MY MEMORIES

BOOK ONE

CHAPTER FIVE

WAITING FOR FURTHER EVENTS

(November- December 1914)

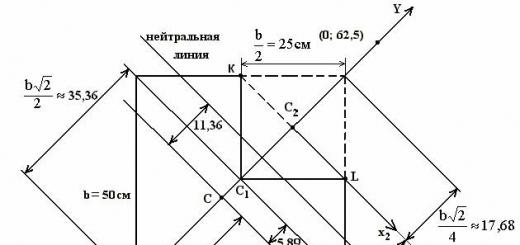

(Drawings IV and VI)

Given the likelihood of a threat to the Kilimanjaro region from the enemy, I considered it necessary, after a decisive engagement at Tanga, which still could not be used more widely, to quickly transfer troops back to the Neimoshi region. The joy of the colonists of the Northern Region, who made up the majority of the Europeans who fought at Tanga, was indescribable. Decorated with flowers, the first train with Europeans approached Neimoshi again. I still had enough to do with Tanga, and only a few days later I arrived at the Neimoshi station, where the command again set to work. With a shortage of personnel, we could not afford to constantly have separate people to perform various duties. Just as a staff officer had to turn into a shooter or a cyclist if necessary, so the quartermaster had to be an orderly, and a clerk to shoot in battle and work as a messenger. It was a great relief for the staff work that we were located in the building of the Neimoshi station, built in a European way, where, despite the great crowding inside the headquarters, we could quickly resolve most issues through personal negotiations. We had good telephone and telegraph equipment and were at the center of telephone and telegraph lines in both directions - both to Tangu, Tavetu, east and west of Kilimanjaro, to Longido, and to Arusha - which we rebuilt or improved where they already there were. There were weeks when our official activities were carried out almost as in peacetime, although at an increased pace of work. Although almost no one in the headquarters was familiar with or prepared for headquarters activities, nevertheless, the common work was carried out harmoniously and successfully. It was supported by high aspirations, love for the cause and comradely soldering.

I went by car - after all, we also built a road for ourselves to Longido - to the Engare-Nerobi (cold river) located between Longido and Kilimanjaro, a small river that crosses the steppe from the northern slopes of Kilimanjaro in a northwesterly direction. Several Boer families lived there on their farms. Kraut's detachment moved their camp here, since the supply of food to Longido during a two-day march across the steppe could not be protected from attack, and therefore was too risky. I was convinced that also here, north of Kilimanjaro, military operations could not be expected at the present time, and I returned to Neimoshi. The road from Neimoshi, where the bulk of the food supplies from Uzambara and from the regions further south were concentrated by rail, is 50 kilometers to Taveta. Although we had at our disposal a small number of cars, namely only 3 cars and 3 trucks, but even this number in our conditions brought significant benefits. In dry weather, on a well-equipped road, three-ton trucks could freely travel from Neimoshi to Taveta and back, while porters needed at least 4 days to do this. Thus, this calculation shows that one car can provide the same work as 600 porters, who also need food themselves.

One cannot but agree with the decision, which the British later adhered to, to remove the carrying of goods from the shoulders of porters and animals and replace them with cars, especially since people and animals suffered greatly from tropical diseases, while mosquitoes were completely powerless against the car. But we could not use this clear advantage, as we had only a limited number of cars. We had to constantly resort to porters, even in this convenient for the supply of food, a calm period of the war. Even now I remember the joy of the then quartermaster when a caravan of porters at 600 Vassokum arrived from Muanza to Neimoshi. They brought rice from Lake Victoria via Kondoa-Irangi to Kilimanjaro, which was in dire need here. Bearing in mind that the porter during this march, which took at least 30 days, himself eats a kilogram of food daily, and carries a maximum of 25 kilograms, marches should be organized very deliberately and take place mainly in populated and food rich terrain, so that in general such a method of transportation would represent a certain benefit. If, in spite of these shortcomings, the carrying of goods by porters was used on a large scale, this indicates the difficulties in the supply of food with which we had to reckon.

The quartermaster, Captain Failke, knew how to treat people well and take care of them. The porters felt good, and the word "command", which some considered a proper name, became very popular. Personally, the two available vehicles made it possible for me to carry out numerous reconnaissance of the area, as well as inspect the troops. At 2 o'clock I could drive from Neimoshi to Taveta, where part of the troops from Tanga had returned. With another method of transportation, it would take 4 days to do this. Later, in one day, I traveled from Neimoshi to Engara-Nerobi and further west around the whole of Mount Meru, and then back to Neimoshi, a journey that, perhaps, with porters could not have been done in less than ten days. The success at Tanga aroused the determination of the entire colony to resist.

On November 26, the head of the transit service, Major General Vale, managed to get the consent of the governor in Morogoro to defend Daresalam in the event of an attack. Fortunately, this consent was given just in time. Already on November 28, 2 warships, a transport ship and a tugboat appeared at Daresalam, and demanded an inspection of our ships lying in the harbor. Here, among the other ships, there was the steamer of the German-African line "Tabora", equipped as an infirmary. Since the British had declared even earlier that they did not consider themselves bound by any agreements regarding Daresalam, a new agreement would be required each time if they wanted to avoid shelling. Thus, an endless story was obtained. I telephoned that the demand to let a large English armed launch into the harbor should now be resisted by force of arms. Unfortunately, the German authorities, in an incomprehensible way for me, agreed to this visit to the boat, and the senior officer who was in Derasalam felt bound by this. When the British, instead of one authorized boat, brought several smaller ships into the harbor, destroyed the Tabor and even captured the personnel of this steamer, to everyone who still hesitated, it became quite obvious all the futility of our compliance. Captain von Kornatsky arrived just in time to successfully take the small English ships under machine-gun fire as they passed through the narrow northern fairway on their way out. At the same time, unfortunately, one of the German prisoners was also wounded. Protective measures were not taken in time. This may serve as a small example of how dangerous and ultimately disadvantageous it is when, during a war, a military leader is constantly interfered with in carrying out his plans and necessary measures.

However, the subsequent shelling of Daresalam did not cause any significant harm, since only a few houses were damaged.

The period of comparative inactivity in which we found ourselves in Neimoshi was economically favorable. The Europeans, who for the most part belonged to the colonists of the northern region, supplied themselves with the main types of their food; rice, wheat flour, bananas, pineapples, European vegetables, coffee and potatoes flowed generously from the plantations to the army. Sugar was extracted from numerous factories, and salt was mainly delivered from the Gottorp saltworks, located near the Central Railway between Tabora and Tanganaika. Many plantations devoted their entire production to supplying the army, and with a large number of laborers, the cultivation of these plantations presented no difficulty.

However, transportation had to be arranged. The large stage road leading from Kimamba to the Northern Railway (to Mombo and Korogwa) was lengthened all the time in order to be able to bring products north from the Tanganaike railway area and from more southerly areas. At least 8,000 porters were permanently employed on this site alone. It soon became clear that it was more profitable not to let the caravans of porters cover all this distance at once, about 300 kilometers long, but to distribute the porters in separate stages. Then it was possible to establish permanent parking for them, as well as monitor their health. The orderlies went around the stages and did everything in human power to protect the health of the porters, fighting mainly against dysentery and typhoid. Thus, on this busy stage road, permanent camps of porters arose at a distance of a day's march, in which people were placed first in temporary, and then in well-built huts. Strict camp discipline was established. In caring for the numerous visiting Europeans, small houses with concrete floors were arranged for them; those who followed a single order had the opportunity to be content here from the supplies of the stage, instead of, as is customary with African travels, being forced to drag with them all the food supplies for a long time. Work on this milestone road has been the subject of constant attention; Europeans and coloreds had to learn first how to work together with such a large mass of people and understand the importance of order and discipline for the delivery service and for the health of all participants.

