1) Amlinsky V. These are the people who come to me

2) Astafiev V. A capercaillie was homesick in a cage at the zoo.

3) G. Baklanov During the year of service in the battery, Dolgovushin changed many positions

4) Baklanov G. The German mortar battery hits again

5) Bykov V. The old man did not immediately tear him away from the opposite bank

6) Vasiliev B. I still have memories and one photograph from our class.

7) Veresaev V. Tired, with dull irritation boiling in his soul

8) Voronsky A. Natalya from a neighboring village

9)Garshin V. I live in the Fifteenth Line on Sredny Avenue

10) Glushko M. It was cold on the platform, grains were falling again

11) Kazakevich E. Only Katya remained in the secluded dugout.

12)Kachalkov S. How time changes people!

13) Round V. Still, time is an amazing category.

14) Kuvaev O. ...The tent dried out from the stones that retained the heat

15) Kuvaev O. The traditional evening of field workers served as a milestone

16) Likhachev D. They say that the content determines the form.

17) Mamin-Sibiryak D. Dreams make the strongest impression on me

18) Nagibin Yu. In the first years after the revolution

19)Nikitayskaya N. Seventy years have passed, but I can’t stop scolding myself.

20) Nosov E. What is a small homeland?

21) Orlov D. Tolstoy entered my life without introducing himself.

22) Paustovsky K. We lived for several days at the cordon

23) Sanin V. Gavrilov - that’s who didn’t give Sinitsyn peace.

24) Simonov K. All three Germans were from the Belgrade garrison...

25) Simonov K. It was in the morning.

26) Sobolev A. In our time, reading fiction

27) Soloveichik S. I was once on a train

28) Sologub F. In the evening we met again at the Starkins.

29) Soloukhin V. From childhood, from school

30) Chukovsky K. The other day a young student came to me

All three Germans were from the Belgrade garrison and knew very well that this was a grave Unknown Soldier and that in case of artillery shelling, the grave has thick and strong walls. This was, in their opinion, good, and everything else did not interest them at all. This was the case with the Germans.

The Russians also considered this hill with a house on top as an excellent observation post, but an enemy observation post and, therefore, subject to fire.

What kind of residential building is this? It’s something wonderful, I’ve never seen anything like it,” said the battery commander, Captain Nikolaenko, carefully examining the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier through binoculars for the fifth time. “And the Germans are sitting there, that’s for sure.” Well, have the data for firing been prepared?

Yes sir! - the young Lieutenant Prudnikov, who was standing next to the captain, reported.

Start shooting.

We shot quickly, with three shells. Two dug up the cliff right under the parapet, raising a whole fountain of earth. The third hit the parapet. Through binoculars one could see fragments of stones flying.

Lo and behold, it splashed! - said Nikolaenko. - Go to defeat.

But Lieutenant Prudnikov, who had previously been peering through his binoculars for a long time and intensely, as if remembering something, suddenly reached into his field bag, pulled out a German captured map of Belgrade and, putting it on top of his two-layout paper, began hastily running his finger over it.

What's the matter? - Nikolaenko said sternly. “There is nothing to clarify, everything is already clear.”

Allow me, one minute, comrade captain,” Prudnikov muttered.

He quickly looked several times at the plan, at the hill, and again at the plan, and suddenly, resolutely burying his finger in some point he had finally found, he raised his eyes to the captain:

Do you know what this is, Comrade Captain?

And that’s all - both the hill and this residential building?

This is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. I kept looking and doubting. I saw it somewhere in a photograph in a book. Exactly. Here it is on the plan - the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

For Prudnikov, who once studied at the history department of Moscow State University before the war, this discovery seemed extremely important. But captain Nikolaenko, unexpectedly for Prudnikov, did not show any responsiveness. He answered calmly and even somewhat suspiciously:

What other unknown soldier is there? Let's fire.

Comrade captain, allow me! - Prudnikov said pleadingly looking into Nikolaenko’s eyes.

What else?

