Former chief military adviser to Rosoboronexport, former Russian Minister of Defense

Former chief military adviser to the Federal State Unitary Enterprise "Rosoboronexport", former Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation, army general. Hero of the Soviet Union, awarded the Order of Lenin, the Red Banner, the Red Star, "For Service to the Motherland in the Armed Forces of the USSR", "For Personal Courage", as well as the Afghan Order of the Red Banner. He was a defendant in the case of the murder of journalist Dmitry Kholodov. Died in Moscow on September 23, 2012.

Pavel Sergeevich Grachev was born on January 1, 1948 in the village of Rvy, Tula region. He graduated with honors from the Ryazan Higher Airborne Command School (1969) and the Frunze Military Academy (1981). In 1981-1983, as well as in 1985-1988, Grachev took part in hostilities in Afghanistan. In 1986, he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union "for performing combat missions with minimal casualties." In 1990, after graduating from the Military Academy of the General Staff, Grachev became deputy commander, and from December 30, 1990, commander of the USSR Airborne Forces.

In January 1991, Grachev, by order of the USSR Minister of Defense Dmitry Yazov, introduced two regiments of the Pskov Airborne Division into Lithuania (according to some media reports, under the pretext of assisting the military registration and enlistment offices of the republic in forced recruitment into the army).

On August 19, 1991, Grachev, following the order of the State Emergency Committee, ensured the arrival of the 106th Tula Airborne Division in Moscow and its taking under the protection of strategically important objects. According to media reports, at the beginning of the putsch, Grachev acted in accordance with Yazov’s instructions and prepared paratroopers together with KGB special forces and Ministry of Internal Affairs troops to storm the building of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR. On August 20, Grachev, together with other high-ranking military officers, informed the Russian leadership of information about the intentions of the State Emergency Committee. The media also voiced a version according to which Grachev warned Boris Yeltsin about the impending coup on the morning of August 19.

On August 23, 1991, Grachev was appointed chairman of the RSFSR State Committee for Defense and Security with a promotion in rank from major general to colonel general and became first deputy minister of defense of the USSR. After the formation of the CIS, Grachev became Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the United Armed Forces of the CIS (CIS Joint Forces), Chairman of the Russian State Committee on Defense Issues,.

In April 1992, Grachev was appointed first deputy minister of defense of Russia, in May he first became acting minister and then minister of defense in the government of Viktor Chernomyrdin. In the same month, Grachev was awarded the rank of army general. Grachev, according to a number of media reports, himself admitted his lack of experience, so he surrounded himself with experienced and authoritative deputies, mainly “Afghan” generals.

The role of Grachev in the operation to withdraw Russian troops from Germany was assessed ambiguously by the media. Noting the complexity and scale of the military operation (it became the largest ever carried out in peacetime), the press also pointed out that, under the guise of preparing and carrying out the withdrawal of troops, corruption and theft flourished. However, none of the senior military officials who served in Germany were convicted, although several trials took place.

In May 1993, Grachev became a member of the working commission to finalize the presidential draft of the Russian Constitution. In September 1993, after presidential decree number 1400 on the dissolution of the Supreme Council, he stated that the army should obey only Russian President Yeltsin. On October 3, Grachev called troops to Moscow, who the next day after the tank shelling stormed the parliament building. In an interview published after his death, Grachev admitted that shooting at the White House from tanks was his personal initiative: in his own words, in this way he hoped to “scare” the defenders of the Supreme Council and avoid losses during the assault. According to Grachev himself, nine paratroopers died during the capture of the building, and there were losses on the opposite side (“they killed a lot of them... no one simply counted them”). In October 1993, Grachev was awarded the Order “For Personal Courage,” as stated in the decree, “for the courage and courage shown in suppressing the armed coup attempt on October 3-4, 1993.” On October 20, 1993, Grachev was appointed a member of the Russian Security Council.

In 1993-1994, several extremely negative articles about Grachev appeared in the press. Their author, Moskovsky Komsomolets journalist Dmitry Kholodov, accused the minister of involvement in a corruption scandal in the Western Group of Forces. On October 17, 1994, Kholodov was killed. A criminal case was opened into the murder. According to investigators, the crime, in order to please Grachev, was organized by retired Airborne Forces Colonel Pavel Popovskikh, and his deputies acted as accomplices in the murder. Subsequently, all suspects in this case were acquitted by the Moscow District Military Court. Grachev was also a suspect in the case, which he learned about only when the decision to terminate the criminal case against him was read out. He denied his guilt, pointing out that if he spoke about the need to “deal with” the journalist, he did not mean his murder.

According to a number of media reports, in November 1994, a number of career officers of the Russian army, with the knowledge of the leadership of the Ministry of Defense, took part in hostilities on the side of the forces in opposition to Chechen President Dzhokhar Dudayev. Several Russian officers were captured. The Minister of Defense, denying his knowledge of the participation of his subordinates in hostilities on the territory of Chechnya, called the captured officers deserters and mercenaries and stated that Grozny could be taken in two hours with the forces of one airborne regiment.

On November 30, 1994, Grachev was included in the group leading the actions to disarm gangs in Chechnya; in December 1994 - January 1995, he personally led the military operations of the Russian army in the Chechen Republic from headquarters in Mozdok. After the failure of several offensive operations in Grozny, he returned to Moscow. Since that time, he has been subject to continuous criticism both for his desire for a forceful solution to the Chechen conflict and for the losses and failures of Russian troops in Chechnya.

On June 18, 1996, Grachev was dismissed (according to some media reports, at the request of Alexander Lebed, who was appointed Assistant to the President for National Security and Secretary of the Security Council). In December 1997, Grachev became the chief military adviser to the general director of the Rosvooruzhenie company (later the FSUE Rosoboronexport). In April 2000, he was elected president of the Regional Public Fund for Assistance and Assistance to the Airborne Forces "Airborne Forces - Combat Brotherhood". In March 2002, Grachev headed the General Staff commission for a comprehensive review of the 106th Airborne Division stationed in Tula.

On April 25, 2007, the media reported that Grachev was dismissed from the post of chief military adviser to the general director of the Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rosoboronexport. The Chairman of the Union of Russian Paratroopers, Colonel General Vladislav Achalov, with reference to whom the media disseminated this information, said that Grachev was removed from the post of adviser “in connection with organizational arrangements.” On the same day, the press service of Rosoboronexport clarified that Grachev was relieved of his post as adviser to the director of the Federal State Unitary Enterprise and seconded to the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation to resolve the issue of further military service on February 26, 2007. The press service explained this personnel decision by the abolition of the institution of seconding military personnel to Rosoboronexport on January 1, 2007. Information about Grachev’s resignation appeared in the media a day after the death of the first Russian President Yeltsin, who appointed the ex-Minister of Defense to the position of adviser to the state company by a special decree.

In June 2007, Grachev was transferred to the reserve and appointed chief adviser - head of a group of advisers to the general director of the production association "Radio Plant named after A. S. Popov" in Omsk.

On September 12, 2012, Grachev was admitted to the intensive care unit of the Vishnevsky military hospital in Moscow; on September 23, he died. The next day it became known that the cause of death was acute meningoencephalitis.

Grachev had a number of state awards. In addition to the Hero's Star and the Order "For Personal Courage", Grachev was awarded two Orders of Lenin, the Order of the Red Banner, the Red Star, "For Service to the Motherland in the Armed Forces of the USSR", as well as the Afghan Order of the Red Banner. He was a master of sports in skiing; headed the board of trustees of the CSKA football club.

Grachev was married and had two sons - Sergei and Valery. Sergei graduated from the Ryazan Higher Airborne Command School

Used materials

Alfred Koch, Peter Aven. Last interview with Pavel Grachev: “Fire at the White House, runaways!” - Forbes.ru, 16.10.2012

Pavel Sergeevich Grachev

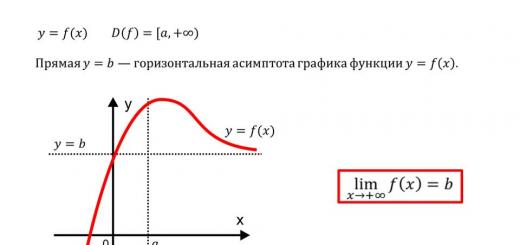

Russian Defense Minister Pavel Grachev speaks in the State Duma in 1994.

