The sixteenth century is the most dramatic in the annals of England, the most glorious in the history of her literature. Are there any more picturesque figures in the gallery of English monarchs than Henry VIII and the great Elizabeth? Is there a victory more legendary than the defeat of the Spanish Invincible Armada? Is there a better poet than Shakespeare? In just a hundred years, a country on the outskirts of Europe, torn apart by civil strife, has turned into a great power, ready to fight for its primacy on all oceans, has gone almost from a broken trough to that England, which will soon be rightfully called the “Mistress of the Sea”.

The English Renaissance largely coincided with the Tudor era. The starting point should be considered the battle of Botsworth (1485), in which the king fell Richard III, the notorious villain from Shakespeare's play of the same name. Thus ended the wars of the Scarlet and White Roses. Both bushes, scarlet - York and white - Lancaster, were plucked to the flower, and Henry VII (1485-1509), the founder of the new Tudor dynasty, ascended the throne. The country was bled dry, the noble lords were killed, the French possessions were almost completely lost. Exactly seven years after the battle of Botsworth, in 1492, Columbus will discover America and the great race for the lands and treasures of the New World will begin. Most of this fat pie will be captured by Spain at first. But Henry Tudor (let us give him his due), despite his proverbial tight-fistedness, even then did not spare money for the development of the English fleet. And the results showed up - during the reign of his glorious daughter Elizabeth.

Not the lust for power of kings, but the very logic of things pushed the country, tired of strife, towards absolute monarchy. Henry VII was already guided by this, and even more so by his son. Henry VIII Tudor(1509–1547). In the end, he established complete power not only over the state, but also over the English church, proclaiming himself its supreme head (1534). This meant a break with the pope, but here the English were no longer the first; the anti-papal Restoration, initiated by the Wittenberg doctor of theology Luther, had by that time already triumphed in many German lands, as well as in Holland; over time, England will increasingly begin to orient itself towards its Protestant allies in Europe.

Henry VIII went down in history as a despot and "Bluebeard" on the English throne. He was a powerful and stubborn king, who strengthened and rallied the country, but at the same time split it along religious lines, which will reverberate a century later, in the era of the English Revolution and the Civil War. He was well educated, encouraged humanistic knowledge and Renaissance culture; it was under him that it became indecent for a young courtier not to play music, not to sing, not to write poetry. But this art lover mercilessly sent the great Thomas More to the scaffold, executed Count Sarri and a number of other court poets. A crowned knight who fought in tournaments for the honor of beautiful ladies and composed madrigals for them with his own hand, without much thought he betrayed his wife Queen Anne Boleyn to the executioner, and then Queen Elizabeth Howard; it’s good that the king did not execute all his wives (he had six of them), but only after one.

Heinrich's young son Edward VI, crowned in 1547 (he is described in Mark Twain's The Prince and the Pauper), was terminally ill and did not rule for long. After him, the throne was taken by Henry's daughter from his first marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Mary Tudor(1553–1558). Having married the Spanish Prince Philip, she abruptly turned England back to Catholicism. If some ten years ago those who remained faithful to the Catholic faith and did not recognize the royal "Act of Supremacy" were executed, now those who did not want to return under the authority of the Roman Church went to the stake and under the executioner's ax in tens and hundreds. Not surprisingly, when Mary the Catholic died, many English people breathed a sigh of relief. the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, the twenty-five-year-old Elizabeth Tudor (1558–1603), came to power and began one of the longest reigns in English history.

Time has shown how "Machiavelli in a skirt" was the new queen. Seriously educated, fluent in several languages, she also possessed exceptional political and diplomatic talents. At the time, there was prejudice against women on the throne; but Elizabeth managed to turn this “flaw” to her own advantage, turn it into a trump card. She gave the people an idea virgin queens as a symbol of the mystical union between the monarch and the state. The calculation was accurate: the woman is the sinful Eve, from whom all troubles, but the virgin is the Blessed Mary, from whom salvation comes. Elizabeth never married, the crown replaced her marriage crown. But besides - that's what's interesting! - remaining as betrothed to the English people, the queen, throughout her reign, negotiated marriage with many European rulers, using herself as a bait, and the proposed marriage as a powerful political lever, and skillfully, for years, led the contenders by the nose - in particular, the Spanish King Philip.

Gradually and without sudden movements, Elizabeth restored the Anglican Church, which, in its dogmas and structure, carried out a kind of compromise between Catholicism and Lutheranism. At the same time, two wings of radicals were formed: Catholics, supporters of the pope, and Puritans, who stood for complete liberation from the Roman rites, with each of which the state had to fight in the future. Especially dangerous were the Catholics, who were supported not only by the continental powers, but also by Scotland, independent of England, and the northern counties adjacent to it. Elizabeth had to fear the Scottish Queen Mary Stuart, her cousin, whom the northerners predicted for the throne of England. Fortunately for Elizabeth, Mary became entangled in amorous intrigues and, accused of involvement in the murder of her husband Lord Darnley, was forced to flee to England, where she soon found herself in the position of a prisoner. In 1586, when Spain was actively preparing for an attack on England, Elizabeth's secret service developed and carried out an operation (one might say, a provocation) to involve Mary Stuart in criminal correspondence with Spain and obtained all the evidence she needed. The Scottish queen was accused of plotting against England, tried and executed on February 8, 1587. The following year, the Spanish Invincible Armada of 134 ships with a huge expeditionary force on board sailed to the shores of England, intending to put an end to the “heretic queen” once and for all, but was decisively attacked by the English fleet in the English Channel, near the port of Calais. The rout was completed by a storm that sank many Spanish ships; only the miserable remnants of the Armada managed to return to their homeland.

The victory over the Invincible Armada inspired the British. The struggle against the Spaniards at sea, which had hitherto been episodic in nature - let us recall the pirate exploits of Francis Drake, knighted by Elizabeth! - took on the character of a real naval war: raids on the Spanish colonies in America, captures of the “gold” and “silver flotillas” going from there to the metropolis, attacks on port cities in Spain itself (for example, the capture of Cadiz in 1596). English volunteers and regular units fought in the Netherlands, helping the young Dutch Republic to resist the same Spaniards. At the same time, international trade expanded. Since 1554, there was a Moscow company, every summer sending its ships to Arkhangelsk; in 1581, the Levantine Company was founded to trade with the Middle East, and in 1600, the famous East India Company in the future. The British tried to gain a foothold on the shores of the New World. Sir Walter Raleigh made an expedition to Guiana, on the banks of the Orinoco River, where he searched for the golden land of El Dorado. On his own initiative, the first English colony in North America, Virginia, was founded.

All these news, innovations and achievements became public knowledge - through royal and parliamentary decrees, travel reports, leaflets with ballads on topical topics, through theatrical performance, finally. The horizons of the average Englishman were sharply expanded, the country felt itself standing at a great historical and geographical crossroads; and it is no coincidence that precisely these years of patriotic upsurge coincided with the years of the rapid flowering of English theater, poetry and drama.

The first English Renaissance poet, in fact, was already Geoffrey Chaucer (1340? -1400) - a contemporary of Boccaccio and Petrarch. His poem "Troilus and Cressida", along with the poems of the Italians, served as a direct model for the English poets of the 16th century from Wyatt to Shakespeare. But Chaucer's heirs failed to build on his achievements. The century after Chaucer's death was a time of poetic retreat, of a protracted pause. Perhaps this is due to the political instability of England in the 15th century? Judge for yourself. In the XIV century - the 50-year reign of Edward III - and the appearance of Chaucer. In the XV century - leapfrog of kings, the War of the Roses - and not a single great poet. In the 16th century, the 38-year reign of Henry VIII and the first flowering of poetry, then the 45-year reign of Elizabeth and all the highest achievements of the English Renaissance, including Shakespeare. It turns out that it is stability that is important for poetry, even if it is a tough power or despotism. There is something to think about here.

Of course, there were other reasons for the flourishing of English poetry. One, quite obvious, is the beginning of English printing, laid down by William Caxton in 1477. Since then, the number of books published in England has grown exponentially, directly affecting the rise of national education - school and university. Among the first books printed by Caxton were the half-forgotten poems of Chaucer, which thus became the property of the general reader.

