The biography of Nikolai Pirogov, whom his contemporaries dubbed the "wonderful doctor" is a vivid example of selfless service to medical science. A myriad of discoveries that saved the lives of thousands of people are still being used in medicine.

Childhood and youth

The future genius of world medicine was born in a large family of a military official. Nicholas had thirteen brothers and sisters, many of whom died in infancy. Father Ivan Ivanovich was educated and achieved great success in his career. As his wife, he took a kind, complaisant girl from an old merchant family, who became a housewife and the mother of their many children. Parents paid special attention to the upbringing of their children: boys were assigned to study at prestigious institutions, and girls were educated at home.

Among the guests of the hospitable parental home there were many doctors who willingly played with the inquisitive Nikolai and told entertaining stories from practice. Therefore, from an early age, he decided to become either a military man, like his father, or a doctor, like their family doctor Mukhin, with whom the boy became very friendly.

Nikolai grew up as a capable child, learned to read early and spent days sitting in his father's library. From the age of eight, they began to invite teachers to him, and at eleven they sent him to a private boarding school in Moscow.

Soon, financial difficulties began in the family: the eldest son of Ivan Ivanovich, Peter, seriously lost, and his father had a waste in the service, which had to be covered from his own funds. Therefore, the children had to be taken away from prestigious boarding schools and transferred to home schooling.

The family doctor Mukhin, who had long noticed Nikolai's abilities in medicine, contributed to entering the university at the Faculty of Medicine. An exception was made for the gifted youth, and he became a student at the age of fourteen, and not at sixteen, as required by the rules.

Nikolai combined his studies with work in the anatomical theater, where he gained invaluable experience in surgery and finally decided on the choice of his future profession.

Medicine and Pedagogy

After graduating from the university, Pirogov was sent to the city of Dorpat (now Tartu), where he worked at the local university for five years and defended his doctoral dissertation at the age of twenty-two. Pirogov's scientific work was translated into German, and soon they became interested in Germany. The talented doctor was invited to Berlin, where Pirogov worked for two years with leading German surgeons.

Returning to his homeland, the man hoped to get a chair at Moscow University, but another person who had the necessary connections took it. Therefore, Pirogov remained in Dorpat and immediately became famous throughout the district for his fantastic skill. Nikolai Ivanovich easily took on the most complex operations that no one had done before him, describing the details in pictures. Soon Pirogov becomes a professor of surgery and leaves for France to inspect local clinics. The institutions did not impress him, and Nikolai Ivanovich caught the eminent Parisian surgeon Velpo reading his monograph.

Upon his return to Russia, he was offered to head the Department of Surgery at the Medical and Surgical Academy of St. Petersburg, and soon Pirogov opened the first surgical hospital with a thousand beds. The doctor worked in St. Petersburg for 10 years and during this time wrote scientific papers on applied surgery and anatomy. Nikolai Ivanovich invented and supervised the manufacture of the necessary medical instruments, continuously operated in his own hospital and consulted in other clinics, and worked at night in an anatomical clinic, often in unsanitary conditions.

This way of life could not but affect the health of the doctor. The news that the highest order of the sovereign approved the project of the world's first Anatomical Institute, on which Pirogov had been working in recent years, helped to rise to his feet. Soon, the first successful operation was performed using ether anesthesia, which became a breakthrough in the world of medical science, and the anesthesia mask designed by Pirogov is still used in medicine.

In 1847, Nikolai Ivanovich leaves for the Caucasian War in order to test scientific developments in the field. There he performed ten thousand operations using anesthesia, put into practice the bandages invented by him, impregnated with starch, which became the prototype of the modern plaster cast.

In the autumn of 1854, Pirogov, with a group of doctors and nurses, went to the Crimean War, where he became the chief surgeon in Sevastopol, surrounded by the enemy. Thanks to the efforts of the service of nurses he created, a huge number of Russian soldiers and officers were saved. He developed a completely new system for those times for evacuation, transportation and sorting of the wounded in combat conditions, thus laying the foundations of modern military field medicine.

Upon returning to St. Petersburg, Nikolai Ivanovich met with the emperor and shared his thoughts on the problems and shortcomings of the Russian army. was angry with the impudent doctor and did not want to listen to him. Since then, Pirogov fell out of favor at court and was appointed trustee of the Odessa and Kiev districts. He directed his activities to reforming the system of existing school education, which again caused dissatisfaction with the authorities. Pirogov developed a new system that included four stages:

- elementary school (2 years) - mathematics, grammar;

- incomplete secondary school (4 years) - general education program;

- secondary school (3 years) - general education program + languages + applied subjects;

- higher education: institutions of higher education

In 1866, Nikolai Ivanovich moved with his family to his estate Vishnya in the Vinnitsa province, where he opened a free clinic and continued his medical practice. Sick and suffering people came to the "wonderful doctor" from all over Russia.

He did not leave his scientific activity either, having written works on military field surgery in Vishnu, which glorified his name.

Pirogov traveled abroad, where he took part in scientific conferences and seminars, and during one of the trips he was asked to provide medical assistance to Garibaldi himself.

Emperor Alexander II again remembered the famous surgeon during the Russian-Turkish war and asked him to join the military campaign. Pirogov agreed on the condition that they would not interfere with him and restrict his freedom of action. Arriving in Bulgaria, Nikolai Ivanovich set about organizing military hospitals, having traveled 700 seven hundred kilometers in three months and visited twenty settlements. For this, the emperor granted him the Order of the White Eagle and a gold snuff box with diamonds, decorated with a portrait of the autocrat.

The great scientist devoted his last years to medical practice and writing the Diary of an Old Doctor, finishing it just before his death.

Personal life

The first time Pirogov married in 1841 was the granddaughter of General Tatishchev Ekaterina Berezina. Their marriage lasted only four years, the wife died from complications of difficult childbirth, leaving behind two sons.

Eight years later, Nikolai Ivanovich married Baroness Alexandra von Bistrom, a relative of the famous navigator Kruzenshtern. She became a faithful assistant and comrade-in-arms; through her efforts, a surgical clinic was opened in Kyiv.

Death

The cause of Pirogov's death was a malignant tumor that appeared on the oral mucosa. He was examined by the best doctors of the Russian Empire, but could not help. The great surgeon died in the winter of 1881 in Vishnu. Relatives said that at the moment of the dying man's agony, a lunar eclipse happened. The wife of the deceased decided to embalm his body, and, having received permission from the Orthodox Church, she invited Pirogov's student David Vyvodtsev, who had long been involved in this topic.

The body was placed in a special crypt with a window, over which a church was subsequently erected. After the revolution, it was decided to keep the body of the great scientist and carry out work to restore it. These plans were interrupted by the war, and the first reembalming was carried out only in 1945 by specialists from Moscow, Leningrad and Kharkov. Now the same group that maintains the state of bodies , and is engaged in the preservation of Pirogov's body.

Pirogov's estate has survived to the present day; a museum of the great scientist is now organized there. It annually hosts Pirogov readings dedicated to the surgeon's contribution to world medicine, and gathers international medical conferences.

Russian surgeon and anatomist, naturalist and teacher, Privy Councilor

Nikolai Pirogov

short biography

Nikolai Ivanovich Pirogov(November 25, 1810, Moscow, Russian Empire - December 5, 1881, Cherry village (now within the boundaries of Vinnitsa), Podolsk province, Russian Empire) - Russian surgeon and anatomist, naturalist and teacher, professor, creator of the first atlas of topographic anatomy, founder of Russian military field surgery, founder of the Russian school of anesthesia. Privy Councillor.

Nikolai Ivanovich was born in 1810 in Moscow, in the family of a military treasurer, Major Ivan Ivanovich Pirogov (1772-1826). He was the thirteenth child in the family (in accordance with three different documents stored in the former Imperial Derpt University, N. I. Pirogov was born two years earlier - on November 13, 1808). Mother - Elizaveta Ivanovna Novikova, belonged to an old Moscow merchant family.

Nicholas received his primary education at home. In 1822-1824 he studied at a private boarding school, which he had to leave because of the deteriorating financial situation of his father.

