The British Parliament is the oldest in the world. It originated in the 12th century as Witenagemot, the body of wise counsellors whom the King needed to consult pursuing his policy. The British Parliament consists of the House of Lords and the House of Commons and the Queen as its head. The House of Commons plays the major role in law-making. It consists of Members of Parliament (called MPs for short). Each of them represents an area in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland. MPs are elected either at a general election or at a by-election following the death or retirement. Parliamentary elections are held every 5 years and it is the Prime Minister who decides on the exact day of the election. The minimum voting age is 18. And the voting is taken by secret ballot. The election campaign lasts about 3 weeks, The British parliamentary system depends on political parties.

The party which wins the majority of seats forms the government and its leader usually becomes Prime Minister. The Prime Minister chooses about 20 MPs from his party to become the cabinet of ministers. Each minister is responsible for a particular area in the government. The second largest party becomes the official opposition with its own leader and "shadow cabinet". The leader of the opposition is a recognized post in the House of Commons.

The parliament and the monarch have different roles in the government and they only meet together on symbolic occasions, such as the coronation of a new monarch or the opening of the parliament.

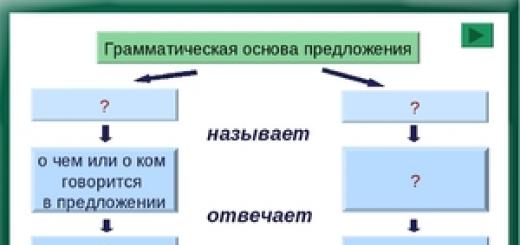

In reality, the House of Commons is the one of three which has true power. The House of Commons is made up of six hundred and fifty elected members, it is presided over by the speaker, a member acceptable to the whole house. MPs sit on two sides of the hall, one side for the governing party and the other for the opposition. The first 2 rows of seats are occupied by the leading members of both parties (called "front benches") The back benches belong to the rank-and-life MPs. Each session of the House of Commons lasts for 160-175 days. Parliament has intervals during his work. MPs are paid for their parliamentary work and have to attend the sittings. As it was mentioned above, the House of Commons plays the major role in law making. The procedure is the following: a proposed law ("a bill") has to go through three stages in order to become an act of parliament; these are called "readings".

The first reading is a formality and is simply the publication of the proposal. The second reading involves a debate on the principles of the bill; it is examination by parliamentary committee. And the third reading is a report stage, when the work of the committee is reported on to the house. This is usually the most important stage in the process. When the bill passes through the House of Commons, it is sent to the House of Lords for discussion, when the Lords agree it, the bill is taken to the Queen for royal assent, when the Queen sings the bill, it becomes act of the Parliament and the Law of the Land. The House of Lords has more than 1000 members, although only about 250 take an active part in the work in the house. Members of this Upper House are not elected, they sit there because of their rank, and the chairman of the House of Lords is the Lord Chancellor. And he sits on a special seat, called "WoolSack" The members of the House of Lords debate the bill after it has been passed by the House of Commons.

The barons did not want to fulfill the requirements of the knights, and King Henry III tried to use the contradictions between them. He obtained from the Pope a charter that freed him from all obligations to the discontented. And then in 1263 a civil war began. The army of the rebels consisted of knights, townspeople (artisans and merchants), students of Oxford University, free peasants and a number of barons who were dissatisfied with the existing order. The army of the rebels was led by Baron Simon de Montfort. London townspeople sent 15 thousand people to Montfort. The rebels took a number of cities (Gloucester, Bristol, Dover, Sandwich, etc.) and went to London. Henry III took refuge in Westminster. The royal army was commanded by the heir to the throne, Prince Edward. The army of the rebels approached the London suburb of Southwark. The townspeople rushed to the aid of Montfort, who was threatened with encirclement by Prince Edward, and the rebels entered the capital.

In May 1264, Montfort's army defeated the royal detachments (Battle of Lewes). The King and Prince Edward were captured by the rebels and forced to sign an agreement with them.

- On January 20, 1265, the first English Parliament met in Westminster. In addition to the barons, supporters of Montfort, and the higher clergy, it included two knights from each county and two citizens from each major city in England. Thus, in the course of the civil war, estate representation arose. True, it was mainly representatives of the city's upper classes who passed from the cities to parliament, but on the whole, the entry into the political arena of the townspeople and chivalry was of great importance. Peasants played a significant role during the war. It was this circumstance that frightened the barons, supporters of Montfort, and they began to move into the camp of the king.

- On August 4, 1265, the royal army defeated the army of Simon de Montfort (Battle of Ivzem). Montfort himself was killed. The struggle of disparate rebel groups continued until the autumn of 1267.

Henry III, who regained power, and then his successor Edward I did not destroy Parliament. It continued to exist, playing an increasing role, although in the early years of the reign of King Edward I, knights and burgesses were invited mainly to resolve the issue of taxes. For many of them, being in Parliament was a rather onerous and costly and inconvenient duty.

