A concept is the result of a generalization of a set of homogeneous objects according to their common essential features. For example, the concept of “building” is formed as a result of abstraction from the individual characteristics of individual buildings, which is achieved using logical techniques: comparison, analysis, synthesis, abstraction and generalization.

The concept is inextricably linked with the linguistic unit - the word. Concepts are expressed and consolidated in words and phrases called names. Simple names: “building”, “table”, complex names: “unknown area”, “famous person”, etc. are the material, linguistic basis of the corresponding concepts, without which it is impossible to form concepts or operate with them.

However, the unity of language and thinking, words and concepts does not mean their identity. For example, in any language there are synonymous words and homonym words. Synonyms are words that are close or identical in meaning, expressing the same thing, but differing in shades of meaning or stylistic coloring (“labor” and “work”). Homonyms are words that have the same sound, the same form, but express different concepts (for example: fist - hand and fist - rich peasant). Many words have multiple meanings. The polysemy of words (polysemy) often leads to confusion of concepts, and, consequently, to errors in reasoning. Therefore, it is necessary to establish the exact meaning of words in order to use them in a strictly defined sense.

Concept– this is the result of generalizing a set of homogeneous objects according to their essential characteristics. Essential features are stable, necessary features, without which a given object cannot exist in its qualitative certainty. The main logical methods of concept formation are: comparison, analysis, synthesis, abstraction and generalization.

Any concept can be characterized in terms of its content and scope. Scope of concept- this is a set of objects that are thought of in a given concept. For example, the concept “student” includes all students who were, are and will be. Contents of the concept- this is a set of essential features of an object that are thought of in a given concept. For example, the content of the concept “student” includes the property of being a student of a higher educational institution. The content of the concept “square” includes the following characteristics: “to be a quadrilateral”, to have “equal sides” and “equal angles”.

Content and volume are related to each other on the basis of the formal-logical principle of the inverse relationship: the greater the content of a concept, the smaller its volume, and vice versa. For example, if we add the attribute “fiction” to the content of the concept “literature,” we will reduce the scope of this concept, since we will exclude scientific and popular science literature from it, but we will increase its content with the additional attribute “fiction.”

The transition from a concept of a greater degree of generality to a concept of a lesser degree of generality is called limitation. With this operation, the content increases, but the volume decreases. For example, “law – criminal law”. The transition from a concept of a lesser degree of generality to a concept of a greater degree of generality is called generalization, that is, we increase the volume, but reduce the content. For example, “civil law is law.”

Logic also operates with the concepts of “class” (“set”), “subclass” (“subset”) and “class element”.

By class, or by many a certain set of objects that have some common characteristics is called. Such, for example, is a class of students, higher educational institutions, etc. Based on the study of a certain class of objects, the concept of this class is formed. A set can be reflected not in one, but in several concepts. For example, many athletes and many students can be combined into one set: students and athletes. This set is reflected in two concepts.

A class may include a subclass. For example, the class of students includes a subclass of law students.

Classes consist of a set of this class. Class element - this is an item included in this class. Thus, elements of many educational institutions will be schools, institutes, technical schools, etc.

Types of concepts

By volume concepts are divided into general, single and empty. Empty concepts do not designate any object. Examples of an empty concept are "centaur", "the time of year between December and January". Single concepts designate only one object: for example, “planet Earth”. Are common concepts denote more than one object, such as, for example, the concepts “student”, “teacher”, “person”, “table”. General concepts include registering and non-registration. Registering concepts have a finite volume of objects included in a given concept. Non-registering have no finite volume. General and individual concepts are collective and non-collective (dividing) Collective- those in which homogeneous objects are thought of as one whole. For example, “collective” is a collective general concept, “the constellation Ursa Minor” is a collective individual concept. Non-collective (separation) concepts refer to each object that is thought of in a given concept: “hand”, “light bulb”, “bird”. Thus, if the statement refers to each element of the class, then such a use of the concept will be disjunctive; if the statement refers to all elements taken in unity, and is not applicable to each object separately, then the use of the concept will be collective. For example: “students of our institute study logic,” we use the concept “students of our institute” in a divisive sense, since This statement applies to every student. In the statement “students of our institute held a theoretical conference,” here the concept “students of our institute” is used in a collective sense. The word “everyone” is not applicable to this judgment.

