Application

In World War I, aviation was used to achieve three goals: reconnaissance, bombing, and destruction of enemy aircraft. Leading world powers have achieved great results in conducting combat operations with the help of aviation.

Aviation of the Central Powers

Aviation Germany

German aviation was the second largest aviation in the world at the beginning of the First World War. There were about 220-230 aircraft. But meanwhile, it is worth noting that these were outdated Taube-type aircraft; aviation was given the role of vehicles (then aircraft could carry 2-3 people). The expenses for it in the German army amounted to 322 thousand marks.

During the war, the Germans showed great attention to the development of their air forces, being among the first to appreciate the impact that the war in the air had on the war on the ground. The Germans sought to ensure air superiority by introducing technical innovations into aviation as quickly as possible (for example, fighter aircraft) and during a certain period from the summer of 1915 to the spring of 1916 they practically maintained dominance in the skies at the fronts.

The Germans also paid great attention to strategic bombing. Germany was the first country to use its air force to attack enemy strategic rear areas (factories, populated areas, sea harbors). Since 1914, first German airships and then multi-engine bombers regularly bombed rear targets in France, Great Britain and Russia.

Germany made a significant bet on rigid airships. During the war, more than 100 rigid airships of the Zeppelin and Schütte-Lanz design were built. Before the war, the Germans mainly planned to use airships for aerial reconnaissance, but it quickly turned out that airships were too vulnerable over land and in the daytime.

The main function of heavy airships was maritime patrol, maritime reconnaissance in the interests of the fleet and long-range night bombing. It was Zeppelin's airships that first brought to life the doctrine of long-range strategic bombing, carrying out raids on London, Paris, Warsaw and other rear cities of the Entente. Although the effect of the use, with the exception of individual cases, was mainly moral, blackout measures and air raids significantly disrupted the work of the Entente industry, which was not ready for such, and the need to organize air defense led to the diversion of hundreds of aircraft, anti-aircraft guns, and thousands of soldiers from the front line.

However, the advent of incendiary bullets in 1915, which could effectively destroy hydrogen-filled zeppelins, eventually led to the fact that from 1917, after heavy losses in the final strategic raids on London, airships were used only for maritime reconnaissance.

Aviation Austria-Hungary

Aviation of Turkey

Of all the warring powers, the Ottoman Empire's air force was the weakest. Although the Turks began to develop military aviation in 1909, the technological backwardness and extreme weakness of the industrial base of the Ottoman Empire meant that Turkey faced World War I with a very small air force. After entering the war, the Turkish aircraft fleet was replenished with more modern German aircraft. The Turkish Air Force reached the peak of its development - 90 aircraft in service and 81 pilots - in 1915.

There was no aircraft manufacturing in Turkey; the entire aircraft fleet was supplied from Germany. About 260 airplanes were delivered from Germany to Turkey in 1915-1918: in addition, a number of captured aircraft were restored and used.

Despite the weakness of the material part, the Turkish Air Force proved to be quite effective during the Dardanelles Operation and in the battles in Palestine. But since 1917, the arrival of new British and French fighters in large numbers at the front and the depletion of German resources led to the fact that the Turkish Air Force was practically exhausted. Attempts to change the situation were made in 1918, but did not end due to the revolution that took place.

Entente aviation

Russian Aviation

At the start of the First World War, Russia had the largest air fleet in the world with 263 aircraft. At the same time, aviation was in its formation stage. In 1914, Russia and France produced approximately the same number of aircraft and were the first in the production of airplanes among the Entente countries that year, yet lagging behind Germany in this indicator by 2.5 times. Contrary to generally accepted opinion, Russian aviation performed well in battles, but due to the weakness of the domestic aircraft industry (especially due to the low production of aircraft engines), it could not fully demonstrate its potential.

By July 14, the troops had 4 Ilya Muromets, the only serial multi-engine aircraft in the world at that time. In total, 85 copies of this world's first heavy bomber were produced during the war. However, despite individual manifestations of engineering art, the air force of the Russian Empire was inferior to the German, French and British, and since 1916, also to the Italian and Austrian. The main reason for the lag was the poor state of affairs with the production of aircraft engines and the lack of aircraft engineering capacity. Until the very end of the war, the country was unable to establish mass production of a domestic model fighter, forced to manufacture foreign (often outdated) models under license.

In terms of the volume of its airships, Russia ranked third in the world in 1914 (right after Germany and France), but its fleet of lighter-than-air ships was mainly represented by outdated models. The best Russian airships of the First World War were built abroad. In the 1914-1915 campaign, Russian airships managed to carry out only one combat mission, after which, due to technical wear and tear and the inability of industry to provide the army with new airships, work on controlled aeronautics was curtailed.

Also, the Russian Empire became the first country in the world to use aircraft. At the beginning of the war there were 5 such ships in the fleet.

UK Aviation

Great Britain was the first country to separate its air force into a separate branch of the military, not under the control of the army or navy. Royal Air Force Royal Air Force (RAF)) were formed on April 1, 1918 at the base of the predecessor Royal Flying Corps (eng. Royal Flying Corps (RFC)).

Great Britain became interested in the prospect of using aircraft in war back in 1909 and achieved significant success in this (although at that time it was somewhat behind the recognized leaders - Germany and France). Thus, already in 1912, the Vickers company developed an experimental fighter airplane armed with a machine gun. "Vickers Experimental Fighting Biplane 1" was demonstrated at maneuvers in 1913, and although at that time the military took a wait-and-see approach, it was this work that formed the basis for the world's first fighter airplane, the Vickers F.B.5, which took off in 1915.

By the beginning of the war, all British Air Forces were organizationally consolidated into the Royal Flying Corps, divided into naval and army branches. In 1914, the RFC consisted of 5 squadrons, totaling about 60 vehicles. During the war, their numbers grew sharply and by 1918 the RFC consisted of more than 150 squadrons and 3,300 aircraft, eventually becoming the largest air force in the world at that time.

During the war, the RFC carried out a variety of tasks, from aerial reconnaissance and bombing to the insertion of spies behind the front lines. RFC pilots pioneered many applications of aviation, such as the first use of specialized fighters, the first aerial photography, attacking enemy positions in support of troops, dropping saboteurs and defending their own territory from strategic bombing.

Britain also became the only country other than Germany that was actively developing a fleet of rigid-type airships. Back in 1912, the first rigid airship R.1 "Mayfly" was built in Great Britain, but due to damage during an unsuccessful launch from the boathouse, it never took off. During the war, a significant number of rigid airships were built in Britain, but for various reasons their military use did not begin until 1918 and was extremely limited (the airships were only used for anti-submarine patrols and had only one encounter with the enemy)

On the other hand, the British fleet of soft airships (which by 1918 numbered more than 50 airships) was very actively used for anti-submarine patrols and convoy escort, achieving significant success in the fight against German submarines.