2nd Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation (from May 18, 1992 - June 17, 1996)

2nd Chairman of the Russian State Committee for Defense Issues

(during the period August 23, 1991 - June 23, 1992)

13th Commander of the USSR Airborne Forces

(during the period December 30, 1990 - August 31, 1991)

Party: CPSU (until 1991)

Education: Ryazan Higher Airborne Command School

Military Academy named after M. V. Frunze

Military Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the USSR

Profession: engineer for the operation of wheeled and tracked vehicles

Occupation: military man

Birth: January 1, 1948

Rvy village, Leninsky district, Tula region, RSFSR, USSR

Death: September 23, 2012

Pavel Sergeevich Grachev(January 1, 1948, Tula region - September 23, 2012, Moscow region, Russia) - Russian statesman and military leader, military leader, Hero of the Soviet Union (1988), former Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation (1992-1996), the first Russian army general (May 1992).

The youth and beginning of the career of Pavel Grachev

Was born Pavel Grachev(January 1, 1948 (according to Grachev himself - December 26, 1947) in the village of Rvy, Leninsky district of the Tula region in the family of a mechanic and a milkmaid. In 1964 he graduated from school. Since 1965 in the Soviet Army, he entered the Ryazan Higher Airborne command school, which he graduated with honors with a degree in “platoon commander of airborne troops” and “referent-translator from German” (1969), graduated as a lieutenant.

After graduating from college in 1969-1971, he served as commander of a reconnaissance platoon of a separate reconnaissance company of the 7th Guards Airborne Division in Kaunas, Lithuanian SSR. In 1971-1975 he was a platoon commander (until 1972), commander of a company of cadets at the Ryazan Higher Airborne Command School. From 1975 to 1978 - commander of the training parachute battalion of the 44th training airborne division.

Since 1978 Pavel Grachev was a student at the Military Academy named after. M. V. Frunze, which he graduated in 1981 with honors and after which he was sent to Afghanistan.

Since 1981 Pavel Grachev took part in military operations in Afghanistan: until 1982 - deputy commander, in 1982-1983 - commander of the 345th Guards Separate Parachute Regiment (as part of the Limited Contingent of Soviet Forces in Afghanistan). In 1983, as chief of staff - deputy commander of the 7th Guards Airborne Division, he was seconded to the territory of the USSR (Kaunas, Lithuanian SSR).

In 1984, he was promoted to colonel ahead of schedule. Upon returning to the DRA in 1985-1988, he was the commander of the 103rd Guards Airborne Division as part of the Limited Contingent of Soviet Forces. In total, he spent five years and three months in the country. May 5, 1988 “for performing combat missions with minimal casualties.” Major General Pavel Grachev was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union (Gold Star Medal No. 11573). After returning, he served in the airborne forces in various command positions.

In 1988-1990 Pavel Grachev at the Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the USSR. After graduation, he was appointed first deputy commander of the Airborne Forces. Since December 30, 1990 - Commander of the USSR Airborne Forces (position of Colonel General, Grachev at that time - Major General).

Pavel Gracheva

Participation in the State Emergency Committee

August 19, 1991 Grachev carried out the order of the State Emergency Committee to send troops to Moscow, ensured the arrival of the 106th Guards Airborne Division (Tula), which took under protection the strategically important objects of the capital. At the first stage, the State Emergency Committee acted in accordance with the instructions of the Minister of Defense of the USSR, Marshal D. T. Yazov: he prepared paratroopers together with KGB special forces and troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the storming of the building of the Supreme Council of the RSFSR.

Switching to Yeltsin's side

In the second half of August 20, Pavel Grachev together with Air Marshal E.I. Shaposhnikov, generals V.A. Achalov and B.V. Gromov, he expressed his negative opinion to the leaders of the State Emergency Committee about the plan to seize the Russian Parliament by force. Then he established contacts with the Russian leadership. By his order, tanks and personnel at the disposal of General A. Lebed were sent to the White House for its protection.

Subsequently Pavel Grachev received a promotion, on August 23, 1991, by decree of the President of the USSR, he was appointed First Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR - Chairman of the RSFSR State Committee on Defense Issues, and on October 29, 1991, by decree of the President of the RSFSR B.N. Yeltsin, he was appointed chairman of the RSFSR State Committee on Defense Issues.

By decision of the President of the USSR Pavel Grachev promoted to the rank of Colonel General and appointed First Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR (August - December 1991). From January to March 1992 - 1st Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the United Armed Forces of the CIS; was a supporter of the idea of creating a system of unified armed forces of the CIS. Pavel Grachev himself, answering a question from Trud newspaper correspondent Viktor Khlystun about the reasons for his appointment to the post of the first Minister of Defense of Russia after the collapse of the USSR, recalled:

- The first minister was not me, but Yeltsin. True, as a joke.

- How come?

- It all started in August 1991. Then I spoke out against the State Emergency Committee, in fact, I did not allow the capture of Boris Nikolaevich in the White House. At least that's what many thought. That’s probably why Yeltsin decided to thank me. I refused several times... I am a paratrooper, I fought in Afghanistan for five years. I have 647 skydives. Commander of the Airborne Forces. Many paratroopers dream of such a career. The new appointment did not appeal to me.

And what about Yeltsin?

- He thought about it, then he said: maybe you’re right that you’re not in a hurry. With that, he let me go, but the next day he called me and immediately suggested: let’s go to Gorbachev, there is an idea. We go into the office. No knocking. Boris Nikolaevich immediately: Mikhail Sergeevich, this is Grachev who saved you. I appointed him chairman of the Russian Defense Committee. How will you thank him? Gorbachev replied: I’m ready, I remember everything. Yeltsin immediately said: make him First Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR Shaposhnikov and give him the rank of Colonel General. Gorbachev immediately gave the order to write a decree.

Chairman of the Defense Committee - what kind of position?

She was kind of nominal. The Union was disintegrating before our eyes, and independent Russia did not yet exist. The Ministry of Defense of the USSR was headed by Shaposhnikov; in reality, he had the nuclear button. This continued until May 1992. Then Yeltsin called me again. By that time, the former republics of the USSR had armies and ministries. The President announced to me: I decided to create the Russian Ministry of Defense instead of a committee. Shaposhnikov will be in the USSR, and you will be in Russia. I appoint you as minister. I say - early, Boris Nikolaevich, appoint Shaposhnikov, he has experience, and make me his first deputy. That’s what they decided, but the next day, May 10, B.N. calls and says with some irony or something: well, Pavel Sergeevich, since you don’t agree, since you don’t want to help the president, then I myself will Minister of Defense And you are my deputy. So Yeltsin was the first Minister of Defense of Russia... A week later a call: how is the situation in the troops? The voice is tired. He often conveyed the mood with his voice and played. I answer, everything is fine. And here Yeltsin seems to complain: you know, I’m so tired of being a minister! Therefore, I signed a decree on your appointment.

- Interview “Pavel Grachev: “I was appointed responsible for the war,” “Trud” newspaper No. 048, 03/15/2001

Minister of Defense Pavel Grachev

Since April 3, 1992 - First Deputy Minister of Defense of Russia, responsible for interaction with the Main Command of the United Armed Forces of the CIS on issues of managing military formations under the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation.

Since May 7, 1992 Pavel Grachev- Acting Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation; on the same day, he, the first in Russia after the collapse of the USSR, was awarded the rank of army general. He became the first military leader in the modern history of Russia to be awarded this title. Since May 18, 1992 - Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation. The majority of the Ministry's senior leadership was formed from among generals whom he personally knew from their joint service in Afghanistan. He opposed the accelerated withdrawal of parts of Russian troops stationed outside the former USSR, in the Baltic states, Transcaucasia and some areas of Central Asia, justifying this by the fact that Russia does not yet have the resources necessary to solve the social and living problems of military personnel and members of their families. He tried to prevent the weakening of unity of command in the army, its politicization: he banned the All-Russian Officers' Assembly, the Independent Trade Union of Military Personnel and other politicized army organizations.

