They say that the war does not end until the last soldier is buried. The Afghan conflict ended a quarter of a century ago, but we do not even know the fate of those Soviet soldiers who remained captured by the Mujahideen after the withdrawal of troops. The data varies. Of the 417 missing, 130 were released before the collapse of the USSR, more than a hundred died, eight people were recruited by the enemy, 21 became “defectors.” These are the official statistics. In 1992, the United States provided Russia with information about another 163 Russian citizens who disappeared in Afghanistan. The fate of dozens of soldiers is unknown. This means that Afghanistan remains our hot spot.

Those who somehow managed to win freedom remained in their internal captivity and could not forget the horrors of that war. On the pages of our book, six former Soviet soldiers tell their amazing stories about life in captivity and after, in the world. All of them lived in Afghanistan for a long time, converted to Islam, started families, speak and think in Dari - an eastern version of the Persian language, one of the two official languages of Afghanistan. Some managed to fight on the side of the Mujahideen. Someone has performed the Hajj. Three of them returned to their homeland, but sometimes they are drawn back to the country that gave them a second life.

This book is about how two incompatible cultures collide in the fate of one person, which one wins, and what ultimately remains of the person himself. Currently, the author of the book, photographer Alexey Nikolaev, is raising funds for its publication. If you liked the project, the author will be grateful for your support.

Arriving in Chagcharan early in the morning, I went to Sergei’s work. It was only possible to get there on a cargo scooter - it was quite a trip. Sergey works as a foreman, he has 10 people under his command, they extract crushed stone for road construction. He also works part-time as an electrician at a local hydroelectric power station.

He received me warily, which is natural - I was the first Russian journalist who met him during his entire life in Afghanistan. We talked, drank tea and agreed to meet in the evening for a trip to his home.

But my plans were disrupted by the police, who surrounded me with security and care, which consisted of a categorical reluctance to let me out of the city to Sergei in the village.

As a result, several hours of negotiations, three or four liters of tea, and they agreed to take me to him, but on the condition that we would not spend the night there.

After this meeting, we saw each other many times in the city, but I never visited him at home - it was dangerous to leave the city. Sergei said that everyone now knows that there is a journalist here, and that I could get hurt.

At first glance, I got the impression of Sergei as a strong, calm and self-confident person. He talked a lot about his family, about how he wanted to move from the village to the city. As far as I know, he is building a house in the city.

When I think about his future fate, I am calm for him. Afghanistan became a real home for him.

- I was born in the Trans-Urals, in Kurgan. I still remember my home address: Bazhova Street, building 43. I ended up in Afghanistan, and at the end of my service, when I was 20 years old, I went to join the dushmans. He left because he did not get along with his colleagues. They all united there, I was completely alone - they insulted me, I could not answer. Although this is not even hazing, because all these guys were from the same draft with me. In general, I didn’t want to run away, I wanted those who mocked me to be punished. But the commanders didn’t care.

“I didn’t even have a weapon, otherwise I would have killed them right away.” But the spirits who were close to our unit accepted me. True, not right away - for about 20 days I was locked in some small room, but it was not a prison, there were guards at the door. They put shackles on at night and took them off during the day - even if you find yourself in the gorge, you still won’t understand where to go next. Then the Mujahideen commander arrived, who said that since I came myself, I could leave on my own, and I didn’t need shackles or guards. Although I would hardly have returned to the unit anyway - I think they would have shot me right away. Most likely, their commander tested me this way.

- For the first three or four months I didn’t speak Afghan, but then gradually we began to understand each other. Mullahs constantly visited the Mujahideen, we began to communicate, and I realized that in fact there is one God and one religion, it’s just that Jesus and Muhammad are messengers of different faiths. I didn’t do anything with the Mujahideen, sometimes I helped with the repair of machine guns. Then I was assigned to a commander who fought with other tribes, but he was soon killed. I didn’t fight against Soviet soldiers - I just cleaned weapons, especially since the troops were withdrawn from the area where I was quite quickly. The Mujahideen realized that if they married me, then I would stay with them. And so it happened. I got married a year later, after that the supervision was completely removed from me, before I was not allowed anywhere alone. But I still didn’t do anything, I had to survive - I suffered from several deadly diseases, I don’t even know which ones.

- I have six children, there were more, but many died. They are all blond, almost Slavic. However, the wife is the same. I earn twelve hundred dollars a month, they don’t pay fools here that kind of money. I want to buy a plot in the town. The governor and my boss promised to help me, I’m standing in line. The state price is small - a thousand dollars, but then you can sell it for six thousand. It’s beneficial if I still want to leave. As they say in Russia now: this is business.

MOSCOW, May 15 - RIA Novosti, Anastasia Gnedinskaya. Thirty years ago, on May 15, 1988, the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan began. Exactly nine months later, the last Soviet military man, Lieutenant General Boris Gromov, crossed the border of the two countries along the Friendship Bridge. But our soldiers remained on the territory of Afghanistan - those who were captured, were able to survive there, converted to Islam and started a family. These are called defectors. Now they, once Seryozha and Sasha, wear unpronounceable Afghan names, long beards and loose trousers. Some, decades later, decided to return to Russia, while others still live in the country of which they became prisoners.

"I dyed my hair to pass as an Afghan..."

Nikolay Bystrov works as a loader at a warehouse in Ust-Labinsk, Krasnodar Territory. Only a few of his colleagues know that twenty years ago he had a different name - Islamuddin - and a different life. “I want to forget this Afghan story,” Nikolai takes a long pause, in the speaker of the phone you can hear him taking a drag from a cigarette. “But they won’t let me...”

He was drafted into the army in 1984 and sent to guard Bagram airport. Six months later, he was captured by the dushmans. He says it happened out of stupidity. “The “old men” sent me and two other boys, Ukrainians, to buy tea and cigarettes at a local store. On the way we were ambushed. They shot me in the leg - I couldn’t escape anywhere. Those two Ukrainians were taken by another group. And I was taken by fighters from detachment of Ahmad Shah Massoud."

Bystrov was put in a barn, where he spent six months. Nikolai claims that during this time he tried to escape twice. But you can’t go far with a hole in your leg: “They caught me when I didn’t even have time to get a hundred meters from the base, and they brought me back.”

Nikolai still doesn’t understand why he wasn’t shot. Most likely, the militants planned to exchange him for one of the captured Afghans. Six months later they began to let him out of the barn without an escort. After some time, they suggested returning to their own people or going to the West through Pakistan. “But I said that I wanted to stay with Masud. Why? It’s difficult to explain. Anyone who has not been in such a situation will still not understand. I was afraid to return to my own people, I didn’t want to be considered a traitor, I was afraid of the tribunal. By that time, he had already lived with the Afghans for a year and converted to Islam,” he recalls.

