As we all know, Orthodox Christianity treats icons with special reverence. Contemplating them, the one praying ascends to the prototype, that is, praying before the icon of the Holy Virgin, he looks at the Mother of God herself. Especially revered images are specially visited, their appearance is reproduced in hundreds of lists, in “measure and likeness”, as well as in a reduced format, so that those who cannot reach the shrine can see the icon. There are other reasons as well. For example, when the Mother of God of Vladimir ended up in Moscow, in the Assumption Cathedral, an exact copy was made of it and sent to Vladimir, so that the shrine would remain there, protecting its city. I'm oversimplifying a bit, but the bottom line is that icons are meant to be contemplated, and the most prominent ones are reproduced over and over again.

In this sense, the icon of Our Lady of Kykkos, one of the main shrines of Cyprus, is unique. Although anyone can “visit” it, no one can see the icon. It is covered with a frame that seems to repeat the image, and the frame is covered with a precious veil.

All revered icons since the Middle Ages have salaries and chasubles made of gold, silver and precious stones. Two salaries and a robe of Our Lady of Vladimir are exhibited in the Armory. The frames of the miraculous icons of Athos are still in situ, decorating the images. Some icons have different jewels for ordinary days and holidays. But no matter how magnificent and rich the salary is, it leaves visible faces (albeit repeatedly rewritten). The exception in this series is the Mother of God of Kykkos, because the faces of Mary and the Child are covered with a heavy velvet veil. Only the lower part of the chased salary is visible, which reproduces the contours of the figures. I want to emphasize once again that the icon that cannot be seen is a unique phenomenon. But how it happened, and what the image might look like - let's figure it out.

To begin with, a little history, or rather, legends. It is believed that the icon of Our Lady of Kykkos was painted by the Evangelist Luke, who was an artist by profession, during the life of the Virgin. Most of the ancient revered icons are attributed to Luke, including the Vladimir Mother of God, which actually dates from the ΧΙΙ century. So, Luke painted the icon of the Mother of God, later called Kykkos, for the Christians of Egypt. But in the era of iconoclasm (in the eighth - first half of the ninth century), the icon was sent to Byzantium in order to save it from destruction. This sounds a little strange, because Constantinople, in fact, was at that time the center of the persecution of images.

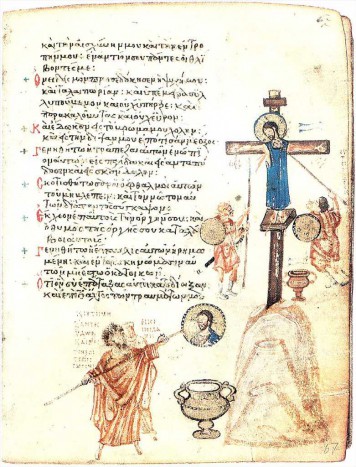

The iconoclast covers the icon of Christ with lime. Miniature of the Khludov Psalter. Around 850. Byzantium. Historical Museum (Moscow)

One way or another, the icon did not reach Constantinople, because on the way the ship was captured by pirates. The pirates were Saracens, that is, Arabs, and they were not interested in the icon: nothing saves cultural monuments like oblivion and indifference (by the way, they could destroy the icon, because Islam does not approve of the image of a person). One way or another, in 980 or so, these pirates were defeated by the Greeks, and the icon ended up in Constantinople, where at that time all iconoclastic heresy was defeated, Orthodoxy triumphed, and nothing threatened the work of Luke the Evangelist.

The next stage in the history of the image dates back to the end of the ΧΙ century, when the icon ended up in Cyprus. It was kept in the chambers of Emperor Alexei Komnenos (r. 1082–1118), to whom the Mother of God appeared in a dream and ordered the icon to be sent there. The then ruler of the island, Manuel Vutomit, asked Alexei about the same. The hermit Isaiah, who lived on the mountain where the Kykkos monastery now stands, was also warned in a vision about the arrival of the miraculous image. The legend says that the miraculous icon was so dear to Alexei that he could not come to terms with the idea that now anyone could take it and see it, and therefore ordered to close it from prying eyes. Jewels and relics have been hidden for all ages, and even in the East they still do this for some reason with living people.