Aviation France

French aviation, along with Russian aviation, showed its best side. Most of the inventions that improved the design of the fighter were made by French pilots. French pilots focused on practicing tactical aviation operations, and mainly focused their attention on confronting the German Air Force at the front.

French aviation did not carry out strategic bombing during the war. The lack of serviceable multi-engine aircraft constrained raids on Germany's strategic rear (as did the need to concentrate design resources on fighter production). In addition, French engine manufacturing at the beginning of the war was somewhat behind the best world level. By 1918, the French had created several types of heavy bombers, including the very successful Farman F.60 Goliath, but did not have time to use them in action.

At the beginning of the war, France had the second largest fleet of airships in the world, but it was inferior in quality to Germany: the French did not have rigid airships like Zeppelins in service. In 1914-1916, airships were quite actively used for reconnaissance and bombing operations, but their unsatisfactory flight qualities led to the fact that since 1917 all controlled aeronautics were concentrated only in the navy in patrol service.

Aviation Italy

Although Italian aviation was not among the strongest before the war, it experienced a rapid rise during the conflict from 1915-1918. This was largely due to the geographical features of the theater of operations, when the positions of the main enemy (Austria-Hungary) were separated from Italy by an insurmountable but relatively narrow barrier of the Adriatic.

Italy also became the first country after the Russian Empire to massively use multi-engine bombers in combat. The three-engined Caproni Ca.3, first flown in 1915, was one of the best bombers of the era, with more than 300 built and produced under license in the UK and USA.

During the war, the Italians also actively used airships for bombing operations. The weak protection of the strategic rear of the Central Powers contributed to the success of such raids. Unlike the Germans, the Italians relied on small high-altitude soft and semi-rigid airships, which were inferior to zeppelins in range and combat load. Since Austrian aviation, in general, was quite weak and, moreover, dispersed on two fronts, Italian aircraft were used until 1917.

United States Aviation

Because the United States remained aloof from the war for a long time, its air force developed comparatively more slowly. As a result, by the time the United States entered the world war in 1917, its air force was significantly inferior to the aviation of other participants in the conflict and approximately corresponded in technical level to the situation in 1915. Most of the available aircraft were reconnaissance or "general purpose" aircraft; there were no fighters or bombers capable of participating in air battles on the Western Front.

To solve the problem as quickly as possible, the US Army launched intensive production of licensed models from British, French and Italian companies. As a result, when the first American squadrons appeared at the front in 1918, they flew machines of European designers. The only airplanes designed in America that took part in the World War were twin-engine flying boats from Curtiss, which had excellent flight characteristics for their time and were intensively used in 1918 for anti-submarine patrols.

Introduction of new technologies

Vickers F.B.5. - the world's first fighter

In 1914, all countries of the world entered the war with airplanes without any weapons except for the personal weapons of the pilots (rifle or pistol). As aerial reconnaissance increasingly began to influence the course of combat operations on the ground, the need arose for weapons capable of preventing enemy attempts to penetrate airspace. It quickly became clear that fire from hand-held weapons was practically useless in air combat.

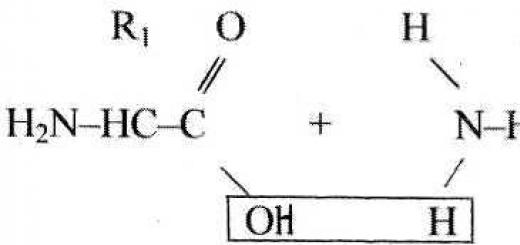

At the beginning of 1915, the British and French began to be the first to install machine gun weapons on aircraft. Since the propeller interfered with the shelling, machine guns were initially installed on vehicles with a pushing propeller located at the rear and not interfering with firing in the bow hemisphere. The world's first fighter was the British Vickers F.B.5, specially built for air combat with a turret-mounted machine gun. However, the design features of aircraft with a pusher propeller at that time did not allow them to develop sufficiently high speeds, and intercepting high-speed reconnaissance aircraft was difficult.

After some time, the French proposed a solution to the problem of shooting through the propeller: metal linings on the lower parts of the blades. Bullets hitting the pads were reflected without damaging the wooden propeller. This solution turned out to be nothing more than satisfactory: firstly, the ammunition was quickly wasted due to some of the bullets hitting the propeller blades, and secondly, the impacts of the bullets gradually deformed the propeller. Nevertheless, due to such temporary measures, Entente aviation managed to gain an advantage over the Central Powers for some time.

On November 3, 1914, Sergeant Garro invented the machine gun synchronizer. This innovation made it possible to fire through the aircraft's propeller: the mechanism allowed the machine gun to fire only when there was no blade in front of the muzzle. In April 1915, the effectiveness of this solution was demonstrated in practice, but by accident, an experimental aircraft with a synchronizer was forced to land behind the front line and was captured by the Germans. Having studied the mechanism, the Fokker company very quickly developed its own version, and in the summer of 1915 Germany sent to the front the first fighter of the “modern type” - the Fokker E.I, with a pulling propeller and a machine gun firing through the propeller disk.

The appearance of squadrons of German fighters in the summer of 1915 was a complete surprise for the Entente: all of its fighters had an outdated design and were inferior to Fokker aircraft. From the summer of 1915 to the spring of 1916, the Germans dominated the skies over the Western Front, securing a significant advantage for themselves. This position became known as the "Fokker Scourge"

Only in the summer of 1916, the Entente managed to restore the situation. The arrival at the front of maneuverable light biplanes of English and French designers, which were superior in maneuverability to the early Fokker fighters, made it possible to change the course of the war in the air in favor of the Entente. At first, the Entente experienced problems with synchronizers, so usually the machine guns of Entente fighters of that time were located above the propeller, in the upper biplane wing.

The Germans responded with the introduction of new biplane fighters, the Albatros D.II in August 1916, and the Albatros D.III in December, which had a streamlined semi-monocoque fuselage. Due to a more durable, lighter and streamlined fuselage, the Germans gave their aircraft better flight characteristics. This allowed them to once again gain a significant technical advantage, and April 1917 went down in history as “Bloody April”: Entente aviation again began to suffer heavy losses.

During April 1917, the British lost 245 aircraft, 211 pilots were killed or missing, and 108 were captured. The Germans lost only 60 airplanes in the battle. This clearly demonstrated the advantage of the semi-monococcal scheme over previously used ones.

The Entente's response, however, was swift and effective. By the summer of 1917, the introduction of the new Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5 fighters, the Sopwith Camel and SPAD, allowed the air war to return to normal. The main advantage of the Entente was the better state of the Anglo-French engine industry. In addition, since 1917, Germany began to experience a severe shortage of resources.

