IN XI in Europe the population began to grow sharply. TO XIV century it was impossible to feed everyone enough. More or less cultivable land was used. Lean years occurred more and more often, as the climate of Europe began to change - there was great cold and frequent rain. Hunger did not leave the cities and villages, the population suffered. But that wasn't the worst thing. The weakened population often fell ill. IN 1347 year the most terrible epidemic began.

Came to Sicily and ships from eastern countries. In their holds they carried black rats, which became the main source of a deadly type of plague. A terrible disease began to instantly spread throughout Western Europe. Everywhere people started dying. Some patients died in long agony, while others died instantly. Places of mass gatherings – cities – suffered the most. Sometimes there were no people there to bury the dead. Over 3 years, the European population decreased by 3 times. Frightened people fled the cities faster and spread the plague even more. That period of history was called the time "Black Death".

The plague affected neither kings nor slaves. Europe was divided into borders, to somehow reduce the spread of the disease.

IN 1346 year The Genoese attacked modern Feodosia. For the first time in history it was used biological weapons. The Crimean Khan threw the corpses of plague victims behind the besieged walls. The Genoese were forced to return to Constantinople, carrying with them a terrible murder weapon. Almost half of the city's population died.

European merchants, in addition to expensive goods from Constantinople, brought plague. Rat fleas were the main carriers of the terrible disease. The port cities were the first to take the hit. Their numbers decreased sharply.

The sick were treated by monks, who, by the will of the service, were supposed to help the suffering. It was among the clergy and monks that the greatest number of deaths occurred. Believers began to panic: if God’s servants were dying from the plague, what should the common people do? People considered it a punishment from God.

The Black Death plague came in three forms:

Bubonic plague– tumors appeared on the neck, groin and armpit. Their size could reach a small apple. The buboes began to turn black and after 3-5 days the patient died. This was the first form of plague.

Pneumonic plague– the person’s respiratory system suffered. It was transmitted by airborne droplets. The patient died almost instantly - within two days.

Septicemic plague– the circulatory system was affected. The patient had no chance to survive. Bleeding began from the mouth and nasal cavity.

Doctors and ordinary people could not understand what was happening. Panic began from horror. No one understood how he became infected with the Black Disease. On the first couple of occasions, the dead were buried in the church and buried in an individual grave. Later the churches were closed and the graves became common. But they too were instantly filled with corpses. Dead people were simply thrown out into the street.

In these terrible times, the looters decided to profit. But they also became infected and died within a few days.

Residents of cities and villages were afraid of becoming infected and locked themselves in their houses. The number of people able to work decreased. They sown little and harvested even less. To compensate for losses, landowners began to inflate land rent. Food prices have risen sharply. Neighboring countries were afraid to trade with each other. A poor diet further favored the spread of the plague.

The peasants tried to work only for themselves or demanded more money for their work. The nobility was in dire need of labor. Historians believe that the plague revived the middle class in Europe. New technologies and working methods began to appear: an iron plow, a three-field sowing system. A new economic revolution began in Europe in conditions of famine, epidemics and food shortages. The top government began to look at the common people differently.

The mood of the population also changed. People became more withdrawn and avoided their neighbors. After all, anyone could get the plague. Cynicism is developing, and morals have changed to the opposite. There were no feasts or balls. Some lost heart and spent the rest of their lives in taverns.

Society was divided. Some in fear refused a large inheritance. Others considered the plague a finger of fate and began a righteous life. Still others became real recluses and did not communicate with anyone. The rest escaped with good drinks and fun.

The common people began to look for the culprits. They became Jews and foreigners. The mass extermination of Jewish and foreign families began.

But after 4 years The Black Death plague in Europe in the 14th century subsided. Periodically, she returned to Europe, but did not cause massive losses. Today man has completely defeated the plague!

The Black Death is the most terrible epidemic known in history, spreading across Europe in the period 1347-1351. It is generally accepted that this was an outbreak of bubonic and pneumonic plague. For more than three centuries, the disease came to the European continent again and again, although later epidemics were no longer so devastating.

In ancient times, the word “plague” (“pestis” in Latin, “loimos” in Greek) meant any epidemic in general, a disease that is accompanied by fever or fever. For example, the “plague” that struck Athens at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War and killed Pericles was, according to the historian Thucydides’ description, typhoid fever.

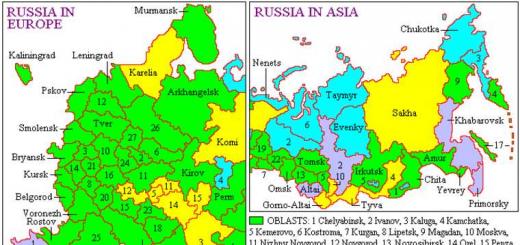

In the VI century. In Europe there was an epidemic of a disease called plague, the so-called Plague of Justinian. Local outbreaks have sometimes been observed in different countries. But in 1346-1347. in the territory including the lower reaches of the Volga, the Northern Caspian Sea, the Northern Caucasus, Transcaucasia, Crimea, the Eastern spurs of the Carpathians, the Black Sea region, the Near and Middle East, Asia Minor, the Balkans, Sicily, Rhodes, Cyprus, Malta, Sardinia, Corsica, North Africa, the south of the Iberian peninsula, the mouth of the Rhone, the activation of natural foci of plague began.

It was believed that the beginning of the epidemic in the 14th century. ended the siege of the Genoese fortress of Kafa (modern Feodosia) in Crimea by Khan Janibek. The disease struck the besiegers, and then they began to throw the corpses of the dead into the city with catapults. In fact, as researchers now think, the episode with the siege of Kafa could not have had a significant impact on the spread of the disease. By that time, the plague was already raging in Asia, and the traders of the Great Silk Road inevitably spread it throughout the vast continent. Already in May 1347, Paris knew about the epidemic in Asia and Eastern Europe. The many symptoms of the disease were scary and unexpected. With bubonic plague, patients developed tumors in the lymph nodes - buboes; with the pulmonary form, hemoptysis began. All this was supplemented by a rash, nausea, vomiting, and fever. And if someone sick with the bubonic form could recover, then everyone died from pneumonic plague.

The Genoese, who managed to escape to the West, spread the plague throughout Europe. In 1347, the epidemic spread to Constantinople, Greece, Sicily and Dalmatia. In June 1348 it spread to France and Spain, and in the fall to England and Ireland. In 1349, the disease spread to Germany, Scandinavia, Iceland and even Greenland. In 1352, an epidemic came to Rus'. In total, at least 25 million Europeans died over these years. People then considered the cause of the plague to be harmful fumes, miasmas, and spoiled air. However, they also understood the danger of infection, so they arranged quarantines.

