How As already noted, the instability of the Versailles-Washington system manifested itself in a series of international conflicts and political crises. The most acute of them was the so-called Ruhr crisis, related to the solution of the reparation issue. This crisis reflected both Germany's growing opposition to fulfilling the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and the contradictions between its drafters - the Allied powers.

Openly proclaiming the central task of his foreign policy to revise the humiliating decrees of Versailles. Germany in the first post-war period did not have sufficient forces to implement it. Hence the tactics of “hidden counteraction” while simultaneously accumulating economic and military power and attempting to strengthen their international positions. Such tactics included the following areas of activity. In the early 1920s. German government and military circles paid special attention to creating the basis for restoring military potential. According to the doctrine of the Reichswehr commander, General Hans von Seeckt, the “small army” that existed in the Weimar Republic, and especially its 4 thousand-!1b!;; The officer corps was seen as a base for the rapid deployment of large-scale armed forces. In Germany, the Great General Staff continued to function secretly. Military production was almost completely preserved. It is no coincidence that in 1923 Germany came into fourth place in the world (after England, the USA and France) in the export of weapons and military materials.

In order to improve its international position, the German government quite effectively used two means: taking advantage of the contradictions between France and the Anglo-Saxon powers, as well as rapprochement with Soviet Russia. In the first case, Germany managed to enlist the support of England and USA in softening the conditions for reparation payments, in the second - to achieve the conclusion of the Treaty of Rapallo, which was considered in the Weimar Republic as a kind of leverage over the Allied powers.

The tactics of “hidden counteraction” were most clearly manifested in the execution, a. or rather, in Germany’s failure to fulfill its reparation obligations. By formally adopting the London Reparations Plan. developed at an inter-allied conference in the spring of 1921, the German government began to successfully sabotage it in the fall of that year, citing the extremely difficult financial situation. The expectation of a favorable attitude towards this line of behavior by the British and Americans was completely justified. In June 1922 The International Committee of Bankers, chaired by J. P. Morgan (the Morgan Committee), at a meeting in Paris announced its agreement to provide a loan to Germany subject to a reduction “to reasonable limits” in the amount of reparations it pays. Under pressure from British representatives, the reparations commission liberated the Weimar Republic in October 1922 from cash payments for a period of 8 months. Nevertheless, in November of the same year, the government of K. Wirth sent a note to the commission, which spoke about the insolvency of Germany and put forward a demand to declare a moratorium for 4 years and provide it with large loans.

For obvious reasons, this course of events Not suited France. At the beginning of January 1923, the French Prime Minister R. Poincaré issued an ultimatum from two

->ntov. Firstly, he demanded the establishment of strict con- Gul over the finances, industry and foreign trade of Germany, labs to force her to regularly make reparation contributions. Secondly, the Prime Minister said that in the event of an emergency

"single failure to pay reparations. France on the procedure for applying sanctions occupies Ruhrskaya region. January 9

- "2! reparation commission, and which dominant

- “Did the French play, stated non-compliance Hermann-:-< обязательства по поставке угля Франции в счетreparations.

adoring it as “intentional.” In one day. 11January. Franco-Belgian troops entered to the Ruhr.

Thus began the Ruhr crisis, which sharply aggravated the situation both in Germany itself and in the international arena.

The government of V. Cuno, having officially proclaimed a policy of “passive resistance” and calling on the population of the occupied territories to “civil disobedience”, recalled its diplomatic representatives from France and Belgium. General Seeckt in his memorandum advocated a defensive war. The sharp decline in the economy increased social tensions. The danger of new revolutionary explosions in Germany, combined with the threat of further destabilization of the European international order - this was the essence of the Ruhr crisis, which shook the foundations of the Versailles system -

In terms of the development of international relations, the Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr had the following consequences. The Ruhr crisis contributed to an even greater spread of revanchist sentiments in Germany, its orientation toward politics from a “position of strength.” The head of the new German government is Gustav Stresemann. a politician of very moderate views, stated: “I have little hope that through negotiations we will create a situation tolerable for us, allowing us to live in within Treaty of Versailles." The already conflictual relations between Germany and France, which in German political circles began to be called “enemy No. 1,” worsened. Events in the Ruhr accelerated the collapse of the Anglo-French Entente, turning the wartime “cordial agreement” into an acute confrontation in resolving German and other issues of the post-war world. In the alarming days of the crisis, the Allied powers could once again see how real the prospect of a Soviet-German rapprochement was, threatening them. Soviet Russia was the only one great powers, which strongly condemned the Franco-Bslgian war action. The VNIK’s appeal to the peoples of the world on January 13, 1923 declared: “The world has again been plunged into a state of pre-war fever. Sparks fly into the powder magazine created from Europe by the Treaty of Versailles.”

The Ruhr conflict was resolved on November 23, 1923, when the Ruhr mine owners and representatives of the Franco-Belgian control commission signed an agreement under which the former pledged to resume coal supplies to France, and the latter to begin withdrawing troops and ending the occupation of the occupied areas. However, this settlement did not address the underlying causes of the crisis, the reparation issue and the German problem as a whole. From the solution to these problems depended not only on further development, but also itself the existence of the Versailles-Washington treaty system.

SECTION II________

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS DURING THE TWO STABILIZATION PERIODS

The balance of power on the world stage, the development of international relations in 1924-1929. (general characteristics)

With the entry of capitalist countries into a period of economic and social stabilization, a new stage began in the history of international relations. This stage. being a logical continuation of the previous one, it had the following distinctive features.

In the 1920s the governments of the great powers that won the world war managed to find a common language and develop a coordinated line in resolving the largest international ardently&1em. The consensus reached became the basis for the further development of the Versailles-Washington system. Despite all its inconsistencies, the post-war world order, legally formalized in Paris and Washington, was not only preserved. but also in a certain sense strengthened. In any case, centripetal and constructive forces at that time prevailed over centrifugal and destructive tendencies.

