-essential conditions for merchants. Until the terms of the agreement were fulfilled, Shafirov and the son of Field Marshal Sheremetev were to remain in Turkey as hostages.

On July 23, the peace treaty was sealed, and already at 6 o’clock in the evening the Russian army, in battle order, with banners flying and drums beating, set out for Iasi. The Turks even allocated their cavalry to protect the Russian army from the predatory raids of the Tatars. Charles XII, having learned about the start of negotiations, but not yet knowing about the conditions of the parties, immediately set off from Bendery to the Prut and on July 24 in the afternoon arrived at the Turkish camp, where he demanded to terminate the treaty and give him an army with which he would defeat the Russians. The Grand Vizier refused, saying:

On July 25, the Russian cavalry corps of General Renne with the attached Moldavian cavalry, not yet knowing about the truce, captured Brailov, which had to be abandoned after 2 days.

On August 13, 1711, the Russian army, leaving Moldova, crossed the Dniester in Mogilev, ending the Prut campaign. According to the recollection of the Dane Rasmus Erebo (secretary of Yu. Yulya) about Russian troops on the approach to the Dniester:

The vizier was never able to receive the bribe promised to him by Peter. On the night of July 26, the money was brought to the Turkish camp, but the vizier did not accept it, fearing his ally, the Crimean Khan. Then he was afraid to take them because of the suspicions raised by Charles XII against the vizier. In November 1711, thanks to the intrigues of Charles XII through English and French diplomacy, Vizier Mehmed Pasha was removed by the Sultan and, according to rumors, was soon executed.

Results of the Prut campaign

During his stay in the camp beyond the Dniester in Podolia, Peter I ordered each brigadier to submit a detailed inventory of his brigade, determining its condition on the first day of entry into Moldova and where it was on the day the order was given. The will of the Tsar's Majesty was fulfilled: according to Brigadier Moro de Braze, of the 79,800 people who were present when entering Moldova, there were only 37,515, and the Renne division had not yet joined the army (5 thousand on July 12).

Perhaps the Russian regiments had an initial shortage of personnel, but no more than 8 thousand recruits, for which Peter I reproached the governors in August 1711.

According to Brigadier Moreau de Braze, during the battles of July 18-21, the Russian army lost 4,800 people killed, Major General Widmann. Renne lost about 100 people killed during the capture of Brailov. Thus, more than 37 thousand Russian soldiers deserted, were captured and died, mainly from disease and hunger at the initial stage of the campaign, of which about 5 thousand were killed in battle.

Having failed, according to the Prut Agreement, to expel Charles XII from Bendery, Peter I ordered the suspension of compliance with the requirements of the treaty. In response, Turkey again declared war on Russia at the end of 1712, but hostilities were limited only to diplomatic activity until the conclusion of the Treaty of Adrianople in June 1713, mainly on the terms of the Prut Treaty.

The main result of the unsuccessful Prut campaign was the loss by Russia of access to the Sea of Azov and the recently built southern fleet. Peter wanted to transfer the ships “Goto Predestination”, “Lastka” and “Speech” from the Sea of Azov to the Baltic, but the Turks did not allow them passage through the Bosporus and Dardanelles, after which the ships were sold to the Ottoman Empire.

Azov was again captured by the Russian army 25 years later in June 1736 under Empress Anna Ioannovna.

I. International context of the Prut campaign

1. Background. Azov campaigns and the Peace of Constantinople.

II. Causes and beginning of the Russian-Turkish War of 1710 - 1713.

III. Progress of military operations. Prut campaign of Peter the Great in 1711

1. Preparation of the trip. Allies. Balance of power.

2. Prut campaign.

3. Battle of Stanilesti.

4. Signing of the Prut Peace Treaty.

Conclusion

Prut Campaign. 1711

I. International context of the Prut campaigns.

The Prut campaign of Peter I cannot be considered outside the context of international relations of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, in particular, outside the context of the development of Russian-Turkish relations and the Russian-Turkish war of 1710-1713.

1. Background. Azov campaigns 1695, 1696

Azov campaigns of 1695 and 1696 - Russian military campaigns against the Ottoman Empire; were undertaken by Peter I at the beginning of his reign and ended with the capture of the Turkish fortress of Azov. They can be considered the first significant accomplishment of the young king. These military companies were the first step towards solving one of the main tasks facing Russia at that time - gaining access to the sea.

The choice of the southern direction as the first goal was due at that time to several main reasons:

· the war with the Ottoman Empire seemed an easier task than the conflict with Sweden, which was closing access to the Baltic Sea;

· the capture of Azov would make it possible to secure the southern regions of the country from attacks by the Crimean Tatars;

· Russia's allies in the anti-Turkish coalition (Rzeczpospolita, Austria and Venice) demanded that Peter I begin military action against Turkey.

The first Azov campaign in 1695. It was decided to strike not at the Crimean Tatars, as in Golitsyn’s campaigns, but at the Turkish fortress of Azov. The route was also changed: not through the desert steppes, but along the Volga and Don regions.

In the winter and spring of 1695, transport ships were built on the Don: plows, sea boats and rafts to deliver troops, ammunition, artillery and food from the deployment to Azov. This can be considered the beginning, albeit imperfect for solving military problems at sea, but the first Russian fleet.

In the spring of 1695, the army in 3 groups under the command of Golovin, Gordon and Lefort moved south. During the campaign, Peter combined the duties of the first bombardier and the de facto leader of the entire campaign.

