Well, the last post about England, Upper class or British Nobility.

By the way, do you know that in English there is no equivalent of the word "nobility"? Because there is no such social phenomenon. Nobility & Aristocracy do not mean nobility in the Russian sense, but mean "aristocracy", which is not at all the same thing. Approximately 100 families belonged to the aristocracy in Russia, such as the Yusupovs and the Golitsyns. Most of them were descendants of the boyars who had served under Ivan the Terrible.

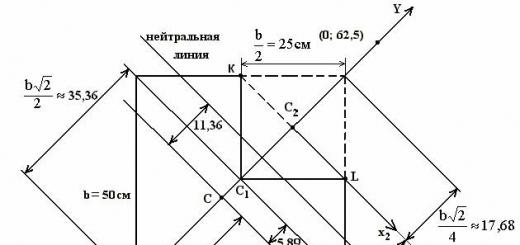

But in addition to the aristocracy in Russia there were hundreds of thousands of ordinary nobles, including small estates, most of whom lived only slightly better than their serfs and were just as dark. This happened because the titles were continuously blurred through the generations. In England, however, there was a majorat, in which only the eldest son inherited the title, and all other children received a title one lower. For example, the eldest son of Duke became Duke, and the rest became Marquesses. In turn, the younger children of Marquess were Earls, and since there were only six or seven titles, they very quickly disappeared altogether. Therefore, the aristocracy remained small and was a real nobility. Actually for this, the system of majorata was introduced.

First World War dealt a heavy blow to the English aristocracy. First, a lot of men from this class died. Secondly, conditions have changed and those who served the estates went to the front or to production. Those who remained demanded such payment that most of the large estates could not support them and could not exist without them. The last straw was death duties - an inheritance tax introduced in 1945, which finished off most of the noble families.

Therefore, today in England there are very few, a few, estates, and almost all of them are open to visitors in order to earn money and avoid taxes. But the titles survived and the culture of the British aristocracy remained. One of the women from this layer is Samantha Cameron, a direct descendant of Charles II. Diana was also from a very ancient and noble family of Spencers, who were considered more noble royal family.

Diana was generally a bright representative of the Upper class. She did not even finish the 8th grade of the school, because she failed her final exams twice. This is quite typical for the British aristocracy, education among them has never been considered a great advantage, and not everyone has the ability to get it. In England there is a whole class of schools, usually boarding, where the academic requirements are noticeably lower than in good schools, but which are nonetheless very difficult to access from another class. The emphasis there is on sports and team games. Graduates of these schools also often do not go to universities, although now this is gradually changing.

Outwardly, women here are similar to women, but more casual and loving extravagant things. They think it's too cool to care too much how they look. Extravagance is considered a sign of this I don't give a damn attitude to appearance. They may be wearing wild-colored trousers, or a sweater torn at the elbows, or a coat embroidered with crocodiles. But those who work try not to stand out, there are no crocodiles here. The rest of the aesthetic in this class differs little from the Upper Middle Class, no lips like a carp, no fake tan, no sparkles.

In the comments to previous articles about England, I was asked a lot about foreigners living here. Upper Class is the only class where foreigners (or representatives of other groups) cannot enter as their own (yes, and Natalia Vodianova too). You cannot marry into this class, you have to be born into it. Therefore, Kate Middleton does not belong to him, but her children will.

Foreigners coming to England, for all intents and purposes, fall into the class to which they fit their education, work, culture and income. Benefit workers in the Underclass, blue-collar workers in the Working class, mid-level professionals in the Middle class, big business, bankers and oligarchs in the Upper Middle.

This is where the series about England ends, and thank God, how tired I am of it.

England was a multicultural country long before recent history, and the aristocracy often took second wives in their colonies. For example, studies show that in the late 19th century, a third of the officials of the East India Company left their goods to Indian wives and their Anglo-Indian children. But such a misalliance, for an aristocrat, heir to a peer, to marry a black Nigerian woman on the territory of England itself, happened for the first time in 2013. The first black marquis of Great Britain, Viscountess Weymouth, is called Emma Tinn (nee McQuiston). She is the daughter of a Nigerian oil tycoon, ex-model, food blogger and aspiring culinary TV presenter, and mother of a young son. When her husband Kevlin, Viscount Weymouth, heir to Longleat Manor, inherits his father's title, Emma will become Lady Bath.

In fact, Emma is only half Nigerian.

Emma's father's name is Ladi Jadesimi. He is the son of an Anglican clergyman. In 1966 he graduated from Oxford University. Held positions of directors of large companies in Nigeria. And in the 90s he began to invest in the Nigerian oil industry. On the this moment he is the Executive Director of Lagos Deep Offshore Logistics Base, known as LADOL. Ladi Jadesimi is one of the richest people in Nigeria. With ex-wife Alero (Alero) they have four children.

Emma's mother, Eileen Patience Pike (as she was called at birth), was born in Brighton. Her father was a sailor. At 17, she worked as a hairdresser in Weymouth (a city in Dorset) and jumped out to marry Ian McQuiston, a 25-year-old sales representative. Six months later, the couple moved to Hampshire, where Eileen gave birth to a son, Jan, and later a daughter, Samantha. How and why Eileen's marriage fell apart is unknown, but at some point, Eileen decided to change her life. Eileen Patience disappeared and Suzanne Louise was born. In her youth, Emma's mother was very beautiful, and the name Susanna Louise suited her better. Susanna Louise surfaced in London.

By the early 80s, Suzanne Louise had become a bohemian party girl. She moved among wealthy Londoners and exotic foreigners, Iraqis, Nigerians and other publics. They gathered in each other's houses, drank and discussed art, poetry and other matters of high matter.

Susanna, Emma's mom now

Suzanne went to parties with her daughter Samantha. According to the recollections of those around her, Suzanne was stunningly beautiful, and she dressed stylishly and provocatively. Loved to come in a short leather skirt to show off her beautiful legs. Most women did not approve of her bringing a child with her, and besides, she dressed the girl in a very old-fashioned way.

At one of these parties, Suzanne met a wealthy Nigerian Ladi Jadesimi. They broke out a stormy, but short-term romance. Emma was born from this novel. At the time, Ladi is said to have been a likeable, charming man, quiet and thoughtful, but his Achilles' heel was women, and blondes at that. Therefore, it is not surprising that he fell for Susanna. He was still married at the time (he later divorced, but remained on good terms with his wife).

Emma's parents at their daughter's wedding

Emma was born in 1989 at a hospital in Paddington.

