Caucasian War (1817-1864) - military actions of the Russian Imperial Army associated with the annexation of the mountainous regions of the North Caucasus to Russia, confrontation with the North Caucasus Imamate.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Georgian Kartli-Kakheti kingdom (1801-1810), as well as some, mainly Azerbaijani, Transcaucasian khanates (1805-1813), became part of the Russian Empire. However, between the acquired lands and Russia lay the lands of those who swore allegiance to Russia, but were de facto independent mountain peoples, predominantly professing Islam. The fight against the raiding system of the mountaineers became one of the main goals of Russian policy in the Caucasus. Many mountain peoples of the northern slopes of the Main Caucasus range showed fierce resistance to the growing influence of imperial power. The most fierce military actions took place in the period 1817-1864. The main areas of military operations are the Northwestern (Circassia, mountain societies of Abkhazia) and Northeastern (Dagestan, Chechnya) Caucasus. Periodically, armed clashes between the highlanders and Russian troops took place in the territory of Transcaucasia and Kabarda.

After the pacification of Greater Kabarda (1825), the main opponents of the Russian troops were the Circassians of the Black Sea coast and the Kuban region, and in the east - the highlanders, united in a military-theocratic Islamic state - the Imamate of Chechnya and Dagestan, headed by Shamil. At this stage, the Caucasian War became intertwined with Russia's war against Persia. Military operations against the mountaineers were carried out by significant forces and were very fierce.

From the mid-1830s. The conflict escalated due to the emergence in Chechnya and Dagestan of a religious and political movement under the flag of Gazavat, which received moral and military support from the Ottoman Empire, and during the Crimean War - from Great Britain. The resistance of the highlanders of Chechnya and Dagestan was broken only in 1859, when Imam Shamil was captured. The war with the Adyghe tribes of the Western Caucasus continued until 1864, and ended with the destruction and expulsion of most of the Adygs and Abazas to the Ottoman Empire, and the resettlement of the remaining small number of them to the flat lands of the Kuban region. The last large-scale military operations against the Circassians were carried out in October-November 1865.

Name

Concept "Caucasian War" introduced by the Russian military historian and publicist, a contemporary of the military operations R. A. Fadeev (1824-1883) in the book “Sixty Years of the Caucasian War” published in 1860. The book was written on behalf of the commander-in-chief in the Caucasus, Prince A.I. Baryatinsky. However, pre-revolutionary and Soviet historians up until the 1940s preferred the term "Caucasian Wars of the Empire".

In the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, the article about the war was called “The Caucasian War of 1817-64.”

After the collapse of the USSR and the formation of the Russian Federation, separatist tendencies intensified in the autonomous regions of Russia. This was reflected in the attitude towards the events in the North Caucasus (and, in particular, the Caucasian War), and in their assessment.

In the work “The Caucasian War: Lessons of History and Modernity,” presented in May 1994 at a scientific conference in Krasnodar, historian Valery Ratushnyak talks about “ Russian-Caucasian war, which lasted a century and a half."

In the book “Unconquered Chechnya,” published in 1997 after the First Chechen War, public and political figure Lema Usmanov called the war of 1817-1864 “ First Russian-Caucasian War" Political scientist Viktor Chernous noted that the Caucasian War was not only the longest in the history of Russia, but also the most controversial, to the point of its denial or assertion of several Caucasian wars.

Ermolovsky period (1816-1827)

In the summer of 1816, Lieutenant General Alexey Ermolov, who had won respect in the wars with Napoleon, was appointed commander of the Separate Georgian Corps, manager of the civil sector in the Caucasus and Astrakhan province. In addition, he was appointed ambassador extraordinary to Persia.

In 1816, Ermolov arrived in the Caucasus province. In 1817, he traveled to Persia for six months to the court of Shah Feth Ali and concluded a Russian-Persian treaty.

On the Caucasian line, the state of affairs was as follows: the right flank of the line was threatened by the Trans-Kuban Circassians, the center by the Kabardians (Circassians of Kabarda), and against the left flank across the Sunzha River lived the Chechens, who enjoyed a high reputation and authority among the mountain tribes. At the same time, the Circassians were weakened by internal strife, the Kabardians were decimated by the plague - the danger threatened primarily from the Chechens.

Having familiarized himself with the situation on the Caucasian line, Ermolov outlined a plan of action, which he then adhered to unswervingly. Among the components of Ermolov's plan were cutting clearings in impenetrable forests, building roads and erecting fortifications. In addition, he believed that not a single attack by the mountaineers could be left unpunished.

Ermolov moved the left flank of the Caucasian line from the Terek to the Sunzha, where he strengthened the Nazran redoubt and laid out the fortification of Pregradny Stan in its middle reaches in October 1817. In 1818, the Grozny fortress was founded in the lower reaches of the Sunzha. In 1819, the Vnezapnaya fortress was built. An attempt to attack it by the Avar Khan ended in complete failure.

In December 1819, Ermolov made a trip to the Dagestan village of Akusha. After a short battle, the Akushin militia was defeated, and the population of the free Akushin society was sworn to allegiance to the Russian Emperor.

In Dagestan, the highlanders who threatened the Shamkhalate annexed to Tarkov’s empire were pacified.

In 1820, the Black Sea Cossack Army (up to 40 thousand people) was included in the Separate Georgian Corps, renamed the Separate Caucasian Corps and reinforced.

In 1821, the Burnaya fortress was built in the Tarkov Shamkhalate not far from the coast of the Caspian Sea. Moreover, during construction, the troops of the Avar Khan Akhmet, who tried to interfere with the work, were defeated. The possessions of the Dagestan princes, who suffered a series of defeats in 1819-1821, were either transferred to Russian vassals and subordinated to Russian commandants, or liquidated.

On the right flank of the line, the Trans-Kuban Circassians, with the help of the Turks, began to further disturb the border. Their army invaded the lands of the Black Sea Army in October 1821, but was defeated.

In Abkhazia, Major General Prince Gorchakov defeated the rebels near Cape Kodor and brought Prince Dmitry Shervashidze into possession of the country.

To completely pacify Kabarda, in 1822 a series of fortifications were built at the foot of the mountains from Vladikavkaz to the upper reaches of the Kuban. Among other things, the Nalchik fortress was founded (1818 or 1822).

In 1823-1824. A number of punitive expeditions were carried out against the Trans-Kuban Circassians.

In 1824, the Black Sea Abkhazians, who rebelled against the successor of Prince, were forced to submit. Dmitry Shervashidze, book. Mikhail Shervashidze.

In 1825, an uprising began in Chechnya. On July 8, the highlanders captured the Amiradzhiyurt post and tried to take the Gerzel fortification. On July 15, Lieutenant General Lisanevich rescued him. 318 Kumyk-Aksaev elders were gathered in Gerzel-aul. The next day, July 18, Lisanevich and General Grekov were killed by the Kumyk mullah Ochar-Khadzhi (according to other sources, Uchur-mullah or Uchar-Gadzhi) during negotiations with Kumyk elders. Ochar-Khadzhi attacked Lieutenant General Lisanevich with a dagger, and also killed the unarmed General Grekov with a knife in the back. In response to the murder of two generals, the troops killed all the Kumyk elders invited to negotiations.

In 1826, a clearing was cut through the dense forest to the village of Germenchuk, which served as one of the main bases of the Chechens.

The Kuban coast began again to be raided by large parties of Shapsugs and Abadzekhs. The Kabardians became worried. In 1826, a series of campaigns were carried out in Chechnya, with deforestation, clearing, and pacification of villages free from Russian troops. This ended the activities of Ermolov, who was recalled by Nicholas I in 1827 and sent into retirement due to suspicion of connections with the Decembrists.

On January 11, 1827, in Stavropol, a delegation of Balkar princes submitted a petition to General George Emmanuel to accept Balkaria as Russian citizenship.

On March 29, 1827, Nicholas I appointed Adjutant General Ivan Paskevich as commander-in-chief of the Caucasian Corps. At first, he was mainly occupied with wars with Persia and Turkey. Successes in these wars helped maintain external calm.

In 1828, in connection with the construction of the Military-Sukhumi road, the Karachay region was annexed.