Nikolai remained with the dushmans and after some time became one of the personal guards of Ahmad Shah Massoud, the field commander who was the first to agree to a truce with the Soviet troops.

How Bystrov, a foreigner, was allowed so close to the most famous commander, one can only guess. He himself talks about this extremely evasively. He says that the “Panjshir lion” (as Masud was called) liked his dexterity and ability to notice little things that in the mountains could cost a person his life. “I remember the first time he gave me a machine gun with full ammunition. We were climbing the pass then. I climbed up before everyone else, stood and thought: “But now I can shoot Masud.” But this would be wrong, because when... then he saved my life,” admits the former captive.

From those constant treks through the mountains, Nikolai retained his love for green tea - during rest stops, Masud always drank several cups, without sugar. “I kept wondering why they drink unsweetened tea. Masud replied that sugar hurts my knees after long marches. But I still secretly added it to the cup. Well, I couldn’t drink this bitterness,” says Bystrov.

Islamuddin did not forget Russian food either - lying at night in the Afghan mountains, he remembered the taste of herring and black bread with lard. “When the war ended, my sister came to see me in Mazar-i-Sharif. She brought all sorts of pickles, including lard. So I hid it from the Afghans so that no one would see that I was eating haram,” he shares.

Nikolai learned the Dari language in six months, although at school, he admits, he was a poor student. After several years of living in Afghanistan, he was almost indistinguishable from the locals. He spoke without an accent, the sun drying his skin. To further blend in with the Afghan population, he dyed his hair black: “Many locals didn’t like the fact that I, a foreigner, was so close to Massoud. They even once tried to poison him, but I prevented the attempt.”

“My mother didn’t wait for me, she died...”

Masud also married Nikolai. Once, the former captive says, the field commander asked him if he wanted to continue walking in the mountains with him or if he dreamed of starting a family. Islamuddin honestly admitted that he wants to get married. “Then he married me to his distant relative, an Afghan woman who fought on the side of the government,” recalls Nikolai. “My wife is beautiful. When I saw her for the first time, I didn’t even believe that she would soon be mine. In the villages I see women with uncovered "I couldn't see it with my head, but she had long hair, she was wearing shoulder straps. After all, she then held the position of state security officer."

Almost immediately after the wedding, Odylya became pregnant. But the child was not destined to be born. In the sixth month, Nikolai’s wife was bombed and had a miscarriage. “She became very ill after that, and there was no normal medicine in Afghanistan. That’s when I first thought about moving to Russia,” Bystrov confesses.

It was 1995 when Nikolai-Islamuddin returned to his native Krasnodar region. His mother did not live to see this day, although she was the only one among her relatives who believed that her Kolya did not die in a foreign land. “She even took my photo to some fortune teller. She confirmed that my son was not killed. Since then, everyone looked at my mother as if she was crazy, and she was still waiting for a letter from me. I was able to send her the first only a year later,” says He.

Odylya came to Russia pregnant. Soon they had a daughter, who was named Katya. “It was my wife who wanted to name the girl that way in memory of my late mother. Because of this, all her Afghan friends turned away from her. They could not understand why she gave the girl a Russian name. The wife answered: “I live on this land and must respect local traditions,” Bystrov is proud.

In addition to their daughter, Nikolai and Odylya are raising two sons. The eldest is called Akbar, the youngest is Ahmad. “My wife named the boys in honor of her communist brothers who died at the hands of dushmans,” the interlocutor clarifies.

This year, the Bystrovs' eldest son should be drafted into the army. Nikolai really hopes that the guy will serve in the special forces: “He leads a strong, healthy lifestyle.”

Over the years, Odyl has been to her homeland only once - not so long ago she went to bury her mother. When she returned, she said that she would never set foot there again. But Bystrov himself traveled to Afghanistan quite often. On instructions from the Committee for Internationalist Soldiers, he searched for the remains of missing Soviet soldiers. He managed to take home several former prisoners. But they never became part of the country that once sent them to war.

Did Bystrov fight against Soviet soldiers? This question hangs in the air. Nikolai lights up again. “No, I have never been in battle. I was with Masud all the time, and he himself did not go into battle. I know, not many will understand me. But those who judge, were they in captivity? They could have done it after two unsuccessful trying to escape a third time? I want to forget Afghanistan. I want to, but they won’t let me..." the former captive repeats again.

"Twenty days later the shackles were removed from me"

In addition to Bystrov, today we know about six more Soviet soldiers who were captured and were able to assimilate in Afghanistan. Two of them later returned to Russia; for four, Afghanistan became a second home.

In 2013, photojournalist Alexey Nikolaev visited all the defectors. From a business trip to Afghanistan, he brought hundreds of photographs that should form the basis of the book “Forever in Captivity.”

The photographer admits: of all the four Soviet soldiers who remained to live in Afghanistan, he was most touched by the story of Sergei Krasnoperov. “It seemed to me that he was not being disingenuous when talking about the past. And unlike the other two prisoners, he was not trying to make money from our interview,” explains Nikolaev.

Krasnoperov lives in a small village fifty kilometers from the city of Chagcharan. He is originally from Kurgan. He assures that he left the unit to escape the bullying of his commanders. It seems that he expected to return in two days - after his offenders were put in the guardhouse. But on the way he was captured by dushmans. By the way, there is another version of Krasnoperov’s escape. There was information in the media that he allegedly fled to the militants after he was caught selling army property.

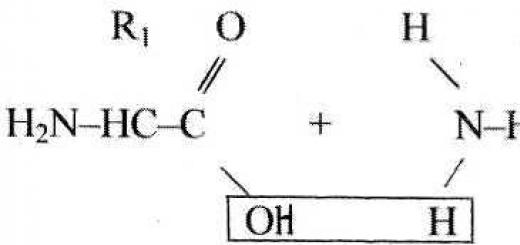

From an interview with Sergei Krasnoperov for the book “Forever in Captivity”:

“For twenty days I was locked in some small room, but it was not a prison. At night they put shackles on me, and during the day they were taken off. The dushmans were not afraid that I would escape. In the mountains you still won’t understand where to go ". Then the commander of the militants arrived and said that since I came to them myself, I could leave on my own. They took off my shackles. Although I would hardly have returned to the unit anyway - I think they would have shot me right away. Most likely, their commander tested me like that..."

