Former people's deputy of the RSFSR and investigator Yuri Luchinsky on how the "cotton business" affected perestroika

At the beginning of perestroika in 1986, at the XXVII Congress of the CPSU, the term “Rashidovshchina” (from the name of the former first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan Sharaf Rashidov) was first used, which became synonymous with bribery and corruption. Corruption in the republic was exposed at the congress not only by party leaders, but also by delegates from Uzbekistan. However, in two years, almost everyone who spoke diatribes will themselves be accused of taking bribes and arrested. This will cost the careers of the leaders of the investigation team Nikolai Ivanov and Telman Gdlyan. According to many historians, the investigation of corruption by Gdlyan and Ivanov, and the subsequent persecution of the investigators themselves, dealt a mortal blow to the CPSU. Lenta.ru talked about this case with an investigator from the Gdlyana-Ivanov group, a former people's deputy of the RSFSR, who was a member of the commission of the Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR on the Gdlyan-Ivanov case, Yuri Luchinsky.

"Lenta.ru": "Cotton business", or "Uzbek case", and a group of investigators Gdlyan and Ivanov, who dealt with it, became known throughout the country in the late eighties, when in the USSR, as part of perestroika, war was declared on registrations, theft of state property , bribes. You were a member of this group, tell us how it was formed, how many investigators were included in it?

Luchinsky: The case investigated by our group was never "cotton". This is a journalistic-philistine expression of those years. Our group investigated exclusively episodes of bribery in the leadership of Uzbekistan. Postscripts and other forms of cotton-related theft were dealt with by other investigative units.

The group was formed in 1983. The KGB authorities of Uzbekistan exposed the head of the Bukhara OBKhSS with a bribe - in the order of planned work for the “struggle” indicator. He testified against many of his leaders. The case was sent away from sin to Moscow. And the USSR Prosecutor's Office sent investigator Gdlyan to Bukhara to investigate. Further, the matter moved according to the principle of a snowball for six years - from the top leadership of the republic to significant figures in the leadership of the CPSU and the state.

Taking into account the rotation in the group, in total, about five hundred people worked, sent from different regions of the Union. At the same time, I believe, at least a hundred people worked. Subgroups were in each regional center of Uzbekistan, in Tashkent and Moscow. I was seconded there in early 1988. More investigators were needed, and there were no resources in the prosecutor's office. They began to take in a group of investigators of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. I was requested on the recommendation of friends who had already worked for Gdlyan.

In the case, Brezhnev's son-in-law Yuri Churbanov, high-ranking party officials of Uzbekistan, were among the defendants, did you know who the main goal of the investigation was? Or did you just unravel the tangle of corruption?

The only purpose of the investigation was bribes in the leadership of Uzbekistan. The word "corruption" appeared in the philistine circulation much later than the beginning of our work. During the investigation, the defendants testified about giving bribes to higher officials. The ones when they were attracted are even higher. So it came to the apparatus of the Central Committee of the CPSU.

Why do you think they decided to make such a serious blow to corruption in the Uzbek SSR? You studied the scale of corruption on the spot, was it really huge?

We came to Uzbekistan by chance and situationally. We, who lived in that country, knew perfectly well that everything can be bought and sold. In different republics there was only a different degree of admission of citizens to corrupt services.

It is believed that this was originally an intrigue by Yuri Andropov against the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan Sharaf Rashidov and the Minister of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs Nikolai Shchelokov, Brezhnev's favorites. And then it turned around?

I repeat, the case began spontaneously with the planting of the head of the Bukhara OBKhSS by the local KGB. They themselves did not expect the snowball effect and got rid of the case by floating it to Moscow. What was in Andropov's head, I don't know.

There is also an opinion that one of the main figures in this case was Brezhnev's son-in-law Churbanov, and the investigators were especially active in extracting evidence from those arrested against him. For example, the former chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Uzbek SSR Narmakhonmadi Khudaiberdiev spoke about this at the trial. What do you think of it? Was Churbanov discussed in your group, what was the opinion about him?

Churbanov in this case was one of the smallest fry. Unlucky guy with his wife and father-in-law. And he was automatically given bribes when traveling around Uzbekistan. He himself was zero without a wand.

In the USSR, in connection with crime in Uzbekistan, there were rumors about dogs with gold teeth among Uzbek bais, have you ever met such?

I don’t discuss philistine stories about the wealth of the bosses. I haven't heard of gold-toothed dogs. And the guys lived really well. But much more modest than ordinary bosses live now.

In the documentary “Gold for the Party. Cotton Business”, Deputy Prosecutor of the Uzbek SSR Oleg Gaydanov says that organized crime flourished in Uzbekistan, where free conditions were created for it, where, in his words, thieves in law from all over the USSR and other criminals rushed. But from open sources it is known about arrests only among party leaders and production workers in Uzbekistan. I did not find a single mention of thieves in law. Do you know anything about this?

I don't know what Gaidanov says there. In terms of general criminality, Uzbekistan was, like any relatively developed southern republic, where you can profit. And no more. The warm seas criminals, I believe, were fatter.

At the time of joining the group, were you interested in politics? What were your views?

Little interest in politics. He treated the Soviet system critically and even hostilely. But he served her, as it turns out, acceptable. For thoughts to serve something else did not appear. He was in the CPSU, like any person who wants to move in the slightest degree in the service. In the same way, for the sake of a higher salary than that of a factory legal adviser, he came to the police.

He ran for people's deputies of the RSFSR, identifying himself with the "Democratic platform in the CPSU". It was like that then. The remnants of illusions about communism and communists were dispelled at the very first Congress of People's Deputies of the RSFSR in 1990. He left the party officially, with the submission of an application to the district committee at the place of residence. With the announcement of this at a session of the Petrodvorets District Council of Leningrad during a report on the first stages of his deputy work - two weeks before a similar act by Yeltsin. Without a command from above and without waiting for August 91.

How did you perceive Gorbachev's perestroika?

At first I didn't notice at all. Then he sympathized a little, then realized that Gorbachev is a jester who loves himself in art, instead of art in himself. And trying to keep this “art” for himself.

How many people did your group arrest? In the press, the data differ, somewhere they write no more than a hundred, somewhere that the scope of arrests reached a thousand people. From Uzbekistan then they began to write to Moscow that Moscow investigators had arranged a new 37th year.

From conversations with the leaders of the group, it turned out that from sixty to eighty people were under arrest during the entire investigation. Approximately a quarter went to trial and were convicted. Approximately a third of those in custody at the investigation stage, with the sovereignty of Uzbekistan, were deported to Tashkent. Where they were immediately rehabilitated. The rest were released at the investigation stage due to the inappropriateness of detention.

If I worked then as a lawyer for one of these guys, I would also tell reporters about the 37th year. And the pre-trial detention center, even the most decent one, is not the most pleasant place. And interrogation by the investigator, if a person is afraid to say something, is no less painful procedure. Subjectively, this can be assessed as the "37th", and as the "Inquisition", and whatever else. And there will be some truth in this.

Have all the condemned been pardoned?

When leaving the plane, they were immediately rehabilitated and unescorted.

In Uzbekistan, some suspects committed suicide during the investigation, there is an opinion that because of the pressure of the investigators, what do you think?

I don’t know their last names, but some of those under investigation could have both mental disorders and suicides. I repeat once again. The usual routine work of an investigator to identify the circumstances of a crime is terrible for the person under investigation, because it breaks his life. The elementary tactic of any interrogation implies a psychological confrontation between the investigator and the interrogated. And this is by no means always comfortable for the latter. Both tricky questions and the investigator's elementary explanations of a development of events unpleasant for the client in the event that he evades truthful testimony are terrible for the latter. And they can lead to suicide, and to anything.