On her birth certificate, Suzanne and Lady were given the same address in Kensington as their permanent residence. Ladi also moved his residence closer to Susanna's house (which he rented for her) in order to be able to visit her more often. It is not known how long their relationship lasted, but Suzanne speaks of Ladi as "her good friend and good man and thanks him for giving her Emma.

Emma's older brother, Jan (who, by family tradition, changed his name to Ian), married at 27 the 30-year-old Lady Sylvia Thynn, Kevlin's aunt, whom Emma herself later married. Emma was then 4 years old, she was a bridesmaid, and then for the first time she saw Kevlin. She later saw him at family reunions.

Emma lived in London with her mother and sister Samantha in a house in Belgravia that Samantha had bought with money left to her by multi-millionaire Australian construction tycoon John Roberts, with whom she had a long-term love relationship. Emma studied art history at a London college, dreamed of being an actress, but she did not turn out to be a movie star (she was "almost chosen" for a role in the Game of Thrones), and she switched to cooking.

Emma's modeling career was also not very successful; in the modeling business, too much has to be sacrificed. But Emma's portfolio is good.

Although being the mistress of Longleat House is much better, and photo shoots are no worse

Of course, Emma can be considered a narcissistic silly girl who constantly posts photos of herself, her beloved, either on Twitter or on Instagram, and rejoices, like a little one, in publications about herself in glossy magazines, but let the one who has Instagram throw a stone at her first, Facebook or LJ just see others.

The journalist who borrowed from Emma great interview for a women's column, says about her like this: Emma is spontaneous and exotic, like a bird of paradise. As she twirled in her wide skirt in the middle of the room, I thought that I understood why Kevin had married her. If this cold stone house, with dark old corridors with guide dog ads on the walls, was mine, and with these parents, I'd cling to Emma's legs like a toddler.

Kevlin comes from an unusual, extravagant, aristocratic family.

Cevlin's father, Alexander George Tynn, 7th Marquess of Bath, was born in London but grew up and still lives on his estate, Longleat, a huge Elizabethan mansion. Graduated, as usual, Eton and Oxford. At Oxford, he was President of the Bullingdon Club, holds the rank of Lieutenant of the Life Guards, traveled the world, was one of the founders of the Wessex Regional Party, was on the side of elections to the European Parliament. When, after the death of his father, he inherited his title, he sat in the House of Lords from the Liberal Democrats.

In 1969 he married Anna Garmaty, known as Anna Gael, a Hungarian by birth. They have two children: Lady Lenka and Kevlin Thynn, Viscount Weymouth.

In 1976, the Marquess of Bath changed his family name from Thynne to Thynn. He wanted his last name to rhyme with pin instead of pine.

The Marquis of Bath is known for his extravagant, flamboyant clothing, which he began wearing as early as 1950 as an art student in Paris.

As an artist, the Marquis of Bath is very prolific. Especially famous are his erotic frescoes from the Kamasutra. Because of these frescoes, he started a real war with his own son. Before his wedding, Kevlin destroyed several erotic murals in his wing of the house. This father cannot forgive his son until now. Because of these frescoes, he did not go to his son's wedding either.

The Marquis of Bath is also known for his love affairs. He openly had sexual relations with over seventy women during his marriage. These women he settled in cottages and called them wifelets. These "concubines" are another headache for his son, he gradually evicts them.

About her father-in-law, Emma says this: "He was looking for harmony, which for him was personified by women, free love and children. This is a fairly common position for those whose youth fell on the 60s of the last century."

Kevlin's mother, Anna Gael, was born in Budapest. During the war, as a refugee, she ended up in Paris, where she met Alexander Tinn.

Traveled with him throughout South America for a year. Anna wanted to become an actress, and even got several roles in French TV shows. From time to time she visited Alexander on his estate, but she married a French television director. Even married, Anna continued to visit Alexander. Her career as an actress did not work out for her, and she divorced her husband (and why is this goat needed if she cannot make a TV star out of her wife?). Anna eventually became pregnant by Alexander and married him.

Alexander and Anna at Longleat Manor

Until 1970, Anna tried to make a career as an actress, but in the end, she gave up all attempts and switched to journalism. She was a good journalist. Covering conflicts in Vietnam South Africa and Northern Ireland. She wrote two novels published in France. She gave birth to two children: son Kevlin, heir to the title, and daughter Lenka, who is very much appreciated in the world of British fashion.

Because of Emma, Anna began to disagree with her son.

After Kevlin informed his mother about his upcoming marriage, Anna told him: are you sure you want to destroy 400 years of our bloodline? Kevlin tried to ignore his mother's words, but she insisted, so he crossed her off the list of invitees to his wedding and forbade her to let her in if she showed up uninvited. Who would say, but not a former unsuccessful actress who starred in only a couple of erotic films depicting lesbian love, and most of the time lived in France with her lover.

A mother who had the nickname "Naked Lady Longleat" should have been more careful in criticizing her future daughter-in-law in front of her son. Now that Old Lady Weymouth's lover has died, she visits her son's house more often (the father handed over management of the estate to his son in 2010). According to Emma, Anna ignores her. When they meet, Emma greets her mother-in-law first, to which the mother-in-law usually replies: oh, it's you, I didn't notice you. The grandmother's relationship with her grandson is also only formal.

It was in such a family that Kevlin Henry Laszlo Thynn, Viscount Weymouth, was born. His eccentric father, although he himself graduated from Eton and Oxford, sent his son to study in a simple rural school, and Kevlin earned his pocket money by cleaning toilets in the Oscar nightclub on the estate.

At the age of 16, Kevlin convinced his father to send him to the Bedales boarding school, famous for its liberal views. But at the age of 17, he was expelled from this school for smoking marijuana. Kevlin passed his exams at another school and went to study economics and philosophy at University College London.

In 1996, when Kevlin was 21, he was born again. While traveling to Delhi with their fiancée Jane Kirby and a business partner, they find themselves at the site of a terrorist attack. The hotel where they lived was blown up. Kevlin himself was not injured, he even helped carry the wounded, but his fiancee and business partner died.

For almost a year, Kevlin came to his senses, but when he came to, he became a different person. He started his career in investment banking and created Wombats, an international hostel chain.

In 2009, Kevlin became chairman of Longleat Enterprises, which maintains and operates the Longleat House and Safari Park on the Longleat family estate, as well as commercial activities in Cheddar Gorge, in the Mendip Hills in Somerset. Together with the executive director, Kevlin developed new attractions in the Safari Park: "Kingdom of the Jungle", "Temple of the Monkeys", "Skyhunters".

