Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich (Alexei Petrovich Romanov; February 18, 1690, Preobrazhenskoye - June 26, 1718, St. Petersburg) - heir to the Russian throne, the eldest son of Peter I and his first wife Evdokia Lopukhina.

Unknown artist Portrait of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich Russia, XVIII century.

Demakov Evgeny Alexandrovich. Peter I and Evdokia-Lopukhin

Alexey Petrovich was born on February 18 (28), 1690 in Preobrazhensky. Baptized on February 23 (March 5), 1690, godparents - Patriarch Joachim and Princess Tatyana Mikhailovna. Name day on March 17, heavenly patron - Alexy, man of God. It was named after his grandfather, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich

Joachim, Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia

Alexis man of God

Portrait of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich.

In the early years he lived in the care of his grandmother Natalya Kirillovna. At the age of six, he began to learn to read and write under Nikifor Vyazemsky, a simple and poorly educated man, whom he sometimes beat. Likewise thrashed "honest brother of his guardian" confessor Yakov Ignatiev.

Tsarina Natalya Kirillovna, nee Naryshkina (August 22 (September 1), 1651 - January 25 (February 4), 1694) - Russian queen, second wife of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, mother of Peter I.

After imprisonment in a monastery in 1698, his mother was transferred under the care of his aunt Natalya Alekseevna and transferred to her in the Transfiguration Palace. In 1699, Peter I remembered his son and wanted to send him along with General Karlovich to study in Dresden. However, due to the death of the general, the Saxon Neugebauer from the University of Leipzig was invited as a mentor. He failed to bind the prince to himself and in 1702 lost his position.

Family portrait of Peter with Catherine, son Tsarevich Alexei and children from his second wife

Musikisky, Grigory Semenovich Miniature on enamel

Tsarevna Natalya Alekseevna (August 22, 1673 - June 18, 1716 - beloved sister of Peter I, daughter of Alexei Mikhailovich and Natalia Naryshkina.

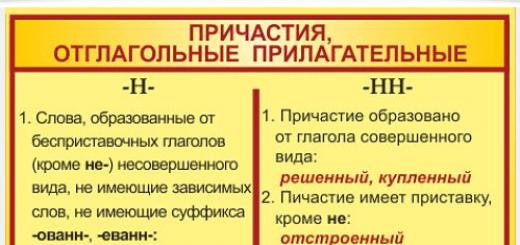

The following year, Baron Huissen took the place of educator. In 1708, N. Vyazemsky reported that the prince was studying the German and French languages, studying "four parts of tsifiri", repeats declensions and cases, writes an atlas and reads history. Continuing to live far away from his father, in Preobrazhensky, until 1709, the prince was surrounded by people who, in his own words, taught him "to have hypocrisy and conversion with priests and blacks and often go to them and drink."

Transfiguration Cathedral and the Imperial Palace.

At the same time, at the time of the Swedes’ advance into the interior of the continent, Peter instructs his son to monitor the training of recruits and the construction of fortifications in Moscow, but he remains dissatisfied with the result of his son’s work - the king was especially angry that during the work the prince went to the Suzdal monastery, where his mother was.

Evdokia Lopukhina in monastic vestments

Suzdal, Intercession Monastery. Artist Evgeny Dubitsky

In 1707, Huyssen proposed to Alexei Petrovich as a wife Princess Charlotte of Wolfenbüttel, the sister of the future Austrian Empress.

"Ceremonial portrait of Princess Sophia-Charlotte of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel"

Unknown artist

In 1709, accompanied by Alexander Golovkin and Prince Yuri Trubetskoy, he traveled to Dresden to teach German and French, geometry, fortification, and "political affairs." At the end of the course, the prince had to pass an exam in geometry and fortification in the presence of his father. However, fearing that he would force him to make a complex drawing with which he might not be able to cope and thereby give himself a reason to reproach, Alexei tried to injure his hand with a pistol shot. Enraged, Peter beat his son and forbade him to appear at court, but later, having tried to reconcile, he canceled the ban. In Slakenwert, in the spring of 1710, he saw his bride, and a year later, on April 11, a marriage contract was signed. The wedding was magnificently celebrated on October 14, 1711 in Torgau.

Alexey Petrovich Romanov.

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich Romanov

Franke Christoph Bernard.

The portrait from the collection of the Radishchev Museum in Saratov, most likely, was painted by one of the court painters of Augustus the Strong. This is the earliest known pictorial portrait of Charlotte Christina Sophia. It is possible that it was written in connection with the upcoming wedding in 1711.

Charlotte Christina Sophia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

Charlotte Christina Sophia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

Johann Paul Luden

Charlotte Christina Sophia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

Unknown artist

G.D. Molchanov

In the marriage, the prince had children - Natalia (1714-1728) and Peter (1715-1730), later Emperor Peter II.

Birth of Peter II

Peter II and Grand Duchess Natalya Alekseevna

Louis Caravaque

Shortly after the birth of her son, Charlotte died, and the prince chose a mistress from the serfs of Vyazemsky, named Efrosinya, with whom he traveled to Europe and who was later interrogated in his case and was acquitted.

Ekaterina Kulakova as Efrosinya in Vitaly Melnikov's feature film "Tsarevich Alexei"

Stills from the film "Tsarevich Alexei"

Escape abroad

The death of a son and the death of his wife coincided with the birth of the long-awaited son of Peter himself and his wife Catherine - Tsarevich Peter Petrovich.

Tsarevich Pyotr Petrovich (October 29 (November 9), 1715, St. Petersburg - April 25 (May 6), 1719, ibid.) - the first son of Peter I from Ekaterina Alekseevna, who died in infancy.

As Cupid in a portrait by Louis Caravaque

This shook the position of Alexei - he was no longer of interest to his father even as a forced heir. On the day of Charlotte's funeral, Peter gave his son a letter in which he scolded him for "shows no inclination towards state affairs", and urged to improve, otherwise threatening not only to remove him from inheritance, but even worse: “if you are married, then be known that I will deprive you of your inheritance like a gangrenous ud, and don’t think to yourself that I’m only intimidation I write - I will fulfill it in truth, for for My Fatherland and people I did not regret my belly and do not regret it, then how can I pity you indecently.

Posthumous romanticized portrait of Peter I. Painter Paul Delaroche (1838).

In 1716, as a result of a conflict with his father, who demanded that he decide as soon as possible on the issue of tonsure, Alexey, with the help of Kikin (the head of the St. Copenhagen, but from Gdansk he secretly fled to Vienna and conducted separate negotiations there with European rulers, including a relative of his wife, the Austrian Emperor Charles. To maintain secrecy, the Austrians transported Alexei to Naples. Alexei planned to wait on the territory of the Holy Roman Empire for the death of Peter (who was seriously ill during this period) and then, relying on the help of the Austrians, become the Russian Tsar.

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich Romanov

According to his testimony during the investigation, he was ready to rely on the Austrian army to seize power. In turn, the Austrians planned to use Alexei as their puppet in the intervention against Russia, but abandoned their intention, considering such an enterprise too dangerous.

