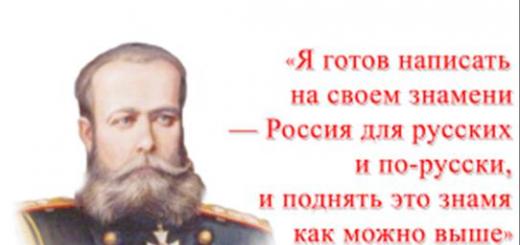

Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev

Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev- outstanding Russian military leader and strategist, infantry general (1881), adjutant general (1878). Participant in the Central Asian conquests of the Russian Empire and the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878, liberator of Bulgaria from the Turkish yoke. He went down in history with the nickname “White General” (the Turks called him Ak Pasha), which is always associated primarily with him, because in battles he was always in a white uniform and on a white horse.

M.D. Skobelev was born on September 17 (29), 1843 in St. Petersburg - died on June 25 (July 7), 1882 in Moscow. M.D. Skobelev was buried in his family estate, the village of Spassky-Zaborovsky, Ranenburg district, Ryazan province, next to his parents. Son of Lieutenant General Dmitry Ivanovich Skobelev and his wife Olga Nikolaevna, née Poltavtseva. Father and grandfather were generals, Knights of St. George.

M.D. Skobelev was a supporter of bold and decisive actions, and had deep and comprehensive knowledge of military affairs. He spoke English, French, German and Uzbek languages. Skobelev's successful actions created him great popularity in Russia and Bulgaria, where streets, squares and parks in many cities were named after him.

At first he was raised by a German tutor, with whom his relationship did not work out. Then he was sent to Paris to a boarding house with the Frenchman Desiderius Girardet. Over time, Girardet became a close friend of Skobelev and followed him to Russia and was with him during the hostilities. Later he continued his education in Russia. In 1858-1860, Skobelev was preparing to enter St. Petersburg University under the general supervision of Academician A.V. Nikitenko. Skobelev successfully passed the entrance exams, but the university was closed due to student unrest.

November 22, 1861 M.D. Skobelev entered military service in the Cavalry Regiment. After passing the exams on September 8, 1862, he was promoted to harness cadet, and on March 31, 1863 to cornet. In February 1864, he accompanied, as an orderly, the Adjutant General Count Baranov, who was sent to Warsaw to promulgate the Manifesto on the liberation of the peasants and the provision of land to them. On March 19, at his request, he was transferred to the Grodno Hussar Regiment. For his participation in the destruction of the Shemiot detachment in the Radkowice Forest, Skobelev was awarded the Order of St. Anne, 4th degree, “for bravery.” On August 30, 1864, Skobelev was promoted to lieutenant. In the fall of 1866, he entered the Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff and successfully graduated from it in 1868. After graduating from the academy, he was assigned to the corps of officers of the General Staff and sent to serve at the headquarters of the Turkestan Military District. There he was appointed commander of the Siberian Cossack hundred. At the end of 1870, Skobelev was sent to the command of the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasian Army, and in March 1871 he was sent to the Krasnovodsk detachment in which he commanded the cavalry. There Skobelev received an important task; with a detachment he was supposed to reconnoiter the routes to Khiva. He reconnoitered the route to the Sarakamysh well, and walked along a difficult road, with a lack of water and scorching heat, from Mullakari to Uzunkuyu, 437 km in 9 days, and back to Kum-Sebshen, 134 km. Skobelev presented a detailed description of the route and the roads leading from the wells. In 1872, he was seconded to the General Staff, where he served on the military scientific committee. He was then transferred to the headquarters of an infantry division stationed in Novgorod, where he commanded an infantry battalion and received the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Fame as a military leader and extensive combat experience M.D. Skobelev acquired it during the expeditions of the Russian army to Central Asia, which were caused by constant clashes on the state border in the Orenburg region and the process of voluntary entry into Russian citizenship of the Kazakhs, who were under the authority of the Kokand and Khiva khanates, the Bukhara Emirate.

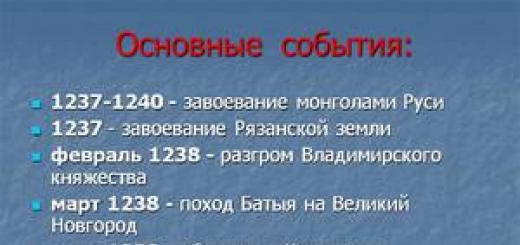

M.D. Skobelev took part in the Khiva campaign of 1873. Turkestan Governor-General K.P. Kaufman, remembering the failures of previous campaigns of Russian troops against Khiva, carefully organized a military expedition. The Khanate, surrounded by waterless deserts, was attacked by four Russian detachments from four sides. The most difficult route ran from Krasnovodsk and from the Mangyshlak peninsula (Skobelev was part of the Mangyshlak detachment). The Turkestan troops were reinforced by experienced Caucasian troops who had participated in the war against Imam Shamil, and an additional number of Cossack troops.