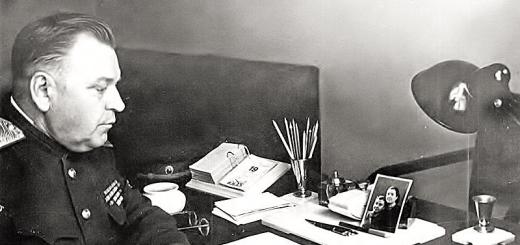

Photo: Vsevolod Tarasevich / RIA Novosti

At first, your group was supported in the Politburo, then the mood changed, and criticism began. Then the investigators hinted at a connection with the bribe-takers of Ligachev himself. He writes in his book that Gdlyan and Ivanov began to be used by his political opponents. What do you think of it?

Ligachev was too poor to participate in any corrupt systems. And he and others like him didn’t need it - they lived decently on state security. One of the Uzbeks testified that he had given Ligachev twenty thousand rubles as a gift to strengthen good relations. I do not remember the exact amount and circumstances of the transfer. Maybe somewhere in the country, or even put it on the bedside table ... It doesn’t matter. From the very beginning, this information was not perceived as an exposure of a high-ranking idiot. So, filthy dirt on the chatty boss. This was regarded as an episode of the life of a certain “don”. But Gdlyan and Ivanov betrayed this to the people when pressure began to cover up the investigation of the case. And Yegor Kuzmich, accustomed to his sterility, was terrified of this. hysterical. The backlash against the investigators intensified.

If not Ligachev, then who was behind the pressure on your group? And who, on the contrary, supported?

No one in the leadership of the Prosecutor's Office supported us as soon as the destruction began. These are too cowardly and opportunistic guys to urinate against the wind. For example, Viktor Ilyukhin, who died not so long ago. State communist. At that time he was in the leadership of the prosecutor's office. He climbed into the TV cameras together with Gdlyan and in every possible way welcomed our successes. After the turn of politics, he began to sharply stigmatize and expose us. Among the investigators themselves, the majority immediately withdrew, writing off their homes for family reasons. Many have made a career out of exposing Gdlyan and Ivanov. And only a few followed the leaders, practically going into politics.

You have already mentioned a possible bribe to Ligachev, about which the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Socialist Republic Inamzhon Usmankhodzhaev spoke about during interrogation (he was sentenced to 12 years in this case), he also mentioned Grishin, Romanov, Solomentsev, member of the Central Committee of the CPSU Kapitonov. Allegedly, they were also involved in bribes. Later, however, he wrote that he gave these testimony under duress. When do you think he spoke the truth? Maybe you know something about it?

I know little about the ins and outs of the upper echelon of clients, I don’t discuss all these squabbles.

Photo: Boris Kavashkin, Dmitry Sokolov / TASS

The Gdlyan-Ivanov group was supported by Yeltsin, do you think it was populism or did he sincerely oppose corruption then?

Not a group, but Yeltsin supported his colleagues in the corps of people's deputies of the USSR Gdlyan and Ivanov. Companions in the interregional deputy group. Not really, I think, delving into the essence of the matter. But knowing full well that the system where he went through everything just doesn’t stink. And a priori, he considered the investigators to be his allies.

In the end, the USSR Prosecutor General Alexander Sukharev accused your group of obtaining evidence by threats and falsification of cases. Many were expelled from the party, and the Supreme Council condemned the investigators' accusations against them. How did you react to it, what did you think?

In May 1989 there was an extended meeting of the Collegium of the USSR Prosecutor's Office on our case. Something like a formal big meeting in the assembly hall. A lot of investigators were present. During the rally part of the meeting, I was given the floor. From the podium, I called Sukharev “a beer salesman convicted of underfilling beer, accusing the accusers of speaking rudely to him,” something like this.

They were not expelled from the party. From the bodies in the fall of the same year, he was fired. I have already been nominated as a candidate for deputies of the RSFSR. And I was sent for three months on a business trip to the Komi ASSR. Refused. That's what they fired. When he was elected, he was quickly restored.

In addition to debriefing, there was a criminal case against your group. Were you interrogated in this case yourself?

They didn't interrogate. In the personnel inspectorate of the Central Internal Affairs Directorate of Leningrad (the current “own security”), they selected explanations about the signals from Moscow about my public appearances.

What is the essence of the charges in this criminal case? Did you really, as the newspapers wrote then, violate "socialist legality" during the investigation of the case? How did this case end for Gdlyan and Ivanov?

No charges were brought against anyone. For Gdlyan and Ivanov, the case ended in a complete cessation, both in relation to themselves and in relation to our clients.

Then you began to participate in the movement in defense of the investigation team? Tell me what the movement was.

There was no particularly structured movement. They were actively supported by organizations of voters in Moscow as a whole and in Zelenograd and Tushino (Gdlyan's constituency). And in Leningrad (the citywide national constituency of Ivanov). In this system, I spoke a lot at public events, traveled to enterprises with lectures, wrote articles and notes wherever possible. All this was organically connected with my work in the summer of 1989 as an expert at the commission of the Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR on the “Gdlyan-Ivanov case”. And later - with the beginning of my own election campaign. Ivanov himself was my confidant in the Petrodvorets District. Without their names and Gdlyan's support, I would hardly have won. So the support was mutual. Just common and collaborative work.

There is a photograph of a street action on the Internet, in which you, Yeltsin, Gdlyan are holding hands, what kind of action is this? In support of investigators?

In the photo with Yeltsin, the last October demonstration, November 7, 1990. First there was an official demonstration, Yeltsin, as chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation, defended with all the bosses on the podium. And then a large column of the democratic public passed. The chiefs left the podium, and Yeltsin, somewhere in the area of the National Hotel, joined the column, standing at its head.

Why did you, Gdlyan and Ivanov decide to go into politics, into deputies?

I don't know what was in their heads. In addition to indignation at what is happening, and the desire to win as investigators. Gdlyan was offered to run by the Moscow public. Including the then active electoral formations that "led" Yeltsin. Such offers are not rejected. It is very honorable, interesting and promising. And Ivanov at first was simply a member of the Gdlyanovskaya elective team. He spoke a lot, he has a good ability as an orator and lecturer. Better than Gdlyan's. And at the second stage of the elections, the Leningrad public nominated him as a candidate for a citywide five million constituency. And Nikolai defeated 35 opponents from the first run.

And how do you feel about Yeltsin?

The attitude towards Yeltsin is diametrically opposed to the attitude of the cattle, who believes that he is a drunkard who ruined the USSR and betrayed the ideals of communism, nurtured the thieves' "family" and covered his rear with Chekist Putin. To discuss all this I consider it indecent. Change the signs and get my attitude towards Boris Nikolayevich.

Besides you, did anyone else from the group of investigators go into politics?

Of course. I became people's deputies of the RSFSR, Yuri Eskov and I, a former investigator of the prosecutor's office of the city of Pushkino, Moscow Region. Nina Reiter, Anatoly Tkachenko, both prosecutors from Leningrad, got into the Leningrad Council of People's Deputies. To the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (then still, in my opinion, the Supreme Council) - Alexander Moroz from Nikolaev, investigator of the Nikolaev prosecutor's office. To the Khabarovsk Territory Council - Zinaida Starkova, investigator of the Prosecutor's Office of the Khabarovsk Territory. I don't know anymore.

Why were you called as a candidate for deputies?

I repeat, I was nominated by two organizations at my place of residence - the Petrodvortsovy district of Leningrad and the Youth Center and Bioinstitute of the Leningrad State University. They put forward as fellow countrymen. By this time, I was fairly well known in Moscow and Leningrad as an investigator of the group and a propagandist of our cause. They also wanted to put forward in one of the districts of Moscow, but did not have to. Work began in Leningrad.

What did you do as an MP?

I was first deputy chairman, then secretary of the Supreme Council Committee on the Media, Relations with Public Organizations and the Study of Public Opinion. Our subcommittee chairmen were, in particular, Lev Ponomarev and Sergei Yushenkov. And the chairman of the committee itself for a whole year was Vyacheslav Bragin, later the chairman of Ostankino.

You were a member of the Radical Democrats faction, why exactly?

