The Versailles agreements put Germany in an extremely difficult situation. The country's armed forces were sharply limited. The German colonies were divided among themselves by the victors, and the bloodless German economy could henceforth rely only on those raw materials that were available on its greatly reduced territory. The country had to pay large reparations.

On January 30, 1921, a conference of the Entente countries and Germany concluded in Paris, establishing the total amount of German reparations at 226 billion gold marks, which must be paid over 42 years. On March 3, the corresponding ultimatum was handed to the German Foreign Minister. It contained a requirement to fulfill its conditions within 4 days. On March 8, having received no response to the ultimatum, Entente troops occupied Duisburg, Ruhrort and Düsseldorf; At the same time, economic sanctions were introduced against Germany. On May 5, the Entente countries presented Germany with a new ultimatum demanding that they accept all new proposals from the reparation commission within 6 days (to pay 132 billion marks over 66 years, including 1 billion immediately) and fulfill all the terms of the Versailles Treaty on disarmament and the extradition of the perpetrators of the world war. wars; otherwise, the Allied forces threatened to completely occupy the Ruhr area. On May 11, 1921, the office of Reich Chancellor Wirth, two hours before the expiration of the ultimatum, accepted the terms of the Allies. But only on September 30, French troops were withdrawn from the Ruhr. However, Paris never stopped thinking about this rich region.

The volume of reparations was beyond Germany's strength. Already in the fall of 1922, the German government turned to the Allies with a request for a moratorium on the payment of reparations. But the French government, headed by Poincaré, refused. In December, the head of the Rhine-Westphalian Coal Syndicate, Stinnes, refused to carry out reparations deliveries, even under the threat of Entente troops occupying the Ruhr. On January 11, 1923, a 100,000-strong Franco-Belgian contingent occupied the Ruhr Basin and the Rhineland.

The Ruhr (after Upper Silesia was taken away from Germany under the Treaty of Versailles) provided the country with about 80% of its coal, and more than half of German metallurgy was concentrated here. The struggle for the Ruhr region united the German nation. The government called for passive resistance, which, however, began without any calls. In the Ruhr, enterprises stopped working, transport and postal services did not work, and taxes were not paid. With the support of the army, guerrilla actions and sabotage began. The French responded with arrests, deportations and even death sentences. But this did not change the situation.

The loss of the Ruhr led to a worsening economic crisis throughout the country. Due to the lack of raw materials, thousands of enterprises stopped working, unemployment increased, wages decreased, and inflation increased: by November 1923, 1 gold mark was worth 100 billion paper. The Weimar Republic was shaking. On September 26, Chancellor Stresemann announced the end of passive resistance in the Ruhr area and the resumption of German reparations payments. On the same day, a state of emergency was declared. The refusal to resist the French activated right- and left-wing extremists, as well as separatists, in many areas of Germany. The communists blamed the government for the occupation of the Ruhr and called for civil disobedience and a general strike. With the help of the Reichswehr, the uprisings were suppressed in the bud, although there was blood: in Hamburg it came to barricade battles. In November 1923, the Communist Party was officially banned. On November 8–9, 1923, a coup attempt took place in Munich, organized by a previously little-known right-wing organization - the NSDAP.

From September 26, 1923 to February 1924, the Minister of Defense Gessler and the head of the Reichswehr ground forces, General von Seeckt, were given exceptional powers in Germany in accordance with the state of emergency. These powers in practice made the general and the army dictators of the Reich.

Great Britain and the United States were dissatisfied with France's intransigent position and insisted on negotiating to establish a more realistic amount of reparations. On November 29 in London, the reparations commission created two expert committees to study the issue of stabilizing the German economy and ensuring that it pays reparations. On August 16, 1924, a conference of European countries, the USA and Japan concluded its work there and adopted a new reparation plan by the American banker Charles Dawes.

In accordance with the Dawes Plan, France and Belgium evacuated troops from the Ruhr area (they began to do this on August 18, 1924 and finished a year later). A sliding schedule of payments was established (which gradually increased from 1 billion marks in 1924 to 2.5 billion in 1928–1929). The main source of covering reparations was supposed to be state budget revenues through high indirect taxes on consumer goods, transport and customs duties. The plan made the German economy dependent on American capital. The country was provided with 800 million marks as a loan from the United States to stabilize the currency. The plan was designed for German industrialists and traders to transfer their foreign economic activities to Eastern Europe. The adoption of the plan indicated the strengthening of US influence in Europe and the failure of France’s attempt to establish its hegemony.

Payment of reparations was to be made both in goods and in cash in foreign currency. To ensure payments, it was planned to establish Allied control over the German state budget, money circulation and credit, and railways. Control was carried out by a special committee of experts, headed by the general agent for reparations. Charles Dawes was called the savior of Europe, and in 1925 he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

On October 16, 1925, an international conference concluded in the Swiss city of Locarno, in which representatives of Great Britain, France, Belgium, Italy, Germany, Poland and Czechoslovakia participated. The conference adopted the Rhine Pact, which ensured the integrity of the borders between France, Belgium and Germany. The latter finally renounced its claims to Alsace and Lorraine, and France - its claims to the Ruhr region. The provision of the Treaty of Versailles on the demilitarization of the Rhineland was confirmed and the Dawes Plan was approved. By the way, the eastern German borders did not fall under the system of guarantees developed at Locarno, which was part of the anti-Soviet policy of the powers.

Chapter 5

Ruhr crisis and Soviet-German military-political negotiations in 1923

Despite the position put forward by Seeckt that military contacts should develop behind the back and without the knowledge of the German government, almost all the heads of the German cabinets were not only informed, but moreover, they approved and supported this cooperation. Chancellor Wirth provided the greatest support during the difficult period of his organizational development. Being at the same time the Minister of Finance, he found the necessary funds for the War Ministry (the so-called “blue budget”), accordingly organizing the “transmission” of the War Ministry budget through the Reichstag (1).

After his resignation in November 1922. Chancellor V. Cuno, with whom Seeckt had friendly relations, was immediately informed by the general about the existence of military contacts with Soviet Russia. He approved and, to the extent possible, also supported them. In general, for the political life of the Weimar Republic, it was quite remarkable that the frequent changes of cabinets practically did not affect the persons who occupied the most important government posts: the president, the minister of war, and the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Here the changes were minimal, which helped maintain continuity of leadership and the main guidelines of German policy. F. Ebert (1919-1925) and P. von Hindenburg (1925 - 1934) served as president for a long time (until his death); Minister of War - O. Gessler (1920 - 1928) and W. Groener (1928 - 1932); Commander-in-Chief of the Reichswehr - H. von Sect (1920 - 1926), W. Haye (1926-1930), K. von Hammerstein - Eckward (1930-1934).

The Cuno government's rise to power coincided with the deepening economic crisis in Germany from 1921 to 1923, rising unemployment and catastrophic inflation. In such conditions, fulfilling reparation obligations became one of the main problems for the Cuno government. His course was to evade paying reparations through the unrestrained issue of money (30 printing houses throughout Germany printed money around the clock. Inflation grew at a rate of 10% per hour. As a result, for one American dollar in January 1923 they gave 4.2 billion German marks ( 2)) led to a sharp deterioration in relations with France.

In such a situation, Germany decided to enlist the support of Soviet Russia, including the help of the Red Army in the event of an armed conflict with France. Under pressure from external conditions, Berlin tried to quickly complete negotiations with the Soviet government on establishing industrial cooperation, primarily the production of ammunition at Russian factories. To this end, on December 22, 1922, the German ambassador met in Moscow with the Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic, Trotsky.