Crossing the river Amu Darya

During the Khiva campaign, Lieutenant Colonel M.D. Skobelev repeatedly showed personal courage. For military valor during reconnaissance(intelligence) near the village of Imdy-Kuduk he was awarded the Order of St. George, 4th degree. On May 5, near Itybai’s well, Skobelev with a small detachment met a caravan of Kazakhs who had gone over to the side of Khiva. Skobelev, despite the numerical superiority of the enemy, rushed into battle, in which he received 7 wounds with pikes and checkers and could not sit on a horse until May 20.

Capture of Samarkand

On May 29, 1873, the capital of the Khanate - the ancient city of Khiva - surrendered to Russian troops almost without a fight after a short artillery bombardment, led by Skobelev. The Khanate of Khiva recognized its vassal dependence on the Russian Empire, paid an indemnity of 2,200,000 rubles, and abolished slavery. Many Russian captive slaves captured by the Khivans in the Orenburg border area received freedom.

Khiva Gate

In the winter of 1873-1874, Skobelev received leave and spent most of it in southern France where he underwent treatment. February 23 M.D. Skobelev was promoted to colonel. On April 17, he was appointed aide-de-camp and enrolled in the retinue of His Imperial Majesty.

Since April 1875, Skobelev continued to serve in the Turkestan region. At that time, in Kokand, where bloody strife took place between Khan Khudoyar and his closest relatives, who took up arms against him, a real internecine war broke out, in which Russian troops were forced to get involved. The Kokands concentrated up to 50,000 people with 40 guns at Makhram. On August 22, General Kaufman's troops stormed Makhram. Skobelev and his cavalry quickly attacked numerous enemy crowds of foot and horsemen, put them to flight and pursued them for more than 10 miles. For the brilliant command of the cavalry M.D. Skobelev was promoted to major general.

Russians in Kokand

Attack in Kashgaria

In January-February 1876, Russian troops under the command of Skobelev in the battles of Andijan and Asaka defeated the rebellious Kokand people, led by the Kokand dignitary Aftobachi. In Asaka, a 15,000-strong rebel detachment was defeated. After this, Aftobachi surrendered to the tsarist troops, and they allowed him to settle in Russia and take with him one of his three harems. The victories led to the fact that in the same 1876 the Kokand Khanate ceased to exist, and in its place the Fergana region was formed, which became part of the Turkestan Governor-General. General Skobelev was appointed military governor and commander of the Fergana region, and was also awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd degree with swords and the Order of St. George, 3rd degree, as well as a gold sword with diamonds with the inscription “for bravery.” Largely thanks to him, bloodshed was stopped in the territory of the former Kokand Khanate. By order of Skobelev, Pulat-bek was executed in Margilan, having executed 4,000 of his subjects in three months. In the summer of 1876, General Skobelev undertook a mountain expedition to the borders of Kashgaria.

M.D. Skobelev was very popular among Russian soldiers. The pinnacle of his military glory was the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878 for the liberation of Orthodox Bulgaria from centuries-old Ottoman rule.

At first, he was at the headquarters of the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, carrying out his instructions. Then he was appointed chief of staff of the combined Cossack division, commanded by his father Dmitry Ivanovich Skobelev.

Crossing at Zimnice

On June 14-15, 1877, Skobelev participated in the crossing of General Dragomirov’s detachment across the Danube at Zimnitsa. Taking command of 4 companies of the 4th Infantry Brigade, he struck the Turks on the flank, forcing them to retreat and ensuring the crossing of the Danube. For this battle he was awarded the Order of St. Stanislaus, 1st class with swords. After crossing the Danube, he participated on June 25 in the reconnaissance and capture of the city of Bela. July 3 in repelling the Turkish attack on Selvi, and July 7, with the troops of the Gabrovsky detachment, in occupying the Shipka Pass.

After the Plevna failures, on August 22, 1877, a brilliant victory was won in the capture of Lovchi, in which the Turks carried out a massacre of the local population. The Sultan's general Rifat Pasha, who had 8,000 soldiers, fortified himself in the city. Russian troops took the city by storm, capturing the fortifications on Mount Cherven-Bryag. The remnants of the Turkish garrison - 400 people - barely escaped the pursuit of the Caucasian Cossack brigade. The Russian army then lost about 1,500 soldiers. Skobelev again showed his talents in the command of the forces entrusted to him, for which on September 1 M.D. Sobelev was promoted to lieutenant general and given command of the 18th Infantry Division. From that time on, the nickname of the White General stuck to him, and the Turks also called him Ak Pasha (White General).

During the third assault on Plevna, where the best Sultan's army was located, Skobelev commanded the left flank detachment.

On Shipka

Assault on the Gravitsky redoubt near Plevna

Battle of Plevna

The Skobelev division participated in the blockade of Plevna until its last days. It was Skobelev who managed to repel the attack of Osman Pasha from the blocked fortress on the night of November 28. The Sultan's commander lost 6,000 soldiers in this battle. After this, the Plevna garrison capitulated: 41,200 soldiers, 2,128 officers and 10 generals surrendered, along with the commander Osman Pasha himself. Lieutenant General M.D. Skobelev was appointed commandant of Plevna.