Another characteristic feature of the period under review became widespread dissemination of pacifist ideas and sentiments. Perhaps. Never before have so many peacekeeping projects been put forward and so many conferences been held to ensure peace and international security as in the twenties. It is no coincidence that in historical literature the third decade of the 20th century. often called the "era of pacifism".

Unprecedented popularity of pacifist plans and programs was explained by the action of various factors: tragic consequences of the First World War and the general desire prevent such military conflicts in future: necessity restoration of the destroyed economy and financial system, which assumed stabilization of international relations as the most important condition; activation peacekeeping activities liberal and democratic intelligentsia. as well as the coming to power in a number of European countries of politicians whose foreign policy concept was based on the principles of pacifism (E. Herriot in France. J.R. Maclonald in England, etc.).

However, the most significant reason for the surge in pacifist aspirations lay in the very nature of the international situation that had developed by the mid-1920s. Its uniqueness lay in the fact that the government circles of all the great powers, without exception, although for different reasons, were interested in maintaining the peaceful status quo. The leading victorious powers (USA, England, France) opposed any attempts to forcefully deform the Versad-Washington system, the creators of which they were. The defeated states (primarily Germany), as well as powers that considered themselves “unjustly deprived” of the decisions of the Paris and Washington conferences (Italy and Japan), did not at that time have sufficient power for a military revision of the established international order and used diplomatic, i.e. peaceful means and methods for realizing their foreign policy goals - As for the Soviet Union, its party and state leadership, without abandoning the slogans of proletarian internationalism, concentrated its efforts on strengthening the international positions of the USSR based on the principles of peaceful coexistence. Not the least role in the formation of this course was played by the defeat of the “anti-party group” led by L.D. Trotsky, condemnation of its revolutionary maximalism. who denied the very possibility of building socialism in the USSR without the victory of the world revolution. J.V. Stalin, proclaiming the Soviet Union as a “lever” and “base” for the development of the world revolutionary process, defended the independent significance of socialist transformations in the country, which. in turn, required the creation of favorable foreign policy conditions, the maintenance of “world peace” and the normalization of relations with the capitalist powers. These were the real prerequisites for the “era of pacifism.”

The Versailles agreements put Germany in an extremely difficult situation. The country's armed forces were sharply limited. The German colonies were divided among themselves by the victors, and the bloodless German economy could henceforth rely only on those raw materials that were available on its greatly reduced territory. The country had to pay large reparations.

On January 30, 1921, a conference of the Entente countries and Germany concluded in Paris, establishing the total amount of German reparations at 226 billion gold marks, which must be paid over 42 years. On March 3, the corresponding ultimatum was handed to the German Foreign Minister. It contained a requirement to fulfill its conditions within 4 days. On March 8, having received no response to the ultimatum, Entente troops occupied Duisburg, Ruhrort and Düsseldorf; At the same time, economic sanctions were introduced against Germany.

On May 5, the Entente countries presented Germany with a new ultimatum demanding that they accept all new proposals from the reparation commission within 6 days (to pay 132 billion marks over 66 years, including 1 billion immediately) and fulfill all the terms of the Versailles Treaty on disarmament and the extradition of the perpetrators of the world war. wars; otherwise, the Allied forces threatened to completely occupy the Ruhr area. On May 11, 1921, the office of Reich Chancellor Wirth, two hours before the expiration of the ultimatum, accepted the terms of the Allies. But only on September 30, French troops were withdrawn from the Ruhr. However, Paris never stopped thinking about this rich region.

The volume of reparations was beyond Germany's strength. Already in the fall of 1922, the German government turned to the Allies with a request for a moratorium on the payment of reparations. But the French government, headed by Poincaré, refused. In December, the head of the Rhine-Westphalian Coal Syndicate, Stinnes, refused to carry out reparations deliveries, even under the threat of Entente troops occupying the Ruhr. On January 11, 1923, a 100,000-strong Franco-Belgian contingent occupied the Ruhr Basin and the Rhineland.

The Ruhr (after Upper Silesia was taken away from Germany under the Treaty of Versailles) provided the country with about 80% of its coal, and more than half of German metallurgy was concentrated here. The struggle for the Ruhr region united the German nation. The government called for passive resistance, which, however, began without any calls. In the Ruhr, enterprises stopped working, transport and postal services did not work, and taxes were not paid. With the support of the army, guerrilla actions and sabotage began. The French responded with arrests, deportations and even death sentences. But this did not change the situation.

The loss of the Ruhr led to a worsening economic crisis throughout the country. Due to the lack of raw materials, thousands of enterprises stopped working, unemployment increased, wages fell, and inflation increased: by November 1923, 1 gold mark was worth 100 billion paper. The Weimar Republic was shaking. On September 26, Chancellor Stresemann announced the end of passive resistance in the Ruhr area and the resumption of German reparations payments. On the same day, a state of emergency was declared. The refusal to resist the French activated right- and left-wing extremists, as well as separatists, in many areas of Germany. The communists blamed the government for the occupation of the Ruhr and called for civil disobedience and a general strike. With the help of the Reichswehr, the uprisings were suppressed in the bud, although there was blood: in Hamburg it came to barricade battles. In November 1923, the Communist Party was officially banned. On November 8–9, 1923, a coup attempt took place in Munich, organized by a previously little-known right-wing organization, the NSDAP.

From September 26, 1923 to February 1924, the Minister of Defense Gessler and the head of the Reichswehr ground forces, General von Seeckt, were given exceptional powers in Germany in accordance with the state of emergency. These powers in practice made the general and the army dictators of the Reich.

Great Britain and the United States were dissatisfied with France's intransigent position and insisted on negotiating to establish a more realistic amount of reparations. On November 29 in London, the reparations commission created two expert committees to study the issue of stabilizing the German economy and ensuring that it pays reparations. On August 16, 1924, a conference of European countries, the USA and Japan concluded its work there and adopted a new reparation plan by the American banker Charles Dawes.