By content concepts are divided into concrete and abstract. Specific concepts denote a separate object, thing or person. For example, “house”, “tree”, “building”. Abstract concepts denote a property or relationship between objects. Examples of abstract concepts are “justice”, “truth”, “good”. Contrasting abstract concepts with concrete ones is necessary to prevent one of the fairly common errors called the “hypostatization error,” that is, finding in the real world a thing that corresponds to an abstract concept. The distinction between concrete and abstract concepts is based on the difference between an object, which is thought of as a whole, and a property of an object, abstracted from the object itself and not existing separately from the object. Abstract concepts are formed as a result of abstraction, abstraction of a certain feature of an object from the object itself; these signs are thought of as independent objects of thought. Thus, the concept of “courage” reflects a trait that does not exist on its own, in isolation from the persons possessing this trait. This is an abstract concept.

Relative concepts that presuppose the existence of another object are called: “north pole - south pole”, “father - son”. IN irrelevant Concepts conceive of objects that exist on their own, regardless of other objects: “house”, “city”, “village”. Positive concepts speak of the presence of some attribute of an object. Negative– about the absence of this sign. For example, positive concepts are the concepts of “wonderful person”, “sublime feeling”, and negative concepts are “injustice”, “slowness”. Negative concepts in Russian are most often expressed by the particles “ne”, “bes”, “bez”, but not always. For example, the concepts “slob” and “bad weather” are positive. In foreign words, mainly of Greek origin, negative concepts are expressed by the negative prefix “a” “immoral”, “asymmetry”, etc.

One should not confuse concrete concepts with individual ones, and abstract ones with general ones. General concepts can be both concrete and abstract (“crime” - general, concrete; “crime” - general, abstract).

To determine what type a concept belongs to means to give it a logical characterization. Thus, giving a logical characterization of the concept “house”, it is necessary to indicate that this concept is general, specific, positive, and irrespective.

The logical characterization of concepts helps to clarify their content and scope, and to develop a more precise use of the words that express them.

Relationships between concepts

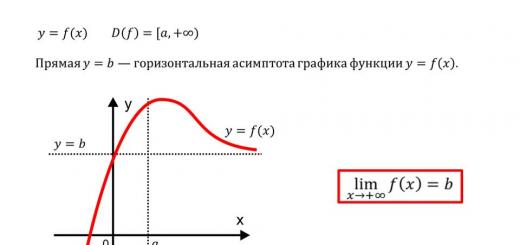

Concepts are in certain relationships with each other. The relationships between the volumes of concepts are depicted on Euler circles. First of all, concepts are divided into comparable and non-comparable. Comparable concepts have common characteristics, which makes it possible to compare them. Incomparable do not have such characteristics, so their comparison does not make sense. An example of the latter is the concepts “deputy” and “stone”.

The compared concepts are compatible and incompatible. Compatible– these are those whose volumes completely or partially coincide. Incompatible– the volumes do not match. Compatible concepts are equivalent, intersecting, subordinate. Concepts where the volumes, but not the contents, completely coincide are called equivalent. For example, “grandson” and “great-grandson”, they do not coincide in content, but are equivalent in scope, since every grandson is a great-grandson, and every great-grandson is a grandson. Equivalence is depicted by one circle:

1. Grandson 2. Great-grandson

Intersecting concepts are concepts whose scopes overlap. For example: “student” and “musician”, since some students are musicians, and some musicians are students. On circles, this type of relationship is depicted in the form of two intersecting circles (if two concepts are related), where the intersecting part symbolizes the coincidence of volume.