M.D. Skobelev near Sheinovo

When the Russian command discussed the plan for further waging war with Turkey, Skobelev spoke in favor of crossing the Balkan Mountains and attacking the Turkish capital Istanbul. His detachment of 16,000 soldiers with 14 guns made the transition in winter conditions through the Balkans along the Imetli Pass.

In the Balkan Mountains

In the Russian-Turkish War M.D. Skobelev especially distinguished himself in the Shipko-Sheinovsky battle, where his 16th Infantry Division played a decisive role. Opposite the Shipka Pass stood the second fighting army of the Ottoman Empire under the command of Wessel Pasha, numbering 35,000 people with 108 guns. Its main forces were located in the fortified camp of Sheinovo. The Russians attacked Wessel Pasha's army with 45,000 men and 83 guns. The attack was carried out in three columns under the command of Lieutenant General F.F. Radetsky, N.I. Svyatopolk-Mirsky and M.D. Skobeleva. It was Skobelev’s column that had to storm the main fortifications of the enemy camp; Russian infantrymen captured several redoubts, batteries and trench lines with a bayonet attack. At about 3 o'clock, Wessel Pasha ordered the white flag to be thrown out. The surrender of Wessel Pasha was personally accepted by M.D. Skobelev. The victory in the Shipko-Sheinovsky battle brought glory to the Russian army. Now the path through the Balkans to Southern Bulgaria was open. Taking this situation into account, the Russian command decided to immediately attack the city of Adrianople, which was located on the close approaches to Istanbul. Skobelev was entrusted with the vanguard of the central detachment with the right to conduct independent actions. The offensive began on January 3, 1788. In one day, Skobelev's infantry and cavalry walked down from the mountains more than 85 km. With a sudden blow, Russian troops captured Adrianople, its fortress garrison capitulated. Skobelev's detachment entered the city to the sounds of a military orchestra. Among other trophies in the fortress arsenal were 22 large-caliber guns from the German Krupp factories, which the Turks never had time to use in battle.

In February, Skobelev’s troops occupied San Stefano, which stood on the closest approaches to Istanbul, just 12 km from it, and directly reached the road to the Turkish capital. There was no one to defend Istanbul - the best Sultan’s armies capitulated, one was blocked in the Danube region, and the army of Suleiman Pasha was recently defeated south of the Balkan Mountains. Skobelev was temporarily appointed commander of the 4th Army Corps, stationed in the vicinity of Adrianople. On March 3, 1878, a peace treaty was signed in San Stefano, according to which Bulgaria became an independent principality, Turkey recognized the sovereignty of Serbia, Montenegro and Romania. Southern Bessarabia and Batum, Kars, Ardahan and Bayazet in the Caucasus were annexed to the Russian Empire. The defeated Ottoman Porte paid 31,000,000 rubles in war indemnity. Skobelev was very famous after the war. On January 6, 1878, he was awarded a gold sword with diamonds, with the inscription “for crossing the Balkans.” The Russian army, under the terms of the San Stefano Peace Treaty, remained on Bulgarian soil for two years. On January 8, 1879, Skobelev was appointed its commander-in-chief. As a reward for victory in this war, he received the court rank of adjutant general.

From Bulgaria M.D. Skobelev returned to his homeland in an aura of glory as a universally recognized national hero. He was appointed commander of an army corps with headquarters in Minsk, and his name was forever included in the lists of the 44th Kazan Infantry Regiment.

In January 1880, Lieutenant General M.D. Skobelev was appointed head of the 2nd Akhal-Teke expedition in the south of Central Asia. The talk was about annexing the Akhal-Teke oasis to Russia, where the largest Turkmen tribe of Tekins lived, who wanted to recognize the power of the white king over themselves and were able to field 25,000 warriors, mostly on horseback. The Tekins had a strong fortress Geok-Tepe(Dengil-Tepe) 45 km northwest of Ashgabat.

In the Turkmen sands

Skobelev most thoroughly prepared his troops (13,000 people with 100 guns) for the difficult transition through the sandy desert to the Geok-Tepe fortress. Rear supply bases were established in Chikishlyar and Krasnovodsk. The expeditionary force was assigned siege artillery. Transportation of troops and cargo was carried out across the Caspian Sea. Relying on rear bases, the expeditionary forces occupied all the Tekin fortifications in 5 months. Construction of a railway to Ashgabat began from Krasnovodsk. In the Geok-Tepe fortress there were 45,000 people, of which 25,000 were defenders, they had 5,000 rifles, many pistols, 1 gun. The Tekins carried out forays, had the advantage at night and inflicted considerable damage, once capturing two guns.