King Edward I (1272-1307) relied on class representation, however, of a narrow composition, in which he found a good counterbalance to the claims of the secular and spiritual nobility. Active aggressive policy of the 80-90s of the XIII century. caused a severe need for money. The king's attempts to collect taxes without the consent of parliament gave rise to strong discontent among the townspeople and knights. The barons used the dissatisfaction with the increase in taxes, and in the 90s of the XIII century. again there was a threat of an armed uprising.

King Edward I convened in 1295 a parliament on the model of the parliament of 1265 ("Exemplary Parliament"), and in 1297 issued a "Confirmation of the charter" (the second version of the charter is called the statute "On the non-imposition of taxes"). This document stated that no tax would be levied without the consent of Parliament. The king recognized the right of estate representatives to approve taxes; this, however, did not mean that taxes could only be levied with the consent of the payers. The bulk of the English peasants and townspeople were not represented in Parliament: their consent did not matter. Taxes were voted only by knights, barons, clergy and wealthy citizens. It was easier for royalty to collect the tax voted by these estates than to raise money in other ways.

The social nature of the English parliament and its organization.

As already mentioned, in addition to the secular and spiritual lords, representatives of the chivalry and the urban elite sat in the English Parliament. England of that time was already characterized by a significant commonality of interests between the knights, who were passing over to the conduct of a commodity economy, and the upper strata of the urban population, a commonality that served as the basis for a strong union of these two estates.

At the end of the XIII century. the functions of Parliament have not yet been precisely defined. This happened only in the first half of the 14th century. In the 13th century, the competence of the parliament, which met once a year, and sometimes much less frequently, was reduced mainly to the fact that it approved taxes, was the highest judicial body and had deliberative rights. The structure of the parliament in the XIII century. was also extremely uncertain; there was still no division into two chambers, although the special position of the nobility, secular and spiritual, was already clearly felt: they were invited to the session of parliament by the letters of the king, while the knights and townspeople were summoned through the sheriffs; in addition, the knights and townspeople did not take part in the discussion of all issues. In the first half of the XIV century. Parliament was divided into two chambers: the House of Lords, in which the higher clergy and secular nobility were represented, who received seats in the chamber by inheritance along with the title, and the House of Commons, in which both the knights of the counties and the city were represented, which was a feature of the English estate representation compared to, for example, French (tri-chamber structure of the Estates General).

The historical significance of the creation of Parliament.

The emergence of class representation was of great importance in the process of growth centralized state.

With the advent of parliament in England, a new form of the feudal state was born - a caste-representative, or estate, monarchy, which is the most important and natural stage in the political development of the country, the development of the feudal state.

The English Parliament is one of the first class-representative institutions in Western Europe, which turned out to be the most viable of them. A number of features of British history contributed to the process of gradually strengthening the power of Parliament, its formation as a body that reflects the interests of the nation as a whole.

After the Norman Conquest in 1066

The English state no longer knew political fragmentation. Separatism was characteristic of the English nobility, however, for a number of reasons (non-compactness of feudal estates, the need to resist the conquered population, the island location of the state, etc.), it was expressed in the desire of the magnates not to isolate themselves from the central government, but to seize it. In the XII century. England experienced a long civil strife. As a result of a long political struggle, the rights of the Plantagenet dynasty prevailed, and its representative, Henry IF, became king. His younger son John,176 who succeeded the knight-king Richard the Lionheart in 1199,1 was not successful either in foreign or domestic policy. In an unsuccessful war, he lost the vast possessions that the English crown had in France. This was followed by his quarrel with Pope Innocent III177, as a result of which the king was forced to recognize himself as a vassal of the pope, extremely humiliating for England. This king was nicknamed Landless by his contemporaries.

Constant wars, the maintenance of the army and the growing bureaucracy required money. By forcing his subjects to pay for the greatly increased expenses of the state, the king violated all established norms and customs in relation to both cities and the nobility. The violation by the king of the norms of vassal relations, which connected him with the class of feudal lords, was especially painfully perceived.

It should be noted some features that distinguished the estate structure of English society: the extension of the king's senior rights to all feudal lords (in England, the classical principle of feudalism "the vassal of my vassal is not my vassal" did not work) and the openness of the "noble" class, which could include any landowner, having an annual income of 20 (20s of the XIII century) to 40 (from the beginning of the XIV century) pounds1. A special social group developed in the country, occupying an intermediate position between the feudal lords and the prosperous peasantry. This group, active both economically and politically, sought to expand its influence in the English state; over time, its number and importance increased.

Situation in the 10s of the XIII century. united all those dissatisfied with royal arbitrariness and failures in foreign policy. The opposition speech of the barons was supported by the chivalry and the townspeople. The opponents of John the Landless were united by the desire to limit royal arbitrariness, to force the king to rule in accordance with centuries-old traditions. The result of the internal political struggle was the movement of magnates, in fact, pursuing the goal of establishing a "baron oligarchy."