At the Neimoshi station, the telegraph and telephone worked around the clock. In rebuilding the entire organization, it was impossible to do without friction. All persons belonging to the headquarters were extremely overworked. However, in hard work there were also light moments. Material assistance from the Europeans here in the north was also provided to our headquarters. We were directly spoiled by numerous parcels from private individuals. When one of us traveled on the Northern Railway, on which in peacetime it was difficult, despite money and increased requests, to get ourselves a little food, now at almost every station someone took care of us. I recall one case when Lieutenant von Schrotter, greatly exhausted by the reinforced intelligence service, returned to the headquarters in Neimoshi from the region of the northern mountain Erok. After he seemed to have been well fed from 7 to 11 o'clock, he shyly asked to be given another supper after all. The next day, he went on a 14-day vacation to his plantation located in Usambara to rest and recover. After breakfast, we gave him coffee, bread, butter and meat to take with us into the car and asked various stations to take care of this completely starving scout. Thus, after half an hour in Kakha, breakfast was again served to him by the station guard there; in Lembeni, the dear wife of the local station commandant baked him a cake, and in Sam, the head of the local recruiting depot, Sergeant Reinhard, took care of him. In Makandzha, the colonist on duty, Barry, brought him chocolate made with his own hands and a "bull's heart" - these are fruits about the size of a melon. In Buiko, the hospitable head of traffic of the Northern Road, Külvein, who so often supported us on our journeys, cooked him a magnificent meal. At Mombo, where supplies flowed from the Usambara Mountains and where we mainly set up our army workshops, Naval officer Meyer was waiting for our lieutenant with a hearty supper. But then we received a telegram: “Please do not order anything else. I can not do it anymore".

As far as this prolonged concern shows a sympathetic joke on the mood of a hungry lieutenant, such concern is better than abstract reasoning is indicative of the mutual internal adhesion of all parts of the population of the Northern District with the troops and the desire to catch our every desire in our eyes. This mutual connection did not weaken while the troops were in the North.

When the service allowed it, we did not forget about entertainment and recreation. We often gathered on Sundays in the vicinity of Neimoshi for a merry round-up. The porters and askaris soon realized their role as beaters and, in exemplary order, drove game towards us through the thickest bushes, about which they warned with loud cries of “Khuju, huju” (“here he is, here he is”). As for the diversity of game in this area, this can never be found hunting anywhere in Europe: hares, various pygmy antelopes, guinea fowls, various genera of partridges, ducks, artisanal and waterbucks, lynxes, various breeds of wild pigs, jackals and many other game. I remember that one day, to my amazement, a lion silently appeared 15 paces in front of me. Unfortunately, I had a hunting rifle in my hands, and while I managed to get the rifle lying on my knees ready, he disappeared just as silently. Hunting in the rich game region of Kilimanjaro and still further east of Taveta gave us a pleasant variety in our meat diet. The main supply of meat was based on bringing herds of cattle for the troops from the regions of Kilimanjaro and Meru, as well as from afar from the regions adjacent to Lake Victoria.

CHAPTER SIX

AGAIN HARD FIGHTS IN THE NORTH-EAST

(Drawing VII)

When we were celebrating Christmas 1914 in Neimoshi, in our canteen at the station, the military situation north of Tanga began to become so aggravated that a decisive enemy offensive became probable there. Our patrols, which were here on British soil, were gradually pushed back in the last days of December and concentrated on German territory, south of Jassini. Here 2 companies and a detachment formed of about 200 Arabs joined. The enemy, apparently, intensified and occupied the buildings of the German plantation of Yassini.

The impression was that he was trying to break through to Tanga with a gradual offensive along the coast and provide the area occupied by him with a system of blockhouses. In order to familiarize myself with the state of affairs on the spot, in mid-January, together with Captain von Hammerstein, I went to Tangu, and then in a car along the newly built new road, 60 kilometers long, which went north along the coast, to the camp of Captain Adler at Mvumoni. On reconnaissance, I was accompanied by Lieutenant Black, who was very useful due to his many successful reconnaissance searches in the area. The area in the vicinity of Yassini consisted mainly of German East African Society coconut plantations about a mile long, planted with sisal, an agave plant with sharp thorns. This sisal formed a dense undergrowth between the trunks of the coconut palms, and in many places was so closely intertwined with its thorny leaves that it was possible to get through it only after experiencing many very unpleasant pricks. It is always difficult to make a combat decision in such unfamiliar terrain, which can only be judged by patrol reports, due to the lack of basic cartographic data. Now these difficulties could be eliminated by the fact that an old plantation employee, a lieutenant of the reserve Schaefer, who was drafted into the army, could give accurate information. A tolerably executed plan was drawn up, provided with military names. In general, it seemed that at Yassini it was a matter of an advanced post and that the main enemy forces were still further north in a fortified camp. It could be assumed that an attack on the post at Yassini would lure the enemy out of the camp and induce him to fight in the open field. I decided to use this position, and in order to create the most favorable tactical situation for fighting the enemy moving from his camp to the rescue of the post at Jassini, I had in mind to keep units ready in the path of the enemy’s probable attack so that he, for his part, should have faced us.

The collection of food in this densely populated area met with no difficulty, and the required number of porters could be taken from the numerous European plantations. Thus, during the transfer of companies called here by telegraph from Neimoshi, only porters for machine guns and ammunition had to follow with them, which represented a significant relief for railway transport.

The transfer proceeded quickly and without friction, thanks to the tried and tested foresight of the commandant of the line, Lieutenant Kroeber, and also thanks to the understanding of the situation and the ardent zeal with which all the personnel of the road meekly endured the inevitable tension.

On January 16, the companies arriving from Neimoshi were landed a few kilometers west of Tanga and immediately sent in marching order to Yassini. Units from Tanga were also moved there, where only one company remained for direct protection. On January 17, in the evening, military forces, a total of 9 companies with 2 guns, were assembled 11 kilometers south of Yassini, at the Totokhovu plantation, and an order was given to attack the next morning. Major Keller was appointed with two companies to cover the right, and Captain Adler, with the next two companies, was to cover the enemy on the left, near the village of Yassini. The Arab detachment was located to the northwest on the road coming from Semandzhi; Captain Otto advanced with the 9th company from the front along the main road to Jassini. He was immediately followed by the command, and then the main force, consisting of a company of Europeans, three companies of askari and 2 guns. The movement was calculated so that at the first glimpse of morning, a simultaneous attack on Jassini should follow, and all the columns should mutually support each other with a vigorous forward movement. Even before dawn, the first shots were fired in the Kepler column, a few minutes later the fire also began in front of us in the Otto column, and then flared up along the entire front. It was impossible, in the absence of any view and the endless palm forest, to form even an approximate picture of what was actually happening. But we were already so close to the enemy position at Jassini that the enemy seemed taken by surprise, in spite of his advanced guard. This assumption was confirmed later, at least in part. Indeed, the enemy had no idea of our rapid concentration south of Jassini and of the attack immediately followed by such a large force.

Otto's detachment quickly threw back the enemy's fortified post in front of him, and the command went to the left, through the forest, along with the outflanking column, which was first assigned to one, and then the next two companies for the bypass movement to Yassini. At the same time, it was striking that we came under well-directed fire at close range, probably no more than 200 meters, and only much later it was possible to find out that the enemy had not only a weak post in Yassini, but that they sat down in a well-camouflaged fort solid construction of 4 Hindu companies. Captain von Hammerstein, who was walking behind me, suddenly sank: he received a bullet in the lower part of the body. At that time, I had to leave a seriously wounded man in the care of doctors, although his condition worried me greatly. A few days later, the death of this distinguished officer caused a hard-to-recompense loss to our headquarters.