Before the assault on Geok-Tepe

The assault on the fortress took place on January 12, 1881. At 11:20 a.m. a mine exploded. The eastern wall fell and a collapse convenient for an assault formed. The dust had not yet settled when Colonel Kuropatkin's column rose to attack. Lieutenant Colonel Gaidarov managed to capture the western wall. The troops pressed back the enemy, who, however, put up desperate resistance in hand-to-hand combat. After a long battle, the Tekins fled through the northern passes, with the exception of a part that remained in the fortress and was destroyed while fighting. Skobelev pursued the retreating for 15 miles. The Russians lost 1,104 people during the entire siege and assault, including 34 officers. Inside the fortress, 500 Persian slaves and trophies valued at 6,000,000 rubles were taken.

Soon after the capture of Geok-Tepe, detachments were sent under the command of Colonel Kuropatkin, who occupied Askhabad (Ashkhabad). As a result, in 1885, the Merv and Pendinsky oases of Turkmenistan with the city of Merv and the Kushka fortress voluntarily became part of the Russian Empire.

January 14 M.D. Skobelev was promoted to general from the infantry, and on January 19 he was awarded the Order of St. George, 2nd degree.

On April 27, he left Krasnovodsk for Minsk. There he continued to train troops. In the art of war M.D. Skobelev adhered to progressive views, was an adherent of the idea of Slavic brotherhood, and spoke out in defense of the Balkan peoples against the aggressive policies of Germany and Austria-Hungary. He had deep knowledge of military affairs and the rare ability to lead troops to a true feat of arms, as was the case at Lovnya, Sheikovo and Geok-Tepe. From the general from the infantry M.D. Skobelev had a great future - he was even called “the second Suvorov,” but his premature death deprived Russia of a talented commander.

M.D. Skobelev near Geok-Tepe

M.D. Skobelev in battle

M.D.'s grave Skobeleva

Monument to M.D. Skobelev in Bulgaria

Bust of M.D. Skobelev in Ryazan

On September 29, 1843, the outstanding Russian military leader Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev was born.

The legendary commander Mikhail Skobelev, with whose name many brilliant victories of Russian weapons are associated, was born on September 17 (29), 1843 in the Peter and Paul Fortress, of which his grandfather was the commandant. Skobelev was a third-generation military man; his grandfather and father rose to the rank of general.

In his youth, Mikhail intended to devote himself to civil service and entered the mathematics department of St. Petersburg University, however, his studies had to be interrupted. The university was closed due to student unrest, and Skobelev, heeding his father’s advice, petitioned the emperor to enroll as a cadet in the elite Life Guards Cavalry Regiment.

Military service began with the oath and kissing the cross, according to the description given by the leadership, Junker Skobelev “serves zealously, not sparing himself.” A year later he was promoted to cadet harness, six months later to the junior officer rank of cornet, and in 1864 Skobelev participated in the suppression of the uprising of Polish rebels. He was included in the retinue of Adjutant General Eduard Baranov, but being burdened by his retinue duties, he begged the general to send him to the combat sector. Skobelev received his baptism of fire in a battle with the Shemiot rebel detachment, and was awarded the Order of St. Anne, IV degree, for his bravery.

Participation in the Polish expedition confirmed the correctness of the chosen path; subsequently Skobelev repeatedly repeated: “I am where the guns thunder.”

In 1866, he entered the Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff. The defeat in the Eastern War forced the government to reconsider its approach to military education, now officers were trained according to a new program, and future military leaders left the Academy with a thorough knowledge base.

As one of the best graduates, Mikhail Dmitrievich is sent to the General Staff. After a short period of “paper” work in the General Staff, Skobelev showed himself in Central Asia; in 1873 he became a participant in the Khiva campaign, the general leadership of which was carried out by General Konstantin Kaufman. Skobelev commanded the vanguard of the Mangyshlak detachment (2,140 people), in difficult conditions, in almost daily skirmishes with the Khivans, his detachment approached the capital of the khanate in May 1873.

On May 29, Khiva fell, the first decree that the khan was forced to issue was a ban on the slave trade, because one of the goals of the expedition was to suppress the slave trade. Russia, as Engels, who was stingy with positive assessments of the “tsarist regime,” noted, played “a progressive role in relation to the East... Russia’s dominance plays a civilizing role for the Black and Caspian Seas and Central Asia...”.

Due to strong opposition from the British, the Russian government failed to implement the initial plan to establish good neighborly relations with the Central Asian states peacefully, so military measures were used. Skobelev will subsequently repeatedly perform this responsible role of enforcing peace.

Already in 1875, after a short business trip to Spain, Skobelev led a campaign to suppress the rebellion that broke out in Kokand. A Russian detachment of only 800 people with 20 guns near the village of Makhram entered into battle with the 50,000-strong army of the usurper Khudoyar. Despite the huge numerical superiority, the Russians scattered the enemy and put him to flight. Skobelev’s formula “It’s not enough to be brave, you need to be smart and resourceful” worked flawlessly.

