Over the centuries, many factors and events have influenced the position of the peasantry. The enslavement of peasants can be divided into four main stages, from the first decrees legalizing serfdom to its abolition.

The first stage (the end of the XV - the end of the VXI centuries) - St. George's Day

Due to the growth of the master's duties, the peasants are increasingly leaving the landowners for other lands. The power of the sovereign is not yet so great for the introduction of strict prohibitions. But the need to preserve the loyalty of the nobility requires action. Therefore, in 1473, he publishes the Sudebnik, according to which leaving the landowner is now possible only after the completion of arable work, on November 26, during the week before St. George's Day and the week after, subject to payment of the "elderly".

In 1581, against the backdrop of the severe devastation of the country, Tsar Ivan 4 the Terrible issues a Decree on the introduction of "reserved years", temporarily forbidding peasants to leave even on St. George's Day.

The second stage (the end of the 16th century - 1649) - the Cathedral Code

In the era of the Time of Troubles, it becomes more and more difficult to keep the peasants from fleeing. In 1597, a decree was issued on the introduction of a 5-year term for the investigation of fugitive peasants. In subsequent years, the period of "lesson years" increases. The duties of local administrations include the search for fugitives and the interrogation to which all alien peasants are subjected.

The Cathedral Code of 1649 finally recognizes the peasants as the property of landowners. Serf status is affirmed as hereditary - the children of a serf father and free people who marry serfs also become serfs. The “lesson summers” announced by Ivan the Terrible are canceled: the decree on the indefinite search for fugitives comes into force.

The third stage (the middle of the 17th - the end of the 18th centuries) - the complete strengthening of serfdom

The most difficult stage of the enslavement of the peasants. The landlords get the full right to dispose of the serfs: sell, subject to corporal punishment (often leading to the death of peasants), exile without trial to hard labor or to Siberia. By this time, serfs were virtually no different from black slaves on New World plantations.

The fourth stage (the end of the 18th century - 1861) - the decomposition and abolition of serfdom

By the beginning of this period, the decadence of the serf system becomes more and more obvious. The development of liberal ideas among the nobility leads to the formation of a negative attitude of its advanced part towards the phenomenon of serfdom. The understanding of the inefficiency and shamefulness of the very phenomenon of serfdom is gradually being strengthened at the very top. Attempts to change the existing situation are made, then Alexander 1. But only half a century later, Alexander 2 publishes a Manifesto, giving serfs the right to dispose of their freedom, change their activities and move to other classes at their discretion.

Interesting Facts

- Serfdom in Russia was unevenly distributed across the territories. It is known that in the western territories the percentage of serfs was much higher than in other areas. While in Siberia and Pomorie there was no serfdom as such.

- The eternal faith of the common people in the "good king" was the reason that many peasants did not believe the content of the Manifesto of Alexander II. Almost immediately after the announcement, numerous rumors arose that the text of the true Manifesto was hidden from them, and a fake was read out: the peasants themselves received freedom, but their land remained in the ownership of the master. The peasant, on the other hand, was a user and could become the owner only by buying his allotment from the landowner.

- The genetically formed psychology of the serfs sometimes led to the fact that after the reform, the peasants refused the will simply because they did not know what to do with it: “This is my home. Where will I go? It is known that kind-hearted human relations with the master and earlier often also caused the reluctance of the former serfs to leave him. For example, the nanny, sung by Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin, Arina Rodionovna, also being a serf and having received freedom, refused to leave her masters, whom she loved with all her heart.

In the 17th century the fate of the Russian countryside has changed. going on the final enslavement of the peasants, and for almost 200 years Russia takes the path of serfdom. This changed the perspectives of the Russian countryside, depriving it of development opportunities. The village became an object for pumping out resources. Her way of life, economy, mode of production were mothballed.

Years have taken a heavy toll on the Russian village civil war(Troubles) early XVII in. Almost the entire European part of the country was devastated from the Volga region to Smolensk, from the southern counties to Novgorod and Pskov. Documents show a sharp increase in the number (up to 40%) of bobyl households (i.e. households of impoverished peasants), as well as a reduction in arable land (in some counties it was only 4–5% of cultivated land) and an increase in fallow land. The crisis was overcome only in the 1620s. For almost a quarter of a century, the Russian village lay in ruins.

Subsequent years of the 17th century. characterized by an increase in agricultural production. This is primarily due to the colonization processes. Thanks to the construction of serif lines, there was a significant expansion of the economic territory of Russia to the south. The fertile lands of the Central Chernozem Region and the South of Russia entered the agricultural circulation. Russian colonization of the Volga region, regions of the Urals, Siberia continued.

