The problem of choice is one of the central ones in economics. The two main actors in the economy - the buyer and the producer - are constantly involved in the processes of choice. The consumer decides what to buy and at what price. The producer decides what to invest in, what goods to produce.

One of the basic assumptions of economic theory is that people make rational choices. Rational choice means the assumption that a person's decision is the result of an orderly thought process. The word "orderly" is defined by economists in a strict mathematical form. A number of assumptions about human behavior are introduced, which are called the axioms of rational behavior.

Provided that these axioms are valid, a theorem is proved on the existence of a certain function that establishes human choice - the utility function. usefulness called the value that in the process of choice maximizes a person with rational economic thinking. We can say that utility is an imaginary measure of the psychological and consumer value of various goods.

Decision-making problems with consideration of utilities and probabilities of events were the first ones that attracted the attention of researchers. The setting of such tasks usually consists in the following: a person chooses some actions in a world where the result (outcome) of the action is influenced by random events beyond the control of a person, but having some knowledge about the probabilities of these events, a person can calculate the most advantageous set and order of his actions. actions.

Note that in this formulation of the problem, options for action are usually not evaluated according to many criteria. Thus, a simpler (simplified) description of them is used. Not one, but several successive actions are considered, which makes it possible to build so-called decision trees (see below).

A person who follows the axioms of rational choice is called in economics rational person.

2. Axioms of rational behavior

Six axioms are introduced and the existence of a utility function is proved. Let us give a meaningful presentation of these axioms. Denote by x, y, z different outcomes (results) of the selection process, and by p, q - the probabilities of certain outcomes. We introduce the definition of a lottery. A lottery is a game with two outcomes: outcome x, obtained with probability p, and outcome y, obtained with probability 1-p (Fig. 2.1).

Fig.2.1. Lottery introduction

An example of a lottery is a coin toss. In this case, as is known, heads or tails fall out with probability p = 0.5. Let x = $10 and

y = - $10 (i.e. we get $10 on heads and pay the same amount on tails). The expected (or average) price of the lottery is determined by the formula px + (1-p) y.

We present the axioms of rational choice.

Axiom 1. Outcomes x, y, z belong to the set A of outcomes.

Axiom 2. Let P mean strong preference (similar to the relation > in mathematics); R - non-strict preference (similar to ratio ³); I - indifference (similar to the relation =). It is clear that R includes P and I. Axiom 2 requires two conditions to be satisfied:

1) connectivity: either xRy or yRx, or both;

2) transitivity: from xRy and yRz follows xRz.

Axiom 3. The two shown in Fig. 2.2 lotteries are in the attitude of indifference.

Rice. 2.2. Two lotteries in a relationship of indifference

The validity of this axiom is obvious. It is written in standard form as ((x, p, y)q, y)I (x, pq, y). Here on the left is a complex lottery, where with probability q we get a simple lottery, in which with probability p we get outcome x or with probability (1-p) - outcome y), and with probability (1-q) - outcome y.

Axiom 4. If xIy, then (x, p, z) I (y, p, z).

Axiom 5. If xPy, then xP(x, p, y)Py.

Axiom 6. If xPyPz, then there is a probability p such that y!(x, p, z).

All the above axioms are quite simple to understand and seem obvious.

Assuming that they are satisfied, the following theorem was proved: if axioms 1-6 are satisfied, then there is a numerical utility function U defined on A (set of outcomes) and such that:

1) xRy if and only if U(x) > U(y).

2) U(x, p, y) = pU(x)+(l-p)U(y).

The function U(x) is unique up to a linear transformation (for example, if U(x) > U(y), then a+U(x) > > a+U(y), where a is a positive integer) .

The general provisions of numerous varieties of rational choice theory are:

- - the assumption of intentionality;

- - assumption of rationality;

- - distinction between "complete" and "incomplete" information and, in the latter case, between "risk" and "uncertainty";

- - distinction between "strategic" and "interdependent" actions.