In accordance with the Dawes Plan, France and Belgium evacuated troops from the Ruhr area (they began to do this on August 18, 1924 and finished a year later). A sliding schedule of payments was established (which gradually increased from 1 billion marks in 1924 to 2.5 billion in 1928–1929). The main source of covering reparations was supposed to be state budget revenues through high indirect taxes on consumer goods, transport and customs duties. The plan made the German economy dependent on American capital. The country was provided with 800 million marks as a loan from the United States to stabilize the currency. The plan was designed for German industrialists and traders to transfer their foreign economic activities to Eastern Europe. The adoption of the plan indicated the strengthening of US influence in Europe and the failure of France’s attempt to establish its hegemony.

Payment of reparations was to be made both in goods and in cash in foreign currency. To ensure payments, it was planned to establish Allied control over the German state budget, money circulation and credit, and railways. Control was carried out by a special committee of experts, headed by the general agent for reparations. Charles Dawes was called the savior of Europe, and in 1925 he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

On October 16, 1925, an international conference concluded in the Swiss city of Locarno, in which representatives of Great Britain, France, Belgium, Italy, Germany, Poland and Czechoslovakia participated. The conference adopted the Rhine Pact, which ensured the integrity of the borders between France, Belgium and Germany. The latter finally renounced its claims to Alsace and Lorraine, and France - its claims to the Ruhr region. The provision of the Treaty of Versailles on the demilitarization of the Rhineland was confirmed and the Dawes Plan was approved. By the way, the eastern German borders did not fall under the system of guarantees developed at Locarno, which was part of the anti-Soviet policy of the powers.

The settlement of the reparation issue and the liquidation of the Ruhr conflict created favorable conditions for the influx of foreign capital into Germany. By September 1930, the amount of foreign, mainly American, capital investment in Germany amounted to 26–27 billion marks, and the total amount of German reparation payments for the same period was slightly more than 10 billion marks. These capitals contributed to the restoration of industrial production in Germany, which already reached pre-war levels in 1927.

Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation

Yelabuga Institute of Kazan (Volga Region) Federal University

Department of General and National History, History of State and Law

Ruhr conflict 1923

I've done the work

Khamidullin N.R.

Elabuga – 2016

Plan

Introduction………………………………………………………………………………

International position of Germany after the World War: reparation payments……………….…………………….….

Occupation of the Ruhr: completion of the “policy of implementation”…………………………………………………….

Consequences and overcoming the Ruhr conflict………………………………………………………..…

Conclusion………………………………………………………

List of sources and literature used……………….

Introduction

The relevance of the topic of our work is more than obvious. At the present stage of development of international relations, we are seeing more frequent use of the words: “conflict”, “conflict resolution”, “conflict resolution”. Conflicts in the territory of the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Nagorno-Karabakh, the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict, the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict are just a small list of conflicts where unresolved contradictions between subjects of international law have led to armed clashes and numerous casualties. The evolution of the conflicts themselves does not stand still: modern conflicts are continuously developing new forms of conflict interaction, more socially dangerous, but at the same time more manageable. Therefore, the study and analysis of the stages of resolving and overcoming international conflicts, and in our case the Ruhr conflict, is especially important and is not questioned. The study of conflicts that occurred earlier will allow us to understand the reasons for their occurrence, the process of formation, structure, ways of development and regulation of international conflicts.

When writing the work, we used the following literature and articles. ArticleArshintseva O.A. "Reparations in British European Policy during the Ruhr Crisis of 1923" We used to reveal the problem of German reparations, as one of the central ones in European politics from 1919 to 1923, which subsequently became the cause of the crisis as a result of the French occupation of the Ruhr. The author comes to the conclusion that Great Britain had a decisive influence on the course of events and the results of the crisis, the main one of which was the revision of the reparation payment scheme in Germany. Emelyanova E.N. in his article “The Failed Revolution of 1923 in Germany” helped us reveal the first paragraph of our work. We have gathered information aboutthe international position of Germany after the World War, and the consequences of the war for Germany.Kotelnikov K.D. in the article “German-Soviet secret military negotiations in connection with the Ruhr conflict (1923)” describes the process of negotiations that resulted in secret military cooperation between Germany and the Soviet Union in the development of types of weapons directly prohibited for Germany by the Treaty of Versailles. In addition, from the article we learned about the decisive stage of rapprochement between Germany and Russia: after the negotiations in 1923. We used material for the second and partially for the third paragraph from the bookBonvechB. « StoryGermany" , in particular about the consequences of the Ruhr conflict, as well as overcoming the conflict.

Target study this workRuhr conflict 1923To achieve this goal, it is necessary to solve the following tasks: consider the international position of Germany after the World War; describe the occupation of the Ruhr; analyze the consequences and overcoming the Ruhr conflict.

The structure of the work is determined by the content of the topic of the test and consists of an introduction, three paragraphs, a conclusion and a list of sources and literature used.

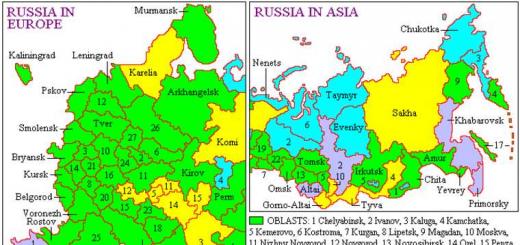

§ 1. International position of Germany after the World War: reparation payments

The Versailles Peace Treaty of 1919 stated that it was Germany that should bear full responsibility for the outbreak of the First World War. The treaty ordered Germany to return Alsace and Lorraine to France, the left bank of the Rhine with the cities of Koblenz, Mainz and Cologne to be transferred to the Entente (France and Great Britain) for 15 years, for the same period the management of the Saar Basin region was transferred to the League of Nations, part of the German territories was given to Belgium, Poland, Denmark and Czechoslovakia. Germany lost the large Baltic ports of Memel (Klaipeda) and Danzig (Gdansk). The victorious powers divided the German colonial lands among themselves. In total, the German Empire lost 70 thousand km², or an eighth of its territory, and human resources were reduced by 1/12 due to these losses.