In order to modernize the mansion and create new programs for the safari park, Kevlin had to raise the rent on the estate, which outraged the residents. Kevlin had to resolve this situation by paying, for example, heating bills for local pensioners.

Kevin and his father are trustees of the Longleat Charitable Foundation.

Outwardly, Kevlin is a typical "west country" aristocrat: unpretentious, polite, awkward.

Emma and Kevlin met again at London nightclub Soho House in 2011. According to others, Emma drove Kevlin crazy.

In November, Annabelle Kevlin proposed to her at a nightclub.

Emma remembers it like this: we were at a party, and in the middle of the night he proposed to me. I made him say it over and over until he drowned in my kiss.

The couple announced their engagement in 2012 and got married in 2013.

In 2014, Emma gave birth to a son, Longleat's next heir. The child was given to Emma not just. Emma, who had never been ill before, was diagnosed with a disorder of the pituitary gland during pregnancy. She started having terrible headaches. She lay flat on the bed, not moving, and it seemed to her that her brain was bleeding. The pressure skyrocketed. At the 37th week of pregnancy, she was urgently hospitalized and decided to perform a caesarean section. The child was born healthy.

During pregnancy, Emma gained weight, but now she has regained her former shape. She enjoys being the mother and mistress of Longleat. Emma has converted an old kitchen into a gift shop, display kitchen and grocery store with a large selection of Longleat products. She checks all the recipes herself, hoping to restore the old vegetable garden and start making Longleat's own pasta sauces again. When asked why they live here, given the differences in the family, Emma replies: Kevlin grew up here. He must be here. His office is also here. Kevlin works very my - he has to do it. Without permanent repairs, Longleat will sink into Wiltshire soil.

Emma believes that with the help of her beauty, delicious food and entertainment, she can make her husband happy. This is probably naive, but if Emma believes in this and her husband is truly dear to her, let her be lucky.

I've wanted to make this post for a long time. It's not that I'm a fan of the Queen of England, or England, or Kate Middleton (Prince Harry is an exception, of course), I just heard more than once that classism is strong in England, the aristocrats are super closed, this and that, that's interesting - how is this possible in our easy, fast 21st century? And then I came across a book by Julian Fellows "Snobs".

Among his works - Downton Abbey, for example. The novel "Snobs" is written on behalf of an aristocratic actor, so it can be assumed that at least the author associates himself with the hero. Whether there was actually a story described in the book or not - it doesn’t matter, in my opinion, the main thing is that the theme of class and closeness of the English upper classes is well disclosed there.

Briefly content: there is a family of the Earls of Brotton (mother is an iron lady with nowhere blue blood, a mattress is a father, about the same mattress, but a noble and kind son, a sober-minded daughter who is married to some impudent broker, whom maman married in spite of ). There is a family of Laviere - representatives of the top of the Middle Class: Mom, dreaming to issue a daughter marrying an aristocrat and a little turned on to get into the highest scope and chase tea with noble ladies, dad-pofigist, and daughter - all in Pope. The author knows both. The main storyline is how a mattress son fell in love with a daughter who doesn't give a damn and what came of it. It turned out interesting, read at your leisure, and I'll just copy a few fragments of the book (Friday, the reports started, it's time for a post about the English aristocracy :))

So, about the Lavery family (many letters here)

"The Laveries were not rich, but they were not poor, and since they had only one child, they never had to save much. Edith was sent to a fashionable Kindergarten, and then to Benenden (“No, the princess has absolutely nothing to do with it. We just went through the options and decided that this is the most inspiring place”). Mrs. Lavery would have liked her daughter to continue her studies at the university, but when Edith's examination results weren't good enough to secure her admission to one of the institutions they wanted to send her to, Mrs. Lavery was not disappointed. She had another ambitious plan - to bring her daughter into the world.

Stella Lavery herself did not have a chance to debut. And this she was ashamed to the core. She tried to hide it, often recalling with a laugh how fun she was in her youth, and if she was insistently asked for details, she could say with a sigh that her father's affairs were greatly shaken in the thirties (thus linking herself to the collapse on Wall Street). street, images of Scott Fitzgerald and The Great Gatsby). Or, misrepresenting the dates, she blamed the war for everything. But the reality, as Mrs. Lavery had to admit to herself in the back of her mind, was that in the socially less flexible world of the fifties, the boundaries between those who were members of the Society and those who were not were much clearer. Stella Lavery's family did not belong to the Society……

.... Thanks to the fact that by the nineties of the twentieth century, presentation to the court (which could have been problematic) had already become a thing of the past, Mrs. Lavery had only to convince her husband and daughter that both time and money would be well spent.

It didn't take long to convince them. Edith had no clear plans in life, and the idea of postponing the moment of decision for a year - a year filled with receptions and parties - seemed to her wonderful. And Mr. Lavery liked to represent his wife and daughter among the London beau monde, and he was willing to pay for it. Mrs. Lavery's carefully nurtured connections were enough for Edith to be on the list of invitees to Peter Townend's tea parties, and the girl's appearance allowed her to become one of the models at the Berkeley fashion show. Further, the wind was already favorable. Mrs. Lavery dined with other mothers of debutantes, chose dresses for her daughter for country balls, and generally had a great time. Edith had a good time too.

But Mrs. Lavery was upset that when the Season came to an end, when the last winter charity ball ended and the cuttings from Tatler were pasted into the album along with the invitations, nothing seemed to have changed. During this year, Edith was hosted by the daughters of several peers - including one duke, which made Stella particularly breathless - and all these girls attended a cocktail party that Edith herself gave in Claridge (one of the happiest evenings in the life of Mrs. Lavery), but those friends who stayed with Edith when the music died down and the dancing ended were exactly like the girls who came to visit her from school - the daughters of successful businessmen, representatives of the upper middle class. …..

Edith saw her mother's disappointment, but although she was not, as we shall see, beyond the charms of wealth and nobility, she did not really understand how she could live up to expectations and make really close friendship with the daughters of Noble Houses. They had all known each other almost from birth, and indeed she knew that it would be very difficult to accept them according to their tastes in an apartment in Elm Park Gardens. She kept acquaintance with all the girls who debuted with her, and when they met somewhere by chance, they nodded affably to each other, but life returned to its previous track, and everything became almost the same as immediately after school ... "

About communication.