Rational choice theory presupposes intentionality. Rational choice explanations are really a subset of "intentional explanations." Intentional explanations do not simply assume that the individual is acting intentionally; rather, they explain social practices by referring to the respective beliefs and desires of individuals. Often intentional explanations are accompanied by a search for unexpected (or so-called "aggregated") consequences of people's intentional actions. In contrast to functionalist ways of explaining, the unexpected effects of social practices are not used to explain the sustainability of these same practices. Rational choice theorists pay special attention to two types of negative unintended consequences or "social contradictions": counter-finality and sub-optimality.

Counterfinality is associated with the "failure of composition" that occurs whenever people act on the erroneous assumption that what is optimal for any individual in a particular situation is simultaneously necessarily optimal for all individuals in that situation ( , 106; , 95).

Suboptimality refers to individuals who, under conditions of interdependent choices, choose a particular strategy, knowing that other individuals are doing the same, and also realizing that everyone can gain at least the same amount if a different strategy is adopted ( , 122). A striking example of suboptimality for two is the so-called prisoner's dilemma, which will be discussed later.

Second, in addition to intentionality, rational choice theories presuppose rationality. Rational choice explanations are in fact a subset of intentional explanations; they attribute, as the name suggests, rationality in social action. By rationality is meant, roughly speaking, that acting and interacting, the individual has an appropriate plan and seeks to maximize the totality of satisfactions of his preferences, while minimizing the corresponding costs. Thus, rationality implies a "connectedness assumption" that states that the individual involved has a complete "order of preference" with respect to various options. Based on these preference orders, social scientists can talk about a utility function that assigns a number to each option according to its rank within the preference order. For a person to be rational, his order of preference must satisfy certain requirements. The principle of transitivity is an obvious example of such a prerequisite: preference for X over Y and Y over Z must imply preference for X over Z. In the case where connectedness and transitivity are involved at the same time, rational choice theorists are on fire about "weak order of preference."

Rational choice explanations relate individual behavior to that individual's subjective beliefs and preferences, rather than to the objective conditions and opportunities facing him. Thus, it is possible for someone to act rationally based on false beliefs, which is opposed to the best ways to achieve someone's goals or desires. However, to call someone rational, he/she must gather enough information, within the bounds of what is possible, to make his/her beliefs valid. The endless collection of information can also be a sign of irrationality, especially if the situation is an emergency. For example, under conditions of direct military attack, a long study of possible strategies will have devastating consequences.

Third, there is a difference between uncertainty and risk. It is assumed that people know with some certainty the consequences of their actions. But in reality, people often have only partial information about the relationship between specific actions and consequences. Some theorists even take the position that there are no real life situations in which people can rely on complete information, because, as Burke wrote two centuries ago, "you can never plan the future based on the past." There is a difference within the framework of "incomplete information" between "uncertainty" and "risk" - this distinction was first made by M. Keynes, and rational choice theory seeks to study choice under uncertainty as choice under risk.

When faced with risk, people are able to attribute the likelihood of different outcomes, while when faced with uncertainty, they are unable to do so. Rational choice theorists tend to focus on risk for two reasons: either because they believe that situations of uncertainty do not exist, or because they believe that when such situations exist, rational choice theory cannot help people in their actions. Under conditions of risk, rational risk theory assumes that people are able to calculate the "expected utility" or "expected value" of each action.

Fourth, there is a difference between strategic and parametric choices. Excluding the above two types of social contradiction (indicative of "strategic" or "interdependent" choices), let's turn to parametric choices. They refer to the choices faced by individuals in environments independent of their choices. Sub-optimality and counter-finality are examples of strategic choices in which individuals must take into account choices made by others before determining their own course of action. Another example is that people who buy and sell stocks on the stock exchange tend to consider the choices of others before making their own decisions. As part of rational action theory, game theory deals with the formalization of interdependent or strategic choices. It constructs ideal-type models that provide for the rational decision of each player in a game where other players also make choices, and where each player must take into account the choices of others.

