Pyotr Klodt was born in 1805 in St. Petersburg into a military family descended from an old German family. His father was a general, a hero of the Patriotic War of 1812. Despite the fact that the future sculptor was born in the capital, he spent his youth in Omsk, away from European education and culture. He wanted to connect his life, like his ancestors, with a military career - in Omsk he was a cadet of a Cossack school, and upon returning to St. Petersburg he entered an artillery school. Despite this choice, during the years of his studies, at every opportunity, he took up a pencil or a penknife - he carved figures of horses and people - a hobby with which his father "infected".

After graduation, Klodt was promoted to ensign, served in an artillery brigade, but left the service in 1828 to focus solely on art. For two years he studied on his own, after which he became a volunteer at the Academy of Arts: the rector of the Academy, Martos, and teachers, seeing talent and skill in Klodt, helped him succeed. Over time, he became a true master of his craft and was known not only at the imperial court, but also far beyond its borders. The most famous creation of Klodt is, of course, sculptures horse tamers on the Anichkov bridge in St. Petersburg, but his other works are no less magnificent. "Evening Moscow" invites you to remember the most famous of them.

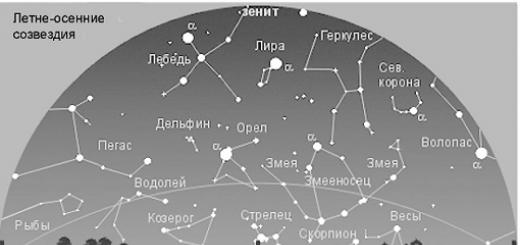

Horses of the Narva triumphal gates

Klodt carried out this large government order together with such experienced sculptors as S. Pimenov and V. Demut-Malinovsky. On the attic of the arch there is a six horses carrying the chariot of the goddess of glory, made of forged copper according to the model of Klodt in 1833. Unlike the classic images of this plot, the horses performed by Klodt are rapidly rushing forward and even rearing up. At the same time, the entire sculptural composition gives the impression of rapid movement. After completing this work, the author received worldwide fame and the patronage of Nicholas I. There is a legend that Nicholas I said: "Well, Klodt, you make horses better than a stallion."

The most famous creation of Klodt is, of course, the sculptural group of horse tamers on the Anichkov Bridge in St. Petersburg, but other works of the master are no less magnificent.

"Horse Tamers" Anichkov Bridge

The famous "Horse Tamers" at first had to be located not at all where they can be seen today. The sculptures were supposed to decorate the piers of Admiralteisky Boulevard, at the entrance to Palace Square. It is noteworthy that both the place and the project itself were personally approved by Nicholas I. When everything was ready for casting, Klodt decided that it was not worth taming horses near water and ships. He began to look for a place and rather quickly his choice fell on the Anichkov Bridge, which already needed reconstruction and was rather plain. The sculptor hinted at his idea, and the emperor supported him. Nikolai provided the sculptor with two purebred Arabian stallions - he was allowed to do whatever he wanted with them. Klodt was very useful for his experience gained during his studies at the Academy - at that time he was a student of one of the outstanding Russian foundry workers Ekimov, and by the time the "Tamers" was created, he had already managed to lead the entire Foundry Yard. Seeing the first bronze blanks, the emperor told the sculptor that they came out even better than the stallions actually looked.

On November 20, 1841, the solemn opening of the Anichkov Bridge after reconstruction took place, to which Petersburgers went literally in droves. But then the residents did not see the true beauty of Klodt's work - Nicholas I decided to donate two sculptures to the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm, and painted plaster copies were installed instead. Three years later, copies were made again, but they also did not last long - this time the "King of the Two Sicilies" Ferdinand II became their happy owner. Only in 1850 did the plaster copies finally disappear from the bridge, and bronze figures took their place.

Anichkov Bridge in the 1850s

Monument to Ivan Krylov

The life of the famous fabulist is almost inextricably linked with St. Petersburg - he lived in the city for almost sixty years, rarely leaving it. His death in 1844 became a national tragedy, and a year later a voluntary subscription was announced, the purpose of which was to raise money for a monument to the famous poet. In 1849, Klodt's project won an open competition. The initial sketches assumed the creation of an almost antique image of the poet, but the sculptor took a bold step - he abandoned the ideas of embodying idealistic images that prevailed at that time, and wanted to depict the poet as accurately as possible, in a natural setting. According to contemporaries, he managed to achieve an almost portrait resemblance to the original. Along the perimeter of the pedestal, the sculptor placed animals - the heroes of Krylov's fables. The monument to this day adorns the Summer Garden of St. Petersburg.

Monument to Nicholas I on St. Isaac's Square

Monument to Prince Vladimir of Kyiv

In 1833 the sculptor V. Demut-Malinovsky worked on a project of a monument to Prince Vladimir of Kyiv - the initiator of the baptism of Russia in 988. The work ended with the presentation in 1835 of the project to the president of the Imperial Academy of Arts. For unknown reasons, work on the project was suspended for a decade. In 1846, Demut-Malinovsky died, after which the architect K. Ton took over the work, who designed the pedestal in the form of a high tower-like church in the pseudo-Byzantine style. At that time, Klodt was in charge of the foundry of the Academy of Arts and he was entrusted with casting the monument in bronze. Before casting, he had to reproduce a small figurine made at one time by Demut-Malinovsky on the gigantic scale of the monument. When performing this work, changes regarding the model are inevitable. It is impossible to assess these differences, since it is not possible to compare the draft design with the monument: the draft model has not been preserved. Klodt did a great job on the face of the sculpture, giving it an expression of spirituality and inspiration. The sculptor did his work very conscientiously, moved the statue from St. Petersburg to Kyiv, and very well chose a place for it: it is inscribed in the high mountainous landscape of the banks of the Dnieper.

Monument to Prince Vladimir of Kyiv

Monument to Nicholas I

The monument to the controversial but outstanding emperor was laid a year after his death - in 1856. It was initially a complex project, on which several sculptors were supposed to work, but the most important work - the embodiment of the figure of the sovereign - was entrusted to Klodt. He managed to successfully cope with the task only the second time - during the first attempt, the shape of the sculpture could not stand it, and the molten bronze flowed out. The heir of Nicholas, Alexander II, allowed the sculptor to make a secondary casting, which turned out to be successful. In order to take the sculpture out of the Imperial Academy of Arts, where it was cast, it was necessary to break down the walls: its dimensions were so large. June 25, 1859 the monument was inaugurated in the presence of Alexander II. Contemporaries were amazed at an unprecedented achievement: Klodt managed to ensure that the horseman's sculpture rested on just two points of support, on the horse's hind legs! In Europe, such a monument was erected for the first time, the only earlier example of such an embodiment of an engineering miracle was the American monument to President Andrew Jackson in the US capital. After the October Revolution of 1917, the question of dismantling the monument as a legacy of the tsarist regime was repeatedly raised, but the artistic genius of Klodt saved the monument from destruction: thanks to the uniqueness of the system of only two supports, it was recognized as a miracle of engineering and preserved.

The main theme in the work of P.K. Klodt - horses.

The main one, but not the only one: he also created a famous monument to the fabulist I.A. Krylov in the Summer Garden of St. Petersburg, a monument to Prince Vladimir in Kyiv and many other wonderful works.

A family

“The genealogy of the Klodt von Jurgensburg family” was compiled in German in March 1852 by the sculptor’s son, Mikhail Klodt. Major General Baron Karl Gustav, father of Peter Klodt, came from Baltic Germans. He was a military general, participated in the Patriotic War of 1812 and in other battles. His portrait is in the honorary gallery of the Winter Palace.

The family had 8 children: 6 sons and 2 daughters. The future sculptor was born on May 24, 1805 in St. Petersburg. In 1814, Baron Karl Gustav was appointed chief of staff of a separate Siberian Corps, and the family moved to Omsk. Here, in 1822, the father died, so the Klodt family returned to St. Petersburg.

Pyotr Karlovich Klodt

Pyotr Klodt decided to continue the military career of his ancestors (his grandfather was also a military man) and entered the St. Petersburg Artillery School as a cadet. He graduated from college at the age of 19 and was promoted to ensign. But since childhood, back in Omsk, he was fond of carving, modeling and drawing, he especially liked to depict horses, in which he saw a special charm. So in the struggle between a military career and artistic creativity, several years passed. Finally, Klodt finally made up his mind: he resigned, and after a while he became a volunteer at the Academy of Arts and devoted himself entirely to sculpture.