At the end of the XVII century. Several tens of thousands of Russian peasants already lived in Siberia. Colonization here was of a focal nature, separate territories can be distinguished: Tobolsk district, Tomsk-Kuznetsk, Yenisei-Krasnoyarsk and Ilimo-Angara agricultural regions. The development of agriculture in Siberia was an important factor in the development of the region: it began to provide itself with bread, which facilitated the colonization processes, helped Russian explorers to explore new spaces of Eurasia and allowed the center to leave grain reserves for its own needs.

The predominant type of peasant settlements in the 17th century, according to A. A. Shennikov, was churchyard:"a village in which estates of representatives of the communal administration, a church with courtyards of the clergy and a cemetery were grouped near the market square, but there were few or no estates of ordinary peasants who lived in villages." Pogosts were centers of communal lands stretching for many kilometers (both cultivated arable land and undeveloped forest tracts). On these communal lands there were numerous peasant farms scattered far from each other. villages - small settlements of three to five households. If the village perished, instead of it remained wasteland. When the peasants founded new village on virgin lands, this place was called repair. A similar organization of lands and settlements was common on the lands of the black-mossed North. The territory of the community in the documents was called "graveyard" or "volost".

This system dates back to the period of medieval colonization of the northern forest regions. In the 17th century villages were enlarged, numerous peasant households appeared in churchyards. Such a churchyard turned into village- a large settlement with a church, the center of an Orthodox parish. As the landownership estates of feudal lords spread in the villages (such a settlement was called village).

Thus, according to A. A. Shennikov, a settlement system was formed with three types of multi-family settlements: a village - without a feudal estate and without a church, a village - with a feudal estate, but without a church, and a village - with a church.

Agricultural technology continued to dominate three-field, effective for fertile chernozem, but not always satisfactory for poor podzolic soils. On them, the land in the three-field cycle did not have time to recover, it was necessary to manure: according to the calculations of A. Sovetov, manure from 3-6 cows was required per tithe. Peasant farms did not have such a large number of livestock, and the fields were gradually depleted. Attempts to introduce five- and six-fields with a rotational cycle in some large farms have not received distribution.

Despite the spread of the three-field system, important positions in land use were retained undercut. This was due to two factors. First of all, undercutting is necessary during colonization processes, when the land for new arable land must be cleared from the forest. The second factor, according to scientists, was the spread of peasant "unaccounted for arable land." The increase in taxes forced the peasant to start arable land in the forest that was not taken into account for tax collectors to feed them. They were cleared and processed with the help of undercutting. The exact number of such lands and their role in the peasant economy in the XVI-XVII centuries. cannot be accounted for, we cannot assess the scale and role of this "shadow" sector of the peasant economy.

A set of crops in the XVII century. has not undergone significant changes. It was still rye, wheat, barley, oats, buckwheat, millet, peas, flax, hemp. According to N. A. Gorskaya, at the end of the 16th - beginning of the 17th centuries. in the central Russian districts, rye occupied 50% of the sown area, oats - 41.9, barley - 6%. Wheat is rare, its sown area was no more than 2%. To the north of the central counties, rye and barley prevailed, to the south - rye and oats, with an increase in the share of wheat and buckwheat crops.

There was no significant evolution in the tools for cultivating the land: plows, plows, and harrows were still used. Some exception is the distribution in the XVII century. so-called roe deer with convex ploughshare, cutter and blade, turning over the plowed land. This tool was more effective than the traditional two-pronged plow.

Bread was threshed with flails. Grinded grain in mills, mostly water or manual. Windmills were in the XVII century. less spread. Grain yield in the 17th century. does not change compared to the previous time, and averages sam-three - sam-four. On the newly developed chernozem lands of the South, in productive years, the yield could reach sam-six to sam-seven.

In the 17th century It is the time of the heyday of Russian gardening and horticulture. In Moscow, special Ogorodnaya and Sadovaya settlements even arose, supplying fruits and vegetables to the court.

According to the historian I. E. Zabelin, at the end of the 17th century. The palace economy in Moscow owned 52 gardens, in which "there were 46,694 apple trees, 1,565 pears, 42 duli (pear varieties), 9,136 cherries, 17 vine bushes, 582 plums, 15 ridges of strawberries, 7 walnut trees, a cypress bush, 23 trees prunes, 3 sloe bushes, “... in addition, many bushes and ridges of cherries, raspberries, red, white and black currants, kryzhu, bayberry, silverberry or rose hips of red and white” ...

Of the crops, cabbage, carrots, beets, turnips, onions, cucumbers, pumpkins were still bred. However, new crops also appear: celery, lettuce, etc. Melons were grown from exotic berries. Greenhouse gardening is gaining ground. Apples, pears, cherries, plums, gooseberries, currants, raspberries, and strawberries were grown in the orchards. Scientists have found that in the XVII century. such varieties of apples as “filling”, “titov”, “Bel Mozhaiskaya”, “Arkat”, “Scroup”, “Kuzminsky”, “white malets”, “red malets” were known. Gardeners learned to grow grapes, watermelons, even lemon and orange trees. True, I had to think about where to put them in the winter.