Until June 23, 1992 Pavel Grachev continued to hold the position of First Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the United Armed Forces of the CIS - Chairman of the State Committee of the Russian Federation on Defense Issues.

At first time Pavel Grachev was almost never criticized either by the President of Russia or by the communist opposition. He stated that “the army ... should not interfere in the resolution of internal political problems, no matter how acute they may be.”

However Pavel Grachev After his statements during the constitutional crisis in the country in the fall of 1992 about the support of the President by the army, the opposition’s attitude towards Grachev changed to sharply critical. In March 1993, Grachev, like other power ministers, clearly made it clear that he took the side of the President. During the unrest that began in Moscow on October 3, after some delay, he called troops into the city, who stormed the parliament building the next day after the tank shelling.

In May 1993, he was included in the working commission to finalize the draft of the new Constitution of Russia.

November 20, 1993 Pavel Grachev By presidential decree, he was appointed a member of the Russian Security Council.

November 30, 1994 Pavel Grachev By decree of the President of Russia, he was included in the Group for the Management of Actions for the Disarmament of Bandit Formations in Chechnya. In December 1994 - January 1995, from the headquarters in Mozdok, he personally led the military operations of the Russian army in the Chechen Republic. After the failure of several offensive operations in Grozny, he returned to Moscow. Since that time, in periodicals across the entire political spectrum, he has been sharply criticized for his virtual refusal to reform the army, for its failure to restore order in Chechnya and “for the policy pursued in the selfish interests of the top generals.”

He advocated a gradual reduction of the Armed Forces for the period until 1996, and believed that the army should be formed on a mixed basis with a subsequent transition to a contract basis. Pavel Grachev sent to the disposal of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief by presidential decree of June 17, 1996 as a result of the pre-election agreement between B. Yeltsin and A. Lebed.

Subsequent activities of Pavel Grachev

After leaving office, Pavel Grachev was at the disposal of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief for a long time (until the fall of 1997).

On December 18, 1997, in accordance with a special decree of the President of Russia, he took up the duties of advisor to the general director of the Rosvooruzheniye company. On April 27, 1998, he was appointed chief military adviser to the general director of the Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rosvooruzhenie - Rosoboronexport, officially taking up his duties.

In April 2000, he was elected president of the Regional Public Fund for Assistance and Assistance of the Airborne Forces “Airborne Forces - Combat Brotherhood”.

On April 25, 2007, the media, citing the chairman of the Union of Russian Paratroopers, Colonel General Vladislav Achalov, reported that Grachev was dismissed from the group of advisers to the general director of Rosoboronexport “in connection with organizational arrangements.” On the same day, the department’s press service clarified that, firstly, this happened on February 26, and secondly, it was due to the fact that from January 1, in accordance with the Federal Law “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Russia on issues of secondment and transfer of military personnel, as well as suspension of military service" the institution of secondment of military personnel to Rosoboronexport was abolished, after which several of them, including Army General Pavel Grachev, at his personal request, were presented for secondment for further military service at the disposal of Russian Defense Minister.

Since 2007 - chief advisor - head of a group of advisors to the general director of the Omsk production association "Radio Plant named after. A. S. Popova." In the same year he was transferred to the reserve.

Scandals and their investigations

According to opponents, Grachev was involved in the case of corruption in the Western State Guard in 1993-1994. Accusations were repeatedly brought against him in the Russian media for the illegal acquisition of imported Mercedes cars, registered with the help of the WGV command. None of these accusations were challenged by Pavel Sergeevich in court, but he was not brought to justice either.

Question: Do you remember when Pavel Grachev purchased two Mercedes-500s from Germany when he was Minister of Defense? Then, with the light hand of the Moskovsky Komsomolets newspaper, Grachev was nicknamed “Mercedes Pasha.” And the nickname stuck to him so much that many still remember it. Grachev, through Colonel General Matvey Burlakov, who commanded the troops that were being withdrawn from Germany, is unclear how he purchased those ill-fated cars. True, not for myself, but for official needs.

- Colonel Igor Konashenkov

Pavel Grachev owned the famous phrase, said before the start of the operation of federal troops in Chechnya, that it was possible to restore order in the republic in seventy-two hours with the help of one “fifty kopeck piece” - the 350th regiment of the 103rd Airborne Division. This phrase was uttered after the failure of the attempt to capture Grozny by the Chechen opposition with the support of Russian tank crews in November 1994.

Later he commented on a quote about one airborne regiment as follows:

Pavel Sergeevich, what about your infamous promise to take Grozny in two hours with the forces of one parachute regiment? - And I still don’t refuse it. Just listen to my entire statement. Otherwise, they snatched just one phrase from the context of a big speech - and let’s exaggerate. The point was that if you fought according to all the rules of military science: with the unlimited use of aviation, artillery, and missile forces, then the remnants of the surviving gangs could really be destroyed in a short time by one parachute regiment. And I really could do it, but then my hands were tied.

In January 1995 Grachev at a press conference after the “New Year’s assault” on Grozny, he said: “These eighteen-year-old boys died for Russia, and they died with a smile. They need to erect monuments, but they are defamed. This one... This peacemaker-deputy... Kovalev. Yes, he has nowhere to put marks, nowhere to put marks. This is an enemy of Russia, this is a traitor to Russia. And they meet him there, everywhere. This Yushenkov, this bastard! In other words, it cannot be said, he criticizes the army, which gave him an education, gave him a rank. Unfortunately, in accordance with the resolution, he is also a colonel in the Russian army. And he, this bastard, protects those scoundrels who want to ruin the country.”

Personality assessments of Pavel Grachev

Gennady Troshev, Colonel General, Hero of Russia in his memoirs “My War. Chechen Diary of a Trench General" gave its own, multifaceted assessment of Grachev, devoting space to both the negative and positive aspects of his activities:

Grachev is an experienced warrior, he held all command posts, he smashed the “spirits” in Afghanistan, unlike most of us who had not yet gained combat experience, and from him we expected some non-standard solutions, original approaches, and, in the end, useful, "educational" criticism.

But, alas, it’s as if he hid his Afghan experience in the museum’s storeroom, we didn’t observe any kind of internal burning, combat passion in Grachev... Place the old preference player next to the table where the game is being played - he will be exhausted with the desire to join in the fight for the purchase . And here there is some kind of indifference, even detachment.

... I’m afraid that this confession of mine will disappoint many, but I continue to argue that largely thanks to Grachev, the army did not crumble into dust in the early 90s, like many others did in that period. The military know and remember that it was Pavel Sergeevich who came up with a lot of “tricks” to increase the pay of officers: an allowance for “strain”, then pension “surcharges”, then payment for “secrecy”, etc. Isn’t it his It is his merit that he did not allow the army to be destroyed under the guise of military reform, as the young reformers demanded. If he had conceded on the main thing then, Russia would not have an army today, just as it, by and large, does not have an economy. - Gennady Troshev. "My war. Chechen diary of a trench general", memoirs, book

Hero of Russia, Army General Pyotr Deinekin: “With Pavel Grachev, we dealt with the withdrawal of troops from the former republics of the USSR, and the construction of the Russian army, and reforms, and the first Chechen war. Many unfair words have been published and said about him in the so-called “independent” press and electronic media, but, in my opinion, he was the strongest of the defense ministers under whose leadership I had the opportunity to serve. He is remembered as a decent person and a brave paratrooper, who made most of his parachute jumps while testing new equipment. I sincerely respect him...” (“Donetsk Communication Resource”, 05/19/2008).

Army General Rodionov, Igor Nikolaevich: “Grachev in my 40th Army was a good commander of the Airborne Division. He never rose above this level. He became a minister only because he defected to Yeltsin’s side in time.”

Illness and death

On the night of September 12, 2012, Grachev was hospitalized in serious condition in the 50th cardiac intensive care unit of the Central Military Clinical Hospital named after. Vishnevsky in Krasnogorsk near Moscow. According to news agencies and the press, Grachev suffered a severe hypertensive crisis with cerebral manifestations, but poisoning could not be ruled out.