Because I was and remain a radical opponent of the Soviet regime in Russia. And a supporter of more radical measures to eradicate it. That is why he was a member of the faction with that name, headed by Yushenkov, blessed memory to him!

How did the “cotton business” end for you and how do you assess its contribution to perestroika?

For me personally, it ended in disgust in my soul from the dirt with which we were mixed. And strengthened persistent rejection of the Soviet system. As well as his own breakthrough in politics, quite a big one.

In my opinion, the significance of this case was in illustrating for the population the real essence of communist power. Nothing beautiful in itself, as was said. But cheap and dirty. And the demolition of the Soviet system took place largely not without such a popular re-consciousness.

On the other hand, a huge mass of slaves, accustomed to salaries, bonuses, allowances, recruitment, enthusiastically accepted the investigators who repressed wealthy bosses. Just like Yeltsin, who broke with the world of these bosses. The masses expected that after the coup, they would distribute good things to her from the master's stash. And there was nothing to distribute. Yes, actually, and there is no need. As soon as the distribution broke off, the masses immediately forgot the investigators and hated the "drunkard Yeltsin."

In June 1989, the so-called "cotton case" came to an end - as they collectively called a series of criminal cases on economic and corruption abuses in the Uzbek SSR, which had been investigated since the late seventies. The investigations were carried out by a commission led by Moscow investigators Telman Gdlyan and Nikolai Ivanov. 800 criminal cases were initiated, in which more than four thousand people were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment, including high-ranking officials and party functionaries, heads of cotton-cleaning associations of Uzbekistan, and directors of cotton factories.

In 1989, during the days of the first Congress of People's Deputies, Gdlyan's investigation methods were seriously criticized - up to the institution of a criminal case against him for violating the law during investigations in Uzbekistan. In 1990, Gdlyan was dismissed from the Prosecutor General's Office, expelled from the ranks of the CPSU. However, in August 1991, the Gdlyan case was closed. In December of the same year, the President of Uzbekistan Islam Karimov pardoned all those convicted in the "Uzbek case" who were serving their sentences on the territory of the republic.

The events of those years are recalled by a Russian lawyer, candidate of legal sciences, professor, former Acting Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation, former Deputy Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation, State Counselor of Justice 2nd class Oleg Gaidanov. It was he, already well-known in the country, a 39-year-old lawyer, at the dawn of perestroika, who was sent to a particularly important area of work at that time - to Uzbekistan, to the post of head of the investigative department, deputy prosecutor of the republic. It was perhaps his longest business trip.

It was Gaydanov who was often blamed for the fact that thousands of people were arrested and convicted on cotton cases in Uzbekistan between 1984 and 1989.

Oleg Gaidanov

Oleg Ivanovich, at that time the current Uzbek leader was not at the top of power, but you should have known each other by position (Islam Karimov served as Minister of Finance, Chairman of the State Planning Committee and Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Uzbek SSR from 1983 to 1986. - Note "Fergana "). How did he appear to you then?

In 1989, when I was leaving Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov became First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Republic. But I had known him for several years before and had a great relationship with him. And I'll tell you why. The fact is that when I arrived in Uzbekistan in the fall of 1984, Karimov was the first official who appeared in my office and gave me a complete picture of what was then happening in the Uzbek SSR. I was the head of the Investigation Department and Deputy Prosecutor of the Republic, and he was the Minister of Finance. We talked with him for several hours. AT

Kazakhstan, where I came from, I was the deputy head of the Investigation Department of the Prosecutor's Office of the Republic, I was a member of the collegium. That is, I was already spinning in very high spheres. I met with Kunaev twice (Dinmukhamed Kunaev - in those years, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Kazakh SSR. - Approx. "Ferghana".) And even carried out his personal instructions. He was a member of the Politburo. And I, for example, carried out his instructions to conduct a check on the first secretary of the Kostanay Regional Committee of the Party of Borodin, who, by the way, was personally acquainted with Brezhnev. For four years I led the investigation in the prosecutor's office of Kazakhstan. That is, I want to say that at that time I already rotated in very high power structures of the union level.

Therefore, the fact that the Minister of Uzbekistan was sitting with me was not something out of the ordinary. But the content of the conversation then, in the fall of 1984, made an indelible impression on me - and I remember it to this day.

During those four hours that we talked with him, I realized what problems I would have to face and what a huge amount of you know what I would have to rake here. It was such a scale of work, such dimensions, that I realized that it was completely different from what I was told when the Central Committee persuaded me to agree to work in the Uzbek SSR and instructed in the Prosecutor General's Office of the Soviet Union. He revealed to me a picture with which the scale of work in Kazakhstan could not be compared.

In other words, you did not know what awaits you in Uzbekistan?

Even then, groups of Gdlyan, Lyubimov, Svidersky, that is, all allied investigators, were working in Uzbekistan. For this reason alone, one could roughly imagine what kind of legacy Sharaf Rashidov left after his death, and by that time almost a year had passed since he died. Nevertheless, when I was persuaded to move to work in Tashkent, I thought that allied investigation teams were working there, they were led by the allied prosecutor's office, and I would only be in charge of local prosecutors. Therefore, we agreed that in a year and a half I would put my work on my feet and leave with a calm soul. But when Islam Karimov told me everything somewhere in my first month of work in Uzbekistan, I immediately realized from his stories that there was too much work to be done, and I doubted whether I could organize it all - the scale was large, incomparable with what I encountered in Kazakhstan.

And then there was another interesting meeting. When I was already leaving in 1989, they began to denigrate my activities. Every day, my name was “watered down” both at the Congress of People’s Deputies and in the Uzbek press, leaflets began to appear, proclamations, and even later, when I was already transferred from Tashkent to Tselinograd, Karimov said in an interview that I failed the work, committed iniquity that thousands of people suffered from me.

I understand that this might not be the last interview. And I came to Tashkent and met with Karimov. He received me, and I told him: Islam Abduganievich, come on. I don't threaten you - and you don't threaten me. We worked together for four years, but I'm not going to be silent. I don't feel guilty, I didn't illegally arrest anyone. Yes, when you have to give thousands of sanctions, and then 3,000 investigators from all over the USSR worked in Uzbekistan, here it is impossible without trust in the investigators, because it is impossible to check everyone, and therefore, willy-nilly, you trust the one who directly investigates the case, you believe that he observes law. But keep in mind: if you mention my last name in an interview again, I will start giving interviews to everyone, in accordance with the official documents that I have, about your activities when you worked at the State Planning Commission, the Ministry of Finance. Kashkadarya region. Do you need it? Not? I don't need either.

To protect myself and my name, I was forced to take extreme measures. After this conversation, in any case, as far as I know, and until today, and 26 years have passed, in none of his interviews and publications Karimov has stooped to the point of personally classifying me among his enemies and the Uzbek people.

Telman Gdlyan and Nikolai Ivanov, 1989. Archive photo

But Gdlyan also accused you of thousands of innocently convicted ...

As for Telman Gdlyan... I wrote six books about my work, and if at first I was very cautious about Gdlyan's activities as an investigator, then in my last book, which was published a year ago, I simply called a spade a spade. With Gdlyan, our relationship was not something that was “stretched” - sometimes we almost rushed at each other with our fists. And Nikolai Ivanov - in general ... He is sick, and you should not waste time discussing him.

Gdlyan is not a fool, he was a good investigator even in Uzbekistan. When I arrived, the situation developed in such a way that I had to consider his appeals for arrest or sanctions for certain investigative actions. You won’t fly to Moscow every time for a sanction. And we are on the ground, so behind the scenes I was given the command to consider issues within the powers of the prosecutor, as the Deputy Prosecutor General of Uzbekistan. And I considered up to certain events. In order not to embarrass myself, I did not write about Ivanov, but all the people of the prosecutor's office and the Central Committee knew about it.