The Norwegian sociologist Ottar Broks (born 1932) set out to show what rational bases have local adaptations ("customs") that society considers traditional or traditionalist . As an example, he analyzes the fish bowl institution. On the north coast of Norway, once traditional on many, there was a fjord outlet to catch fish for dinner, as they said, "catch on the cauldron." Often the fishermen could catch more fresh fish than they could use, then the surplus had to be given to neighbors, friends or acquaintances. However, such "generosity" was not a manifestation of altruistic values, but an exchange within the framework of a barter economy. Later, the donor himself will receive the fish and other goods, or he will be helped in some other way when he needs it. This system of exchange relations was supported by customs and social norms. However, with the advent of the refrigerator, it has become more profitable to store fish than to “give away” it. Such new latent forms of action were used by people who were ready to break the rules and were not sensitive to sanctions. Thus, they can function as entrepreneurs, changing the existing system of interdependence.

Another prominent Scandinavian theorist in this field is Gudmund Hernes (born 1941), a student of Coleman who studied education and inequality and applied rational choice theory to the study of power and anarchy. On his initiative and under his leadership, a large-scale study of power relations in modern Norwegian society was carried out, commissioned and paid for by the Norwegian government. Hernes and his colleagues created a model for analyzing the processes taking place in the negotiation economy and in mixed administration .

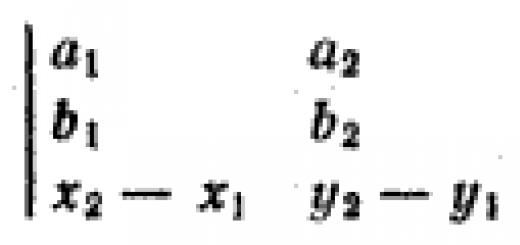

The central concepts of the Hernes model are power, interest and exchange. Actor A has power over B because A controls something that interests B, and vice versa. This interdependence forms the basis of exchange, as actors can make decisions while facing each other. Actors can give up control over something of lesser interest to them in order to gain control over something more significant. Hernes sums up the mutual dependency, power and bargaining power of the parties with the following formula:

A's direct power over B = A's control over item X + B's interest in item X = direct dependence of B on A ( , 14,).

A and B are not necessarily individuals, but rational actors cooperating in groups for their own benefit. Parliamentarians legislate and can therefore create relationships of exchange with those who value parliamentary votes. Farmers control food production and thus have leverage over the authorities and the consumer. Trade unions can exercise power through strike action. Henry Milner dealt with the problems of studying the relationship between social democratic politics and rational choice theory.

From the point of view of J. Elster, it is necessary to reject the functional explanation and replace them with combinations of intentional and causal explanations. Instead of postulating classes as collective actors, one should analyze the ways in which rational individuals unite in actions towards a common goal. Game theory, according to Elster, is acceptable for giving the macrotheories of Marxism a microfoundation.

The main peak of the crisis of behaviorism, structural-functional analysis and other main methodological trends occurred in the 60-70s. These years were full of attempts to find a new methodological basis for further research. Scientists have tried to do this in different ways:

update the "classical" methodological approaches (the emergence of post-behavioural methodological trends, neo-institutionalism, etc.);

create a system of "middle level" theories and try to use these theories as a methodological basis;

try to create the equivalent of a general theory by referring to classical political theories;

turn to Marxism and create on the basis of this various kinds of technocratic theories.

These years are characterized by the emergence of a number of methodological theories that claim to be the "grand theory". One of such theories, one of such methodological directions was the theory of rational choice.

Rational choice theory was designed to overcome the shortcomings of behaviorism, structural-functional analysis and institutionalism, creating a theory of political behavior in which a person would act as an independent, active political actor, a theory that would allow looking at a person’s behavior “from the inside”, taking into account the nature of his attitudes, choice of optimal behavior, etc.

