The 13th century in the history of Rus' began without any special external shocks, but in the midst of endless internal strife. The princes divided the lands and fought for power. But soon the internal troubles of Rus' were joined by danger from the outside. Cruel conquerors from the depths of Asia under the leadership of Temujin (Genghis Khan - that is, the Great Khan) began their actions. The armies of the nomadic Mongols mercilessly destroyed people and conquered lands. Soon, the Polovsk khans asked for help from the Russian princes. And they agreed to oppose the approaching enemy. So, in 1223 a battle took place on the river. Kalke. But due to the fragmented actions of the princes and the lack of a unified command, the Russian warriors suffered heavy losses and left the battlefield. The Mongol troops pursued them to the very outskirts of Rus'. Having plundered and devastated them, they moved no further. In 1237, the troops of Temuchin’s grandson, Batu, entered the Ryazan principality. Ryazan fell. The conquests continued. In 1238 on the river. The city army of Yuri Vsevolodovich entered into battle with the invader’s army, but turned out in favor of the Tatar-Mongols. At the same time, the South Russian princes and Novgorod remained on the sidelines and did not come to the rescue. In 1239 – 1240 Having replenished the army, Batu undertook a new campaign against the Russian lands. At this time, the unaffected northwestern regions of Rus' (Novgorod and Pskov lands) were endangered by the crusading knights who had settled in the Baltic states. They wanted to force people to accept the Catholic faith on the territory of Rus'. United by a common idea, the Swedes and German knights were about to unite, but the Swedes were the first to act. In 1240 (July 15) - Battle of the Neva - the Swedish fleet entered the mouth of the river. Not you. The Novgorodians turned to the Great Prince of Vladimir Yaroslav Vsevolodovich for help. His son, the young prince Alexander, immediately set off with his army, counting on the surprise and speed of the onslaught (the army was inferior in number, even with the Novgorodians and commoners who had joined). Alexander's strategy worked. In this battle, Rus' won, and Alexander received the nickname Nevsky. Meanwhile, the German knights gained strength and began military operations against Pskov and Novgorod. Again Alexander came to the rescue. April 5, 1242 - Battle of the Ice - troops converged on the ice of Lake Peipsi. Alexander won again, thanks to a change in the formation order and coordinated actions. And the knights’ uniforms played against them; when they retreated, the ice began to break. In 1243 - Formation of the Golden Horde. Formally, the Russian lands were not part of the newly formed state, but were subject lands. That is, they were obliged to replenish its treasury, and the princes had to receive labels for reigning at the khan’s headquarters. During the second half of the 13th century, the Horde more than once made devastating campaigns against Rus'. Cities and villages were ruined. 1251 - 1263 - reign of Alexander Nevsky. Due to the invasions of conquerors, during which settlements were robbed and destroyed, many cultural monuments of Ancient Rus' from the 10th to 13th centuries also disappeared. Churches, cathedrals, icons, as well as works of literature, religious objects and jewelry remained intact. The basis of ancient Russian culture is the heritage of the East Slavic tribes. It was influenced by nomadic peoples, the Varangians. The adoption of Christianity, as well as Byzantium and the countries of Western Europe, significantly influenced. The adoption of Christianity influenced the spread of literacy, the development of writing, education and the introduction of Byzantine customs. This also influenced the clothing of the 13th century in Rus'. The cut of the clothes was simple, and they differed mainly in fabric. The suit itself has become longer and looser, not emphasizing the figure, but giving it a static look. The nobility wore expensive foreign fabrics (velvet, brocade, taffeta, silk) and furs (sable, otter, marten). Ordinary people used canvas fabric, hare fur, squirrels, and sheepskin for clothing.

The table “Main events in the history of Ancient Rus' in the 9th – early 13th centuries” compiled by students based on materials from the textbook will probably look like this.

Main events in the history of Ancient Rus' in IX – beginning XIII century

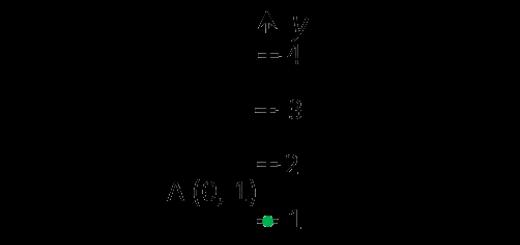

Year | Internal political events | Foreign policy events |

Beginning of Rurik's reign in Novgorod | ||

Prince Oleg's campaign against Kyiv. Unification of the north (Novgorod) and south (Kyiv). Formation of the Old Russian State | ||

Campaigns of Prince Oleg to Constantinople (Constantinople). Signing a trade agreement beneficial for Rus' |

||

Unsuccessful campaigns of Prince Igor against Constantinople |

||

Prince Igor is killed by the rebel Drevlyans | ||

The campaign of Prince Svyatoslav against the Khazar Kaganate. The defeat and death of the Khazar Kaganate. Russian control over the Volga trade route |

||

Embassy of Rus' in Constantinople. Baptism of Princess Olga. Political union of Rus' and Byzantium |

||

Russian-Byzantine War. Death of Prince Svyatoslav |

||

Adoption of Christianity in Rus' under Prince Vladimir | ||

Lyubech Congress of Princes. Legal formalization of political fragmentation | ||

The defeat of the Polovtsians by Prince Vladimir Monomakh |

||

The assault and defeat of Kyiv by the united troops of the Russian princes and Polovtsian khans. Weakening of the all-Russian significance of Kyiv |

Lessons No. 14-15. Rus' between East and West.

During the lessons:

reveal the process of formation of the Mongolian state, noting the features in comparison with the Old Russian state;

determine the reasons for the military successes of the Mongols during the formation of the Mongol Empire;

note the role of Rus'’s struggle against the Mongol invasion for medieval European civilization;

characterize the significance of Rus'’s struggle against the German and Swedish invaders;

draw conclusions about the significance of the choice of the princes of North-Eastern Rus' in favor of an alliance with the Horde against the Catholic West.

Lesson Plan:

The formation of the Mongol state and its conquests.

Mongol invasion of Eastern and Central Europe.

Mongol power in the 13th century.

Rus' under the rule of the Golden Horde.

Rus' between the West and the Horde.

Means of education: textbook §12-13, historical map No. 7 “Russian lands in the 12th – early 13th centuries.”

Recommended methods and techniques for conducting lessons: independent work of students with the text of the textbook, a historical map with elements of a generalizing characteristic, solving cognitive tasks, work on compiling a table “Rus’ fight against the invasion of the Mongols and repelling the aggression of the West.”

Personalities: Genghis Khan, Batu, Alexander Nevsky.

Key dates: 1223 – battle on the Kalka River.

1237-1242 - Batya’s invasion of Rus'.

1240 – Battle of the Neva.

Questions for review:

Reveal the reasons for political fragmentation in Rus'.

Prove that the period of political fragmentation was accompanied by the economic and cultural rise of the Russian lands.

Compare the development of the Novgorod land and the Vladimir-Suzdal principality, from the point of view of natural, economic, social and political features.

Describe the activities of Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky. Why did his contemporaries call him “autocratic”?

Two lessons are allocated to study the topic. It is advisable to focus on the first three points of the lesson plan in the first lesson. The second lesson will be devoted to characterizing the most difficult issue - Rus' under the rule of the Golden Horde and the problem of choosing the princes of North-Eastern Rus' for civilizational development.

Option #1 . Since a significant part of the material in the paragraph is event-based and is largely familiar to students, the first lesson organizes independent work for students with the text of the textbook and map No. 7 to prepare answers to questions. In order to save time during the lesson, work in groups is possible.

Comparative characteristics of state formation among the Mongols and Eastern Slavs.

Reasons for the successful conquests of the Mongols.

Batya's invasion of Rus' and its consequences.

Rus' between East and West.

Work on the first issue will make it possible to repeat the process of formation of the Old Russian state and, on this basis, note the main feature of the Mongol state - “nomadic feudalism”, in which the main value was cattle. It is better to entrust this question to the most prepared group of students, since comparative analysis is quite complex. The last question of the assignment is completed by students and discussed in the second lesson.

Reference point! Many different points of view have been expressed in Russian science regarding the historical development of nomadic societies. There was a discussion among historians about “ nomadic feudalism" Some scientists believed that nomads developed according to the same laws as agricultural peoples, and the basis of their feudal relations was land ownership(pastures). Their opponents argued that the pastures of the nomads were collectively owned, and the basis of feudalism was livestock ownership.