It is not impossible for us to achieve some success in the lands of the king himself, that is, to support any rebellions, but we actually know that this prince has neither sufficient courage nor sufficient intelligence to derive any real benefit or benefit from these [ uprisings]

- from the memorandum of Vice-Chancellor Count Schönborn (German) to Emperor Karl

Portrait of Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor"

The search for the prince did not bring success for a long time, perhaps for the reason that along with Kikin was A.P. Veselovsky, the Russian ambassador to the Vienna court, whom Peter I instructed to find Alexei. Finally, Russian intelligence tracked down the location of Alexei (Erenberg Castle in Tyrol), and the emperor was demanded to extradite the prince to Russia.

Ehrenberg Castle (Reutte)

Tannauer Johann Gonfried. Portrait of Count Pyotr Andreevich Tolstoy. 1710s

Portrait of an associate of Peter I Alexander Ivanovich Rumyantsev (1680-1749)

Borovikovsky, Vladimir Lukich

The Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire refused to extradite Alexei, but allowed P. Tolstoy to be admitted to him. The latter showed Alexei a letter from Peter, where the prince was guaranteed forgiveness of any guilt in the event of an immediate return to Russia.

If you are afraid of me, then I reassure you and promise God and His judgment that there will be no punishment for you, but I will show you better love if you listen to my will and return. But if you don’t do this, then, ... like your sovereign, I declare for a traitor and I will not leave all the ways for you, like a traitor and scolder of your father, to do what God will help me in my truth.

- from Peter's letter to Alexei

The letter, however, failed to force Alexei to return. Then Tolstoy bribed an Austrian official to "in secret" told the prince that his extradition to Russia was a settled issue

And then I admonished the secretary of the viceroy, who was used in all transfers and the man is much smart, so that, as if for a secret, he said to the prince all the above words, which I advised the viceroy to announce to the prince, and gave that secretary 160 gold chervonets, promising him to reward him in advance that this secretary did

- from Tolstoy's report

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich

This convinced Alexei that the calculations for Austrian aid were unreliable. Realizing that he would not receive help from Charles VI, and fearing a return to Russia, Alexei, through the French officer Dure, secretly wrote a letter to the Swedish government asking for help. However, the answer given by the Swedes (the Swedes undertook to provide Alexei with an army to enthrone him) was late, and P. Tolstoy managed to get Alexei's consent to return to Russia by threats and promises on October 14 before he received a message from the Swedes.

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich

The case of Tsarevich Alexei

After returning for a secret flight and activities during his stay abroad, Alexei was deprived of the right to the throne (manifesto on February 3 (14), 1718), and he himself took a solemn oath to renounce the throne in favor of brother Peter Petrovich in the Assumption Cathedral of the Kremlin in the presence father, higher clergy and higher dignitaries.

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich

At the same time, forgiveness was announced to him on the condition of recognizing all the misconduct committed (“Later yesterday, I received forgiveness on the fact that all the circumstances were conveyed to my escape and other things like that; and if something is hidden, then you will be deprived of your stomach; ... if you hide something and then obviously will be, don’t blame me: since yesterday it was announced before all the people that for this pardon not pardon”).

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich Romanov.

****

The very next day after the abdication ceremony, an investigation began, entrusted to the Secret Chancellery and headed by Count Tolstoy. Alexey, in his testimony, tried to portray himself as a victim of his entourage and shift all the blame on his entourage. The people around him were executed, but this did not help Alexei - his mistress Efrosinya gave exhaustive testimony, exposing Alexei in a lie.

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich. Gritbach steel engraving

In particular, it turned out that Alexei was ready to use the Austrian army to seize power and intended to lead a rebellion of Russian troops if the opportunity arose. It got to the point that hints of Alexei's attempts to contact Charles XII slipped through. At the confrontation, Aleksey confirmed Efrosinya's testimony, although he did not say anything about any real or imaginary ties with the Swedes. Now it is difficult to establish the full reliability of these testimonies. Although torture was not used at this stage of the investigation, Efrosinya could have been bribed, and Aleksei could give false testimony out of fear of torture. However, in cases where Efrosinya's testimony can be verified from independent sources, they are confirmed (for example, Efrosinya reported letters that Alexei wrote to Russia, preparing the ground for coming to power - one such letter (unsent) was found in the archives of Vienna).

Death

Based on the facts that surfaced, the prince was put on trial and condemned to death as a traitor. It should be noted that Aleksey's connections with the Swedes remained unknown to the court, and the guilty verdict was handed down on the basis of other episodes, which, according to the laws in force at that time, were punishable by death.

The prince died in the Peter and Paul Fortress on June 26 (July 7), 1718, according to the official version, from a blow. In the 19th century, N. G. Ustryalov discovered documents, according to which, shortly before his death (already after the verdict was passed), the prince was tortured, and this torture could have become the direct cause of his death. According to the records of the office, Alexei died on June 26. Peter I published an official notice stating that, after hearing the death sentence, the prince was horrified, demanded his father, asked his forgiveness and died in a Christian way, in complete repentance from his deed.

Alexei Zuev as Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich in Vitaly Melnikov's feature film "Tsarevich Alexei"

There is evidence that Alexei was secretly killed in a prison cell on the orders of Peter, but they strongly contradict each other in details. Published in the 19th century with the participation of M. I. Semevsky "letter from A. I. Rumyantsev to D. I. Titov"(according to other sources, Tatishchev) with a description of the murder of Alexei is a proven fake; it contains a number of factual errors and anachronisms (which was pointed out by N. G. Ustryalov), and close to the text retells the official publications about the case of Alexei that had not yet been released.

Alexei Zuev as Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich in Vitaly Melnikov's feature film "Tsarevich Alexei"

In the media, you can find information that during his lifetime, Alexey was ill with tuberculosis - according to a number of historians, the sudden death was the result of an exacerbation of the disease in prison conditions or the result of side effects of medicines.

Alexei was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral of the fortress in the presence of his father. Posthumous rehabilitation of Alexei, withdrawal from circulation of manifestos condemning him and aimed at justifying the actions of Peter "The Truth of the Monarchs' Will" Feofan Prokopovich occurred during the reign of his son Peter II (since 1727).

Chapel of St. Catherine with the graves of Tsarevich Alexei, his wife and aunt Princess Maria Alekseevna

In culture.

The personality of the prince attracted the attention of writers (beginning with Voltaire and Pushkin), and in the 19th century. and many historians. Alexei is depicted in the famous painting by N. N. Ge "Peter interrogates Tsarevich Alexei in Peterhof"(1871).

Peter I interrogates Tsarevich Alexei in Peterhof. N. N. Ge, 1871

In Vladimir Petrov's feature film "Peter the Great" (1937), Nikolai Cherkasov played the role of the prince with high dramatic skill. Here the image of Alexei Petrovich is interpreted in the spirit of official historiography as an image of a protege of obsolete forces within the country and hostile foreign powers, an enemy of Peter's reforms and the imperial power of Russia. His conviction and murder are presented as a just and necessary act, which during the years of the film's production served as an indirect argument in favor of Stalin's repressions. At the same time, it is absurd to see a ten-year-old crown prince as the head of the boyar reaction by the time of the Battle of Narva.

Glass of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich (17th century).