Brockdorff-Rantzau posed two questions to Trotsky:

1. What wishes of an “economic-technical”, i.e. military, nature does Russia have in relation to Germany?

2. What political goals does the Russian government pursue in relation to Germany in this international situation and how will it react to violation of the treaty and military blackmail on the part of France?

Trotsky's answer completely satisfied the German ambassador: Trotsky agreed that "the economic construction of both countries is the main matter under all circumstances."

The ambassador recorded Trotsky's statements on the issue of a possible military action by France literally, noting that he meant the occupation of the Ruhr region:

“The moment France takes military action, everything will depend on how the German government behaves. Germany is currently unable to mount significant military resistance, but the government can make it clear through its actions that it is determined to prevent such violence. If Poland, at the call of France, invades Silesia, then we will by no means remain inactive; We cannot tolerate this and will stand up!”

In early January 1923, tensions between Germany and France reached their climax. Using as a pretext the refusal of the German authorities to supply coal and timber for reparation payments, France and Belgium sent troops into the Ruhr region on January 11, 1923 (3). A customs border, various duties, taxes and other restrictive measures were established. Cuno's government called for "passive resistance" to the occupying forces.

In this regard, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the USSR, in an appeal to the peoples of the whole world on January 13, 1923, noted: “The industrial heart of Germany has been captured by foreign enslavers. The German people have been dealt a new grave blow, and Europe is facing the threat of a new and cruel international massacre. At this critical moment, Workers' and Peasants' Russia cannot remain silent" (4).

On January 14, 1923, Seeckt, on his own initiative, met with Radek, who had “returned” from Norway to Berlin, and Hasse and Krestinsky were present. Seeckt pointed out the seriousness of the situation in connection with the occupation of the Ruhr region. He believed that this could lead to military clashes, and did not exclude the possibility of “some kind of action on the part of the Poles.” Therefore, without prejudging “the political issue of any joint political and military actions of Russia and Germany, he, as a military man, considered it his duty to speed up those steps to bring our military departments closer together, which were already discussed.”

In view of these events, Hasse's trip to Moscow could not take place at that moment, since, as the chief of the general staff, he had to be on the spot. Seeckt asked the USSR Military Department to urgently send its responsible representatives to Berlin for mutual information. Radek and Krestinsky promised this. In a letter to Moscow dated January 15, 1923, Krestinsky concluded that “a couple of responsible people should be sent here to continue conversations about the military industry and for other military conversations,” and asked to “urgently resolve” the issue of sending a delegation to Berlin (or “ commission,” as they said then. - S. G.). In those days, A.P. Rosengolts was in Berlin. He was "in constant contact" with Hasse. Rosengoltz agreed with the opinions of Radek and Krestinsky and on January 15 wrote a letter to Trotsky, nominating the most suitable, in his opinion, candidates for the trip.

Sect and Hasse familiarized Radek and Krestinsky with the “information they had about the situation near Memel and the mobilization activities of the Poles,” pointing to the mobilization of one Polish corps on the border with East Prussia.

“We agreed to keep each other informed about available<...>information of this kind"(5).

The capture of the Ruhr and Rhineland increased the danger of a new war. Military preparations began in Poland and Czechoslovakia, whose ruling circles were not averse to following France. January 20, 1923 Polish Foreign Minister A. Skrzynski said:

“If France called us to joint action, we would undoubtedly give our consent.”

On February 6, speaking in the Sejm, he threatened Germany with war and stated that if Germany continues to ignore the reparation problem, Poland will be more willing to fulfill its duty towards France (6).

The Soviet Union appealed to the governments of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia to remain neutral in the Ruhr conflict and warned that it would not tolerate their military actions against Germany.

In the report of the NKID to the Second Congress of Soviets of the USSR, Moscow’s position was defined as follows:

“The only thing that could force us to break away from peaceful labor and take up arms was precisely Poland’s intervention in the revolutionary affairs of Germany” (7).

The Ruhr crisis, which caused aggravation of contradictions between France, England and the United States, continued until the London Conference of 1924. Only after the adoption of the “Dauwes Plan”, which provided for the easing of reparation payments and the return of occupied territories and property to Germany, did French troops by August 1925 completely cleared the Ruhr region.

At the end of January 1923, a Soviet delegation led by Deputy Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the USSR Sklyansky arrived in Berlin in order to place orders for arms supplies. Zect tried to encourage the Soviet side to give clear guarantees in furtherance of the statement of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of January 13, 1923 about solidarity with Germany and in the event of a conflict with France and Poland to take its side. Sklyansky, however, made it clear that discussion of this issue was possible only after the Germans guaranteed military supplies. But since the German side rejected the application of the Soviet representatives for a loan of 300 million marks due to the fact that the entire secret weapons fund of the Reichswehr was approximately equal to this amount, the negotiations were interrupted and had to be resumed two weeks later in Moscow (8).

On February 22 - 28, 1923, negotiations between Soviet and German representatives continued in Moscow, where the “German Professor Geller Commission” arrived, consisting of seven people: professor-geodesist O. Geller (General O. Hasse), trigonometer W. Probst (Major W. Freiherr von Ploto), chemist Professor Kast (real name), director P. Wolf (captain 1st rank P. Wülfing (9)), surveyor W. Morsbach (Lieutenant Colonel W. Menzel (10)), engineer K. Seebach (Captain K. Student), merchant F. Teichmann (Major F. Tschunke (11)). They were received by Sklyansky, who was replacing Trotsky, who was then ill. The negotiations from the Soviet side included the Chief of Staff of the Red Army P. P. Lebedev, B. M. Shaposhnikov, Chairman of the Supreme Economic Council and Head of the Main Directorate of Military Industry (GUVP) Bogdanov, as well as Chicherin, Rosengolts.

When discussing operational issues, the Germans insisted on fixing the size of troops in the event of an offensive and joint actions against Poland using Lithuania as an ally. At the same time, Hasse spoke about a great “war of liberation” in the next three to five years. The German side tried to link its arms supplies with operational cooperation. Sklyansky insisted on resolving, first of all, the issue of German military supplies, followed by their payment in jewelry from the tsarist treasury and financial assistance, leaving the issue of agreements on a military alliance to the discretion of politicians. Bogdanov proposed that German specialists undertake the restoration of military factories existing on the territory of the USSR, and the Reichswehr placed orders for the supply of ammunition. Menzel, however, expressed doubt that the Reichswehr would be able to place orders and finance them. Wülfing proposed providing German captains to lead the Soviet fleet. For the Soviet side, the issue of armaments remained, however, the main, “cardinal point”, and it considered these negotiations as a “touchstone” of the seriousness of German intentions.

When did it become clear that

a) the German side is not able to provide significant assistance with weapons and

b) the Reichswehr is poorly armed, Lebedev, and then Rosengoltz, abandoned the statements obliging the Soviet side on joint operations against Poland. On February 28, leaving Moscow, the “German Professor Geller Commission” believed that these negotiations marked the beginning of operational cooperation and that the Soviet side was ready for it in the event of German concessions on the issue of arms supplies (12). On March 6, 1923, Chicherin, in a conversation with Rantzau, expressed deep disappointment that the Germans had completely abandoned the arms supplies they had promised. “The mountain gave birth to a mouse” - this is how Chicherin roughly put it.

In response to Rantzau’s probing on the results of negotiations regarding whether Soviet Russia would help Germany in its fight against France if Poland did not take any active action against Germany, Chicherin assured that Russia would not negotiate with France at the expense of Germany (13).