The Treaty of Versailles established the complete demilitarization of Germany as a prerequisite for a general and widespread limitation of armaments. Under the terms of the agreement, the General Staff was dissolved, a significant part of the fortifications was destroyed, the relevant articles of the agreement abolished universal conscription in Germany, limited the size of the ground armies to 100 thousand volunteers and the officer contingent to 4 thousand people. The navy could have no more than 6 battleships, 6 light cruisers, 12 counter-destroyers, the same number of destroyers and 15 thousand sailors. But it was forbidden to have a submarine fleet, aviation and airships. The “extra” warships were dismantled by the allies.

The economic requirements of the treaty were also not lenient. Germany's foreign assets and patents were seized and sequestered. During the post-war decade, Germany was obliged to supply millions of tons of coal to France, Italy and Belgium, and to transfer half of its supply of chemical products and dyes to the victorious powers.

The defeat of Germany and the most difficult conditions of the Treaty of Versailles, which placed responsibility, moral and material, on the German Empire for the outbreak of the world war, could not but cause the deepest shock among the Germans. Society did not stop talking about the “invincibility on the battlefields” of German soldiers, who, however, were dealt a “treacherous stab in the back” by the revolutionaries, who took advantage of the opportune moment to proclaim the Weimar Republic.

Of particular importance was the size of reparations, to determine which a special commission was formed from representatives of the Entente countries. The calculations were based on the amounts of all military debt obligations, including rent payments from allies to each other. The commission determined that the amount of reparations over 30 years should be 132 billion gold marks. Payment terms or struggle to ease the financial burden, and became for the Weimar Republic, formed in August 1919 ( named after the constitution adopted in the city of the same name. In government land of Germany divided into 15 lands and 3 independent cities), the key theme of all foreign policy events and negotiations, significantly influencing and generally complicating the domestic political situation. The birth of the republic in an atmosphere of hopelessness about the military future of Germany became a unique reaction of society to the inability of the government to end the war with dignity.

All German parliamentary parties insisted that there was no legal basis for the decision of the Entente countries. However, vae victis: the reality of the threat of French occupation of the territory of the German state remained real and quite feasible, therefore supporters of the “policy of fulfillment” of the terms of the peace treaty inevitably had to prevail in the Weimar parliament, which is what actually happened. This development of events was also prompted by the hope for a likely revision of post-war agreements in the future and, by signing the Treaty of Versailles in May 1919, the German delegation expected to use every opportunity for further negotiations, changes and clarifications. Over the next two years, German politicians at conferences in Paris and London insist on reducing the size of reparation payments. The Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Weimar Republic, W. Rathenau, is trying to convince the victorious powers that their demands are unrealistic and impracticable. He managed to get Soviet Russia to abandon claims for reparations, but the government failed to achieve any noticeable and positive changes for the republic in this “reparations confrontation.”

Continuously growing public debts and reparation payments undermine the stability of the German currency. Rapid inflation - in the fall of 1923 the gold mark was worth almost forty million paper marks - dealt a severe blow to the well-being of the population. Under these conditions, a government crisis was inevitable, which is what happened: the cabinet of J. Wirth, a supporter and one might even say the founder of the “policy of implementation”, came to power: it was the position of Wirth and Rathenau that received this name.

The speech of the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Weimar Republic in Genoa was an obvious demonstration of German diplomacy's commitment to the terms of the Versailles agreements and readiness to cooperate with the victorious powers. However, this demonstration aroused the indignation of reactionary-nationalist German politicians.

The foreign policy activities of the government of the Weimar Republic noticeably intensified towards the next deadline for reparation payments in 1922: J. Wirth tried to negotiate with London and Paris an additional loan or a long-term moratorium. An extensive program of financial and economic reforms in Germany was proposed to the French authorities by the Minister of Finance of the Republic, which should create a reliable foundation for the “policy of implementation”. However, a meeting of bankers in the French capital opposed the loan, and all negotiations between German diplomats ended in vain.

The foreign policy activities of J. Wirth's cabinet were also hampered by the position of German industrialists, who did not stop sabotaging government measures to pay reparations. At a meeting of businessmen in the German North-West in June 1922, Stinnes openly called for thwarting all attempts by Germany to fulfill its reparation obligations, declaring the threat of the French occupation of the Ruhr mythical and untenable. Subsequently, the tone of the speeches of the leader of big capital and the printed publications belonging to him became openly defiant: “Deutsche Allgemeina Zeitung” published on the front page of the issue dated June 7, 1922 in large print the conditions and principles on which the Germans could agree to pay reparations: the Allies were withdrawing their troops from all occupied territories, including the Saar Basin; refuse the 26% tax on foreign trade turnover, grant Germany the right to free trade with Danzig, change the Upper Silesian borders in favor of Germany and abandon the “most favored nation right” assigned by the allies.

Thus, the dire economic problems caused by Germany's defeat in the war, the preceding Allied blockade and the subsequent huge reparations inevitably pushed the Weimar government to implement a "policy of implementation." Its main supporters and organizers, Reich Chancellor Wirth and Foreign Minister of the Republic Rathenau, saw the prospect of such a direction in the hope of a possible revision of post-war agreements in the future and easing the financial burden. However, attempts by German diplomacy to change the situation for the better were unsuccessful. The pressure from the victorious powers only intensified, which in turn contributed to the activation of the nationalist opposition and supporters of the “politics of disasters”, who did not even stop at the physical elimination of their political opponents.