You may not know... This is not just a grave. This is, as it were, a national monument. Well... - Prudnikov stopped, choosing his words. - Well, a symbol of all those who died for their homeland. One soldier, who was not identified, was buried instead of everyone else, in their honor, and now it is like a memory for the whole country.

“Wait, don’t jabber,” Nikolaenko said and, wrinkling his brow, thought for a whole minute.

He was a great-hearted man, despite his rudeness, a favorite of the entire battery and a good artilleryman. But, having started the war as a simple fighter-gunner and rising through blood and valor to the rank of captain, in his labors and battles he never had time to learn many things that perhaps an officer should have known. He had a weak understanding of history, if the issue did not involve his direct accounts with the Germans, and of geography, if the issue did not concern settlement, which must be taken. As for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, this was the first time he had heard about it.

However, although now he did not understand everything in Prudnikov’s words, he felt with his soldier’s soul that Prudnikov must be worried for good reason and that we're talking about about something really worthwhile.

“Wait,” he repeated once again, loosening his wrinkles. “Tell me exactly whose soldier he fought with, who he fought with—that’s what you tell me!”

The Serbian soldier, in general, is Yugoslav,” said Prudnikov. “He fought with the Germans in the last war of 1914.”

Now it's clear.

Nikolaenko felt with pleasure that now everything was really clear and the right decision could be made on this issue.

“Everything is clear,” he repeated. “It’s clear who and what.” Otherwise you are weaving God knows what - “unknown, unknown.” How unknown is he when he is Serbian and fought with the Germans in that war? Leave it alone!

Simonov Konstantin Mikhailovich - Soviet prose writer, poet, screenwriter.

On February 8, 1943, Belgorod was liberated, having been under the Germans since October 24, 1941, however, on March 18, 1943, it was again occupied by the Nazis. If during the first capture the city was abandoned by our troops without a fight, now this happened after a swift attack by the battle group Joachim Peiper (LAH).

They say that this attack even became a classic example and was included in tactics textbooks offensive operations motorized infantry (see details and). Piper is a separate big topic. And let his experience in capturing cities be adopted by military specialists, we will see what Belgorod was like at that time, which remained captured on German photographs:

1. April 22, 1943. German artillery marching through Belgorod to the front.

Chicherina Street ("Stometrovka"). On the left is the former theological seminary (approximately where new residential buildings of the “Slavyansky” complex are now being built). The equipment moves west, to the intersection with Novomoskovskaya (B. Khmelnitsky):

2. April, 1943. Redeployment of the 2nd Das Reich Division to Peresechnoe near Kharkov (we have not established where the Stug is going):

3. March, 1943. South side of Chicherin Street (“Hundred Metrovki”). View from the intersection with Novomoskovskaya (Bogdanka). A woman pushes a cart along Bogdanka towards Khargora:

4. March, 1943. In the same place, but on the northern side of Chicherin Street (“Stometrovki”). On the right are the buildings of the former theological seminary, on the far left is a piece of the Znamenskaya Church of the Monastery:

5. March, 1943. South side of the intersection of Chicherin and Novomoskovskaya. The building on the left, near which the Germans are swarming, was on the site of the current shopping center"Slavyansky", in front of it, already through Bogdanka, is the destroyed two-story building of the former hotel of the merchant Yakovleva (the hotel was the most respectable in pre-revolutionary times):

6. March, 1943. And this is Bogdanka. The location of the current stop "Rodina" towards Khargora. On the right is the former Yakovleva hotel; in the distance, on the site of the current entrance to BelSU, you can see the mill building:

7. July 1943. The western side of Novomoskovskaya Street (B. Khmelnitsky) opposite the brewery, a mill on the left bank of the Vezelka is visible in the distance:

8. July 1943. Tiger at the brewery. In the distance are Suprunovka and Khargora. (A well-known photo to many):

9. July 1943. Bogdanka from the Suprunovka side. Bridge over Vezelka (it was located a little east of the current one), brewery:

10. July 1943. Smolensk Cathedral from the air (I have already published the picture, but now it is of better quality):

11. June 11, 1943. Camouflaged bridge over Vezelka (photo taken from the right-southern bank of the river):

12. June 11, 1943. The photo was taken from the bridge over the Vezelka in the direction of the left bank. Four-story mill building on the site of BelSU:

14. June 11, 1943. The brewery from the courtyard (the building on the right is easily recognizable, even though it is now disfigured by sawed-off window openings of different sizes):

16. The road between Belgorod and Kharkov in March 1943. A damaged tank from the “Moscow Collective Farmer” column:

N.B. Photos of Belgorod on the website NAC.gov.pl were found thanks to Sergei Petrov.

You can read the “photo report” of the Germans about the first occupation of Belgorod in 1941-42

Why is it important to preserve the memory of the dead? What is the significance of war monuments? These and other questions are raised by K. M. Simonov, reflecting on the problem of preserving the memory of the war

Discussing this problem, the author talks about an incident that occurred during the Great Patriotic War. Patriotic War. The Russian battery, led by Captain Nikolaenko, examines and prepares to fire at the observation post in which three Germans are hiding.

Our experts can check your essay according to the Unified State Exam criteria

Experts from the site Kritika24.ru

Teachers of leading schools and current experts of the Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation.

An important role in the episode is played by Lieutenant Prudnikov, who once studied at the Faculty of History and is aware of the importance of historical monuments. It is he who recognizes the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the observation post. The writer focuses on the fact that, despite the captain’s misunderstanding and indifference, Prudnikov tries to explain to Nikolaenko what the significance of the monument is: “One soldier, who was not identified, was buried instead of everyone else, in their honor, and now it is like a memory for the whole country " The captain, turning out to be not a stupid person, although not very educated, feels the power of his subordinate’s words. IN rhetorical question, asked by Nikolaenko, the morally correct conclusion sounds: “What kind of unknown is he, when he is Serbian and fought with the Germans in that war?”, and the captain orders the fire to be put off.

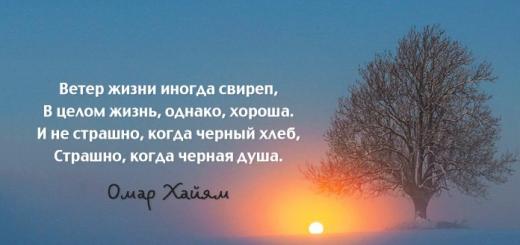

The author believes that it is very important to preserve the memory of those killed in the war, and it is unacceptable to treat war monuments with disdain. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is not just an old burial ground, but a national monument that must be protected.

It is difficult to disagree with the author's position. Indeed, war monuments are the most important part cultural heritage humanity. They are the ones who help future generations always remember the exploits and heroism of their great-grandfathers, and how terrible war really is.

Many writers have thought about the importance of preserving the memory of those killed in the war. In his story “And the Dawns Here Are Quiet,” B. Vasiliev talks about five young girls: Zhenya Komelkova, Rita Osyanina, Lisa Brichkina, Sonya Gurvich and Gala Chetvertak. Fighting on an equal basis with men, they show true endurance and real courage. Girl anti-aircraft gunners die a heroic death, defending their homeland and fighting enemies until their last breath. However, their commander, Fedot Vaskov, remains alive. Throughout the rest of his life, Vaskov preserves the memory of heroic feat girls. And in fact, together with his adopted son, Fedot comes to the graves of the anti-aircraft gunner heroines and pays tribute to them.

However, it is important to preserve the memory of wars not only last centuries. In “The Tale of the Massacre of Mamai” S. Ryazanets tells about the battle on the Kulikovo field, where the troops of Grand Duke Dmitry Donskoy and Khan of the Golden Horde Mamai clashed. Written with incredible factual accuracy, this work is a true literary and historical monument. Only thanks to the legend we have the opportunity to learn about the cunning and invented tactics of Dmitry Donskoy, about his feat and about the courage of the Moscow soldiers.