As a result, by 1918, Entente aviation had achieved both qualitative and quantitative superiority in the air over the Western Front. German aviation was no longer able to claim more than temporary local dominance on the front. In an attempt to change the situation, the Germans tried to develop new tactics (for example, during the summer offensive of 1918, air strikes on home airfields were first widely used in order to destroy enemy aircraft on the ground), but such measures could not change the overall unfavorable situation .

Tactics of air combat in the First World War

In the initial period of the war, when two aircraft collided, the battle was fought with personal weapons or with the help of a ram. The ram was first used on September 8, 1914 by the Russian ace Nesterov. As a result, both planes fell to the ground. In March 1915, another Russian pilot used a ram for the first time without crashing his own plane and returned to base. This tactic was used due to the lack of machine gun weapons and their low effectiveness. The ram required exceptional precision and composure from the pilot, so it was rarely used.

In the battles of the late period of the war, aviators tried to bypass the enemy plane from the side, and, going into the enemy’s tail, shoot him with a machine gun. This tactic was also used in group battles, with the pilot who showed the initiative winning; causing the enemy to fly away. The style of air combat with active maneuvering and close-range shooting was called “dogfight” and dominated the idea of air warfare until the 1930s.

A special element of the air combat of the First World War were attacks on airships. Airships (especially of rigid construction) had quite numerous defensive weapons in the form of turret-mounted machine guns, at the beginning of the war they were practically not inferior to airplanes in speed, and usually had a significantly superior rate of climb. Before the advent of incendiary bullets, conventional machine guns had very little effect on the airship's shell, and the only way to shoot down an airship was to fly directly over it and drop hand grenades on the ship's keel. Several airships were shot down, but in general, in air battles of 1914-1915, airships usually emerged victorious from encounters with aircraft.

The situation changed in 1915, with the advent of incendiary bullets. Incendiary bullets made it possible to ignite the hydrogen mixed with the air, flowing through the holes pierced by the bullets, and cause the destruction of the entire airship.

Bombing tactics

At the beginning of the war, not a single country had specialized aerial bombs in service. German Zeppelins carried out their first bombing missions in 1914, using conventional artillery shells with attached fabric surfaces, and the planes dropped hand grenades on enemy positions. Later, special aerial bombs were developed. During the war, bombs weighing from 10 to 100 kg were most actively used. The heaviest aerial munitions used during the war were first the 300-kilogram German aerial bomb (dropped from Zeppelins), the 410-kilogram Russian aerial bomb (used by Ilya Muromets bombers) and the 1,000-kilogram aerial bomb used in 1918 on London from German aerial bombs. multi-engine Zeppelin-Staaken bombers

Devices for bombing at the beginning of the war were very primitive: bombs were dropped manually based on the results of visual observation. Improvements in anti-aircraft artillery and the resulting need to increase bombing altitude and speed led to the development of telescopic bomb sights and electric bomb racks.

In addition to aerial bombs, other types of aerial weapons were developed. Thus, throughout the war, airplanes successfully used throwing flechettes, dropped on enemy infantry and cavalry. In 1915, the British Navy successfully used seaplane-launched torpedoes for the first time during the Dardanelles Operation. At the end of the war, the first work began on the creation of guided and gliding bombs.

Anti-aviation

Sound surveillance equipment from the First World War

After the start of the war, anti-aircraft guns and machine guns began to appear. At first they were mountain cannons with an increased barrel elevation angle, then, as the threat grew, special anti-aircraft guns were developed that could send a projectile to a greater height. Both stationary and mobile batteries appeared, on a car or cavalry base, and even anti-aircraft units of scooters. Anti-aircraft searchlights were actively used for night anti-aircraft shooting.

Early warning of an air attack became especially important. The time it took for interceptor aircraft to rise to high altitudes during World War I was significant. To provide warning of the appearance of bombers, chains of forward detection posts began to be created, capable of detecting enemy aircraft at a considerable distance from their target. Towards the end of the war, experiments began with sonar, detecting aircraft by the noise of their engines.

The air defense of the Entente received the greatest development in the First World War, forced to fight German raids on its strategic rear. By 1918, the air defenses of central France and Great Britain contained dozens of anti-aircraft guns and fighters, and a complex network of sonar and forward detection posts connected by telephone wires. However, it was not possible to ensure complete protection of the rear from air attacks: even in 1918, German bombers carried out raids on London and Paris. The First World War's experience with air defense was summed up in 1932 by Stanley Baldwin in the phrase "The bomber will always get through."

The air defense of the rear of the Central Powers, which had not been subjected to significant strategic bombing, was much less developed and by 1918 was essentially in its infancy.

Notes

Links

see also

| World War I | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

Looking at these photos, there is only bewilderment and admiration - how did they manage not just to fly, but to conduct air battles on these structures made of planks and rags?!

On April 1, 1915, at the height of the First World War, a French plane appeared over the German camp and dropped a huge bomb. The soldiers rushed in all directions, but there was no explosion. Instead of a bomb, a large ball landed with the inscription “Happy April Fools!”

It is known that over four years, the warring states carried out about one hundred thousand air battles, during which 8,073 aircraft were shot down and 2,347 aircraft were destroyed by fire from the ground. German bomber aircraft dropped over 27,000 tons of bombs on the enemy, British and French - more than 24,000.

The British claim 8,100 enemy aircraft shot down. The French - by 7000. The Germans admit the loss of 3000 of their aircraft. Austria-Hungary and other allies of Germany lost no more than 500 vehicles. Thus, the reliability coefficient of Entente victories does not exceed 0.25.

In total, the Entente aces shot down over 2,000 German aircraft. The Germans admitted that they lost 2,138 aircraft in air battles and that about 1,000 aircraft did not return from enemy positions.

So who was the most successful pilot of the First World War? A careful analysis of documents and literature on the use of fighter aircraft in 1914-1918 shows that it is the French pilot Rene Paul Fonck with 75 aerial victories.

Well, then what about Manfred von Richthofen, to whom some researchers attribute almost 80 destroyed enemy aircraft and consider him the most effective ace of the First World War?

However, some other researchers believe that there is every reason to believe that Richthofen’s 20 victories are not reliable. So this question still remains open.

Richthofen did not consider French pilots to be pilots at all. Richthofen describes the air battles in the East in a completely different way: “We flew often, rarely entered into battle and did not have much success.”

Based on the diary of M. von Richthofen, we can conclude that Russian aviators were not bad pilots, there were simply fewer of them compared to the number of French and English pilots on the Western Front.

Rarely on the Eastern Front did so-called “dog fights” take place, i.e. "dog dump" (maneuverable dogfights involving large numbers of aircraft) that were common on the Western Front.

In winter, planes did not fly in Russia at all. That is why all the German aces won so many victories on the Western Front, where the sky was simply teeming with enemy aircraft.

The air defense of the Entente received the greatest development in the First World War, forced to fight German raids on its strategic rear.

