If these are the necessary prerequisites for creative democracy (see “N.Z.” pp. 5, 8), then it is clear that in their absence democracy ceases to be a creative state form, but becomes corrupting. Do we want such disintegrating formlessness for Russia? Of course not. Our whole task at first will be to shorten as much as possible the period of inevitable chaos that will spill out in Russia after the fall of totalitarian communism. The absurd and vitally harmful clampdown was too long; the terror he used was too cruel and merciless; the injustice was immense; the violence was defiant; The bet was always placed on unscrupulous sadists who bought scoundrels, charmed fools and eradicated precious Russian people. Indignation was “driven inside”, protests were filled with blood. As soon as people sense that “the regime is over,” everything will boil over.

What will this “boiling” be expressed in? Is it worth describing? One thing can be said: the extermination of the best Russian people left life and freedom for the worst; the system of fear, groveling, lies, flattery and violence systematically lowered the moral level and brought to the surface of souls ancient sediments of cruelty, the legacy of the Tatars. It is necessary to foresee the terrible, which no persuaders will stop, which will be beyond the capabilities of all non-resisters, as such. Only a national dictatorship, relying on loyal military units and quickly raising up cadres of sober and honest patriots from among the people, can shorten the period of arbitrary revenge, wanton reprisals and corresponding new destruction. An attempt to immediately introduce “democracy” will prolong this chaotic boiling for an unforeseen period of time and will cost the lives of a huge number of people, both guilty and innocent.

Whoever does not want this must demand an immediate national dictatorship. Yes, they will answer me, but this dictatorship must be “democratic”! This concept can have three different meanings.

1. “Democratic dictatorship” can mean, firstly, that the dictator must be a party democrat.

There is no reason to expect good from such a dictator in Russia. We saw “the full power” in the hands of such democrats: we marveled at their eloquence, heard their categorical refusals to pacify the pogroms, saw how they “defended” their constituent assembly and how they disappeared abroad without a trace. These people are born for reasoning, discussion, resolutions, intrigue, newspaper articles and escape. These are people of pose, not of will; people of the pen, not of power; people of sentiment, appealing only to themselves. And a dictator saving a country from chaos needs: will, restrained by a sense of responsibility, a formidable presence and all kinds of courage, military and civil. Russian formal democrats are not at all created for Russia; they belong in Denmark, Holland, Romania; their mental horizon is completely unsuitable for a great power; their trepidation for the “purity” of their sentimental freedom-loving clothes is anti-state; their penchant for all kinds of amnesty and international solidarity, their adherence to traditional slogans and outdated schemes, their naive confidence that the popular mass consists everywhere and always of born and well-intentioned democrats - all this makes their leadership in post-Bolshevik Russia extremely dangerous and hopeless. Among them there is not a single Noske, who coped with the Kapp coup in Germany; not a single Mock, as in France, not a single Scelba, as in Italy, not a single Salazar, as in Portugal. And if they don’t see this in the United States, then people there are simply blind.

2. “Democratic dictatorship” can mean, firstly, that the matter will be transferred to the hands of a small collegial body (directory), which will be subordinate to a large collegial body (co-optation parliament, recruited from all the February bison with the addition of propagandized emigrant youth and defected communists).

From such a “dictatorship” one can expect only one thing: the earliest possible failure. A collegial dictatorship is generally an internal contradiction. For the essence of dictatorship is in the shortest decision and in the sovereignty of the decider. This requires one, personal and strong will. A dictatorship is essentially a military-type institution: it is a kind of political commandery, requiring an eye, speed, order and obedience. Seven nannies have a child without an eye. Medicine does not entrust surgery to a collective body. Gofkriegsrat is a simply disastrous establishment. The discussion seems designed to waste time and miss all opportunities. The collegiality of the body means multi-willedness, disagreement and lack of will; and always an escape from responsibility.

No collegial body will master chaos, for it in itself already contains the beginning of disintegration. In normal state life, with a healthy political system and with the availability of unlimited time, this beginning of disintegration can be overcome with success in meetings, debates, voting, persuasion and negotiations. But in the hour of danger, trouble, confusion and the need for instant decisions and orders, a collegial dictatorship is the last of the absurdities. Only those who fear dictatorship in general and therefore try to drown it in collegiality can demand a collegial dictatorship.

The Romans knew the saving power of autocracy and were not afraid of dictatorship, giving it full, but urgent and targeted powers. The dictatorship has a direct historical calling - to stop the decomposition, block the road to chaos, and interrupt the political, economic and moral disintegration of the country. And there are periods in history when being afraid of a one-man dictatorship means leading to chaos and promoting decay.

3. But “democratic dictatorship” can have another meaning, namely: it is headed by a single dictator, relying on the spiritual strength and quality of the people he saves.

There is no doubt that Russia will be able to revive and flourish only when the Russian people's power in its best personal representatives - all that there is of it - joins in this matter. The peoples of Russia, sobered up by humiliation, coming to their senses in the many years of hard labor of communism, having realized what a great deception is hidden behind the slogan of “state self-determination of nationalities” (a deception leading to fragmentation, weakening and enslavement from the rear!), must rise from their beds and shake off the paralysis Bolshevism, fraternally unite their forces and recreate a united Russia. And, moreover, in such a way that everyone feels not like runts and slaves, intimidated by a bureaucratically totalitarian center, but into loyal and self-active citizens of the Russian Empire. Faithful - but not slaves or serfs, but faithful sons and subjects of public rights. Amateurs - but not separatists, or revolutionaries, or robbers, or traitors (after all, they are also “amateurs”...), but free builders, workers, servants, citizens and warriors.

This bet on the free and good power of the Russian people must be made by the future dictator. At the same time, the way up from the very bottom should be open to quality and talent. The necessary selection of people should be determined not by class, not by estate, not by wealth, not by slyness, not by behind-the-scenes whispers or intrigues and not by imposition from foreigners - but by the quality of a person: intelligence, honesty, loyalty, creativity and will. Russia needs conscientious and brave people, not party promoters and not hiring foreigners...

And if democracy is understood in this sense, in the sense of national self-investment, national service, creative initiative in the name of Russia and qualitative upward selection, then it will truly be difficult to find a decent person, a Christian, a state-minded patriot who would not say with everyone else: “ Yes, in this sense I am also a democrat.” And the future Russia will either realize this and show genuine creative people’s power, or it will spread out, disintegrate and will not exist. We believe in the former; gentlemen dismemberers are clearly seeking the second.

So, the national dictator will have to:

1. reduce and stop chaos;

2. immediately begin quality selection of people;

3. establish labor and production order;

4. if necessary, defend Russia from enemies and robbers;

5. put Russia on the road that leads to freedom, to the growth of legal consciousness, to state self-government, greatness and the flourishing of national culture.

Is it possible to think that such a national dictator will emerge from our emigration? No, there's no chance of that. There should be no illusions here. And if, God forbid, Russia were to be conquered by foreigners, then these latter would install either their own foreign tyrant, or an emigre collegial dictatorship - for a greater shameful failure.

Internet program "Finding Meaning"

Topic: "Dictatorship"

Issue #139

Stepan Sulakshin: Good afternoon friends! Last time we studied the space of meaning of autocracy. It is logical to continue this semantic space by working with the term “dictatorship”. But there is no need to immediately try to hear hints about our Russian reality. We are interested in a precise understanding of what “dictatorship” is. Vardan Ernestovich Bagdasaryan begins.