In 1823, he entered the medical faculty of the Imperial Moscow University as a student of his own (in the petition he indicated that he was sixteen years old; despite the need for a family, Pirogov's mother refused to give him to state students, "it was considered as if something humiliating"). He listened to the lectures of Kh. I. Loder, M. Ya. Mudrov, E. O. Mukhin, which had a significant impact on the formation of Pirogov's scientific views. In 1828 he graduated from the department of medical (medical) sciences of the university with a doctor's degree and was enrolled in the students of the Professorial Institute, opened at the Imperial Derpt University for the training of future professors of Russian universities. He studied under the guidance of Professor I.F. Moyer, in whose house he met V.A. Zhukovsky, and at Dorpat University he became friends with V.I. Dahl.

In 1833, after defending his dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Medicine, he was sent to study at the University of Berlin together with a group of eleven of his comrades from the Professorial Institute (among them - F. I. Inozemtsev, P. D. Kalmykov, D. L. Kryukov , M. S. Kutorga, V. S. Pecherin, A. M. Filomafitsky, A. I. Chivilev).

After returning to Russia (1836) at the age of twenty-six, he was appointed professor of theoretical and practical surgery at the Imperial Derpt University.

In 1841, Pirogov was invited to St. Petersburg, where he headed the Department of Surgery at the Medico-Surgical Academy. At the same time, Pirogov led the Clinic of Hospital Surgery organized by him. Since Pirogov's duties included the training of military surgeons, he began to study the surgical methods common in those days. Many of them were radically reworked by him. In addition, Pirogov developed a number of completely new techniques, thanks to which he managed to avoid amputation of limbs more often than other surgeons. One of these techniques is still called "Operation Pirogov".

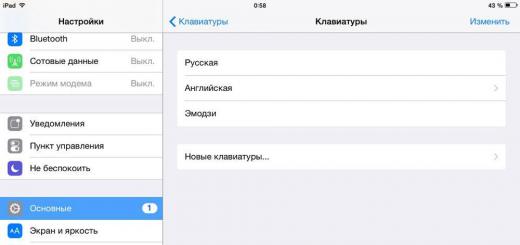

In search of an effective teaching method, Pirogov decided to apply anatomical studies on frozen corpses. Pirogov himself called this "ice anatomy". Thus was born a new medical discipline - topographic anatomy. After several years of such anatomy study, Pirogov published the first anatomical atlas entitled "Topographic anatomy, illustrated by cuts made through the frozen human body in three directions", which became an indispensable guide for surgeons. From that moment on, surgeons were able to operate with minimal trauma to the patient. This atlas and the technique proposed by Pirogov became the basis for the entire subsequent development of operative surgery.

Since 1846 - Corresponding Member of the Imperial St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences (IAN).

In 1847, Pirogov left for the active army in the Caucasus, as he wanted to test the operational methods he had developed in the field. In the Caucasus, he first used dressing with bandages soaked in starch; starch dressing proved to be more convenient and stronger than previously used splints. At the same time, Pirogov, the first in the history of medicine, began to operate on the wounded with ether anesthesia in the field, performing about ten thousand operations under ether anesthesia. In October 1847, he received the rank of real state councilor.

Crimean War (1853-1856)

At the beginning of the Crimean War, on November 6, 1854, Nikolai Pirogov, together with a group of doctors and nurses he led, left St. Petersburg for the theater of operations. Among the doctors were E. V. Kade, P. A. Khlebnikov, A. L. Obermiller, L. A. Beckers, and Doctor of Medicine V. I. Tarasov. The nurses, in whose training Pirogov took part, represented the Exaltation of the Cross community of sisters of mercy, which had just been established on the initiative of Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna. Pirogov was the chief surgeon of the city of Sevastopol besieged by the Anglo-French troops.

Operating on the wounded, for the first time in the history of Russian medicine, Pirogov used a plaster cast, giving rise to a savings tactic in the treatment of limb injuries and saving many soldiers and officers from amputation. During the siege of Sevastopol, Pirogov supervised the training and work of the sisters of the Exaltation of the Cross Community of Sisters of Mercy. It was also an innovation at the time.

The most important merit of Pirogov is the introduction in Sevastopol of a completely new method of caring for the wounded. The method lies in the fact that the wounded were subject to careful selection already at the first dressing station; depending on the severity of the injuries, some of them were subject to immediate operation in the field, while others, with lighter injuries, were evacuated inland for treatment in stationary military hospitals. Therefore, Pirogov is rightly considered the founder of a special area in surgery, known as military field surgery.

For merits in helping the wounded and sick, Pirogov was awarded the Order of St. Stanislav, 1st degree.

In 1855, Pirogov was elected an honorary member of the Imperial Moscow University. In the same year, at the request of the St. Petersburg doctor N. F. Zdekauer, N. I. Pirogov, who at that time was the head teacher of the Simferopol gymnasium, D. I. Mendeleev, who had experienced health problems from his youth (it was even suspected that he had consumption ). Ascertaining the satisfactory condition of the patient, Pirogov said: “You will outlive both of us” - this predestination not only instilled in the future great scientist confidence in the favor of fate, but also came true.

After the Crimean War

Despite the heroic defense, Sevastopol was taken by the besiegers, and the Crimean War was lost by the Russian Empire.

Returning to St. Petersburg, Pirogov, at a reception at Alexander II, told the emperor about the problems in the troops, as well as about the general backwardness of the Russian Imperial Army and its weapons. The emperor did not want to listen to Pirogov. After this meeting, the subject of Pirogov's activity changed - he was sent to Odessa to the post of trustee of the Odessa educational district. This decision of the emperor can be seen as a manifestation of his disfavor, but at the same time, Pirogov had already been granted a life pension of 1,849 rubles and 32 kopecks a year.

On January 1, 1858, Pirogov was promoted to the rank of Privy Councilor, and then transferred to the post of trustee of the Kiev educational district, and in 1860 he was awarded the Order of St. Anna, 1st degree. He tried to reform the existing education system, but his actions led to a conflict with the authorities, and he had to leave the post of trustee of the Kiev educational district. At the same time, on March 13, 1861, he was appointed a member of the Main Board of Schools, after the liquidation of which in 1863, he was for life under the Ministry of Public Education of the Russian Empire.

Pirogov was sent to supervise Russian candidate professors studying abroad. “For his work when he was a member of the Main Board of Schools,” Pirogov was kept 5,000 rubles a year.

He chose Heidelberg as his residence, where he arrived in May 1862. The candidates were very grateful to him; this, for example, was warmly recalled by the Nobel laureate I. I. Mechnikov. There he not only fulfilled his duties, often traveling to other cities where the candidates studied, but also provided them and their family members and friends with any assistance, including medical assistance, and one of the candidates, the head of the Russian community of Heidelberg, held a fundraiser for the treatment of Giuseppe Garibaldi and persuaded Pirogov to examine the most wounded Garibaldi. Pirogov refused money, but went to Garibaldi and found a bullet not noticed by other world-famous doctors and insisted that Garibaldi leave the climate harmful to his wound, as a result of which the Italian government released Garibaldi from captivity. According to the general opinion, it was N.I. Pirogov who then saved the leg, and, most likely, the life of Garibaldi, “condemned” by other doctors. In his "Memoirs" Garibaldi recalls: "The outstanding professors Petridge, Nelaton and Pirogov, who showed generous attention to me when I was in a dangerous state, proved that there are no boundaries for good deeds, for true science in the family of mankind ... ". After this incident, which caused a furor in St. Petersburg, there was an attempt on Alexander II by nihilists who admired Garibaldi, and, most importantly, Garibaldi's participation in the war of Prussia and Italy against Austria, which displeased the Austrian government, and the "red" Pirogov was relieved of his duties , but at the same time retained the status of an official and the previously assigned pension.

In the prime of his creative powers, Pirogov retired to his small estate "Cherry" not far from Vinnitsa, where he organized a free hospital. He briefly traveled from there only abroad, and also at the invitation of the Imperial St. Petersburg University to give lectures. By this time, Pirogov was already a member of several foreign academies. For a relatively long time, Pirogov left the estate only twice: the first time in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian war, being invited to the front on behalf of the International Red Cross, and the second time in 1877-1878 - already at a very old age - he worked at the front for several months during the Russian-Turkish war. In 1873, Pirogov was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, 2nd degree.