1. Student. 2. Musician.

In a relationship submission there are concepts, the scope of one of which is included in the scope of the other. A concept with a larger volume is called subordinating. The concept with a smaller volume is subordinate. For example, the concepts of “man” and “father”. “Man” is a subordinate concept, and “father” is a subordinate concept. Because all fathers are men, but not all men are fathers. On circles this is depicted as two circles, one of which is included in the other circle.

1. Man. 2. Father.

There are three types of incompatible concepts. Subordination- this is the relationship between the volumes of two or more concepts that exclude each other, but belong to some generic concept. For example, “law”, “civil law”, “criminal law”. On circles they are depicted as separate non-overlapping circles within one, larger circle, which represents the generic concept.

1. Law 2. Civil law 3. Criminal law

Opposite concepts: volumes exclude each other, without adding up to the entire volume of the generic concept. Opposite concepts are the concepts of “love” and “hate”, “beautiful” and “ugly”.

1. Hate 2. Love

Contradictory concepts - volumes exclude each other, and together they constitute the volume of the generic concept. For example, the concepts of “love” and “dislike”. These concepts exhaust the scope of the generic concept – feeling.

1. Love 2. Dislike

Circular diagrams can be used to simultaneously represent the three-dimensional relationships of many concepts. For example, the concepts “woman”, “woman with children”, “woman without children”, “mother” are depicted by one circle denoting the concept “woman”, one part of the circle constitutes the concept “woman without children”, the other part circle means two equivalent concepts “a woman with children” and “mother”.

1. Woman 2. Woman with children

3. Woman without children 4. Mother

Definition of concepts

A definition, or definition, is a logical operation that reveals the content of a concept.

Types of definition. There are nominal and real definitions.

Nominal a definition is called, through which, instead of describing an object, a new term is introduced, the meaning of the term, its origin, etc. is explained. For example: “The field of science related to space flights is called astronautics”; “The term “legal” means relating to jurisprudence, legal.” Real is a definition that reveals the essential features of an object. For example: “Evidence is proof of the guilt of the accused in committing a crime.”

There are also explicit and implicit definitions. To the obvious include definitions containing a direct indication of the essential features inherent in the subject. They consist of two clearly expressed concepts: defined and defining. Implicit are definitions in which the content of the defined concept is revealed in a certain context.

The main type of explicit definition is definition through genus and specific difference.

Definition through genus and species difference. Genetic determination. The logical determination operation includes two successive steps.

The first stage is subsuming what is being defined under a broader generic concept. The generic concept contains part of the characteristics of the defined concept; in addition, it indicates the circle of objects that includes the defined object. For example, for the concept “logic” the generic concept will be “philosophical science”.

Usually they indicate the closest genus, which, compared to a more distant genus, contains more characteristics that are common to the characteristics of the concept being defined. By subsuming, for example, the concept of “taking a bribe” under the concept of a crime or “act,” we will complicate our task. Given this circumstance, this type of definition is sometimes called definition through the nearest genus and species difference.

But subsuming a defined concept under a generic one does not mean defining it. It is necessary to indicate a feature that distinguishes the object being defined from other objects belonging to the same genus. This operation is carried out at the second stage, which consists of indicating the distinctive feature of the object being defined. This feature will be a species difference. Species difference belongs only to a given species and distinguishes it from other species included in a given genus. So for logic, a species difference will be a sign indicating the subject of this science - the forms in which human thinking occurs and the laws to which it obeys. This feature reveals the essence of logic and distinguishes it from other sciences: political economy, theory of state, criminology, etc.

Thus, in order to define any concept, it is necessary, firstly, to find the genus, i.e., to perform a generalization operation, and, secondly, to indicate the specific difference, i.e., a feature that distinguishes this concept from other concepts included in this genus. Definition through the genus and specific concept is expressed by the formula A = Bc, where A is the concept being defined, Bc is the defining concept, c is the specific difference.