After a year of captivity, Krasnoperov was offered to marry a local girl. And he didn’t refuse.

“After that, supervision was finally removed from me. But I still didn’t work. It was very difficult, I had to survive. I suffered from several deadly diseases, I don’t even know their names...”

Photojournalist Alexey Nikolaev says that in 2013 Krasnoperov had six children. “They were all fair-haired, blue-eyed, it was very unusual to see them in an Afghan village,” the photographer recalls. “By local standards, Nurmamad (that’s the name Sergei bears in Afghanistan) is a wealthy man. He worked two jobs: as a foreman at a small placer mining gravel and "I worked as an electrician at a local hydroelectric power station. Krasnoperov received, in his words, $1,200 a month. However, it is strange that at the same time he lived in a mud hut."

Krasnoperov, like all captured soldiers, assures that he did not fight against the Soviet troops, but only helped the dushmans repair their weapons. However, a number of indirect signs indicate the opposite. “He enjoys authority among the locals, which, it seems to me, may indicate that Sergei did participate in the hostilities,” the photojournalist shares his thoughts.

Although Krasnoperov speaks Russian well, he does not want to return to Russia. “As he explained to me, he had no relatives left in Kurgan, everyone died. And in Chagcharan he is a respected person, he has a job. But what awaits him in Russia is unclear,” Nikolaev reports the words of the former captive.

Although Afghanistan is definitely not a place where you can lead a carefree life. Alexey Nikolaev says that during the month of his business trip he found himself in very delicate situations three times. In one of the cases, it was Krasnoperov who saved him. “Out of our stupidity, we decided to record an interview with him not in the city, where it is relatively safe, but in his village. We arrived there without warning. The next morning Sergei called us and told us not to leave the city again. They say there are rumors that we could be kidnapped,” the photographer describes.

From an interview with Alexander Levents for the book “Forever in Captivity”:

"We were going to go to the airport, but almost immediately we ended up with dushmans. By the morning we were brought to some big commander, I remained with him. I immediately converted to Islam, received the name Ahmad, because I used to be Sasha. I was sent to prison They didn’t put me in prison: I was under arrest for only one night. At first I drank heavily, then I became a driver for the militants. I didn’t fight with our people, and no one demanded this of me.<…>After the Taliban left, I was able to call home to Ukraine. My cousin answered the phone and said that my brother and mother had died. I didn't call there again."

From an interview with Gennady Tsevma for the book “Forever in Captivity”:

“When the Taliban came again, I followed all their orders - I wore a turban, let my beard grow long. When the Taliban left, we became free - there was light, TV, electricity. Apart from round-the-clock prayers, nothing good came from them. As soon as I said the prayer, I left from the mosque, they send you back to pray.<…>Last year I went to Ukraine, my father and mother had already died, I went to their cemetery, and saw other relatives. Of course, I didn’t even think about staying - I have a family here. And no one else in my homeland needs me."

In fact, when he says this, Tsevma is most likely being disingenuous. Nikolai Bystrov, the first hero of our material, tried to take him out of Afghanistan. “They called me from the Ukrainian government and asked me to pull their fellow countryman out of Afghanistan. I went. It seems that Gena said that he wanted to go home. They gave him a passport, gave him about two thousand dollars to settle all the formalities, and checked him into a hotel in Kabul. Before the flight, we came to pick him up from the hotel, and he ran away,” Nikolai Bystrov recalls the story of his “return.”

The story of soldier Yuri Stepanov stands out from this series. He was able to settle in Russia only on his second attempt. In 1994, Stepanov tried to return home to the Bashkir village of Priyutovo for the first time. But he couldn’t get comfortable here and went back to Afghanistan. And in 2006 he came to Russia again. He says it's forever. Now he works on a rotational basis in the north. Just the other day he went on shift, so we were unable to contact him.

>

> appears on the lists.

>

> The last expedition from Afghanistan has just returned. She returned, bringing the remains of three more Russian guys who died while performing international duty in Afghanistan. Until now, these guys were listed as missing. And there are still 270 such people left.

>

>

>

quoted1 > > When you hear the word expedition, you think of a serious rescue squad with powerful equipment. Or - a hike of young explorers in the style of Boy Scouts. But neither one nor the other is possible in the conditions of present-day Afghanistan, where the Taliban have already surrounded Kabul. An expedition is two people. Employees of the organization with the long name Committee for the Affairs of Internationalist Soldiers under the Council of Heads of State of the CIS Member States Alexander Lavrentyev and Nikolai Bystrov. Lavrentiev says little about himself, which indicates his obvious involvement in foreign intelligence services. And Bystrov + Called up from the Krasnodar region in 82 and sent to serve in Afghanistan, soon captured, spent 12 years there, became the personal guard of the field commander Ahmad Shah Massoud, and then a relative of the minister of the Afghan government, Nikolai Bystrov is the main guide to Afghanistan.

> >

>

> For a colonel - "Volga", for a private - a ram.

>

quoted1 > > 20 years ago, on the border of the USSR and Afghanistan, Army Commander Boris Gromov said, “There is not a single Soviet soldier behind me.” It sounded impressive, and this point of view expressed the official position of the USSR. At that time, up to 400 USSR citizens could remain in Afghanistan. But international organizations that turned to USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev with a proposal for help in their release received the answer: “Our state is not at war with anyone, so we have no prisoners of war!”

quoted1 > > However, they did not forget about the missing. On the contrary, Yuri Andropov, the head of the KGB of the USSR and subsequently the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee under the KGB, created an OO - a special department that was engaged in searching for them and returning them to their homeland. But amazing political passions always raged around the Afghan captives; they became either heroes or traitors, or a way of pressure or encouragement.

quoted1 > > It is believed that the first prisoners - missing - from a limited contingent appeared in 81. Then, in January, four military advisers did not return from the Afghan regiment that rebelled. What is noteworthy is that in those days the disappearance of even a conscript soldier was regarded as an emergency and a real military operation began to search for him. And during the battle, our troops did not leave the bodies of the dead on the Afghan mountains - they were carried out, or when they retreated to the position, a landing party was later sent with one task - to carry out the bodies. However, the “missing” column was replenished.

quoted1 > > In 1982, the USSR asked the International Red Cross for assistance in returning prisoners of war in Afghanistan. In the conditions of the Cold War, given the position of the USSR that it was not waging the Afghan war, those rescued by the Red Cross were used as spit in the USSR. The conditions of their return were more than strange - the soldiers taken away from the dushmans were kept in complete isolation for two years in Switzerland, in the Zugeberg camp, where they paid 250 francs for work in a subsidiary farm and actively promoted Western values. 11 people passed through Zugeberg, and only three decided to return to the USSR, the rest “chose freedom.” It is clear that the Soviet Union refused help from the Red Cross.

