In those days, the heroic life and death of this person was taught in schools and universities, plays were staged about his life, poems and songs were written about him, directors made films about him. Accordingly, many streets and settlements of the Soviet Union bore his name. So who was this man who was born 120 years ago on March 7, 1894 and left behind such a trace visible to the naked eye?

Sergei Lazo is a Bolshevik, revolutionary and participant in the Civil War, who distinguished himself in revolutionary activities in the Far East of our country. Like many heroes of the Soviet era, he is almost completely forgotten by his contemporaries. The country that made him a hero is no longer on the map. Today we could talk about him as a person who loosens “spiritual bonds.” He did this, like other revolutionaries of that period, quite successfully, Soviet power won on 1/6 of the land and for a long time became a kind of global counterweight, the second geopolitical center of the whole world. Sergei Lazo was well suited to the role of the hero of the revolution, since there were legends about his terrible death already in the 1920s. The new Soviet government needed heroes. Sergei Lazo, who died for his ideals, was one of many who were perfect for this role.

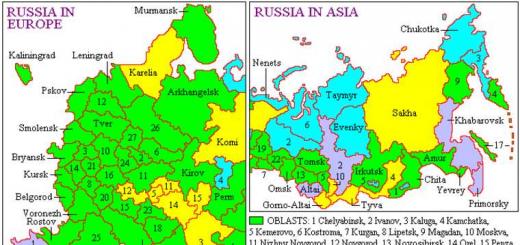

Sergei Georgievich Lazo was born on February 23 (March 7, new style) 1894 in the village of Pyatra, located in the Orhei district of the Bessarabia province (today the territory of Moldova). He came from a Moldavian noble family, and accordingly, he himself was a nobleman. His origin did not prevent him from connecting his fate with the revolutionary movement. While still studying at Russian higher educational institutions, he began to pay a lot of attention to left-wing views and movements.

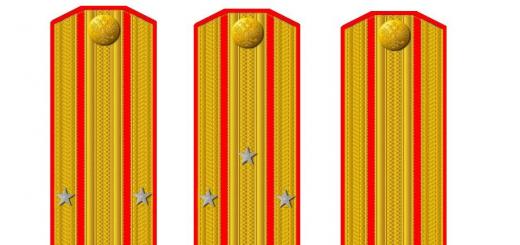

Sergei Lazo received a good education. He studied at the St. Petersburg Institute of Technology, and then at the Physics and Mathematics Department of the Imperial Moscow University (now Moscow State University). Already during his studies, he began to take part in the activities of student revolutionary circles. The First World War found Lazo studying and turned his life around. In July 1916, Sergei Lazo was mobilized into the active army. He managed to graduate from the Alekseevsky Infantry School, located in Moscow, after which he was promoted to officer in the Russian army. Initially received the rank of ensign, later second lieutenant. In December 1916, Sergei Lazo was sent to Siberia near Krasnoyarsk to the location of the 15th Siberian reserve rifle regiment.

In Krasnoyarsk, Lazo became close to the political exiles in the city and, together with them, began to conduct propaganda among the soldiers of the regiment against the ongoing imperialist war. Here in Krasnoyarsk in 1917 he joined the Party of Social Revolutionaries (SRs). Contemporaries said that this decision was not accidental. From childhood, Sergei Lazo was distinguished by maximalism of judgment and a heightened sense of justice - to the point of romanticism. Later, in the spring of 1918, Lazo left the Socialist Revolutionary Party, joining the Bolsheviks.

During the February Revolution of 1917, Lazo, together with the soldiers of the 15th reserve regiment subordinate to him, took part in the arrest of the governor of the Yenisei province Ya. G. Golobov, as well as other local senior officials. At the age of 23, Lazo became a member of the Council of Workers, Soldiers and Cossack Deputies of Krasnoyarsk. In June of the same year, the Krasnoyarsk Soviet sent the young revolutionary to Petrograd, where the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies was to be held. It was at the congress in Petrograd that Lazo saw Lenin for the only time in his life, and his personal acquaintance with the leader of the world proletariat made a very strong impression on the young man. He liked both the speech Lenin made and the radicalism of his judgments. Most likely, this also influenced the fact that in the spring of 1918 he joined the Bolsheviks.

Returning from Petrograd to Krasnoyarsk, Lazo managed to organize and lead the Red Guard detachment. In October 1917, when another revolution took place in Petrograd, this detachment worked according to the “old scheme”. Members of the Lazo detachment arrested senior officials of the now provisional government. Lazo soldiers occupied most of the government institutions, banks, and the treasury. The garrison of the city was completely in the hands of Sergei Lazo.