The fight became very strong. Our two companies, despite the fact that both company commanders, Oberleutnants Gerlich and Shpolding, were killed, quickly occupied the strong buildings of the Jassini plantation with a brilliant charge forward and entrenched themselves directly in front of the enemy position. Soon we felt the intervention of the main enemy forces. Strong enemy columns approached from the north of Vanga and suddenly appeared right in front of our companies, which lay at the Yassini fortifications. The enemy made 3 energetic attacks here, but each time was repulsed. New enemy columns also approached from the north and northwest. In a collision with an enemy advancing from the west, the Arab detachment performed its task poorly; even the day before, many Arabs begged me to let them go. Now, when they had to wait for the approach of the enemy, hidden in ambush in a dense thicket in the way of his movement, this tension turned out to be excessive for them. Instead of suddenly opening a destructive fire, they began to shoot blindly into the air, and then took off running. Fortunately, these enemy columns then met both companies of Captain Adler and were driven back with heavy losses. Until now, the whole battle could be characterized as an unstoppable drive forward; even the last reserve, namely the European company, at its insistent request, was put into action. Around noon, the offensive stopped in many places in front of strong enemy fortifications. In fact, we did not have any means to destroy them and could not do anything against these positions. Our field guns, located at a distance of 200 meters, also did not achieve any results. The heat was unbearable, and, as at Tang, everyone quenched their thirst with young coconuts.

I personally went with Lieutenant Black to the right flank to inquire about the situation in Major Kepler's column. At that time I had no clear idea of the position of the enemy, and therefore we again found ourselves in an open clearing with dry sandy soil under well-directed fire. The bullets fell from a distance of 500 meters very close to us, and the clearly visible sand spray made it easy for the enemy to correct their fire. The sand was so deep and the heat so great that only a few steps could be taken at a run or a brisk pace. We had to move, mostly slowly, across an open area and endure this unbearable shelling. Fortunately, the latter did not cause us any serious harm, although the bullet that pierced my hat, and the other through my arm, shows that, in any case, the fire was well-aimed. On their return from the right flank, the thirst and exhaustion were so great that there was a squabble between a few usually friendly people over a coconut, although from those available in huge number trees, it was not difficult to get any number of other nuts. The command again went to the Totokhovu-Yassini road. Next to it was the plantation's narrow-gauge railway, whose wagons carried the wounded incessantly to Totochowa, where an infirmary was set up in European houses. Ammunition—the askari carried about 150 rounds—began to run out, and more and more reports began to come in from the warhead that they could no longer hold on. Slightly wounded and crowds of fugitives flocked to the headquarters - whole units fled or, for various reasons, left the places indicated to them. All these people were collected, redistributed, and thus a relatively combat-ready reserve was obtained. The loaded machine-gun belts were mostly used up, and new cartridges were brought here from Totochowa by overhead railway. The people busy stuffing machine-gun belts attached to the trunks of palm trees worked continuously. It was clear that we had already suffered significant losses. Some expressed a desire to stop the fight, on the grounds that taking possession of the enemy fortifications seemed a hopeless affair. However, when we imagined the predicament in which the enemy was locked up in his fortification, who had no water and was forced to perform all the functions of daily life, crowded in a narrow space under the hot sun and under our fire, it nevertheless seemed possible, with unshakable perseverance on our part, to achieve success in the end. The end of the day and the night passed in ceaseless fighting, and, as always in such an emergency, all sorts of rumors arose. The garrison of the enemy fortification allegedly consists of South African Europeans, outstanding well-aimed shooters; some seem to have picked up their language. And at this time it was still really very difficult to imagine a clear picture. My orderly ombashi (corporal) Rajabu immediately prepared for close reconnaissance, crawled close to the enemy line and was killed there. Blacks, generally very impressionable, were doubly nervous at night in such an emergency, and I repeatedly had to seriously scold people when they blindly fired into the air.

On the morning of January 19, the fire again reached great tension. The enemy, surrounded on all sides, made an unsuccessful sortie and soon after threw out the white flag. 4 Hindu companies with European officers fell into our hands. We all paid attention to the victorious look with which our askari looked at the enemy; I never thought that our blacks could have such an important look.

Both sides were in dire straits and were close to exhausting their nervous energies. This is usually the case in every serious struggle - the askari now understood that it is necessary to overcome the first difficulties in order to gain an advantage over the enemy, which is necessary for victory. I estimated the losses of the enemy at least 700 people; the captured papers gave a clear idea of his strength, which was more than double our own. Judging by the documents, the commander of the troops in British East Africa, General Tighe, who had recently arrived in Vanga, concentrated over 20 companies in Yassini and its environs, which for the most part arrived in marching order along the coast from Mombasa. They were to advance further in the direction of Tangu.

The dispatch of the wounded from Yassini to the hospitals of the Northern Railway took place without delay for several days with the help of cars and rickshaws that ran between the field hospital Totokhovu and Tanga. These rickshaws, small two-wheeled wicker carriages moved by people who in Tang play the role of cabmen, were requisitioned by the medical officers for the transport of the wounded. The enemy withdrew to his fortified camp, north of the state border, a new attack on which promised little success. A small detachment of several companies was left at Yassini to counter the activity of the patrols, which immediately resumed. The main mass of troops was again transferred back to the Kilimanjaro region.

On the way to the landing point on the Northern Railway, the troops had to pass through the Amboni plantation. Here the inhabitants of Tanga prepared food and refreshing drinks from their stocks. After the monstrous labors endured during the operation at Yassini, long and intensified transitions in the withering heat, and after fighting that took place day and night, the small sulfuric stream of Sigi was quickly covered with hundreds of white and black bathing figures. All hardships were forgotten, and the mood rose to the highest limit, when just at that moment, after a long break, news from the homeland was again received by wireless telegraph. They showed us that the news of the fighting at Tanga had only just now been received in Germany, and contained gratitude for the success achieved.

CHAPTER SEVEN

LITTLE WAR AND NEW PREPARATIONS

(February- June 1915)

(Drawings VII and VIII)

Later, from the captured papers, it turned out that the enemy was undertaking the movement of troops from Lake Victoria to Kilimanjaro. Thus, the battle at Yassini really eased the situation of other far-flung regions. This information best of all confirmed the original idea that a strong blow against the enemy at one point was at the same time the best defense for the rest of the colonial territory as well; while the question of vigorous defense of other points of the colonial region was of secondary importance. Notwithstanding this, I gladly welcomed the consent of the Governor, in February 1915, to issue an order that the coastal points should resist the threat of the enemy.

Previous successful encounters have shown that such local resistance may not be unsuccessful even against the fire of ship's guns.

Our blow, carried out by 9 companies, although it led to complete success at Yassini, showed me that such heavy losses that we suffered can only be tolerated in exceptional cases. We had to conserve our strength in order to endure a long war. Of the career officers, Major Kepler, Lieutenants Shpalding and Gerlich, Lieutenants Kaufman and Erdman fell, and Captain von Hammerstein died from his wound.

It was impossible to compensate for the loss of these soldiers by vocation, who made up about a seventh of all available career officers.

Similarly, an expenditure of 200,000 rounds showed me that with the means available I could, at the most, carry out three more similar battles. The necessity came to the fore only in exceptional cases of inflicting large blows, and instead of them to wage, mainly, a small war.

The main idea of constant raids on the Uganda railway could be put forward again, especially since it was still impossible to conduct operations here with large military units. It was possible to reach the railway only after many days of crossing the vast steppe, poor in water and sparsely populated, where, apart from occasional hunting prey, there was very little food. I had to carry with me not only food supplies, but also water. This alone limited the size of the active detachment. For such an expedition through regions poor in local resources and water, a lot of experience is required from the troops, which could not yet be available in the then period of the war. Even a company was too large to cross this steppe, and if, after many days of march, it nevertheless reached the Uganda railway, it would have to turn back again, since it was impossible to organize a proper supply of food. Over time, these conditions improved, thanks to the greater experience of the troops and gradually increasing familiarity with the area, which, in fact, was at first a completely unexplored area.