Russian-Turkish war (1877-1878)

When Emperor Alexander II visited Bulgaria in August 1877, during the Russo-Turkish War, he remembered Pirogov as an incomparable surgeon and the best organizer of the medical service at the front. Despite his advanced age (then Pirogov was already 67 years old), Nikolai Ivanovich agreed to go to Bulgaria, provided that he was given complete freedom of action. His desire was granted, and on October 10, 1877, Pirogov arrived in Bulgaria, in the village of Gorna-Studena, not far from Plevna, where the main apartment of the Russian command was located.

Pirogov organized the treatment of soldiers, care for the wounded and sick in military hospitals in Svishtov, Zgalev, Bolgaren, Gorna-Studena, Veliko Tarnovo, Bokhot, Byala, Plevna. From October 10 to December 17, 1877, Pirogov traveled over 700 km in a cart and sleigh, over an area of 12,000 square meters. km, occupied by the Russians between the rivers Vit and Yantra. Nikolai Ivanovich visited 11 Russian military temporary hospitals, 10 divisional infirmaries and 3 pharmacy warehouses stationed in 22 different settlements. During this time, he was engaged in treatment and operated on both Russian soldiers and many Bulgarians. In 1877, Pirogov was awarded the Order of the White Eagle and a gold snuffbox decorated with diamonds with a portrait of Alexander II.

In 1881, N. I. Pirogov became the fifth honorary citizen of Moscow "in connection with fifty years of labor activity in the field of education, science and citizenship." He was also elected a corresponding member of the Imperial St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences (IAN) (1846), the Medical and Surgical Academy (1847, an honorary member since 1857) and the German Academy of Naturalists "Leopoldina" (1856).

Last days

In early 1881, Pirogov drew attention to pain and irritation on the mucous membrane of the hard palate. On May 24, 1881, N.V. Sklifosovsky established that Pirogov had cancer of the upper jaw. N. I. Pirogov died at 20:25 on November 23, 1881 in the village of Vyshnia (now part of the city of Vinnitsa).

Pirogov's body

On November 27 (December 9), 1881, D. I. Vyvodtsev was embalmed for four hours in the presence of two doctors and two paramedics (preliminary permission was obtained from the church authorities, who “taking into account the merits of N. I. Pirogov as an exemplary Christian and world famous the scientist was allowed not to bury the body, but to leave it incorruptible “so that the disciples and successors of the noble and charitable deeds of N.I. Pirogov could see his bright appearance””) and was buried in a tomb in his estate Cherry (now part of Vinnitsa). Three years later, a church was built over the tomb, the project of which was developed by V. I. Sychugov.

In the late 1920s, the crypt was visited by robbers who damaged the lid of the sarcophagus, stole Pirogov's sword (a gift from Franz Joseph) and a pectoral cross. In 1927, a special commission indicated in its report: “The precious remains of the unforgettable N.I. Pirogov, thanks to the all-destroying effect of time and complete homelessness, are in danger of undeniable destruction if the existing conditions continue.”

In 1940, an autopsy of the coffin with the body of N.I. Pirogov was carried out, as a result of which it was found that the examined parts of the body of the scientist and his clothes were covered with mold in many places; the remains of the body were mummified. The body was not removed from the coffin. The main measures for the preservation and restoration of the body were planned for the summer of 1941, but the Great Patriotic War began and, during the retreat of the Soviet troops, the sarcophagus with the body of Pirogov was hidden in the ground, while being damaged, which led to damage to the body, which was subsequently restored and repeatedly re-embalmed . E. I. Smirnov played an important role in this.

Despite the fact that during the Second World War in the vicinity of Vinnitsa (Ukrainian SSR) from July 16, 1942 to March 15, 1944, one of Hitler's Werwolf headquarters was located, the Nazis did not dare to disturb the ashes of the famous surgeon.

Officially, Pirogov's tomb is called the "church-necropolis", the body is located slightly below ground level in the crypt - the basement of the Orthodox church, in a glazed sarcophagus, which can be accessed by those wishing to pay tribute to the memory of the great scientist.

Family

- First wife (since December 11, 1842) - Ekaterina Dmitrievna Berezina(1822-1846), a representative of an ancient noble family, the granddaughter of the infantry general Count N. A. Tatishchev. She died at the age of 24 from complications after childbirth.

- A son - Nicholas(1843-1891), physicist.

- A son - Vladimir(1846 - after November 13, 1910), historian and archaeologist. He was a professor at the Imperial Novorossiysk University at the Department of History. In 1910, he temporarily lived in Tiflis and was present on November 13-26, 1910 at an extraordinary meeting of the Imperial Caucasian Medical Society, dedicated to the memory of N. I. Pirogov.

- Second wife (since June 7, 1850) - Alexandra von Bystrom(1824-1902), baroness, daughter of Lieutenant General A. A. Bistrom, great-niece of the navigator I. F. Kruzenshtern. The wedding was played in the potter's estate of the Linen Factory, and the sacrament of the wedding was performed on June 7/20, 1850 in the local Transfiguration Church. For a long time, Pirogov was credited with the authorship of the article “The Ideal of a Woman”, which is a selection from the correspondence of N. I. Pirogov with his second wife. In 1884, the work of Alexandra Antonovna opened a surgical hospital in Kyiv.

The value of scientific activity

Sketch by I. E. Repin for the painting "The arrival of Nikolai Ivanovich Pirogov to Moscow for the anniversary on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his scientific activity" (1881). Military Medical Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Sketch by I. E. Repin for the painting "The arrival of Nikolai Ivanovich Pirogov to Moscow for the anniversary on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his scientific activity" (1881). Military Medical Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

The main significance of the activity of N. I. Pirogov is that with his selfless and often disinterested work he turned surgery into a science, arming doctors with scientifically based methods of surgical intervention. In terms of his contribution to the development of military field surgery, he can be placed next to Larrey.

A rich collection of documents related to the life and work of N. I. Pirogov, his personal belongings, medical instruments, lifetime editions of his works are stored in the funds of the Military Medical Museum in St. Petersburg. Of particular interest are the two-volume manuscript of the scientist “Questions of life. Diary of an old doctor” and a suicide note left by him indicating the diagnosis of his illness.

Contribution to the development of national pedagogy

In the classic article "Questions of Life" Pirogov considered the fundamental problems of education. He showed the absurdity of class education, the discord between school and life, put forward the formation of a highly moral personality, ready to renounce selfish aspirations for the good of society, as the main goal of education. Pirogov believed that for this it was necessary to rebuild the entire education system based on the principles of humanism and democracy. The education system that ensures the development of the individual must be based on a scientific basis, from primary to higher education, and ensure the continuity of all education systems.

Pedagogical views: Pirogov considered the main idea of universal education, the education of a citizen useful to the country; noted the need for social preparation for life of a highly moral person with a broad moral outlook: “ Being human is what education should lead to»; upbringing and education should be in their native language. " Contempt for the native language dishonors the national feeling". He pointed out that the basis of subsequent professional education should be a broad general education; proposed to attract prominent scientists to teaching in higher education, recommended to strengthen the conversations of professors with students; fought for general secular education; urged to respect the personality of the child; fought for the autonomy of higher education.

Criticism of class vocational education: Pirogov opposed the class school and early utilitarian-professional training, against the early premature specialization of children; believed that it hinders the moral education of children, narrows their horizons; condemned arbitrariness, the barracks regime in educational institutions, thoughtless attitude towards children.

Didactic ideas: teachers should discard old dogmatic ways of teaching and apply new methods; it is necessary to awaken the thought of students, to instill the skills of independent work; the teacher must draw the attention and interest of the student to the reported material; transfer from class to class should be based on the results of annual performance; in transfer exams there is an element of chance and formalism.

Physical punishment. In this regard, he was a follower of J. Locke, considering corporal punishment as a means of humiliating a child, causing irreparable damage to his morals, accustoming him to slavish obedience, based only on fear, and not on understanding and evaluating his actions. Slave obedience forms a vicious nature, seeking retribution for its humiliation. N. I. Pirogov believed that the result of training and moral education, the effectiveness of the methods of maintaining discipline are determined by the objective, if possible, assessment by the teacher of all the circumstances that caused the misconduct, and the imposition of a punishment that does not frighten and humiliate the child, but educates him. Condemning the use of the rod as a means of disciplinary action, he allowed the use of physical punishment in exceptional cases, but only by order of the pedagogical council. Despite such an ambiguity in the position of N.I. Pirogov, it should be noted that the question he raised and the discussion that followed on the pages of the press had positive consequences: “The Charter of gymnasiums and progymnasiums” of 1864, corporal punishment was abolished.