We are talking about the case when Ivanov came to my house at night and asked urgently for an arrest warrant. The fact that they came to me at night did not cause rejection - it happens that it is really urgently needed, there are three hours, no more. Investigators without a prosecutor could not do anything. They had no right to conduct even an elementary search without the sanction of the prosecutor.

When he brought me paper, I ask what it is. He says arrest warrants. Who, I ask. He says, they say, don't you trust us? – “And here I trust or I don’t trust, what’s the question?” - “What, they didn’t call you from Moscow? We actually detained him with the KGB, we just need to legalize all this.” I told him: “Dear, open the Code of Criminal Procedure again, read it.” I looked, and there, in the sanctions, the names are not affixed. Everything is described, how much he stole - in short, everything. And the names are not listed. In hindsight, apparently, he was going to put down. I kicked him out.

In Uzbekistan at that time there were 15 full-time investigators for especially important cases under the Prosecutor General of the Soviet Union, but no one supervised them, no one officially supervised them. Formally, if you approach, according to the law, according to the Constitution, there is prosecutorial supervision on the territory of Uzbekistan, and we must exercise it. But in fact they did not obey us. To exercise supervision, in addition to procedural powers, organizational ones are also needed, and he can “send” me. Sometimes it was like that - they sent. Yes, German Karakozov, head of the Investigation Department of the Prosecutor General's Office, came. But he came once every three weeks for two days. What can be done in two days? At that time, Gdlyan already had about 30 people arrested. If we are talking about supervision, then a person should sit and check everything thoroughly. And go check it out again - did he really give such confessions. Now there is audio, video, but then everything was just beginning. Therefore, the question arose - to create a department, put him in the prosecutor's office of Uzbekistan, and let him supervise your own investigators. If it is necessary to resolve some issues, Gdlyan should not run and take me by the breasts, but the prosecutor should issue sanctions. And the prosecutor must decide whether he supports Gdlyan or not. And this prosecutor, if he puts my name on sanctions, must convince me that everything is legal.

Telman Gdlyan and Nikolai Ivanov at the seizure of material evidence: gold was stored in cans in the form of jewelry. Archive photo

The Union caught up with me three thousand investigators from all over the country. Three thousand worked in Uzbekistan, and this is not counting the Uzbek investigators. We immediately agreed with the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Union, and a department was created that sat in the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Uzbekistan - employees of the central apparatus of the Ministry of Internal Affairs controlled and organized investigators who were seconded on cotton matters.

We agreed with the Ministry of Finance of the Soviet Union. For each case, examinations were carried out. From all over the Union, not only investigators were caught up, but also auditors, accountants, economists who conducted forensic accounting, forensic financial examinations. And from the Ministry of Finance of the USSR there was a group that sat with Islam Karimov in the Ministry of Finance of Uzbekistan and reported to him. And from the prosecutor's office of the Union there was no such thing. Therefore, we were constantly at war with the Gdlyan group. It cannot be said that other groups were subordinate to us, but at least they reported to us, showed all the materials and asked for sanctions. But with the Gdlyan group, the situation was completely different. Therefore, we had strife - until we at the board of the Prosecutor's Office of the Union did not put the question point-blank.

After I refused them to sign the sanctions, they began to go to the regional prosecutors. Prosecutors call me and ask: what to do, Gdlyan (or Ivanov) brought them. I say: send to the Union. And what does it mean - to the Union, you need it urgently! The law also limits in time: if you were detained, it means that in three days you need to decide whether you are guilty or not guilty, the search should be sudden - an hour, two, three, you need to resolve the issue. And they go to the prosecutors of the regions, and they are all afraid, especially the Uzbeks. They began to go to district prosecutors, where 90 percent are Uzbeks. And only after that put supervision.

And this epic with Gdlyan lasted until the nineties, when he was almost expelled from the prosecutor's office. And here's what's interesting - almost 30 years have passed, after that we never met either Ivanov or Gdlyan alive.

Gdlyan can be forgiven a lot. And Uzbekistan can be forgiven: to some extent, the situation there was difficult, it needed to be promoted, all these millions and gold - half was a bluff. All these exhibitions that the media showed are complete window dressing. But if you are an investigator, then investigate, not PR.

Investigator Gdlyan tells reporters about seized valuables

You also mentioned other, as you say, tales that have developed about that period of Uzbek history...

This is the first time I'm talking about this to the media. Haven't told anyone about this yet. Your first edition. We are talking about the reburial of Sharaf Rashidov in 1986.

Leonid Brezhnev and Sharaf Rashidov. Archive photo

Not so long ago, former Prime Minister of Uzbekistan Gairat Kadyrov spoke on TV. And I know him like crazy. Well, he was talking nonsense. He told how he took part in this reburial, how he organized all this, how he chose the grave, how he was with the Rashidov family, how he talked with his wife and daughter, etc., etc. None of this happened, and he did not solve anything.

He, before telling, at least asked if Gaidanov was still alive or not. Aleksey Buturlin (at that time the prosecutor of the republic) then fell ill, and I acted as the prosecutor of Uzbekistan. I was instructed to carry out all the measures for reburial within the framework of the law. Kadyrov didn't even know about it. Everything was done by the second secretary of the Central Committee Anishchev, the chairman of the KGB Golovin, myself, the first deputy minister of internal affairs Didorenko and the commander of the Central Asian military district. Gorbachev sent a resolution of the Politburo. And I had to formalize all this procedurally. To exhume a Muslim in a Muslim country. We understood what it meant, especially such an authority - Rashidov. We understood how the people might react and what the consequences might be. Therefore, Tashkent was surrounded by troops, the electricity was cut off, telephone communications were completely cut off in the city. The area where Rashidov was buried was surrounded by troops, and inside the troops were KGB officers.

But everything had to be done according to the law, and according to the law, exhumation, whatever the grounds, should be carried out only with the consent of relatives. His wife, Khursant Gafurovna, is alive. But it is clear that the wife will not give consent, especially since Rashidov's wife, with her enormous power, is worse than that of Raisa Gorbacheva. And we needed her written consent.

We have prepared a document with the text. We must go to her. I understood all the historical consequences, so I demanded that one of the leaders of the republic be with me. They called Kadyrov and ordered him to go with me. He almost fell on his knees in front of us, they say, I can’t, I have relatives here, I have to live here. I explained to him that his task would be only one - to stand behind my back, and machine gunners would stand behind him. Not a single word is required from him. But the protocol must contain the signature of one of the leaders of Uzbekistan, since it is a national republic.

We went. Then for the first time I found myself in Rashidov's apartment on German Lopatin Street. There is the building of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and behind is the house where Rashidov lived. Naturally, everything was already surrounded there, everyone was provided with equipment. Half past ten in the evening. We are told that everything is calm. Let's go. Some officer calls. Open. His wife is alone at home. Now, from the height of the past years, I understand how dirty and hard it is. And then I was only forty years old. A young man with tremendous power, no limits, basically. She is reported:

To you the Deputy Prosecutor of the Republic Oleg Ivanovich Gaidanov.

What for? For what purpose?

Always, if I appear anywhere, everyone immediately understands that either they came to arrest or to do searches. I say:

Excuse me, here is an order from Moscow, I must acquaint you with this order. That is why we have come for this purpose.

"Who are "we?

Me and Gairat Khamidullaevich (Kadyrov).

And Kadyrov was behind me somewhere, behind the threshold. I told him: "Gairat Khamidullaevich, come on in."

Khursant Gafurovna invites us to enter from the hallway into a small hall. And by the way, I was surprised. I've been to many great people's homes. And I was surprised how modest Rashidov's house was. It struck me. And so I went in and continued: “You know, with a not entirely pleasant mission, or rather, with a completely unpleasant one, we came to you, but yesterday the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee and the Council of Ministers of the USSR adopted a resolution. I ask you to read the decision." It had not been published anywhere at that time. We needed to get her signature. We understood that she would not sign, of course. But we are prepared for this. That is, we could state that the wife of Sharaf Rashidov was personally acquainted with the document, all this is accompanied by a video recording, an audio recording, so that there is some evidence that could be “sewn on”.