In Vitaly Melnikov's feature film "Tsarevich Alexei" (1997), Alexei Petrovich is shown as a man who is ashamed of his crowned father and only wants to live an ordinary life. At the same time, according to the filmmakers, he was a quiet and God-fearing person who did not want the death of Peter I and the change of power in Russia. But as a result of palace intrigues, he was slandered, for which he was tortured by his father, and his comrades were executed.

A. N. Tolstoy, "Peter the Great" - the most famous novel about the life of Peter I, published in 1945 (Alexey is shown as a minor)

D. Mordovtsev - the novel “The Shadow of Herod. (Idealists and Realists)"

D. S. Merezhkovsky - the novel “Antichrist. Peter and Alexey"

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich

The film "Tsarevich Alexei" (1995)

Faces of history

Peter I interrogates Tsarevich Alexei in Peterhof. N. N. Ge, 1871

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich was born on February 18, 1690 in the village of Preobrazhensky near Moscow in the family of Tsar Peter I and Tsarina Evdokia Feodorovna, nee Lopukhina. Alexei's early childhood was spent in the company of his mother and grandmother, Tsarina Natalya Kirillovna, and after September 1698, when Evdokia was imprisoned in the Suzdal Monastery, Alexei was taken in by his aunt, Princess Natalya Alekseevna. The boy was distinguished by curiosity and the ability to learn foreign languages, by nature he was calm, prone to contemplation. He early began to be afraid of his father, whose energy, irascibility and propensity for transformation repelled rather than attracted Alexei.

The prince was educated by foreigners - first the German Neugebauer, then Baron Huissen. At the same time, Peter tried to involve his son in military affairs and periodically took him with him to the front of the Northern War.

But in 1705, Huyssen entered the diplomatic service, and the 15-year-old prince, in essence, was left to his own devices. His confessor, father Jacob, began to exert a great influence on him. On his advice, in 1707, the prince visited his mother in the Suzdal monastery, which caused the wrath of Peter. The father began to load his son with various assignments related to the army - for example, Alexei visited Smolensk, Moscow, Vyazma, Kyiv, Voronezh, Sumy with inspections.

At the end of 1709, the tsar sent his son to Dresden, under the pretext of further study of the sciences, but in fact wanting to arrange his marriage to a German princess. Sophia-Charlotte of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel was chosen as a candidate, and although Alexei did not have special sympathy for her, he did not argue with his father's will. In October 1711, in Torgau, in the presence of Peter I, Alexei married Sophia. As expected, this marriage did not become happy. In 1714, Alexei and Sophia had a daughter, Natalia, and on October 12, 1715, a son, Peter. Ten days later, Sophia succumbed to the effects of childbirth.

By this time, the king was already very dissatisfied with his son. He was annoyed both by Alexei's addiction to wine and his association with people who were a covert opposition to Peter and his policies. The behavior of the heir before the exam, which Alexei had to pass after returning from abroad in 1713, caused a particular fury of the king. The prince was so afraid of this test that he decided to shoot himself through his left hand and thus save himself from having to make drawings. The shot was unsuccessful, the hand was only seared with gunpowder. Peter became so angry that he severely beat his son and forbade him to appear in the palace.

In the end, the tsar threatened to deprive Alexei of hereditary rights if he did not change his behavior. In response, Alexei himself renounced the throne, not only for himself, but also for his newborn son. “Before I see myself,” he wrote, “I’m inconvenient and indecent for this matter, I’m also very deprived of memory (without which it’s possible to do nothing) and with all the powers of the mind and body (from various diseases) I have weakened and become indecent to the rule of so many people, where it requires a man not as rotten as me. For the sake of heritage (God grant you many years of health!) Russian after you (even though I didn’t have a brother, and now, thank God, I have a brother, to whom God grant health) I don’t apply and I won’t apply in the future. Peter I was dissatisfied with this answer and once again urged his son to either change his behavior or take the veil as a monk. The prince consulted with his closest friends and, having heard from them a significant phrase that “the hood will not be nailed to the head”, agreed to be tonsured. However, the tsar, who was serving abroad, gave Alexei another six months to think.

It was then that the prince matured a plan to flee abroad. The closest assistant to the prince was the former close associate of Peter I, Alexei Vasilyevich Kikin. In September 1716, Peter sent a letter to his son, ordering him to immediately arrive in Copenhagen to take part in hostilities against Sweden, and Alexei decided to use this pretext to escape without interference. On September 26, 1716, together with his mistress Efrosinya Fedorova, her brother and three servants, the prince left St. Petersburg for Libau (now Liepaja, Latvia), from where he went to Vienna via Danzig. This choice was not accidental - the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, whose residence was in Vienna, was married to the sister of the late wife of Alexei. In Vienna, the prince appeared to the Austrian Vice-Chancellor Count Shenborn and asked for asylum. As a token of gratitude for the hospitality, Alexei offered the Austrians the following plan: he, Alexei, waits for the death of Peter in Austria, and then, with the help of the Austrians, occupies the Russian throne, after which he dissolves the army, fleet, transfers the capital from St. Petersburg to Moscow and refuses to conduct an offensive foreign policy .

In Vienna, they became interested in this plan, but they did not dare to openly provide shelter to the fugitive - Charles VI did not enter into a quarrel with Russia. Therefore, under the guise of a criminal Kokhanovsky, Alexei was sent to the Tyrolean castle of Ehrenberg. From there, through secret channels, he sent to Russia several letters addressed to influential representatives of the clergy, in which he condemned his father's policy and promised to return the country to the old path.

Meanwhile, the search for the fugitive began in Russia. Peter I ordered the Russian resident in Vienna, Veselovsky, to find the prince at all costs, and he soon found out that Erenberg was the residence of Alexei. At the same time, the Russian tsar entered into correspondence with Charles VI, demanding that Alexei be returned to Russia "for paternal correction." The emperor evasively replied that he did not know anything about Alexei, but, apparently, he decided not to contact the dangerous fugitive further, because they decided to send Alexei from Austria to the fortress of St. Elmo near Naples. However, Russian agents "figured out" the fugitive prince there too. In September 1717, a small Russian delegation headed by Count P. A. Tolstoy came to Naples and began to persuade Alexei to surrender. But he was adamant and did not want to return to Russia. Then I had to go for a military trick - the Russians bribed the secretary of the Neapolitan viceroy, and he "secretly" told Alexei that the Austrians were not going to protect him, they were planning to separate him from his mistress and that Peter I himself was already going to Naples. Hearing about this, Alexei fell into a panic and began to seek contacts with the Swedes. But he was reassured - they promised that he would be allowed to marry his mistress and lead a private life in Russia. Peter's letter of November 17, in which the tsar promised complete forgiveness, finally convinced Alexei that everything was in order. On January 31, 1718, the prince arrived in Moscow, and on February 3, he met with his father. In the presence of the senators, Alexei repented of his deed, and Peter confirmed his decision to forgive him, setting only two conditions: the renunciation of the rights to the throne and the extradition of all accomplices who helped the prince to escape. On the same day, Alexei renounced his right to the throne in the Kremlin's Assumption Cathedral in favor of his three-year-old son Peter.