"Horse" theme

He constantly created figurines of horses (made of paper, wood), even while in military service. To decorate the desk of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, by order of Nicholas I, he created the figurine "Cavalier", which was very popular.

And finally, the real work: he received a government order and in 1833 created six horses for the Narva triumphal gates in St. Petersburg. The figures of horses were made of forged copper. The swift movement of the horses and the naturalness of their poses were masterfully conveyed.

Decoration of the Anichkov Bridge

Anichkov bridge

Having learned about the reconstruction of the Anichkov Bridge, Klodt proposed to decorate it with equestrian groups, and Nicholas I supported this idea. It was supposed to install two pairs of sculptural compositions "Horse Tamers" on four pedestals on the western and eastern sides of the bridge.

During the work, the head of the Foundry of the Imperial Academy of Arts, V.P. Ekimov, suddenly died, and Klodt had to manage the foundry himself.

First composition

A man tames the horse's run, squeezing the bridle with both hands, leaning on one knee. But an angry animal is not ready to obey.

Second composition

The man is thrown to the ground, the horse is trying to break free, triumphantly arching his neck. But with his left hand, the driver holds him tightly by the bridle.

Third composition

The front hooves of the animal in motion hung in the air, the head is upturned, the mouth is bared, the nostrils are inflated. The man tries to besiege him.

Fourth composition

The horse is submissive to a man who, squeezing the bridle, restrains the rearing animal. But the struggle between them is not over.

The bridge was opened after restoration on November 20, 1841, but bronze sculptures were only on the right bank of the Fontanka, and painted plaster copies were installed on the pedestals of the left bank.

In 1842, bronze sculptures were also made for the left bank, but the emperor presented them to the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV.

Horses of Klodt in front of the Berlin Castle

In 1843-1844. copies were made again and remained on the pedestals of the Anichkov Bridge until the spring of 1846. Nicholas I sent them to the Royal Palace in Naples.

Horses of Klodt in Naples

Several more copies of the sculptures were created, which were placed in different regions of Russia. For example, in the Golitsyn estate in Kuzminki.

In 1850, new bronze equestrian figures of Klodt were installed on the bridge, and at this the work on the design of the Anichkov Bridge was completed.

monuments

Monument to Emperor Nicholas I (St. Petersburg)

The 6-meter equestrian statue of Nicholas I is also P.K. Klodt completed in 1859 according to the project of the architect Auguste Montferrand, who conceived this monument as a unifying center of the architectural ensemble of the large St. Isaac's Square between the Mariinsky Palace and St. Isaac's Cathedral. The emperor is depicted in the ceremonial uniform of the Life Guards Cavalry Regiment. It is impossible not to note the technical skill of the sculpture - the setting of the horse on two points of support. For their strength, Klodt ordered iron supports weighing 60 pounds.

Several sculptors worked on the monument. Montferrand himself made the elliptical pedestal of the monument, which is made of crimson Karelian Shoksha quartzite and white Italian marble. The plinth is made of gray Serdobol granite.

Sculptor R.K. Zaleman created 4 allegorical female figures, personifying “Strength”, “Wisdom”, “Justice” and “Faith” (portrait images of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna and daughters of Nicholas I Maria, Alexandra and Olga. Between the first two statues there is a bronze gilded state emblem, under which is the inscription: "Nicholas I - Emperor of All Russia. 1859".

Four bas-reliefs on a pedestal depicting the main events of the reign of Nicholas I were made by sculptors N.A. Romazanov and R.K. Zaleman.

Bas-relief "Opening by the Emperor of the Verebyinsky Bridge of the St. Petersburg-Moscow Railway in 1851"

Monument to I.A. Krylov (St. Petersburg)

The initiator of the creation of the monument to Krylov was his friend General Rostovtsov, in whose hands the great fabulist died. The monument was created with public money collected by subscription. At the same time, the Academy of Arts announced a competition in which the leading sculptors of that time took part.

The competition was won by the project of the sculptor Baron von Klodt.

In 1855, Klodt installed a bronze statue of the fabulist in the Summer Garden of St. Petersburg on a granite pedestal, decorated with bronze images of people and animals - the characters of Krylov's fables. I. A. Krylov is depicted sitting on a stone and holding a pen and a notebook in his hands.

Characters of Krylov's fables on the front bas-relief of the pedestal

Monument to Prince Vladimir the Great (Kyiv)

This monument was created by a group of sculptors and architects: Pyotr Klodt made a statue of Vladimir, Alexander Ton - a pedestal, Vasily Demut-Malinovsky - bas-reliefs. The monument rises on the steep bank of the Dnieper in the Vladimirskaya Gorka park. It is a 4.5 m high bronze statue mounted on a 16 m high pedestal. The monument is made in the style of Russian classicism. Prince Vladimir is dressed in a flowing long cloak, in his hand he holds a cross with which the city is overshadowed.

The monument was erected in Kyiv in 1853.

Other sculptural works by P.K. Klodt

Together with sculptors A.V. Loganovsky, N.A. Romazanov and others. P. Klodt worked on the sculptures of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow.

In 1853, the building of the Bolshoi Theater burned down in Moscow; the fire lasted for several days, only the stone outer walls of the building and the colonnade of the portico survived. A competition was announced for the best project for the restoration of the theatre, which was won by the chief architect of the Imperial Theatres, Albert Cavos. The theater was restored in 3 years: Kavos increased the height of the building, changed the proportions and completely redesigned the architectural decor, designing the facades in the spirit of eclecticism. During the fire, the alabaster sculpture of Apollo over the entrance portico perished, instead of it they put a bronze quadriga by Peter Klodt.

Quadriga of Apollo on the facade of the Bolshoi Theater

A plaster coat of arms of the Russian Empire - a double-headed eagle - was installed on the pediment. The theater reopened on August 20, 1856.

In addition, Klodt worked all his life in small-form plastic: he created figurines that were highly valued by his contemporaries. Some of them are exhibited in the State Russian Museum.

Monument to Peter I in Kronstadt

An amazing effect of conveying the movement of a horse leaning on one leg was achieved by Klodt in the statuette “Major General F.I. Lefleur". Under the guidance of the sculptor, a monument to Peter I in Kronstadt (1841), a monument to N.M. Karamzin in Simbirsk (1845); monument to G.R. Derzhavin in Kazan (1847); according to his project, a monument to Ataman M.I. was erected in Novocherkassk. Platov (1853) and others.

Monument to Russian sculptor P.K. Klodt in the courtyard of the Academy of Arts (St. Petersburg)

All the free time that remained from learning the military craft, he gave to his hobby:

It is also known that during this period Klodt devoted a lot of time to studying the postures, gaits and habits of horses. "Comprehending the horse as a subject of artistic creativity, he had no other mentor than nature" .

After graduating from college, the future sculptor received the rank of second lieutenant. The officer served in the training artillery brigade until the age of 23, and after that in 1828 he left military service and decided to continue to engage exclusively in sculpture.

Sculptor

For two years, Klodt studied on his own, copied modern and antique works of art and worked from nature. Since 1830, he has been a volunteer at the Academy of Arts, his teachers were the rector of the Academy, IP Martos, as well as the masters of sculpture, S. I. Galberg and B. I. Orlovsky. They, approving the work and talent of the young sculptor, helped him to achieve success. All this time, Pyotr Karlovich lived and worked in one of the basements. He even brought horses there. There he painted them from various angles. Klodt studied the horse from all its sides and poses. Inside his workroom it was dirty, there were lumps of clay, drawings, sketches. The baron himself went to bed. People were perplexed: "How can a baron live in such squalor?"

Klodt's talent and perseverance brought unexpected dividends: from the beginning of the 1830s, his figurines depicting horses began to enjoy great success.

Horses of the Narva Gate

A strong continuation of his career was a large government order for the sculptural decoration of the Narva Gates, together with such experienced sculptors as S. S. Pimenov and V. I. Demut-Malinovsky. On the attic of the arch there is a six horses carrying the chariot of the goddess of glory, made of forged copper according to the model of Klodt in 1833. Unlike the classic images of this plot, the horses performed by Klodt are rapidly rushing forward and even rearing up. At the same time, the entire sculptural composition gives the impression of rapid movement.

After completing this work, the author received worldwide fame and the patronage of Nicholas I. There is a legend that Nicholas I said: "Well, Klodt, you make horses better than a stallion."