(photos are random, but all of them are representatives of the aristocracy)

“Jane, Henry, good evening,” Charles stood up and nodded towards Edith. “Do you know Edith Lavery? Henry and Jane Cumnor.

Jane casually and almost imperceptibly shook hands with Edith, then turned back to Charles and, sitting down, poured herself some wine.

- I'm dying of thirst. How are you doing? What happened to you at Ascot?

- Nothing happened. I was there.

I thought we were all having lunch together on Thursday. With Witherby and his wife. We were looking for you, looking for, but then we gave up. Camilla was terribly disappointed. She smiled conspiratorially at Edith, as if inviting her to laugh at the joke. In fact, of course, she deliberately emphasized that Edith was a stranger here and had no idea what she was talking about ... Edith smiled back. She was not new to this strong need of the upper classes to demonstrate that they knew each other and regularly did the same things with the same people.

"She had that curious confidence of the English upper classes, that whatever the situation, and however much others went out of their way for her sake, even when, as now, strangers at all offer their hospitality to her, it is still she, lady Caroline Chase, doing them a favor. It is unthinkable for such people that they do not necessarily do honor to the house they enter. And as a result, because of this belief that she benefited the hosts by her mere presence, Caroline never tried to lead pleasant with anyone except people of her circle, and although she was a smart woman, she could turn out to be a deadly boring guest. But neither she nor many other people very similar to her even suspected this.

Mrs. Frank approached Caroline and began to ask her about mutual acquaintances. She seemed to be unhappy that she was not invited to Charles's wedding, because many of her questions ended with the words "they must have been at the reception", and Caroline again and again they had to admit that yes, they were. Names circled across the deep azure expanse of the Mediterranean sky as they moved from terrace to terrace. Did they see Esterhazy and his wife? Polignacs? Devonshires? Metternicks? Frescobaldis? Names torn from historical treatises, names that Edith remembered in her history lessons about Spain, the reign of Philip II, or the Risogrimmento, or the French Revolution, or the Congress of Vienna. And yet here they are, devoid of any real meaning. The stakes were high, and Edith noticed with some amazement and pleasure that Jane Cumnor and Eric were a few paces behind and walking beside Tina, very apparently trying to avoid that feeling of being left behind, which they so loved to cause in others. Caroline and Charles were unperturbed. It was clear that, despite all the millions of Franks, the brother and sister could respond with a name to every name, and even add a couple on top. "

About the difficulties of choice.

“It was time to face the truth. Edith would not like his mother. He knew this for sure. If Edith were introduced to his mother as the wife of one of his friends, the girl might even like her - if Lady Uckfield noticed her at all, - but as Charles' girlfriend, she will not be welcomed with open arms."

"And of course, as soon as she said:" I am so glad to see our dear Edith's friends with us, "I realized that she did not like the future daughter-in-law. In general," do not like "is not quite the right expression. She was amazed that her own son marries a girl whom she not only did not know - whom she had not even heard of. She could not believe that this girl's friends were not the children of her own friends. It is amazing that Edith even got into their house. How did this happen ?"

About property.

“These people may have a house in Chester Square and a small cottage in Derbyshire, but you can be sure that “home” is where grass grows under the windows. And if such a shelter does not exist in principle, then they will clearly give you will understand that for their well-being it is vital for them to escape from the city as often as possible to stay with their country friends, away from the smoke and dusty pavements, meaning that even though they have to wander all their lives between stone walls or sit at a table in the City, in they will forever remain villagers to their hearts. It is rare to find an aristocrat who prefers London - at least one who would honestly admit it.

"Representatives of the upper classes of English society have a deep subconscious need to read their difference from others in the things around them. For them, there is nothing more depressing (and less convincing) than trying to claim a certain social position or status, a certain origin or upbringing without the necessary props They would never dream of decorating a one-room apartment in Putney without marking it with a random watercolor portrait of their grandmother in a crinoline, a couple of decent antiques, and some relic from their privileged childhood. a sign system that indicates to the visitor what place the owner assigns to himself in the class hierarchy.But more than anything else, the real distinguishing mark, the litmus test for them, is whether the family managed to maintain their family home and estates.Or an acceptable part of them.You can hear how some nobleman explains the arrival to an American that wealth does not play an important role in modern England, that people can remain in society without a penny in their pocket, that “lands these days are more a responsibility than profit”, but deep down he does not believes. He knows that the family that has lost everything but the title, all these duchesses with their houses near Cheney Walk, viscounts with their run-down apartments on Embery Street, hang there at least three layers of portraits and images of the family estate ("There is something now something like a farmer's college"), all the same, all these people are de-classes for their tribe. Of course, this awareness of the need for a material foundation for social position remains as unspoken as the Masonic ritual.

Oh, and on topic. Excerpts from an article about studying at Oxford called "Sex, weed and class hatred at Oxford"

"Tradition teaches that pith helmets should be equipped not just with bright heads, but with bright aristocratic heads of the Anglican faith. Everything else is nothing more than concessions to the realities of the degraded outside world, which gradually imposed on Oxford Catholics, nouveau riches, offspring of colonial kings, women, atheists, colored , middle and even working classes. But in essence, the tradition is preserved: the entire system of education and pastime is still entirely adjusted to the nobility, which today makes up about 50% of students. These are graduates of elite private schools such as Eton and Westminster, which in England - from strength 10% of all educational institutions. A hundred years ago, until England lost its imperial-aristocratic hegemony, these schools supplied 100% Oxford students. But the empire still strikes back. The 50% imposed from outside - all these "talented black mathematicians from dysfunctional families" - are equally spinning in the incubator for three years, finally proudly photographed with a diploma and happy parents, after which they return to the same environment from which they left three years earlier. They join the ranks of teachers, petty civil servants, office workers. They move back to their parents in a Welsh village with an unpronounceable name. Stay for graduate school. And their recent dorm roommates and Facebook friends go to long-distance navigation along the corridors of power. They will never cross again. "

"The Mikhalkovs are not a dynasty; a dynasty is when it turns out that the medieval dining room in which we dine was built in the sixteenth century with the money of the ancestor of my classmate, that the ancestor had the same surname, which he did not fail to carve on the wall of the dining room and that on those rare occasions when my classmate dine in the canteen rather than in the restaurant, he prefers to sit under this sign. "

"The distinctive features of the upper caste are countless. First, it is a bulletproof self-confidence (rather a calm consciousness of one's own superiority than boorish self-confidence - this one comes out only during drinking parties). Secondly, it is an instantly recognizable speech: the so-called RP- pronunciation (popularly - Queen's English), intonation and marker words, which in themselves emphasize the speaker's belonging to the elite. appearance. Like a Russian tourist in Europe, a graduate of a British private school in Oxford can be unmistakably guessed from the back. Guessed by the seemingly careless and casual, but in fact carefully tousled hair, athletic physique (rugby plus rowing) and clothes ranging from the overly obvious Abercrombie & Fitch / Jack Wills (lowest bar) to tailored pink trousers from Oxford tailor with Turl Street with a yellow jacket, blue socks and an antique cane (highest bar).