One of the many ceremonial portraits of Sharaf Rashidov

And then it began. She flared up and said it was blasphemy. I again offered to take a look. There were various points in the decree, including the removal of monuments, but the most important was the third - to rebury. To reburial, you need to do an exhumation. And according to the law, the exhumation is done with the consent of relatives ... But even that was not the main thing. “Inside” all this was the main super-task, which you cannot write about in a Central Committee resolution: to check the rumors that had spread quite actively by that time, especially against the backdrop of the revival of nationalist intonations in the life of the republic, that Rashidov was alive, that instead of Rashidov there a double is buried and Rashidov will return, that he took away part of the “gold-diamonds”, and part is buried with this double.

And so our main task was to conduct a forensic medical examination within four hours and establish whether Rashidov really lies in the grave and whether there is something else besides the body itself ...

The experts (and the best forensic experts of the Soviet Union and the best special equipment were brought from Moscow by plane) were told that they had three hours at their disposal. The soldiers disassemble the monument, the grave is opened, at one in the morning the coffin with the body is given to the experts, at four in the morning they must give us a written opinion. The maximum is an additional 30 minutes. All this was so strictly regulated, because at 5.30 they were supposed to be buried at the "Communist" cemetery and put up a monument, so that by 6.00 everything would be completely ready. Everything had to be done from 10 pm to 6 am. For this period of time, Tashkent was under martial law. The capital was surrounded, it was left without communications and electricity.

And as soon as I told Khursant Gaflevelov about the exhumation and that she had to give her consent... Then KGB General Golovin told me: “Oleg Ivanovich, you were talking to her, and I was looking at Kadyrov. Both his arms and legs were shaking, I was afraid that he would now fall on his knees in front of her.

I sat at the oval table, laid out the papers. Rashidova did not sit down, read while standing, threw down her pen - and suddenly, with some incomprehensible movement for me ... My attention was still riveted to the papers, I desperately needed to get her signature - and suddenly I see, she somehow turns, there are two There were armchairs, a table between the chairs, and a crystal vase on the table. And when I sat down, Gairat Khamidullaevich was right in front of her eyes. He stood tall in front of her. And I see, she grabs this vase and “shoots” it right into him. And I have no idea how he could dodge such a throw. Everything happened in an instant, but Gairat Khamidullaevich sat down and the vase, passing him, hit a large, huge glass, which was behind him. All, of course, to smithereens. And, apparently, from fright, and not from the blow of this crystal vase, Kadyrov fell.

Colonels and generals are standing nearby, I jumped up and asked: “What are you doing?”. And she began in Uzbek, turning to Kadyrov, to say something quickly to him. I don’t understand and didn’t understand the Uzbek language, and they translated to me that she cursed him and said that, well, Gaydanov, the demand from him is small, but you are a bastard, who are you, what are you doing ... yes they will cursed are your children, grandchildren, and so on...

And we had a doctor with us, because we foresaw a similar scenario. She was immediately seated, the doctor, as best he could, calmed her hysteria. And I already think that the operation failed and I did not complete the task. Of course, I wanted to comply with the formalities. Although the fact that she refuses to sign, we also provided. We had a backup option for this case, and not one. For example, if something happens to her, and the worst could happen, for example, a heart break, because she lived with Rashidov all her life, idolized him, however, like him, we had the second option, son Volodya, by this time he was a major in the KGB, and Gulya's daughter, a doctor of chemical sciences. And there, and there everyone was already controlled. If it does not work out here, we are immediately transported to them.

I then suggested that the son is not needed, if the mother is ill, it would be better if Gulya was brought here. She, apparently, was not far away, because literally in 5-7 minutes, while the doctor measured the pressure, gave an injection, Gulya was brought. I explained everything to her again... and she fainted.

Gulya was more reasonable. When I came to my senses, I realized that in any case, whether she signed or not, there was a decision of the Politburo. Everything. She asked how everything would happen, where she would be buried, if she could participate. I said that she can, but no one else can. Even relatives cannot be told. In two days everything will be possible, but not earlier, because everything will be under guard there: in the republic there was an ambiguous attitude towards Rashidov, they could desecrate.

Thus, in the morning, as planned, the operation was completed.

Returning to the personality of Islam Karimov, then and now. How do you think he has changed over this time?

When you know a person from the inside, it is easier for you to explain certain government decisions. He's always been like that. He still goes where it's profitable. To the Americans means to the Americans. The Americans gave in the teeth - he ran to Putin. Putin gave money, wrote off the debt, - again went over to the Americans ... In the world that developed after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was very difficult for the leader of the country to turn around.

Karimov rehabilitated everyone involved in the "cotton case", and many believe that a monstrous injustice was shown against Uzbekistan. What do you say about this?

According to official statistics, over 800 criminal cases of embezzlement and bribery were opened in cotton cases. For 25 million inhabitants of the republic, this is not such a grandiose scale as the media imagined. It's a lot, but not outrageous. So, in all these cases, as of 1989, charges were brought against 20,000 defendants. It turns out 20-30 people per case. This is normal for cases of this category. Only 4,500 people out of 20,000 were directly prosecuted. The remaining 15,000 were amnestied. Their criminal cases were dropped. All of them pleaded guilty, because without admitting guilt it was impossible to release them from criminal liability. Such was the law. And so he has remained to this day.

There is no need to remind the people of Uzbekistan about the situation in the republic in the seventies and eighties. Lack of rights and corruption - especially in the prosecutor's office and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Suffice it to recall that Alexei Vladimirovich Buturlin and I managed to rehabilitate almost a thousand citizens illegally prosecuted by the prosecutor's office and the Ministry of Internal Affairs in that period in the first year. In one of my first books, In the Position of Kerensky, in Stalin's Cabinet, I cited specific cases. I still keep letters of thanks from these people.

Of the 4.5 thousand convicted in the "cotton case", the longest terms are approximately 7-8 years in prison. Another thing is that apart from the so-called "cotton cases", the damage on which amounted to 4-5 billion rubles in prices of 81-85, at that time there was such a situation that Uzbekistan became the first republic in the USSR, in which, after 30 organized crime revived.

There was a lot of money in Uzbekistan, for which crooks and bandits of all stripes flocked from all over the Union. Cotton was stolen. Yes. Postscripts were engaged in each collective farm and state farm. But in order to send an empty wagon to Ivanovo, like a wagon “with cotton”, in order to steal 100 thousand rubles, which, for example, this wagon costs, it is necessary to prepare a whole bag of permits and accompanying documents. Therefore, a huge mass of people took part in this chain. The example, of course, is simplified, but it was not only in cotton growing, it was the same in all Uzbek agriculture. During the reign of Rashidov, a system developed that was almost impossible to resist. So there were no innocents there. Another thing is that the Uzbek authorities themselves, as we advised, could help their citizens, under various pretexts, freeing them from criminal liability.

Karimov is right in this regard, only that it was indeed a campaign. And not the last role in this campaign was played by Mikhail Gorbachev. So, when Yuri Andropov came to power in the USSR, the well-known “Andropov cleansings” began throughout the country. And the wave reached the Stavropol Territory. A large group of employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the KGB went there. And there appeared official testimony against Raisa Gorbachev. Similarly, in Uzbekistan, everything started with little things. And when Andropov was replaced by Gorbachev "just in time", he, in order to deflect the blow from the Stavropol Territory and not to disgrace him, turned all his attention to Uzbekistan. All law enforcement forces were sent there. Islam Karimov knows this very well, and in this he is right.

If someone is interested in my personal opinion, then I believe that if it were not Gorbachev who became the leader of the USSR, but another person, investigations in Uzbekistan might have been, but would not have reached such a scale and such scope.

And the last question. How can you yourself evaluate your work in Uzbekistan during that period today?