By 1918, the air defenses of central France and Great Britain contained dozens of anti-aircraft guns and fighters, and a complex network of sonar and forward detection posts connected by telephone wires.

However, it was not possible to ensure complete protection of the rear from air attacks: even in 1918, German bombers carried out raids on London and Paris. The First World War's experience with air defense was summed up in 1932 by Stanley Baldwin in the phrase "the bomber will always find a way."

In 1914, Japan, allied with Britain and France, attacked German troops in China. The campaign began on September 4 and ended on November 6 and marked the first use of aircraft on the battlefield in Japanese history.

At that time, the Japanese army had two Nieuport monoplanes, four Farmans and eight pilots for these machines. Initially they were limited to reconnaissance flights, but then manually dropped bombs began to be widely used.

The most famous action was the joint attack on the German fleet in Tsingtao. Although the main target - the German cruiser - was not hit, the torpedo boat was sunk.

Interestingly, during the raid, the first air battle in the history of Japanese aviation took place. A German pilot took off on Taub to intercept Japanese planes. Although the battle ended inconclusively, the German pilot was forced to make an emergency landing in China, where he himself burned the plane so that the Chinese would not get it. In total, during the short campaign, the Japanese Army's Nieuports and Farmans flew 86 combat missions, dropping 44 bombs.

Infantry aircraft in battle.

By the fall of 1916, the Germans had developed requirements for an armored “infantry aircraft” (Infantrieflugzeug). The emergence of this specification was directly related to the emergence of assault group tactics.

The commander of the infantry division or corps to which the Fl squadrons were subordinate. Abt first of all needed to know where its units that had infiltrated beyond the trench line were currently located and quickly transmit orders.

The next task is to identify enemy units that reconnaissance could not detect before the offensive. In addition, if necessary, the aircraft could be used as an artillery fire spotter. Well, during the execution of the mission it was envisaged to strike manpower and equipment with the help of light bombs and machine-gun fire, at least so as not to be shot down.

Orders for devices of this class were immediately received by three companies Allgemeine Elektrizitats Gesellschaft (A.E.G), Albatros Werke and Junkers Flugzeug-Werke AG. Of these aircraft designated J, only the Junkers aircraft was a completely original design; the other two were armored versions of reconnaissance bombers.

This is how German pilots described the assault actions of infantry Albatross from Fl.Abt (A) 253 - First, the observer dropped small gas bombs, which forced the British infantrymen to leave their shelters, then in the second pass, at an altitude of no more than 50 meters, fired at them from two machine guns installed in the floor of his cabin.

Around the same time, infantry aircraft began to enter service with attack squadrons - Schlasta. The main weapons of these units were multi-role two-seat fighters, such as the Halberstadt CL.II/V and Hannover CL.II/III/V; the “infantry” were a kind of appendage to them. By the way, the composition of the reconnaissance units was also heterogeneous, so in Fl. Abt (A) 224, in addition to Albatros and Junkers J.1 there were Roland C.IV.

In addition to machine guns, infantry aircraft were equipped with 20-mm Becker cannons that appeared towards the end of the war (on a modified AEG J.II turret and on a special bracket on the left side of the gunner’s cockpit of the Albatros J.I).

The French squadron VB 103 had a red five-pointed star emblem 1915-1917.

Russian aces of the First World War

Lieutenant I.V.Smirnov Lieutenant M.Safonov - 1918

Nesterov Petr Nikolaevich

Continuing the theme of the First World War, today I will talk about the origins of Russian military aviation.

How beautiful the current Su, MiG, Yaks are... What they do in the air is difficult to describe in words. This must be seen and admired. And in a good way envy those who are closer to the sky, and with the sky on first name terms...

And then remember where it all began: about “flying bookcases” and “plywood over Paris”, and pay tribute to the memory and respect of the first Russian aviators...

During the First World War (1914 - 1918), a new branch of the military - aviation - arose and began to develop with exceptional speed, expanding the scope of its combat use. During these years, aviation stood out as a branch of the military and received universal recognition as an effective means of fighting the enemy. In the new conditions of war, military successes of troops were no longer conceivable without the widespread use of aviation.

By the beginning of the war, Russian aviation consisted of 6 aviation companies and 39 aviation detachments with a total number of 224 aircraft. The speed of the aircraft was about 100 km/h.

It is known that tsarist Russia was not completely ready for war. Even the “Short Course on the History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)” states:

“Tsarist Russia entered the war unprepared. Russian industry lagged far behind other capitalist countries. It was dominated by old factories and factories with worn-out equipment. Agriculture, in the presence of semi-serf landownership and a mass of impoverished, ruined peasantry, could not serve as a solid economic basis for waging a long war.”

Tsarist Russia did not have an aviation industry that could provide the production of aircraft and engines in the quantities necessary for the quantitative and qualitative growth of aviation caused by the growing needs of wartime. Aviation enterprises, many of which were semi-handicraft workshops with extremely low productivity, were engaged in assembling aircraft and engines - this was the production base of Russian aviation at the beginning of hostilities.

The activities of Russian scientists had a huge impact on the development of world science, but the tsarist government was dismissive of their work. Tsarist officials did not give way to the brilliant discoveries and inventions of Russian scientists and prevented their mass use and implementation. But, despite this, Russian scientists and designers persistently worked to create new machines and developed the foundations of aviation science. Before the First World War, as well as during it, Russian designers created many new, completely original aircraft, in many cases superior in quality to foreign aircraft.

Along with building airplanes, Russian inventors successfully worked on creating a number of remarkable aircraft engines. Particularly interesting and valuable aircraft engines were built during that period by A. G. Ufimtsev, called by A. M. Gorky “a poet in the field of scientific technology.” In 1909, Ufimtsev built a four-cylinder birotative engine that weighed 40 kilograms and operated on a two-stroke cycle. Acting like a conventional rotary engine (only the cylinders rotated), it developed power of up to 43 hp. With. With birotation action (simultaneous rotation of the cylinders and shaft in opposite directions), the power reached 80 hp. With.

In 1910, Ufimtsev built a six-cylinder birotative aircraft engine with an electric ignition system, which was awarded a large silver medal at the international aeronautics exhibition in Moscow. Since 1911, engineer F. G. Kalep successfully worked on the construction of aircraft engines. Its engines were superior to the then widespread French Gnome engine in power, efficiency, operational reliability and durability.

In the pre-war years, Russian inventors also achieved major achievements in the field of flight safety. In all countries, aircraft accidents and disasters were then a frequent occurrence, but attempts by Western European inventors to make flights safer and create an aviation parachute were unsuccessful. The Russian inventor Gleb Evgenievich Kotelnikov managed to solve this problem. In 1911, he created the RK-1 backpack aviation parachute. Kotelnikov's parachute with a convenient suspension system and a reliable opening device ensured flight safety.