Naive students from mere mortals at first still try to make acquaintances with the top and even for a whole month "for show" they go in for rowing, but, having stumbled upon a wall out of polite indifference and realizing the futility of their efforts, they quickly stop trying to enter the circle of the elite. In the presence of the upper caste, they begin to speak out of place, stutter, feeling the fading of their speech, and shift from foot to foot in sneakers from Next for 20 pounds. "

"The white bone does not despise middle class She just doesn't notice him. The proletariat and declassed elements are at least as interesting as nineteenth-century English travelers were interested in the anomalous length of clitoris in African tribal women. For this purely Victorian curiosity and its grotesque objects, there is even a suitable word, reminiscent of a cabinet of curiosities - curiosity (the same one that Dickens has in The Old Curiosity Shop). Everything that cannot be drunk and demonstrated to your refined friends on a summer evening on the veranda of the family estate, accompanied by a sparkling story, is of no value to the elite. Either bewitching beauty or pathological ugliness is interesting; either profligate wealth or monstrous poverty. I am not quoting Wilde, this is a literal retelling of a drunken but very symptomatic conversation of freshmen during Baron N.'s celebration of his coming of age in a five-star hotel.

It's a bit too much, sorry :)

P.S. I don't envy Duchess Katherine.

Property status of British aristocrats

Huge wealth was concentrated in the hands of the upper stratum of the English aristocracy, incomparable with what the continental nobility had. In 1883 the income from land, city property and industrial enterprises is over £75,000. Art. had 29 aristocrats. The first among them was the 4th Earl Grosvenor, who in 1874 received the title of Duke of Westminster, whose income was calculated in the range of 290-325 thousand pounds. Art., and on the eve of the First World War - 1 million pounds. Art. The largest source of income for the aristocracy was land ownership. According to the land census, first conducted in England in 1873, out of about a million owners, only 4217 aristocrats and gentry owned almost 59% of the land plots. Out of this nationally small number stood out an ultra-narrow circle of 363 landowners, each of whom had 10,000 acres of land: together they disposed of 25% of all land in England. They were joined by approximately 1,000 landowners with estates ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 acres. They concentrated more than 20% of the land. Neither the titled aristocrats nor the gentry were engaged in agriculture themselves, giving land to tenant farmers. The owner of the land received a rent of 3-4%. This made it possible to have a stable and high income. In the 1870s income in the form of land rent (excluding income from city property) over £50,000. Art. received 76 owners, more than 10 thousand f. Art. - 866 landowners, over 3 thousand pounds. Art. - 2500 baronets and gentry. But already in the last third of the XIX century. the bulk of the higher and middle local nobility painfully felt the consequences of the agrarian crisis and the fall in rents. In England, wheat prices in 1894-1898. on average amounted to half the level of 1867-1871. Between 1873 and 1894 land values in Norfolk have halved and rents have fallen by 43%; as a consequence, two-thirds of the gentry of that county sold their estates. The decline in cash receipts from the land affected the super-rich titled nobility to a lesser extent, the majority of whose income was formed from non-agricultural sources, primarily urban real estate.The English aristocracy, in addition to vast rural estates, inherited large tracts of land and mansions in the cities from past generations. Only a few families owned most of the land within London. In 1828 the leased properties of London gave the Duke of Bedford £66,000. Art. per year, and in 1880 - almost 137 thousand pounds. Art. Income from Marylebond, which belonged to the Duke of Portland in London, rose from more than £34,000. Art. in 1828 to 100 thousand pounds. Art. in 1872 the Earl of Derby, the Earl of Sefton and the Marquess of Salisbury owned the land of Liverpool. The owner of almost all the land of the city of Huddersfield was Ramsden. The owners of urban land leased it to tenants, in many cases they themselves created urban infrastructure, which led to the formation of new cities. The 2nd Marquess of Bute, to his advantage, built docks on his land, around which Cardiff began to grow; Bute's revenues rose from £3,500. Art. in 1850 to 28.3 thousand pounds. Art. in 1894 the 7th Duke of Devonshire turned the village of Barrow into Big City and invested in the development of local deposits of iron ore, the construction of a steel mill, railway, docks, and jute production over 2 million lbs. Art. By 1896, aristocrats built a number of seaside resorts on their own lands: Eastbourne, Southport, Bournemouth, etc.

Another source of enrichment after agriculture and the exploitation of urban real estate was industry. In the 19th century the English aristocracy did not invest in metallurgical and textile industry and invested very little in the construction of communication lines. Aristocrats were afraid of losing their fortune due to unsuccessful investments, believing that it was unacceptable to risk what was created by generations of ancestors. But there were also reverse cases: 167 English peers were directors of various companies. Ownership of land, the depths of which often contained minerals, encouraged the development of mining. The main place in it was occupied by the extraction of coal, to a lesser extent - copper, tin and lead ores. The Lamten, Earls of Durham, in 1856 made a profit of more than £84,000 from their mines. Art., and in 1873 - in 380 thousand pounds. Art. Since the mine owners of noble origin were close and understandable to the experience of lease relations in agriculture, in most cases, the mines were leased to bourgeois entrepreneurs. This, firstly, ensured a stable income, and secondly, saved from the risk of inefficient investment in production, which is inevitable in personal management.

