So, on January 29, 1903, the Varyag arrived in Chemulpo (Incheon). There is less than a month left before the fight, which took place on January 27 next year - what happened during these 29 days? Arriving at the place of duty, V.F. Rudnev quickly discovered and reported that the Japanese were preparing to occupy Korea. The materials of the historical commission noted:

“Cap. 1 rub. Rudnev reported in Port Arthur about the establishment of food warehouses by the Japanese in Chemulpo, at the Jong tong-no station and in Seoul. According to reports from Cap. 1 rub. Rudnev, the total amount of all Japanese provisions had already reached 1,000,000 poods, and 100 boxes of ammunition were delivered. The movement of people was continuous; in Korea there were already up to 15 thousand Japanese, who, under the guise of Japanese and in a short time before the war, settled throughout the country; the number of Japanese officers in Seoul reached 100, and although the Japanese garrisons in Korea officially remained the same, the actual number of garrisons was much greater. At the same time, the Japanese openly delivered scows, tugboats and steam boats to Chemulpo, which, as the commander of the region reported. “Varyag” clearly indicated extensive preparations for landing operations... All these preparations pointed too clearly to the inevitable Japanese occupation of Korea.”

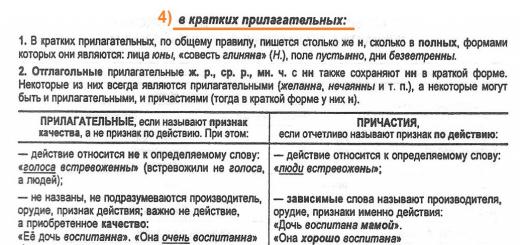

The same thing was conveyed by the Russian military agent in Japan, Colonel Samoilov, who on January 9, 1904 reported on the chartering of numerous ships, the mobilization of divisions, etc. Thus, the preparation for the occupation of Korea was not a secret either for the Viceroy or for higher authorities, but they continued to remain silent - as we said in the previous article, Russian diplomats decided not to consider the landing of Japanese troops in Korea as a declaration of war on Russia, as Nikolai II and notified the Viceroy. It was decided to consider only the landing of Japanese troops north of the 38th parallel as dangerous, and everything to the south (including Chemulpo) was not considered dangerous and did not require additional instructions for the stationers. We wrote about this in more detail in a previous article, but now we’ll just note once again that the refusal of armed opposition to the Japanese landing in Korea was accepted by much higher authorities than the commander of the Varyag, and the instructions he received completely forbade interfering with the Japanese.

But let’s return to “Varyag”. Without a doubt, the best way to avoid the loss of the cruiser and gunboat "Koreets" would be to recall them from Chemulpo, together with the Russian envoy to Korea A.I. Pavlov or without him, but this, unfortunately, was not done. Why is this so - alas, it is very difficult to answer this question, and one can only speculate. Without a doubt, if it had already been decided that the Japanese landing in Korea would not lead to war with Russia, then there were no grounds for recalling the Russian stationers from Chemulpo - the Japanese were going to land, and let them be. But the situation changed decisively when the Japanese broke off diplomatic relations: despite the fact that in St. Petersburg they believed that this was not yet a war, the risk to which the cruiser and gunboat were exposed clearly outweighed the benefits of our military presence in Korea.

Strictly speaking, events developed like this: at 16.00 on January 24, 1904, a note about the severance of relations was officially received in St. Petersburg. What was important was that the classic phrase in this case: “Diplomatic relations with the Russian government no longer have any value and the government of the Japanese Empire has decided to sever these diplomatic relations” was supplemented by a very frank threat: “The government of the empire, in order to protect its sovereignty and interests, is leaving reserves the right to act at its own discretion, considering this the best way to achieve the stated goals.” This was already a real threat of war: but, alas, it was not taken into account.

The fact is that, for the reasons stated earlier, Russia did not want war at all in 1904 and, apparently, did not want to believe in its beginning. Therefore, in St. Petersburg they preferred to listen to the Japanese envoy Kurino, who never tired of repeating that the severance of diplomatic relations is not a war, and everything can still be arranged for the better. As a result, our Ministry of Foreign Affairs (and Nicholas II), in fact, allowed themselves to ignore reality, relying on the mirages that the Japanese envoy painted for them and in which they really wanted to believe. Moreover, there was a fear that “our heroes in the Far East might suddenly get carried away by some military incident” (words of Foreign Minister Lamsdorff). As a result, a grave mistake was made, which may have ultimately ruined “Varyag”: the Viceroy was notified by St. Petersburg of the severance of relations with Japan the very next day, January 25, but the second part of the Japanese note (about the “right to act at his own discretion” ) was omitted from the message, and E.I. Alekseev did not find out anything about this.

Let's be frank - it is far from a fact that, having received the text of the Japanese note in full, E.I. Alekseev would have taken measures to recall the “Varyag” and “Korean”, and in addition, in order for these measures to be successful, it was necessary to act with lightning speed: it is known that speed of action is one of the virtues of the Viceroy E.I. Alekseeva was not included. But still there was some chance, and it was missed.

It is also interesting how E.I. Alekseev disposed of the information he received: he notified the consuls in Hong Kong and Singapore about the severance of diplomatic relations with Japan, notified the Vladivostok detachment of cruisers and the gunboat Manchur, but did not report anything about this to either the Port Arthur squadron or the envoy to Korea A.I. . Pavlov, nor, of course, the commander of the Varyag. One can only assume that E.I. Alekseev received the task “not to provoke the Japanese under any circumstances” and, guided by the principle “no matter what happens,” he chose not to tell the Arthurian sailors anything. The author of this article, unfortunately, was unable to figure it out when squadron chief O.V. learned about the severance of diplomatic relations. Stark and the Chief of Naval Staff of the Viceroy V.K. Vitgeft. It is possible that they also received this information late, so perhaps the reproach of N.O. Essen (expressed in his memoirs) that the latter’s inaction led to the untimely recall of Russian stationers in Chemulpo and Shanghai (the gunboat Majur was there) is not entirely justified. But in any case, the news, not about the severance of diplomatic relations, but about the beginning of the war, was sent to Chifa for the Varyag only on January 27, after a successful attack by Japanese destroyers, which blew up the Retvizan, Tsarevich and Pallada and on the day , when "Varyag" entered into its first and last battle. Of course, this was a belated warning.

What was happening on the cruiser at that time? Already on January 24 (the day when St. Petersburg officially received notification of the severance of diplomatic relations), the commanders of the foreign stationers “confidentially” informed Vsevolod Fedorovich Rudnev about this regrettable event. The commander of the Varyag immediately requested instructions from Admiral Vitgeft: “rumors have reached us of a break in diplomatic relations; Due to the frequent delay of dispatches by the Japanese, I ask you to inform us whether we have received orders for further action,” and a request to envoy A.I. Pavlov in Seoul: “I heard about the severance of diplomatic relations, please provide information.” However, no response was received from Port Arthur, and A.S. Pavlov replied:

Apparently, upon receipt of V.F.’s response. Rudnev took the first train to Seoul (left on the morning of January 25, 1904) and there, in the Korean capital, the last chance to take Russian stationary troops away from Chemulpo before the start of the war was missed.

During the conversation it quickly became clear that A.I. Pavlov, like V.F. Rudnev has not received any answers to his requests or any new orders for a week now. All this strengthened the opinion that the Japanese were intercepting and detaining dispatches from the commander of the Varyag and the Russian envoy in Korea: but how should this situation be resolved? V.F. Rudnev offered to take the envoy and consul and immediately leave Chemulpo, but A.I. Pavlov did not support such a decision, citing the lack of appropriate instructions from his leadership. The envoy proposed sending the gunboat “Koreets” to Port Arthur with a report - according to A.I. Pavlov, unlike telegrams, the Japanese could not intercept them, which means that in Port Arthur they would have been able to put two and two together and send orders, say, by a destroyer.

As a result, the commander of the “Varyag”, returning to the cruiser, on the same day of January 25, ordered the dispatch of the “Korean” to Port Arthur - according to his order, the gunboat was supposed to leave Chemulpo on the morning of January 26. On the night of January 25-26, the Japanese stationary “Chiyoda” left the raid (strictly speaking, it would be more correct to write “Chiyoda”, but for the convenience of the reader we will adhere to the historically established and generally accepted names in Russian-language literature). Unfortunately, for unknown reasons, “Korean” did not leave in the morning, as V.F. demanded. Rudnev, but delayed until 15.40 on January 26 and, while trying to leave, was intercepted by a Japanese squadron en route to Port Arthur.