N.D. Dmitriev-Orenburgsky “General M.D. Skobelev on horseback”, 1883

In October 1875, Mikhail Dmitrievich was promoted to major general, and in February of the following year he was appointed governor-general of the newly formed Fergana region. With his characteristic zeal, Skobelev began to develop the region and in this post proved himself to be a skilled diplomat. He dealt with the local nobility and warlike tribes “firmly, but with heart.”

He understood that military force alone was not enough to establish Russia’s authority, so he was actively involved in solving social issues. On Skobelev’s initiative, a city was founded, which later received the name Fergana and became the regional center of Uzbekistan; the governor-general took a personal part in its design.

Having learned about the start of the war with the Ottoman Empire, Skobelev, using his connections in St. Petersburg, changed the relatively calm office of the governor-general to a battlefield more familiar to him. Participation in the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878 became the peak of Mikhail Dmitrievich’s military career and at the same time was the realization of his life credo: “My symbol is short: love for the Fatherland, science and Slavism.”

The Russian army owes Skobelev’s talent the capture of the strategically important city of Lovech, and it was he who became the true hero of the third assault on Plevna.

Thanks to the efforts of Skobelev, the battle of Sheynov was won, when a crushing blow by the Russians paralyzed the actions of the 30,000-strong army of Wessel Pasha. General Skobelev personally accepted the surrender of Wessel Pasha and his army.

In battle, the general was always ahead of the troops in a white jacket and on a white horse. “He believed that he would be more unharmed on a white horse than on a horse of a different color...”, explained this choice by artist Vasily Vereshchagin, who was well acquainted with Skobelev.

Skobelev’s detachment captured Adrianople and the town of San Stefano, located 20 kilometers from the Turkish capital. It was just a stone's throw from Constantinople.

Of course, Skobelev, who shared the views of the Slavophiles on the historical mission of Russia to liberate Constantinople from Muslims, which at the same time was the cherished dream of the Slavs and Greeks, was eager to begin the assault on this city.

The brilliant strategist saw that the historical moment was close, “... the presence of an active army in Adrianople and the opportunity... and now to occupy the capital of Turkey in battle,” he noted in one of the letters. But diplomacy decided otherwise; the war ended with the signing of the Treaty of San Stefano.

The name of the “White General,” as both Russians and Turks called him, thundered throughout Europe. After the signing of peace, Skobelev took personal initiative on the issue of organizing capable paramilitary units in Bulgaria, called gymnastic societies. The Bulgarians, for their efforts to liberate Bulgaria from the Turkish occupiers and help in the post-war development of the country, ranked General Skobelev among their national heroes.

Vyacheslav Kondratyev “Plow up Geok-Tepe!”

After the war with the Ottomans, the general will lead the Akhal-Teke expedition, which became a matter of special national importance. Skobelev turned out to be the only one who combined the talents of a military leader and the wisdom of a diplomat. The emperor himself had a confidential conversation with the general regarding this expedition. It was successful, the last source of unrest was eliminated, and peace was established in the Trans-Caspian possessions of Russia.

The general was always on the front line during hostilities. Even during the war with the Turks, soldiers composed a song about their commander, which contains the following lines:

I was not afraid of enemy bullets,

Not afraid of a bayonet,

And more than once near the hero

Death was already close.

He laughed at bullets

Apparently, God protected him.

He was wounded many times, but the bayonet and bullets did not harm his life. Skobelev did not die in war, but under other very mysterious circumstances. The causes of death, which occurred on June 25 (July 7), 1882, remained undisclosed; various versions of what happened are still being put forward. A countless number of people came to see off Mikhail Dmitrievich on his final journey.

The Russian general devoted his short but bright life entirely to the Fatherland.

Kirill Bragin

The outstanding Russian military leader, national hero of the Bulgarian people Mikhail Skobelev was born in St. Petersburg 172 years ago - September 29, 1843.

Fate decreed that the “white general”, who received this nickname for the light robe that he wore during numerous battles, was awaited by early glory, mysterious death and complete oblivion.

“Tremble, Asians!”

The name of General Skobelev enjoyed incredible popularity in all layers of Russian society. During his lifetime, squares and cities were named after him, and songs were written about his exploits and campaigns. The portrait of the “white general” hung in almost every Russian peasant hut, near the icons.

Popularity came to the general after the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-78 to liberate the fraternal Balkan peoples from the Ottoman yoke. Not a single military leader in Russian history has received such popular adoration.

Skobelev faced fame during his lifetime and complete disappearance from history under the Soviet Union. Photo: Public Domain

Mikhail Skobelev was born in the Peter and Paul Fortress. As a child, he was raised by his grandfather Ivan Nikitich Skobelev, the commandant of the main fortress in the country. He was a retired military man, a hero of the battle of Borodino and Maloyaroslavets, and took Paris. It is clear that his grandson, like most noble offspring, was prepared for military service from childhood.

Later, Mikhail went to study in France. The young man spoke eight languages, and spoke French no worse than Russian. In 1861, Skobelev entered St. Petersburg University, but subsequently the craving for military affairs overpowered him - the young man went to serve at the Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff. Unlike many officers who preferred playing cards and carousing to science, Skobelev read a lot and educated himself.