In connection with the growth of military aviation, the question arose of training personnel and, first of all, pilots. In the first period, flight enthusiasts flew airplanes, then, as aviation technology developed, special training was required for flights. Therefore, in 1910, after the successful holding of the “first aviation week,” an aviation department was created at the Officers’ Aeronautical School. For the first time in Russia, the aviation department of the aeronautical school began to train military pilots. However, its capabilities were very limited - initially it was planned to train only 10 pilots per year.

In the fall of 1910, the Sevastopol Aviation School was organized, which was the main educational institution in the country for training military pilots. From the first days of its existence, the school had 10 aircraft, which allowed it to train 29 pilots already in 1911. It should be noted that this school was created through the efforts of the Russian public. The level of training of Russian military pilots was quite high for that time. Before starting practical flight training, Russian pilots took special theoretical courses, studied the basics of aerodynamics and aviation technology, meteorology and other disciplines. The best scientists and specialists were involved in delivering lectures. Pilots from Western European countries did not receive such theoretical training; they were only taught to fly the aircraft.

Due to the increase in the number of aviation units in 1913 - 1914. it was necessary to train new flight personnel. The Sevastopol and Gatchina military aviation schools that existed at that time could not fully satisfy the army’s needs for aviation personnel. The aviation units experienced great difficulties due to the lack of aircraft. According to the property list that existed at that time, corps air squads were supposed to have 6 aircraft, and serfs - 8 aircraft. In addition, in case of war, each air squad was supposed to be equipped with a spare set of aircraft. However, due to the low productivity of Russian aircraft manufacturing enterprises and the lack of a number of necessary materials, the aviation detachments did not have a second set of aircraft. This led to the fact that by the beginning of the war, Russia did not have any aircraft reserves, and some of the aircraft in the detachments were already worn out and required replacement.

Russian designers have the honor of creating the world's first multi-engine airships - the first-born of heavy bomber aircraft. While the construction of multi-engine heavy-duty aircraft intended for long-distance flights was considered impracticable abroad, Russian designers created such aircraft as the Grand, Russian Knight, Ilya Muromets, and Svyatogor. The emergence of heavy multi-engine aircraft opened up new possibilities for the use of aviation. The increase in carrying capacity, range and altitude increased the importance of aviation as air transport and a powerful military weapon.

The distinctive features of Russian scientific thought are creative daring, a tireless striving forward, which led to new remarkable discoveries. In Russia, the idea of creating a fighter aircraft designed to destroy enemy aircraft was born and implemented. The world's first fighter aircraft, RBVZ-16, was built in Russia in January 1915 at the Russian-Baltic Plant, which previously built the heavy airship Ilya Muromets designed by I. I. Sikorsky. At the suggestion of famous Russian pilots A.V. Pankratyev, G.V. Alekhnovich and others, a group of plant designers created a special fighter aircraft to accompany the Muromites during combat flights and protect bomber bases from enemy air attacks. The RBVZ-16 aircraft was armed with a synchronized machine gun that fired through the propeller. In September 1915, the plant began serial production of fighters. At this time, Andrei Tupolev, Nikolai Polikarpov and many other designers who later created Soviet aviation received their first design experience at the Sikorsky company.

At the beginning of 1916, the new RBVZ-17 fighter was successfully tested. In the spring of 1916, a group of designers at the Russian-Baltic Plant produced a new fighter of the “Two-Tail” type. One of the documents from that time reports: “The construction of the “Dvukhvostka” type fighter has been completed. This device, previously tested in flight, is also sent to Pskov, where it will also be tested in detail and comprehensively.” At the end of 1916, the RBVZ-20 fighter of a domestic design appeared, which had high maneuverability and developed a maximum horizontal speed at the ground of 190 km/h. Also known are the experimental Lebed fighters, produced in 1915 - 1916.

Even before the war and during the war, designer D.P. Grigorovich created a series of flying boats - naval reconnaissance aircraft, fighters and bombers, thereby laying the foundations for seaplane construction. At that time, no other country had seaplanes equal in flight and tactical performance to Grigorovich’s flying boats.

Having created the heavy multi-engine aircraft "Ilya Muromets", the designers continue to improve the flight and tactical data of the airship, developing its new modifications. Russian designers also worked successfully on the creation of aeronautical instruments, devices and sights that helped carry out targeted bombing from aircraft, as well as on the shape and quality of aircraft bombs, which showed remarkable combat properties for that time.

Russian scientists working in the field of aviation, headed by N. E. Zhukovsky, through their activities provided enormous assistance to the young Russian aviation during the First World War. In the laboratories and circles founded by N. E. Zhukovsky, scientific work was carried out aimed at improving the flight and tactical qualities of aircraft, solving issues of aerodynamics and structural strength. Zhukovsky's instructions and advice helped aviators and designers create new types of aircraft. New aircraft designs were tested in the design and testing bureau, whose activities took place under the direct supervision of N. E. Zhukovsky. This bureau united the best scientific forces of Russia working in the field of aviation. N. E. Zhukovsky’s classic works on the vortex theory of the propeller, aircraft dynamics, aerodynamic calculation of aircraft, bombing, etc., written during the First World War, were a valuable contribution to science.

Despite the fact that domestic designers created aircraft that were superior in quality to foreign ones, the tsarist government and the heads of the military department disdained the work of Russian designers and prevented the development, mass production and use of domestic aircraft in military aviation.

Thus, the Ilya Muromets aircraft, which, according to flight-tactical data, could not be equaled by any aircraft in the world at that time, had to overcome many different obstacles before they became part of the combat ranks of Russian aviation. “Chief of Aviation” Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich proposed to stop the production of Muromtsev, and use the money allocated for their construction to purchase airplanes abroad. Through the efforts of high-ranking officials and foreign spies who made their way into the military ministry of tsarist Russia, the execution of the order for the production of Muromets was suspended in the first months of the war, and only under the pressure of indisputable facts testifying to the high combat qualities of the airships that had already participated in the hostilities, The Ministry of War was forced to agree to the resumption of production of the Ilya Muromets aircraft.

But in the conditions of tsarist Russia, building an aircraft, even one that clearly surpassed existing aircraft in its qualities, did not at all mean opening the way for it to fly. When the plane was ready, the bureaucratic machine of the tsarist government came into action. The plane began to be inspected by numerous commissions, the composition of which was replete with the names of foreigners who were in the service of the tsarist government and often carried out espionage work in the interests of foreign states. The slightest design flaw, which could easily be eliminated, caused a malicious howl that the plane was supposedly no good at all, and the talented proposal was put under a bushel. And after some time, somewhere abroad, in England, America or France, the same design, stolen by spy officials, appeared under the name of some foreign false author. Foreigners, using the help of the tsarist government, shamelessly robbed the Russian people and Russian science.