Anichkov bridge

In late 1832 - early 1833, the sculptor received a new government order for the execution of two sculptural groups to decorate the palace pier on the Admiralteyskaya Embankment. In the summer of 1833, Klodt made models for the project, and in August of the same year the models were approved by the emperor and delivered to the Academy of Arts for discussion.

Members of the academic council expressed their full satisfaction with the work of the sculptor and it was decided to complete both first groups in full size. After this success, there was a break in work on this project, due to the fact that Klodt was completing work on the sculptural composition of the Narva Gate.

This break ended in the mid-1830s and work on the project continued. Emperor Nicholas I, who oversaw the pier project, did not approve of the combination of lions and horses. Instead of the Dioscuri, vases were installed on the pier.

P. K. Klodt drew attention to the project for the reconstruction of the Anichkov Bridge and proposed placing the sculptures not on the piers of the Admiralteiskaya Embankment or on the Admiralteisky Boulevard, but to transfer them to the supports of the Anichkov Bridge.

The proposal was approved and the new project included the installation of two pairs of sculptural compositions on four pedestals on the western and eastern sides of the bridge.

By 1838 the first group had been realized in natural size and was ready to be translated into bronze.

Suddenly, an insurmountable obstacle arose: suddenly died, without leaving a successor, the head of the Foundry Yard of the Imperial Academy of Arts V. P. Ekimov.

Without this person, the casting of sculptures was impossible, as a result of which the sculptor decided to independently supervise the implementation of foundry work.

Wilkinus Pferdebändiger in St. Petersburg.jpg

Fourth composition

Anichkov bridge horse tamer 2.jpg

Third composition

Second composition

Anichkov bridge horse tamer 4.jpg

First composition

Incarnation in bronze

To carry out the work, he needed the skills of the basics of foundry, which he was taught at the artillery school, practically mastered in the service in artillery and applied in the lessons of V.P. Ekimov when Klodt was a volunteer at the academy.

Having headed the Foundry Yard in 1838, he began to improve, bringing technological innovations and modern methods to the work of production.

The fact that the sculptor became a caster brought unexpected results: most of the cast statues did not require additional processing (chasing or corrections).

To achieve this result, it was necessary to carefully work on the wax original with the reproduction of the smallest possibilities and the entire casting of the composition (up to this point, such large sculptures were cast in parts). Between 1838 and 1841, the sculptor managed to make two compositions in bronze and began preparations for casting the second pair of sculptures.

Two pairs of sculptural compositions stood on the side pedestals: bronze groups were located on the right bank of the Fontanka River (from the side of the Admiralty), painted plaster copies were installed on the pedestals of the left bank.

In Berlin

Re-castings were made in 1842, but they did not reach the bridge, the emperor presented this pair to the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV and, at his direction, the sculptures went to Berlin to decorate the main gate of the royal palace.

In Naples

In 1843-1844 copies were made again.

From 1844 until the spring of 1846, they remained on the pedestals of the Anichkov Bridge, then Nicholas I sent them to the "King of the Two Sicilies" Ferdinand II (to the Royal Palace in Naples).

Naples. The steed of Klodt. left group.jpg

Left group

Right group

Also, copies of the sculptures are installed in gardens and palace buildings in Russia: in the vicinity of St. Petersburg - near the Orlovsky Palace in Strelna and Peterhof, as well as on the territory of the Golitsyn estate in Kuzminki near Moscow, the Kuzminki-Vlakhernskoye estate.

Since 1846, plaster copies were again placed on the eastern side of the Anichkov Bridge, and the artist began to create a further continuation and completion of the ensemble.

The participants in the composition were the same: the horse and the driver, but they had different movements and composition, as well as a new plot.

It took the artist four years to complete the copies, and in 1850 the plaster sculptures finally disappeared from the Anichkov Bridge, and in their place the soldiers of the Engineer Battalion under the leadership of Baron Klodt hoisted new bronze figures. The work on the design of the Anichkov Bridge was completed.

Plot

- In the first group the animal is obedient to man - the naked athlete, squeezing the bridle, restrains the rearing horse. Both animal and man are tense, the struggle is growing.

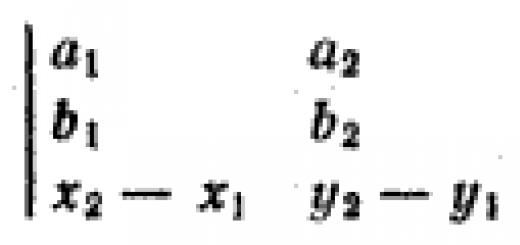

- This is shown by two main diagonals: the smooth silhouette of the neck and back of the horse, which can be seen against the sky, forms the first diagonal, which intersects with the diagonal formed by the figure of the athlete. Movements are marked with rhythmic repetitions.

- In the second group the head of the animal is upturned high, the mouth is bared, the nostrils are swollen, the horse beats with its front hooves in the air, the figure of the driver is deployed in the form of a spiral, he is trying to upset the horse.

- The main diagonals of the composition are approaching, the silhouettes of the horse and the driver seem to be intertwined.

- In the third group the horse overcomes the driver: the man is thrown to the ground, and the horse tries to break free, triumphantly arching his neck and throwing the blanket to the ground. The horse's freedom is hindered only by the bridle in the driver's left hand.

- The main diagonals of the composition are clearly expressed and their intersection is highlighted. The silhouettes of the horse and the driver form an open composition, in contrast to the first two sculptures.

- In the fourth group a man tames an angry animal: leaning on one knee, he tames the wild run of a horse, squeezing the bridle with both hands.

- The silhouette of the horse forms a very gentle diagonal, the silhouette of the driver is indistinguishable due to the drapery falling from the back of the horse. The silhouette of the monument again received isolation and balance.

prototypes

The figures of the Dioscuri in the Roman Forum on the Capitoline Hill served as a direct prototype for Klodt's horses, but these ancient sculptures had an unnatural movement motif, and there is also a violation of proportions: compared to the enlarged figures of young men, the horses look too small. Another prototype was the “Horses of Marley” by the French sculptor Guillaume Coustue, created by him around 1740, and located in Paris at the entrance to the Champs Elysees from Place de la Concorde. In the interpretation of Kustu, horses personify the animal principle, symbolize impetuous indomitable ferocity and are depicted as giants next to undersized drivers.

Klodt, in turn, depicted ordinary cavalry horses, the anatomy of which he studied for many years.

service house

In the 1845-1850s, Klodt took part in the restructuring of the “Service House” of the Marble Palace: according to the project of A.P. Bryullov, the lower floor was intended for the palace stables, and the building overlooking the garden was supposed to become an arena.

In connection with this purpose, to decorate the building along the facade, above the windows of the second floor, in the entire length of the middle part of the building, a seventy-meter relief "Horse in the service of man" was made.

It was made by Klodt according to the graphic sketch of the architect, it consisted of four blocks, not united by a common plot or idea:

- Fighting horsemen;

- Horse processions;

- Riding and chariot rides;

- Plots of hunting.

Art historians believe that this relief was made by Klodt in the image and likeness of horses on the frieze of the Parthenon.

This opinion is also supported by the Roman attire of the people depicted in the reliefs.

Klodt was able to apply an innovative technique: he made a monument, unlike the plastic images of commanders, kings, nobles, who in his time adorned St. Petersburg and Moscow, abandoning the usual language of allegories and creating a realistically accurate portrait image.

The sculptor depicted the fabulist sitting on a bench, dressed in casual clothes in a natural relaxed pose, as if he had sat down to rest under the lindens of the Summer Garden.

All these elements focus on the poet's face, in which the sculptor tried to convey the characteristics of Krylov's personality. The sculptor managed to embody the portrait and general likeness of the poet, which was recognized by his contemporaries.

The artist's idea went beyond a simple image of the poet, Klodt decided to create a sculptural composition, placing high-relief images of fable characters around the perimeter of the pedestal.

The images are illustrative, and to create the composition, Klodt in 1849 attracted the famous illustrator A. A. Agin to work.

Klodt transferred the figures to the pedestal, carefully comparing the images with living nature.

Work on the monument was completed in 1855.

Criticism of the monument

Klodt was criticized for petty pickiness in order to achieve maximum realism in the depiction of animals in high relief, the author was pointed out that the characters of the fables in the imagination of readers were rather allegorical than they were real crayfish, dogs, foxes.

Despite this criticism, the descendants highly appreciated the work of the sculptors, and the monument to Krylov took its rightful place in the history of Russian sculpture.