The system of public education according to N. I. Pirogov:

- Elementary (primary) school (2 years), arithmetic, grammar are studied;

- Incomplete secondary school of two types: classical gymnasium (4 years, general education); real progymnasium (4 years);

- Secondary school of two types: classical gymnasium (5 years of general education: Latin, Greek, Russian, literature, mathematics); real gymnasium (3 years, applied nature: professional subjects);

- Higher school: universities higher educational institutions.

Memory

Within the boundaries of Vinnitsa in the village. Pirogovo is the museum-estate of N. I. Pirogov, a kilometer from which there is a church-tomb, where the embalmed body of an outstanding surgeon rests. Pirogov readings are regularly held there. The Pirogov Society, which existed in 1881-1922, was one of the most authoritative associations of Russian doctors of all specialties. Conferences of doctors of the Russian Empire were called Pirogov congresses. In Soviet times, monuments to Pirogov were erected in Moscow, Leningrad, Sevastopol, Vinnitsa, Dnepropetrovsk, and Tartu. Many memorable signs are dedicated to Pirogov in Bulgaria; There is also a park-museum “N. I. Pirogov. The name of the outstanding surgeon was given to the Russian National Research Medical University. See the page Memory of Pirogov for more details.

Nikolai Ivanovich Pirogov(November 13; Moscow - November 23 [December 5], the village of Cherry (now within the boundaries of Vinnitsa), (Podolsk province) - Russian surgeon and anatomist, naturalist and teacher, creator of the first atlas of topographic anatomy, founder of Russian military field surgery, founder of the Russian school of anesthesia Privy advisor .

Encyclopedic YouTube

-

1 / 5

Nikolai Ivanovich was born in 1810 in the family of the military treasurer, Major Ivan Ivanovich Pirogov (1772-1826), in Moscow, the 13th child in the family (according to three different documents stored in the Dorpat University, N. I. Pirogov was born on two years earlier - November 13, 1808). Mother Elizaveta Ivanovna Novikova belonged to an old Moscow merchant family. He received his primary education at home, 1822-1824. studied at a private boarding school, which he had to leave because of the deteriorating financial situation of his father. In 1824, he entered the medical faculty of Moscow University as a student of his own (in the petition he indicated that he was 16 years old; despite the need for a family, Pirogov’s mother refused to give him to state students, “it was considered as if something humiliating”). He listened to the lectures of H.I. Loder, M. Ya.

In 1828 he graduated from the course with a degree in medicine and was enrolled in the pupils, opened at the University of Derpt for the training of future professors of Russian universities. Pirogov studied under the guidance of Professor I.F. Moyer, in whose house he met V.A. Zhukovsky, and at Dorpat University he became friends with V.I.Dal. In 1833, after defending his dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Medicine, he was sent to study at the University of Berlin along with a group of 11 of his comrades from the Professorial Institute (including F. I. Inozemtsev, D. L. Kryukov, M. S. Kutorga, V. S. Pecherin , A. M. Filomafitsky , A. I. Chivilev) .

After returning to Russia (1836), at the age of twenty-six, he was appointed professor of theoretical and practical surgery at Dorpat University. In 1841, Pirogov was invited to St. Petersburg, where he headed the Department of Surgery at the Medical-Surgical Academy. At the same time, Pirogov led the Clinic of Hospital Surgery organized by him. Since Pirogov's duties included the training of military surgeons, he began to study the surgical methods common in those days. Many of them were radically reworked by him; in addition, Pirogov developed a number of completely new techniques, thanks to which he managed more often than other surgeons to avoid amputation of limbs. One of these techniques is still called "Operation Pirogov"

In search of an effective teaching method, Pirogov decided to apply anatomical studies on frozen corpses. Pirogov himself called this "ice anatomy". Thus was born a new medical discipline - topographic anatomy. After several years of such study of anatomy, Pirogov published the first anatomical atlas entitled "Topographic anatomy, illustrated by cuts made through the frozen human body in three directions," which became an indispensable guide for surgeons. From that moment on, surgeons were able to operate with minimal trauma to the patient. This atlas and the technique proposed by Pirogov became the basis for the entire subsequent development of operative surgery.

In 1847, Pirogov left for the active army in the Caucasus, as he wanted to test the operating methods he had developed in the field. In the Caucasus, he first used dressing with bandages soaked in starch; starch dressing proved to be more convenient and stronger than previously used splints. At the same time, Pirogov, the first in the history of medicine, began to operate on the wounded with ether anesthesia in the field, having performed about 10 thousand operations under ether anesthesia. In October 1847, he received the rank of actual State Councilor.

In 1855, Pirogov was elected an honorary member of the Moscow University. In the same year, at the request of the St. Petersburg doctor N.F. Zdekauer, N.I. Pirogov, who at that time was the head teacher of the Simferopol gymnasium D.I. consumption); stating the satisfactory condition of the patient, Pirogov declared: “You will outlive both of us” - this predestination not only instilled in the future great scientist confidence in the favor of fate for him, but also came true.

Crimean War

Operating on the wounded, for the first time in the history of Russian medicine, Pirogov used a plaster bandage, giving rise to a savings tactic for treating limb injuries and saving many soldiers and officers from amputation. During the siege of Sevastopol, Pirogov supervised the training and work of the sisters of the Exaltation of the Cross Community of Sisters of Mercy. It was also an innovation at the time.

The most important merit of Pirogov is the introduction in Sevastopol of a completely new method of caring for the wounded. The method lies in the fact that the wounded were subject to careful selection already at the first dressing station; depending on the severity of the injuries, some of them were subject to immediate operation in the field, while others, with lighter injuries, were evacuated inland for treatment in stationary military hospitals. Therefore, Pirogov is justly considered the founder of a special area in surgery, known as military field surgery.

For merits in helping the wounded and sick, Pirogov was awarded the Order of St. Stanislav, 1st degree.

After the Crimean War

Despite the heroic defense, Sevastopol was taken by the besiegers, and the Crimean War was lost by Russia. Returning to St. Petersburg, at a reception at Alexander II, Pirogov told the emperor about problems in the troops, as well as about the general backwardness of the Russian army and its weapons. The emperor did not want to listen to Pirogov.

After this meeting, the subject of Pirogov's activity changed - he was sent to Odessa to the post of trustee of the Odessa educational district. Such a decision by the emperor can be regarded as a manifestation of his disfavor, but at the same time, Pirogov had already been assigned a life pension of 1849 rubles and 32 kopecks a year; On January 1, 1858, Pirogov was promoted to the rank of Privy Councilor, and then transferred to the position of trustee of the Kiev educational district, and in 1860 he was awarded the Order of St. Anna, 1st degree.

Pirogov tried to reform the existing education system, but his actions led to a conflict with the authorities, and the scientist had to leave the post of trustee of the Kiev educational district. Pirogov remained in the position of a member of the Main Board of Schools, and after the liquidation of this board in 1863, he was under the Ministry of Public Education for life.

Pirogov was sent to supervise Russian candidate professors studying abroad. “For the labors when he was a member of the Main Board of Schools,” Pirogov was kept 5 thousand rubles a year.

He chose Heidelberg as his residence, where he arrived in May 1862. The candidates were very grateful to him; this, for example, was warmly recalled by the Nobel laureate I. I. Mechnikov. There he not only fulfilled his duties, often traveling to other cities where the candidates studied, but also provided them and their families and friends with any assistance, including medical assistance, and one of the candidates, the head of the Russian community of Heidelberg, held a fundraiser for the treatment of Garibaldi and persuaded Pirogov to examine the most wounded Garibaldi. Pirogov refused money, but went to Garibaldi and found a bullet not noticed by other world-famous doctors and insisted that Garibaldi leave the climate harmful to his wound, as a result of which the Italian government released Garibaldi from captivity. According to the general opinion, it was N.I. Pirogov who then saved the leg, and, most likely, the life of Garibaldi, who was convicted by other doctors. In his "Memoirs" Garibaldi recalls: "The outstanding professors Petridge, Nelaton and Pirogov, who showed generous attention to me when I was in a dangerous state, proved that there are no boundaries for good deeds, for true science in the family of mankind ... ". After this incident, which caused a furor in St. Petersburg, there was an attempt on Alexander II by nihilists who admired Garibaldi, and, most importantly, Garibaldi's participation in the war of Prussia and Italy against Austria, which displeased the Austrian government, and the "red" Pirogov was relieved of his duties , but at the same time retained the status of an official and the previously assigned pension.

