in Russia until the end of the 17th century. there were almost no standing troops; the prince's squad had the same clothes that civilians wore, only with the addition of armor; only occasionally did a prince dress his squad uniformly and sometimes not in Russian: for example, Daniil of Galicia, helping the Hungarian king, had his regiments dressed in Tatar. In the XVI century. archers appear, who, already constituting something like a permanent army, also have monotonous clothes, first red with white berets (slings), and then, under Mikhail Feodorovich, multi-colored; Streltsy regiments had a full dress uniform, consisting of an upper caftan, a zipun, a cap with a band, trousers and boots, the color of which (except for trousers) was regulated according to belonging to a particular regiment. To perform daily duties, a field uniform was used - a “wearable dress”, which has the same cut as the front dress, but from cheaper gray, black, or brown cloth.

The tenants had expensive terliks and brocade hats; later there are also horse-drawn tenants who had wings behind their shoulders. Ryndy, who made up the honorary guard of the kings, dressed in caftans and feryazis made of silk or velvet, trimmed with furs, and wore high hats made of lynx fur. Under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, archers dress in long coats made of cloth with large turn-down collars and fasteners in the form of cords; on his feet are high boots, on his head a cap in peacetime is soft, high, trimmed with fur, in wartime - a round iron one. The regiments differed among themselves in the color of collars, hats and sometimes boots. Commanding persons had leather mittens and staves, which at that time generally served as a sign of power. Soldiers and foreign regiments also dressed like archers.

In the work of the Italian F. Tiepolo, compiled according to eyewitness accounts, the Russian infantry of the middle of the 16th century. is described as follows:

"The infantry wears the same coats as the cavalry, and few have armour."

Peter I and the era of palace coups.

The army, newly formed by Peter I, was also given a new form of uniform, modeled on the Swedish one. This form was quite simple and the same for the infantry and for the cavalry: a knee-length caftan, green in the infantry, blue in the cavalry; the camisole is somewhat shorter than the caftan, trousers are narrow to the knees, boots with bells in marching uniform, usually shoes with a copper buckle, stockings in the guards are red, in the army green, in the infantry and dragoon regiments triangular hats, the grenadiers have round leather hats with an ostrich plume, in bombardment companies, a headdress like a grenadier, but with a bear's edge. The epancha served as outerwear, in all types of weapons the same red color, very narrow and short, reaching only to the knees. The distinction of non-commissioned officers was the gold galloon on caftan cuffs and hat brim. The sides and pockets of officers' caftans and camisoles were sheathed with the same lace, the distinction of which was still served by gilded buttons, a white tie and, at the front dress, a white plume with a red plume on the hat. In the ranks, officers also wore a special metal badge that was worn around the neck. Scarves worn over the shoulder served to distinguish headquarters from chief officers: the former had gold tassels, the latter had silver ones. Powdered wigs were worn only by officers, and then only in dress uniform. Each soldier had a sword and a gun, and the dragoons on horseback had a pistol and a broadsword; officers, in addition to the grenadiers, who had guns with a gold shoulder strap (belt, sling), also had swords and pierced ones (something like a spear on a long shaft). Beards were shaved, but mustaches were allowed.

In subsequent reigns, the uniform changed, but in general the samples of Peter the Great were preserved, only they became more and more complicated, especially after the Seven Years' War, which entailed the cult of Frederick the Great. The desire for convenience in uniform was completely forgotten; it was replaced by the desire to make a soldier look good and give him such a uniform, the maintenance of which in order would take all his free time from service. Especially a lot of time the soldier used to keep his hair in order; hair was combed into two curls and a braid and powdered on foot; in horse riding, it was allowed not to powder the hair and not to curl it into curls, taking it into one dense braid, but on the other hand it was required to grow and comb the mustache high or, who did not have them, to have false ones. The soldier's clothing was extremely narrow, which was caused by the requirement of the then standing and especially marching without bending the knees. Many parts of the troops had elk trousers, which, before putting on, were wetted and dried already in public. The outfit was so uncomfortable that in the manual for training, the recruit was ordered to put it on no earlier than after three months, having previously taught the soldier to stand upright and walk, and even on this condition, “dress little by little, from week to week, so as not to suddenly tie him up and disturb him."

The reign of Catherine II.

The form of uniforms in the reign of Catherine II was observed, especially in the guards, very inaccurately, and even in the army, unit commanders allowed themselves to change without permission. Guards officers were weary of it and out of order did not wear it at all. All this evoked ideas about changing the uniform of the troops, which was changed at the end of Catherine's reign at the insistence of Prince Potemkin, who said that “curling, powdering, weaving braids - is this a soldier's business? Everyone must agree that it is more useful to wash and scratch your head than to weigh it down with powder, lard, flour, hairpins, braids. The soldier's toilet should be such that he got up, then he's ready. Army uniforms have been greatly simplified and made much more comfortable; it consisted of a wide uniform and trousers tucked into high boots; but in the cavalry, and especially in the guards, the uniform remained shiny and uncomfortable, although complex hairstyles and leggings disappeared from the ordinary uniform of the troops. In Russia, epaulets appeared on military clothing under Peter I. The use of epaulettes as a means of distinguishing the military personnel of one regiment from the military personnel of another regiment began in 1762, when each regiment was equipped with shoulder straps of various weaving from a garus cord. At the same time, an attempt was made to make the shoulder strap a means of distinguishing between soldiers and officers, for which in the same regiment officers and soldiers had different weaving of shoulder straps.

Paul I started the military, as well as other reforms, not only out of his own whim. The Russian army was not at the peak of its form, discipline in the regiments suffered, titles were not deservedly given out - for example, noble children were assigned to some rank from birth, to one regiment or another. Many, having a rank and receiving a salary, did not serve at all (apparently, it was mostly these officers who were fired from the state). As a reformer, Paul I decided to follow his favorite example - Peter the Great - like the famous ancestor, he decided to take as a basis the model of the modern European army, in particular the Prussian one, and what, if not German, can serve as an example of pedantry, discipline and perfection. In general, military reform was not stopped even after the death of Paul.

Paul I transplanted the entire Prussian uniform of the troops to Russia. The uniform consisted of a wide and long uniform with coattails and a turn-down collar, tight and short trousers, varnished shoes, stockings with garters and boot-like boots, and a small triangular hat. The regiment differed from the regiment in the color of collars and cuffs, but these colors were without any system and extremely variegated, difficult to remember and poorly distinguished, since the colors included such as apricot, isabella, celadon, sand, etc. Hairstyles again gain importance; soldiers powder their hair and braid it into regular length braids with a bow at the end; the hairstyle was so complicated that the troops had special hairdressers.

Alexander I.

Upon the accession to the throne of Emperor Alexander I, a supporter of magnificent military uniforms, the uniform became even more uncomfortable. Pavlovskaya form in 1802 was replaced by a new one. Wigs were destroyed forever, boots-like boots and shoes were replaced with boots on trouser fasteners; the uniforms were significantly shortened, narrowed and looked like tailcoats (the tails on the uniforms were left, but the soldiers had short ones); standing solid collars and shoulder epaulettes and epaulettes were introduced; officers' collars were decorated with embroidery or buttonholes and were generally colored; shelves were distinguished by their colors. The light and comfortable cocked hats were replaced by new hats, high, heavy and very uncomfortable; they bore the common name of shakos, while the straps on the shakos and the collar rubbed the neck. The highest commanding officers were assigned to wear the then huge double-cornered hats with feathers and edging. It was warm in the bicorne in winter, but very hot in summer, so the peakless cap also became popular in the warm season. Shoulder straps were first introduced only in the infantry and all red, then the number of colors was increased to five (red, blue, white, dark green and yellow, in order of the regiments of the division); officer epaulettes were sheathed with galloon, and in 1807 they were replaced by epaulettes. Subsequently, epaulettes were also given to the lower ranks of some cavalry units. Pavlovsky cloaks were replaced by narrow overcoats with standing collars that did not cover the ears. In general, despite the significant simplification of the form of uniforms, it was still far from convenient and not practical.