However, even in the 16th century, the development of English poetry was uneven: after the execution of Earl Surry in 1547, there was a hitch for three decades - until such star names as Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser and Walter Raleigh appeared on the poetic horizon. Only in the 1580s does acceleration begin, and in the last decade of the Elizabethan era, a sharp rise: Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, John Donne.

English Renaissance culture is literary-centric. Alas, she cannot boast of masterpieces of painting or sculpture. Whether the lack of sun or the predominance of imagination over observation, characteristic of the peoples of the northern forests - Germans and Celts, affected here, we will not guess, but the fact remains: it was not the artist, but the poet who became the cultural hero of the British. Lyric writing in 16th-century England became a real mania. Not to mention the fact that the art of poetry was considered an indispensable part of chivalrous perfections and, as such, spread at court and in high society, the same poems - through schooling, theater, through books and leaflet ballads - entered the everyday life of almost all literate estates. . It is rare that a London journeyman could not, if necessary, compose a sonnet, or at least a couple of rhyming stanzas. Poetry was used not only to write friendly messages and love notes, but also scholarly, edifying, historical, geographical and so on books.

Age of rhymers; around and teeming

Poems, rhymes ... no, I'll save you from scribbling, -

Ben Jonson remarked sarcastically. Of course, versification is not yet poetry, and quantity does not always turn into quality ... although in the final analysis it does. The "Age of Rhymers" ("a Rhyming Age") was at its peak the age of poetic geniuses.

Poems, as we have already said, existed then at different levels. They could serve as a means of communication or an instrument of court career - high nobles were not insensitive to poetic flattery; and at the same time, poetry was perceived as an art, that is, a service to the beautiful. But to print his poems, that is, to make them the property of an outside public, was not appropriate for a poet-nobleman. Neither Wyatt nor Sidney lifted a finger to publicize their poems, their ambition did not go beyond the narrow circle of connoisseurs, “initiates”.

The situation began to change only towards the end of the century, when a new generation of raznochintsy writers entered literature. In an effort to enlist support, they dedicated their books to nobles - patrons of the arts or the monarch herself. A professional writer, in essence, cannot exist without material patronage - either a patron of the arts or the public. But the book trade was not yet sufficiently developed for the poet to live (or simply survive) on his poems. Only the flourishing of theaters in the Shakespearean era gave the poet-dramatist such an opportunity. Writers like Shakespeare and Johnson actually used both types of support - powerful patrons and theatrical crowds. Few managed to pass between Scylla and Charybdis, who wrote only “for the soul”: among them we will include, for example, the most talented student of John Donne, the priest George Herbert.

The poetry of the Renaissance was closely connected with the monarchy, with the life of the royal court. First major poet of the Tudor era John Skelton was first a Latin teacher to Prince Henry (the future king), and then something like a court jester. Author of the first English sonnets Thomas Wyatt romantic legend connects with Anne Boleyn, wife of Henry VIII; at the fall of the unfortunate queen, he only miraculously escaped death. George Gascoigne, the best poet of the middle of the century, all his life he tried to attract the attention of the court, to enter the favor of the ruling monarch - and died, barely reaching the desired goal. Philip Sidney, "English Petrarch", after his heroic death on the battlefield, was canonized as an exemplary knight and poet, acquired state funeral pomp and posthumous honors. Walter Raleigh, widely known as a soldier, politician, scientist and navigator, also had a first-class literary gift; Raleigh's verses to the "Virgin Queen" are among the best flowers in her poetic crown. Elizabeth herself dedicated poetry to her favorite, faithful "Sir Walter." Alas, after the death of the old queen, the wheel of Fortune turned: the powerful favorite turned out to be a prisoner of the Tower, and "the smartest head in the kingdom" eventually fell, cut down by the hand of the executioner.

Examples of how literary affairs intertwined with state affairs can easily be multiplied. Many of these stories are tragic; but the main thing is different. Poems were given importance. Yes, sometimes their authors were denounced, they could be arrested and even killed. And at the same time, princes and nobles considered it their duty to patronize poets, their works were copied and carefully stored. Without poets, the brilliance of the court, and the life of the state as a whole, and the inner world of an individual were incomplete. When Charles I was executed, he took two books with him to the scaffold: a prayer book and the pastoral-lyrical "Arcadia" by Philip Sidney. With this symbolic gesture, an entire era ended: in puritanical, bourgeois England, poetry took a fundamentally different place. Only a century and a half later, the Romantic poets resurrected the age of Shakespeare and re-evaluated the rich heritage of their Renaissance poetry.

Today, peering through the thickness of translucent time, we see: this is the whole Atlantis, a huge continent that has gone under water. Hundreds of poets, thousands of books, hundreds of thousands of lines of poetry. The thirty or so authors represented here are just a small selection of this amazing diversity. It is inevitably subjective, although it includes all the main names of that era. Of the poets of the first row, only Edmund Spencer presented nominally as a single sonnet: if it were a well-balanced anthology, at least one passage from his celebrated "The Faerie Queene," an allegorical poem in praise of Queen Elizabeth, should have been given.

Of the poets, relatively speaking, the second row had to be omitted with particular regret. John Davis, whose main things, the poems "Nosce Teipsum" and "Orchestra", would hardly have been perceived in scanty passages, and there was simply no room for more in the book. Of the poetesses, I would like to present, first of all, Isabella Whittney, published in 1573 the first book of poetry written by a woman in England. But her witty "Testament to Londoners", in which she unsubscribes to her readers all her beloved London - a detailed guide to the streets, shops and markets of the city - would inevitably lose both its authenticity and charm in translation. In general, the final part of the work on this book was the most painful, because I had to voluntarily give up a lot and a lot - for the sake of compactness and harmony, constantly calling for order to stray eyes. And yet I wanted to reflect the breadth and scope of the poetic era, the diversity of genres, themes and author's personalities. Along with the classic works of Shakespeare and Donne, the reader will find here also masterpieces of lyrics written by lesser known poets, for example, poems Chidika Tichborne composed before execution () or Thomas Nash. The book also includes poems by royalty: Henry VIII, Elizabeth and James I, as well as untitled songs and ballads. Dramatic poetry is represented by two passages from little-known tragedies - "The Werewolf" Thomas Middleton and George Chapman, and the genre of the epigram is half-forgotten Thomas Bastard.

This book covers mainly the Tudor era - from Henry to Elizabeth. The poetry of the time of Jacob Stuart is reflected only by the works of authors already familiar, that is, "smoothly passed" into the new century and new reign (including Donne and Johnson), as well as the names of their students George Herbert and Robert Herrick. The final section is dedicated to Andrew Marvellou; this is a completely different era - the English Revolution and Cromwell's protectorate. And yet (such is the inertia of style) Marvell's poetry is still largely Renaissance, it is the completion of the traditions of both English Petrarchists and English metaphysicians - a kind of epilogue and drawing a line under what the poets of the 16th century did.

If his predecessors were guided mainly by foreign literature, then he, on the basis of the same influences of Italian (and partly French) poetry, tried to create a purely English, national poetry.

He was neither from an aristocratic nor wealthy family, but at Cambridge University he received a solid classical education. In 1578 we find him in London, where his university companions introduced him to the houses of Sidney and Leicester, through which he probably gained access to the court. By this time, Spencer created the "Shepherd's Calendar" and, probably, the beginning of work on the poem "The Fairy Queen". Since Spencer was not financially secure to live without service, friends procured him a position as Lord Gray's personal secretary in Ireland.

In 1589, Spencer returned to London and lived in the capital itself or not far from it for about a decade, completely devoting himself to literary creativity. In 1590, the first three books of the poem "The Faerie Queene" dedicated to Queen Elizabeth were published in London, which brought him literary fame; despite the small annual pension assigned to him by Elizabeth, Spencer's material affairs were far from brilliant, and he began to think again about some official position. In 1598 he was sheriff in a small Irish town, but in that year there was a major uprising in Ireland. Spencer's house was vandalized and burned down; he himself fled to London, where he soon died in extremely distressed circumstances.

Shortly before his death, he wrote a prose treatise On the Present State of Ireland. Contemporaries argued that it was this essay, containing a lot of truth about the brutal exploitation and ruin of the Irish by the English authorities, that was the reason for the anger of Queen Elizabeth Spencer, who deprived him of any material support.