Lifestyle of British aristocrats

Belonging to the aristocratic high society opened up brilliant prospects. In addition to a career in the highest echelons of power, preference was given to the army and navy. In the generations born between 1800 and 1850, military service elected by 52% younger sons and grandchildren of peers and baronets. The aristocratic nobility preferred to serve in the elite guards regiments. A kind of social filter that protected these regiments from the penetration of officers of a lower social level into them was the amount of income that was supposed to provide the style of behavior and lifestyle accepted in the officer environment: the expenses of officers significantly exceeded their salaries. In 1904, a commission studying the financial situation of British officers came to the conclusion that each officer, in addition to salary, depending on the type of service and the nature of the regiment, should have an income of 400 to 1200 pounds. Art. in year. In the aristocratic officer environment, composure and endurance, personal courage, reckless courage, unconditional obedience to the rules and conventions of high society, and the ability to maintain a reputation in any circumstances were valued. And at the same time, the rich offspring of noble families, as a rule, did not bother to master the military craft, serving in the army, they did not become professionals. This was facilitated by the geopolitical position of the country. England, protected by the seas and a powerful navy from the continental powers, could afford to have a poorly organized army intended only for colonial expeditions. Aristocrats, having served for several years in the atmosphere of an aristocratic club and having waited for an inheritance, left the service in order to use their wealth and high social position in other areas of activity.For this social environment created all possibilities. W. Thackeray in The Book of Snobs sarcastically remarked that the sons of lords from childhood are placed in completely different conditions and make a rapid career, stepping over everyone else, “because this young man is a lord, the university, after two years, gives him a degree, which everyone else gets seven years.” The special position gave rise to the isolation of the privileged world of the aristocracy. The London nobility even settled away from the banking, commercial and industrial areas, the port and railway stations in "their" part of the city. Life in this community was subject to strictly regulated rituals and rules. The high-society code of conduct from generation to generation has shaped the style and lifestyle of a gentleman belonging to the circle of the elite. The aristocracy emphasized its superiority by the strictest observance of “parochialism”: at a gala dinner, the prime minister could be seated below the son of the duke. A whole system has been developed to protect high society from the penetration of outsiders. At the end of the XIX century. the Countess of Warwick believed that “army and naval officers, diplomats and clergymen can be invited to a second breakfast or dinner. The vicar, if he is a gentleman, can be constantly invited to Sunday lunch or dinner. Doctors and lawyers may be invited to garden parties, but never for lunch or dinner. Anyone connected with the arts, the stage, trade or commerce, regardless of the success achieved in these fields, should not be invited into the house at all. The life of aristocratic families was strictly regulated. The future mother of Winston Churchill, Jenny Jerome, spoke about life in the family estate of her husband's family: “When the family was alone in Blenheim, everything happened by the clock. The hours were determined when I had to practice the piano, read, draw, so that I again felt like a schoolgirl. In the morning an hour or two was devoted to reading the newspapers, which was necessary, as the conversation invariably turned to politics at dinner. During the day, visits to neighbors or walks in the garden were made. After dinner, which was a solemn ceremony in strict formal attire, we retired to the so-called Vandyke Hall. One could read or play a game of whist there, but not for money... Everyone glanced furtively at the clock, which sometimes someone dreaming of sleeping would stealthily set a quarter of an hour ahead. No one dared to go to bed before eleven, the sacred hour, when we walked in orderly detachment to the small anteroom, where we lit our candles and, after kissing the duke and duchess at night, dispersed to our rooms. In the conditions of city life, many restrictions also had to be obeyed: a lady could not ride a train without a maid, she could not ride alone in a hired carriage, let alone walk along the street, and it was simply unthinkable for a young unmarried woman to go anywhere herself. . It was all the more impossible to work for remuneration without the risk of arousing the condemnation of society.

Most of the representatives of the aristocracy, who received education and upbringing, sufficient only to successfully marry, aspired to become mistresses of fashionable salons, trendsetters of tastes and manners. Not considering secular conventions burdensome, they sought to fully realize the opportunities offered by high society. The same Jenny, having become Lady Randolph Churchill, “saw her life as an endless series of entertainment: picnics, a regatta at Henley, horse races at Ascot and Goodwood, visits to the cricket and skating club of Princess Alexandra, shooting pigeons in Harlingham ... And also, of course , balls, opera, concerts, at the Albert Hall, theaters, ballet, the new Four Horses Club and numerous royal and non-royal evenings that lasted until five in the morning. At court, in ballrooms and living rooms, women interacted on equal terms with men.

Private life was considered private matter everyone. Morality had extremely wide boundaries, adultery was commonplace. The Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, had a scandalous reputation, he was accused of being an indispensable participant in all "aristocratic riots that are only committed within the metropolis." His prey - and, for the most part, reliable - were the wives of friends and acquaintances. This lifestyle was inherent in many aristocrats and did not cause condemnation: it was believed that the norms of a virtuous married life were necessary for the lower classes and not mandatory for the higher ones. Adultery was viewed condescendingly, but on one condition: it was impossible to allow a public scandal in the form of publications in the press, and even more so a divorce, since this undermined the reputation. As soon as there was a possibility of divorce proceedings, intervened secular society, seeking to keep its stumbled members from the final step, although this was not always possible.

Fenced by a system of rituals and conventions, high society by the beginning of the 20th century. itself was divided into several separate informal groups, whose members were united by a common attitude to the prevailing political and social realities, the nature of entertainment and the way of spending time: card games, hunting, horseback riding, shooting and other sports, amateur performances, small talk and love adventures. The centers of attraction for the male part of the aristocratic society were clubs. They satisfied the most sophisticated whims of the regulars: in one of them silver change was immersed in boiling water to wash off the dirt, in the other, if a member of the club demanded it, change was given only in gold. But with all this, the clubs had luxurious libraries, the best wines, gourmet cuisine, carefully guarded privacy and the opportunity to communicate with the elite and famous members of high society. Women were usually not allowed to enter the clubs, but if someone from the aristocratic society arranged a reception with dancing and dinner in the club, they were invited.

An indicator of a high position in the aristocratic hierarchy was the presence of a country house, in fact a palace with many rooms filled with collections of works of art. AT late XVIII in. to maintain such an estate, it was necessary to have an income of at least 5-6 thousand pounds. Art., and to live "without straining" - 10 thousand. An important place was occupied by the reception of guests in country houses. Departure usually lasted four days: guests arrived on Tuesday and left on Saturday. The expenses for receiving guests reached incredible proportions, especially if members of the royal family were received, since up to 400-500 people came (along with servants). The favorite pastime was cards, gossip and gossip. Country estates kept many racehorses and trained packs of hunting dogs, which cost thousands of pounds to maintain. This made it possible to entertain the hosts and guests with horseback riding. Excitement and hunting rivalry caused horse hunting for foxes and shooting from an ambush at game. In an obituary on the occasion of the death in 1900 of the Duke of Portland, hunting trophies were noted as the most important achievements of this aristocrat: 142,858 pheasants, 97,579 partridges, 56,460 black grouse, 29,858 rabbits and 27,678 hares shot in countless hunts. It is not surprising that with such a lifestyle, there was no time left for really useful things for society and the state.