It was difficult for the soldier to keep in good order the mass of belts and accessories that were part of the equipment; in addition, the uniform was still very complicated and hard to wear. The militia under Alexander I first dressed in whatever dress they wanted; later they were given a form consisting of a gray caftan, trousers tucked into high boots, and a cap (cap) with a copper cross on the crown. From the day of the accession to the throne of Alexander I and until 1815, officers were allowed to wear particular dress outside of service; but at the end of the foreign campaign, as a result of fermentation in the army, this right was abolished.

Nicholas I.

Under Nicholas I, uniforms and overcoats were at first still very narrow, especially in the cavalry, where officers even had to wear corsets; under the overcoat it was impossible to pry anything; the collars of the uniform, remaining as high as ever, were fastened tightly and strongly propped up the head; the shakos reached 5.5 inches in height and looked like buckets turned upside down; during parades, they were decorated with sultans 11 inches long, so that the entire headdress was 16.5 inches high (about 73.3 cm). Bloomers, cloth in winter and linen in summer, were worn over boots; under them, boots with five or six buttons were worn, since the boots were very short. Especially a lot of trouble for the soldier continued to cause ammunition from white and black lacquered belts, which required constant cleaning. A huge relief was the permission to wear, first out of order, and then on the campaign, caps similar to the current ones. The variety of forms was very great; even the infantry had uneven uniforms; some of its parts wore double-breasted uniforms, others single-breasted. The cavalry was dressed very colorfully; its shape had a lot of little things, the fitting of which required both time and skill. Since 1832, simplifications began in the form of uniforms, expressed primarily in the simplification of ammunition; in 1844, heavy and uncomfortable shakos were replaced by high helmets with a sharp pommel (however, shakos were retained in the equestrian grenadier and hussar regiments), officers and generals began to wear caps with visors instead of obsolete two-corners; The troops were provided with mittens and earmuffs. Since 1832, officers of all branches of arms have been allowed to wear mustaches, and officers' horses are not allowed to trim their tails or cut their heads. In general, in the last years of the reign of Nicholas, the uniform acquired instead of the French Prussian cut: dress helmets with ponytails were introduced for officers and generals, uniforms for the guards were sewn from dark green, almost black cloth, tails on army uniforms began to be made extremely short, and on white trousers at ceremonial and solemn occasions began to sew on red stripes, as in the Prussian army. In 1843, transverse stripes were introduced on soldier's shoulder straps - stripes, according to which ranks were distinguished. In 1854, epaulettes were also introduced for officers: at first, only for wearing on overcoats, and from 1855, on everyday uniforms. Since that time, the gradual replacement of epaulettes by shoulder straps began.

Alexander II.

The troops received a completely convenient form of uniform only in the reign of Emperor Alexander II; gradually changing the shape of the uniforms of the troops, they finally brought it to such a cut when, having a beautiful and spectacular appearance in brilliant arms, it was at the same time spacious and allowed for warmer cars to be pulled up in cold weather. In February 1856, tailcoat-like uniforms were replaced by full-skirted uniforms. The uniform of the guard troops was distinguished by its special brilliance, which in ceremonial cases since the time of Alexander I wore special colored cloth or velvet (black) lapels (bibs); the cavalry retained their shiny uniforms and their colors, but the cut was made more comfortable; all were given spacious overcoats with a turn-down collar covering the ears with cloth buttonholes; uniform collars were significantly lowered and broadened, although they are still hard and of little practical use. The army uniform was first double-breasted, then single-breasted; harem pants at first were worn in boots only on a campaign, then always at the lower ranks; in summer the trousers were linen. Beautiful, but uncomfortable helmets remained only with the cuirassiers and in the guard, who, in addition, had caps without visors, which were canceled in 1863 and left exclusively for the fleet; in the army, the ceremonial and ordinary dress was a kepi (in 1853-1860, a ceremonial shako), in the first case with a sultan and a coat of arms. The officers also had caps. Lancers continued to wear diamond-topped shakos. At the same time, a very convenient and practical hood was given, which served the soldier a lot in the harsh winter. Backpacks and bags were lightened, the number and width of straps for wearing them were reduced, and in general the soldier's burden was lightened.

Alexander III.

By the beginning of the 70s of the XIX century. there were no longer any embarrassments about wearing mustaches, beards, etc., but short hair was required. The form of uniform of this era, being quite comfortable, was expensive; moreover, it was difficult to fit uniforms with buttons and a waist. These considerations, and most importantly, the desire for nationalization, prompted Emperor Alexander III to radically change the uniforms of the troops; only the guards cavalry retained, in general terms, their former rich clothes. Uniformity, cheapness and ease of wearing and fitting were put at the basis of the new uniform. All this was achieved, however, at the expense of beauty. The headgear, both in the guards and in the army, consisted of a low, round lamb hat with a cloth bottom; the hat is decorated in the guards with the St. Andrew's star, in the army - with the coat of arms. A uniform with a standing collar in the army with a straight back and side without any piping is fastened with hooks that can be freely altered, broadening or narrowing the uniform; the guards uniform had an oblique border with a piping, a colored high collar and the same cuffs; the uniform of the cavalry, with its transformation exclusively into dragoon regiments (except for the guards), completely became similar to the uniform of the infantry, only somewhat shorter; the lambskin front hat was reminiscent of an ancient boyarka; wide trousers tucked into high boots, in infantry of the same color as the uniform, in gray-blue cavalry, and gray overcoats, fastened in the army with hooks, and in the guard with buttons, complete the simple uniform of a soldier of the 70-80s of the XIX century . The absence of buttons also had the advantage that an extra shiny object was eliminated, which in sunny weather could draw the attention of the enemy and cause his fire; the abolition of sultans, helmets with brilliant coats of arms and lapels had the same significance. The cavalry, when changing uniforms, retained their former colors on their hats, collars and in the form of piping. In the infantry and other types of weapons, starting with the introduction of a kepi with bands, the difference between one regiment and another is based on a combination of colors of shoulder straps and bands. The division differed from the division by the numbers on the shoulder straps; in each infantry division, the first regiment had red, the second - blue, the third - white, the fourth - black (dark green) bands, the first two regiments (first brigade) - red, and the second two regiments (second brigade) - blue shoulder straps. All guards, artillery and sapper troops had red, and arrows - crimson shoulder straps. The difference between one guards regiment from another, except for bands, concluded. even in the color of the edging and the device. The Form described was in many respects close to the requirements for the uniform of the troops, but caps and caps without a visor did not protect the eyes from the sun's rays. Significant relief for the troops was allowed by Alexander II by the introduction of tunics and linen shirts for wearing in hot weather; this was complemented by white covers for caps throughout the summer period, as well as the ensuing permission to replace uniforms with tunics in summer, with orders and ribbons on them, even on solemn occasions.

Also during the reign of Alexander III, who, as you know, stood on conservative positions, he made sure that the uniform of a soldier resembled peasant clothes. In 1879, a tunic with a standing collar was introduced for soldiers, like a shirt-shirt.

Nicholas II.

Emperor Nicholas II almost did not change the form of uniforms established in the last reign; the form of the guards cavalry regiments of the era of Alexander II was only gradually restored; the officers of the entire army were given galloon (instead of the simple leather introduced by Alexander III) shoulder harness; for the troops of the southern districts, the ceremonial headdress was considered too heavy and was replaced by an ordinary cap, to which a small metal coat of arms is attached. The most significant changes followed only in the army cavalry. A modest uniform without buttons at the beginning of the reign of Nicholas II was replaced by a more beautiful double-breasted, sewn at the waist and with a colored edging along the side of the uniform. A shako was introduced for the Guards regiments.

In each cavalry division, the regiments are given the same colors: the first is red, the second is blue, the third is white. The former colors remained only in those regiments for which some historical memory was associated with their color. Simultaneously with the change in the colors of the regiments, their caps were changed: they began to make not the bands, but the crowns, so that the color of the regiment could be seen at a great distance, and all the lower ranks were given visors. Auxiliary troops and various special corps have the form of an infantry model.