Spenser's first printed poems were his translations of Petrarch's six sonnets (1569); later they were revised and published together with his translations from the poets of the French Pleiades.

Much attention was drawn to another work by Spencer, the idea of which was inspired to him by F. Sidney, the Shepherd's Calendar (1579). It consists of twelve poetic eclogues, successively referring to the 12 months of the year. One of the bottoms tells how the shepherd (under the guise of whom Spencer deduces himself) suffers from love for the impregnable Rosalind, the other praises Elizabeth, “the queen of all shepherds”, in the third - under the guise of shepherds, representatives of Protestantism and Catholicism act, leading among themselves disputes on religious and social topics, etc.

Following the pastoral genre fashionable at that time, the poems of the Shepherd's Calendar are distinguished by their refinement of style and learned mythological content, but at the same time they contain a number of very lively descriptions of rural nature.

Spenser's lyric poems are superior in poetic merit to his earlier poem; they were published in 1591 after the great success of the first songs of his Fairy Queen.

Among these poems, some are still reminiscent of an early scholarly and refined manner (“Tears of the Muses”, “Ruins of Time”), others are distinguished by the sincerity of their tone and elegance of expression (“Death of a Butterfly”), and others, finally, by their satirical features (for example, “The Tale of mother Guberd, which tells the parable of the fox and the monkey).

The poem "The Return of Colin Clout" (1595) is also distinguished by satirical features.

The plot of the poem is based on the story of Spencer's invitation to revisit London and the court of Cynthia (that is, Queen Elizabeth), made to the poet Walter Raleigh, a famous navigator, scientist and poet (in the poem he appears under the pretentious name "Shepherd of the Sea"). Raleigh visited Spencer in Ireland in 1589. The poem tells of the reception of the poet at court and, under false names, gives colorful, lively descriptions of statesmen and poets close to the queen.

However, Spencer's most popular and most celebrated work was his poem The Faerie Queene.

This poem was partly modeled on the poems of Ariosto ("Furious Roland") and T. Tasso ("Jerusalem Delivered"), but Spenser also owes much to medieval English allegorical poetry and the cycle of chivalric romances about King Arthur. His task was to fuse these heterogeneous poetic elements into one whole and deepen the moral content of courtly poetry, fertilizing it with new, humanistic ideas. “By the queen of the fairies, I want to mean glory in general,” Spenser wrote about his poem, “in particular, I understand by her the excellent and glorious person of our great queen, and by the country of fairies - her kingdom.” He wanted to give his work the significance of a national epic and therefore created it on the basis of English chivalric traditions and insisted on its teaching, educational character.

The plot of the poem is very complex. The fairy queen Gloriana sends twelve of her knights to destroy the twelve evils and vices from which humanity suffers. Each knight personifies some virtue, just as the monsters they fight represent vices and delusions.

The first twelve cantos tell of the twelve adventures of the knights of Gloriana, but the poem remained unfinished; each knight had to take part in twelve battles, and only after that could he return to the queen's court and give her an account of his exploits.

One of the knights, Artegall, personifying Justice, fights the giant Injustice (Grantorto); another knight, Guyon, who is the personification of Temperance, fights Drunkenness and drives him out of the temple of voluptuousness.

The knight Sir Kalidor, the incarnation of Courtesy, falls upon Calumny: characteristically, he finds this monster in the ranks of the clergy and silences him after a fierce struggle. “But,” remarks Spencer, “at the present time, apparently, it again got the opportunity to continue its pernicious activity.”

The moral allegory is combined with the political one: Gloriana (Queen Elizabeth) is opposed by the powerful sorceress Duessa (Mary Stuart) and Geryon (King Philip II of Spain). In some dangerous adventures, the knights are helped by King Arthur (Elizabeth's favorite Earl of Leicester), who, having seen Gloriana in a dream, fell in love with her and, together with the wizard Merlin, went in search of her kingdom.

The poem would probably have ended with the marriage of King Arthur and Gloriana.

In the stories about the adventures of the knights, despite the fact that Spencer always gives them an allegorical meaning, there is a lot of fiction, amusement and beautiful descriptions. The Fairy Queen is written in a special stanza (consisting of nine poetic lines instead of the usual octave in Italian poems, that is, eight lines), called the "Spencer stanza." This stanza was adopted by English poets of the 18th century. during the period of revival of interest in the "romantic" poetry of Spencer and from them passed to the English romantics (Byron, Keats and others).

Wide development in English literature of the XVI century. lyrical and epic genres aroused at that time interest in the theoretical problems of poetry. In the last quarter of the XVI century. a number of English poetics appeared, discussing questions of English versification, poetic forms and style. Chief among these are The Art of English Poetry (1589) by George Puttenham and A Defense of Poetry (ed. 1595) by Philip Sidney. In the first, the author, proceeding from samples of ancient and Renaissance poetry, but with a full understanding of the originality of the English language, speaks in detail about the tasks of the poet, about the content and form of poetic works.

Sydney's Defense of Poetry, in turn, proceeds from ancient and European Renaissance theoretical premises about poetic creativity and from this side, by the way, condemns the English folk drama of the Shakespearean era, but at the same time speaks sympathetically about folk ballads and proclaims the realistic principle as the basis poetry. “There is not a single art form that is the property of mankind,” says Sidney, “which would not have natural phenomena as its object.” The poets of Puttenham and Sydney were probably also known to Shakespeare.

LECTURE 15

English poetry of the 16th century. The first humanist poets: J. Skelton, T. Wyeth, G. Sarri. The world of high feelings and ideals: F. Sidney, E. Spencer. Prose and dramatic genres in English literature of the 16th century. D. Lily: attempts at psychologism. T. Nash: the world without embellishment. Morals and interludes: a keen sense of life. Tragedies: the disturbing world of human passions. R. Green: the image of a man from the people. K. Marlo: the problem of titanism.

In the XVI century. English literature, which entered the Renaissance, reached an all-round development. Along with Renaissance poetry, the novel was established on English soil, and at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. Renaissance drama flourished.

This rapid rise of English literature, which began at the end of the sixteenth and captured a number of decades, gradually prepared throughout the century.

Bishops don’t care, What a neighbor lives from hand to mouth, That Jill sheds his sweat, That Jack oppresses his back over the arable land ... (Translated by O. B. Rumer)

As a poet, Skelton is still closely associated with the traditions of the late Middle Ages. It draws on Chaucer and folk songs. Following Chaucer, he willingly uses doggerels - short unequal lines, as well as areal words and turns. Folk humor culture maintains the lubok brightness of his works ("Eleanor Rumming's Beer"). This is the same restless spirit that, a few decades later, will make itself known in Shakespeare's Sir Toby and Falstaff.

Subsequently, the development of English Renaissance poetry took a different path. Striving for a more perfect, "high" style, English humanist poets depart from the "vulgar" traditions of the late Middle Ages and turn to Petrarch and ancient authors. It's time for English book lyrics. As we have seen, the French poetry of the 16th century developed in the same approximate way.

The first poets of the new direction were the young aristocrats Thomas Wyeth (1503-1543) and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, in the former Russian transcription of Surrey (1517-1547). Both of them shone at the court of Henry VIII, and both experienced the brunt of royal despotism. Wyatt spent some time in prison, and Sarri not only ended up in prison three times, but ended, like Thomas More, his life on the chopping block. For the first time their works were published in a collection published in 1557. Contemporaries highly appreciated their desire to reform English poetry, to raise it to the height of new aesthetic requirements. One of these contemporaries - Puttingham wrote in his book "The Art of English Poetry": "In the second half of the reign of Henry VIII, a new community of court poets appeared, whose leaders were Sir Thomas Wyeth and Earl Henry Surry. Traveling through Italy, they knew there the high sweetness of the meter and the style of Italian poetry ... They subjected our coarse and unprocessed poetry to a thorough finish and did away with the state in which it was before. Therefore, they can rightfully be called the first reformers of our metrics and our style "[Cit. In: History of English Literature. M.; L., 1943. T. I, issue. 1. S. 303.] .