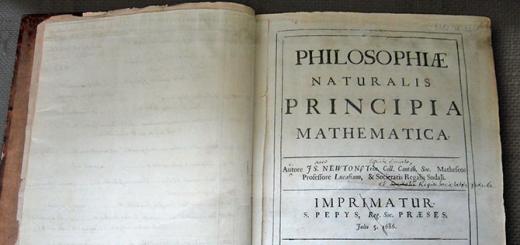

The program of the opposition's demands was formulated in a document that played an important role in the development of the estate-representative monarchy in England - the Magna Carta1. The magnates demanded from the king guarantees of respect for the rights and privileges of the nobility (a number of articles reflected the interests of chivalry and cities), and above all, the observance of an important principle: seniors cannot be taxed with money without their consent.

The role of the Charter in English history is ambiguous.

On the one hand, the full implementation of the requirements contained in it would lead to the triumph of the feudal oligarchy, the concentration of all power in the hands of the baronial group. On the other hand, the universality of the wording in a number of articles made it possible to use them to protect the rights of the individual not only of the barons, but also of other categories of the free population of England.

The King signed the Magna Carta on June 15, 1215, but refused to abide by it a few months later. The Pope also condemned this document.

In 1216, John the Landless died, power nominally passed to the infant Henry III178 - and for some time the system of state administration came into line with the requirements of the baronial elite. However, having reached adulthood, Henry III actually continued his father's policy. He got involved in new wars, and tried to get the necessary funds from his subjects through extortion and oppression. In addition, the king willingly accepted foreigners into the service (not the last role was played by the wishes of his wife, the French princess). The behavior of Henry III irritated the English nobility, but oppositional sentiments also grew in other classes. A broad coalition of those dissatisfied with the regime was made up of magnates, knights, part of the free peasantry, townspeople, and students. The dominant role belonged to the barons: "The conflicts between the barons and the king in the period from 1232 to 1258, as a rule, revolved around the question of power, again and again reviving plans for baronial control over the king, put forward as early as 1215"179. In the 5060s. 13th century England was engulfed in feudal anarchy. The armed detachments of the magnates fought with the troops of the king, and sometimes among themselves. The struggle for power was accompanied by the publication of legal documents in which new structures of state administration were established - representative bodies designed to limit royal power.

In 1258, Henry III was forced to accept the so-called "Oxford Provisions" (requirements), containing a mention of "Parliament"2. This term denoted the councils of the nobility, which were to be regularly convened to participate in the government of the country: “It must be remembered that ... there will be three parliaments in a year ... The elected advisers of the king will arrive at these three parliaments, even if they are not invited to consider the state of the kingdom and to interpret the general affairs of the kingdom and also of the king. And at other times in the same way, when there is a need by the command of the king.

Researchers note the presence of two currents in the movement of the baronial opposition in the mid-13th century. One sought to establish a regime of omnipotence for the magnates, the other sought to take into account the interests of its allies, and, consequently, objectively reflected the interests of the chivalry and the middle strata of the urban population1.

In the events of the civil war of 1258-1267. Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester played a significant role. In 1265, at the height of the confrontation with the king, at the initiative of Montfort, a meeting was convened, to which, in addition to the nobility, representatives of influential social groups were invited: two knights from each county and two deputies from the most significant cities. Thus, the ambitious politician sought to strengthen the social base of his “party”, to legitimize the measures taken by it to establish baronial guardianship over the monarch.

So, the origin of the national estate representation in England is closely connected with the struggle for power, the desire of the feudal nobility to find new methods of limiting the power of the really acting king. But it is unlikely that the parliament would have been viable if the matter had been limited to this. The institution of parliament opened up the possibility of political participation by cities and chivalry, and participation at a high, national level. It was implemented in the form of extended meetings under the king, consultations on topical issues (primarily in connection with taxes and other fees).

King John Landless signs the Magna Carta

"Gutnova E.V. The emergence of the English Parliament (from the history of English society and the state of the XIII century). - M., 1960. - S. 318.

2 Simonde Montfort, Count of Leicester (c. 1208-1265) - one of the leaders of the baronial opposition to King Henry III. A native of Provence (Southern France). Contributed to the drafting of the Oxford Provisions. May 14, 1264 at the Battle of Lewes (south of London) defeated the royal troops. Then, for 15 months, he was actually a dictator (formally the Seneschal of England). In 1265, on his initiative, the first English parliament was convened. August 4, 1265 was killed in battle.

Parliament was originally forced on the kings by the feudal oligarchy, but the monarchs recognized the possibility of using this structure to their advantage. Sometimes they put up with the opposition of the deputies, which manifested itself in legal, "parliamentary" forms.