It is very significant that from the XVII century. We have received information about the systematic cultivation of flowers in flower beds. They grew peonies, roses, tulips, carnations. This indicates the emergence of an aesthetic component in the economy: agriculture was no longer treated only as a utilitarian source of income, at least in some aristocratic families.

In the 17th century cattle breeding, like agriculture, has undergone minor changes compared to the previous period. Farms still kept cows, pigs, sheep, goats, and poultry. The main draft animal for the peasants was the horse. Gradually, areas of specialization in breeding breeds of cattle are outlined (mainly in the North): Kholmogory, Arkhangelsk, Mezen lands. There will even be special breeds of cattle, such as Kholmogory.

Russian peasants in the 17th century lived on four categories of land:

- 1) secular property (patrimonial and local);

- 2) church andmonastic ;

- 3) palace (personal household of the monarch);

- 4) black-mallowed (state lands).

The division of peasants into categories was also corresponding.

Owning peasants(both secular landowners and ecclesiastical, monastic ones) performed a large amount of duties for the master (tire in food, cash quitrent, work in the feudal yard, etc.). The forms and sizes of duties differed quite significantly in the localities, but quitrent types of rent prevailed. Corvee was mostly assigned to rural serfs.

A special category was made up of personally free black peasants, bearing sovereign tax- a significant amount of taxes and duties on the state. In historiography, there is a point of view (L.I. Kopanev), according to which in the XVI-XVII centuries. Black-eared peasants considered themselves the owners of the land (although the land was state-owned, they could give it away, exchange it, bequeath it, etc.), it is in this social stratum that one can look for the first sprouts of entrepreneurship among the Russian peasantry. The prospects for the development of such new entrepreneurial relations in the native countryside were cut short by the introduction of serfdom ("black" lands were gradually distributed by the monarch to the feudal lords, turned into possessive ones).

The lower strata of the rural population were beans and rural serfs, and in the black-mossed lands - housekeepers, neighbors, hirelings and so on. Bobyls - ruined, poor peasants who rented an allotment - due to poverty, they could not bear the sovereign's taxes. However, since the 1620s, as B. D. Grekov showed, Bobyl’s households were taken into account along with peasant households when calculating the “living quarter”, i.e. taxable unit. The size of the tax was calculated according to the number of households, thus, in fact, the tax was extended to the beans (another question is how they paid it). In 1679, the bobs, who had their own, albeit rented, yard, were completely overlaid with state taxes. Rural serfs were quite widespread, they were actively involved in agricultural work on the master's farm, especially for corvee.

The entire first half of the 17th century. - the history of the tightening of serf legislation. The Code of Vasily Shuisky of 1607 introduced a 15-year term for detecting fugitive peasants. This was a serious attack on the peasantry: if hiding from the authorities for five years (according to the previous decree on lesson years of 1597) in the Russian expanses was not difficult, then a 15-year period doomed the fugitive peasant to a long journey, to the Don, from who "is not extradited", to the North or to Siberia. It was impossible to hide in Central Russia for 15 years.

The nobility did not stop there, and the government of Mikhail Fedorovich repeatedly received collective petitions to extend the term for the investigation of fugitive peasants (in 1637, 1641, 1645, 1648). In 1642, a 10-year investigation was introduced for the fugitives and a 15-year investigation for those who were exported, those who were lured (“taken away”) by stronger landowners. The only thing that kept the authorities from introducing an indefinite investigation was the fact that after the Time of Troubles there were large migrations of the taxable population. The peasants fled from ruined estates to stronger owners. The return of such fugitives would mean the weakening of these strong farms, which would inevitably entail a drop in tax collection. But money was vital for the resurgent Russia, therefore, making concessions to the nobility, the government of Mikhail Fedorovich did not take the main step, it hesitated to introduce an indefinite investigation.

In 1645, the government of B. I. Morozov planned peasant reform. By that time, it became clear that the path of an infinite increase in the lesson years was a dead end. The peasants continued to flee to the Don, from which "there is no extradition", at least in fact. The peasants fled from the poor estates of the nobility to the rich boyar estates, where they were sheltered and where they were inaccessible to any detachments of "detectives". Extending the search term did not solve the problem. At the same time, it was also impossible to endlessly ignore the demands of the nobility to provide their estates with labor while the boyar's son was fighting at the front. Once an unsuccessful solution to this problem has already become one of the factors in the emergence of a civil war - the Time of Troubles.