The last hope in case of continuation of “passive resistance,” as it seemed, was to be the resumption of Soviet-German military negotiations after Hasse’s letter to Rosengoltz dated March 25, 1923, in which he promised the Red Army assistance with military equipment and again mentioned the upcoming “war of liberation” . Chicherin convinced the German ambassador of approximately the same thing at the end of March and Radek in April. By mid-April 1923, the German Cuno government had virtually no control over the situation. In this situation, Seeckt, in his memorandum of April 16, addressed to the political leadership of Germany, again insisted on preparing Germany for a defensive war (14).

April 27 - 30, 1923: “Professor Geller’s commission” arrived in Moscow for the second time. It consisted of six people, headed by the head of the ground forces weapons department, Lieutenant Colonel V. Menzel. Again, everyone was under fictitious names: the merchant F. Teichmann (Major Tschunke), trigonometer W. Probst (Major W. F. von Ploto) and three industrialists: H. Stolzenberg (chemical factory "Stolzenberg"), director G. Thiele (" Rhine-metal") and director P. Schmerse ("Gutehoffnungshütte") (15). From the Soviet side, Sklyansky, Rosengoltz, members of the Supreme Economic Council M.S. Mikhailov-Ivanov and I.S. Smirnov, Lebedev, Shaposhnikov, and commander of the Smolensk division V.K. Putna took part in the negotiations. (16)

Negotiations at first, however, were slow and moved only after Menzel recorded on paper a promise to provide 35 million marks as Germany's financial contribution to the establishment of arms production in Russia. After this, German military experts were given the opportunity to inspect Soviet military factories for three weeks: the gunpowder factory in Shlisselburg, weapons factories in Petrograd (Putilov factories), Tula and Bryansk. To the surprise of the experts, they were in good condition, but needed financial support and orders. The German order list consisted mainly of hand grenades, cannons and ammunition. Rosengoltz sought its expansion with orders for aircraft engines, gas masks and poisonous gases.

During the negotiations, the issue was raised about the immediate delivery of 100 thousand rifles promised by Seeckt in the spring of 1922, but for the German side, the implementation of such a deal due to the restrictions of the Versailles Treaty turned out to be impossible; The parties refused to purchase Russian jewelry in third countries due to the high political risk. The Soviet side announced its intention to place orders in Germany for equipment worth 35 million gold rubles and expressed a wish to send officers of the German General Staff to the USSR to train the command staff of the Red Army. However, apparently, after tensions with France eased, the German side rejected these Soviet wishes (17).

Ultimately, during the April negotiations and after inspecting the relevant enterprises, two agreements were prepared, and on May 14, 1923, one of them was signed in Moscow - an agreement on the construction of a chemical plant for the production of toxic substances (Bersol Joint Stock Company). The text of the second agreement on the reconstruction of military factories in the USSR and the supply of artillery shells to the Reichswehr was also prepared.

In parallel with these negotiations, on the recommendation of Zecht, the head of the company Wenkhaus and Co., Brown, was in Moscow in order to explore the possibility of creating an enterprise for the production of weapons. It is interesting that the bank led by Brown was the German founder of “Rustransit” (Russian-German transit and trading society, German name - “Derutra”), formed on April 10, 1922. This society, according to the German researcher R. D. Muller, was called upon carry out important strategic tasks. In May - June 1922, the head of maritime transport of the German fleet, Captain 1st Rank V. Loman, in development of agreements with the RVS (Trotsky) on the return of German ships confiscated during the First World War, probed in Moscow the possibility of building submarines in Soviet shipyards . The fact is that Sklyansky told Ambassador Brockdorff-Rantzau that shipyards on the territory of the USSR could build submarines without foreign help, but they needed financial support (18).

However, due to the disorganization of Germany's finances and the difficult situation within the country, the ratification by the German government of the treaties reached in Moscow was delayed. Therefore, in mid-June, Chicherin pointed out this delay to the German ambassador and stated that military negotiations were “crucial for the future development of relations between Russia and Germany” (19). Then Brockdorff-Rantzau initiated an invitation to the Soviet delegation to Germany. He even went to Berlin for this and convinced Chancellor Cuno of this.

“It was Rantzau,” said Deputy People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs M.M. Litvinov to Plenipotentiary Representative Krestinsky on July 4, 1923, “who approached us with a proposal to send representatives to Berlin. He even gave Comrade Chicherin a personal letter from Cuno with the same proposal” (20).

Convincing Cuno of the need to hold negotiations in Berlin, Rantzau, however, was guided by the following considerations. He believed that in order to continue negotiations, the Soviet delegation should come to Berlin, since if the German “commission” traveled to Moscow for the third time in a row (which the German military insisted on), this would purely outwardly put the German side in the position of a supplicant. He proposed using the delay in Berlin to confirm the agreements reached in Moscow as a means of putting pressure on the Soviet side.

In mid-July 1923, Brockdorff-Rantzau came to Berlin to agree with Seeckt on a line of conduct for negotiations with Rosenholtz. By this time, Cuno had decided to take a firm line in the Ruhr conflict. Since it was impossible to delay the confirmation of the Moscow agreements, at the suggestion of Rantzau, at a meeting before negotiations with Rosengoltz, it was decided to promise an increase in financial assistance to Russia to 60, and then to 200 million marks in gold (21). The German side nevertheless tried to make its signing of treaties dependent on political concessions from Moscow.

She sought:

1) the German monopoly in the production of weapons in Russia, meaning the prohibition of any access of third countries to Soviet military factories (especially aviation ones) that were being restored with German assistance;

2) statements from Moscow about assistance in case of complications with Poland.

From July 23 to July 30, 1923 Rosengoltz (under the pseudonym Rashin) was in Berlin. Krestinsky, employees of the embassy I. S. Yakubovich and A. M. Ustinov took part in the negotiations. In a conversation on July 30, 1923, German Chancellor Cuno confirmed his intention to allocate 35 million marks, but made any further assistance conditional on the USSR fulfilling both conditions. Rosengoltz took note of the condition of the German monopoly, and with regard to the unilateral binding statement of German support in actions against Poland, he cited Sklyansky’s argument about the need to first obtain a sufficient number of weapons. Rosengoltz indicated that both sides have a strong air force and submarine fleet as a priority. Therefore, for now, they say, there is no need to rush. He proposed continuing military-political negotiations in Moscow. They were dissatisfied with the results of Rosenholtz's Berlin negotiations.

On this occasion, Radek, in his characteristic cynical and unceremonious manner, told the German ambassador in September 1923:

“You can’t think that for those lousy millions that you give us, we will unilaterally bind ourselves politically, and as for the monopoly that you claim for German industry, we are completely far from agreeing with this ; on the contrary, we take everything that can be useful to us militarily, and wherever we can find it. So, we bought airplanes in France, and we will also receive (military - S.G.) supplies from England” (22).

As a result of the negotiations, two previously prepared agreements were initialed on the production in the USSR (Zlatoust, Tula, Petrograd) of ammunition and military equipment and the supply of military materials to the Reichswehr, as well as on the construction of a chemical plant. The leadership of the Reichswehr announced its readiness to create a gold fund of 2 million marks to fulfill its financial obligations (23). Krestinsky informed Chicherin that the results “remain within the limits of the two agreements that were prepared in Moscow” (24). Taking into account the results of this series of German-Soviet negotiations, the leaders of the Reichswehr were ready to continue resistance in the Ruhr region while maintaining internal order in the country and at the same time seek economic assistance from England.