In 1907, following the results of the Russo-Japanese War, the Russian army introduced as a summer uniform a single-breasted khaki tunic with a stand-up collar on hooks, with a five-button fastener, with pockets on the chest and on the sides (the so-called "American" cut) . The white tunic of the former sample has fallen into disuse.

In aviation, on the eve of the war, a blue tunic was adopted as working clothes.

period of the First World War.

During the First World War of 1914-1918, tunics of arbitrary samples were widely used in the army - imitations of English and French models, which received the general name "French" - after the name of the English General John French. The features of their design mainly consisted in the design of the collar - a soft turn-down, or soft standing collar with a button closure, like the collar of a Russian tunic; adjustable cuff width (using straps or a split cuff), large patch pockets on the chest and floors with button closures. Among aviators, French officer-type jackets were of limited distribution - with an open collar to be worn with a shirt and tie.

By the revolution of 1917, the Russian army approached in tunics of the most diverse cut. Compliance with the charter was observed only in the headquarters, logistics organizations, as well as in the fleet. However, even this relative order was destroyed by the efforts of the new military and naval minister A.F. Kerensky. He himself wore a jacket-jacket of an arbitrary pattern, after him many leaders of the army put it on. The fleet was ordered to change into a tunic with hook fasteners trimmed with black braid along the side, with pockets devoid of valves. Prior to the manufacture of new samples of the form, it was necessary to alter the existing one. The officers executed this order arbitrarily, as a result, the fleet also lost a single sample of the tunic.

period of the Civil War.

The prototype of the Workers 'and Peasants' Red Army was the Red Guard detachments, which began to form after the February coup of 1917, and the revolutionaryized units of the Russian Imperial Army. The Red Guards did not have any established uniform, they were distinguished only by a red armband with the inscription "Red Guard" and sometimes a red ribbon on their headdress. The soldiers wore the uniform of the old army, at first even with cockades and shoulder straps, but with red bows under them and on the chest. However, already in 1918, the military-political leadership of the RSFSR became clear about the need to introduce a regulated uniform for the Red Army. Its first element was a protective-colored cloth helmet with a star, approved by order of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic of January 16, 1919 and given the unofficial name "bogatyr". The Red Army soldiers of Ivanovo-Voznesensk began to wear it, where at the end of 1918 a detachment of M.V. Frunze was formed. Later, she received the name "Frunzevka", and then - "Budyonovka".

The early Red Army rejected officership as a phenomenon, declaring it a "remnant of tsarism." The very word "officer" was replaced by the word "commander". Shoulder straps were abolished, military ranks were abolished, instead of which the titles of positions were used, for example, “komdiv” (division commander), or “comcor” (corps commander). As insignia, triangles sewn onto the collar of uniforms were used (for junior command staff K 1 and 2), squares (for middle command staff K 3-6), rectangles (for senior command staff K 7-9) and rhombuses (for generals K-10 and higher). The types of troops differed in the color of their buttonholes.

1940s-1960s

On May 7, 1940, the personal ranks "general", "admiral" were introduced, replacing the former "commander", "commander" and so on. At the beginning of 1943, the unification of the surviving official ranks took place. The word "officer" returned to the official lexicon again, along with shoulder straps, and the old insignia. The system of military ranks and insignia practically did not change until the collapse of the USSR; It should also be noted that the insignia of the Red Army of the 1943 model were also not an exact copy of the royal ones, although they were created on their basis. So, the rank of colonel in the tsarist army was designated by shoulder straps with two longitudinal gaps, and without asterisks; in the Red Army - two longitudinal gaps, and three medium-sized stars arranged in a triangle. after 1943, the Marshals of the Soviet Union had a special uniform, different from the general general's; its most conspicuous and enduring feature was the pattern of oak leaves (rather than laurel branches) on the front of the collar; the same pattern was on the cuffs of the sleeves. This detail was kept on the uniforms of 1943, 1945 and 1955. Also, the visors of the marshal's caps were colored, and not black or cloth, like the generals.

1970-1980s.

In accordance with the rules for wearing military uniforms - Military uniforms were established:

a) for marshals, generals, admirals and officers:

front door for building;

front door;

casual;

field (in the Navy - everyday for the system);

b) for soldiers, sailors, sergeants, foremen, cadets and pupils of military schools:

front door;

everyday-field (in the Navy-everyday);

working (for conscripts).

Each of these forms was divided into summer and winter, and in the Navy, in addition, they had numbering.

Armed forces of the Russian Federation.

In the armed forces of Russia, there are a number of accessories that were in the military uniform of the times of the Russian Empire, such as shoulder straps, boots and long overcoats with buttonholes - signs of belonging to a particular type of troops on the collars for all ranks. The color of the uniform is the same blue/green as the uniform worn prior to 1914. In October 1992, a new uniform was approved. According to the nomenclature, it contained 1.5 - 2 times fewer items than in the uniform of the USSR Armed Forces. The adopted form differed significantly from the Soviet one in favor of simplification. First of all, in the Russian Ground Forces, the officer dress uniform of the color of the sea wave and the general's gray-steel color were canceled. Colored shoulder straps, colored caps and buttonholes were forever destroyed as "remnants" of the Soviet era. Depending on the specific item of clothing, the emblems of the military branches were placed in the corners of the collar or on shoulder straps. For everyday and dress uniforms, a single color - olive - was established. The sailors retained the color that has always been traditional for the Navy - black. Shoulder straps on all types of military clothing have become reduced in size. Other changes were introduced as well.

On May 23, 1994, the President of the Russian Federation approved the uniform of Russian servicemen. The military uniform is divided into full dress, everyday and field, and each of them, in addition, into summer and winter.

Military uniforms are worn strictly in accordance with the Rules for wearing military uniforms by military personnel of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, which are approved by order of the Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation. These Rules apply to military personnel serving in the Russian Armed Forces, students of the Suvorov military, Nakhimov naval and military music schools, cadet and cadet naval corps, as well as citizens dismissed from military service with enrollment in the reserve or retired with the right wearing military uniforms.

After the collapse of the USSR, the Russian Armed Forces continued to wear the military uniform of the Soviet Army and replaced it as it wore out.

The military personnel of the Presidential Regiment in recent years have been dressed in a special ceremonial uniform, reminiscent of the uniform of the imperial guard regiments before the First World War.

In 2010, there was another change in the military uniform.

2nd study question: "The history of the emergence and development of the award system in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation."

The custom of awarding special insignia for military and other services to the state has long been established. Even in ancient Greece and ancient Rome, phalers were used for this - gold or silver mugs with images of gods or generals. (Phaleristics takes its name from them - collecting and studying orders and medals, various insignia and tokens, award documents.) Wreaths (crowns) served as a higher degree of distinction among the Romans. For example, an oak wreath was awarded to a soldier for saving a comrade in battle. The crown with the image of a battlement wall was given to the one who was the first to climb the enemy walls during the assault. The wreath, decorated with a golden image of the ship, was received by the sailor who was the first to board the enemy ship during boarding. On the victorious commander, by decision of the Senate, they laid the laurel wreath of the victor. An echo of these customs is the use of oak or laurel leaves (branches) as a traditional element of decoration for orders and medals.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD, its award system also ceased to exist. Only a millennium later, in the XIV century, in one of the medieval Italian chronicles, the fact of awarding a medal was noted (by the way, the very name "medal" goes back to the Latin word "metallum" - metal).

In ancient Russia, the official insignia - a kind of predecessor of our modern orders and medals - was the hryvnia. It was a golden neckband or chain with a precious metal ingot suspended from it. For the first time such an award is mentioned by an ancient Russian chronicler: “In the summer of 6576, Volodar came from the Polovtsy to Kiev, and Alexander Popovich went out at night to meet them, and killed Volodar and his brother and beat many Polovtsy others, and others in the field rejoiced zealously, and lay the nan hryvnia to gold. This was not only the most honorable, but also, in the literal sense, an expensive award: at that time, Russia did not mine its own silver and gold (and silver Arab dirhams then made up the basis of its monetary circulation).

