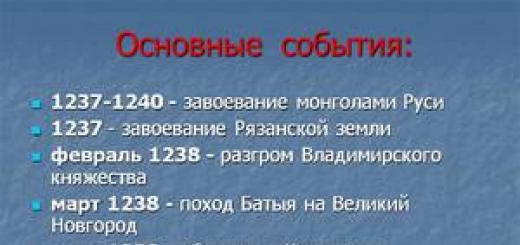

On September 6 (August 27), 1689, the Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed - the first peace treaty between Russia and China, the most important historical role of which is that it for the first time defined the state border between the two countries. The conclusion of the Nerchinsk Treaty put an end to the Russian-Qing conflict, also known as the “Albazin War”.

By the second half of the 17th century. The development of Siberia by Russian industrialists and merchants was already in full swing. First of all, they were interested in furs, which were considered an extremely valuable commodity. However, moving deeper into Siberia also required the creation of stationary points where food bases could be organized for the pioneers. After all, delivering food to Siberia at that time was almost impossible. Accordingly, settlements arose whose inhabitants were engaged not only in hunting, but also in agriculture. The development of Siberian lands took place. In 1649, the Russians entered the territory of the Amur region. Representatives of numerous Tungus-Manchu and Mongolian peoples lived here - Daurs, Duchers, Goguls, Achans.

Russian troops began to impose significant tribute on the weak Daur and Ducher principalities. The local aborigines could not resist the Russians militarily, so they were forced to pay tribute. But since the peoples of the Amur region were considered tributaries of the powerful Qing Empire, in the end this situation caused a very negative reaction from the Manchu rulers of China. Already in 1651, in the Achansky town, which was captured by the Russian detachment of E.P. Khabarov, a Qing punitive detachment was sent under the command of Haise and Sifu. However, the Cossacks managed to defeat the Manchu detachment. The Russian advance into the Far East continued. The next two decades went down in the history of the development of Eastern Siberia and the Far East as a period of constant battles between Russian and Qing troops, in which either the Russians or the Manchus were victorious. However, in 1666, the detachment of Nikifor of Chernigov was able to begin restoring the Albazin fortress, and in 1670 an embassy was sent to Beijing, which managed to negotiate a truce with the Manchus and the approximate delimitation of “spheres of influence” in the Amur region. At the same time, the Russians refused to invade the Qing lands, and the Manchus refused to invade the Russian lands. In 1682, the Albazin Voivodeship was officially created, headed by a voivode, and the coat of arms and seal of the voivodeship were adopted. At the same time, the Qing leadership again became concerned with the issue of ousting the Russians from the Amur lands, which the Manchus considered their ancestral possessions. Manchu officials from Pengchun and Lantan led an armed force sent to oust the Russians.

In November 1682, Lantan with a small reconnaissance detachment visited Albazin, conducting reconnaissance of its fortifications. To the Russians, he explained his presence in the vicinity of the fort by hunting deer. Having returned, Lantan reported to the leadership that the wooden fortifications of the Albazin fort were weak and there were no special obstacles to the military operation to oust the Russians from there. In March 1683, Emperor Kangxi gave the order to prepare for a military operation in the Amur region. In 1683-1684. Manchu troops periodically carried out raids on the outskirts of Albazin, which forced the governor to order a detachment of servicemen from Western Siberia to strengthen the fortress garrison. But given the specifics of transport communications at that time, the detachment moved extremely slowly. The Manchus took advantage of this.

At the beginning of the summer of 1685, the Qing army of 3-5 thousand people began to advance towards Albazin. The Manchus moved on river flotilla ships along the river. Sungari. Approaching Albazin, the Manchus began building siege structures and placing artillery. By the way, the Qing army that approached Albazin was armed with at least 30 cannons. The shelling of the fortress began. The wooden defensive structures of Albazin, which were built to protect the local Tungus-Manchu aborigines from arrows, could not withstand artillery fire. At least one hundred people from among the inhabitants of the fortress became victims of the shelling. On the morning of June 16, 1685, Qing troops began a general assault on the Albazin fortress.

It should be noted here that in Nerchinsk a detachment of 100 servicemen with 2 cannons under the command of governor Ivan Vlasov was assembled to help the garrison of Albazin. Reinforcements from Western Siberia, led by Afanasy Beyton, also hurried. But by the time the fortress was stormed, reinforcements did not arrive. In the end, the commander of the Albazin garrison, governor Alexei Tolbuzin, managed to agree with the Manchus on the withdrawal of the Russians from Albazin and retreat to Nerchinsk. On June 20, 1685, the Albazinsky fort was surrendered. However, the Manchus did not establish a foothold in Albazin - and this was their main mistake. Just two months later, on August 27, 1685, governor Tolbuzin returned to Albazin with a detachment of 514 servicemen and 155 peasants and tradesmen who restored the fortress. The fortress defenses were significantly strengthened, with the expectation that they could withstand artillery fire the next time. The construction of fortifications was led by Afanasy Beyton, a German who converted to Orthodoxy and Russian citizenship.

Fall of Albazin. Contemporary Chinese artist.

However, the restoration of Albazin was closely watched by the Manchus, whose garrison was stationed in the Aigun fortress, which was not so far away. Soon, Manchu troops again began to attack Russian settlers who were cultivating the fields in the vicinity of Albazin. On April 17, 1686, Emperor Kangxi ordered the military commander Lantan to take Albazin again, but this time not to abandon it, but to turn it into a Manchu fortress. On July 7, 1686, Manchu troops arrived near Albazin, delivered by a river flotilla. As in the previous year, the Manchus began shelling the town with artillery, but it did not produce the desired results - elliptical cannonballs in the earthen ramparts prudently built by the defenders of the fortress. However, during one of the attacks, governor Alexey Tolbuzin was killed. The siege of the fortress dragged on and the Manchus even erected several dugouts, preparing to starve out the garrison. In October 1686, the Manchus made a new attempt to storm the fortress, but it also ended in failure. The siege continued. By this time, about 500 servicemen and peasants had died in the fortress from scurvy, only 150 people remained alive, of whom only 45 were “on their feet.” But the garrison was not going to surrender.

When the next Russian embassy arrived in Beijing at the end of October 1686, the emperor agreed to a truce. On May 6, 1687, Lantan's troops retreated 4 versts from Albazin, but continued to prevent the Russians from sowing the surrounding fields, since the Manchu command hoped to force the garrison of the fortress to surrender through starvation. Treaty of Nerchinsk. Russia's first peace with China

Fedor Golovin

Meanwhile, on January 26, 1686, after news of the first siege of Albazin, a “great and plenipotentiary embassy” was sent from Moscow to China. It was led by three officials - steward Fyodor Golovin (in the photo, the future field marshal general and closest associate of Peter the Great), Irkutsk governor Ivan Vlasov and clerk Semyon Kornitsky. Fyodor Golovin (1650-1706), who headed the embassy, came from the boyar family of the Khovrins - Golovins, and by the time of the Nerchinsk delegation he was already a fairly experienced statesman. No less sophisticated was Ivan Vlasov, a Greek who accepted Russian citizenship and since 1674 served as a governor in various Siberian cities.

Accompanied by a retinue and guards, the embassy moved across Russia to China. In the fall of 1688, Golovin's embassy arrived in Nerchinsk, where the Chinese emperor asked for negotiations. Treaty of Nerchinsk. The first peace between Russia and China On the Manchu side, an impressive embassy was also formed, which was headed by Prince Songotu, the minister of the imperial court, who was in 1669-1679. regent under the young Kangxi and the de facto ruler of China, Tong Guegan - the emperor's uncle and Lantan - the military leader who commanded the siege of Albazin. The head of the embassy, Prince Songotu (1636-1703), was the brother-in-law of the Kangxi Emperor, who was married to the prince’s niece. Coming from a noble Manchu family, Songotu received a traditional Chinese education and was a fairly experienced and far-sighted politician. When Emperor Kangxi matured, he removed the regent from power, but continued to treat him with sympathy, and therefore Songotu continued to play an important role in the foreign and domestic policies of the Qing Empire.

Since the Russians did not know Chinese, and the Chinese did not know Russian, negotiations had to be conducted in Latin. For this purpose, the Russian delegation included Latin translator Andrei Belobotsky, and the Manchu delegation included the Spanish Jesuit Thomas Pereira and the French Jesuit Jean-François Gerbillon.