Monument to Prince Vladimir of Kyiv

The work ended with the presentation in 1835 of the project to the president of the Imperial Academy of Arts.

For unknown reasons, work on the project was suspended for a decade.

In 1846, Demut-Malinovsky died, after which the architect K. A. Ton took over the management of the work.

At the end of the same year, information appeared that "project approved". Ton re-arranged the project, taking as a basis the sketch of the Demuth-Malinovsky model and designed the pedestal in the form of a high tower-like church in pseudo-Byzantine style.

Klodt at that time was in charge of the foundry of the Academy of Arts, he was entrusted with casting the monument in bronze. Before casting, he had to reproduce a small figurine made at one time by Demut-Malinovsky on the gigantic scale of the monument.

When performing this work, changes regarding the model are inevitable.

It is impossible to assess these differences, since the sketch model has not been preserved.

Klodt did a great job on the face of the sculpture, giving it an expression of spirituality and inspiration.

The monument is a bronze statue 4.5 meters high, mounted on a pedestal 16 meters high. The monument is laconic and austere, it belongs to the typical examples of Russian classicism. Prince Vladimir is dressed in a long, flowing cloak, in his hand is a cross, which he stretches over the city.

Klodt did his job very conscientiously, moved the statue from St. Petersburg to Kyiv and very well chose a place for it: the statue is inscribed in the high mountainous landscape of the banks of the Dnieper.

Several sculptors worked on the design of the monument: Klodt himself made the figure of the emperor. The pedestal was designed by sculptors:

- N. A. Romazanov created three bas-reliefs.

- R. K. Zaleman in 1856-1858 executed four allegorical female figures: “Strength”, “Wisdom”, “Justice” and “Faith”, and a bas-relief on the same pedestal depicting the presentation of the Code of Laws by Count M. M. Speransky to the Emperor .

The top of the composition is the equestrian figure of the emperor. The original sketch, created by Klodt, was a rider on a calmly standing horse. The author, with the help of facial expressions and gestures, planned to reflect the character of the emperor, but this option was rejected by Montferrand due to the fact that he could not serve the original goal of combining spatial ensembles.

The sculptor created a new sketch. In it, abandoning the idea to characterize the character, he depicted a horse in motion, leaning only on the back pair of legs. At the same time, the impetuous posture of the horse is opposed by the ceremonial figure of the emperor, stretched into a string. To implement this sketch, the sculptor accurately calculated the weight of the entire equestrian figure in order for it to stand, relying on only two points of support. This option was accepted by the architect and embodied in bronze.

Technical mastery of the most difficult task - placing the horse on two points of support. For their strength, Klodt ordered iron supports at the best plant in Olonets (weighing 60 pounds, costing 2,000 silver rubles).

- Soviet historians and art historians did not highly appreciate the compositional and stylistic composition of the monument and noted that the elements do not look like a single composition:

- The pedestal, the reliefs on the pedestal and the equestrian statue are not subject to a single idea and to some extent contradict each other.

- The forms of the monument themselves are crushed and overloaded with small details, and the composition is pretentious and overly decorative.

- At the same time, the positive features of the composition were highlighted:

- It meets the intended purpose and, complementing the ensemble of the square, gives it completeness and integrity.

- All parts of the whole are professionally made by masters of their craft, the artistic value of the elements is undeniable.

- After the Revolution of 1917, the monument to Nicholas I on St. Isaac's Square was preparing for demolition, like everything related to tsarism, but thanks to a unique feature - the heavy equestrian statue rests only on its hind legs - it was recognized as a masterpiece of engineering and was not destroyed in Soviet times.

Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow

Together with the sculptors A. V. Loganovsky, N. A. Ramazanov and others, he worked on the sculptures of the temple-monument in the "Russian-Byzantine" style - the Cathedral of Christ the Savior (it took almost 40 years to build), from September 10, 1839. It was he, and not N.A. Ramazanov, who performed the high relief of the Great Martyr George on the north side of the temple, now located in the Donskoy Monastery (see "Historical Description of the Temple in the Name of Christ the Savior in Moscow" M. 1883 M. Mostovsky - head of the office temple building).

Summary of the life of a sculptor

In addition to the tangible legacy in the form of graphics and plastics, which the master left to his descendants, he conquered several more peaks in his life:

Small sculptural forms

Throughout his career, Klodt worked in the direction of plastics of small forms. The statuettes of this author were highly valued by his contemporaries. Some of them are included in the collections of museums such as the State Russian Museum.

Death

The artist spent the last years of his life at his dacha Khalola, where he died on November 8 (20).

In November 1867, blizzards blew when he lived at the dacha in Halola, and the granddaughter asked her grandfather to carve out a horse for her. Klodt took a playing card and scissors.

- Baby! When I was little, like you, my poor father also made me happy by cutting out horses from paper ... His face suddenly twisted, his granddaughter screamed:

- Grandpa, don't make me laugh with your grimaces!

Klodt staggered and collapsed to the floor.

see also

- Mikhail Petrovich Klodt (1835-1914) - artist, son of P. K. Klodt

Write a review on the article "Klodt, Pyotr Karlovich"

Notes

- // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg. , 1890-1907.

- Samoilov A. Koni Klodt // Artist. 1961, No. 12. S.29-34.

- Petrov V. N. Pyotr Karlovich Klodt / Designed by I. S. Serov. - L.: Artist of the RSFSR, 1973. - 60 p. - (Mass library on art). - 20,000 copies.(reg.)

- Petrov V. N. Pyotr Karlovich Klodt, 1805-1867. - L .: Artist of the RSFSR, 1985. - (Mass Library for Art).(reg.)

- Klodt G. A.“Pyotr Klodt sculpted and cast…” / Georgy Klodt; Hood. A. A. Zubchenko. - M .: Soviet artist, 1989. - 240 p. - (Stories about artists). - 25,000 copies. - ISBN 5-269-00030-X.(reg.)

- Klodt G. A. The Tale of My Ancestors / G. A. Klodt; Artist E. G. Klodt. - M .: Military Publishing House, 1997. - 304, p. - (Rare book). - 10,000 copies. - ISBN 5-203-01796-6.(in lane, superregional)

- Krivdina O. A. Sculptor Petr Karlovich Klodt. - St. Petersburg. : Ma'am, 2005. - 284 p. - ISBN 5-88718-042-0.(in lane, superregional)

- samlib.ru/s/shurygin_a_i/klodt.shtml Taming the recalcitrant

Links

- // Magazine "Golden Mustang" №2/2002

- Romm A. P. K. Klodt. - M.-L.: Art, 1948. - 50 p. - 0.13 k.

An excerpt characterizing Klodt, Pyotr Karlovich

Nothing, good people. How did you get into the headquarters?- Seconded, I'm on duty.

They were silent.

“I let the falcon out of my right sleeve,” said the song, involuntarily arousing a cheerful, cheerful feeling. Their conversation would probably have been different if they had not spoken at the sound of a song.

- What is true, the Austrians were beaten? Dolokhov asked.

“The devil knows, they say.

“I am glad,” Dolokhov answered briefly and clearly, as required by the song.

- Well, come to us when in the evening, the pharaoh will pawn, - said Zherkov.

Or do you have a lot of money?

- Come.

- It is forbidden. He gave a vow. I don't drink or play until it's done.

Well, before the first thing...

- You'll see it there.

Again they were silent.

“Come in, if you need anything, everyone at headquarters will help…” said Zherkov.

Dolokhov chuckled.

“You better not worry. What I need, I won't ask, I'll take it myself.

"Yeah, well, I'm so...

- Well, so am I.

- Goodbye.

- Be healthy…

... and high and far,

On the home side...

Zherkov touched his horse with his spurs, which three times, getting excited, kicked, not knowing where to start, coped and galloped, overtaking the company and catching up with the carriage, also in time with the song.

Returning from the review, Kutuzov, accompanied by the Austrian general, went to his office and, calling the adjutant, ordered to give himself some papers relating to the state of the incoming troops, and letters received from Archduke Ferdinand, who commanded the advanced army. Prince Andrei Bolkonsky with the required papers entered the office of the commander in chief. In front of the plan laid out on the table sat Kutuzov and an Austrian member of the Hofkriegsrat.

“Ah ...” said Kutuzov, looking back at Bolkonsky, as if by this word inviting the adjutant to wait, and continued the conversation begun in French.