Vardan Baghdasaryan: I'll start with a quote from Lenin. Nowadays it is not customary to turn to the classics of Marxism-Leninism, but it seems to me that the Marxist tradition has contributed a lot to the methodology of understanding the phenomenon of “dictatorship” in order to dispel the propaganda, manipulative myths associated with this category.

Lenin in his article “On Democracy and Dictatorship” writes: “The bourgeoisie is forced to be hypocritical and call the (bourgeois) democratic republic “power of the whole people” or democracy in general, or pure democracy, which in reality is a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, a dictatorship of the exploiters.

The current “freedom of assembly and press” in a “democratic” (bourgeois-democratic) republic is a lie and hypocrisy, because in reality it is the freedom for the rich to buy and bribe the press, the freedom of the rich to solder the people with bourgeois newspaper lies, the freedom of the rich to keep their “ property" landowners' houses, the best buildings and so on."

Lenin, and before that Marx, described the category of “dictatorship” as hypocritical and came to the conclusion that non-dictatorship states do not exist. Indeed, in relation to the category of “dictatorship”, two approaches can be traced: according to the style of government, it is a dictatorial state, and according to the actor, it is the exercise of power. Let's look at both of these approaches.

It must be said that, due to its etymological origin, this word does not carry any negative load. In Ancient Rome, it literally meant “sovereign,” and one of the titles of the Roman emperors was the title “dictator,” dictator - in the sense of ruler.

Last time we looked at the category of “authoritarianism”. Very often, dictatorship and authoritarianism are considered the same thing, but they are different things. A dictatorship can also be a democratic dictatorship. For example, during the Great French Revolution, the National Convention exercised dictatorial functions, and few people question this, but all decisions and dictatorial powers were exercised in a completely collegial manner.

So, if we talk about the style of government, then the directive style of government is often identified with dictatorship. Here the question arises: what if this arrangement continues, if not the directive style of government? What other management styles are there? Subsequently, a stimulating management system arises - not through directives, but through incentives.

Now, in the conditions of the information society, a contextual control system is emerging, that is, to a greater extent, a control system through the programming of consciousness. But, of course, both incentive and contextual management systems still continue this tradition. There are no fundamental anthological contradictions here.

Under capitalism, as the classics of Marxism showed, the worker, since he does not have the means of production, is forced to hire out. It would seem that he has been granted freedom, but in reality there are economic mechanisms at work that, in fact, make him unfree. This more sophisticated form is, in fact, not much different from the form of directive government.

Now that the beneficiaries have full control of media resources, the system is essentially the same. An illusion arises that a person makes decisions himself, that he, as a subject, creates his own agenda, but in reality, due to the emergence of new cognitive schemes and control mechanisms, his behavior is also programmed by the controlling actor who owns these media resources. That is, technology is developing, but essentially this building system, which was defined as directive, dictatorial, does not change.

The second position is that there is an aggregated model for the exercise of power, that is, the state takes into account the interests of many, which means it aggregates them. There is another model, which is based on the implementation of the interests of one position or one person, and so on.

This means that the first position is aggregated, the second position is associated with a dictatorial position. But here I appeal to the works of both Lenin and Marx, which showed that, in fact, there are no non-dictatorial states. The whole question is who this actor is. In Marxism, this category was revealed through class interests, which means that the whole question is which class, which social group exercises these powers of power.

When we talk about class interests, the model of economic man is set, that class consciousness and property status dominate and determine. But let's look at it from an ideological position using this methodology.

The majority of the population is in favor of sovereignty, the minority is against this sovereignty. There are certain value positions in which there is some kind of consolidation. If the state proceeds from value positions, then these value positions are always associated with some group, and it always turns out that, due to the heterogeneous nature of society itself, the minority does not implement this value position. This means it will be a dictatorship of the majority.

When Marx, and subsequently Lenin, opened the category “dictatorship of the proletariat”, they talked about it. In traditional methodology, this term seems to be negative - there is democracy, and there is dictatorship, but in the Marxist tradition, the dictatorship of the majority is true democracy. This removes the negativism and manipulativeness initially inherent in this concept.

Indeed, in the first constitutions - in the Constitution of the RSFSR of 1918, in the Soviet Constitution of 1924, the categories “dictatorship”, “dictatorship of the proletariat” were present, but this dictatorship of the proletariat was revealed precisely as a democratic system.

I will quote the provision of the 1924 Constitution: “Only in the camp of the Soviets, only under the conditions of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which rallied the majority of the population around itself, was it possible to completely destroy national oppression, create an environment of mutual trust and lay the foundations for fraternal cooperation of peoples.”

Today, the Chinese experience is often cited. In the People's Republic of China, when the new Constitution was adopted during the time of Deng Xiaoping, the category “dictatorship of the proletariat” sounds like “democratic dictatorship of the people.”

The category of “democratic dictatorship of the people” is reflected in the first article of the Chinese Constitution. The Chinese Constitution begins with the words: “The People's Republic of China is a socialist state of the democratic dictatorship of the people, led by the working class and based on the alliance of workers and peasants.”

So, the main thing is that there are no non-dictatorial states, the only important thing is whether this dictatorship comes from the interests and positions of the majority or from the interests and positions of the minority.

Stepan Sulakshin: Thank you, Vardan Ernestovich. Vladimir Nikolaevich Leksin.

Vladimir Leksin: Most often, the concept of “dictatorship” is associated with the concept of “dictator”. This is the most common everyday understanding of this term. Indeed, a dictator is a person who dictates, that is, utters something that everyone must follow.

Dictatorship in a broader sense is a political science concept that is very convenient for explaining many processes. And if it is not academic, then it is still, as it were, divorced in everyday consciousness from the fact that if there is a dictatorship, there is also a dictator.

Still, most often dictatorship is understood as an abnormally high personification of power, when such a type of political system and political society is created that there is a hypertrophy of power and the absorption of all institutions of civil society by one person. Moreover, this one person is a very interesting topic.

Now the real power of one person, the dictatorial line exists, no matter what the state is, at least at the level of representative offices. And, naturally, to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the Victory, the first persons of these states came to Moscow, who in everyday consciousness, and in real life, embody all the power in this state, be it the Senate, parliament, congress, some kind of public meeting and etc.

In any case, one person represents all the energy, all the essence and ideology of a particular state, and from this point of view he may well be considered a dictator. We know that the leaders of, say, the largest corporations are dictators in the full sense of the word.

In any organization, this dictatorial system really exists, only it is no longer a political organization of society, but simply management. This is what is called unity of command in Russian. This unity of command is a pragmatic, or something like, managerial type of dictatorship and dictatorship.

Now more than ever it is clear that the concept of dictatorship and dictator as a personified form of power has three hypostases. The first hypostasis is real. These are real dictators who can really be called “father of the nation”, “Fuhrer”, “leader” and so on.

One of the last really active dictators was Muammar Gaddafi. Many people called Fidel Castro a dictator, who was an absolutely amazing dictator, because, unlike, say, our country, his portrait did not hang in any institution, and there was no sculpture of him.

Nevertheless, these people maximally expressed the essence of power and, most importantly, actually controlled this power. These are real dictators, real delegated dictatorship, delegated dictatorship, and this is a very curious thing.

When there is a certain figure to whom various political, economic, international and so on intentions are practically thrown, she only expresses this, gaining either the love or dislike of the people, but this person is a figurehead expressing the essence of power. Such dictators are now the majority. I think that there are many such people in our history.