In 1265, the royal power managed to restore the positions that seemed lost as a result of Montfort's speech. The rebellious count was defeated and died in battle. But already in 1267, Henry III again convened a parliament of “the most prudent people from the kingdom, great and small”180, and under the new king, Edward I, when the consequences of feudal unrest were finally overcome, the so-called “Exemplary Parliament” gathered » 1295 is one of the most representative years in its entire medieval history.

At the end of the XIII - beginning of the XIV century. parliament took a central place in the process of gradual formation of new principles for organizing relations between the royal power and society; the institution of parliament contributed to the fact that these relations acquired a more "legal" character.

The presence of a supreme representative structure was in the interests of all participants in the political process. With the formation of parliament, the king received a new and, what is essential, a legitimate tool for achieving his goals: first of all, for receiving monetary subsidies.

Parliament was passed by a majority of the magnates. The barons supported the idea of representation in it of chivalry, cities - a kind of "middle class" of feudal society. This is explained by the close connection of all estates on the basis of common economic interests. Excessive financial claims of the monarch impoverished the cities and "communities", which could not but affect the well-being of the lords. The lords positively accepted the innovation, which made it possible to set the limits for the monetary expenses of the royal administration, to limit the arbitrariness of the king in relation to his subjects in the collection of taxes, and, thereby, to introduce the practice of control over the activities of the authorities.

In addition, the middle and partly lower groups of the population were able to present their requests to the king through deputies and could count on their being heard.

The maxim of Roman law was used as the legal basis for such an order of relations between the authorities and subjects: “Quod omnes tangit, omnibus tractari et approbari debet” - “What concerns everyone, must be considered and approved by everyone.” In the Digest of Justinian, this legal formula determined the procedure for the group of guardians to act in the process of disposing of property. In the XII-XIII centuries. on its basis, in ecclesiastical law, a theory was created of restrictions imposed on the sole actions of ecclesiastical and secular rulers, taken without discussion and consent of their advisers and main subordinates. With regard to the organization of parliamentary representation, this maxim has been raised to the level of a constitutional principle.

The formation of a new political and legal ideology - the ideology of parliamentarism is reflected not only in the monuments of law of the 13th century, but also in secular literature. The events of 1265 are dedicated to the poem "The Battle of Lewes". In it, the author leads an imaginary dialogue between the king and the barons. The idea is instilled into the king that if he really loves his people, then he should report everything to his advisers and consult with them about everything, no matter how wise he may be. The poem justified the need for society to participate in the process of forming a circle of royal advisers: “The king cannot choose his own advisers. If he begins to choose them alone, he will easily make a mistake. Therefore, he needs to consult with the community of the kingdom and find out what the whole society thinks about it ... People who have arrived from the regions are not such idiots as not to know better than others the customs of their country, left by their ancestors to their descendants.

1295 became the starting point for regular and orderly parliamentary sessions. By the middle of the XIV century. There has been a division of parliament into two chambers - upper and lower. In the XVI century. the names of the chambers began to be used: for the upper - the House of Lords (the House of Lords), for the lower - the House of Commons (the House of Commons).

The upper chamber included representatives of the secular and ecclesiastical nobility, who were members until the 13th century. to the Grand Royal Council. These were peers of the kingdom, "great barons" and the highest officials of the king, church hierarchs (archbishops, bishops, abbots and priors of monasteries).

All members of the upper house received nominal calls to the session signed by the king. In theory, the monarch could not invite this or that magnate; in fact, cases when the heads of noble families were not invited to parliament became by the 15th century. rare. The system of case law prevailing in England gave the lord, who once received such an invitation, reason to consider himself a permanent member of the upper house. The number of persons involved, due to their social and legal status, in the activities of the chamber was small. The number of lords in the XIII-XIV centuries. ranged from 54 in the parliament of 1297 to 206 people in the parliament of 1306.184 In the XIV-XV centuries. the number of lords is stabilizing; during this period, it did not exceed 100 people, in addition, not all of the invitees arrived at the session.

At the initial stage of the existence of the parliament, it was the assembly of magnates that acted as an authoritative institution capable of influencing the kings, getting them to make the necessary decisions: “If the parliament had the opportunity to acquire a number of powers, this was due to the fact that in normal times the main role in belonged to the House of Lords."

Meeting of the House of Lords of the English Parliament during the time of Edward I (miniature of the beginning of the 16th century)

The traditional idea of the English Parliament as a "bicameral" assembly arose at a later time. Initially, the parliament acted as a single institution, but it included structures that differed in status, social composition, principles of formation, and requirements put forward. As we saw above, already in the first Parliament of Montfort, in addition to a group of magnates (lords), there were representatives of the counties (two "knights" from each county), cities (two representatives from the most significant settlements), as well as church districts (according to two "proctors" - deputy priests1).