The emergence of muridism in Dagestan

In 1823, the Bukharan Khass-Muhammad brought Persian Sufi teachings to the Caucasus, to the village of Yarag (Yaryglar), Kyura Khanate and converted Magomed of Yaragsky to Sufism. He, in turn, began to preach a new teaching in his village. His eloquence attracted students and admirers to him. Even some mullahs began to come to Yarag to hear revelations that were new to them. After some time, Magomed began to send his followers - murids with wooden checkers in their hands and a covenant of deathly silence - to other villages. In a country where a seven-year-old child did not leave home without a dagger on his belt, where a plowman worked with a rifle over his shoulders, unarmed people suddenly appeared alone, who, meeting passers-by, struck the ground three times with wooden sabers and exclaimed with insane solemnity: “ Muslims are crazy! Gazavat! The murids were given only this one word; they answered all other questions with silence. The impression was extraordinary; they were taken for saints protected by fate.

Ermolov, who visited Dagestan in 1824, learned from conversations with the Arakan qadi about the nascent sect and ordered Aslan Khan of Kazi-Kumukh to stop the unrest excited by the followers of the new teaching, but, distracted by other matters, could not monitor the execution of this order, as a result of which Magomed and his murids continued to inflame the minds of the mountaineers and proclaim the proximity of gazavat, a holy war against the infidels.

In 1828, at a meeting of his followers, Magomed announced that his beloved disciple Kazi-Mulla would raise the banner of ghazavat against the infidels and immediately proclaimed him imam. It is interesting that Magomed himself lived for another 10 years after this, but apparently did not participate in political life anymore.

Kazi-Mulla

Kazi-Mulla (Shikh-Ghazi-Khan-Mukhamed) came from the village of Gimry. As a young man, he studied with the famous Arakanese theologian Seid Effendi. However, subsequently he met with the followers of Magomed Yaragsky and switched to a new teaching. He lived with Magomed in Yaraghi for a whole year, after which he declared him imam.

Having received the title of imam and blessing for the war against the infidels from Magomed Yaragsky in 1828, Kazi-Mulla returned to Gimry, but did not immediately begin military operations: the new teaching still had few murids (disciples, followers). Kazi-Mulla began to lead an ascetic lifestyle, praying day and night; He gave sermons in Gimry and neighboring villages. His eloquence and knowledge of theological texts, according to the recollections of the mountaineers, were amazing (the lessons of Seid-Effendi were not in vain). He skillfully hid his true goals: the tariqa does not recognize secular power, and if he had openly declared that after the victory he would abolish all Dagestan khans and shamkhals, then his activities would have immediately come to an end.

Within a year, Gimry and several other villages adopted muridism. The women covered their faces with veils, the men stopped smoking, and all songs fell silent except for “La-illahi-il-Alla.” In other villages he gained fans and the fame of a saint.

Soon the residents of the village of Karanai asked Kazi-Mulla to give them a qadi; he sent one of his students to them. However, having felt all the severity of the rule of Muridism, the Karanaevites kicked out the new qadi. Then Kazi-Mulla approached Karanai with armed Gimrinites. The residents did not dare to shoot at the “holy man” and allowed him to enter the village. Kazi-Mulla punished the residents with sticks and again installed his qadi. This example had a strong impact on the minds of the people: Kazi-Mulla showed that he was no longer only a spiritual mentor, and that having entered his sect, it was no longer possible to go back.

The spread of muridism went even faster. Kazi-Mulla, surrounded by disciples, began to walk around the villages. Crowds of thousands came out to see him. On the way, he often stopped, as if listening to something, and when asked by a student what he was doing, he answered: “I hear the ringing of the chains in which the Russians are being led in front of me.” After this, he for the first time revealed to his listeners the prospects for a future war with the Russians, the capture of Moscow and Istanbul.

By the end of 1829, Kazi-Mulla obeyed Koisub, Humbert, Andia, Chirkey, Salatavia and other small societies of mountainous Dagestan. However, the strong and influential Khanate - Avaria, which swore allegiance to Russia back in September 1828, refused to recognize his power and accept the new teaching.

Kazi-Mullah also encountered resistance among the Muslim clergy. And most of all, the most respected mullah of Dagestan, Said from Arakan, with whom Kazi-Mulla himself once studied, opposed the tariqa. At first, the imam tried to attract the former mentor to his side, offering him the title of supreme qadi, but he refused.

Debir-haji, at that time a student of Kazi-mullah, later Naib of Shamil, who then fled to the Russians, witnessed the last conversation between Said and Kazi-mullah.

Then Kazi-Mulla stood up in great excitement and whispered to me, “Seyid is the same giaur; “He stands across our road and should be killed like a dog.”

“We must not violate the duty of hospitality,” I said: “we’d better wait; he may still come to his senses.

Having failed with the existing clergy, Kazi Mullah decided to create a new clergy from among his murids. This is how “Shikhas” were created, which were supposed to compete with the old mullahs.

At the beginning of January 1830, Kazi Mullah and his murids attacked Arakan in order to deal with his former mentor. The Arakanese, taken by surprise, could not resist. Under the threat of extermination of the village, Kazi Mullah forced all residents to take an oath to live according to Sharia. However, he did not find Said - at that time he was visiting the Kazikumykh Khan. Kazi Mullah ordered the destruction of everything that was found in his house, not excluding the extensive works on which the old man worked all his life.

This act caused condemnation even in those villages that accepted muridism, but Kazi Mullah captured all his opponents and sent them to Gimry, where they were seated in stinking pits. Some Kumyk princes soon followed there. The attempted uprising in Miatlakh ended even more sadly: having arrived there with his murids, Kazi-Mulla himself shot the disobedient qadi at point-blank range. Hostages were taken from the population and taken to Gimry, who should have been responsible for the obedience of their people. It should be noted that this no longer happened in “nobody’s” villages, but in the territories of the Mehtulin Khanate and the Tarkov Shamkhalate.

Next, Kazi-Mulla tried to annex the Akushin (Dargin) society. But the Akusha qadi told the imam that the Dargins already follow Sharia, so his appearance in Akusha was completely unnecessary. The Akushinsky qadi was at the same time the ruler, so Kazi-Mulla did not decide to go to war with the strong Akushinsky society (a society in Russian documents was a group of villages inhabited by one people and without a ruling dynasty), but decided to first conquer Avaria.

But Kazi-Mulla’s plans were not destined to come true: the Avar militia, led by the young Abu Nutsal Khan, despite the inequality of forces, made a sortie and defeated the army of the murids. The Khunzakhs chased them all day, and by evening there was not a single murid left on the Avar Plateau.

After this, the influence of Kazi-Mulla was greatly shaken, and the arrival of new troops sent to the Caucasus after the conclusion of peace with the Ottoman Empire made it possible to allocate a detachment for action against Kazi-Mulla. This detachment, under the command of Baron Rosen, approached the village of Gimry, where the residence of Kazi-Mulla was. However, as soon as the detachment appeared on the heights surrounding the village, the Koisubulins (a group of villages along the Koisu River) sent elders with an expression of humility to take the oath of allegiance to Russia. General Rosen considered the oath sincere and returned with his detachment to the line. Kazi-Mulla attributed the removal of the Russian detachment to help from above, and immediately called on the Koisubulin people not to be afraid of the weapons of the infidels, but to boldly go to Tarki and Sudden and act “as God directs.”

Kazi-Mulla chose the inaccessible Chumkes-Kent tract (not far from Temir-Khan-Shura) as his new location, from where he began to convene all the mountaineers to fight the infidels. His attempts to take the fortresses of Burnaya and Vnezapnaya failed; but General Bekovich-Cherkassky’s movement towards Chumkes-Kent was also unsuccessful: having become convinced that the strongly fortified position was inaccessible, the general did not dare to storm and retreated. The last failure, greatly exaggerated by the mountain messengers, increased the number of adherents of Kazi-Mulla, especially in central Dagestan.

In 1831, Kazi-Mulla took and plundered Tarki and Kizlyar and attempted, but unsuccessfully, to take possession of Derbent with the support of the rebel Tabasarans. Significant territories came under the authority of the imam. However, from the end of 1831 the uprising began to decline. The detachments of Kazi-Mulla were pushed back to Mountainous Dagestan. Attacked on December 1, 1831 by Colonel Miklashevsky, he was forced to leave Chumkes-Kent and again went to Gimry. Appointed in September 1831, the commander of the Caucasian Corps, Baron Rosen, took Gimry on October 17, 1832; Kazi-Mulla died during the battle.

On the southern side of the Caucasus ridge, the Lezgin line of fortifications was created in 1930 to protect Georgia from raids.

Western Caucasus

In the Western Caucasus in August 1830, the Ubykhs and Sadzes, led by Hadji Berzek Dagomuko (Adagua-ipa), launched a desperate assault on the newly erected fort in Gagra. Such fierce resistance forced General Hesse to abandon further advance to the north. Thus, the coastal strip between Gagra and Anapa remained under the control of the Caucasians.