In Krasnoyarsk everything went relatively peacefully. But by November the situation began to change. On November 1, there was a speech by the cadets of the Omsk school of warrant officers, who supported the provisional government. Lazo detachments were brought in to suppress these forces; the Red Guards coped with the task. However, already in December 1917, a new uprising of officers, cadets, Cossacks and students broke out in Irkutsk. Red Guard detachments were urgently sent to the city. One of these detachments was commanded by Lazo.

On December 26, 1917, the most serious battles broke out on the streets of Irkutsk. Lazo led a combined detachment of Red Guards to storm the Tikhvin Church. After many hours of fighting, they managed to capture the church; then the detachment advanced along Amurskaya Street, trying to break through to the local White House (the governor’s house). However, in the evening of the same day, the cadets were able to regain control of Irkutsk with a counterattack; Lazo and some of his fighters were captured. On December 29, the parties declared a temporary truce, and in the following days the Reds were able to seize power in Irkutsk, which may have saved Lazo’s life. After his release, Sergei Lazo was appointed military commandant of Irkutsk and head of its garrison.

The battles in Irkutsk became a real baptism of fire for Lazo. Already during these battles, he showed quite extraordinary abilities in military affairs, speed of orientation, and personal courage. He personally taught the Red Guards street fighting tactics, as well as throwing hand grenades; Lazo himself knew how to do this perfectly. Very soon, the former warrant officer of the Russian army will head the Trans-Baikal Front. Such a dizzying military career can only be achieved during a revolution.

He led the actions of the Transbaikal Front from the end of February until August 28, 1918. On this day, at a conference of party and Soviet workers, it was decided to switch to partisan forms of warfare. Under his command, the front was able to achieve a number of successes, in particular, he managed to push back parts of the famous Ataman Semenov to the territory of Manchuria. Another success was his agreement with the Chinese authorities on a truce. In particular, China committed itself not to allow Ataman Semyonov’s units to enter Transbaikalia until April 5, 1918.

Monument to Lazo in Vladivostok

In general, despite local successes in the fight against Semenov’s detachments, the situation for the Transbaikal Front entered a critical stage after the White Czechs arrived from the Urals and Siberia. The young units of the Red Army, whose number was about 9 thousand people, found themselves sandwiched between the Czechoslovak corps and the units of Ataman Semenov. Under these conditions, the decision to switch to partisan activity was the only correct one.

Having gone underground and turned to partisan activity, Lazo again seemed to be in his element. At first, his activities were directed against the Provisional Siberian Government, which seized power in the east of the country, and then against Admiral Kolchak, who declared himself the Supreme Ruler of Russia. Since the fall of 1918, Lazo was a member of the underground Far Eastern Regional Committee of the RCP (b) in Vladivostok. In the spring of 1919, he commanded various partisan detachments that operated in Primorye. From December 1919, he headed the Military Revolutionary Headquarters for the preparation of an uprising in Primorye. It should be noted that the actions of the Red partisans in the rear of Kolchak’s troops diverted the additional forces of the Whites, who did not use them on the Ural and Siberian fronts, and undermined their support and the situation in the rear.

However, romance from the revolution could not continue endlessly. In 1920, he made a mistake that cost him his life. At the beginning of 1920, when information appeared that Kolchak's government in Siberia had fallen, the Bolsheviks in Vladivostok began preparing a rebellion, intending to overthrow Kolchak's governor in the city, General Rozanov. Lazo himself insisted on this development of events. At the same time, Vladivostok was then filled with Japanese troops.

Despite this, on January 31, 1920, Lazo carried out a coup in Vladivostok, taking control of the station, post office and telegraph. Lieutenant General Rozanov fled to Japan by ship. At the same time, for a long time the interventionists, of whom there were more than 20 thousand in the city, remained indifferent observers. Despite the fact that there were no more than a few thousand Reds in the city, Lazo declared Soviet power in the city.

The Japanese did not react to what was happening for some time. But after the incident in Nikolaevsk - the Japanese garrison in the city, as well as civilian Japanese residents and “counter-revolutionary” elements among Russian citizens were destroyed by detachments of red anarchists under the command of Yakov Tryapitsin and Nina Lebedeva, and the city itself was almost completely burned - the Japanese military began to act. According to estimates of the Chinese population and foreign citizens in the city, about 4 thousand people were killed in the city. The Nikolaev incident became a trigger for the Japanese military interventionists, who promptly responded to these events and began a full-scale fight against the Red partisan movement in the Far East. On the night of April 4-5, Lazo was arrested in Vladivostok.