Of course, there are many people who evaluate our work differently. But my conscience is clear, I honestly and conscientiously fulfilled my professional duty, fulfilled the law - and we did not write it. Were there any mistakes? Unfortunately, there were. And the reasons are not even in the amount of work that Moscow has dumped on us. The main reason for mistakes is quite banal - betrayal. His - betrayals, and today I can say about this - were many even among those who came to fight lawlessness and corruption.

Interviewed by Dmitry Alyaev

Many have probably heard about the "cotton case" - the main criminal process of perestroika. Do you know how it happened? There is a reason to remember - exactly 22 years ago, 12/25/1991. (that is, the day before the legal consolidation of the cessation of the existence of the USSR) President of Uzbekistan I. Karimov pardoned all those convicted in the "Uzbek case" who were serving sentences on the territory of the republic. And now in Uzbekistan that story is assessed as follows: “At the end of the 80s, the “cotton case” was fabricated, which was referred to as the “Uzbek case”, which brought humiliation to the national pride of the Uzbek people.”

To put it simply, it's just pieces of cotton on the branches

By 1980, cotton in the USSR had become a strategic raw material, a source of currency, and it was exported. At the same time, on average, out of 8 million tons of cotton officially produced in the USSR annually, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan each gave one million, and a little Azerbaijan. And 6 million tons were produced in Uzbekistan, and cotton then occupied 65% of all irrigated land in Uzbekistan, which was turned into the main cotton base of the Soviet Union (currently Uzbekistan produces 5% of the world's cotton production).

From about the 60s, every year, plans for the production of cotton began to increase annually, until they reached the limit of the possibility of its production in the republic. In the really best, fruitful years, under good weather conditions, no more than five million tons per year could be collected in Uzbekistan. But the never-ending orders to increase cotton production, regardless of weather conditions, continued to come. And then, in response, there were "subscripts" - reports on ever-higher numbers of cotton harvests.

It was done this way: an unrealistic order for the extraction of raw cotton was dumped on state farms and collective farms. They see that the amount of cotton set by the plan simply cannot be collected. And then they write fictitious time sheets for allegedly harvested cotton, and go to the cotton plant for a paper on the acceptance of a non-existent crop. The money received on fictitious reports for cotton, which is not available, basically goes to the management of the cotton plant.

This job is not easy

But the cotton factory also needs to hide the fact that it does not have cotton, and money is already flowing into the industry for processing raw cotton into raw materials for light industry. They write out papers on the acceptance of non-existent cotton from the cotton plant, and receive suitcases with money for this.

But they also need to hide that they have nothing to process, and then wagons are sent from Uzbekistan to the weaving and sewing enterprises of the Union republics, in which, under the guise of first-grade cotton, third-grade cotton is transported. Or under the guise of third grade cotton, cotton waste - lint and hoot. Or under the guise of wagons, to the eyeballs stuffed with cotton, the wagons are empty and half empty.

The leaders of the cotton enterprises of the Union republics issue documents stating that they have received full wagonloads of high-grade cotton in exchange for suitcases with money. Fixed rates were even set: for an empty Uzbek cotton wagon - a fee of ten thousand rubles, for a half-empty one with sorting - three to six thousand. And the shaft of postscripts and write-offs is already rolling through the weaving and sewing enterprises further - into trade.

Throughout this chain, the amount of cotton harvested in Uzbekistan decreased on paper due to its shrinkage, shrinkage, and fumes. And in Uzbekistan they reported on the early fulfillment and overfulfillment of the plans of the party and government (they are also socialist obligations). State farms-collective farms reported to the district committees, those to the regional committees, those to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Uzbek SSR, the latter to the Central Committee of the CPSU, with submissions to Moscow for orders and titles of Heroes of Socialist Labor.

I repeat, under the most favorable circumstances, no more than five million tons per year could be harvested in the republic. In bad years - four tons. And the reporting cost was six million annually, and the state paid for these six million. The postscripts on cotton are now estimated at one and a half billion Soviet rubles, but no one knows the exact figure.

Tashkent metro

Part of this money went to the infrastructure that was being created in Uzbekistan: schools, roads, hospitals, including the construction of the Tashkent metro at the expense of part of this money. The resolution on its construction was adopted with the condition of the republic's equity participation, otherwise Moscow refused to finance the project.

Part of the money was spent on bribes from top to bottom along the entire chain from the Uzbek collective farm / state farm to the weaving / clothing factory / combine. With this money, the “bai order” was revived in Uzbekistan: paying tribute to the top, each participant in this scheme fed from his patrimony, managing money, equipment, buildings, and even ordinary workers as his property. Amidst the horrendous poverty of the villages, this money was used to build luxurious palaces of collective farm chairmen and state farm directors, as well as family estates of the Soviet nomenklatura with courts and swimming pools.

And part of these funds went to Moscow, but in an interesting way (and this was a trifle compared to the total amount). Suppose an employee of the Central Committee of the CPSU is called before the holiday by a petty official from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the UzSSR: “We want to give fruits to your family - we have such a custom”. A box of apples, grapes and other sultanas is loaded onto the plane and delivered to the apartment of the party apparatchik. The wife opens the parcel in the kitchen, and there are 10 thousand rubles.

The person does not know who transferred this money to him, for anything in particular. Knows just from Uzbekistan. So what should he do? Go and write a memorandum: so they say so, I don’t know who, I don’t know why they threw 10 thousand? They drag you in, torture you with questions, and even make you guilty. And a petty official from Tashkent will say: I don’t know anything about any money, I handed over fruit. And don't throw money away...

This is how it all went on for years, until Brezhnev died ...

Leonid Brezhnev and Sharaf Rashidov

Moscow investigators came to grips with Uzbekistan under Andropov, and it is believed that this caused the sudden death of the owner of the republic, Sharaf Rashidov (there were rumors of his suicide). The investigative group worked in Uzbekistan for six years until 1989, by the beginning of which, within the framework of the “cotton case”, 790 criminal cases were considered by the courts, in which more than 20 thousand people were involved.

Of these, about 4,500 people were prosecuted, including: the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan, Usmankhodzhaev; Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Republic Khudaiberdiev; 3 secretaries of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan; 7 first secretaries of regional committees; 430 directors of state farms and chairmen of collective farms and 1,300 their deputies and chief specialists; 84 directors of cotton factories and 340 chief specialists of these factories; 150 light industry workers in Uzbekistan, the RSFSR, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Georgia and Azerbaijan; party, Soviet workers, employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the prosecutor's office.

Brezhnev's son-in-law General Churbanov also fell under the distribution, and with him 6 more generals of the Uzbek police. Four high-profile defendants committed suicide before trial. Usmanov, the minister of the cotton-cleaning industry of Uzbekistan, and Muzafarov, head of the OBKhSS of the Bukhara region, were sentenced to death. During the searches, jewelry and money worth hundreds of millions of rubles were seized.

April 28, 1988 in the Marble Hall of the USSR Prosecutor's Office, an exhibition was held

Among those prosecuted in this case, Uzbeks and Slavs were almost equally divided, so calling the “cotton case” an “Uzbek case” is indeed not entirely correct. And you know what I'll say? Compared to what began in the Soviet Union after 1989, and continues in the fragments of the USSR to this day, it all looks so small...

Gold for the party. The secret of Rashid's millions.

Night from 20 to 21 May 1986. The central square of Tashkent is cordoned off by the military. Several people in civilian clothes are watching as the soldiers move the tombstone and open the grave, located in the park on the square. Here was buried the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Uzbek SSR Sharaf Rashidovich Rashidov. But who is really in the grave? Is it really a double, and that one, the other, disappeared, taking the stolen millions? Where did the fabulous money from cotton additions go? Who promoted the famous "cotton business"? How did it all start and how did it end? How did Rashidov's promise to Brezhnev to pick more cotton turn into a tragedy for the Uzbek people?