Gunboat "Korean"

We will not describe in detail the preparations and nuances of the landing operation that the Japanese were preparing. Let us only note that it was supposed to be carried out in Chemulpo, but only on condition that there were no Russian warships there, otherwise it was necessary to land not far from Chemulpo, in Asanman Bay. It was there that the general gathering of the Japanese ships participating in the operation was scheduled, and it was there that the Chiyoda left the Chemulpo raid. But on January 26, 1904, when all the “actors” were assembled, the commander of the operation, Rear Admiral Sotokichi Uriu, realizing that the occupation of Seoul must be carried out as soon as possible, and having received information that the Russian stationary were behaving as usual and not taking no threatening actions, decided to land in Chemulpo, which, of course, as a landing site was much more convenient than Asanman Bay. However, the Japanese, of course, had to take into account the possibility of intervention by Russian ships - they should have been neutralized if possible.

Sotokichi Uriu gathered with him the commanders of warships and captains of transport ships transporting troops, announced to them the plan of operation and brought to their attention his order No. 28. This order is very important for understanding what happened next, so we will present it in full. Although some points of the order that are of little significance for our analysis could be omitted, in order to avoid any speculation on this topic, we will quote it without cuts:

“Secret.

February 8, 37 Meiji ( January 26, 1904 old style - approx. auto)

On board the flagship "Naniva" Asanman Bay.

1. The situation with the enemy as of 23.00 on January 25: the Russian ships “Varyag” and “Koreets” are still anchored in Chemulpo Bay;

2. The landing point for the expeditionary force is Chemulpo Bay, upon arrival at which the landing of troops should immediately begin;

3. If Russian ships meet outside the anchorage in Chemulpo Bay, abeam Phalmido ( Yodolmi - approx. auto) or to S from it, then they must be attacked and destroyed;

4. If Russian ships do not take hostile actions against us at the anchorage in Chemulpo Bay, then we will not attack them;

5. Simultaneously with preparations to leave the temporary anchorage in Asanman Bay, the forces of the Detachment are divided as follows:

- 1st tactical group: (1) “Naniwa”, (2) “Takachiho”, (3) “Chiyoda” with the 9th destroyer detachment assigned to it;

- 2nd tactical group: (4) “Asama”, (5) “Akashi”, (6) “Niitaka” with the 14th destroyer detachment attached to it;

6. Actions for entering the anchorage in Chemulpo Bay:

a) “Chiyoda”, “Takachiho”, “Asama”, the 9th destroyer detachment, transport ships “Dairen-maru”, “Otaru-maru”, “Heize-maru” enter the anchorage in Chemulpo Bay;

b) The 9th detachment of destroyers, having passed the island of Phalmido, goes forward and calmly, without arousing suspicion from the enemy, enters the anchorage. Two destroyers stand at a point inaccessible to enemy fire, and the other two, with a peaceful look, take such a position next to the “Varyag” and “Korean”, so that in an instant their fate can be decided - to live or die;

c) “Chiyoda” independently chooses a suitable place for itself and anchors there;

d) A detachment of transport ships, following in the wake of the Asama, after the failure of the Chiyoda and Takachiho, enters the anchorage as soon as possible and immediately begins unloading troops. It is advisable that they be able to enter the port during the evening high tide.

e) "Naniwa", "Akashi", "Niitaka" follow in the wake of a detachment of transport ships, and then anchor S from the islet of Harido in a line to the NE. The 14th destroyer detachment, having finished receiving coal and water from the Kasuga Maru, is divided into two groups consisting of two destroyers each. One group occupies a position to the S of the islet of Phalmido, and the other is located near "Naniva". If at night the enemy begins to move from the anchorage into the open sea, then both groups must attack and destroy him;

f) Before sunset, the Asama leaves its position near the Incheon anchorage and moves to the Naniwa anchorage and anchors there;

7. If the enemy takes hostile actions against us, opens artillery fire or launches a torpedo attack, we must immediately attack and destroy him, while acting in such a way as not to cause damage to the ships and vessels of other powers at anchor;

8. The ships located near the island of Harido move to a temporary anchorage in Asanman Bay by dawn the next day;

9. Ships and destroyers anchored in Chemulpo Bay, after making sure that the landing is completely completed, move to a temporary anchorage in Asanman Bay;

10. “Kasuga-maru” and “Kinshu-maru”, having finished bunkering the destroyers of the 14th detachment with coal and water, anchor at the entrance to Masanpo Bay and do not open anchor lights at night, observing blackout;

11. Destroyers carrying combat guard in Chemulpo Bay, having discovered that the enemy ships have begun to move from the anchorage to the open sea, immediately begin to pursue them and, when they find themselves to the S of the islet of Phalmido, they must attack and destroy them;

12. During the anchorage, be prepared for immediate removal from the anchor, for which purpose prepare everything necessary for riveting the anchor chains, keep the boilers steaming and set up a reinforced signal and observation watch.”

Thus, the Japanese admiral's plan was very simple. He needed to land troops in Chemulpo, but without shooting in the roadstead, which would have been extremely disapproved of by foreign stationers. Accordingly, he was going to first enter the bay and take aim at the Russian ships, and only then lead transports with landing troops to the raid. If the Russians open fire, great, they will be the first to violate neutrality (as we said earlier, no one considered the landing of troops on Korean territory to be a violation of neutrality) and will be immediately destroyed by destroyers. If they try to get close to the transports, they will come under the gun of not only destroyers, but also cruisers, and when they try to shoot, again, they will be immediately destroyed. If “Varyag” and “Koreets” try to leave Chemulpo without firing, then the destroyers will accompany them and sink them with torpedoes as soon as they leave the roadstead, but even if the Russians by some miracle manage to break away, they will pass by the Japanese cruisers blocking the exit they won't succeed anyway.

The “funny” thing was that with a 99.9% probability foreigners would not consider a torpedo attack on Russian ships as a violation of neutrality. Well, two Russian ships unexpectedly exploded, who knows for what reason? No, of course, among the commanders of foreign ships there were no crazy people who were unable to put two and two together and understand whose hands this matter was. But, as we said earlier, the European and American ships in the Chemulpo roadstead did not defend Korean neutrality, but the interests of their countries and their citizens in Korea. Any actions of the Japanese that did not threaten these interests were indifferent to these residents. The Russian-Japanese War was a Russian-Japanese affair in which neither the Italians, nor the French, nor the Americans had any interest. Therefore, the destruction of the “Varyag” and “Korean”, provided that no one else was hurt, would have caused only a formal protest on their part, and even then it is unlikely, because the British “Talbot” was considered the eldest on the roadstead, and England's interests in this war were entirely on the side of Japan. Rather, one should have expected unofficial congratulations to the Japanese commander...

In fact, S. Uriu was going to build a wonderful trap, but man proposes, but God disposes, and at the very entrance to the roadstead his ships collided with the “Korean” that had set off for Port Arthur. What happened next is quite difficult to describe, because domestic and Japanese sources completely contradict each other, and often even contradict themselves. Perhaps in the future we will make a detailed description of this collision in the form of a separate article, but now we will limit ourselves to the most general overview - fortunately, a detailed clarification of all the nuances of maneuvering of the “Korean” and the ships of the Japanese detachment is not necessary for our purposes.

Canonical for Russian-language sources is the description presented in “The work of the historical commission to describe the actions of the fleet in the war of 1904-1905.” at the Naval General Staff." According to him, the “Korean” weighed anchor at 15.40, and a quarter of an hour later, at 15.55, they saw a Japanese squadron on it, which was moving in two wake columns. One of them was formed by cruisers and transports, with the Chiyoda, Takachiho, and Asama leading the way, followed by three transports and the rest of the cruisers, and the second column consisted of destroyers. The "Korean" tried to pass by them, but this turned out to be impossible, since the Japanese columns spread out to the sides, and the gunboat was forced to follow between them. At this time, "Asama" turned across the course of the "Korean", thereby blocking the exit to the sea. It became clear that the Japanese squadron was not going to release the “Korean” into the sea, and its commander G.P. Belyaev decided to return to the roadstead, where Japanese provocations would hardly be possible. But at the moment of the turn, the gunboat was attacked by torpedoes from destroyers, which, however, passed by, and one sank before reaching the side of the ship. G.P. Belyaev gave the order to open fire, and immediately canceled it, because the “Korean” was already entering the neutral roadstead of Chemulpo, however, one of the gunners managed to fire two shots from a 37-mm gun. In general, everything is clear and logical, and the actions of the Japanese, although completely illegal, are consistent and logical. But Japanese reports cast serious doubt on this.