At the end of May 1920, Lazo and his comrades were taken from Vladivostok by the Japanese military, who handed them over to the White Guard Cossacks. According to the version widespread in the USSR, Sergei Lazo was first tortured and then burned alive in the furnace of a locomotive, and his comrades were first shot and then burned in bags in locomotive furnaces. Later, there was even a witness, an unnamed driver, who saw how at the Ussuri railway station the Japanese military handed over 3 bags containing 3 people to the Cossacks from Bochkarev’s detachment. The Cossacks tried to push people into the locomotive firebox, but they resisted, after which they were shot and stuffed inside already dead. However, even before the events described, in April 1920, the Japanese newspaper Japan Chronicle reported that revolutionary Sergei Lazo was shot in Vladivostok, after which his corpse was burned.

Now many admit that the version with a locomotive firebox is nothing more than a legend. However, this legend turned out to be tenacious and was perfectly suited for the formation of the heroic image of a revolutionary fighter, being actively used for propaganda purposes.

Information sources:

http://irkipedia.ru/content/lazo_sergey_georgievich

http://www.calend.ru/person/2112

http://www.retropressa.ru/sergejj-lazo

http://www.peoples.ru/military/hero/lazo/history.html

Russian empire

RSFSR

Sergei Georgievich Lazo(February 23 (March 7), village of Pyatra, Orhei district, Bessarabia province, Russian Empire - May, Muravyovo-Amurskaya station) - Russian revolutionary, one of the Soviet leaders in Siberia and the Far East, participant in the Civil War. Left Social Revolutionary, since the spring of 1918 - Bolshevik.

Biography

Born on February 23 (March 7), 1894 in the village of Piatra, Orhei district, Bessarabia province (now Orhei district of the Republic of Moldova) into a noble family.

The soldiers of the 4th company of the 15th Siberian Rifle Regiment at their meeting decided to remove from their duties the company commander, Second Lieutenant Smirnov, who had declared allegiance to the oath, and elected warrant officer Sergei Lazo as their commander, simultaneously electing him as a delegate to the Krasnoyarsk Council of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies. On the night of March 2-3, elections to the Council were held in almost all companies.

In June, the Krasnoyarsk Soviet sent Sergei Lazo as its delegate to Petrograd to the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies. It was at this congress that the demarche of Lenin and the Bolsheviks took place, who were in the minority, making up only 13.5% of the delegates to the Congress. Lenin's speech made a great impression on Lazo; he really liked the radicalism of the Bolshevik leader. Returning to Krasnoyarsk, Lazo organized a Red Guard detachment there.

On June 27, 1917, the provincial executive committee of the Krasnoyarsk Council of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies was formed.

Autumn-winter 1917. Krasnoyarsk. Omsk Irkutsk

To resist the cadets, the Bolsheviks sent Red Guard detachments, among which was Sergei Lazo. The Red Guards suppressed the performance of the cadets.

In December 1917, a riot of cadets, Cossacks, officers and students took place in Irkutsk. To resist political opponents, the left bloc sent detachments of Red Guards there. The leaders of the Red Guard detachments sent to help the Bolsheviks in Irkutsk were: V.K. Kaminsky, S.G. Lazo, B.Z. Shumyatsky.

On December 26, the fiercest fighting took place in Irkutsk. A combined detachment of soldiers and Red Guards under the command of S. G. Lazo, after many hours of fighting, captured the Tikhvin Church and launched an offensive along Amurskaya Street, trying to break through to the White House, but by the evening a counterattack by the cadets drove the red units out of the city, S. G. Lazo and the soldiers taken prisoner, and the pontoon bridge across the Angara was opened. On December 29, a truce was declared, but in the following days the Reds seized power in Irkutsk. Lazo was appointed military commandant of the city and head of the garrison of Irkutsk.

Civil War (1918-1920)

One of the organizers of the coup in Vladivostok on January 31, 1920, as a result of which the power of the Kolchak governor - the chief commander of the Amur region, Lieutenant General S. N. Rozanov was overthrown and the Provisional Government of the Far East, controlled by the Bolsheviks, was formed - the Primorsky Regional Zemstvo Council.