However, Alyosha (Alexander) Popovich, the leader of the vigilantes from Rostov the Great, deserved it in full. For at that time there was nothing more dangerous and ruinous for Southern Russia than the endless Polovtsian raids.

In the centuries-old struggle for their existence, freedom and independence of the peoples inhabiting our land, the Russian award system arose and developed.

Since the 15th century, gold, gilded and silver coins of domestic and foreign minting began to be distributed for distinction in military service, which, however, were not included in monetary circulation. And although these signs ("Moskovki", "Novgorodka", English "shipmen", almost forty gram "Portuguese") outwardly did not differ from ordinary coins, they were awarded not as a cash gift, but as a military honor, and their size and weight depended from the nobility and rank of the recipient. So, only a prince could get a “Portuguese” with a chain, an ordinary “golden one” with a chain - a governor, a golden “Novgorodka” or “Moskovka” - a hundred head, and gilded or silver kopecks were intended for ordinary soldiers - archers, gunners, security guards, boyar and eager people, etc.

For example, in the "Discharge Book" of the times of Ivan the Terrible, there is such an entry about honoring the victorious participants in the second Livonian campaign in 1577: "The sovereign for that service of Bogdan (Velsky) granted the golden Portuguese and the chain to gold, and Demsnshi Cheremisov the golden Ugrian, and the nobles of the sovereign according to a gold naugorodka, and others in a golden moskovka, and others in a gilded one ... "Depending on the degree of the award," gold "was either sewn onto clothes or worn on chains.

At the same time, certain rules for awarding "gold" are formed. The beginning of such an act was the receipt of the governor's report with a messenger, which was a kind of presentation for an award. It outlined the course of the military operation and its results, and gave an assessment of the actions of the soldiers. The report was accompanied by lists of names of the chiefs who participated in the operation, information about the quantitative composition of the troops. On the basis of the report, government officials compiled an award "painting", selected an appropriate set of "gold" pieces, and the matter was reported to the tsar. He appointed a person who was instructed to present the insignia and deliver the appropriate speech, and twice - first in front of the chiefs, then in front of all the other soldiers.

The prestige of such awards among the Russian people was high, which foreigners noted not without envy. One of them, who watched the Russian soldiers fight, was amazed: “What can not be expected from an infinite army, which, fearing neither cold, nor hunger, and nothing but the wrath of the king, with oatmeal and crackers, without baggage and shelter, with irresistible patience wanders in the deserts of the north, and only a small amount of money is given to space for the most glorious deed, worn by a happy knight on a sleeve or hat? Civilians also received such awards if they took part in repelling the enemy.

A well-known researcher of the Russian award system V. A. Durov believes that the distribution of coin-like insignia - "gold" - continued until the end of the 17th century. Indeed, for the skillful leadership of the ground forces during the second campaign against Azov in 1696, which ended in victory over the Turkish troops and the capture of this fortress, which opened Russia's access to the South Seas, Aleksey Semenovich Shein received a "gold" of 13 chervonets weighing (then for the first time in Russia he was awarded the highest military rank - generalissimo); Franz Lefort - "gold" in 7 chervonets; Fedor Alekseevich Golovin - in 6 chervonets. Ordinary archers, soldiers and sailors received gilded kopecks.

However, already in the middle of the 17th century, the shortcomings of metrological connections between award signs and coins began to appear. Having received such a distinction, the warrior, of course, could not help but be tempted to dispose of his award. That is why a new type of badge of honor began to be sought.

Under the ruler Sofya Romanova, the first gold medals appeared. They were awarded to Duma General Agey Shepelev and other high-ranking officials who accompanied the royal court when moving from the village of Kolomenskoye near Moscow to the village of Vozdvizhenskos (not far from the Trinity-Sergius Lavra) during the Streltsy rebellion in 1682. On these medals, inscriptions are embossed, informing about this event and its date, the identity of the recipient. Due to the high cost and complexity of manufacturing, such insignia were not widely used. Therefore, for many years, coin-like signs were used for rewarding.

And only under Peter I, this tradition has completely outlived its usefulness. It was he, the great reformer of Russia, who founded the domestic award system that met the needs of the time and the best achievements of medal art.

But even with him, initially, medals served not so much as a reward for personal feat, but as a sign indicating participation in a campaign (i.e., a sign of participation in a collective feat). This was precisely the medal for the victory at Poltava, when the Russian troops led by Peter I utterly defeated the best army of the then Europe under the command of the Swedish king Charles XII and the Ukrainian detachments that joined him, with the traitor and perjurer hetman of the Left-Bank Ukraine Ivan Mazepa at the head.

Poltava medal - round, with a diameter of just over 40 mm, silver. On the front side of it is the chest image of Peter I with a laurel wreath, in armor and a mantle, in the context of which an order ribbon is visible; around the portrait is the royal title. The reverse side depicts a battle scene; along the top edge there is an inscription "For the Poltava battle", at the bottom - in two lines the date "1709 June 27 days". An eyelet was attached to the medal, it was worn on the St. Andrew's (blue) ribbon.

Russian soldiers were rightfully proud of their medals for the victory at Chesma (1770) and the capture of Izmail (1790), participation in the Patriotic War of 1812 and the Sevastopol epic (1854-1855), in the heroic battle of the Varyag cruiser and the Koreets gunboat with the Japanese squadron in 1904, etc.

The traditional round shape of medals in Russia was not established immediately. For example, for the capture of the Turkish fortress Izmail, which was considered impregnable, the Suvorov miracle heroes were awarded a silver oval medal. The award badge of the soldiers who participated in the Swedish campaign of 1788-1790 was an octagon oblong downwards. There were medals in the form of a square with rounded corners. In addition to medals, the lower ranks of the Russian army were awarded crosses. Some believe that the difference between them is purely external: the crosses are the same medals, though of a higher dignity. This is not true. Insignia of the Military Order of St. The Great Martyr and Victorious George (George Crosses) occupied a special position in the award system of Russia.

Orders of the Russian Empire - Orders of the Russian Empire from 1698 to 1917.

Peter I established the first order of Russia in 1698, but for almost a hundred years after that, the award system in the Russian Empire was regulated by decrees for individual orders. The merits of gentlemen from the highest aristocracy and the generals were determined at the personal discretion of the monarch, which did not create problems due to the existence of only 3 orders before the reign of Catherine II. Catherine II, in order to cover wide layers of the nobility, introduced two new orders with 4 degrees each, improving, but also significantly complicating the order system in the state.

The first general law on the orders of the Russian Empire was the “Regulation on Russian Orders” signed by Paul I on the day of his coronation (April 5, 1797), which for the first time officially established the hierarchy of state awards in Russia and created a single body for managing award production. Under the “Cavalier Society”, an office was established, since 1798 the “Chapter of Orders”, headed by its chancellor from among the cavaliers of the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called. In 1832, the Chapter of Orders was renamed the "Chapter of Imperial and Royal Orders".

In the Middle Ages, the word order meant a paramilitary non-governmental organization, whose members wore signs of belonging to this organization. Later, such signs of various degrees began to be awarded to statesmen, whose merits made them worthy (in the opinion of the monarch) to enter the order of those awarded with royal mercy. That is why they said: a sign to such and such an order, a star to such and such an order. In modern times, the concept of the order began to denote the actual award signs. In the first 100 years of its existence, the star for the highest order of St. Andrew the First-Called was made of cloth and sewn onto a caftan, and only by the 19th century began to be made of silver.

The first order of the Russian Empire "Order of the Holy Apostle Andrew the First-Called" was established by Tsar Peter I in 1698 "in retribution and rewarding one for loyalty, courage and various services rendered to us and the fatherland." The order became the highest award of the Russian state for major state and military officials.