quoted1 > > OO (Special Department) of the KGB in the 40th Army, which is engaged in summoning our soldiers from captivity, rescued about a hundred of our soldiers during the war. Including the Vice-President of Russia, and then the Deputy Commander of the Air Force of the 40th Army, Alexander Rutsky. According to the official version, Rutskoi’s plane was shot down near the border with Pakistan, on Afghan territory. Allegedly, at an altitude of 7 kilometers he was caught by an F-18 of the Pakistani Air Force and shot down by a Sadvinder. Rutskoi ejected and, using scraps of a map, discovered that he was 20 kilometers from Afghanistan, in Pakistan. As one of the KGB OO workers, Gennady Vetoshkin, says, in fact, Rutskoi’s unit flew to Pakistan to bomb a training camp for dushmans. But Pakistan pretended that there were no such camps, and ours pretended that they had not crossed the border. Rutskoi might not have gone on that flight; he had just returned from a combat mission, received an appointment as deputy commander, and he was tormented by bad premonitions,” says Vetoshkin. But he flew. Rutskoi spent a week in captivity and was transferred to the Soviet embassy in Pakistan. Why did he later say that he was terribly tortured and hung on a rack? The NGO employees do not really understand. Alexander Rutskoy received the Hero of the Soviet Union. And for his release they paid a huge sum for those times; with this money one could buy a Volga car.

>

> > But a simple fighter from Belarus, Alexander Yanovsky, has a more tragic story..

> Sasha Yanovsky, drafted from Belarus, was captured just like many others - by accident. I went to get water and got hit on the head. Vetoshkin’s brigade received the first information about Yanovsky from the Islamic Society of Afghanistan party, which was headed by Rabbani. The Afghan police got involved and bargaining began. For Yanovsky, the spirits asked 60 rebels + They bargained that they would give us Sasha, and we would give them Sadar-agu, the leader of a local gang, sentenced to death and imprisoned in the central prison of Kabul Puli-Charkhi. The bargaining was helped by the information that Sasha was captured by his brother Sadar - aga, Shah - aha. But the first attempt at an exchange, which was supposed to take place on the Afghan-Pakistan border, failed. Vetoshkin’s group waited at the appointed place for six hours until a messenger appeared with a note that the deal was being postponed to a later date, and the spirits demanded to add another noble relative to Sadar-Aga.

> Vetoshkin recalls that when Yanovsky was handed over. for a long time he did not understand anything. He shook his head and looked around wildly. Later he said that he decided that the spirits were leading him to test him with blood - there was such a custom. Give a prisoner a weapon and if he shoots at our people, he becomes one of his own. And Yanovsky, according to Vetoshkin, behaved heroically in captivity. Didn't say anything.

> However, it was already the 87th year, our people were preparing to leave Afghanistan, and the spirits did not kill the prisoners immediately, using the most sophisticated methods. From stoning to use in the game "buzaksh". This is something like polo, where riders take the body of a sheep from each other. In the camps, captives were used instead of sheep, the bodies were torn into pieces and fed to dogs. The only chance to stay alive is to convert to Islam. Convinced that at best a prison awaited them in their homeland, they did not return.

> At the end of 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted the Resolution “On the amnesty of former soldiers of the Soviet contingent in Afghanistan who committed a crime.” That is, everyone was freed from any responsibility before the law. And finally the first “returnees” appeared. At first, they were literally “torn out” from under the machine guns of the dushmans, who made sure that the prisoners refused to return. And then+ Then the prisoners began to be returned several times.

>

>Victims of hot friendship.

>

> Big politics demanded immediate results. As retired foreign intelligence colonel Leonid Biryukov recalls, it came to the point of “theft” of prisoners by liberation organizations. Biryukov, having retired, was engaged in the search for prisoners as a deputy. Chairman of the Committee of Soldiers-Internationalists. Having pulled out two people, in Kabul he waited with them for a flight to Moscow. These two were kidnapped by Pakistani intelligence and Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto handed them over to the Russian Federation. With great pomp, under television cameras and lush speeches, Bhutto even gave each captive three thousand dollars. Here, however, there was an embarrassment - having returned to their homeland in the 90s, these people were unable to settle down and soon returned to Afghanistan again. Moreover, illegally, secretly crossing the border. The Committee had already taken them out for the second time, arranging their fate in Russia.

> Alexander Rutskoy also messed up with the prisoner. Having arrived in Afghanistan, he really wanted to return with the liberated man. Well, the Pakistanis gave him a man. And on the plane, Rutsky’s advisers discovered that he did not speak any of the languages of the peoples of the former USSR. He turned out to be a former soldier of the Afghan army. Well, in general, dozens of organizations, political and humanitarian figures, commissions and committees were circling around the prisoners - making a name for themselves. With all their fuss, it must be admitted that they managed to get out of Afghanistan not only those who wanted it, but also those who were hesitant. But then the results became less and less, and a period of reckless friendship passed in politics. And since 2000, only the Committee for the Affairs of Internationalist Soldiers continues the search. Not so much prisoners, but the remains of the dead and the establishment of their identities. Thus, with the help of various sources of information, it was possible to establish the names of almost all those who died during the uprising in the Bada Beri camp. This was the largest camp where the Khaled-ibn-Walid training regiment for training dushmans was based. 12 Soviet soldiers were also held here, used for hard work and brutally beaten.

> On March 26, 1985, having removed the sentries, Soviet prisoners, together with captured soldiers of the Afghan (friendly) army, took possession of the arsenal. The further success of the operation, according to current data, was prevented by a traitor known as Muhammad Islam. The camp was razed to the ground - Pakistan was not at all comfortable with admitting the presence of a dushman camp on its territory. Along with our prisoners, 120 Mujahideen, 6 foreign advisers, and 13 representatives of the Pakistani authorities were killed. From traitors and deserters, these guys turned into heroes.

> However, from the point of view of the law, in accordance with the amnesty of the Supreme Council, there are no traitors in the Afghan war. Even before the amnesty, the authorities were loyal to those who went to the mountains. Their parents and relatives did not know about the contents of secret search cases and received pensions on an equal basis with others.