The meeting of the two delegations took place at an appointed place - on a field between the Shilka and Nercheya rivers, half a mile from Nerchinsk. The negotiations were held in Latin and began with the Russian ambassadors complaining about the Manchus starting hostilities without declaring war. The Manchu ambassadors countered that the Russians built Albazin without permission. At the same time, representatives of the Qing Empire emphasized that when Albazin was taken for the first time, the Manchus released the Russians unharmed on the condition that they would not return, but two months later they returned again and rebuilt Albazin.

Songotu - Minister of the Imperial Household

The Manchu side insisted that the Daurian lands belonged to the Qing Empire by patrimonial right, since the time of Genghis Khan, who was allegedly the ancestor of the Manchu emperors. In turn, the Russian ambassadors argued that the Daurs had long recognized Russian citizenship, which is confirmed by the payment of yasak to Russian troops. Fyodor Golovin's proposal was to draw the border along the Amur River, so that the left side of the river would go to Russia, and the right side to the Qing Empire. However, as the head of the Russian embassy later recalled, Jesuit translators who hated Russia played a negative role in the negotiation process. They deliberately distorted the meaning of the words of the Chinese leaders and because of this, the negotiations were almost in jeopardy. However, faced with the firm position of the Russians, who did not want to give up Dauria, representatives of the Manchu side proposed drawing the border along the Shilka River to Nerchinsk.

The negotiations lasted two weeks and were carried out in absentia, through translators - the Jesuits and Andrei Belobotsky. In the end, the Russian ambassadors understood how to act. They bribed the Jesuits by giving them furs and food. In response, the Jesuits promised to communicate all the intentions of the Chinese ambassadors. By this time, an impressive Qing army had concentrated near Nerchinsk, preparing to storm the city, which gave the Manchu embassy additional trump cards. However, the ambassadors of the Qing Empire proposed drawing the border along the Gorbitsa, Shilka and Arguni rivers.

When the Russian side again refused this offer, the Qing troops prepared for the assault. Then from the Russian side there was a proposal to make the Albazin fortress, which could be abandoned by the Russians, as a border point. But the Manchus again did not agree with the Russian proposal. The Manchus also emphasized that the Russian army could not arrive from Moscow to the Amur region in two years, so there was practically nothing to fear from the Qing Empire. In the end, the Russian side agreed with the proposal of the head of the Manchu embassy, Prince Songotu. The last negotiations were held on September 6 (August 27). The text of the treaty was read out, after which Fyodor Golovin and Prince Songotu swore to abide by the concluded treaty, exchanged copies of it and hugged each other as a sign of peace between Russia and the Qing Empire. Three days later, the Manchu army and navy retreated from Nerchinsk, and the embassy left for Beijing. Fyodor Golovin went back to Moscow with the embassy. By the way, Moscow initially expressed dissatisfaction with the results of the negotiations - after all, it was initially planned to draw the border along the Amur River, and the country’s authorities were poorly aware of the real situation that had developed on the border with the Qing Empire and overlooked the fact that in the event of a full-fledged confrontation, the Manchus could be destroyed by the few Russians detachments in the Amur region.

The Treaty of Nerchinsk had seven articles. The first article established the border between Russia and the Qing Empire along the Gorbitsa River, the left tributary of the Shilka River. Further, the border ran along the Stanovoy Ridge, and the lands between the Uda River and the mountains north of the Amur remained undemarcated. The second article established the border along the Argun River - from the mouth to the upper reaches, Russian territories remained on the left bank of the Argun. In accordance with the third article, the Russians were obliged to abandon and destroy the Albazin fortress. A special additional clause emphasized that both sides should not build any buildings in the area of the former Albazin. The fourth article emphasized the prohibition of accepting defectors by both sides. In accordance with the fifth article, trade between Russian and Chinese subjects and the free movement of all persons with special travel documents were allowed. The sixth article provided for expulsion and punishment for robbery or murder for Russian or Chinese nationals who crossed the border. The seventh article emphasized the right of the Manchu side to establish border markers on its territory.

The Nerchinsk Treaty became the first example of streamlining relations between Russia and China. Subsequently, there was a further delimitation of the borders of the two great states, but the agreement concluded in Nerchinsk, no matter how one treats it (and its results are still assessed by both Russian and Chinese historians differently - both as equal for the parties, and as beneficial exclusively for Chinese side), marked the beginning of the peaceful coexistence of Russia and China.

Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, the first treaty that determined the relations of the Russian state with the Manchu Qing Empire. Concluded on August 27 (September 6) after the war. conflict of 1683-1689, caused by the desire of the Manchu dynasty, which enslaved the Chinese people in the 17th century, to conquer the Amur region developed by the Russians. Having met the courageous resistance of the Russian garrisons in Albazin and in other forts (fortified points), as well as due to a number of other internal and external reasons, the Manchus were forced to abandon broad military plans and offer the Russian government negotiations in order to make peace and establish borders. The Russian government, not having sufficient military. forces for the defense of the Amur region, trying to establish permanent diplomatic relations. relations and develop trade ties with China, agreed to enter into peace negotiations. The negotiations took place near the walls of the Nerchinsk fort in an extremely difficult situation for the Russian side. Nerchinsk was blocked by the Manchu army and flotilla with a total number of 17 thousand people, equipped with artillery. Russian is available. The embassy had only 1.5 thousand people without sufficient ammunition and food. Thus, a real threat of military attack and extermination hung over Nerchinsk and the Russian embassy itself. Albazin, the main stronghold of the Russians in the Amur region, was also under siege. The Russian embassy was forced, under the terms of the Nerchinsk Treaty, to make large territorial concessions and leave the vast territory of the Albazin Voivodeship. Albazin, built by the Russians, was subject to destruction “to the ground,” while representatives of the Qing court gave an oral “sworn obligation” not to populate the “Albazin lands.” Argunsky fort and other Russians. the buildings were to be transferred from the right bank of the Argun to the left. The state border under the Nerchinsk Treaty was extremely vague (except for the section along the Argun River), and was outlined only in general terms. The names of the rivers and mountains that served as geographical landmarks were not identical in the Russian, Latin and Manchu copies of the treaty, which made it possible to interpret them differently. At the time of signing the agreement, the parties did not have any accurate maps of the demarcation area, the delimitation (see State Border) of the border was unsatisfactory, and its demarcation was not carried out at all. The delimitation of lands near the Okhotsk coast was postponed until more favorable times. When the Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed, there was no exchange of maps with the border line between the two countries marked on them. The Treaty of Nerchinsk also regulated issues of measures to combat defectors and persons who committed crimes in the territory. on the other hand, provided for a peaceful settlement of the border in any case. disputes and established the principle of equal trade rights for both sides. This opened up opportunities for the development of peaceful politics. and trade relations between Russia and the Qing Empire. In the mid-19th century, Russia managed to complete many years of diplomacy. struggle and achieve a revision of the terms of the Nerchinsk Treaty, which was reflected in the relevant articles of the Aigun Treaty of 1858 and the Beijing Russian-Chinese Treaty of 1860.

I. Savinov.

Materials from the Soviet Military Encyclopedia in 8 volumes, volume 5: Adaptive Radio Communication Line - Object Air Defense were used. 688 pp., 1978.

TREATY OF NERCHINSKY 1689 - the first treaty between Russia and China; delimited the spheres of influence of both states in the Amur region; concluded 6. IX okolnichy F. A. Golovin and the Chinese commissioners of Songotu and Tungustan.

The founding of the Russian city of Albazin and the imposition of taxes (yasak) on the Amur hunting tribes led to a conflict between China and the Russian state (see Albazin conflict). To resolve the conflict, a peace conference was convened in 1689. Nerchinsk was appointed as the meeting place with the Chinese representatives; This was the first time that the Chinese government agreed to negotiate on foreign territory and generally enter into a formal agreement with a foreign power.

Chinese commissioners - the court nobleman Songotu and the emperor's uncle Tungustan arrived in Nerchinsk on July 29, 1689 with a large military escort; representative (“grand ambassador”) of Russia Golovin arrived on August 18; the official meeting took place on 22. VIII. The Jesuits who were in Chinese service - the Spaniard Pereiro and the Frenchman Gerbillon - took a large part in the negotiations; negotiations were conducted in Latin, into which both Chinese and Russian speeches were translated. The Russians proposed establishing a border along the Amur River; in response, the Chinese demanded all the lands east of Lake Baikal, including Seleginsk and Nerchinsk, on the grounds that these lands supposedly belonged to Alexander the Great, whose heir the Chinese emperor considered himself to be. Then the Chinese lowered their demands, limiting themselves to the Amur basin from the mouth of the Argun to the sea. They supported this demand with a military demonstration on August 28 and the threat of renewed hostilities. 1. IX Chinese ambassadors demanded, in addition, the entire Okhotsk coast to the Chukotka Cape, but Golovin protested, holding the Chinese representatives responsible for a possible break. Negotiations resumed and ended with the conclusion of the Nerchinsk Treaty.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, the border was drawn on the left bank of the Amur along the Gorbitsa River and the Stanovoy Range and on the right bank along the Argun River. Thus, the entire course of the Amur proper went to China; Albazin was to be razed.