He died on September 23, 2012 in the Vishnevsky Military Clinical Hospital.

Personal Information

From his youth he was fond of sports (he loved football, volleyball and tennis), in 1968 he became a master of sports of the USSR in cross-country skiing.

Was married, widow - Gracheva Lyubov Alekseevna. Had two sons. The eldest, Sergei b. 1970, officer of the Russian Armed Forces, graduated from the same Airborne Forces School as his father; Jr., Valery, b. 1975 - studied at the Security Academy of the Russian Federation.

Awards and titles

Hero of the Soviet Union (May 1988)

Two Orders of Lenin

Order of the Red Banner

Order of the Red Star

Order "For Service to the Motherland in the Armed Forces of the USSR" III degree

Order “For Personal Courage” (October 1993, “for the courage and courage shown in suppressing the armed coup attempt on October 3-4, 1993”)

Order of the Badge of Honor

Order of the Red Banner (Afghanistan)

Honorary Citizen of Yerevan (1999)

Military service of Pavel Grachev

Pavel Sergeevich Grachev was the most famous and scandalous Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation. He held this post from 1992 to 1996. Coming from a simple worker-peasant family (father is a mechanic, mother is a milkmaid), he went through a difficult path to the very pinnacle of power and did a lot to ensure that he would be remembered for a long time in this position.

Achievement list

Pavel Grachev was born in the Tula region in 1948. After school I went to the Airborne Forces School in Ryazan. Upon graduation, he served in a reconnaissance company in Kaunas (Lithuania), then on the territory of the Russian Federation. In 1981 he graduated from the Frunze Military Academy in absentia. Served in Afghanistan. For his service he was awarded the Gold Hero Star. Then he served in various command positions.

Since the end of 1990, with the rank of major general, he became commander of the USSR Airborne Forces. After 2 months, he was awarded the rank of lieutenant general, which was more appropriate for his position. During his military service, Grachev proved himself only positively. He was repeatedly wounded, shell-shocked, participated in testing new equipment, made over 600 parachute jumps, etc.

Grachev's actions during the putsch

During the August events in Moscow in 1991, Pavel Grachev initially followed the orders of the State Emergency Committee. Under his command, the 106th Airborne Division entered the capital and took custody of the main facilities. This happened on August 19. After 2 days, Grachev sharply changed his opinion about the events taking place, expressed his disagreement with the forceful methods of seizing power to the State Emergency Committee and went over to the side of the president.

He gave the order to use heavy armored vehicles and personnel under the command of Alexander Lebed “to protect” the White House. Later, during the investigation into the State Emergency Committee case, Grachev stated that he did not intend to give the order to storm the White House. On August 23, the president appointed Pavel Grachev as first deputy minister of defense. At the same time, the lieutenant general was promoted to rank. From that moment on, his career quickly took off.

As minister

In May 1992, Pavel Sergeevich became the Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation and received the rank of army general. During an interview with a correspondent of the Trud newspaper, Grachev admitted that he did not consider himself worthy of such a high post (he had, they say, not enough experience). But Yeltsin convinced him. At his new post, Pavel Grachev formed the entire cabinet, selecting people from those who served in Afghanistan.

The minister opposed the rapid withdrawal of troops from the Baltic states, Central Asia and Transcaucasia, rightly believing that it was first necessary to create conditions for military personnel in their homeland, and then transfer them to a new duty station. Grachev sought to strengthen the Russian army by prohibiting the formation of politicized organizations within its ranks.

During his command there were also contradictory, even strange steps. For example, Grachev ordered that almost half of the weapons of the Russian Army be transferred to the disposal of Dudayev’s militants. The minister explained this by saying that it was not possible to remove weapons from the territories captured by the Dudayevites. A couple of years later, separatists fired at Russian soldiers from these machine guns.

Relation to Grachev

At first, the personality and actions of Pavel Sergeevich did not cause much debate. In 1993, the opposition's attitude towards the minister changed dramatically. After the October riots in Moscow, Grachev clearly demonstrated that he was ready to raise the army against the civilian population. Shortly before this, he stated the exact opposite: the army should not interfere in resolving internal political conflicts.

Grachev opposed the entry of troops into Chechnya. For this he was criticized by both Chernomyrdin and Yeltsin himself. At the same time, the minister personally led the military operations in Chechnya, and rather unsuccessfully. After several crushing defeats he returned to Moscow.

Grachev was subjected to sharp criticism for many of his actions and statements. For example, at the beginning of the Chechen War, he threatened to restore order in Chechnya in two hours with one parachute regiment, and when asked how much time he needed to prepare, he answered: “Three days.”

In January 1995, Grachev said that “eighteen-year-old boys” in Chechnya are dying “with a smile,” speaking of dead Russian soldiers.

In 1993, in order to relieve himself of responsibility, he asked Yeltsin for written permission if necessary to open fire on the White House. After the Grozny “successes,” Grachev began to advocate a gradual reduction of the army and its transfer to a contract basis.

Scandals

In 1997, Pavel Grachev was appointed advisor to the general director of Rosvooruzhenie. Next year - advisor to the general director of Rosoboronexport. In 2007, Grachev was dismissed from his last post due to the “abolition” of this and some other positions.

One of the most high-profile scandals was the case of corruption in the top military leadership of units located in Germany. This was in the early 90s. Alexander Lebed stated that Grachev was involved in this case and, using ill-gotten money, purchased several Mercedes abroad. Grachev was not brought to justice in this case, but he did not dispute his guilt in any way.

Yeltsin pinned his main crimes on the ex-Minister of Defense

Yeltsin pinned his main crimes on the ex-Minister of Defense

This week will mark 9 days since the death of the Hero of the Soviet Union, who played a special role in the collapse of his Motherland. Pavel GRACHEV became an enemy for many officers already in the days of the August 1991 coup. And the country greeted the news of his death with the words: “Mercedes Pasha gave a damn!” He was accused of double betrayal; they said that with his stupidity, mediocrity and martinetry, he ruined thousands of soldiers' lives during the first Chechen campaign. How could a hero of the Afghan war fall so low?

Even on the days of the funeral of the ex-Minister of Defense of Russia Pavel Gracheva, when “about the dead - either the truth or nothing,” passions were boiling on the Internet: “Not an officer, not a soldier, and not a minister. Banal Judas. In August 1991, he betrayed the USSR and his oath, siding with Yeltsin. I think the young soldiers who were sent to Chechnya after a month of training had already warmly greeted Uncle Pasha,” “After Black October 1993, when Grachev betrayed Russia and its constitution, siding with EBN and becoming his punisher, his soul was forever in the clutches of Satan."

Everything seems clear. But here are the words of a man with a reputation as an unconditionally honest, courageous, patriot of Russia - the President of Ingushetia Yunus-Bek Evkurova: “Pavel Sergeevich Grachev, a real Hero, a man who dedicated his life to selfless service and selfless defense of our Great Motherland, has passed away, and his life can rightfully serve as an example of patriotism, fortitude, fidelity to duty, and officer’s honor. As a true general and officer, he always faithfully served his Motherland, and loyalty to his country is the highest value.”

Where is the truth? But the truth is that no one to this day knows exactly what happened in the fateful days of August 1991. As well as what forces, in addition to the army, special services, police, KGB Alpha and Israeli Beitarites, were involved in the square near the White House in October 1993, where they crushed the ordinary people who came out with tanks and shot from the roofs of the American embassy to protect deputies who were opponents of Yeltsin.

Eggs in different baskets

It is clear today that in 1991 we chose between two traitors - Gorbachev and Yeltsin. And then the future “Tsar Boris” presented himself as a guardian of the aspirations of the people and did not mention the collapse of the USSR. According to the historian Alexandra Shevyakina, author of the book “Contract Murder of the USSR,” strategists from the Rand Corporation, an American private company that received an order to create a program to liquidate the USSR, assigned Grachev the unsightly role of a conspirator. The Randists placed their bets on the elite, primarily the Republican elite, the KGB and the “fifth column” and on brainwashing with the help of the “democratic” press.