The representation of the counties was initially recognized by both barons and kings. The situation was more complicated with deputies from the cities. Their constant participation in parliament is observed only from 1297.

In the XIII century. the structure of the parliament was unstable, there was a process of its formation. In some cases, all persons invited to participate in Parliament sat together. Then the practice of separate meetings of deputies began to take shape - by "chambers": magnates, representatives of the church, "knights", townspeople (for example, in 1283 the townspeople formed a separate meeting). "Knights" met both with the magnates and with the townspeople. "Chambers" could meet not only in different places, but also at different times.

In the first centuries of its existence, Parliament did not have a permanent meeting place. The king could summon him in any city; as a rule, it met in the place where the king and his court were located at a given time. As an example, we will indicate the locations of some parliaments of the late XIII - early XIV centuries: York - 1283, 1298, Shrewsbury - 1283, Westminster - 1295, Lincoln - 1301, Carlyle - 1307, London - 1300, 1305, 1306

In the XV century. the permanent residence, the place where the meetings of the Houses of Parliament are held, was the complex of buildings of Westminster Abbey.

The frequency of parliaments also depended on decisions coming from the king. Under Edward I, 21 representative meetings were convened, which were attended by deputies of the "communities"; at the end of this king's reign, parliaments met almost annually. Under Edward III, Parliament convened 70 times. Meetings, excluding travel time, holidays and other breaks, lasted an average of two to five weeks.

At the beginning of the XIV century. it was not uncommon for several parliaments to meet in a year, depending on the political situation. However, in the future, until the end of the XVII century. The periodicity of parliamentary sessions was never fixed in legal norms.

During the XIV-XV centuries, the main features of the organization of the parliament, its procedures and political tradition gradually took shape.

A separate meeting of the chambers predetermined the existence of separate rooms in which meetings of the lords and "communities" were held. The House of Lords met in the White Hall of the Palace of Westminster. The House of Commons worked in the chapter hall of Westminster Abbey. Both chambers united only to participate in the solemn opening ceremony of the parliamentary session, the main act of which was the speech of the king before the assembled parliamentarians; members of the lower house listened to the speech standing behind the barrier.

But despite the separation of the chambers in space, “three estates - the nobility, the clergy and the burghers, turned out to be more united in them than separated from each other, in contrast to how it was in continental countries, which, of course, made it difficult to manipulate them with sides of the king and pushing them together.

The process of constituting the House of Commons as a separate parliamentary structure continued throughout the second half of the 14th and early 15th centuries.

The term "house of commons" comes from the concept of "commons" - communities. In the XIV century. it denoted a special social group, a kind of "middle" class, including chivalry and townspeople. "Communities" began to be called that part of the free population, which had full rights, a certain prosperity and a good name. Representatives of this "middle" class gradually acquired the right to elect and be elected to the lower house of parliament (today we call such rights political). The awareness of its importance, actively formed during the XIV-XV centuries, sometimes determined the position of the chamber in relation to the lords and even to the king.

In the XIV-XV centuries. 37 English counties each delegated two representatives to Parliament. In the XVI century. Monmouth County and the Cheshire Palatinate began to send their deputies to parliament; since 1673 - Durham palatinate. The representation of the counties expanded significantly in the 18th century: 30 deputies joined the House of Commons after the union with Scotland, another 64 deputies were elected in the counties of Ireland.

The number of "parliamentary" cities and "towns" also increased over time; the total number of members of the lower house of parliament grew accordingly. If in the middle of the XIV century. it was about two hundred people, then by the beginning of the XVIII century. there were already more than five hundred of them, precisely due to the increased representation of cities and "towns".

Many members of the lower house have been repeatedly elected to parliament; they were brought together by common interests and similar social status. A significant part of the representatives of the "communities" had a fairly high level of education (including legal education). All this contributed to the gradual transformation of the lower chamber into a capable, in fact, professional organization.

At the end of the 14th century, the position of speaker appeared), who was actually a government official, called to conduct the meetings of the House, to represent the House of Commons in its daily activities, in negotiations with the lords and the king, but not to head this collective assembly. At the opening of a regular session, the speaker was nominated by the Lord Chancellor on behalf of the King. According to tradition, the deputy to whom this high choice fell had to defiantly resign his office, while delivering a pre-prepared speech.

The language of parliamentary documentation, primarily the minutes of the joint sessions of the chambers, was French. Some records, mostly official or related to the affairs of the church, were kept in Latin. In oral parliamentary speech, French was also mainly used, but from 1363 the speeches of deputies were sometimes delivered in English.

One of the important problems in the formation of parliamentary representation was the material support of members of the lower house. Communities and cities, as a rule, provided their deputies with monetary allowance: four shillings for the knights of the counties, two shillings for the townspeople for each day of session. But often the remuneration was “made” only on paper, and parliamentarians had to fight to ensure that these payments became part of the legal tradition.