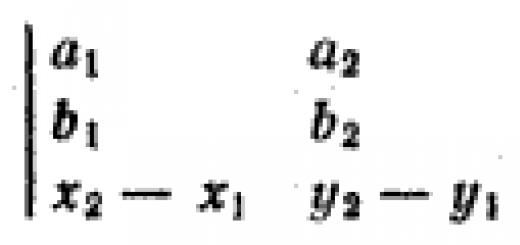

Wyeth was the first to introduce the sonnet into English poetry, and Sarri gave the sonnet the form that we later find in Shakespeare (three quatrains and a final couplet with a rhyming system: avav edcd efef gg). The leading theme of both poets was love. She fills Wyeth's sonnets, as well as his lyrical songs ("Lute of the mistress", etc.). Closely following Petrarch (for example, in the sonnet "There is no peace for me, even though the war is over"), he sang about love that turned into sorrow (the song "Will You Leave Me?", etc.). Having experienced a lot, having lost faith in many things, Wyeth began to write religious psalms, epigrams and satires directed against the vanity of court life ("Life at Court"), the pursuit of nobility and wealth ("On Poverty and Wealth"). In prison, he wrote an epigram in which we find the following mournful lines:

I feed on sighs, shed tears, The shackle ringing serves me as music ... (Translated by V.V. Rogov)

Melancholy tones are also heard in Sarri's lyrics. And he was a student of Petrarch, and at the same time a very gifted student. He dedicated one of the sonnets to a young aristocrat, acting under the name of Giraldina. The English Petrarchist endows his mistress with an unearthly charm. With the words: "She is like an angel in paradise; Blessed is the one to whom she gives her love," he ends his sonnet. As for the melancholic resignations that arise in Sarri's poetry, there were quite enough reasons for them. A brave warrior, a brilliant aristocrat, he more than once becomes a victim of court intrigues. The dungeon became his second home. In one of the poems written in captivity, the poet mourns for his lost freedom and recalls the past joyful days ("Elegy on the Death of Richmond", 1546). Sarri owns a translation of two songs of Virgil's Aeneid, made in blank verse (iambic pentameter unrhymed), which was to play such a big role in the history of English literature.

Wyatt and Sarri laid the foundations of English humanistic lyrics, which testified to the increased interest in man and his inner world. By the end of the XVI and beginning of the XVII century. refers to the flowering of English Renaissance poetry - and not only lyrical, but also epic. Following the example of the poets of the Pleiades, the English zealots of poetry created a circle solemnly named the Areopagus.

One of the most talented participants in the "Areopagus" was Philip Sidney (1554-1586), a man of versatile interests and talents, who raised English humanistic poetry to a high degree of perfection. He came from a noble family, traveled a lot, performing diplomatic missions, was favored by Queen Elizabeth, but incurred her disfavor by daring to condemn the cruel treatment of Irish peasants by English landlords. At a flourishing age, he ended his days on the battlefield.

The true manifesto of the new school was Sidney's treatise "The Defense of Poetry" (c. 1584, published in 1595), which in many respects has something in common with the treatise (Du Bellay's "Defence and glorification of the French language." Only if Du Bellay's opponents were learned pedants who preferred Latin French, then Sidney considered it his duty to defend poetry (literature), which was attacked by pious Puritans. Thus, Sidney's apology for poetry meant an apology for the Renaissance in the field of art and culture. Following the ancient Hellenes, Sidney calls to believe that " poets are the favorites of the gods", that "the highest deity, through Hesiod and Homer, deigned to send us all kinds of knowledge under the cover of fables: rhetoric, natural and moral philosophy, and infinitely more." Together with Scaliger, the author of the famous "Poetics" in the Renaissance (1561), Sidney claims that "no philosophical doctrine will instruct you how to become an honest man, better and faster than reading Virgil". In short, poetry is a sure school of wisdom and virtue.

Sidney speaks with special enthusiasm about "heroic poetry", since the "heroic poet", glorifying valor, "generosity and justice", penetrates with the rays of poetry "the fogs of cowardice and the darkness of lust."

At every opportunity, Sidney turns to the authority and artistic experience of ancient poets. So, if you need to name the name of a literary hero who is able to "revive" and "educate" the human spirit, he does not hesitate to name Aeneas, recalling "how he behaved during the death of his fatherland, how he saved his aged father and objects of worship, how he obeyed the immortals, leaving Dido", etc. However, bowing to ancient literature and ardently urging to draw from this source, Sidney did not at all want English poetry to lose its natural originality. He recalled with gratitude the poetic experiences of Wyeth and Surry, highly appreciated the poetic genius of Chaucer, and even admitted ("I confess my own barbarity") that he had never listened to the old folk ballad about Percy and Douglas without "so that my heart would not leap like a trumpet, and yet it is sung only by some blind commoner, whose voice is as rough as the style is unfinished. However, the humanist scientist immediately notes that the named song would have made a much greater impression, "being embellished with the magnificent ornateness of Pindar." On this basis, Sidney is critical of the English folk drama of the pre-Shakespearean period, arguing that the drama should be subject to strict Aristotelian rules. As you know, the English Renaissance drama in its heyday did not follow the path outlined by Sidney.

As for Sidney herself, her best examples are far from lush Pindaric ornate. Like Ronsard, Sidney gravitates towards a clear, complete poetic drawing. He achieves high artistic perfection in the development of the sonnet form. His love sonnets (the cycle "Astrophilus and Stella", 1580-1584, published in 1591) were a well-deserved success (Astrophilus means in love with the stars, Stella is a star). It was thanks to Sidney that the sonnet became a favorite form in the English Renaissance lyrics. In Sidney's poems, ancient myths are resurrected ("Philomela", "Phoebus judged Cupid, Zeus, Mars"). Sometimes Sidney echoes Petrarch and the poets of the Pleiades, and sometimes with a decisive gesture throws away the entire book load. So, in the 1st sonnet of the cycle “I imagined pouring out the ardor of sincere love in verse,” he reports that in other people's creations he was looking in vain for words that could touch the beauty. "Fool," was the voice of the Muses, "look into your heart and write."

Peru Sidney also owns the unfinished pastoral novel "Arcadia", published in 1590. Like other works of this kind, it is written in a very conventional manner. Storm on the sea, love stories, disguises and other adventures of this kind, it is written in a very conventional manner. A storm at sea, love stories, disguises and other adventures, and, finally, a happy ending make up the content of the novel, which takes place in the legendary Arcadia. The prose text is interspersed with many poems, sometimes very exquisite, written in a wide variety of sizes and forms of ancient and Italian origin (sapphic stanzas, hexameters, tercines, sextines, octaves, etc.).

Another outstanding poet of the late XVI century. was Edmund Spenser (1552-1599), who took an active part in the creation of the Areopagus. The son of a cloth merchant, he spent about twenty years in Ireland as one of the representatives of the English colonial administration. He excellently wrote musical sonnets ("Amoretti", 1591-1595), marriage hymns, including "Epithalam", dedicated to his own marriage, as well as Platonic "Hymns in honor of love and beauty" (1596). Great success fell to the share of his "Shepherd's Calendar" (1579), dedicated to Philip Sidney. Adhering to the tradition of European pastoral poetry, the poem consists of 12 poetic eclogues according to the number of months in a year. The eclogues deal with love, faith, morality and other issues that attracted the attention of humanists. The May eclogue is very good, in which the aged shepherd Palinodius, joyfully welcoming the arrival of spring, vividly describes the national holiday dedicated to merry May. The conventional literary element recedes here before the expressive sketch of English folk customs and mores.

But the most significant creation of Spencer is the monumental chivalric poem "The Fairy Queen", which was created over many years (1589-1596) and earned the author the loud fame of the "Prince of Poets". Through the efforts of Spencer, England finally found a Renaissance epic. In the Poetics of the Renaissance, including Sidney's A Defense of Poetry, heroic poetry has always been given pride of place. Especially high was Sidney's "Aeneid" by Virgil, which was for him the standard of the epic genre. Being Sidney's colleague in the classic Areopagus, Spencer chose a different path for himself. And although among his eminent mentors, he, along with Ariosto and Tasso, names Homer and Virgil, the classical element itself is not decisive in his poem. However, the "Queen of the Fairies" is only partly in contact with the Italian poems. Its essential feature can be considered that it is closely connected with English national traditions.