The success of the uprising largely depended on the position of the officers of the ensign school on Russian Island. Lazo arrived to them on behalf of the leadership of the rebels and addressed them with a speech:

“Who are you, Russian people, Russian youth? Who are you for?! So I came to you alone, unarmed, you can take me hostage... you can kill me... This wonderful Russian city is the last one on your road! You have nowhere to retreat: then a foreign country... a foreign land... and a foreign sun... No, we did not sell the Russian soul in foreign taverns, we did not exchange it for overseas gold and guns... We are not hired, we defend our land with our own hands, we defend our land with our own breasts , we will fight with our lives for our homeland against foreign invasion! We will die for this Russian land on which I now stand, but we will not give it to anyone!”

As a result, the school of warrant officers declared its neutrality in relation to the uprising, which made the fall of Rozanov's power inevitable.

Arrest and death

In the latest edition of the History of the Russian Far East, this version of Lazo’s death is described as a legend. Also, “refutations” often appear in the press and on the Internet, according to which the steam locomotive E a is supposedly installed in Ussuriysk as a monument. According to these “statements”, Lazo could not have been burned in that locomotive because such a series would appear only 21 years after his death (E a locomotives were supplied from the USA to the USSR during the Second World War under Lend-Lease). However, in Ussuriysk it is not the “Lend-Lease” E a that is installed, but a steam locomotive from the Civil War - E L, and these are two similar (especially for non-specialists) varieties of E series locomotives, on which in the 1990s, during the next “cosmetic” painting, a painter mistakenly wrote the series “E a”. E l steam locomotives were built by American factories in 1916-1917, a total of 475 locomotives were built. Further along the sea, these locomotives were sent to Vladivostok, from where they were already distributed throughout the country. At the end of 1922, there were 277 E-series steam locomotives on the roads of Siberia, the bulk of which were the El variety. Thus, if Lazo was burned in a steam locomotive, then it is most likely that this locomotive was precisely E l (locomotives more powerful than E were not available in Siberia at that time).

Memory

During the years of Soviet power, streets in many cities and towns in the USSR were named after Sergei Lazo. A massive renaming of streets took place in 1967 in connection with the 50th anniversary of Soviet power and in order to perpetuate the memory of veterans of the October Socialist Revolution and Civil War. Streets and squares named in honor of Sergei Lazo still bear this name in dozens of cities in the territory of the former

Sergei Georgievich Lazo (February 23, 1894, the village of Pyatra, Orhei district, Bessarabia province of the Russian Empire - May 1920, Muravyovo-Amurskaya station, now Lazo, Primorsky Krai of the Russian Federation) - revolutionary, military commandant (1917), one of the Soviet leaders in Siberia and the Far East East, participant in the Civil War. Left Socialist Revolutionary, since the spring of 1918 - Bolshevik.

Encyclopedic reference

He studied at the St. Petersburg Institute of Technology, then at the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Moscow University; participated in the work of student revolutionary circles. In July 1916 he was mobilized into the army and graduated from the Alekseevsky Infantry School in Moscow. In December 1916, with the rank of ensign, he was assigned to the 5th Siberian Reserve Infantry Regiment in Krasnoyarsk, a member of the organization of Left Socialist Revolutionary Internationalists. In March 1917, member of the regimental committee, chairman of the soldiers' section of the Council. In October 1917, delegate to the 1st All-Siberian Congress of Soviets. Participated in, appointed chief of the garrison and military commandant. Since the beginning of 1918, a member, since February 1918, commander of the troops of the Trans-Baikal Front, member of the Far Bureau of the Central Committee of the RCP (b). In 1919–1920, the leader of the partisan movement in Primorye was captured by Japanese interventionists and burned in a locomotive furnace.

Irkutsk Historical and local history dictionary. - Irkutsk, 2011

Biography

The beginning of revolutionary activity

Born in the village of Piatra, Bessarabia province (now Orhei region of Moldova) in 1894 into a noble family. He studied at the St. Petersburg Institute of Technology, then at the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of the Imperial Moscow University, and participated in the work of revolutionary student circles.

In July 1916, he was mobilized into the Imperial Army, graduated from the Alekseevsky Infantry School in Moscow and was promoted to officer (ensign, then second lieutenant). In December 1916, he was assigned to the 15th Siberian Reserve Rifle Regiment in Krasnoyarsk. There he became close to political exiles and, together with them, began to conduct defeatist propaganda among the soldiers. He joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party and joined the left faction.