But the disease did not stop the development of European civilization. The old states remained, the old conflicts continued. In the most terrible years, Petrarch traveled through Italy, dreaming of the return of the ancient heritage and becoming the forerunner of the Renaissance, and Boccaccio wrote his Decameron, imbued with the ideas of humanism and the desire for love and happiness.

What could have caused this epidemic? Expansion of the steppe zone, and, consequently, the spread of rodents - carriers of the disease? Indeed, in Rus' the first years of the 14th century were dry; in 1308, an invasion of rodents was observed everywhere, accompanied by pestilence and famine. But the Black Death came forty years later, and the last years before the epidemic the weather in southern Europe was warm and damp. Frequent floods, snowy winters, rainy summer months - the steppe could not expand under such conditions.

Most of the reports of plague affecting the lungs concerned northern countries (England, Norway, Russia). And, probably, during the Black Death pandemic, secondary pneumonic plague prevailed, which developed as a complication of the bubonic plague.

But the bubonic plague does not spread beyond its natural foci, does not spread in the North, it could not cover all of Europe so quickly. In 1997, Nobel Prize laureate in biochemistry J. Lederberg suggested that the clinical picture of the then widespread disease was “tailored” to the clinic of the plague. The monstrous mortality rate of the European population during the first epidemics of the Black Death was not characteristic of any of the subsequent epidemics. Lederberg doubts that the Black Death is a plague. There is also a hypothesis that some other factors influenced human susceptibility to the plague. They even call it AIDS, but it is worth remembering that starting from the 11th century, leprosy and smallpox became more active in Europe.

Epidemics continued into the next century, but pneumonic plague was replaced by the less dangerous bubonic form of the disease.

The last outbreaks in Western Europe occurred in England in 1665, Vienna in 1683. In London, the epidemic ended with the “great fire” of 1666. The city center was rebuilt, and Londoners believed that this was why the city no longer suffered from the plague. But the fire left untouched the overcrowded suburbs that had been a breeding ground for the plague in previous years. Subsequent outbreaks of the disease occurred further and further from the center of Europe. It almost looked as if European countries were developing some form of protection that would contain the spread of infection. In the north, the plague was retreating east; in the Mediterranean it went south. And each time, the areas where the disease spread were smaller and smaller, although people traveled more and more.

In the 18th century In Europe, black rats - plague carriers - were replaced by gray rats. Perhaps this is what led to the extinction of epidemics. But in the 18th century. Gray rats advanced into Europe from east to west, and the plague retreated from west to east. Maybe the black rats developed resistance to the plague and spread throughout their population. But this is unlikely. Perhaps a new strain of plague bacteria has emerged that is less contagious and dangerous than the earlier one. Perhaps some pathogens worked as vaccines, causing relative immunity in animals and people to a more dangerous strain of these bacteria.

Or, most likely, some kind of natural selection occurred, people with immunity to the plague survived and passed this property on to their descendants. In any case, the search for clues to the “Black Death” can lead to many interesting discoveries in medicine and help people fight infectious diseases.

The Black Death is a disease that is currently the subject of legends. This is actually the name given to the plague that struck Europe, Asia, North Africa and even Greenland in the 14th century. The pathology proceeded mainly in the bubonic form. The territorial focus of the disease has become where this place is, many people know. The Gobi belongs to Eurasia. The Black Sea arose precisely there due to the Little Ice Age, which served as an impetus for sudden and dangerous climate change.

It took the lives of 60 million people. Moreover, in some regions the death toll reached two-thirds of the population. Due to the unpredictability of the disease, as well as the impossibility of curing it at that time, religious ideas began to flourish among people. Belief in a higher power has become commonplace. At the same time, persecution began of the so-called “poisoners”, “witches”, “sorcerers”, who, according to religious fanatics, sent the epidemic to people.

This period remained in history as a time of impatient people who were overcome by fear, hatred, mistrust and numerous superstitions. In fact, of course, there is a scientific explanation for the outbreak of bubonic plague.

The Myth of the Bubonic Plague

When historians were looking for ways the disease could penetrate Europe, they settled on the opinion that the plague appeared in Tatarstan. More precisely, it was brought by the Tatars.

In 1348, led by Khan Dzhanybek, during the siege of the Genoese fortress of Kafa (Feodosia), they threw there the corpses of people who had previously died from the plague. After liberation, Europeans began to leave the city, spreading the disease throughout Europe.

But the so-called “plague in Tatarstan” turned out to be nothing more than a speculation of people who do not know how to explain the sudden and deadly outbreak of the “Black Death”.

The theory was defeated as it became known that the pandemic was not transmitted between people. It could be contracted from small rodents or insects.

This “general” theory existed for quite a long time and contained many mysteries. In fact, the plague epidemic, as it turned out later, began for several reasons.

Natural causes of the pandemic

In addition to dramatic climate change in Eurasia, the outbreak of bubonic plague was preceded by several other environmental factors. Among them:

- global drought in China followed by widespread famine;

- in Henan province massive;

- Rain and hurricanes prevailed in Beijing for a long time.

Like the Plague of Justinian, as the first pandemic in history was called, the Black Death struck people after massive natural disasters. She even followed the same path as her predecessor.

The decrease in people's immunity, provoked by environmental factors, has led to mass morbidity. The disaster reached such proportions that church leaders had to open rooms for the sick population.

The plague in the Middle Ages also had socio-economic prerequisites.

Socio-economic causes of bubonic plague

Natural factors could not provoke such a serious outbreak of the epidemic on their own. They were supported by the following socio-economic prerequisites:

- military operations in France, Spain, Italy;

- the dominance of the Mongol-Tatar yoke over part of Eastern Europe;

- increased trade;

- soaring poverty;

- too high population density.

Another important factor that provoked the invasion of the plague was a belief that implied that healthy believers should wash as little as possible. According to the saints of that time, contemplation of one’s own naked body leads a person into temptation. Some followers of the church were so imbued with this opinion that they never immersed themselves in water in their entire adult lives.

Europe in the 14th century was not considered a pure power. The population did not monitor waste disposal. Waste was thrown directly from the windows, slops and the contents of chamber pots were poured onto the road, and the blood of livestock flowed into it. This all later ended up in the river, from which people took water for cooking and even for drinking.

Like the Plague of Justinian, the Black Death was caused by large numbers of rodents that lived in close contact with humans. In the literature of that time you can find many notes on what to do in case of an animal bite. As you know, rats and marmots are carriers of the disease, so people were terrified of even one of their species. In an effort to overcome rodents, many forgot about everything, including their family.