At the same time, there were regulations (1382 and 1515), according to which a deputy who did not appear at the session without good reason was subject to a fine185.

The most important of these was participation in decision-making on taxation matters. The fiscal system of the state was still being formed, and most of the taxes, primarily direct taxes, were extraordinary. Note that in England taxes were paid by all subjects, and not only by the "third estate", as was the case, for example, in France. This circumstance eliminated one of the possible causes of confrontation between the estates. In 1297, Parliament acquired the right to allow the king to collect direct taxes on movable property. From the 20s. 14th century he agrees to the collection of extraordinary, and by the end of the XIV century - and indirect taxes. Soon the House of Commons achieved the same right in respect of customs duties.

Thus, the king received the main part of the financial income with the consent of the lower house (officially - in the form of its “gift”), which acted here on behalf of those who were to pay these taxes. The strong position of the House of Commons in such an important issue for the kingdom as finances allowed it to expand its participation in other areas of parliamentary activity. According to the figurative expression of the English historian E. Freeman, the lower chamber in name gradually became the upper one in reality186.

Parliament has achieved significant success in the field of legislation. Long before its emergence in England, there was a practice of filing private petitions with the king and his council - individual or collective petitions. With the advent of Parliament, petitions began to be addressed to this representative assembly. The parliament received numerous letters reflecting the most diverse needs of both individuals and cities, counties, trade and craft corporations, etc. Based on these requests, the parliament as a whole or individual groups of its members developed their own appeals to the king - “ parliamentary petitions. These appeals usually concerned important issues of general state policy, and some kind of nationwide measures were supposed to be the answer to them187.

Already in the XIV century. Parliament had the opportunity to influence the king in order to adopt laws that reflected the interests of large and medium landowners, the merchant elite. In 1322, a law was passed stating that all matters "concerning the position of the lord of our king ... and ... the position of the state and the people, must be discussed, agreed and accepted in the parliament of our lord the king and with the consent of the prelates, counts, barons and communities of the kingdom"188. In 1348, Parliament demanded from the king that his requests be carried out even before taxes were approved.

In the future, the development of the institution of "parliamentary petitions" led to the emergence of a new procedure for adopting legislation. Initially, Parliament designated a problem requiring the issuance of a royal law - an ordinance or statute. In many cases, statutes and ordinances did not adequately reflect the wishes of Parliament (especially the House of Commons). The consequence of this was the desire of the parliament to fix in its resolutions those legal norms, the adoption of which they sought. Under Henry VI, there was a practice of considering a bill in parliament - a bill. After three readings and editing in each house, the bill, approved by both houses, was sent to the king for approval; after his signature, it became a statute.

Over time, the wording of the acceptance or rejection of the bill acquired a strictly defined form. A positive resolution read: “The King likes it”, a negative one: “The King will think about it”1.

The development of parliamentary rights in the field of legislation was also reflected in legal terminology. In the statutes of the XIV century. it was said that they were issued by the king "by the advice and consent (par conseil et par assentement) of the lords and commons." In 1433 it was first said that the law was issued "by the authority" (by the authority) of the lords and commons, and from 1485 a similar formula became permanent.

Parliament's participation in the political process was not limited to its legislative activities. For example, parliament was actively used by the king or opposing groups of nobles to eliminate high officials. In this case, parliamentarians spoke out with denunciations of persons suspected of violations of the law, abuses, unseemly acts. Parliament did not have the right to remove dignitaries from power, but had the ability to accuse individuals of wrongdoing. Against the backdrop of "public criticism", the struggle for power acquired a more justified character. On a number of occasions, speeches were made within the walls of the House of Commons in which the actions of kings were accused. In 1376, Peter de la Mar, Speaker of the House, made a statement sharply criticizing the activities of King Edward III.

During the period of the struggle for the royal throne and feudal civil strife, Parliament acted as the body that legitimized the change of kings on the English throne. Thus, the deposition of Edward II (1327), Richard II (1399) and the subsequent coronation of Henry IV Lancaster were sanctioned

The judicial functions of Parliament were very significant. They were within the competence of its upper chamber. By the end of the XIV century. she acquired the powers of the court of peers and the supreme court of the kingdom, which considered the most serious political and criminal offenses, as well as appeals. The House of Commons could act as intercessor of the parties and present to the Lords and the King its legislative proposals for

The importance and role of the parliament was not the same at different stages

From the second half of the XV century. hard times began for him. During the years of feudal civil strife - the War of the Scarlet and White Roses (1455-1485), parliamentary methods of solving state issues were replaced by forceful ones. At the end of the XV century. political life in the kingdom stabilized. In 1485, a new dynasty came to power - the Tudor dynasty, whose representatives ruled England until 1603. The Tudor years were marked by a significant increase in royal power. Under Henry VIII, in 1534, the English monarch was proclaimed head of the national church.