However, Alexei Komnenos was not alone in his desire to hide the home shrine from prying eyes. My colleague Irina Sterligova once drew attention to sewn items, first mentioned in the inventory of Ivan the Terrible's personal property. These items were part of the attire of revered icons and were called "dungeons" or "wall sheets". They were veils of thin fabric, richly decorated with fragments, studded with pearls and precious stones, which were attached to the upper field of the icon so as to cover the sacred image. In the middle of these "dungeons" (probably from the word "zastit", that is, to close) "names of images", that is, the names of icons, were embroidered.

Icons with "dungeons" during some divine services and ceremonies were taken out of palace churches and royal chambers to cathedrals. These were very personal and deeply revered objects, and the "dungeons" hid them from vain or even heretical eyes, which could look at the shrine while it was being carried through Cathedral Square. Most likely, the custom of covering holy images was not invented in the Kremlin chambers, but was adopted from the Byzantines.

By the way, the miraculous icon of the Blachernae Mother of God in Constantinople was also hidden for most of the time by a veil that miraculously rose every week at the Friday evening service, revealing the face of the Mother of God to those praying. On Sunday the veil fell. This “ordinary miracle” (as the Byzantines called it) is associated with the feast of the Intercession of the Mother of God, but this is a separate issue. Later, the practice went to the people: in peasant houses, icons in the red corner were also curtained. But all this only points to the roots of the phenomenon of Our Lady of Kykkos: all these dungeons and curtains hid the image only from an undesirable public and at certain moments. It is important that the tsar, the grand duke and the emperor contemplated their home shrine, not to mention the multitude of people in the Blachernae church contemplating the “ordinary miracle” of the appearance of the icon. And only the Kikk Mother of God can not be seen by anyone. At all.

One way or another, the face of the icon is closed, and according to the monastery chronicles, the Queen of Heaven punishes the curious quite severely. For example, the Patriarch of Alexandria lifted the veil in 1669 and immediately became blind. True, his sight returned to him after he admitted that he was wrong and repented. We can assume that the image is closed for our own safety. The famous traveler Vasily Grigorovich-Barsky, who traveled the island of Cyprus far and wide in the 18th century, suspected that the face of the Mother of God could be seen by staying in the church for the night, and that it still opens when the dilapidated veil is changed on it, and this happens once a three to four years. Judging by the notes, the “pedestrian” still did not dare to spend the night in the temple, and the shroud did not need to be replaced during both of his visits. Your obedient servant also did not look under the cover. Under the salary there may be another one, or an imitation of a fabric curtain in silver. In general, the eyes are an important organ for an art critic, and respect for the traditions of the places you visit is the best safety technique.

The icon is taken out of the temple only on special occasions, with great honors, and at the same time they try not to look at it. This is done, for example, when it is necessary to bring rain during a drought, and the Lady always rescues the islanders.

The version about the jealousy of Alexei Komnenos for his home relic is legendary, and the presence of copies-lists of the icon that appear in the surrounding churches already in the ΧΙΙΙ century suggests that for some time the icon could still be seen. When did she close? Anyway, it happened quite a long time ago. There are several versions.

The very first option is after the fire of 1365. Then the whole monastery burned out, and the icon, according to sources, remained unharmed. In Russia, too, this often happened. For example, once, as a result of a fire in the Kremlin, one board remained from a revered icon, and the image burned down. The famous artist Dionysius, who remembered the original, primed the surviving board and repainted the image. I do not rule out that something similar happened here. The icon could be burned or smoky. For some reason they did not restore it, either there was no one, or they were afraid to spoil it. Maybe since then her face has been closed. Until that moment, the icon should have been available, which is evidenced by rather ancient lists, but about them later. Fires in the monastery also happened later, in particular, in 1542, 1751, 1813.

The second version of the date of hiding the icon is 1576. It was then that the icon received a luxurious setting (most likely not the first): silver, gilded, decorated with tortoise shells inlaid with mother-of-pearl. It has been preserved and seems to be on display, just mounted on another board. The modern salary dates back to the end of the ΧVIII century. It is with him that the last and latest date when the icon could be seen is connected - this is the last change of salary, 1795.