Well, the third hypostasis is a hereditary dictatorship. These are the monarchical dictatorships of previous years, these are the dictatorships of the recent past that existed in Latin America, and so on. These are three different types, but they have one thing in common.

By the way, this sign is very clearly expressed in our country. This is what can be called "manual control". Along with the fact that there is a legitimate process for the adoption of laws, to which everyone submits, including the dictator, who always says that he acts either on behalf of the Constitution - the basic law, or in accordance with the laws, he stimulates most of these laws, and sometimes actually creates them, and they then become legitimate from a legal point of view.

But first, manual control is a very clear indicator of dictatorship and the activities of a dictator, when massive orders are issued to everyone and everything, and they must be carried out. This is basically a somewhat belated reflection on the most pressing events that are occurring, and so on.

So what is dictatorship in our time - the norm or a relic? Even in ancient times, Heraclitus said that, having perfect knowledge, one can practically control absolutely everything alone. That is, having all the information in hand, acting within the framework of the law, it would probably really be possible to manage everything, if not for one “but.”

There is a very complex structure of social and international relations within the country. Everyone is connected to everyone else, everyone is connected to each other, but someone establishes this connection, and someone, undoubtedly, is more important than others in this connection.

At one time, one of the obvious dictators, Mussolini, pronounced a very clear formula on this matter. He said that the more complex a civilization becomes, the more individual freedom is limited. This is a very reasonable observation of his, and to some extent it now justifies the activities of so-called dictatorships and dictators who believe that in all the diversity of interests, motivations, actors that now exist in the field of domestic politics, there must be something called “ with a hard, firm hand." This is another basis for dictatorship. Thank you.

Stepan Sulakshin: Thank you, Vladimir Nikolaevich. We are looking at an interesting term today. This is a classic term that allows you to see and work out all the stages of the methodology for discovering these meanings. After all, we not only understand individual terms, but also hone the methodology itself, the very technique of discovering meanings in the future. There are a lot of categories of words, and in the practice of every person, in his creative life, they will arise many times.

What would I like to point out here? That, as a rule, meaning is found through human experience, that is, through an enumeration of all manifestations of this category in a variety of contexts. And there are traps here, for example, the trap of endlessly listing what it is, then not collapsing into a formula, a trap that is connected, figuratively speaking, with the fact that “our indignant mind is seething.”

That is, there are some categories that are so bright, dramatic or tragic in some of their certain rather narrow manifestations that it distorts the whole picture. And behind these bright manifestations, which are very important for a person because of their tragedy, other manifestations of this category are lost, and the transition to generalization, synthesis of a semantic formula, and definition of the definitions of this category becomes difficult.

What associations does the word “dictatorship” evoke in our heads, for example, the dictatorship of the proletariat, the Red Terror, the civil war, Stalinism and other bright, seemingly semantic projections, spots that actually obscure the semantic essence, sometimes even the logical and technical essence of this very concept ?

Let's try to walk along the road, freeing our minds from seething with such distortions. So, to what semantic space of human activity does this category belong? Of course, to power and control. And, again, maybe a dictator is the head of a family, maybe a dictator in some company, but these are secondary manifestations that do not relate to the main semantic content of this category.

After all, this is power and control. And the genesis of this category points precisely to such an approach. In power and control, as a very complex space, there are many semantic cells, the mosaic of which in this space is useful for a particular term that we want to define.

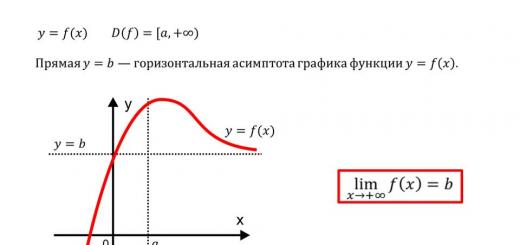

In this case, the most important thing is three elements, three links in the chain. If this is power and management, then management is necessarily making a decision - one, making a decision - two, and executing a decision - three. And this three-handed thing allows, for example, to construct a series, to see the relationship and precise semantic definitions of such categories as democracy, autocracy and dictatorship, to see what unites them, and something specific that separates them, which is what gives the original, unique and absolutely a specific semantic profile of a particular term.

So, the development of a decision can be carried out individually, collectively or en masse. We have a range from democracy to autocracy and dictatorship. The decision can also be made individually, collectively and en masse.

Finally, execution of a decision can be carried out on a voluntary basis, based on incentives or motivation, or on the basis of coercion, and coercion up to the threat of violence and repression. And it is in these spectral overflows and ranges that these terms find their cells of meaningful life.

So, what is similar between dictatorship and autocracy? This is a monopoly of power at the stages of decision making - sole, monopoly, and decision making - sole, monopoly. Both autocracy and democracy are no different in this. The difference is at the third stage - at the stage of execution of the decision.

Even if I decided for myself that I am the state, I am the president, and took over manual control, I still cannot carry it out alone. And here the difference between dictatorship, which makes this semantic position unique, is extremely pronounced violence - violence with the threat of massive potential repression, an atmosphere of fear, suppression of alternative thought, alternative ideas, and so on.

And on this logical search path we can now give a semantic definition formula. So, dictatorship is a type of imperious rule, management that has the form of monopolization of power in the hands of one (he is the dictator) or several people (dictatorial junta), and the institution of violence and repression dominating the executive mechanism.

I must say that I always want to confuse this concept, like the concept of autocracy, with the concept of totalitarianism. But there is no need to be confused. The diagram of semantic cells that I proposed allows us to understand the completely different field of life of these terms.

Totalitarianism characterizes the degree of statism, that is, the entry of the state into all spheres of life, issues and affairs of society and people. This can happen under democracy, under totalitarianism, under autocracy, and so on. It’s just another dimension of the quality of life of society and government in their symbiosis.

Can dictatorship be expedient? Is it an absolutely reprehensible category? Again I return to the emotional accompaniment of the search for the meaning of this category. Yes, maybe in conditions of force majeure, in military conditions, in special regimes, in mobilization circumstances.

And it's clear why. Because there is a question of life and death. The question of delay, the question of parliamentary debate about whether to retreat or advance on this front - it is clear that these are incompatible things. But force majeure, wars, shocks, mobilizations are an exception to normal, peaceful human life. And in normal, peaceful human life, dictatorship is not the most effective type of management and government, just like autocracy.

Monopolization of power is an inevitable path to decay. And no matter how tough the principle of governance may be, say, in the Soviet Union, where the mechanism of ideological violence and the monopoly of power of the CPSU led to the decay of the country, to its historical failure, in the same way the dictatorship cuts off a large amount of human intelligence and initiative in the symbiosis of society and power , creativity, dignity, alternatives, and this leads to inefficiency.

Fear, constraint and injustice also deprive the human community of creativity and efficiency, so in certain circumstances this, unfortunately, is inevitable with its costs, but there the circumstances themselves provide 100 times greater costs. For example, war - loss of life, destruction, injustice, crime. In peaceful life, of course, there must be other methods that provide the highest management efficiency.

Thank you. Next time we will deal with the term “crisis”. All the best.

(lat. dictatura) - a form of government in which all state power belongs to one person - a dictator, a group of people or one social stratum (“dictatorship of the proletariat”).

Currently, dictatorship, as a rule, refers to the regime of power of one person or group of persons, not limited by the norms of legislation, not restrained by any social or political institutions. Despite the fact that certain democratic institutions are often preserved under dictatorships, their real influence on politics is reduced to a minimum. As a rule, the functioning of a dictatorial regime is accompanied by repressive measures against political opponents and severe restrictions on the rights and freedoms of citizens.