However, Cuno, under the influence of the aggravated internal situation caused by his policy of “passive resistance” and the threat of a general strike, resigned. August 13, 1923 G. Stresemann formed a grand coalition government with the participation of the SPD and set a course for changing foreign policy - abandoning the unilateral “Eastern orientation” and searching for a modus vivendi with France.

On September 15, 1923, President Ebert and Chancellor Stresemann unequivocally stated to Brockdorff-Rantzau that they were against the continuation of negotiations between Reichswehr representatives in Moscow, demanding that assistance in supplies to the Soviet defense industry be limited and that they try to direct it on a purely economic basis. However, despite the “cheerful” reports from Brockdorff-Rantzau in October 1923 that he had already succeeded, it was not so easy, if not impossible. It is no coincidence that Rantzau himself considered as a success the mere fact that he managed to achieve the cancellation of correspondence between the German War Ministry and the GEFU, initially carried out through Soviet diplomatic couriers and the NKID, and subsequently conduct it through the German embassy in Moscow (25).

After the Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr and the actual capture of Memel by Lithuania, as well as in view of the weakness of Germany, the leaders of the USSR feared that France could capture Germany and come close to the Soviet borders. Then, it was believed in Moscow, there would be a threat of a new Entente campaign to the East. Therefore, when Stresemann’s cabinet announced a rejection of the policy of the previous cabinet, Moscow also began to look for another way, namely, to stimulate the revolution in Germany.

The Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Comintern (ECCI) Zinoviev at the end of July - beginning of August 1923 simply broke Stalin and Kamenev, imposing on them in his letters from Kislovodsk - where he was with a group of other members of the Central Committee of the RCP (b) (Trotsky, Bukharin, Voroshilov , Frunze, etc.) was on vacation, - his ideas about the events taking place in Germany.

“In Germ. historical events and decisions are looming.”

“The crisis in Germany is brewing very quickly. A new chapter begins ( German) revolution. This will soon pose enormous challenges for us; the NEP will enter a new perspective. For now, the minimum that is needed is to raise the question

1) about the supply of it. communists with weapons in large numbers;

2) about the gradual mobilization of people. 50 of our best fighters to gradually send them to Germany. The time of enormous events in Germany is approaching. "(26) .

Stalin, based on the reports of Radek, who traveled throughout half of Germany in May 1923 (27), was much more realistic.

«<...>Should the communists strive (at this stage) to seize power without p. etc., whether they are already ripe for this - this, in my opinion, is the question.<...>If power in Germany now falls, so to speak, and the communists take it up, they will fail miserably. This is the “best” case. And in the worst case, they will be smashed to pieces and thrown back.<-. . >In my opinion, the Germans should be restrained, not encouraged” (28).

At the same time, in August 1923, a delegation of the KKE arrived in Moscow for negotiations with the Executive Committee of the Comintern and the leaders of the RCP (b).

And although even then there was a split in the “core” of the Central Committee of the RCP (b), Stalin eventually agreed with Zinoviev’s proposal. It was decided to help, and 300 million gold rubles were allocated from the Soviet budget (29). Lenin was already terminally ill at that time and was in Gorki. “Ilyich is gone,” Zinoviev stated in a letter to Stalin dated August 10, 1923 (30). It seems that they wanted to give a “gift” to the dying leader.

In August-September 1923, a “group of comrades” with extensive experience in revolutionary work was sent to Berlin. Under false names in Germany were Radek, Tukhachevsky, Unschlicht, Vatsetis, Hirschfeld, Menzhinsky, Trilisser, Yagoda, Skoblevsky (Rose), Stasova, Reisner, Pyatakov. Skoblevsky became the organizer of the “German Cheka” and the “German Red Army”, together with Hirschfeld he developed a plan for a series of uprisings in the industrial centers of Germany (31). Graduates and senior students of the Military Academy of the Red Army, sent to Germany, laid down bases with weapons and acted as instructors in the emerging fighting squads of the KKE (32). I. S. Unshlikht, F. E. Dzerzhinsky’s deputy in the OGPU, in letter No. 004 dated September 2, 1923, informed Dzerzhinsky that events were developing rapidly and “all (German - S. G.) comrades are talking about the imminent moment of capture authorities". Aware of the proximity of the moment, “they, however, swam with the flow,” without showing will and determination.

In this regard, Unschlicht wrote:

“Help is needed, but in a very cautious form, from people<...>those who know how to obey." He asked “for three weeks several of our people who know German<...>, Zalin in particular will be useful.”

On September 20, 1923, he again insisted on sending “Zalin and others” to Berlin, since “the matter is very urgent.”

“The situation is becoming more and more aggravated,” Unschlicht reported.<...>The catastrophic decline of the brand and the unprecedented rise in prices for basic necessities create a situation from which there is only one way out. That's what it's all about. We must help our comrades and prevent those mistakes and mistakes that we made at one time” (33).

The Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the USSR, Trotsky, would be included in the Russian section of the ECCI; on his orders, the territorial units of the Red Army, primarily the cavalry corps, began to advance to the western borders of the USSR, in order to, on the first order, move to the aid of the German proletariat and begin a campaign against Western Europe. The final stage was timed to coincide with a performance in Berlin on November 7, 1923, the 6th anniversary of the October Revolution in Russia (34).

On October 10 and 16, 1923, left-wing coalition governments (SPD and KPD) constitutionally came to power in the two states of Saxony and Thuringia.

Stalin’s letter to one of the leaders of the KKE, A. Talgenmer, published on October 10, 1923 in the KKE newspaper Rote Fahne, said:

“The approaching German revolution is one of the most important events of our days<...>. The victory of the German proletariat will undoubtedly transfer the center of the world revolution from Moscow to Berlin” (35).

However, at the decisive moment, the Chairman of the ECCI, Zinoviev, showed hesitation and indecision; mutually exclusive directives and instructions were sent from Moscow to Germany (36). Reichswehr units sent by order of President Ebert entered Saxony on October 21 and Thuringia on November 2. By Ebert's decree of October 29, the socialist government of Saxony was dissolved. The workers' government of Thuringia suffered the same fate. The power of the military administration was temporarily established there. The armed uprising that began on October 22, 1923 under the leadership of the KPD in Hamburg was suppressed by October 25. The “October Revolution” did not take place in Germany (37). Skoblevsky was arrested in Germany by the police at the beginning of 1924.

On November 9, 1923, the notorious “Beer Hall Putsch” of A. Hitler was organized in Munich. This was the first attempt by the Nazis and reactionary generals (E. Ludendorff) to come to power through a coup d'etat. However, then the Weimar Republic managed to survive. On the same day, executive power in Germany was transferred to Seeckt. It seemed that he was destined to become the next Chancellor of Germany. The German archives preserved a draft of his government statement, in which the line on relations with Moscow was formulated as follows:

“Development of economic and political (military) relations with Russia” (38).

However, it was not Seeckt, but W. Marx who replaced Stresemann as Chancellor of the Weimar Republic.