Armored cruiser "Asama", 1902

According to Japanese data, the ships of S. Uriu initially acted according to a previously planned plan. The Japanese moved in the following formation:

The diagram is taken from the monograph by A.V. Polutov “The landing operation of the Japanese army and navy in February 1904 in Inchon”

When the columns approached the beam of Fr. Phalmido (Yodolmi), then the leading Chiyoda and Takachiho separated from the main forces and, accompanied by the 9th destroyer detachment, increased speed and moved forward - in accordance with the plan of the landing operation, they were supposed to be the first to enter the Chemulpo roadstead, in order to take aim at Russian hospitalists. And when Fr. They passed Phalmido for about three miles, and suddenly the Japanese ships discovered the “Korean” coming towards them. Thus, a situation not envisaged by Order No. 28 arose.

If “Korean” had come out a little earlier and the meeting would have taken place behind Fr. Phalmido, the Japanese would simply destroy the Russian ship, as provided for by the order. But the meeting took place between Fr. Phalmido and raid, the order did not regulate such a situation, and the intentions of the “Korean” were unclear. The Japanese feared that the gunboat would attack the transports, so the Chiyoda and Takachiho prepared for battle - the gunners took their places at the guns, but crouched behind the bulwarks so that their warlike preparations were not visible if possible. When the leading cruisers approached the “Koreyets”, they saw that the Russian ship was not preparing for battle; on the contrary, a guard was built on its deck to greet them. Whether at that moment the “Korean” found herself between the cruisers and destroyers cannot be said with certainty - on the one hand, the distance between the Japanese cruisers and destroyers did not exceed 1-1.5 cables, but on the other, the “Korean” parted ways with the “Chiyoda” and “Takachiho” at a distance of no more than 100 m, so, in principle, it could have wedged itself between one and the other.

In any case, the “Korean” found himself between two detachments, one of which passed by him to the Chemulpo roadstead, and the second, led by the “Asama”, walked towards the Russian gunboat. There was some confusion on the Japanese transports, and then the armored cruiser left the formation, turning 180 degrees, and set off on a course parallel to that of the Korean, in order to remain between the Russian gunboat and the caravan escorted by the Asama. But then “Asama” again turned to the right - apparently, it was this maneuver that was adopted by G.P. Belyaev for trying to block his access to the sea. The funny thing is that the commander of the Asama did not think anything of the kind - according to his report, he turned to the right in order to evade the torpedoes that, in his opinion, the Korean could fire at him.

Accordingly, G.P. Belyaev decided to return to the roadstead and turned back. We have already seen that the commanders of Chiyoda and Takachiho, having made sure that the gunboat had no aggressive intentions, moved further towards the raid in order to complete the task assigned to them, but the commander of the 9th detachment of Japanese destroyers had a different opinion. He believed that the Koreets could be conducting reconnaissance for the Varyag and that the Russians might be planning an attack. Therefore, having parted ways with the “Korean”, he reorganized from the wake column to the front, and then took the “Korean” in pincers: the destroyers “Aotaka” and “Hato” took up a position on the left side of the “Korean”, and “Kari” and “Tsubame” - from the right... more precisely, they should have taken it. The fact is that, while performing the maneuver, the “Tsubame” did not calculate, went beyond the fairway and jumped onto the rocks, so that then the “Korean” was accompanied by only three destroyers, while the torpedo tubes on them were put on alert.

And when the “Korean” began its turn back to Chemulpo, it turned out that the Russian ship went towards the Japanese destroyers, who found themselves between it and the edge of the fairway. The destroyer "Kari" decided that this created a dangerous situation, and on the other hand, it made it possible to finish off the "Korean" while none of the foreign stationers saw it, and fired a torpedo, which the "Korean" dodged. As they say, “a bad example is contagious,” so “Aotaka” and “Hato” immediately increased their speed and approached the “Korean”, while “Hato” fired one torpedo, and “Aotaka” for unknown reasons refused to attack. It can be assumed that the distance is to blame - at the moment when the “Korean” entered the Chemulpo roadstead, the distance between it and the “Aotaka” was still about 800-900 m, which was quite far for a torpedo shot in those years.

In general, everything is as usual - the Russians have one maneuvering picture, the Japanese have a completely different one, while information about ammunition consumption also differs: the Russians believe that three torpedoes were fired at the "Korean", the Japanese - that two, while the Russians claim Although the “Korean” fired two artillery shots, the Japanese note that the gunboat fired at all three destroyers that took part in the attack (which, you see, is extremely difficult to do with two shells).

Separately, I would like to draw attention to the Tsubame accident - moving along the fairway along which the Varyag and Koreets would go into battle the next day, chasing a gunboat that had a speed of 10-12 knots at most, the destroyer managed to end up on the rocks and receive damage, losing one left propeller blade and damaging three right propeller blades, which is why its speed was now limited to 12 knots. True, the Japanese claim that they pursued the “Korean” at as much as 26 knots, but this is extremely doubtful for the “Tsubame” - it flew onto the rocks almost immediately after the turn, and hardly managed to gain such speed (if even one of the Japanese destroyers, which, again, is somewhat doubtful). In general, it is unlikely that a small skirmish between a Russian gunboat and Japanese destroyers can be called a battle, but, without a doubt, the pitfalls of the Chemulpo fairway proved to be most effective in it.

In any case, as soon as the “Korean” returned to the Chemulpo roadstead, the Japanese abandoned the attack, and “assuming as peaceful an appearance as possible” took up the positions assigned to them: “Aotaka” anchored 500 m from the “Varyag”, “Kari” - at the same distance from the “Korean”, and “Hato” and “Tsubame”, which had independently removed itself from the rocks, hid behind the English and French ships, but, in accordance with order No. 28, were ready to attack at any moment.

Now let's look at this situation from the position of the commander of the cruiser "Varyag". Here the “Korean” leaves the waters of the roadstead and goes along the fairway into the sea, and then miracles begin. First, two Japanese cruisers, Chiyoda and Takachiho, enter the raid. The returning "Korean" suddenly appears behind them - whether the Varyag heard its shots is unclear, but, of course, they could not have known about the torpedo attack.

In any case, it turned out that on the “Varyag” they either saw that the “Korean” was shooting, or they didn’t see it, and either they heard the shots, or they didn’t. In any of these cases, either the Varyag saw that the “Korean” was shooting, but the Japanese did not shoot, or they heard two shots (which, for example, could well have been warning shots), while it was unclear who fired. In other words, nothing that could be seen or heard on the cruiser Varyag required immediate intervention by armed force. And then Japanese cruisers and 4 destroyers entered the raid, taking up positions not far from the Russian ships, and only then, finally, V.F. Rudnev received information about the events that took place.

At the same time, again, it is not entirely clear when exactly this happened - R.M. Melnikov reports that the "Korean", having returned to the roadstead, approached the "Varyag" from where he briefly conveyed the circumstances of his meeting with the Japanese squadron, and then the gunboat anchored. At the same time, the “Work of the Historical Commission” does not mention this - from its description it follows that the “Korean”, having entered the roadstead, anchored 2.5 cables from the “Varyag”, then G.P. Belov went to the cruiser with a report, and 15 minutes after the gunboat anchored, the Japanese destroyers took up positions - two ships each 2 cables away from the Varyag and the Koreyets. Obviously, in 15 minutes it was only possible to lower the boat and arrive at the Varyag, that is, the Russian ships were at gunpoint when G.P. Belov only reported to V.F. Rudnev about the circumstances of the battle.

In general, despite the difference in interpretations, both sources agree on one thing - by the time Vsevolod Fedorovich Rudnev became aware of the attack undertaken by the Japanese destroyers:

1. The “Korean” was already out of danger;

2. The 9th detachment of destroyers (and, probably, also cruisers) were located in close proximity to the Varyag and Koreyets.