In April 1831, Count Paskevich-Erivansky was recalled to suppress the uprising in Poland. In his place were temporarily appointed: in Transcaucasia - General Pankratiev, on the Caucasian line - General Velyaminov.

On the Black Sea coast, where the highlanders had many convenient points for communication with the Turks and trading in slaves (the Black Sea coastline did not yet exist), foreign agents, especially the British, distributed anti-Russian appeals among the local tribes and delivered military supplies. This forced Baron Rosen to entrust General Velyaminov (in the summer of 1834) with a new expedition to the Trans-Kuban region to establish a cordon line to Gelendzhik. It ended with the construction of fortifications of Abinsky and Nikolaevsky.

Gamzat-bek

After the death of Kazi-Mulla, one of his assistants, Gamzat-bek, proclaimed himself an imam. In 1834, he invaded Avaria, captured Khunzakh, exterminated almost the entire khan’s family, which adhered to a pro-Russian orientation, and was already thinking about the conquest of all of Dagestan, but died at the hands of conspirators who took revenge on him for the murder of the khan’s family. Soon after his death and the proclamation of Shamil as the third imam, on October 18, 1834, the main stronghold of the Murids, the village of Gotsatl, was taken and destroyed by a detachment of Colonel Kluki-von Klugenau. Shamil's troops retreated from Avaria.

Imam Shamil

In the Eastern Caucasus, after the death of Gamzat-bek, Shamil became the head of the murids. The accident became the core of Shamil’s state, and all three imams of Dagestan and Chechnya were from there.

The new imam, who had administrative and military abilities, soon turned out to be an extremely dangerous enemy, uniting under his rule some of the hitherto scattered tribes and villages of the Eastern Caucasus. Already at the beginning of 1835, his forces increased so much that he set out to punish the Khunzakh people for killing his predecessor. Temporarily installed as the ruler of Avaria, Aslan Khan Kazikumukhsky asked to send Russian troops to defend Khunzakh, and Baron Rosen agreed to his request due to the strategic importance of the fortress; but this entailed the need to occupy many other points to ensure communications with Khunzakh through inaccessible mountains. The Temir-Khan-Shura fortress, newly built on the Tarkov plane, was chosen as the main stronghold on the route of communication between Khunzakh and the Caspian coast, and the Nizovoye fortification was built to provide a pier to which ships approached from Astrakhan. The communication between Temir-Khan-Shura and Khunzakh was covered by the Zirani fortification near the Avar Koisu River and the Burunduk-Kale tower. For direct communication between Temir-Khan-Shura and the Vnezapnaya fortress, the Miatlinskaya crossing over Sulak was built and covered with towers; the road from Temir-Khan-Shura to Kizlyar was secured by the fortification of Kazi-Yurt.

Shamil, more and more consolidating his power, chose the Koisubu district as his residence, where on the banks of the Andean Koisu he began to build a fortification, which he called Akhulgo. In 1837, General Fezi occupied Khunzakh, took the village of Ashilty and the fortification of Old Akhulgo and besieged the village of Tilitl, where Shamil had taken refuge. When Russian troops captured part of this village on July 3, Shamil entered into negotiations and promised submission. I had to accept his offer, since the Russian detachment, which had suffered heavy losses, was severely short of food and, in addition, news was received of an uprising in Cuba.

In the Western Caucasus, a detachment of General Velyaminov in the summer of 1837 penetrated to the mouths of the Pshada and Vulana rivers and founded the Novotroitskoye and Mikhailovskoye fortifications there.

Meeting between General Klugi von Klugenau and Shamil in 1837 (Grigory Gagarin)

In September of the same 1837, Emperor Nicholas I visited the Caucasus for the first time and was dissatisfied with the fact that, despite many years of efforts and major sacrifices, Russian troops were still far from lasting results in pacifying the region. General Golovin was appointed to replace Baron Rosen.

In 1838, on the Black Sea coast, fortifications of Navaginskoye, Velyaminovskoye and Tenginskoye were built and construction of the Novorossiysk fortress with a military harbor began.

In 1839, operations were carried out in various areas by three detachments. The landing detachment of General Raevsky erected new fortifications on the Black Sea coast (forts Golovinsky, Lazarev, Raevsky). The Dagestan detachment, under the command of the corps commander himself, captured a very strong position of the highlanders on the Adzhiakhur heights on May 31, and on June 3 occupied the village. Akhty, near which a fortification was erected. The third detachment, Chechen, under the command of General Grabbe, moved against the main forces of Shamil, fortified near the village. Argvani, on the descent to the Andian Kois. Despite the strength of this position, Grabbe took possession of it, and Shamil with several hundred murids took refuge in Akhulgo, which he had renewed. Akhulgo fell on August 22, but Shamil himself managed to escape. The highlanders, showing apparent submission, were in fact preparing another uprising, which over the next 3 years kept the Russian forces in the most tense state.

Meanwhile, Shamil, after the defeat in Akhulgo, with a detachment of seven comrades-in-arms, arrived in Chechnya, where, from the end of February 1840, there was a general uprising under the leadership of Shoaip Mullah Tsentaroyevsky, Javad Khan Darginsky, Tashev-Khadzhi Sayasanovsky and Isa Gendergenoevsky. After a meeting with the Chechen leaders Isa Gendergenoevsky and Akhberdil-Mukhammed in Urus-Martan, Shamil was proclaimed Imam of Chechnya (March 7, 1840). Dargo became the capital of the Imamate.

Meanwhile, hostilities began on the Black Sea coast, where the hastily built Russian forts were in a dilapidated state, and the garrisons were extremely weakened by fevers and other diseases. On February 7, 1840, the highlanders captured Fort Lazarev and destroyed all its defenders; On February 29, the same fate befell the Velyaminovskoye fortification; On March 23, after a fierce battle, the highlanders penetrated the Mikhailovskoye fortification, the defenders of which blew themselves up. In addition, the highlanders captured (April 1) the Nikolaev fort; but their enterprises against the Navaginsky fort and the Abinsky fortification were unsuccessful.

On the left flank, the premature attempt to disarm the Chechens caused extreme anger among them. In December 1839 and January 1840, General Pullo conducted punitive expeditions in Chechnya and destroyed several villages. During the second expedition, the Russian command demanded the surrender of one gun from 10 houses, as well as one hostage from each village. Taking advantage of the discontent of the population, Shamil raised the Ichkerians, Aukhovites and other Chechen societies against the Russian troops. Russian troops under the command of General Galafeev limited themselves to searching in the forests of Chechnya, which cost many people. It was especially bloody on the river. Valerik (July 11). While General Galafeev was walking around Lesser Chechnya, Shamil with Chechen troops subjugated Salatavia to his power and in early August invaded Avaria, where he conquered several villages. With the addition of the elder of the mountain societies in the Andean Koisu, the famous Kibit-Magoma, his strength and enterprise increased enormously. By the fall, all of Chechnya was already on Shamil’s side, and the means of the Caucasian line turned out to be insufficient to successfully fight him. The Chechens began to attack the tsarist troops on the banks of the Terek and almost captured Mozdok.

On the right flank, by the fall, a new fortified line along the Labe was secured by forts Zassovsky, Makhoshevsky and Temirgoevsky. The Velyaminovskoye and Lazarevskoye fortifications were restored on the Black Sea coastline.

In 1841, riots broke out in Avaria, instigated by Hadji Murad. A battalion with 2 mountain guns was sent to pacify them, under the command of General. Bakunin, failed at the village of Tselmes, and Colonel Passek, who took command after the mortally wounded Bakunin, only with difficulty managed to withdraw the remnants of the detachment to Khunza. The Chechens raided the Georgian Military Road and stormed the military settlement of Aleksandrovskoye, and Shamil himself approached Nazran and attacked the detachment of Colonel Nesterov located there, but had no success and took refuge in the forests of Chechnya. On May 15, generals Golovin and Grabbe attacked and took the position of the imam near the village of Chirkey, after which the village itself was occupied and the Evgenievskoye fortification was founded near it. Nevertheless, Shamil managed to extend his power to the mountain societies of the right bank of the river. Avar Koisu, the murids again captured the village of Gergebil, which blocked the entrance to Mekhtulin’s possessions; Communications between Russian forces and Avaria were temporarily interrupted.

In the spring of 1842, the expedition of General. Fezi somewhat improved the situation in Avaria and Koisubu. Shamil tried to agitate Southern Dagestan, but to no avail. Thus, the entire territory of Dagestan was never annexed to the Imamat.