One of the “washers,” the future mayor of Moscow Gavriil Popov, recalled that the putsch project had two main options: with and without Gorbachev’s participation. “When I was shown its possible scenarios and our possible counteractions long before the coup, my eyes widened. What was there: resistance in the White House, and near Moscow, and travel to St. Petersburg or Svedlovsk to fight from there, and a reserve government in the Baltic states and even abroad. And how many proposals there were about scenarios for the coup itself! And the “Algerian option” is a revolt of a group of troops in one of the republics. Revolt of the Russian population. Etc. and so on. And it became increasingly clear that everything would depend on the role of Gorbachev himself: the putsch would either be with his blessing, or under the flag of his ignorance, or with his disagreement or even against him. Of all the options, the State Emergency Committee chose the one that we could only dream of - not just against Gorbachev, but also with his isolation.”

But who showed Popov these options? Three years later, this was declassified by the Chairman of the KGB of the USSR Vladimir Kryuchkov: “Popov had contacts with the Secretary of State Baker, with its expert group, was accepted by specialists from the CIA." The composition of the State Emergency Committee was not formed by its high-ranking participants themselves, but the exchange of information between them was arranged so that they were all confident that they were acting on their own initiative and for the benefit of the USSR. How did Airborne Forces commander Pavel Grachev get into this company of top officials of the KGB, party, and ministers? He entered the game on the orders of the marshal Dmitry Yazov. The Great Patriotic War veteran was an ardent opponent of both Gorbachev’s idea of army reduction and Yeltsin’s plans to transform the Soviet republics into sovereign states. He ordered his favorite to participate in the development of a putsch scenario, allegedly carried out by the KGB in order to prevent the collapse of the USSR. The KGB treated Grachev subtly, telling him that in a real situation he would figure out for himself whose commands - Yazov's, Gorbachev's or Yeltsin's - he should carry out.

Of the traitor Gorbachev and Yeltsin, whom the people then idolized, Grachev chose the second. But he could not refuse to carry out Yazov’s orders, although this could strengthen Gorbachev’s position. And he played his own game, deciding to “keep his eggs in different baskets.” At meetings with Yazov, he proposed drastic anti-Yeltsin measures, and then reported the reaction to Yeltsin.

During the putsch, Grachev brought tanks into Moscow. The people were shocked. And he ran to the White House, ready to lie down on the asphalt just to protect Yeltsin. People asked 19-year-old tankers: “Who are you for?” They just shrugged their shoulders. Grachev had no intention of firing cannons at the people in 1991. The calculation was simple: if the Emergency Committee gains the upper hand, he can tell Yeltsin, they say, I warned you, and report to Yazov that I was the first to surround the nest of resistance. If Yeltsin wins, I will be the first to come to your aid. This double-dealing is what the officers who remained faithful to the oath call Grachev’s first betrayal.

Pasha Mercedes

I share the grief of mothers and fathers whose sons died in Chechnya for nefarious interests Berezovsky and future oil oligarchs. But still, I dare to remind you that we know about all of Grachev’s atrocities only from the press and television programs, engaged by the same “fugitive oligarch” who had direct contacts with the bandits and could influence Yeltsin.

Grachev himself, sent into disgraceful retirement by Yeltsin, left the Ministry of Defense with dignity and did not try to whitewash himself or cheat others. General Gennady Troshev claims that Grachev tried with all his might to convince Yeltsin not to send troops into Chechnya, or at least to postpone their entry until the spring in order to have time to prepare the army. I even tried to negotiate with Dudayev. It didn't work out. The result was Yeltsin’s decree and the first assault on Grozny on January 1, Grachev’s birthday. The Minister of Defense also protested against the entry into Grozny of an armored column on November 26, 1996, which was virtually doomed to be burned. The press indiscriminately blamed Grachev personally for the tragedy, but later it turned out that this “brilliant” operation was organized by the then director of the FSK Stepashin and the head of the Moscow FSB Directorate Savostyanov, who oversaw the elimination of the Dudayev regime. Opponents accused Grachev of illegally acquiring two Mercedes, for which he was nicknamed “Mercedes Pasha.” But it turned out that he purchased them legally for the Ministry of Defense, and the scandal broke out because the minister did not understand why he should pay customs if the car was in public service.

Lovely affairs

Later, the prosecutor's office looked for Grachev's dachas in Portugal and Cyprus, but did not find them. But Express Gazeta was the first to find the dacha Elena Agapova- the press secretary of the Ministry of Defense, a sexy woman who was so devoted to the Minister of Defense that the officers had no doubt: they were having an affair. The dacha in the general's village was not appropriate for her rank, which aroused the burning envy of high-ranking military personnel. Because of her, another scandal broke out.

Grachev spoke about his views on marriage and adultery in an interview with Sobesednik in February of this year: “I don’t cheat on my wife Lyubov Alekseevna. Although I hate the word “treason”. To cheat means to leave your family and go to another woman. I don't admit this. But if you met a girl, you liked her, she liked you too, you have mutual sympathy. What kind of betrayal is this? We rested, took a walk, and then she returned to her place, and you returned to your place. This is not treason, but a temporary respite between fights. Lyubov Alekseevna and I got married when I was 21 years old. 43 years have passed since then. She says: “I know that you were walking away from me.” I ask: “And how did you feel about this?” “Before,” the wife answers, “I was indignant. And then I thought: okay, I’m wealthy, I have a good house, great children, grandchildren, you’re with me all the time!” And she's right. You see, if a man marries early, at some point he will still be drawn to another woman, to try, so to speak, whether she is better or worse than his wife. So women need to either accept it or leave. Grachev's two sons - Sergei and Valery - followed in their father's footsteps, but did not wear the shoulder straps for long. Sergei, a graduate of the airborne school, went into business and left for the UAE. His wife and daughter Natasha refused to go with him, and they divorced. Now Sergei has a new life partner. The ex-Minister of Defense admitted that the main love of his life is his grandson Pasha, a gift from his youngest son, a former student at the FSB Academy, who now heads a recycling company. When the grandfather found out that his grandson had been given his name, he shouted into the telephone receiver to all his friends: “Know that Pavel Grachev will die, but Pavel Grachev will still remain. My enemies especially need to know this so that they never forget the name Grachev!”

Quote

Mikhail POLTORANIN, politician and publicist:

- Russian Defense Minister Pavel Grachev reported in a message to US Defense Secretary Richard Cheney how he would eliminate heavy missiles, as well as their production and fill deep silos with concrete, replacing the hated "Satan" with a small number of monoblock farts open to fire - "Topols", not capable of breaking through to the shores of the United States... In a response letter, Cheney patted Grachev on the shoulder for his efforts: “I cannot help but recognize the central role that you personally played in achieving the historic agreement on START-2. Please accept my personal congratulations on this.” And Dzhokhar Dudayev and his bashi-bazouks also praised Grachev very much. For pacifism, for reluctance to use weapons in the interests of Russia. To fight the Russian people, Pavel Sergeevich, in agreement with Yeltsin, transferred to the Chechen rebels two Luna tactical missile systems, ten Strela-10 anti-aircraft systems, 108 units of armored vehicles, including 42 tanks, 153 units of artillery and mortars, including 42 BM rocket launchers -21 "Grad", 590 units of modern anti-tank weapons and much more.What is the role of the figure of Pavel Grachev in the modern history of Russia?

Vladimir Kara-Murza

Vladimir Kara-Murza: On Sunday, at the age of 65, Pavel Sergeevich Grachev, army general, former Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation, died. The cause of death of the ex-minister of defense was acute meningoencephalitis. Pavel Grachev was 64 years old. The future Minister of Defense was born into the family of a mechanic and a milkmaid in the village of Rva, Tula Region, served in the Airborne Forces, then studied at the Frunze Military Academy. In 1981 he was sent to Afghanistan, where he served intermittently for more than 5 years. After returning from Afghanistan in 1998, he worked at the Academy of the General Staff of the USSR Armed Forces. In 1990 he was appointed deputy commander of the Airborne Forces. Pavel Grachev served as Minister of Defense from 92 to 96 and throughout this time was criticized by almost all political forces. In the period from December 94 to January 95, the head of the military department personally supervised the course of hostilities in Chechnya. Grachev promised to restore order in Chechnya in two days with one airborne regiment. On June 17, 1996, he was dismissed from the post of Minister of Defense. From December 18, 97 to April 98, military adviser to the general director of Rosvooruzhenie.