It must, however, be borne in mind that when indicating species differences it is not always possible to limit oneself to one characteristic. For example, in criminal law, a gang is characterized by a combination of three characteristics: 1) an association of two or more individuals, 2) the presence of weapons in at least one of them, 3) the cohesion of the group, the stability of the criminal ties of its members.

Determination through genus and specific difference is the most common type of definition, widely used in all sciences, including legal ones. Thus, in the theory of state and law, the following definition of a republic is given: a republic is a form of government (genus), in which the highest state power is vested in an elected body elected for a certain term (specific distinction). In civil proceedings, a decision is defined as a procedural document (genus) issued by the court of first instance when considering a civil case on the merits (specific distinction).

Genetic- is a definition that indicates the origin of an object, the method of its formation. For example: “A ball is a body formed by the rotation of a circle around one of its diameters.

Revealing the method of formation of an object, its origin, genetic origin plays an important cognitive role and is widely used in a number of sciences. Being a variety, defined through genus and specific difference, it has the same logical structure and is subject to the same rules.

Determination rules. The definition must be not only true in content, but also correct in its construction and form. If the truth of a definition is determined by the correspondence of the characteristics specified in it to the actual property of the defined object, then the correctness of the definition depends on its structure, which is regulated by a number of logical rules.

1. The definition must be proportionate.

The rule of proportionality requires that the volume of the defined concept be equal to the volume of the defining concept. In other words, these concepts must be in a relation of identity (A=Bc). For example, the definition “Recidivist is a person who committed a crime after being convicted of a previously committed crime” is proportionate. If a “recidivist” is defined as a person who has committed a crime, then the rule of proportionality will be violated: the scope of the defining concept (“person who committed a crime”) is wider than the scope of the defined concept (“recidivist”).

This violation of the rule of proportionality is called mistake of too broad a definition(A An error will occur if the defining concept turns out to be an already defined concept in its scope. Such an error will be made if, for example, the victim is defined as a person who has been physically harmed by a crime. In this example, the defining concept does not cover the characteristics of a victim who may suffer not only physical, but also moral and property harm. This error is called error of too narrow a definition(A>Bc). 2. The definition should not include a circle.

If, when defining a concept, we resort to another concept, which, in turn, is defined using the first, then such a definition contains a circle. For example, rotation is defined as movement around an axis, and an axis is defined as a straight line around which rotation occurs. A type of circle in the definition is tautologistsI- an erroneous definition in which the defining concept determines the defined. For example, an idealist is a person with idealistic beliefs. Such erroneous definitions are called “the same through the same.” Such concepts do not reveal the content of the concept. If we do not know what an idealist is, then indicating that a person has idealistic beliefs will not add anything to our knowledge. A tautology differs from a circle in its definition by being less complex in its construction. The defining concept is a simple repetition of the defined. 3. The definition must be clear.