Revolutions and Civil War

During the February Revolution, Lazo arrested the governor of the Yenisei province Ya.G. Gololobov and local senior officials. In March 1917 - member of the regimental committee, chairman of the soldiers' section of the Council. In the spring of 1917, he came to Petrograd as a deputy from the Krasnoyarsk Soviet and saw V.I. for the only time in his life. Ulyanov-Lenin. Lazo really liked the radicalism of the Bolshevik leader. Returning to Krasnoyarsk, he organized a Red Guard detachment there. In October 1917 - delegate to the First All-Siberian Congress of Soviets. In October 1917, he took power in Krasnoyarsk into his own hands. The Commissioner of the Provisional Government telegraphed in those days to Petrograd:

« The Bolsheviks occupied the treasury, banks and all government offices. The garrison is in the hands of Ensign Lazo».

Participated in the suppression of the uprising of cadets in Omsk and cadets, Cossacks, officers and students in December 1917. After this, he was appointed head of the garrison and military commandant.

From the beginning of 1918 - a member of Centrosiberia, in February-August 1918 - commander of the troops of the Trans-Baikal Front. Under the command of Lazo, the red troops defeated the detachment of Ataman G.M. Semenov. At the same time, Lazo moved from the Socialist Revolutionary Party to the CPSU (b).

In the fall of 1918, after the fall of Bolshevik power in eastern Russia, he went underground and began organizing a partisan movement directed against the Provisional Siberian Government, and then the Supreme Ruler Admiral A.V. Kolchak. Since the fall of 1918, he was a member of the underground Far Eastern Regional Committee of the RCP (b) in Vladivostok. From the spring of 1919 he commanded the partisan detachments of Primorye. Since December 1919 - head of the Military Revolutionary Headquarters for the preparation of the uprising in Primorye.

One of the organizers of the coup in Vladivostok on January 31, 1920, as a result of which the power of Kolchak’s governor, the chief commander of the Amur region, Lieutenant General S.N. Rozanov, was overthrown and the Provisional Government of the Far East, controlled by the Bolsheviks, was formed - the Primorsky Regional Zemstvo Council.

The success of the uprising largely depended on the position of the officers of the ensign school on Russian Island. Lazo arrived to them on behalf of the leadership of the rebels and addressed them with a speech:

“Who are you, Russian people, Russian youth? Who are you for?! So I came to you alone, unarmed, you can take me hostage... you can kill me... This wonderful Russian city is the last one on your road! You have nowhere to retreat: then a foreign country... a foreign land... and a foreign sun... No, we did not sell the Russian soul in foreign taverns, we did not exchange it for overseas gold and guns... We are not hired, we defend our land with our own hands, we defend our land with our own breasts , we will fight with our lives for our homeland against foreign invasion! We will die for this Russian land on which I now stand, but we will not give it to anyone!”

As a result, the school of warrant officers declared its neutrality in relation to the uprising, which made the fall of Rozanov's power inevitable.

On March 6, 1920, Lazo was appointed deputy chairman of the Military Council of the Provisional Government of the Far East - the Primorsky Regional Zemstvo Council, and at about the same time - a member of the Far Bureau of the Central Committee of the RCP (b).

Arrest and death

After the Nikolaev incident, during which the Japanese garrison was destroyed, on the night of April 4-5, 1920, Lazo was arrested by the Japanese, and at the end of May 1920, Lazo and his associates and V.M. The Siberians were taken out of Vladivostok by the Japanese interventionists and handed over to the White Guard Cossacks. According to the widespread version, after torture, Sergei Lazo was burned alive in a locomotive firebox, and Lutsky and Sibirtsev were first shot and then burned in bags. However, the death of Lazo and his comrades was reported already in April 1920 by the Japanese newspaper Japan Chronicle - according to the newspaper, he was shot in Vladivostok, and the corpse was burned. A few months later, allegations appeared with reference to an unnamed driver who allegedly saw how at the Ussuri station the Japanese handed over three bags containing three people to the Cossacks from Bochkarev’s detachment. The Cossacks tried to push them into the firebox of the locomotive, but they resisted, then they were shot and stuffed dead into the firebox. In the latest edition of the History of the Russian Far East, this version of Lazo’s death is described as a legend.