> It’s a shock for parents to find out that their son is alive, but doesn’t want to come back. And not from any Western country, but from Afghanistan. Today we know for sure about four such people. And, realizing that the parents might not believe it, they were taken to meet their children. The former head of the search department of the Committee for Internationalist Soldiers, Leonid Biryukov, organized such trips in different countries. A mother lived with her son in the United Arab Emirates for a week. He didn't return. Whether there is blood on it, or life there was good - the Committee does not delve into it. We found it, organized a meeting, decided to go, we’ll take it out, no, even after persuasion, it’s his right.

>

> Personal guard of Ahmad Shah.

>

> Nikolai Bystrov is the main conductor of search expeditions in Afghanistan. His Russian speech is strange, a mixture of southern Kuban dialect with a clearly Arabic accent. When asked when he got married, he answers “in 1371+.” And, after a pause, “that’s in 94 in our opinion.” What’s his wife’s name? Laughs in embarrassment. He says that whoever asked in Afghanistan would immediately punch him in the face, he can’t say his wife’s name. Our name is Olya +" In general, as they say in the Committee, Bystrov is stuck between this life and this life.

> Bystrov was captured in 82, after six months of service. Their three young fighters were sent by their “grandfathers” to the village to buy drugs. There is a short-lived battle, two bullet wounds and a shrapnel wound, captivity. Many years later, Bystrov says, he talked with the field commander who captured him. The spirits were lying in ambush on a tip from informants from the Afghan army, who reported that “Shuravi” would enter the village. And then they tied him up and took him from village to village at night for a couple of weeks, beat him severely, then somewhere in the mountains they gave him at least a chance to wash himself. He came out, says Kolya, and there were people standing there. Well, I approached the cleanest one and extended my hand to say hello. He laughed and shook hands. But the security attacked anyway. This is how Kolya met the Pandshir lion, the field commander Ahmad Shah Masud.

> There were 5 more Russians in the mountain camp. One day, Masud announced that everyone can choose their destiny - any country for residence, from the USA to India and Pakistan, or stay with him. Everyone decided to go to the West. Bystrov stayed with Masud.

> Then our offensive began, Masud began to leave the mountain village. He, four guards and Bystrov. Masud gave Bystrov a machine gun and a Chinese-made Kalashnikov. "We walked through the snow, I was the first to climb the pass. I see our missiles, the sound of battle. Below - Masud with nukers. I thought they were checking. I checked the machine gun - the firing pin was not cut off. The horn with cartridges was full. There was an idea to cut everyone off with a burst + But + Didn't cut it"

> Bytrov spent 12 years in Afghanistan. He didn’t fight against his own people, but he defended Masuda honestly in the conditions of the Afghan civil strife. And Ahmad Shah appreciated him, occasionally changing all his personal guards, and always kept Bystrov with him. And when he became a member of the Government of Afghanistan, after the departure of Soviet troops. But when the Taliban began to approach Kabul, I again faced a choice - “either die in a battle with the Taliban, or get married.” Bystrov's wife, although distant, is a relative of Ahmad Shah. They had two children in Afghanistan, but they did not survive. And again, Masud, according to Bystrov, forced him and his wife to go to Russia.

> Bystrov arrived + No work, nowhere to live.. I wanted to go to Afghanistan again. The Afghani wife refused. Their children, born in Russia, survived. The eldest is now 14, the youngest is 6. The middle one is 12, he is an excellent student at school. The wife works as a cleaner, and Bystrov is looking for the living and the remains of the dead.

> -It’s difficult, people are afraid that the Taliban will come to power again. Even through three intermediaries you get in touch with someone who remembers where the Russian’s body was buried, but they don’t risk taking him there. And yet the remains of three more were brought. I know where a few more are buried, I know how to find them+.

>

>

> The war continues.

>

>

> “We almost certainly know whose remains were brought, but I wouldn’t want to say the names until a DNA examination is carried out,” says the current head of the search team, who replaced Leond Biryukav, Alexander Lavrentiev. This week I will go to the Lipetsk region myself to take DNA samples from alleged relatives. Oh, there are such difficulties here, the laboratory is imperfect, they can only give results in the male line+ But at least this+

>

> The work on the release of Afghan captives and the search for remains fluctuated along with the ups and downs of big politics. FROM a committee under the Presidents of Russia and the USA, with appropriate powers and money - to self-financing. Like, look for sponsorship money. But the remains found were impossible to identify. The Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation stubbornly replied that money for DNA examination was provided only for those killed in the North Caucasus. And the remains were kept almost piled up until the Minister of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Tatarstan offered his laboratory. Although not free, it is at a reasonable price. And it was this year, in Astana, that the Council of Heads of Government of the Commonwealth of Independent States decided to continue the search for missing people, their burial places, identification and reburial of them in their homeland. All heads of state of the CIS signed it, but real money went only under the signature of Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. The rest agree to look, but there is no money yet. However, of the 270 missing people, the majority are Russians - 136.

>

>

> Russian Generalissimo Alexander Suvorov said that the war does not end until the last soldier who died in it is buried. There is nothing to add to this, just keep reminding

According to official data, during the Afghan war of 1979-1989, about 330 Soviet military personnel were captured. Of these, about 150 people survived. Although in reality there were most likely more captured. What fate awaited those who had the misfortune of finding themselves at the mercy of the Mujahideen?

Afghan martyrs

Some prisoners of war were lucky. Some agreed to convert to Islam and even fight against their own - and remained alive, received new names, started families, even made a military career... Others were exchanged or handed over to Western human rights organizations. But most ended up in hell, from where it was almost impossible to get out alive.

The traditions of radical Islam call for the martyrdom of infidels - this is a kind of guarantee of “going to heaven.” In addition, fanaticism was supposed to serve as a means of intimidating the enemy - it was not for nothing that the mutilated remains of prisoners were often thrown to Soviet garrisons.

“On the morning of the second day after the invasion of Afghanistan, a Soviet sentry spotted five jute bags on the edge of the runway at Bagram Air Base outside Kabul,” writes American journalist George Crile in his book “Charlie Wilson’s War.” “At first he didn’t attach much importance to it, but then he poked the barrel of the machine gun into the nearest bag and saw blood coming out. Bomb experts were called in to check the bags for booby traps. But they discovered something much more terrible. Each bag contained a young Soviet soldier, wrapped in his own skin.”

These captured soldiers were subjected to a brutal execution called the "red tulip". First, they were injected with a large dose of the drug, then they were hung up by their arms, the skin was cut around the entire body and rolled up. When the effect of the drug wore off, the condemned person experienced severe pain shock. As a rule, people first lost their minds and then died a slow death...