The definition must indicate known characteristics that do not require definition and do not contain ambiguity. If a concept is defined through another concept, the characteristics of which are not known, and it itself needs definition, then this leads to an error called defining the unknown through the unknown or definition X through at. For example, Hegel defines the state as follows. “The state is the political manifestation of the world spirit.” However, the definition of the state with the help of the mystical concept of “world spirit”, which corresponds to the empty class, cannot be clear. The rule of clarity of definition requires that definitions not be replaced by metaphors, comparisons, etc., which, although they are important for characterizing the subject, are not definitions. 4. The definition does not have to be negative. The specific difference should indicate a characteristic that belongs to the object, and not one that is absent from it. True, this rule has exceptions. There are definitions, the specific difference of which is a negative attribute: an atheist is a person who does not recognize the existence of God; disobedience is a military crime consisting of deliberate failure to comply with the order of a superior. Negative concepts are widely used in mathematics. This means that this requirement is not a strict logical rule that is mandatory when defining any concept. Implicit definitions. Techniques that replace definition. Using definitions through genus and species difference, most concepts can be defined. However, for some concepts this technique is not suitable. It is impossible to define extremely broad concepts (categories) through genus and specific difference, since they do not have a genus, and individual concepts, since they do not have specific difference. In these cases, they resort to implicit definitions, as well as to techniques that replace the definition. Implicit definitions include definition through an indication of the relationship of an object to its opposite. This technique is widely used in defining philosophical categories. For example, “Freedom is a recognized necessity,” etc. Techniques that replace definition include; description, characterization, comparison, discrimination, ostensive definition. Task descriptions consists in more accurately and completely indicating the characteristics of an object, and, as a rule, external characteristics are listed. Characteristic consists of indicating the distinctive, characteristic features of a single object (persons, objects, etc.) A technique that replaces definition is also comparison, with the help of which one object is compared with another that is similar to it in some respect. This technique is used to figuratively characterize an object. By using distinctions signs are established that distinguish one object from other objects similar to it. For example, when searching for stolen property, “special features” play an important role: a monogram or engraving on a watch, etc. In some cases, ostensive definitions are widely used. Ostensive is a definition that establishes the meaning of a term by demonstrating the thing denoted by the term. These definitions are used to characterize objects accessible to direct perception. The ostensive definition is also used to characterize the simplest properties of things: color, smell, etc. A definition cannot provide comprehensive knowledge about a subject. Revealing the content of the concept, the definition indicates the general, essential features of the object reflected in it, abstracting from all its other features. However, revealing the main thing in a subject, a definition allows you to highlight a given subject, distinguish it from other subjects, and warns against confusion of concepts and confusion in reasoning. And this is the enormous value of definitions in knowledge and practical activity. Division of concepts By division is called a logical operation that reveals the scope of a concept, called division. In the division operation it is necessary to distinguish divisible concept, i.e. the scope of the concept that needs to be revealed, division members, i.e. subordinate types into which the concept is divided (they represent the result of division), and base of division- the sign by which division is made. The essence of division is that objects included in the scope of the concept being divided are distributed into groups. The divisible concept is considered as a generic one, and its volume is divided into subordinate types. Thus, the concept of “literature” is a genus, and the members of the division are “scientific literature”, “fiction”, “popular science literature”, etc. The division of concepts should not be confused with the mental division of the whole into parts. Its members of division are independent species; when divided, the individual parts of the object from which it consists are separated. But the parts of the whole are not species that are formed as a result of the operation of dividing the concept. If it were necessary to divide the concept of “aircraft,” it would be necessary to indicate the types of aircraft according to some characteristic, for example, by engine type. The following types of division are distinguished: division by modification of a characteristic and dichotomous division, which is often considered as its subtype. Division by modification of a characteristic.

The basis of division is a feature, when changed, specific concepts are formed that are included in the scope of the thing being divided (generic concept). For example, a socio-economic formation, depending on the method of production, is divided into subordinate types: primitive communal, slaveholding, feudal, etc.; the right in the form of its expression - to legal custom, legal precedent and normative act. Various features of the divisible concept can be used as a basis. It is possible to divide states according to their historical type, according to forms of government, according to forms of government; the population of a country - according to its membership in social classes, nationality, education, etc. The choice of attribute depends on the purpose of division and practical tasks. At the same time, certain requirements must be imposed on the foundation, the most important of which is the objectivity of the foundation. For example, science should not be divided into easy and difficult, books into interesting and uninteresting. This division is subjective: the same sciences can be easy for some people and difficult for others. Division rules.

In the process of dividing a concept, it is necessary to follow a number of rules that ensure clarity and completeness of the division. 1. The division must be proportionate.