Also, refutations often appear in the press and on the Internet, according to which the steam locomotive E a was placed on a pedestal. According to refutations, Lazo could not have been burned in that locomotive because such a locomotive appeared only 21 years after his death (E a locomotives were supplied from the USA to the USSR during the Second World War under Lend-Lease). However, it is not E a that was installed in Ussuriysk, but its prototype - E l, and these are two similar (especially for non-specialists) varieties of steam locomotives of the E series, in which the E a series was printed by mistake. E l steam locomotives were built by American factories in 1916-1917, a total of 475 locomotives were built. Further along the sea, these locomotives were sent to Vladivostok, from where they were already distributed throughout the country. At the end of 1922, there were 277 E-series steam locomotives on the roads of Siberia, the bulk of which were the El variety. Thus, if Lazo was burned in a steam locomotive, then it is most likely that this locomotive was precisely E l (locomotives more powerful than E were not available in Siberia at that time).

Perpetuation of memory

- After the death of S.G. Lazo station Muravyovo-Amurskaya on the Ussuri Railway, where he died, was renamed Lazo. Also in Vladivostok one of the streets is named after Sergei Lazo.

- The Bessarabian village of Piatra, where he was born, was also renamed Lazo after the region was annexed to the USSR, and after Moldova gained independence in 1991, it was again renamed Piatra.

- From 1944 to 1991, the Moldovan city of Singerei was called Lazovsk.

- In Chisinau, a monument to Sergei Lazo was erected at the intersection of Decebal and Sarmizegetusa streets.

- During the Soviet years, the Kotovsky and Lazo Museum functioned in Chisinau, but was liquidated in the 1990s.

- Lazo streets in several Moldavian cities and the Lazovsky district of the former Moldavian SSR were also renamed after the collapse of the USSR. Streets named in his honor remain in the village of Kopchak, Chadyr-Lunga district, in the village of Chok-Maidan, Comrat region of the Gagauz Autonomous Republic of Moldova, in the villages of Malayeshty, Nezavertailovka and Karagash of the Slobodzeya region in Transnistria, in Ananyev, Ulyanovsk, Bendery, Georgievsk, Vyazemsky, Chisinau, Omsk, Izmail, Belgorod-Dnestrovsky, Orenburg, Chelyabinsk, Salekhard, Samara, Stavropol, Syzran, Voronezh, Sevastopol, Taganrog, Mezhdurechensk, Tomsk, Novokuznetsk, Krasnoyarsk, Minsk, Gomel, Penza, Vitebsk, Brest, Borisov, Lipetsk, Volgograd, Kharkov, Shostka, Tver, Tambov, Tula, Blagoveshchensk, Orel, Perm, Izhevsk, Khartsyzsk, Kramatorsk, Lugansk, Enakievo, Rubtsovsk of the Altai Territory, in Adrianovka of the Trans-Baikal Territory, Borza of the Trans-Baikal Territory, in Khilka of the Trans-Baikal Territory, in St. Petersburg in the Krasnogvardeisky district and in Moscow in the Perovo region, in the city of Liski, Voronezh region, in the city of Kovrov, Vladimir region, in the city of Dnepropetrovsk, in the city of Dneprodzerzhinsk. In the city of Svobodny, Amur Region, a street and square, as well as a school and a cultural center, are named after him. In the Primorsky Territory, the village of Lazo, the Lazovsky district, the Lazovsky pass, as well as several streets in different cities and a motor ship are named after Sergei Lazo. There is also the Lazovsky district in the Khabarovsk Territory, the city of Alatyr.

- In Vladivostok, in the area of Lazo Street, a monument to Lazo was erected on the pedestal of the destroyed monument to Admiral Vasily Stepanovich Zavoiko.

- In the Srednekansky district of the Magadan region, near the village of Seymchan, there are abandoned mines, a former prison camp, still marked on maps as “named after Lazo”.

- In the Milkovsky district of the Kamchatka Territory, a village is named after Lazo.

In art

- In 1968, a feature film-biography “Sergei Lazo” was shot. Regimantas Adomaitis plays the role of Sergei Lazo.

- In 1980, the premiere of composer David Gershfeld’s opera “Sergei Lazo” took place, in which Maria Biesu performed one of the main roles.

- In 1985, the Moldova-film film studio produced a three-part feature film directed by Vasile Pascaru, “The Life and Immortality of Sergei Lazo.” The film tells about the life path of Sergei Lazo from the moment of baptism until the last minute of his life. The role of Sergei Lazo was played by Gediminas Storpirshtis.

- In the USSR, the IZOGIZ publishing house published a postcard with the image of S. Lazo.

- In 1948, a USSR postage stamp dedicated to S. Lazo was issued.

- The song “Waltz” by the rock group “Adaptation” mentions one of the versions of the death of Sergei Lazo.