Morozov's government in 1645 agreed with the need to introduce an indefinite search for peasants, but with one amendment: first, new census books must be compiled, which will become new "fortresses". It is difficult to say what motivated the government: the unwillingness to get bogged down in the thousands of lawsuits that have accumulated over controversial issues about the ownership of fugitive peasants since the beginning of the 17th century, or the desire to protect large boyar estates. After all, as I. L. Andreev noted, the proposed order actually assigned runaway peasants to their new owners, and a huge mass of service nobility lost the chance of ever regaining their runaways. However, the Russian government since the end of the XVI century. was prone to compromise solutions to the peasant issue: on the one hand, it stood guard over the interests of the nobility, on the other hand, it did not want to drive a good taxpayer, a good taxpayer, even a fugitive, from his familiar place.

The Council Code of 1649 introduced an indefinite search for fugitive peasants. This is considered the point of final establishment of serfdom, although serf legislation was developed and refined throughout the second half of the century.

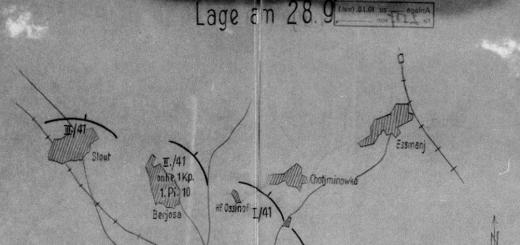

Having introduced an indefinite search, it was necessary to work out the mechanism for its implementation. Initially, the authorities took the primitive path of raids: teams were sent from the center to different counties detectives, which were supposed to identify settlers and fugitives and return them to their owners. The scope of the investigations expanded. In 1676–1678 a house-to-house census was carried out, which helped detective activities. Now the investigation of the fugitives could be put on a more solid documentary basis.

Unlike other European states, in Russia the process of enslaving the peasants was lengthy. He went through several stages. Each has its own characteristic features.

Part of the peasants lost their freedom back in the days Ancient Russia. It was then that the first forms of addiction began to appear. Someone voluntarily left under someone else's protection. Others worked out debt obligations on the lands of a prince or boyar. When the estates were alienated, the peasants who did not have time to work off the debt were also transferred to the new owner.

But it was not yet enslavement as such. Most of the peasants were free.

The time frame of the first stage can be determined by the X-XV centuries.

The process of enslaving the peasants is based on economic reasons.

The lands were divided into three categories according to ownership: church, boyar (or service) and sovereign.

It so happened in Russia that the peasants lived and worked on lands that did not belong to them. Three categories of owners owned the lands: the church, the boyars (or servants) and the sovereign. There were also so-called black lands. Legally, they had no owners. Peasants massively settled on such lands, cultivated them and harvested. But they were not considered property.

That is, by legal right, the peasant was a free cultivator, cultivating the land under an agreement with the owner. The independence of the peasants consisted in the ability to leave one land plot and move to another. He could do this only by paying off the owner of the land, that is, when the field work ended. The landowner did not have the right to expel the peasant from the land before the end of the harvest. In other words, the parties entered into a land agreement.

The state did not intervene in these relations until a certain time.

In 1497, Ivan III compiled the Sudebnik, which was designed to protect the interests of land owners. It was the first document establishing the norms of the beginning process of enslavement of the peasants. The fifty-seventh article of the new law introduced a rule according to which peasants were allowed to leave their owners at a strictly defined time. The reference time was chosen on November 26. A church holiday was celebrated in honor of St. George. By this time, the crop was harvested. Peasants were allowed to leave a week before St. George's Day and within a week after it. The law obliged the peasants to pay the "old" master, a special tax (in cash or in kind) for living on his land.

This was not yet the enslavement of the peasants, but it seriously limited their freedom.

In 1533, Ivan IV the Terrible ascended the throne.

The reign of the Grand Duke of "All Russia" was difficult. Campaigns against Kazan and the Astrakhan Khanate, the Livonian War had a detrimental effect on the country's economy. Huge amount land was devastated. The peasants were removed from their homes.

Ivan the Terrible updates the Sudebnik. In the new legislation of 1550, the king confirms the status of St. George's Day, but increases the "old". Now it was almost impossible for a peasant to get away from the feudal lord. The amount of the fee was unbearable for many.

The second stage of the process of enslavement of the peasants begins.

Devastating wars force the government to impose additional taxes, which makes the situation of the peasants even more difficult.

Apart from economic problems, the country was ravaged natural disasters: crop failures, epidemics, pestilence. Agriculture fell into decay. The peasants, driven by hunger, fled to the warm southern regions.

In 1581, Ivan the Terrible introduces reserved years. Peasants are temporarily forbidden to leave their owners. By this measure, the tsar tried to prevent the desolation of the landlords' lands.

The landed estates were provided with a labor force.