The poem makes extensive use of elements of the courtly novels of the Arthurian cycle with their fabulous fantasy and decorative exoticism. After all, the legends about King Arthur arose on British soil, and King Arthur himself continued to be a "local hero" for the English reader, the personification of British glory. Moreover, it was in England in the 16th century. Sir Thomas Malory, in the vast epic "The Death of Arthur," summed up the tales of the Arthurian cycle in a majestic manner.

But Spencer relied not only on the tradition of T. Mallory. He combined it with the tradition of W. Langland and created a knightly allegorical poem, which was supposed to glorify the greatness of England, illuminated by the radiance of virtues.

In the poem, King Arthur (a symbol of greatness), having fallen in love in a dream with the "faerie queen" Gloriana (a symbol of glory, contemporaries saw Queen Elizabeth I in her), is looking for her in a fairy-tale land. In the form of 12 knights - companions of King Arthur, Spencer was going to bring out 12 virtues. The poem was supposed to consist of 12 books, but the poet managed to write only 6. In them, knights perform feats, personifying Piety, Temperance, Chastity, Justice, Courtesy and Friendship.

The nature of the poem is given at least by the first book, dedicated to the deeds of the knight of the Red Cross (Piety), whom the queen sends to help the beautiful Una (Truth) to free her parents, imprisoned in a copper castle. After a fierce battle, the knight defeats the monster. Together with his lady, he stops for the night in a hermitage. The latter, however, turns out to be the insidious magician Archimago, who sends false dreams to the knight, convincing him of Una's betrayal. In the morning, the knight leaves the maiden, who immediately goes in search of the fugitive. On the way, the knight of the Red Cross accomplishes a number of new feats. Una, meanwhile, humbles with her beauty the formidable lion, who from now on does not leave the beautiful maiden. And here before her, finally, is the knight of the Red Cross, whom she so selflessly seeks. But the joy is premature. In fact, before her is the magician Archimago, who treacherously took on the image of a knight dear to her. After a series of dramatic ups and downs, Una learns that a Red Cross knight has been defeated and captured by a certain giant with the help of the sorceress Duessa. She turns to King Arthur for help, who is just passing by in search of the fairy queen. In a fierce battle, King Arthur kills the giant, drives away the sorceress Duessa and unites the lovers. Safely passing the Cave of Despair, they arrive at the Temple of Holiness. Here the knight of the Red Cross fights the dragon for three days, defeats him, marries Una, and then, happy and joyful, goes to the court of the fairy queen to tell her about his adventures.

Even from a summary of the first book alone, it is clear that Spenser's poem is woven from many colorful episodes that give it great elegance. The sparkle of knightly swords, the intrigues of evil wizards, the gloomy depths of Tartarus, the beauties of nature, love and fidelity, deceit and malice, fairies and dragons, gloomy caves and bright temples - all this forms a wide multi-colored picture that can captivate the imagination of the most demanding reader. This flickering of episodes, flexible storylines, predilection for lush scenery and romantic props, of course, evoke Ariosto's poem. Only, narrating about knightly exploits, Ariosto did not hide an ironic smile, he created a magnificent world, over which he himself laughed. Spencer is always serious. In this he is closer to Tasso and Malory. He creates his world not in order to amuse the reader, but in order to spiritualize him, to accustom him to the highest moral ideals. Therefore, he ascends Parnassus, as if in front of him was a pulpit.

Of course, he is well aware that the era of chivalry has long passed. Spencer's knights exist as well-defined allegorical figures denoting either good or evil. The poet seeks to glorify the strength and beauty of virtue, and the victorious knights depicted by him are only separate facets of the moral nature of a person, about whom Renaissance humanists wrote more than once. Thus, Spenser's poem answers the question of what a perfect person should be, capable of triumphing over the kingdom of evil and vice. This is a kind of magnificent knightly tournament, ending with the triumph of virtue. But the poem contained not only a moral tendency. Contemporaries, not without reason, caught in it also a political trend. They identified the queen of the fairies with Queen Elizabeth I, and the insidious sorceress Duessa with Mary Stuart. Under allegorical veils they found allusions to England's victorious war against feudal-serf Spain. In this respect, Spenser's poem was the apotheosis of the English kingdom.

The poem is written in a complex "Spencer stanza", repeating Chaucer's stanza in the first part, to which, however, the eighth and ninth lines are added (rhyming according to the scheme: avaavvssss). The iambic pentameter in the final line gives way to the iambic pentameter (i.e. the Alexandrian verse). At the beginning of the XIX century. English romantics showed a very great interest in the creative heritage of Spencer. Byron wrote "Child Harold's Pilgrimage" in Spencer's stanza, and Shelley's "The Rise of Islam".

In the XVI century. there was also the formation of the English Renaissance novel, which, however, was not destined to reach the heights that the French (Rabelais) and Spanish (Cervantes) novels reached at that time. Only in the XVIII century. The victorious march of the English novel across Europe began. Nevertheless, it was in England during the Renaissance that the utopian novel arose, with all the characteristic features inherent in this genre. Contemporaries warmly accepted F. Cindy's pastoral novel Arcadia. Noisy, although not lasting success fell to the lot of John Lily's educational novel "Euphues, or the Anatomy of Wit" (1578-1580), written in a pretentious, refined style, called "eufuism". The content of the novel is the story of a young noble Athenian, Eufues, traveling in Italy and England. Human weaknesses and vices are opposed in the novel by examples of high virtue and spiritual nobility. In "Euphues" there is little action, but much attention is paid to the experiences of the characters, their heartfelt outpourings, speeches, correspondence, stories of various characters in which Lily shows all his precision virtuosity. He is always looking for and finds new reasons for lengthy discussions concerning the feelings and actions of people. This analytical approach to the spiritual world of a person, the author’s desire to “anatomize” his actions and thoughts, is, in essence, the most remarkable and new trait of "Euphues", which had a noticeable influence on English literature at the end of the 16th century. my "euphism" with its English metaphors and antitheses was probably not only a manifestation of salon affectation, but also an attempt to find a new, more complex form to reflect the world, ceasing to be elementary and internally whole [See: Urnov D.M. Formation of the English novel of the Renaissance // Literature of the Renaissance and problems of world literature. M., 1967. S. 416 et seq.] .

Close to the Spanish picaresque novel is Thomas Nash's novel "The Unfortunate Wanderer, or the Life of Jack Wilton" (1594), which tells about the adventures of a young roguish Englishman in various European countries. The author rejects the "aristocratic" sophistication of euphuism, and pastoral court masquerades are completely alien to him. He wants to speak the truth about life without stopping at portraying its dark, even repulsive sides. And although in the end the hero of the novel embarks on the path of virtue, marries and finds the desired peace, Nash's work remains a book in which the world appears without any embellishment and illusions. Only outstanding figures of the Renaissance culture, sometimes appearing on the pages of the novel, are able to illuminate this world with the light of human genius. Relating the action of the novel to the first third of the 16th century, T. Nash gets the opportunity to compose a beautiful legend about the love of the English poet Count Sarri for the beautiful Geraldine, as well as draw portraits of Erasmus of Rotterdam, Thomas More, the Italian poet and publicist Pietro Aretino and the German "prolific scientist" Cornelius Agrippa of Nettesheim, reputed to be a powerful "warlock". Far away from the refined novels of Sidney and Lily were also the household or "production" (as they are sometimes called) novels by Thomas Deloney ("Jack of Newbury", 1594, etc.).

From this short list it is clear that at the end of the XVI century. in a relatively short period of time a number of very different novels appeared in England, testifying to the fact that the mighty creative ferment that had engulfed the country had penetrated into all spheres of literature, everywhere outlining new paths.

But, of course, the English literature of the sixteenth century achieved the most astonishing successes. in the field of drama. Remembering the English Renaissance, we certainly first of all remember Shakespeare. And Shakespeare was by no means alone. He was surrounded by a galaxy of talented playwrights who enriched the English theater with a number of wonderful plays. And although the heyday of the English Renaissance drama did not last very long, it was unusually stormy and multicolored.