The following fact is very indicative. The M-9 seaplane, designed by D. P. Grigorovich, was distinguished by very high combat qualities. The governments of England and France, after a number of unsuccessful attempts to create their own seaplanes, in 1917 turned to the bourgeois provisional government with a request to transfer them the drawings of the M-9 seaplane. The provisional government, obedient to the will of the English and French capitalists, willingly betrayed the national interests of the Russian people: the drawings were placed at the disposal of foreign states, and according to these drawings of the Russian designer, aircraft factories in England, France, Italy, and America built seaplanes for a long time.

The economic backwardness of the country, the lack of an aviation industry, and dependence on supplies of aircraft and engines from abroad in the first year of the war put Russian aviation in an extremely difficult situation. Before the war, at the beginning of 1914, the War Ministry placed orders for the construction of 400 aircraft at a few Russian aircraft factories. The tsarist government expected to obtain most of the aircraft, engines and necessary materials abroad, having concluded appropriate agreements with the French military department and industrialists. However, as soon as the war began, the tsarist government’s hopes for help from the “allies” burst. Some of the purchased materials and engines were confiscated by Germany at routes to the Russian border, and most of the materials and engines provided for by the agreement were not sent by the “allies” at all. As a result, of the 400 aircraft that were eagerly awaited in the aviation units, which experienced an acute shortage of material, by October 1914 it turned out to be possible to continue the construction of only 242 aircraft .

In December 1914, the “allies” announced their decisions to sharply reduce the number of aircraft and engines supplied to Russia. The news of this decision caused extreme alarm in the Russian Ministry of War: the plan to supply aircraft and engines to units of the active army was disrupted. “The new decision of the French military department puts us in a difficult situation,” wrote the head of the main military-technical department to the Russian military agent in France . Of the 586 aircraft and 1,730 engines ordered in France in 1915, only 250 aircraft and 268 engines were delivered to Russia. Moreover, France and England sold obsolete and worn-out aircraft and engines to Russia, which had already been withdrawn from service in the French aviation. There are many cases where French identification marks were discovered under the fresh paint that covered the sent aircraft.

In a special certificate “On the condition of engines and airplanes received from abroad,” the Russian military department noted that “official acts testifying to the condition of engines and airplanes arriving from abroad show that in a significant number of cases these items arrive in faulty form... Foreign factories send already used devices and engines to Russia.” Thus, the plans of the tsarist government to receive material from the “allies” to supply aviation failed. And the war demanded more and more new aircraft, engines, and aviation weapons.

Therefore, the main burden of supplying aviation with materiel fell on the shoulders of Russian aircraft factories, which, due to their small numbers, acute lack of qualified personnel, and lack of materials, were clearly unable to satisfy all the growing needs of the front for aircraft. and motors. During the First World War, the Russian army received only 3,100 aircraft, of which 2,250 were from Russian aircraft factories and about 900 from abroad.

The acute shortage of engines was especially detrimental to the development of aviation. The military department's leaders' focus on importing engines from abroad led to the fact that, at the height of hostilities, there were no engines available for a significant number of aircraft built in Russian factories. Airplanes were sent to the active army without engines. It got to the point that in some aviation detachments, for 5-6 aircraft there were only 2 serviceable engines, which had to be removed from some aircraft and transferred to others before combat missions. The tsarist government and its military department were forced to admit that dependence on foreign countries put Russian aircraft factories in an extremely difficult situation. Thus, the head of the organization of aviation in the active army wrote in one of his memos: “The lack of engines had a disastrous effect on the productivity of airplane factories, since the calculation of domestic airplane production was based on the timely supply of foreign engines.”

The enslaving dependence of the economy of Tsarist Russia on foreign countries brought Russian aviation to disaster during the First World War. It should be noted that the Russian-Baltic Plant successfully mastered the production of domestic Rusbalt engines, with which most of the Ilya Muromets airships were equipped. However, the tsarist government continued to order worthless Sunbeam engines from England, which continually failed to fly. The poor quality of these engines is eloquently evidenced by an excerpt from a memorandum from the department of the general on duty under the Commander-in-Chief: “The 12 new Sunbeam engines that had just arrived in the squadron turned out to be faulty; there are defects such as cracks in the cylinders and misalignments of the connecting rods.”

The war required continuous improvement of aviation equipment. However, the owners of aircraft factories, trying to sell already manufactured products, were reluctant to accept new aircraft and engines for production. It is appropriate to mention this fact. The Gnome plant in Moscow, owned by a French joint-stock company, produced obsolete Gnome aircraft engines. The Main Military-Technical Directorate of the War Ministry proposed that the plant's management move to the production of a more advanced rotary motor "Ron". The plant's management refused to comply with this requirement and continued to impose its outdated products on the military department. It turned out that the director of the plant received a secret order from the board of a joint stock company in Paris - to slow down the construction of new engines by any means in order to be able to sell the parts prepared in large quantities for the outdated design engines produced by the plant.

As a result of Russia's backwardness and its dependence on foreign countries, Russian aviation during the war fell catastrophically behind in terms of the number of aircraft from other warring countries. An insufficient amount of aviation equipment was a characteristic phenomenon for Russian aviation throughout the war. The lack of aircraft and engines disrupted the formation of new aviation units. On October 10, 1914, the main directorate of the main headquarters of the Russian army reported on a request about the possibility of organizing new aviation detachments: “... it has been established that aircraft cannot be built for new detachments before November or December, since all those currently being manufactured are being replenished significant loss of apparatus in existing detachments" .

Many aviation detachments were forced to conduct combat work on outdated, worn-out aircraft, since the supply of new brands of aircraft had not been established. One of the reports of the Commander-in-Chief of the armies of the Western Front, dated January 12, 1917, states: “Currently, the front consists of 14 aviation detachments with 100 aircraft, but of these, only 18 are serviceable devices of modern systems.” (By February 1917, on the Northern Front, out of the required 118 aircraft, there were only 60 aircraft, and a significant part of them were so worn out that they required replacement. The normal organization of combat operations of aviation units was greatly hampered by the diversity of aircraft. There were many aviation detachments, where all available The aircraft had different systems, which caused serious difficulties in their combat use, repair and supply of spare parts.

It is known that many Russian pilots, including P.N. Nesterov, persistently sought permission to arm their aircraft with machine guns. The leaders of the tsarist army refused them this and, on the contrary, slavishly copied what was being done in other countries, and treated everything new and advanced that was created by the best people of Russian aviation with distrust and disdain.

During the First World War, Russian aviators fought in the most difficult conditions. An acute lack of material, flight and technical personnel, the stupidity and inertia of the tsarist generals and dignitaries, into whose care the air force was entrusted, delayed the development of Russian aviation, narrowed the scope and reduced the results of its combat use. And yet, in these most difficult conditions, advanced Russian aviators showed themselves to be bold innovators, decisively paving new paths in the theory and combat practice of aviation.