Dictatorship in Ancient Rome

Initially, dictatorship was the name given to the highest extraordinary magistracy in the Roman Republic. The dictatorship was established by a resolution of the Senate, according to which the highest ordinary magistrates of the republic - the consuls - appointed a dictator to whom they transferred full power. In turn, the dictator appointed his deputy - the chief of the cavalry. Dictators were supposed to be accompanied by 24 lictors with fasces - symbols of power, while consuls were supposed to have 12 lictors.

Dictators had virtually unlimited power and could not be brought to trial for their actions, but they were required to resign their powers upon expiration of their term. Initially, the dictatorship was established for a period of 6 months, or for the duration of the execution of orders from the Senate, usually related to eliminating a threat to the state.

However, in 82 BC. e. The first permanent dictator, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, was elected (formally - “to carry out laws and to put the republic in order” (legibus faciendis et rei publicae constituendae causa)). In 79, Sulla, however, resigned as dictator. In 44, a month before his death at the hands of the conspirators, Gaius Julius Caesar, who had previously been elected dictator several times during the civil war according to the usual scheme, became permanent dictator. The office of dictator was abolished in 44 BC. e., shortly after the assassination of Caesar.

Sulla and Caesar were the last dictators in formal office and the first dictators of Rome in the modern sense of the word. Octavian Augustus and subsequent emperors were not appointed to the position of dictator (although this position was offered to Augustus), but actually had dictatorial power. Formally, the Roman state was considered a republic for a long time and all republican authorities existed.

Already Augustus ensured that his adopted son, Tiberius, became his successor. Subsequently, similar cases occurred more and more often. This became one of the prerequisites for the subsequent transformation of Ancient Rome into a monarchy.

Dictatorship in ancient Greek states

Dictatorship was a common occurrence in Ancient Greece and its colonies. Dictators in these states were called "tyrants" and dictatorship - "tyranny". At first, this word did not carry a negative connotation. Most tyrants relied on the demos and oppressed the aristocracy. Some of the tyrants, especially the early ones, became famous as philanthropists, just rulers and sages: for example, the tyrant of Corinth Periander or the tyrant of Athens Peisistratus. But much more stories have been preserved about the cruelty, suspicion and tyranny of tyrants who invented sophisticated torture (the tyrant Akraganta Phalarids, who burned people in a copper bull, was especially famous). There was a popular joke (his hero was at first Thrasybulus of Miletus, then he became attached to other people) about a tyrant who, when asked by a fellow tyrant (option: son) about the best way to stay in power, began to walk around the field and silently pluck all the ears of corn that stood out. above the general level, thereby showing that the tyrant should destroy everything in any way outstanding in the civil collective. Although at the stage of formation of the Greek polis tyranny could play a positive role, putting an end to aristocratic tyranny, in the end they quickly became a hindrance to the strengthened civil collective.

Some tyrants sought to turn their states into hereditary monarchies. But none of the tyrants created any lasting dynasties. In this sense, the oracle allegedly received by Cypselus, who seized power in Corinth, is indicative: “Happy is Cypselus and his children, but not the children of his children.” Indeed, Cypselus himself and his son Periander ruled safely, but Periander’s successor (nephew) was quickly killed, after which all the property of the tyrants was confiscated, their houses razed and their bones thrown out of their graves.

Epoch VII-VI centuries. known as the era of "elder tyranny"; by the end of it, the tyrants disappear in mainland Greece (in Ionia they remained due to Persian support, in Sicily and Magna Graecia - due to the specific military situation). In the era of developed democracy, in the 5th century. BC e., the attitude towards tyranny was clearly negative, and it was then that this term approached its current meaning. Tyranny itself was perceived by mature civil consciousness as a challenge to justice and the basis of the existence of the civil collective - universal equality before the law. It was said about Diogenes, for example, that when asked which animals are the most dangerous, he answered: “among the domestic ones - the flatterer, from the wild ones - the tyrant”; to the question which copper is the best: “the one from which the statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton are made” (the tyrannicides).

In the 4th century. BC e., in conditions of an acute crisis of the polis, tyrants (the so-called “minor tyranny”) reappear in the Greek city-states - as a rule, from successful military leaders and commanders of mercenary detachments; but this time there are no stories about wise and just tyrants at all: the tyrants were surrounded by universal hatred and themselves, in turn, lived in an atmosphere of constant fear.

When writing this article, material was used from the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron (1890-1907).

Dictatorship in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, the dominant form of government was the monarchy. Even as a result of coups, as a rule, representatives of royal or other noble families came to power, and they did not hide their intentions to pass on their power by inheritance. However, there were exceptions. Many city-communes and trading republics hired commanders - condottieri or princes - for defense. During the war, condottieri received great power in the city. After the war, relying on mercenary troops recruited with city money, some condottieri retained power, turning into dictators. Such a dictatorship was called a signoria. Some seignories became hereditary, turning into monarchies. One of the most famous dictators who founded the monarchy was Francesco Sforza.

Dictatorship in modern times

Right-wing dictatorships

In Europe

In modern times, dictatorial regimes became widespread in Europe in the 20s - 40s of the 20th century. Often, their establishment was a consequence of the spread of totalitarian ideologies. In particular, in 1922 a fascist dictatorship was established in Italy, and in 1933 a Nazi dictatorship was established in Germany. Far-right dictatorships were established in a number of other European countries. Most of these dictatorial regimes ceased to exist as a result of World War II.

Opinions are expressed that in the Russian Federation and the Republic of Belarus one of the forms of dictatorship is currently taking place

In Asia, Africa, Latin America

In Asia, Africa and Latin America, the establishment of dictatorships was accompanied by the process of decolonization. The seizure of state power by people from military backgrounds was widely practiced in these regions, leading to the establishment of military dictatorships.

Leftist dictatorships

In Marxism there is also the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Hidden forms of dictatorship

The Patriot Act adopted in the United States actually gave rise to the development of a new form of dictatorship. The Patriot Act grants overly broad powers to government law enforcement and intelligence agencies at their discretion, and that such powers can be used against citizens unrelated to terrorism simply to exert greater control over society at the expense of constitutional rights and freedoms. US citizens. This document allows you to create by-laws and instructions for public and private organizations, allowing the use of various methods of obtaining information, including the use of torture.

Advantages and disadvantages

Supporters of dictatorship usually point out the following advantages of dictatorship as a form of government:

Dictatorship ensures unity and, as a consequence, the strength of the system of power;

The dictator, by virtue of his position, is above any political party (including his own) and is therefore an unbiased political figure;

Under a dictatorship, there is more opportunity to carry out any long-term (not limited by the term of election) transformations in the life of the state;

Under a dictatorship, there is more opportunity to implement fundamental changes that are necessary in the long term, but unpopular in the short term;

A dictator, much more than an elected leader of a state, is aware of his responsibility for the state he rules.

Compared to a monarchy, the following advantages are distinguished:

A person with organizational and other abilities, will and knowledge usually comes to dictatorial power. At the same time, under a monarchy, power is replaced not by the candidate’s abilities, but by accident of birth, as a result of which the supreme state power can be received by a person who is completely unprepared to perform such duties;

A dictator is usually better informed than a monarch about real life, about the problems and aspirations of the people.