“One group of prisoners, who were flayed, were hanged on hooks in a butcher's shop. Another prisoner became the central toy of an attraction called “buzkashi” - a cruel and savage polo of Afghans galloping on horses, snatching a headless sheep from each other instead of a ball. They used a prisoner instead. Alive! And he was literally torn to pieces.”

Life in the Underworld

If the prisoners were not going to be killed, they were usually kept in underground “casemates.” Here is the story of one of them, a native of the Khmelnitsky region Dmitry Buvaylo, released in December 1987:

“They kept me in shackles in a hidden hole-cave for several days. In the prison near Peshawar, where I was imprisoned, the food was made from nothing but waste... In prison, for 8-10 hours every day, the guards forced me to learn Farsi, memorize suras from the Koran, and pray. For any disobedience, for mistakes in reading surahs, they were beaten with lead clubs until they bled.”

In Pakistan's Mobarez camp, prisoners were kept in a cave where there was no light or fresh air. They were tortured and abused every day. Many could not stand it and committed suicide.

Death or betrayal?

Probably the most famous of the Soviet prisoners of war in Afghanistan can be called Major General of Aviation, Hero of the Soviet Union Alexander Rutsky, former vice-president of the Russian Federation. In April 1988, he was appointed deputy commander of the air force of the 40th Army and sent to Afghanistan. Despite his high position, Rutskoy himself took part in combat missions. On August 4, 1988, his plane was shot down. Alexander Vladimirovich ejected and five days later was captured by the dushmans of Gulbidin Hekmatyar. They beat him, hung him on a rack... Then they handed him over to Pakistani special forces. It turned out that the CIA was interested in the downed pilot. They tried to recruit him, force him to reveal the details of the operation to withdraw Soviet troops from Afghanistan, offered new documents and various benefits in the West... Fortunately, information that he was in Pakistani captivity reached Moscow, and in the end, after difficult negotiations , Rutskoi was released.

For many Soviet prisoners of war, the only alternative to martyrdom was betrayal of the Motherland, agreement to cooperate with the Mujahideen or Western intelligence services. But not everyone chose life in exchange for conscience...

ALL PHOTOS

Sixteen years after the last Soviet tanks left Afghanistan, the ghosts of a decade of Soviet occupation still linger in the mountains of the country's north. They lead the same lives as the locals, but they are distinguished by their pale skin color, and when they get together, they speak Russian among themselves.

These people are the last surviving Soviet soldiers who were captured or deserted, converted to Islam and fought on the side of the Mujahideen against their former comrades, writes the British newspaper The Daily Telegraph. (Translation from the website Inopressa.ru.) The invasion of Afghanistan led to the death of about 15 thousand Soviet soldiers and specialists between 1979 and 1989. 1.3 million Afghans died, mostly civilians.

In July 1988, the Russian government offered amnesty to Russian prisoners of war and deserters in Afghanistan. Not many converts to Islam took advantage of this offer, although all of them were able to visit Russia after the end of the war with the help of visas obtained in Pakistan.

Nasratullah Mohamadullah, formerly Nikolai Vyrodov, was born in 1960 in Kharkov, Ukraine. His father Anatoly was also a soldier, and Nikolai studied at the military academy. Nasratullah, 45, now earns £45 a month as a police officer in Baghlan province. A quiet, melancholy man, a heavy smoker, he still fears retribution for his violation of military duty.

He volunteered for service in Afghanistan and served for three months before deserting in 1981 after witnessing the merciless killing of more than 70 people in the village of Kaligai, he said. “In the Soviet army they swore on the sword and the Bible to help the people. What was done there was against the law,” he explained. He converted to Islam and fought against the Soviet Army.

When the USSR withdrew troops from Afghanistan, the subversive specialist worked with various field commanders. Nasratullah then spent eight years on the front line. His fellow Mujahideen say he and the other Russians were worthy fighters and especially useful in intercepting information over Russian radio channels. “If you're on the front line, you have to fight and kill,” is all he says about what it's like to fight against his fellow countrymen.

Vyrodov spent the longest time in the personal security of the country's former Prime Minister Gulbetdin Hekmatyar. When asked if it was true that army intelligence was hunting him, Vyrodov replied that he had to escape from encirclement three times. On the other side of Panj, many people know Vyrodov. The Mujahideen, who never understood why a man with a Russian surname became one of them, call him a loner.

Shortly before leaving for Afghanistan, Nasratullah said: “Either I will return as a Hero of the Soviet Union, or I will not return at all.” He did not return to the Soviet Union; he returned to Russia in 1996, but not for long - he withstood Nasratullah in Kharkov for only six months, and then again went to war in Afghanistan. He said that he himself had to lay mines, but only defensively. “When we were defending and we ran out of ammunition, then we had to lay mines.”

Nasratullah did not like to talk about his exploits. But it was they who allowed him to occupy a high position in Hekmatyar’s retinue - and even earn a lifelong pension.

They searched for Nasratullah for fourteen years, from 1982 to 1996. First military intelligence and the KGB, then father and relatives. It was found by former officers, veterans of the Afghan war.

When Nasratullah was in Ukraine in 1996, he met some of his army comrades there and says he was relieved to see that they did not blame him for apostasy and joining the mujahideen army, the newspaper reported.

“I haven’t heard from him since 1996. I told him: “Kolya, get married, and this will be your home.” But he didn’t listen, he only said that he would return in five years. Although it is very dangerous for him to be with the Taliban.” , - says Nikolai’s stepmother, Ekaterina Kulkova.

According to The Daily Telegraph, under the Taliban government, three Russians came to the attention of Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar, who, impressed by their commitment to Islam, provided them with homes and businesses. But after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, their homes were confiscated, and now none of the three can be considered rich. Where they live, they are looked upon as a curiosity and respected for their piety. All three are married to local women and have families.

In appearance, Alexey Olenin (Rakhmatullah) does not look too much like an Afghan. Chinese jacket, jeans, beard, dark brown hair, blue eyes. No skullcap, no long shirt dress. Densely built, in contrast to the thin and dried out Afghans, like a roach.

In 2004, Alexey firmly decided to return to Russia. I hesitated for a long time, looked closely and finally decided. “There will never be life here,” he said, “because there is no law. Any bandit will come and take whatever he likes.” A gang of unknown thugs took over his house in Puli Khumri. The documents for the house are in order, the court ordered the house to be returned, but the bandits do not obey.

Olenin hoped to sell the house and return to the Samara region with the proceeds. “They give me a one-room apartment, but there is no work there. The only way out is to open my own store. I also have a store here, I know the business. But to start, I need money. I will get 50 thousand dollars for the house, that’s enough.”