This heyday, which began in the eighties of the 16th century, was being prepared for many decades. However, the Renaissance drama itself did not immediately establish itself on the English stage. For a very long time, the folk theater, which had developed in the middle of the century, continued to play an active role in the country. Addressed to the mass audience, he often in traditional forms responded vividly to the questions put forward by the era. This supported his popularity, made him an important element of public life. But not all traditional forms have stood the test of time. Relatively quickly, the mystery, rejected by the Reformation, died out. But the interlude continued to loudly declare itself - the most mundane and cheerful genre of medieval theater and morality - an allegorical play that raised certain important questions of human existence.

Along with traditional characters, characters began to appear in morality, who were supposed to assert new advanced ideas. These are such allegorical figures as Mind and Science, triumphing over Scholasticism. In a play dating back to 1519, the Thirst for Knowledge, despite all the efforts of Ignorance and Lust, helps a person to listen attentively to the wise instructions of Lady Nature. The play insistently cites the idea that the earthly visible world is worthy of the closest study. By the middle of the XVI century. include morality, written in defense of church reform. In one of them ("Entertaining satire about the three estates" by the Scottish poet David Lindsay, 1540), not only the numerous vices of the Catholic clergy are denounced, but the issue of social injustice is also raised. The Poor Man (Pauper) who appears on the stage acquaints the audience with his bitter fate. He was a hardworking peasant, but the greedy squire (landlord) and the no less greedy vicar (priest) turned him into a beggar, and a rogue pardoner took over his last pennies. What can the Poor hope for when all three classes (clergy, nobility and townspeople) allow Deception, Lies, Flattery and Bribery to rule the state? And only when honest little John, personifying the healthy forces of the nation, vigorously intervenes in the course of events, the situation in the kingdom changes for the better. It is clear that the highest circles disapprovingly looked at plays containing seditious thoughts, and Queen Elizabeth in 1559 simply forbade the production of such morality plays.

With all the obvious conventionality of the allegorical genre in English morality of the 16th century. vivid everyday scenes appeared, and even allegorical characters lost their abstractness. Such was, for example, the clownish figure of Vice (Vice). Among his ancestors we find Obedala from the allegorical poem by W. Langland, and among the descendants - the fat sinner Falstaff, vividly depicted by Shakespeare.

But, of course, colorful genre scenes should first of all be sought in interludes (interludes), which are an English variety of French farce. Such are the interludes of John Gaywood (c. 1495-1580) - cheerful, spontaneous, sometimes rude, with characters directly snatched from everyday life. Without taking the side of the Reformation, Gaywood at the same time clearly saw the shortcomings of the Catholic clergy. In the interlude "The Pardoner and the Monk" he makes the greedy ministers of the church start a brawl in the temple, as each of them wants to pull as many coins out of the pocket of the believers. In "A funny action about her husband Joan Joan, his wife Tib and the priest Sir Jane" (1533), a dim-witted husband is deftly led by the nose by a porous wife, along with her lover, a local priest. Along with morality, interludes played a prominent role in the preparation of English Renaissance drama. They preserved for her the skills of the folk theater and that keen sense of life, which later determined the greatest achievements of English drama.

At the same time, both morality and interludes were in many ways old-fashioned and rather elementary. English Renaissance drama needed both a more perfect form and a deeper understanding of man. To her aid, as in other countries in the Renaissance, came ancient drama. As early as the beginning of the 16th century. on the school stage, the comedies of Plautus and Terence were played in Latin. From the middle of the XVI century. ancient playwrights began to be translated into English. Playwrights began to imitate them, using the experience of the Italian "learned" comedy, which in turn ascended to classical models. However, the classical element did not deprive English comedy of its national identity.

Seneca had a significant influence on the formation of English tragedy. He was willingly translated, and in 1581 a complete translation of his tragedies appeared. The traditions of the Seneca are clearly felt in the first English "bloody" tragedy "Gorboduk" (1561), written by Thomas Norton and Thomas Sequil and which was a great success. The plot is borrowed from the medieval chronicle of Geoffrey of Monmouth. Like Shakespeare's Lear, Gorboduk divides his state between his two sons during his lifetime. But, in an effort to seize all power, the younger son kills the older one. To avenge the death of her firstborn, the Queen Mother stabs the fratricide. The country is engulfed in the flames of civil war. The king and queen are killed. The blood of commoners and lords is shed. The play contains certain political tendencies - it stands up for the state unity of the country, which should serve as a guarantee of its prosperity. This is directly indicated by the pantomime that precedes the first act. The six savages try in vain to break the bundle of rods, but, pulling out one rod after another, they break them without difficulty. On this occasion, the play says: "It meant that the united state opposes any force, but that, being fragmented, it can easily be defeated ..." It is no coincidence that Queen Elizabeth watched the play with interest. The classical canon in "Gorboduk" corresponds to the messengers telling about the dramatic events that take place behind the scenes, and the chorus that appears at the end of the act. The play was written in blank verse.

Gorboduk was followed by a long series of tragedies, testifying to the fact that this genre found fertile ground in England. The spirit of Seneca continued to hover over them, but the playwrights willingly went beyond the boundaries of the classical canon, combining, for example, the tragic with the comic or breaking the cherished unity. Turning to the Italian short story, ancient legends, as well as various English sources, they asserted on the stage a large world of human passions. Although this world was still devoid of real depth, it already brought the audience closer to the time when somehow the wonderful flowering of the English Renaissance theater began all at once.

This heyday began in the late eighties of the XVI century. from the performance of talented humanist playwrights, usually called "university minds". All of them were educated people who graduated from Oxford or Cambridge University. In their work, classical traditions merged widely with the achievements of the folk theater, forming a mighty stream of national English drama, which soon reached unprecedented power in the works of Shakespeare.

Of great importance was the victory that England won over Spain in 1588, which not only strengthened the national consciousness of wide circles of English society, but also sharpened interest in a number of important issues of state development. The question of the enormous possibilities of man, which has always attracted the attention of humanists, also acquired a new acuteness. At the same time, the concreteness and depth of artistic thinking increased, which led to the remarkable victories of Renaissance realism. And if we take into account that from the end of the XVI century. the social life of England became more and more dynamic, - after all, the time was not far off when a bourgeois revolution broke out in the country - that atmosphere of intense, and sometimes contradictory creative quest, which is so characteristic of the "Elizabethian drama", which forms the highest peak in history, will be understandable English Renaissance Literature.

"University minds", united by the principles of Renaissance humanism, at the same time did not represent any single artistic direction. They are different in many ways. So, John Lily, the author of the precise novel "Euphues", wrote elegant comedies on ancient themes, referring mainly to the court spectator. And Thomas Kyd (1558-1594), sharper, and even rude, continued to develop the genre of "bloody tragedy" ("Spanish Tragedy", ca. 1589).

Robert Greene and especially Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare's most significant predecessors, deserve a closer look. Robert Greene (1558-1592) was awarded the high degree of Master of Arts from the University of Cambridge. However, he was attracted to the life of bohemia. He traveled to Italy and Spain. He quickly gained popularity as a writer. But success did not turn his head. Shortly before his death, Green began to write a penitential essay, in which he condemned his sinful life and warned readers against a false and dangerous path. Green's creative heritage is diverse. He owns numerous love stories, novels on historical themes (one of them - "Pandosto", 1588 - used by Shakespeare in "The Winter's Tale"), pamphlets, etc.

Green entered the history of English literature primarily as a gifted playwright. His play Monk Bacon and Monk Bongay (1589) enjoyed great success. When working on it, Green relied on the English folk book about the warlock Bacon, which was published at the end of the 16th century. Like the German Faust, the monk Bacon is a historical figure. The prototype of the hero of the folk legend was Roger Bacon, an outstanding English philosopher and naturalist of the 13th century, who was persecuted by the church, which saw him as a dangerous freethinker. The legend turned the monk Bacon into a warlock and connected him with evil spirits. In Greene's play, Bacon is given a significant role. At a time when interest in magic and all kinds of "secret" sciences grew in Europe, Green brought onto the stage a colorful figure of an English warlock who owns a magic book and a magic mirror. In the end, Bacon repents of his sinful aspirations and becomes a hermit. But the leading theme of the play is still not magic, but love. The true heroine of the play is a beautiful and virtuous girl, the daughter of a forester Margarita. The Prince of Wales falls in love with her, but she gives her heart to the Prince's courtier, Earl of Lincoln. No trials and misadventures are able to break her stamina and fidelity. Struck by Marguerite's resilience, the Prince of Wales stops his harassment. The bonds of marriage unite lovers. Demonic intricacies are not needed where great human love reigns.