How it all began

The origin of the disease was the Gobi Desert. The location of the immediate outbreak is unknown. It is assumed that the Tatars who lived nearby declared a hunt for marmots, which are carriers of the plague. The meat and fur of these animals were highly valued. Under such conditions, infection was inevitable.

Due to drought and other negative weather conditions, many rodents left their shelters and moved closer to people, where more food could be found.

Hebei province in China was the first to be affected. At least 90% of the population died there. This is another reason that gave rise to the opinion that the outbreak of the plague was provoked by the Tatars. They could lead the disease along the famous Silk Road.

Then the plague reached India, after which it moved to Europe. Surprisingly, only one source from that time mentions the true nature of the disease. It is believed that people were affected by the bubonic form of plague.

In countries that were not affected by the pandemic, real panic arose in the Middle Ages. The heads of the powers sent messengers for information about the disease and forced specialists to invent a cure for it. The population of some states, remaining ignorant, willingly believed rumors that snakes were raining on the contaminated lands, a fiery wind was blowing and acid balls were falling from the sky.

Low temperatures, a long stay outside the host's body, and thawing cannot destroy the causative agent of the Black Death. But sun exposure and drying are effective against it.

Bubonic plague begins to develop from the moment of being bitten by an infected flea. Bacteria enter the lymph nodes and begin their life activity. Suddenly, a person is overcome by chills, his body temperature rises, the headache becomes unbearable, and his facial features become unrecognizable, black spots appear under his eyes. On the second day after infection, the bubo itself appears. This is what is called an enlarged lymph node.

A person infected with the plague can be identified immediately. "Black Death" is a disease that changes the face and body beyond recognition. Blisters become noticeable already on the second day, and the patient’s general condition cannot be called adequate.

The symptoms of plague in a medieval person are surprisingly different from those of a modern patient.

Clinical picture of the bubonic plague of the Middle Ages

“Black Death” is a disease that in the Middle Ages was identified by the following signs:

- high fever, chills;

- aggressiveness;

- continuous feeling of fear;

- severe pain in the chest;

- dyspnea;

- cough with bloody discharge;

- blood and waste products turned black;

- a dark coating could be seen on the tongue;

- ulcers and buboes appearing on the body emitted an unpleasant odor;

- clouding of consciousness.

These symptoms were considered a sign of imminent and imminent death. If a person received such a sentence, he already knew that he had very little time left. No one tried to fight such symptoms; they were considered the will of God and the church.

Treatment of bubonic plague in the Middle Ages

Medieval medicine was far from ideal. The doctor who came to examine the patient paid more attention to talking about whether he had confessed than to directly treating him. This was due to the religious insanity of the population. Saving the soul was considered a much more important task than healing the body. Accordingly, surgical intervention was practically not practiced.

Treatment methods for plague were as follows:

- cutting tumors and cauterizing them with a hot iron;

- use of antidotes;

- applying reptile skin to the buboes;

- pulling out disease using magnets.

However, medieval medicine was not hopeless. Some doctors of that time advised patients to stick to a good diet and wait for the body to cope with the plague on its own. This is the most adequate theory of treatment. Of course, under the conditions of that time, cases of recovery were isolated, but they still took place.

Only mediocre doctors or young people who wanted to gain fame in an extremely risky way took on the treatment of the disease. They wore a mask that looked like a bird's head with a pronounced beak. However, such protection did not save everyone, so many doctors died after their patients.

Government authorities advised people to adhere to the following methods of combating the epidemic:

- Long distance escape. At the same time, it was necessary to cover as many kilometers as possible very quickly. It was necessary to remain at a safe distance from the disease for as long as possible.

- Drive herds of horses through contaminated areas. It was believed that the breath of these animals purifies the air. For the same purpose, it was advised to allow various insects into houses. A saucer of milk was placed in a room where a person had recently died of the plague, as it was believed to absorb the disease. Methods such as breeding spiders in the house and burning large numbers of fires near the living area were also popular.

- Do whatever is necessary to kill the smell of the plague. It was believed that if a person does not feel the stench emanating from infected people, he is sufficiently protected. That is why many carried bouquets of flowers with them.

Doctors also advised not to sleep after dawn, not to have intimate relations and not to think about the epidemic and death. Nowadays this approach seems crazy, but in the Middle Ages people found solace in it.

Of course, religion was an important factor influencing life during the epidemic.

Religion during the bubonic plague epidemic

"Black Death" is a disease that frightened people with its uncertainty. Therefore, against this background, various religious beliefs arose:

- The plague is a punishment for ordinary human sins, disobedience, bad attitude towards loved ones, the desire to succumb to temptation.

- The plague arose as a result of neglect of faith.

- The epidemic began because shoes with pointed toes came into fashion, which greatly angered God.

Priests who were obliged to listen to the confessions of dying people often became infected and died. Therefore, cities were often left without church ministers because they feared for their lives.

Against the background of the tense situation, various groups or sects appeared, each of which explained the cause of the epidemic in its own way. In addition, various superstitions were widespread among the population, which were considered the pure truth.

Superstitions during the bubonic plague epidemic

In any, even the most insignificant event, during the epidemic, people saw peculiar signs of fate. Some superstitions were quite surprising:

- If a completely naked woman plows the ground around the house, and the rest of the family members are indoors at this time, the plague will leave the surrounding areas.

- If you make an effigy symbolizing the plague and burn it, the disease will recede.

- To prevent the disease from attacking, you need to carry silver or mercury with you.

Many legends developed around the image of the plague. People really believed in them. They were afraid to open the door of their house again, so as not to let the plague spirit inside. Even relatives fought among themselves, everyone tried to save themselves and only themselves.

The situation in society

The oppressed and frightened people eventually came to the conclusion that the plague was being spread by so-called outcasts who wanted the death of the entire population. The pursuit of the suspects began. They were forcibly dragged to the infirmary. Many people who were identified as suspects committed suicide. An epidemic of suicide has hit Europe. The problem has reached such proportions that the authorities have threatened those who commit suicide by putting their corpses on public display.

Since many people were sure that they had very little time left to live, they went to great lengths: they became addicted to alcohol, looking for entertainment with women of easy virtue. This lifestyle further intensified the epidemic.

The pandemic reached such proportions that the corpses were taken out at night, dumped in special pits and buried.

Sometimes it happened that plague patients deliberately appeared in society, trying to infect as many enemies as possible. This was also due to the fact that it was believed that the plague would recede if it was passed on to someone else.

In the atmosphere of that time, any person who stood out from the crowd for any reason could be considered a poisoner.

Consequences of the Black Death

The Black Death had significant consequences in all areas of life. The most significant of them:

- The ratio of blood groups has changed significantly.

- Instability in the political sphere of life.