The Russian army recaptured two fortresses from the Turks, and at the end of June besieged Azov (a fortress at the mouth of the Don). Gordon stood opposite the southern side, Lefort to his left, Golovin, with whose detachment the Tsar was also located, to the right. On July 2, troops under the command of Gordon began siege operations. On July 5, they were joined by the corps of Golovin and Lefort. On July 14 and 16, the Russians managed to occupy the towers - two stone towers on both banks of the Don, above Azov, with iron chains stretched between them, which blocked river boats from entering the sea. This was actually the highest success of the campaign. Two assault attempts were made (August 5 and September 25), but the fortress could not be taken. On October 20, the siege was lifted.

Second Azov campaign of 1696. Throughout the winter of 1696, the Russian army prepared for the second campaign. In January, large-scale construction of ships began at the shipyards of Voronezh and Preobrazhenskoye. The galleys built in Preobrazhenskoye were disassembled and delivered to Voronezh, where they were assembled and launched. In addition, engineering specialists were invited from Austria. Over 25 thousand peasants and townspeople were mobilized from the immediate surroundings to build the fleet. 2 large ships, 23 galleys and more than 1,300 plows, barges and small ships were built.

The command of the troops was also reorganized. Lefort was placed at the head of the fleet, and the ground forces were entrusted to Generalissimo Shein.

The highest decree was issued, according to which slaves who joined the army received freedom. The land army doubled in size, reaching 70,000 men. It also included Ukrainian and Don Cossacks and Kalmyk cavalry.

On May 16, Russian troops again besieged Azov. On the 20th, Cossacks in galleys at the mouth of the Don attacked a caravan of Turkish cargo ships. As a result, 2 galleys and 9 small ships were destroyed, and one small ship was captured. On May 27, the fleet entered the Sea of Azov and cut off the fortress from sources of supply by sea. The approaching Turkish military flotilla did not dare to engage in battle.

On June 10 and June 24, the attacks of the Turkish garrison, reinforced by 60,000 Tatars camped south of Azov, across the Kagalnik River, were repulsed.

On July 16, preparatory siege work was completed. On July 17, 1,500 Don and part of the Ukrainian Cossacks arbitrarily broke into the fortress and settled in two bastions. On July 19, after prolonged artillery shelling, the Azov garrison surrendered. On July 20, the Lyutikh fortress, located at the mouth of the northernmost branch of the Don, also surrendered.

Already by July 23, Peter approved the plan for new fortifications in the fortress, which by this time was severely damaged as a result of artillery shelling. Azov did not have a convenient harbor for basing the navy. For this purpose, a more successful place was chosen - Taganrog was founded on July 27, 1696.

The significance of the Azov campaigns. The Azov campaign demonstrated in practice the importance of artillery and navy for warfare. The preparation of the campaigns clearly demonstrated Peter’s organizational and strategic abilities. For the first time, such important qualities as his ability to draw conclusions from failures and gather strength for a second strike appeared.

Despite the success, at the end of the campaign, the incompleteness of the achieved results became obvious: without capturing the Crimea, or at least Kerch, access to the Black Sea was still impossible. To hold Azov it was necessary to strengthen the fleet. It was necessary to continue building the fleet and provide the country with specialists capable of building modern sea vessels.

On October 20, 1696, the Boyar Duma proclaimed “ Marine vessels to be..." This date can be considered the birthday of the Russian regular navy. An extensive shipbuilding program is approved - 52 (later 77) ships; To finance it, new duties are introduced.

The war with Turkey is not over yet, and therefore, in order to better understand the balance of power, find allies in the war against Turkey and confirm the already existing alliance - the Holy League, and finally strengthen the position of Russia, the “Grand Embassy” was organized.

As a result of the Azov campaigns between Russia and Turkey, July 3 (July 14), 1700, a Treaty of Constantinople.

Russia received Azov with the adjacent territory and newly built fortresses (Taganrog, Pavlovsk, Mius) and was freed from the annual payment of tribute to the Crimean Khan. The part of the Dnieper region occupied by Russian troops with small Turkish fortresses, which were subject to immediate destruction, was returned to Turkey. The parties pledged not to build new fortifications in the border strip and not to allow armed raids. Turkey was supposed to release Russian prisoners, and also grant Russia the right to diplomatic representation in Constantinople for on equal footing with other powers. The treaty ensured Turkey's neutrality at the beginning of the Northern War. The agreement concluded for 30 years was observed until November 1710, when the Sultan declared war on Russia.

II . Russian-Turkish War 1710 – 1713 and the place of the Prut campaign in it.

1. Causes and beginning of the war.

The Prut campaign was the most important military event of the Russian-Turkish war of 1710-1713.

After the defeat of the Swedes in the Battle of Poltava in 1709, the Turkish government confirmed a peace treaty with Russia. At the same time, the ruling circles of Turkey sought to take revenge for the losses under the Treaty of Constantinople of 1700 and move the border with Russia further from the Black Sea.

During the siege of Poltava in 1709, Charles XII was wounded in the leg during a night patrol. Inflammation has begun. The king handed over his leadership to Field Marshal Renschild. But, although he himself was carried on a stretcher, Charles XII tried to command the battle. A cannonball smashed the stretcher, the king was put on a horse and hastily carried away to the camp. Bleeding began. While the wound was being bandaged, news arrived that the battle was over, and most of the officers and soldiers surrendered.