Housing prices are high in Afghanistan. In Kabul, a 2-room apartment in a five-story building costs at least 40 thousand dollars. Alexei's house, which is not even a house, but an adobe hut of two rooms, costs 50 thousand.

All the money in Afghanistan comes from selling drugs. People try to be involved in this business - grow, resell, transport, be an intermediary. Olenin did not earn his apartment from drugs: Mullah Omar allocated plots of land to him and several other former prisoners because they converted to Islam.

Alexey does not tell how he got to the Mujahideen and how he became a Muslim.

On May 26, 2005, the former Soviet soldier returned from Afghanistan, where he converted to Islam, to Russia - to his native Samara region. Channel One spoke about Private Olenin.

A few years ago he married a local girl and they had a daughter, Jasmine. Once a film crew from Channel One was working in Puli-Khumri. Journalists helped Olenin meet his relatives. Samara authorities provided the family with a one-room apartment and promised to help with work. Nargiz, Olenin’s wife, is still embarrassed; not long ago she wore a burqa.

Gennady Tsevma from the city of Torez, Donetsk region, has been living in the city of Kunduz in northern Afghanistan for more than 20 years. In Afghani his name is long - Nikmohammat. “The commander called,” explained Tsevma. “He said: you will be Nikmohammat. And that’s all. There was Gena, and there is no more Gena.”

Gena-Nikmohammat has an Afghan wife and three children. He himself is thin and dressed like an Afghan - in a light gray shirt dress. Short bowl haircut, reddish beard, transparent eyes. He also seemed to want to go home, but was afraid, and came to convince him, telling him how he himself recently went to Russia, and nothing bad happened to him.

To begin with, Tsevma was also offered to go alone, without his wife and children, for a couple of months. If he likes it, he will return to Afghanistan, sell his property, take his family and leave forever. A lot of money was allocated for his return - both for travel and for life. They were ready to give him an apartment in Torez, provide him with treatment (he has a severe limp), and help him with work.

According to Tsevma, the Russian Embassy issued him a certificate of return instead of a passport. He has no citizenship. He came to Afghanistan as a citizen of the Soviet Union, but such a state no longer exists. Russia is the legal successor of the USSR, so Russian services provide him with the necessary documents, and then let him decide in which country to live.

He had already been bought a Kabul-Moscow-Kabul ticket with an open date so that he could return to Afghanistan whenever he wanted. Permission to cross the Russian-Ukrainian border was also obtained, for which a lot of work was done by the border service of the FSB and the Russian Foreign Ministry.

Tsevma was given $1,200 on receipt - to pay off his debts and leave it to his wife, so that he would have something to live on until he returned. Gena said he still needs to buy clothes - he won’t fly in an Afghan dress. They also gave him some clothes. Then Gena asked for money for the trip from Kunduz to Kabul under the pretext that there would be a holiday, no one would be lucky, he would have to offer triple the price. They gave him this money too. He wrapped himself in a scarf, vowed to definitely arrive in Kabul at the appointed time, and left, leaning heavily on his right leg.

However, he never arrived. A poor disabled man, whom everyone tried to help out of pity, deceived a lot of people, let down people holding high positions in Russia and Ukraine, and disappeared, embezzling almost two thousand dollars, MK reported in 2004. It later turned out that after the meeting, Gena immediately went to two Ukrainians who had some connection with the Ukrainian special services, who, apparently, tried to make sure that he did not fly to Moscow.

Veterans of the Afghan war are still fighting on the side of the Taliban. 8 thousand Uzbek fighters are fighting in the northern provinces. They are commanded by Juma Namangani, who, according to some sources, remained alive after the report of his death in 2001 and whom the Soviet paratroopers knew under the name Dzhumabai Khodzhiev.

In 1989, he left Afghanistan and returned there again in 1993. Namangani headquarters is near the provincial center of Baghlan on the territory of a former sugar factory. He is considered a master of guerrilla warfare, having fought in the regular forces and then as a guerrilla fighter in the Fergana Valley with the Islamic group Repentance.

Few can resist such people. For example, those who studied Farsi and subversion in Hekmatyar's camps. Or he received excellent marks at special courses in Balashikha - the same former Soviet soldiers who remained to fight after the withdrawal of troops in 1989.

Prisoners of war and missing persons are the inevitable victims of all wars and armed conflicts. The Afghan war was no exception. According to official statistics, during the fighting in Afghanistan, 417 Soviet citizens went missing or were captured. Until 1992, 119 of them were released, says Deputy Chairman of the State Committee of Ukraine for Veterans Affairs Valery Ablazov.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a list was transferred to Ukraine, which included 80 of our compatriots. Over 11 years of work, this list was reduced by ten names. There are only 70 Ukrainians on the list of missing or captured people. Most of them died. However, the fact of their physical death has not been officially established, since the body or remains have not been found, the burial place is unknown, writes Kyiv Vedomosti.

The fate of those captured was different, but an indispensable condition for preserving life was the adoption of Islam. At one time, the tragedy that took place in a prisoner of war camp in the small Pakistani town of Badaber received wide resonance, where on the evening of April 26, 1985, seven Soviet and three Afghan captured soldiers and officers, taking advantage of the slowness of the guards, seized the prison and the warehouses with weapons and weapons located on its territory. ammunition belonging to the militants of Burhanuddin Rabbani.

The prison, which became both a shelter and a trap for the former captives, was quickly surrounded by the Mujahideen. Taking up a perimeter defense, the soldiers repelled attacks all night. And at dawn there was an explosion of such force that fragments, fragments of buildings and the remains of people scattered over a radius of several kilometers.

There is still plenty of mystery in the Afghan war. For example, it is gradually becoming known how experiments were carried out on internationalist soldiers. In 1981, psychophysiologist Yuri Gorgo, now a teacher at Kyiv University, was thrown into the area of action by fate. He then dealt with the problems of assessing and managing a working person. It was the second year of the war. Armored vehicles were used to conduct combat operations and humanitarian operations. The human losses of the initial period were very high.

Local residents eagerly hunted for tanks. For each damaged car they were paid 100 Afghanis or 100 dollars. Burn the tank, cut off the ears of four Russians, bring back a photograph. The Americans provided assistance not only with weapons, but also with money. Our guys were not ready for such tactics.

Yuri Gorgo and his colleagues from Gorky faced two tasks. The first is to find a way to prepare people to ease the emotional state when they find themselves in real combat conditions.

It was based on the theory of low-frequency sound radiation (8 - 10 Hz), which causes a feeling of anxiety and even panic in most people. “We installed headphones into the headsets, through which we supplied background sounds,” says the scientist. “We were supposed to adapt the fighter to an anxious state and force him to act in this state.