The theory of rational choice came to political science from economic science. The “founding fathers” of the theory of rational choice are considered to be E. Downes (he formulated the main provisions of the theory in his work “The Economic Theory of Democracy”), D. Black (introduced the concept of preferences into political science, described the mechanism for their translation into performance results), G. Simon (substantiated the concept of bounded rationality and demonstrated the possibilities of applying the rational choice paradigm), as well as L. Chapley, M. Shubik, V. Riker, M. Olson, J. Buchanan, G. Tulloch (developed "game theory"). It took about ten years before rational choice theory became widespread in political science.

Proponents of rational choice theory proceed from the following methodological assumptions:

First, methodological individualism, that is, the recognition that social and political structures, politics, and society as a whole are secondary to the individual. It is the individual who produces institutions and relationships through his activity. Therefore, the interests of the individual are determined by him, as well as the order of preferences.

Secondly, the selfishness of the individual, that is, his desire to maximize his own benefit. This does not mean that a person will necessarily behave like an egoist, but even if he behaves like an altruist, then this method is most likely more beneficial for him than others. This applies not only to the behavior of an individual, but also to his behavior in a group when he is not bound by special personal attachments.

Supporters of the theory of rational choice believe that the voter decides whether to come to the polls or not, depending on how he evaluates the benefits of his vote, and also votes based on rational considerations of utility. He can manipulate his political settings if he sees that he may not get a win. Political parties in elections also try to maximize their benefits by enlisting the support of as many voters as possible. Deputies form committees, guided by the need to pass this or that bill, their people to the government, and so on. The bureaucracy in its activities is guided by the desire to increase its organization and its budget, and so on.

Thirdly, the rationality of individuals, that is, their ability to arrange their preferences in accordance with their maximum benefit. As E. Downs wrote, "every time we talk about rational behavior, we mean rational behavior, initially directed towards selfish goals" 12 . In this case, the individual correlates the expected results and costs and, trying to maximize the result, tries to minimize costs at the same time. Since the rationalization of behavior and the assessment of the ratio of benefits and costs require the possession of significant information, and its receipt is associated with an increase in overall costs, then one speaks of "bounded rationality" of the individual. This bounded rationality has more to do with the decision-making procedure itself than with the essence of the decision itself.

Fourth, the exchange of activities. Individuals in society do not act alone, there is an interdependence of people's choices. The behavior of each individual is carried out in certain institutional conditions, that is, under the influence of institutions. These institutional conditions themselves are created by people, but the initial one is people's consent to the exchange of activities. In the process of activity, individuals rather do not adapt to institutions, but try to change them in accordance with their interests. Institutions, in turn, can change the order of preferences, but this only means that the changed order turned out to be beneficial for political actors under given conditions.

Most often, the political process within the framework of the rational choice paradigm is described in the form of public choice theory, or in the form of game theory.

Proponents of the theory of public choice proceed from the fact that in the group the individual behaves selfishly and rationally. He will not voluntarily make special efforts to achieve common goals, but will try to use public goods for free (the “hare” phenomenon in public transport). This is because the nature of a collective good includes such characteristics as non-excludability (that is, no one can be excluded from the use of a public good) and non-rivalry (the consumption of this good by a large number of people does not lead to a decrease in its utility).

Game theorists assume that the political struggle to win, as well as the assumptions of rational choice theory about the universality of such qualities of political actors as selfishness and rationality, make the political process similar to a game with zero or non-zero sum. As is known from the course of general political science, game theory describes the interaction of actors through a certain set of game scenarios. The purpose of such an analysis is to search for such game conditions under which the participants choose certain strategies of behavior, for example, those that are beneficial to all participants at once 13 .

This methodological approach is not free from some shortcomings. One of these shortcomings is the insufficient consideration of social and cultural-historical factors influencing the individual's behavior. The authors of this manual are far from agreeing with researchers who believe that the political behavior of an individual is largely a function of the social structure or with those who argue that the political behavior of actors is in principle incomparable, because it occurs within the framework of unique national conditions and etc. However, it is obvious that the rational choice model does not take into account the influence of the sociocultural environment on the preferences, motivation and behavioral strategy of political actors, and does not take into account the influence of the specifics of political discourse.