In the prime of his creative powers, Pirogov retired to his small estate "Cherry" not far from Vinnitsa, where he organized a free hospital. He traveled from there for a short time only abroad, and also at the invitation of St. Petersburg University to give lectures. By this time, Pirogov was already a member of several foreign academies. For a relatively long time, Pirogov only left the estate twice: the first time in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War, being invited to the front on behalf of the International Red Cross, and the second time in 1877-1878 - already at a very old age - he worked at the front for several months during the Russian-Turkish war. In 1873, Pirogov was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, 2nd class.

Russian-Turkish war 1877-1878

Last days

At the beginning of 1881, Pirogov drew attention to pain and irritation on the mucous membrane of the hard palate, on May 24, 1881, N.V. Sklifosovsky established the presence of cancer of the upper jaw. N. I. Pirogov died at 20:25. November 23, 1881 in the village. Cherry, now part of Vinnitsa.

In the late 1920s, robbers visited the crypt, damaged the lid of the sarcophagus, stole Pirogov's sword (a gift from Franz Joseph) and a pectoral cross. In 1927, a special commission indicated in its report: “The precious remains of the unforgettable N.I. Pirogov, thanks to the all-destroying effect of time and complete homelessness, are in danger of undeniable destruction if the existing conditions continue.”

In 1940, an autopsy of the coffin with the body of N.I. Pirogov was carried out, as a result of which it was found that the examined parts of the body of the scientist and his clothes were covered with mold in many places; the remains of the body were mummified. The body was not removed from the coffin. The main measures for the preservation and restoration of the body were planned for the summer of 1941, but the Great Patriotic War began and, during the retreat of the Soviet troops, the sarcophagus with the body of Pirogov was hidden in the ground, while being damaged, which led to damage to the body, which was subsequently subjected to restoration and repeated reembalming . E.I. Smirnov played a big role in this.

Officially, the tomb of Pirogov is called the "church-necropolis", the body is located slightly below ground level in the crypt - the basement of the Orthodox church, in a glazed sarcophagus, which can be accessed by those wishing to pay tribute to the memory of the great scientist.

Meaning

The main significance of the activity of N. I. Pirogov is that with his selfless and often disinterested work he turned surgery into a science, arming doctors with scientifically based methods of surgical intervention. In terms of his contribution to the development of military field surgery, he can be placed next to Larrey.

A rich collection of documents related to the life and work of N. I. Pirogov, his personal belongings, medical instruments, lifetime editions of his works are stored in the funds of the Military Medical Museum in St. Petersburg. Of particular interest are the two-volume manuscript of the scientist “Questions of life. Diary of an old doctor” and a suicide note left by him indicating the diagnosis of his illness.

Contribution to the development of national pedagogy

In the classic article "Questions of Life" Pirogov considered the fundamental problems of education. He showed the absurdity of class education, the discord between school and life, put forward the formation of a highly moral personality, ready to renounce selfish aspirations for the good of society, as the main goal of education. Pirogov believed that for this it was necessary to rebuild the entire education system based on the principles of humanism and democracy. The education system that ensures the development of the individual must be based on a scientific basis, from primary to higher education, and ensure the continuity of all education systems.

Pedagogical views: Pirogov considered the main idea of universal education, the education of a citizen useful to the country; noted the need for social preparation for life of a highly moral person with a broad moral outlook: “ Being human is what education should lead to»; upbringing and education should be in their native language. " Contempt for the native language dishonors the national feeling". He pointed out that the basis of subsequent professional education should be a broad general education; proposed to attract prominent scientists to teaching in higher education, recommended to strengthen the conversations of professors with students; fought for general secular education; urged to respect the personality of the child; fought for the autonomy of higher education.

Criticism of class vocational education: Pirogov opposed the class school and early utilitarian-professional training, against the early premature specialization of children; believed that it hinders the moral education of children, narrows their horizons; condemned arbitrariness, the barracks regime in educational institutions, thoughtless attitude towards children.

Didactic ideas: teachers should discard old dogmatic ways of teaching and apply new methods; it is necessary to awaken the thought of students, to instill the skills of independent work; the teacher must draw the attention and interest of the student to the reported material; transfer from class to class should be based on the results of annual performance; in transfer exams there is an element of chance and formalism.

The system of public education according to N. I. Pirogov:

Family

First wife (since December 11, 1842) - Ekaterina Dmitrievna Berezina(1822-46), representative of an ancient noble family, granddaughter of the infantry general Count N. A. Tatishchev. She died at the age of 24 from complications after childbirth. Sons - Nikolai (1843-1891) - physicist, Vladimir (1846-after 11/13/1910) - historian and archaeologist

Second wife (from June 7, 1850) - Baroness Alexandra von Bystrom(1824-1902), daughter of Lieutenant General A. A. Bistrom, great-niece of the navigator I. F. Kruzenshtern. The wedding was played in the potter's estate of the Linen Factory, and the sacrament of the wedding was performed on June 7/20, 1850 in the local Transfiguration Church. For a long time, Pirogov was credited with the authorship of the article “The Ideal of a Woman”, which is a selection from the correspondence of N. I. Pirogov with his second wife. In 1884, the work of Alexandra Antonovna opened a surgical hospital in Kyiv.

The descendants of N.I. Pirogov currently live in Greece, France, the United States and St. Petersburg.

Memory

The image of Pirogov in art

N. I. Pirogov is the main character in several works of fiction.

- The story of A. I. Kuprin "The Miraculous Doctor" (1897).

- Yu. P. Herman's stories "Bucephalus", "Drops of Inozemtsev" (published in 1941 under the title "Stories about Pirogov") and "Beginning" (1968).

- Roman B. Yu. Zolotarev and Yu. P. Tyurin "Privy Councilor" (1986).

Bibliography

- Complete course of applied anatomy of the human body. - St. Petersburg, 1843-1845.

- Anatomical images external view and position of organs in three main cavities of human body. - St. Petersburg, 1846. (2nd ed. - 1850)

- Report on travel in Caucasus 1847-1849 - St. Petersburg, 1849. (M.: State publishing house of medical literature, 1952)

- Pathological anatomy of Asiatic cholera. - St. Petersburg, 1849.

- Topographic anatomy according to cuts through frozen corpses. Tt. 1-4. - St. Petersburg, 1851-1854.

- - St. Petersburg, 1854

- The beginnings of general military field surgery, taken from observations of military hospital practice and memories of the Crimean War and the Caucasian expedition. Ch. 1-2. - Dresden, 1865-1866. (M., 1941.)

- university question. - St. Petersburg, 1863.

- Grundzüge der allgemeinen Kriegschirurgie: nach Reminiscenzen aus den Kriegen in der Krim und im Kaukasus und aus der Hospitalpraxis (Leipzig: Vogel, 1864.- 116) (German)

- Surgical anatomy of arterial trunks and fascia. Issue. 1-2. - St. Petersburg, 1881-1882.

- Works. T. 1-2. - St. Petersburg, 1887. (3rd ed., Kyiv, 1910).

- Sevastopol letters N.I. Pirogov 1854-1855 . - St. Petersburg, 1899.

- Unpublished pages from the memoirs of N. I. Pirogov. (Political confession of N. I. Pirogov) // About the past: a historical collection. - St. Petersburg: Typo-lithography B. M. Wolf, 1909.

- Questions of life. Diary of an old doctor. Edition of the Pirogov t-va. 1910

- Works on experimental, operational and military field surgery (1847-1859) T 3. M.; 1964

- Sevastopol letters and memoirs. - M.: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1950. - 652 p. [Contents: Sevastopol Letters; memories of the Crimean War; From the diary of the "Old Doctor"; Letters and documents].

- Selected pedagogical works / Entry. Art. V. Z. Smirnova. - M .: Publishing House of Acad. ped. Sciences of the RSFSR, 1952. - 702 p.

- Selected pedagogical works. - M.: Pedagogy, 1985. - 496 p.