“I only say one thing, General,” Kutuzov said with a pleasant elegance of expression and intonation, forcing one to listen to every leisurely spoken word. It was evident that Kutuzov listened to himself with pleasure. - I only say one thing, General, that if the matter depended on my personal desire, then the will of His Majesty Emperor Franz would have been fulfilled long ago. I would have joined the Archduke long ago. And believe my honor, that for me personally to transfer the higher command of the army more than I am to a knowledgeable and skillful general, such as Austria is so plentiful, and to lay down all this heavy responsibility for me personally would be a joy. But circumstances are stronger than us, general.

And Kutuzov smiled with an expression as if he were saying: “You have every right not to believe me, and even I don’t care whether you believe me or not, but you have no reason to tell me this. And that's the whole point."

The Austrian general looked dissatisfied, but could not answer Kutuzov in the same tone.

“On the contrary,” he said in a grouchy and angry tone, so contrary to the flattering meaning of the words spoken, “on the contrary, Your Excellency’s participation in the common cause is highly valued by His Majesty; but we believe that a real slowdown deprives the glorious Russian troops and their commanders of those laurels that they are accustomed to reap in battles, ”he finished the apparently prepared phrase.

Kutuzov bowed without changing his smile.

- And I am so convinced and, based on the last letter that His Highness Archduke Ferdinand honored me, I assume that the Austrian troops, under the command of such a skilled assistant as General Mack, have now already won a decisive victory and no longer need our help, - Kutuzov said.

The general frowned. Although there was no positive news about the defeat of the Austrians, there were too many circumstances confirming the general unfavorable rumors; and therefore Kutuzov's assumption about the victory of the Austrians was very similar to a mockery. But Kutuzov smiled meekly, still with the same expression that said that he had the right to assume this. Indeed, the last letter he received from Mack's army informed him of the victory and the most advantageous strategic position of the army.

“Give me this letter here,” said Kutuzov, turning to Prince Andrei. - Here you are, if you want to see it. - And Kutuzov, with a mocking smile on the ends of his lips, read the following passage from the letter of Archduke Ferdinand from the German-Austrian general: “Wir haben vollkommen zusammengehaltene Krafte, nahe an 70,000 Mann, um den Feind, wenn er den Lech passirte, angreifen und schlagen zu konnen. Wir konnen, da wir Meister von Ulm sind, den Vortheil, auch von beiden Uferien der Donau Meister zu bleiben, nicht verlieren; mithin auch jeden Augenblick, wenn der Feind den Lech nicht passirte, die Donau ubersetzen, uns auf seine Communikations Linie werfen, die Donau unterhalb repassiren und dem Feinde, wenn er sich gegen unsere treue Allirte mit ganzer Macht wenden wollte, seine Absicht alabald vereitelien. Wir werden auf solche Weise den Zeitpunkt, wo die Kaiserlich Ruseische Armee ausgerustet sein wird, muthig entgegenharren, und sodann leicht gemeinschaftlich die Moglichkeit finden, dem Feinde das Schicksal zuzubereiten, so er verdient.” [We have a fully concentrated force, about 70,000 people, so that we can attack and defeat the enemy if he crosses the Lech. Since we already own Ulm, we can retain the advantage of commanding both banks of the Danube, therefore, every minute, if the enemy does not cross the Lech, cross the Danube, rush to his communication line, cross the Danube lower and the enemy, if he decides to turn all his strength on our faithful allies, to prevent his intention from being fulfilled. Thus, we will cheerfully await the time when the imperial Russian army is completely ready, and then together we will easily find an opportunity to prepare the enemy for the fate he deserves.

Kutuzov sighed heavily, having finished this period, and carefully and affectionately looked at the member of the Hofkriegsrat.

“But you know, Your Excellency, the wise rule of assuming the worst,” said the Austrian general, apparently wanting to end the jokes and get down to business.

He glanced involuntarily at the adjutant.

“Excuse me, General,” Kutuzov interrupted him and also turned to Prince Andrei. - That's what, my dear, you take all the reports from our scouts from Kozlovsky. Here are two letters from Count Nostitz, here is a letter from His Highness Archduke Ferdinand, here's another,” he said, handing him some papers. - And from all this, cleanly, in French, make a memorandum, a note, for the visibility of all the news that we had about the actions of the Austrian army. Well, then, and present to his Excellency.

Prince Andrei bowed his head as a sign that he understood from the first words not only what was said, but also what Kutuzov would like to tell him. He collected the papers, and, giving a general bow, quietly walking along the carpet, went out into the waiting room.

Despite the fact that not much time has passed since Prince Andrei left Russia, he has changed a lot during this time. In the expression of his face, in his movements, in his gait, there was almost no noticeable former pretense, fatigue and laziness; he had the appearance of a man who has no time to think about the impression he makes on others, and is busy with pleasant and interesting business. His face expressed more satisfaction with himself and those around him; his smile and look were more cheerful and attractive.

Kutuzov, whom he caught up with back in Poland, received him very affectionately, promised him not to forget him, distinguished him from other adjutants, took him with him to Vienna and gave him more serious assignments. From Vienna, Kutuzov wrote to his old comrade, the father of Prince Andrei:

“Your son,” he wrote, “gives hope to be an officer who excels in his studies, firmness and diligence. I consider myself fortunate to have such a subordinate at hand.”

At Kutuzov's headquarters, among his comrades, and in the army in general, Prince Andrei, as well as in St. Petersburg society, had two completely opposite reputations.

Some, a minority, recognized Prince Andrei as something special from themselves and from all other people, expected great success from him, listened to him, admired him and imitated him; and with these people, Prince Andrei was simple and pleasant. Others, the majority, did not like Prince Andrei, they considered him an inflated, cold and unpleasant person. But with these people, Prince Andrei knew how to position himself in such a way that he was respected and even feared.

Coming out of Kutuzov's office into the waiting room, Prince Andrei with papers approached his comrade, adjutant on duty Kozlovsky, who was sitting by the window with a book.

- Well, what, prince? Kozlovsky asked.

- Ordered to draw up a note, why not let's go forward.

- And why?

Prince Andrew shrugged his shoulders.

- No word from Mac? Kozlovsky asked.

- Not.

- If it were true that he was defeated, then the news would come.

“Probably,” said Prince Andrei and went to the exit door; but at the same time, slamming the door to meet him, a tall, obviously newcomer, Austrian general in a frock coat, with a black scarf tied around his head and with the Order of Maria Theresa around his neck, quickly entered the waiting room. Prince Andrew stopped.

- General Anshef Kutuzov? - quickly said the visiting general with a sharp German accent, looking around on both sides and without stopping walking to the door of the office.

“The general is busy,” said Kozlovsky, hurriedly approaching the unknown general and blocking his way from the door. - How would you like to report?

The unknown general looked contemptuously down at the short Kozlovsky, as if surprised that he might not be known.

“The general chief is busy,” Kozlovsky repeated calmly.

The general's face frowned, his lips twitched and trembled. He took out a notebook, quickly drew something with a pencil, tore out a piece of paper, gave it away, went with quick steps to the window, threw his body on a chair and looked around at those in the room, as if asking: why are they looking at him? Then the general raised his head, stretched out his neck, as if intending to say something, but immediately, as if carelessly starting to hum to himself, made a strange sound, which was immediately stopped. The door of the office opened, and Kutuzov appeared on the threshold. The general with his head bandaged, as if running away from danger, bent over, with large, quick steps of thin legs, approached Kutuzov.

- Vous voyez le malheureux Mack, [You see the unfortunate Mack.] - he said in a broken voice.

The face of Kutuzov, who was standing in the doorway of the office, remained completely motionless for several moments. Then, like a wave, a wrinkle ran over his face, his forehead smoothed out; he bowed his head respectfully, closed his eyes, silently let Mack pass him, and closed the door behind him.

The rumor, already spread before, about the defeat of the Austrians and the surrender of the entire army at Ulm, turned out to be true. Half an hour later, adjutants were sent in different directions with orders proving that soon the Russian troops, who had been inactive until now, would have to meet with the enemy.

Prince Andrei was one of those rare officers on staff who considered his main interest in the general course of military affairs. Seeing Mack and hearing the details of his death, he realized that half of the campaign was lost, understood the whole difficulty of the position of the Russian troops and vividly imagined what awaited the army, and the role that he would have to play in it.

Involuntarily, he experienced an exciting joyful feeling at the thought of shaming presumptuous Austria and that in a week, perhaps, he would have to see and take part in a clash between Russians and French, for the first time after Suvorov.