Among the disadvantages of dictatorship, the following are usually mentioned:

Dictators are usually less confident in the strength of their power, so they are often prone to massive political repression;

Following the death of a dictator, there may be a risk of political upheaval;

There is a great possibility of people for whom power is an end in itself getting into power.

Compared to the republic, the following disadvantages are also distinguished:

Under a dictatorship there is more theoretical possibility for the emergence of a monarchy;

The dictator is not legally responsible to anyone for his rule, which can lead to decisions being made that are not objectively in line with the interests of the state;

Under a dictatorship, pluralism of opinions is completely absent or weakened;

There is no legal opportunity to change a dictator if his policies turn out to be contrary to the interests of the people.

Compared to the monarchy, the following disadvantages are also distinguished:

Dictatorship is not usually considered a “godly” form of government.

Unlike a dictator, a monarch, as a rule, is raised from childhood with the expectation that in the future he will become the supreme ruler of the state. This allows him to harmoniously develop the qualities necessary for such a position.

4.2.3. Fundamentals of the constitutional system of China (PRC)

In the People's Republic of China, proclaimed on October 1, 1949, the constitution was adopted 4 times - in 1954, 1915, 1978 and 1982. Before the adoption of the first constitution, from the first day of the existence of the PRC, a provisional constitution was in force, which was officially called " General Program of the CPPCC" (CPPCC - Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference - the highest body of the Chinese revolution, which took over the functions of parliament).

The general program laid the foundations on which the young People's Republic of China began to be created:

democratic dictatorship of the people;

people's democratic (and then socialist) system; rights and freedoms, as well as human responsibilities;

a multi-party system with the leading role of the Communist Party;

public national economy;

auxiliary role in the economy of the national bourgeoisie;

unitary state, prohibition to create entities within China that have state status;

the right of small nations to autonomy;

organization of power according to the Soviet type - through a system of assemblies of people's representatives at all levels.

During the years of the “cultural revolution” (1966–1976), a campaign of brutal terror against dissidents, the constitutional order was virtually eliminated and the governance of the country at all levels was largely based on the arbitrariness of the authorities and the “crowd.” A year before Mao Zedong's death, the 1975 Constitution was adopted, which consolidated the results of the Cultural Revolution.

After the death of Mao in 1976 and the start of reforms, a new Constitution of 1978 was adopted, which had a compromise, opportunistic character.

As reforms led by Deng Xiaoping progressed in the country, on December 4, 1982, the NPC again adopted a constitution - the constitution of “modernized socialism” , which is still in effect today.

The Constitution of the People's Republic of China of 1982 is a relatively small document in volume. It includes 138 articles distributed in 4 chapters (1). “General provisions”, 2). “Fundamental rights and duties of citizens”, 3). “State structure”, 4). "State flag. National emblem. Capital").

The most important feature of the Chinese constitution is that both in form and content it is a typical socialist constitution. The main approaches to regulating social relations, their hierarchy are approximately the same as in other socialist constitutions, both past and present.

The Constitution of the People's Republic of China is overloaded with norms-principles, norms-declarations, norms-slogans and norms-programs. Sometimes it is difficult to draw a clear line between these norms and classical legal norms.

As an example, we can cite the following norms: “Who does not work, does not eat”, “All government bodies and civil servants maintain close ties (?) with the people...”. These norms do not contain clear rules of behavior and cannot be defended in court. One can only guess about their content.

The introduction to the Constitution deserves special attention. In this case, China followed the tradition of Asian socialist countries (Vietnam, North Korea) to replace the preamble with an introduction. If the preamble is a short, solemn part of the Constitution that justifies its adoption and declares the basic principles, then the introduction is a short story (1-2 book pages long) about the historical path traversed by the country and people.

Introductions to the Constitutions of Asian socialist countries usually talk about the difficult colonial past, the emergence of a wise hero leader who created the Communist Party and led the struggle for liberation, about the heroic struggle itself, about the victory of the revolution, about the everyday work of the people, and about future goals. The Introduction to the Constitution of the People's Republic of China describes:

the difficult historical past of the Chinese people, their heroic struggle for liberation;

perpetuates the role of the personality of Mao Zedong in this struggle;

praises the Communist Party;

sets goals for the future.

Chapter 1 of the Constitution sets out general provisions. This area of fundamental social relations in Western constitutions is often called the foundations of the constitutional system. However, Chinese legislators, following the socialist legal tradition, focused on regulating the basis of the socio-political system, rather than the constitutional system. We can highlight the following basic provisions characterizing the socio-political and economic system:

China (PRC) is a socialist state of the democratic dictatorship of the people, led by the working class and based on an alliance of workers and peasants;

the basic system of the PRC is the socialist system;

any organizations or individuals are prohibited from undermining the socialist system;

all power in the PRC belongs to the people (in reality, to the Communist Party);

the leading and guiding force of Chinese society is the Communist Party of China;

the Communist Party, having concentrated the will of the Chinese people, develops its position and political guidelines, which then, based on the decisions of the NPC (parliament), become laws and decisions of the state;

China is building an economy where there is no exploitation of man by man and the principle “From each according to his ability, to each according to his work” prevails;

the main type of property is socialist property;

the state allows the private sector in the economy, but on condition that it serves public interests (for example, produces necessary goods, gives people jobs, etc.) and plays an additional, auxiliary role in relation to the main state (socialist) sector of the economy ;

the state provides support to foreign investors;

the state conducts a planned economy on the basis of socialist property;

With the help of comprehensively balanced economic plans and the supporting role of market regulation, the state guarantees proportionate, harmonious development of the national economy.

following the socialist constitutional and legal tradition, Chinese legislators place the main emphasis on the rights of the citizen, and not the person in general;

based on this premise, it can be assumed that the rights enshrined in the constitution do not apply to foreigners (since they are not citizens of China);

in the constitution, despite the abundance of other rights, there is no provision for the right to life - the main human right;

in China, the death penalty is often used: for example, for many crimes from political to minor criminal, economic, the death penalty is punishable, which is often handed down by Chinese courts;

there is no norm on freedom of thought;

The constitution obliges spouses to implement birth planning (one family - one child). Violation of this rule entails a fine of 3 thousand yuan and certain troubles in later life. On the one hand, the state seeks to limit the growth of more than a billion population, on the other hand, this is a significant restriction of the most important natural human right - the right to have offspring, and thirdly, in this regard, abortions are performed too often in China. As a result of which millions of unborn babies die, and in modern constitutional law, especially in Western countries, there has been a tendency to protect the right to life of not only born, but also unborn people;

the constitution of the UPR not only provides the typical formulation for socialist constitutions of “the rights and responsibilities of a citizen” (and not “human rights and freedoms”), but also contains an overly large list of responsibilities;

The constitutional norm prohibiting in any way subjecting citizens to insults, slander, false accusations and persecution is specifically Chinese; this norm finds even more detailed development in the Criminal Code (Article 138); these norms were brought to life by the negative experience of the past, when during the “cultural revolution” of 1966–1976. Thousands of party and economic workers and other citizens were subjected to systematic persecution and insults, often of a public nature. By constitutionally banning bullying, legislators sought to end the practice and prevent similar occurrences in the future.

The regulation of the legal status of an individual in the 1982 Constitution is the best option for constitutional regulation of this problem compared to the theory and practice of previous years.

China is a unitary state with administrative autonomy. The administrative-territorial structure of the country includes 3 levels: upper (provinces, autonomous regions, cities of central subordination), middle (counties, autonomous counties, autonomous districts and cities) and lower (volosts, national volosts, towns, urban areas).