In this situation, for the cruiser "Varyag" opening fire and entering into battle made absolutely no sense. Of course, if the “Korean” was attacked, and the “Varyag” saw this, then the cruiser had to, despising all danger, go to the rescue of the “Korean” and engage in an arbitrarily unequal battle. But by the time the cruiser learned about the Japanese attack, everything was already over, and there was no need to save the “Korean”. And after a fight they don’t wave their fists. As the old British proverb says, “A gentleman is not the one who does not steal, but the one who does not get caught”: yes, the Japanese fired torpedoes at the “Korean”, but none of the foreign stationary saw this and could not confirm this, but means that there was only “word against word” - in diplomacy this is the same as nothing. Suffice it to recall the almost century-long confrontation between the official Russian and Japanese - the Russians claimed that the first shots in the war were Japanese torpedoes, the Japanese - that two 37-mm shells fired by the “Korean”. And only recently, as Japanese reports were published, it became obvious that the Japanese still shot first, but who cares about this today, except for a few history buffs? But if the “Varyag” had opened fire on the Japanese ships entering the roadstead, it, in the eyes of “the entire civilized world,” would have been the first to violate Korean neutrality - whatever one may say, but at that time the Japanese had not yet started landing troops and did nothing reprehensible on a neutral roadstead.

In addition, tactically, the Russian stationary soldiers were in a completely hopeless position - they were standing in the roadstead under the guns of Japanese ships and could be sunk by destroyers at any moment. So, not only did opening fire on the Japanese directly violate all V.F. Rudnev's orders violated Korean neutrality, spoiled relations with England, France, Italy and the USA, and also did not give anything in military terms, leading only to the quick death of two Russian ships. Of course, there could be no talk of any destruction of the landing force here - it was purely technically impossible.

In diplomatic terms, the following happened. The honor of the Russian flag obliged the Varyag to come to the defense of any domestic ship or vessel that was attacked and to protect its crew (to fight with them) against any and no matter how superior enemy forces. But no concept of honor required the Varyag to engage in battle with the Japanese squadron after the incident with the Korean was successfully resolved (the Russian sailors were not injured, and they were no longer in immediate danger). An attack by Japanese destroyers, without a doubt, could have become a casus belli, that is, a formal reason for declaring war, but, of course, such a decision should not have been made by the commander of the Russian cruiser, but by much higher authorities. In such situations, the duty of any representative of the armed forces is not to rush into the attack with a sword at the ready, but to inform his superiors about the circumstances that have arisen and then act according to their orders. We have already said that all the orders that V.F. received. Rudnev directly testified that Russia does not want war yet. At the same time, an “amateur” attack by the Japanese squadron would only lead to providing Japan with an excellent excuse to enter the war at a time convenient for it, to the immediate destruction of two Russian warships with virtually no opportunity to harm the enemy, and to diplomatic complications with European countries.

The concept of honor is extremely important for a military man, but it is equally important to understand the boundaries of the obligations it imposes. For example, it is known that during the Second World War, when the USSR was bleeding in the fight against Nazi Germany, the armed forces of Japan more than once or twice carried out various kinds of provocations, which could well have become a reason for declaring war. But the USSR did not need a war on two fronts at all, so our armed forces were forced to endure, although, one must think, the troops present during such provocations were openly “itching” to respond to the samurai the way they deserved. Can our troops and navy be accused of cowardice or lack of honor on the grounds that they did not open fire in response to Japanese provocations? Do they deserve such reproaches? Obviously, no, and in the same way Vsevolod Fedorovich Rudnev does not deserve to be reproached for the fact that on January 26, 1904, the ships under his command did not engage in a hopeless battle with the Japanese squadron.

To be continued...

Ctrl Enter

Noticed osh Y bku Select text and click Ctrl+Enter

Cruiser "Varyag". During the Soviet era, there would hardly have been a person in our country who had never heard of this ship. For many generations of our compatriots, the Varyag became a symbol of the heroism and dedication of Russian sailors in battle.

However, perestroika, glasnost and the “wild 90s” that followed came. Ours has been subject to revision by all and sundry, and throwing mud at it has become a fashionable trend. Of course, “Varyag” also got it, and in full. His crew and commander were accused of everything! It was already agreed that Vsevolod Fedorovich Rudnev deliberately (!) sank the cruiser where it could be easily raised, for which he subsequently received a Japanese order. But on the other hand, many sources of information have appeared that were not previously available to historians and lovers of naval history - perhaps their study can really make adjustments to the history of the heroic cruiser, familiar to us from childhood?

This series of articles, of course, will not dot all the i's. But we will try to bring together information about the history of the design, construction and service of the cruiser up to and including Chemulpo, based on the data available to us, we will analyze the technical condition of the ship and the training of its crew, possible breakthrough options and various scenarios of action in battle. We will try to figure out why the commander of the cruiser, Vsevolod Fedorovich Rudnev, made certain decisions. In light of the above, we will analyze the postulates of the official version of the Varyag battle, as well as the arguments of its opponents. Of course, the author of this series of articles has formed a certain view of the feat of the “Varyag”, and it will, of course, be presented. But the author sees his task not in persuading the reader to any point of view, but in giving maximum information, on the basis of which everyone can decide for himself what the actions of the commander and crew of the cruiser "Varyag" are for him - a reason be proud of the fleet and your country, a shameful page in our history, or something else.

Well, we’ll start with a description of where such an unusual type of warship came from in Russia, such as high-speed armored cruisers of the 1st rank with a normal displacement of 6-7 thousand tons.

The ancestors of the armored cruisers of the Russian Imperial Navy can be considered the armored corvettes “Vityaz” and “Rynda” with a normal displacement of 3,508 tons, built in 1886.

Three years later, the Russian fleet was replenished with a larger armored cruiser with a displacement of 5,880 tons - it was the Admiral Kornilov, ordered in France, the construction of which began at the Loire shipyard (Saint-Nazaire) in 1886. However, then there was a slowdown in the construction of armored cruisers in Russia a long pause - almost a decade, from 1886 to 1895, the Russian Imperial Navy did not order a single ship of this class. Yes, and the Svetlana (with a displacement of 3828 tons), laid down at the end of 1895 at the French shipyards, although it was a quite decent small armored cruiser for its time, was still built rather as a representative yacht for the admiral general, and not as a ship , corresponding to the doctrine of the fleet. “Svetlana” did not fully meet the requirements for this class of warships by Russian sailors, and therefore was built in a single copy and was not replicated at domestic shipyards.

What, strictly speaking, were the fleet’s requirements for armored cruisers?

The fact is that the Russian Empire in the period 1890-1895. began seriously strengthening its Baltic Fleet with squadron battleships. Before this, in 1883 and 1886. two “battleships-rams” “Emperor Alexander II” and “Emperor Nicholas I” were laid down, and then only in 1889 - “Navarin”. Very slowly - one armadillo every three years. But in 1891 the Sisoy the Great was laid down, in 1892 - three squadron battleships of the Sevastopol type, and in 1895 - Peresvet and Oslyabya. And this is not even counting the laying of three coastal defense battleships of the Admiral Senyavin type, from which, in addition to traditional solutions to problems for this class of ships, they were also expected to support the main forces in the general battle with the German fleet.

In other words, the Russian fleet sought to create armored squadrons for a general battle, and of course, such squadrons required ships to support their operations. In other words, the Russian Imperial Navy needed reconnaissance officers attached to the squadrons - it was precisely this role that armored cruisers could quite successfully perform.

However, here, alas, dualism had its say, which largely predetermined the development of our fleet at the end of the 19th century. When creating the Baltic Fleet, Russia wanted to get a classic “two in one”. On the one hand, forces were required that were capable of giving a general battle to the German fleet and establishing dominance in the Baltic. On the other hand, they needed a fleet capable of entering the ocean and threatening British communications. These tasks were completely contradictory to each other, since their solution required different types of ships: for example, the armored cruiser Rurik was excellent for ocean raiding, but was completely inappropriate in a linear battle. Strictly speaking, Russia needed a battle fleet to dominate the Baltic and, separately, a second cruising fleet for war in the ocean, but, of course, the Russian Empire could not build two fleets, if only for economic reasons. Hence the desire to create ships capable of equally effectively fighting enemy squadrons and cruising in the ocean: a similar trend affected even the main strength of the fleet (the Peresvet series of “battleship cruisers”), so it would be strange to think that armored cruisers would not be supplied similar task.