Shamil's army

Under Shamil, a semblance of a regular army was created - Murtazeki(cavalry) and at the bottom(infantry). In normal times, the number of Imamat troops was up to 15 thousand people, the maximum number in a total assembly was 40 thousand. The Imamat artillery consisted of 50 guns, most of which were captured (Over time, the highlanders created their own factories for the production of guns and shells, however, inferior to European and Russian products).

According to the data of the Chechen Naib Shamil Yusuf Haji Safarov, the army of the Imamat consisted of Avar and Chechen militias. The Avars provided Shamil with 10,480 soldiers, who made up 71.10% of the total army. Chechens numbered 28.90%, with a total number of 4270 soldiers.

Battle of Ichkera (1842)

In May 1842, 4,777 Chechen soldiers with Imam Shamil went on a campaign against Kazi-Kumukh in Dagestan. Taking advantage of their absence, on May 30, Adjutant General P.H. Grabbe with 12 infantry battalions, a company of sappers, 350 Cossacks and 24 cannons set out from the Gerzel-aul fortress towards the capital of the Imamat, Dargo. The ten-thousand-strong royal detachment was opposed, according to A. Zisserman, “according to the most generous estimates, up to one and a half thousand” Ichkerin and Aukhov Chechens.

Led by Shoaip-Mullah Tsentaroevsky, the mountaineers were preparing for battle. Naibs Baysungur and Soltamurad organized the Benoevites to build rubble, ambushes, pits, and prepare provisions, clothing and military equipment. Shoaip instructed the Andians guarding the capital of Shamil Dargo to destroy the capital when the enemy approached and take all the people to the mountains of Dagestan. The Naib of Greater Chechnya, Javatkhan, who was seriously wounded in one of the recent battles, was replaced by his assistant Suaib-Mullah Ersenoevsky. The Aukhov Chechens were led by the young Naib Ulubiy-Mullah.

Stopped by fierce resistance from the Chechens at the villages of Belgata and Gordali, on the night of June 2, Grabbe’s detachment began to retreat. The tsarist troops lost 66 officers and 1,700 soldiers killed and wounded in the battle. The mountaineers lost up to 600 people killed and wounded. 2 cannons and almost all the military and food supplies of the tsarist troops were captured.

On June 3, Shamil, having learned about the Russian movement towards Dargo, turned back to Ichkeria. But by the time the imam arrived, everything was already over.

The unfortunate outcome of this expedition greatly raised the spirit of the rebels, and Shamil began to recruit troops, intending to invade Avaria. Grabbe, having learned about this, moved there with a new, strong detachment and captured the village of Igali in battle, but then withdrew from Avaria, where only the Russian garrison remained in Khunzakh. The overall result of the actions of 1842 was unsatisfactory, and already in October Adjutant General Neidgardt was appointed to replace Golovin.

The failures of the Russian troops spread in the highest government spheres the conviction that offensive actions were futile and even harmful. This opinion was especially supported by the then Minister of War, Prince. Chernyshev, who visited the Caucasus in the summer of 1842 and witnessed the return of Grabbe’s detachment from the Ichkerin forests. Impressed by this catastrophe, he convinced the tsar to sign a decree prohibiting all expeditions for 1843 and ordering them to limit themselves to defense.

This forced inaction of the Russian troops emboldened the enemy, and attacks on the line became more frequent again. On August 31, 1843, Imam Shamil captured the fort at the village. Untsukul, destroying the detachment that was going to the rescue of the besieged. In the following days, several more fortifications fell, and on September 11, Gotsatl was taken, which interrupted communication with Temir Khan-Shura. From August 28 to September 21, the losses of Russian troops amounted to 55 officers, more than 1,500 lower ranks, 12 guns and significant warehouses: the fruits of many years of effort were lost, long-submissive mountain societies were cut off from Russian forces and the morale of the troops was undermined. On October 28, Shamil surrounded the Gergebil fortification, which he managed to take only on November 8, when only 50 of the defenders remained alive. Detachments of mountaineers, scattering in all directions, interrupted almost all communications with Derbent, Kizlyar and the left flank of the line; Russian troops in Temir Khan-Shura withstood the blockade, which lasted from November 8 to December 24.

In mid-April 1844, Shamil’s Dagestani troops, led by Hadji Murad and Naib Kibit-Magom, approached Kumykh, but on the 22nd they were completely defeated by Prince Argutinsky, near the village. Margi. Around this time, Shamil himself was defeated near the village of Andreevo, where Colonel Kozlovsky’s detachment met him, and near the village of Gilli the Dagestan highlanders were defeated by Passek’s detachment. On the Lezgin line, the Elisu Khan Daniel Bek, who had been loyal to Russia until then, was indignant. A detachment of General Schwartz was sent against him, who scattered the rebels and captured the village of Ilisu, but the khan himself managed to escape. The actions of the main Russian forces were quite successful and ended with the capture of the Dargin district in Dagestan (Akusha, Khadzhalmakhi, Tsudahar); then the construction of the advanced Chechen line began, the first link of which was the Vozdvizhenskoye fortification, on the river. Argun. On the right flank, the highlanders' assault on the Golovinskoye fortification was brilliantly repulsed on the night of July 16.

At the end of 1844, a new commander-in-chief, Count Vorontsov, was appointed to the Caucasus.

Dargin campaign (Chechnya, May 1845)

In May 1845, the tsarist army invaded the Imamate in several large detachments. At the beginning of the campaign, 5 detachments were created for actions in different directions. Chechensky was led by General Liders, Dagestansky by Prince Beibutov, Samursky by Argutinsky-Dolgorukov, Lezginsky by General Schwartz, Nazranovsky by General Nesterov. The main forces moving towards the capital of the Imamate were headed by the commander-in-chief of the Russian army in the Caucasus, Count M. S. Vorontsov.

Without encountering serious resistance, the 30,000-strong detachment passed through mountainous Dagestan and on June 13 invaded Andia. At the time of leaving Andia for Dargo, the total strength of the detachment was 7940 infantry, 1218 cavalry and 342 artillerymen. The Battle of Dargin lasted from July 8 to July 20. According to official data, in the Battle of Dargin, the tsarist troops lost 4 generals, 168 officers and up to 4,000 soldiers.

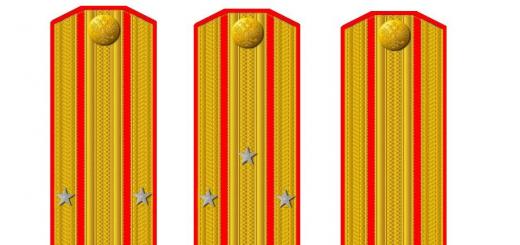

Many future famous military leaders and politicians took part in the campaign of 1845: governor in the Caucasus in 1856-1862. and Field Marshal Prince A.I. Baryatinsky; Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasian Military District and chief commander of the civilian unit in the Caucasus in 1882-1890. Prince A. M. Dondukov-Korsakov; acting as commander-in-chief in 1854 before the arrival of Count N.N. Muravyov to the Caucasus, Prince V.O. Bebutov; famous Caucasian military general, chief of the General Staff in 1866-1875. Count F. L. Heyden; military governor, killed in Kutaisi in 1861, Prince A.I. Gagarin; commander of the Shirvan regiment, Prince S. I. Vasilchikov; adjutant general, diplomat in 1849, 1853-1855, Count K. K. Benckendorff (seriously wounded in the campaign of 1845); Major General E. von Schwarzenberg; Lieutenant General Baron N.I. Delvig; N.P. Beklemishev, an excellent draftsman who left many sketches after his trip to Dargo, also known for his witticisms and puns; Prince E. Wittgenstein; Prince Alexander of Hesse, Major General, and others.

On the Black Sea coastline in the summer of 1845, the highlanders attempted to capture forts Raevsky (May 24) and Golovinsky (July 1), but were repulsed.

Since 1846, actions were carried out on the left flank aimed at strengthening control over the occupied lands, erecting new fortifications and Cossack villages and preparing further movement deep into the Chechen forests by cutting down wide clearings. Victory of the book Bebutov, who wrested from the hands of Shamil the inaccessible village of Kutish, which he had just occupied (currently included in the Levashinsky district of Dagestan), resulted in a complete calming of the Kumyk plane and the foothills.

On the Black Sea coastline, the Ubykhs, numbering up to 6 thousand people, launched a new desperate attack on the Golovinsky fort on November 28, but were repulsed with great damage.