The following principles were established in relations between the royal court and parliament. Monarchs sought to use the authority of the assembly to their advantage. They issued flattering declarations, emphasizing their respect for the institution of parliament. At the same time, the influence of the latter on the supreme power and the possibility of implementing independent political initiatives were reduced to a minimum.

The composition of the House of Commons was formed with the active, interested participation of the royal administration. The nature of parliamentary elections in medieval England differed significantly from what is observed in modern times. A modern author believes: “To say that election manipulation was born simultaneously with the elections themselves is not enough. It is better to say that the elections were born only because they can be manipulated”1. The electoral process was almost always influenced by powerful people; the candidacy of the future chosen one was most often determined not so much by the sheriffs or the city elite, but by influential magnates or directly by the king.

Structures subordinate to the king (for example, the Privy Council) exercised control over the activities of parliamentarians, the course of debates, and the process of considering bills. It should be noted that, under the Tudors, parliaments were convened rarely and irregularly.

Queen Elizabeth I in Parliament

Nevertheless, Parliament occupied a fairly important place in the system of English statehood in the era of absolutism. He not only approved the orders of the crown, but also actively participated in the legislative activities of the state192. The Chambers worked hard and fruitfully on bills regulating various spheres of the socio-economic life of England (foreign trade, customs rules and duties, unification of weights and measures, navigation issues, regulation of prices for goods produced in the country). For example, in 1597, Elizabeth I approved 43 bills passed by Parliament; in addition, 48 more bills were passed on her initiative.

Under Henry VIII and his successors, Parliament's involvement was prominent in religious reform and in matters of succession.

Even in the new historical conditions, the parliament not only continued to function, but also retained a fairly high authority, in contrast to the estate-representative institutions of many European countries, which, as a rule, ceased to meet during the period of the establishment of absolutism.

Parliament was viable primarily because the representatives of different social groups who sat in it could work together. Despite the complexity of relations and the difference of interests, they were able to cooperate. Being at the same time the head of state and parliament, being the initiator of the convening of sessions and the final authority of all parliamentary powers and decisions, the king associated himself with this organization in the closest way. Parliament did not exist without the king, but the monarch was limited in his actions without the support of parliament. A reflection of this feature of the English political system was the formula "king in parliament", symbolizing state power in its entirety.

It should be noted that it was in the Tudor era that the trend of acquiring special “political” rights and freedoms by members of parliament, originating at the turn of the 14th-15th centuries, developed. In the XVI century. members of both houses acquired a number of significant legal privileges, the so-called "parliamentary freedoms" - the prototypes of future democratic rights of the individual. Since the parliament was the highest political assembly of the kingdom, the speeches delivered during the meetings of its chambers were bound to acquire a certain legal "immunity", since many deputies understood their mission as the most accurate statement of the opinions that they came to defend. The earliest recorded case of claims by the House of Commons for certain privileges occurred in 1397, when, at the initiative of the Deputy Hexi (Naheu), it was decided to reduce the cost of maintaining the royal court. The Lords accused the deputy of treason, and he was sentenced to death, but then pardoned. In connection with this incident, the lower house passed a resolution stating that the deputy was subjected to persecution "against the law and order that was customary in Parliament, contrary to the customs of the House of Commons"193.

In 1523 Thomas More194, Speaker of the House of Commons,194 set a precedent by asking King Henry VIII for the right to speak in Parliament without fear of prosecution for his words,195 and under Elizabeth I this privilege was legalized (although often violated in practice).

The broader concept of parliamentary immunity is partly connected with the problem of “freedom of speech”. Even in ancient times, in England there was a custom of the so-called “King's peace”: every person heading to or returning from gemot was on the road under royal protection. But this protection did not work in the event that if the subject himself committed a crime, violated the “peace”.

The incident of 1397 mentioned above showed the importance of the issue of the legal immunity of an elected deputy"1 during his time as a parliamentarian. Hexie was accused of treason - one of the most serious crimes, but the House of Commons considered that this was contrary to her rights and customs. Consequently, already at the end of the fourteenth century Parliament, as a corporation, was aware of the need to protect the freedom of its members from political and other persecution.In the sixteenth century there was an incident that showed that the House of Commons considered the arrest of a parliamentarian unacceptable.In 1543, Deputy J. Ferrers (Georg Ferrers) was arrested for debts while on his way to the session. The House asked the sheriffs of London to release Ferrers, but received a rude refusal. Then, according to the verdict of the House of Commons, the officials who imprisoned the deputy were arrested. In the current legal conflict, King Henry VIII issued an order for privileges of members of the House of Commons: their person and property were recognized free from arrest during parliament session.

Members of the House could lose immunity and be excluded from its composition for illegal actions directed against Parliament or for other serious offenses (treason, criminal offense)196.