Inevitable under such conditions, the collapse of the national currency in the winter of 1923 became the most spectacular economic disaster of the twentieth century. Rampant hyperinflation gave the first period of the Weimar Republic a chaotic character. The political significance of the seemingly purely economic factor, inflation, was enormous, since it was this factor that contributed to the promotion of the German Nazis to the forefront of the international political context. This episode in the economic history of the Weimar Republic clearly and convincingly confirmed that financial difficulties influence and even determine the direction of political development.

Thus, defeat in the First World War and the most difficult conditions of the Versailles Peace Treaty, which placed on the German Empire the full measure of moral and material responsibility for the outbreak of a global military conflict, contributed to the intensification of the revolutionary movement in the country, the proclamation of the Weimar Republic, and largely determined the prospects and features existence of a new state. The social, economic and political state of the Weimar Republic, first of all and to a large extent, depended on the influence of foreign policy factors. Foreign policy dominated domestic policy throughout the existence of the Weimar state. The terms of payment of reparations and the struggle to alleviate the financial burden became the key theme of all foreign policy events and negotiations for the Weimar Republic, significantly determining, and generally complicating, the internal political situation.

§ 2. Occupation of the Ruhr: completion of the “policy of implementation”

By the spring of 1921, Germany was able to pay only 40% of the preliminary amount determined by the Treaty of Versailles. This meant that Germany had to pay out the remaining billions of dollars at an annual rate of 2.5 billion just to pay off interest and another 0.5 billion to reduce debt. Thus, the annual tranche amounted to 6% of German GDP, and it was absolutely unthinkable to replace all this with gold or currency.

Paris decides to improvise, although it has been announced more than once, but, nevertheless, unexpected for all political players in the international arena: on January 9, 1923, France accuses Germany of violating debt obligations, and two days later the Franco-Belgian military contingent takes over The Ruhr, Germany's main coal basin and its industrial heart, was home to 10% of the population, produced three-quarters of Germany's iron, coal and steel and had the world's densest railway network. The military accompanies a group of mining engineers who take control of the extraction and shipment of coal, by the way, in accordance with the letter of the corresponding article of the Treaty of Versailles. The Foreign Ministry of the Weimar Republic sent a note to the ambassadors of France and Belgium; Great Britain publicly condemned the French invasion, but did not take any practical action to counter it.

The policy of "fulfillment" did not survive its supporters - the death of Rathenau and the fall of the Wirth cabinet in November 1922 brought an end to this governmental period of the Weimar Republic, which was replaced by the first "unalloyed capitalist" government of Wilhelm Cuno, a German entrepreneur and non-partisan politician. After the French invasion of the Ruhr, Cuno formulated and proclaimed the principles of the new foreign policy of the Weimar Republic, called by the creator himself the “policy of passive resistance,” the essence of which was a call not to submit to illegal demands. The payment of reparation sums was suspended, the administrative apparatus, industry and transport were paralyzed by a general strike. Certain departments and enterprises refused to comply with the orders of the French. The government also announced its support for the strikers, although the only government action in this direction was the issue of special money.

The French in the occupied territory did not hesitate in choosing punitive means: provocations, threats and the use of military force became commonplace. Meanwhile, inflation rates continued to rise uncontrollably and unemployment tripled. Under these conditions, nationalists became more active again, calling for a boycott of the strikes, but for the first time since 1919, not they, but the republic received popular support. However, neither strikes nor sabotage caused serious damage to French requisitions. German business, fearing to lose control of the market, chose to resume coal supplies. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic warned the governments of France, Belgium, Great Britain, the USA, Italy and Japan about continuing the “policy of passive resistance” until the withdrawal of Entente troops from occupied German territories. German diplomacy agrees to set the amount of reparations at 30 billion gold marks, but requires foreign loans to cover the debt. The republic proposes to entrust the final solution to the reparation problem to a special international commission. However, these proposals do not find a response among the allies. The collapse of the Reichsmark at the end of 1923 led to the resignation of the Cuno cabinet and the disastrous end of the “policy of passive resistance.

Thus, the change of government cabinet and the change in the nature of foreign policy from “implementation” to “passive resistance” in the context of the ongoing economic crisis and occupation of the Ruhr did not lead to any fundamental changes and improvements in the international status of the Weimar Republic.

On January 11, 1923, detachments of Franco-Belgian troops of several thousand people occupied Essen and its surroundings. A state of siege was declared in the city. The German government responded to these events by recalling by telegraph its ambassador Mayer from Paris, and envoy Landsberg from Brussels. All German diplomatic representatives abroad were instructed to present in detail to the respective governments all the circumstances of the case and to protest against the “violent policy of France and Belgium, contrary to international law.” Germany's formal protest was stated on January 12, 1923, in the German government's response to the Belgian and French note. The fact that the army crosses the border of unoccupied German territory with wartime composition and weapons characterizes France’s actions as a military action.” British diplomacy continued to remain an outwardly indifferent witness to developing events. She assured France of her loyalty.

But behind the diplomatic scenes, England was preparing the defeat of France. D'Abernon conducted continuous negotiations with the German government on methods of fighting against the occupation. The German government received advice to respond to the French policy of occupation of the Ruhr with “passive resistance”. The latter was to be expressed in organizing the struggle against France’s use of the economic wealth of the Ruhr, as well as in sabotage of occupation activities authorities.

The initiative to pursue this policy came from Anglo-American circles. D'Abernon himself strongly attributes it to American influence. As for British diplomacy, as facts show, it not only had no real intention of keeping Poincaré from the Ruhr adventure, but secretly sought to inflame the Franco-German conflict. Curzon made his demarches only for appearances against the occupation of the Ruhr; in fact, he did nothing to prevent its implementation. Moreover, both Curzon and his agent, the English ambassador in Berlin, Lord d'Abernon, believed that the Ruhr conflict could mutually weaken both France and Germany. And this would lead to British dominance in the arena of European politics.