Despite the abandonment of the Amur River, the Treaty of Nerchinsk represented a great diplomatic success for the Russian government. It was virtually impossible to defend the Amur region with armed force due to its remoteness from the center of the state and the lack of available forces in Siberia. Meanwhile, the Nerchinsk Treaty opened up wide opportunities for trade with China, which the Russian merchants took advantage of immediately before the conclusion of the treaty. The delimitation outlined by the Treaty of Nerchinsk was made at the end of the 1720s by the Treaty of Kyakhta of 1727 (see), which basically confirmed the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

Diplomatic Dictionary. Ch. ed. A. Ya. Vyshinsky and S. A. Lozovsky. M., 1948.

The Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 is the first treaty that determined the relations of the Russian state with the Manchu Qing Empire. Signed on August 27. The need to resolve armed clashes between Russian Cossacks and peasant settlers in the Amur region with the Manchu armed detachments attacking them and trying to drive away the local population led to the opening in August 1689 of negotiations between the Russian embassy led by F. A. Golovin and representatives of the Qing government led by Songotu. Negotiations took place near the walls of the city of Nerchinsk, which was actually besieged by the Manchu army that had invaded Russian borders. The territorial articles of the Nerchinsk Treaty were forcibly imposed on the Russian representatives, forcing the Russians to leave the vast territory of the Albazin Voivodeship (Articles 1, 2, 3). The boundary line under the Treaty of Nerchinsk was extremely uncertain (except for the section along the Argun River), since the names of the rivers and mountains that served as geographical landmarks north of the Amur were not precise and identical in the Russian, Latin and Manchu copies of the treaty; The delimitation of lands near the Okhotsk coast was generally postponed until more favorable times. The Manchus did not exercise actual control over the territory that was ceded to them. Although the territorial articles of the Treaty of Nerchinsk were extremely unfavorable for the Russian state, the provisions on the opening of free trade for nationals of both states and the rules for the acceptance of diplomatic representatives, as well as measures to combat defectors (Articles 4, 5, 6) opened up opportunities for the development of peaceful political and trade Russia's relations with the Qing Empire. In the middle of the 19th century, Russia managed to complete many years of diplomatic struggle for the revision of the violent terms of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, and its almost no longer valid articles were replaced by corresponding articles Aigunsky(1858) and Beijing(1860) treaties.

V. S. Myasnikov. Moscow.

Soviet historical encyclopedia. In 16 volumes. - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia. 1973-1982. Volume 10. NAHIMSON - PERGAMUS. 1967.

Literature: Russian-Chinese relations 1689-1916. Official documents, M., 1958.

Read further:

The whole world in the 17th century (chronological table).

The Russian state in the 17th century (chronological table).

China in the 17th century (chronological table).

Publication:

Russian-Chinese relations. 1689-1916. Official documentation. M., 1958, p. 9-11.

Literature:

Yakovleva P. T. The first Russian-Chinese treaty of 1689. M., 1958;

Russian-Chinese relations in the 17th century. Materials and documents. T. 2. 1686-1691. M., 1972, p. 5-54;

Prokhorov A. On the issue of the Soviet-Chinese border. M., 1975, p. 23-87;

Alexandrov V. A. Russia at the Far Eastern Borders (Second half of the 17th century). M., 1969, p. 173-204.

Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, the first treaty that determined the relations of the Russian state with the Manchu Qing Empire. Concluded on August 27 (September 6) after the war. conflict of 1683-1689, caused by the desire of the Manchu dynasty, which enslaved the Chinese people in the 17th century, to conquer the Amur region developed by the Russians. Having met the courageous resistance of the Russian garrisons in Albazin and in other forts (fortified points), as well as due to a number of other internal and external reasons, the Manchus were forced to abandon broad military plans and offer the Russian government negotiations in order to make peace and establish borders. The Russian government, not having sufficient military. forces for the defense of the Amur region, trying to establish permanent diplomatic relations. relations and develop trade ties with China, agreed to enter into peace negotiations. The negotiations took place near the walls of the Nerchinsk fort in an extremely difficult situation for the Russian side. Nerchinsk was blocked by the Manchu army and flotilla with a total number of 17 thousand people, equipped with artillery. Russian is available. The embassy had only 1.5 thousand people without sufficient ammunition and food. Thus, a real threat of military attack and extermination hung over Nerchinsk and the Russian embassy itself. Albazin, the main stronghold of the Russians in the Amur region, was also under siege. The Russian embassy was forced, under the terms of the Nerchinsk Treaty, to make large territorial concessions and leave the vast territory of the Albazin Voivodeship. Albazin, built by the Russians, was subject to destruction “to the ground,” while representatives of the Qing court gave an oral “sworn obligation” not to populate the “Albazin lands.” Argunsky fort and other Russians. the buildings were to be transferred from the right bank of the Argun to the left. The state border under the Nerchinsk Treaty was extremely vague (except for the section along the Argun River), and was outlined only in general terms. The names of the rivers and mountains that served as geographical landmarks were not identical in the Russian, Latin and Manchu copies of the treaty, which made it possible to interpret them differently. At the time of signing the agreement, the parties did not have any accurate maps of the demarcation area, the delimitation (see State Border) of the border was unsatisfactory, and its demarcation was not carried out at all. The delimitation of lands near the Okhotsk coast was postponed until more favorable times. When the Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed, there was no exchange of maps with the border line between the two countries marked on them. The Treaty of Nerchinsk also regulated issues of measures to combat defectors and persons who committed crimes in the territory. on the other hand, provided for a peaceful settlement of the border in any case. disputes and established the principle of equal trade rights for both sides. This opened up opportunities for the development of peaceful politics. and trade relations between Russia and the Qing Empire. In the mid-19th century, Russia managed to complete many years of diplomacy. struggle and achieve a revision of the terms of the Nerchinsk Treaty, which was reflected in the relevant articles of the Aigun Treaty of 1858 and the Beijing Russian-Chinese Treaty of 1860.

I. Savinov.

Materials from the Soviet Military Encyclopedia in 8 volumes, volume 5: Adaptive Radio Communication Line - Object Air Defense were used. 688 pp., 1978.

TREATY OF NERCHINSKY 1689 - the first treaty between Russia and China; delimited the spheres of influence of both states in the Amur region; concluded 6. IX okolnichy F. A. Golovin and the Chinese commissioners of Songotu and Tungustan.

The founding of the Russian city of Albazin and the imposition of taxes (yasak) on the Amur hunting tribes led to a conflict between China and the Russian state (see Albazin conflict). To resolve the conflict, a peace conference was convened in 1689. Nerchinsk was appointed as the meeting place with the Chinese representatives; This was the first time that the Chinese government agreed to negotiate on foreign territory and generally enter into a formal agreement with a foreign power.

Chinese commissioners - the court nobleman Songotu and the emperor's uncle Tungustan arrived in Nerchinsk on July 29, 1689 with a large military escort; representative (“grand ambassador”) of Russia Golovin arrived on August 18; the official meeting took place on 22. VIII. The Jesuits who were in Chinese service - the Spaniard Pereiro and the Frenchman Gerbillon - took a large part in the negotiations; negotiations were conducted in Latin, into which both Chinese and Russian speeches were translated. The Russians proposed establishing a border along the Amur River; in response, the Chinese demanded all the lands east of Lake Baikal, including Seleginsk and Nerchinsk, on the grounds that these lands supposedly belonged to Alexander the Great, whose heir the Chinese emperor considered himself to be. Then the Chinese lowered their demands, limiting themselves to the Amur basin from the mouth of the Argun to the sea. They supported this demand with a military demonstration on August 28 and the threat of renewed hostilities. 1. IX Chinese ambassadors demanded, in addition, the entire Okhotsk coast to the Chukotka Cape, but Golovin protested, holding the Chinese representatives responsible for a possible break. Negotiations resumed and ended with the conclusion of the Nerchinsk Treaty.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, the border was drawn on the left bank of the Amur along the Gorbitsa River and the Stanovoy Range and on the right bank along the Argun River. Thus, the entire course of the Amur proper went to China; Albazin was to be razed.