As a matter of fact, this is exactly how the requirements for the domestic armored cruiser were determined. He was supposed to become a scout for the squadron, but also a ship suitable for ocean cruising.

Russian admirals and shipbuilders at that time did not at all consider themselves “ahead of the rest”, therefore, when creating a new type of ship, they paid close attention to ships of a similar purpose, built by the “Mistress of the Seas” - England. What happened in England? In 1888-1895. Foggy Albion built a large number of 1st and 2nd class armored cruisers.

At the same time, 1st class ships, strange as it may sound, were the “successors” of the Orlando-class armored cruisers. The fact is that these armored cruisers, according to the British, did not live up to the hopes placed on them; due to overload, their armor belt went under the water, thereby not protecting the waterline from damage, and in addition, in England, William took the post of chief builder White, opponent of armored cruisers. Therefore, instead of improving this class of ships, England in 1888 began building large armored cruisers of the 1st rank, the first of which were the Blake and Blenheim - huge ships with a displacement of 9150-9260 tons, carrying a very powerful armored deck (76 mm, and on bevels - 152 mm), strong weapons (2 * 234 mm, 10 * 152 mm, 16 * 47 mm) and developing a very high speed for that time (up to 22 knots).

Armored cruiser "Blake"

However, these ships seemed to their lordships to be excessively expensive, so the next series of 8 cruisers of the Edgar type, which entered the stocks in 1889-1890, was smaller in displacement (7467-7820 tons), speed (18.5/20 knots at natural /forced traction) and armor (the thickness of the bevels decreased from 152 to 127 mm).

All these ships were formidable fighters, but they, in fact, were cruisers not for squadron service, but for the protection of ocean communications, that is, they were “defenders of trade” and “raider killers,” and as such, were not very suitable for the Russian fleet. In addition, their development led the British to a dead end - in an effort to create ships capable of intercepting and destroying armored cruisers of the Rurik and Rossiya type, the British in 1895 laid down the armored deck Powerful and Terrible, which had a total displacement of over 14 thousand. etc. The creation of ships of this size (and cost), without vertical armor protection, was obvious nonsense.

Therefore, the analogues for the newest Russian armored cruisers were considered to be the English 2nd class cruisers, which had similar functionality, that is, they could serve with squadrons and perform overseas service.

Since 1889-1890 Great Britain laid down as many as 22 Apollo-class armored cruisers, built in two subseries. The first 11 ships of this type had a displacement of about 3,400 tons and did not carry copper-wood plating of the underwater part, which slowed down the fouling of ships, while their speed was 18.5 knots with natural draft and 20 knots when boosting the boilers. The next 11 Apollo-class cruisers had copper-wood plating, which increased their displacement to 3,600 tons, and reduced their speed (natural thrust/boosted) to 18/19.75 knots respectively. The armor and armament of the cruisers of both subseries was the same - an armored deck with a thickness of 31.75-50.8 mm, 2 * 152 mm, 6 * 120 mm, 8 * 57 mm, 1 * 47 mm guns and four 356 mm torpedo tubes apparatus.

The next armored cruisers of the British, 8 ships of the Astraea type, laid down in 1891-1893, became a development of the Apollo, and, in the opinion of the British themselves, not a very successful development. Their displacement increased by almost 1,000 tons, reaching 4,360 tons, but the additional weight was spent on subtle improvements - the armor remained at the same level, the armament “increased” by only 2 * 120 mm guns, and the speed decreased further, amounting to 18 knots with natural thrust and 19.5 knots with forced thrust. However, they served as the prototype for the creation of a new series of British 2nd class armored cruisers.

In 1893-1895. The British are laying down 9 cruisers of the Eclipse type, which we called the “Talbot type” (the same “Talbot” that served as a stationary on the Chemulpo roadstead along with the cruiser “Varyag”). These were much larger ships, the normal displacement of which reached 5,600 tons. They were protected by a somewhat more solid armored deck (38-76 mm) and they carried more solid weapons - 5 * 152 mm, 6 * 120 mm, 8 * 76- mm and 6*47 mm guns, as well as 3*457 mm torpedo tubes. At the same time, the speed of the Eclipse-class cruisers was frankly modest - 18.5/19.5 knots with natural/forced thrust.

So, what conclusions did our admirals draw from observing the development of the armored cruiser class in the UK?

Initially, a competition was announced for the cruiser project, and exclusively among domestic designers. They were asked to present designs for a ship with a displacement of up to 8,000 tons and a speed of at least 19 knots. and artillery, which included 2*203 mm (at the extremities) and 8*120 mm guns. Such a cruiser for those years looked excessively large and strong for a reconnaissance officer attached to a squadron; one can only assume that the admirals, knowing the characteristics of the English 1st class armored cruisers, were thinking about a ship capable of resisting them in battle. But, despite the fact that during the 1894-1895 The competition resulted in very interesting projects (7,200 - 8,000 tons, 19 knots, 2-3*203 mm guns and up to 9*120 mm guns), they did not receive further development: it was decided to focus on British armored cruisers 2 -th rank.

At the same time, it was initially planned to focus on Astraea-class cruisers, with the obligatory achievement of 20 knot speeds and “a possibly larger area of operation.” However, almost immediately a different proposal arose: the engineers of the Baltic Shipyard presented MTK with preliminary studies of designs for cruisers with a displacement of 4,400, 4,700 and 5,600 tons. All of them had a speed of 20 knots and an armored deck 63.5 mm thick, only the armament differed - 2 * 152- mm and 8*120 mm on the first, 2*203 mm and 8*120 mm on the second and 2*203 mm, 4*152 mm, 6*120 mm on the third. A note accompanying the drafts explained:

“The Baltic Shipyard deviated from the English cruiser Astrea prescribed as an analogue, since it does not represent the most advantageous type among other new cruisers of different nations.”

Then the Eclipse-class cruisers were chosen as a “role model”, but then data became known about the French armored cruiser D'Entrecasteaux (7,995 tons, armament 2 * 240 mm in single-gun turrets and 12 * 138 mm , speed 19.2 knots). As a result, a new cruiser design was proposed with a displacement of 6,000 tons, a speed of 20 knots and armament of 2 * 203 mm and 8 * 152 mm. Alas, soon, by the will of the Admiral General, the ship lost its 203-mm guns for the sake of uniformity of calibers and... thus began the history of the creation of domestic armored cruisers of the Diana type.

It must be said that the design of this series of domestic cruisers has become an excellent illustration of where the road paved with good intentions leads. In theory, the Russian Imperial Navy was supposed to receive a series of excellent armored cruisers, superior to the British ones in many respects. The armored deck of a single 63.5 mm thickness provided at least equivalent protection to the English 38-76 mm. Ten 152-mm guns were preferable to the 5*152-mm, 6*120-mm English ship. At the same time, “Diana” was supposed to become significantly faster than “Eclipse” and this was the point.

Tests of warships of the Russian fleet did not include boosting the boilers; Russian ships had to show the contract speed using natural thrust. This is a very important point, which is usually missed by the compilers of ship personnel directories (and, alas, by the readers of these directories). So, for example, data is usually given that the Eclipse developed 19.5 knots, and this is true, but it is not indicated that this speed was achieved by boosting the boilers. At the same time, the contract speed of the Diana is only half a knot higher than that of the Eclipse, and in fact, cruisers of this type were only able to develop 19-19.2 knots. From this we can assume that the Russian cruisers turned out to be even less fast than their English “prototype”. But in fact, the “goddesses” developed their 19 knots of speed on natural thrust, at which the speed of the “Eclipses” was only 18.5 knots, that is, our cruisers, with all their shortcomings, were still faster.

However, let's return to the Diana project. As we said earlier, their protection was expected to be no worse, their artillery better, and their speed one and a half knots greater than that of the British Eclipse-class cruisers, but that was not all. The fact is that the Eclipses had fire-tube boilers, while the Dianas were planned to have water-tube boilers, and this gave our ships a number of advantages. The fact is that fire tube boilers require much more time for distributing vapors, it is much more difficult to change operating modes on them, and this is important for warships, and in addition, flooding a compartment with a working fire tube boiler would most likely lead to its explosion, which threatened the ship with immediate destruction (as opposed to the flooding of one compartment). Water tube boilers were free of these disadvantages.