Essays

- Lazo S. Diaries and letters. - Vladivostok, 1959.

Notes

- Sergey Lazo // Biografia.Ru

- Uninvented history is being returned to the Far East // BBC Russian. - August 5, 2004.

Sergei Georgievich Lazo(1894-1920) - Russian nobleman, second lieutenant of the Russian Imperial Army. During the collapse of the Russian Empire, he was a Soviet military leader and statesman who took an active part in establishing Soviet power in Siberia and the Far East, and a participant in the Civil War. In 1917 he became a Left Socialist Revolutionary, and in the spring of 1918 - a Bolshevik.

It is no coincidence that Sergei Lazo is sometimes called the Don Quixote of the revolution. He renounced his origins, everything that had been instilled in him since childhood, fought and died at the age of twenty-six, distant lands from his home - and all for ideals.

Only ideals could force a nobleman, an officer of the Imperial Army who received a good education, to rush into the abyss of revolutionary activity.

Sergei Lazo before the revolution

Sergei Georgievich Lazo was born in 1894 in Bessarabia, into a noble family of Moldavian origin. He studied at the St. Petersburg Institute of Technology and Moscow University. From an early age, he was distinguished by extreme maximalism and a desire for justice, so it is not at all surprising that during his student years he was a participant in the activities of revolutionary circles, of which there were plenty in the university environment.

In July 1916, Sergei Lazo was mobilized into the Imperial Army, and in December of the same year, Ensign Lazo was assigned to the 15th Siberian Reserve Rifle Regiment, which was stationed in Krasnoyarsk. Here, in Krasnoyarsk, Lazo became close to political exiles, joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SRs) and began, together with his party comrades, to conduct propaganda against the war among the soldiers.

In March 1917, news of the February revolution in St. Petersburg reached Krasnoyarsk. At a general meeting, the soldiers of the 4th company of the rifle regiment decided to remove from their duties Second Lieutenant Smirnov, who declared allegiance to the oath, and to elect Warrant Officer Lazo as their commander. In June, the Krasnoyarsk Council sent Sergei Lazo as a delegate to Petrograd to the First All-Russian Congress of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies. At the congress, Lazo was greatly impressed by Lenin’s speech; the ideas that were voiced by the leader of the world proletariat in this speech seemed to him even more radical, and, therefore, even more attractive to him than the ideas of the Socialist Revolutionaries. Sergei Lazo joined the Bolsheviks.

Sergei Lazo during the Civil War

At the end of 1917, Soviet power was established in Irkutsk, Omsk, and other Siberian cities, and Lazo took a direct part in this. However, already in the fall of 1918, Soviet power in Siberia fell and the dictatorship of the Supreme Ruler Admiral Kolchak was established. The Bolshevik Party goes underground.

Sergei Lazo becomes a member of the underground Far Eastern Regional Committee of the RCP (b), commands a partisan detachment of Primorye.

The Lazo detachment, like most partisan detachments during the Civil War, was very colorful. It consisted, for the most part, of the poorest proletariat, that is, from the very poor, as well as from criminals from the Chita prison, who were released by the Bolsheviks on the condition that the lads would go to fight for the world revolution.

In addition, two female commissars served in the detachment. One of them, a former high school student, daughter of the governor of Transbaikalia, is a convinced anarchist. She communicated with criminals exclusively “over a hairdryer” and famously handled a huge Mauser. The second - Olga Grabenko - was a Ukrainian beauty and a real Bolshevik. It was with her that Lazo had an affair, which ended in marriage. The young people spent their honeymoon trying to get out of the encirclement. Such are the vicissitudes of the Civil War.

Arrest of Sergei Lazo

In 1920, the Kolchak government fell. The partisans decided that the right moment had come to overthrow Kolchak’s governor, General Rozanov, in Vladivostok. And Lazo began to implement the plan.

On January 31, 1920, partisans, numbering several hundred, captured the city, primarily occupying the station, post office and telegraph office. Rozanov fled from Vladivostok. However, for some reason Lazo did not take into account the fact that Vladivostok was occupied by Japanese invaders. For the time being, they observed the events with samurai restraint, however, the famous Nikolaev incident, during which partisans and anarchists burned the city of Nikolaevsk and destroyed the Japanese garrison located in it, prompted them to action.

Lazo was arrested right in the Kolchak counterintelligence building. Together with him, two other active members of the underground, Sibirtsev and Lutsky, were arrested. They were kept there for several days, in the counterintelligence building. Then they transported it somewhere. Olga Lazo was looking for her husband, but the Japanese headquarters did not tell her where he was.