Despite the abandonment of the Amur River, the Treaty of Nerchinsk represented a great diplomatic success for the Russian government. It was virtually impossible to defend the Amur region with armed force due to its remoteness from the center of the state and the lack of available forces in Siberia. Meanwhile, the Nerchinsk Treaty opened up wide opportunities for trade with China, which the Russian merchants took advantage of immediately before the conclusion of the treaty. The delimitation outlined by the Treaty of Nerchinsk was made at the end of the 1720s by the Treaty of Kyakhta of 1727 (see), which basically confirmed the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

Diplomatic Dictionary. Ch. ed. A. Ya. Vyshinsky and S. A. Lozovsky. M., 1948.

The Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 is the first treaty that determined the relations of the Russian state with the Manchu Qing Empire. Signed on August 27. The need to resolve armed clashes between Russian Cossacks and peasant settlers in the Amur region with the Manchu armed detachments attacking them and trying to drive away the local population led to the opening in August 1689 of negotiations between the Russian embassy led by F. A. Golovin and representatives of the Qing government led by Songotu. Negotiations took place near the walls of the city of Nerchinsk, which was actually besieged by the Manchu army that had invaded Russian borders. The territorial articles of the Nerchinsk Treaty were forcibly imposed on the Russian representatives, forcing the Russians to leave the vast territory of the Albazin Voivodeship (Articles 1, 2, 3). The boundary line under the Treaty of Nerchinsk was extremely uncertain (except for the section along the Argun River), since the names of the rivers and mountains that served as geographical landmarks north of the Amur were not precise and identical in the Russian, Latin and Manchu copies of the treaty; The delimitation of lands near the Okhotsk coast was generally postponed until more favorable times. The Manchus did not exercise actual control over the territory that was ceded to them. Although the territorial articles of the Treaty of Nerchinsk were extremely unfavorable for the Russian state, the provisions on the opening of free trade for nationals of both states and the rules for the acceptance of diplomatic representatives, as well as measures to combat defectors (Articles 4, 5, 6) opened up opportunities for the development of peaceful political and trade Russia's relations with the Qing Empire. In the middle of the 19th century, Russia managed to complete many years of diplomatic struggle for the revision of the violent terms of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, and its almost no longer valid articles were replaced by corresponding articles Aigunsky(1858) and Beijing(1860) treaties.

V. S. Myasnikov. Moscow.

Soviet historical encyclopedia. In 16 volumes. - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia. 1973-1982. Volume 10. NAHIMSON - PERGAMUS. 1967.

Literature: Russian-Chinese relations 1689-1916. Official documents, M., 1958.

Read further:

The whole world in the 17th century (chronological table).

The Russian state in the 17th century (chronological table).

China in the 17th century (chronological table).

Publication:

Russian-Chinese relations. 1689-1916. Official documentation. M., 1958, p. 9-11.

Literature:

Yakovleva P. T. The first Russian-Chinese treaty of 1689. M., 1958;

Russian-Chinese relations in the 17th century. Materials and documents. T. 2. 1686-1691. M., 1972, p. 5-54;

Prokhorov A. On the issue of the Soviet-Chinese border. M., 1975, p. 23-87;

Alexandrov V. A. Russia at the Far Eastern Borders (Second half of the 17th century). M., 1969, p. 173-204.

RUSSIAN-CHINESE TREATY ACTS

1689 August 27. - Treaty of Nerchinsk, concluded between Russia and China on the Russian-Chinese state border and terms of trade

/L. 2 / List of the treaty, as decided by boyar Fyodor Alekseevich Golovin 1 Chinese Khan with ambassadors from Sumgut 2 advisor with comrades at a congress at the turn near Nerchinsk in 7197 3 .

By the grace of God, the great sovereigns, kings and great princes John Alekseevich, Peter Alekseevich, all Great and Little and White Russia, autocrats and many states and lands of the eastern and western and northern fathers and fathers and heirs and sovereigns and possessors, their royal majesties great and plenipotentiary ambassadors neighbor okolnicha and governor of Bryansk Fedor Alekseevich Golovin, steward and governor of Yelatom Ivan Ostafievich Vlasov 4 , clerk Semyon Kornitskaya 5 , being at the ambassadorial congresses near Nerchinsk of the great Asian countries of the ruler, the most autocratic monarch among the wisest nobles, the Bogdoy 6 the law of the ruler, the affairs of the society of the people of the Chinese guardian and glory, the real Bogdoy and Chinese Bugdykhanov 7 Highness with the great ambassadors of Samgut, the court troops with the chief and the Inner Polat with the governor, the kingdom's adviser, and with Tumke-Kam 8 , Internal armor with a commander, the first rank prince and the khan's banner 9 with the master and the khan's uncle Ilamt 10 , one banner lord and others, they decided and approved by these treaty articles:

River named Gorbitsa 11 , which flows, going down, into the Shilka River, on the left side, near the river / L. 2v. / Black, the line between both states is to be decided.

Also from the top * Toya rivers with stone mountains 12 , which begin from that top of the river and along those very mountain peaks, even extending to the sea, the power of both states is divided, as if all the rivers, small or great, which from the midday sides of these mountains flow into the Amur River, be under the possession of the Khin state.

Likewise, all the rivers that come from the other sides of those mountains will be under the power of the Tsarist Majesty of the Russian state. Other rivers that lie in the middle between the Udya River under the Russian state ownership 13 and between the limited mountains that contain near the Amur, the possessions of the Khin state, and flow into the sea and all the existing lands in the middle, between that aforementioned river Udya and between the mountains that are located to the border, are not limited now and remain, since there are great borders on these lands and plenipotentiary ambassadors, without the decree of the Tsar's Majesty, defer without limitation until another favorable time, in which, upon the return of the ambassadors from both sides, the Tsar's Majesty will deign and Bugdykhanov's highness will want to ensure that the ambassadors or envoys are fond of sending, and then either through letters, or through The envoys assigned unlimited lands by the deceased and decent can calm and delimit cases.

In the same way, the river Argun, which flows into the Amur River, will set the border so that / L. 3 / to all the lands that are the left sides, walking along that river to the very peaks, under the possession of the Khinsky khan and the owner 14 , right side, also all the lands and contents on the side of the Tsar's Majesty of the Russian State and the entire structure on the half-day side of that Arguni River to be demolished to the other side of that river 15 .

The city of Albazin, which was built by the Tsar's Majesty, will be destroyed to the ground and the people staying there with all future military and other supplies with them will be taken away towards the Tsar's Majesty and not a small loss or any small things will be left there from them 16 .

The fugitives who, before this peace decree, were both from the side of the Tsar's Majesty and from the side of Bugdykhanov's Highness, will be on both sides without any hesitation, but who after this decree of peace will run across and such fugitives will be sent away without any delay from both sides without delay. to the border governors 17 .

Any people with travel certificates from both sides for the current established friendship for their affairs in both sides come and go to both states voluntarily and buy and sell what they need, may it be commanded 18 .

Previously, there were any future quarrels between foreign residents before this peace was established, for what purposes of both states / L. 3 rev. / industrial people will pass by and commit robbery or murder, and having caught such people, send them to the directions from which they come, to the border cities to the governors, and for this they will inflict cruel execution; They will unite with the large number of people and commit the above-described theft, and, having caught such self-willed people, they will be sent to the border governors, and for this they will be given the death penalty. And wars and bloodshed on both sides for such reasons and for the most borderline people do not charge crimes, but write about such quarrels, from which the parties will steal, both sides to the sovereign and break up those quarrels with amateur embassy transfers.

Against these articles decreed on the border by the embassy treaties, if Bugdykhanov’s Highness wants to put up some signs at the borders for memory, and sign these articles on them, then we submit to the will of Bugdykhanov’s Highness 19 .

Given at the borders of the Tsar's Majesty in the Daurian land, summer 7197 August 27th day 20 .

This is the letter from Andrei Belobotsky 21 written in Latin 22 .

Clamped according to sheets of secretary Fyodor Protopopov.

From the sheets (below the text): Translator Foma Rozanov read with an original copy.

AVPRI. F. Treatises. Op. 1.1689. D. 22. L. 2-3 vol. Certified copy. Published: Collection of treaties between Russia and China. 1689-1881. Published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. St. Petersburg, 1889. pp. 1-6; Russian-Chinese relations. Official documents. 1689-1916. M., 1958. S. 9-11; RKO in the 17th century. Materials and documents. T. 2. M., 1972. P. 656-659 (photocopy).

Original in Latin. - Right there. L. 6-6 vol. ** Published: Collection of treaties between Russia and China. 1689-1881. pp. 1-6; RKO in the 17th century. T. 2. P. 647-648 (photocopy).