The Russian fleet was one of the first to switch to water tube boilers. Based on the results of research by specialists from the Naval Department, it was decided to use boilers designed by Belleville, and the first tests of these boilers (the armored frigate Minin was converted in 1887) showed quite acceptable technical and operational characteristics. It was believed that these boilers were extremely reliable, and the fact that they were very heavy was perceived as an inevitable price to pay for other advantages. In other words, the Navy Department realized that there were boilers of other systems in the world, including those that could provide the same power at significantly less weight than the Belleville boilers, but all this had not been tested and therefore raised doubts. Accordingly, when creating armored cruisers of the Diana type, the requirement to install Belleville boilers was completely categorical.

However, heavy boilers are not at all the best choice for a high-speed (even relatively high-speed) armored cruiser. The weight of the “Dian” machines and mechanisms amounted to an absolutely absurd 24.06% of their normal displacement! Even the later-built Novik, which many spoke of as a “destroyer weighing 3,000 tons” and a “case for cars,” whose combat qualities were obviously sacrificed for speed - and its weight of cars and boilers was only only 21.65% of normal displacement!

The Diana-class armored cruisers in their final version had 6,731 tons of normal displacement, developed 19-19.2 knots and carried an armament of only eight 152 mm guns. Without a doubt, they turned out to be extremely unsuccessful ships. But it’s hard to blame the ship’s designers for this - the supermassive power plant simply did not leave them enough room to achieve the rest of the planned characteristics of the ship. Of course, the existing boilers and engines were not suitable for a high-speed cruiser, and even the admirals “distinguished themselves” by authorizing the weakening of the already weak weapons for the sake of saving a penny on the scales. And, what’s most offensive, all the sacrifices that were made for the power plant did not make the ship fast. Yes, despite not reaching the contract speed, they were, perhaps, still faster than the British Eclipses. But the problem was that the “Mistress of the Seas” did not often build really good ships (the British were just good at fighting with them), and the armored cruisers of this series certainly could not be called successful. Strictly speaking, neither the 18.5 Eclipse nodes nor the 20 contract Diana nodes in the second half of the 90s of the 19th century were sufficient to serve as a reconnaissance unit for the squadron. And the armament of eight openly standing six-inch guns looked simply ridiculous against the background of two 210-mm and eight 150-mm cannons located in the casemates and turrets of the German armored cruisers of the Victoria Louise type - these are the cruisers that the Dianas would have to fight with in the Baltic in in case of war with Germany...

In other words, the attempt to create an armored cruiser capable of performing the functions of a scout for a squadron and, at the same time, “pirating” in the ocean in the event of a war with England, was a fiasco. Moreover, the inadequacy of their characteristics was clear even before the cruisers entered service.

The Diana-class cruisers were laid down (officially) in 1897. A year later, a new shipbuilding program was developed, taking into account the threat of a sharp strengthening of Japan: it was planned, to the detriment of the Baltic Fleet (and while maintaining the pace of construction of the Black Sea), to create a strong Pacific Fleet capable of neutralizing the emerging Japanese naval power. At the same time, the MTK (under the leadership of the Admiral General) determined the technical specifications for four classes of ships: squadron battleships with a displacement of about 13,000 tons, reconnaissance cruisers of the 1st rank with a displacement of 6,000 tons, “messenger ships” or cruisers of the 2nd class with a displacement of 3,000 tons and destroyers 350 tons.

In terms of creating armored cruisers of the 1st rank, the Maritime Department took a rather logical and reasonable step - since the creation of such ships on its own did not lead to success, it means that an international competition should be announced and the lead ship should be ordered abroad, and then replicated in domestic shipyards, thereby strengthening the fleet and acquiring advanced shipbuilding experience. Therefore, the competition put forward significantly higher tactical and technical characteristics than those of the Diana-class cruisers - MTK formed an assignment for a ship with a displacement of 6,000 tons, a speed of 23 knots and an armament of twelve 152-mm and the same number of 75-mm mm guns. The thickness of the armored deck was not specified (of course, it had to be present, but the rest was left to the discretion of the designers). The conning tower was supposed to have 152 mm armor, and the vertical protection of the elevators (feeding ammunition to the guns) and the bases of the chimneys was 38 mm. The coal reserve had to be at least 12% of the normal displacement, the cruising range was not less than 5,000 nautical miles. The metacentric height was also set with a full supply of coal (no more than 0.76 m), but the main dimensions of the ship were left to the discretion of the competitors. And yes, our specialists continued to insist on using Belleville boilers.

As you can see, this time MTK did not focus on any of the existing ships of other fleets of the world, but sought to create a very powerful and fast cruiser of moderate displacement that had no direct analogues. When determining the performance characteristics, it was considered necessary to ensure superiority over the Elswick cruisers: as follows from the “Report on the Naval Department for 1897-1900,” domestic armored cruisers of the 1st rank were to be built: “like Armstrong’s fast cruisers, but superior their displacement (6000 tons instead of 4000 tons), speed (23 knots instead of 22) and the test duration at full speed increased to 12 hours.” At the same time, the armament of 12 rapid-firing 152-mm cannons guaranteed it superiority over any English or Japanese armored cruiser of similar or smaller displacement, and its speed allowed it to escape from larger and better armed ships of the same class (“Edgar”, “Powerfull”, “ D'Entrecasteaux”, etc.)

As a matter of fact, this is how the story of the creation of the cruiser “Varyag” begins. And here, dear readers, a question may arise - why was it necessary to write such a long introduction, instead of immediately getting to the point? The answer is very simple.

As we know, a competition for designs for armored cruisers of the 1st rank took place in 1898. It seemed that everything should have gone as planned - many proposals from foreign companies, selection of the best project, its modification, contract, construction... No matter how it goes! Instead of the boring routine of a well-established process, the creation of “Varyag” turned into a real detective story. Which began with the fact that the contract for the design and construction of this cruiser was signed even before the competition. Moreover, at the time of signing the contract for the construction of the Varyag, no cruiser project yet existed in nature!

The fact is that soon after the competition was announced, the head of the American shipbuilding company William Crump and Sons, Mr. Charles Crump, arrived in Russia. He did not bring any projects with him, but he undertook to build the best warships in the world at the most reasonable price, including two squadron battleships, four armored cruisers with a displacement of 6,000 tons and 2,500 tons, as well as 30 destroyers. In addition to the above, Charles Crump was ready to build a plant in Port Arthur or Vladivostok, where 20 destroyers from the above 30 were to be assembled.

Of course, no one gave such a “piece of the pie” to Ch. Crump, but on April 11, 1898, that is, even before the competitive designs of armored cruisers were considered by the MTK, the head of the American company, on the one hand, and Vice Admiral V.P. Verkhovsky (head of GUKiS), on the other hand, signed a contract for the construction of a cruiser, which later became the Varyag. At the same time, there was no design for the cruiser - it still had to be developed in accordance with the “Preliminary Specifications”, which became an annex to the contract.

In other words, instead of waiting for the project to be developed, reviewing it, making adjustments and changes, as has always been done, and only then signing a construction contract, the Maritime Department, in fact, bought a “pig in a poke” - it signed a contract that provided development of a cruiser project by Ch. Crump based on the most general technical specifications. How did Ch. Crump convince V.P. Verkhovsky that he is capable of developing the best project of all that will be submitted to the competition, and that the contract should be signed as quickly as possible so as not to waste precious time?

Frankly speaking, all of the above indicates either some kind of childish naivety of Vice Admiral V.P. Verkhovsky, or about the fantastic gift of persuasion (on the verge of magnetism) that Ch. Crump possessed, but most of all it makes you think about the existence of a certain corrupt component of the contract. It is very likely that some of the arguments of the resourceful American industrialist were extremely weighty (for any bank account) and could rustle pleasantly in the hands. But... not caught - not a thief.