Thus, there was nothing left but to achieve the intended goal with small detachments - patrols. In the future, these patrols were highly valued. From Engare-Neyrobi, small mixed detachments, from 8 to 10 Europeans and Askaris, skirted the camps of the enemy, who advanced to Longido, and acted on his communications with the rear. Thanks to the booty taken from Tanga, we had telephone sets; these units plugged them into the English telephone wires and waited until larger or smaller enemy units or ox-drawn vehicles passed by. From 30 meters, the enemy was fired upon from an ambush, prisoners and booty were taken, and the patrol disappeared again in the endless steppe.

Thus, weapons, cartridges and all kinds of military equipment were obtained at that time.

One of these patrols established near Mount Erok that the enemy always drives his riding horses to a watering hole at a certain time. Ten of our cavalry quickly gathered and after a two-day journey on horseback across the steppe lay down close to the enemy. 6 people returned with horses, the remaining four made reconnaissance, then each took a saddle and crept a few steps from the enemy posts to a watering hole located behind the camp. An English soldier was driving a herd, when suddenly two of our cavalry scouts with guns at the ready came out of the bushes and shouted: “Hands up” (hands up). A whistle fell out of his mouth in surprise. Immediately he was approached with the question: "Where are the missing horses?" The fact is that our conscientious patrolman noticed only 57 heads in the herd, while the day before he counted more than 80 horses. It turned out that they were sent to the rear. The horse-leader of the herd and several other horses were quickly saddled, on which they jumped, and ours quickly rushed around the enemy camp towards the German posts.

In the same way, in the captive Englishman, who was forced to make this journey with the rest, sitting, not very comfortably, right on the slippery back of his horse, the inborn sports spirit of his people woke up. Full of humor, he exclaimed: "I really would like to see what kind of face my captain has now," and when the animals arrived happily at the German camp, he said: "it was a damn clever thing."

The booty thus obtained, together with a known number of captured horses and mules, made it possible to field a second cavalry company. The two cavalry companies now available, which consisted partly of Europeans and partly of Askari, were brought together. This event was well worth it. It enabled us to send a strong partisan detachment on long raids over the vast steppe regions north of Kilimanjaro, and, in addition, to penetrate to the Uganda and Magadsk railways, destroy bridges, attack railway posts, lay mines under the railway tracks and produce all sorts of sudden attacks on the communication lines in the area between the railway and the enemy camps. We also suffered losses. One of the patrols made a brilliant fire attack on two Hindu companies near the Magadskaya railway, but then lost its saddle horses from enemy fire, which were left behind cover; he had to make a long 4-day return trip across the steppe on foot and without food. Fortunately, people got in one of the Massey croals (Croal is a native village with extensive fenced areas for cattle corralling) milk and some meat; later they were saved from starvation by a dead elephant. However, along with the success, enterprise also grew, and requests for permission to go in search as soon as possible, on horseback or on foot, became numerous.

Patrols were of a different nature, which were sent out from the Kilimanjaro region, mainly in an easterly direction. They traveled for many days on foot through thick bushes. The patrols that destroyed the railways were mostly weak: one or two Europeans, two to four askaris and 5-7 porters. They had to sneak through enemy guards and were often betrayed by native spies. Despite this, they mostly reached the goal and sometimes were on the road for more than two weeks. For such a small number of people, one killed animal or insignificant prey then represented a significant help in terms of food. Despite this, the deprivation and thirst in the unbearable heat were so great that many times people died of thirst. It was bad business when someone fell ill or was injured; often, despite all the desire, there was no way to transport it. Carrying the seriously wounded from the Uganda railway across the entire steppe to the German camp, if this happened, presented incredible difficulties. Colored people understood this too, and there were cases when a wounded askari, fully conscious that he had died hopelessly and left to be eaten by numerous lions, did not complain when he had to be thrown into the bushes, but, on the contrary, handed over weapons and cartridges to his comrades, so that, according to at least not let them die.

This patrol activity has been improved more and more. Familiarity with the steppe grew, and next to the patrols, which acted covertly, avoided collisions and blew up railways, combat patrols developed their activities. They, from 20-30 or more askaris, sometimes armed with one or two machine guns, searched for the enemy and tried to inflict losses on him in battle. At the same time, in the thick bushes, such close and unexpected clashes came up that our askaris sometimes literally jumped over the prone enemy and thus reappeared in his rear. The influence of these enterprises on amateur activity and readiness for battle was so great among Europeans and coloreds that it would be difficult to find an army with a better fighting spirit.

True, it was necessary to reckon with known shortcomings. With a small number of cartridges, we could not achieve such a high degree of shooting perfection as to really destroy the enemy in those cases when we put him in a difficult position.

Our technology also did not remain idle. Dexterous fireworks and gunsmiths incessantly produced, together with factory engineers, devices suitable for damaging railways and roads. Some of these mechanisms exploded, depending on how they were installed, either immediately or after a certain number of axles had passed over them. With the help of the last device, we counted on the destruction of steam locomotives, since the British, in the form of security measures, placed in front of them one or two wagons loaded with sand. As an explosive material on the plantations there was a large amount of dynamite, but the subversive cartridges captured at Tanga turned out to be much more effective.

In April 1915, unexpected news came of the arrival of an auxiliary vessel. At the entrance to Manza Bay, north of Tanga, it was chased by an English cruiser, fired upon, and the commander was forced to sink it. Although in the following weeks it was possible to almost completely save the cargo so precious to us, but, unfortunately, it turned out that the cartridges were badly damaged. sea water. Gunpowder and capsules were destroyed more and more, and, thanks to this, the number of misfires increased. We had no choice but to dismantle the available ammunition, clean out the powder and partially insert new primers. Fortunately, the latter were found on the territory of the colony, although of a different design; thus, in Neimoshi, for a month, all the askaris and porters that could be collected were busy from morning till evening restoring cartridges. The former stock of serviceable cartridges was left exclusively for machine guns, and from reloaded firearms, those cartridges that gave about 20% misfires were used for combat purposes, while others, with a large percentage of misfires, were used for training.

The arrival of the support vessel caused great enthusiasm, as it showed that there really is still a connection between us and the motherland. Everyone listened with intense attention to the stories of the commander, Fleet Lieutenant Christiansen, when the latter, after recovering from his wound, came to me in Neimoshi. The strong fighting at home, the readiness to sacrifice oneself and the boundless spirit of enterprise that guided the military actions of the German troops, also found a response in our hearts. Many of those who hung their heads cheered up, because they heard that it is possible to do things that are completely, apparently unattainable, when there is a resolute will for this.

Another means of influencing the spirit of the troops was the practice of production. In general, I could carry out productions no higher than the non-commissioned officer rank, while the right to promotion to officers, in many cases quite deserved, was not granted to me, of course. In each individual case, it was very strictly weighed whether there really was a feat. In this way, undeserved productions were avoided, which are very unfavorably reflected in the morale of the parts. In general, we were forced to influence moral factors with rewards less than in other ways. We almost did not see military orders at all and had to excite and support not the personal ambition of individual soldiers, but a real sense of duty, dictated by love for the motherland, and a sense of camaraderie that grew stronger over time. Perhaps it was precisely the fact that this long and pure impulse to action was not overshadowed by other motives that gave the Europeans and Askaris the courage and strength of scope that the colonial army was completely distinguished by.

The British at Kilimanjaro were not idle. On the morning of March 29, from Mount Oldorobo, 12 kilometers east of Taveta, occupied by a German officer post, they reported by telephone about an attack by two Hindu companies. Captain Kehl and the Austro-Hungarian Oberleutnant von Unterrichter immediately set out in marching order from Taveta and from two sides attacked these companies, seated on the steep slopes of Mount Oldorobo, so energetically that the retreating enemy left about 20 people in place and one fell into our hands machine gun and 70,000 rounds of ammunition. Other operations were conducted by the enemy along Tsavo to the northeast of Kilimanjaro. These actions developed from the heavily fortified and occupied by several companies Mzima camp, located at Tsavo. The skirmishes of the patrols that took place northeast of Kilimanjaro were successful for us in all respects. In the same way, the young askaris of Rombo's 60-man force, which took its name from the mission located near eastern Kilimanjaro, had unlimited confidence in their superior, over 60-year-old Oberleutnant von Bock. I remember how one wounded man, who came from him to Neimoshi and made a report to me, refused treatment in order not to lose time to return to his chief. In some battles, sometimes against two enemy companies, these young people threw back the enemy, and it turned out that legends had formed around these battles among the British. The British commander-in-chief complained to me in writing that a German woman, who was notable for her cruelty, was taking part in these military clashes.