The second order, which became the highest award for ladies, was also established by Peter I in 1713 in honor of his wife Ekaterina Alekseevna. Peter awarded this order only to his wife, subsequent awards took place after his death. Formally, the female Order of St. Catherine was in 2nd place in the hierarchy of awards, they were awarded to the wives of major statesmen and military leaders for socially useful activities, taking into account the merits of their husbands.

The third order was established in 1725 by Empress Catherine I, shortly after the death of her husband, Emperor Peter I. The Order of St. Alexander Nevsky became an award one step lower than the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called, to distinguish not the highest ranks of the state.

In 1769, another Empress Catherine II introduced the "Military Order of the Holy Great Martyr and Victorious George", which became the most respected because of its statute. This order was assigned regardless of the officer rank for military exploits:

“Neither a high breed, nor wounds received before the enemy, give the right to be granted this order: but it is given to those who not only corrected their position in everything according to their oath, honor and duty, but, moreover, distinguished themselves by what a special courageous act , or gave wise, and useful advice for Our military service ... ”The officers were proud of the Order of St. George of the 4th class like no other, since it was obtained with their own blood and was a recognition of the personal courage of the recipient.

Also, Catherine II, on the day of the 20th anniversary of her reign in 1782, established the fifth Russian order. The Imperial Order of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Prince Vladimir in 4 degrees became a more democratic award, which made it possible to cover a wide range of civil servants and officers.

The son of Catherine II, Emperor Paul I, in 1797 introduced the Order of St. Anna into the system of awards, the youngest in the hierarchy of Russian orders until 1831. During his short reign, he also established an exotic Maltese cross, which was canceled by his son, Alexander I. Paul I reformed the award system, excluded the Order of St. George and St. Vladimir from state awards during his reign because of hatred for his mother. However, after his death they were restored.

After the inclusion of Poland into the Russian Empire, Tsar Nicholas I found it useful to include Polish orders in the system of Russian state awards since 1831: the Order of the White Eagle, the Order of St. Stanislav and temporarily the Order of Virtuti Military (For Military Valor). The last order was awarded for the suppression of the Polish uprising, awards were made only for a few years.

In the 18th century, stars for orders were made sewn. A star with fabric inserts was embroidered on a leather backing with a thick silver or gilded thread. From the beginning of the 19th century, metal stars began to appear, usually from silver and less often from gold, which replaced embroidered stars only by the middle of the 19th century. Diamonds or so-called diamonds, that is, faceted rock crystal stones, were used to decorate stars and signs. There are stars in which the owner replaced part of the diamonds with diamonds; probably due to financial difficulties.

Until 1826, the salary of a cavalier of the Russian order of any degree gave the recipient the right to receive hereditary nobility (it was not a sufficient condition, but a good reason). Since 1845, those who were awarded only the orders of St. Vladimir and St. George of any degrees received the rights of hereditary nobility, while other orders required the highest 1st degree. By a decree of May 28, 1900, those who were awarded the Order of the 4th degree of St. Vladimir received the rights of only personal nobility.

On November 10, 1917, by the Decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR "On the destruction of estates and civil ranks", the awarding of orders and medals of the Russian Empire in Soviet Russia was discontinued. However, the heads of the Russian Imperial House (House of Romanov) in exile continued to bestow a number of awards from the Russian Empire. Information about such awards is contained in the article Awarding titles and orders of the Russian Empire after 1917.

Seniority and order of awarding orders.

The procedure for awarding and seniority of orders were enshrined in law in the Code of State Institutions and separately for military orders in the Code of Military Decrees. Below is the seniority of the orders according to the Code of Institutions of 1892 (senior orders above):

Order of St. Andrew the First-Called Order of St. Catherine

Order of Saint Vladimir Order of Saint George

Order of Saint Alexander Nevsky

Order of the White Eagle

Order of Saint Anne

Order of Saint Stanislaus

Notes:

Order of St. Catherine, as an exclusively female order, was outside the general hierarchy; in terms of its status, it can be considered at the level of the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called.

Order of St. George is also considered outside the hierarchy, as an order exclusively for military merit, in its status it corresponds to the Order of St. Vladimir, and according to the rules of wearing it is second only to St. Andrew the First-Called.

Speaking about the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called, two significant points should be mentioned.

Firstly, each person awarded this order automatically became a holder of four other orders - St. Alexander Nevsky, the White Eagle, St. Anna 1st degree and St. Stanislav 1st degree, the signs of which he received simultaneously with the signs of the Order of St. Andrew First-Called (if he did not have these orders before). This order was established in 1797 (in relation to the orders of St. Alexander Nevsky and St. Anna 1st degree and supplemented in 1831 in relation to the Order of the White Eagle and in 1865 - to the Order of St. Stanislav 1st degree ).

Secondly, in 1797 it was established that the order of St. Andrew the First-Called was received by all members of the imperial family - men, and the great princes (sons and grandsons of the emperor) received it at baptism, and the so-called princes of imperial blood (from the great-grandchildren of the emperor) when they reach the age of majority.

The following gradualness (order) of awarding orders was envisaged:

St. Stanislaus III degree;

St. Anne III degree;

St. Stanislaus II degree;

St. Anne II degree;

St. Vladimir IV degree;

St. Vladimir III degree;

St. Stanislaus I degree;

St. Anne, 1st class;

St. Vladimir II degree;

White Eagle;

Saint Alexander Nevsky;

Saint Alexander Nevsky with diamond jewelry.

The Orders of St. Anne of the 4th degree and the Order of St. George of all degrees as military awards did not participate in the general gradualness of the award. The highest orders of Andrew the First-Called, St. Catherine, St. Vladimir of the 1st degree was also excluded from the legislatively fixed list of gradualism, these orders were awarded personally by the emperor at his discretion. For other orders, the principle of gradual awarding from the lowest order to the highest was observed, subject to the corresponding length of service and the correspondence of the rank.

The sequence could be broken. In the form of an initial award, it was allowed to honor directly to the senior orders, bypassing the younger ones, in cases where the recipient held a position of a sufficiently high class according to the table of ranks and was in a certain rank. Cavaliers of the Order of St. George of the 4th degree, who served in officer ranks for at least 10 years, were allowed to present Stanislav of the 2nd degree, bypassing the 3rd degree of the orders of Stanislav and Anna.

The Order of St. John of Jerusalem (Maltese Cross) - was introduced in Russia by Paul I in 1798 and taken out of the hierarchy of Russian orders as a special award. During the reign of Paul I, it was considered the highest award in Russia, but without a state-fixed seniority.

Order of Military Dignity (Virtuti Militari) - the youngest order only in 1831-1835. Formally, it was not included in the hierarchy of state awards as established for a one-time event, for the suppression of the Polish uprising.

Women's orders.

Order of Saint Catherine

Insignia of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Princess Olga (the only award took place in 1916)

Orders for non-Christians.

Since August 1844, on the awards that were presented to non-Christian subjects, the images of Christian saints and their monograms of St. George, St. Vladimir, St. Anna, etc.) were replaced by the state emblem of the Russian Empire - a double-headed eagle. This was done "so that when awarding Asians (hereinafter all non-Christians) to awards, their religion was always signified." In 1913, with the adoption of a new statute of the Military Order for the Order of St. George and the George Crosses, the image of a horseman slaying a dragon and his monogram was returned.

Principles of the reward system.

The award system of the Russian Empire was based on several principles:

1. Awarding with orders, subdivided into several degrees, was carried out only sequentially, starting from the lowest degree. This rule had practically no exceptions (except for only a few cases in relation to the Order of St. George).

2. Orders awarded for military exploits (except for the Order of St. George) had a special distinction - crossed swords and a bow from the sash.

3. It was found that the orders of lower degrees are removed upon receipt of higher degrees of this order. This rule had an exception of a fundamental nature - orders awarded for military exploits were not removed even in the event of receiving higher degrees of this order; likewise, holders of the orders of St. George and St. Vladimir wore the insignia of all degrees of this order.