Be that as it may, the contract was signed. On what happened next... let's just say, there are polar points of view, ranging from “the brilliant industrialist Crump, with difficulty making his way through the bureaucracy of Tsarist Russia, builds a first-class cruiser of breathtaking qualities” and to “the scoundrel and swindler Crump tricked and bribed the Russian Imperial Navy a completely worthless ship." So, in order to understand, as impartially as possible, the events that happened more than 100 years ago, the dear reader must imagine the history of the development of armored cruisers in the Russian Empire, at least in the very shortened form in which it was presented in this article .

To be continued...

There is hardly a single person who has not heard about the Russian cruiser Varyag, which entered into an unequal battle with the Japanese squadron. For a long time it was believed that the crews of the cruiser “Varyag” and the gunboat “Koreets” showed their best qualities in this battle, becoming the personification of professionalism, fearlessness and self-sacrifice. Much later, already in our time, another version began to be heard more and more often, according to which the commander of the “Varyag”, captain 1st rank V.F. Rudnev, is considered almost a traitor. What happened on February 9, 1904 in the Korean port of Chemulpo?

Chemulpo on the eve of the war

The port of Chemulpo (currently Incheon) is located on the west coast of Korea on the shores of the Yellow Sea. The location of the port, just 30 km from Seoul, made it an important strategic object, so warships of countries that had their own interests in Korea were constantly present at the roadstead. There were also Russian ships in Chemulpo, as well as coal warehouses with fuel reserves for the Russian Pacific squadron.

On January 12, 1904 (all dates are given according to the new style), the 1st rank cruiser “Varyag” arrived from Port Arthur to Chemulpo to replace the cruiser “Boyarin” that had previously been there. The Varyag was commanded by Captain 1st Rank Vsevolod Fedorovich Rudnev. On January 5, he was joined by the gunboat "Koreets" under the command of captain 2nd rank Grigory Pavlovich Belyaev. From now on, these two ships were subordinate to the Russian ambassador in Seoul - actual state councilor Alexander Ivanovich Pavlov.

Heading1

Heading2

The cruiser "Varyag" in June 1901

Source: kreiser.unoforum.pro

Gunboat "Korean" in the Nagasaki roadstead

Gunboat "Korean" in the Nagasaki roadstead

Source: navsource.narod.ru

In addition to the Varyag and the Korean, the English 2nd-class cruiser Talbot (under the command of Commodore L. Bailey, arrived in Chemulpo on January 9), the French 2nd-class cruiser Pascal (commander – captain 2nd rank V. Sene), Italian cruiser 2nd class “Elba” (commander – captain 1st rank R. Borea), American gunboat “Vicksburg” (commander – captain 2nd rank A. Marshall) and the Japanese cruiser "Chiyoda" (commander - Captain 1st Rank K. Murakami). Despite the difficult international situation, friendly relations were quickly established between the ship commanders. Despite outward manifestations of friendliness, already from January 16 at the Chemulpo radiotelegraph station, in accordance with the directive of the Ministry of Communications of Japan, they began to delay the dispatch of international telegrams for up to 72 hours.

On January 21, the “Korean” went on reconnaissance to Asanman Bay to check the information received by Pavlov about the presence of a large detachment of Japanese ships in the bay. The information turned out to be false, and in the evening of the same day the gunboat returned to Chemulpo. Her sudden disappearance caused a great commotion on board the Japanese cruiser, and the naval agent of the Japanese mission was literally knocked off his feet, looking for the “Korean”. In the evening of the same day, a dinner was held on board the Chiyoda, to which the commanders of all the stationers on duty at the port were invited. The Japanese commander made every possible diplomatic effort to assure those present that his country was filled with the most peaceful intentions.

Armored cruiser Chiyoda

Armored cruiser Chiyoda

Source: tsushima.su

In the second half of January, the situation at the roadstead changed dramatically. The Japanese community of Chemulpo began to build food warehouses, communication points and barracks on the shore. A large amount of cargo was transported from transports to the shore, which was immediately stored at new storage points. On the Chiyoda, with the onset of darkness, the guns were deployed into a firing position; servants were on duty at the guns, fully prepared to immediately open fire. Torpedo tubes were also brought into combat position. It should be noted that the commander of the Japanese cruiser drew up a plan for a surprise attack on Russian ships with torpedoes and artillery right in the roadstead, without waiting for a declaration of war. Only a direct order from the Japanese Navy Minister not to show aggression towards Russian ships before the start of hostilities stopped Captain Murakami from implementing this plan.

Meanwhile, on February 5, telegraph communication between Chemulpo and Port Arthur was completely interrupted. The next day, rumors appeared about the severance of diplomatic relations between Japan and Russia. This was true, but Russian sailors and diplomats in Chemulpo could not contact their superiors to confirm this information and receive new instructions. However, on February 7, Rudnev invited Pavlov, along with other embassy employees, to immediately leave Seoul on the Varyag and Koreyets - without the appropriate permission from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Pavlov rejected this very reasonable offer. Rudnev himself was bound by the governor’s instructions not to leave Chemulpo under any circumstances without orders and could not do anything on his own.

On the night of February 7-8, unexpectedly for everyone, the Chiyoda weighed anchor, left the port and moved out to sea to join the 4th Combat Detachment, which was already approaching Chemulpo. The disappearance of the Japanese cruiser finally prompted the Russian ambassador to compose a dispatch to the governor and send it to Port Arthur aboard the Korean. However, the favorable time for leaving had already been missed; the port of Chemulpo was blocked by a Japanese squadron approaching from the sea.

Composition of the Japanese squadron

On February 6, a Japanese transport detachment consisting of the Dairen-maru and Otaru-maru transports, carrying 2,252 people from the 12th Infantry Division, left the port of Sasebo. The detachment's goal was the port of Chemulpo, where the landing was to take place. To guard the transports, the 4th Combat Detachment was assigned under the command of Rear Admiral Uriu Sotokichi. Under his command were the armored cruisers Naniwa (flagship), Takachiho, Akashi and Niitaka. To strengthen the detachment, they were temporarily given the armored cruiser Asama.

Armored cruiser "Asama"

Armored cruiser "Asama"

Source: tsushima.su

On February 7, the 9th (Aotaka, Hato, Kari and Tsubame) and 14th (Hayabusa, Chidori, Manazuru and Kasasagi) destroyer detachments and transports joined the detachment "Kasuga-maru" and "Kinshu-maru". On February 8, the detachment approached Chemulpo directly, where it met the cruiser Chiyoda, which came out to meet it. Next, according to the plan, a landing was to take place in the port, but unexpectedly for itself, the Japanese squadron met with the “Korean”, which led to an incident during which the first shots of the Russo-Japanese War were fired.

The first shots of the war. Attack on "Korean"

Having received a dispatch from the governor on board, on February 8 at 15:40, the “Korean” weighed anchor and set off for Port Arthur. Soon after leaving the Korean, a Japanese squadron was discovered, moving in full force towards Chemulpo. The Japanese marched in two columns: on the right - cruisers and transports, on the left - the destroyers Aotaka, Hato, Kari and Tsubame (9th destroyer detachment). A corresponding signal was immediately sent to the Varyag about the appearance of the Japanese.

Since hostilities between the two countries had not yet begun, both sides tried to disperse on a narrow fairway. The “Korean” moved to the right, leaving room for the Japanese squadron to pass. The Japanese transports also evaded to the right, and "Asama", on the contrary, having left the column and turned 1800, took up a position between the "Korean" and the transports. The Japanese admiral could not know Belyaev's intentions and tried to protect the landing ships from a possible attack from the Russians. Later, Belyaev would write in a report that the Asama blocked the path of the Korean, but the path to the sea remained open for the Russian ship. The guns on the Japanese ships were uncovered and deployed in the direction of a possible enemy.

Meanwhile, the commander of the 9th destroyer detachment, Yashima Djunkichi, after his ships passed on the left side of the Korean, turned them on the opposite course and began pursuit. This was done so that at the slightest threat to the transports from the “Korean”, they would immediately attack it. The destroyers split up: “Hato” and “Aotaka” ended up on the left side of the “Korean”, “Kari” and “Tsubame” on the right, but when turning, the “Tsubame” ran into a rocky shoal, damaging the propellers. The torpedo tubes on the Japanese ships were loaded and deployed towards the enemy.