This statement, of course, had no foundation and only showed me how nervous they were in the enemy's headquarters.

Despite the great booty at Tanga, it was clear that in the coming long war the reserves of our colony should be depleted. The coloreds in Neimoshi immediately began to wear silk: this was by no means a sign of special luxury, but simply the stocks of Hindu shops in respect of cotton fabric had run out. We seriously had to think about how to create something new ourselves and turn the raw material available in large quantities into finished products. A peculiar activity unfolded, reminiscent of some kind of Robinson in its work. Cotton fields abounded. Got hold of popular books that spoke of the forgotten art of hand-spun and cloth; white and black women spun by hand; on missions and at private artisans, spinning wheels and looms were arranged. Soon, in this way, the first suitable cotton fabric was obtained. The root of the tree known as ndaa was found, after testing, to be the best among various dyes, and gave this fabric a brownish-greenish color, which did not stand out either in the grass or in the bush, and was especially suitable for military uniforms. Rubber extracted from trees was treated with sulfur, and thus rubber suitable for car and bicycle tires was obtained. In the Morogoro region, some planters have succeeded in extracting a gasoline-like substance called trebol from coconuts, which is suitable for motors and cars. As in the old days, candles were made from tallow and wax in the household and in the army, and soap was brewed. Likewise, numerous factories on the plantations of the Northern Region and along the Tanganaike Railway were converted to meet the needs of life.

Especially important was the manufacture of shoes. The raw material was supplied by numerous skins of cattle and wild animals, and the tanning material was supplied by the mangroves of the sea coast. Already in peacetime the missions made good boots; now their activities were expanded, and, in addition, the troops also set up large tanneries and workshops. In any case, it was some time before the supplies could adequately meet the urgent and necessary needs of the troops, especially for the buffalo skins needed for the soles. Thus, the historical struggle for the cowhide was revived again in East African conditions. The first boots made in large numbers came from Tanga. Although their original shape needed improvement, they still protected the legs of our white and black soldiers during the campaign and patrols in the thorn thickets of pori, where the thorns that fell to the ground dug into the leg. All the petty food-producing endeavors that already existed on the plantations in peacetime are now widely developed by the war and the need to supply large masses of people. On some farms on Kilimanjaro, butter and excellent cheese were produced in large quantities, and the work of the slaughterhouse in the vicinity of Wilhelmsthal could hardly satisfy the need for sausage and ordinary smoked products.

It could be foreseen that quinine, so important for maintaining the health of Europeans, would soon be exhausted and that the need for it could not be covered by booty alone. Thus, it was of great importance that the Amani Biological Institute, in Uzambar, managed to organize the production of good cinchona cakes from the bark of the cinchona tree mined in the north.

The construction of roads necessary for the movement of carts and cars led to the construction of permanent bridges. The engineer Rentell, who was drafted into the army, built a stone and concrete bridge west of Neimoshi with strong foundations across the fast-flowing Kikadu. During the rainy season, i.e. especially in April, no wooden bridge could withstand the pressure of water masses in a steep channel, probably 20 meters deep.

They also worked diligently on the organization of the troops. The transfer of Europeans in large numbers in rifle companies to askari companies covered the loss of Europeans here; Askaris were placed in rifle companies. Thus, the field and rifle companies became the same in composition and, during 1915, homogeneous. In Muanze, Kigom, Bismarckburg, Lindi, Neulangenburg and elsewhere, small military formations were formed under various names, the existence of which the command found out for the most part only after a fairly long time. These formations were also gradually reorganized into companies; thus, during 1915, the number of field companies gradually increased to 30, rifle companies to 10, and other formations, by strength per company, to approximately 20; in general, the largest number of 60 companies was thus reached. With a limited number of fit Europeans and reliable askaris, it was undesirable to further increase the number of companies - then, in fact, there would be formations without any internal stability.

In order to increase the total number of fighters, the company staff was increased from 160 to 200 askari, and companies were allowed to have askari more than this staff. Companies sometimes trained their own recruits. But the bulk of the askari replenishment came from recruit depots set up in the populated areas of Tabora, Muanza and the Northern Railway, which at the same time constituted local security and ensured order. However, with a large number of newly deployed companies, the recruiting depots could not provide enough reinforcements to bring all the companies completely to the full strength of 200 people. The highest number of exposed troops was reached at the end of 1915 and amounted to 2,998 Europeans and 11,300 askaris, including sailors, rear institutions, infirmaries and field mail. How necessary all these military preparations were, the news received at the end of June 1915 showed that General Botha was to arrive from South Africa to the theater of operations in East Africa with 15,000 Boers. This news from the very beginning seemed very plausible. Fragmentary wireless telegraph conversations and a few reports of events in the outside world indicated that the situation in south-west Africa was developing unfavorably for us and that the British troops stationed there would probably be used elsewhere in the near future.

CHAPTER EIGHT

IN EXPECTATION OF THE BIG ENEMY OFFENSIVE.

ENERGETIC USE OF THE REMAINING TIME

(June- December 1915)

(Drawings IV and VI)

At first it seemed that the expected action of the South Africans would not take place, since the Englishman apparently tried to overcome us without their help with his own forces. In July 1915 he made an attack on the colony at various points. To the east of Lake Victoria appeared large bands of massai, organized and led by the British, believed to be several thousand in number, who attacked the cattle-rich areas of the German Wassukum. However, when it comes to the removal of livestock, the Vassukuma did not understand jokes and provided all kinds of assistance to our weak posts. They attacked the Massai, again recaptured their captured cattle, and as a sign that they were "telling the truth", they piled 96 severed Massai heads in front of our police station. In the area of Kilimanjaro, the enemy launched an offensive against our main group of troops in significant forces. In order, on the one hand, to carry out a real defense of the Uzambara railway and its areas rich in plantations, and on the other hand, to shorten the path of our patrols to the Uganda railway, a detachment of 3 companies was advanced from Taveta to Mbujuni, which is one reinforced crossing east of Taveta . One day's march to the east was the heavily occupied and fortified English camp of Makatau on the high road that led from Neimoshi via Taveta, Mbujouni, Makatau, Buru to Woi on the Uganda railway. Vague rumors have given reason to believe that new big operations can be expected from Voy.

On July 14, in the Makatau steppe, covered with rare thorny bushes, an enemy brigade appeared under the command of General Malleson. The fire of the field battery on the rifle trenches of our askaris was of little effect, but the superiority of the enemy (seven against one) was still so great that our situation became critical. The enemy European cavalry covered our left flank. The merit of Lieutenant Steingeyser, who was later killed, is that he, together with the valiant 10th field company, which received combat experience at Longido, did not retreat, despite the withdrawal of neighboring companies. Just at a critical moment, a patrol, also killed later, Ober-Lieutenant von Levinsky, came out to the rear of the enemy enveloping units, who immediately moved to the noise of the battle and completely paralyzed the envelopment that was dangerous for us. English troops, Europeans and Indians, mixed with the askaris, attacked our front very bravely in a terrain that afforded little cover. However, the failure of the English outreach ended in their defeat with a loss of 200 men. At the railway station at Neimoshi, I followed the course of the battle by telephone, and in this way I experienced all the tension from a distance, from an unfavorable position at first to complete victory.