- Many villages were deserted.

- The beginning of feudal relations was laid. Many people in whose workshops their sons worked were forced to hire outside craftsmen.

- Since there were not enough male labor resources to work in the production sector, women began to master this type of activity.

- Medicine has moved to a new stage of development. All sorts of diseases began to be studied and cures for them were invented.

- Servants and the lower strata of the population, due to the lack of people, began to demand a better position for themselves. Many insolvent people turned out to be heirs of rich deceased relatives.

- Attempts were made to mechanize production.

- Housing and rental prices have dropped significantly.

- The self-awareness of the population, which did not want to blindly obey the government, grew at a tremendous pace. This resulted in various riots and revolutions.

- The influence of the church on the population has weakened significantly. People saw the helplessness of the priests in the fight against the plague and stopped trusting them. Rituals and beliefs that were previously prohibited by the church came into use again. The age of “witches” and “sorcerers” has begun. The number of priests has decreased significantly. People who were uneducated and inappropriate in age were often hired for such positions. Many did not understand why death takes not only criminals, but also good, kind people. In this regard, Europe doubted the power of God.

- After such a large-scale pandemic, the plague did not completely leave the population. Periodically, epidemics broke out in different cities, taking people’s lives with them.

Today, many researchers doubt that the second pandemic took place precisely in the form of the bubonic plague.

Opinions on the second pandemic

There are doubts that the "Black Death" is synonymous with the period of prosperity of the bubonic plague. There are explanations for this:

- Plague patients rarely experienced symptoms such as fever and sore throat. However, modern scholars note that there are many errors in the narratives of that time. Moreover, some works are fictional and contradict not only other stories, but also themselves.

- The third pandemic was able to kill only 3% of the population, while the Black Death wiped out at least a third of Europe. But there is an explanation for this too. During the second pandemic, there was terrible unsanitary conditions that caused more problems than illness.

- The buboes that arise when a person is affected are located under the armpits and in the neck area. It would be logical if they appeared on the legs, since that is where it is easiest for a flea to get into. However, this fact is not flawless. It turns out that, along with the plague, the human louse is also a spreader. And there were many such insects in the Middle Ages.

- An epidemic is usually preceded by the mass death of rats. This phenomenon was not observed in the Middle Ages. This fact can also be disputed given the presence of human lice.

- The flea, which is the carrier of the disease, feels best in warm and humid climates. The pandemic flourished even in the coldest winters.

- The speed of the epidemic's spread was record-breaking.

As a result of the research, it was found that the genome of modern strains of plague is identical to the disease of the Middle Ages, which proves that it was the bubonic form of pathology that became the “Black Death” for the people of that time. Therefore, any other opinions are automatically moved to the incorrect category. But a more detailed study of the issue is still ongoing.

Engraving by Michael Wolgemuth

On April 8, 1771, Empress Catherine II ordered urgent measures to be taken to save Moscow from the bubonic plague. The Black Death, which was most rampant in the 14th century, four centuries later destroyed almost half of the then population of the Russian capital.

"Plague finally!" - we say when we hear about how one of our acquaintances or a famous singer suddenly says something crazy. "A plague on both your houses!" – we say in our hearts, tired of the news and turning off the TV. “We were called the black plague, they honored us with evil spirits!” – we joyfully sing along with the leader of the group “Alice”.

Her Majesty, Queen Plague has long become not a disease, but a popular meme. And even its original meaning has become quite distorted over the past years - so the above words of Mercutio from “Romeo and Juliet” in those years when the tragedy was written (1594-95) did not mean “How you all got me”, but precisely that a wish quick and terrible death. In the first printed version (the so-called “bad quarto”), either Shakespeare himself or his publisher even tried to soften this formula by replacing plague (“plague”) with poxe (“syphilis”). In the second edition, the Black Death was restored to its rights, so the most adequate translation of this phrase should be considered Pasternak’s version: “Plague take both of your families!”

But we no longer remember or feel all this. The deadening, terrible fear that grabbed our ancestors with an icy hand by the throat at the mere mention of the plague some one and a half hundred years ago has finally become a thing of the past with the invention of antibiotics. Only sometimes does it break out - it’s not for nothing that AIDS was given the nickname “the plague of the 20th century,” although in terms of their ability to spread and lethality, both diseases are, of course, incomparable. Well, with going into the past, everything is not so smooth either. People die from the plague even today, and if its signs are not recognized in time, the result is the same as 700 years ago. For example, from 1950 to 1994, 46 cases of plague were registered in the United States, 41% of those sick died - and no advances in modern medicine helped them.

Before the Black Death epidemic, the plague had visited humanity more than once, and the name of the disease itself had also been known for quite a long time. True, there is an opinion that until a certain time typhus, smallpox, cholera, and malaria were called plague - hence the confusion. The same Romans used the term pestis to designate a whole group of infectious diseases and fevers. Only recently have the methods of modern paleopathology, based on the analysis of ancient DNA obtained during excavations, made it possible to bring at least some clarity.

In Christian historical consciousness, the very first epidemic is considered to be that which occurred during the exodus of the Jews from Egypt - the so-called “Plague of the Philistines.” We know almost nothing about it, but the “plague of Thucydides,” which broke out in Athens during the Peloponnesian War (5th century BC), from which Pericles also died, upon closer examination turned out to be an epidemic of either typhoid fever , or salmonellosis. It is still unknown what exactly the “Antonine Plague” of 165 AD was, the victims of which were about 5 million people and two Roman emperors. But many historians today argue that the bloody furrow separating antiquity from the Dark Ages was carried out not by barbarian invasions, but by the “Justinian Plague” of 541, which killed, according to various estimates, from 50 to 100 million people throughout the empire. The effect was comparable to the consequences of a nuclear war in the minds of the creators of the Fallout series of games: cities were empty and destroyed, the economy fell into decay, the remnants of the population degraded, and the place of refined theology, rhetoric and decadent poetry was taken by sagas about the battles of heroes with dragons and other chthonic monsters.

By the way, the ancients were partly right that the plague is not one disease, but a whole family that has a common ancestor, Yersinia Pseudotuberculosis, which had much milder symptoms and was far from 100% lethal. The causative agent of the Justinian plague, recently reconstructed by paleopathologists, turned out to be not black death (Yersinia pestis), but a side branch from the same evolutionary tree, which passed without a trace and did not give direct descendants.

In addition, until the beginning of the 14th century, local epidemics occurred with some regularity in both Europe and the Arab world, which could have been caused, among other things, by early versions of the plague bacterium. But neither the “disease of saints and kings,” nor the Kiev pestilence of 1090, nor the epidemic of the “sacred fire” in France in 1235, nor the Egyptian plague of 1270, which wiped out the troops of the VIII Crusade, spread so widely and did not have such monstrous consequences.