In 1847, Prince Vorontsov besieged Gergebil, but due to the spread of cholera among the troops, he had to retreat. At the end of July, he undertook a siege of the fortified village of Salta, which, despite the significant siege weapons of the advancing troops, held out until September 14, when it was cleared by the highlanders. Both of these enterprises cost the Russian troops about 150 officers and more than 2,500 lower ranks who were out of action.

The troops of Daniel Bek invaded the Jaro-Belokan district, but on May 13 they were completely defeated at the village of Chardakhly.

In mid-November, Dagestan mountaineers invaded Kazikumukh and briefly captured several villages.

In 1848, an outstanding event was the capture of Gergebil (July 7) by Prince Argutinsky. In general, for a long time there has not been such calm in the Caucasus as this year; Only on the Lezgin line were frequent alarms repeated. In September, Shamil tried to capture the Akhta fortification on Samur, but he failed.

In 1849, the siege of the village of Chokha, undertaken by Prince. Argutinsky, cost the Russian troops great losses, but was not successful. From the Lezgin line, General Chilyaev carried out a successful expedition into the mountains, which ended in the defeat of the enemy near the village of Khupro.

In 1850, systematic deforestation in Chechnya continued with the same persistence and was accompanied by more or less serious clashes. This course of action forced many hostile societies to declare their unconditional submission.

It was decided to adhere to the same system in 1851. On the right flank, an offensive was launched to the Belaya River in order to move the front line there and take away the fertile lands between this river and Laba from the hostile Abadzekhs; in addition, the offensive in this direction was caused by the appearance in the Western Caucasus of Naib Shamil, Mohammed-Amin, who collected large parties for raids on Russian settlements near Labino, but was defeated on May 14.

1852 was marked by brilliant actions in Chechnya under the leadership of the commander of the left flank, Prince. Baryatinsky, who penetrated hitherto inaccessible forest shelters and destroyed many hostile villages. These successes were overshadowed only by the unsuccessful expedition of Colonel Baklanov to the village of Gordali.

In 1853, rumors of an impending break with Turkey aroused new hopes among the mountaineers. Shamil and Mohammed-Amin, the Naib of Circassia and Kabardia, having gathered the mountain elders, announced to them the firmans received from the Sultan, commanding all Muslims to rebel against the common enemy; they talked about the imminent arrival of Turkish troops in Balkaria, Georgia and Kabarda and about the need to act decisively against the Russians, who were allegedly weakened by the sending of most of their military forces to the Turkish borders. However, the spirit of the mass of the mountaineers had already fallen so low due to a series of failures and extreme impoverishment that Shamil could only subjugate them to his will through cruel punishments. The raid he planned on the Lezgin line ended in complete failure, and Mohammed-Amin with a detachment of Trans-Kuban highlanders was defeated by a detachment of General Kozlovsky.

With the beginning of the Crimean War, the command of the Russian troops decided to maintain a predominantly defensive course of action at all points in the Caucasus; however, the clearing of forests and the destruction of the enemy's food supplies continued, although to a more limited extent.

In 1854, the head of the Turkish Anatolian Army entered into negotiations with Shamil, inviting him to move to join him from Dagestan. At the end of June, Shamil and the Dagestan highlanders invaded Kakheti; The mountaineers managed to ravage the rich village of Tsinondal, capture the family of its ruler and plunder several churches, but upon learning of the approach of Russian troops, they retreated. Shamil's attempt to take possession of the peaceful village of Istisu was unsuccessful. On the right flank, the space between Anapa, Novorossiysk and the mouths of the Kuban was abandoned by Russian troops; The garrisons of the Black Sea coastline were taken to Crimea at the beginning of the year, and forts and other buildings were blown up. Book Vorontsov left the Caucasus back in March 1854, transferring control to the general. Read, and at the beginning of 1855, General was appointed commander-in-chief in the Caucasus. Muravyov. The landing of the Turks in Abkhazia, despite the betrayal of its ruler, Prince. Shervashidze, had no harmful consequences for Russia. At the conclusion of the Peace of Paris, in the spring of 1856, it was decided to use the troops operating in Asian Turkey and, strengthening the Caucasian Corps with them, to begin the final conquest of the Caucasus.

Baryatinsky

The new commander-in-chief, Prince Baryatinsky, turned his main attention to Chechnya, the conquest of which he entrusted to the head of the left wing of the line, General Evdokimov, an old and experienced Caucasian; but in other parts of the Caucasus the troops did not remain inactive. In 1856 and 1857 Russian troops achieved the following results: the Adagum Valley was occupied on the right wing of the line and the Maykop fortification was built. On the left wing, the so-called “Russian road”, from Vladikavkaz, parallel to the ridge of the Black Mountains, to the fortification of Kurinsky on the Kumyk plane, is completely completed and strengthened by newly constructed fortifications; wide clearings have been cut in all directions; the mass of the hostile population of Chechnya has been driven to the point of having to submit and move to open areas, under state supervision; The Aukh district is occupied and a fortification has been erected in its center. In Dagestan, Salatavia is finally occupied. Several new Cossack villages were established along Laba, Urup and Sunzha. The troops are everywhere close to the front lines; the rear is secured; vast expanses of the best lands are cut off from the hostile population and, thus, a significant share of the resources for the fight are wrested from the hands of Shamil.

On the Lezgin line, as a result of deforestation, predatory raids gave way to petty theft. On the Black Sea coast, the secondary occupation of Gagra marked the beginning of securing Abkhazia from incursions by Circassian tribes and from hostile propaganda. The actions of 1858 in Chechnya began with the occupation of the Argun River gorge, which was considered impregnable, where Evdokimov ordered the construction of a strong fortification, called Argunsky. Climbing up the river, he reached, at the end of July, the villages of the Shatoevsky society; in the upper reaches of the Argun he founded a new fortification - Evdokimovskoye. Shamil tried to divert attention by sabotage to Nazran, but was defeated by the detachment of General Mishchenko and barely managed to get out of the battle without being ambushed (due to the large number of tsarist troops), but avoided this thanks to Naib Beta Achkhoevsky who managed to help him, who broke through the encirclement and go to the still unoccupied part of the Argun Gorge. Convinced that his power there had been completely undermined, he retired to Vedeno, his new residence. On March 17, 1859, the bombardment of this fortified village began, and on April 1 it was taken by storm.

Shamil went beyond the Andean Koisu. After the capture of Veden, three detachments headed concentrically to the Andean Koisu valley: Dagestan, Chechen (former naibs and wars of Shamil) and Lezgin. Shamil, who temporarily settled in the village of Karata, fortified Mount Kilitl, and covered the right bank of the Andean Koisu, opposite Conkhidatl, with solid stone rubble, entrusting their defense to his son Kazi-Magoma. With any energetic resistance from the latter, forcing the crossing at this point would cost enormous sacrifices; but he was forced to leave his strong position as a result of the troops of the Dagestan detachment entering his flank, who made a remarkably courageous crossing across the Andiyskoe Koisu at the Sagytlo tract. Seeing the danger threatening from everywhere, the imam went to Mount Gunib, where Shamil with 500 murids fortified himself as in the last and impregnable refuge. On August 25, Gunib was taken by storm, forced by the fact that 8,000 troops were standing all around on all the hills, in all the ravines, Shamil himself surrendered to Prince Baryatinsky.

Completion of the conquest of Circassia (1859-1864)

The capture of Gunib and the capture of Shamil could be considered the last act of the war in the Eastern Caucasus; but Western Circassia, which occupied the entire western part of the Caucasus, adjacent to the Black Sea, had not yet been conquered. It was decided to conduct the final stage of the war in Western Circassia in this way: the Circassians had to submit and move to the places indicated to them on the plain; otherwise, they were pushed further into the barren mountains, and the lands they left behind were populated by Cossack villages; finally, after pushing the mountaineers back from the mountains to the seashore, they could either move to the plain, under the supervision of the Russians, or move to Turkey, in which it was supposed to provide them with possible assistance. In 1861, on the initiative of the Ubykhs, the Circassian parliament “Great and Free Session” was created in Sochi. The Ubykhs, Shapsugs, Abadzekhs, and Dzhigets (Sadzys) sought to unite the Circassians “into one huge wave.” A special parliamentary delegation headed by Ismail Barakai Dziash visited a number of European countries. Actions against the small armed formations there dragged on until the end of 1861, when all attempts at resistance were finally suppressed. Only then was it possible to begin decisive operations on the right wing, the leadership of which was entrusted to the conqueror of Chechnya, Evdokimov. His troops were divided into 2 detachments: one, Adagumsky, acted in the land of the Shapsugs, the other - from the Laba and Belaya; a special detachment was sent to operate in the lower reaches of the river. Pshish. In autumn and winter, Cossack villages are established in the Natukhai district. The troops operating from the direction of Laba completed the construction of villages between Laba and Belaya and cut through the entire foothill space between these rivers with clearings, which forced the local communities to partly move to the plane, partly to go beyond the pass of the Main Range.