The original is in Manchu. - Right there. L. 7 (boukdari) ***. Published: Collection of treaties between Russia and China. 1689-1881. pp. 7-10; RKO in the 17th century. T. 2. P. 651-655 (photocopy).

* So in the document.

** Sealed by the signatures and seals of F.A. Golovin, I.S. Vlasov, as well as the seal of the Heilongjiang Jiangjun, which is on the signatures of seven members of the Qing delegation (see comment No. 22 to doc.).

*** Sealed with the seal of the Heilongjiang Jiangjun and the signatures of seven members of the Qing delegation.

Comments

1 . Golovin Fedor Alekseevich (1650-1706), statesman and military leader, diplomat, associate of Peter I. After the conclusion of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, his successful career began. At the end of the 17th century. F.A. Golovin held high administrative positions. In 1699-1706. headed the Ambassadorial Prikaz; count (1701), admiral general (1699). For participation in the “Great Embassy” he was the first in Russia to be awarded the newly established Order of St. Andrew the First-Called (Bantysh-Kamensky D. N. Acts of famous commanders and ministers who served during the reign of Emperor Peter the Great. Part 1. M., 1812. P. 24-28; Russian-Chinese relations in the 17th century. Materials and documents. T. 2. 1686-1691. M., 1972. S. 762-763).

2 . Songotu, belonged to the Manchu Yellow Banner (see below), relative of the imperial family, chief educator of the heir to the throne, state adviser, commander of the imperial bodyguard corps; established Emperor Xuan Ye on the throne (Kangxi reign: 1662-1722). At one time he negotiated with the Russian ambassador N.G. Spafariy. Then he was in disgrace for about ten years. In 1688, he received a responsible assignment from the emperor - to head the embassy to negotiate with the Russians. But the embassy returned halfway, since it could not advance to Transbaikalia through the territory of Mongolia due to the entry of the forces of the Oirat Khan Galdan into Khalkha.

In 1689, the embassy was sent again. Emperor Xuan Ye appointed Songgotu and Tong Gogan as heads of the delegation (see below).

After the signing of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, Songotu spent several subsequent years dealing with issues related to Russia. He had the title of Grand Secretary (in Chinese: da xueshi) and was one of the main dignitaries of the empire. Later he took part in campaigns against Galdan. The year of his birth is unknown, he died around 1703 in prison, where he ended up as a result of palace intrigues (Eminent Chinese of the Ching Period (1644-1912). Edited by Arthur W. Hummel. Vol. 2. Washington. 1948. P. 663).

The word "Songotu" in Manchu means "crybaby", "whiny".

3 . The Treaty of Nerchinsk, which marked the beginning of the demarcation between Russia and China in the Amur region and determined diplomatic and trade relations between them, was signed in an atmosphere of military threat to the Russian delegation from the superior forces of the Manchus, so it should be considered violent. In the current situation, the Russian ambassador, in violation of the instructions he received, was forced to cede to the Qing Empire territory along the middle and part of the lower reaches of the Amur, along its left tributaries, as well as along the right bank of the Argun, which by that time had already belonged to Russia for over 40 years.

This was recognized by the Qing emperor and the government himself (Strategic plans for the pacification of the Russians (Pinding locha fanlue) // RKO in the 17th century. T. 2. P. 686; Notes T. Pereira. Right there. P. 730).

4. Vlasov Ivan Evstafievich (1628-1710), began his service as an Arzamas serviceman. In 1659 he participated in the embassy to Venice. In 1671 he was transferred from Arzamas to Moscow as head of Pushkar. Carried out a number of government assignments. In 1680 he was sent as a governor to Irkutsk, and in 1684 he was transferred to Nerchinsk. F.A. Golovin was appointed to the embassy as a person who knew local conditions well and was familiar with embassy affairs (Yakovleva P. T. The first Russian-Chinese treaty of 1689. M., 1958. P. 129).

5 . Kornitsky (Kornitsky) Semyon, was appointed clerk in Yeniseisk and even went there from Moscow. But in pursuit of him, a royal decree of March 19, 1686 was sent to appoint him to the embassy of F.A. Golovin instead of clerk Yudin, appointed to the embassy earlier (TsGADA. Siberian order. Stlb. 1589. L. 201 // RKO in the 17th century T. 2. P. 766).

6 . In Russia, the Manchus were once called “Bogdoytsy”.

7 . Bugdykhan (Mongol: bogdohan; Manchu: enduringe ezhen; Chinese: shengong), that is, “sacred sovereign” or “wisest sovereign,” “wise ruler.” The Qing emperors only styled themselves with this title, and did not bestow it on any of the other sovereigns.

As the Jesuit translator Father Amiot testified, during I. I. Kropotov’s stay in Beijing in 1763, the Manchu translators who translated the “sheets” of the Senate in Lifanyuan, fearing the wrath of the Qing emperor, “as usual,” left the title of “Her Imperial Majesty” without translation (Sarkisova G.I. Mission of the Russian courier I. I. Kropotov to Beijing in 1762-1763. (Archival materials) // East-Russia-West. Historical and cultural studies. To the 70th anniversary of Academician Vladimir Stepanovich Myasnikov. M., 2001. P. 101-102).

8 . Tong Guogan, State Councilor, corps commander, had the hereditary rank of 3rd degree prince, maternal uncle of Emperor Xuan Ye. One of the members of the 1688 embassy sent to negotiate with the Russian ambassador F.A. Golovin. In 1689, together with Songotu, he was appointed head of the embassy to Nerchinsk. In 1680 he took part in the operation against Galdan as commander of an artillery corps. Killed in the battle of Ulan-Butun (Eminent Chinise... Vol.2. P. 794).

9 . Under the Manchu Emperor Nurhaci (1559-1626), the entire population of Manchuria, regardless of tribal origin, was included in large military units - the “eight banners” or corps (in Manchu: zhakun gusa, in Chinese: bazi), which were pillar of Manchu rule in China. At first the troops consisted of four corps, each of which was assigned a banner of a certain color: yellow, white, red and blue. In 1615, when the population of Manchuria increased after military campaigns, four more banners were formed, receiving banners of the same colors, but with a border: a yellow banner with a red border, a white banner with a red border, a blue banner with a red border and red banner with a white border. The eight-banner troops were divided into two groups: the “highest three banners”, which included a yellow banner, a yellow banner with a border and a white one (they formed the personal guard of the Qing emperor and were subordinate to him) and the “lower five banners” (they were subordinate to military leaders appointed by the emperor ).

10 . Lantan (1634-1695), belonged to the Manchu White Banner, corps commander. After the death of his father, he inherited the title of prince of the 1st degree. He took part in the sieges of the Russian city of Albazin (see below), commanded the Manchu army stationed near Nerchinsk during negotiations with the Russian ambassador F.A. Golovin (see: Biography of Lantan // RKO in the 17th century. T. 2. P. 689-701).

11 . From a legal point of view, the agreement does not comply not only with modern international law, but also with interstate treaty acts of that time.

A big obstacle in the negotiations was the presence of a language barrier between the contracting parties. Russian representatives did not know either Manchu or Chinese, while Qing representatives knew Russian. Eventually Latin becomes the official language of negotiations.

The absence of a Manchu language translator in the Russian embassy, and, consequently, the possibility of familiarizing oneself with the Manchu text of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, greatly worried the Russian ambassador.

The Jesuit Portuguese Thomas Pereira (his name in Chinese: Xu Zhishen) and the Frenchman Jean François Gerbillon (his name in Chinese: Zhang Cheng), who arrived at the negotiations along with the Qing delegation as Latin translators and advisers, assured the Russian Ambassador that both texts were written “word for word”. However, doubts did not leave F.A. Golovin. In his “Article List” he wrote: “Is that letter (i.e., the agreement) genuine? Comp.) it is written in the Manzyut language equally with the letter of the Latin language, and the great and plenipotentiary ambassador has nothing to know, because in the Daurian prisons there is not an interpreter of the Manzyut language, not just a translator, found.”

In order to completely cast aside all doubts, F. A. Golovin, just before the signing of the Nerchinsk Treaty, asked the Chinese ambassadors: “What do they, the great ambassadors, have in the Manzyut language contract letter versus the contract letter written in Latin.” To which the Qing ambassadors replied, “Whatever the contract letter is written in Latin, the same is in Manzyutsk, and there will be no insignificant difference in those letters” (RKO in the 17th century, Vol. 2, pp. 594-595).