This success and significant booty again raised the spirit of enterprise of our Europeans and askaris. Only now, strictly speaking, a period has come when, relying on previous experience and acquired dexterity, continuous searches for combat patrols and attempts to blow up the railway have developed. According to later reports by the British commandant of the line, a total of 35 successful destructions of the railway were achieved.

The captured photographs and reconnaissance data confirmed our assumption that the enemy was indeed building a railway from Voy to Makatau, which, due to its reach and its importance, presented an excellent target for the actions of our patrols. The construction of this important road showed that an attack was being prepared by large forces and precisely at this point in the Kilimanjaro region. Thus, South Africans could be expected to appear here. It was necessary to strengthen the enemy in this intention in order that the South Africans would actually be transferred here, and, moreover, in as large a number as possible, and thus be used far from other more important theaters of war. Therefore, the enterprises against the Uganda railway were carried out with extreme tension. However, under the circumstances prevailing at the time, these operations could consist mainly of small patrol actions and only in exceptional cases of clashes of entire companies.

Closer acquaintance with the steppe between the Uganda railway and the Anglo-German border showed that, of the various mountain peaks rising steeply above the plain, the Kasigao massif was rich in water and decently populated. With a distance of only 20-30 kilometers from the Uganda railway, Kasigao was to form a conveniently located stronghold for guerrilla operations. Even earlier, Oberleutnant Grote's patrol had played a trick on a small Anglo-Hindu camp located in the middle of a mountain slope. The riflemen of his patrol surrounded the stone-walled camp and opened very successful fire from the higher part of the mountain right on the camp. Very soon the enemy threw out a white flag, and the English officer and about 30 Indians surrendered. Part of the enemy forces managed to go up the mountain and fire on our patrol during the withdrawal. Only at that moment we suffered losses in several wounded, among whom was also a medical officer. The enemy post at Kasigao was also fired on occasion with 6-cm fire. tools.

By the end of 1915, the enemy was again attacked at Kasigao, where by that time he had set up his camp. The German combat patrol under the command of Lieutenant von Rukteshel all night long, for 9 hours, climbed a steep mountain and, rather exhausted, settled down near the enemy fortification. The second patrol, operating jointly with the Rukteshel patrol, under the command of Lieutenant Grote, lagged behind somewhat due to the illness and fatigue of this officer. Oberleutnant von Ruckteschel sent an envoy, an old black soldier, to the enemy with an offer to surrender and observed that our askari was very cordially received, since he found several of his good acquaintances among the English askari. But, despite all the courtesy, the enemy rejected the surrender. Our situation, due to great exhaustion and lack of food, was critical. If anything had to be done at all, it had to be done immediately. Fortunately, the enemy in his fortification could not withstand the fire of our machine guns and the subsequent offensive; it was destroyed, and most of its fleeing men were smashed as they fell from the steep cliffs. In addition to a large amount of food and clothing, valuable tent equipment was also seized. The feeling of mutual connection that our askaris felt towards us Germans, and which was greatly developed through numerous joint ventures, led in this case to a peculiar scene. After a night climb to Kasigao, which went through rocky cliffs and thorny thickets, one askari noticed that Lieutenant F. Rukteshel had scratched his face until it bled. He immediately took his stocking, which probably had not changed for six days, and wiped his face with it "Bwana" (chief lieutenant). Slightly surprised by the question of the latter, he warned with the words: “This is a military custom; it's only for your friends."

In order to understand the state of affairs on the spot and speed up the enterprises against Kasigao, I went by rail to Same, from there in a car to the Gonja mission and then partly by bicycle, partly on foot in the direction of Kasigao to the German border, where there is a water source our company was encamped. Communication by heliograph and messengers from there to Kasigao worked satisfactorily, and thus the success gained at Kasigao could be consolidated. Troops were immediately drawn in, and several companies continued to occupy Kasigao until the arrival of the South Africans. However, the supply of food there was made with great difficulty. Despite the fact that the German region west of Kasigao was rich in local resources, it could not provide food for such a large military mass for a long time, the number of which, together with porters, was estimated at about 1,000 people.

Then I went by car around the mountains of southern Pare along a highway laid in advance in peacetime. The construction of this road was suspended due to lack of funds, and heaps of rubble lay for years without use on both sides of the road. Pipes laid under the roadbed to drain water were for the most part in good condition. Minor work was required to strengthen this road and make it suitable for trucks. Transportation of goods from Buiko on the Northern Railway was carried out by cars to Gonji and from there further to Kasigao by porters. A telephone wire to the border had already been laid, and a few days later the connection was established.

Patrols advanced from Kasigao had numerous clashes with enemy detachments, and also carried out destruction on the Uganda railway. However, in the wild, rocky and densely overgrown with thorns, movement was made with such great difficulty that Kasigao did not fully justify its purpose as a stronghold for guerrilla operations before the arrival of the South Africans. But, at the same time, due to the constant threat to the railway, the enemy was at least forced to take extensive measures to protect it. On both sides of the railroad, wide strips were cleared, which were fenced off from the outer edge with a solid fence of thorny bushes. Then, about every two kilometers, strong blockhouses, or fortifications, equipped with artificial obstacles, were arranged, from which patrols were to constantly inspect the railway track. Special detachments were kept at the ready, with a force of a company or more, for immediate transfer in special trains upon receipt of a message about an attack on any point of the railway. In addition, covering detachments were advanced in our direction, which tried to cut off our patrols on their return from the railway, as soon as spies or posts located on elevated points reported this. On the heights southeast of Kasigao up to the seashore and further into the area of coastal settlements, English camps were also located, against which, in turn, the actions of our patrols and flying detachments were directed. We have sought to incessantly harm the enemy, force him to take defensive measures and thus tie up his forces here in the area of the Uganda Railway.

For this purpose, strongholds for our combat patrols were established from the coast to Mbujuni (on the Taveta-Voi road); we worked in the same direction in a more northern region. The enemy camp at Mzima on the headwaters of the Tsavo River, and its communications with the rear along that river, were constant objects of our undertakings, carried out both by patrols and by larger detachments. Captain Ogar, while carrying out such an undertaking, was taken by surprise with his 13th company in dense bush, southwest of the Mzima camp, by three enemy European companies of the newly arrived 2nd Rhodesian Regiment. The enemy appeared from different sides. However, he, who was still little familiar with the conditions of the war in the bush, lacked the necessary unity in actions. Thanks to this, our askari company was fortunate to first push back one part of the enemy, and then, quickly making a decision, also defeat the other part that appeared in the rear.

In the same way, further to the north, successful battles were played out for us in the bush, where we acted with forces near the company and inflicted significant losses on the enemy, who often outnumbered us. To the north of Engare Lena, the 3rd field company, drawn from Lindi, worked especially vigorously, and its combat patrols reached the Uganda railway. The mere fact that we were now able to conduct rapid campaigns in detachments to a company and more in the steppe, deprived of local resources and poor in water, shows that the troops have made tremendous progress in this method of waging a small war. The European realized that many of the amenities highly desirable for traveling in tropical regions should disappear precisely in war, and that if necessary, you can get by with the services of only one porter for a while.

The patrols were supposed to avoid the treacherous smoke from the fires during the stops and take with them, if possible, already prepared food. If it was necessary to cook, then it was especially dangerous in the morning and evening hours. The chief then had to choose a shelter hidden from view and, in any case, change the place of parking after cooking, before settling down for the night. Complete protection against mosquitoes was not possible under the difficult working conditions of the patrols. Therefore, a known number of cases of malaria were consistently found among participants after return. However, since the patrol service, despite the constant damage inflicted on the enemy, required relatively few people, only a part of the companies had to be in the front line. After a few weeks, each company was taken to the rear to rest in a camp located in a healthy area. Europeans and askaris could take a break from excessive hardships, resume their training and strengthen discipline.