At the end of February 1862, Evdokimov’s detachment moved to the river. Pshekha, to which, despite the stubborn resistance of the Abadzekhs, a clearing was cut and a convenient road was laid. Everyone living between the Khodz and Belaya rivers was ordered to immediately move to Kuban or Laba, and within 20 days (from March 8 to March 29) up to 90 villages were resettled. At the end of April, Evdokimov, having crossed the Black Mountains, descended into the Dakhovskaya Valley along a road that the mountaineers considered inaccessible to the Russians, and set up a new Cossack village there, closing the Belorechenskaya line. The movement of the Russians deep into the Trans-Kuban region was met everywhere by desperate resistance from the Abadzekhs, supported by the Ubykhs and the Abkhaz tribes of the Sadz (Dzhigets) and Akhchipshu, which, however, were not crowned with serious successes. The result of the summer and autumn actions of 1862 on the part of Belaya was the strong establishment of Russian troops in the space limited to the west by pp. Pshish, Pshekha and Kurdzhips.

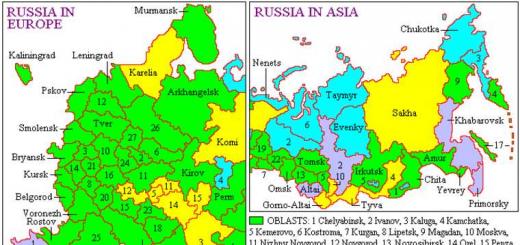

Map of the Caucasus region (1801-1813). Compiled in the military historical department at the headquarters of the Caucasian Military District by Lieutenant Colonel V.I. Tomkeev. Tiflis, 1901. (The name “lands of mountain peoples” refers to the lands of the Western Circassians [Circassians]).

At the beginning of 1863, the only opponents of Russian rule throughout the Caucasus were the mountain societies on the northern slope of the Main Range, from Adagum to Belaya, and the tribes of the coastal Shapsugs, Ubykhs, etc., who lived in the narrow space between the sea coast, the southern slope of the Main Range, and the valley Aderba and Abkhazia. The final conquest of the Caucasus was led by Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, appointed governor of the Caucasus. In 1863, the actions of the troops of the Kuban region. should have consisted of spreading Russian colonization of the region simultaneously from two sides, relying on the Belorechensk and Adagum lines. These actions were so successful that they put the mountaineers of the northwestern Caucasus in a hopeless situation. Already from mid-summer 1863, many of them began to move to Turkey or to the southern slope of the ridge; most of them submitted, so that by the end of summer the number of immigrants settled on the plane in the Kuban and Laba reached 30 thousand people. At the beginning of October, the Abadzekh elders came to Evdokimov and signed an agreement according to which all their fellow tribesmen who wanted to accept Russian citizenship pledged no later than February 1, 1864 to begin moving to the places indicated by him; the rest were given 2 1/2 months to move to Turkey.

The conquest of the northern slope of the ridge was completed. All that remained was to move to the southwestern slope in order to, going down to the sea, clear the coastal strip and prepare it for settlement. On October 10, Russian troops climbed to the very pass and in the same month occupied the river gorge. Pshada and the mouth of the river. Dzhubgi. In the western Caucasus, the remnants of the Circassians of the northern slope continued to move to Turkey or the Kuban Plain. From the end of February, actions began on the southern slope, which ended in May. The masses of Circassians were pushed to the seashore and were transported to Turkey by arriving Turkish ships. On May 21, 1864, in the mountain village of Kbaade, in the camp of united Russian columns, in the presence of the Grand Duke Commander-in-Chief, a thanksgiving prayer service was served on the occasion of the victory.

Memory

May 21 is the day of remembrance of the Circassians (Circassians) - victims of the Caucasian War, established in 1992 by the Supreme Council of the KBSSR and is a non-working day.

In March 1994, in Karachay-Cherkessia, by a resolution of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers of Karachay-Cherkessia, the republic established the “Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Caucasian War,” which is celebrated on May 21.

Consequences

Russia, at the cost of significant bloodshed, was able to suppress the armed resistance of the highlanders, as a result of which hundreds of thousands of highlanders who did not accept Russian power were forced to leave their homes and move to Turkey and the Middle East. As a result, a significant diaspora of immigrants from the North Caucasus has formed there. Most of them are Adyghe-Circassians, Abazins and Abkhazians by origin. Most of these peoples were forced to leave the territory of the North Caucasus.

A fragile peace was established in the Caucasus, which was facilitated by the consolidation of Russia in Transcaucasia and the weakening of the opportunities for Muslims of the Caucasus to receive financial and armed support from their coreligionists. Calm in the North Caucasus was ensured by the presence of a well-organized, trained and armed Cossack army.

Despite the fact that, according to historian A. S. Orlov, “The North Caucasus, like Transcaucasia, was not turned into a colony of the Russian Empire, but became part of it on equal rights with other peoples”, one of the consequences of the Caucasian War was Russophobia, which became widespread among the peoples of the Caucasus. In the 1990s, the Caucasian War was also used by Wahhabi ideologists as a powerful argument in the fight against Russia.

About the Caucasian War in brief

Kavkazskaya vojna (1817—1864)

The Caucasian War began

Caucasian War causes

Caucasian War stages

Caucasian War results

The Caucasian War, in short, is a period of prolonged military conflict between the Russian Empire and the North Caucasian Imamate. The war was fought for the complete subjugation of the mountainous regions of the North Caucasus, and is one of the most fierce in the 19th century. Covers the period from 1817 to 1864.

Close relations between Russia and the peoples of the Caucasus began after the collapse of Georgia in the 15th century. Since the 16th century, many oppressed states of the Caucasus range asked for protection from Russia.

The main reason for the Caucasian War, in short, was that Georgia, the only Christian state in the Caucasus, was constantly under attack and attempts to subjugate it from neighboring Muslim countries. Repeatedly, the rulers of Georgia asked for Russian protection. In 1801, Georgia formally became part of the Russian Empire, but was isolated from it by neighboring countries. There was a need to create the integrity of Russian territory. This was possible only with the subjugation of other peoples of the North Caucasus.

Some states became part of Russia almost voluntarily - Kabarda and Ossetia. The rest - Adygea, Chechnya and Dagestan - categorically refused to do this and put up fierce resistance.

In 1817, the main stage of the conquest of the North Caucasus by Russian troops began under the leadership of General A.P. Ermolova. It was after his appointment as commander of the army in the North Caucasus that the Caucasian War began. Until this time, the Russian authorities were rather lenient towards the mountaineers.

The difficulty of conducting military operations in the Caucasus was that at the same time the Russian Empire had to participate in the Russian-Turkish and Russian-Iranian war.

The second stage of the Caucasian War is associated with the emergence of a single leader in Chechnya and Dagestan - Imam Shamil. He managed to unite disparate peoples and start a “gazavat” - a liberation war - against the Russian troops. Shamil was able to quickly create a strong army and for 30 years waged successful military operations with Russian troops, who suffered huge losses in this war.