But he was afraid of the genius of Bonaparte, who could be stronger than all the courage of the Russian troops, and at the same time he could not allow shame for his hero.

Excited and irritated by these thoughts, Prince Andrei went to his room to write to his father, to whom he wrote every day. He met in the corridor with his roommate Nesvitsky and the joker Zherkov; they, as always, laughed at something.

Why are you so gloomy? Nesvitsky asked, noticing the pale face of Prince Andrei with sparkling eyes.

“There is nothing to have fun,” answered Bolkonsky.

While Prince Andrei met with Nesvitsky and Zherkov, on the other side of the corridor Strauch, an Austrian general who was at Kutuzov's headquarters to monitor the food of the Russian army, and a member of the Hofkriegsrat, who had arrived the day before, were walking towards them. There was enough space along the wide corridor for the generals to disperse freely with three officers; but Zherkov, pushing Nesvitsky away with his hand, said in a breathless voice:

- They're coming! ... they're coming! ... step aside, the road! please way!

The generals passed with an air of desire to get rid of troubling honors. On the face of the joker Zherkov suddenly expressed a stupid smile of joy, which he seemed unable to contain.

“Your Excellency,” he said in German, moving forward and addressing the Austrian general. I have the honor to congratulate you.

He bowed his head and awkwardly, like children learning to dance, began to scrape one leg or the other.

The General, a member of the Hofkriegsrath, looked sternly at him; not noticing the seriousness of the stupid smile, he could not refuse a moment's attention. He squinted to show he was listening.

“I have the honor to congratulate you, General Mack has arrived, quite healthy, only a little hurt here,” he added, beaming with a smile and pointing to his head.

The general frowned, turned away, and walked on.

Gott, wie naive! [My God, how simple he is!] – he said angrily, moving away a few steps.

Nesvitsky embraced Prince Andrei with laughter, but Bolkonsky, turning even paler, with an evil expression on his face, pushed him away and turned to Zherkov. That nervous irritation into which the sight of Mack, the news of his defeat, and the thought of what awaited the Russian army had brought him, found its outlet in bitterness at Zherkov's inappropriate joke.

“If you, dear sir,” he spoke piercingly with a slight trembling of his lower jaw, “want to be a jester, then I cannot prevent you from doing so; but I announce to you that if you dare another time to clown in my presence, then I will teach you how to behave.

Nesvitsky and Zherkov were so surprised by this trick that they silently, with their eyes wide open, looked at Bolkonsky.

“Well, I only congratulated you,” said Zherkov.

- I'm not joking with you, if you please be silent! - Bolkonsky shouted and, taking Nesvitsky by the hand, he walked away from Zherkov, who could not find what to answer.

“Well, what are you, brother,” Nesvitsky said reassuringly.

- Like what? - Prince Andrei spoke, stopping from excitement. - Yes, you understand that we, or officers who serve their tsar and fatherland and rejoice at the common success and grieve about the common failure, or we are lackeys who do not care about the master's business. Quarante milles hommes massacres et l "ario mee de nos allies detruite, et vous trouvez la le mot pour rire," he said, as if reinforcing his opinion with this French phrase. - C "est bien pour un garcon de rien, comme cet individu , dont vous avez fait un ami, mais pas pour vous, pas pour vous. [Forty thousand people died and our allied army was destroyed, and you can joke about it. This is forgivable to an insignificant boy, like this gentleman whom you have made your friend, but not to you, not to you.] Boys can only be so amused, - said Prince Andrei in Russian, pronouncing this word with a French accent, noting that Zherkov could still hear it.

He waited for the cornet to answer. But the cornet turned and walked out of the corridor.

The Pavlograd Hussar Regiment was stationed two miles from Braunau. The squadron, in which Nikolai Rostov served as a cadet, was located in the German village of Salzenek. The squadron commander, captain Denisov, known to the entire cavalry division under the name of Vaska Denisov, was assigned the best apartment in the village. Junker Rostov had been living with the squadron commander ever since he caught up with the regiment in Poland.

On October 11, on the very day when everything in the main apartment was raised to its feet by the news of Mack's defeat, camping life at the squadron headquarters calmly went on as before. Denisov, who had been losing all night at cards, had not yet returned home when Rostov, early in the morning, on horseback, returned from foraging. Rostov, in a cadet uniform, rode up to the porch, pushed the horse, threw off his leg with a flexible, young gesture, stood on the stirrup, as if not wanting to part with the horse, finally jumped down and called out to the messenger.

“Ah, Bondarenko, dear friend,” he said to the hussar, who rushed headlong to his horse. “Let me out, my friend,” he said with that brotherly, cheerful tenderness with which good young people treat everyone when they are happy.

“I’m listening, your excellency,” answered the Little Russian, shaking his head merrily.

- Look, take it out well!

Another hussar also rushed to the horse, but Bondarenko had already thrown over the reins of the snaffle. It was evident that the junker gave well for vodka, and that it was profitable to serve him. Rostov stroked the horse's neck, then its rump, and stopped on the porch.

“Glorious! Such will be the horse! he said to himself, and, smiling and holding his saber, he ran up to the porch, rattling his spurs. The German owner, in a sweatshirt and cap, with a pitchfork, with which he cleaned the manure, looked out of the barn. The German's face suddenly brightened as soon as he saw Rostov. He smiled cheerfully and winked: “Schon, gut Morgen! Schon, gut Morgen!" [Fine, good morning!] he repeated, apparently finding pleasure in greeting the young man.

– Schonfleissig! [Already at work!] - said Rostov, still with the same joyful, brotherly smile that did not leave his animated face. – Hoch Oestreicher! Hoch Russen! Kaiser Alexander hoch! [Hooray Austrians! Hooray Russians! Emperor Alexander hurray!] - he turned to the German, repeating the words often spoken by the German host.

The German laughed, went completely out of the barn door, pulled

cap and, waving it over his head, shouted:

– Und die ganze Welt hoch! [And the whole world cheers!]

Rostov himself, just like a German, waved his cap over his head and, laughing, shouted: “Und Vivat die ganze Welt!” Although there was no reason for special joy either for the German who was cleaning his cowshed, or for Rostov, who went with a platoon for hay, both of these people looked at each other with happy delight and brotherly love, shook their heads in a sign of mutual love and parted smiling - the German to the barn, and Rostov to the hut he shared with Denisov.

- What's the sir? he asked Lavrushka, the rogue lackey Denisov known to the entire regiment.

Haven't been since the evening. It’s true, we lost,” answered Lavrushka. “I already know that if they win, they will come early to show off, but if they don’t until morning, then they’ve blown away, the angry ones will come. Would you like coffee?

- Come on, come on.

After 10 minutes, Lavrushka brought coffee. They're coming! - he said, - now the trouble. - Rostov looked out the window and saw Denisov returning home. Denisov was a small man with a red face, shining black eyes, black tousled mustache and hair. He was wearing an unbuttoned mentic, wide chikchirs lowered in folds, and a crumpled hussar cap was put on the back of his head. He gloomily, lowering his head, approached the porch.

“Lavg” ear, ”he shouted loudly and angrily. “Well, take it off, blockhead!

“Yes, I’m filming anyway,” answered Lavrushka’s voice.

- BUT! you already got up, - said Denisov, entering the room.

- For a long time, - said Rostov, - I already went for hay and saw Fraulein Matilda.

– That's how! And I pg "puffed up, bg" at, vcheg "a, like a son of a bitch!" shouted Denisov, without pronouncing the river. - Such a misfortune! Such a misfortune! As you left, so it went. Hey, tea!

Denisov, grimacing, as if smiling and showing his short, strong teeth, began to ruffle his black, thick hair, like a dog, with both hands with short fingers.

- Chog "t me money" zero to go to this kg "yse (nickname of the officer)," he said, rubbing his forehead and face with both hands. "You didn't.

Denisov took the lighted pipe handed to him, clenched it into a fist, and, scattering fire, hit it on the floor, continuing to shout.

- The sempel will give, pag "ol beats; the sempel will give, pag" ol beats.

He scattered the fire, smashed the pipe and threw it away. Denisov paused, and suddenly, with his shining black eyes, looked merrily at Rostov.

- If only there were women. And then here, kg "oh how to drink, there is nothing to do. If only she could get away."

- Hey, who's there? - he turned to the door, hearing the stopped steps of thick boots with the rattling of spurs and a respectful cough.

- Wahmister! Lavrushka said.

Denisov frowned even more.