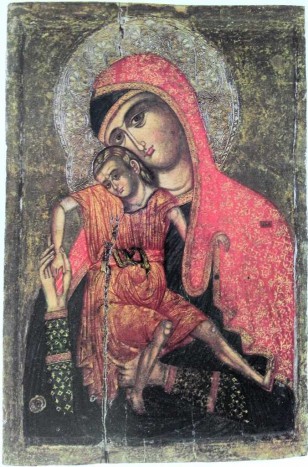

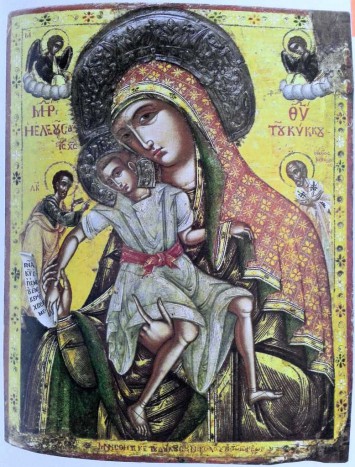

Now let's turn to the image itself, let's try to mentally reconstruct it. Judging by numerous lists, for example, this icon of the end of the 13th and first half of the 14th century from the monastery of St. John Lampadist, we see that this icon belongs to the type of Eleus, or in Russian Tenderness, that is, one where a mother caresses her son, grieving for his future suffering.

In addition, its type can be defined as Jumping, that is, the child jumps in the arms of the mother, and she tries to hold him. In this, theologians also see a reference to future passions, because, mourning her son, Mary said that earlier in childhood he jumped in her arms, and now lies dead. In a word, an ambivalent type, at the same time touching and tragic.

The complex pose of a baby escaping from the mother's arms is the first distinguishing feature of the image. On most lists, the baby sits to our left, although there are also mirror options. The second feature is an additional veil on the head of the Virgin Mary. By the way, such icons, with two covers, and quite ancient, are also known in Russia. This is the so-called Mother of God Tenderness Starorusskaya (from the name of the city of Staraya Russa)

Our Lady of Tenderness Old Russian. Beginning of the ΧΙΙΙ century. Russian Museum (St. Petersburg)

and simply Our Lady of Tenderness from the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin, both beginning of the 13th century.

True, this is where the similarity with Kikkskaya ends: the baby on both of these icons does not break out of the hands, but, on the contrary, hugs the mother. And he sits on the right, not on the left. The third characteristic (but optional) detail of the iconography of the Kykkos Mother of God is the outline of this very second veil, the edge of which the baby lifts with a handle. In Russia, this option appeared only in the Χ7th century. The first such image, signed in Greek "Kykkskaya", appeared in 1668. It was painted by the famous royal icon painter Simon Ushakov for the Church of St. Gregory of Neocaesarea in Moscow.

Our Lady of Kykkos. Simon Ushakov, 1668. Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow)

Then there was great interest in everything Greek, and this is connected with Patriarch Nikon, whom all the same Greek hierarchs later came to judge. The Ushakov icon very accurately reproduces everything that was discussed, even the inscriptions are all Greek (Russian translation is nearby), only the composition is a mirror image. Most likely, the master made a very accurate copy, removing it mechanically, and then forgot to turn the sheet over. It happens even with great masters. Then the icon of Ushakov was copied, and more than once. For example, the only signature work of the Rybinsk icon painter Leonty Tyumenev in 1693 is the Kikk Mother of God.

Our Lady of Kykkos. Leonty Tyumenev, 1693. Rybinsk Museum. Copy from Ushakov's icon

Before the work of Simon Ushakov, I know of only one icon that resembles the Kikk one: it depicts the Mother of God with an additional, red head veil, and also the Baby Leaping. It can be dated to the 16th century, the second half or even the end of the century.

True, she also “looks” in the wrong direction, and small details do not match. This means that they knew something about the Kikk icon in Russia at the end of the 16th century. It was no coincidence that I spoke about the relations between Russia and Cyprus in the Late Middle Ages, and we will return to them later.

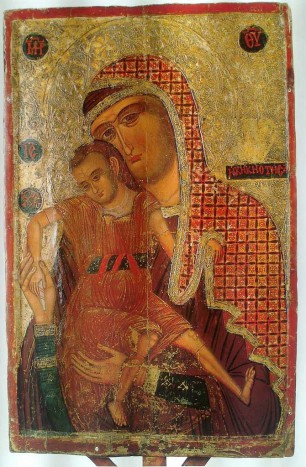

Actually in Cyprus there are copies of the XIII, XVI and XVIII centuries. There are many of them, and they come from villages located precisely in that part of the island where the mountain rises, on which the Kykksky monastery stands. And in the 16th century, and later, a stable type was preserved: the Mother of God Jumping. A second, additional veil is thrown over Mary's head, red, or almost black, meaning purple, woven with gold patterns. By the way, the name “Kykkskaya” has been found on icons since the 13th century.