On February 4, the interrogations of Alexei began. In the "interrogation sheets" he told in detail everything about his accomplices, in fact, shifting all the blame on them, and when they were executed, he decided that the worst was over. With a light heart, Alexey began to prepare for the wedding with Efrosiniya Fedorova. But she, who was returning to Russia separately from the prince due to childbirth, was immediately arrested and, during interrogations, told so much about her lover that she actually signed his death warrant. Now it became clear to Peter that his son was not only influenced by his environment, but he himself played an active role in the conspiracy. At a confrontation with Fedorova, Alexei initially denied, but then confirmed her testimony. On June 13, 1718, Peter I withdrew from the investigation, asking the clergy for advice on what to do with his traitor son, and ordering the Senate to give him a fair sentence. The Supreme Court of 127 people decided that “the prince concealed his rebellious intent against his father and his sovereign, and the intentional search from ancient years, and the search for the throne of the father and in his belly, through various insidious inventions and pretense, and the hope of mob and desire father and sovereign of his imminent death. On June 25, guarded by four guard non-commissioned officers, the prince was taken from the Peter and Paul Fortress to the Senate, where he heard the death sentence.

Further events are covered with a veil of secrecy so far. According to the official version, on June 26, 1718, at 6 pm, Alexei Petrovich died suddenly at the age of 28 from a “strike” (brain hemorrhage). But modern researchers suggest that the true cause of Alexei's death was torture. It is also possible that he was killed on the orders of Peter I. The prince was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in the presence of his father. The son of Alexei Petrovich ascended the throne of the Russian Empire in 1727 under the name of Peter II and ruled for three years. In his reign, the official rehabilitation of Alexei took place.

Like many historical figures with a complex and unusual fate, the figure of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich has long been a "tidbit" for historical novelists, playwrights, fans of "conspiracy theories", and more recently film directors. There are many interpretations of Alexei's life - from the unconditional condemnation of "complete insignificance and a traitor" to an equally unconditional sympathy for a subtle and educated young man, ruthlessly trampled on by his own father. But no matter how subsequent generations treated him, there is no doubt that Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich was one of the most mysterious and dramatic figures in Russian history.

Vyacheslav Bondarenko, Ekaterina Chestnova

Is Peter I to blame for the death of his son Alexei Petrovich?

ALEXEY PETROVICH (1690-1718) - Tsarevich, the eldest son of Tsar Peter I. Alexei was the son of Peter from his first marriage with E. Lopukhina and was brought up in an environment hostile to Peter. Peter wanted to make his son continue his work - the radical reform of Russia, but Alexei avoided this in every possible way. The clergy and boyars surrounding Alexei turned him against his father. Peter threatened Alexei to deprive him of his inheritance and imprison him in a monastery. In 1716, Alexei, fearing his father's wrath, fled abroad - first to Vienna, then to Naples. With threats and promises, Peter returned his son to Russia, forced him to abdicate the throne. However, Alexei did it with joy.

“Father,” he wrote to his wife Efrosinya, “took me to eat and treats me mercifully! God grant that in the future it will be the same, and that I may wait for you in joy. God forbid that I live happily with you in the countryside, because you and I did not want anything, only to live in Rozhdestvenka; you yourself know that I do not want anything, if only to live with you to death.

In exchange for abdication and admission of guilt, Peter gave his son the word not to punish him. But the abdication did not help, and Alexei's desire to get away from political storms did not come true. Peter ordered an investigation into his son's case. Alexey simply told about everything he knew and planned. Many people from Alexei's entourage were tortured and executed. The prince did not escape torture either. On June 14, 1718, he was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, and on June 19, torture began. The first time they gave him 25 blows with a whip and asked if everything that he showed earlier was true. On June 22, new testimony was taken from Alexei, in which he confessed his plan to overthrow the power of Peter, to raise an uprising throughout the country, since the people, in his opinion, stood for old beliefs and customs, against his father's reforms. True, some historians believe that some of the testimony could have been falsified by the interrogators to please the king. In addition, as contemporaries testify, Alexei was already suffering from a mental disorder at that time. The Frenchman de Lavie, for example, believed that “his brain is out of order”, which is proved by “all his actions.” In his testimony, the tsarevich agreed that the supposedly Austrian emperor Charles VI promised him armed assistance in the struggle for the Russian crown.

The denouement was short.

On June 24, Alexei was again tortured, and on the same day the supreme court, which consisted of the generals, senators and the Holy Synod (a total of 120 people), sentenced the prince to death. True, some of the judges from the clergy actually evaded an explicit decision about death - they cited extracts from the Bible of two kinds: both about the execution of a son who disobeyed his father, and about the forgiveness of a prodigal son. The solution to this question: what to do with the son? - they left it to their father - Peter I. The civilians spoke out bluntly: to execute.

But even after this decision, Alexei was not left alone. The next day, Grigory Skornyakov-Pisarev, sent by the Tsar, came to him for interrogation: what do the extracts from the Roman scientist and historian Varro, found in the papers of the prince, mean. The prince said that he made these extracts for his own use, "to see that before it was not the way it is now," but he was not going to show them to the people.

But the matter did not end there either. On June 26, at 8 o'clock in the morning, Peter himself came to the fortress to the prince with nine close associates. Alexei was again tortured, trying to find out some more details. The prince was tortured for 3 hours, then they left. And in the afternoon, at 6 o'clock, as it is written in the books of the office of the garrison of the Peter and Paul Fortress, Alexei Petrovich passed away. Peter I published an official notice stating that, after hearing the death sentence, the prince was horrified, demanded his father, asked his forgiveness and died in a Christian way - in complete repentance from his deed.

Opinions about the true cause of Alexei's death differ. Some historians believe that he died from the unrest experienced, others come to the conclusion that the prince was strangled on the direct orders of Peter in order to avoid public execution. The historian N. Kostomarov mentions a letter written, as it says, by Alexander Rumyantsev, which tells how Rumyantsev, Tolstoy and Buturlin, at the royal command, strangled the prince with pillows (although the historian doubts the authenticity of the letter).

The next day, June 27, was the anniversary of the Battle of Poltava, and Peter arranged a celebration - a hearty feast, fun. However, really, why should he be discouraged - after all, Peter was not a pioneer here. Not to mention ancient examples, not so long ago, another Russian tsar, Ivan the Terrible, killed his son with his own hands.

Alexei was buried on June 30. Peter I was present at the funeral together with his wife, stepmother of the prince. There was no mourning.

Tsarevich Alexei is a very unpopular person not only among novelists, but also among professional historians. Usually he is portrayed as a weak-willed, sickly, almost feeble-minded young man, dreaming of the return of the orders of the old Muscovite Russia, evading cooperation with his famous father in every possible way and absolutely unsuitable for managing a huge empire. Peter I, who sentenced him to death, on the contrary, is depicted in the works of Russian historians and novelists as a hero from ancient times, sacrificing his son to public interests and deeply suffering from his tragic decision.