During the First World War, Russian pilots accomplished many glorious deeds that went down in the history of aviation as a clear evidence of valor, courage, inquisitive mind and high military skill of the great Russian people. At the beginning of the First World War, P.N. Nesterov, an outstanding Russian pilot, the founder of aerobatics, accomplished his heroic feat. On August 26, 1914, Pyotr Nikolaevich Nesterov conducted the first air battle in the history of aviation, realizing his idea of using an aircraft to destroy an air enemy.

Advanced Russian aviators, continuing the work of Nesterov, created fighter squads and laid the initial foundations of their tactics. Special aviation detachments, whose goal was to destroy enemy air forces, were first formed in Russia. The project for organizing these detachments was developed by E. N. Kruten and other advanced Russian pilots. The first fighter aviation units in the Russian army were formed in 1915. In the spring of 1916, fighter aviation detachments were formed in all armies, and in August of the same year, front-line fighter aviation groups were created in Russian aviation. This group included several fighter aviation squads.

With the organization of fighter groups, it became possible to concentrate fighter aircraft on the most important sectors of the front. The aviation manuals of those years stated that the goal of fighting enemy aviation “is to ensure your air fleet freedom of action in the air and constrain the enemy. This goal can be achieved by incessantly pursuing enemy aircraft for their destruction in air combat, which is the main task of fighter squads.” . The fighter pilots skillfully beat the enemy, increasing the number of enemy aircraft shot down. There are many known cases when Russian pilots entered into an air battle alone against three or four enemy aircraft and emerged victorious from these unequal battles.

Having experienced the high combat skill and courage of Russian fighters, German pilots tried to avoid air combat. One of the reports from the 4th Combat Fighter Aviation Group stated: “It has been noticed that recently German pilots, flying over their territory, are waiting for the passage of our patrol vehicles and, when they pass, they are trying to penetrate our territory. When our planes approach, they quickly retreat to their location.”.

During the war, Russian pilots persistently developed new air combat techniques, successfully applying them in their combat practice. In this regard, the activity of the talented fighter pilot E. N. Kruten, who enjoyed a well-deserved reputation as a brave and skillful warrior, deserves attention. Just over the location of his troops, Kruten shot down 6 planes in a short period of time; He also shot down quite a few enemy pilots while flying behind the front line. Based on the combat experience of the best Russian fighter pilots, Kruten substantiated and developed the idea of paired formation of fighter combat formations, and developed a variety of air combat techniques. Kruten has repeatedly emphasized that the components of success in air combat are surprise of attack, altitude, speed, maneuver, caution of the pilot, opening fire from extremely close range, persistence, and the desire to destroy the enemy at all costs.

In Russian aviation, for the first time in the history of the air fleet, a special formation of heavy bombers arose - the Ilya Muromets squadron of airships. The tasks of the squadron were defined as follows: through bombing, destroy fortifications, structures, railway lines, hit reserves and convoys, operate on enemy airfields, carry out aerial reconnaissance and photograph enemy positions and fortifications. The squadron of airships, actively participating in the hostilities, inflicted considerable damage on the enemy with their well-aimed bomb attacks. The pilots and artillery officers of the squadron created instruments and sights that significantly increased the accuracy of bombing. The report, dated June 16, 1916, stated: “Thanks to these devices, now during the combat work of ships there is complete opportunity to accurately bomb the intended targets, approaching them from any direction, regardless of the direction of the wind, and this makes it difficult to target ships enemy anti-aircraft guns."

The inventor of the wind gauge - a device that allows one to determine the basic data for targeted dropping of bombs and aeronautical calculations - was A. N. Zhuravchenko, now a Stalin Prize laureate, an honored worker of science and technology, who served in an airship squadron during the First World War. Leading Russian aviators A.V. Pankratiev, G.V. Alekhnovich, A.N. Zhuravchenko and others, based on the experience of the squadron’s combat operations, developed and generalized the basic principles of targeted bombing, actively participated with their advice and proposals in the creation of new modified aircraft ships "Ilya Muromets".

In the fall of 1915, the pilots of the squadron began to successfully conduct group raids on important enemy military targets. Very successful raids by the Muromites on the cities of Towerkaln and Friedrichshof are known, as a result of which enemy military warehouses were hit with bombs. Enemy soldiers captured some time after the Russian air raid on Towerkaln showed that bombs had destroyed warehouses with ammunition and food. On October 6, 1915, three airships made a group raid on the Mitava railway station and blew up fuel warehouses.

Russian planes successfully operated in groups and alone at railway stations, destroying tracks and station structures, hitting German military echelons with bombs and machine-gun fire. Providing great assistance to ground troops, the airships systematically attacked the enemy’s fortifications and reserves and hit his artillery batteries with bombs and machine-gun fire.

The squadron pilots flew on combat missions not only during the day, but also at night. Night flights of the Muromets caused great damage to the enemy. During night flights, aircraft navigation was carried out using instruments. The aerial reconnaissance conducted by the squadron provided great assistance to the Russian troops. The order for the Russian 7th Army noted that “during aerial reconnaissance, the Ilya Muromets 11 airship photographed enemy positions under extremely heavy artillery fire. Despite this, the work of that day was successfully completed, and the next day the ship again took off on an urgent task and performed it perfectly. As during the entire time that the airship “Ilya Muromets” 11 was in the army, the photography on both of these flights was excellent, the reports were compiled very thoroughly and contain truly valuable data.” .

The Muromets inflicted significant losses on enemy aircraft, destroying aircraft both at airfields and in air battles. In August 1916, one of the squadron's combat detachments successfully carried out several group raids on an enemy seaplane base in the area of Lake Angern. Airship crews have achieved great skill in repelling fighter attacks. The high combat skill of the aviators and the powerful small arms of the aircraft made the Muromets low-vulnerable in air combat.

In battles during the First World War, Russian pilots developed the initial tactics for defending a bomber from attack by fighters. So, during group flights when attacked by enemy fighters, the bombers took over the formation with a ledge, which helped them support each other with fire. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the Russian airships Ilya Muromets, as a rule, emerged victorious from battles with enemy fighters. During the entire First World War, the enemy managed to shoot down only one aircraft of the Ilya Muromets type in an air battle, and that was because the crew ran out of ammunition.

Russian army aviation was also actively bombing enemy personnel, railway structures, airfields and artillery batteries. Thorough aerial reconnaissance carried out before the raids helped the pilots to timely and accurately bomb the enemy. Among many others, a successful night raid by planes of the Grenadier and 28th aviation detachments on the Tsitkemen railway station and the German airfield located near it is known. The raid was preceded by thorough reconnaissance. The pilots dropped 39 bombs on pre-designated targets. Accurately dropped bombs caused fires and destroyed hangars with enemy aircraft in them.