In 1817-1827, the commander of the Separate Caucasian Corps and the chief administrator in Georgia was General Alexei Petrovich Ermolov (1777-1861). Ermolov’s activities as commander-in-chief were active and quite successful. In 1817, the construction of the Sunzha line of cordons (along the Sunzha River) began. In 1818, the fortresses of Groznaya (modern Grozny) and Nalchik were built on the Sunzhenskaya line. The campaigns of the Chechens (1819-1821) with the aim of destroying the Sunzhenskaya line were repulsed, Russian troops began advancing into the mountainous regions of Chechnya. In 1827, Ermolov was dismissed from his post for patronizing the Decembrists. Field Marshal General Ivan Fedorovich Paskevich (1782-1856) was appointed to the post of Commander-in-Chief, who switched to the tactics of raids and campaigns, which could not always give lasting results. Later, in 1844, the commander-in-chief and governor, Prince M.S. Vorontsov (1782-1856), was forced to return to the cordon system. In 1834-1859, the liberation struggle of the Caucasian highlanders, which took place under the flag of Gazavat, was led by Shamil (1797 - 1871), who created a Muslim theocratic state - the imamate. Shamil was born in the village of Gimrakh around 1797, and according to other sources around 1799, from the Avar bridle Dengau Mohammed. Gifted with brilliant natural abilities, he listened to the best teachers of grammar, logic and rhetoric of the Arabic language in Dagestan and soon began to be considered an outstanding scientist. The sermons of Kazi Mullah (or rather Gazi-Mohammed), the first preacher of ghazavat - the holy war against the Russians, captivated Shamil, who first became his student, and then his friend and ardent supporter. The followers of the new teaching, which sought salvation of the soul and cleansing from sins through a holy war for faith against the Russians, were called murids. When the people were sufficiently fanaticized and excited by descriptions of paradise, with its houris, and the promise of complete independence from any authorities other than Allah and his Sharia (spiritual law set out in the Koran), Kazi Mullah managed to to carry along Koisuba, Gumbet, Andiya and other small societies of the Avar and Andian Kois, most of the Shamkhaldom of Tarkovsky, the Kumyks and Avaria, except for its capital Khunzakh, where the Avar khans visited. Counting that his power would only be strong in Dagestan when he finally captured Avaria, the center of Dagestan, and its capital Khunzakh, Kazi Mullah gathered 6,000 people and on February 4, 1830 went with them against Khansha Pahu-Bike. On February 12, 1830, he moved to storm Khunzakh, with one half of the militia commanded by Gamzat-bek, his future successor imam, and the other by Shamil, the future 3rd imam of Dagestan.

The assault was unsuccessful; Shamil, together with Kazi Mullah, returned to Nimry. Accompanying his teacher on his campaigns, Shamil in 1832 was besieged by the Russians, under the command of Baron Rosen, in Gimry. Shamil managed, although terribly wounded, to break through and escape, while Kazi Mullah died, stabbed all over with bayonets. The death of the latter, the wounds received by Shamil during the siege of Gimr, and the dominance of Gamzat-bek, who declared himself the successor of Kazi-mullah and imam - all this kept Shamil in the background until the death of Gamzat-bek (September 7 or 19, 1834), the main of which he was a collaborator, raising troops, obtaining material resources and commanding expeditions against the Russians and the enemies of the Imam. Having learned about the death of Gamzat-bek, Shamil gathered a party of the most desperate murids, rushed with them to New Gotsatl, seized the wealth looted by Gamzat there and ordered to kill the surviving youngest son of Paru-Bike, the only heir of the Avar Khanate. With this murder, Shamil finally removed the last obstacle to the spread of the imam's power, since the khans of Avaria were interested in ensuring that there was no single strong government in Dagestan and therefore acted in alliance with the Russians against Kazi-mullah and Gamzat-bek. For 25 years, Shamil ruled over the highlanders of Dagestan and Chechnya, successfully fighting against the enormous forces of Russia. Less religious than Kazi Mullah, less hasty and reckless than Gamzat-bek, Shamil had military talent, great organizational abilities, endurance, perseverance, the ability to choose the time to strike and assistants to fulfill his plans. Distinguished by his strong and unyielding will, he knew how to inspire the mountaineers, knew how to excite them to self-sacrifice and obedience to his power, which was especially difficult and unusual for them.

Superior to his predecessors in intelligence, he, like them, did not understand the means to achieve his goals. Fear for the future forced the Avars to get closer to the Russians: the Avar foreman Khalil-bek came to Temir-Khan-Shura and asked Colonel Kluki von Klugenau to appoint a legal ruler to Avaria so that it would not fall into the hands of the murids. Klugenau moved towards Gotsatl. Shamil, having created blockages on the left bank of the Avar Koisu, intended to act against the Russians in the flank and rear, but Klugenau managed to cross the river, and Shamil had to retreat into Dagestan, where at that time hostile clashes occurred between contenders for power. Shamil's position in these first years was very difficult: a series of defeats suffered by the mountaineers shook their desire for ghazavat and faith in the triumph of Islam over the infidels; one after another, free societies expressed their submission and handed over hostages; Fearing ruin by the Russians, the mountain villages were reluctant to host murids. Throughout 1835, Shamil worked in secret, recruiting followers, fanatizing the crowd and pushing aside rivals or making peace with them. The Russians allowed him to strengthen, because they looked at him as an insignificant adventurer. Shamil spread the rumor that he was working only to restore the purity of Muslim law between the rebellious societies of Dagestan and expressed his readiness to submit to the Russian government with all the Khoisu-Bulin people if he was assigned special content. Thus putting the Russians to sleep, who at that time were especially busy building fortifications along the Black Sea coast in order to cut off the Circassians’ opportunity to communicate with the Turks, Shamil, with the assistance of Tashav-haji, tried to rouse the Chechens and assure them that most of the mountainous Dagestan had already accepted Sharia ( Arabic sharia literally - the proper path) and submitted to the imam. In April 1836, Shamil, with a party of 2 thousand people, with exhortations and threats forced the Khoisu-Bulin people and other neighboring societies to accept his teachings and recognize him as an imam. The commander of the Caucasian corps, Baron Rosen, wishing to undermine the growing influence of Shamil, in July 1836, sent Major General Reut to occupy Untsukul and, if possible, Ashilta, Shamil’s place of residence. Having occupied Irganay, Major General Reut was met with statements of submission from Untsukul, whose elders explained that they accepted Sharia only by yielding to the power of Shamil. Reut did not go to Untsukul after that and returned to Temir-Khan-Shura, and Shamil began to spread the rumor everywhere that the Russians were afraid to go deep into the mountains; then, taking advantage of their inaction, he continued to subjugate the Avar villages to his power. To gain greater influence among the population of Avaria, Shamil married the widow of the former imam Gamzat-bek and at the end of this year achieved that all free Dagestan societies from Chechnya to Avaria, as well as a significant part of the Avars and societies lying south of Avaria, recognized him power.

At the beginning of 1837, the corps commander instructed Major General Feza to undertake several expeditions to different parts of Chechnya, which was carried out with success, but made an insignificant impression on the highlanders. Shamil's continuous attacks on Avar villages forced the governor of the Avar Khanate, Akhmet Khan Mehtulinsky, to offer the Russians to occupy the capital of the Khanate, Khunzakh. On May 28, 1837, General Feze entered Khunzakh and then moved to the village of Ashilte, near which, on the inaccessible cliff Akhulga, the family and all the property of the imam were located. Shamil himself, with a large party, was in the village of Talitle and tried to divert the attention of the troops from Ashilta, attacking from different sides. A detachment under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Buchkiev was sent against him. Shamil tried to break through this barrier and on the night of June 7-8 attacked Buchkiev’s detachment, but after a hot battle he was forced to retreat. On June 9, Ashilta was taken by storm and burned after a desperate battle with 2 thousand selected fanatical murids, who defended every hut, every street, and then rushed at our troops six times to recapture Ashilta, but in vain. On June 12, Akhulgo was also taken by storm. On July 5, General Feze moved troops to attack Tilitla; all the horrors of the Ashiltip pogrom were repeated, when some did not ask and others did not give mercy. Shamil saw that the matter was lost and sent the envoy with an expression of humility. General Feze gave in to the deception and entered into negotiations, after which Shamil and his comrades handed over three amanats (hostages), including Shamil’s nephew, and swore allegiance to the Russian emperor. Having missed the opportunity to take Shamil prisoner, General Feze dragged out the war for 22 years, and by concluding peace with him as an equal party, he raised his importance in the eyes of all of Dagestan and Chechnya. Shamil’s position, however, was very difficult: on the one hand, the mountaineers were shocked by the appearance of the Russians in the very heart of the most inaccessible part of Dagestan, and on the other, the pogrom carried out by the Russians, the death of many brave murids and the loss of property undermined their strength and for some time time killed their energy. Soon circumstances changed. Unrest in the Kuban region and in southern Dagestan diverted most of the government troops to the south, as a result of which Shamil was able to recover from the blows inflicted on him and again win over some free societies to his side, acting on them either by persuasion or by force (end of 1838 and beginning 1839). Near Akhulgo, which was destroyed during the Avar expedition, he built New Akhulgo, where he moved his residence from Chirkat. In view of the possibility of uniting all the mountaineers of Dagestan under the rule of Shamil, the Russians during the winter of 1838-39 prepared troops, convoys and supplies for an expedition into the depths of Dagestan. It was necessary to restore free communications along all our routes of communication, which were now threatened by Shamil to such an extent that strong columns of all types of weapons had to be assigned to cover our transports between Temir-Khan-Shura, Khunzakh and Vnezapnaya. The so-called Chechen detachment of Adjutant General Grabbe was appointed to act against Shamil. Shamil, for his part, in February 1839 gathered an armed mass of 5,000 people in Chirkat, strongly fortified the village of Arguani on the way from Salatavia to Akhulgo, destroyed the descent from the steep Souk-Bulakh mountain, and, to divert attention, attacked on May 4 the submissive to Russia the village of Irganay and took its inhabitants to the mountains. At the same time, Tashav-haji, loyal to Shamil, captured the village of Miskit on the Aksai River and built a fortification near it in the Akhmet-Tala tract, from which he could at any time attack the Sunzha line or the Kumyk plane, and then strike in the rear when the troops will go deeper into the mountains when moving to Akhulgo. Adjutant General Grabbe understood this plan and, in a surprise attack, took and burned a fortification near Miskit, destroyed and burned a number of villages in Chechnya, stormed Sayasani, the stronghold of Tashav-haji, and on May 15 returned to Sudden. On May 21, he set out from there again.