Peter I interrogates Tsarevich Alexei in Peterhof. Artist N.N. Ge

“Peter, in his grief as a father and the tragedy of a statesman, arouses sympathy and understanding... In the entire unsurpassed gallery of Shakespearean images and situations, it is difficult to find anything similar in its tragedy,” writes, for example, N. Molchanov. And indeed, what else could the unfortunate emperor do if his son intended to return the capital of Russia to Moscow (by the way, where is it now?), "abandon the fleet" and remove his faithful comrades-in-arms from governing the country? The fact that the "chicks of Petrov's nest" did well without Alexei and destroyed each other on their own (even the incredibly cautious Osterman had to go into exile after the accession of the prudent emperor's beloved daughter) does not bother anyone. The Russian fleet, despite the death of Alexei, for some reason fell into decline anyway - there were a lot of admirals, and the ships existed mainly on paper. In 1765, Catherine II complained in a letter to Count Panin: "We have neither a fleet nor sailors." But who cares? After all, according to the official historiographers of the Romanovs and Soviet historians in solidarity with them, the main thing is that the death of Alexei allowed our country to avoid returning to the past.

And only a rare reader of near-historical novels will come up with a strange and seditious thought: what if such a ruler, who did not inherit the temperament and warlike disposition of his father, was needed by mortally tired and devastated Russia? So-called charismatic leaders are good in small doses, two great reformers in a row is already too much: after all, the country can break down. Here in Sweden, for example, after the death of Charles XII, there is a clear shortage of people who are ready to sacrifice the lives of several tens of thousands of their fellow citizens in the name of great goals and the public good. The Swedish empire did not take place, Finland, Norway and the Baltic states are lost, but no one in this country is lamenting about this.

Of course, the comparison of Russians and Swedes is not entirely correct, because. The Scandinavians got rid of excessive passionarity back in the Viking Age. Having scared Europe to death with terrible berserk warriors (the last of which can be considered Charles XII who got lost in time) and having provided the Icelandic skalds with the richest material for creating wonderful sagas, they could afford to take a place not on the stage, but in the stalls. The Russians, as representatives of a younger ethnic group, still had to throw out their energy and declare themselves as a great people. But for the successful continuation of the work begun by Peter, at least it was necessary for a new generation of soldiers to grow up in a depopulated country, for future poets, scientists, generals and diplomats to be born and educated. Until they come, nothing will change in Russia, but they will come, they will come very soon. V.K. Trediakovsky (1703), M.V. Lomonosov (1711) and A.P. Sumarokov (1717) have already been born. In January 1725, two weeks before the death of Peter I, the future field marshal P.A. Rumyantsev was born, on February 8, 1728 - the founder of the Russian theater F.G. Peter's successor must provide Russia with 10, or better, 20 years of peace. And Alexei’s plans are quite consistent with the historical situation: “I will keep the army only for defense, but I don’t want to have a war with anyone, I will be content with the old,” he informs his supporters in confidential conversations. Now think, is the unfortunate prince really so bad that even the reigns of the eternally drunk Catherine I, the creepy Anna Ioannovna and the merry Elizabeth should be recognized as a gift of fate? And is the dynastic crisis that shook the Russian empire in the first half of the 18th century and the era of palace coups that followed it, bringing extremely dubious pretenders to power, whose rule Germaine de Stael described as “autocracy limited by a stranglehold”, really such a blessing?

Before answering these questions, readers should be told that Peter I, who, according to V.O. Klyuchevsky, “ravaged the country worse than any enemy”, was not at all popular among his subjects and was by no means perceived by them as a hero and savior of the fatherland. The era of Peter the Great for Russia became a time of bloody and far from always successful wars, mass self-immolations of Old Believers and extreme impoverishment of all segments of the population of our country. Few people know that it was under Peter I that the classic “wild” version of Russian serfdom, known from many works of Russian literature, arose. And about the construction of St. Petersburg, V. Klyuchevsky said: "There is no battle that would take so many lives." It is not surprising that in the people's memory Peter I remained the tsar-oppressor, and even more so - the Antichrist, who appeared as a punishment for the sins of the Russian people. The cult of Peter the Great began to take root in the people's consciousness only during the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna. Elizabeth was the illegitimate daughter of Peter (she was born in 1710, the secret wedding of Peter I and Marta Skavronskaya took place in 1711, and their public wedding took place only in 1712) and therefore was never seriously considered as a contender for the throne by anyone . Having ascended the Russian throne thanks to a palace coup carried out by a handful of soldiers of the Preobrazhensky Guards Regiment, Elizabeth feared all her life to become a victim of a new conspiracy and, by exalting the deeds of her father, sought to emphasize the legitimacy of her dynastic rights.

In the future, the cult of Peter I turned out to be extremely beneficial for another person with adventurous character traits - Catherine II, who, having overthrown the grandson of the first Russian emperor, declared herself the heir and successor of the cause of Peter the Great. To emphasize the innovative and progressive nature of the reign of Peter I, the official historians of the Romanovs had to resort to forgery and attribute to him some of the innovations that had become widespread under his father Alexei Mikhailovich and brother Fyodor Alekseevich. The Russian Empire in the second half of the 18th century was on the rise, great heroes and enlightened monarchs of the educated part of society were required much more than tyrants and despots. Therefore, it is not surprising that by the beginning of the 19th century, admiration for the genius of Peter began to be considered good form among the Russian nobility.

However, the attitude of the common people towards this emperor remained generally negative, and it took the genius of A.S. Pushkin to radically change it. The great Russian poet was a good historian and understood with his mind the inconsistency of the activities of his beloved hero: "Now I have sorted out a lot of materials about Peter and will never write his story, because there are many facts that I cannot agree with my personal respect for him," - he wrote in 1836. However, you can’t command the heart, and the poet easily defeated the historian. It was with the light hand of Pushkin that Peter I became the true idol of the broad masses of Russia. With the strengthening of the authority of Peter I, the reputation of Tsarevich Alexei perished completely and irrevocably: if the great emperor, tirelessly caring for the good of the state and his subjects, suddenly begins to personally torture, and then signs the order to execute his own son and heir, then there was a reason. The situation is like in the German proverb: if the dog was killed, then it was itchy. But what really happened in the imperial family?

In January 1689, 16-year-old Peter I, at the insistence of his mother, married Evdokia Fedorovna Lopukhina, who was three years older than him. Such a wife, who grew up in a closed chamber and was very far from the vital interests of young Peter, of course, did not suit the future emperor. Very soon, the unfortunate Evdokia became for him the personification of the hated orders of the old Moscow Russia, boyar laziness, arrogance and inertia. Despite the birth of children (Alexei was born on February 8, 1690, then Alexander and Pavel were born, who died in infancy), relations between the spouses were very strained. Peter's hatred and contempt for his wife could not but be reflected in his attitude towards his son. The denouement came on September 23, 1698: on the orders of Peter I, Tsarina Evdokia was taken to the Pokrovsky Suzdal maiden monastery, where she was forcibly tonsured a nun.