About how English aristocrats adapt to life in a democracy. The author of the article, Chris Bryant, argues that despite the myth of "noble poverty" and the loss of ancestral homes, the wealth of aristocrats and their influence remains phenomenal.

On January 11 of this year, after a short illness at the age of 77, the third Baron Lyell, Charles, died. He inherited his title and the 10,000-acre estate of Kinnordy at the age of four. After studying at Eton and at the aristocratic Oxford College of Christ Church, Charles spent almost 47 years in the House of Lords. The Baron was able to remain in Parliament even after the 1999 reform, when most hereditary peers were excluded from the House: he became one of 92 elected hereditary peers. According to the new rules, after his death, by-elections were held for the vacant seat, in which 27 hereditary peers took part.

In their statements, most of the candidates focused on career achievements and lists of regalia. But Hugh Crossley, the 45-year-old fourth Baron Somerleyton, emphasized ideology. "I believe that the hereditary peerage must be preserved: this principle fosters a deep sense of duty to the good of the nation," he said.

Crossley is easy to understand: he is the heir to Somerleyton Hall in Suffolk. His ancestor Sir Francis Crossley, a major industrialist, purchased the estate in 1863. With gardens, park labyrinths, bird aviaries, 300-foot (100-meter) colonnades and a marina, he was born and spent his whole life in this luxurious estate of 5,000 acres (2,000 hectares). Of course, hereditary principles are sacred to him.

Regular visits to Parliament seemed to their lordships too tiring.

But judging by the activity in the House of Lords, for most of the 20th century, the aristocracy showed a surprising indifference to the good of the nation. Attendance at the debates was extremely low, although the peers already have a very sparing schedule: the working day began at 3:45 or 4:15 in the afternoon, and work week most often limited to three days. Even during the Second World War, debates rarely drew more than a couple of dozen peers at once, and in post-war years this trend has only worsened. Regular visits to Parliament seemed too tiring for their Lordships, except in situations where their personal interests were at stake or their convictions were hurt. A striking example- when, in 1956, a member of the Commons introduced a bill to abolish the death penalty: the Lords rejected it by a convincing majority of 238 votes to 95.

These days we are accustomed to regard the British aristocracy as a historical curiosity. Under Tony Blair, most hereditary peers were expelled from the House of Lords (there are only 92 of them left instead of 650). It may seem that this indicates a complete loss of influence. But the fact that 92 hereditary peers have remained in Parliament (more than the number of participants in almost all meetings in the last eight decades) is a victory that proves that their influence is still strong. After all, they were able not only to delay, but to prevent further reform of the House of Lords and strengthen their presence in it.

By the 1990s, many aristocrats had lost interest in politics, but for those who nevertheless decided to exercise their parliamentary rights, the House of Lords provided an easy path to power. So, under John Major, several hereditary peers were immediately appointed to important government positions: Viscount Cranborne became chairman of the House of Lords, and among the ministers there were seven earls, four viscounts and five hereditary barons. And even in the administration formed in June 2017 by Theresa May, there is one earl, one viscount and three hereditary barons.

Behind the beautiful façade of the British aristocracy, behind the romantic biographies of some of its representatives, lies a much darker side: centuries of theft, violence and insatiable greed. Historically, the defining feature of the aristocracy was not a noble desire to serve society, but a desperate lust for power. Aristocrats seized land in a variety of ways - expropriated it from monasteries, secured it for their sole use under the pretext of efficiency. They held on to their wealth and strengthened the stability of their social status. They forced to respect themselves, defiantly spending exorbitant funds on palaces and jewelry. They set a strict set of rules for all other members of society, but they themselves lived by very different standards. They believed (and forced others to believe) that the hierarchical social structure with them at the head - the only natural order of things. The slightest doubt in this was regarded as the destruction of spiritual bonds.

Attempts to deprive the aristocrats of this status infuriated and sincerely shocked them. Clinging to their position, they came up with increasingly convincing arguments in defense of their privileges. And when in the end democracy unceremoniously pushed the aristocrats aside, they found new ways to preserve their incredible wealth - no longer pretending to be driven by concern for the public good. So the aristocracy is far from dying out - quite the contrary.

State of descendants royal dynasty Plantagenets in 2001 amounted to 4 billion pounds and 700 thousand acres (300 thousand hectares) of land; 42 representatives of the dynasty until 1999 were members of the House of Lords.

... Whatever they say about noble poverty and the loss of family estates, the personal wealth of British aristocrats remains phenomenal. According to Country Life magazine, a third of British land is still owned by the aristocracy. Despite some changes, the lists of the most powerful noble landowners in 1872 and in 2001 turn out to be remarkably similar. According to some estimates, the fortune of the descendants of the royal Plantagenet dynasty in 2001 was 4 billion pounds and 700 thousand acres (300 thousand hectares) of land; 42 representatives of the dynasty until 1999 were members of the House of Lords. The data for Scotland is even more striking: almost half of the land there is concentrated in the hands of 432 individuals and companies. More than a quarter land plots, whose area is over 5 thousand acres, in Scotland are owned by aristocratic families.

And it's not just about the numbers: many of the landed estates owned by British aristocrats are considered the most valuable and expensive in the world. Thus, the Duke of Westminster, in addition to estates of 96,000, 23,500 and 11,500 acres (40,000, 10,000 and 4,500 hectares) in different parts of the country owns huge land plots in the prestigious London districts of Mayfair and Belgravia. Earl Cadogan owns plots in Cadogan Square, Sloane Street and King's Road, Marquess of Northampton - 260 acres (100 hectares) in Clerkenwell and Canonbury, Baroness Howard de Walden - most of Harley Street and Marylebone High Street. Rents in these parts of London are among the highest in the world. In 1925, the journalist W. B. Northrop published a map: the "aristocratic landownership" octopus spread its tentacles all over London, paralyzing the construction business and sucking the juice out of the inhabitants. Since then, little has changed.

One legal rule, unique to England and Wales, became especially important for noble landowners. It was she who allowed them to build houses for many centuries and sell them on a leasehold basis, and not full ownership. This means that buyers do not acquire the property itself, but only the right to own it for a certain period of time. So even the "owners" of large residential complexes are forced to pay land rent to the real owners, to whom their property returns after the contract expires (and in some areas of London it cannot be more than 35 years). In addition to real estate, the land itself also brings in huge incomes: agricultural areas are constantly growing in price. According to the 2016 ranking of the richest people in Britain, 30 lords are worth £100 million or more each.