The Pleasant Comedy about George Greene, the Wakefield Field Watchman, which was published after Greene's death (1593) and probably belongs to him, is also closely connected with English folk tales. The hero of the play is no longer an arrogant warlock who renounces his sinful craft, but a valiant commoner, like Robin Hood, sung in folk songs. By the way, Robin Hood himself appears on the pages of the comedy. Hearing of George Green's prowess, he seeks to meet him. The play recreates a situation in which the English state is threatened by both internal and external danger, for a group of English feudal lords, led by the Earl of Kendal and in alliance with the Scottish king, raises an uprising against the English king Edward III. However, the plans of the rebellious feudal lords are destroyed by field watchman George Green, who at first, on behalf of the townspeople of Wakefield, decisively refuses to help the rebels, and then cunningly captures Earl Kendal himself and his associates. Wishing to reward George Green, Edward III wants to raise him to a knighthood. But the field watchman declines this royal favour, stating that his only desire is to "live and die as a yeoman," i.e. free peasant. The playwright managed to create a very expressive image of a commoner: skillful, strong, honest, resourceful, courageous, devoted to his homeland and the king, who embodies for him the greatness and unity of the state. This hero is placed immeasurably higher than the arrogant and self-serving feudal lords. To this it should be added that in comedy there are colorful sketches of folk customs and mores, and that much of it has grown directly from folklore. It is no accident that contemporaries saw Grin as a folk playwright. Joining this opinion, a prominent Russian scientist, an expert on the English theater of the Shakespeare era N.N. Storozhenko wrote: “Indeed, the title of a folk playwright does not suit anyone like Green, because we will not find so many scenes in any of his contemporary playwrights, so to speak, snatched alive from English life and, moreover, written in pure folk language, without any admixture of euphuism and classical ornamentation" [Storozhenko N. Robert Green, his life and works. M., 1878. S. 180.] .

A friend of R. Green at one time was the talented poet and playwright Christopher Marlo (1564-1593), the true creator of the English Renaissance tragedy. As the son of a shoemaker, he, through a happy coincidence, got to the University of Cambridge and, like Greene, was awarded the degree of Master of Arts. Marlo knew ancient languages well, carefully read the works of ancient authors, he was also familiar with the works of Italian writers of the Renaissance. After graduating from Cambridge University, this energetic son of a commoner could count on a profitable church career. However, Marlo did not want to become a minister of church orthodoxy. He was attracted by the multi-colored world of the theater, as well as freethinkers who dared to doubt walking religious and other truths. It is known that he was close to the circle of Sir Walter Raleigh, who fell into disgrace during the reign of Elizabeth and ended his life on the chopping block in 1618 under King James I. The Bible, in particular, denied the divinity of Christ and argued that the biblical legend about the creation of the world is not supported by scientific data, etc. It is possible that Marlo's accusations of "godlessness" were exaggerated, but he was still a skeptic in religious matters. In addition, not having the habit of hiding his thoughts, he sowed "disturbance" in the minds of the people around him. The authorities were alarmed. Clouds were gathering more and more over the poet's head. In 1593, in a tavern near London, Marlowe was killed by agents of the secret police.

The tragic fate of Marlo in some way echoes the tragic world that arises in his plays. At the end of the XVI century. it was clear that this great age was not at all idyllic.

Marlowe, being a contemporary of the dramatic events that took place in France, dedicated his late tragedy The Massacre of Paris (staged in 1593) to them.

The play could attract the attention of the audience with its acute topicality. But there are no big tragic characters in it, which make up the strong side of Marlo's work. The Duke of Guise, who plays an important role in it, is a rather flat figure. This is an ambitious villain, confident that all means are good to achieve the intended goal.

Much more complicated is the figure of Barrava in the tragedy The Jew of Malta (1589). Shakespeare's Shylock in The Merchant of Venice is undoubtedly closely related to this Marlo character. Like Giza, Barrava is a staunch Machiavellian. Only if Giza is supported by powerful forces (Queen Mother Catherine de Medici, Catholic Spain, papal Rome, influential associates), then the Maltese merchant and usurer Barrava is left to his own devices. Moreover, the Christian world in the face of the ruler of Malta and his close associates are hostile to him. In order to save his fellow believers from excessive Turkish extortions, the ruler of the island, without hesitation, ruins Barrava, who owns enormous wealth. Seized with hatred and malice, Barrabas takes up arms against a hostile world. He even puts his own daughter to death because she dared to renounce the faith of her ancestors. His dark plans become more and more grandiose, until he falls into his own trap. Barrabas is an inventive, active person. The pursuit of gold turns him into a topical, formidable, significant figure. And although the power of Barrabas is inseparable from villainy, there are some glimpses of titanism in it, indicating the enormous possibilities of man.

We find an even more grandiose image in Marlo's early two-part tragedy "Tamerlane the Great" (1587-1588). This time the hero of the play is a Scythian shepherd who became a powerful ruler of numerous Asian and African kingdoms. Cruel, inexorable, having shed "rivers of blood as deep as the Nile or the Euphrates," Tamerlane in the playwright's portrayal is not devoid of traits of undoubted greatness. The author endows him with an attractive appearance, he is smart, capable of great love, faithful in friendship. In his unbridled desire for power, Tamerlane, as it were, caught that spark of divine fire that burned in Jupiter, who overthrew his father Saturn from the throne. Tamerlane's tirade, glorifying the unlimited possibilities of man, seems to have been uttered by an apostle of Renaissance humanism. Only the hero of the tragedy Marlo is not a scientist, not a philosopher, but a conqueror, nicknamed "the scourge and the wrath of God." A simple shepherd, he rises to unprecedented heights, no one can resist his impudent impulse. It is not difficult to imagine what impression the common people who filled the theater were made by the scenes in which the victorious Tamerlane triumphed over his noble enemies, who mocked his low origin. Tamerlane is firmly convinced that not origin, but valor is the source of true nobility (I, 4, 4). Admired by the beauty and love of his wife Zenocrates, Tamerlane begins to think that only in beauty lies the guarantee of greatness, and that "true glory is only in goodness, and only it gives us nobility" (I, 5, 1). But when Zenocrate dies, in a fit of furious despair, he dooms the city in which he lost his beloved. Tamerlane rises higher and higher on the steps of power, until inexorable death stops his victorious march. But even parting with his life, he does not intend to lay down his arms. He imagines a new unprecedented campaign, the purpose of which should be the conquest of the sky. And he calls on his comrades-in-arms, raising the black banner of death, in a terrible battle to destroy the gods, who proudly ascended over the world of people (II, 5, 3).

Among the Titans depicted by Marlo is also the famous warlock Dr. Faust. The playwright dedicated his "Tragic History of Doctor Faust" (1588) to him, which had a significant influence on the subsequent development of the Faustian theme. In turn, Marlo relied on the German folk book about Faust, which was published in 1587 and soon translated into English.

If Barrabas personified greed that turned a person into a criminal, Tamerlane craved unlimited power, then Faust was drawn to great knowledge. Characteristically, Marlowe noticeably strengthened Faust's humanistic impulse, about which the pious author of a German book wrote with undisguised condemnation. Rejecting philosophy, law and medicine, as well as theology as the most insignificant and false science (act I, scene 1), Faust Marlowe places all his hopes on magic, which can raise him to a colossal height of knowledge and power. Passive book knowledge does not appeal to Faust. Like Tamerlane, he wants to rule the world around him. It seethes with energy. He confidently concludes an agreement with the underworld and even reproaches the demon Mephistopheles for cowardice, grieving for the lost paradise (I, 3). He already clearly sees his future deeds that can amaze the world. He dreams of surrounding his native Germany with a copper wall, changing the course of the Rhine, merging Spain and Africa into a single country, mastering fabulous riches with the help of spirits, subordinating the emperor and all German princes to his power. He already imagines how he crosses the ocean with his troops on an air bridge and becomes the greatest of sovereigns. Even Tamerlane could not come up with such bold thoughts. It is curious that Marlo, who was not so long ago a student, makes Faust, immersed in titanic fantasies, recall the meager life of schoolchildren and express his intention to end this poverty.