“Squeeg,” he said, throwing a purse with several gold pieces. “Gostov, count, my dear, how much is left there, but put the purse under the pillow,” he said and went out to the sergeant-major.

Rostov took the money and, mechanically, putting aside and leveling heaps of old and new gold, began to count them.

- BUT! Telyanin! Zdog "ovo! Inflate me all at once" ah! Denisov's voice was heard from another room.

- Who? At Bykov's, at the rat's? ... I knew, - said another thin voice, and after that Lieutenant Telyanin, a small officer of the same squadron, entered the room.

Rostov threw a purse under the pillow and shook the small, damp hand extended to him. Telyanin was transferred from the guard before the campaign for something. He behaved very well in the regiment; but they did not like him, and in particular Rostov could neither overcome nor hide his unreasonable disgust for this officer.

- Well, young cavalryman, how does my Grachik serve you? - he asked. (Grachik was a riding horse, a tack, sold by Telyanin to Rostov.)

The lieutenant never looked into the eyes of the person with whom he spoke; His eyes were constantly moving from one object to another.

- I saw you drove today ...

“Nothing, good horse,” answered Rostov, despite the fact that this horse, bought by him for 700 rubles, was not worth even half of this price. “I began to crouch on the left front ...” he added. - Cracked hoof! It's nothing. I will teach you, show you which rivet to put.

“Yes, please show me,” said Rostov.

- I'll show you, I'll show you, it's not a secret. And thank you for the horse.

“So I order the horse to be brought,” said Rostov, wanting to get rid of Telyanin, and went out to order the horse to be brought.

In the passage, Denisov, with a pipe, crouched on the threshold, sat in front of the sergeant-major, who was reporting something. Seeing Rostov, Denisov frowned and, pointing over his shoulder with his thumb into the room in which Telyanin was sitting, grimaced and shook with disgust.

“Oh, I don’t like the good fellow,” he said, not embarrassed by the presence of the sergeant-major.

Rostov shrugged his shoulders, as if to say: "So do I, but what can I do!" and, having ordered, returned to Telyanin.

Telyanin sat still in the same lazy pose in which Rostov had left him, rubbing his small white hands.

"There are such nasty faces," thought Rostov, entering the room.

“Well, did you order the horse to be brought?” - said Telyanin, getting up and casually looking around.

- Velel.

- Come on, let's go. After all, I only came to ask Denisov about yesterday's order. Got it, Denisov?

- Not yet. Where are you?

“I want to teach a young man how to shoe a horse,” said Telyanin.

They went out onto the porch and into the stables. The lieutenant showed how to make a rivet and went to his room.

When Rostov returned, there was a bottle of vodka and sausage on the table. Denisov sat in front of the table and cracked pen on paper. He looked gloomily into Rostov's face.

“I am writing to her,” he said.

He leaned on the table with a pen in his hand, and, obviously delighted with the opportunity to quickly say in a word everything that he wanted to write, expressed his letter to Rostov.

- You see, dg "ug," he said. "We sleep until we love. We are the children of pg`axa ... but you fell in love - and you are God, you are pure, as on the peg" day of creation ... Who else is this? Send him to the chog "tu. No time!" he shouted at Lavrushka, who, not at all shy, approached him.

- But who should be? They themselves ordered. The sergeant-major came for the money.

Denisov frowned, wanted to shout something and fell silent.

“Squeeg,” but that’s the point, he said to himself. “How much money is left in the wallet?” he asked Rostov.

“Seven new ones and three old ones.

“Ah, skweg,” but! Well, what are you standing, scarecrows, send a wahmistg “a,” Denisov shouted at Lavrushka.

“Please, Denisov, take my money, because I have it,” said Rostov, blushing.

“I don’t like to borrow from my own, I don’t like it,” grumbled Denisov.

“And if you don’t take money from me comradely, you will offend me. Really, I have, - repeated Rostov.

- No.

And Denisov went to the bed to get a wallet from under the pillow.

- Where did you put it, Rostov?

- Under the bottom cushion.

- Yes, no.

Denisov threw both pillows on the floor. There was no wallet.

- That's a miracle!

“Wait, didn’t you drop it?” said Rostov, picking up the pillows one at a time and shaking them out.

He threw off and brushed off the blanket. There was no wallet.

- Have I forgotten? No, I also thought that you were definitely putting a treasure under your head, ”said Rostov. - I put my wallet here. Where is he? he turned to Lavrushka.

- I didn't go in. Where they put it, there it should be.

- Well no…

- You're all right, throw it somewhere, and forget it. Look in your pockets.

“No, if I didn’t think about the treasure,” said Rostov, “otherwise I remember what I put in.”

Lavrushka rummaged through the whole bed, looked under it, under the table, rummaged through the whole room and stopped in the middle of the room. Denisov silently followed Lavrushka's movements, and when Lavrushka spread his arms in surprise, saying that he was nowhere to be found, he looked back at Rostov.

- Mr. Ostov, you are not a schoolboy ...

Rostov felt Denisov's gaze on him, raised his eyes and at the same moment lowered them. All his blood, which had been locked up somewhere below his throat, gushed into his face and eyes. He couldn't catch his breath.

- And there was no one in the room, except for the lieutenant and yourself. Here somewhere,” said Lavrushka.

- Well, you, chog "those doll, turn around, look," Denisov suddenly shouted, turning purple and throwing himself at the footman with a menacing gesture. Zapog everyone!

Rostov, looking around Denisov, began to button up his jacket, fastened his saber and put on his cap.

“I’m telling you to have a wallet,” Denisov shouted, shaking the batman’s shoulders and pushing him against the wall.

- Denisov, leave him; I know who took it,” said Rostov, going up to the door and not raising his eyes.

Denisov stopped, thought, and, apparently understanding what Rostov was hinting at, grabbed his hand.

“Sigh!” he shouted so that the veins, like ropes, puffed out on his neck and forehead. “I’m telling you, you’re crazy, I won’t allow it. The wallet is here; I will loosen my skin from this meg'zavetz, and it will be here.

“I know who took it,” Rostov repeated in a trembling voice and went to the door.

“But I’m telling you, don’t you dare do this,” Denisov shouted, rushing to the cadet to restrain him.

But Rostov tore his hand away and with such malice, as if Denisov was his greatest enemy, directly and firmly fixed his eyes on him.

– Do you understand what you are saying? he said in a trembling voice, “there was no one else in the room except me. So, if not, then...

He could not finish and ran out of the room.

“Ah, why not with you and with everyone,” were the last words that Rostov heard.

Rostov came to Telyanin's apartment.

“The master is not at home, they have gone to the headquarters,” Telyanin’s orderly told him. Or what happened? added the batman, surprised at the junker's upset face.

- There is nothing.

“We missed a little,” said the batman.

The headquarters was located three miles from Salzenek. Rostov, without going home, took a horse and rode to headquarters. In the village occupied by the headquarters, there was a tavern frequented by officers. Rostov arrived at the tavern; at the porch he saw Telyanin's horse.

In the second room of the tavern the lieutenant was sitting at a dish of sausages and a bottle of wine.

“Ah, and you stopped by, young man,” he said, smiling and raising his eyebrows high.

- Yes, - said Rostov, as if it took a lot of effort to pronounce this word, and sat down at the next table.

Both were silent; two Germans and one Russian officer were sitting in the room. Everyone was silent, and the sounds of knives on plates and the lieutenant's champing could be heard. When Telyanin had finished breakfast, he took a double purse out of his pocket, spread the rings with his little white fingers bent upwards, took out a gold one, and, raising his eyebrows, gave the money to the servant.

“Please hurry,” he said.

Gold was new. Rostov got up and went over to Telyanin.

“Let me see the purse,” he said in a low, barely audible voice.

With shifty eyes, but still raised eyebrows, Telyanin handed over the purse.

"Yes, a pretty purse... Yes... yes..." he said, and suddenly turned pale. “Look, young man,” he added.

Rostov took the wallet in his hands and looked at it, and at the money that was in it, and at Telyanin. The lieutenant looked around, as was his habit, and seemed to suddenly become very cheerful.

“If we’re in Vienna, I’ll leave everything there, and now there’s nowhere to go in these crappy little towns,” he said. - Come on, young man, I'll go.

Rostov was silent.

- What about you? have breakfast too? They are decently fed,” continued Telyanin. - Come on.