In the history of Russia, Evdokia became the only queen who, when she was imprisoned in a monastery, was not assigned any maintenance and no servants were allocated. In the same year, the archery regiments were disbanded, a year before these events a decree was published on shaving beards, and the following year a new calendar was introduced and a decree on clothing was signed: the tsar changed everything - his wife, army, appearance of his subjects, and even time. And only the son, in the absence of another heir, remained the same. Alexei was 9 years old when the sister of Peter I, Natalya, snatched the boy from the hands of his mother, who was forcibly taken to the monastery. Since then, he began to live under the supervision of Natalya Alekseevna, who treated him with undisguised hatred. The prince rarely saw his father and, apparently, did not suffer much from separation from him, since he was far from delighted with Peter's unceremonious favorites and the noisy feasts accepted in his entourage. Nevertheless, it has been proven that Alexei never showed open dissatisfaction with his father. He also did not shy away from studies: it is known that the prince knew history and sacred books well, perfectly mastered French and German, studied 4 actions of arithmetic, which is quite a lot for Russia at the beginning of the 18th century, had a concept of fortification. Peter I himself at the age of 16 could only boast of the ability to read, write and knowledge of two operations of arithmetic. Yes, and an older contemporary of Alexei, the famous French king Louis XIV, against the background of our hero, may seem ignorant.

At the age of 11, Alexei went with Peter I to Arkhangelsk, and a year later, as a soldier of a bombardment company, he was already participating in the capture of the Nienschanz fortress (May 1, 1703). Please note: the “meek” Alexei first takes part in the war at the age of 12, his warlike father - only at the age of 23! In 1704, 14-year-old Alexei was inseparably in the army during the siege of Narva. The first serious disagreement between the emperor and his son took place in 1706. The reason for this was a secret meeting with his mother: Alexei was called to Zhovkva (now Nesterov near Lvov), where he received a severe reprimand. However, in the future, relations between Peter and Alexei normalized, and the emperor sent his son to Smolensk to procure provisions and collect recruits. With the recruits that Alexey sent, Peter I was dissatisfied, which he announced in a letter to the prince. However, the point here, apparently, was not a lack of zeal, but the difficult demographic situation that developed in Russia, not without the help of Peter himself: Alexey, and the father is forced to admit that he was right. April 25, 1707 Peter I sends Alexei to oversee the repair and construction of new fortifications in Kitai-Gorod and the Kremlin. The comparison is again not in favor of the famous emperor: 17-year-old Peter amuses himself with the construction of small boats on Lake Pleshcheyevo, and his son at the same age is preparing Moscow for a possible siege by the troops of Charles XII. In addition, Alexei is instructed to lead the suppression of the Bulavin uprising. In 1711, Alexei was in Poland, where he supervised the procurement of provisions for the Russian army abroad. The country was devastated by the war, and therefore the activity of the prince was not crowned with special success.

A number of highly respected historians emphasize in their writings that Alexei was in many cases a "nominal leader." Agreeing with this statement, it should be said that the majority of his illustrious peers were the same nominal commanders and rulers. We calmly read reports that the twelve-year-old son of the famous Prince Igor Vladimir in 1185 commanded the retinue of the city of Putivl, and his peer from Norway (the future king Olaf the Holy) in 1007 ravaged the coasts of Jutland, Frisia and England. But only in the case of Alexei we maliciously remark: but he could not seriously lead because of his youth and inexperience.

So, until 1711, the emperor was quite tolerant of his son, and then his attitude towards Alexei suddenly changes dramatically for the worse. What happened in that ill-fated year? On March 6, Peter I secretly married Marta Skavronskaya, and on October 14, Alexei married the Crown Princess of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel Charlotte Christina-Sophia. At this time, Peter I thought for the first time: who should be the heir to the throne now? A son from an unloved wife, Alexei, or the children of a beloved woman, “a friend of the hearty Katerinushka,” who will soon, already on February 19, 1712, become the Russian Empress Ekaterina Alekseevna? The relationship of an unloved father with a son unkind to his heart could hardly be called cloudless before, but now they are deteriorating completely. Alexei, who had been afraid of Peter before, now experiences panic fear when communicating with him and, in order to avoid a humiliating exam when returning from abroad in 1712, even shoots in the palm. Usually this case is presented as an illustration of the thesis about the pathological laziness of the heir and his inability to learn. However, let's imagine the composition of the "examination committee". Here, with a pipe in his mouth, lounging on a chair, sits not quite sober sovereign Pyotr Alekseevich. Near him, impudently grinning, stands an illiterate member of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Great Britain, Alexander Danilych Menshikov. Other “chicks of Petrov’s nest” are crowding nearby, who are closely watching any reaction of their master: if he smiles, they rush to kiss him, if he frowns, they will trample him without any pity. Would you like to be in the place of Alexei?

As other evidence of the "unfitness" of the heir to the throne, the tsarevich's handwritten letters to his father are often cited, in which he characterizes himself as a lazy, uneducated, physically and mentally weak person. It should be said here that until the time of Catherine II, only one person had the right to be smart and strong in Russia - the ruling monarch. All the rest, in official documents addressed to the king or emperor, called themselves "poor mind", "wretched", "sluggish serfs", "unworthy slaves" and so on, so on, so on. Therefore, self-humiliating, Alexei, firstly, follows the generally accepted rules of good manners, and secondly, demonstrates his loyalty to his father-emperor. And we will not even talk about the testimony obtained under torture in this article.

After 1711, Peter I begins to suspect his son and daughter-in-law of deceit and in 1714 sends Mrs. Bruce and Abbess Rzhevskaya to see how the birth of the crown princess will go: God forbid, they will replace the stillborn child and finally close the way up to the children from Catherine. A girl is born and the situation loses its sharpness for a while. But on October 12, 1715, a boy is born in the family of Alexei - the future Emperor Peter II, and on October 29 of the same year, the son of Empress Ekaterina Alekseevna, also named Peter, is born. Alexei's wife dies after giving birth, and at the commemoration for her, the emperor hands his son a letter demanding that he "improve without hypocrisy." Not brilliant, but quite regularly serving his 25-year-old son, Peter reproaches him with dislike for military affairs and warns: “Do not imagine that you are my only son.” Alexey understands everything correctly: on October 31, he renounces his claims to the throne and asks his father to let him go to the monastery. And Peter I was frightened: in the monastery, Alexei, having become inaccessible to secular power, would continue to be dangerous for the long-awaited and beloved son of Catherine. Peter knows very well how his subjects treat him and understands that the pious son, who suffered innocently from the arbitrariness of his father, the “antichrist”, will certainly be called to power after his death: the hood is not nailed to his head with nails. At the same time, the emperor cannot and clearly oppose the pious desire of Alexei. Peter orders his son to "think" and takes a "time out" - he goes abroad. In Copenhagen, Peter I makes another move: he offers his son a choice: go to a monastery, or go (not alone, but with his beloved woman - Euphrosyne!) to him abroad. This is very similar to a provocation: the prince, driven to despair, is given the opportunity to escape, so that later he can be executed for treason.

In the 1930s, Stalin tried to repeat this trick with Bukharin. In February 1936, in the hope that the “Party favorite” severely criticized in Pravda would run away and ruin his good name forever, he sent him along with his beloved wife to Paris. Bukharin, to the great dismay of the leader of the peoples, returned.

And the naive Alexei fell for the bait. Peter calculated correctly: Alexei was not going to betray his homeland and therefore did not ask for asylum in Sweden (“Hertz, this evil genius of Charles XII ... terribly regretted that he could not use Alexei’s betrayal against Russia,” writes N. Molchanov) or in Turkey. There was no doubt that from these countries, after the death of Peter I, Alexei would sooner or later return to Russia as emperor, but the prince preferred neutral Austria. There was no need for the Austrian emperor to quarrel with Russia, and therefore it was not difficult for Peter's emissaries to return the fugitive to his homeland: “Sent to Austria by Peter to return Alexei, P.A. Tolstoy succeeded in completing his task with surprising ease... The Emperor hurried to get rid of his guest” (N. Molchanov).