Fragment of an engraving by Paul Furst

The Black Death itself originated in the area of Lake Issyk-Kul around 1338. The mechanism of primary infection also developed there: fleas became carriers, in whose stomachs a lump of plague bacteria, visible even with a strong magnifying glass, formed, preventing them from getting enough blood. The hungry flea, in a frenzy, began to bite one warm-blooded animal after another, spreading the disease further and further. It was transmitted to humans either from caravan camels that died along the way during the cutting of the carcass, or from the bobak marmot, whose fur was valued both in Asia and in Europe. Hunters who found many dead or dying animals skinned them and, without thinking about the consequences, resold them to traders. When bales with such fur were opened for resale or tax collection, fleas attacked everything and the plague reaped a bountiful harvest.

By the way, this channel of transmission of the plague still works to this day - for example, in 2013, teenagers in Kyrgyzstan were infected after catching a marmot to cook shish kebab from it. Of course, another group of carriers was the synanthropic rodents that accompany man in all his endeavors - mice and rats.

The original distribution area of the epidemic is best described, oddly enough, in the Russian Resurrection Chronicle of 1346:

“That same summer there was an execution from God on the people under the eastern country on the city of Ornach (the mouth of the Don) and on Havtoro-kan, and on Sarai and on Bezdezh (a Horde city between the Volga and Don rivers) and on other cities in their countries; the pestilence is strong on the Bessermens (Khivans) and on the Tatars and on the Ormens (Armenians) and on the Obezes (Abaza people) and on the Jews and on the Fryazs (residents of the Italian colonies on the Black and Azov Seas) and on Cherkassy and on all those living there."- that is, the lower reaches of the Volga, the Northern Caspian region, the Northern Caucasus, Transcaucasia, the Black Sea region and Crimea. Why the Black Death did not come to Rus' immediately, but only 5 years later and in a roundabout way is a mystery.

The starting point for the spread of the epidemic to Europe was the Crimean port of Caffa (Feodosia), which belonged to the Genoese, which at that time was the most important logistics hub on the route of goods from Asia to Europe. The fact that just in the year the epidemic began, the city was besieged by the Mongol army under the command of Khan Janibek gave rise to the version that the outbreak of the plague was the result of the Tatars using a kind of biological weapon.

Allegedly, it was the besiegers who began to fall ill first, and then the khan ordered the corpses of the dead to be cut into pieces and thrown over the wall using catapults. After the siege was lifted, the Genoese spread the plague throughout Europe on their trading ships.

Janibek himself died only 11 years later, and not at all from the plague, although the disease devastated the Mongolian capital Sarai. And although his army suffered losses, it retreated from the walls of Caffa, and did not remain lying under them - and yet in Europe the plague then gave almost one hundred percent lethality. Most likely, it was not a matter of biological weapons at all, but of rats that freely scurried between the besieged city and the Mongol camp. And also that Kaffa, in addition to spices, sandalwood and silk, also traded in slaves. The shortest trade route from it led straight to Constantinople - that is, to the largest metropolis of the Christian world. The conditions for the victorious march of the Black Death across Europe and the rest of the world were most favorable.

Then things went smoothly for the formidable queen. In the spring of 1347, the plague struck Byzantium, killing up to a third of the empire's subjects and half the population of Constantinople. Among the dead was Basileus’s heir, Andronik, who died from illness in just a few hours from dawn to noon. It was then that the Black Death revealed its new feature, which allowed it to deal such a terrible blow to medieval European civilization.

It should be noted that European and Arab doctors, at the very least, learned to fight the old versions of the disease by isolating the infected and opening the plague buboes, followed by cauterization. God knows what, but some of the patients still survived after such treatment. The problem was that this time the actual bubonic version of the plague was caught by very few people - about 10-15% of the total, and in most cases the disease spread in the form of so-called plague pneumonia. It was transmitted similarly to the flu - that is, by airborne droplets, developed instantly, spread immediately through the circulatory system, and plague buboes appeared not on external lymph nodes, but on internal organs. Until a person fell exhausted and began to spit up blood, he did not even realize that something was wrong with him, and continued to live his usual social life: he went to church, to the market and to a tavern with friends, infecting at the same time, everyone who came into contact with him.

Plague pneumonia developed extremely quickly - from several hours to a day and a half, and 99% of those sick were doomed. Queen Jeanne of Burgundy, nicknamed Lame, went to Mass at Notre Dame, someone in the back rows coughed - and the very next day the place of the First Lady of France was vacant. Medieval historian Jean Favier wrote:

The cities paid the greatest tribute: overcrowding was killing. In Castres, in Albi, every second family died out completely. Perigueux lost a quarter of its population at once, Reims a little more. Of the twelve chapters of Toulouse noted in 1347, eight were no longer mentioned after the epidemic of 1348. In the Dominican monastery at Montpellier, where there used to be one hundred and forty brothers, eight survived. Not a single Marseille Franciscan, like Carcassonne, survived. The Burgundian lament may allow for exaggeration for the sake of rhyme, but it conveys the author's amazement:

Year one thousand three hundred forty eight -

Eight out of a hundred remained in Nui.

Year one thousand three hundred forty nine -

In Bon, out of a hundred, nine remained.

The same picture was throughout Europe from Sicily to Norway. England was saved neither by the English Channel, nor by the minimal quarantine measures taken, nor by the general prayer services and religious processions held in all parishes on the initiative of the Archbishop of York. On August 6, the first cases appeared in the small coastal town of Melcom Regis. A few weeks later the plague came to Bristol, where "the living could scarcely bury the dead." In November she took London by storm... In total, England lost 62.5% of its population or approximately 3.75 million people.

"The Triumph of Death, Pieter Bruegel the Elder"

The Black Death came to Rus' only in 1352, and, as already mentioned, in a roundabout way, brought either by the Poles or Hanseatic merchants. The first on her way was Pskov, where the number of deaths was so high that 3-5 corpses were placed in one coffin. The population, distraught with horror, sent for the Novgorod Archbishop Vasily Kalika, so that with his prayer he would avert the wrath of God from their city. Vasily arrived, walked around the city with a religious procession, prayed over the sick - and he himself died of the plague on the way back. The Novgorodians gave him a magnificent burial and exhibited his body in the St. Sophia Cathedral, after which an epidemic also broke out in Novgorod. It was greatly facilitated by the Russian custom, in the event of pestilence, to erect a church in one day by the whole world - the joint work of many people, as well as religious processions, made its terrible work easier for the plague to the limit.