In the same years, a description of the land was carried out. The purpose of this event was to sum up the results of the economic crisis. The event was accompanied by a mass distribution of allotments to landowners. At the same time, scribe books were compiled, attaching peasants to the land where they were found by the census.

In Russia, serfdom was actually established. But the final enslavement of the peasants has not yet taken place.

The third stage in the formation of serfdom is associated with the reign of Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich. The tsar himself was incapable of governing the country; Boris Godunov was in power.

The position of "Tsar Boris" himself was very precarious. He was forced to fight for power, flirting with the boyars and the nobility.

The result was another step towards the final enslavement of the peasants.

In 1597 he introduces the Lesson Years. The law stated that the landowner could search everywhere for his fugitive peasant for five years. Vasily Shuisky, who came to power later, extended this period to 15 years.

The country is still in a difficult economic situation. Hunger provokes popular discontent. Godunov is forced to make some concessions to the peasants. In 1601, he issues a Decree restoring St. George's Day.

Now the landowners were already dissatisfied. They began to hold the peasants by force. Clashes began. This inflamed an already difficult social situation.

In 1606, Vasily Shuisky came to power and immediately began to fight the peasant movement.

He studies the scribe books of the past years. Based on them, Shuisky issues a Decree. In it, he declares all the peasants registered for their landowners as "strong".

And yet it was only the next, fourth stage in the enslavement of the peasants. The process has not ended completely.

In the law issued by Vasily Shuisky, in addition to increasing the term for detecting a peasant, a fine was established for accepting a fugitive.

Theoretically, the peasants could still leave the landowner. But the payment to the owner was increased to three rubles a year - a huge amount. Especially given the numerous epidemics and crop failures.

Hiring a peasant was allowed only with the permission of the landowner to whom he belonged.

That is, there was no talk of any actual freedom of the peasant.

The final enslavement of the peasants fell on the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov. In 1649, the Council Code was issued, which put an end to this process. The code determined the place of the peasantry in society. Legislation was very harsh in relation to dependent peasants.

The Code determines the permanent serfdom of the peasants. Census books became the basis for attachment.

Lesson summers have been cancelled. The right of indefinite investigation of fugitive peasants was introduced.

Serfdom was defined as hereditary. Not only children, but also other relatives of the peasant belonged to the landowner.

In the event of the death of a landowner, all serfs belonging to him (along with other property!) Passed on to his son or daughter.

A free girl, having tied the knot with a serf, herself became dependent.

Serfs could be left as a pledge, sold. The landowner could give the peasant for a gambling debt.

Peasants could sell goods only from wagons.

Thus, by the end of the 17th century, the final enslavement of the peasants took place. The centuries-old process has been completed.

In subsequent years (up to late XVIII century), the situation of the peasants worsened.

Laws, unpopular with the people, establishing the full power of the landowners were adopted. Peasants could be sold without land, sent to hard labor without trial. Peasants were forbidden to complain about their masters.

The enslavement of the peasants intensified the split in the social strata and provoked popular riots. Initially aimed at the development of the land economy, serfdom eventually became an extremely inefficient form of economic relations.

First eta n (late XV - late XVI centuries.) The process of enslavement of peasants in Russia was quite lengthy. Back in the era of Ancient Russia, part of the rural population lost personal freedom and turned into serfs and serfs. In conditions of fragmentation, the peasants could leave the land on which they lived and move to another landowner.

Sudebnik. The Sudebnik of 1497 streamlined this right, confirming the right of the owner's peasants after paying the "elderly" to the possibility of "exit" on St. George's Day (St. George's Day) in autumn (the week before November 26 and the week after).

At other times, the peasants did not move to other lands - employment in agricultural work, autumn and spring mudslides, and frosts interfered. But the fixation by law of a certain short transition period testified, on the one hand, to the desire of the feudal lords and the state to limit the right of the peasants, and on the other hand, to their weakness and inability to fix the peasants to the personality of a certain feudal lord. In addition, this right forced the landowners to reckon with the interests of the peasants, which had a beneficial effect on the social economic development countries. This norm was also contained in the new Sudebnik of 1550.

However, in 1581, in the conditions of the extreme ruin of the country and the flight of the population, Ivan IV introduced "reserved years" that forbade peasant exit in the territories most affected by disasters. This measure was emergency and temporary, "up to the tsar's decree."

Second phase. (end of the 16th century - 1649)

Decree on universal enslavement. In 1592 (or in 1593), i.e. in the era of the reign of Boris Godunov, a decree was issued (the text of which has not been preserved), forbidding exits throughout the country and without any time limits. The introduction of the regime of reserved years made it possible to start compiling scribe books (i.e., to conduct a population census that created conditions for attaching peasants to their place of residence and returning them in case of flight and further capture by the old owners). In the same year, the lordly plow was "whitewashed" (that is, exempted from taxes), which stimulated service people to increase its area.