The national question is relevant for China. Of the more than one billion population, Han Chinese make up just over 90%. At the same time, non-Han peoples make up about 9%, but this is over 90 million people. Moreover, non-Han people occupy about half of China’s territory – sparsely populated areas of the North and West.

In order to resolve the national issue, China has created autonomies at all three levels: autonomous region (Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang Uygur, Tibet, Ningxia Hui, Guangxi Zhuang, Hong Kong (Hong Kong), autonomous region and autonomous county (30) and national parish (124) The highest officials of autonomous regions, autonomous counties, national volosts should be representatives of the nationalities that formed the autonomy, and, as a rule, other leaders of the autonomies should belong to the same nationalities.

There is no principle of separation of powers (in its “pure” form, as Europeans understand it) in Chinese constitutional doctrine. On the contrary, all power should belong to the organ of representation of the people - the People's Congress (PRC), the Chinese version of the Council. Based on this, there is a single subordinate “pyramid” of people’s assemblies, with lower-level People’s Congresses forming higher-level ones. Elections in the PRC are multi-stage (3 stages) and indirect:

the people directly elect deputies of local People's Congresses;

local people's congresses elect deputies to provincial people's congresses, people's congresses of autonomous regions and cities under central subordination;

Provincial People's Congresses elect deputies to the National People's Congress (NPC).

is the largest “parliament” in the world - includes 2 thousand native representatives;

elected through indirect, 3-stage elections;

some deputies are elected from the armed forces as a result of multi-stage elections within the army;

NPC deputies have an imperative mandate, that is, they are bound by the will of those who elected them and can be recalled early;

deputies work on a non-professional basis - they combine deputy activity with their main job;

The NPC meets for a session once a year, the session lasts 2-3 weeks - a very long time for the parliament of socialist countries;

in addition to legislative ones, has control functions;

The NPC has a two-tier structure - it forms a Standing Committee (“small parliament”) from its members;

the standing committee works all year round between sessions of the NPC (that is, the current activities are carried out by the “small parliament” - the standing committee, and once a year the “big parliament” - the NPC meets for a session);

adopts the Constitution of the People's Republic of China and makes amendments to it;

exercises control over the implementation of the constitution;

adopts and amends criminal and civil laws, laws on government structure and other basic laws;

elects the Chairman of the People's Republic of China (head of state) and deputy. Chairman of the People's Republic of China;

on the proposal of the Chairman of the People's Republic of China, approves the candidacy of the Prime Minister of the State Council (SC);

upon the proposal of the Prime Minister, the State Council approves the candidacies of his deputies, ministers, members of the State Council, chairmen of committees, the chief auditor and the head of the secretariat;

elects the chairman of the Central Military Council, and, on the proposal of the chairman of the Central Military Council, approves the candidacies of other members of the Central Military Council;

elects the Chairman of the Supreme People's Court;

elects the Prosecutor General of the Supreme People's Procuratorate;

reviews and approves plans for economic and social development, reports on their implementation;

reviews and approves the state budget and the report on its execution;

amends or repeals improper decisions of the NPC Standing Committee;

approves the formation of provinces, autonomous regions and cities under central control;

approves the formation of special administrative regions and their regime;

resolves issues of war and peace;

exercises other powers that should be exercised by the supreme body of state power.

interprets the constitution and oversees its implementation;

adopts and changes laws, except those that must be adopted by the NPC;

changes laws adopted by the NPC if these changes do not affect the fundamental provisions of these laws;

provides interpretation of laws;

between sessions, the NPC may make amendments to economic development plans and the budget;

repeals acts of the State Council that contradict the constitution and laws;

exercises control over the work of the State Council, the Central Military Council, the Supreme People's Court (!) and the Supreme People's Prosecutor's Office (!);

repeals acts of provincial and local government authorities that are contrary to the constitution and laws;

during the period between sessions of the NPC, upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister of the State Council, removes and appoints ministers;

carries out the appointment of senior officials other than those elected and appointed by the NPC;

appoints and recalls diplomatic representatives of the PRC in foreign countries;

establishes military ranks, diplomatic ranks and special ranks, and also makes decisions on their assignment;

declares a state of emergency;

resolves issues of war and peace in the period between sessions of the NPC.

The Constitution provides for the institution of a sole head of state - the Chairman of the People's Republic of China, who is elected by the National People's Congress for 5 years and is responsible to it. The Chairman of the PRC (and his deputy) can be a citizen of the PRC who has reached 45 years of age. Traditionally, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) or one of its senior leaders is elected as the Chairman of the People's Republic of China.

The highest administrative and executive body of China is the government - the State Council (SC).

The structure of the courts of the PRC, headed by the Supreme People's Court and the Supreme People's Procuratorate, corresponds to the administrative-territorial division of the country. The specificity of the judicial system and the prosecutor's office of the PRC is that they are law enforcement agencies of a socialist state, must be “close to the people”, in addition to resolving “contradictions within the people”, must fight “enemies”, have a punitive bias, are not independent (are under control of the relevant People's Congresses and their standing committees, as well as party bodies).

The term of office of the NPC is 5 years. The term of office of the Standing Committee of the NPC, other bodies and officials elected by the NPC is 5 years.

The most important feature of the 1982 Constitution of the People's Republic of China is the provision limiting the time senior officials can serve in their posts to two terms. Only two 5-year terms may be served in office:

Chairman of the People's Republic of China;

Premier HS;

Prosecutor General of the Supreme People's Procuratorate;

Chairman of the Supreme People's Court;

other officials elected by the NPC.

The peculiarity of the highest bodies of state power is that they do not have independent significance. All of them are “transmission belts” of the power of the Communist Party, which actually exists and is enshrined in the constitution. Despite this, China has a multi-party system, where in addition to the CPC there are 8 more parties: the Revolutionary Committee of the Kuomintang of China, the Democratic League of China, the Association for the Promotion of Democracy in China, the Workers' and Peasants' Democratic Party of China, the Party for the Pursuit of Justice, and the September 3rd Society. , Taiwan Democratic Autonomy League, All China Industrialists and Traders Association. However, in reality, the multi-party system is fictitious, since:

all parties must be loyal to the existing system and friendly to the CCP;

attempts to create a truly opposition party were brutally suppressed politically and criminally;

the parties are very small in number - several thousand people each, while the CPC has 40 million people;

parties have weak organizational structures and no real influence;

the entire political and government regime promotes one-party rule.

4.2.4. Fundamentals of constitutional law of Mongolia

The uniqueness of Mongolia’s development is that Mongolia made a “leap” from a feudal society to a socialist one, bypassing the stage of capitalism, and then an equally rapid “leap” from socialism to capitalism.

Until 1921, Mongolia was a semi-colonial feudal state led by the Bogdo-Gegen, an absolute ruler who combined political and theocratic power. In 1921, a people's democratic revolution took place in the country, as a result of which a limited monarchy was established: the power of Bogdo-Gegen and the aristocracy was greatly reduced, and a people's government was created.

In 1924, the monarchy was finally abolished and the first Constitution of Mongolia of 1924 was adopted, which enshrined the republican form of government, proclaimed that all power belonged to the arats, that is, the peasants (there was no working class at that time), and established the highest body of popular representation - the Great People's khural, as well as other bodies of people's power.