Option #2. After a conversation with the class about the formation of the Mongolian state and the reasons for the successful conquests of the Mongols led by Genghis Khan, students conduct independent work with the text of the textbook, map No. 7 (task No. 1, p. 93). During the work, the table “Rus’ Struggle against the Mongol Invasion and Reflecting Western Aggression” is filled in, followed by a discussion of the results. In the process of this work, it is necessary to use document analysis of task No. 2 of the textbook.

date | Who did you fight with? | Events | Result |

Mongol power | The Polovtsians turned to the Russian princes for help. The united Russian-Polovtsian army and the Mongols met in a decisive battle near the Kalka River. | The military superiority of the Mongols, disagreements among the Russian princes, and the unexpected flight of the Polovtsians led to a terrible defeat for the Russian squads. |

|

December 1237 | Invasion of the Mongol army led by Khan Batu. | Defeat of the troops of the Ryazan prince at the borders of the principality. Capture of the city of Ryazan. | Other principalities did not provide assistance to the Ryazan residents. The defeat of the Ryazan principality. |

January 1238 | The battle of the Vladimir-Suzdal troops with the Mongols near Kolomna. | Defeat of the Vladimir-Suzdal troops. Siege of Vladimir by the Mongols. |

|

February 1238 | The assault and capture of Vladimir by the Mongols. | Another 14 cities of North-Eastern Rus' were taken by the Mongols. |

|

March 1238 | Defeat of Vladimir troops on the City River. | Most of the Russian soldiers and Grand Duke Yuri Vsevolodovich died. Before reaching Novgorod, the Mongols turned to the steppe. |

|

April 1238 | The siege of the city of Kozelsk lasted 7 weeks. "Evil City" | Only by the beginning of summer did the Mongols manage to break out into the southern steppes. |

|

Autumn 1239 | Devastation of the lands and principalities of Southern Rus'. | Invasion of Poland and Hungary. |

|

The Swedish fleet along the Neva invaded the Novgorod possessions. Defeat of the Swedes on the Neva from the Novgorod prince Alexander Yaroslavich (Nevsky). | The Swedes failed to block the trade route along the Baltic for the Novgorodians. |

||

Livonian Order | "Battle on the Ice". | The regiments of Alexander Nevsky inflicted a crushing defeat on the knights on the ice of Lake Peipsi. |

Question. Prove that the soldiers and residents of Rus' offered fierce resistance to the invaders.

As homework, you can ask tenth graders to supplement the textbook material with historical facts and examples. For the purpose of preliminary familiarization, students at home become familiar with the textbook material on the issues of “Rus under the rule of the Golden Horde” and “Rus between the Mongols and the West.”

In the second lesson, during the conversation, conclusions are analyzed and conclusions are drawn about the consequences of the Mongol invasion of Rus' and the significance of the choice of the princes of North-Eastern Rus' in favor of an alliance with the Horde against the Catholic West.

What consequences did the Mongol invasion have for Rus'?

Economic, social and cultural lag of Rus' from the countries of Western Europe.

Heavy material damage, massive loss of life, destruction of cities. Decline of crafts, trade, cities.

Students should pay attention to the fact that this is the third factor holding back the development of the country. Remember, what other factors hampered the development of Rus' and determined its lag behind the countries of Western Europe? Schoolchildren, answering this question, should name the natural-geographical factor (see §6, pp. 44 and 46) and the absence during the formation of the Old Russian state, unlike the countries of Western Europe, on the territory of a highly developed civilization in ancient times, the inability to directly use the achievements of ancient civilization (see §8, p. 59).

The military defeat delayed the political unification of the northeastern lands.

Relations between Russian lands and Orthodox countries and European countries ceased.

Contributed to the development of despotic forms of power in Rus'.

A different point of view! What positive aspects of the dependence of the northeastern principalities on the Golden Horde were noted by the historian V.O. Klyuchevsky? “In the devastated public consciousness (of the North-Eastern princes) there was only room left for the instincts of self-preservation and conquest. Only the image of Alexander Nevsky somewhat covered up the horror of savagery and fraternal bitterness that too often erupted among Russian rulers, relatives or cousins, uncles and nephews. If they had been left completely to their own devices, they would have torn their Rus' apart into incoherent, eternally warring patches of appanages. But the principalities of the then Northern Rus' were not independent possessions, but tributary “uluses” of the Tatars; their princes were called the slaves of the “free king,” as we called the Horde Khan. The power of this khan gave at least a ghost of unity to the smaller and mutually alienated patrimonial corners of the Russian princes. True, it was in vain to look for rights in the Volga Sarai. The Grand Duke's Vladimir table was the subject of bargaining and rebidding there; the Khan's purchased label covered all untruths. But the offended one did not always immediately grab his weapon, but went to seek protection from the khan, and not always unsuccessfully. The thunderstorm of the khan's wrath restrained the bullies; By mercy, that is, by arbitrariness, devastating strife was more than once prevented or stopped. The power of the khan was a rough Tatar knife, cutting the knots with which the descendants of Vsevolod III knew how to entangle the affairs of their land. It was not in vain that the Russian chroniclers called the filthy Hagarians the batog of God, admonishing sinners in order to lead them to the path of repentance.”

How was Rus''s dependence on the Golden Horde manifested?

The Khan of the Golden Horde appointed great princes. All princes had to receive from the khan shortcuts to own their lands. Contributed to the development of despotic forms of power in Rus'.

Dependence on the Golden Horde preserved political fragmentation.

Payment of tribute - "Tatar" exit" Population census, tribute collection standards established. Made it difficult to restore and develop the economy of the northeastern lands.

Administration of the Horde in the Russian principalities (until the middle of the 14th century) – Baskaki.

Punitive raids of the Golden Horde, during which the Horde took artisans and young people into slavery. Decline of crafts, trade, cities.

Was North-Eastern Rus' part of the Golden Horde?

From the point of view of the text of the textbook, North-Eastern Rus' became dependent on the Golden Horde, that is, it had “autonomy” - “the conquerors retained the system of government that had developed here, the army and religion.” However, in the “let’s summarize” section it is said that North-Eastern Rus' found itself “within the framework of the emerging Mongol Empire.” The complete personal dependence of the princes on the Mongol Khan, who gave them the right to govern their own territories, confirmation of this dependence by regular “exits”, the supply of troops for joint military operations, the presence of the Horde administration (Baskaki), can hardly serve as a valid basis for the recognition of “autonomy” » Russian lands within the Golden Horde (ulus of Jochi).

Solutiondilemmas (see page 91)(i.e., a difficult choice between two equally unpleasant possibilities) princes. The solution to the dilemma by Prince Alexander Nevsky.

1 point of view. The prudent policy of Alexander Nevsky, who understood the futility of resistance to the Mongols, based on the alliance and subordination of Odra, relying on the help of the Mongol khans against the Catholic West, allowed him to maintain his own statehood.

2 point of view. Relying on the help of the Mongol khans, Alexander Nevsky consolidated the despotic traditions of governing North-Eastern Rus'. At the same time, he actually put an end to the effective resistance of the Russian princes to the Golden Horde for many years to come.

Lesson #16. Final repetition and generalization historical material in Chapter 2 is carried out using questions and tasks proposed in the textbook (pp. 93-94). The volume of oral and written work, the form of conducting the final repetition and generalization lesson are determined by the teacher, based on the level of preparation and other characteristics of a particular class. The organization of work in this lesson can be built using various techniques and forms - a seminar, a test lesson, writing a micro-essay (see Thematic planning).

Questions for final repetition and generalization:

The influence of natural and geographical conditions on the formation and development of Ancient Rus'.

Highlight and justify the features of the emergence and development of the state among the Eastern Slavs.

Reveal the main periods of political development of Ancient Rus' in the 10th – 13th centuries.

Describe ancient Russian society and its main groups.

Determine the features of the development of the culture of Ancient Rus' of this period.

Why do scientists call this period of development of Ancient Rus' the pre-Mongol period? What changed in Rus' as a result of the invasion of the Mongols led by Batu Khan?

Tests:

1). The Eastern Slavs were characterized by an economic and cultural type

Nomadic pastoralists;

Farmers and settled pastoralists;

Nomadic pastoralists.

2). On the eve of the formation of the state, the worldview of the Eastern Slavs was

Pagan;

Not religious;

3). Read an excerpt from the work “Strategikon” and determine the social system of the Eastern Slavs.