"Lesson years". The compilers of the decree of 1597, who established the so-called. "lesson years" (the period of investigation of fugitive peasants, initially determined at five years). After a five-year period, the fleeing peasants were subject to enslavement in new places, which was in the interests of large landowners, as well as the nobles of the southern and southwestern counties, where the main streams of the fugitives were directed. The dispute over labor hands between the nobles of the center and the southern outskirts became one of the reasons for the upheavals of the early 17th century.

Final fortification. At the second stage of the enslavement process, there was a sharp struggle between various groupings of landowners and peasants on the issue of the term for detecting the fugitives, until the Council Code of 1649 canceled the “lesson years”, introduced an indefinite search, and declared the “eternal and hereditary fortress” of the peasants. Thus ended the legal registration of serfdom

At the third stage (With mid-sixteenth 1st century until the end of the 18th century), serfdom developed along an ascending line. For example, according to the law of 1675, the owner's peasants could already be sold without land. Largely under the influence of the socio-cultural split caused by the reforms of Peter the Great, the peasants began to lose the remnants of their rights and, in terms of their social and legal status, approached the slaves, they were treated like "talking cattle." Serfs differed from slaves only in the presence of their own farm on the land of the landowner. In the XVIII century. the landlords received the full right to dispose of the personality and property of the peasants, including exiling them without trial to Siberia and hard labor.

At the fourth stage (the end of the 18th century - 1861) serf relations entered the stage of their decomposition. The state began to take measures that somewhat limited the arbitrariness of the landlords, moreover, serfdom, as a result of the spread of humane and liberal ideas, was condemned by the advanced part of the Russian nobility.

As a result, for various reasons, it was canceled by the Manifesto of Alexander II in February 1861.

The reign of Fyodor Ioannovich. Formation of the prerequisites for the Troubles.

The years from 1598 to 1613 are known in the historical literature under the name of the Time of Troubles or the time of the invasion of impostors. Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich, the last of the surviving sons of Ivan the Terrible, died on January 7, 1598 childless. His death ended the dynasty of Rurikovich, who ruled Russia for more than 700 years. On the Russian throne On February 22, 1598, a representative of the boyar family ascended, Boris Fedorovich Godunov, the brother of Tsarina Irina Feodorovna, the wife of Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich.

Troubles - a deep spiritual, economic, social, and foreign policy crisis that befell Russia in the late 16th - early 17th century. It coincided with the dynastic crisis and the struggle of boyar groups for power, which brought the country to the brink of disaster. The main signs of unrest are kingdomlessness (anarchy), imposture, civil war and intervention. According to some historians, Time of Troubles can be considered the first civil war in the history of Russia.

Contemporaries spoke of the Time of Troubles as a time of “unsteadiness”, “disorder”, “confusion of minds”, which caused bloody clashes and conflicts. The term "troubles" was used in everyday speech of the 17th century, office work of Moscow orders.

The prerequisites for the Troubles were the consequences of the oprichnina and the Livonian War of 1558-1583: the ruin of the economy, the growth of social tension.

The causes of the Time of Troubles as an era of anarchy, according to the historiography of the 19th - early 20th century, are rooted in the suppression of the Rurik dynasty and the intervention of neighboring states (especially united Lithuania and Poland, which is why the period was sometimes called "Lithuanian or Moscow ruin") in the affairs of the Muscovite kingdom. The totality of these events led to the appearance on the Russian throne of adventurers and impostors, claims to the throne from the Cossacks, fugitive peasants and serfs. Church historiography of the 19th - early 20th century. considered the Time of Troubles as a period of spiritual crisis of society, seeing the reasons in the distortion of moral and moral values.

The first stage of the Time of Troubles began with a dynastic crisis caused by the murder of Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible of his eldest son Ivan, the coming to power of his brother Fyodor Ivanovich and the death of their younger half-brother Dmitry (according to many, the de facto ruler of the country, Boris Godunov, was stabbed to death by henchmen). The throne lost the last heir from the Rurik dynasty.

The death of the childless tsar Fyodor Ivanovich (1598) allowed Boris Godunov (1598–1605) to come to power, ruling energetically and wisely, but unable to stop the intrigues of disgruntled boyars.

The term "Time of Troubles", accepted in pre-revolutionary historiography, referring to the turbulent events of the early 17th century, was resolutely rejected in Soviet science as "noble-bourgeois" and replaced by a long and even somewhat bureaucratic title: "Peasant War and Foreign Intervention in Russia". Today, the term "Time of Troubles" is gradually returning: apparently, because it not only corresponds to the word usage of the era, but also quite accurately reflects historical reality.