The Soviet government took a completely independent position on the issue of occupation of the Ruhr. Openly condemning the capture of the Ruhr, the Soviet government warned that this act not only could not lead to the stabilization of the international situation, but clearly threatened a new European war. The Soviet government understood that the Ruhr occupation was as much the result of Poincaré’s aggressive policy as the fruit of the provocative actions of the German imperialist bourgeoisie, led by the German “people’s party” of Stinnes. Warning the peoples of the whole world that this dangerous game could end in a new military fire, the Soviet government, in an appeal to the Central Executive Committee on January 13, 1923, expressed its sympathy for the German proletariat, which was becoming the first victim of the provocative policy of disasters pursued by the German imperialists.

§ 3. Consequences and overcoming the Ruhr conflict

As a result, Germany lost 88% of coal, 48% of iron, 70% of cast iron. Germany was under threat of economic collapse. The fall of the German mark became catastrophic, and money depreciated at an unprecedented rate. In addition, the French began repression. Some coal miners, including Fritz Thyssen , were arrested. Krupp was warned about the sequestration of his enterprises. There was a wave of arrests of German government officials in Ruhr and Rhineland regions.

The crisis in Germany had a negative impact on England and throughout Europe. The decline in the purchasing power of the German population led to a fall in English exports and an increase in unemployment in England. At the same time, the French franc began to fall. All this caused disorganization of the European market. In Germany, there was a sharp increase in right-wing radical, nationalist and revanchist movements and organizations. Throughout Germany and especially in Bavaria , secret and overt organizations of a military and nationalist nature were formed.

Although the Ruhr conflict did not end, the policy of "passive resistance" did. But Germany’s relations with France finally lost perspective, and the Weimar Republic began to look for other guidelines in its foreign policy. Moreover, identifying them was not particularly difficult. In the summer of 1924, Great Britain and the United States initiated an international conference to overcome the Ruhr crisis on the basis of solving the reparation problem, the search for which had already been carried out by two expert committees that studied aspects of stabilizing the German mark and ways of “accounting for and returning capital to Germany.”

The German government realized that it would not be possible to overcome the severe crisis on its own, and it was necessary to seek help from an external force, which, as it became clear, only the Anglo-Saxons could provide. The Weimar Republic begins to persistently seek support from the United States and Great Britain. At the end of 1923, the Germans were able to obtain a large loan from them. Then the Weimar Republic signs a trade agreement with the United States, thus removing France from German affairs and solving the problem of reparation payments. In the spring of 1924, the recommendations of the reparation commission were developed, known as the “Daues Plan”, named after the head of the expert committee, who proposed to allocate a large international loan to Germany to stabilize the Reichsmark and inflation and correlate the payment of reparations with the restoration of the German economy. At the London Conference, where, after discussing all issues, representatives of Germany were invited, the delegation of the Weimar Republic pointed out the need to “resolve the issue of the military evacuation” of the Ruhr, occupied by Belgian and French troops. After the start of the Dawes Plan, a stream of overseas loans poured into the Weimar Republic. The export of capital from the United States to Germany, carried out in the form of Americans buying up shares of German companies, made it possible to overcome the crisis in the economy. During this period, the German government decided to admit the country to the League of Nations under certain conditions, providing for the provision of permanent membership to the Weimar Republic, participation in the work of the secretariat and the immediate cleansing of the Ruhr region.

Stresemann began intensive negotiations with France and Great Britain, steadily paving the Republic's “path to the West.” In June 1925, France accepted the German draft guarantees and, on the eve of the Locarno Conference, the French even left the Ruhr ahead of schedule. On October 5, 1925, the Locarno Conference began, where Stresemann demanded equal representation for his country in the Secretariat and Council of the League and colonial mandates. Germany was required to agree to participate in economic and military sanctions against the aggressor, which for all participants in the conference was the USSR. The German delegation did not give such consent, and as Stresemann explained, in “the event of a war between the West and Russia, Germany will not be able to help the latter even indirectly.” Meanwhile, in Moscow, Soviet and German representatives concluded a trade agreement demonstrating “special friendly relations” between Berlin and Moscow. The official document of the conference was a draft collective letter to Germany, containing an interpretation of the article that allowed Germany to participate in the activities of the League of Nations “to the extent possible, consistent with its military and geographical position.” A month before the end of 1925, the conference documents were signed in the British capital, and in the fall of the following year Germany was admitted to the League of Nations with a permanent seat on the Council.

In June 1929, at the Paris Conference, the directives of the “Dauwes Plan” were replaced by a new plan, developed by a group of financial specialists led by the American O. Jung, and reflecting the interests of private, mainly overseas, creditors of the Weimar Republic. The “Young Plan” provided for a certain reduction in annual payments to two billion marks, abolished the reparation tax on industry and reduced the taxation of transport, and provided for the elimination of foreign regulatory authorities. An important point of the plan and its consequence was the early withdrawal of the occupation military contingent from the Rhineland of Germany.

Thus, the industrial and financial crisis and the occupation of the Ruhr forced the government of the Weimar Republic to seek help from the United States and Great Britain. The support of these countries allowed Germany to cope with economic problems and gain the status of an active player in international politics. As a result of the Locarno Conference, the Weimar Republic was admitted to the League of Nations and was given a permanent seat on the Council. In many ways, this was facilitated by the personal and professional qualities of the head of the foreign policy department of the Weimar Republic, G. Stresemann, and the implementation of the directives of the “Dauwes Plan” and the “Jung Plan”.

Conclusion

The defeat in the First World War and the difficult conditions of the Versailles Peace Treaty, which placed on the German Empire the full measure of moral and material responsibility for the outbreak of a global military conflict, contributed to the intensification of the revolutionary movement in the country, the proclamation of the Weimar Republic, and largely determined the prospects and features of the existence of the new state . The social, economic and political state of the Weimar Republic, first of all and to a large extent, depended on the influence of foreign policy factors. Foreign policy dominated domestic policy throughout the existence of the Weimar state. The terms of payment of reparations and the struggle to alleviate the financial burden became the key theme of all foreign policy events and negotiations for the Weimar Republic, significantly determining, and generally complicating, the internal political situation.