Indeed, preserving the memory of those killed in the war and their true heroism is one of the most important tasks modern society. It is necessary to recognize the value of national monuments, and the desire to teach the younger generation to treat them with care should become one of the main priorities of humanity.

(442 words)

Updated: 2018-02-18

Attention!

Thank you for your attention.

If you notice an error or typo, highlight the text and click Ctrl+Enter.

By doing so, you will provide invaluable benefit to the project and other readers.

My Katya had a text by Maria Vasilievna Glushko

It was cold on the platform, grains were falling again, she walked around, stamping her feet, and breathed on her hands. Then she returned and asked the conductor how long we would be standing.

This is unknown. Maybe an hour, maybe a day.

She was running out of food, she wanted at least something

Buy it, but they didn’t sell anything at the station, and she was afraid to leave.

The elderly guide looked at her stomach:

We'll probably be down for an hour, you see, they've put us on the spare tire.

And she decided to get to the station, for this she had to climb over three freight trains, but Nina had already adapted to this.

The station was packed with people, sitting on suitcases, bundles, and just on the floor, having laid out food, having breakfast. Children were crying, tired women were fussing around them, calming them down! one was breastfeeding a child, staring ahead with longing, submissive eyes. In the waiting room, people were sleeping on hard plywood sofas, a policeman walked between the rows, woke up the sleeping people, and said: This is not allowed. Nina was surprised by this: why wasn’t she supposed to sleep?

She came out onto the station square, densely dotted with colorful spots of coats, fur coats, and bundles; here, too, whole families of people sat and lay, some were lucky enough to occupy benches, others settled right on the asphalt, spreading a blanket, raincoats, newspapers... In this thicket of people, in this hopelessness, she felt almost happy, yet I’m going, I know where and to whom, and the war is driving all these people into the unknown, and how long they have to sit here, they themselves don’t know.

Suddenly an old woman screamed, she was robbed, two boys stood next to her and were also crying, the policeman said something angrily to her, held her hand, and she struggled and screamed: “I don’t want to live!” I don't want to live! Nina began to cry, how is she now with children without money, is there really nothing we can do to help? There is such a simple custom with a hat in a circle, and when before the war tuition fees were introduced at institutes, they used it in Baumansky, throwing as much as they could. So they paid for Seryozhka Samoukin, he was an orphan, and his aunt could not help him, and he was about to be expelled. And here there are hundreds and hundreds of people nearby, if everyone gave at least a ruble... But everyone around looked sympathetically at the screaming woman and no one moved from their place.

Nina called an older boy, rummaged in her purse, pulled out a hundred-dollar note, and stuck it in his hand:

Give it to your grandmother... And she quickly went so as not to see his tear-stained face and bony fist clutching the money. She still had some money left that her father gave, five hundred rubles, nothing, enough to get to Tashkent, and then Lyudmila Karlovna, I won’t be lost.

She asked some local woman how far the bazaar was. It turned out that if you go by tram, there is only one stop, but Nina did not wait for the tram, she missed the movement, the walking, and went on foot. She needed to buy something, she would have come across some lard, but there was no hope for that, and suddenly a thought flashed through her mind: what if there, at the market, she saw Lev Mikhailovich! After all, he stayed to get food, but where, besides the market, can you get it now? Together they will buy everything and return to the train! And she doesn’t need any captains or any other traveling companions; food will only sleep for half the night, and then it will force him to lie down, and she will sit at his feet, as he sat for five whole nights! And in Tashkent, if he doesn’t find his niece, she will persuade his stepmother to take him in, and if she doesn’t agree, she will take her brother Nikita and they will settle somewhere in an apartment together with Lev Mikhailovich, nothing will be lost!

The market was completely empty, sparrows were jumping along the bare wooden counters, pecking something out of the cracks, and only under the canopy stood three thickly dressed women, stamping their feet in felt boots, in front of one stood an enamel bucket with soaked apples, the other was selling potatoes, laid out in piles, the third sold seeds.

Lev Mikhailovich, of course, was not here.