Almost everyone who trained in schools near Gorky had such headphones. Three of the five crew members are commander, driver, gunner. The guys had no idea about anything, and this was part of the experimental plan. When they complained of anxiety or headaches, they were told that this was completely normal, that they should do their duty.

The results were amazing. After the trained fighters began to go to the front line, the number of losses immediately decreased sharply, by 40 percent. “We understood this pattern,” continues Yuri Gorgo. “But many generals were puzzled by this phenomenon, since our work was classified. At Kiev University, the economic effect of our implementation was calculated. Taking into account the costs (200 thousand rubles) for the first six months, it amounted to 2.5 million rubles.

The second task was more difficult: during a battle we had to learn how to receive current information about the emotional state of the fighters and influence it. Sensors were installed in the uniform, which recorded heart rhythms telemetrically, that is, at a distance. The data was passed through a radio station, which operated in continuous information transmission mode.

Rhythm-cardioanalyzers built a spectrum of repeat intervals for each person. The parameters were highlighted, and everything could be seen and analyzed. “Against the backdrop of strong words from the commander to the soldiers and vice versa, we cut out four channels through which information was flowing. The crew did not suspect this,” recalls Yuri Gorgo.

Then, at the Exhibition of Economic Achievements of the USSR, this entire complex, in declassified form, received a gold medal with the wording “a complex for assessing the ergonomic characteristics of tracking system operators.” The implementation date was shifted so that no one would have associations with Afghanistan.

It was more difficult to take corrective measures after analyzing the current information. Six states are classified: rest, normal, optimal performance, concentrated work, pre-stress state and stress. In garrisons, soldiers were in a state of optimal performance. When we went out on the road, we were in a state of concentration. And as soon as something incomprehensible appeared, a pre-stress state set in, which could very quickly turn into stress.

It was very difficult to trace the transition from one state to another using repeat intervals. The five conditions could be graphically distinguished, but stress was not distinguished according to these parameters. Later, scientists came up with the idea of identifying it based on skin temperature. In a stressful situation, the skin temperature drops sharply, and then also rises sharply to the initial level.

“When we saw from the instruments that one of the fighters was in a pre-stress state, we immediately took correlation actions. From the command post there was an order to the crew commander to distract the “problem” fighter. We tried to switch them using a loud sound signal coming from the headphones. Panic can be suppressed if you switch to local actions from the very beginning of its occurrence.

Attempts were made to influence with color - green, blue, red light bulbs. During the experiment, it turned out that green is a calming color, purple and blue are anxious, and red is neutral, but optimizing. Functional music could also be provided - soothing or stimulating.

Soldiers who fought against the USSR in the armed Mujahideen detachments in Afghanistan

(as of February 15, 1989, according to the Russian Union of Afghanistan Veterans):

Alloyarov Nanaz Ruzievich - private

Bakirov Soatnurat Parnanovich - private

Bekmuratov Murat Erkinovich - private

Vylku Ivan Evgenievich - private

Vyrodov Nikolai Anatolyevich - private

Kopadze Archil Gennadievich - private

Lopukh Andrey Andreevich - private

Nazarov Viktor Vasilievich - junior sergeant

Olenin Alexey Ivanovich - private

Prokopchuk Valery Konstantinovich - private

Soatov Ilyas Muminovich - private

Stepanov Yuri Fedorovich - private

Tashrifov Kurbanali Hukmatulpaevich - private

Tikhonov Alexey Roltovich - sergeant

Fateev Sergey Vladimirovich - private

Khodimuratov Murnamat Ashurovich - junior sergeant

Vyrodov Nikolai Anatolyevich - private (in the personal guard of Gulbetdin Hekmatyar)

Gulgeldinov Davletnazar - private

Dubina Valentin Nikolaevich - private

Abdulgapurov Magomed Kamil-Magomedovich - private

Abdurashidov Isuf Abdullagaevich - private

Akilbekov Iskander Dzhienbekovich - private

Altyev Kumin Sultanovich - junior sergeant

Albatov Ramazan Shakhimovich - junior sergeant

Baykeev Nail Faridovich - private

Bondarev Sergey Nikolaevich - private

Byk Viktor Konstantinovich - private

Bystrov Nikolai Nikolaevich (Islamuddin) - private (in the personal guard of Ahmad Shah Massoud)

Varvaryan Mikhail Abramovich - private

Vorontsov Sergey Vladimirovich - private

Vorsin Pavel Georgievich - junior sergeant

Grinyk Igor Ilyich - private

Eremenko Nikolai Valentinovich - private

Zverkovich Alexander Anatolyevich - private

Zuev Alexey Alekseevich - private

Karpenko Valentin Petrovich - warrant officer

Kashirov Vladimir Nikolaevich - private

Kochkorov Orazali Toktonazarovich - private

Krasnoperov Sergey Yurievich - private

Krivonosov Alexey Petrovich - lieutenant

Lazarenko Vasily Egorovich - private

Levenets Alexander Yurievich - private

Levchishin Sergey Nikolaevich - private

Malyshev Alexander Sergeevich - private

Maltsev Valery Valentinovich - private

Makhmadnazarov Hazrat Ablakunovich - junior sergeant

Mykolaichuk Nikolai Vladimirovich - private

Mishakov Yuri Vladimirovich - private

Nesterev Sergey Anatolyevich - private

Petrov Nikolai Ivanovich - private

Petikov Evgeniy Viktorovich - private

Pikhach Vasily Vasilievich - private

Roshchupkin Alexey Vasilievich - sergeant

Samin Nikolai Grigorievich - junior sergeant

Sokolov Nikolai Vladimirovich - private

Talashkevich Anatoly Aleksandrovich - private

Fedorov Vasily Eremeevich - private

Khakhalev Vasily Viktorovich - junior sergeant

Khudalov Kazbek Akhtemirovich - senior lieutenant

Tsevna Gennady Anatolyevich - private

Chekhov Viktor Tiranovich - sergeant

Chupakhin Viktor Ivanovich - private

Shvets Viktor Vladimirovich - private

Yazkhanov Beshingeldy - private

Were wanted (as of February 15, 1989) - 334 people, of them:

missing - 316 people

interned in other countries - 18 people

captured by the Mujahideen - 39 people

returned to their homeland - 6 people.

In addition to 13,833 people (from the OKSV), the following died:

USSR KGB employees - 585 people

employees of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs - 28 people

military advisers, specialists and translators - 180 people.