Released: Channel 5

Many have probably heard about the "cotton case" - the main criminal process of perestroika. Do you know how it happened? There is a reason to remember - exactly 22 years ago, 12/25/1991. (that is, the day before the legal consolidation of the cessation of the existence of the USSR) President of Uzbekistan I. Karimov pardoned all those convicted in the "Uzbek case" who were serving sentences on the territory of the republic. And now in Uzbekistan that story is evaluated as follows: “At the end of the 80s, a “cotton case” was fabricated, which was referred to as the “Uzbek case”, which brought humiliation to the national pride of the Uzbek people”.

By 1980, cotton in the USSR had become a strategic raw material, a source of currency, and it was exported. At the same time, on average, out of 8 million tons of cotton officially produced in the USSR annually, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan each gave one million, and a little Azerbaijan. And 6 million tons were produced in Uzbekistan, and cotton then occupied 65% of all irrigated land in Uzbekistan, which was turned into the main cotton base of the Soviet Union (currently Uzbekistan produces 5% of the world's cotton production).

To put it simply, it's just pieces of cotton on the branches

From about the 60s, every year, plans for the production of cotton began to increase annually, until they reached the limit of the possibility of its production in the republic. In the really best, fruitful years, under good weather conditions, no more than five million tons per year could be collected in Uzbekistan. But the never-ending orders to increase cotton production, regardless of weather conditions, continued to come. And then, in response, there were "subscriptions" - reports on ever-higher numbers of cotton harvests.

It was done this way: an unrealistic order for the extraction of raw cotton was dumped on state farms and collective farms. They see that the amount of cotton set by the plan simply cannot be collected. And then they write fictitious time sheets for allegedly harvested cotton, and go to the cotton plant for a paper on the acceptance of a non-existent crop. The money received on fictitious reports for cotton, which is not available, basically goes to the management of the cotton plant.

This job is not easy

But the cotton factory also needs to hide the fact that it does not have cotton, and money is already flowing into the industry for processing raw cotton into raw materials for light industry. They write out papers on the acceptance of non-existent cotton from the cotton plant, and receive suitcases with money for this.

But they also need to hide that they have nothing to process, and then wagons are sent from Uzbekistan to the weaving and sewing enterprises of the Union republics, in which, under the guise of first-grade cotton, third-grade cotton is transported. Or under the guise of third grade cotton, cotton waste - lint and hoot. Or under the guise of wagons, to the eyeballs stuffed with cotton, the wagons are empty and half empty.

The leaders of the cotton enterprises of the Union republics issue documents stating that they have received full wagonloads of high-grade cotton in exchange for suitcases with money. Fixed fees were even set: for an empty Uzbek cotton wagon - a fee of ten thousand rubles, for a half-empty one with sorting - three to six thousand. And the shaft of postscripts and write-offs is already rolling through the weaving and sewing enterprises further - into trade.

Throughout this chain, the amount of cotton harvested in Uzbekistan decreased on paper due to its shrinkage, shrinkage, and fumes. And in Uzbekistan they reported on the early fulfillment and overfulfillment of the plans of the party and government (they are also socialist obligations). State farms-collective farms reported to the district committees, those to the regional committees, those to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Uzbek SSR, the latter to the Central Committee of the CPSU, with submissions to Moscow for orders and titles of Heroes of Socialist Labor.

I repeat, under the most favorable circumstances, no more than five million tons per year could be harvested in the republic. In bad years - four tons. And the reporting cost was six million annually, and the state paid for these six million. The postscripts on cotton are now estimated at one and a half billion Soviet rubles, but no one knows the exact figure.

Tashkent metro

Part of this money went to the infrastructure that was being created in Uzbekistan: schools, roads, hospitals, including the construction of the Tashkent metro at the expense of part of this money. The resolution on its construction was adopted with the condition of the republic's equity participation, otherwise Moscow refused to finance the project.

Part of the money was spent on bribes from top to bottom along the entire chain from the Uzbek collective farm / state farm to the weaving / clothing factory / combine. With this money, the “bai order” was revived in Uzbekistan: paying tribute to the top, each participant in this scheme fed from his patrimony, managing money, equipment, buildings, and even ordinary workers as his property. Amidst the horrendous poverty of the villages, this money was used to build luxurious palaces of collective farm chairmen and state farm directors, as well as family estates of the Soviet nomenklatura with courts and swimming pools.

And part of these funds went to Moscow, but in an interesting way (and this was a trifle compared to the total amount). Suppose an employee of the Central Committee of the CPSU is called before the holiday by a petty official from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the UzSSR: “We want to give fruits to your family - we have such a custom”. A box of apples, grapes and other sultanas is loaded onto the plane and delivered to the apartment of the party apparatchik. The wife opens the parcel in the kitchen, and there are 10 thousand rubles.

The person does not know who transferred this money to him, for anything in particular. Knows just from Uzbekistan. So what should he do? Go and write a memorandum: so they say so, I don’t know who, I don’t know why they threw 10 thousand? They drag you in, torture you with questions, and even make you guilty. And a petty official from Tashkent will say: I don’t know anything about any money, I handed over fruit. And don't throw money away...

This is how it all went on for years, until Brezhnev died ...

Leonid Brezhnev and Sharaf Rashidov

Moscow investigators came to grips with Uzbekistan under Andropov, and it is believed that this caused the sudden death of the owner of the republic, Sharaf Rashidov (there were rumors of his suicide). The investigative group worked in Uzbekistan for six years until 1989, by the beginning of which, within the framework of the “cotton case”, 790 criminal cases were considered by the courts, in which more than 20 thousand people were involved.

Of these, about 4,500 people were prosecuted, including: the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan, Usmankhodzhaev; Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Republic Khudaiberdiev; 3 secretaries of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan; 7 first secretaries of regional committees; 430 directors of state farms and chairmen of collective farms and 1,300 their deputies and chief specialists; 84 directors of cotton factories and 340 chief specialists of these factories; 150 light industry workers in Uzbekistan, the RSFSR, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Georgia and Azerbaijan; party, Soviet workers, employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the prosecutor's office.

Brezhnev's son-in-law General Churbanov also fell under the distribution, and with him 6 more generals of the Uzbek police. Four high-profile defendants committed suicide before trial. Usmanov, the minister of the cotton-cleaning industry of Uzbekistan, and Muzafarov, head of the OBKhSS of the Bukhara region, were sentenced to death. During the searches, jewelry and money worth hundreds of millions of rubles were seized.

April 28, 1988 in the Marble Hall of the USSR Prosecutor's Office, an exhibition was held

Among those prosecuted in this case, Uzbeks and Slavs were almost equally divided, so calling the “cotton case” an “Uzbek case” is indeed not entirely correct. And you know what I'll say? Compared to what began in the Soviet Union after 1989, and continues in the fragments of the USSR to this day, it all looks so small...

In February 1976, the XXV Congress of the CPSU opened in Moscow, at which representatives of labor collectives reported on the implementation of the plan. New directions for the development of the national economy for the next 4 years were adopted.

background

The first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Uzbek SSR, Sharaf Rashidov, loudly announced from the rostrum that now the republic harvests 4 million tons of cotton every year - and will collect 5.5 million tons. On this day, he literally doomed his people to slavery.

In the 70s, the Uzbek SSR was the most prosperous and stable republic in Central Asia. There are no riots on an ethnic basis. The highest level of education of the urban population. Advanced agriculture compared to neighboring republics. The head of the republic, Sharaf Rashidov, is respected by all local clans, but, most importantly, by the Kremlin. For almost 25 years he headed Uzbekistan. He had a special relationship with Brezhnev, he enjoyed the unlimited confidence of the General Secretary.

There was an unspoken agreement between the Center and the Asian republics - "you remain completely loyal to the supreme power of the Soviet Union, keep the republic from unrest - but we do not touch you, we allow you to remain in the feudal system." Did Rashidov know what Adylov was doing in his household? He knew, but treated him with great respect. Its agro-industrial complex beat all records for the collection of the most valuable raw materials for the republic.