However, this statement was not true. In fact, the language barrier that existed between the Russian and Qing delegations led to a large number of inconsistencies between the multilingual texts of the treaty - Latin (main), Russian and Manchu.

Another equally difficult difficulty in concluding the agreement was the lack of accurate maps of the delimitation area by both contracting parties. Hence the inaccuracy of geographical landmarks that determine the passage of the Russian-Chinese border in multilingual texts. Thus, the Latin and Manchu texts of the Treaty of Nerchinsk say that r. Gorbitsa flows into the river. Sakhalyanyula (Amur), and in Russian, that the same river flows into the river. Shilka. At the same time, a reference point for determining the location of the river. Gorbitsy (in texts in Latin, Russian and Manchu) serves as r. Chernaya or Urum, flowing near Gorbitsa. The location of this river also requires special research, since two rivers with the name Gorbitsa flow in this area: in the river. The Amur (20-30 versts below the mouth of the Argun, not far from the Albazin River) flows into Bolshaya Gorbitsa or Amazar, and into the river. Shilka, 250 versts below Nerchinsk, flows into Malaya Gorbitsa. In the same area there are two rivers called Chernaya. One of them flows into the river. Shilka near the river. Malaya Gorbitsa, and the other river. Chernaya (Urum) flows into the Amur near Bolshaya Gorbitsa. In connection with this circumstance, G.V. Miller came to the conclusion that “the Greater Gorbitsa should be sent abroad rather than the Small Gorbitsa” (Miller G.V. Explanation of the doubts surrounding the establishment of the borders between the Russian and Chinese states 7197 (1689) // Monthly essays for the benefit and amusement of employees. St. Petersburg, 1757. April. P. 308).

Thus, if we are based on the Latin (main) and Manchu texts of the treaty, then Russia, according to the Nerchinsk Treaty, should have owned a much larger territory, since Bolshaya Gorbitsa is located 230 versts east of Malaya Gorbitsa. G.V. Miller claims that initially the Russian-Chinese border was established along Bolshaya Gorbitsa, but then the Manchus moved the border pillars to Malaya Gorbitsa (Ibid.). Of course, this statement requires additional research, but now we can only state that from the multilingual texts of the Nerchinsk Treaty it is impossible to establish along which Gorbitsa (Big or Small) the Russian-Chinese border in the Amur region was established.

12 . In the Russian and Latin texts of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, the direction of the Russian-Chinese border is indicated along the “stone mountains”. But since from r. Gorbitsy to the upper reaches of the river. Uda has several mountain branches (the Dzhugdzhur, Bureinsky, Amalin ridges, etc.), it is impossible to determine along which of them, according to the agreement, the line of the Russian-Chinese border in the Amur region passed.

However, it is known that the Russian ambassadors insisted that the border should pass through the mountains that are closest to the Amur (Yakovleva P. T. The first Russian-Chinese treaty of 1689, p. 195). These mountains could only be the Stanovoy Ridge, where the sources of the Bolshaya Gorbitsa are located.

In the Manchu text, this border landmark is given its own name - “Great Khingan”. Apparently the Qing representatives decided “that this chain is a direct continuation of the ridge they knew in Manchuria itself.” (Myasnikov V.S. The contractual articles were approved. Diplomatic history of the Russian-Chinese border of the 17th-20th centuries. M., 1996. P. 129). In this case, the Qing Empire could not lay claim to the territory on the left bank of the Amur, while Russia, on the contrary, could claim a large territory on the right bank of this river.

13 . Only the Russian text of the Nerchinsk Treaty says that r. Uda is "under Russian state ownership."

By inserting this phrase into the Russian text of the treaty, F.A. Golovin recorded the state of affairs that existed at that time in this area. Russian explorers back in the late 30s of the 17th century. began to explore Udskaya Bay and the adjacent area, and in the second half of the 17th century. on the left bank of the river. Uda, 30 versts from its mouth a Russian winter hut (and later the Uda fort) was already founded.

14 . The phrase that China owns the lands along the left (southern) bank of the river. Argun, “walking that river to the very tops,” that is, to its sources, is found only in the Russian text of the treaty.

The Qing ambassadors, obviously realizing that in this case a significant part of Mongolia and part of Manchuria (the Argun River originates on the border of Manchuria and Eastern Mongolia) would go to Russia, did not include a mention of the “peaks” of the river. Argun into the Manchu and Latin texts of the Treaty of Nerchinsk. But after the conclusion of the treaty, using this phrase, the Qing authorities began to populate the upper reaches of the Arguni. Subsequently, this led to disputes during the Russian-Chinese delimitation in the Khalkha-Mongolia region in 1727. When the Russian ambassador S. L. Vladislavich-Raguzinsky demanded that the Qing representatives at the negotiations evict the illegally settled Chinese citizens from there, the Qing officials stated that “in a peaceful In the treaty, the boundaries of the Argun River are written from their side to the peaks, but on the Russian side the peaks are not mentioned" (AVPRI. F. Relations between Russia and China. 1725. Op. 62/1. D. 12-a. L. 213-213 vol. , 229-229 vol.).

15 . Only in the Latin and Manchu texts (Articles 1 and 2, respectively) is the point to which all Russian buildings on the right bank of the river are specifically indicated. Argun was transferred to the left. This point is the mouth of the river. Meirelke (in the Latin text Mererki).

16 . In the 17th century The city of Albazin (formerly the fortress town of Yaksa, belonged to the local prince Albaza or Albadzhum, from which the name of the city comes), which occupied key positions on the approaches to Nerchinsk, the center of Russian colonization of the Amur region, became the main place of conflict between the Russians and the Manchus on the Amur. It was first destroyed by Manchu troops in 1659, but restored in 1668. In June 1685, the Manchu army, after long and careful preparation, besieged and then destroyed the city. Some of the Albazians surrendered. The rest of the population (about 300 people) was forced to leave Albazin. But then, having received reinforcements in Nerchinsk, in August of that year the Russians returned and restored the city. In the summer of 1686, the Manchu army again besieged Albazin, but, despite superior forces, could not take it.

In August 1687, the siege was lifted due to the start of negotiations between the Moscow government and the Beijing court, which ended with the signing of the Treaty of Nerchinsk on August 20, 1689.

Fulfilling the resolution of Art. 2nd and 3rd treatises On August 31, 1689, that is, two days after the signing of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, F.A. Golovin sent Cossacks to the Albazinsky and Argun forts “with instructions” about the destruction of these Russian forts and the withdrawal of the population to Russian territory (RKO in the 17th century. T. 2. P. 605-607).

17 . The flow of refugees to Russia continued after the conclusion of the Nerchinsk Treaty. Thus, on July 3, 1721, the extraordinary envoy to China of the Life Guards, Captain Lev Izmailov, reported from Beijing to the Siberian governor A. M. Cherkassky that on January 2 he received a letter from Lifanyuan, which reported that 700 Mongols, subjects of the Qing emperor , “they fled in the direction of His Imperial Majesty” and contained a demand, “that in order to find and return those fugitives with their armor, send him, the captain, a decree to His Imperial Majesty’s border guards, and if he does not do this, then there is no solution based on his proposal.” they didn’t want to fix it” (RKO in the 18th century. T. 1. 1700-1725. M., 1978. Doc. 235. P. 379).

On April 12, 1722, Emperor Peter I issued a decree on this matter, which stated: “those subjects of the Chinese Khan came towards His Imperial Majesty after the treaty points, those to be given, and from now on those who come, not to accept, but to give: and about that write to them; and those who came before the peace treaty, do not give them back" (ibid., p. 380).

To establish the true number of defectors from Mongolia, in December 1722, the Siberian governor sent “the first-ranking nobleman, Stepan Fefilov,” from Tobolsk. After establishing the exact number of defectors, Fefilov had to “make a brief statement” and write to the Russian agent Lorenz Lang, who was in Beijing, “so that upon receiving Fefilov from the search, he would present the statement to the Chinese Khan.” (Ibid. pp. 380-381).

On December 11, 1723, the Collegium of Foreign Affairs reported to the Senate information about Dzungar defectors to Russian territory, received from the Siberian Provincial Chancellery (AVPRI. Relations between Russia and China. 1723. D. 1. L. 48-49 // RKO in the 18th century. T. 2. 1725-1727. M., 1990. P. 620).

18 . The Qing government repeatedly violated this agreement and, under any pretext, stopped trade in Kyakhta, using this as a means of political pressure on the Russian government. Such pretexts could be disputes about the procedure for prosecuting cases of Russian citizens accused of murder or robbery in China, the extradition of defectors, etc.