The British Parliament is the oldest in the world. It originatedin the 12th century as Witenagemot, the body of wise councillorsto consult the King in his policy. The British Parliament consists of the House of Lords and the House of Commons and the Queen as its head. The House of Commons plays the major role in law-making. It consists of Members of Parliament(called MPs for short). Each of them represents an area in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland. MPs are elected either at agegeneral election or at a by-election following the death orretirement. Parliamentary elections are held every 5 years and itis the Prime Minister who decides on the exact day of theelection. The minimum voting age is 18. And the voting is takenby secret ballot. The election campaign lasts about 3 weeks, TheBritish parliamentary system depends on politicals parties. Theparty which wins the majority of seats forms the goverment andits leader usually becomes Prime Minister. The Prime Ministerchooses about 20 MPs from his party to become the cabinet ofministers. Each minister is responsible for a particular area in the government. The second largest party becomes the officialopposition with its own leader and "shadow cabinet". The leaderof the opposition is a recognized post in the House of Commons.The parliament and the monarch have different roles in thegovernment and they only meet together on symbolic occasions, suchas coronation of a new monarch or the opening of the parliament.In reality, the House of Commons is the one of three which hastrue power. The House of Commons is made up of six hundred and fifty elected members, it is presided over by the speaker, a member acceptable to the whole house. MPs sit on two sides of the hall, one side for the governing party and the other for theopposition. The first 2 rows of seats are occupied by the leadingmembers of both parties (called "front benches") The back benchesbelong to the rank-and-life MPs. Each session of the House of Commons lasts for 160-175 days. Parliament has intervals duringhis work. MPs are paid for their parliamentary work and have toattend the sittings. As mention above, the House of Commons plays the major role in law making. The procedure is the following: aproposed law ("a bill") has to go through three stages in orderto become an act of parliament, these are called "readings". Thefirst reading is a formality and is simply the publication of theproposal. The second reading involves a debate on the principles of the bill, it is an examination by parliamentary committy. And the third reading is a report stage, when the work of the committy isreported on to the house. This is usually the most important stage in the process. When the bill passes through the House of Commons, it is sent to the House of Lords for discussion, when the Lords agree it, the bill is taken to the Queen for royalassent, when the Queen sings the bill, it becomes act of the Parliament and the Law of the Land. The House of Lords has morethan 1000 members, although only about 250 take an active part inthe work in the house. Members of this Upper House are notelected, they sit there because of their rank, the chairman ofthe House of Lords is the Lord Chancellor. And he sits on a special seat, called "Wool Sack." The members of the House of Lordsdebate the bill after it has been passed by the House of Commons.Some changes may be recommended and the agreement between the twohouses is reached by negotiations.

The English Parliament is the symbol of Great Britain.

The emergence of Parliament in England falls on the reign of Henry III. It was his mistakes in domestic politics that led to the usurpation of power by the English barons. The power of Henry III was limited to the baronial council (15 people). Sometimes also convened council of the nobility, which elected a special reform committee, consisting of 24 people. The reforms carried out by the barons significantly curtailed the rights and privileges of knights and townspeople.

The indignant people in 1259 opposed the policy and put forward their demands, the main of which was the protection of the interests of free citizens of England and the equality of all before the law. As a result, the so-called. "Westminster Provisions". But the barons refused to comply with them, and the king did not want to intervene in the conflict situation.

Furthermore, Henry III decided to use it to strengthen his own power. Being God's anointed on the throne, Henry III received from the Pope a release from all obligations to the discontented part of his people. It was a kind of immunity from the need to resolve a conflict situation.

As a result, a real civil war broke out in the country in 1263. Knights, townspeople (merchants and artisans) opposed the power of the barons and the king, Oxford students, peasants and even a few barons. So Baron Simon de Montfort was at the head of the rebels.

The king took refuge in Westminster Abbey, and his army was led by Crown Prince Edward.

The active support of the townspeople allowed the rebels to win. So, the London townspeople sent 15 thousand people to Montfort. The rebel army took the cities of Gloucester, Bristol, Dover, Sandwich and others, and went to London.

In May 1264, at the battle of Lewes, Montfort's army utterly defeated the royal army. The king and prince Edward were captured and forced to sign an agreement with the rebels, according to which it became necessary to involve representatives of various classes in order to rule the country.

As a result, on January 20, 1265, a meeting of the assembly of barons, supporters of de Montfort, the higher clergy, as well as 2 knights elected from each county and 2 citizens from each large city of England was opened in Westminster Abbey. This was the first English Parliament. From now on, representatives of various classes began to control power in the country.

However, the war continued on August 4, 1265. The royal army defeated the army of Simon de Montfort (Battle of Ivzeme). Montfort himself was killed. The struggle of disparate rebel groups continued until the autumn of 1267.

But even having restored their power over England, Henry III, and later his son and heir to the throne, Edward I, did not abandon parliament, although they tried to use it mainly to introduce new taxes.