By the end of 1915, the lack of water in the Mbujuni camp was so great, and the delivery of food became so difficult that only a post was left there, and the rest of the detachment was pulled back west to the area of \u200b\u200bMount Oldorobo. Meanwhile, the enemy camp of Makatau was constantly growing. Busy train traffic reigned, and it was clearly visible how a large embankment was being created in the western direction for the further construction of the railway. Although our patrols often had the opportunity to inflict losses on the enemy during his work and guarding the latter, the construction of the railway nevertheless moved forward in a westerly direction.

It had to be taken into account that the area of the Northern Railway might soon fall into the hands of the enemy. Thus, care should be taken to ensure that the military reserves of the Northern District were transported to a safe place on time. This presented no difficulty as long as the railroad track was at our disposal. At Neimoshi and at Mombo, most of our stores of ammunition, uniforms and sanitary equipment were located. It could be expected that machinery and machine parts could be transported by ordinary roads; therefore, they should have been used locally for as long as possible and continued production. In accordance with the enemy offensive, the direction of our withdrawal was determined, in general, in a southerly direction, and not only preparations, but the transportation itself was to begin without wasting time, that is, already in August 1915.

Therefore, the commandant of the line, Lieutenant Kroeber, prudently collected material from the plantations of the field railway and in one day built a branch of the field railway from Mombo to Gandeni. Carts were also purchased from the plantations, and after serious discussion, manual transportation was preferred over steam locomotives. Thus, the supplies of the north were completely and timely transferred by rail to Gandeni. There, with the exception of a few wagons, transportation was mainly carried out by porters to Kimamba on the Central Railway. However, it was necessary to refrain from transportation, because, despite the obvious preparations of the enemy for an invasion of the Kilimanjaro region, I still reckoned with the possibility that the main enemy forces, or at least a significant part of them, would not be moved near Kilimanjaro, and to the Bagamojo-Daresalam area.

By the end of 1915, the enemy moved gradually to the west with the construction of the railway. To prevent this, Major Kraut, with 3 companies and 2 light guns, fortified his position on Mount Oldorobo. This mountain rose among the flat steppe, covered with thorny bushes, 12 kilometers east of Taceta, on the main road and far dominated the surrounding area in all directions. Its fortifications, partly carved into the rocks, in connection with numerous false structures, formed a stronghold, which was almost impossible to capture. The disadvantage of the position was the absolute absence of water. Although the colonist who entered the army, lieutenant of the Matushka reserve, achieved good results as a water scout near Taveta and discovered excellent springs there, not a drop of water was found at Oldorobo, although they dug in different places on his instructions at a depth of more than 30 meters. Therefore, water had to be transported to Oldorobo from Taveta in small carts pulled by donkeys, and collected there in barrels. This delivery of water was an extremely heavy burden on our means of transportation. It is remarkable that the enemy did not even think of disrupting the supply of water and thus making it impossible for us to hold Oldorobo. Instead, relying on the railway under construction, he advanced 5 kilometers from the east to the mountain and built a heavily fortified camp there. It was not possible to prevent him from doing this, since, due to difficulties in supplying water and transportation means, larger military formations could only move away from Taveta for a while. The enemy, in turn, covered his need for water through a long water supply system, which started from the sources of Mount Bura. The destruction of the enemy water tank by patrols of Lieutenant Stitenkron of the reserve caused only temporary difficulties to the enemy.

At this time, the first airplanes appeared at the enemy and bombarded our positions at Oldorobo and Taveta, and later also at Neimoshi. On January 27, 1916, one of these pilots, returning from Oldorobo, was successfully fired upon by our advanced infantry and fell. The British announced to the natives that these airplanes were the new "Mungu" (god), but by the fact that this new "Mungu" was shot down and captured by us, it served rather to strengthen than weaken the respect for the Germans.

CHAPTER NINE

SECONDARY SITES OF MILITARY ACTIONS.

SMALL WAR ON WATER AND LAND

(During 1914- 1915)

(Drawings I and III)

With the use of the main forces of the army in the area of the Northern Railway, it was impossible to completely clear the rest of the colony. It was absolutely necessary to keep the natives within the country in subjection, in order, if necessary, to be able to satisfy all the increased requirements in relation to porters, cultivation of the land, transportation of goods and work of all kinds. To this end, the 12th company remained in Maheng, and the 2nd company in Iringa. Along with their usual tasks, both of these companies were large recruit depots, which served to fill the holes created in the front and at the same time made it possible for new formations.

Far cut off from the center and not connected with it by wire, the commanders of the detachments on the frontiers quite rightly sought to warn the enemy and attack him on his own territory. With a lack of communication with us, these fighting disintegrated into a number of single enterprises that were conducted independently of each other. The situation was different with the enemy; the latter, apparently, tried to coordinate his main military operations with those actions that took place in other parts of the border.

In October 1914, that is, before the battles at Tanga, Captain Zimmer reported from Kigoma that there were about 2,000 people on the Belgian border; Captain Braunschweig from Muanza, - that a very strong enemy is also concentrated on Lake Victoria near Kizumu, that Kizi has about 2 companies and, in addition, there are more units at Karungu. According to other completely unrelated information from the natives, Hindu troops arrived in Mombasa in October and were then transferred further in the direction of Woi. In the district of Bukoba, the British troops were advancing through Kagera, and the neighboring point of Umbulu reported on the advance of enemy troops in the Songjo region. Apparently, this was a preparation for operations that were to be coordinated with a large offensive directed at Tanga in early November 1914.

With the lack of means of communication in the colony, it was impossible to act against these separate enemy detachments advancing along the border with our main forces and quickly transfer them in turn against one enemy, then against another. Therefore, we had to adhere to the main idea of our plan for the conduct of the war, namely, from the area of the Northern Railway, we strongly press on the enemy located here and thus also relieve other areas where military operations were carried out.

Thus, in September 1914, the main forces of Falkenstein, as well as Auman with part of the second company, were moved from Iringa and Ubena to the Neilangenburg region. In March 1915, the 26th field company was transferred from Daresalam through Tabora to Muanza. In April 1915, the concentration of enemy units in Maradreik (east of Lake Victoria) and at Bismarckburg prompted further time-consuming movements of troops from Daresalam through Muanza to Maradreik, and also through Kigoma to Bismarckburg; the latter was further slowed down by the lack of means of transportation on Lake Tanganaika, since the construction of the Getsen steamer in Kigoma moved very slowly.

Initially, enemy actions were directed mainly at the sea coast.

At the beginning of the war, our small cruiser Koenigsberg left the harbor of Daresalam and on September 20, 1914, surprised the English cruiser Pegasus off Zanzibar and inflicted serious damage on it. After that, several large enemy cruisers appeared, which were intensively looking for the Koenigsberg. On October 19, a large armed boat approached the East African line steamship President hidden in the Lukuledi River near Lindi. The local district units located in Lindi and the reserve company under the command of Captain Ogar were just absent to counter the enemy landing, which was supposed to be at Mikindani, so nothing could be done against the armed boat.

Only on June 29, 1915, several enemy ships went up the Lukuledi and blew up the President steamship located there.

"Koenigsberg" after successful cruising raids in Indian Ocean took refuge in the mouth of Rufiji. But his parking lot was opened by the enemy. The river here has formed a far-branched and very closed delta, the islands of which are overgrown with dense shrubs. The exits from individual river branches were defended by the Delta detachment. It was a detachment of colonial troops, which consisted of sailors, European volunteers and askaris in total about 150 rifles, several light guns and several machine guns, under the command of Captain Schoenfeld. Numerous attempts by the enemy to break through with light ships at the mouth of the river were constantly repulsed by us with significant losses for him. "Adjutant" - a small steamer, which the British captured as a valuable prize, and armed, was again recaptured from them during these actions and then used as an auxiliary ship on Lake Tanganaike. Similarly, several British airplanes were damaged near the mouth of the Rufiji. The barrage ship sunk by the British in the northern arm of the Rufiji did not achieve its goal of locking up our cruiser. Captain Schoenfeld, by his skillful choice of the parking place and the timely change of the latter, met the constant shelling of the enemy's ship guns, against which he was powerless to fight. In early July 1915, the British delivered 2 small-draft gunboats equipped with heavy guns to Rufiji. On July 6, the first attack was made by 4 cruisers, 10 other armed ships and 2 river gunboats. With the help of airplanes, enemy ships fired on the Koenigsberg, which was anchored on the river. The attack was repulsed; but when it was repeated on July 11, the Koenigsberg was badly damaged. The servants who serviced the guns were put out of action. The seriously wounded commander ordered to throw the locks from the guns over the side and blow up the cruiser. In itself, the heavy loss of the Koenigsberg brought at least the benefit to the fighting on land that the personnel and valuable material were now at the disposal of the colonial troops.