“They do not hold those in captivity in slavery, like other tribes, for an unlimited time, but, limiting (the period of slavery) to a certain time, they offer them a choice: whether they want to return home for a certain ransom or remain there as free men ?

Slaveholding;

Feudal;

Tribal.

4). Most Russian epics are associated with the name:

Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich;

Prince Svyatopolk the Accursed;

Prince Igor Svyatoslavich.

5). What event in Russian history happened in 882?

Calling to the reign of Rurik;

The death of Prince Igor from the Drevlyans;

Prince Oleg's campaign against Kyiv.

6). Which of the named events occurred later than all the others?

Baptism of Rus';

Prince Oleg's campaign against Constantinople;

The death of Prince Igor as a result of the Drevlyan uprising.

7). The consequence of the adoption of Christianity by Russia was

Acquaintance with the heritage of antiquity;

The split of Russian society along religious lines.

8). Who owns the words mentioned in the chronicle? “If anyone does not come to the river tomorrow - be it rich, or poor, or beggar, or slave - he will be my enemy.”

Prince Yaroslav the Wise;

Prince Alexander Nevsky;

Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich.

9). The event to which the phrase “let each one keep his homeland” refers occurred in

1. 1097; 2. 1113; 3. 1237.

10). Hereditary land ownership in medieval Rus' is called:

1. Patrimony; Rope; Pogost.

eleven). The code of laws of Ancient Rus' was called:

"Salic truth";

"Russian Truth";

"Ladder".

12). Servants, procurement, serf in Ancient Rus' belonged to

Dependent population;

To the free population;

Noble population.

13). Which of the main groups of the population of the Old Russian state belongs to the article in “Russian Truth”?

“If __________ hits a free man and runs away to the mansion, ... and after that, if ________ is found anywhere by the man he has beaten, let him kill him like a dog.”

14). Establish a correspondence between the genres of ancient Russian literature and the titles of works.

A). “The Word” 1. “The Tale of Boris and Gleb”

B). Life 2. “The Tale of Bygone Years”

B) Chronicle 3. “Teaching” of Vladimir Monomakh.

15). Read an excerpt from the chronicle and determine which event the information contained in it relates to.

“Why are we destroying the Russian land, creating hostility against ourselves, while the Polovtsians are tearing our land apart and rejoicing that there are wars between us to this day. From now on, we will unite into one heart and protect the Russian lands. Let everyone keep his homeland..." and on that they kissed the cross... and having taken an oath, they went home..."

16). Establish a correspondence between concepts and their definitions.

A). Expansion 1. Tour of the lands subject to Kyiv by the prince and his squad from

for the purpose of collecting tribute.

B). Heresy 2. Expansion, capture of new territories.

IN). Patrimony 3. A creed different from the religious system

ideas recognized by the church.

G). Polyudye 4. Hereditary land ownership in medieval Rus'.

17). Read an excerpt from the historian’s work and determine which of the 12th-century princes it was dedicated to.

“Having not only a kind heart, but also an excellent mind, he clearly saw the cause of state disasters and wanted to save at least his region from them: that is, he abolished the unfortunate system of appanages, reigned autocratically and did not give cities to either his brothers or sons...”

Key to test tasks:

Lyubech Congress | Andrey Bogolyubsky |

Topic 3. Western Europe in the XI-XV centuries

The material on this topic gives an idea of the formation of the foundations of European civilization. The historical material of the textbook chapter examines important problems of economic (urban development, small-scale craft production), political (formation of centralized states) and social (bourgeois and the formation of new bourgeois values) processes in the countries of medieval Europe. The historical material of the chapter, which is insignificant in volume, is important from the point of view of studying similar processes in Russia and for determining the features and differences that are similar, but only at first glance, in the directions of historical development of medieval Russia and Western countries.

Lesson #17. Economic and political development.

During the lesson:

note important changes in the economic life of medieval society in Western Europe and their consequences for the rapid development of cities;

analyze the cause-and-effect relationship between the processes of economic recovery, the transformation of townspeople into an influential political force in medieval society and the formation of centralized states in Western Europe;

give a comparative description of the strengthening of royal power and the creation of centralized states using the examples of France and England;

characterize the weakening of the power of popes over secular monarchs, the growth of heretical movements in Europe.

Means of education: textbook §14.

The Russian state, formed on the border of Europe and Asia, which reached its peak in the 10th - early 11th centuries, has always been distinguished by its mentality: unity, strength and courage. The people have always stood united against the enemy. But at the beginning of the 12th century, as a natural stage in the development of the country, it broke up into many principalities during feudal fragmentation. The reason for this was, firstly, the feudal mode of production, and, secondly, the formation of almost independent politics, economics and other spheres of individual principalities. Communication between the princes almost ceased, the lands became isolated. The external defense of the Russian land was especially weakened. Now the princes of individual principalities pursued their own separate policies, considering primarily the interests of the local feudal nobility and entered into endless internecine wars. This led to the loss of centralized control and to a severe weakening of the state as a whole. It was during this period that the Mongol-Tatars invaded the Russian lands, unprepared for a long and strong confrontation with their opponents.

Prerequisites for the Tatar campaign against Rus'

At the kurultai 1204 – 1205. The Mongols were given the task of conquering world domination. Northern China was already in the hands of the Mongols. Having won and realizing their military power, they wanted more significant conquests and victories. And now, without stopping or leaving the marked path, they walked west. Soon, after certain events, their military mission was more clearly defined. The Mongols decided to conquer large and rich, as they believed, Western countries, and primarily Rus'. They understood that in order to accomplish this task, they first needed to take the small, weak peoples located near Rus' and on its borders. So what were the main prerequisites for the Mongol-Tatars’ campaign against Rus' and further to the west?

Battle of Kalka

Moving west, in 1219 the Mongols first defeated the Central Asian Khorezmians, then advanced into Northern Iran. In 1221, Genghis Khan's army, led by his best commanders Jebe and Subede, invaded Azerbaijan and then received orders to cross the Caucasus. Pursuing their long-time enemies the Alans (Ossetians), who were hiding among the Polovtsians, both commanders had to hit the latter and return home, bypassing the Caspian Sea.

In 1222, the Mongol army moved into the lands of the Polovtsians. The Battle of the Don took place, in which their army defeated the main forces of the Polovtsians. At the beginning of 1223, she invaded Crimea, where she captured the ancient Byzantine city of Surozh (Sudak). The Polovtsians fled to Rus' to ask for help. But the Russian princes did not trust their old opponents and greeted their request with doubt. And they perceived the appearance of a new Mongol army on the border of Rus' as another weak horde of nomads emerging from the steppe. Therefore, only a small part of the Russian princes came to the aid of the Polovtsians. A small but strong Russian-Polovtsian army was formed, ready to defeat the unprecedented Mongol army.

On May 31, 1223, the Russian-Polovtsian army reached the Kalka River. There they were met by a powerful onslaught of Mongol cavalry. Already at the beginning of the battle, some of the Russians could not resist the skilled Mongol archers and ran. Even the frantic onslaught of Mstislav the Udal’s squad, which almost broke through the Mongol battle lines, ended in failure. The Polovtsian troops turned out to be very unstable in battle: the Polovtsians could not withstand the blow of the Mongol cavalry and fled, disrupting the battle formations of the Russian squads. Even one of the strongest Russian princes, Mstislav of Kiev, never entered into battle with his numerous and well-armed regiment. He died ingloriously, surrendering to the Mongols who surrounded him. The Mongol cavalry pursued the remnants of the Russian squads to the Dnieper. The remaining part of the Russian-Polovtsian squad tried to fight to the last. But ultimately the Mongol army was victorious. The Russian warriors were cut to pieces. The Mongols themselves placed the princes under a wooden platform and crushed them, holding a festive banquet on it.

Russian losses in the battle were very high. The Mongolian army, already exhausted by battles in Central Asia and the Caucasus, was able to defeat even the selected Russian regiments of Mstislav the Udal, which speaks of its military strength and power. At the Battle of Kalka, the Mongols first encountered Russian methods of warfare. This battle showed the superiority of Mongolian military traditions over European ones: collective discipline over individual heroism, trained archers over heavy cavalry and infantry. These tactical differences became the key to Mongol success on Kalka, and subsequently to the lightning-fast conquest of Eastern and Central Europe.

For Rus', the battle on Kalka turned into a catastrophe, “which has never happened before.” The historical center of the country - the southern and central Russian lands - lost their princes and troops. Fifteen years before the start of the Mongol invasion of Rus', these territories were never able to restore their potential. The battle turned out to be a harbinger of the difficult times that befell Kievan Rus during the Mongol invasion.