The severe economic problems caused by Germany's defeat in the war, the preceding Allied blockade and the subsequent huge reparations inevitably pushed the Weimar government to implement a "policy of implementation". Its main supporters and organizers, Reich Chancellor Wirth and Foreign Minister of the Republic Rathenau, saw the prospect of such a direction in the hope of a possible revision of post-war agreements in the future and easing the financial burden. However, attempts by German diplomacy to change the situation for the better were unsuccessful. The pressure from the victorious powers only intensified, which in turn contributed to the activation of the nationalist opposition and supporters of the “politics of disasters”, who did not even stop at the physical elimination of their political opponents.

The change of government cabinet and the change in the nature of foreign policy from “implementation” to “passive resistance” in the context of the ongoing economic crisis and occupation of the Ruhr did not lead to any fundamental changes or improvements in the international status of the Weimar Republic.

The industrial and financial crisis and the occupation of the Ruhr forced the government of the Weimar Republic to seek help from the United States and Great Britain. The support of these countries allowed Germany to cope with economic problems and gain the status of an active player in international politics. As a result of the Locarno Conference, the Weimar Republic was admitted to the League of Nations and was given a permanent seat on the Council. In many ways, this was facilitated by the personal and professional qualities of the head of the foreign policy department of the Weimar Republic, G. Stresemann, and the implementation of the directives of the “Dauwes Plan” and the “Jung Plan”.

List of sources and literature used

Arshintseva O.A. Reparations in the European policy of Great Britain during the Ruhr crisis of 1923 // Izv. Altais. state un-ta. - 2006. - No. 4. - P. 47-50.

Kotelnikov K.D. German-Soviet secret military negotiations in connection with the Ruhr conflict (1923) // Tr. department history of modern and modern times. - 2015. - No. 14. - P. 147-155.

As early as March 1921, the French occupied Duisburg and Düsseldorf in the Rhineland demilitarized zone. This paved the way for France to further occupy the entire industrial area, and since the French now had control of the ports of Duisburg, they knew exactly how much coal, steel and other products were being exported. They were not satisfied with the way Germany fulfilled its obligations. In May, a London ultimatum was put forward, which set a schedule for the payment of reparations in the amount of 132 billion gold marks; in case of non-compliance, Germany was threatened with the occupation of the Ruhr.

Administered and occupied territories of Germany. 1923

Then the Weimar Republic followed the “policy of execution” - following demands so that their impossibility became obvious. Germany was weakened by the war, the economy was in ruins, inflation was rising, and the country was trying to convince the victors that their appetites were too high. In 1922, seeing the deterioration in the economy of the Weimar Republic, the allies agreed to replace cash payments with natural ones - wood, steel, coal. But in January 1923, the international reparations commission declared that Germany was deliberately delaying deliveries. In 1922, instead of the required 13.8 million tons of coal, there were only 11.7 million tons, and instead of 200,000 telegraph masts, only 65,000. This became the reason for France to send troops into the Ruhr basin.

Caricature of Germany paying reparations

Even before the entry of troops into Essen and its environs on January 11, large industrialists left the city. Immediately after the start of the occupation, the German government recalled its ambassadors from Paris and Brussels, and the invasion was declared “the violent policy of France and Belgium, contrary to international law.” Germany accused France of violating the treaty and declared a “war crime.” Britain chose to remain outwardly indifferent, while convincing the French of its loyalty. In fact, England hoped to pit Germany and France against each other, eliminate them and become the political leader in Europe. It was the British and Americans who advised the Weimar Republic to pursue a policy of “passive resistance” - to fight against France’s use of the economic wealth of the Ruhr, and to sabotage the activities of the occupation authorities. Meanwhile, the French and Belgians, starting with 60 thousand troops, increased their presence in the region to 100 thousand people and occupied the entire Ruhr region in 5 days. As a result, Germany lost almost 80% of its coal and 50% of its iron and steel.

Hyperinflation in Germany

While the British were playing their game behind the scenes, the Soviet government was seriously concerned about the current situation. They stated that the escalation of tension in this region could provoke a new European war. The Soviet government blamed both Poincaré's aggressive policies and the provocative actions of the German imperialists for the conflict.

Meanwhile, on January 13, the German government adopted the concept of passive resistance by a majority vote. The payment of reparations was stopped, Ruhr enterprises and departments openly refused to comply with the demands of the occupiers, and general strikes took place in factories, transport and government agencies. Communists and former members of voluntary paramilitary patriotic groups carried out acts of sabotage and attacks on Franco-Belgian troops. Resistance in the region grew, this was expressed even in the language - all words borrowed from French were replaced by German synonyms. Nationalist and revanchist sentiments intensified, fascist-type organizations were secretly formed in all regions of the Weimar Republic, and the Reichswehr was close to them, whose influence in the country gradually grew. They advocated mobilizing forces to restore, train and rearm the “Great German Army.”

Protest against the occupation of the Ruhr, July 1923

In response to this, Poincaré strengthened the occupation army and banned the export of coal from the Ruhr to Germany. He hoped to achieve a status similar to that of the Saar region - when the territory formally belonged to Germany, but all power was in the hands of the French. The repressions of the occupation authorities intensified, a number of coal miners were arrested, and government officials were arrested. In order to intimidate, a show trial and execution of Freikorps member Albert Leo Schlageter, who was accused of espionage and sabotage, was held. The German government repeatedly expressed its protest, but Poincaré invariably replied that “all measures taken by the occupation authorities are completely legal. They are a consequence of the violation of the Treaty of Versailles by the German government."