In a letter dated November 17, 1717, Peter I solemnly promises forgiveness to his son, and on January 31, 1718, the prince returns to Moscow. And already on February 3, arrests among the friends of the heir began. They are tortured and forced to testify. On March 20, the infamous Secret Chancellery is created to investigate the prince's case. June 19, 1718 was the day the torture of Alexei began. From these tortures, he died on June 26 (according to other sources, he was strangled so as not to carry out the death sentence). And the very next day, June 27, Peter I gave a magnificent ball on the occasion of the anniversary of the Poltava victory.

So there was no trace of any internal struggle and no hesitation of the emperor. Everything ended very sadly: on April 25, 1719, the son of Peter I and Ekaterina Alekseevna died. An autopsy showed that the boy was terminally ill from the moment of birth, and Peter I killed his first son in vain, clearing the path to the throne for the second.

Continued conflict

The young children of Alexei Petrovich were not the only replenishment in the royal family. The ruler himself, following his unloved son, acquired another child. The child was named Peter Petrovich (his mother was the future Catherine I). So suddenly Alexei ceased to be the sole heir of his father (now he had a second son and grandson). The situation put him in an ambiguous position.

In addition, such a character as Alexei Petrovich clearly did not fit into the life of the new St. Petersburg. A photo of his portraits shows a man a little sickly and indecisive. He continued to fulfill the state orders of his powerful father, although he did this with obvious reluctance, which again and again angered the autocrat.

While still studying in Germany, Alexei asked his Moscow friends to send him a new confessor, to whom he could frankly confess everything that bothered the young man. The prince was deeply religious, but at the same time he was very afraid of his father's spies. However, the new confessor Yakov Ignatiev was indeed not one of Peter's henchmen. One day, Alexei told him in his hearts that he was waiting for the death of his father. Ignatiev replied that many Moscow friends of the heir wanted the same. So, quite unexpectedly, Alexei found supporters and embarked on a path that led him to death.

Difficult decision

In 1715, Peter sent a letter to his son, in which he confronted him with a choice - either Alexei corrects himself (that is, he begins to engage in the army and accepts his father's policy), or goes to the monastery. The heir was in a dead end. He did not like many of Peter's undertakings, including his endless military campaigns and cardinal changes in life in the country. This mood was shared by many aristocrats (mainly from Moscow). In the elite, there really was a rejection of hasty reforms, but no one dared to openly protest, since participation in any opposition could end in disgrace or execution.

The autocrat, having delivered an ultimatum to his son, gave him time to think over his decision. The biography of Alexei Petrovich has many similar ambiguous episodes, but this situation has become fateful. After consulting with those close to him (primarily with the head of the St. Petersburg Admiralty, Alexander Kikin), he decided to flee Russia.

Escape

In 1716, a delegation headed by Alexei Petrovich set off from St. Petersburg to Copenhagen. Peter's son was in Denmark to see his father. However, while in Gdansk, Poland, the prince suddenly changed his route and actually fled to Vienna. There Alexei began to negotiate for political asylum. The Austrians sent him to secluded Naples.

The plan of the fugitive was to wait for the death of the then sick Russian tsar, and after that to return to his native country to the throne, if necessary, then with a foreign army. Alexei spoke about this later during the investigation. However, these words cannot be accepted with certainty as the truth, since the necessary testimony was simply knocked out of the arrested person. According to the testimonies of the Austrians, the prince was in hysterics. Therefore, it is more likely that he went to Europe out of despair and fear for his future.

In Austria

Peter quickly found out where his son had fled. People loyal to the tsar immediately went to Austria. An experienced diplomat Pyotr Tolstoy was appointed head of an important mission. He reported to the Austrian Emperor Charles VI that the very fact of Alexei's presence in the land of the Habsburgs was a slap in the face of Russia. The fugitive chose Vienna because of his family ties to this monarch through his short marriage.

It is possible that under other circumstances Charles VI would have protected the exile, but at that time Austria was at war with the Ottoman Empire and was preparing for a conflict with Spain. The emperor did not want at all to receive such a powerful enemy as Peter I in such conditions. In addition, Alexei himself blundered. He acted in panic and was clearly unsure of himself. As a result, the Austrian authorities made concessions. Pyotr Tolstoy received the right to see the fugitive.

Negotiation

Pyotr Tolstoy, having met with Alexei, began to use all possible methods and tricks to return him to his homeland. Kind-hearted assurances were used that his father would forgive him and allow him to live freely on his own estate.

The envoy did not forget about clever hints. He convinced the prince that Charles VI, not wanting to spoil relations with Peter, would not hide him in any case, and then Alexei would definitely end up in Russia as a criminal. In the end, the prince agreed to return to his native country.

Court

On February 3, 1718, Peter and Alexei met in the Moscow Kremlin. The heir wept and begged for forgiveness. The king pretended that he would not be angry if his son renounced the throne and inheritance (which he did).

After that, the trial began. First, the fugitive betrayed all his supporters, who "persuaded" him to a rash act. Arrests and regular executions followed. Peter wanted to see his first wife Evdokia Lopukhina and the opposition clergy at the head of the conspiracy. However, the investigation found that a much larger number of people were dissatisfied with the king.

Death

Not a single short biography of Alexei Petrovich contains accurate information about the circumstances of his death. As a result of the investigation, which was conducted by the same Peter Tolstoy, the fugitive was sentenced to death. However, it never took place. Alexei died on June 26, 1718 in the Peter and Paul Fortress, where he was held during the trial. It was officially announced that he had a seizure. Perhaps the prince was killed on the secret orders of Peter, or perhaps he died himself, unable to endure the torture he experienced during the investigation. For an all-powerful monarch, the execution of his own son would be too shameful an event. Therefore, there is reason to believe that he instructed to deal with Alexei in advance. One way or another, but the descendants did not know the truth.

After the death of Alexei Petrovich, a classical point of view developed about the causes of the drama that had happened. It lies in the fact that the heir came under the influence of the old conservative Moscow nobility and the clergy hostile to the king. However, knowing all the circumstances of the conflict, one cannot call the prince a traitor and at the same time not bear in mind the degree of guilt of Peter I himself in the tragedy.

), was born on February 18, 1690. From childhood, Alexei was with his mother and grandmother (Natalya Kirillovna Naryshkina), and after the death of the latter (1694) he was under the exclusive influence of Evdokia, unloved by Peter. From 1696, Alexei Petrovich began to learn to read and write using Korion Istomin's primer; the leader of his upbringing was Nikifor Vyazemsky. In September 1698, the prince's mother was sent to the Suzdal Intercession Monastery and 10 months later she was tonsured, and Alexei was taken to the village of Preobrazhenskoye and placed under the supervision of Peter I's sister, Princess Natalya Alekseevna.