Kurultai 1235

In 1235, the Mongols held another kurultai, at which they decided on a new campaign of conquest in Europe, “to the last sea.” After all, according to their information, Rus' was located there, and it was famous for its numerous riches.

All of Mongolia began to prepare for a new grandiose campaign of conquest to the West. The army was carefully prepared. The best military leaders, a number of Mongol princes, were involved. A new khan, Genghis Khan’s son Jochi, was placed at the head of the campaign. But in 1227 they both died, so the campaign to Europe was entrusted to Jochi’s son, Batu. The new Great Khan Udegei sent troops from Mongolia to reinforce Batu under the command of one of the best commanders - the wise old Subede, who participated in the battle of Kalka, to conquer Volga Bulgaria and Rus'. As always, Mongolian intelligence was at the highest level. With the help of merchants who traded along the Great Silk Road (from China to Spain), all the necessary information was collected about the state of Russian lands, about the routes leading to the cities, about the size of the Russian army, and much other information. After which it was decided to first completely defeat the Polovtsy and Volga Bulgars in order to secure the rear, and then attack Rus'.

Hike to north-eastern Rus'. On the way to Rus'

The Mongol-Tatars headed towards the southeast of Europe. In the fall of 1236, their main forces, which came from Mongolia, united with the Jochi troops sent to help within Bulgaria. In the late autumn of 1236, the Mongols began its conquest. “The same autumn,” as the Laurentian Chronicle says, “the godless Tatars came from the eastern countries to the Bulgarian land, and took the glorious Great Bulgarian city and beat with weapons from the old man to the old man and to the mere infant, and took a lot of goods, and burned their city fire, and took their whole land into captivity.” Eastern sources also report the complete defeat of Bulgaria. Rashid ad-Din (“In that winter”) writes that the Mongols “reached the city of Bulgar the Great and its other regions, defeated the local army and forced them to submit.” Volga Bulgaria was terribly devastated. Almost all of its cities were destroyed. Rural areas were also subjected to massive devastation. In the basin of the Berda and Aktai rivers, almost all settlements were destroyed.

By the spring of 1237, the conquest of Volga Bulgaria was completed. A large Mongol army led by Subede moved to the Caspian steppes, where the war with the Cumans, which began in 1230, continued.

The first blow in the spring of 1237 was dealt by the Mongols to the Cumans and Alans. From the Lower Volga, Mongol troops moved “in a raid, and the country that fell into it was captured, marching in formations.” The Mongol-Tatars crossed the Caspian steppes on a wide front and united somewhere in the Lower Don region. The Polovtsians and Alans suffered a strong, crushing blow.

The next stage of the war of 1237 in South-Eastern Europe was an attack on the Burtases, Mokshas and Mordovians. The conquest of the Mordovian lands, as well as the lands of the Burtases and Ardzhans, ended in the autumn of that year.

The campaign of 1237 was intended to prepare a springboard for the invasion of North-Eastern Rus'. The Mongols dealt a strong blow to the Polovtsians and Alans, pushing the Polovtsian nomads to the west, beyond the Don, and conquered the lands of the Burtases, Mokshas and Mordovians, after which preparations began for the campaign against Rus'.

In the autumn of 1237, the Mongol-Tatars began preparations for a winter campaign against North-Eastern Rus'. Rashid ad-Din reports that “in the autumn of the mentioned year (1237) all the princes who were there organized a kurultai and, by general agreement, went to war against the Russians.” This kurultai was attended by both the Mongol khans, who destroyed the lands of the Burtases, Mokshas and Mordovians, and the khans who fought in the south with the Polovtsians and Alans. All the forces of the Mongol-Tatars gathered for a campaign against North-Eastern Rus'. The place of concentration of Mongol troops in the fall of 1237 was the lower reaches of the Voronezh River. Mongol troops who had ended the war with the Polovtsians and Alans arrived here. The Tatars were ready for an important and complex offensive against the Russian state.

Hike to the northeast of Rus'

In December 1237, Batu's troops appeared on the frozen rivers Sura, Voronezh, a tributary of the Volga and Don. Winter opened the way for them along the ice of rivers to North-Eastern Rus'.

“An unheard-of army has come, the godless Moabites, and their name is Tatars, but no one knows who they are and where they came from, and what their language is, and what tribe they are, and what their faith is. And some say Taurmen, and others say Pechenegs.” With these words begins the chronicle of the Mongol-Tatar invasion of Russian soil.

Ryazan land

At the beginning of the winter of 1237, the Mongol-Tatars moved from the Voronezh River along the eastern edge of the forests stretching in its floodplain to the borders of the Ryazan principality. Along this path, covered by forests from the Ryazan guard posts, the Mongol-Tatars silently walked to the middle reaches of Lesnoy and Polny Voronezh. But they were noticed there by Ryazan patrols and from that moment came to the attention of Russian chroniclers. Another group of Mongols also approached here. Here they stayed for quite a long time, during which the troops were arranged and prepared for the campaign.

Russian troops could do nothing to oppose the strong Mongol troops. Strife and strife between the princes did not allow united forces to be deployed against Batu. The princes of Vladimir and Chernigov refused to help Ryazan.

Approaching the Ryazan land, Batu demanded from the Ryazan princes a tenth of everything that was in the city. In the hope of reaching an agreement with Batu, the Ryazan prince sent an embassy to him with rich gifts. The Khan accepted the gifts, but put forward humiliating and arrogant demands: in addition to the huge tribute, he should give the prince’s sisters and daughters as wives to the Mongolian nobility. And for himself personally, he set his sights on the beautiful Eupraksinya, Fedor’s wife. The Russian prince responded with a decisive refusal and, together with the ambassadors, was executed. And the beautiful princess, together with her little son, so as not to fall to the conquerors, threw herself down from the high bell tower. The Ryazan army moved to the Voronezh River to strengthen the garrisons on the fortified lines and prevent the Tatars from going deep into the Ryazan land. However, the Ryazan squads did not have time to reach Voronezh. Batu quickly invaded the Ryazan principality. Somewhere on the outskirts of Ryazan there was a battle between the united Ryazan army and the hordes of Batu. The battle, in which the Ryazan, Murom and Pron squads took part, was stubborn and bloody. 12 times the Russian squad came out of encirclement, “one Ryazan man fought with a thousand, and two with darkness (ten thousand)” - this is what the chronicle writes about this battle. But Batu had a great superiority in strength, and the Ryazan army suffered heavy losses.

After the defeat of the Ryazan squads, the Mongol-Tatars immediately moved deeper into the Ryazan principality. They passed through the space between Ranova and Pronya, and went down the Prony River, destroying the Pronian cities. On December 16, the Mongol-Tatars approached Ryazan. The siege has begun. Ryazan held out for 5 days, on the sixth day, on the morning of December 21, it was taken. The entire city was destroyed and all the inhabitants were exterminated. The Mongol-Tatars left only ashes behind them. The Ryazan prince and his family also died. The surviving inhabitants of the Ryazan land gathered a squad (about 1,700 people), led by Evpatiy Kolovrat. They caught up with the enemy in Suzdal and began to wage guerrilla warfare against him, inflicting heavy losses on the Mongols.

Principality of Vladimir

Now in front of Batu lay several roads into the depths of the Vladimir-Suzdal land. Since Batu was faced with the task of conquering all of Rus' in one winter, he headed to Vladimir along the Oka, through Moscow and Kolomna. The invasion moved close to the borders of the Vladimir principality. Grand Duke Yuri Vsevolodovich, who at one time refused to help the Ryazan princes, himself found himself in danger.

“And Batu went to Suzdal and Vladimir, intending to captivate the Russian land, and eradicate the Christian faith, and destroy the churches of God to the ground,” - this is how the Russian chronicle writes. Batu knew that the troops of the Vladimir and Chernigov princes were coming towards him, and expected to meet them somewhere in the Moscow or Kolomna region. And he turned out to be right.

The Laurentian Chronicle writes this way: “The Tatars surrounded them at Kolomna and fought hard, there was a great battle, they killed Prince Roman and the governor Eremey, and Vsevolod with a small squad ran to Vladimir.” The Vladimir army died in this battle. Having defeated the Vladimir regiments near Kolomna, Batu approached Moscow, quickly took and burned the city in mid-January, and killed the inhabitants or took them prisoner.