French soldier in the Ruhr

Germany hoped for help from England, but the British gradually realized that further adding fuel to the fire could be dangerous for themselves. England hoped that due to the occupation the franc would fall and the pound would soar. Only they did not take into account that because of this, the Germans lost their solvency, the devastation in the German economy destabilized the European market, British exports fell, and unemployment began to rise in Britain. In the last hope for help from the British, the German government on May 2 sent them and the governments of other countries a note with proposals for reparations. All issues were proposed to be resolved by an international commission. There was a new round of diplomatic battle. France strongly objected to the accusations of violating the Treaty of Versailles and demanded an end to passive resistance. In June, Chancellor Cuno revised his proposals slightly and put forward the idea of determining Germany's solvency at an "impartial international conference."

Occupation forces

A month later, England expressed its readiness to put pressure on Germany so that it would abandon resistance in the Ruhr, but subject to an assessment of the solvency of the Weimar Republic and the establishment of a more realistic amount of reparations. France again rejected any proposals, the world press started talking about a split in the Entente. Poincaré stated that the ruin of Germany was the work of Germany itself and that the occupation of the Ruhr had nothing to do with it. The Germans must give up resistance without any conditions. It was obvious that both France and Germany wanted a speedy resolution of the conflict, but both sides were too proud to make concessions.

General Charles Dawes

Finally, on September 26, 1923, the new Reich Chancellor Gustav Stresemann announced the end of passive resistance. Under pressure from the United States and England, France signed an allied agreement on a control commission for the factories and mines of the Ruhr. In 1924, a committee led by American Charles Dawes developed a new plan for reparations payments by Germany. The Weimar Republic was able to overcome inflation and gradually began to restore its economy. The victorious powers began to receive their payments and were able to repay the war loans received from the United States. In total, during the Ruhr conflict, the damage to the German economy amounted to 4 to 5 billion gold marks. In July-August 1925, the occupation of the Ruhr region ended.

Ruhr region

On January 10, 1923, a Franco-Belgian note was sent to Berlin. She notified the German government of Germany's violations of paragraphs 17 and 18 of the eighth section of the Treaty of Versailles. On January 11, 1923, the Franco-Belgian army began the occupation of the Ruhr. Germany recalled its ambassadors from Paris and Brussels and protested. Chancellor V. Cuno's call for passive resistance meant non-violent resistance to the occupation, namely sabotage of all activities of the occupation authorities and cessation of coal supplies. At the same time, the Ruhr crisis caused a new wave of revanchism in Germany.

The government of R. Poincaré expanded the area of occupation of Germany and it lost 88% of coal, 48% of iron, 70% of cast iron. Only in the fall of 1923 did Germany abandon the policy of passive resistance. Under pressure from England and the United States, France began the early evacuation of troops from the territory of the left bank of the Rhine. To ensure its security in the new conditions, France built a fortified defensive line along the Franco-German border. It was called the “Maginot Line” after its initiator, Minister of War A. Maginot.

The events of the Ruhr crisis of 1923 significantly changed the balance of power of the major powers in Europe. England and the USA put forward their own version of the solution to the reparations problem, which included stabilizing the economic and political situation in Germany.

Dawes Plan for Resolving the Reparations Question

Within the framework of the reparations commission, an international committee of experts was created to develop proposals for methods of balancing Germany's budget, stabilizing its currency and providing a stronger basis for its reparations payments. The committee was headed by the director of a large Chicago bank, Charles Dawes (Morgan banking group). In his message to Congress on December 6, 1923, the new President C. Coolidge emphasized the US commitment to assist Europe in order to ensure the collection of European debts, which, together with interest, amounted to $7,200 million. At the same time, German Foreign Minister G. Stresemann told the English Ambassador Lord E. d'Abernon about the need for Germany to participate in the work of the reparation commission as an equal partner. He also demanded firm promises for the withdrawal of troops from German territory.

At the London Special Conference of the Allied Powers (July-August 1924), the experts’ report, the “Dawes Plan,” was approved. On August 16, an agreement was signed between the German government and the reparation commission. The main objective of the plan was to actually ensure the payment of reparations by Germany. For this purpose, she was allocated a large international loan in the amount of 800 million gold marks. These funds were used to restore the German economy, and, above all, to heavy industry and to stabilize the financial system.

The Dawes Plan did not fix the total amount of reparations or the final date for payments. Annual payment amounts were established, but they were significantly reduced until the economic recovery process was completed. It was assumed that during the first year they would amount to 1 billion marks, then they would gradually increase and, having reached 2.5 billion marks by the 1928-1929 financial year, would stabilize at this level.

The sources of reparation payments were more clearly defined: deductions from the profits of German railways and industry, paid in the form of interest on specially issued bonds. Also, reparations were covered from the state budget. For this purpose, it was envisaged to introduce high indirect taxes on consumer goods (sugar, tobacco, beer, fabrics, shoes), as a result of which the burden of reparations was placed mainly on the German population.

The entire financial system of Germany was placed under the control of the Allied powers, but the control over the German military industry and national economy established by the Treaty of Versailles was abolished. The conference rejected the method of independent resolution of the reparation issue by France and recognized that conflict issues should be resolved by an arbitration commission headed by US representatives. French troops were withdrawn from the Ruhr Basin within one year, and economic sanctions on the Rhineland were immediately lifted.

Thus, the key to solving the problem of reparations and European debts was the Dawes Plan, the adoption of which changed the balance of forces in the international arena. First of all, the US position strengthened. Through reparations from Germany, England, France and other European countries began to regularly pay war debts to the United States. A wide flow of loans ensured American capital a dominant position in Germany and then financial hegemony in Western Europe.

The implementation of the reparation plan brought considerable financial benefits to German capital. Large foreign loans and the conclusion of favorable trade agreements made it possible to stabilize the German mark and not only quickly restore economic potential, but also modernize and develop German industry. Already in 1927, German exports exceeded pre-war levels. At the end of the 20s, the problem of new markets and sources of raw materials became acute. The economic strengthening of Germany contributed to the strengthening of its foreign policy positions, which inevitably led to a change in the balance of forces in the world system that emerged as a result of the First World War.