Peter dreamed of sending Alexei Petrovich to Dresden for appropriate education, but changed his mind and in June 1701 hired the Saxon citizen Martin Neugebauer "for instruction in the sciences and moralizing" the prince. Neugebauer did not stay long as an educator (until 1702). In 1703, a certain Giesen was already appointed chief chamberlain of the prince under the command of Prince Menshikov. In general, the upbringing of the prince was the most stupid. The influence of discontented adherents of Russian antiquity and mother overpowered others. Peter I did not notice much what his young son was doing and demanded from him only the execution of his orders. Alexey Petrovich was afraid of his father, did not love him, but with great reluctance obeyed his orders. At the end of 1706 or at the very beginning of 1707, Alexei Petrovich arranged a meeting with his mother, for which Peter I was very angry with his son.

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich. Portrait by J. G. Tannauer, 1710s

Since 1707, the father demands that the tsarevich help him in some matters: in February of this year, the tsar sends Alexei Petrovich to Smolensk to prepare provisions and recruit recruits, in June the tsarevich informs Peter about the amount of bread in Pskov in view of the provision of provisions. Alexey Petrovich writes from Smolensk about the departure of archers and soldiers. In October we see him in Moscow, where he was ordered to supervise the fortification of the Kremlin and be present in the office of ministers. In the same 1707, through Gisen, the marriage of the prince with Princess Charlotte of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, the sister of the German Empress, began, but the teachings of Alexei Petrovich had not yet stopped. In January 1708, N. Vyazemsky reported to Peter "about the educational, in German, history and geography, and government studies of the prince." This year, Alexei Petrovich ordered in Preobrazhensky "regarding officers and undergrowths", wrote to his father "about the order regarding the outrageous letters of followers, gunpowder, the collection of infantry regiments and their uniforms." At the same time, Peter I forces Alexei Petrovich to take a more active part in pacifying the Bulavinsky rebellion. In 1709 we find the prince in Little Russia; he is encouraged there to energetic activity, but he is weary of it and falls ill.

Soon after his recovery, Alexei Petrovich leaves for Moscow. In 1710, through Warsaw and Dresden, the prince traveled to Karlsbad, during the journey he met his betrothed bride. The purpose of the trip was, according to Peter I, “to learn German and French, geometry and fortification”, which was done in Dresden after a trip to Karlsbad. In the spring of 1711, Alexei Petrovich was in Braunschweig, and in October of the same year, the marriage of the prince and the princess, who remained in the Evangelical Lutheran religion, took place; Peter I from Torgau also came to the wedding. The father really hoped that marriage would change his son and put new energy into him, but his calculations turned out to be wrong: Princess Charlotte was not created for such a role. Just as Alexei Petrovich had no desire for fatherly activities, so his wife had no desire to become Russian and act in the interests of Russia and the royal family, using her influence on her husband. Husband and wife were similar to each other - the inertia of nature; energy, offensive movement against obstacles were alien to both. The nature of both demanded to run away, to lock themselves away from any work, from any struggle. This flight from each other was enough for the marriage to be morally barren.

In July 1714, the Crown Princess had a daughter, Natalia. Alexey Petrovich was abroad. By the same time, the prince's relationship with the captured serf maiden of his teacher, Vyazemsky, Efrosinya Fedorova, as well as the final discord between father and son, dates back to this time. On the eve of the birth of Alexei Petrovich's son Peter (the future Emperor Peter II - October 12, 1715), Peter I writes a letter to the prince reproaching him for neglecting the war and threatening to deprive him of the throne due to stubbornness. Shortly after the birth of his son, Alexei Petrovich's wife fell ill and died. Relations between the prince and Peter became even more aggravated; On October 31, 1715, Alexei Petrovich, after consulting with his favorites Kikin and Dolgorukov, answered the tsar that he was ready to renounce the inheritance. 4 days before, Peter had a son, Peter, from his new companion, Catherine.

In January 1716, the tsar wrote to Alexei Petrovich "cancel your temper or be a monk." The prince replies that he is ready to have his hair cut. Peter gives him six months to think about it, but at that time they are already beginning to prepare the prince's flight: Kikin goes abroad and promises to find refuge there. Peter from abroad writes (August 1715) the third formidable letter with a decisive command to either get a haircut immediately, or go to him to participate in hostilities. Alexei Petrovich slowly got ready to go along with Efrosinya. In Danzig, the prince disappeared. Arriving through Prague to Vienna, he introduced himself to the Austrian Vice-Chancellor, Count. Shenborn, complained about his father and asked for patronage. The request was accepted (Emperor Charles VI was the brother-in-law of Alexei Petrovich). The prince was first sent to the town of Veperburg, and then to Tyrol, to the Ehrenberg castle.

In the spring of 1717, after a long unsuccessful search, Peter I found out that Alexei Petrovich was hiding in the emperor's possessions. Diplomatic negotiations did not lead to anything: they refused to extradite the prince. Rumyantsev told the tsar where Alexei Petrovich was; began to follow him. In April 1717, the prince moved with his close associates to the castle of Sant'Elmo, near Naples. Peter soon sent to the Caesar Tolstoy and Rumyantsev to demand the crown prince, threatening war, at the same time, the tsar promised Alexei Petrovich forgiveness if he returned to Russia. In August, Tolstoy and Rumyantsev were allowed a meeting with the prince. In September, all efforts to convince Alexei Petrovich to return to his homeland did not lead to anything. Finally, in October, threats, deceptions and cunning managed to convince him. Alexey Petrovich asked only that he be allowed to live in the village, and Efrosinya was left with him. Peter I promised this.

On January 1, 1718, the tsarevich was already in Danzig, and by February 1, in Moscow. On February 3, Alexei Petrovich met with his father and abdicated. A search began in the case of the prince, to which Kikin, Afanasiev, Glebov, Bishop Dosifei, Voronov, who were close to him, were involved. V. Dolgoruky, many others, as well as the ex-wife of Peter I, Evdokia Lopukhina, and Princess Maria Alekseevna. Tsarevich has not yet been interrogated or tortured. On March 18, Peter I and his son went to Petersburg. Efrosinya was also brought here, but without any meeting with Alexei Petrovich and, despite the fact that she was pregnant, she was sent to the Peter and Paul Fortress (there is no news about Efrosinya's child later). Efrosinya testified, revealing all the behavior of Alexei Petrovich abroad, all the talk of the prince about the death of his father and a possible rebellion against him.

Peter I interrogates Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich in Peterhof. Painting by N. Ge, 1871

In the month of May, Peter I himself began to arrange interrogations and face-to-face confrontations between Alexei Petrovich and Efrosinya, and ordered the tsarevich to be tortured. On June 14, Alexei Petrovich was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, where he was tortured. On June 24, 1718, the prince was sentenced to death by 127 members of the supreme court. June 26 at 8 o'clock in the morning began to gather in the garrison: Peter I, Menshikov, Dolgoruky, Golovkin, Apraksin, Pushkin, Streshnev, Tolstoy, Shafirov, Buturlin, and Aleksey Petrovich was tormented. At 11 o'clock, the crowd dispersed. “On the same afternoon at 6 o’clock, being under guard in the Trubetskoy peal in the garrison, Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich reposed.”

On June 30, 1718, in the evening, in the presence of the tsar and tsarina, the body of the tsarevich was interred in the Peter and Paul Cathedral next to the coffin of his late wife. There was no mourning.