On February 4, 1238, the Mongol-Tatars approached Vladimir. The capital of North-Eastern Rus', the city of Vladimir, surrounded by new walls with powerful stone gate towers, was a strong fortress. From the south it was covered by the Klyazma River, from the east and north by the Lybid River with steep banks and ravines.

By the time of the siege, a very alarming situation had developed in the city. Prince Vsevolod Yuryevich brought news of the defeat of the Russian regiments near Kolomna. New troops had not yet gathered, and there was no time to wait for them, since the Mongol-Tatars were already close to Vladimir. Under these conditions, Yuri Vsevolodovich decided to leave part of the collected troops for the defense of the city, and go north himself and continue collecting troops. After the departure of the Grand Duke, a small part of the troops remained in Vladimir, led by the governor and the sons of Yuri - Vsevolod and Mstislav.

Batu approached Vladimir on February 4 from the most vulnerable side, from the west, where a flat field lay in front of the Golden Gate. The Mongol detachment, leading Prince Vladimir Yuryevich, who was captured during the defeat of Moscow, appeared in front of the Golden Gate and demanded the voluntary surrender of the city. After the refusal of the Vladimir people, the Tatars killed the captured prince in front of his brothers. To inspect the fortifications of Vladimir, part of the Tatar detachments traveled around the city, and Batu’s main forces camped in front of the Golden Gate. The siege began.

Before the assault on Vladimir, the Tatar detachment destroyed the city of Suzdal. This short hike is quite understandable. Beginning the siege of the capital, the Tatars learned about Yuri Vsevolodovich’s exit from the city with part of the army and feared a sudden attack. And the most likely direction of the Russian prince’s attack could be Suzdal, which covered the road from Vladimir to the north along the Nerl River. Yuri Vsevolodovich could rely on this fortress, which was located only 30 km from the capital.

Suzdal was left almost without defenders and was deprived of its main water cover due to winter time. That is why the city was taken by the Mongol-Tatars immediately. Suzdal was plundered and burned, its population was killed or taken prisoner. Settlements and monasteries in the vicinity of the city were also destroyed.

At this time, preparations for the assault on Vladimir continued. To intimidate the city’s defenders, the conquerors held thousands of prisoners under the walls. On the eve of the general assault, the Russian princes who led the defense fled from the city. On February 6, the Mongol-Tatar battering machines broke through the Vladimir walls in several places, but on that day the Russian defenders managed to repel the assault and did not allow them into the city.

The next day, early in the morning, the Mongol-Tatar battering guns finally broke through the city wall. A little later, the fortifications of the “New City” were broken through in several more places. By the middle of the day on February 7, the “New City,” engulfed in fire, was captured by the Mongol-Tatars. The defenders who survived fled to the middle, “Pecherny city”. Pursuing them, the Mongol-Tatars entered the “Middle City”. And again, the Mongol-Tatars immediately broke through the stone walls of the Vladimir castle and set it on fire. It was the last stronghold of the defenders of the Vladimir capital. Many residents, including the princely family, took refuge in the Assumption Cathedral, but the fire overtook them there too. The fire destroyed the most valuable monuments of literature and art. Numerous temples of the city turned into ruins.

The fierce resistance of the defenders of Vladimir, despite the significant numerical superiority of the Mongol-Tatars and the flight of the princes from the city, caused great damage to the Mongol-Tatars. Eastern sources, reporting the capture of Vladimir, create a picture of a long and stubborn battle. Rashid ad-Din says that the Mongols “took the city of Yuri the Great in 8 days. They (the besieged) fought fiercely. Mengu Khan personally performed heroic feats until he defeated them.”

Trek deep into Rus'

After the capture of Vladimir, the Mongol-Tatars began to destroy the cities of the Vladimir-Suzdal land. This stage of the campaign is characterized by the death of most cities between the Klyazma and Upper Volga rivers.

In February 1238, the conquerors moved from the capital in several large detachments along the main river and trade routes, destroying urban centers of resistance.

The campaigns of the Mongol-Tatars in February 1238 were aimed at the destruction of cities - centers of resistance, as well as the destruction of the remnants of the Vladimir troops, which were collected by the fleeing Yuri Vsevolodovich. They also had to cut off the grand ducal “camp” from Southern Rus' and Novgorod, from where reinforcements could be expected. Solving these problems, the Mongol troops moved from Vladimir in three main directions: to the north - to Rostov, to the east - to the Middle Volga (to Gorodets), to the northwest - to Tver and Torzhok.

The main forces of Batu went from Vladimir to the north to defeat Grand Duke Yuri Vsevolodovich. The Tatar army passed along the ice of the Nerl River and, before reaching Pereyaslavl-Zalessky, turned north to Lake Nero. Rostov was abandoned by the prince and his squad, so he surrendered without a fight.

From Rostov, the Mongol troops went in two directions: a large army headed north along the ice of the Ustye River and further along the plain to Uglich, and another large detachment moved along the Kotorosl River to Yaroslavl. These directions of movement of the Tatar detachments from Rostov are quite understandable. Through Uglich lay the shortest road to the tributaries of the Mologa, to the City, where Grand Duke Yuri Vsevolodovich was camped. The march to Yaroslavl and further along the Volga to Kostroma through the rich Volga cities cut off Yuri Vsevolodovich’s retreat to the Volga and ensured a meeting somewhere in the Kostroma region with another Tatar detachment moving up the Volga from Gorodets.

The chroniclers do not report any details of the capture of Yaroslavl, Kostroma and other cities along the Volga. Only on the basis of archaeological data can we assume that Yaroslavl was severely destroyed and could not be restored for a long time. There is even less information about the capture of Kostroma. Kostroma, apparently, was the place where the Tatar detachments that came from Yaroslavl and Gorodets met. Chroniclers report on campaigns of Tatar troops even to Vologda.

The Mongol detachment, which moved from Vladimir to the northwest, was the first to encounter the city of Pereyaslavl-Zalessky - a strong fortress on the shortest waterway from the Klyazma River basin to Novgorod. A large Tatar army approached Pereyaslavl along the Nerl River in mid-February and, after a five-day siege, took the city by storm.

From Pereyaslavl-Zalessky, Tatar detachments moved in several directions. As the chronicle reports, some of them went to help the Tatar Khan Burundai to Rostov. The other part joined the Tatar army, which had earlier turned from the Nerl to Yuryev. The remaining troops moved across the ice of Lake Pleshcheevo and the Nerl River to Ksnyatin to cut the Volga route. The Tatar army, moving along the Nerl to the Volga, took Ksnyatin and quickly moved up the Volga to Tver and Torzhok. Another Mongol army captured Yuryev and went further west, through Dmitrov, Volokolamsk and Tver to Torzhok. Near Tver, Tatar troops joined forces with troops rising up the Volga from Ksnyatin.

As a result of the February campaigns of 1238, the Mongol-Tatars destroyed Russian cities over a vast territory, from the Middle Volga to Tver.

Battle on the City

By the beginning of March 1238, the Mongol-Tatar detachments that pursued the Vladimir prince Yuri Vsevolodovich, who had fled from the city, reached the Upper Volga line on a wide front. Grand Duke Yuri Vsevolodovich, who was gathering troops in a camp on the City River, found himself close to the Tatar army. The large Tatar army moved from Uglich and Kashin to the City River. On the morning of March 4 they were at the river. Prince Yuri Vsevolodovich was never able to gather sufficient forces. A fight ensued. Despite the surprise of the attack and the large numerical superiority of the Tatar army, the battle was stubborn and lengthy. But still, the army of the Vladimir prince could not withstand the blow of the Tatar cavalry and ran. As a result, the Russian army was defeated, and the Grand Duke himself died. The historical source Rashid ad-Din did not attach much importance to the battle of the City; in his view, it was simply a pursuit of the prince who had fled and was hiding in the forests.

Siege of Torzhok

Almost simultaneously with the Battle of the City, in March 1238, a Tatar detachment captured the city of Torzhok, a fortress on the southern borders of the Novgorod land. The city was a transit point for wealthy Novgorod merchants and traders from Vladimir and Ryazan, who supplied Novgorod with bread. Torzhok always had large reserves of grain. Here the Mongols hoped to replenish their food supplies that had become depleted over the winter.

Torzhok occupied an advantageous strategic position: it blocked the shortest route from the “Nizovskaya land” to Novgorod along the Tvertsa River. The defensive earthen rampart on the Borisoglebskaya side of Torzhok had a height of 6 fathoms. However, in winter conditions this important advantage of the city largely disappeared, but still Torzhok was a serious obstacle on the way to Novgorod and delayed the advance of the Mongol-Tatars for a long time.