The task of division is to list all types of the concept being divided. Therefore, the volume of division terms must be equal in their sum to the volume of the concept being divided. This rule requires that no division terms be omitted. If, for example, when dividing socio-economic formations only slaveholding, feudal and capitalist formations are indicated, then the rule of division of proportionality will be violated, since the member of the division (primitive communal) is not indicated. This division is called incomplete. The rule of proportionality will also be violated if we indicate unnecessary division members, that is, concepts that are not species of a given genus. Such an error will occur if, for example, when dividing the concept of “punishment,” in addition to all types, a warning is indicated, which is not included in the list of penalties in criminal law, but is a type of administrative penalty. This division is called division with extra members.

2. Division must be carried out using only one base.

Throughout the entire division, the feature we have chosen must remain the same and not be replaced by another feature. 3. Division terms must be mutually exclusive.

This rule follows from the previous one. When mixing bases, the division members - species concepts - will be in a relationship of partial coincidence. We get this result when dividing crimes into intentional, military and careless. If the division is made on one basis, then the members of the division will exclude each other, each object covered by the dividing concept will, as a result of the division, be included in only one of the subordinate species. 4. Division must be continuous.

This means that in the process of dividing a generic concept, you need to move on to the closest species without skipping them. For example, the concept of “literature” can be divided into fiction, scientific, popular science, etc. Each of these types can be divided, in turn, into subspecies. But one cannot move from division into species to division into subspecies. This division is devoid of sequence, it is called jump in division.

Dichotomous division (dichotomy). Represents the division of the volume of a divisible concept into two contradictory concepts. Dichotomous division is used in various sciences. For example, reflexes are divided into conditioned and unconditioned; wars - just and unjust. A dichotomous division does not always end with the establishment of two contradictory concepts. Sometimes a negative concept is again divided into two concepts, which helps to isolate from a large circle of objects a group of objects that interests us in some respect. Compared to division by modification of a characteristic, dichotomous division has a number of advantages. In a dichotomy, there is no need to list all the species of the dividing genus: we single out one species, and then form a contradictory concept that includes all other species. The members of division are two contradictory concepts that exhaust the entire scope of the concept being divided. Therefore, division is always proportionate. The division is made on one basis - depending on the presence or absence of a certain attribute in the object. The members of a dichotomous division are always each other; any object can be thought of only in one of the contradictory concepts that cannot be intersecting. Classification.–

This multi-stage, branched division represents the distribution of objects into groups (classes), where each class has its own permanent, specific place. The purpose of classification is to systematize our knowledge, therefore it differs from the usual division in its relatively stable nature and persists for a more or less long time. In addition, the classification forms an expanded system, where each member of the division is again divided into new members, branching into new classes, usually fixed in tables, diagrams, etc. Knowledge of this operation helps to correctly distribute objects into groups, study them, and, therefore, get to know the whole class as a whole. Knowledge of the types and rules of division is of great importance in the work of a lawyer, especially in investigative practice; planning, crime investigation, drawing up diagrams in the planning process, classification of investigative leads and a number of other investigative actions have as their main logical operation the division of concepts. There are natural classifications, made on the basis of an essential characteristic, and artificial (based on any non-essential characteristic). An example of a natural classification is the periodic system of D. Mendeleev. An example of an artificial one is library catalogs. CONCEPT Through dept. P. and P. systems display fragments of reality studied by various sciences and scientific theories. F. Engels pointed out that “... the results in which his data are summarized (natural sciences. - Ed.) experience, the essence of the concept..." (Marx K. and Engels F., Works, T. 20, With. 14)

. P. often reflects such objects and their properties that cannot be represented in the form of a visual image. With the help of P., both fragments of reality, considered in abstraction from change and development, and the process of constant change and development of the reality being studied, the process of deepening our knowledge about it, are displayed. Lenin emphasized: “Concepts are not immovable, but - in themselves, by their nature - before” (PSS, T. 29, With. 206-07)

; “... human concepts... are forever moving, transforming into each other, pouring one into another, but this does not reflect living life” (ibid., With. 226-27)