Ahmadjon Adylov was almost a mythical character. This is a man who has lost his sense of reality - he imagines himself a "regional leader", a person who can do everything on the territory of his state farm. Adylov headed the largest association of collective farms and state farms "Papsky Agro-Industrial Complex". Newspapers trumpeted his achievements in agriculture and labor records in the cotton harvest. But among ordinary workers, stories about him were different: Ahmadjon was a real tyrant who turned the collective farmers working for him into slaves. He built a prison in which the guilty collective farmers died of hunger and torture. Roy Medvedev, a historian, comments: “People lived in complete poverty. These were the poorest villages.” And about the wealth of the "owner" they said that he found and hid the treasures of Emir Timur, "paved" an underground road to China. He was a close friend of Sharaf Rashidov, and he turned his district into a criminal territory, where he had his own police, his own prisons, his own courts.

Andrey Gruzin of the Institute of CIS Countries notes that even today cotton remains an important “currency”. On the stock exchanges, first of all, the price of gold, the price of a barrel of oil and the price of cotton.

Until the end of the 1950s, orchards flourished in Uzbekistan and a lot of vegetables were grown. But then the whole republic was swept by the race for cotton, because it was needed not only for the production of cotton wool and fabrics, but also for the defense complex. Gunpowder and components for explosives were made from Uzbek cotton. Therefore, the cotton industry was financed from the Union Center directly and on a priority basis.

Cotton has become a national idea. Collective farmers and city dwellers, even children, worked in the cotton fields. Roy Medvedev notes that "schoolchildren did not study until winter, but worked in the cotton fields." The health of the nation was undermined because the cotton fields were treated with herbicides and pesticides, and this is very harmful to people's health.

Representatives of the Uzbek SSR received orders and titles for new achievements in the cotton industry. In 1975, they set a record for the collection of cotton - 4 million tons of "white gold" were collected in a year. And Sharaf Rashidov promised Brezhnev: "We will soon give the country 5 million tons." And Leonid Ilyich put forward a counter proposal - "maybe 6 million?" On February 3, 1976, Rashidov set a new task for the republic - to reach a new milestone in the collection of 5 million tons, and by 1983 to collect 6 million tons. He was well aware that Uzbekistan would not collect so much.

How 6 million tons of cotton was grown

But already in 1977, Uzbekistan presents a report that the tasks set by the party are being fulfilled. Judging by paper reports, the republic is producing more and more cotton. In the Kremlin, Rashidov is again rewarded for his success. Although everyone understood perfectly well that Uzbekistan simply could not produce such a quantity of cotton. What did they do to “overfulfill” the plan? They just attributed tons of cotton on paper, in fact there was none. The secretaries of the regional committees, the collective farmers and everyone who had anything to do with the production of cotton fabricated reports.

Akhmadjon Adylov increases the norm of working hours for collective farmers. For the exhausted people, this was not in vain, the death rate began to grow. Pregnant women were forced to work, and the number of miscarriages and premature births increased. The concept of "women's health" for Uzbekistan was an empty phrase. So cotton became not the wealth of Uzbekistan, but its curse.

For all significant holidays in the USSR, there were norms of “increased obligations”. It was impossible to work, but it was necessary to fulfill the norm. Then the cotton pickers began to put stones in the sacks to increase the weight. First, the foreman makes the postscript. Then the chairman of the collective farm ascribes. Then the head of the region assigns. Uzbekistan receives a huge amount of money for cotton, including for the assigned tons. They go into the pockets of local officials. Of course, you need to hide the fact that the required amount of cotton is not available. The shrinkage of cotton begins, its shaking, there are regular "fires" at the factories. A system was born in which everyone was tied up: cotton pickers, foremen, chairmen of collective farms, and heads of districts. Later it was established that the director of the plant, who accepted non-existent raw materials, was given a bribe - 10 thousand rubles for one empty car.

Sharaf Rashidov in 1974 received the title of Hero of Socialist Labor. At this time, the republic confidently went from 4 million tons to 5.5. Rashidov felt calm - the slightest criticism of the republic was suppressed by Brezhnev, so corruption and the sale of posts grew in Uzbekistan. Brezhnev treated Rashidov as a close friend. Everything suited the Secretary General: the growing cotton harvest, the positive image of the republic and expensive gifts.

After Brezhnev's death

November 10, 1982 Leonid Brezhnev died. The throne under Rashidov swayed immediately after the funeral of the Secretary General. Yuri Andropov came to power, who since the 70s had been accumulating dirt on the authorities of Uzbekistan. Andropov roughly represented the scale of theft and corruption in the republic. On October 31, 1983, Rashidov received a phone call from Andropov. The General Secretary asked about the cotton this year. Rashidov replied that everything was according to plan, they say, we will hand it over. In response, he heard: “how many real and attributed tons of cotton will this year?”. What happened next remains a mystery. Officially, Rashidov had a stroke. But there is a version that he drank poison.

"Cotton Business"

The "cotton business" was gaining momentum. Hundreds of people were called in for interrogation every day. Panic broke out in Uzbekistan. The most respected and inviolable people were put behind bars.

In five years, from 1979 to 1985, 5 million tons of cotton were attributed. 3 billion rubles were paid from the state budget, of which 1.4 billion were actually stolen.

The control bodies were not overseers, but a cog in the vast mechanism of the cotton mafia. They became more and more involved in the process of "sawing" the budget, mutual deception. Millions of cash rubles, several tons of gold coins, jewelry were confiscated - there was so much of everything that it was hard to imagine how you could earn so much, receiving 180 rubles a month.

Andropov understands that you cannot solve crimes with the help of the local police, and sends from Moscow a commission of the USSR prosecutor's office, which included investigators from all over the Soviet Union. 3,400 operatives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the KGB, almost 700 accountants and economists - almost 5,000 people, the entire headquarters for the investigation of "cotton cases"

Adylov preferred to cajole the auditors: he slaughtered 10 sheep, laid a chic table, and for all three days he plentifully fed and watered the Moscow guests. But in order to investigate the postscripts of cotton, a clear head and attentiveness are needed, which Adylov's guests did not have by the end of the third day.

Andropov personally controlled the "cotton business". Investigators reviewed a huge number of cases and interrogated 56,000 people. Anatoly Lyskov, a former employee of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs, shares his memories: “So many years have passed, but the numbers are still in front of my eyes. 22 million 516 thousand 506 rubles 06 kopecks - such theft was proved. The pre-trial detention center was overcrowded, and all those arrested partly admitted their guilt: “Yes, I received a bribe, but I gave it to someone else” - and so on in a circle.

It became clear that the cotton mafia was in control not only of Uzbekistan, but also of people in Moscow. Also in cities where cotton and cotton factories worked. Andropov decided: to judge people to the fullest extent, for communion with Uzbek cotton.

Investigation team of Nikolai Ivanov and Telman Gdlyan

The most active investigative group was the Gdlyan-Ivanov group. Gdlyan came to Uzbekistan from the Ulyanovsk region, Ivanov - from Murmansk. Both have long dreamed of a career in Moscow. Their main chance to take up posts in the capital is the “cotton business”. Gdlyan and Ivanov decided that the road to glory should be short. Gdlyan "split" people with the help of long conversations, during which he constantly smoked. From the lack of oxygen, people were ready to confess to anything. For Gdlyan, the queen of evidence was the testimony of a person, if a person confessed, then this is quite enough.

Question - as he admitted. Gdlyan's group used a lot of illegal methods: keeping suspects in a pre-trial detention center for several years, being in the same cell with repeat offenders, threats, beatings, torture, arrests of relatives.

Gdlyan and Ivanov's group forgot the principle of the presumption of innocence. Gdlyan's phrase "anyone can be imprisoned" is indicative. The rules of the investigation of a criminal case were violated for the sake of the result - to arrest as many people as possible. The prosecutor of Uzbekistan signed an arrest warrant when there was not even the name of the arrested person, and KGB agents acted as witnesses.