19 . Soon after the conclusion of the treaty in November 1689 (Kangxi Reign, 28th year, 3rd month), by order of the Qing Emperor, Lantan and fudutong Zhao San were sent to the mouth of the river. Argun "to establish [here] a stele on the border demarcation." On June 17, they arrived at the place and placed at the mouth “a stone stele with an inscription carved [on it] in five languages: Manchu, Chinese, Russian, Mongolian and Latin [about the delimitation of lands]” (RKO in the 17th century, Vol. 2. C 696).

Let us note that in this case the Qing representatives violated Art. 6th Latin (main) text of the Treaty of Nerchinsk. According to this article, the inscription had to be carved in three languages: Chinese, Russian and Latin. The inscription in the same languages is also mentioned in the Manchu text of the treatise. The Russian text of the agreement does not indicate the languages in which “if Bugdykhanov’s highness wishes” the inscriptions on the border stele will be engraved.

In addition, the clause about the undelimited Ud space on the stele was engraved in a truncated manner, that is, essentially falsified. This part of the Treaty of Nerchinsk was not included in many later Chinese publications of the treaty.

Chinese text translated by N. Ya. Bichurin, engraved on the stele, see: Bichurin N. Ya. Statistical description of the Chinese Empire. Part 2. St. Petersburg, 1842. pp. 229-230; Myasnikov V. S. The contractual articles were approved. pp. 149-150.

20 . The date of signing the treaty, indicated under the Latin and Manchu texts (August 28), differs from the dating of the Russian text (August 27). Obviously this is related to the procedure for producing and signing texts. The Russian text was written on August 27, two copies in Latin and one in Manchu - on August 28, Latin copies were signed on August 29 (RKO in the 17th century. T. 2. P. 546). In historical literature, it is customary to date the Treaty of Nerchinsk on the day the Russian text of the treatise was produced, that is, August 27.

Unfortunately, the Russian text of the Nerchinsk Treaty is most likely lost.

When exchanging copies of the treaty, the Qing ambassadors swore to confirm “in their faith, raising their hands above their heads” that in the Albazin region “Khan Highness will never have any settlement, and only in Albazin places there will be guards” (RKO in the 17th century. Vol. 2. P. 597).

21 . Belobotsky Andrey, “stern” foreigner, translator of the Discharge Order. He taught Latin to the children of the Moscow nobility, including the children of F. A. Golovin (Yakovleva P. T. The first Russian-Chinese treaty of 1689, p. 130).

22 . The Russian ambassadors, at the insistence of the Qing ambassadors, also put their seals “by applying wax to the seal” also on the Latin copy of the treaty, which was handed over to F.A. Golovin by the Qing delegation during the exchange.

The round red seal of F.A. Golovin is located under the text of the agreement on the right side. In the center is an image of a lion facing to the right, with a sword in his raised right paw and a crown above his head. The edges of the seal are broken off, the inscription is partially preserved: “Okolnichey and the governor of Bryansk Fyodor Alekseevich Golovin.” Since the print was placed directly on the paper, large greasy spots appeared on it.

To the right of it is the seal of the second ambassador I. S. Vlasov. It is also round, made of red mastic, almost completely destroyed.

There, to the left of the seals of the Russian ambassadors, there is a red rectangular seal. On it (on the left) there is an inscription in Manchu: “Seal of Jiangjun, guarding the lands of the Amur and others,” and (on the right) the same inscription in stylized Chinese characters. The seal seals the signatures (in Manchu) of seven members of the Qing delegation: Songotu, Tong Guwe Gan, Lantan, Bandarsha, Sabsu, Mala, Unda.

You need to pay special attention to this seal. As follows from the “Article List” of F.A. Golovin, the Qing ambassadors during the negotiations stated that they “have the khan’s seal to reinforce the agreements, and with that seal those letters (agreements. - Comp.) they, the great ambassadors, will sign" (RKO in the 17th century. T. 2. P. 595). In his "Notes" T. Pereira also states that "after the treaty was signed, the ambassadors attached their seals in the same order “that they signed” the texts of the agreement (Ibid. p. 726).

But, as already said, under the texts of the treaty in Latin and Manchu is the seal not of the first ambassadors of the Qing delegation, but of the Heilongjiang Jiangjun Sabsu. Meanwhile, his name is listed fifth in the preamble of the Latin and Manchu texts and among the signatures under the Treaty of Nerchinsk. In the preamble to the Russian copy of the treatise, the name Sabsu is not mentioned at all.

Taking into account the special importance attached to the table of ranks, seals and etiquette in Qing China, it can be assumed that this was most likely the Manchus’ desire to humiliate the status of the Russian delegation.

Due to the absence of translators of the Manchu and Chinese languages in the Russian embassy, F. A. Golovin, naturally, remained in the dark about what kind of seal was placed on the Latin and Manchu texts of the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

Unlike the Latin, under the Manchu text the seal does not appear on the signatures of the members of the Qing delegation, but seals the date (in Manchu): Kangxi reign 28 year 7th moon 24 [date].

The translation of the Manchu text of the Treaty of Nerchinsk into Russian was first published in the collection "RKO in the 17th century. T. 2. P. 649-650. Since this collection has now become a bibliographic rarity, the treaty was again published in the already mentioned monograph by B. S. Myasnikov "Treaty articles approved", pp. 146-148.

We also note that all three texts of the Nerchinsk Treaty have a different number of articles. Moreover, articles under the same number sometimes differ in content.

There are other less significant discrepancies between the multilingual texts of the Nerchinsk Treaty.

The Treaty of Nerchinsk was not ratified by special acts; ratification was not provided for in any of its multilingual texts. F.A. Golovin, with great difficulty, managed to convince the Qing ambassadors of the need to exchange the already signed and sealed texts of the treaty. To the proposal of the Russian ambassadors, “that they, the great Chinese ambassadors, deign to write letters (i.e., the texts of the treaty. - Comp.) exchange: give yours to them, the great and plenipotentiary ambassador, and accept from them,” the Qing ambassadors replied, “so that the contractual letters, which they decided and signed with their own hands and sealed and, moreover, sealed for the fortress with seals in general, keep them with himself, but the exchanger has nothing to do with it" (RKO in the 17th century. T. 2. P. 596).

At the conclusion of the Nerchinsk Treaty, maps were not exchanged and the Russian-Chinese state border was not demarcated. Despite this, both parties did not violate its terms.

The greater importance the central administration of Russia attached to this treatise can be seen from the following fact. The articles of punishment issued upon the appointment of a new governor of the Nerchinsk district contained the full text of the Nerchinsk Treaty with the requirement of its strict compliance (RKO in the 17th century. T.1. P. 585).

Some provisions of the Treaty of Nerchinsk (on punishments for violating the border, on defectors, etc.) were applied in practice on the Russian-Mongolian border territory even before the conclusion of the Treaty of Kyakhta in 1727 (See document No. 5).

On September 6 (August 27), 1689, the Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed - the first peace treaty between Russia and China, the most important historical role of which is that it for the first time defined the state border between the two countries. The conclusion of the Nerchinsk Treaty put an end to the Russian-Qing conflict, also known as the “Albazin War”.

By the second half of the 17th century. The development of Siberia by Russian industrialists and merchants was already in full swing. First of all, they were interested in furs, which were considered an extremely valuable commodity. However, moving deeper into Siberia also required the creation of stationary points where food bases could be organized for the pioneers. After all, delivering food to Siberia at that time was almost impossible. Accordingly, settlements arose whose inhabitants were engaged not only in hunting, but also in agriculture. The development of Siberian lands took place. In 1649, the Russians entered the territory of the Amur region. Representatives of numerous Tungus-Manchu and Mongolian peoples lived here - Daurs, Duchers, Goguls, Achans.

Russian troops began to impose significant tribute on the weak Daur and Ducher principalities. The local aborigines could not resist the Russians militarily, so they were forced to pay tribute. But since the peoples of the Amur region were considered tributaries of the powerful Qing Empire, in the end this situation caused a very negative reaction from the Manchu rulers of China. Already in 1651, in the Achansky town, which was captured by the Russian detachment of E.P. Khabarov, a Qing punitive detachment was sent under the command of Haise and Sifu. However, the Cossacks managed to defeat the Manchu detachment. The Russian advance into the Far East continued. The next two decades entered into the development of Eastern Siberia and the Far East as a period of constant battles between Russian and Qing troops, in which either the Russians or the Manchus were victorious. However, in 1666, the detachment of Nikifor of Chernigov was able to begin restoring the Albazin fortress, and in 1670 an embassy was sent to Beijing, which managed to negotiate a truce with the Manchus and the approximate delimitation of “spheres of influence” in the Amur region. At the same time, the Russians refused to invade the Qing lands, and the Manchus refused to invade the Russian lands. In 1682, the Albazin Voivodeship was officially created, headed by a voivode, and the coat of arms and seal of the voivodeship were adopted. At the same time, the Qing leadership again became concerned with the issue of ousting the Russians from the Amur lands, which the Manchus considered their ancestral possessions. Manchu officials from Pengchun and Lantan led an armed force sent to oust the Russians.