But Faust, with the help of magic, acquires magical powers. Does he carry out his intentions? Does he change the shape of the continents, does he become a powerful monarch? We don't learn anything from the play. One gets the impression that Faust has not even made an attempt to put his declarations into practice. From the words of the choir in the prologue of the fourth act, we only learn that Faust traveled a lot, visited the courts of monarchs, that everyone marvels at his learning, that "in all parts of him rumors rumble." And the rumor rumbles about Faust mainly because he always acts as a skilled magician, amazing people with his tricks and magical extravaganzas. This significantly reduces the heroic image of the daring mage. But in this Marlo followed the German book, which was his main, if not only, source. Marlo's merit is that he gave the Faustian theme a great life. The later dramatic adaptations of the legend in one way or another go back to his "Tragic History". But Marlo is not yet trying to decisively modify the German legend, which has taken the form of a "folk book". Such attempts will only be made by Lessing and Goethe under completely different historical conditions. Marlo cherishes his source, extracting both pathetic and farcical motifs from it. It is clear that the tragic finale, depicting the death of Faust, who became the prey of hellish forces, should have been included in the play. Without this ending, the legend of Faust was not conceivable at that time. The downfall of Faust into hell was as much a necessary element of the legend as the downfall of Don Juan into hell in the well-known Don Juan legend. But Marlowe turned to the legend of Faust not because he wanted to condemn the atheist, but because he wanted to portray a bold freethinker who could encroach on unshakable spiritual foundations. And although his Faust sometimes rises to great heights, but falls low, turning into a fairground magician, he never merges with the gray crowd of philistines. In any of his magical kunshtuk there is a grain of titanic daring, elevated above the wingless crowd. True, the wings acquired by Faust turned out to be, according to the prologue, wax, but they were still the wings of Daedalus, striving for an immense height.

Wishing to enhance the psychological drama of the play, as well as increase its ethical scope, Marlo turns to the techniques of medieval morality. Good and evil angels are fighting for the soul of Faust, who is faced with the need to finally choose the right path in life. The pious elder urges him to repent. Lucifer arranges for him an allegorical parade of the seven deadly sins "in their true form." Sometimes Faust is overcome by doubts. Either he considers the afterlife torments to be an absurd invention and even equates the Christian underworld to the ancient Elysium, hoping to meet all the ancient sages there (I, 3), then the impending punishment deprives him of peace of mind, and he plunges into despair (V, 2). But even in a fit of despair, Faust remains a titan, the hero of a mighty legend that struck the imagination of many generations. This did not prevent Marlowe, in accordance with the widespread custom of Elizabethan drama, from introducing into the play a number of comic episodes in which the theme of magic is depicted in a reduced plan. In one of them, Wagner, a faithful disciple of Faust, frightens a vagabond jester with devils (I, 4). In another episode, Robin, the groom of the inn, who stole a magic book from Dr. Faust, tries to play the role of an evil spirits caster, but gets into a mess (III, 2).

Blank verse is interspersed with prose in the play. Comic prosaic scenes gravitate towards areal scoffing. On the other hand, white verse, which replaced the rhymed verse that dominated the stage of the folk theater, under the pen of Marlo achieved remarkable flexibility and sonority. After Tamerlane the Great, English playwrights began to use it widely, including Shakespeare. The scale of Marlowe's plays, their titanic pathos corresponds to an upbeat majestic style, replete with hyperbole, pompous metaphors, mythological comparisons. In "Tamerlane the Great" this style manifested itself with particular force.

Mention should also be made of Marlo's play "Edward II" (1591 or 1592), close to the genre of historical chronicle, which attracted Shakespeare's close attention in the 1990s.

Shakespeare's work is the pinnacle of the English Renaissance and the highest synthesis of the traditions of common European culture

INTRODUCTION

a) classical sonnet;

b) Shakespeare's sonnet.

CONCLUSION

“The soul of our century, the miracle of our stage, he belongs not to one century, but to all times,” wrote his younger contemporary, the English playwright Ben Jonson, about Shakespeare. Shakespeare is called the greatest humanist of the Late Renaissance, one of the greatest writers in the world, the pride of all mankind.

Representatives of many literary schools and movements at different times turned to his work in search of relevant moral and aesthetic solutions. The infinite variety of forms born under such a powerful influence is somehow progressive, whether they are quotations in John Gay's satirical "Opera Beggars" or passionate lines in the political tragedies of Vittorio Alfieri, the image of "healthy art" in the tragedy of Johann Goethe's "Faust" or democratic ideas expressed in the article-manifesto by Francois Guizot, the heightened interest in the internal state of the individual among English romantics, or the "free and broad portrayal of characters" in Alexander Pushkin's "Boris Godunov"...

This, perhaps, can explain the phenomenon of "immortality" of Shakespeare's creative heritage - an undeniably great poetic gift that refracts the most acute moral conflicts hidden in the very nature of human relations, is perceived and rethought by each subsequent era in a new aspect characteristic only of this moment, while remaining a product (so to speak) of its era, which absorbed all the experience of previous generations and realized their accumulated creative potential.

To prove that Shakespeare's work is the pinnacle of the English Renaissance and the highest synthesis of the traditions of the pan-European Renaissance culture (without claiming the laurels of George Brandes, who presented this topic extensively and significantly in his work "William Shakespeare" (1896)) I, perhaps , I will take the example of his USonetovF, as a genre that was born on the eve of the era in question and precisely during the Renaissance, and later XVII century, experiencing the time of the highest prosperity.

BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE RENAISSANCE

Renaissance (Renaissance), a period in the cultural and ideological development of the countries of Western and Central Europe (in Italy XIV - XVI centuries, in other countries the end of the XV - beginning of the XVII centuries), a transitional period from medieval culture to the culture of modern times.

Distinctive features of the culture of the Renaissance: anti-feudalism at its core, secular, anti-cleric character, humanistic worldview, appeal to the cultural heritage of antiquity, as if "revival" of it (hence the name).

The revival arose and most clearly manifested itself in Italy, where already at the turn of the XIII - XIV centuries. its harbingers were the poet Dante, the artist Giotto and others. The work of the Renaissance figures is imbued with faith in the unlimited possibilities of man, his will and mind, the rejection of Catholic scholasticism and asceticism (humanistic ethics). The pathos of affirming the ideal of a harmonious, liberated creative personality, the beauty and harmony of reality, the appeal to man as the highest principle of being, the feeling of wholeness and harmonious laws of the universe give the art of the Renaissance great ideological significance, a majestic heroic scale.

In architecture, secular structures began to play a leading role - public buildings, palaces, city houses. Using arched galleries, colonnades, vaults, baths, architects (Alberti, Palladio in Italy; Lescaut, Delorme in France, etc.) gave their buildings majestic clarity, harmony and proportionality to man.

Artists (Donatello, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian and others in Italy; Jan van Eyck, Brueghel in the Netherlands; Dürer, Niethardt in Germany; Fouquet, Goujon, Clouet in France) consistently mastered the reflection of all the richness of reality - the transmission volume, space, light, the image of a human figure (including a naked one) and the real environment - an interior, a landscape.

Renaissance literature created such monuments of enduring value as "Gargantua and Pantagruel" (1533 - 1552) by Rabelais, Shakespeare's dramas, the novel "Don Quixote" (1605 - 1615) by Cervantes, etc., organically combining interest in antiquity with an appeal to folk culture, the pathos of the comic with the tragedy of being. Petrarch's sonnets, Boccaccio's short stories, Aristo's heroic poem, philosophical grotesque (Erasmus of Rotterdam's treatise "Praise of Stupidity", 1511), Montaigne's essays - in different genres, individual forms and national variants embodied the ideas of the Renaissance.

In music imbued with a humanistic worldview, vocal and instrumental polyphony develops, new genres of secular music appear - solo song, cantata, oratorio and opera, contributing to the establishment of homophony.