The Tatars approached Torzhok on February 22. There was neither a prince nor a princely squad in the city, and the entire burden of defense was taken upon the shoulders of the townspeople, led by elected mayors. After a two-week siege and the continuous work of the Tatar siege engines, the city people weakened. Finally, Torzhok, exhausted by a two-week siege, fell. The city was subjected to a terrible defeat, most of its inhabitants died.

Hike to Novgorod

Regarding Batu's campaign against Novgorod, historians usually say that by this time significant forces of the Mongol-Tatars had concentrated near Torzhok. And only the Mongol troops, weakened from continuous battles, due to the approach of spring with its thaw and floods, were forced to return, not reaching 100 versts to Novgorod.

However, chroniclers report that the Mongol-Tatars headed towards Novgorod immediately after the capture of Torzhok, pursuing the surviving defenders of the city. Taking into account the location of all the Mongol-Tatar troops at this time, one can reasonably assume that only a small separate detachment of Tatar cavalry was moving towards Novgorod. Therefore, his campaign did not have the goal of taking the city: it was a simple pursuit of a defeated enemy, usual for the tactics of the Mongol-Tatars.

After the capture of Torzhok, the Mongol-Tatar detachment began to pursue the defenders of the city who had emerged from encirclement along the Seliger route further. But, not having reached Novgorod a hundred miles, this Mongol-Tatar cavalry detachment united with the main forces of Batu.

And yet the turn away from Novgorod is usually explained by spring floods. In addition, in the 4-month battles with the Russians, the Mongol-Tatars suffered huge losses, and Batu’s troops found themselves scattered. So the Mongol-Tatars did not try to attack Novgorod in the spring of 1238.

Kozelsk

After Torzhok, Batu turns south. He walked across the entire territory of Rus', using hunting raid tactics. In the upper reaches of the Oka, the Mongols met fierce resistance from the small fortress of Kozelsk. Despite the fact that the city prince Vasilko Konstantinovich was still too young, and despite the fact that the Mongols demanded to surrender the city, the Kozel residents decided to defend themselves. The heroic defense of Kozelsk lasted for seven weeks. The Kozel residents destroyed about 4 thousand Mongols, but were unable to defend the city. Bringing siege equipment to it, the Mongol troops destroyed the city walls and entered Kozelsk. Batu did not spare anyone, despite his age, he killed the entire population in the city. He ordered the city to be razed to the ground, the ground plowed up and the place filled with salt so that it could never be rebuilt. Prince Vasilko Konstantinovich, according to legend, drowned in blood. Batu called the city of Kozelsk an “evil town.” From Kozelsk, the combined forces of the Mongol-Tatars, without stopping, moved south to the Polovtsian steppes.

Mongol-Tatars in the Polovtsian steppes

Stay of the Mongol-Tatars in the Polovtsian steppes from the summer of 1238 to the autumn of 1240. is one of the least studied periods of the invasion. In historical sources, there is an opinion that this period of invasion is the time of the Mongols’ retreat to the steppes for rest, restoration of regiments and horse army after a difficult winter campaign in North-Eastern Rus'. The entire stay of the Mongol-Tatars in the Polovtsian steppes is perceived as a break in the invasion, filled with restoration of strength and preparation for the big campaign to the West.

However, eastern sources describe this period in a completely different way: the entire period of Batu’s stay in the Polovtsian steppes was filled with continuous wars with the Polovtsians, Alans and Circassians, numerous invasions of border Russian cities, and the suppression of popular uprisings.

Military operations began in the fall of 1238. A large Mongol-Tatar army headed towards the land of the Circassians, beyond the Kuban. Almost simultaneously, a war began with the Polovtsians, whom the Mongol-Tatars had previously forced out across the Don. The war with the Polovtsians was long and bloody, a huge number of Polovtsians were killed. As the chronicles write, all the forces of the Tatars were thrown into the fight against the Polovtsy, so Rus' was peaceful at that time.

In 1239, the Mongol-Tatars intensified military operations against the Russian principalities. Their campaigns hit the lands that were located next to the Polovtsian steppes, and were carried out with the aim of expanding the land they conquered.

In winter, a large Mongol army moved north to the region of Mordva and Murom. During this campaign, the Mongol-Tatars suppressed the uprising of the Mordovian tribes, took and destroyed Murom, devastated the lands along the Nizhnyaya Klyazma and reached Nizhny Novgorod.

In the steppes between the Northern Donets and the Dnieper, the war between the Mongol troops and the Polovtsians continued. In the spring of 1239, one of the Tatar detachments that approached the Dnieper defeated the city of Pereyaslavl, a strong fortress on the borders of Southern Rus'.

This capture was one of the stages of preparation for a large campaign to the west. The next campaign had the goal of defeating Chernigov and the cities along the Lower Desna and Seim, since the Chernigov-Seversk land was not yet conquered and threatened the right flank of the Mongol-Tatar army.

Chernigov was a well-fortified city. Three defensive lines protected it from enemies. The geographical position near the borders of the Russian land and active participation in internecine wars created in Rus' the opinion of Chernigov as a city famous for its large number of warriors and courageous population.

The Mongol-Tatars appeared within the Chernigov principality in the fall of 1239, invaded these lands from the southeast and surrounded them. A fierce battle began on the walls of the city. The defenders of Chernigov, as the Laurentian Chronicle describes, threw heavy stones from the walls of the city at the Tatars. After a fierce battle on the walls, the enemies burst into the city. Having taken it, the Tatars beat up the local population, plundered the monasteries and set fire to the city.

From Chernigov, the Mongol-Tatars moved east along the Desna and further along the Seim. There, numerous cities built to protect against nomads (Putivl, Glukhov, Vyr, Rylsk, etc.) were destroyed and the countryside was devastated. Then the Mongol army turned south, to the upper reaches of the Northern Donets.

The last Mongol-Tatar campaign in 1239 was the conquest of Crimea. The Polovtsians, defeated by the Mongols in the Black Sea steppes, fled here, to the steppes of the northern Crimea and further to the sea. Pursuing them, Mongol troops came to Crimea. The city was taken.

Thus, during 1239, the Mongol-Tatars defeated the remnants of the Polovtsian tribes that they had not conquered, made significant campaigns in the Mordovian and Murom lands, and conquered almost the entire Left Bank of the Dnieper and the Crimea. Now the Tatar possessions came close to the borders of Southern Rus'. The southwestern direction of Rus' was the next target for the Mongol invasion.

A trip to southwestern Rus'. Preparing for the hike

At the beginning of 1240, in winter, the Mongol army approached Kyiv. This trip can be regarded as reconnaissance of the area before the start of hostilities. Since the Tatars did not have the strength to take fortified Kyiv, they limited themselves to reconnaissance and a short throw to the right bank of the Dnieper to pursue the retreating Kyiv prince Mikhail Vsevolodovich. Having captured the "full", the Tatars turned back.

In the spring of 1240, a significant army was moved south, along the Caspian coast, to Derbent. This advance to the south, to the Caucasus, was not accidental. The forces of the Jochi ulus, partially freed after the campaign against North-Eastern Rus', were used to complete the conquest operation of the Caucasus. Previously, the Mongols continuously attacked the Caucasus from the south: in 1236, Mongol troops devastated Georgia and Armenia; 1238 conquered the lands between the Kura and Araks; in 1239 they captured Kars and the city of Ani, the former capital of Armenia. The troops of the Jochi ulus took part in the general Mongol offensive in the Caucasus with attacks from the north. The peoples of the North Caucasus stubbornly resisted the conquerors.

By the fall of 1240, preparations for a large campaign to the west were completed. The Mongols conquered areas that were not conquered in the campaign of 1237-38, suppressed popular uprisings in the Mordovian lands and Volga Bulgaria, occupied the Crimea and the North Caucasus, destroyed Russian fortified cities on the left bank of the Dnieper (Pereyaslavl, Chernigov) and came close to Kyiv. He was the first point of attack.

Hike to the southwest of Rus'

In historical literature, the presentation of the facts of Batu’s campaign against Southern Rus' usually begins with the siege of Kyiv. He, “the mother of Russian cities,” was the first large city on the path of the new Mongol invasion. The bridgehead for the invasion had already been prepared: Pereyaslavl, the only large city that covered the approaches to Kyiv from this side, was taken and destroyed in the spring of 1239.