In 1387, the Black Death completely destroyed the population of Smolensk. According to the chronicler, only 5-10 people survived, and they left the dead city, closing its gates behind them. In Moscow, the plague took the entire family of Prince Simeon the Proud: himself, two young sons, his younger brother Andrei of Serpukhov and Metropolitan Theognost.

The instant death of many people over vast territories gave rise to collateral mortality. Let’s say if both parents died from the plague, and their little child somehow miraculously developed immunity, then he would still be unlikely to survive. Since the peasants of those times lived in crowded rural communities, they died no less than the city dwellers. Entire villages perished, and the survivors were afraid to leave their homes, afraid to sow grain, and even more so to take it to the infected cities. So survivors of the plague often died of starvation. In England, unattended livestock was destroyed by a foot-and-mouth disease epidemic; in total, the livestock was reduced by 5 times. If fires broke out in deserted cities, there was no one to put them out. States lost all levers of control, since the epidemic mowed down soldiers and officials in the same way as other mortals. The messengers sent with royal orders either died of the plague along the way, or they were shot from the walls of quarantined cities and castles, and the messages they brought were burned without reading, for fear of infection. Hunger, crowds of refugees wandering from one end to another and the destruction of the entire way of life created the ground for new epidemics.

Outbreaks of the plague were often accompanied by monstrous Jewish pogroms. The Jews, who lived in closed communities, were always suspected of practicing witchcraft; it was believed that they poisoned wells, throwing into them charmed fetishes made of toad skins and human hair. In France, mass burnings of Jews began in 1348. Almost the entire Jewish community of Paris was exterminated, and the corpses of those killed were thrown into the forests surrounding the city. In Basel, a huge wooden building was specially built, where all the Jews were driven and burned. Mass burnings were also carried out in Auxburg, Constance, Munich, Salzburg, Thuringen and Erfurt. In total, during the Black Death epidemic in Europe, 50 large and 150 small Jewish communities were destroyed.

Having completed its terrible tour of Europe and Western Asia, the plague went to sleep in abandoned villages, disastrous swamps and mass graves. However, not for long: three more times with an interval of 10 years (1361, 1371 and 1382) she tried to return, but those who survived the first and most terrible wave had already developed immunity, so that at each new round fewer and fewer people became ill and fewer recovered. More. The Black Death had to retreat and begin to change, adapting to new conditions.

In addition, humanity, taught by bitter experience, has managed to develop the basic principles of personal quarantine: when even rumors of an epidemic appear, go to a remote and sparsely populated area, avoid port cities and any cities in general, do not visit shopping arcades, general prayer services and mass gatherings, do not participate in funerals died from illness, and do not take food or things from strangers. Unfortunately, all these generally correct principles were based on the miasmatic theory of the spread of epidemics, which believed that the plague, like other infectious diseases, spread along with bad air. This is where the Old Russian word “vestiness” comes from. The most effective remedy against miasma, until the discovery of the plague bacillus in the middle of the 19th century, was considered to be the fumigation of contaminated premises and city streets with smoke from odorous chemicals and aromatic herbs. In Rus', huge bonfires were built for the same purpose.

The triumph of death. Fresco in the Oratorio dei Disciplini

The mass quarantine introduced by the authorities was based on the same principles. Infected houses, streets and neighborhoods were isolated, and priests were forbidden to visit infectious patients and perform any rituals on them. Those who died from the epidemic were forbidden to be buried in churches within the city; their bodies were either buried in remote areas or simply burned along with all personal belongings. However, these rules were often not followed by anyone. In Moscow, for example, there were simply no graveyards outside Zemlyanoy Gorod, so the dead were still buried in city parishes. By the 17th century, there were already more than 200 such cemeteries, which greatly contributed to the success of the plague of 1654-1656.

Towards the end of the 17th century, upon news of epidemics in neighboring countries, quarantine outposts began to be set up at the borders, where a passing foreigner could be detained for up to 6 weeks. Under Peter, these measures were put on a more or less regular basis. A decree “What should be done when receiving the first information about a pestilence from neighboring states” was sent to all governors-general and governors of the border regions.

There, in particular, it was prescribed that fires should be placed on both sides of the roads leading to the outposts “so that those passing through those fires... could be questioned about that pestilence under the death penalty.” Those arriving directly from those areas where the epidemic was raging were ordered to be detained at outposts “so that they would not have any communication with people.” The decree ordered that infected houses be burned along with all property and livestock, and that people be “taken to special empty places.”

Upon receiving news of an outbreak in Marseille of the “Château Plague” of 1720 (named after the captain of the ship on which it arrived there), which then spread to a number of cities in Provence, these measures were tightened. All French ships began to undergo mandatory sanitary inspection, and French merchants, in order to enter and import goods into Russia, had to receive a special “passport” from the Russian envoy in Paris. As the epidemic spread further, these measures also became stricter, and in 1721, French ships were completely denied access to Russian ports.

This time Russia was carried away. But if in peacetime primitive quarantine measures helped at least somehow, then in the event of a war, the very movement of huge armies and crowding in military camps turned the areas in which hostilities took place into real breeding grounds for infection. Until the advent of regular military medical service and vaccinations, armies often lost more people from disease than from enemy action.

During the next war with Turkey of 1768-1774, Russian troops entered Moldova, where the plague epidemic was just beginning. Returning soldiers and officers brought with them trophies, and with them fleas infected with the terrible Yersinia pestis. Already in 1770, an epidemic swept through Bryansk, claiming many thousands of lives. Next on her path was Moscow.

Plague bacillus under a microscope. Photo: wikimedia.org

Judging by the fact that the first infected people appeared in a residential building at the Moscow General Hospital, the primary source of the epidemic was most likely the wounded and their personal belongings brought to the city. Moscow life physician A.A. Rinder, when examining the patients, showed blatant incompetence and simply ignored the obvious plague buboes that emerged from many of them, declaring that the unfortunate people were suffering from ordinary fever. Meanwhile, in the shortest possible time, out of 27 people who fell ill with the “evil fever,” five remained alive. Senior doctor of the hospital A.F. Shafonsky organized minimal quarantine measures, and the epidemic seemed to have stopped. But Her Majesty the Plague Queen, as you know, loves to play tricks on her subjects.

In March 1771, several workers at the Great Cloth Yard in Zamoskvorechye fell ill with a “fever”. The administration of the manufactory reacted in full accordance with the unwritten code of capitalism - that is, it tried to minimize losses and prevent production from stopping. Nothing was reported to the city authorities, and those who died from the plague were buried secretly at night. When rumors of the disease finally reached Chief Police Chief Eropkin, Doctor K. Yangelsky was sent to the Great Cloth Yard, who confirmed the worst fears.