Among the meanings of the word "distemper" given by V.I. Dalem, we meet "rebellion, rebellion ... general disobedience, discord between the people and the authorities [source 9]. However, in modern language, the adjective "vague" has a different meaning - unclear, indistinct. And in fact, the beginning of the 17th century. and indeed the Time of Troubles: everything is in motion, everything fluctuates, the contours of people and events are blurred, kings change with incredible speed, often in different parts of the country and even in neighboring cities they recognize the power of different sovereigns at the same time, people sometimes change their political orientation: either yesterday’s allies disperse into hostile camps, or yesterday’s enemies act together ... The Time of Troubles is the most complex interweaving of various contradictions - class and national, intra-class and inter-class ... And although there was foreign intervention, it is impossible to reduce only to it all the variety of events of this and indeed the Time of Troubles.

Naturally, such a dynamic period was extremely rich not only in bright events, but also in various development alternatives. In days of nationwide upheaval, accidents can play a significant role in guiding the course of history. Alas, the Time of Troubles turned out to be a time of lost opportunities, when those alternatives that promised a more favorable course of events for the country did not materialize.

The purpose of the course work is to reveal and reflect as fully as possible the essence of the Time of Troubles.

1. Consider the causes and preconditions of the Time of Troubles.

2. To analyze the rule of pretenders to the Russian throne and possible alternatives for the development of Russia.

3. Consider the results and consequences of the Time of Troubles.

In the second floor. XVI - first half. 17th century there is a process of further enslavement of the peasants. This was facilitated by the strengthening of the state apparatus, the creation of such special bodies as the Robbery Order and the mouth huts to combat fugitive peasants. The Sudebnik of 1550 increased the fee charged from the peasants for leaving the landowner on St. George's Day.

In 1581, a decree was adopted on reserved years, which in practice canceled the provisions of St. George's Day. In 1597, a decree was issued on the search for runaway peasants for 5 years. These years were called "lesson summers". The formation of serfdom provoked violent resistance from the peasants and the aggravation of the class struggle, which led to the emergence of the first peasant war in Russia under the leadership of Bolotnikov. Answer to peasant war was the strengthening of serfdom. In 1607 "Lesson summers" were extended to 15 years.

The Cathedral Code of 1649 recorded the complete and final enslavement of the peasantry. "Lesson summers" were cancelled. Fugitive peasants were returned, regardless of the period of their escape from the former owner, along with their families and all their property. Moreover, the law established punishment for all those who accepted and hid runaway peasants.

Attaching a peasant to the land and a certain feudal lord was formalized as a hereditary and hereditary state of the feudal lord. The creation of a clearly regulated system of serfdom made it possible state power centrally wage a struggle against peasant uprisings, monitor taxes, assigning police functions and responsibility for the payment of state taxes by the peasants to the landowners.

State structure

In the middle of the XVI century. under Ivan IV, important reforms were carried out aimed at strengthening the centralized state. Among them, the most important was an attempt to reduce the influence of the Boyar Duma in the state. For this purpose, in 1549, the "Elect Rada" or "Near Duma" was established from specially trusted persons appointed by the tsar. It was an advisory body that, together with the tsar, decided all the most important issues of administration and pushed aside the Boyar Duma.

The centralization of the state was largely facilitated by the oprichnina. A large oprichnina territory was ruled by a special apparatus - the royal court with oprichnina boyars, courtiers, etc. The power of the king was based on a special oprichnina corps, which performed the functions of the personal protection of the king, political investigation and punitive apparatus directed against everyone who was dissatisfied with the royal power.

The social support of the oprichnina was the petty service nobility, who sought to occupy the lands and boyar peasants and strengthen their political influence.

The "Chosen Rada" sought to limit the willfulness of the tsar, to introduce his activities within the framework defined by law. As a result, all her supporters fell into disgrace. In 1565, at the height of the Livonian War, when the Russians were out of luck, Ivan the Terrible turned to decisive action. He accused all service people of draining his treasury, serving poorly, cheating, and the clergymen covering them. He divided the entire territory of the country into two parts: the zemshchina and the oprichnina (a specially allocated possession that personally belonged to the sovereign).

In the oprichnina, the tsar singled out part of the counties of the country and "1000 heads" of boyars and nobles (over 7 years of oprichnina policy, their number increased 4 times). All those landowners who did not fall into the oprichnina were withdrawn from the oprichnina districts. In return, they were supposed to receive lands in other, nepotish counties, although in fact this was a rarity. In place of the old masters in the oprichnina, the tsar placed "oprichnina service people", who formed a whole corps of guardsmen. Oprichniki took an oath to break off all communication with the zemstvo. As a sign of their rank, they wore a dog's head at the saddle - a symbol of their readiness to "gnaw" the sovereign's traitors, and a brush resembling a broom, with which they pledged to sweep treason out of the state.