Another shortcoming has to do with the assumption of rational choice theorists about the rationality of behavior. The point is not only that individuals can behave like altruists, and not only that they can have limited information, imperfect qualities. These nuances, as shown above, are explained by the rational choice theory itself. First of all, we are talking about the fact that often people act irrationally under the influence of short-term factors, under the influence of affect, guided, for example, by momentary impulses.

As D. Easton rightly points out, the broad interpretation of rationality proposed by the supporters of the theory under consideration leads to the blurring of this concept. More fruitful for solving the problems posed by the representatives of rational choice theory would be to single out types of political behavior depending on its motivation. In particular, “social-oriented” behavior in the interests of “social solidarity” 14 differs significantly from rational and selfish behavior.

In addition, rational choice theory is often criticized for some technical inconsistencies arising from the main provisions, as well as for the limited explanatory possibilities (for example, the applicability of the model of party competition proposed by its supporters only to countries with a two-party system). However, a significant part of such criticism either stems from a misinterpretation of the work of representatives of this theory, or is refuted by the representatives of rational choice theory themselves (for example, with the help of the concept of "bounded" rationality).

Despite these shortcomings, rational choice theory has a number of virtues which are the reason for its great popularity. The first undoubted advantage is that standard methods of scientific research are used here. The analyst formulates hypotheses or theorems based on a general theory. The method of analysis used by supporters of rational choice theory proposes the construction of theorems that include alternative hypotheses about the intentions of political actors. The researcher then subjects these hypotheses or theorems to empirical testing. If reality does not disprove theorems, that theorem or hypothesis is considered relevant. If the test results are unsuccessful, the researcher draws the appropriate conclusions and repeats the procedure again. The use of this technique allows the researcher to draw a conclusion about what actions of people, institutional structures and the results of the exchange of activities will be most likely under certain conditions. Thus, rational choice theory solves the problem of verifying theoretical propositions by testing scientists' assumptions about the intentions of political subjects.

As the well-known political scientist K. von Boime rightly notes, the success of rational choice theory in political science can be generally explained by the following reasons:

“neopositivist requirements for the use of deductive methods in political science are most easily satisfied with the help of formal models, on which this methodological approach is based

The rational choice approach can be used to analyze any type of behavior, from the actions of the most selfish rationalist to the infinitely altruistic activity of Mother Teresa, who maximized the strategy of helping the disadvantaged.

directions of political science, which are at the middle level between micro- and macrotheories, are forced to recognize the possibility of an approach based on the analysis of activity ( political subjects– E.M., O.T.) actors. The actor in the concept of rational choice is a construction that allows you to avoid the question of the real unity of the individual

rational choice theory promotes the use of qualitative and cumulative ( mixed - E.M., O.T.) approaches in political science

the rational choice approach acted as a kind of counterbalance to the dominance of behavioral research in previous decades. It is easy to combine it with multi-level analysis (especially when studying the realities of the countries of the European Union) and with ... neo-institutionalism, which became widespread in the 80s” 15 .

Rational choice theory has a fairly wide scope. It is used to analyze the behavior of voters, parliamentary activity and coalition formation, international relations, etc., and is widely used in modeling political processes.

The main peak of the crisis of behaviorism, structural-functional analysis and other main methodological trends occurred in the 60-70s. These years were full of attempts to find a new methodological basis for further research. Scientists have tried to do this in different ways:

1. to update the "classical" methodological approaches (the emergence of post-behavioral methodological trends, neo-institutionalism, etc.);

2. create a system of "middle level" theories and try to use these theories as a methodological basis;

3. try to create an equivalent of a general theory by referring to classical political theories;

4. turn to Marxism and create on the basis of this various kinds of technocratic theories.