Notes

- Kulbin N. I.// Russian biographical dictionary: in 25 volumes. - St. Petersburg. - M., 1896-1918.

- Pirogovskaya street // Evening courier. - November 22, 1915.

- Biographical dictionary of professors and teachers Imperial Yurievsky, former Derpt University for one years of its existence (1802-1902) Vol II. - S. 261

- , from. 558.

- , from. 559.

- When choosing candidates for the department of the same name at Moscow University, preference was given to F. I. Inozemtsev.

- Pirogov Nikolai Ivanovich on the site "Chronicle of Moscow University".

- Chronicle of the life and work of D. I. Mendeleev. - L .: Nauka, 1984.

- Sevastopol letters N.I. Pirogov 1854-1855 - SPb., 1907.

- Nikolay Marangozov. Nikolay Pirogov v. Duma (Bulgaria), November 13, 2003

- Gorelova L. E. Mystery N.I. Pirogov // Russian Medical Journal. - 2000. - V. 8, No. 8. - S. 349.

- Shevchenko Yu. L., Kozovenko M. N. Museum of N. I. Pirogov. - St. Petersburg, 2005. - S. 24.

- Long-term preservation of the embalmed body of N. I. Pirogov - a unique scientific experiment // Biomedical and Biosocial Anthropology. - 2013. - V. 20. - P. 258.

- Last shelter Pirogov

- Russian newspaper - Monument to the living for the salvation of the dead

- Location Tombs N.I. Pirogov on map Vinnitsa

- History of Pedagogy and Education. From the origin of education in primitive society to the end of the 20th century: Textbook for pedagogical educational institutions / Ed. A. I. Piskunova.- M., 2001.

- History of Pedagogy and Education. From the origin of education in primitive society to the end of the 20th century: A textbook for pedagogical educational institutions / Ed. A. I. Piskunova. - M., 2001.

- Kodzhaspirova G. M. History of education and pedagogical thought: tables, diagrams, reference notes. - M., 2003. - S. 125.

- He was a professor at Novorossiysk University in the Department of History. In 1910 he temporarily lived in

Nikolay Ivanovich Pirogov(1810-1881) - Russian surgeon and anatomist, teacher, public figure, founder of military field surgery and anatomical and experimental direction in surgery, corresponding member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences (1846). Member of the Sevastopol defense (1854-1855), Franco-Prussian (1870-1871) and Russian-Turkish (1877-1878) wars. For the first time, he performed an operation under anesthesia on the battlefield (1847), introduced a fixed plaster cast, and proposed a number of surgical operations. He fought against class prejudices in the field of education, advocated the autonomy of universities, universal primary education. Pirogov's atlas "Topographic Anatomy" (vols. 1-4, 1851-54) received worldwide fame.

Future great doctor Kolya Pirogov was born November 25 (November 13 old style) 1810 in Moscow. His father (who served as treasurer) Ivan Ivanovich Pirogov had fourteen children, most of whom died in infancy; of the six survivors, Nikolai was the youngest.

Religion everywhere, for all peoples, was only a bridle.

Pirogov Nikolay Ivanovich

An acquaintance of the family helped him get an education - a well-known Moscow doctor, professor of Moscow University E. Mukhin, who noticed the boy's abilities and began to work with him individually.

When Nikolai was fourteen years old, he entered the medical faculty of Moscow University. To do this, he had to add two years to himself, but he passed the exams no worse than his older comrades. Pirogov studied easily. In addition, he had to constantly earn extra money to help his family. Finally, Pirogov managed to get a job as a dissector in the anatomical theater. This job gave him invaluable experience and convinced him that he should become a surgeon.

After graduating from the university, one of the first in terms of academic performance, Nikolai Pirogov went to prepare for a professorship at the Yuryev University in the city of Tartu. At that time, this university was considered the best in Russia. Here in the surgical clinic. Pirogov worked for five years, brilliantly defended his doctoral dissertation, and at the age of twenty-six he became a professor of surgery.

Books are society. A good book, like a good society, enlightens and ennobles feelings and morals. Tell me what books you read and I'll tell you who you are!

Pirogov Nikolay Ivanovich

Nikolai Pirogov chose the ligation of the abdominal aorta as the subject of his dissertation, which had been performed until that time - and then with a fatal outcome - only once by the English surgeon Astley Cooper. The conclusions of the Pirogov dissertation were equally important for both theory and practice. He was the first to study and describe the topography, that is, the location of the abdominal aorta in humans, circulatory disorders during its ligation, the circulatory pathways with its obstruction, and explained the causes of postoperative complications. Nikolai proposed two ways to access the aorta: transperitoneal and extraperitoneal. When any damage to the peritoneum threatened death, the second method was especially necessary. Astley Cooper, who for the first time bandaged the aorta in an transperitoneal way, said, having become acquainted with Pirogov's dissertation, that if he had to do the operation again, he would have chosen a different method. Is this not the highest recognition!

When Nikolai Ivanovich, after five years in Dorpat, went to Berlin to study, the illustrious surgeons, to whom he went with a respectfully bowed head, read his dissertation, hastily translated into German. He found a teacher who, more than others, combined everything that he was looking for in the surgeon Pirogov, not in Berlin, but in Göttingen, in the person of Professor Langenbeck. The Göttingen professor taught him the purity of surgical techniques. He taught him to hear the whole and complete melody of the operation. He showed Pirogov how to adapt the movements of the legs and the whole body to the actions of the operating hand. He hated slowness and demanded fast, precise and rhythmic work.

Looking around, you see yourself in a uniform with a red collar, all buttons are fastened, everything is as it should be, in order. You have heard before that you are a boy. Now you see it in action. Are you asking who you are?

Pirogov Nikolay Ivanovich

Returning home, Pirogov fell seriously ill and was left for treatment in Riga. Riga was lucky: if Pirogov had not fallen ill, she would not have become a platform for his rapid recognition. As soon as Nikolai Pirogov got up from the hospital bed, he undertook to operate. The city had heard rumors before about the promising young surgeon. Now it was necessary to confirm the good reputation that ran far ahead.

N. Pirogov began with rhinoplasty: he carved out a new nose for a noseless barber. Then he recalled that it was the best nose he had ever made in his life. Plastic surgery was followed by the inevitable amputations and removal of tumors. In Riga, he operated for the first time as a teacher.

From Riga, Nikolai went to Dorpat, where he learned that the Moscow department promised to him had been given to another candidate. But he was lucky - Iva Filippovich Moyer gave the student his clinic in Dorpat.

One of the most significant works of Nikolai Pirogov is the “Surgical Anatomy of Arterial Trunks and Fascias” completed in Derpt. Already in the name itself, gigantic layers are raised - surgical anatomy, a science that Pirogov created from his first, youthful works, erected, and the only pebble that started the movement of the bulk of the fascia.

Without inspiration there is no will, without will there is no struggle, and without struggle there is nothingness and arbitrariness.

Pirogov Nikolay Ivanovich

Before Pirogov, they almost did not deal with fascia: they knew that there were such fibrous fibrous plates, membranes surrounding muscle groups or individual muscles, they saw them, opening corpses, stumbled upon them during operations, cut them with a knife, not attaching importance to them.

Nikolai Pirogov began with a very modest task: he undertook to study the direction of fascial membranes. Having learned the particular, the course of each fascia, he went to the general and deduced certain patterns of the position of the fascia relative to nearby vessels, muscles, nerves, discovered certain anatomical patterns.

To live in this world means to constantly fight and constantly win.

Pirogov Nikolay Ivanovich

Everything that Nikolai Ivanovich Pirogov discovered was not necessary for him in itself, he needed all this in order to indicate the best methods for performing operations, first of all, “to find the right way to ligate this or that artery,” as he said. This is where the new science created by Pirogov begins - this is surgical anatomy.

Why does a surgeon need anatomy at all, he asked: is it just to know the structure of the human body? And he answers: no, not only! A surgeon, explained Pirogov, should not deal with anatomy in the same way as an anatomist. Thinking about the structure of the human body, the surgeon cannot for a moment lose sight of what the anatomist does not even think about - the landmarks that will show him the way during the operation.