The news of Batu's impending campaign reached Kyiv. However, despite the immediate danger of invasion, no attempts were noticeable in Southern Rus' to unite to repel the enemy. Princely strife continued. Kyiv was actually left to its own forces. He did not receive any help from other southern Russian principalities.

Batu began the invasion in the fall of 1240, again gathering under his command all the people devoted to himself. In November he approached Kyiv, the Tatar army surrounded the city. Spread over the high hills above the Dnieper, the great city was heavily fortified. The powerful ramparts of the Yaroslav city covered Kyiv from the east, south and west. Kyiv resisted the incoming enemies with full force. The people of Kiev defended every street, every house. But, nevertheless, with the help of powerful battering guns and rapids, on December 6, 1240, the city fell. It was terribly devastated, most of the buildings were destroyed in the fire, the inhabitants were killed by the Tatars. Kyiv lost its significance as a major urban center for a long time.

Now, after the capture of great Kyiv, the path to all centers of Southern Rus' and Eastern Europe was open for the Mongol-Tatars. It's Europe's turn.

Batu's exit from Rus'

From the destroyed Kyiv, the Mongol-Tatars moved further west, in the general direction to Vladimir-Volynsky. In December 1240, under the onslaught of Mongol-Tatar troops, the cities along Middle Teterev were abandoned by the population and garrisons. Most of the Bolokhov cities also surrendered without a fight. The Tatars confidently, without turning aside, walked west. On the way, they encountered strong resistance from small towns on the outskirts of Rus'. Archaeological studies of settlements in this area recreate the picture of the heroic defense and destruction of fortified towns under the blows of superior forces of the Mongol-Tatars. Vladimir-Volynsky was also taken by the Mongols by storm after a short siege. The final point of the “raid”, where the Mongol-Tatar detachments united after the devastation of South-Western Rus', was the city of Galich. After the Tatar pogrom, Galich became deserted.

As a result, having defeated the Galician and Volyn lands, Batu left the Russian lands. In 1241, a campaign began in Poland and Hungary. Batu’s entire campaign against Southern Rus' thus took very little time. With the departure of the Mongol-Tatar troops abroad, the Mongol-Tatar campaign against Russian lands ended.

Coming out of Rus', Batu’s troops invade the states of Europe, where they instill horror and fear in the inhabitants. In Europe it was stated that the Mongols had escaped from hell, and everyone was waiting for the end of the world. But Rus' still resisted. In 1241 Batu returned to Rus'. In 1242, in the lower reaches of the Volga, he established his new capital - Sarai-bata. At the end of the 13th century, after Batu created the state of the Golden Horde, the Horde yoke was established in Rus'.

Establishment of the yoke in Rus'

The Mongol-Tatar campaign against Russian lands ended. Rus' was devastated after the terrible invasion, but gradually it begins to recover, normal life is restored. The surviving princes return to their capitals. The dispersed population is gradually returning to Russian lands. Cities are being restored, villages and villages are being repopulated.

In the first years after the invasion, the Russian princes were more worried about their destroyed cities, engaged in their restoration, and the distribution of princely tables. They were now less concerned about the problem of establishing any kind of relations with the Mongol-Tatars. The invasion of the Tatars did not have much impact on the interpersonal relations of the princes: in the capital of the country, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich sat on the grand-ducal throne, and transferred the remaining lands into the possession of his younger brothers.

But the calm of Rus' was disrupted again when the Mongol-Tatars, after a campaign against Central Europe, appeared on Russian lands. The Russian princes were faced with the question of establishing some kind of relationship with the conquerors. Touching upon the issue of further relations with the Tatars, the problem of disputes between the princes arose: opinions differed on further actions. The cities captured by the Mongol armies were in a terrible state of destruction. Some cities were completely burned out. Temples, churches, cultural monuments were destroyed and also burned. To restore the city before the time of the Mongol invasion, enormous forces, funds and time were needed. The Russian people had no strength: neither to restore cities, nor to fight the Tatars. Strong and wealthy cities in the northwestern and western outskirts that were not subject to the Mongol invasion (Novgorod, Pskov, Polotsk, Minsk, Vitebsk, Smolensk) joined the opposition. They, accordingly, opposed the recognition of dependence on the Horde khans. They were not harmed, retaining their lands, wealth and armies.

The existence of these two groups - the northwestern one, which opposed the recognition of dependence on the Horde, and the Rostov one, which was inclined to establish peaceful relations with the conquerors - largely determined the policy of the Grand Duke of Vladimir. In the first decade after Batu's invasion, it was ambivalent. But the people of northeastern Rus' did not have the strength to openly resist the conquerors, which made the recognition of Rus'’s dependence on the Golden Horde khans inevitable.

In addition, the prince’s decision was influenced by a significant circumstance: the voluntary recognition of the power of the Horde khan provided the Grand Duke personally with certain advantages in the struggle to subjugate other Russian princes to his influence. In case of non-recognition of the dependence of the Russian land on the Horde, the prince could be overthrown from his grand-ducal table. But on the other hand, the prince’s decision was influenced by the existence of strong opposition to the Horde power in North-Western Rus' and the West’s repeated promises of military assistance against the Mongol-Tatars. These circumstances could awaken hope, under certain conditions, to resist the claims of the conquerors. In addition, in Rus' the masses constantly spoke out against the foreign yoke, with whom the Grand Duke could not help but take them into account. As a result, formal recognition of Rus'’s dependence on the Golden Horde was proclaimed. But the fact of recognition of this power did not actually mean the establishment of a foreign yoke over the country.

The first decade after the invasion is the period when the foreign yoke was just taking shape. At this time, popular forces in Rus' spoke out for Tatar rule, and so far they were victorious.

The Russian princes, recognizing their dependence on the Mongol-Tatars, tried to establish relations with them, for which they often visited the Horde khan. Following the Grand Duke, other princes flocked to the Horde “about their fatherland.” Probably, the trip of the Russian princes to the Horde was somehow connected with the formalization of tributary relations.

Meanwhile, strife continued in North-Eastern Rus'. And among the princes, two oppositions stood out: for and against dependence on the Golden Horde.

But in general, in the early 50s of the 13th century, a fairly strong anti-Tatar group formed in Rus', ready to resist the conquerors.

However, the policy of Grand Duke Andrei Yaroslavich, aimed at organizing resistance to the Tatars, collided with the foreign policy of Alexander Yaroslavich, who considered it necessary to maintain peaceful relations with the Horde to restore the strength of the Russian princes and prevent new Tatar campaigns.

New Tatar invasions could be prevented by establishing peaceful relations with the Horde, that is, recognizing its power. Under these conditions, the Russian princes made a certain compromise with the Mongol-Tatars. They recognized the supreme power of the khan and donated part of the feudal rent to the Mongol-Tatar feudal lords. In return, the Russian princes received confidence in the absence of the danger of a new invasion from the Mongols, and they also more firmly established themselves on their princely throne. The princes who opposed the power of the khan risked losing their power, which, with the help of the Mongol khan, could pass to another Russian prince. The Horde khans, in turn, were also interested in an agreement with the local princes, since they received additional weapons to maintain their rule over the masses.

Later, the Mongol-Tatars established a “regime of systematic terror” in Rus'. The slightest disobedience of the Russians caused punitive expeditions of the Mongols. During the second half of the 13th century, they carried out no less than twenty devastating campaigns against Rus', each of which was accompanied by the destruction of cities and villages and the taking of Russian people into captivity.

As a result of Russia's recognition of dependence on the Golden Horde, Rus' continued to live a turbulent, complex, tense life for many years. There was a struggle between the princes for and against the Golden Horde, and frequent strife occurred. Anti-Tatar groups constantly spoke out. Both some Russian princes and Mongol khans opposed the popular mass uprisings. The people experienced constant pressure from the Golden Horde. Rus', already once shocked by the terrible tragedy of the Mongol invasion, now again lived in constant fear of a new destructive offensive of the Golden Horde. Rus' was in such a dependent position on the Golden Horde until the end of the 14th century on September 8, 1380. Grand Duke Dmitry Donskoy in the Battle of Kulikovo Field defeated the main forces of the Golden Horde, and dealt a serious blow to its military and political dominance. This was a victory over the Mongol-Tatars, and the final liberation of Rus' from the dependence of the Golden Horde.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF Rus'

Serious changes occurred in the socio-economic development of Rus' in the 13th and 14th centuries. After the invasion of the Mongol-Tatars in North-Eastern Rus', the economy was restored and handicraft production was revived again. There is a growth and increase in the economic importance of cities that did not play a serious role in the pre-Mongol period (Moscow, Tver, Nizhny Novgorod, Kostroma).