The mystery of the death of Sergei Lazo

The textbook version says that the Japanese handed Lazo, as well as Sibirtsev and Lutsky, over to the White Cossacks, and they, after torture, burned Lazo alive in a locomotive firebox, and his associates were first shot and then burned too. This was apparently told by a certain nameless driver who saw how the Japanese handed over to the Cossacks three bags in which people were fighting, and this was either at the Ruzhino station, or at Muravyevo-Amurskaya (now the Lazo station). However, this is difficult to believe for two reasons.

Firstly, why would the Japanese hand over those arrested to the Cossacks, and even drag them so far from Vladivostok? Secondly, the opening of the locomotive firebox was not large enough to push a person inside. It seems, fortunately for Lazo, such a terrible death is nothing more than a legend.

Monument to Sergei Lazo in Pereyaslavka, Khabarovsk Territory

Back in 1920, the Italian journalist Klempasco, an employee of the Japan Chronicle, reported that Lazo was shot at Cape Egersheld in Vladivostok, and his corpse was burned. Since Klempasko, and this is a documented fact, was not only a journalist, but also an intelligence officer who communicated with Japanese officers, this information has a high degree of reliability.

Lazo Sergei Georgievich, born February 23, 1894, in Bessarabia, Russian nobleman of Moldavian origin. Communist, talented organizer and leader of detachments Red Guard and the partisan movement in Siberia and on Far East during the civil war.

During the first imperialist war (1914-18) he was an officer of the 15th Siberian Regiment in the city. Krasnoyarsk, where he joined an illegal organization left SRs internationalists and conducted anti-war work among the masses of soldiers.

After February bourgeois-democratic revolution Lazo was elected by the soldiers of the 15th Infantry Regiment as a member of the Krasnoyarsk Council and served as chairman of the soldiers' section. In December 1917 Lazo led the red detachments in suppressing the counter-revolutionary cadet rebellion in Irkutsk. In February 1918 on 2nd Congress of Soviets of Siberia was elected member Centrosiberia http://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/ruwiki/699259

In 1918 Lazo commanded units Red Army And Red Guard on Transbaikal Front against the chieftain Semyonova, which was helped by the Japanese. Using the support of railway workers, miners, Transbaikal Cossacks, Lazo defeated Semyonova with his 40,000-strong army.

In 1918, after VII Party Congress, Lazo joined the Bolshevik Party. During the offensive of the White-Czechs and their occupation Irkutsk Lazo V Baikal region with a small team and an armored car, he gave a crushing rebuff to the Czech advance on the Amur.

In 1918-19 Lazo in Vladivostok, captured by the White Guards and Japanese, conducts underground work as a member Far Eastern regional party committee Spring 1919 Lazo appointed commander of all partisan detachments Primorye, is leading a successful fight against the Japanese invaders. In January 1920 Lazo led the workers' uprising in Vladivostok, acting with the combined forces of partisans Primorye and workers.

Lazo takes over Revolutionary Military Council of the Far East. In April 1920 Vladivostok Lazo together with the squad and members Revolutionary Military Council was treacherously captured by the Japanese and handed over to the White Guards, who carried out savage reprisals against all of them.

Sergei Georgievich Lazo was burned alive in the locomotive firebox at the station Muravyovo-Amurskaya(now a station named after Sergei Lazo)

Lazo enjoyed enormous prestige among the working masses and acquired the legendary fame of a hero of the civil war in Far East.

But what kind of future do modern Russian elites have, allowing them to erect monuments to the White Czech invaders, Nazi collaborators who plundered the country and committed genocide of the Russian people, I don’t know? I think if they are able to listen to examples from the history of their country, then the lines below should give them pause. If not, then woe to the losers.

“I heard these stories near Akkerman, in Bessarabia, on the seashore. One evening...” http://www.litmir.co/br/?b=10494&p=1

Perhaps in childhood I also heard this legend and it forever determined his life’s path to immortality.

He was far from the only representative of the upper classes of the royal Russia those who, guided by the understanding that the existing elites are not able to take responsibility for the future of the country and people, do not have their own project, a vision of the future compatible with the life of the country, have lost everything and are going down in history as a relic of the past.

And some, like the prince Alexander Romanov were irreconcilable enemies of the Bolsheviks*, because there was blood between them, but they also recognized that the actions of the Bolsheviks had a future and were being done in their interests Motherland, which they could not do.