He reached out and took hold of the wallet. Rostov released him. Telyanin took the purse and began to put it into the pocket of his breeches, and his eyebrows casually rose, and his mouth opened slightly, as if he were saying: “Yes, yes, I put my purse in my pocket, and it’s very simple, and no one cares about this” .

- Well, what, young man? he said, sighing and looking into Rostov's eyes from under his raised eyebrows. Some kind of light from the eyes, with the speed of an electric spark, ran from Telyanin's eyes to Rostov's eyes and back, back and back, all in an instant.

“Come here,” said Rostov, grabbing Telyanin by the hand. He almost dragged him to the window. - This is Denisov's money, you took it ... - he whispered in his ear.

Boy, youth, officer

The family of the future sculptor consisted of hereditary military men. As is often the case, the surname was not rich, albeit well-born. His great-great-grandfather was one of the famous figures of the Northern War, he was a major general in the Swedish service. The sculptor's father was a military general who fought in the Patriotic War of 1812. The portrait of the illustrious general occupies a worthy place in the gallery of the Winter Palace.

Despite the fact that P. K. Klodt was born in 1805 in St. Petersburg, his childhood and youth were spent in Omsk, where his father served as chief of staff of the Separate Siberian Corps. There, far from the standards of metropolitan education, far from European culture, the baron's penchant for carving, modeling and drawing manifested itself. Most of all, the boy liked to portray horses, he saw a special charm in them.

Like his ancestors, the boy was preparing for a military career. In 1822, at the age of 17, he returned to the capital and entered the artillery school. All the free time that remained from learning the military craft, he gave to his hobby:

It is also known that during this period Klodt devoted a lot of time to studying the postures, gaits and habits of horses. "Comprehending the horse as a subject of artistic creativity, he had no other mentor than nature" .

After graduating from college, the future sculptor received the rank of second lieutenant. The officer served in the training artillery brigade until the age of 23, and after that in 1828 he left military service and decided to continue to engage exclusively in sculpture.

Sculptor

For two years, Klodt studied on his own, copied modern and antique works of art and worked from nature. Since 1830, he has been a volunteer at the Academy of Arts, his teachers were the rector of the Academy, IP Martos, as well as the masters of sculpture, S. I. Galberg and B. I. Orlovsky. They, approving the work and talent of the young sculptor, helped him to achieve success.

Klodt's talent and perseverance brought unexpected dividends: from the beginning of the 1830s, his figurines depicting horses began to enjoy great success.

Narva triumphal gates

Horses of the Narva Gate

A strong continuation of his career was a large government order for the sculptural decoration of the Narva Gates, together with such experienced sculptors as S. S. Pimenov and V. I. Demut-Malinovsky. Six horses are installed on the attic of the arch, carrying the chariot of the goddess of glory, made of forged copper according to the model of Klodt in 1833. Unlike the classic images of this plot, the horses performed by Klodt are rapidly rushing forward and even rearing up. At the same time, the entire sculptural composition gives the impression of rapid movement.

First composition

Anichkov bridge

In late 1832 - early 1833, the sculptor received a new government order for the execution of two sculptural groups to decorate the palace pier on the Admiralteyskaya Embankment. In the summer of 1833, Klodt made models for the project, and in August of the same year the models were approved by the emperor and delivered to the Academy of Arts for discussion. Members of the academic council expressed their full satisfaction with the work of the sculptor and it was decided to complete both first groups in full size.

After this success, there was a break in work on this project, due to the fact that Klodt was completing work on the sculptural composition of the Narva Gate. This break ended in the mid-1830s and work on the project continued. Emperor Nicholas I, who oversaw the pier project, did not approve of the combination of lions and horses. Instead of the Dioscuri, vases were installed on the pier.

P. K. Klodt drew attention to the project for the reconstruction of the Anichkov Bridge and proposed placing the sculptures not on the piers of the Admiralteiskaya Embankment or on the Admiralteisky Boulevard, but to transfer them to the supports of the Anichkov Bridge.

Second composition

The proposal was approved and the new project included the installation of two pairs of sculptural compositions on four pedestals on the western and eastern sides of the bridge. By 1838 the first group had been realized in natural size and was ready to be translated into bronze. An insurmountable obstacle suddenly arose: the head of the Foundry of the Imperial Academy of Arts, V.P. Ekimov, suddenly died without leaving a successor. Without this person, the casting of sculptures was impossible, and the sculptor decided to manage the casting work on his own.

Incarnation in bronze

To carry out the work, he needed the skills of the basics of foundry, which he was taught at the artillery school, practically mastered in the service in artillery and applied in the lessons of V.P. Ekimov when Klodt was a volunteer at the academy. Having headed the Foundry Yard in 1838, he began to improve, bringing technological innovations and modern methods to the work of production. The fact that the sculptor became a caster brought unexpected results: most of the cast statues did not require additional processing (chasing or corrections). To achieve this result, it was necessary to carefully work on the wax original with the reproduction of the smallest possibilities and the entire casting of the composition (up to this point, such large sculptures were cast in parts). Between 1838 and 1841, the sculptor managed to make two compositions in bronze and began preparations for casting the second pair of sculptures.

Third composition

On November 20, 1841, the bridge was opened after restoration. Two pairs of sculptural compositions stood on the side pedestals: bronze groups were located on the right bank of the Fontanka River (from the side of the Admiralty), painted plaster copies were installed on the pedestals of the left bank.

Re-castings were made in 1842, but they did not reach the bridge, the emperor presented this pair to the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm III and, at his direction, the sculptures went to Berlin to decorate the main gate of the imperial palace.

In 1843-1844 copies were made again. From 1844 until the spring of 1846, they remained on the pedestals of the Anichkov Bridge, then Nicholas I sent them to the "King of the Two Sicilies" Victor Emmanuel II (at the Royal Palace in Naples).

Also, copies of the sculptures are installed in gardens and palace buildings in Russia: in the vicinity of St. Petersburg Strelna and Petrodvorets, as well as on the territory of the Golitsyn estate in Kuzminki near Moscow, the Kuzminki-Vlakhernskoye estate.

Fourth composition

Since 1846, plaster copies were again placed on the eastern side of the Anichkov Bridge, and the artist began to create a further continuation and completion of the ensemble. The participants in the composition were the same: the horse and the driver, but they had different movements and composition, as well as a new plot. It took the artist four years to complete the sequel, and in 1850 the plaster sculptures finally disappeared from the Anichkov Bridge, and in their place the soldiers of the Engineer Battalion under the leadership of Baron Klodt hoisted new bronze figures into place. The work on the design of the Anichkov Bridge was completed.

Plot

- In the first group the animal is obedient to man - the naked athlete, squeezing the bridle, restrains the rearing horse. Both animal and man are tense, the struggle is growing.

- This is shown by two main diagonals: the smooth silhouette of the neck and back of the horse, which can be seen against the sky, forms the first diagonal, which intersects with the diagonal formed by the figure of the athlete. Movements are marked with rhythmic repetitions.

- In the second group the head of the animal is upturned high, the mouth is bared, the nostrils are swollen, the horse beats with its front hooves in the air, the figure of the driver is deployed in the form of a spiral, he is trying to upset the horse.

- The main diagonals of the composition are approaching, the silhouettes of the horse and the driver seem to be intertwined.

- In the third group the horse overcomes the driver: the man is thrown to the ground, and the horse tries to break free, triumphantly arching his neck and throwing the blanket to the ground. The horse's freedom is hindered only by the bridle in the driver's left hand.

- The main diagonals of the composition are clearly expressed and their intersection is highlighted. The silhouettes of the horse and the driver form an open composition, in contrast to the first two sculptures.

- In the fourth group a man tames an angry animal: leaning on one knee, he tames the wild run of a horse, squeezing the bridle with both hands.

- The silhouette of the horse forms a very gentle diagonal, the silhouette of the driver is indistinguishable due to the drapery falling from the back of the horse. The silhouette of the monument again received isolation and balance.

prototypes

The figures of the Dioscuri in the Roman Forum on the Capitoline Hill served as a direct prototype for Klodt's horses, but these ancient sculptures had an unnatural movement motif, and there is also a violation of proportions: compared to the enlarged figures of young men, the horses look too small.

Cony Marley

Another prototype was the “Horses of Marley” by the French sculptor Guillaume Coustue (fr.), created by him around 1740, and located in Paris at the entrance to the Champs Elysees from Place de la Concorde. In the interpretation of Kustu, horses personify the animal principle, symbolize impetuous indomitable ferocity and are depicted as giants next to undersized drivers.