Fortress construction is actively developing, and the construction of stone churches is being resumed. Agriculture and crafts are rapidly developing in North-Eastern Rus'.

Old technologies are being improved and new ones are emerging.

Got widespread in Rus' water wheels and water mills. Parchment began to be actively replaced by paper. Salt production is developing. Centers for the production of books appear in large book centers and monasteries. Casting (bell production) is developing massively. Agriculture is developing somewhat more slowly than crafts.

Slash-and-burn agriculture continues to be replaced by field arable land. Two-field is widespread.

New villages are being actively built. The number of domestic animals is increasing, which means the application of organic fertilizers to the fields is increasing.

LARGE LAND OWNERSHIP IN Rus'

The growth of patrimonial estates occurs through the distribution of lands by princes to their boyars for feeding, that is, for management with the right to collect taxes in their favor.

From the second half of the 14th century, monastic land ownership began to grow rapidly.

PEASANTRY IN Rus'

In Ancient Rus', the entire population was called peasants, regardless of their occupation. As one of the main classes of the Russian population, whose main occupation is agriculture, the peasantry took shape in Russia by the 14th - 15th centuries. A peasant sitting on land with a three-field rotation had on average 5 acres in one field, therefore 15 acres in three fields.

Rich peasants they took additional plots from patrimonial owners in black volosts. Poor peasants often had neither land nor yard. They lived in other people's yards and were called street cleaners. These peasants bore corvée duties to their owners - they plowed and sowed their land, harvested crops, and cut hay. Meat and lard, vegetables and fruits and much more were contributed to the dues. All peasants were already feudal dependents.

- community- worked on state lands,

- proprietary- these could leave, but within a clearly limited time frame (Philip’s Day on November 14, St. George’s Day on November 26, Peter’s Day on June 29, Christmas Day on December 25)

- personally dependent peasants.

STRUGGLE OF MOSCOW AND TVER PRINCIPALITY IN Rus'

By the beginning of the 14th century, Moscow and Tver became the strongest principalities of North-Eastern Rus'. The first Moscow prince was the son of Alexander Nevsky, Daniil Alexandrovich (1263-1303). In the early 90s, Daniil Alexandrovich annexed Mozhaisk to the Moscow principality, and in 1300 he conquered Kolomna from Ryazan.

From 1304, Daniil's son Yuri Danilovich fought for the great reign of Vladimir with Mikhail Yaroslavovich Tverskoy, who received the label for the great reign in the Golden Horde in 1305.

The Moscow prince was supported in this fight by Metropolitan of All Rus' Macarius

In 1317, Yuri achieved a label for the great reign, and a year later, Yuri’s main enemy, Mikhail Tverskoy, was killed in the Golden Horde. But in 1322, Prince Yuri Daniilovich was deprived of his great reign as punishment. The label was given to the son of Mikhail Yaroslavovich Dmitry Groznye Ochi.

In 1325, Dmitry killed the culprit in the death of his father in the Golden Horde, for which he was executed by the khan in 1326.

The great reign was transferred to Dmitry Tverskoy’s brother, Alexander. A Horde detachment was sent with him to Tver. The outrages of the Horde caused an uprising of the townspeople, which was supported by the prince, and as a result the Horde were defeated.

IVAN KALITA

These events were skillfully used by the new Moscow prince Ivan Kalita. He participated in the punitive Horde expedition to Tver. The Tver land was devastated. The Great Principality of Vladimir was divided between Ivan Kalita and Alexander of Suzdal. After the death of the latter, the label for the great reign was almost constantly in the hands of the Moscow princes. Ivan Kalita continued the line of Alexander Nevsky in that he maintained a lasting peace with the Tatars.

These events were skillfully used by the new Moscow prince Ivan Kalita. He participated in the punitive Horde expedition to Tver. The Tver land was devastated. The Great Principality of Vladimir was divided between Ivan Kalita and Alexander of Suzdal. After the death of the latter, the label for the great reign was almost constantly in the hands of the Moscow princes. Ivan Kalita continued the line of Alexander Nevsky in that he maintained a lasting peace with the Tatars.

He also made an alliance with the church. Moscow becomes the center of faith, since the Metropolitan moved to Moscow forever and left Vladimir.

The Grand Duke received the right from the Horde to collect tribute himself, which had favorable consequences for the treasury of Moscow.

Ivan Kalita also increased his holdings. New lands were bought and begged from the Khan of the Golden Horde. Galich, Uglich and Beloozero were annexed. Also, some princes voluntarily became part of the Moscow Principality.

THE PRINCIPALITY OF MOSCOW LEADS THE OVERTHROW OF THE TATAR-MONGOL Yoke BY RUSSIA

The policy of Ivan Kalita was continued by his sons - Semyon the Proud (1340-1359) and Ivan 2 the Red (1353-1359). After the death of Ivan 2, his 9-year-old son Dmitry (1359-1387) became the prince of Moscow. At this time, Prince Dmitry Konstantinovich of Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod had the title to reign. A sharp struggle developed between him and the group of the Moscow boyars. Metropolitan Alexey took the side of Moscow, who actually headed the Moscow government until Moscow finally won the victory in 1363.

Grand Duke Dmitry Ivanovich continued the policy of strengthening the Moscow principality. In 1371, Moscow inflicted a major defeat on the Ryazan principality. The struggle with Tver continued. When in 1371 Mikhail Alekseevich Tverskoy received the label for the great reign of Vladimir and tried to occupy Vladimir, Dmitry Ivanovich refused to obey the khan's will. In 1375, Mikhail Tverskoy again received a label to the Vladimir table. Then almost all the princes of northeastern Rus' opposed him, supporting the Moscow prince in his campaign against Tver. After a month-long siege, the city capitulated. According to the concluded agreement, Mikhail recognized Dmitry as his overlord.

As a result of the internal political struggle in the North-Eastern Russian lands, the Moscow Principality achieved a leading position in the collection of Russian lands and became a real force capable of resisting the Horde and Lithuania.

Since 1374, Dmitry Ivanovich stopped paying tribute to the Golden Horde. The Russian Church played a major role in strengthening anti-Tatar sentiments.

In the 60s and 70s of the 14th century, civil strife within the Golden Horde intensified. Over two decades, up to two dozen khans appear and disappear. Temporary workers appeared and disappeared. One of these, the strongest and cruelest, was Khan Mamai. He tried to collect tribute from Russian lands, despite the fact that Takhtamysh was the legitimate khan. The threat of a new invasion united the main forces of North-Eastern Rus' under the leadership of the Moscow prince Dmitry Ivanovich.

The sons of Olgerd, Andrei and Dmitry, who transferred to the service of the Moscow prince, took part in the campaign. Mamai's ally, Grand Duke Jagiello, was late to arrive to join the Horde army. The Ryazan prince Oleg Ivanovich did not join Mamai, who only formally entered into an alliance with the Golden Horde.

On September 6, the united Russian army approached the banks of the Don. So for the first time since 1223, since the battle on the Kalka River, the Russians went out into the steppe to meet the Horde. On the night of September 8, Russian troops, on the orders of Dmitry Ivanovich, crossed the Don.

The battle took place on September 8, 1380 on the bank of the right tributary of the Don river. Untruths, in an area called Kulikovo Field. At first, the Horde pushed back the Russian regiment. Then they were attacked by an ambush regiment under the command of the Serpukhov prince. The Horde army could not withstand the onslaught of fresh Russian forces and fled. The battle turned into a pursuit of the enemy retreating in disorder.

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE BATTLE OF KULIKOVO

The historical significance of the Battle of Kulikovo was enormous. The main forces of the Golden Horde were defeated.

The idea became stronger in the minds of the Russian people that with united forces the Horde could be defeated.

Prince Dmitry Ivanovich received the honorary nickname Donskoy from his descendants and found himself in the political role of an all-Russian prince. His authority increased unusually. Militant anti-Tatar sentiments intensified in all Russian lands.

DMITRY DONSKOY

Having lived only less than four decades, he did a lot for Rus' from a young age until the end of his days, Dmitry Donskoy was constantly in worries, campaigns and troubles. He had to fight with the Horde and with Lithuania and with Russian rivals for power and political primacy.

The prince also settled church affairs. Dmitry received the blessing of Abbot Sergius of Radonezh, whose constant support he always enjoyed.

SERGIUS OF RADONEZH