Nikolai Pirogov supplied the description of operations with drawings. Nothing like the anatomical atlases and tables that were used before him. No discounts, no conventions - the greatest accuracy of the drawings: the proportions are not violated, every branch, every knot, lintel is preserved and reproduced. Pirogov, not without pride, suggested that patient readers check any detail of the drawings in the anatomical theater. He did not yet know that he had new discoveries ahead of him, the highest precision ...

Without common sense, all moral rules are unreliable.

Pirogov Nikolay Ivanovich

In the meantime, he went to France, where five years earlier, after a professorial institute, the authorities did not want to let him go. In the Parisian clinics, he grasped some interesting details and did not find anything unknown. It is curious: as soon as he was in Paris, Nikolai Pirogov hurried to the famous professor of surgery and anatomy Velpo and found him reading "The Surgical Anatomy of the Arterial Trunks and Fascia" ...

In 1841, Pirogov was invited to the Department of Surgery at the Medical and Surgical Academy of St. Petersburg. Here the scientist worked for more than ten years and created the first surgical clinic in Russia. In it, he founded another branch of medicine - hospital surgery.

Pirogov came to the capital as a winner. Three hundred people crowded into the auditorium where he taught surgery courses, no less: not only doctors crowded on the benches, students from other educational institutions, writers, officials, military men, artists, engineers, even Ladies came to listen to Pirogov. Newspapers and magazines wrote about him, compared his lectures with the concerts of the famous Italian Angelica Catalani, that is, with divine singing, they compared his speech about incisions, stitches, purulent inflammations and the results of autopsies.

Nikolai Ivanovich Pirogov was appointed director of the Tool Factory, and he agreed. Now he was inventing instruments with which any surgeon would perform the operation well and quickly. He was asked to accept a consultant position in one hospital, another, a third, and again he agreed.

But not only well-wishers surrounded the scientist. He had a lot of envious people and enemies who were disgusted by the zeal and fanaticism of the doctor. In the second year of life in St. Petersburg, Nikolai Pirogov fell seriously ill, poisoned by hospital miasma and the bad air of the dead. I couldn't get up for a month and a half. He felt sorry for himself, poisoned his soul with sorrowful thoughts about years lived without love and lonely old age.

He went over in his memory all those who could bring him family love and happiness. The most suitable of them seemed to him Ekaterina Dmitrievna Berezina, a girl from a well-born, but collapsed and greatly impoverished family. A hurried modest wedding took place.

Pirogov had no time - great things were waiting for him. He simply locked his wife within the four walls of a rented and, on the advice of acquaintances, furnished apartment. He didn’t take her to the theater, because he disappeared until late in the anatomical theater, he didn’t go to balls with her, because balls were idleness, he took away her novels and slipped scientific journals in her place. Pirogov jealously pushed his wife away from her friends, because she had to belong entirely to him, just as he belongs entirely to science. And for a woman, probably, there was too much and too little of one great Pirogov.

Ekaterina Dmitrievna died in her fourth year of marriage, leaving Pirogov two sons: the second cost her her life. But in the difficult days of grief and despair for Nikolai Pirogov, a great event happened - his project of the world's first Anatomical Institute was approved by the highest.

On October 16, 1846, the first test of ether anesthesia took place. And he quickly began to conquer the world. In Russia, the first operation under anesthesia was performed on February 7, 1847 by Pirogov's comrade at the professorial institute, Fedor Ivanovich Inozemtsev. He headed the Department of Surgery at Moscow University.

Nikolay Ivanovich performed the first operation with the use of anesthesia a week later. But from February to November 1847, Inozemtsev performed eighteen operations under anesthesia, and by May 1847 Pirogov had received the results of fifty. During the year, six hundred and ninety operations were performed under anesthesia in thirteen cities of Russia. Three hundred of them are from Pirogovo!

Soon, Nikolai Ivanovich took part in hostilities in the Caucasus. Here, in the village of Salty, for the first time in the history of medicine, he began to operate on the wounded with ether anesthesia. In total, the great surgeon performed about 10,000 operations under ether anesthesia.

Once, while walking through the market, Pirogov saw how butchers were sawing cow carcasses into pieces. The scientist drew attention to the fact that the location of the internal organs is clearly visible on the cut. After some time, he tried this method in the anatomical theater, sawing frozen corpses with a special saw. Pirogov himself called this "ice anatomy". Thus was born a new medical discipline - topographic anatomy.

With the help of cuts made in this way, N. Pirogov compiled the first anatomical atlas, which became an indispensable guide for surgeons. Now they have the opportunity to operate, causing minimal injury to the patient. This atlas and the technique proposed by Pirogov became the basis for the entire subsequent development of operative surgery.

After the death of Ekaterina Dmitrievna Pirogov was left alone. "I don't have any friends," he admitted with his usual frankness. And at home, the boys, sons, Nikolai and Vladimir were waiting for him. Pirogov twice unsuccessfully tried to marry for convenience, which he did not consider it necessary to hide from himself, from acquaintances, it seems that from the girls planned to be the bride.

In a small circle of acquaintances, where Nikolai Ivanovich sometimes spent evenings, he was told about the twenty-two-year-old Baroness Alexandra Antonovna Bistrom, who enthusiastically read and reread his article on the ideal of a woman. The girl feels like a lonely soul, thinks a lot and seriously about life, loves children. In conversation, she was called "a girl with convictions."

Pirogov proposed to Baroness Bistrom. She agreed. Going to the estate of the bride's parents, where it was supposed to play an inconspicuous wedding, Pirogov, confident in advance that the honeymoon, breaking his usual activities, would make him quick-tempered and intolerant, asked Alexandra Antonovna to pick up crippled poor people in need of an operation for his arrival: work will delight the first time love!

When the Crimean War began in 1853, Nikolai Ivanovich considered it his civic duty to go to Sevastopol. He was appointed to the active army. While operating on the wounded, Pirogov for the first time in the history of medicine used a plaster cast, which made it possible to speed up the healing process of fractures and saved many soldiers and officers from ugly curvature of the limbs.

The most important merit of Nikolai Pirogov is the introduction of sorting the wounded in Sevastopol: one operation was done directly in combat conditions, others were evacuated deep into the country after first aid. On his initiative, a new form of medical care was introduced in the Russian army - nurses appeared. Thus, it was Pirogov who laid the foundations of military field medicine.

After the fall of Sevastopol, Pirogov returned to St. Petersburg, where, at a reception at Alexander II, he reported on the mediocre leadership of the army by Prince Menshikov. The tsar did not want to heed the advice of Pirogov, and from that moment Nikolai Ivanovich fell out of favor.

He left the Medico-Surgical Academy. Appointed as a trustee of the Odessa and Kiev educational districts, Pirogov tried to change the system of school education that existed in them. Naturally, his actions led to a conflict with the authorities, and the scientist had to leave his post.

For some time, Nikolai Pirogov settled in his estate "Cherry" near Vinnitsa, where he organized a free hospital. He traveled from there only abroad, and also at the invitation of St. Petersburg University to give lectures. By this time, Pirogov was already a member of several foreign academies.

In May 1881, the fiftieth anniversary of Pirogov's scientific activity was solemnly celebrated in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The great Russian physiologist Ivan Mikhailovich Sechenov addressed him with a greeting. However, at that time the scientist was already terminally ill, and in the summer of 1881 he died on his estate.

The significance of the activities of Nikolai Ivanovich Pirogov lies in the fact that with his selfless and often disinterested work he turned surgery into a science, arming doctors with scientifically based methods of surgical intervention.

Shortly before his death, the scientist made another discovery - he proposed a completely new way of embalming the dead. To this day, the body of Pirogov himself, embalmed in this way, is kept in the church of the village of Vishni.

The memory of the great surgeon is preserved to this day. Every year on his birthday, a prize and a medal named after him are awarded for achievements in the field of anatomy and surgery. In the house where he lived Nikolai Pirogov, a museum of the history of medicine was opened, in addition, some medical institutions and city streets are named after him.

Nikolai Ivanovich Pirogov passed away December 5 (November 23, O.S.), 1881, in the village of Vishnya, now within the boundaries of Vinnitsa.

Portrait of Nikolai Pirogov by Ilya Repin, 1881.

There was no nose - and suddenly appeared

Nikolai Ivanovich Pirogov was born in 1810 in Moscow, in a poor, paradoxical as it may sound, family of a military treasurer. Major Ivan Ivanovich Pirogov was afraid to steal, but he had children without measure. The future father of Russian surgery was the thirteenth child.