In December 1923, in Germany, Ruth Fischer published documents demonstrating the scale of Moscow’s “help” in organizing the “German October”. The Germans then demanded the expulsion of the military agent of the USSR Embassy in Berlin, M. Petrov, who had organized the purchase of weapons for the KKE with Soviet money - allegedly for the Red Army (39). The “Petrov case” and then the “Skoblevsky case,” the trial of which took place in Leipzig in the spring of 1925 (the famous “Cheka case” (40)), were a response to the attempt to blow up Germany with the help of revolution. The German government used them as an additional, but effective reason to change its policy towards a gradual departure from the unilateral “Eastern orientation” and a careful balancing between the West and the East, using the USSR as a support in relations with the Entente. Berlin took into account that too much cooling in relations with the USSR would be to the advantage of the Entente. Thus, in the future, “Eastern orientation” remained a relevant direction, especially since not only Brockdorff-Rantzau and Seeckt, but also in government circles and in the bourgeois parties of Germany, the negative attitude towards a turn to the West was very strong.

"Passive resistance"

The occupation of the Ruhr led to a policy of "passive resistance" for Germany. She was proclaimed head of the Cuno government on January 13, 1923 in the Reichstag. It was approved by the majority of deputies and Ruhr industrialists led by Stinnes.

However, German politicians and industrialists did not imagine the real consequences of such a policy. Paris strengthened the occupation army and expanded the occupation zone. The French occupied Düsseldorf, Bochum, Dortmund and other rich industrial centers of the Ruhr region. They began a policy of isolating the Ruhr from Germany and other countries. The commander of the occupation forces, General Degoutte, banned the export of coal from the Ruhr to Germany. As a result, Germany lost 88% of coal, 48% of iron, 70% of cast iron. Germany was under threat of economic collapse. The fall of the German mark became catastrophic, and money depreciated at an unprecedented rate. In addition, the French began repression. Some coal miners, including Fritz Thyssen, were arrested. Krupp was warned about the sequestration of his enterprises. There was a wave of arrests of German government officials in the Ruhr and Rhineland regions.

As a result, the Cuno government's attempt to put pressure on France through diplomatic means failed. The protests of the German authorities regarding the arrests in the Ruhr region in Paris were rejected and recognized as completely legitimate. Hopes for help from England were initially also not justified. In England they expressed sympathy for Germany and condemned the policies of France, but did not want to be drawn into the conflict. British diplomacy also refused mediation.

Meanwhile, the crisis in Germany had a negative impact on England and throughout Europe. The decline in the purchasing power of the German population led to a fall in English exports and an increase in unemployment in England. At the same time, the French franc began to fall. All this caused disorganization of the European market. In Germany, there was a sharp increase in right-wing radical, nationalist and revanchist movements and organizations. Throughout Germany and especially in Bavaria, secret and overt organizations of a military and nationalist nature were formed.

All this caused alarm in Europe. On April 15, 1923, Poincaré, in a speech in Dunkirk, confirmed the validity of France's Ruhr policy. From his point of view, the occupation of the Ruhr was justified not only from economic, but also from political and military necessity. According to Poincaré, after four German invasions in one century, France has the right to ensure its security. Belgium supported France on this issue.

Due to the worsening situation in Europe and under pressure from public opinion, London took a more active position. On April 21, 1923, Lord Curzon gave a speech in the House of Lords in which he advised Berlin to submit new proposals on the problem of reparations. On April 22, 1923, the German Foreign Ministry announced that it was ready to consider the reparation issue, but only in connection with the recognition of German sovereignty over the Rhine and Ruhr. On May 2, 1923, the German government sent a note with proposals on the reparation issue to Belgium, France, England, Italy, the USA and Japan. Germany agreed to set the total amount of obligations at 30 billion marks in gold, while the entire amount had to be covered with the help of foreign loans. But Berlin warned that passive resistance to Germany would continue until the occupation was ended. Germany proposed solving the reparations problem at the level of an international commission. The Germans referred to the speech of the American Secretary of State Hughes, who, in order to solve the reparations issue, proposed turning to experts, people who enjoy high authority in the financial problems of their country.

The German proposal sparked a new diplomatic scramble. France and Belgium believed that negotiations were impossible until the end of passive resistance and that they were not going to change their decisions. In addition, Germany was accused of “revolting against the Treaty of Versailles.” England invited Germany to provide more “serious and clear evidence of its willingness to pay than has been the case so far.” The Japanese reported that for Japan this issue was not of “vital importance” and proposed to solve the problem peacefully.

On June 7, 1923, Germany proposed a new memorandum to the Entente countries. It was proposed to pay reparations with bonds in the amount of 20 billion gold marks, which were secured by state railways and other property. But France was again in no hurry to respond. She again inserted a preliminary condition - the cessation of passive resistance.

England began to advocate for ending the Ruhr conflict more persistently. In May 1923, a change of cabinet took place in Britain: the resignation of Bonar Law and the appointment of Baldwin as Prime Minister. The new prime minister leaned on commercial and industrial circles and persistently sought to eliminate the Ruhr conflict. The English press began to actively argue that the financial chaos, industrial and social collapse of Germany would prevent the restoration of the economic balance of Europe and, accordingly, England.

The Ruhr conflict led to the strengthening of negative political trends in Europe. Fascist Italy, taking advantage of the Ruhr crisis, tried to begin expansion in the Mediterranean basin. The Italian government laid claim to the entire eastern Adriatic coast. The slogan was put forward to transform the Adriatic Sea into the Italian Sea. Radical politicians demanded the inclusion of a large part of Yugoslavia into the Italian Empire. Yugoslavia was declared the Italian “Saint Dalmatia”. On this wave, the Italians occupied Fiume. Italy and Yugoslavia considered this unrecognized state, proclaimed on September 8, 1920, by the Italian poet Gabriele d'Annunzio, their territory. Having not received the support of Paris, which was busy with the Ruhr problem, Yugoslavia was forced to abandon its claims to Fiume in favor of Rome. At the same time, the Italians occupied Corfu and only under pressure from England, which considered the island the key to the Adriatic Sea, did they withdraw their troops.

At this time, revolutionary chaos was growing in Germany. In August 1923, a huge strike began in the Ruhr region; more than 400 thousand workers began protests and demanded the departure of the occupiers. This strike was supported by all workers in Germany and led to another political crisis. The threat of armed confrontation has already arisen. Cuno's government resigned. As a result, the Stresemann-Hilferding coalition government was formed. In his keynote speech in Stuttgart on September 2, 1923, Stresemann stated that Germany was ready to enter into an economic agreement with France, but it would resolutely oppose attempts to dismember the country. The French softened their position and said they were ready to discuss the problem. At the same time, France again reported that it was necessary to stop passive resistance. Stresemann noted that the German government could not achieve an end to passive resistance until the Ruhr problem was resolved.

After active German-French negotiations, the German government published a declaration on September 26, 1923, in which it invited the population of the Ruhr to stop passive resistance. The general economic crisis and the growing revolutionary movement in the country forced Berlin to capitulate. Speculating on the possibility of a social revolution, the German government put pressure on the Entente countries. In the autumn of 1923, the situation in Germany was indeed very difficult. In Saxony, left-wing Social Democrats and Communists created a workers' government. The same government was established in Thuringia. Germany stood on the threshold of a revolutionary explosion. However, the government reacted harshly. Troops and right-wing paramilitaries were sent to the rebel provinces. The workers of the republic were defeated. The uprising was also suppressed in Hamburg. The German bourgeois government, with the support of part of the Social Democrats, won. But the situation remained difficult.

Continuation of the crisis. Failure of French plans

The world community assessed the surrender of Germany as the second war lost by the Germans. It seemed that Poincaré was close to his intended goal. Paris seized the initiative in resolving the reparations issue and a leading place in European politics. The French Prime Minister hoped to create a German-French coal-iron syndicate, which would be led by French capital. This gave France economic dominance in Western Europe and the material basis for military leadership on the continent.