From the very first days of the war, Russian aviators showed themselves to be brave and skillful aerial reconnaissance officers. In 1914, during the East Prussian operation, pilots of the aviation detachments of the 2nd Russian Army, through thorough aerial reconnaissance, collected data on the location of the enemy in front of the front of our troops. Conducting intensive reconnaissance flights, the pilots relentlessly monitored the Germans retreating under the attacks of Russian troops, supplying headquarters with information about the enemy.

Aviation reconnaissance promptly warned the command of the 2nd Army about the threat of a counterattack, reporting that enemy troops were concentrating on the flanks of the army. But the mediocre tsarist generals did not take advantage of this information and did not attach any importance to it. Neglect of aerial intelligence was one of the many reasons why the offensive against East Prussia failed. Aerial reconnaissance played a significant role in preparing the August 1914 offensive of the armies of the Southwestern Front, as a result of which Russian troops defeated the Austro-Hungarian armies and occupied Lvov, Galich and the Przemysl fortress. Carrying out reconnaissance flights over enemy territory, the pilots systematically supplied headquarters with information about the enemy’s fortifications and defensive lines, about his groupings and escape routes. Air reconnaissance data helped determine the direction of attacks of the Russian armies on the enemy.

During the siege of the Przemysl fortress, on the initiative of advanced Russian pilots, photography of fortifications was used from the air. By the way, it should be said that here, too, the highest ranks of the tsarist army showed stupidity and inertia. Representatives of the high command of aviation were staunch opponents of aerial photography at the beginning of the war, believing that it could not bring any results and was a “worthless activity.” However, Russian pilots, who systematically carried out successful photographic reconnaissance, refuted this point of view of the dignitaries.

The Brest-Litovsk fortress and 24th aviation detachments, operating as part of the troops that took part in the siege of Przemysl, conducted intensive aerial photographic reconnaissance of the fortress. So, on November 18, 1914 alone, they took 14 photographs of the fortress and its forts. The report on the work of aviation in November 1914 indicates that as a result of reconnaissance flights accompanied by photography:

"1. A detailed survey of the south-eastern area of the fortress has been completed.

2. An engineering survey was carried out of the area facing Nizankovitsy, in view of information from the army headquarters that they were preparing for a sortie.

3. The places where our shells hit were determined by photographs of the snow cover, and some defects were identified in determining targets and distances.

4. The enemy’s reinforcement of the northwestern front of the fortress was clarified.” .

The 3rd point of this report is very interesting. Russian pilots cleverly used aerial photography of the places where our artillery shells exploded to correct its fire.

Aviation took an active part in the preparation and conduct of the June offensive of the troops of the Southwestern Front in 1916. Aviation detachments assigned to the front troops received certain sectors of the enemy's location for aerial reconnaissance. As a result, they photographed enemy positions and determined the locations of artillery batteries. Intelligence data, including airborne intelligence, helped to study the enemy’s defense system and develop an offensive plan, which, as we know, was crowned with significant success.

During the fighting, Russian aviators had to overcome enormous difficulties caused by the economic backwardness of Tsarist Russia, its dependence on foreign countries, and the hostile attitude of the Tsarist government towards the creative pursuits of talented Russian people. As already indicated, Russian aviation during the war lagged behind the air forces of its “allies” and enemies. By February 1917, there were 1,039 aircraft in Russian aviation, of which 590 were in the active army; a significant portion of the aircraft had outdated systems. Russian pilots had to compensate for the acute shortage of aircraft with intense combat work.

In a stubborn struggle against the routine and inertia of the ruling circles, advanced Russian people ensured the development of domestic aviation and made remarkable discoveries in various branches of aviation science. But how many talented inventions and undertakings were crushed by the tsarist regime, which stifled everything brave, smart, and progressive among the people! The economic backwardness of Tsarist Russia, its dependence on foreign capital, which resulted in a catastrophic lack of weapons in the Russian army, including a lack of aircraft and engines, the mediocrity and corruption of the Tsarist generals - these are the reasons for the serious defeats that the Russian army suffered during the First World War,

The further the First World War dragged on, the clearer the bankruptcy of the monarchy became. In the Russian army, as well as throughout the country, the movement against the war grew. The growth of revolutionary sentiment in the aviation units was greatly facilitated by the fact that the mechanics and soldiers of the aviation units were mostly factory workers drafted into the army during the war. Due to the lack of pilot personnel, the tsarist government was forced to open access to aviation schools to soldiers.

Soldier-pilots and mechanics became the revolutionary core of aviation detachments, where, as in the entire army, the Bolsheviks launched a great deal of propaganda work. The Bolsheviks' calls to turn the imperialist war into a civil war and to direct weapons against their own bourgeoisie and the tsarist government often met with a warm response among the aviator soldiers. In the aviation units, cases of revolutionary actions became more frequent. Among those sentenced to court-martial for revolutionary work in the army were many soldiers from aviation units.

The Bolshevik Party launched powerful propaganda work in the country and at the front. Throughout the army, including in the aviation units, the influence of the party grew every day. Many aviator soldiers openly declared their reluctance to fight for the interests of the bourgeoisie and demanded the transfer of power to the Soviets.

The Revolution and Civil War were ahead...

Business plan for a souvenir shop January 17, It is generally accepted that the souvenir business is one of the simplest types of small business. Individual local craftsmen, artists, potters, photographers, manufacturers of crafts and toys produce their products in small quantities and sell them personally or through small shops to tourists, children, lovers of exotic things and original gifts. In fact, this is an outdated idea, since the modern souvenir business is distinguished by the introduction of the latest technologies, fresh and unique design, the use of composite materials, innovative trading methods, including online trading, delivery and customer service. As the population’s prosperity grows, so does its interest in souvenirs, memorable gifts, attributes of local clothing, historical objects, personalities, etc. At the same time, different dynamics are observed in the adjacent segments of this vast market: There are also specifics by trade class - in the premium class , luxury, mass market, lower price segment. For Russian specifics, a good prerequisite for opening a souvenir store is a slight reduction in outbound tourism and the concentration of Russians on domestic recreation in its various manifestations - car travel, trips to cities and small towns of the country, sports tourism when large numbers of fans follow their team or athlete .

This service allows you to solve all three problems simultaneously, allowing you to attract visitors from different sources and any devices. New channels for attracting traffic are constantly emerging, and those entrepreneurs who are among the first to use them will be able to gain an absolute advantage over their competitors. Using this service will be especially useful for small businesses in the regions. In addition, this is also a way to receive feedback from the target audience, because users, for example, can express their opinions about the company through ratings and reviews. Here's what it looks like: The ability to maintain up-to-date information regarding the company's performance is equally important. We are talking about the address and opening hours, contact phone numbers, photos, etc.