After this, two more Constitutions were adopted in Mongolia - in 1940 and 1960. The Constitution of 1940 secured the final victory of the people's democratic system and proclaimed a course towards building socialism. 20 years later, the Constitution of 1960 recorded the victory in the country of socialism and legitimized the leading role of the MPRP, the Communist Party.

Socialism in Mongolia lasted exactly 30 years (1960–1990). In 1990, mass anti-socialist protests emerged in the country, which marked the beginning of bourgeois-democratic reforms.

Unlike the Asian socialist countries (China, Vietnam, North Korea), which either retained the socialist system or are trying to adapt it to modern conditions, Mongolia became the only Asian country that decisively abandoned the socialist system and began building a bourgeois-democratic capitalist society.

On January 13, 1992, the fourth and current constitution of Mongolia was adopted, which consolidated the rejection of socialism and the first results of bourgeois-democratic reforms. Mongolia's 1992 Constitution is one of the shortest in the world. It contains only 70 articles, is extremely specific, almost devoid of socialist features and is completely de-ideologized. The following main provisions and features of the 1992 Constitution of Mongolia can be highlighted.

The Constitution of Mongolia regulates in detail fundamental human rights and freedoms. It secures such fundamental rights as:

the right to life (not included in the constitutions of the modernizing China and Vietnam), including the right to life in an environmentally friendly, safe external environment;

the right to freedom of opinion, freedom of speech, press;

the right to travel abroad and return home;

the right to freedom of conscience; right to petition;

the right to medical care and social assistance in old age.

The highest government bodies of Mongolia are the parliament - the State Great Khural, the president, the government, and the Supreme Court.

^ Great State Khural (Parliament of Mongolia), consisting of 76 deputies, is directly elected by the citizens of Mongolia for a 4-year term.

The State Great Khural occupies a central place among the government bodies of Mongolia. He has broad powers, the main of which are the adoption of laws, the formation of other government bodies and monitoring their activities.

The president Mongolia exercises the functions of the head of state. He is elected through popular elections using a 2-round absolute majority system. The president, together with parliament, forms the government.

Despite being elected by all the people, the president is accountable in his activities to parliament. He can be removed from office by the State Great Khural by a simple majority vote of those present (!). The government and other state bodies are also responsible to the State Great Khural, the highest body of state power.

In Mongolia, unlike many Asian countries, there is a supreme special body of constitutional justice - ^ Court of constitutional review. The Court of Constitutional Review consists of 9 judges who have reached 40 years of age and have high legal and political qualifications. They are elected by the State Great Khural for a 6-year term: 3 judges are nominated by the Khural itself, 3 by the President, 3 by the Supreme Court with the right to be re-elected for another term.

The Constitution of Mongolia can be changed by the State Great Khural with a 3/4 majority vote. If any amendment is rejected, it can only be re-adopted by the next State Great Khural.

4.2.5. Fundamentals of Japanese Constitutional Law

The constitutional development of Japan began in 1889, when the first Japanese constitution was adopted. This constitution consolidated the results of the victorious bourgeois-democratic revolution (Meiji revolution). Despite its conservatism and archaism (consolidation of class differences and privileges, great powers of the emperor, the presence of a special hereditary chamber in parliament for the aristocracy - the chamber of peers), the Constitution of 1889 gave a powerful impetus to the economic and political development of the country.

After Japan's defeat in World War II and its occupation by American troops, the development of a new constitution began. An important feature of the new constitution was that it was developed with the active participation and pressure of the Far Eastern Commission, an occupation body that had the power to radically reform the Japanese constitution.

The leading role in the activities of the Far Eastern Commission was played by US scientists and generals. In fact, the post-war constitution of Japan was written for this country by the United States and its allies.

The new Japanese constitution was finally adopted by the Diet in October 1946 and came into force on March 3, 1947. This constitution is in force to this day, and due to its “rigidity” it has remained unchanged. The following features of the current constitution of 1947 (and its differences from the previous Constitution of 1889) can be highlighted:

the principle of popular sovereignty is enshrined (power comes from the people, not from the emperor);

the constitutional monarchy headed by the emperor has been preserved, but the powers of the emperor are significantly limited;

Parliament has been declared the supreme body of state power;

the hereditary chamber of peers of parliament was abolished;

a bicameral structure of parliament is provided, consisting of two elected chambers - the House of Representatives and the House of Councilors;

parliament is given the right to form a government;

the government became responsible to parliament rather than to the emperor;

estates were abolished (peers, princes, etc.); fundamental human rights and freedoms are secured;

the principle-obligation of Japan's renunciation of war and armed forces is constitutionally enshrined (Article 9: “The Japanese people forever renounce war as the sovereign right of the nation, as well as the threat or use of armed force as a means of resolving international disputes”);

Based on this constitutional provision (adopted under direct pressure from the United States), Japan still does not officially have its own army (except for a few self-defense forces).

Emperor of Japan:

is a purely ceremonial figure (the representation of Japan within the country and abroad, and the very activities and behavior, the clothes of the emperor are strictly regulated and surrounded by complex and mysterious ceremonies, rooted in the Middle Ages);

does not have independent powers to govern the state (all the actions of the emperor are in the nature of “sanctification”, giving additional force to the decisions of other state bodies);

The emperor, in particular, promulgates laws and government decrees, convenes parliament, issues an act of dissolution of parliament, confirms the appointment of ministers based on the relevant decision, and accepts credentials from foreign ambassadors.

Organizational support for the activities of the emperor is carried out by a special body - the Council of the Imperial House.

The highest body of government in Japan and the only legislative body of the state is the parliament, consisting of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the House of Councilors.

The House of Representatives (lower house) consists of 500 deputies who are elected for 4 years using a single non-transferable vote system. (The whole country is divided into 129 multi-member districts, in each of which the fight is for 3-5 mandates. A voter in multi-member districts votes for only one candidate, and candidates who take 1st to 3rd (4, 5th) places in the district become deputies Thus, the will of almost all voters is represented in parliament).

The House of Councilors (upper house) consists of 252 deputies (councillors):

152 councilors are elected in multi-member constituencies coinciding with prefectural boundaries, using a single non-transferable vote system;

100 councilors are elected by proportional representation (party lists) nationwide;

the term of office of the House of Councilors is 6 years;

Half of the councilors are re-elected every three years.

citizens who have reached 20 years of age have the right to vote;

the right to be elected to the House of Representatives begins at the age of 25, and to the House of Councilors at the age of 30;

Candidates must pay an election deposit of 3 million yen (House of Representatives) and 2 million yen (House of Councillors). The deposit is not returned if the candidate does not receive the number of votes obtained by dividing the number of voters in the district by the number of mandates;

the election campaign lasts 2 weeks;

During the election campaign, it is prohibited to campaign against other candidates, go door to door and use television for more than 3 minutes;

the most common form of campaigning is speaking in the district and meeting with voters;

as a rule, the election campaign itself (especially for a new candidate) is not beneficial, since in practice elections in Japan are a competition between already established reputations;

Nepotism and clanism are widespread: about a quarter of deputies are children, wives and other relatives of former deputies.

The Lower House of Representatives, on the contrary, can be dissolved early by the emperor by decision of the government (which often happens in practice). Therefore, elections to the House of Representatives occur much more often than once every 4 years (in reality - once every 2 years).

The highest executive body of Japan is the government - the Cabinet of Ministers. It includes: the Prime Minister, 12 ministers, 8 ministers of state (deputy prime ministers and ministers without portfolio).

The government of Japan is formed by and is responsible to parliament.