However, Poincaré was mistaken in believing that France had won. The Germans had no intention of yielding to France. The abandonment of the policy of passive resistance was a chess move. Berlin expected that London, alarmed by the strengthening of Paris, would definitely intervene. And the French were not satisfied with this victory. They wanted to build on their success. This caused discontent in England. On October 1, 1923, Baldwin strongly condemned the intransigent position of the French government. British Foreign Minister Curzon generally stated that the only result of the occupation was the economic collapse of the German state and the disorganization of Europe.

London enlisted the support of Washington and launched a diplomatic counteroffensive. On October 12, 1923, the British formally demanded a conference to resolve the reparations issue with the participation of the United States. The British note emphasized that the United States could not remain aloof from European problems. According to the British government, it was necessary to return the declaration of the American Secretary of State Hughes. America was to be the judge in deciding the question of reparations. England proposed convening an international conference with the participation of the United States.

Soon the United States announced that it would willingly take part in such a conference. Thus, the Anglo-Saxons lured France into a well-prepared trap. Following the US announcement, the British government advised Poincaré to "think carefully" before refusing the offer.

However, the French persisted. Poincaré planned to support the separatists in Germany in order to create buffer formations between France and Germany. The French supported secessionist movements on the Rhine and in Bavaria. Poincaré's plans were based on the plans of Marshal Foch, who proposed creating a Rhineland buffer state. However, the other Entente powers rejected this plan in 1919. Foch also proposed in 1923 to seize the Ruhr and the Rhineland.

Industrialists in the Rhine-Westphalia region supported the idea of creating a Rhineland state. The French High Commissioner for the Rhineland, Tirard, reported to Poinqueret that industrialists and merchants in Aachen and Mainz were clearly gravitating toward France. Many Rhenish and Westphalian firms had more ties to France than to Germany. After the occupation of the Ruhr, they were completely cut off from German markets and reoriented towards France. In addition, the revolutionary movement in Germany caused fear among a certain part of the bourgeoisie. On the night of October 21, 1923, the separatists announced the establishment of an “independent Rhine Republic.”

Almost simultaneously, the separatist movement in Bavaria intensified. The separatists were led by the Catholic Bavarian People's Party, led by Kahr. The Bavarians planned, together with the “Rhine Republic” and Austria, with the support of France, to create a Danube confederation. Kar hoped that the separation of Bavaria would allow it to be freed from paying reparations and to receive loans from the Entente powers. The Bavarians held secret negotiations with the representative of the French General Staff, Colonel Richer. The French promised the Bavarian separatists assistance and full support. But the plans of the separatists were discovered by the German authorities, so Poincaré had to dissociate himself from Richer and his plans.

However, the Bavarian separatists did not give up and in mid-October 1923, Bavaria actually separated from Germany. The units of the Reichswehr (armed forces) located in Bavaria were headed by General Lossow, who refused to obey the orders of the military command. The supreme ruler of Bavaria, Kahr, began negotiations with France. To England's request, Poincaré replied that he was not responsible for what was happening inside Germany. During a speech on November 4, 1923, Poincaré said that France did not consider itself obliged to protect the German constitution and the unity of Germany. The head of the French government recalled the “sacred principle” of self-determination of nations.

The situation was further aggravated by the Nazi putsch on November 8-9, 1923 (). The catastrophic situation in Germany and the massive impoverishment of the population led to the growth of nationalist sentiments, which were used to their advantage by representatives of large German capital. Nationalists were especially active in Bavaria, where they entered into a tactical alliance with the Bavarian separatists (the National Socialists supported the idea of a united Greater Germany). The nationalists organized battle groups and sent them to the Ruhr region in order to turn passive resistance into active. The militants caused explosions on railways, accidents, attacked single French soldiers, and killed representatives of the occupation authorities. Hitler and Ludendorff attempted to seize power in Munich on November 8, 1923. Hitler hoped to organize a “march on Berlin” in Bavaria, repeating Mussolini’s success in 1922. But the “beer hall putsch” failed.

Meanwhile, Germany's economic situation worsened. The occupation of the Ruhr was an ill-considered step and led to a crisis in the French economy. Germany, even after the cessation of passive resistance, did not pay reparations and did not fulfill supply obligations. This had a heavy impact on the French state budget and on the exchange rate of the franc. In addition, the costs of the occupation were constantly growing and by the autumn of 1923 they reached 1 billion francs. Poincaré tried to delay the fall of the franc by increasing taxes by 20%. But this step did not improve the situation. In addition, the British carried out financial sabotage - English banks threw a significant amount of French currency into the money market. The franc exchange rate fell even more. Under financial and diplomatic pressure from England and the United States, France had to capitulate. Poincaré announced that France no longer objects to the convening of an international committee of experts on the problem of German reparations.

Dawes Plan

After much delay, France agreed to the opening of the committee's work. On January 14, 1924, an international committee of experts began work in London. US Representative Charles Dawes was chosen as its chairman. A former lawyer who received the rank of general for his participation in the war, Dawes was closely associated with the Morgan banking group. It was this group that France turned to for a loan. Morgan promised Paris a loan of $100 million, but on the condition that the issue of German reparations be resolved.

During the committee meeting, the main focus was on the problem of creating a stable currency in Germany. The Americans especially insisted on this. The British also supported them in this matter. The Dawes Commission visited Germany to study the situation of German finances. Experts came to the conclusion that Germany's solvency will be restored only if the entire country is reunified.

On April 9, 1924, Dawes announced the completion of the work and presented the text of the experts' report. The so-called Dawes Plan consisted of three parts. In the first part, the experts made general conclusions and conveyed the committee’s point of view. The second part was devoted to the general economic situation in Germany. The third part contained a number of appendices to the first two parts.

Experts believed that Germany would be able to pay reparations only after economic recovery. To do this, the country needed help. This should have been done by Anglo-American capital. Priority was given to stabilizing the currency and creating fiscal balance. To stabilize the German mark, it was proposed to provide Berlin with an international loan in the amount of 800 million gold marks. Germany had to pledge customs duties, excise taxes and the most profitable items of the state budget as collateral. All railways were transferred to a joint stock company of railways for 40 years. The total amount of reparation payments and the deadline for their payment have not been established. Berlin only had to promise to pay 1 billion marks in the first year. Then Germany had to increase contributions and bring them to 2.5 billion marks by the end of the 1920s. The sources of covering reparation payments were the state budget, income from heavy industry and railways. In general, the entire burden of reparations fell on ordinary workers (large German capital insisted on this); they were taken away through special taxes.

It should be noted that these taxes began to be used in Germany for widespread demagogic, chauvinistic propaganda. The German capitalists kept silent about the fact that they themselves did not want to lose their profits and found ways to reimburse reparation payments at the expense of ordinary people. External enemies were declared to be to blame for the people's plight, and a new war was supposed to be the main means of getting rid of disasters.

Overall, the Dawes Plan provided for the restoration of a strong Germany. At the same time, Anglo-American capital, in alliance with part of large German capital, was going to control the main sectors of the German national economy. To ensure that there was no competition from German goods in markets dominated by British, American and French capital, the authors of the Dawes Plan “generously” provided Germany with Soviet markets. The plan was quite cunning, the masters of the West protected their markets from the powerful German economy and directed the economic and, in the future, military expansion of the Germans to the east.