The corresponding rescript was immediately sent to the court in St. Petersburg. A parallel letter from Rinder and the chief doctor of the Pavlovsk hospital, I.Kh., also flew there. Kuleman, who did not want lower-ranking Russian doctors to question the competence of the Germans entrenched in the leadership of the Moscow medical service. As a result, Catherine refused the city authorities permission to introduce a complete quarantine, and all that Governor-General Saltykov could do with his power was to close the infected manufactory. But it was already too late.

The workers, who did not understand the meaning of quarantine measures and were at the same time scared to death, began to scatter around the outskirts of Moscow and the villages adjacent to the city, spreading the epidemic. The sick and dying appeared all over Moscow; the plague was also accompanied by panic, which immediately paralyzed all city life. Moscow University closed, all factories, workshops, shops and taverns stopped working. Up to a thousand people died a day, to which were added victims of fires, mass fights and pogroms. The nobles fled in horror and locked themselves in country estates, but the plague found them even there. The desperate Governor-General Saltykov gave up on everything and left for his estate in Marfino, followed by Chief of Police Yushkov and other major officials. The city was left without power.

Soon there was no one left to remove corpses from the streets. The remaining officials had to mobilize convicts sentenced to hard labor for this unpleasant work. Since there was no supervision over them, looting and robberies were added to the plague.

The slightest spark was enough for a social explosion. On September 11, at the peak of the epidemic, rumors spread throughout the city that a miraculous icon of the Bogolyubskaya Mother of God, capable of healing all diseases, was brought to the chapel at the Varvarsky Gate, but Moscow Archbishop Ambrose ordered it to be hidden. The alarm was instantly sounded, a crowd gathered... Further events were exhaustively described by Catherine herself in one of her letters:

Plague riot in Moscow. Watercolor by Ernest Lissner

In fact, such a crowd of people during an epidemic could only intensify the infection. But here's what happened. Part of this crowd began to shout: “The bishop wants to rob the treasury of the Mother of God, we must kill him.” Another part stood up for the archbishop; words led to fights; the police wanted to separate them; but ordinary police were not enough. Moscow is a special world, not a city. The most ardent ones ran to the Kremlin, broke down the gates of the monastery where the archbishop lives, plundered the monastery, got drunk in the cellars in which many merchants store their wines, and not finding the one they were looking for, one half went to the monastery called Donskoy, where they They took this venerable old man out and inhumanly killed him. The other part continued to fight while dividing the spoils.

Only after Lieutenant General E.D., who entered the city at the head of a detachment of 130 people with two cannons. Eronkin gave the order to shoot to kill, the crowd retreated, leaving behind Red Square strewn with the dead and wounded.

The plague riot finally managed to convince the empress that something serious was indeed happening in Moscow. She decided to send her, by that time already retired, favorite Grigory Orlov to fight the epidemic - obviously not without the secret hope that he himself would become one of the victims of the plague.

Having no knowledge of medicine, Orlov proved himself to be an excellent organizer. The measures he introduced were as clear as a tribunal verdict. Troops were brought into the city to restore order. Riots, robberies and looting were punishable by execution on the spot. All of Moscow was divided into several sanitary sections, each of which was assigned a doctor. The sick and poor were ordered to be provided with food, clothing and money at the expense of the treasury. Children left without parents were collected in closed orphanages. Special plague quarantine hospitals were created on the outskirts of Moscow. Concealing the sick or dead from the authorities was punishable by eternal hard labor, and those who denounced those hiding were given a bonus of 20 rubles. And, most importantly, it was finally forbidden to bury the dead within the city limits. Most of the Moscow cemeteries - Dorogomilovskoye, Pyatnitskoye, Preobrazhenskoye, Rogozhskoye and others - arose precisely during the epidemic of 1771 as plague ones.

Finally, the disease subsided. In November there were already 5,835 dead, and in December – even 805. Then their number only decreased, although cases of residual infection occurred until 1805. In honor of Count Orlov, Catherine ordered a special medal to be knocked out with the inscription “Russia has such sons in itself. For ridding Moscow of the Ulcer in 1771.” Doctor D.S., who helped Orlov develop quarantine measures. Samoilovich subsequently wrote many works on the plague, but was never accepted into the Russian Academy of Sciences.

In total, Moscow lost more than 100,000 people to the plague, that is, approximately half of its population. The entire traditional way of life was completely destroyed, so the survivors mainly joined the ranks of beggars and vagabonds. For the “wandering, elderly and crippled,” Catherine, by her decree, established a special hospital-almshouse on 3rd Meshchanskaya Street, which gave rise to the current Vladimirsky MONIKI. Over the next 100 years, this hospital was the main epidemiological center of Moscow.

The epidemic of 1771 was the last appearance of Her Majesty the Black Death, at least in Russian history. Focal outbreaks occurred in both the 19th and 20th centuries, but they were no longer so terrible, and the number of deaths in the worst cases did not exceed 5,000 people. But the genetic memory of the biological apocalypse experienced by our ancestors is still stored somewhere in the back of our subconscious, and the word “plague” itself still rolls around on the tongue, meaning either horror or delight in the face of all-conquering death.

Not long ago, one of my friends on LiveJournal had a little argument about plague pillars

, which can be seen in many European cities. They seem ridiculous and inappropriate to him.

I don’t think so. In addition to being aesthetically pleasing (especially in the cities of Central Europe), they are in keeping with the historical tradition of erecting some kind of sign as thanks for deliverance from the terrible epidemics that claimed millions of lives both in the medieval period and in more recent times.

Plague pillar in Vienna:

In order to understand what the plague, called "black death" , it is enough to cite just a few facts based on demographic data.

But I propose to go a little further and try to figure out why exactly in the middle of the 14th century Mortality from the plague (and other epidemics) in Europe reached proportions that absolutely stunned the imagination of contemporaries and descendants.

For the period from the 11th to the 13th centuries, called by Western historians "central Middle Ages"

, was characterized by a process of population and production growth, due to which, according to demographic estimates, by the end of the 13th century there were 70 - 80 million people in Europe.

This process is interrupted in the 14th century. By the middle of this century, the population of Europe is reduced to 50 million, and by the beginning of the 15th century - to 35 million people. That is, Over the course of a century, the European population has roughly halved

. It took (depending on the area) from 100 to 400 years to return to previous levels.

"Dance of Death" from the "Nuremberg Chronicle" (1493):

At the heart of this demographic collapse are frequent periods hunger , which Europe had not known for at least the previous 500 years.