Considering such maneuvers as a signal that the Japanese did not want to release the “Korean” from Chemulpo, Belyaev began to turn his ship to the right, on the opposite course. At that moment, a torpedo was fired from the destroyer "Kari" at the "Koreyets", passing astern at a distance of 12-13 m. The clock was 16:35. "Hato" and "Aotaka" also began to turn to the right after the "Korean", which sounded the combat alarm. The Hato also fired a torpedo, which also passed behind the stern of the Russian gunboat. At this moment, several shots were fired from the 37-mm Koreyets cannons; no hits were recorded. Belyaev’s report also speaks of a third torpedo, which went directly to the starboard side of the “Koreyets”, but for some unknown reason sank before reaching the target a few meters. The logbook of the "Korean" speaks of only two fired torpedoes, the same is stated in the Japanese report, so, apparently, a foam wake from a wave was mistaken for the wake of the third torpedo, which often happens in a tense combat situation.

Soon after the first shots, the combat alarm was sounded on the Koreyets, as the boat was already entering neutral waters. Soon the "Korean" anchored in its place. Japanese ships also entered the roadstead and stood in close proximity to the Russian ships, which were immediately monitored closely.

The destroyer Hayabusa in Kobe, 1900. Destroyers of the 9th and 14th detachments belonged to ships of this type

The destroyer Hayabusa in Kobe, 1900. Destroyers of the 9th and 14th detachments belonged to ships of this type

Source: tsushima.su

It is worth noting that the commander of the Japanese destroyers did not receive an order to torpedo the Koreets - his main task was to ensure the safety of transport ships. Thus, launching torpedoes at the Korean was the personal initiative of the Japanese commander. Apparently, the Japanese were provoked by the fact that the “Korean” began to turn, thereby pinching the destroyer “Kari” between itself and the shore. It is also possible that the Japanese commander simply lost his nerve, and he considered the current situation the most favorable for launching an attack - it is now impossible to confirm or refute this version. It is only worth noting that if the “Korean” had not turned back to the roadstead and continued on its way to Port Arthur, the Japanese destroyers would have pursued and attacked it south of the island of Phalmido, at least this intention is stated in the report of the commander of 9- th detachment of destroyers.

There were no casualties as a result of this incident, although the Japanese side essentially lost one ship - the destroyer Tsubame, which damaged its propellers so much that it could not reach speeds above 12 knots.

Actions of the parties after the incident

Immediately upon arrival at the parking lot, Belyaev went aboard the Varyag, where he reported to Rudnev about what had happened. In turn, Rudnev went aboard the Talbot for clarification. The commander of the Talbot, as a senior officer in the roadstead, in turn, went aboard the Japanese cruiser Takachiho, where he was told that there had been no incident, attributing everything to a misunderstanding.

At about 17:00 in the evening, armed troops began landing on the shore from transports. Since there was no news of the outbreak of hostilities, the Russian sailors, in accordance with the instructions of the governor, did not take any action towards the Japanese ships and looked indifferently at the capture of the port. However, both ships had a watch at the guns, watertight bulkheads were battened down, and the crew was in full readiness for the start of hostilities. By evening, almost all the Japanese cruisers left the roadstead, anchoring near the island of Phalmido. During the entire landing, Japanese destroyers were on duty near the Russian ships in full readiness to attack them if they decided to interfere with the landing operation.

At 2:30 the landing was completed, and early in the morning the Japanese ships began to leave the roadstead. By 8:30, only the cruiser Chiyoda remained in Chemulpo - its commander in turn visited all the ships of the international squadron, handing them a notification of the start of the war between Japan and Russia. The letter reported a requirement for Russian ships to leave the port before 12 noon, otherwise at 16 o'clock they would be attacked right in the roadstead. After the notice was delivered to all foreign ships, the Japanese cruiser left the port.

The commander of the Varyag was warned about the Japanese ultimatum by the commander of the French cruiser Pascal, after which Rudnev informed Belyaev about the start of the war. Soon, a meeting of ship commanders (with the exception of the American one) was held on board the Talbot, at which it was decided that if the Russians did not leave the port, then foreign ships would leave the raid before 12 o’clock, so as not to suffer as a result of a possible battle. A protest was sent to the Japanese admiral against a possible attack by Russian ships in the roadstead, which he received a few minutes before the start of the battle. When Rudnev asked to accompany his ships until they left neutral waters, the commanders of the foreign cruisers refused, as this would violate their neutrality. Thus, Rudnev had only two options: go to sea and fight the Japanese squadron, or stay in the roadstead and take the fight there. Rudnev chose the first option, telling the commanders of the foreign ships that he would go to sea before noon. He had no right to sink or blow up his ship without a fight and receiving appropriate instructions from above. At the same time, on board the Talbot, Rudnev was finally given a Japanese notification of the outbreak of war, delivered through the consul.

At 10 o'clock Rudnev returned aboard the Varyag. A military council was held on the cruiser, at which the commander's decision to fight was unanimously approved by the officers. The commander of the “Korean” was not invited to the meeting and was not privy to Rudnev’s plans, but in battle he was given complete independence. In case of an unsuccessful breakthrough, it was decided to blow up the cruiser. On board the Korean, a similar council had already taken place earlier, after Belyaev’s return from the Varyag. At 11 o'clock the cruiser's crew was assembled on the quarterdeck, where Rudnev gave a speech, announcing the beginning of the war and that the cruiser was going to sea for a breakthrough. The crew greeted the captain's speech with great enthusiasm; the morale of the Russian sailors was very high. Before the battle, furniture and unnecessary wooden objects were thrown overboard from the ships, and improvised protection against shrapnel was installed. The topmasts of the Koreyets were cut down to prevent the enemy from accurately determining the distance in battle.

To break through to the open sea, Russian ships had to overcome a long and narrow winding channel about 2 cables wide and about 30 miles long. This channel was replete with shoals and underwater rocks and was considered difficult to navigate even in peacetime. The Japanese squadron occupied a tactically very advantageous position ahead of the Russian ships in a place where the fairway widened (about 10 miles from Chemulpo itself). Thus, “Varyag” and “Korean” should first get closer to the enemy under enemy fire, then, maintaining high speed, follow a parallel course for some time, ahead of the Japanese, and only after that go into the lead. Considering that the Asama alone was qualitatively superior to both Russian ships in both protection and armament, the task facing the Russian sailors was very difficult. It should be noted that the maximum speed of the Korean was 13 knots, so this ship could not have escaped even the slowest Japanese cruisers - Naniwa and Takachiho. Why Rudnev took him into the breakthrough remains a mystery. However, the acceleration of the movement of Russian ships could be facilitated by a strong ebb current, which could add another 2 to 4 knots to their own speed.

Battle

At 11:20 (11:55 Japanese time) “Varyag” and “Korean” began to weigh anchor. The weather was calm and the sea was completely calm. For some time, the “Korean” walked ahead, then took a place behind the “Varyag”. On their way, Russian ships passed by cruisers of neutral powers. The crew on them lined up along the sides, saluting the Russian sailors who, in their opinion, were heading to certain death. Soon the neutral ships remained astern, with the enemy waiting ahead.

“Varyag” and “Korean” go to battle

“Varyag” and “Korean” go to battle

Source: tsushima.su

The speed of the “Varyag” and “Korean” was gradually increased to 12 knots. At 11:25 (12:00) the combat alarm was sounded, the team took up positions according to the combat schedule. The entry of the Russian ships into the fairway came as a surprise to the Japanese - they were sure that the Varyag and the Koreets would remain in the roadstead, and were preparing to attack the enemy there. Despite the suddenness of the enemy's appearance, the Japanese confusion did not last long. A signal was raised on the mast of the cruiser Asama: "Russian ships go to sea". Hastily riveting the anchor chains, the Japanese squadron began moving towards the Russian ships. Closest to the Varyag were Asama and Chiyoda, which formed a separate detachment that maneuvered together. “Naniwa” and “Niitaka” also joined into a detachment that stayed behind and somewhat to the right of “Asama” and “Chiyoda”. The cruisers Akashi and Takachiho rushed in a southwestern direction to block the Russians' access to the sea. The destroyers of the 14th detachment "Hayabusa", "Chidori", "Manazuru" took only a formal part in the battle, all the time staying outside effective artillery fire.

Scheme of the battle of Chemulpo. Reconstruction by A.V. Polutov. The diagram shows Japanese time

Scheme of the battle of Chemulpo. Reconstruction by A.V. Polutov. The diagram shows Japanese time

Source: tsushima.su