On August 16, 1924, at the London Conference, a reparation plan for Germany was approved. In addition, several important issues were resolved at the conference. France lost the opportunity to independently resolve the issue of reparations; all conflict issues had to be resolved by an arbitration commission of representatives of the Entente, headed by American representatives. France was supposed to withdraw troops from the Ruhr within a year. Instead of military intervention, financial and economic intervention was launched. An emission bank was created under the control of a foreign commissioner. The railways passed into private hands and were also managed under the control of a special foreign commissioner. France retained the right to compulsorily receive coal and other manufactured goods for a certain period of time. But Germany received the right to appeal to an arbitration commission demanding a reduction or cancellation of these supplies. Germany was provided with a loan of 800 million marks. It was provided by Anglo-American capital.

Thus, the London Conference of 1924 established the dominance of Anglo-American capital in Germany and, accordingly, in Europe. Germany was sent east. With the help of the Dawes Plan, the Anglo-Saxons hoped to turn Soviet Russia into an agricultural and raw materials appendage of the industrial West.

withdrawal of French troops from Germany

| unknown | unknown |

Ruhr conflict- the climax of the military-political conflict between the Weimar Republic and the Franco-Belgian occupation forces in the Ruhr Basin in 1923.

Write a review about the article "Ruhr Conflict"

Literature

- Michael Ruck: Die Freien Gewerkschaften im Ruhrkampf 1923, Frankfurt am Main 1986;

- Barbara Muller: Passive Widerstand im Ruhrkampf. Eine Fallstudie zur gewaltlosen zwischenstaatlichen Konfliktaustragung und ihren Erfolgsbedingungen, Münster 1995;

- Stanislas Jeannesson: Poincaré, la France et la Ruhr 1922-1924. Histoire d'une occupation, Strasbourg 1998;

- Elspeth Y. O'Riordan: Britain and the Ruhr crisis,London 2001;

- Conan Fischer: The Ruhr Crisis, 1923-1924, Oxford/New York 2003;

- Gerd Krumeich, Joachim Schröder (Hrsg.): Der Schatten des Weltkriegs: Die Ruhrbesetzung 1923, Essen 2004 (Düsseldorfer Schriften zur Neueren Landesgeschichte und zur Geschichte Nordrhein-Westfalens, 69);

- Gerd Krüger: "Aktiver" und passiver Widerstand im Ruhrkampf 1923, in: Besatzung. Funktion und Gestalt militärischer Fremdherrschaft von der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, hrsg. von Günther Kronenbitter, Markus Pöhlmann und Dierk Walter, Paderborn / München / Wien / Zürich 2006 (Krieg in der Geschichte, 28) S. 119-130.

Links

Excerpt characterizing the Ruhr conflict

On October 28, Kutuzov and his army crossed to the left bank of the Danube and stopped for the first time, putting the Danube between themselves and the main forces of the French. On the 30th he attacked Mortier’s division located on the left bank of the Danube and defeated it. In this case, trophies were taken for the first time: a banner, guns and two enemy generals. For the first time after a two-week retreat, the Russian troops stopped and, after a struggle, not only held the battlefield, but drove out the French. Despite the fact that the troops were stripped, exhausted, weakened by one third, backward, wounded, killed and sick; despite the fact that the sick and wounded were left on the other side of the Danube with a letter from Kutuzov, entrusting them to the philanthropy of the enemy; despite the fact that the large hospitals and houses in Krems, converted into infirmaries, could no longer accommodate all the sick and wounded, despite all this, the stop at Krems and the victory over Mortier significantly raised the morale of the army. Throughout the entire army and in the main quarters, the most joyful, although unfair, rumors were circulating about the imaginary approach of columns from Russia, about some kind of victory won by the Austrians, and about the retreat of the frightened Bonaparte.Prince Andrei was during the battle with the Austrian general Schmitt, who was killed in this case. A horse was wounded under him, and he himself was slightly grazed in the arm by a bullet. As a sign of the special favor of the commander-in-chief, he was sent with news of this victory to the Austrian court, which was no longer in Vienna, which was threatened by French troops, but in Brunn. On the night of the battle, excited, but not tired (despite his weak-looking build, Prince Andrei could endure physical fatigue much better than the strongest people), having arrived on horseback with a report from Dokhturov to Krems to Kutuzov, Prince Andrei was sent that same night courier to Brunn. Sending by courier, in addition to rewards, meant an important step towards promotion.

The night was dark and starry; the road turned black between the white snow that had fallen the day before, on the day of the battle. Now going over the impressions of the past battle, now joyfully imagining the impression that he would make with the news of victory, remembering the farewell of the commander-in-chief and comrades, Prince Andrei galloped in the mail chaise, experiencing the feeling of a man who had waited for a long time and had finally achieved the beginning of the desired happiness. As soon as he closed his eyes, the firing of rifles and cannons was heard in his ears, which merged with the sound of wheels and the impression of victory. Then he began to imagine that the Russians were fleeing, that he himself had been killed; but he quickly woke up, with happiness as if he learned again that none of this had happened, and that, on the contrary, the French had fled. He again remembered all the details of the victory, his calm courage during the battle and, having calmed down, dozed off... After the dark starry night, a bright, cheerful morning came. The snow melted in the sun, the horses galloped quickly, and new and varied forests, fields, and villages passed indifferently to the right and left.

At one of the stations he overtook a convoy of Russian wounded. The Russian officer driving the transport, lounging on the front cart, shouted something, cursing the soldier with rude words. In the long German vans, six or more pale, bandaged and dirty wounded were shaking along the rocky road. Some of them spoke (he heard Russian dialect), others ate bread, the heaviest ones silently, with meek and painful childish sympathy, looked at the courier galloping past them.

Prince Andrei ordered to stop and asked the soldier in what case they were wounded. “The day before yesterday on the Danube,” answered the soldier. Prince Andrei took out his wallet and gave the soldier three gold coins.

“For everyone,” he added, turning to the approaching officer. “Get well, guys,” he addressed the soldiers, “there’s still a lot to do.”

- What, Mr. Adjutant, what news? – the officer asked, apparently wanting to talk.

- Good ones! “Forward,” he shouted to the driver and galloped on.

It was already completely dark when Prince Andrey entered Brunn and saw himself surrounded by tall buildings, the lights of shops, house windows and lanterns, beautiful carriages rustling along the pavement and all that atmosphere of a large, lively city, which is always so attractive to a military man after the camp. Prince Andrei, despite the fast ride and sleepless night, approaching the palace, felt even more animated than the day before. Only the eyes sparkled with a feverish brilliance, and thoughts changed with extreme speed and clarity. All the details of the battle were vividly presented to him again, no longer vaguely, but definitely, in a condensed presentation, which he made in his imagination to Emperor Franz. He vividly imagined random questions that could be asked of him, and the answers that he would make to them. He believed that he would immediately be presented to the emperor. But at the large entrance of the palace an official ran out to him and, recognizing him as a courier, escorted him to another entrance.

- From the corridor to the right; there, Euer Hochgeboren, [Your Highness,] you will find the adjutant on duty,” the official told him. - He takes you to the Minister of War.