The Prime Minister of Japan is a key figure in the Cabinet of Ministers. He is actually the current leader of the country. The formation of the Cabinet of Ministers begins with the election of the Prime Minister by parliament from among its members. Until parliament (especially the newly elected one) has elected a prime minister, it cannot decide other issues.

The following features of the formation and functioning of the Cabinet of Ministers of Japan can be highlighted:

According to tradition, the leader of the party that wins the election is elected prime minister.

Half of the ministers must be members of parliament (like the prime minister himself).

Appointment to a ministerial post does not entail the loss of a deputy mandate; in practice, almost all members of the government are deputies, and they continue to simultaneously perform deputy functions and do not lose contact with voters.

The Cabinet of Ministers, as a rule, meets in secret.

Decisions are made only by consensus - unanimously.

Only the entire government as a whole is responsible for the work; a vote of no confidence in the prime minister entails the resignation of the entire government.

When parliament passes a vote of no confidence, the government either resigns entirely or remains in power and the prime minister dissolves the lower house of parliament within 10 days; in practice, a government that receives a vote of no confidence often prefers to dissolve parliament rather than resign.

The Cabinet of Ministers of Japan is a short-lived entity; at best, it remains in power for no more than 2 years.

According to Japanese traditions and mentality, firstly, some people cannot be more important and more authoritative than others, and secondly, one cannot hold government positions for too long and parties must constantly nominate new people, which is why prime ministers and ministers must constantly change : ministers - every year, prime ministers - every two years.

Ministers (primarily representatives of the parliament of the 9 ruling parties) in the ministries they head, and, as a rule, are not specialists in their respective fields.

This determines the special structure of Japanese ministries: at the head of each ministry is the minister himself and his two deputies - political and administrative; the political deputy, like the minister, is a representative of the party in the ministry, he resigns at the same time as the minister, and the administrative deputy minister is a professional official with a special education, as a rule, who has worked all his life in this field and for many years in the ministry; the administrative deputy minister has been professionally leading the ministry for years, and ministers and their political deputies come and go every year without having time to delve into the affairs of the ministry in detail.

For a long time, for 38 years (1955–1993), Japan had a multi-party system with a single dominant party, which was the Liberal Democratic Party. It was its representatives who became prime ministers for 38 years in a row, occupied most ministerial posts, and determined the country's domestic and foreign policy.

LDPJ is the party of big business, the highest bureaucracy, and entrepreneurs. Having been the only ruling party for a long time, the LDP, nevertheless, had many movements in its composition: the party had 6 factions that were constantly fighting for influence in the party.

In 1993, the LDP lost the elections and lost its monopoly on power. This is explained, firstly, by the fatigue of Japanese voters with the same ruling party, the decline in the authority of the LDP due to high-profile scandals exposing corruption in its highest echelons, constant splits in the party and the exit of small groups from its composition; secondly, other political parties and movements have grown and strengthened:

Social Democratic Party of Japan (established 1945), 1945–1991 bore the name Socialist Party, maintained close ties with the CPSU; after 1991, it “improved” significantly, which brought it to the number of leading parties in Japan;

the Komeito (pure politics) party - based on Buddhist ideas;

party of democratic socialism;

Communist Party (little influential both in the past and at present);

The Sakigake Party is a breakaway part of the LDP.

Japan is a unitary state, the administrative-territorial units of which are: Tokyo Metropolitan Area, Hokkaido Island, 43 prefectures.

In prefectures (regions), a local representative body and a governor are elected.

The Japanese judicial system consists of:

50 district courts;

8 higher courts;

Supreme Court;

family courts (including hearing cases of crimes committed by minors under 20 years of age);

disciplinary courts - consider minor civil and minor criminal cases.

consists of the chief judge and 14 judges appointed by the Cabinet of Ministers;

works either plenary (quorum – 9 people) or in sections (5 people each, quorum – 3);

is the highest court;

exercises constitutional control;

gives guiding explanations to lower courts and has a great influence on their work with its decisions.

Assignments for the section

Identify common and special features of the constitutions of the leading countries of Western Europe.

Identify common and special features of the constitutions of Asian countries.

Explain the reasons that contributed to the formation of the European Union.

Identify the specifics of parliamentarism in the countries of Asia and Western Europe.

Explain what is special about democracy in Asia and Western Europe.

What are the specifics of the system of separation of powers in the countries of Asia and Western Europe?

people? Yes it is very good. This is the highest manifestation of the people's struggle for freedom. This is that great time when the dreams of the best people of Russia about freedom are translated into action, the work of the masses themselves, and not of lone heroes.

ON THE HISTORY OF THE ISSUE OF DICTATORSHIP134

(THE NOTE)

The question of the dictatorship of the proletariat is the fundamental question of the modern labor movement in all capitalist countries without exception. To fully understand this issue, it is necessary to know its history. On an international scale, the history of the doctrine of revolutionary dictatorship in general and the dictatorship of the proletariat in particular coincides with the history of revolutionary socialism and especially with the history of Marxism. Then - and this, of course, is the most important thing - the history of all revolutions of the oppressed and exploited class against the exploiters is the most important material and source of our knowledge on the question of dictatorship. Anyone who does not understand the necessity of the dictatorship of any revolutionary class for its victory has understood nothing in the history of revolutions or does not want to know anything in this area.

On the Russian scale, of particular importance, if we talk about theory, is the program of the RSDLP135, compiled in 1902-1903 by the editors of Zarya and Iskra, or, rather, compiled by G. V. Plekhanov and edited, modified, approved by this editorial board. The question of the dictatorship of the proletariat is raised clearly and definitely in this program, and, moreover, it is raised precisely in connection with the struggle against Bernstein, against opportunism. But the most important thing, of course, is the experience of the revolution, that is, in Russia the experience of 1905.

The last three months of this year - October, November and December - were a period of remarkably strong, broad, mass revolutionary struggle, a period of combining the two most powerful methods of this struggle: a mass political strike and an armed uprising. (We note in parentheses that back in May 1905, the Bolshevik congress, the “Third Congress of the RSDLP,” recognized “the task of organizing the proletariat for the direct struggle against the autocracy through an armed uprising” as “one of the most important and urgent tasks of the party” and instructed all party organizations “to clarify the role of mass political strikes, which can be important at the beginning and during the very course of the uprising”136.)

For the first time in world history, such a height of development and such strength of the revolutionary struggle were reached that an armed uprising came out in conjunction with a mass strike, this specifically proletarian weapon. It is clear that this experience has global significance for all proletarian revolutions. And the Bolsheviks studied this experience with all attention and diligence, both from its political and economic sides. I will point out the analysis of monthly data on the economic and political strikes of 1905, on the forms of connection between both, and on the height of development of the strike struggle, which was then achieved for the first time in the world; This analysis was given by me in the journal “Prosveshchenie” in 1910 or 1911 and repeated, in brief summaries, in foreign Bolshevik literature of that era137.

Mass strikes and armed uprisings themselves put on the order of the day the question of revolutionary power and dictatorship, for these methods of struggle inevitably gave rise, first on a local scale, to the expulsion of the old authorities, the seizure of power by the proletariat and revolutionary classes, the expulsion of landowners, sometimes the seizure of factories, etc. etc. etc. The mass revolutionary struggle of this period gave rise to such organizations, unprecedented in world history, as the Soviets of Workers' Deputies, and after them the Soviets of Soldiers' Deputies, Peasant Committees