She bought two glasses of sunflower seeds and a dozen apples, looked in her purse for something to take them into, the owner of the apples took out a sheet of newspaper, tore off half, twisted

bag, put apples in it. Nina immediately, at the counter, greedily ate one, feeling her mouth blissfully filled with spicy-sweet juice, and the women looked at her pitifully and shook their heads:

Lord, you are a child... In such a whirlwind with a child...

Nina was afraid that questions would now begin; she did not like this and quickly walked away, still looking around, but without any hope of seeing Lev Mikhailovich.

Suddenly she heard the sound of wheels and was afraid that it was her train taking her away, she quickened her pace and was almost running, but from a distance she saw that those nearby trains were still standing, which meant that her train was in place.

That old woman with the children was no longer on the station square; she had probably been taken somewhere, to some institution where they would help. She wanted to think so; it was calmer this way: to believe in the unshakable justice of the world.

She wandered along the platform, cracking seeds, collecting the husks in her fist, walked around the shabby one-story station building, its walls were covered with pieces of paper, advertisements, written in different handwritings, different inks, usually with a chemical pencil, glued with bread crumbs, glue, resin and God knows what else . I am looking for the Klimenkov family from Vitebsk, I ask those who know to inform them at the address... Anyone who knows the whereabouts of my father Nikolai Sergeevich Sergeev, please inform... Dozens of pieces of paper, and right on top, along the wall in charcoal: Valya, my mother is not in Penza, I’m moving on. Lida.

All this was familiar and familiar, at every station Nina read such announcements, similar to cries of despair, but every time her heart sank with pain and pity, especially when she read about lost children. She even copied one for herself, just in case, large and densely written in red pencil, it began with the word I beg! Are you lucky enough to find out about the girl?

Reading such advertisements, she imagined people traveling around the country, walking, rushing through cities, wandering along the roads, looking for loved ones, a dear drop in the human ocean, and thought that war is not only terrible with deaths, it is also terrible with separations!

She again climbed over the two trains in reverse order, holding the sodden newspaper bag with difficulty, and returned to the compartment. She gave everyone apples, one came out, and the boy got two, but his mother returned one to Nina and said sternly:

You can not do it this way. You are spending money, but the road is long, and it is unknown what awaits us. You can not do it this way.

Nina did not argue, ate an extra apple and was about to crumple up the sodden sheet of newspaper, but her eye caught something familiar, she, holding the scrap in the air, ran her gaze and suddenly came across her last name, or rather, her father’s last name: Vasily Semenovich Nechaev. This was a Decree on conferring the rank of general. At first she thought it was a coincidence, but no, there couldn’t be a second major general of artillery, Vasily Semenovich Nechaev. The newspaper scrap trembled in her hands, she quickly looked at everyone in the compartment and again looked at the newspaper, a pre-war newspaper had been preserved, and it was from this scrap that they made her a bag, just like in a fairy tale! She was simply tempted to tell her fellow travelers about such a miracle, but she saw how exhausted these women were, what patient grief was on their faces, and said nothing. She folded the newspaper, hid it in her purse, lay down, and covered herself with her coat. She turned to the partition and buried her head in her cap, which smelled faintly of perfume. I remembered how in 1940 my father came from Orel, came to their dormitory in a brand new general’s uniform with red stripes; this uniform had just been introduced then, and took them to dinner. Students, he said, are always hungry, not from hunger, but from appetite, and whenever he arrived, he always hurried to feed them, taking her girlfriends with him. He let go of the car, they set off on foot, and Victor walked with them as a groom. They walked and gradually became surrounded by boys, the boys started an argument about insignia, and one ran

forward, and so he walked, backing away, looking at the stars on his velvet buttonholes. Her father stopped embarrassed, hid in some entrance and sent Victor for a taxi... Now Nina was remembering everyone from whom the war had separated her: her father, Victor, Marusya, the boys from her year... Isn’t this the crowded train stations in a dream, crying women, empty markets, and I'm going somewhere... To an unfamiliar, alien Tashkent: Why? For what?