4. The opportunity to receive an order of this degree again was practically excluded. This rule has been observed and has been steadily observed to this day in the award systems of the vast majority of countries (“innovations” appeared only in the Soviet award system, and after it in the award systems of a number of socialist countries).

Awards of the White Movement.

Awards of the White Movement - a set of awards and distinctions for the fight against the Bolsheviks, established in the White Movement during the Civil War.

Awards and distinctions were established by various governments and military leaders of the White Movement. The most famous of them are the Order of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, the badge of the 1st Kuban (Ice) campaign, as well as the insignia of the Military Order "For the Great Siberian Campaign". There were other orders, medals and insignia, established, including after the end of the Civil War, in exile.

USSR awards.

The decree stated that "this insignia is awarded to all citizens of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic who have shown special bravery and courage in direct combat activities." This was the beginning of the award system of the Soviet state. The first order of the RSFSR could be awarded to any of its citizens, if he deserved it in battle. The establishment of the Order of the Red Banner was of great educational importance. The memo issued by those awarded this order stated:

“He who wears this high proletarian insignia on his chest should know that he has been singled out from among his equals by the will of the working masses, as the most worthy and best of them.” The people who were awarded the Order of the Red Banner were called the Red Banner, they enjoyed universal honor and respect, as people of high courage, courage and selfless devotion to their homeland. The rest of the fighters and commanders were equal to the Red Bannermen. The Order of the Red Banner was awarded to a significant number of participants in the civil war, military operations against foreign invaders and in the elimination of all kinds of anti-Soviet gangs.

Heroic deeds in battles with the enemy were performed not only by individual fighters and commanders, but also by entire military units and formations. In connection with this decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of May 8, 1919, it was established that the Order of the Red Banner could also be awarded to military units that distinguished themselves in battle. The decree stated: "... The Order of the Red Banner may be awarded to the military units of the Red Army for special distinctions rendered in battles against the enemies of the Republic, in order to strengthen it on the existing revolutionary banners." After the decree was issued, many military units were awarded this high award and became known as the Red Banner.

Due to the fact that during the terrible years of the civil war, many awarded the Order of the Red Banner continued to show examples of courage and courage in battles with the enemies of the Motherland, by a decree of May 19, 1920, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee established the repeated awarding of this order. The decree read: “... Keeping in mind that many red fighters, already awarded the Order of the Red Banner, which is now the only revolutionary insignia, once again render outstanding military feats worthy of encouragement in real military suffering, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Workers' Soviets , Peasant, Cossack and Red Army Deputies in its meeting decided:

1. Establish for the distinguished defenders of the socialist Fatherland, who have already been awarded the Order of the Red Banner for previously committed feats, without introducing its degrees, to re-award this order.

The decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of September 16, 1918, which established the Order of the Red Banner, provided for the awarding of this order only to citizens of the Russian Federation. On the basis of the Declaration of the Peoples of Russia, adopted by the Council of People's Commissars on November 15, 1917, other peoples of our multinational Motherland proclaimed the creation of independent Soviet republics.

Following the example of the government of the RSFSR, the governments of a number of Soviet republics also established orders to reward individuals who distinguished themselves most in the defense of these republics from enemies of Soviet power. So, in 1920-1921. Orders were established: "Red Banner" - in Georgian, "Silver Star" and "Red Star" - in Armenian, "Red Banner" - in Azerbaijan, "Red Banner" - in Khorezm and "Red Star" - in the Bukhara Soviet Republics . The governments of these republics awarded orders to many fighters and commanders of the Red Army for their distinction in the fight against the interventionists, White Guards and bands of Basmachi.

During the years of the Civil War, in addition to the Order of the Red Banner, there was another type of award - the Honorary Revolutionary Weapon, established by the decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the RSFSR of April 8, 1920. The Honorary Revolutionary Weapon, as an exceptional award, was established to reward senior officers of the Workers 'and Peasants' Red Army for special combat distinctions in the army. It was a saber (dagger) with a gilded hilt and a badge of the Order of the Red Banner attached to the hilt.

On December 30, 1922, a congress of Soviet delegations from the Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian Soviet Republics and the Transcaucasian Federation, which included the Azerbaijani, Armenian and Georgian Soviet Republics, gathered in Moscow. The congress adopted a historic decision to form the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The Congress approved the Declaration and Treaty on the Formation of the USSR. Somewhat later, in addition to those mentioned above, other republics of our Motherland also became part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

In connection with the formation of the USSR, the Order of the Red Banner became, according to the Decree of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR of August 1, 1924, the same for the entire Soviet Union. The right to award the order belonged to the Central Executive Committee of the USSR. The awarding of the previously existing Order of the Red Banner of the RSFSR and orders of other republics was discontinued, but the right to wear them was retained by those awarded.

Later, in the Decree of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR of August 13, 1933, it was stated that “in view of the historical significance of the Order of the Red Banner of the RSFSR, as well as the military orders of other union republics - the Red Banner, Red Crescent, Red Star, the replacement not to produce them for the Orders of the Red Banner of the USSR, but to extend the rights and benefits granted to those awarded the Order of the Red Banner of the USSR to persons awarded with these orders.

This is a brief history of the establishment of the first Soviet order.

On April 6, 1930, another military order was established - the "Red Star" to reward military personnel, military units and formations for their merits in defending the Motherland and strengthening its defense capability both in peacetime and in wartime.

In 1934, the Soviet government established the highest degree of distinction - the title of "Hero of the Soviet Union". This title is awarded to citizens who have accomplished an outstanding heroic deed for the glory of our Motherland. Somewhat later, for persons awarded this highest degree of distinction, a special distinction was established - the Gold Star medal.

Thus, by the beginning of 1936, the highest degree of distinction was established in our country - the title of Hero of the Soviet Union and five orders were established: the Order of Lenin, the Red Banner, the Red Banner of Labor, the Red Star and the Badge of Honor; the Regulations on the title of Hero of the Soviet Union and the Statutes of the above-mentioned orders were approved. However, the country did not have a single fundamental document that determined the procedure for awarding orders, the rights and obligations of those awarded, and other issues related to awarding orders of the USSR. Such a document was the General Regulations on the Orders of the USSR, approved by the Decree of the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR of May 7, 1936. The publication of this legislative act was an important event in the development of the award system of the USSR. He established that the orders of the USSR are the highest award for special merits in the field of socialist construction and defense of the USSR; that orders, along with individual citizens, may be awarded to military units, formations, enterprises, institutions, organizations; that those awarded with the Order of the USSR can be repeatedly awarded the same or another Order of the USSR for new merits. The procedure for awarding orders was established, it was emphasized that persons awarded orders should serve as an example of the fulfillment of all duties imposed by law on citizens of the USSR, a number of benefits were also established for the recipients: monthly payment of certain sums of money for orders, a discount when paying for living space, preferential calculation years of service at retirement, exemption from income tax, free travel once a year back and forth by rail or boat, free travel by tram, etc. Subsequently, these benefits were abolished, as will be discussed in more detail below.

The General Regulations on the Orders of the USSR summarized all issues related to the awarding of orders that existed by that time, which gave this document the significance of the basis of the award system of the Soviet state. This legislative act, with some changes, existed for more than 43 years, until the approval in 1979 of the General Regulations on Orders, Medals and Honorary Titles of the USSR.

Orders of the USSR, established in our country in the first two decades of Soviet power, and awarding the working people with them, were a significant incentive for the Soviet people in their work to restore and develop the national economy, strengthen the defense capability of the Motherland and build socialism. Only during the years of the civil war, as well as during the period of restoration of the national economy destroyed by the war and during the years of the first five-year plans, about 153 thousand awards were made.