In our program we talk about the role of the figure of Pavel Grachev in the modern history of Russia with Viktor Barants, columnist for Komsomolskaya Pravda, former press secretary of the Ministry of Defense, and Igor Korotchenko, editor-in-chief of the magazine National Defense. When did you meet Pavel Sergeevich, and what human qualities did he have that distinguished him?

Victor Baranets: My first acquaintance was in Afghanistan at the very height of the war - it was 1986. At that time, Pavel Sergeevich commanded the 103rd Airborne Division, and there were heavy battles. I then came on a business trip, and, of course, at first I was alarmed by such a respectful and loving attitude of soldiers and officers towards their commander. Then stories began about how Pavel did not sit in a warm dugout when sometimes he had to take villages and mountains, that he was wounded. In a personal acquaintance, Grachev stuck out his tongue to me: “You see, a piece of my tongue was pinched off by a splinter.” Then I witnessed a most curious detail. At the Kabul airfield, the cargo plane was completely filled with clothes; they sent gifts to Moscow generals and colonels, as always, and the officers sent their clothes. Back then, I remember, it was very fashionable, it was an officer’s dream to own a Panasonic, officers carried jeans, jackets and other things. They brought in a dozen wounded officers, and the arrogant commander of the ship came out, apparently providing for the Moscow elite, and said: I have nowhere to be wounded, you see - everything is packed. Then Grachev jumped up and threw these boxes almost to Amin’s palace, scattered everything, said: “These guys of mine should be immediately sent to a hospital in Kabul.” This is how my acquaintance was. But I was lucky, in those days Pavel Sergeevich was awarded the rank of major general, he invited me to this party. And I remember with what officer rage and sincerity this officer’s feast sang the song “Our battle commander, we will all follow you.” I had the feeling that there was no falsehood. Indeed, he became a major general, and even the soldiers lovingly called him Pasha behind his back. This was a man who was respected, this was a man who did not hide behind the backs of the soldiers, as the famous song says. This was truly a commander, a Soviet commander of very good airborne training.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: How do you assess the reform of the armed forces, which began under Pavel Sergeevich as Minister of Defense?

Igor Korotchenko: First of all, it should be noted that Grachev ended up in the post of Russian Defense Minister by chance, by the will of fate. Shortly before the August events of 1991, he received Boris Yeltsin, they steamed together and drank several glasses of vodka, in fact, a close acquaintance took place between the Russian leader and one of the then promising Soviet airborne generals. And in fact, Grachev’s behavior during the August putsch and then his close acquaintance with Yeltsin, in fact, played the role of a springboard, thanks to which Grachev, with the outlook and mentality of an airborne division commander, suddenly found himself in the chair of the head of the Russian Ministry of Defense. He became the first Minister of Defense of the new Russia, of course, the weight of all those problems fell on his shoulders, which I still remember very well and which accompanied not only the process of the collapse of the Soviet armed forces, the Soviet army and navy, but also the legal formation Russian army.

First of all, I believe that Grachev’s great merit is that he was able to maintain centralized control over nuclear weapons, which were located not only on the territory of the Russian Federation but also on the territory of several former Soviet Union republics. Let me remind you that at the beginning of 1992, many post-Soviet leaders of these republics wanted nuclear status for their newly proclaimed states. And I believe that Grachev’s enormous merit is that nuclear weapons were eventually, after long and difficult negotiations, removed to Russian territory. At the same time, not a single nuclear warhead fell into the wrong hands, which was extremely important in those conditions.

Grachev did a lot to prevent the armed forces from falling apart. We remember that there were different candidates for the post of Minister of Defense of Russia; I remember that Galina Starovoitova and a number of other prominent democrats and liberals from Boris Yeltsin’s entourage were even nominated for this position. I think that if one of them had taken the post of the first civilian minister then in the new Russia, then, probably, the armed forces would have completely lost control and controllability and they would have suffered an even sadder fate than the one that was in store for them.

But of course, among the negative aspects of Grachev as Minister of Defense, I would note the first thing that he allowed the army to be drawn into the tragic events of October 93, when, succumbing to pressure from Yeltsin, he dragged the army into internal political squabbles, which led to a tank assault and attack airborne units of the building of the Supreme Council of Russia, and the unpreparedness of the army for combat operations in Chechnya. Probably, here the reproaches against Grachev are minimal, because starting from the late 20s and early 30s, in fact, our army had no more experience in suppressing an internal armed rebellion. The last such actions were to combat the Basmachism. And of course, I also wanted to mention as a drawback that Grachev agreed to a very short, I would say, very cruel time frame for the withdrawal of our groups from the countries of Eastern Europe, primarily from the Western Group of Forces, from Germany and from other countries of the former Warsaw Pact . As a result, the divisions were transported to an open field, where there was nothing for their deployment, arrangement, or housing. And today these once famous connections and parts practically no longer exist.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: Do you agree that Pavel Sergeevich dragged the army into the events of 1993?

Viktor Baranets: Let me start by making a short statement as an officer who also took the oath. I try not to accept these conversations about what Pavel Sergeevich brought in. Pavel Grachev is subordinate to the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Armed Forces, whose decrees and orders had to be carried out. Grachev, as Minister of Defense, as Yeltsin’s subordinate, had little choice: either, as an officer, carry out the order, without discussing it, in my opinion, no one canceled the oath, decrees and charters, or submit his resignation. Grachev chose the second, such is his fate. And the biggest tragedy of Pavel Sergeevich, in my opinion, is that he became a loyal soldier of the Yeltsin regime. He took upon himself this black cross and carried it the way he carried it. Here it is enough to recall that conversation, the ferocious conversation between Yeltsin and Grachev, when he ordered to shoot at the White House. And there were many witnesses that night when Pavel Sergeevich did not express enthusiasm for this instruction. There are many witnesses to what happened that night. Already leaving the office, upset, pale, gnashing his teeth, Yeltsin saw that Grachev was hesitating, but Grachev at the last moment turned to Yeltsin, said: “Boris Nikolaevich,” or rather, he turned: “Comrade Supreme Commander-in-Chief, I ask you to still send me written order." And then Yeltsin, gnashing his teeth, said: “Okay, I’ll send it to you.” This is a small detail, but it says that Grachev still had responsibility, conscience, and understanding of the dirty tragedy into which Yeltsin dragged him.

Now about the Chechen war. Now, of course, many, very many, especially the parents of the dead soldiers, swear and curse Grachev that he dragged the army into a civil war, essentially a war on the territory of his own state. But here the question arises: what, Grachev himself pulled troops there, he himself decided to fight with Dudayev, with whom he met twice on the eve of the war and persuaded him not to fight. Dudayev had already agreed, because all that remained was to sit down for negotiations, which Yeltsin did not want. He did not want to sit down with some shepherd, as he said, at the gilded tables of the Kremlin. And here again came the black fatal moment of truth for Grachev, he had to carry out or not carry out. He, as a soldier, as an officer, as a general, decided to act like an officer, to carry out, no matter what the cost. Yes, the army was not prepared, but I don’t understand the reproaches to Grachev that too many soldiers died. I don’t know wars in which there would be no casualties of soldiers and officers. On the other hand, the army was really prepared for that operation, and let’s say in our own words - a civil war against its own population, because Chechnya was and remains a Russian republic, it was Russia, and Napoleon would not have been prepared for such a war.

Remember, after all, it was 1994, we were really just pulling troops out of Europe, fled, we didn’t know where to place them, we had only just removed weapons from the trains, we had few units that were ready to fight with our own people . Now, of course, from the height of the present time, to say that he acted wrongly, fought incorrectly. Yes, of course, Pavel Sergeevich made mistakes. And who didn't have them? I believe that Grachev in our memory, in the history of Russia, by the way, he was the 40th Minister of Defense and, you know, in the long list of ministers there was no such Minister of Defense who would conduct his first military operation in the center of the state capital against their own parliament. Grachev, of course, can be blamed endlessly, but there are many soldiers who, for the sake of objectivity, are ready not only to put black crosses on the memory of Grachev, but also to say thank you to him.