It is written on the icon: ΚΗΚΟΤΗΣΑΑ. At the same time, some lists that exactly repeat the types described above are not signed at all as “Kikkotissa”. For example, an icon from the church of St. Marina in Kalopanayiotis is signed as "Athanasiotissa" (Αθανασιότησσα). The icon was published in a small resolution, and the face is poorly preserved, so I don’t give an image.

The icon of the 16th century, signed as "Kikkotissa", kept in the Byzantine Museum in Pedoulas, also retained the name of the artist. He, like the evangelist artist, was called Luke.

Our Lady of Kykkos. Cyprus, 16th century. Byzantine Museum in the village of Pedoulas

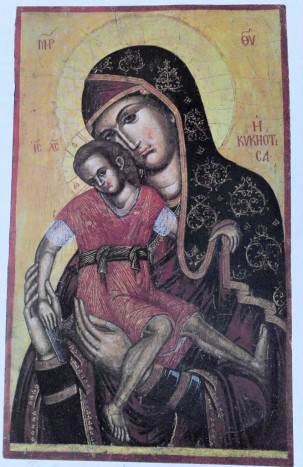

So, all the icons of Our Lady of Kykkos are very recognizable, thanks to the pose of the baby and the second maforium (cape). Sometimes, as on this 18th-century icon from the monastery of the Holy Mother of God Amasgu, the main image was supplemented.

Our Lady of Kykkos. Cyprus, 18th century. Monastery of the Holy Mother of God Amasgu in the village of Monagri

Angels were added on the sides of the face of the Mother of God, and below - Luke the Evangelist, the author of the original icon, and St. Nicholas, because he was the patron saint of the customer. This is stated in the inscription-prayer on the lower field of the icon, where the ktitor asks Christ not to neglect the servant of God Nicholas and his parents.

But still, what is depicted on the icon closed from the eyes? It would seem that everything fits. There, judging by these copies and the outlines of the figures on the salary of the original, there is a half-length image of the Virgin with a baby in her arms. But everything is not so simple.

In the funds of the State Public Library of St. Petersburg, in the Pogodin collection, there is a handwritten collection, and in it is the Tale of the Cyprus Island of the late 16th century. It is short, but it tells a lot about the history of the island in a slightly confused way. O.A., who published this source. Belobrova believes that this was recorded from the words of a local resident. We can talk about regular relations between Russia and Cyprus just from the end of the 16th century. Representatives of the island, mostly clerics, came to Muscovy and were invariably given help and a warm welcome. One of the patriarchs of the Time of Troubles, the Cretan Ignatius, according to him, occupied one of the chairs in Cyprus (although he did not say which one). Prior to this, there were only bizarre references to Cyprus in ancient Russian literature. For example, hegumen Daniel, who visited Constantinople and the Holy Land in the ΧΙΙ century, also visited Cyprus and wrote that there, in the Troodos mountains, “... incense, incense will be born: it falls from heaven, and it is collected on trees. After all, there are many low trees in those mountains, equal to grass, and that good incense will fall on them. Collect it in the month of July and August; in other months it does not fall; but only in those two will be born. Don't ask me what that means. Daniel does not say anything about the Kykksky monastery, only about the relic of the Tree of the Cross, which is located in the same part of the island, in the monastery of the Holy Cross (Τιμίος Σταυρός).

A description of this monastery is also in the Tale of the Cyprus Island, and there is also a description of a certain Assumption Monastery, where the miraculous icon of the Most Holy Theotokos is kept. True, according to the Tale, it is located closer to the city of Kyrinea (the northern part of the island), which does not correspond to the position of the Kykksky monastery, but the shrine resembles the Kykksky one, judge for yourself: in it in the church is the image of the Most Pure Mother of God with the eternal child on the throne, and the baby against her breasts, blesses with both hands, the letters of Luke the Evangelist. If the archbishop and people want to pray from the presence of foreigners, or ask for rain or buckets, and how they follow that image, they lift it to the cathedral and how they open the church, and that most pure image, having come out of this place, stands at the door in the air, and on the whole face of her empress sweat; by that they recognize the grateful. The priests, having accepted that image, will carry it to the cathedral, and when the church is opened, and the image is in the icon case, and they can no longer lift it, and at that time from the image from the eyes of tears, and by that they recognize the mournful. In general, we are talking about the fact that the icon is the letters of Luke the Evangelist, the Mother of God on the throne, the baby blesses with both hands, and that the icon is prayed for the weather in the event of foreign invasions. If the Virgin is disposed to help people, the icon comes out of the temple itself, and sweat streams down Mary's face. When everything is bad, the icon cannot be lifted, and it cries.