The parts of the guns thrown overboard were again caught, and ten 10.5-cm. the guns of the Koenigsberg were gradually adapted for transportation on carriages made in the colony. According to the instructions of the cruiser commander, the ten guns of the Koenigsberg were fully assembled and again put on alert; 5 were installed at Daresalam, two each at Tang and Kigoma, and one at Muanze. Fleet Captain Schoenfeld, who was in command at the mouth of the Rufiji, ordered the use of several wagons built for heavy loads and located on one nearby plantation for transportation. These guns rendered great service from their covered positions on land, and, as far as I knew, not a single gun was damaged by this method of use, despite repeated bombardment by enemy ships. On September 26, 1915, the Vami steamer was transferred from Rufiji to Daresalam at night. At the end of August, men from the steamship Ziten arrived in Lindi from Mozambique in several boats to enter the army.

On January 10, 1915, about 300 people of Hindu and black troops with machine guns landed on Mafia Island. Our police unit, consisting of 3 Europeans, 15 askaris and 11 recruits, resisted stubbornly for 6 hours, but then was forced to surrender after the seriously wounded commander, Lieutenant of the reserve Schiller, who fired accurately from a mango tree, was out of action on the opponent. The British decided to occupy the Mafia with a few hundred men and set up an observation post on the nearby smaller island as well.

Apparently, propaganda among the natives was carried out from here. On the night of July 30, 1915, a boat with proclamations was detained near Kisinju.

The events at Daresalam, where on October 22, 1914 the commander of one of the British cruisers announced that he did not consider himself bound by any treaties, have already been mentioned above.

The airplane, which arrived at the exhibition in Daresalam before the declaration of war, was handed over to serve the army shortly after the opening of hostilities; however, on 15 November it crashed in an accident off Daresalam. At the same time, the pilot Lieutenant Genneberger died.

At Tanga after big fights in November 1914 it was quiet. On March 13, 1915, a ship ran into the reef, but was freed again at sea tide. Immediately they began to extract 200 tons of coal from the water, which the ship threw overboard.

Several rows of improvised mines, which could have been detonated from the shore, did not justify themselves, and later it turned out that they had become unusable.

The shelling of various points along the coast continued all the time. On 20 May, a warship fired on Lindi after his demand for the surrender of troops stationed there was denied. Similarly, on April 1, 1915, the area south of Paangani was shelled, then on April 12, the island of Kwale, and on the night of April 24, the Rufiji delta.

On August 15, 1915, the Hyacinth and 4 patrol boats appeared in front of Tanga. Our two 6-cm. the guns were quickly transferred from the parking lot at Gombezi to Tanga and, together with a light gun from Tanga, were successfully used on August 19, when the Hyacinth, 2 gunboats and 6 whaling ships appeared again, destroyed the steamer "Markgrave" and fired at Tanga. The gunboat received two well-aimed hits, and one of the whaling ships left with a broken side with 4 successful shots.

In the area of Songjo, between Kilimanjaro and Lake Victoria, during these months enemy patrols appeared repeatedly, and the natives seemed ready to break out of obedience. Sergeant Baet, who was sent there with a patrol, was ambushed by the treachery of the population of Songjo and on November 17, 1914, was killed along with 5 askaris. With the help of a punitive expedition of an officer of the Arusha district, Lieutenant of the Kemfe reserve, who was drafted into the army, the population of Songjo was pacified.

Only in July 1915 did things again come to clashes between patrols in this area, and in one of the clashes 22 enemy armed natives were killed. Then, at the end of September and the beginning of October, 1915, Oberleutnant Büchsel's patrol made a remarkable journey on horseback through Songjo into the English area without meeting the enemy, since the English post, which was apparently warned, avoided a collision.

The 7th company, located in Bukoba, near Lake Victoria, and the 14th company - in Muanza were connected with each other by radiotelegraph. Dominance on the lake was, undeniably, in the hands of the British, since the enemy had at least 7 large steamers here. However, in spite of this, our little steamer Muanza, as well as other smaller ships, could maintain a great freedom of movement. While the resident in Bukoba, Major von Stümer, was covering the border with his police and with the assistance of the troops of the friendly Bukoba Sultan, Captain Bock von Wülfingen moved with the main forces of the 7th company from Bukoba to Muanza. From here, in early September 1914, he set out with a combined detachment, consisting of parts of the 7th and 14th companies, as well as Vasukum recruits and auxiliary native soldiers, along the eastern shore of Lake Victoria in a northerly direction against the Uganda railway. On September 12, at Kesey, on the other side of the border, he threw back an enemy detachment, but then, having received information about the movement of other enemy detachments, he retreated to the south. Thus, only weak detachments remained to protect the border east of Lake Victoria.

The conduct of the war in the area of Lake Victoria was very difficult for us. There was a constant danger that the enemy would land at Muanza or at another point on the southern coast, seize the region of Vasukum and threaten Tabora, the ancient capital of the country. If our troops remained in the Muanza area, then the danger threatened not only the areas around Bukoba, but also Rwanda. The most likely chance of success at Lake Victoria could have been the active conduct of hostilities united by a common leadership. However, such a plan was not particularly easy to carry out, since the most suitable leader for this, Major von Stümer, was associated with his activities as a resident with the Bukoba district, while it was Muanza who was more important.

At the end of October 1914, an attempt to transfer part of the troops by boat from Muanza again to Bukoba ended unsuccessfully, due to the appearance of armed English ships near Muanza. Obviously, the enemy had deciphered our communications by radiotelegraph and taken appropriate measures. The expedition from Muanza to support Bukoba consisted of 570 rifles with 2 guns and 4 machine guns and was sent on October 31, 1914 on the steamer Muanza with 2 tugs and 10 native boats. On the same day in the morning this flotilla was dispersed by unexpectedly appearing enemy steamers and soon reassembled without loss in Muanza. Following this, an attempt by the British to make a landing at Cagenza proved fruitless, thanks to our opposition; a few days later the English steamer Sybil was found wrecked and sunk off Majita.

On November 20, after a 12-hour battle north of Bukoba, Stümer's detachment drove back the British troops that had penetrated German territory, and then again defeated them at Kifumbiro after they crossed the Kageru River. On December 5, 1914, the British fired unsuccessfully from the side of Lake Shirati, and on December 6 - Bukoba.

Small patrol skirmishes occurred constantly east and west of Lake Victoria. The enemy tried to make a stronger blow on January 8, 1915, when he fired at Shirati with 6 guns and machine guns from the side of the lake and landed 2 Hindu companies and a large number of European cavalry. Oberleutnant von Haxthausen, after a 3 1/2-hour battle, retreated with his 2 guns, due to the superiority of the enemy. In the following days, the enemy intensified to 300 Europeans and 700 Indians. Then, on January 17, Gaksthausen scattered 80 Europeans and 150 askaris on the border with two machine guns, and on January 30, the enemy again cleared Shirati and went to sea in the direction of Karunga. I think that this withdrawal was caused by the heavy defeat that the enemy suffered at that time (January 18) at Jassini. He apparently considered it necessary to bring his forces back to the Uganda Railway.