In the mid-1930s, the international situation became noticeably more complicated. After Hitler came to power, Germany armed itself at an accelerated pace. In 1935, Italy unleashes hostilities in Ethiopia. In 1936, with the support of Germany and Italy, a fascist rebellion broke out and a civil war began in Spain. In 1937, in the Far East, Japan resumes hostilities in China. In 1937, Italy joins the "anti-Comintern pact" concluded between Germany and Japan. The Soviet government, taking into account the difficult international situation and the danger of military conflicts, took measures to strengthen the defense capability of the USSR and showed concern for increasing the combat readiness of the Armed Forces. This was reflected in the award system of the Soviet Union.

On January 24, 1938, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR established the first Soviet medal - "XX Years of the Workers 'and Peasants' Red Army". The very fact of establishing a jubilee medal on the eve of the 20th anniversary of the Red Army was a recognition of the merits of Soviet soldiers and an expression of people's love for them.

In the same year, two more medals were established - "For Courage" and "For Military Merit" - to reward the military personnel of the Red Army, the Navy and the border troops for military exploits committed during the period of hostilities and while protecting the state border of the USSR.

On June 22, 1941, the peaceful work of the Soviet people was interrupted by the treacherous attack of Nazi Germany. A war unprecedented in the history of mankind began. Fierce battles between the Red Army and hordes of Nazi troops and troops of the allies of Nazi Germany unfolded on the front from the Black Sea to the Barents Sea. In the first period of the war, the Nazi invaders succeeded in seizing part of the territory of the Soviet Union. True, their initial plans for a lightning-fast defeat of the Red Army and a quick victorious end to the war completely failed.

In the most difficult battles with the Nazi hordes, the manifestation of courage, courage and heroism by Soviet soldiers and commanders took on an unprecedented scale, truly a mass character. Bright pages in the history of the Great Patriotic War included the heroic defense of Odessa, Sevastopol, Kyiv and Moscow, the defense of Stalingrad and the defeat of the largest grouping of Nazi troops in the area of this city, the courageous defense of besieged Leningrad and the defeat of the Nazis on the Kursk Bulge, the liberation from the Nazi invaders of Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova and the Baltics. The exploits of Soviet soldiers will never be forgotten by the peoples of many European countries, liberated from Hitler's enslavement by the valiant troops of the Red Army and the Navy. To reward courageous soldiers who showed miracles of heroism in the defense of these cities, the medals "For the Defense of Kyiv", "For the Defense of Moscow", "For the Defense of Leningrad", "For the Defense of Stalingrad", "For the Defense of the Caucasus", "For the Defense of the Soviet Arctic", "For the defense of Sevastopol" and "For the defense of Odessa". Hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers were awarded these high awards.

During the Great Patriotic War, the Soviet government paid special attention to the issue of awarding orders and medals of the USSR to soldiers, sailors, sergeants, foremen, officers, generals and admirals of the Soviet Armed Forces, partisans and members of the underground who fought the enemy both at the front and in the enemy rear , in the temporarily occupied territory.

The first Soviet order established during the beginning of a bloody war with the German occupiers was the Order of the Patriotic War, which was established on May 20, 1942. Later, the so-called "commander" orders were established, named after the great Russian commanders - Kutuzov, Suvorov, Bogdan Khmelnitsky, Alexander Nevsky, Admiral Ushakov, Admiral Nakhimov. (History of the order) These orders were awarded to officers and generals for the development and successful implementation of military operations, as a result of which the superiority of our troops over the enemy was achieved. The plans also included the establishment of the Order of Denis Davydov, which was planned to be awarded to the leaders of large partisan formations operating behind enemy lines, but for some reason this order was not established.

November 8, 1943 was a significant day. Against the background of the radical change that had already occurred in the Great Patriotic War, the highest military order "Victory" was established, intended to reward the outstanding commanders of that war, who provided a radical change in the course of hostilities. On the same day, the Order of Glory was established, intended to reward only privates and sergeants of the Red Army. This order was affectionately called the "soldier's" order. He continued the traditions laid down as early as 1807 with the establishment of the Badge of Distinction of the Military Order (the so-called "St. George's Cross"). This can be seen even in the fact that the St. George Ribbon, traditional for the Russian army, was adopted as the ribbon of this order.

The war rolled further and further to the West every day. In 1944, our troops crossed the State Border of the USSR in some areas. The liberation of Europe began. In the battles for the freedom of the countries of Eastern Europe, our soldiers also showed the greatest courage and heroism, especially when taking fortified cities such as Konigsberg, Vienna, Budapest, and Berlin. For the soldiers who distinguished themselves in this, in June 1945 the medals "For the capture of Budapest", "For the capture of Vienna", "For the capture of Koenigsberg", "For the capture of Berlin", "For the liberation of Prague", "For the liberation of Warsaw", "For the liberation of Belgrade". And in honor of the victory over Germany, the medal "For the Victory over Germany" was established, which was awarded to all military personnel who took part in the hostilities. And after the defeat of Japan, the medal "For the victory over Japan" was established.

After the end of the Great Patriotic War, to reward military personnel who served in the Armed Forces of the USSR for 10, 15 and 20 years, the medal "For Impeccable Service" of 1, 2 and 3 degrees is established, and in 1976 - the medal "Veteran of the Armed Forces of the USSR" for awarding persons who served in the ranks of the Soviet army for 25 years or more.

Also, commemorative medals were established in honor of the 30th, 40th, 50th, 60th and 70th anniversary of the Soviet Army. These medals were awarded to all officers of the Soviet Army.

Starting from the 20th anniversary of the Victory, for each anniversary of this significant event, commemorative medals were minted, which

History of St. Petersburg

Pre-Petrine era

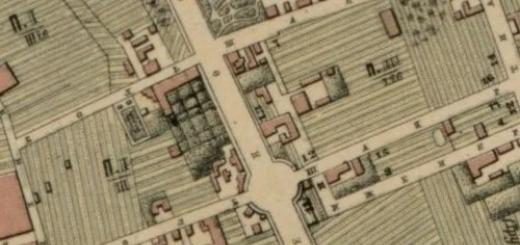

The mouth of the Neva, flooded with water at any strong western wind, until the 14th century was not of strategic interest either to the Russians (the territory of present-day St. Petersburg was then part of the Novgorod land), or to their rivals, the Swedes. And although armed clashes between Novgorodians and Swedes occurred regularly (let us recall the Battle of the Neva in 1240), the first fortress on the Neva was built only in 1300, and a year later the Swedish Landskrona was destroyed by the Novgorodians. Since 1323, the Neva delta has been officially considered Russian territory; together with Novgorod, it became part of Moscow Rus at the end of the 15th century. In 1613, the Swedes managed to capture most of the current Leningrad region: the Swedish province of Ingria was formed here with the capital Nienschanz on the site of the fallen Landskrona.

18th century

In 1700, the Great Northern War began between the Russia of Peter I and the Sweden of Charles XII. In 1703, the Russian flotilla passed the Neva to the bay, on May 16 (27) of the same year Petersburg was founded, and in 1704 - Kronstadt. Peter fell in love with the fortress on the Neva, and he began to visit it often. The idea of building a new European city from scratch seemed fruitful to the tsar. In 1712, Peter moved the court from Moscow to St. Petersburg, which was under construction, in 1721 he proclaimed it the capital of the empire, developed a plan for the city and the principles of its development. It was in St. Petersburg that new higher and central authorities began to work: the Senate, the Synod, and the collegiums. Peter opened the first public museum in the city - the Kunstkamera, as well as the Academy of Sciences and the Academic University. Mostly foreign architects worked in the young capital, and everything had to be not like in Moscow, but rather like in Amsterdam. In 1725 Peter dies. By this time in St. Petersburg - about 40 thousand inhabitants.

As a result of a palace coup, the second wife of Peter, Catherine I (Marta Skavronskaya), came to power, but she ruled for only two years: 1725-1727. Instead of this frivolous woman, the country was led by the “semi-powerful ruler” Alexander Menshikov.

View of the Winter Palace of Peter I

Catherine on the throne was replaced by Peter II (1727-1730), the grandson of Peter the Great, the son of Tsarevich Alexei, who was tortured by him. He was a spoiled teenager who was entirely in the hands of the courtiers from the Supreme Privy Council. Under him, the court moved to Moscow - however, not for long: in 1730, Peter II dies of smallpox, under pressure from the guards, the niece of Peter I, Anna, is erected on the throne.