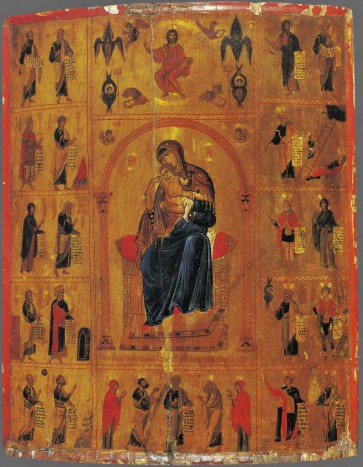

It is possible that the icon described in the Tale is a collective image of Kikkskaya and some other. It is interesting that the altar mentioned in the description, which is absent from all lists, is on one icon of the ΧΙΙ century, which can be considered the oldest copy of the Cypriot icon.

The Mother of God on the throne, with prophets and saints. ΧΙΙ century, monastery of St. Catherine at Sinai

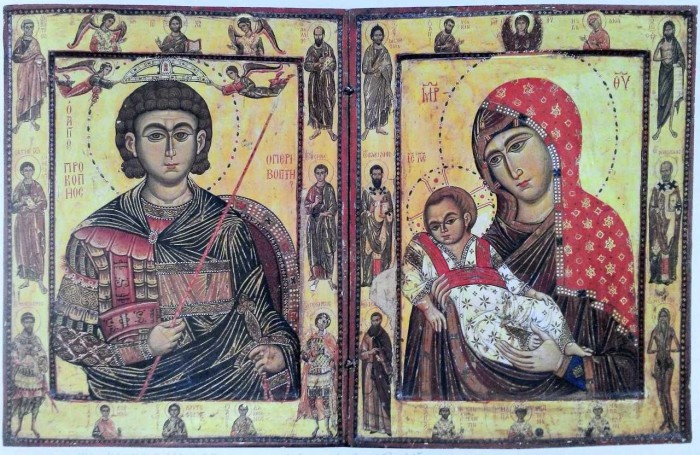

This icon is kept in the monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai, in general, not so far from Cyprus. She has a very complex and sophisticated program, which I will not dwell on now. It is important that the centerpiece of the icon, the Mother of God with the Child on the throne, in everything except the gesture of the Child, coincides with the description given in the Tale of the Cyprus Island. In addition, this icon one to one repeats the images of Our Lady of Kykkos. Only she is depicted in full growth, sitting on a throne (or throne) with pillows. And for the rest - the same pose of a baby, who clutches at the bedspread and rests his foot on the mother's shoulder, the same additional scarf on Mary's head. A variant of this type is the folded icon, also from the monastery of St. Catherine.

Fold-diptych with St. Procopius and Our Lady of Kykkos. 1280s, monastery of St. Catherine at Sinai

Here, however, the baby does not play, but lies in the arms of the mother. But for some reason, researchers publish it as Kikkotissa. From the foregoing, it turns out that the icon of the Mother of God on the throne, with saints and prophets of the XII century from the Sinai monastery can be the most accurate copy of the image that no one can see.

If the above is true, then we can assume that the icons of Our Lady of Kykkos, which spread throughout Cyprus, and then further, through Athos throughout the Orthodox world, right up to Moscow, represent a chamber half-length version of the miraculous image, hidden from human eyes, no matter the pious , unfit or just curious. The emergence of an abbreviated version can be justified by a very complex icon program, with many additional figures, but people still prayed to the Virgin, and the most common type of icons were half-length images. Therefore, only the most important things were reproduced in the lists.

In conclusion, I want to emphasize once again that an icon that cannot be seen is a unique cultural phenomenon. Let's hope that someday we will be able to find out what is really depicted on it. It would be very interesting.

Julia Buzykina

|