Under Grachev, the army was in a very difficult situation, when salaries were not paid for 5-6 months, when officers' wives cooked quinoa soup. And yet, Grachev tried to support the army. Let me tell you this episode. As of February 23, we no longer received salaries from the Ministry of Defense and the General Staff; we were only given black bread and sprat in tomato sauce. And Grachev was ashamed in front of the officers, he took and ordered to take out from the storerooms all the commander’s watches that were in his ministerial storeroom, and he distributed them to us officers on February 23, and said with a bitter smile: everything I can. We donated these watches to one major and sent him to Arbat, where they sold like hot cakes to foreign citizens at the Kazansky station. And we thanked Grachev that even on our holy holiday he did not forget, he gave us this way to celebrate our sacred holiday, Soviet Army Day, although then, however, the army was already called Russian.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: We are listening to a question from Muscovite Marina.

Listener: Hello. You know, we are also witnesses of all these times. I believe that the people with whom I communicate believe that Yeltsin was lucky with Chubais, lucky with Gaidar, but very unlucky with Comrade Grachev. I can’t imagine that Yeltsin came up with the idea to roll out the tank himself. And Grachev - this is according to his character. What did he say about Chechnya and who started the nonsense that we would take a regiment there? It was also Grachev. Well, what a life, such a life. And about the watch, because we also lived at that time and we did not have a commander’s watch. We cleaned the streets, engineers and candidates, and we don’t sit and cry. Of course, a man died, he was not a traitor, but Yeltsin was unlucky with him.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: Do you think there is a share of Pavel Sergeevich’s personal guilt in the number of victims in Chechnya?

Igor Korotchenko: You know, it’s hard to blame a person who is no longer there. But it can be said quite clearly that a number of miscalculations were obviously made when planning the operation in the Chechen Republic. First of all, this concerned intelligence issues, this concerned issues of weapons and equipment of troops. In principle, the troops were largely unprepared for what awaited them there. Therefore, I believe that the unsuccessful New Year’s assault on Grozny in the first Chechen campaign, a certain share of Grachev’s guilt here, is completely obvious. In general, I can note that in terms of his personal qualities, Grachev was an honest person. Those accusations, we remember how the press furiously kicked him, not all, but part of the press, with which he did not have a good relationship as Minister of Defense and who bullied the minister, accused him of a number of corruption crimes and misdemeanors. From the perspective of the past tense, it should be noted that Grachev turned out to be an honest man, nothing stuck to his hands, and this does him honor as a general, as a leader.

At the same time, it should be noted that, while serving as Minister of Defense, he took approximately the same position regarding the instructions that Yeltsin gave him, approximately the same position that Marshal Yazov took in relation to Gorbachev. He took the lead, not trying to counteract, as Marshal Akhrameev did in his time, hasty and ill-considered decisions. It is quite obvious that there was no need for a sharp withdrawal of Russian army groups that found themselves under Russian jurisdiction from the territory of the countries of the former Warsaw Pact. Germany, in principle, was generally ready for the Russian Western Group of Forces to remain there for almost ten years, while they were ready to pay the necessary money to create the actual social infrastructure for the withdrawn troops on Russian territory. However, the pressure of Kozyrev and other Western-oriented people on Yeltsin led to the fact that Grachev, in the future, receiving Yeltsin’s instructions about the accelerated withdrawal of troops, still acted largely to the detriment of the armed forces. I repeat once again, where are the groups, because in Germany we had several tank armies that inspired the horror of NATO, because in terms of their combat equipment, in terms of combat coherence, they were the most powerful strike groupings of troops, today they are not there, they have disappeared into the Russian black soils, where Yeltsin and Grachev brought them out. Therefore, I think that there were both positive and negative aspects in the activities of Pavel Sergeevich Grachev. Although in general I must note that there were much more positive things in his activities than negative ones. And most importantly, assessing him from the perspective of the past years, the most important conclusion is that Grachev was an honest man, nothing stuck to his hands. Although, of course, we understand the scale of the corruption crimes that took place in our country in the 90s, and the fact that Grachev turned out to be clean does honor to his memory.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: What was the relationship between Pavel Sergeevich and Alexander Ivanovich Lebed?

Viktor Baranets: Before I answer your question, about the opinion of our respected radio listener, who said that Yeltsin was unlucky with Grachev. My answer will be that Yeltsin was terribly lucky with Grachev, if only because in October 93 Yeltsin would have been hanging on a lamppost or on a road booth, like Najibullah, if Grachev had not brought out the tanks and shot the parliament - such is the salty truth of life. Yeltsin was lucky with Grachev only because this damned civil war from Chechnya did not crawl to Moscow, dear radio listener, where the guts of our children, grandchildren, fathers could dangle on telegraph wires. I was very lucky here. Yes, the Minister of Defense was not innocent, yes, and the army was poorly prepared, it was only two years old, the commanders had not yet been fired upon, they had no experience in killing their own fellow citizens in Chechnya, but that’s how it turned out.

Now of course it's easy to say. Now about Lebed. The relationship between Lebed and Grachev was very different. We must not forget that they served together, that they studied at the same school, that for a long time they lived parallel lives in the airborne forces, that they were almost neighbors as division commanders. At first, their life was normal and so was their service. But the situation changed dramatically when Grachev became Minister of Defense, and Lebed was often used as a kind of fire extinguisher, who was thrown into Transnistria, you know, and Lebed was dissatisfied with many, many things. Lebed was more aligned with the opposition wing of the Russian officers, the national patriots, one might say. And in general, by 1996, Lebed had become the figure who even to a certain extent began to dictate to the Kremlin who to appoint and who to remove from the post of Minister of Defense. You remember, Yeltsin, whose rating in 1996 was sliding to the crisis level of zero, he offered Lebed the position of Secretary of the Security Council with only one condition, which was set for him by Alexander Ivanovich. He said: if you remove Grachev and appoint Rodionov, I will agree. And thus we can say that the former colleague also had a hand in pushing Yeltsin to throw “the best minister of all times and peoples” off this military-political ship of Russia.

Well, we have two outstanding figures in the history of the modern Russian army, yes, outstanding, I say this without any reproach. These were individual people, these were people who would be very remembered by the army for their extraordinary actions and their dislike for the regime, as Lebed openly demonstrated, and their devotion to the regime, as Pavel Sergeevich Grachev demonstrated. But you see, you can’t reason here in some kind of lyrical-dramatic way, reason while sitting on some drunken heap. I repeat once again: the Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation Grachev was a subordinate figure, he was a subordinate of the president. I repeat once again, he had little choice: either click the heels of his patent leather shoes and carry out the orders that Yeltsin gave, or put the report on the president’s desk and tell him: Comrade Supreme Commander-in-Chief, I don’t want to participate in your dirty game. The whole tragedy of Grachev is that he supported Yeltsin, made this choice, which forced him to carry out orders and which were deeply disgusting to Grachev. I speak as a person who was closely acquainted with Pavel Sergeevich Grachev.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: In your opinion, has Pavel Grachev’s reputation suffered from the suspicion of involvement in the murder of Dmitry Kholodov?

Igor Korotchenko: It was a whole campaign that was launched against the Minister of Defense, it took on the character of fierce persecution. Of course, Grachev did not give any orders to kill Kholodov. Another thing is that the Ministry of Defense was looking for an opportunity to informationally neutralize the flow of negativity that poured out both on the military department and personally on the Minister of Defense. Of course, Grachev was very worried about unfair reproaches and direct insults. But, nevertheless, of course, this dealt a blow to both the reputation of the military department and Grachev personally. Because people, far from understanding the real processes that took place in the military department, were inclined to believe hasty journalistic statements and pseudo-investigations regarding corruption in the Western Group of Forces, Grachev’s connection with the facts of this corruption, and so on. Although I would like to emphasize once again that during the withdrawal of troop groups from East Germany, every effort was made to ensure that all this happened within the legal framework and was not accompanied by the excesses that occurred in other areas of Russian reality and politics.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: We are listening to a question from Muscovite Oleg.