Anna Ioannovna, a woman of a fierce disposition, came from Courland and ruled Russia for ten years: 1730-1740. Having ascended the throne, she returned the capital to the banks of the Neva. Under her leadership, Pyotr Eropkin created the town-planning structure of the center of St. Petersburg (which, however, did not save the architect from a cruel execution for participating in the so-called Volynsky conspiracy - Anna's reign was generally bloody). The city has preserved numerous buildings of its time: the Kunstkamera, the Peter and Paul Cathedral, the Church of Simeon and Anna.

Anna leaves the throne to the great-nephew of Peter I - Ivan Antonovich of Brunswick. During the year (1740-1741), the country is formally ruled by Anna Leopoldovna, the mother of the two-month-old Ivan VI. The long-term favorite of Anna Ioannovna Ernst Biron, then Burchardt Munnich, then Johann Osterman, is engaged in state affairs with her.

Another coup on November 25, 1741 brings to power the beloved daughter of Peter the Great - Elizabeth. She sends the entire Braunschweig family into exile (later young Ivan will be imprisoned in the Shlisselburg fortress, where he will be killed) and rule the country for two decades: 1741-1761. Elizabeth is a cheerful, full-blooded blonde who loves dancing and hiking. Her brilliant reign was marked by victories over Prussia during the Seven Years' War, as well as the flourishing of the work of Lomonosov and Rastrelli. The Academy of Arts, the Corps of Pages and the first Russian professional drama troupe were founded in St. Petersburg. The population of the city is growing: by 1750 - 74 thousand inhabitants. Under Elizabeth, the Winter Palace appeared (completed shortly after her death), the Sheremetev Palace, and the Smolny Cathedral. The favorite summer residence of the Empress was Peterhof.

Elizabeth leaves the throne to Peter III (1761-1762), the grandson of Peter I, the son of his daughter Anna. Information about the personality of this sovereign is contradictory: his wife (the future Catherine II) described him as a clinical idiot, but many contemporaries considered him a wise legislator. Peter freed the nobles from military service and permitted the open practice of ceremonies by non-Orthodox Christians. In 1762, he was deposed from the throne by his wife and soon killed.

Catherine II(1762-1796) did not have the slightest legal rights to the Russian throne, but she reigned for a long time and successfully. "Catherine's eagles" Rumyantsev and Suvorov smash the Turks, Crimea, Lithuania, Belarus, part of western Ukraine become Russian. Petersburg is also flourishing: by the end of the 18th century, it had almost 220,000 inhabitants. The Hermitage and the Public Library were founded. Granite embankments of the Neva, Moika, Fontanka are being built. The time of the rise of Catherine is the end of the Baroque era: Rastrelli completes the construction of the Winter Palace and retires. Classicism bears fruit in architecture and literature. The Tauride and Marble palaces, Gostiny Dvor, the Bronze Horseman are being built; Charles Cameron works in Catherine's favorite country residence, Tsarskoe Selo. "Felitsa" by Gavriil Derzhavin has been printed, and "Undergrowth" by Fonvizin is being premiered.

The throne is inherited by Paul I (1796-1801), son of Catherine II and Peter III. His mother did not like him, and Pavel repaid her in return, honoring the memory of his murdered father. He devoted his short reign to posthumous revenge on Catherine: he solemnly reburied Peter III in the Peter and Paul Cathedral, and legally forbade women to rule Russia. A notable foreign policy event was Suvorov's European campaigns. The emperor spent a lot of time in summer residences - Pavlovsk and Gatchina. In St. Petersburg, from his reign, the Mikhailovsky Castle, the Bobrinsky Palace, the Mikhailovsky Manege have come down to us. On the night of March 12, 1801, as a result of a palace coup, Pavel was killed in the Mikhailovsky Castle, the throne goes to his son Alexander.

19th century

Alexander I(1801-1825) was brought up by the grandmother-empress as the future ruler of Russia and was probably the most educated Russian emperor. His time is known to us from Leo Tolstoy's "War and Peace" and the first chapters of Pushkin's "Eugene Onegin". Actually, Alexander gave the capital a “strict, slender appearance”. Under him, a period begins, which will later be called the “golden age” of St. Petersburg culture: Batyushkov, Baratynsky, Pushkin, Rossi. Alexander's Petersburg has been preserved with large empire-style inclusions in the city center; in his reign, the Kazan Cathedral, the Stock Exchange, the Smolny Institute were built. The population reaches 386 thousand people in 1818.

After four wars with the French and the burning of Moscow, Russian troops entered Paris in 1813. The guards, which have traveled all over Western Europe, are returning from abroad, full of freedom-loving ideas. Secret societies appear in the guards regiments along the banks of the Fontanka. In November 1825, the childless Alexander I dies. Formally, he should be succeeded by brother Konstantin, to whom the court and guards swear allegiance. However, Konstantin, who entered into an unequal marriage with Princess Lovich, knows about the will of the late Alexander: Nicholas, the third son of Paul, should become the next emperor. The oath is scheduled for December 14 - but Nikolai is unpopular in the guards, and members of the secret society, taking advantage of this, are plotting to stage a coup. At the decisive moment, only a quarter of the guardsmen turned out to be on the side of the rebels. The Decembrists (as the rebels were later called) were surrounded on Senate Square by troops loyal to Nicholas. Arrests began; On July 13, 1826, five leaders of the uprising were hanged on the rampart of Kronverk, and the rest were exiled to Siberia and the Caucasus.

Nicholas I becomes a full ruler for 30 years: 1825-1855. He thoroughly strengthened the power vertical. Loved everything military. Under him, the empire reached the zenith of its foreign policy power, but still, due to the technical backwardness of the army, the Crimean War of 1853-1856 was lost, and Russia found itself in a severe crisis. Railway communication begins to develop: in 1837 St. Petersburg was connected by rail with Tsarskoye Selo, in 1851 with Moscow, although this is not enough for a huge country. In the Nikolaev era, Pushkin and Gogol create; in books and on the streets appear "little man" and "superfluous man" - both alien to the authorities and the huge soulless city. The decoration of the ensembles of the central squares and Nevsky Prospekt is coming to an end, the General Headquarters, the Alexandrinsky Theater, the Mikhailovsky Palace appear. The population of St. Petersburg continues to grow. In 1855, the proud and scrupulous Nicholas, disgraced by the defeat in the Crimean War, dies. Alexander II, brought up by Vasily Zhukovsky, takes the throne.

Alexander II(1855-1881) - the father of the first perestroika. The 1860s become the era of “great reforms” - Alexander freed the peasants from slavery, proclaimed glasnost and the rule of law, softened censorship, introduced local self-government and a jury trial. In St. Petersburg, the first elected city duma appears, which controls the capital's budget. The Varshavsky, Baltiysky and Finlyandsky railway stations were opened, a water supply system was put into operation, horse-drawn railway rails were laid along the main streets. The scope of housing construction is indescribable, the part of the center that lies behind the Fontanka is being actively built up. The Mariinsky Theater opens. In 1881, there were 861 thousand inhabitants in St. Petersburg.

The era of Alexander II is also the time of great Russian art. Dostoevsky, Leskov, Goncharov, the composers of The Mighty Handful are creating in St. Petersburg; Here Mendeleev comes up with a periodic system, the Wanderers reform painting.

Reforms, as always, enrich the few. A murmur is heard among the people. Police control is weakening. Attempts to "freeze" Russia, to stop the reforms, cause even greater displeasure - especially among the intelligentsia and students. In 1861, the first anti-government leaflets appeared; in the 1870s, unprecedented organizations of professional political terrorists appeared: Land and Freedom and Narodnaya Volya. After several unsuccessful assassination attempts, Alexander II is still killed at the Mikhailovsky Garden (March 1, 1881) - the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood was built on this site.