Population growth in the Middle Ages was based on extensive, undiversified agricultural production, in which, with a constant lack of fertilizers, there was no complementary relationship between agriculture and livestock. The need for land for growing crops did not allow large spaces to be freed up for pastures (and this limited the ability to obtain fertilizers) and involved infertile lands in inefficient land use. As soon as the natural fertility of the land was depleted, in the absence of fertilizers it produced increasingly meager harvests, which caused food crisis .

In addition, an important factor was climate deterioration , which began precisely at the end of the 13th - beginning of the 14th centuries. Several bad years in a row took a heavy toll on harvests; Due to this, the rural population thinned out, which in turn affected the cities, which faced difficulties with the supply of food.

Made the situation even worse mass exodus of villagers to cities , where they hoped to find food for themselves. And this led to an even greater food problem in the cities and to a worsening of their already poor hygienic condition. Chronically malnourished populations concentrated in small spaces with unhealthy living conditions make easy victims epidemics , which spread quickly and are often repeated.

"The Triumph of Death"

(Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1562):

The worst such epidemic in the 14th century was the bubonic plague pandemic that swept through Europe and Asia from 1346 to 1353.

The cause of this epidemic was a bacillus Yersinia pestis , which is carried by 55 species of rat fleas. It only affects humans after too many rats have died from the disease. And the fact that in European cities, under the conditions that reigned in them unsanitary conditions , apparently there were hordes of rodents. The incubation period of bubonic (and pneumonic) plague is only 2 - 3 days, and the mortality rate in the Middle Ages reached 95 - 99% of those infected.

"The Fourth Horseman of the Apocalypse", personifying Death

(French miniature of the 15th century):

However, the other three horsemen: Conqueror, War and Famine (on white, red and black horses),

were no less relevant for the 14th century than Death on a Pale Horse.

The initial outbreak of the pandemic was recorded in the Himalayan region, from where the plague began to spread as the Mongol Empire increased contacts with the vast Asian regions and with Europe. In 1347, the Horde, besieging the Genoese colony in Crimea - Kafu, used catapults to throw several corpses of those killed from the plague inside the fortress; those who survived the siege carried the bacillus to Constantinople, and then throughout the West, starting with the coastal sea cities.

Funeral of plague victims

(European miniature of the 14th century):

During this plague epidemic, about 60 million people (in some regions from half to 2/3 of the population). In 1361 and 1369 and several more times, the epidemic repeated itself, claiming more and more human lives. In subsequent centuries, the plague also constantly visited European cities until the end of the 18th century (it was in the 17th - 18th centuries that mostly baroque plague pillars were installed in the cities of Central Europe, which have survived to this day).

Plague pillar in Olomouc, Czech Republic, recognized as a masterpiece of Baroque art

(built in 1716 - 1754, included in the UNESCO World Heritage List):

In Asian countries, plague epidemics lasted much longer. Thus, in India, more than 12 million people died from the plague between 1898 and 1963.

The “Black Death” of the mid-14th century did not escape our country.

The plague epidemic began its mourning procession across Rus' from the northwestern Russian principalities, which were in the closest ties with Western Europe. First to fall Pskov

where the plague came summer of 1352

from the cities of the Hanseatic League, Livonia and Lithuania. According to sources, there were so many victims that they put 5 corpses in one coffin, but they did not have time to bury them either.

Russian cities such as Glukhov

And Belozersk

were completely depopulated (according to the Nikon Chronicle, not a single inhabitant remained in them).

In the spring of the following 1353, the plague reached Moscow

. The victims of the epidemic were Metropolitan Theognost

, died March 11, 1353, Grand Duke of Moscow and Vladimir Simeon Ivanovich Proud

(d. April 27), his young sons Ivan and Semyon, as well as his younger brother - appanage prince of Serpukhov Andrey Ivanovich

(d. June 6).

As a result, the very existence of the Moscow princely dynasty, which had fought so hard for the grand ducal label over the previous 50 years, was in great doubt. Of all its representatives, the only ones left alive were weak and clearly incapable of independent rule. Ivan Ivanovich Krasny

, who inherited the throne after the death of his brothers, his son Dmitriy

, born in 1350 and by some miracle survived during the pestilence of 1353 (if anyone didn’t understand, this is the future Dmitry Donskoy), and also born on the fortieth day after his father’s death Vladimir Andreevich

, who will play a major role in the Battle of Kulikovo and go down in history under the name Brave

(by the way, initially it was Prince Vladimir Andreevich who was called Donskoy, and not his older cousin Dmitry. But I will definitely write a separate post about this).

As in Western Europe, the plague epidemic repeatedly returned to Rus'. Thus, in 1387, one of the largest cities in Eastern Europe almost completely died out from the plague. Smolensk . Chroniclers report that out of the entire population of the city, numbering several thousand, no more than 5 - 10 people remained alive!

There were terrible plague epidemics in Russia later. The most famous of them are the pestilences of 1603, 1654, 1738 - 1740, 1769 - 1772. And, of course, everyone knows the Moscow plague of 1771 - 1772 , which caused the famous "Plague Riot" , pacified by Grigory Orlov, during which the number of victims reached 57 thousand people.

However, the tradition of installing plague pillars did not appear in Russian cities. But this is not surprising, since such a practice was considered alien to Orthodoxy, which contrasts itself with Catholicism (note that plague pillars in Europe are a characteristic feature of Catholic countries). Instead of such pillars in Russia, as on the occasion of significant military victories, chapels and churches were built.

By the way, not only the Russian Orthodox Church was an opponent of plague pillars. Not long ago (in August of this year) I had a chance to visit the most beautiful Hungarian town Sentendre , located near Budapest. Since the end of the 16th century, it was inhabited mainly by Orthodox Serbs, who fled to Catholic, but still Christian Hungary from the Turks. This Serbian town in the very center of Hungary also survived the plague in the 18th century, and its Orthodox population, as a sign of gratitude against the epidemic, decided to install a plague pillar in one of the main squares, following the example of their Catholic neighbors. But local Orthodox priests opposed this. As a result, instead of a plague pillar in the center of Szentendre there is this monument, more like a monument on a grave than a memorial sign:

Perhaps this is correct. If only because the first plague pillars in Europe were placed precisely at the site of mass graves of victims of plague epidemics. But still, you must agree that this Orthodox “plague pillar” is significantly inferior in beauty to the Catholic ones. Is not it?

In my opinion, this is exactly the case when a compromise between Orthodoxy and Catholicism does not lead to the best result.

Therefore, in my opinion, it is better to adhere to our own national traditions: plague pillars in the Catholic countries of Central Europe and Orthodox chapels and churches in Russia are one of the confirmations of my point of view.

I would be interested to know what you, my dear friends and readers, think about this.

Thank you for attention.

Sergey Vorobiev.