So the boarding school, in which the boy had entered at the age of eleven, soon had to be left - there was nothing to pay for him.

However, he entered the university as a student of his own. Here the mother of the family, Elizaveta Ivanovna, nee Novikova, a lady of merchant blood, had already insisted. To be state-owned, that is, not to pay for education, seemed humiliating to her.

Nicholas was only fourteen at the time, but he said he was sixteen. The serious young man looked convincing, no one even doubted. The young man received his higher medical education at the age of seventeen. Then he went to probation in Dorpat.

At Dorpat University, the character of Nikolai Ivanovich was especially pronounced - in contrast to another future medical luminary, Fedor Inozemtsev. Ironically, they were placed in the same room. Comrades constantly came to the cheerful and merry Inozemtsev, played the guitar, cooked zhzhenka, dabbled in cigars. And poor Pirogov, who never let go of his textbook for a minute, had to endure all this.

It didn’t even occur to him to leave his studies for at least an hour and enjoy the romance of student life, ennobled by an early bald head and decorated with boring sideburns-brushes.

Then - the University of Berlin. There is not much study. And in 1836, Nikolai Ivanovich finally accepted the appointment of a professor of theoretical and practical surgery at the Imperial Derpt University, which he knew well. There, he first builds a nose for the barber Otto, and then for another Estonian girl. Literally builds like a surgeon. There was no nose - and suddenly it appeared. Pirogov took the skin for this wonderful decoration from the forehead of the patient.

Both were, of course, in seventh heaven with happiness. Oddly enough, the barber was especially jubilant, either having lost his nose in a fight, or accidentally cutting it off while serving another client: “During my suffering, they still took part in me; with the loss of the nose, it passed. Everything ran away from me, even my faithful wife. All my family has moved away from me; friends have left me. After a long retreat, I went one evening to a tavern. The owner asked me to leave at once.”

Meanwhile, Pirogov was already reporting on his plastic experiments to the scientific medical community, using a simple rag doll as a visual aid.

Life among the dead

The building of Dorpat University. Image from wikipedia.org

In Derpt, and then in the capital, the surgical talent of Nikolai Ivanovich is finally fully revealed. He cuts people almost non-stop. But his head is constantly working in favor of the patient. How can amputation be avoided? How to reduce pain? How will the unfortunate person live after the operation?

He invents a new surgical technique that went down in the history of medicine as Pirogov's operation. In order not to go into juicy medical details, the leg is not cut where it was cut before, but in a slightly different place, and as a result, one can hobble on what remains of it.

Today, this method is recognized as obsolete - there were too many problems in the postoperative period, Nikolai Ivanovich violated the laws of nature too radically. But then, in 1852, it was considered a great breakthrough.

St. Petersburg. Military-medical Academy. Image: retro-piter.livejournal.com

Another problem is how to reduce unnecessary movements with a scalpel, how to quickly determine exactly where surgery is required. Before Pirogov, no one was seriously engaged in this at all - they were poking around in a living person like a baby in a sandbox. He, studying frozen corpses (at the same time gave rise to a new direction - “ice anatomy”), compiled the first detailed anatomical atlas in history. A much-needed manual for fellow surgeons was published under the title "Topographic Anatomy Illustrated by Cuts Through the Frozen Human Body in Three Directions".

In fact, 3D.

True, this 3D cost him a month and a half of bed rest - he did not get out of the dead room for days, inhaled harmful fumes there and almost went to the forefathers himself.

Left much to be desired and surgical instruments of that time. What to do with it? Our hero is used to solving problems radically. He becomes, among other things, the director of the Tool Plant, where he actively improves the product range. Of course, due to products of their own invention.

Nikolai Ivanovich is worried about another serious problem - anesthesia. And not so much the first part of it - how to put a person to sleep before the operation, but the second - how to make sure that later he still wakes up. Our hero becomes the absolute champion in carrying out operations under the ether.

"Traumatic Epidemic"

In 1847, Pirogov, who had just received the title of Corresponding Member of the Imperial St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, went to the Caucasian War. It was there that he received unlimited opportunities for his ethereal experiments - the theater of war constantly supplied him with people in need of help.

He performed several thousand such operations, most of them successful. If a soldier can boast of how many people he took their lives, then Nikolai Ivanovich had a reverse count. He, in fact, pulled several thousand people out of the hands of death. He brought one of them back to life, and immediately they put another on the table.

You need to have some kind of completely superman psyche to withstand this. And Nikolai Pirogov was such a superman.

Then - another war, the Crimean. Experiments with ether continue. At the same time, plaster fixing bandages are being improved. Pirogov first began to use them during the Crimean campaign. But even in the Caucasus, starch dressings, also put into practice by Dr. Pirogov, were considered an unprecedented innovation. He overtook himself.

Plus a new approach to the evacuation of the wounded from the battlefield. Previously, everyone who was able to be pulled out was indiscriminately sent to the rear. Pirogov introduced just this analysis. The wounded were examined already at the field dressing station. Those who could be helped on the spot were released, and servicemen with serious injuries were sent to the rear hospital. Thus, such scarce places in military transport were given to those who really needed them.

The word “logistics” did not yet exist at that time, and Pirogov was already actively using it, but there, God forbid, modern supervisors never turn up.

And being the chief surgeon of the besieged Sevastopol is an enviable position, isn't it? - Nikolai Ivanovich debugged the work of the sisters of mercy to unprecedented perfection.

What kind of cellos, chess and jokes are there. He gutted living people from morning to night!

N.I. Pirogov. Photo by P.S. Zhukov, 1870. Image from wikipedia.org

Pirogov didn't even have friends. That's what he said to himself - "I have no friends." Calmly and without regret. About the war, he argued that it was a “traumatic epidemic”. It was vital for him to put everything in its place.

At the end of the war (which Russia, by the way, lost), Emperor Alexander Nikolayevich, the future tsar-liberator, summoned Pirogov for a report. Better not to call.

The doctor, without any respect and rank, dumped out to the emperor everything that he had learned about the unforgivable backwardness of the country both in military affairs and in medicine. The autocrat did not like this, and he, in fact, exiled the obstinate doctor out of sight - to Odessa, to the post of trustee of the Odessa educational district.

Herzen subsequently kicked the tsar in The Bell: "It was one of the most vile deeds of Alexander, dismissing a man Russia is proud of."

Alexander II, photo portrait, 1880. Image from runivers.ru

And suddenly, quite unexpectedly, a new stage in the activity of this great man began - pedagogical. Pirogov turned out to be a born teacher. In 1856, he published an article entitled "Questions of Life", in which, in fact, he considers questions of education.

The main idea of this is the need for a humane attitude of the teacher to the students. In everyone, one should first of all see a free personality, which should be respected unquestioningly.

He also complained about the fact that the existing educational system is aimed at training narrow-profile specialists: “I know very well that the gigantic successes of the sciences and arts of our century have made specialism a necessary need of society; but at the same time, true specialists have never needed so much a preliminary general human education as in our age.

A one-sided specialist is either a crude empiricist or a street charlatan.

This was especially true for the upbringing and education of young ladies. According to Nikolai Ivanovich, women's education should not be limited to homework skills. The doctor was not shy in his arguments: “What if a wife, calm, carefree in the family circle, looks at your cherished struggle with a senseless smile of an idiot? Or… squandering all the possible cares of domestic life, will be imbued with only one thought: to please and improve your material, earthly existence?

However, men also got it: “And what is it like for a woman in whom the need to love, participate and sacrifice is developed incomparably more and who still lacks enough experience to calmly endure the deceit of hope - tell me what it should be like for her in the field of life, going hand in hand hand with the one in which she was so pathetically deceived, who, correcting her consoling convictions, laughs at her shrine, jokes with her inspirations?

And, of course, no corporal punishment. Nikolai Ivanovich even devoted a separate note to this topical topic - “Is it necessary to flog children, and flog in the presence of other children?”

Pirogov, remembering his conversation with the tsar, was immediately suspected of excessive freethinking.

And he was transferred to Kyiv, where he took up the duties of a trustee of the Kiev educational district. There, thanks again to his principles, straightforwardness and disregard for ranks, Nikolai Ivanovich finally fell out of favor and was demoted to a simple member of the Main Board of Schools.