Skobelev received his first serious baptism of fire during the campaign of Russian troops against Khiva in the spring of 1873. The Russian state made an attempt to deal with the center of the slave trade in Central Asia. For a century and a half, the Khanate of Khiva was a market for Russian slaves. Since the time of Catherine II, huge amounts of money have been allocated from the budget to ransom their subjects from Asian captivity. Russian slaves were highly valued because they were considered the most hardy and quick-witted workers. And for a beautiful young woman they sometimes gave up to 1 thousand rubles, which was a colossal sum at that time.

During skirmishes with the enemy, Skobelev received five wounds inflicted by a pike and a saber. With a detachment, he advanced 730 versts through the desert and took Khiva without a fight. More than 25 thousand slaves were immediately freed.

Hot and glorious time

Skobelev was not afraid to personally conduct reconnaissance in enemy territories. He dressed in the clothes of commoners and went on forays. Thus, he earned his first St. George Cross when he studied the route in detail among hostile Turkmen tribes. Later, he also went to Constantinople, studying the preparation of Ottoman troops for the defense of the city.

“General M. D. Skobelev on horseback” N. D. Dmitriev-Orenburgsky, (1883). Photo: Public Domain

Contemporaries admitted that the commander received all his awards and distinctions not through patronage, but through battle, showing his soldiers by personal example how to fight. In 1875, Skobelev’s troops defeated the 60 thousand army of Kokand rebels, their number was 17 times greater than the number of Russian troops. Despite this, the enemy was completely defeated, our losses amounted to six people. For these military successes, Mikhail Dmitrievich, at the age of 32, was awarded the rank of major general.

Thanks to the leadership of the young general, slavery and child trafficking were abolished everywhere in Central Asia, post and telegraph appeared, and construction of the railway began.

In 1876, a popular uprising broke out in Bulgaria against the Ottoman yoke. Hundreds of Russian volunteer doctors and nurses went to the Balkans. The uprising was drowned in blood, Turkish troops massacred tens of thousands of Bulgarians. Cities were turned into piles of ash, priests and monks were beheaded, babies were thrown into the air and caught on bayonets. Emperor Alexander II was shocked by the cruelty of the Ottomans. Skobelev could not stay away from these bloody events and in 1877 he returned to the active army. He took part in many battles, later becoming the liberator of Bulgaria.

“A hot and glorious time began, all of Russia rose in spirit and heart,” Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky wrote about those events.

Father to soldiers

Skobelev’s bravery and courage were combined with the foresight and prudence of an experienced military leader. Little things relating to a soldier's life did not escape his attention. Not a single subordinate of the “white general” died from frostbite during the trek through the mountains. He forced everyone to take at least one log with them. And when other soldiers were freezing because they could not make fires, Skobelev’s soldiers were warmed and fed with hot food.

Skobelev did not hesitate to talk with ordinary soldiers; he ate, drank, and slept with the privates. In these qualities, the general was very similar to another great Russian commander, Alexander Suvorov.

Skobelev's most famous exploits in the Russian-Turkish war were the defeat and capture of the entire army of Wessel Pasha and the capture of two fortresses during the assault on Plevna. The general himself led his soldiers under heavy enemy fire.

In total, more than 200 thousand Russian soldiers and officers died during the Russian-Turkish war for the liberation of the Balkan Slavs.

Disappeared from history

Skobelev became the first governor of liberated Plevna. There he met with the Emperor of Russia, who highly appreciated the merits of the commander. After this war, the “white general” became very famous in the country. In 1880, Skobelev took part in the Akhal-Teke expedition. Then, with a detachment of seven thousand people, he took the enemy fortress with a fourfold superiority of the defenders.

Mikhail Skobelev died at the age of 38 under mysterious circumstances. Having received leave, he arrived in Moscow, where, as usual, he stayed at the Dusso Hotel. After several business meetings, I went to the Angleterre Hotel, where ladies of easy virtue lived. In the middle of the night, one of them ran to the janitor and reported that an officer had suddenly died in her room. The cause of death of the fearless commander is still unclear. It was rumored that German intelligence took part in the elimination of the brilliant military leader. The doctor who performed the autopsy stated that death was the result of sudden paralysis of the heart, which was in a terrible state. The general's death shocked all of Russia; his funeral turned into a national event.

After the October Revolution, all the gains of autocratic Russia began to be erased from history. In 1918, the monument to Skobelev in Moscow was barbarically destroyed on Lenin’s personal order. In accordance with the decree on the “removal of monuments erected in honor of the kings and their servants.” All bronze figures and bas-reliefs were sawn, broken into pieces and sent for melting down. And the granite pedestal was simply blown up.

Immediately, Soviet historians, with great zeal and pleasure, declared the general an enslaver and oppressor of the working masses and fraternal peoples of the East. In place of the destroyed monument to the general, a plaster monument to revolutionary freedom was erected. Subsequently, a monument to Yuri Dolgoruky appeared here.