These years are characterized by the emergence of a number of methodological theories that claim to be the "grand theory". One of such theories, one of such methodological directions was the theory of rational choice.

Rational choice theory was designed to overcome the shortcomings of behaviorism, structural-functional analysis and institutionalism, creating a theory of political behavior in which a person would act as an independent, active political actor, a theory that would allow looking at a person’s behavior “from the inside”, taking into account the nature of his attitudes, choice of optimal behavior, etc.

The theory of rational choice came to political science from economic science. The “founding fathers” of the theory of rational choice are considered to be E. Downes (he formulated the main provisions of the theory in his work “The Economic Theory of Democracy”), D. Black (introduced the concept of preferences into political science, described the mechanism for their translation into performance results), G. Simon (substantiated the concept of bounded rationality and demonstrated the possibilities of applying the rational choice paradigm), as well as L. Chapley, M. Shubik, V. Riker, M. Olson, J. Buchanan, G. Tulloch (developed "game theory"). It took about ten years before rational choice theory became widespread in political science.

Proponents of rational choice theory proceed from the following methodological assumptions:

First, methodological individualism, that is, the recognition that social and political structures, politics, and society as a whole are secondary to the individual. It is the individual who produces institutions and relationships through his activity. Therefore, the interests of the individual are determined by him, as well as the order of preferences.

Secondly, the selfishness of the individual, that is, his desire to maximize his own benefit. This does not mean that a person will necessarily behave like an egoist, but even if he behaves like an altruist, then this method is most likely more beneficial for him than others. This applies not only to the behavior of an individual, but also to his behavior in a group when he is not bound by special personal attachments.

Supporters of the theory of rational choice believe that the voter decides whether to come to the polls or not, depending on how he evaluates the benefits of his vote, and also votes based on rational considerations of utility. He can manipulate his political settings if he sees that he may not get a win. Political parties in elections also try to maximize their benefits by enlisting the support of as many voters as possible. Deputies form committees, guided by the need to pass this or that bill, their people to the government, and so on. The bureaucracy in its activities is guided by the desire to increase its organization and its budget, and so on.

Thirdly, the rationality of individuals, that is, their ability to arrange their preferences in accordance with their maximum benefit. As E. Downes wrote, "every time we talk about rational behavior, we mean rational behavior, initially directed towards selfish goals." In this case, the individual correlates the expected results and costs and, trying to maximize the result, tries to minimize costs at the same time. Since the rationalization of behavior and the assessment of the ratio of benefits and costs require the possession of significant information, and its receipt is associated with an increase in overall costs, then one speaks of "bounded rationality" of the individual. This bounded rationality has more to do with the decision-making procedure itself than with the essence of the decision itself.

Fourth, the exchange of activities. Individuals in society do not act alone, there is an interdependence of people's choices. The behavior of each individual is carried out in certain institutional conditions, that is, under the influence of institutions. These institutional conditions themselves are created by people, but the initial one is people's consent to the exchange of activities. In the process of activity, individuals rather do not adapt to institutions, but try to change them in accordance with their interests. Institutions, in turn, can change the order of preferences, but this only means that the changed order turned out to be beneficial for political actors under given conditions.

Most often, the political process within the framework of the rational choice paradigm is described in the form of public choice theory, or in the form of game theory.

Proponents of the theory of public choice proceed from the fact that in the group the individual behaves selfishly and rationally. He will not voluntarily make special efforts to achieve common goals, but will try to use public goods for free (the “hare” phenomenon in public transport). This is because the nature of a collective good includes such characteristics as non-excludability (that is, no one can be excluded from the use of a public good) and non-rivalry (the consumption of this good by a large number of people does not lead to a decrease in its utility).

Game theorists assume that the political struggle to win, as well as the assumptions of rational choice theory about the universality of such qualities of political actors as selfishness and rationality, make the political process similar to a game with zero or non-zero sum. As is known from the course of general political science, game theory describes the interaction of actors through a certain set of game scenarios. The purpose of such an analysis is to search for such game conditions under which participants choose certain behavioral strategies, for example, that are beneficial to all participants at once.