The adjutant on duty in the wing, who met Prince Andrei, asked him to wait and went to the Minister of War. Five minutes later, the aide-de-camp returned and, bending especially courteously and letting Prince Andrei go ahead of him, led him through the corridor into the office where the Minister of War was working. The aide-de-camp, with his exquisite politeness, seemed to want to protect himself from the Russian adjutant’s attempts at familiarity. Prince Andrei's joyful feeling weakened significantly when he approached the door of the War Minister's office. He felt insulted, and the feeling of insult at that same moment, unnoticed by him, turned into a feeling of contempt, based on nothing. His resourceful mind at the same moment suggested to him the point of view from which he had the right to despise both the adjutant and the minister of war. “They must find it very easy to win victories without smelling gunpowder!” he thought. His eyes narrowed contemptuously; He entered the office of the Minister of War especially slowly. This feeling intensified even more when he saw the Minister of War sitting over a large table and for the first two minutes did not pay attention to the newcomer. The Minister of War lowered his bald head with gray temples between two wax candles and read, marking with a pencil, the papers. He finished reading without raising his head, when the door opened and footsteps were heard.

“Take this and hand it over,” the Minister of War said to his adjutant, handing over the papers and not yet paying attention to the courier.

Prince Andrei felt that either of all the affairs that occupied the Minister of War, the actions of Kutuzov’s army could least of all interest him, or it was necessary to let the Russian courier feel this. “But I don’t care at all,” he thought. The Minister of War moved the rest of the papers, aligned their edges with the edges and raised his head. He had a smart and characteristic head. But at the same moment as he turned to Prince Andrei, the intelligent and firm expression on the face of the Minister of War, apparently habitually and consciously changed: the stupid, feigned, not hiding his pretense, smile of a man who receives many petitioners one after another stopped on his face .

– From General Field Marshal Kutuzov? - he asked. - Good news, I hope? Was there a collision with Mortier? Victory? It's time!

He took the dispatch, which was addressed to him, and began to read it with a sad expression.

As early as March 1921, the French occupied Duisburg and Düsseldorf in the Rhineland demilitarized zone. This paved the way for France to further occupy the entire industrial area, and since the French now had control of the ports of Duisburg, they knew exactly how much coal, steel and other products were being exported. They were not satisfied with the way Germany fulfilled its obligations. In May, a London ultimatum was put forward, which set a schedule for the payment of reparations in the amount of 132 billion gold marks; in case of non-compliance, Germany was threatened with the occupation of the Ruhr.

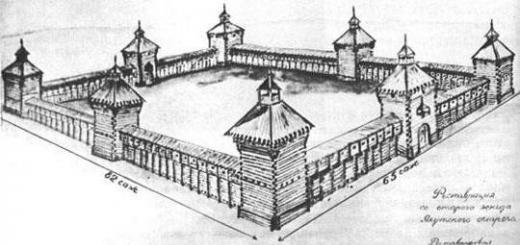

Administered and occupied territories of Germany. 1923

Then the Weimar Republic followed the “policy of execution” - following demands so that their impossibility became obvious. Germany was weakened by the war, the economy was in ruins, inflation was rising, and the country was trying to convince the victors that their appetites were too high. In 1922, seeing the deterioration in the economy of the Weimar Republic, the allies agreed to replace cash payments with natural ones - wood, steel, coal. But in January 1923, the international reparations commission declared that Germany was deliberately delaying deliveries. In 1922, instead of the required 13.8 million tons of coal, there were only 11.7 million tons, and instead of 200,000 telegraph masts, only 65,000. This became the reason for France to send troops into the Ruhr basin.

Caricature of Germany paying reparations

Even before the entry of troops into Essen and its environs on January 11, large industrialists left the city. Immediately after the start of the occupation, the German government recalled its ambassadors from Paris and Brussels, and the invasion was declared “the violent policy of France and Belgium, contrary to international law.” Germany accused France of violating the treaty and declared a “war crime.” Britain chose to remain outwardly indifferent, while convincing the French of its loyalty. In fact, England hoped to pit Germany and France against each other, eliminate them and become the political leader in Europe. It was the British and Americans who advised the Weimar Republic to pursue a policy of “passive resistance” - to fight against France’s use of the economic wealth of the Ruhr, and to sabotage the activities of the occupation authorities. Meanwhile, the French and Belgians, starting with 60 thousand troops, increased their presence in the region to 100 thousand people and occupied the entire Ruhr region in 5 days. As a result, Germany lost almost 80% of its coal and 50% of its iron and steel.

Hyperinflation in Germany

While the British were playing their game behind the scenes, the Soviet government was seriously concerned about the current situation. They stated that the escalation of tension in this region could provoke a new European war. The Soviet government blamed both Poincaré's aggressive policies and the provocative actions of the German imperialists for the conflict.

Meanwhile, on January 13, the German government adopted the concept of passive resistance by a majority vote. The payment of reparations was stopped, Ruhr enterprises and departments openly refused to comply with the demands of the occupiers, and general strikes took place in factories, transport and government agencies. Communists and former members of voluntary paramilitary patriotic groups carried out acts of sabotage and attacks on Franco-Belgian troops. Resistance in the region grew, this was even expressed in the language - all words borrowed from French were replaced by German synonyms. Nationalist and revanchist sentiments intensified, fascist-type organizations were secretly formed in all regions of the Weimar Republic, and the Reichswehr was close to them, whose influence in the country gradually grew. They advocated mobilizing forces to restore, train and rearm the “Great German Army.”

Protest against the occupation of the Ruhr, July 1923

In response to this, Poincaré strengthened the occupation army and banned the export of coal from the Ruhr to Germany. He hoped to achieve a status similar to that of the Saar region - when the territory formally belonged to Germany, but all power was in the hands of the French. The repressions of the occupation authorities intensified, a number of coal miners were arrested, and government officials were arrested. In order to intimidate, a show trial and execution of Freikorps member Albert Leo Schlageter, who was accused of espionage and sabotage, was held. The German government repeatedly expressed its protest, but Poincaré invariably replied that “all measures taken by the occupation authorities are completely legal. They are a consequence of the violation of the Treaty of Versailles by the German government."

French soldier in the Ruhr

Germany hoped for help from England, but the British gradually realized that further adding fuel to the fire could be dangerous for themselves. England hoped that due to the occupation the franc would fall and the pound would soar. Only they did not take into account that because of this, the Germans lost their solvency, the devastation in the German economy destabilized the European market, British exports fell, and unemployment began to rise in Britain. In the last hope for help from the British, the German government on May 2 sent them and the governments of other countries a note with proposals for reparations. All issues were proposed to be resolved by an international commission. There was a new round of diplomatic battle. France strongly objected to the accusations of violating the Treaty of Versailles and demanded an end to passive resistance. In June, Chancellor Cuno revised his proposals slightly and put forward the idea of determining Germany's solvency at an "impartial international conference."

Occupation forces

A month later, England expressed its readiness to put pressure on Germany so that it would abandon resistance in the Ruhr, but subject to an assessment of the solvency of the Weimar Republic and the establishment of a more realistic amount of reparations. France again rejected any proposals, the world press started talking about a split in the Entente. Poincaré stated that the ruin of Germany was the work of Germany itself and that the occupation of the Ruhr had nothing to do with it. The Germans must give up resistance without any conditions. It was obvious that both France and Germany wanted a speedy resolution of the conflict, but both sides were too proud to make concessions.

General Charles Dawes

Finally, on September 26, 1923, the new Reich Chancellor Gustav Stresemann announced the end of passive resistance. Under pressure from the United States and England, France signed an allied agreement on a control commission for the factories and mines of the Ruhr. In 1924, a committee led by American Charles Dawes developed a new plan for reparations payments by Germany. The Weimar Republic was able to overcome inflation and gradually began to restore its economy. The victorious powers began to receive their payments and were able to repay the war loans received from the United States. In total, during the Ruhr conflict, the damage to the German economy amounted to 4 to 5 billion gold marks. In July-August 1925, the occupation of the Ruhr region ended.