There are names in our history of outstanding people who were true patriots of their country and served it faithfully. Not out of fear, but out of conscience, and for the prosperity of Russia they did not spare their lives. Their activities were not fully appreciated during their lifetime, but it is a shame to realize that we turn out to be ungrateful descendants and honor their memory even less. The bright, heroic and tragic life of Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev - an infantry general, a fearless commander, a hero of many wars, a participant in seventy battles - is a true example of sincere patriotism and faithful service to the Fatherland.

By association with the nickname that Skobelev bore in Russian society, “White General,” many who are new to history classify him as a participant in the white movement, although Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev is a hero of Russian history of the 19th century.

Brief biography of General Skobelev

He was born in 1843 into a family of hereditary military men. In his family, men always served the Fatherland. His grandfather was an orderly with himself, his father fought in the Caucasus and successfully participated in the Turkish campaign. Mikhail Skobelev was a very gifted young man who was destined for a career as a scientist, not a military man. Few people know, but Skobelev spoke eight European languages.

Born in St. Petersburg, he spent his teenage years in the Girard boarding house. Returning home at the age of 18, he entered St. Petersburg University in 1861, but soon left his studies and was enlisted as a cadet in the Cavalry Regiment, and in 1863 he was promoted to cornet. In 1864, the young cornet Skobelev received a baptism of fire during the Polish uprising. The battle in the Radkowice Forest and the miracles of courage shown allow him to receive his first order - St. Anna 4th degree.

Skobelev is transferred from the cavalry guards to the hussar regiment. He very successfully graduates from the General Staff Academy and serves for some time in the Moscow Military District. But the boring staff life is not for him, and he goes to the Caucasus and Turkestan. In 1873, Mikhail Dmitrievich distinguished himself during the capture of Khiva, and from that time on he began to wear an exclusively white uniform. He also only rode white horses, so his opponent called him Ak Pasha, that is, “white commander.”

For his participation in the Kokand expedition, where Skobelev showed not only courage and courage, but expressed the prudent foresight of a diplomat, organizational talent and excellent knowledge of local customs when communicating with the Asian population, he was awarded two Orders of St. George III and IV degrees, Order of St. Vladimir and a golden sword with a diamond hilt and the inscription “For bravery.” Having received the rank of colonel, in 1877 he became the governor of New Margelan, and at the same time, the commander of the troops in the Fergana district. But almost immediately Skobelev received a new appointment and served at the disposal of the commander-in-chief army to participate in the European coalition against Turkey.

At first, the new colleagues looked at the young general as an upstart who received a high rank and awards for the victory over the “wild Asians.” But the successful operations of Russian troops under the command of Skobelev during the capture of Lovchi and in the battles near Plevna, the victorious breakthrough of Skobelev’s troops through the Imetli Pass in the Balkans, the famous battle of Sheinovo, when Russian troops captured ancient Shipka and dealt the final blow to the Turkish troops - all these operations were among the victories of Russian weapons under the command of General Skobelev. They brought him glory, fame, admiration and worship.

Skobelev returns to Russia as a corps commander with the rank of lieutenant general. And Skobelev’s last military feat was the capture of the Ahal Tepe fortress in Turkestan in 1881. For this victory he received the Order of St. George II degree and the rank of infantry general. Returning from the expedition, Skobelev goes abroad. He does not hesitate to make speeches out loud about the oppression of his brothers - the Slavs - by civilized European countries - Germany, Austria and receives another nickname "Slavic Garibaldi." The government recalls the rebellious general from leave to his homeland and, as a result of an accident, Skobelev suddenly dies on June 26, 1882 .

- They spoke of him as a charmed hero who was under the care of the Mother of God - he emerged from any battle without a single scratch. The same applied to his soldiers - the losses in his troops were the smallest.

- Yakov Polonsky wrote on Skobelev’s death:

Why are people standing in a crowd?

What is he waiting for in silence?

What is the grief, what is the bewilderment?

It was not a fortress that fell, not a battle

Lost, Skobelev has fallen! gone

The force that was more terrible

The enemy has ten fortresses...

The strength that the heroes

Reminded us of fairy tales. ...

Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev was born in 1843 into a military family. Skobelev received his education at a French boarding school and continued it at St. Petersburg University. According to the testimony of contemporaries, Mikhail Dmitrievich could not be called an exemplary student. He either demonstrated brilliant knowledge, or abandoned his studies and devoted himself entirely to student merry parties. Skobelev might not have completed his studies if Professor Leer had not taken him under his protectorate. He saw enormous potential in the young man. At his request, young Skobelev was included in the staff of officers of the General Staff.There is a legend associated with Mikhail Dmitrievich’s youth that explains why he always rode to the battlefield on a white horse. According to it, during training he was sent to the shore of the Gulf of Finland to survey the area. One day he went into the forest and got stuck in a swamp. A local peasant hastened to Skobelev’s rescue. He brought a white nag to help Mikhail Dmitrievich get out of the trap. At that moment, Skobelev promised that in tribute to the memory of his savior he would always choose a white horse. He always appeared on the battlefield or at parades in a white uniform. It was rumored that the general was charmed by bullets. Skobelev himself, according to some sources, believed that dressed in all white and not a horse of the same color, he would always remain invulnerable to enemies.

Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev always appeared on the battlefield or at parades in a white uniform and on a white horse // Photo: Defendingrussia.ru

Already in 1863, Mikhail Skobelev became an active participant in the suppression of the Polish uprising, and in 1873 he went on the Khiva campaign, which brought him his first great fame.

Mikhail Skobelev became a generally recognized hero after the Russian-Turkish War of 1877–1878. He distinguished himself during the formation of the Danube, the capture of Plevna and other high-profile battles of that war. As the general's biographers note, he always paid attention to his soldiers and cared very much about them. The general emphasized that he owed all his victories to the common soldier and therefore would do everything in his power to make his conditions of service as comfortable as possible. For this, the soldiers loved Mikhail Dmitrievich, which cannot be said about his fellow officers. They were jealous of Skobelev's fame and weaved intrigues around him. So, Mikhail Dmitrievich was accused of embezzling government money, “wrong” political views, and the like.

But despite all this, Mikhail Skobelev continued to remain one of the most respected people in the Russian army.

Political Views

Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev was an adherent of Slavism and Orthodox values. But on the other hand, he did not like the idea of the need to return to pre-Petrine Rus'. When the struggle for influence in Asia intensified between the Russian Empire and Britain in the second half of the 19th century, Skobelev received an order to capture the Geok-Skobele fortress on the territory of modern Turkmenistan, which he did brilliantly. In addition, he played a key role in the annexation of most of the regions of Turkmenistan to the Russian Empire.

Mikhail Skobelev played a key role in the annexation of most of the regions of Turkmenistan to the Russian Empire // Photo: Pravera.ru

In 1882, Mikhail Dmitrievich was granted an audience with Emperor Alexander III. The enemies of the “white general” hoped that the tsar would besiege Skobelev and their conversation would be very unpleasant, because recently Mikhail Dmitrievich’s political rhetoric had become more acute. He argued that a serious threat awaits Russia, and it comes from the West, namely from Germany. Such speeches caused a stir in Europe and could cause a serious international scandal.

But Mikhail Dmitrievich’s haters were disappointed. After an audience with the king, he further strengthened his own position.

The mysterious death of the “white general”

On June 22, 1882, Mikhail Skobelev went to the England Hotel, where he had an appointment with the famous cocotte Charlotte. At night, a frightened woman ran to the janitor and said that an officer had died in her bed. Thus ended the glorious life of the “white general” Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev.The official cause of death was paralysis of the heart and lungs, but since censorship carefully erased all information about Skobelev’s death from the newspapers of that time, it became overgrown with the most incredible theories.

The official cause of death of Mikhail Skobelev was named paralysis of the heart and lungs // Photo: Ytimg.com

Medical conclusion

According to doctor Skobelev, already during the Turkestan campaign he discovered the first signs of heart failure in the general. As a result of several examinations, the doctor concluded that Mikhail Dmitrievich’s cardiac muscles and his entire cardiovascular system were rather poorly developed. But at the same time, Skobelev never complained about his health, was very hardy and endured long marches absolutely without complaint.By the way, the doctors who performed the autopsy of the “white general” said that his heart looked like the heart of a decrepit flock, although Mikhail Dmitrievich was only 38 years old at the time of his death.

Conspiracy theories

As Prince Dmitry Obolensky, a close friend of Mikhail Dmitrievich, recalls, a couple of days before his death, Skobelev was very gloomy and said that he had no more than three years to live, and also drank a lot. In addition, the general was morally depressed due to the murder of his mother and Emperor Alexander II, whom he treated with great respect.According to one theory, Germany was involved in Skobelev’s death. Mikhail Dmitrievich has repeatedly called for fear of this Western state. What seems ambiguous in her light is that Skobelev died in the rooms of the cocotte Charlotte, who arrived from Austria-Hungary. Although the police later denied the woman’s involvement in the general’s murder, she was given the nickname “Skobelev’s grave” almost until the end of her life.

Contemporaries of Mikhail Dmitrievich did not exclude the possibility that the general was killed on the orders of the tsar. Allegedly, Alexander III feared that the incredibly popular Mikhail Dmitrievich would decide to take the throne himself and succeed in this matter. Adherents of this version are confident that the general’s death occurred after he drank a glass of wine sent from the next room.

These versions are the main ones and have the largest number of adherents. Unfortunately, the true cause of the death of Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev cannot be determined unambiguously, because history knows how to keep its secrets very well. But due to many inconsistencies and strange circumstances, few people doubt that Skobelev’s death is related to the crime.

Historians can only guess and look forward to an opportunity that could reveal new facts that will shed light on the mysterious and sudden death of the “white general.”