This methodological approach is not free from some shortcomings. One of these shortcomings is the insufficient consideration of social and cultural-historical factors influencing the individual's behavior. The authors of this manual are far from agreeing with researchers who believe that the political behavior of an individual is largely a function of the social structure or with those who argue that the political behavior of actors is in principle incomparable, because it occurs within the framework of unique national conditions and etc. However, it is obvious that the rational choice model does not take into account the influence of the sociocultural environment on the preferences, motivation and behavioral strategy of political actors, and does not take into account the influence of the specifics of political discourse.

Another shortcoming has to do with the assumption of rational choice theorists about the rationality of behavior. The point is not only that individuals can behave like altruists, and not only that they can have limited information, imperfect qualities. These nuances, as shown above, are explained by the rational choice theory itself. First of all, we are talking about the fact that often people act irrationally under the influence of short-term factors, under the influence of affect, guided, for example, by momentary impulses.

As D. Easton rightly points out, the broad interpretation of rationality proposed by the supporters of the theory under consideration leads to the blurring of this concept. More fruitful for solving the problems posed by the representatives of rational choice theory would be to single out types of political behavior depending on its motivation. In particular, “social-oriented” behavior in the interests of “social solidarity” differs significantly from rational and selfish behavior.

In addition, rational choice theory is often criticized for some technical inconsistencies arising from the main provisions, as well as for the limited explanatory possibilities (for example, the applicability of the model of party competition proposed by its supporters only to countries with a two-party system). However, a significant part of such criticism either stems from a misinterpretation of the work of representatives of this theory, or is refuted by the representatives of rational choice theory themselves (for example, with the help of the concept of "bounded" rationality).

Despite these shortcomings, rational choice theory has a number of virtues which are the reason for its great popularity. The first undoubted advantage is that standard methods of scientific research are used here. The analyst formulates hypotheses or theorems based on a general theory. The method of analysis used by supporters of rational choice theory proposes the construction of theorems that include alternative hypotheses about the intentions of political actors. The researcher then subjects these hypotheses or theorems to empirical testing. If reality does not disprove theorems, that theorem or hypothesis is considered relevant. If the test results are unsuccessful, the researcher draws the appropriate conclusions and repeats the procedure again. The use of this technique allows the researcher to draw a conclusion about what actions of people, institutional structures and the results of the exchange of activities will be most likely under certain conditions. Thus, rational choice theory solves the problem of verifying theoretical propositions by testing scientists' assumptions about the intentions of political subjects.

As the well-known political scientist K. von Boime rightly notes, the success of rational choice theory in political science can be generally explained by the following reasons:

1. “neopositivist requirements for the use of deductive methods in political science are most easily satisfied with the help of formal models, on which this methodological approach is based

2. The rational choice approach can be applied to the analysis of any type of behavior - from the actions of the most selfish rationalist to the infinitely altruistic activity of Mother Teresa, who maximized the strategy of helping the disadvantaged

3. directions of political science, which are on the middle level between micro- and macrotheories, are forced to recognize the possibility of an approach based on the analysis of activity ( political subjects– E.M., O.T.) actors. The actor in the concept of rational choice is a construction that allows you to avoid the question of the real unity of the individual

4. rational choice theory promotes the use of qualitative and cumulative ( mixed - E.M., O.T.) approaches in political science

5. The rational choice approach acted as a kind of counterbalance to the dominance of behavioral research in previous decades. It is easy to combine it with multi-level analysis (especially when studying the realities of the countries of the European Union) and with ... neo-institutionalism, which became widespread in the 80s.”

Rational choice theory has a fairly wide scope. It is used to analyze the behavior of voters, parliamentary activity and coalition formation, international relations, etc., and is widely used in modeling political processes.