Near the village of Burtunay, Shamil took a flank position on impregnable heights, but the Russian encircling movement forced him to go to Chirkat, and his militia dispersed in different directions. Working out a road along puzzling steep slopes, Grabbe climbed the Souk-Bulakh pass and on May 30 approached Arguani, where Shamil sat down with 16 thousand people to delay the movement of the Russians. After a desperate hand-to-hand battle for 12 hours, in which the highlanders and Russians suffered huge losses (the highlanders had up to 2 thousand people, we had 641 people), he left the village (June 1) and fled to New Akhulgo, where he locked himself up with his most devoted murids. Having occupied Chirkat (June 5), General Grabbe approached Akhulgo on June 12. The blockade of Akhulgo lasted for ten weeks; Shamil communicated freely with the surrounding communities, again occupied Chirkat and stood at our communications, bothering us from both sides; reinforcements flocked to him from everywhere; The Russians were gradually surrounded by a ring of mountain rubble. Help from the Samur detachment of General Golovin brought them out of this difficulty and allowed them to close a ring of batteries near New Akhulgo. Anticipating the fall of his stronghold, Shamil tried to enter into negotiations with General Grabbe, demanding free passage from Akhulgo, but was refused. On August 17, an attack occurred, during which Shamil again tried to enter into negotiations, but without success: on August 21, the attack resumed and after a 2-day battle, both Akhulgos were taken, and most of the defenders died. Shamil himself managed to escape, was wounded on the way and fled through Salatau to Chechnya, where he settled in the Argun Gorge. The impression of this pogrom was very strong; many societies sent atamans and expressed their submission; former associates of Shamil, including Tashav-hajj, planned to usurp the imam’s power and recruited followers, but were mistaken in their calculations: like a phoenix, Shamil was reborn from the ashes and already in 1840 he again began the fight against the Russians in Chechnya, taking advantage of the discontent of the mountaineers against our bailiffs and against attempts to take away their weapons. General Grabbe considered Shamil a harmless fugitive and did not care about his pursuit, which he took advantage of, gradually regaining his lost influence. Shamil intensified the dissatisfaction of the Chechens with a clever rumor that the Russians intended to turn the mountaineers into peasants and involve them in serving military service; The mountaineers were worried and remembered Shamil, contrasting the justice and wisdom of his decisions with the activities of the Russian bailiffs.

The Chechens invited him to lead the uprising; he agreed to this only after repeated requests, taking an oath from them and taking hostages from the best families. By his order, all of Lesser Chechnya and the villages near Sunzhenka began to arm themselves. Shamil constantly disturbed the Russian troops with raids by large and small parties, which moved from place to place with such speed, avoiding open battle with the Russian troops, that the latter were completely exhausted chasing them, and the Imam, taking advantage of this, attacked those who remained unprotected and submissive to Russia. society, subjugated them to his power and moved them to the mountains. By the end of May, Shamil had gathered a significant militia. Little Chechnya was completely deserted; its population abandoned their homes, rich lands and hid in the dense forests beyond the Sunzha and in the Black Mountains. General Galafeev moved (July 6, 1840) to Lesser Chechnya, had several heated clashes, by the way, on July 11 on the Valerika River (Lermontov took part in this battle, who described it in a wonderful poem), but despite huge losses, especially Valerike, the Chechens did not give up on Shamil and willingly joined his militia, which he now sent to northern Dagestan. Having won over the Gumbetians, Andians and Salatavites to his side and holding in his hands the exits to the rich Shamkhal plain, Shamil gathered a militia of 10 - 12 thousand people from Cherkey against 700 people of the Russian army. Having stumbled upon Major General Kluki von Klugenau, Shamil’s 9,000-strong militia, after stubborn battles on the 10th and 11th mules, abandoned further movement, returned to Cherkey, and then part of Shamil was sent home: he was waiting for a wider movement in Dagestan. Avoiding battle, he gathered a militia and worried the highlanders with rumors that the Russians would take the mounted highlanders and send them to serve in Warsaw. On September 14, General Kluki von Klugenau managed to challenge Shamil to battle near Gimry: he was defeated on his head and fled, Avaria and Koisubu were saved from plunder and devastation. Despite this defeat, Shamil's power was not shaken in Chechnya; All the tribes between Sunzha and Avar Koisu submitted to him, vowing not to enter into any relations with the Russians; Hadji Murat (1852), who betrayed Russia, went over to his side (November 1840) and agitated the Avalanche. Shamil settled in the village of Dargo (in Ichkeria, near the upper reaches of the Aksai River) and took a number of offensive actions. The cavalry party of Naib Akhverdy-Magoma appeared on September 29, 1840 near Mozdok and took several people captive, including the family of the Armenian merchant Ulukhanov, whose daughter, Anna, became Shamil’s beloved wife, under the name Shuanet.

By the end of 1840, Shamil was so strong that the commander of the Caucasian corps, General Golovin, considered it necessary to enter into relations with him, challenging him to reconcile with the Russians. This further raised the importance of the imam among the mountaineers. Throughout the winter of 1840 - 1841, gangs of Circassians and Chechens broke through Sulak and penetrated even to Tarki, stealing cattle and plundering near Termit-Khan-Shura itself, communication with the line became possible only with a strong convoy. Shamil ravaged the villages that tried to resist his power, took his wives and children with him to the mountains and forced the Chechens to marry their daughters to Lezgins, and vice versa, in order to connect these tribes with each other. It was especially important for Shamil to acquire such employees as Hadji Murat, who attracted Avaria to him, Kibit Magoma in southern Dagestan, very influential among the mountaineers, a fanatic, brave and capable self-taught engineer, and Jemaya ed-Din, an outstanding preacher. By April 1841, Shamil commanded almost all the tribes of mountainous Dagestan, except Koisubu. Knowing how important Cherkey’s occupation was for the Russians, he fortified all the routes there with rubble and defended them himself with extreme tenacity, but after the Russians outflanked them on both flanks, he retreated deep into Dagestan. On May 15, Cherkey surrendered to General Feza. Seeing that the Russians were busy building fortifications and left him alone, Shamil decided to take possession of Andalal, with the impregnable Gunib, where he expected to set up his residence if the Russians drove him out of Dargo. Andalal was also important because its inhabitants made gunpowder. In September 1841, the Andalians entered into relations with the imam; Only a few small villages remained in government hands. At the beginning of winter, Shamil flooded Dagestan with his gangs and cut off communications with the conquered societies and with Russian fortifications. General Kluki von Klugenau asked the corps commander to send reinforcements, but the latter, hoping that Shamil would cease his activities in the winter, postponed this matter until spring. Meanwhile, Shamil was not at all inactive, but was intensively preparing for next year’s campaign, not giving our exhausted troops a moment’s rest. Shamil's fame reached the Ossetians and Circassians, who had high hopes for him. On February 20, 1842, General Feze took Gergebil by storm. On March 2, he occupied Chokh without a fight and arrived in Khunzakh on March 7. At the end of May 1842, Shamil invaded Kazikumukh with 15 thousand militia, but, defeated on June 2 at Kyulyuli by Prince Argutinsky-Dolgoruky, he quickly cleared the Kazikumukh Khanate, probably because he received news of the movement of a large detachment of General Grabbe to Dargo. Having traveled only 22 versts in 3 days (May 30 and 31 and June 1) and having lost about 1,800 people out of action, General Grabbe returned back without doing anything. This failure unusually raised the spirit of the mountaineers. On our side, a number of fortifications along the Sunzha, which made it difficult for the Chechens to attack the villages on the left bank of this river, were supplemented by the construction of a fortification at Seral-Yurt (1842), and the construction of a fortification on the Assa River marked the beginning of the forward Chechen line.