Listener: Good evening. I wanted to say a few words about Grachev. The fact that he threw tanks into Grozny in Chechnya, could a normal person do that? Is it really not clear that they will all burn them there? So much for his competence. Pasha-“Mercedes”, why was he called? The fact that he removed nuclear weapons from the republics is not his merit, it is the merit of both Russian and Western politicians who set the conditions; it was beneficial for them, naturally. What does Grachev have to do with this?

Vladimir Kara-Murza: Was it Pavel Sergeevich’s idea - the November tank attack on Grozny?

Viktor Baranets: You know, for a long time, like Igor Korotchenko, I served in the Ministry of Defense, and for almost 33 years in the army I was always irritated by the ridiculous beautiful phrase that the commander is responsible for everything and the Minister of Defense is also supposedly responsible for everything. Yes, of course, Grachev was reported on the plan of the operation in Grozny, but the direct executors were those people who brought tanks into the necks of the Grozny streets, where there were very dense ambushes, where one brigade was completely killed from Maikop. Yes, it was a tragedy, it was one of Grachev’s worst failures in his ministerial career. But nevertheless, if we are objective, then we still need to place part of the blame, although it may sound defiant and cynical, to still place part of the blame for that tragedy on the shoulders of those commanders who sat, figuratively speaking, on the armor and who They planned the operation directly in the situation that existed at that time. I’m not absolving the blame at all, but you know, it’s easy to shift the blame now onto Grachev for the fact that we had an absurd and tragic assault on Grozny. Now you can generally blame all the shortcomings that occurred during the 4 years when Grachev was Minister of Defense: bad wages, weapons, the fact that we were in the mud, in the sand, in Siberia, you can blame everything. But we must not forget at what time Grachev commanded the armed forces, we must not forget to what extent the army was ready, in essence it was dismantled, Grachev tried to put it together as easily as possible from the remnants of the Soviet army. We had a significant loss of combat readiness at that time. A huge number of our officers had no combat experience. In general, Grachev accepted the army as he accepted it.

And I wouldn’t want us today to fail to notice at least those positive features that the army noticed under Grachev. Yes, Pavel Sergeevich Grachev got into this very ugly story with Mercedes. But you need to know why he got into it. Because the people who came out of Germany, who enriched themselves with terrible force there and in whose footsteps the military prosecutor’s office followed, they simply, these fellow generals, impudently smeared Grachev, bought him a Mercedes and dragged him into this criminal case. He cursed this damned Mercedes a thousand times, which they allegedly tried to give him as a gift, and then allegedly forged documents, which is legal. Yes, Grachev was not a child, but dizziness from success, Yeltsin’s wild love, she often freed the hands of the president’s favorite, which was Pavel Sergeevich. And here, of course, we must remember the dachas, and who shouted: Pavel Sergeevich, your generals have grown fat and built dachas. Didn’t Pavel Sergeevich admit that when he was Minister of Defense, he gathered a whole bunch of generals close to him and even the head of the chancellery, he wanted to confer the rank of army general. We, of course, understood why it was happening. Grachev was a vulnerable defense minister; it was not for nothing that Lebed said so sarcastically about him that he jumped into the chair of the defense minister like a March cat onto a fence. We know all this. With all these pros and cons, Grachev will go down in history. But, of course, no one will take his place in the history of the Russian army.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: We are listening to a question from Muscovite Nikolai Illarionovich.

Listener: You said words that do not deserve the negativity of the Minister of Defense; this does not suit the Minister of Defense of such a state. You know how he started in Chechnya - drunk. It was his 31st birthday, his gift, he gave himself a gift, he yelled at the whole country that I was giving myself a gift, I would take over Chechnya in two days. On it lies the blood of children whose mothers did not live to see them.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: Do you think these words addressed to Yushenkov and Kovalev that they are traitors to their homeland have been refuted by subsequent history?

Igor Korotchenko: To be precise, Grachev called them “bastards” for the treasonous position they took towards their own soldiers and their own army. I think this is a historical assessment. And in this regard, in my opinion, Grachev acted absolutely right then. As for mistakes, yes, Grachev is guilty of those mistakes that were made during the first Chechen campaign - this is completely obvious. Because the Minister of Defense is responsible, among other things, for such important decisions, the decision to storm Grozny on New Year’s Eve - this was, of course, a political decision of the Minister of Defense. Meanwhile, you can’t hang all the blame on Grachev. We know that he was a categorical opponent of solving the Chechen problem by military means, at least within the very tight deadline that the Kremlin set for him. And Grachev was an opponent of such hasty decisions that were not prepared in military-technical terms. Therefore, a share, maybe even a greater share of responsibility for what happened at the beginning of the first Chechen war must be placed on President Yeltsin and his immediate political circle, who actually twisted Grachev’s arms and forced him to act so hastily and therefore so ineffectively in the very stratum of this war in Chechnya.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: We are listening to Muscovite Ilya Efimovich.

Listener: Good evening. I wanted to ask Viktor Nikolaevich Barants, he said that Mr. Grachev was a forced person, he had a dilemma: either follow the order or submit his resignation letter. But there was a precedent, if I’m not mistaken, General Vorobiev refused to carry out the order and resigned. As I understand it, you personally knew Mr. Grachev well, what prevented him from resigning at that moment - love for benefits, understanding of false military duty, why at that moment, when he did not internally agree to send troops into Chechnya , didn't resign?

Viktor Baranets: I answer right away: because the soldier Grachev remained Grachev, and did not smear his snot, reflecting on the order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief that it was necessary to repel Chechen armed terrorists. Now it’s easy to think about what choice Grachev might have faced. Grachev, I repeat, is a soldier of the regime, a soldier of the president. I want to say even more that Grachev was the president’s bodyguard. And he did not want to be a traitor to the aspirations and hopes that Yeltsin had placed on him. I would like to take this opportunity to remember Yushenkov here, you remember that Grachev rashly called Yushenkov a bastard, I remember how Yushenkov sued. We have lawyers in our business management, there was a big commotion, it was necessary to somehow save Pavel Sergeevich in this situation. The best experts in the Russian language were called in and they were racking their brains day and night about how we should deal with Yushenkov, because it would be a shame if the Minister of Defense was fined 10 million rubles. I remember that joyful moment when one expert on the Russian language called from the Institute of Russian Literature of the Russian Language and said: “Pavel Sergeevich, don’t worry, because in many stylistic parameters, the “bastard” is the son of a snake, and there is nothing bad in that.” As they say, what would a wake be without anecdotes, without tales, but nevertheless, I also remember this episode.

I would like to add one more fundamentally important thing. You know, today we can dump all the dead soldiers and officers who died in Chechnya in a heap and bring this sad mass to Grachev’s grave. But I am afraid that this will be such an everyday reflection, this is the reflection of people, yes, indeed, many of whom have lost children, nephews, husbands. But we must evaluate the figure from the height of the specific historical conditions that had developed by December 1994. I agree that Grachev was not happy to send troops into Chechnya. And if we want to operate with facts, then we need to look into the protocols of the Security Council, where Grachev’s arms were actually twisted. He did not give open consent. Moreover, now is the time to tell the truth that for Grachev’s indecision to send troops into Chechnya, he was removed from his post, he was not given Kremlin communications for several days - this also needs to be known. And then only Pavel Sergeevich, in order to improve his reputation in front of the president, who almost called him a traitor, then he said this phrase, which he probably regretted until yesterday, this bravura phrase, this boastful phrase, an unrealistic phrase. He rashly blurted out that Grozny could be taken with one airborne assault regiment. But that's life. We must evaluate the figure of Grachev strictly in the coordinates of the military-political situation that existed in Russia during the period of his rule.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: In your opinion, was Grachev’s resignation from the post of Minister of Defense parallel to the resignation of Korzhakov and Barsukov dictated by political considerations?