The rest of the country's territory was henceforth called the Zemshchina. Having approved the oprichnina, Ivan the Terrible introduced a special government in the oprichnina lands, modeled on the national government: his own thought, his own orders, his own treasury. The zemshchina was still governed by the old state institutions and the Boyar Duma. The zemstvo administration was in charge of national affairs under the strict control of the tsar, without whose approval the Boyar Duma did nothing.

Mass terror began. As Kurbsky said, Ivan the Terrible exterminated his victims "publicly." The heads of boyars, nobles, civil servants, peasants, townspeople flew. Metropolitan Philip, who boldly condemned terror, was deposed by order of the tsar and exiled to a monastery near Tver, where a year later he was killed by Malyuta Skuratov. His cousin, the staritsky prince Vladimir Andreevich, the tsar forced his wife and youngest daughter to take poison.

Not only individuals, but entire cities were accused of treason. The culmination of the oprichnina terror was the defeat of Novgorod in 1570. Having received information about the "treason" of the Novgorodians, the tsar went on a campaign. On the way to Novgorod, the guardsmen staged bloody pogroms in Tver and Torzhok. The execution of the inhabitants of Novgorod lasted more than a month. Thousands of suspects were drowned in Volkhov. The city, including Novgorod churches, was plundered. Villages and villages were devastated, many inhabitants were killed, peasants were forcibly taken to oprichny estates and estates. After Novgorod there was Pskov, but here the matter was limited to the confiscation of property and individual punishments. As for Novgorod, according to various estimates, from 4 to 15 thousand people died here.

In 1571, the Crimean Khan Devlet-Girey made another raid on Russia. Most of the guardsmen who held the defense did not go to the service: they were more accustomed to fighting the civilian population. Khan bypassed the Russian troops, approached Moscow and set fire to it. Soon, instead of the capital, the ashes remained. The following summer, he decided to repeat the campaign. The tsar urgently called on the experienced governor Vorotynsky and united the oprichniki and zemstvo people under his command. The united army utterly defeated Devlet Giray. Less than a year later, Vorotynsky was executed on the denunciation of his serf, who claimed that the prince wanted to bewitch the king.

After the raids of the Crimean Khan, it became clear to the tsar that the existence of the oprichnina threatened the country's defense capability. In the autumn of 1572 it was cancelled. Oprichnina significantly undermined the economic and political positions of the princely-boyar aristocracy, thereby strengthening the royal power, and contributed to the elimination of specific princely separatism. But its implementation was accompanied by the colossal ruin of many lands and cities, the terrible arbitrariness of the guardsmen. This had a very negative impact on the further economic development of the country.

In the middle of the XVI century. such transformations were carried out in the central and local government of Russia as the abolition of feeding, zemstvo and labial reforms, as well as reforms in the armed forces. From the middle of the XVI century. estate-representative institutions began to convene - Zemsky Sobors. Now the state system of Russia had the following features:

* At the head of state, since 1547. the king stood. The royal throne was usually inherited. There was a procedure for electing the king at the Zemsky Sobor, which was supposed to help strengthen the authority of the monarchy;

* The king had great rights in the field of legislation, administration, court. But he ruled together with the Boyar Duma and the Zemsky Sobors;

* The composition of the Duma included nobles, representatives of the top of the urban population, trade nobility, guests. But at the same time, the Duma continued to be an organ of the well-born boyar aristocracy.

Zemsky Sobors played an important role in the administration of the state during this period. They began to gather from the middle of the XVI century. and acted until ser. 17th century In the second floor. 17th century the strengthened tsarist power already dispensed with the convocation of this class-representative institution.

The Zemsky Sobors included: the Boyar Duma, the higher clergy (the so-called "Illuminated Cathedral") and elected representatives of the nobility and cities. Most of the members were nobles. The metropolitan nobility had a special advantage in the elections, sending 2 people from all ranks and ranks, while the nobles of other cities sent one at a time. So, out of 192 elected members of the Zemsky Sobor in 1642, 44 people were representatives of the Moscow nobles.

Zemsky Sobors met in the first half. 17th century often. The convocation of the Councils was announced by a special royal charter. Each class part of the Zemsky Sobor discussed the issues raised separately and made its own judgment. Decisions were to be made by the entire composition of the Council. The duration of the work of the cathedrals was different: from several hours to several years. Thus, the work of the Zemsky Sobor, which elected Mikhail Romanov to the throne, continued during 1613-1615. The decisions of the Zemsky Sobor were formalized by the adoption of a special conciliar document, which was called the verdict. They were not formally obligatory for the tsar, but in fact he could not ignore them, because the nobles and wealthy townspeople provided him with support. Thus, Zemsky Sobors, on the one hand, limited the power of the tsar, on the other hand, strengthened it in every possible way.