In November 1682, Lantan with a small reconnaissance detachment visited Albazin, conducting reconnaissance of its fortifications. To the Russians, he explained his presence in the vicinity of the fort by hunting deer. Having returned, Lantan reported to the leadership that the wooden fortifications of the Albazin fort were weak and there were no special obstacles to the military operation to oust the Russians from there. In March 1683, Emperor Kangxi gave the order to prepare for a military operation in the Amur region. In 1683-1684. Manchu troops periodically carried out raids on the outskirts of Albazin, which forced the governor to order a detachment of servicemen from Western Siberia to strengthen the fortress garrison. But given the specifics of transport communications at that time, the detachment moved extremely slowly. The Manchus took advantage of this.

At the beginning of the summer of 1685, the Qing army of 3-5 thousand people began to advance towards Albazin. The Manchus moved on river flotilla ships along the river. Sungari. Approaching Albazin, the Manchus began building siege structures and placing artillery. By the way, the Qing army that approached Albazin was armed with at least 30 cannons. The shelling of the fortress began. The wooden defensive structures of Albazin, which were built to protect the local Tungus-Manchu aborigines from arrows, could not withstand artillery fire. At least one hundred people from among the inhabitants of the fortress became victims of the shelling. On the morning of June 16, 1685, Qing troops began a general assault on the Albazin fortress.

It should be noted here that in Nerchinsk a detachment of 100 servicemen with 2 cannons under the command of governor Ivan Vlasov was assembled to help the garrison of Albazin. Reinforcements from Western Siberia, led by Afanasy Beyton, also hurried. But by the time the fortress was stormed, reinforcements did not arrive. In the end, the commander of the Albazin garrison, governor Alexei Tolbuzin, managed to agree with the Manchus on the withdrawal of the Russians from Albazin and retreat to Nerchinsk. On June 20, 1685, the Albazinsky fort was surrendered. However, the Manchus did not begin to gain a foothold in Albazin - and this was their main mistake. Just two months later, on August 27, 1685, governor Tolbuzin returned to Albazin with a detachment of 514 servicemen and 155 peasants and tradesmen who restored the fortress. The fortress defenses were significantly strengthened, with the expectation that they could withstand artillery fire the next time. The construction of fortifications was led by Afanasy Beyton, a German who converted to Orthodoxy and Russian citizenship.

Fall of Albazin. Contemporary Chinese artist.

However, the restoration of Albazin was closely watched by the Manchus, whose garrison was stationed in the Aigun fortress, which was not so far away. Soon, Manchu troops again began to attack Russian settlers who were cultivating the fields in the vicinity of Albazin. On April 17, 1686, Emperor Kangxi ordered the military commander Lantan to take Albazin again, but this time not to abandon it, but to turn it into a Manchu fortress. On July 7, 1686, Manchu troops arrived near Albazin, delivered by a river flotilla. As in the previous year, the Manchus began shelling the town with artillery, but it did not produce the desired results - the cannonballs were lodged in the earthen ramparts prudently built by the defenders of the fortress. However, during one of the attacks, governor Alexey Tolbuzin was killed. The siege of the fortress dragged on and the Manchus even erected several dugouts, preparing to starve out the garrison. In October 1686, the Manchus made a new attempt to storm the fortress, but it also ended in failure. The siege continued. By this time, about 500 servicemen and peasants had died in the fortress from scurvy, only 150 people remained alive, of whom only 45 were “on their feet.” But the garrison was not going to surrender.

When the next Russian embassy arrived in Beijing at the end of October 1686, the emperor agreed to a truce. On May 6, 1687, Lantan's troops retreated 4 versts from Albazin, but continued to prevent the Russians from sowing the surrounding fields, since the Manchu command hoped to force the garrison of the fortress to surrender through starvation.

Meanwhile, on January 26, 1686, after news of the first siege of Albazin, a “great and plenipotentiary embassy” was sent from Moscow to China. It was led by three officials - steward Fyodor Golovin (in the photo, the future field marshal general and closest associate of Peter the Great), Irkutsk governor Ivan Vlasov and clerk Semyon Kornitsky. Fyodor Golovin (1650-1706), who headed the embassy, came from the boyar family of the Khovrins - Golovins, and by the time of the Nerchinsk delegation he was already a fairly experienced statesman. No less sophisticated was Ivan Vlasov, a Greek who accepted Russian citizenship and since 1674 served as a governor in various Siberian cities.

Accompanied by a retinue and guards, the embassy moved across Russia to China. In the fall of 1688, Golovin's embassy arrived in Nerchinsk, where the Chinese emperor asked for negotiations.  An impressive embassy was also formed on the Manchu side, headed by Prince Songotu, the minister of the imperial court, who served in 1669-1679. regent under the young Kangxi and the de facto ruler of China, Tong Guegan - the emperor's uncle and Lantan - the military leader who commanded the siege of Albazin. The head of the embassy, Prince Songotu (1636-1703), was the brother-in-law of the Kangxi Emperor, who was married to the prince’s niece. Coming from a noble Manchu family, Songotu received a traditional Chinese education and was a fairly experienced and far-sighted politician. When Emperor Kangxi matured, he removed the regent from power, but continued to treat him with sympathy, and therefore Songotu continued to play an important role in the foreign and domestic policies of the Qing Empire.

An impressive embassy was also formed on the Manchu side, headed by Prince Songotu, the minister of the imperial court, who served in 1669-1679. regent under the young Kangxi and the de facto ruler of China, Tong Guegan - the emperor's uncle and Lantan - the military leader who commanded the siege of Albazin. The head of the embassy, Prince Songotu (1636-1703), was the brother-in-law of the Kangxi Emperor, who was married to the prince’s niece. Coming from a noble Manchu family, Songotu received a traditional Chinese education and was a fairly experienced and far-sighted politician. When Emperor Kangxi matured, he removed the regent from power, but continued to treat him with sympathy, and therefore Songotu continued to play an important role in the foreign and domestic policies of the Qing Empire.

Since the Russians did not know Chinese, and the Chinese did not know Russian, negotiations had to be conducted in Latin. For this purpose, the Russian delegation included Latin translator Andrei Belobotsky, and the Manchu delegation included the Spanish Jesuit Thomas Pereira and the French Jesuit Jean-François Gerbillon.

The meeting of the two delegations took place at an appointed place - on a field between the Shilka and Nercheya rivers, half a mile from Nerchinsk. The negotiations were held in Latin and began with the Russian ambassadors complaining about the Manchus starting hostilities without declaring war. The Manchu ambassadors countered that the Russians built Albazin without permission. At the same time, representatives of the Qing Empire emphasized that when Albazin was taken for the first time, the Manchus released the Russians unharmed on the condition that they would not return, but two months later they returned again and rebuilt Albazin.

The Manchu side insisted that the Daurian lands belonged to the Qing Empire by patrimonial right, since the time of Genghis Khan, who was allegedly the ancestor of the Manchu emperors. In turn, the Russian ambassadors argued that the Daurs had long recognized Russian citizenship, which is confirmed by the payment of yasak to Russian troops. Fyodor Golovin's proposal was to draw the border along the Amur River, so that the left side of the river would go to Russia, and the right side to the Qing Empire. However, as the head of the Russian embassy later recalled, Jesuit translators who hated Russia played a negative role in the negotiation process. They deliberately distorted the meaning of the words of the Chinese leaders and because of this, the negotiations were almost in jeopardy. However, faced with the firm position of the Russians, who did not want to give up Dauria, representatives of the Manchu side proposed drawing the border along the Shilka River to Nerchinsk.

The negotiations lasted two weeks and were carried out in absentia, through translators - Jesuits and Andrei Belobotsky. In the end, the Russian ambassadors understood how to act. They bribed the Jesuits by giving them furs and food. In response, the Jesuits promised to communicate all the intentions of the Chinese ambassadors. By this time, an impressive Qing army had concentrated near Nerchinsk, preparing to storm the city, which gave the Manchu embassy additional trump cards. However, the ambassadors of the Qing Empire proposed drawing the border along the Gorbitsa, Shilka and Arguni rivers.