... Many aspects of the life of English aristocrats have hardly changed over time. Even those who have ceded their palaces to the National Trust for Historic Interests or other non-profit foundations (with all the associated tax benefits) often continue to live in their ancestral homes. Only now their estates are equipped with modern amenities. Some country palaces such as Chatsworth, Woburn and Longleat live off country tourism, attracting many visitors. Others are still private estates, and noble heirs, as before, annually move from one luxurious residence to another. The Dukes of Buccleuch, for example, use the famous "Pink Palace" Drumlanrig as their main residence, but spend the winter months at the 100-room Bowhill Mansion or the Boughton Estate (the latter includes five villages and a mansion whose halls are decorated with works by Van Dyck, El Greco and Gainsborough). ). When the previous duke made this voyage, he usually took Leonardo da Vinci's Madonna with a Spindle with him - until in 2003 the painting was stolen directly from his family castle.

The habits and hobbies of aristocrats also remained the same. In the 21st century, members of the nobility most often belong to the same clubs as their ancestors. Aristocrats still use U-English instead of non-U English (terms for differences in aristocratic and middle-class vocabulary), saying napkins and vegetables instead of serviettes and greens. They play polo. They are hunting. They love guns, horses and dogs.

Hunters on the estate of the Duke of Beaufort in England. Photo: Dave Caulkin / AP Photo / East News

The secret to maintaining wealth is also that, like their ancestors, many modern aristocrats successfully evade taxes. In the 18th century, the satirist Charles Churchill wrote what could be called the unspoken motto of the aristocracy: “What do we care if taxes go up or down? Thanks to our wealth, we don’t pay them anyway!”

The second Duke of Westminster was sued for paying his gardeners under a scheme that excluded taxation. Then the judge, Lord Tomlin, in 1936 ruled: “Everyone has the right to conduct business in such a way as to minimize tax payments in accordance with the law. If he succeeds, then, despite the dissatisfaction with his resourcefulness of the employees of the Internal Revenue Commission or other taxpayers, no one has the right to force him to additional tax payments.

“What do we care if taxes go up or down? Thanks to our wealth, we don’t pay them anyway!”

The rest of the aristocrats firmly grasped this principle. For example, businessmen William and Edmund Vesti, founders of one of the world's largest meat retailers, bought themselves a peerage and a baronetcy for £20,000 in 1922, and then came up with a tax avoidance scheme that saved the family a total of £88 million. pounds. In 1980, the brothers' descendants were found to have paid £10 on a profit of £2.3 million. Asked how this could have happened, they shrugged, “Let's face it, no one pays more taxes than they owe. We all dodge in one way or another, don't we?"

The Trustees of Castle Howard in North Yorkshire sold a painting by Joshua Reynolds for £9.4 million to pay for the divorce of its aristocratic occupant. However, they stated that they were not required to pay the market value increase tax. The reason given is because the painting is part of the "cloths and upholstery of the castle" and is therefore considered a "drainable asset". Incredibly, in 2014 the Court of Appeal accepted such an excuse. True, the following year this tax loophole was closed.

Trusts became the main way to avoid taxes for aristocrats. An endless number of peers, owning lands and castles, placed all their assets in discretionary trusts, thereby evading both public scrutiny and inheritance tax. In 1995, the ninth Duke of Buccleuch complained that on the list of the richest British people he was estimated at 200 million pounds - when these figures applied to Buccleuch Estates Ltd, in which he did not have any shares. Legally he is right. In fact - he and his family are the beneficial owners. The same goes for a few dozen more noble families: family trust funds quietly provide income to any number of beneficiaries, and neither inheritance taxes nor public curiosity can be feared.

Lady Fiona Carnarvon, owner of Highclear Castle in southern England, poses in front of it. Photo: Niklas Halle "n / AFP / East News

…Perhaps aristocrats don't like to pay taxes, but receiving government payments is a completely different matter. Thus, landowners tried to extract the maximum possible benefits from the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union (a system of subsidizing agricultural programs in the EU). The numbers are staggering: at least one in five recipients of the largest single grants in the UK in 2015/2016 is an aristocrat. The richest received the most: the farms of the Duke of Westminster - 913,517 pounds, the farms of the Dukes of Northumberland - 1,010,672 pounds, the farms of the Duke of Marlborough - 823,055 pounds, and the estates of Lord Rothschild - 708,919 pounds. And that's just for one year. Something, but aristocrats have always been able to exploit the system.

Membership in the House of Lords also generates income, although the peers insist that it should not be regarded as a salary. As the Marquess of Salisbury said in 1958, the three guineas a day that members of the upper house received were "not an additional remuneration, but simply a reimbursement of expenses already incurred by the noble lords in the performance of their duties." Today, peers can claim £300 a day if they attend a meeting, or £150 if they don't show up at Westminster that day.

In March 2016, when the House of Lords sat for 15 days, 16 Earls received a total of £52,650 in tax-free payments (excluding travel expenses) and 13 Viscounts received £43,050. The Duke of Somerset demanded 3,600 pounds. The Duke of Montrose was paid £2,750 plus £1,570 for travel expenses: £76 for the use of his own car, £258 for train tickets, £1,087 for plane tickets and another £149 for taxis and parking fees. During the entire parliamentary session, the duke took the floor only twice.

The Duke of Montrose was paid £2,750 plus £1,570 for travel expenses. During the entire parliamentary session, the duke took the floor only twice.

... For centuries, the main secret of the viability of the old aristocracy was carefully cultivated greatness. Everything from clothes to manners was designed to impress - so that no one dared to doubt the right of the nobility to power. But nowadays the secret of aristocrats is in invisibility, almost invisibility. Commenting on the rating of ten dukes published in Tatler magazine, the Daily Mail journalists noted: “Once the holders of these titles would have become the main celebrities of their time. Today, most people will have to work hard to remember at least one person from this list.

And this is no coincidence. British laws relating to land ownership, inheritance taxes or discretionary trusts make it possible to hide wealth from the public eye. All this imperceptibly supports the power of the aristocracy. The writer Nancy Mitford, who herself was part of the British high society, but regarded it with healthy skepticism, once said: “It is quite likely that those who for a thousand years have weathered so many religious, dynastic and political shelter to survive another one." It looks like she was right.

Cover photo: Duke of Devonshire Stoker Cavendish with his wife, Duchess Amanda. Photo: Oli Scarff / AFP / East News